Abstract

Background/Objectives: Cranioplasty (CP) is associated with high complication rates (20–50%), and the optimal choice between patient-specific implants (PSIs) and hand-molded (HM) alternatives remains debated. This systematic review and meta-analysis aims to compare surgical and postoperative outcomes between PSIs and HM implants. Methods: A systematic search was performed in three databases to identify studies reporting surgical site infection (SSI), implant removal, reoperation, operative time or cosmetic outcome for PSIs and/or HM implants. Two-arm studies of the same material were analyzed separately from pooled single- and two-arm studies. Results: 125 observational studies involving 10,034 patients were included. In two-arm comparisons, PSIs reduced implant removal for titanium (OR 0.34, p = 0.053) and PMMA (OR 0.56, p = 0.188), while SSI rates showed no meaningful difference between groups. In one-arm analyses, PSIs demonstrated lower explantation probabilities (titanium 6.1%, PMMA 7.9%) compared with HM alternatives (titanium 9.9%, PMMA 14.2%), alongside shorter operation times and fewer reoperations. Cosmetic outcomes consistently favored PSIs. Conclusions: PSIs demonstrate advantages in efficiency, durability, and esthetics compared with HM implants, supporting their preferential use where resources allow. HM implants remain a cost-effective option in resource-limited settings. Due to the observational nature of the included studies and differences in study populations across arms, the findings should be interpreted with caution.

1. Introduction

Cranioplasty (CP) is a surgical procedure performed to repair cranial defects, most commonly following decompressive craniectomy, which is used as a life-saving intervention in cases of traumatic brain injury, stroke, or intracranial hypertension [1]. Beyond restoring skull integrity and protecting the underlying brain, CP also contributes to improved cerebral hemodynamics and neurological function, as well as providing critical cosmetic reconstruction, which can greatly affect patient self-image and quality of life [2]. As a result, timely and effective CP is now regarded as a critical component in supporting neurological recovery and overall rehabilitation. The growing use of CP in both emergency and elective neurosurgical procedures has led to a rising clinical demand for better implant solutions [3].

However, CP is not without risks. Despite being a reconstructive and life-saving operation, CP carries an unusually high complication rate ranging from 20 to 50%–higher than most other neurosurgical procedures [3,4]. Complications include surgical site infection (SSI), implant extrusion, wound breakdown, and the need for revision surgeries, which often come with prolonged operation time and poor cosmetic outcome. These risks are strongly influenced by multiple factors, including the material used, the timing of surgery, and the precision of implant fit [5].

To address these challenges, the use of patient-specific implants (PSIs)–fully customized prostheses designed using 3D printing and computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing technology–has gained momentum. Materials commonly used in PSIs include titanium, polyetheretherketone (PEEK), and polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), each with distinct biological, mechanical, and clinical profiles [6,7,8,9].

Despite these developments, there remains no clear consensus on the optimal implant material or the superiority of PSIs over traditional techniques [10,11]. Current literature is fragmented, often limited to small, retrospective series with heterogeneous patient populations and inconsistent outcome reporting. Prior reviews have largely grouped synthetic materials together or failed to isolate fully customized PSIs for head-to-head comparison across critical endpoints like SSI, implant failure and cosmetic success [4,12,13]. Given the increasing adoption of patient-specific technology, the rising demand for CP and the lack of high-level comparative data, an updated systematic review and meta-analysis is urgently needed.

The primary aim of this study is to systematically evaluate the current evidence regarding the use of fully customized PSIs in CP. We aim to compare postoperative outcomes, including SSI, implant failure, total reoperation rate, operation time, and cosmetic results across these materials. Through a meta-analytic approach, we seek to clarify whether the type of PSI material influences complication rates and patient outcomes and to guide future clinical decision-making and standardization in CP practices.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [14] and adhered to the methodology outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [15] (Supplementary Material Table S1). The review protocol was registered prospectively with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42024582985). This work was carried out as part of the Systems Education Program [16].

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

The research question was structured using the PICO framework, where the population (P) consisted of patients undergoing CP, the intervention (I) was the use of PSI, the comparison (C) was the use of intraoperative HM implants, and the outcomes (O) were postoperative complications (SSI, implant failure, total reoperation rate), operation time, cosmetic score and implant cost. To be eligible, studies had to involve human participants who received a CP using either a PSI or a HM implant and had to report on at least one of the predefined outcomes. No restriction was placed on the length of follow-up time to ensure comprehensive inclusion of outcome data. However, studies exclusively involving pediatric populations or mixed adult-pediatric cohorts were excluded to reduce demographic heterogeneity. Eligible studies included both comparative (two-arm) and single-arm observational cohorts. Two-arm studies were defined as those comparing PSIs and HM implants made of the same material within the same study, and these contributed to direct comparisons (odds ratios (OR)). Single-arm studies were defined as those reporting only one implant type and/or multiple materials without a direct PSI–HM comparison, and these contributed to pooled proportions and meta-regression analyses. Eligible articles needed to report raw outcome data for at least one of the prespecified endpoints. Case reports, small case series, conference abstracts, and studies lacking original data were excluded. Where multiple studies reported on the same patient cohort, only the publication with the largest sample size was included.

2.2. Selection Process and Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search was carried out on 25 August 2024, using three electronic databases: MEDLINE (via PubMed), Embase, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). The search was conducted without any limitations on publication date or study type. Although language restrictions were not applied during the initial search, studies unavailable in English, German, or Hungarian were excluded during full-text screening. The complete search strategy is outlined in Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material Text S1). Three reviewers (ELN, BKGC and KSBJ) independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full-text assessment for final inclusion. Duplicate entries were removed both automatically and manually. Any disagreement between reviewers was resolved through consensus. Inter-rater agreement was assessed using Cohen’s kappa, yielding high concordance scores (κ = 0.96 for abstract screening and κ = 0.97 for full-text selection).

2.3. Data Collection Process and Extracted Variables

Three reviewers (ELN, BKGC, and KSBJ) independently extracted data from all eligible studies. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion to reach consensus. The extracted information included: (1) study details—such as first author, publication year, design, study population (sample size, age, and sex assigned at birth), study period, country, institution, diagnosis, implant type, and follow-up duration (in months); (2) postoperative complications; (3) operative time; and (4) cosmetic outcomes. In this study, outcome definitions were standardized across all included articles. Outcome definitions varied across studies. SSI was defined as any postoperative infection involving the incision, soft tissues, or deeper cranial compartments related to the cranioplasty procedure. This included superficial wound infections, deep infections involving soft tissues or bone, and intracranial or organ-space infections when explicitly attributed to the implant or surgical site. These categories were harmonized under a unified SSI outcome to enable consistent extraction across studies. Implant failure was defined as the removal or revision of the implant due to postoperative complications. Reoperation was defined as any subsequent ambulatory or surgical intervention following the initial implantation. Implant removal and total reoperation were analyzed separately to capture the full burden of complications, as “implant removal” reflects material- or implant-specific failure, while “reoperation” includes wound revisions or soft-tissue procedures not necessarily requiring explantation. Operation time was measured from the initial skin incision to the final closure of the surgical site. Cosmetic outcomes were reported using a VAS ranging from 0 to 10, with 10 representing the best possible esthetic result and 0 the poorest.

2.4. Assessment of the Risk of Bias and Certainty of the Evidence

The risk of bias in the included studies was independently assessed by three reviewers (ELN, BKGC, and KSBJ) using the RoB 2 tool for randomized studies, the ROBINS-I tool and the methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) [15,17]. Any discrepancies in scoring were resolved through discussion. The certainty of evidence across outcomes was rated using the GRADE framework, in line with the GRADE handbook [18], and processed using GRADEpro GDT software (version 2013) [19].

2.5. Synthesis Methods

This meta-analysis investigated the differences in various outcomes with PSIs and HM implants in patients with CP. Data for 6 different outcomes were available in the studies: 3 continuous and 3 dichotomous. The main focus was on the different design and material combinations, from which we could identify 10 different ones. Since not every material allows for both PSI and HM design, direct comparisons across methods were not always feasible. For designs where a direct same-material comparison between PSIs and HM implants was possible, the corresponding two-arm studies were analyzed separately using OR for dichotomous outcomes. All single-arm studies lacking direct comparators, were synthesized in pooled proportion analyses and meta-regression using a multilevel random-effects model. To calculate the proportion or the OR, sample size and number of events were extracted from the manuscript. OR were reported as the odds of the event in the PSI group against the odds of the event in the HM group. Otherwise, proportions and mean values were calculated, respectively. Proportions were logit transformed before running the meta regression using the escalc() function. Continuity correction of 0.5 for 0 or 100% proportions was applied and the corresponding sample variance was used with a diagonal variance-covariance matrix. This error structure implies the statistical independence of sampling errors, which can be justified since there are no shared controls, repeated measures, or one patient cannot get multiple different treatments. Material and design were used as a combined factor variable using every combination as a single level. Two outcomes needed data modifications. Implant prices extracted from the studies in their original currency, exchanged for USD at the exchange rate from the middle of the study period, were inflation-adjusted but were not pooled. Cosmetic scores were pooled, but because of the differing scales used, the scales were converted to a 0 to 10 scale before the analysis. Some studies reported more than one results for the same outcomes for different material/design combinations. Although the studies reported average measurement values and standard errors corresponding to distinct combinations, i.e., the correlations among the within-study error terms can be assumed to be 0; the random-effect terms within a single study are correlated when a study contributes to the pooled results with more than one measurement result. For this reason, to calculate pooled results we used multivariate meta-analysis with the rma.mv() function of the metafor R package (version 4.8.0). A two-level hierarchical structure was employed for the random effect terms. We assumed that effect sizes are nested within studies. Statistical analysis was conducted using R version 4.4.3 (R Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) based on the recommendations from Harrer et al. [20]. Absolute between-study heterogeneity was expressed by tau, and relative between-study heterogeneity was described by Higgins and Thompson’s I squared statistics [21].

3. Results

3.1. Search and Selection

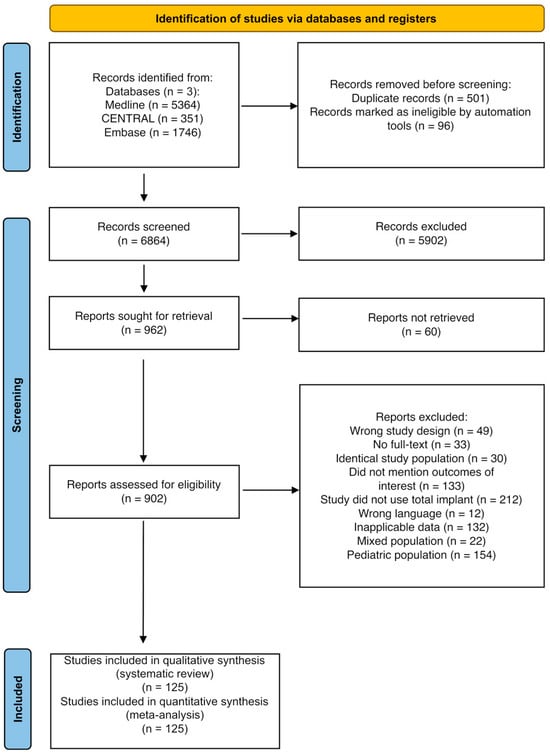

Of the 7461 articles screened, 902 underwent full-text review, of which 125 met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). A total of 98 studies evaluated PSI, and 69 evaluated HM implants, with several studies assessing both. Data from 10,034 patients were analyzed, with 6170 in the PSI group and 3864 in the HM implant group. Baseline characteristics are detailed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of the study selection process.

Table 1.

Demographic data of the patients. a Patient-Specific Implant, b Hand-molded, NA: Not available, PMMA: Polymethylmethacrylate, AB: Autologous Bone, PEEK: Polyetheretherketone, Ti: Titanium, HA: Hydroxyapatite, PP: Porous polyethylene, CaP-Ti: Calcium Phosphate-Titanium.

3.2. Risk of Bias Assessment

Single-arm studies were evaluated using the MINORS scale, with most demonstrating a low to moderate risk of bias, mainly due to the lack of blinded assessments and the absence of prospective sample size calculations. Several studies also reported follow-up losses exceeding 5%. Among the ten two-arm studies, the ROBINS-I tool identified a generally moderate risk of bias, with some studies showing serious risks related to confounding factors, subjective outcome measurements, and missing data. The single randomized controlled trial was assessed using the ROB2 tool and rated as having some concerns due to missing outcome data. Detailed results are provided in Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material Table S2 and Figures S1 and S2).

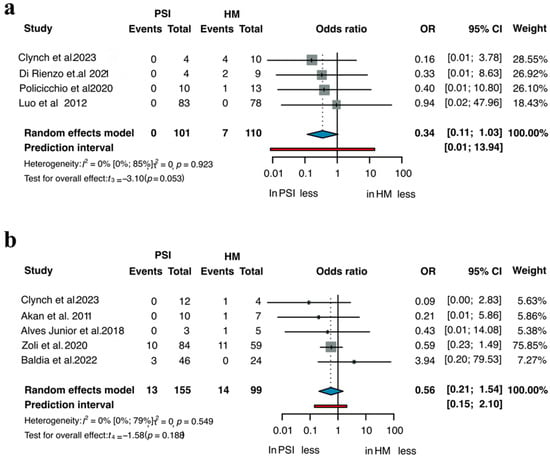

3.3. Implant Removal

A total of eight comparative two-arm studies allowed for the evaluation of implant removal rates between PSIs and HM implants [3,22,28,40,45,83,102,138]. Separate subgroup analyses were performed for titanium and PMMA implants, as illustrated in Figure 2. Across studies including 101 patients treated with PSIs and 110 patients with HM titanium implants, the OR for implant removal was 0.34 in favor of PSIs (95% CI 0.11–1.03; p = 0.053). In studies involving 155 patients in the PMMA PSI group and 99 in the HM group, the OR was 0.56 (95% CI 0.21–1.54; p = 0.188), again indicating a trend toward fewer removals in the PSI group, though not statistically significant. Table S3 summarizes the results of the one arm analyses for implant removal, showing that all PSI materials demonstrated lower probabilities of explantation compared to HM implants of the same material. Across all included studies, PSIs consistently reduced the risk of postoperative removal, with titanium and PMMA PSIs showing lower rates than their HM counterparts, with the strongest effect being observed for titanium (Figure 3a). In pooled analyses, PSI materials such as CaP-titanium and hydroxyapatite exhibited the lowest explantation rates (<6%), whereas HM PMMA showed the highest rate (14.2%). These findings indicate a consistent advantage of PSIs across materials, although statistical significance was not uniformly achieved in the two-arm subgroup comparisons.

Figure 2.

Removal of (a) Titanium and (b) PMMA implants across all two-arm studies [3,22,28,40,45,83,102,138].

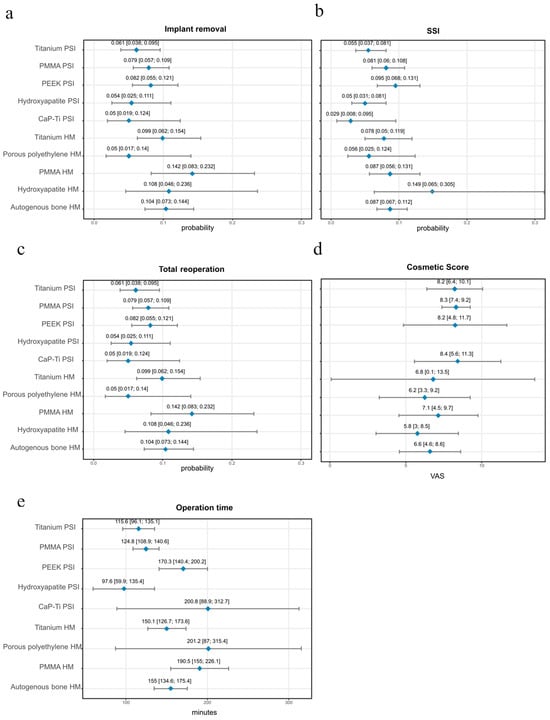

Figure 3.

Visualized Meta-Regression estimates with 95% CI for implant materials. None of the single-arm analyses reached statistical significance. (a) Implant removal; (b) SSI; (c) Total reoperation; (d) Cosmetic Score; (e) Operation time. PSI: Patient-Specific Implant, HM: Hand-molded, SSI: Surgical Side Infection, CI: Confidence Interval, VAS: Visual Analogue Scale, PMMA: Polymethylmethacrylate, PEEK: Polyetheretherketone, CI: Confidence Interval.

3.4. SSI

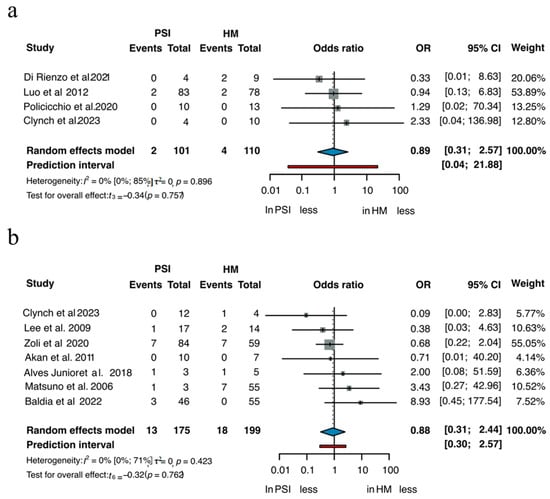

Ten studies enabled direct comparison of SSI between PSIs and HM implants. Subgroup analyses by material are shown in Figure 4 [3,22,28,40,45,77,83,88,102,138]. Among 101 patients treated with PSIs and 110 with HM titanium implants, the OR for SSI was 0.89 in favor of PSIs (95% CI 0.31–2.57, p = 0.757). In the PMMA group, which included 175 PSI cases and 199 HM, the OR was 0.88 (95% CI 0.31–2.44, p = 0.762). In both comparisons, the differences in infection rates were not statistically significant, although the point estimates slightly favored PSI.

Figure 4.

SSI of (a) Titanium and (b) PMMA [3,22,28,40,45,77,83,88,102,138].

Table S4 summarizes the one-arm analyses of SSI. Infection rates varied across materials, with several PSIs, including CaP-titanium, hydroxyapatite, and titanium, showing postoperative infection probabilities below 6%. PMMA and PEEK PSIs demonstrated infection rates between 8.1% and 9.5%. Among the HM implants, autologous bone and PMMA showed infection rates of 8.7%, while hydroxyapatite reached the highest proportion at 14.9% (Figure 3b).

3.5. Total Reoperation

Table S5 summarizes the results of the one-arm analyses for total reoperations. PSIs showed lower reoperation proportions across most materials compared to HM implants (Figure 3c). The lowest PSI reoperation rates were observed for CaP-Ti (4.7%) and Hydroxyapatite (6.7%), while higher rates were found for PEEK (10.6%) and PMMA (10.8%). Among the HM implants, hydroxyapatite, autologous bone and PMMA exhibited reoperation rates of 11%, with titanium reaching the highest value at 12.6%.

3.6. Operation Time

Table S6 presents the pooled analysis of operation times across materials. Procedures performed with PSIs were generally shorter than those with HM implants. The mean duration for PSIs ranged from 98 min for hydroxyapatite to 201 min for Porous polyethylene, with titanium and PMMA PSIs averaging around 116 and 125 min, respectively (Figure 3e). In contrast, HM implants required longer operative times, with titanium averaging 151 min, autologous bone 156 min, and PMMA nearly 191 min, representing the longest recorded duration among all materials. These findings highlight a consistent reduction in surgical time when using PSI, particularly for titanium and PMMA, where differences exceeded 35–65 min compared to their HM counterparts.

3.7. Cosmetic Score

Table S7 displays the cosmetic outcomes assessed by visual analogue scale (VAS, 0–10, with 10 indicating the highest satisfaction). Across the included studies, PSIs consistently achieved higher cosmetic ratings compared to HM implants (Figure 3d). Mean scores for PSI materials generally ranged between 8.2 and 8.4, reflecting favorable esthetic outcomes across titanium, PMMA, PEEK, and hydroxyapatite reconstructions. By contrast, HM implants more frequently scored between 5.8 and 7.1, indicating moderate satisfaction but a clear reduction compared with PSI. The widest gap was observed for PMMA, where PSI reconstructions approached VAS scores of 8.3, whereas HM PMMA averaged closer to 7.1. Although the mean differences often appear small (1.2 VAS points), this shift typically represents the transition from “acceptable” to “near-perfect” esthetics in CP, where psychosocial reintegration and patient self-image are central, such improvements are clinically meaningful.

3.8. Implant Price

Table S8 summarizes the reported implant costs across included studies. Prices varied substantially depending on material and implant type. Among PSI materials, PEEK showed the highest average costs, ranging from approximately USD 14414 to 27902 per implant. Titanium PSIs were reported between USD 5627 and 7858, while PMMA PSIs were substantially lower, with reported prices ranging from USD 398 to 5565. HM titanium implants were less expensive, reported between USD 2143 and 2893.

3.9. Certainty of Evidence

The certainty of evidence for the two-arm studies was evaluated using the GRADE system and was overall rated as low. A detailed assessment is presented in Supplementary Material (Supplementary Material Figure S3).

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

This study presents the most comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis to date comparing PSIs and HM implants in CP. Overall, the findings suggest that PSI, regardless of the material used, may offer superior outcomes in terms of surgical efficiency and postoperative complications. Specifically, PSIs were associated with shorter operation times, reduced odds of implant removal and fewer overall secondary operations compared to HM alternatives. These trends were observed consistently across materials such as titanium, PMMA, and hydroxyapatite, highlighting the potential benefits of preoperative customization in cranioplasty procedures. However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to the high heterogeneity among the included studies, including variations in surgical technique, patient populations and follow-up duration. Moreover, none of the single-arm analyses reached statistical significance.

4.2. Material-Specific Considerations

Although customized implant technologies involve greater cost and effort, their superiority over conventional HM systems has not been clearly demonstrated, a finding similar to that in several single-center studies [40,99,129,138]. HM PMMA implants gained popularity for decades as a practical and inexpensive option in CP. Their widespread use was driven by immediate intraoperative availability, low material cost, and the relative ease of shaping PMMA directly at the surgical site to match the defect. Several single-center reports emphasized its value as a rapid solution, especially in settings with limited resources or when custom-made prostheses were not accessible [77,138]. Despite these advantages, however, outcomes varied considerably depending on defect size, anatomical location, and the surgeon’s experience, underlining both the appeal and the limitations of this technique [139]. In our analysis, the two-arm comparison favored PSI PMMA, and the meta-regression estimated the explantation probability of HM PMMA at 14.2%. The high rate of explantation seen with HM PMMA can be attributed to its material-specific limitations, particularly residual monomer toxicity arising from intraoperative polymerization. The exothermic reaction and the use of autopolymerizing PMMA, often with suboptimal ratios of monomer to powder, can lead to excess unreacted monomers. These substances have been shown to cause cytotoxic effects, inflammatory responses, and even neurotoxicity when monomers are inadvertently dispersed into the brain during cooling with saline [22]. Moreover, direct contact with the dura and the need for intraoperative shaping and drilling may further increase the risk of foreign body responses, ultimately contributing to implant failure and removal [140]. PEEK was also associated with relatively high rates of both implant removal (8.2%) and SSI (9.5%) compared to other PSI, which likely reflects its frequent use in complex, high-risk reconstructions [23,31]. PEEK is often chosen for more complex or high-risk cases, such as large cranial defects, syndromic conditions, or tumor resections, where PSIs are preferred for their precise fit.

4.3. Influence of Surgical and Patient Factors

The timing between craniectomy and CP appears to have a notable influence on postoperative outcomes. Performing CP too early may increase the risk of complications such as infection and inflammation, likely due to residual contamination, incomplete resolution of cerebral edema, or compromised wound healing. Conversely, delayed CP can lead to extensive dural scarring, bone resorption or brain atrophy, which may complicate implant integration [141]. However, according to a recent meta-analysis by Malcolm et al., no significant difference in postoperative complication rates was observed when comparing early (<90 days) versus delayed (>90 days) CP [142]. Anatomical factors may also influence complication rates. Frontal bone defects, which were present in several included studies, are associated with thinner soft tissue coverage, potentially increasing the risk of implant exposure and chronic inflammatory response, particularly when using materials with known toxicity profiles. Moreover, preoperative radiotherapy is a well-documented factor that significantly worsens surgical outcomes, increasing the risk of postoperative complications by up to sevenfold [143]. Radiation alters local vascularity, impairs tissue regeneration, and induces chronic inflammation, all of which can compromise wound healing and promote implant-related complications, including implant failure. These patients typically present with longer operative times and higher complication risks, both contributing to elevated postoperative infection rates [100]. This trend is consistent with our findings of PEEK PSIs having one of the longest average operation times (170.34 min). In contrast, other PSI, such as hydroxyapatite, titanium, and PMMA demonstrated shorter operation times, which is likely due to their precise preoperative planning and optimal fit, reducing the need for intraoperative adjustments. On the other end of the spectrum, HM PMMA showed one of the longest overall operation time (190.54 min), which may be explained by the intraoperative polymerization process and the need for manual sculpting and fitting during surgery, steps that can be time-consuming and technically demanding [22]. The 35–65 min reduction observed with titanium and PMMA PSIs may have broader consequences, including shorter anesthesia duration, reduced intraoperative blood loss, and potentially fewer infection-related complications, which are particularly relevant in critically ill or polytrauma patients [144].

4.4. Biological and Biomechanical Factors Underlying Outcomes

Infection rates in our analysis ranged from a postoperative probability of 2.9% to 14.9%, with the highest observed in HM hydroxyapatite implants (14.9%). The elevated infection rate in HM hydroxyapatite may be attributed to challenges in intraoperative handling, increased porosity, and suboptimal fit, all of which can compromise soft tissue closure and increase contamination risk [101]. By contrast, CaP-Ti PSIs demonstrated the lowest infection probability (2.9%), followed by titanium PSIs (5.5%) and PMMA PSIs (8.1%). PEEK PSIs showed relatively high infection rates (9.5%), consistent with its bioinert, non-osseointegrating properties, while autologous bone and PMMA HM also demonstrated elevated risks (8.7% each). When considering overall reoperations, a similar pattern emerged. Beyond infection and revision rates, the biological interaction between implant and host tissue provides further explanation. PEEK, while widely used, is hydrophobic and bioinert, limiting osteoblast adhesion and preventing osseointegration, which may predispose it to implant migration and infection. In contrast, CaP-Ti implants promote neovascularization and bone ingrowth, enhancing stability, wound healing, and even allowing local antibiotic release when pre-soaked in gentamicin [100]. Similarly, hydroxyapatite supports osseointegration, although its brittleness can increase fracture susceptibility [5]. These findings highlight that, in addition to mechanical properties and surgical handling, implant biocompatibility plays a critical role in long-term CP outcomes.

4.5. Economic Considerations

Titanium has long been a favored material for CP due to its biocompatibility, strength, and ease of shaping. HM titanium meshes offer a relatively inexpensive solution, with costs reported around USD 1500 for large implants, whereas computer-aided patient-specific titanium implants are typically two to three times more expensive (USD 2700–7800 depending on size and manufacturer). Despite the higher cost, PSIs reduce implant removals and secondary reoperations, potentially offsetting expenses in high-resource healthcare systems, while HM meshes remain attractive in resource-limited settings where affordability is a primary concern [83].

4.6. Strengths and Limitations

The main strength of this study lies in its comprehensive scope and methodological detail. By including all major implant materials and explicitly separating patient-specific from HM implants, this analysis provides a more precise and transparent comparison than previous reviews. This approach allows for a clearer understanding of recovery dynamics and the relative effectiveness of different implant types. Furthermore, the breadth of the dataset, which represents the largest synthesis of CP outcomes to date, enhances the robustness of the findings and supports their applicability across a wide clinical spectrum. Despite these strengths, several limitations should be acknowledged. The included studies demonstrated a high degree of heterogeneity, with notable variation in surgical techniques, patient populations, and the way outcomes were reported. In addition, differences in how studies defined and classified events likely introduced further residual heterogeneity. Together, these factors complicate direct comparability across studies. Importantly, nearly all of the available evidence derives from observational studies, with only a single randomized controlled trial included. This reliance on non-randomized data increases the risk of bias and limits the strength of causal inferences. Additionally, the literature provides little clarity on the clinical decision-making process regarding when a PSI or HM implant should be preferred, restricting the ability to draw practice-oriented recommendations. While these limitations do not diminish the relevance of the findings, they emphasize the need for cautious interpretation and for future high-quality prospective studies to establish clearer guidance.

4.7. Implications for Practice and Implications for Research

Translating scientific evidence into daily surgical decision-making is essential [145,146]. Where financial resources and technical infrastructure allow, PSIs should be prioritized. Their tailored design improves intraoperative precision, reduces operative time, and lowers the likelihood of complications, making them particularly valuable in complex reconstructions, frontal bone reconstructions with limited soft tissue coverage, or in cases where anatomical accuracy is critical. Conversely, HM implants remain an important option in situations for smaller defects or in emergency situations where custom fabrication is not feasible.

From a research perspective, greater transparency in reporting is required, including the consistent provision of raw outcome data and standardized definitions of complications. Future studies should not only compare patient-specific and HM implants across different materials but also aim to establish clearer criteria for implant selection in clinical practice. Although materials were analyzed separately to avoid inappropriate cross-material pooling, exploring correlations or hierarchical relationships between materials may help identify broader patterns of implant performance. Such analyses represent an important direction for future research.

5. Conclusions

Across materials, PSIs were associated with favorable trends in shorter operative time, less explantations, fewer reoperations, and better cosmetic satisfaction compared with HM implants, highlighting the benefits of preoperative customization. However, most data derive from observational cohorts, and many direct comparisons were not statistically significant. Therefore, these findings should be interpreted as associative rather than demonstrating proven superiority.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14248655/s1, Text S1: Predefined search key, Figure S1: RoB 2 assessment, Figure S2: ROBINS-I. assessment for (a) implant removal and (b) SSI, Figure S3: GRADE assessment for all subgroups, Table S1: PRISMA Checklist, Table S2: MINORS assessment for single-arm studies, Table S3: Implant removal across all one-arm studies, Table S4: SSI across all one-arm studies, Table S5: Total number of reoperations across all one-arm studies, Table S6: Operation time in minutes, Table S7: Cosmetic Score on VAS (0–10), Table S8: Implant Price in USD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.-L.N., B.K.G.C., K.S.B.-J., A.S.W., B.L.S., G.A., Z.N., M.K., P.H., L.K. and M.V.; methodology, E.-L.N. and A.S.W.; formal analysis, E.-L.N., B.L.S. and G.A.; data curation, E.-L.N., B.K.G.C. and K.S.B.-J.; writing—original draft, E.-L.N., L.K. and M.V.; writing—review and editing, B.K.G.C., K.S.B.-J., A.S.W., B.L.S., G.A., Z.N., M.K. and P.H.; visualization, B.L.S. and G.A.; supervision, L.K. and M.V.; project administration, E.-L.N.; funding acquisition, L.K. All authors certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for the content, including participation in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Ministry of Innovation and Technology of Hungary from the National Research, Development, and Innovation Fund, financed under the TKP2021-EGA-23 funding scheme. Sponsors had no role in the design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, and manuscript preparation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used in this study can be found in the full-text articles included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. If further information is needed, it will be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT-5 only for sentence rephrasing and grammar correction. After utilizing this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zegers, T.; Ter Laak-Poort, M.; Koper, D.; Lethaus, B.; Kessler, P. The therapeutic effect of patient-specific implants in cranioplasty. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 82–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binhammer, A.; Jakubowski, J.; Antonyshyn, O.; Binhammer, P. Comparative Cost-Effectiveness of Cranioplasty Implants. Plast. Surg. 2020, 28, 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves Junior, A.C.; Hamamoto Filho, P.T.; Gonçalves, M.P.; Palhares Neto, A.A.; Zanini, M.A. Cranioplasty: An Institutional Experience. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, 1402–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, S.I.; Thomson, K.B.; Maasarani, S.; Wiegmann, A.L.; Smith, J.; Adogwa, O.; Mehta, A.I.; Dorafshar, A.H. Materials Used in Cranial Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World Neurosurg. 2022, 164, e945–e963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lindner, D.; Schlothofer-Schumann, K.; Kern, B.C.; Marx, O.; Müns, A.; Meixensberger, J. Cranioplasty using custom-made hydroxyapatite versus titanium: A randomized clinical trial. J. Neurosurg. 2017, 126, 175–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.G.; Ko, Y.; Kim, Y.S.; Bak, K.H.; Chun, H.J.; Na, M.K.; Yang, S.; Yi, H.J.; Choi, K.S. Efficacy of 3D-Printed Titanium Mesh-Type Patient-Specific Implant for Cranioplasty. Korean J. Neurotrauma 2021, 17, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxena, V.; Sahoo, N.K.; Rangarajan, H.; Sehgal, A. “Bridging the Breach”: Cranioplasties Using Different Reconstruction Materials-An Institutional Experience. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2023, 22, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarjuna, M.; Ganesh, P.; Srinivasaiah, V.S.; Kumar, K.; Shetty, S.; Salins, P.C. Fabrication of Patient Specific Titanium Implants for Correction of Cranial Defects: A Technique to Improve Anatomic Contours and Accuracy. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, 2409–2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moellmann, H.L.; Mehr, V.N.; Karnatz, N.; Wilkat, M.; Riedel, E.; Rana, M. Evaluation of the Fitting Accuracy of CAD/CAM-Manufactured Patient-Specific Implants for the Reconstruction of Cranial Defects-A Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino, C.; Kolias, A.; Adelson, P.D.; Rubiano, A.M.; Viaroli, E.; Buki, A.; Cinalli, G.; Fountas, K.; Khan, T.; Signoretti, S.; et al. Consensus statement from the international consensus meeting on post-traumatic cranioplasty. Acta Neurochir. 2021, 163, 423–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolden, E.L.; Carvalho, B.K.G.; Wenning, A.S.; Kiss-Dala, S.; Hegyi, P.; Bródy, A.; Rózsa, N.K.; Végh, D.; Köles, L.; Vaszilkó, M. Comparative efficacy of patient-specific and stock implants in temporomandibular joint replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.; Amoo, M.; Taylor, J.; O’Brien, D.P. Complications of Cranioplasty in Relation to Material: Systematic Review, Network Meta-Analysis and Meta-Regression. Neurosurgery 2021, 89, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerveau, T.; Rossmann, T.; Clusmann, H.; Veldeman, M. Infection-related failure of autologous versus allogenic cranioplasty after decompressive hemicraniectomy—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Spine 2023, 3, 101760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5. Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Hegyi, P.; Varró, A. Systems education can train the next generation of scientists and clinicians. Nat. Med. 2024, 30, 3399–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73, 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- GRADEpro GDT: GRADEpro Guideline Development Tool [Software]. McMaster University and Evidence Prime. 2023. Available online: https://www.gradepro.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Harrer, M.; Cuijpers, P.; Furukawa, T.; Ebert, D. Doing Meta-Analysis with R: A Hands-On Guide; Chapman and Hall/CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Higgins, J.P.; Thompson, S.G. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat. Med. 2002, 21, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akan, M.; Karaca, M.; Eker, G.; Karanfil, H.; Aköz, T. Is polymethylmethacrylate reliable and practical in full-thickness cranial defect reconstructions? J. Craniofac. Surg. 2011, 22, 1236–1239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Alawi, K.; Al Furqani, A.; Al Shaqsi, S.; Shummo, M.; Al Jabri, A.; Al Balushi, T. Cranioplasty in Oman: Retrospective review of cases from the National Craniofacial Center 2012–2022. Sultan Qaboos Univ. Med. J. 2024, 24, 250–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.R.; Islam, K.T.; Haque, M. Preoperative planning of craniectomy and reconstruction using three-dimension-printed cranioplasty for treatment of calvarial lesion. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2024, 15, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anele, C.O.; Balogun, S.A.; Ezeaku, C.O.; Ajekwu, T.O.; Omon, H.E.; Ejembi, G.O.; Komolafe, E.O. Titanium mesh cranioplasty for cosmetically disfiguring cranio-facial tumours in a resource limited setting. World Neurosurg. X 2024, 23, 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anto, D.; Manjooran, R.P.; Aravindakshan, R.; Lakshman, K.; Morris, R. Cranioplasty Using Autoclaved Autologous Skull Bone Flaps Preserved at Ambient Temperature. J. Neurosci. Rural. Pract. 2017, 8, 595–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Choudhary, N.; Kamboh, U.A.; Raza, M.A.; Sultan, K.A.; Ghulam, N.; Hussain, S.S.; Ashraf, N. Early experience with patient-specific low-cost 3D-printed polymethylmethacrylate cranioplasty implants in a lower-middle-income-country: Technical note and economic analysis. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2022, 13, 270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldia, M.; Joseph, M.; Sharma, S.; Kumar, D.; Retnam, A.; Koshy, S.; Karuppusami, R. Customized cost-effective polymethylmethacrylate cranioplasty: A cosmetic comparison with other low-cost methods of cranioplasty. Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 655–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, B.; Bhaskar, N.; Barui, S.; Sharma, V.; Das, S.; Govindarajan, N.; Hegde, P.; Perikal, P.J.; Antharasanahalli Shivakumar, M.; Khanapure, K.; et al. Evaluation of implant properties, safety profile and clinical efficacy of patient-specific acrylic prosthesis in cranioplasty using 3D binderjet printed cranium model: A pilot study. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 85, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F.; Signorelli, F.; Di Bonaventura, R.; Trevisi, G.; Pompucci, A. One-stage frame-guided resection and reconstruction with PEEK custom-made prostheses for predominantly intraosseous meningiomas: Technical notes and a case series. Neurosurg. Rev. 2019, 42, 769–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandicourt, P.; Delanoé, F.; Roux, F.E.; Jalbert, F.; Brauge, D.; Lauwers, F. Reconstruction of Cranial Vault Defect with Polyetheretherketone Implants. World Neurosurg. 2017, 105, 783–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brie, J.; Chartier, T.; Chaput, C.; Delage, C.; Pradeau, B.; Caire, F.; Boncoeur, M.P.; Moreau, J.J. A new custom made bioceramic implant for the repair of large and complex craniofacial bone defects. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2013, 41, 403–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabraja, M.; Klein, M.; Lehmann, T.N. Long-term results following titanium cranioplasty of large skull defects. Neurosurg. Focus. 2009, 26, E10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro-Osorio, E.; De la Garza-Ramos, R.; Martínez-Sánchez, S.R.; Olazarán-Salinas, F. Cranioplasty with polymethylmethacrylate prostheses fabricated by hand using original bone flaps: Technical note and surgical outcomes. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2013, 4, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champeaux, C.; Froelich, S.; Caudron, Y. Titanium Three-Dimensional Printed Cranioplasty for Fronto-Nasal Bone Defect. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 1802–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S.T.; Chang, C.J.; Su, W.C.; Chang, L.W.; Chu, I.H.; Lin, M.S. 3-D titanium mesh reconstruction of defective skull after frontal craniectomy in traumatic brain injury. Injury 2015, 46, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Sun, J.; Wang, J.C. Clinical Outcomes of Digital Three-Dimensional Hydroxyapatite in Repairing Calvarial Defects. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, 618–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.K.; Weng, H.H.; Yang, J.T.; Lee, M.H.; Wang, T.C.; Chang, C.N. Factors affecting graft infection after cranioplasty. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2008, 15, 1115–1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.H.; Chuang, H.Y.; Lin, H.L.; Liu, C.L.; Yao, C.H. Surgical results of cranioplasty using three-dimensional printing technology. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2018, 168, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clynch, A.L.; Norrington, M.; Mustafa, M.A.; Richardson, G.E.; Doherty, J.A.; Humphries, T.J.; Gillespie, C.S.; Keshwara, S.M.; McMahon, C.J.; Islim, A.I.; et al. Cranial meningioma with bone involvement: Surgical strategies and clinical considerations. Acta Neurochir. 2023, 165, 1355–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Couldwell, W.T.; Chen, T.C.; Weiss, M.H.; Fukushima, T.; Dougherty, W. Cranioplasty with the Medpor porous polyethylene flexblock implant. Technical note. J. Neurosurg. 1994, 81, 483–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Csámer, L.; Csernátony, Z.; Novák, L.; Kővári, V.Z.; Kovács, Á.; Soósné Horváth, H.; Manó, S. Custom-made 3D printing-based cranioplasty using a silicone mould and PMMA. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 11985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva Júnior, E.B.; de Aragão, A.H.; de Paula Loureiro, M.; Lobo, C.S.; Oliveti, A.F.; de Oliveira, R.M.; Ramina, R. Cranioplasty with three-dimensional customised mould for polymethylmethacrylate implant: A series of 16 consecutive patients with cost-effectiveness consideration. 3D Print Med. 2021, 7, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, J.B. Cost-Effective Technique of Fabrication of Polymethyl Methacrylate Based Cranial Implant Using Three-Dimensional Printed Moulds and Wax Elimination Technique. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 1259–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rienzo, A.; Colasanti, R.; Gladi, M.; Dobran, M.; Della Costanza, M.; Capece, M.; Veccia, S.; Iacoangeli, M. Timing of cranial reconstruction after cranioplasty infections: Are we ready for a re-thinking? A comparative analysis of delayed versus immediate cranioplasty after debridement in a series of 48 patients. Neurosurg. Rev. 2021, 44, 1523–1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đurić, K.S.; Barić, H.; Domazet, I.; Barl, P.; Njirić, N.; Mrak, G. Polymethylmethacrylate cranioplasty using low-cost customised 3D printed moulds for cranial defects—A single Centre experience: Technical note. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 33, 376–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eom, K.S. Single-Stage Reconstruction with Titanium Mesh for Compound Comminuted Depressed Skull Fracture. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2020, 63, 631–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eufinger, H.; Wehmöller, M. Individual prefabricated titanium implants in reconstructive craniofacial surgery: Clinical and technical aspects of the first 22 cases. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998, 102, 300–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, A.J.; Lemelman, B.T.; Lam, S.; Kleiber, G.M.; Reid, R.R.; Gottlieb, L.J. Reconstructive approach to hostile cranioplasty: A review of the University of Chicago experience. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2015, 68, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fountain, D.M.; Henry, J.; Honeyman, S.; O’Connor, P.; Sekhon, P.; Piper, R.J.; Edlmann, E.; Martin, M.; Whiting, G.; Turner, C.; et al. First Report of a Multicenter Prospective Registry of Cranioplasty in the United Kingdom and Ireland. Neurosurgery 2021, 89, 518–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francaviglia, N.; Maugeri, R.; Odierna Contino, A.; Meli, F.; Fiorenza, V.; Costantino, G.; Giammalva, R.G.; Iacopino, D.G. Skull Bone Defects Reconstruction with Custom-Made Titanium Graft shaped with Electron Beam Melting Technology: Preliminary Experience in a Series of Ten Patients. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2017, 124, 137–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ganau, M.; Cebula, H.; Fricia, M.; Zaed, I.; Todeschi, J.; Scibilia, A.; Gallinaro, P.; Coca, A.; Chaussemy, D.; Ollivier, I.; et al. Surgical preference regarding different materials for custom-made allograft cranioplasty in patients with calvarial defects: Results from an internal audit covering the last 20 years. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2020, 74, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giese, H.; Meyer, J.; Engel, M.; Unterberg, A.; Beynon, C. Polymethylmethacrylate patient-matched implants (PMMA-PMI) for complex and revision cranioplasty: Analysis of long-term complication rates and patient outcomes. Brain Inj. 2020, 34, 269–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilardino, M.S.; Karunanayake, M.; Al-Humsi, T.; Izadpanah, A.; Al-Ajmi, H.; Marcoux, J.; Atkinson, J.; Farmer, J.P. A comparison and cost analysis of cranioplasty techniques: Autologous bone versus custom computer-generated implants. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, R.C.; Chang, C.N.; Lin, C.L.; Lo, L.J. Customised fabricated implants after previous failed cranioplasty. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2010, 63, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamböck, M.; Hosmann, A.; Seemann, R.; Wolf, H.; Schachinger, F.; Hajdu, S.; Widhalm, H. The impact of implant material and patient age on the long-term outcome of secondary cranioplasty following decompressive craniectomy for severe traumatic brain injury. Acta Neurochir. 2020, 162, 745–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Ma, Y.; Yang, C.; Hui, J.; Mao, Q.; Gao, G.; Jiang, J.; Feng, J. A Perioperative Paradigm of Cranioplasty with Polyetheretherketone: Comprehensive Management for Preventing Postoperative Complications. Front. Surg. 2022, 9, 856743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heissler, E.; Fischer, F.S.; Bolouri, S.; Lehmann, T.; Mathar, W.; Gebhardt, A.; Lanksch, W.; Bier, J. Custom-made cast titanium implants produced with CAD/CAM for the reconstruction of cranium defects. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1998, 27, 334–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, B.; Sepehrnia, A. Taylored implants for alloplastic cranioplasty--clinical and surgical considerations. Acta Neurochir. Suppl. 2005, 93, 127–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Honeybul, S.; Ho, K.M. How “successful” is calvarial reconstruction using frozen autologous bone? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012, 130, 1110–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosameldin, A.; Osman, A.; Hussein, M.; Gomaa, A.F.; Abdellatif, M. Three dimensional custom-made PEEK cranioplasty. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2021, 12, 587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.J.; Zhong, S.; Susarla, S.M.; Swanson, E.W.; Huang, J.; Gordon, C.R. Craniofacial reconstruction with poly(methyl methacrylate) customized cranial implants. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, 64–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iaccarino, C.; Viaroli, E.; Fricia, M.; Serchi, E.; Poli, T.; Servadei, F. Preliminary Results of a Prospective Study on Methods of Cranial Reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 2375–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, A.; Satoh, S.; Sekiguchi, K.; Ibuchi, Y.; Katoh, S.; Ota, K.; Fujimori, S. Cranioplasty with split-thickness calvarial bone. Neurol. Med. Chir. 1995, 35, 804–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iratwar, S.; Roy Chowdhury, S.; Pisulkar, S.; Das, S.; Agarwal, A.; Bagde, A.; Paikrao, B.; Quazi, S.; Basu, B. Comprehensive functional outcome analysis and importance of bone remodelling on personalized cranioplasty treatment using Poly(methyl methacrylate) bone flaps. J. Biomater. Appl. 2024, 38, 975–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaberi, J.; Gambrell, K.; Tiwana, P.; Madden, C.; Finn, R. Long-term clinical outcome analysis of poly-methyl-methacrylate cranioplasty for large skull defects. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013, 71, e81–e88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Y.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, X. Effect of Reflection of Temporalis Muscle During Cranioplasty with Titanium Mesh After Standard Trauma Craniectomy. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonkergouw, J.; van de Vijfeijken, S.E.; Nout, E.; Theys, T.; Van de Casteele, E.; Folkersma, H.; Depauw, P.R.; Becking, A.G. Outcome in patient-specific PEEK cranioplasty: A two-center cohort study of 40 implants. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2016, 44, 1266–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.J.; Hong, K.S.; Park, K.J.; Park, D.H.; Chung, Y.G.; Kang, S.H. Customized cranioplasty implants using three-dimensional printers and polymethyl-methacrylate casting. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2012, 52, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.K.; Lee, S.B.; Yang, S.Y. Cranioplasty Using Autologous Bone versus Porous Polyethylene versus Custom-Made Titanium Mesh: A Retrospective Review of 108 Patients. J. Korean Neurosurg. Soc. 2018, 61, 737–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.C.; Lee, S.J.; Woo, S.H.; Yang, S.; Choi, J.W. A Comparative Study of Titanium Cranioplasty for Extensive Calvarial Bone Defects: Three-Dimensionally Printed Titanium Implants Versus Premolded Titanium Mesh. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2023, 91, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiyokawa, K.; Hayakawa, K.; Tanabe, H.Y.; Inoue, Y.; Tai, Y.; Shigemori, M.; Tokutomi, T. Cranioplasty with split lateral skull plate segments for reconstruction of skull defects. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 1998, 26, 379–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohan, E.; Roostaeian, J.; Yuan, J.T.; Fan, K.L.; Federico, C.; Kawamoto, H.; Bradley, J.P. Customized bilaminar resorbable mesh with BMP-2 promotes cranial bone defect healing. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2015, 74, 603–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kung, W.M.; Lin, F.H.; Hsiao, S.H.; Chiu, W.T.; Chyau, C.C.; Lu, S.H.; Hwang, B.; Lee, J.H.; Lin, M.S. New reconstructive technologies after decompressive craniectomy in traumatic brain injury: The role of three-dimensional titanium mesh. J. Neurotrauma 2012, 29, 2030–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kung, W.M.; Lin, M.S. A simplified technique for polymethyl methacrylate cranioplasty: Combined cotton stacking and finger fracture method. Brain Inj. 2012, 26, 1737–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiecien, G.J.; Rueda, S.; Couto, R.A.; Hashem, A.; Nagel, S.; Schwarz, G.S.; Zins, J.E.; Gastman, B.R. Long-term Outcomes of Cranioplasty: Titanium Mesh Is Not a Long-term Solution in High-risk Patients. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2018, 81, 416–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.C.; Wu, C.T.; Lee, S.T.; Chen, P.J. Cranioplasty using polymethyl methacrylate prostheses. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2009, 16, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Chung, Y.S.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, H.J.; Son, Y.J. Analysis of the factors influencing bone graft infection after cranioplasty. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2012, 73, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.H.; Yoo, C.J.; Lee, U.; Park, C.W.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, W.K. Resorption of Autogenous Bone Graft in Cranioplasty: Resorption and Reintegration Failure. Korean J. Neurotrauma 2014, 10, 10–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemée, J.M.; Petit, D.; Splingard, M.; Menei, P. Autologous bone flap versus hydroxyapatite prosthesis in first intention in secondary cranioplasty after decompressive craniectomy: A French medico-economical study. Neurochirurgie 2013, 59, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lethaus, B.; Bloebaum, M.; Koper, D.; Poort-Ter Laak, M.; Kessler, P. Interval cranioplasty with patient-specific implants and autogenous bone grafts--success and cost analysis. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2014, 42, 1948–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kihlström Burenstam Linder, L.; Birgersson, U.; Lundgren, K.; Illies, C.; Engstrand, T. Patient-Specific Titanium-Reinforced Calcium Phosphate Implant for the Repair and Healing of Complex Cranial Defects. World Neurosurg. 2019, 122, e399–e407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Liu, B.; Xie, Z.; Ding, S.; Zhuang, Z.; Lin, L.; Guo, Y.; Chen, H.; Yu, X. Comparison of manually shaped and computer-shaped titanium mesh for repairing large frontotemporoparietal skull defects after traumatic brain injury. Neurosurg. Focus. 2012, 33, E13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maenhoudt, W.; Hallaert, G.; Kalala, J.P.; Baert, E.; Dewaele, F.; Bauters, W.; Van Roost, D. Hydroxyapatite cranioplasty: A retrospective evaluation of osteointegration in 17 cases. Acta Neurochir. 2018, 160, 2117–2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marbacher, S.; Andereggen, L.; Erhardt, S.; Fathi, A.R.; Fandino, J.; Raabe, A.; Beck, J. Intraoperative template-molded bone flap reconstruction for patient-specific cranioplasty. Neurosurg. Rev. 2012, 35, 527–535; discussion 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maricevich, J.; Cezar-Junior, A.B.; de Oliveira-Junior, E.X.; Veras, E.S.J.A.M.; da Silva, J.V.L.; Nunes, A.A.; Almeida, N.S.; Azevedo-Filho, H.R.C. Functional and aesthetic evaluation after cranial reconstruction with polymethyl methacrylate prostheses using low-cost 3D printing templates in patients with cranial defects secondary to decompressive craniectomies: A prospective study. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2019, 10, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marlier, B.; Kleiber, J.C.; Bannwarth, M.; Theret, E.; Eap, C.; Litre, C.F. Reconstruction of cranioplasty using medpor porouspolyethylene implant. Neurochirurgie 2017, 63, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuno, A.; Tanaka, H.; Iwamuro, H.; Takanashi, S.; Miyawaki, S.; Nakashima, M.; Nakaguchi, H.; Nagashima, T. Analyses of the factors influencing bone graft infection after delayed cranioplasty. Acta Neurochir. 2006, 148, 535–540; discussion 540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moles, A.; Heudes, P.M.; Amelot, A.; Cristini, J.; Salaud, C.; Roualdes, V.; Riem, T.; Martin, S.A.; Raoul, S.; Terreaux, L.; et al. Long-Term Follow-Up Comparative Study of Hydroxyapatite and Autologous Cranioplasties: Complications, Cosmetic Results, Osseointegration. World Neurosurg. 2018, 111, e395–e402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Gómez, J.A.; Garcia-Estrada, E.; Leos-Bortoni, J.E.; Delgado-Brito, M.; Flores-Huerta, L.E.; De La Cruz-Arriaga, A.A.; Torres-Díaz, L.J.; de León, Á.R.M. Cranioplasty with a low-cost customized polymethylmethacrylate implant using a desktop 3D printer. J. Neurosurg. 2018, 130, 1721–1727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira-Gonzalez, A.; Jackson, I.T.; Miyawaki, T.; Barakat, K.; DiNick, V. Clinical outcome in cranioplasty: Critical review in long-term follow-up. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2003, 14, 144–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morina, A.; Kelmendi, F.; Morina, Q.; Dragusha, S.; Ahmeti, F.; Morina, D.; Gashi, K. Cranioplasty with subcutaneously preserved autologous bone grafts in abdominal wall-Experience with 75 cases in a post-war country Kosova. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2011, 2, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, R.P.; Abecassis, I.J.; Hanson, J.F.; Barber, J.; Nerva, J.D.; Emerson, S.N.; Ene, C.I.; Chowdhary, M.M.; Levitt, M.R.; Ko, A.L.; et al. Predictors of infection after 754 cranioplasty operations and the value of intraoperative cultures for cryopreserved bone flaps. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 125, 766–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, M.; Schmid, R.; Schindel, R.; Hildebrandt, G. Patient-specific polymethylmethacrylate prostheses for secondary reconstruction of large calvarial defects: A retrospective feasibility study of a new intraoperative moulding device for cranioplasty. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrad, M.A.; Murrad, K.; Antonyshyn, O. Analyzing the Cost of Autogenous Cranioplasty Versus Custom-Made Patient-Specific Alloplastic Cranioplasty. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2017, 28, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ng, Z.Y.; Ang, W.J.; Nawaz, I. Computer-designed polyetheretherketone implants versus titanium mesh (±acrylic cement) in alloplastic cranioplasty: A retrospective single-surgeon, single-center study. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2014, 25, e185–e189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, B.; Ashraf, O.; Richards, R.; Tra, H.; Huynh, T. Cranioplasty Using Customized 3-Dimensional-Printed Titanium Implants: An International Collaboration Effort to Improve Neurosurgical Care. World Neurosurg. 2021, 149, 174–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, E.B.; Barnett, S.; Madden, C.; Welch, B.; Mickey, B.; Rozen, S. Computed-tomography modeled polyether ether ketone (PEEK) implants in revision cranioplasty. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2015, 68, 329–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, C.; Chen, Y.; Mo, J.; Wang, S.; Gai, S.; Xing, R.; Wang, B.; Wu, C. Cranioplasty Using Polymethylmethacrylate Cement Following Retrosigmoid Craniectomy Decreases the Rate of Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak and Pseudomeningocele. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 566–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfnür, A.; Tosin, D.; Petkov, M.; Sharon, O.; Mayer, B.; Wirtz, C.R.; Knoll, A.; Pala, A. Exploring complications following cranioplasty after decompressive hemicraniectomy: A retrospective bicenter assessment of autologous, PMMA and CAD implants. Neurosurg. Rev. 2024, 47, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piitulainen, J.M.; Kauko, T.; Aitasalo, K.M.; Vuorinen, V.; Vallittu, P.K.; Posti, J.P. Outcomes of cranioplasty with synthetic materials and autologous bone grafts. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 708–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Policicchio, D.; Casu, G.; Dipellegrini, G.; Doda, A.; Muggianu, G.; Boccaletti, R. Comparison of two different titanium cranioplasty methods: Custom-made titanium prostheses versus precurved titanium mesh. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2020, 11, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pöppe, J.P.; Spendel, M.; Schwartz, C.; Winkler, P.A.; Wittig, J. The “springform” technique in cranioplasty: Custom made 3D-printed templates for intraoperative modelling of polymethylmethacrylate cranial implants. Acta Neurochir. 2022, 164, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rammos, C.K.; Cayci, C.; Castro-Garcia, J.A.; Feiz-Erfan, I.; Lettieri, S.C. Patient-specific polyetheretherketone implants for repair of craniofacial defects. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ridwan-Pramana, A.; Idema, S.; Te Slaa, S.; Verver, F.; Wolff, J.; Forouzanfar, T.; Peerdeman, S. Polymethyl Methacrylate in Patient-Specific Implants: Description of a New Three-Dimension Technique. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, G.; Ng, I.; Moscovici, S.; Lee, K.K.; Lay, T.; Martin, C.; Manley, G.T. Polyetheretherketone implants for the repair of large cranial defects: A 3-center experience. Neurosurgery 2014, 75, 523–529; discussion 528–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosinski, C.L.; Patel, S.; Geever, B.; Chiu, R.G.; Chaker, A.N.; Zakrzewski, J.; Rosenberg, D.M.; Parola, R.; Shah, K.; Behbahani, M.; et al. A Retrospective Comparative Analysis of Titanium Mesh and Custom Implants for Cranioplasty. Neurosurgery 2020, 86, E15–E22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaru, H.; Stan, H.; Florian, I.S.; Schumacher, R.; Park, Y.T.; Kim, S.G.; Chezan, H.; Balc, N.; Baciut, M. Cranioplasty with custom-made implants: Analyzing the cases of 10 patients. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2012, 70, e169–e176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, N.; Roy, I.D.; Desai, A.P.; Gupta, V. Comparative evaluation of autogenous calvarial bone graft and alloplastic materials for secondary reconstruction of cranial defects. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2010, 21, 79–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, N.K.; Thakral, A.; Janjani, L. Cranioplasty with Autogenous Frozen and Autoclaved Bone: Management and Treatment Outcomes. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2019, 30, 2069–2072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoekler, B.; Trummer, M. Prediction parameters of bone flap resorption following cranioplasty with autologous bone. Clin. Neurol. Neurosurg. 2014, 120, 64–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schön, S.N.; Skalicky, N.; Sharma, N.; Zumofen, D.W.; Thieringer, F.M. 3D-Printer-Assisted Patient-Specific Polymethyl Methacrylate Cranioplasty: A Case Series of 16 Consecutive Patients. World Neurosurg. 2021, 148, e356–e362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharavanan, G.M.; Jayabalan, S.; Rajasukumaran, K.; Veerasekar, G.; Sathya, G. Cranioplasty using presurgically fabricated presterilised polymethyl methacrylate plate by a simple, cost-effective technique on patients with and without original bone flap: Study on 29 patients. J. Maxillofac. Oral. Surg. 2015, 14, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shay, T.; Mitchell, K.A.; Belzberg, M.; Zelko, I.; Mahapatra, S.; Qian, J.; Mendoza, L.; Huang, J.; Brem, H.; Gordon, C. Translucent Customized Cranial Implants Made of Clear Polymethylmethacrylate: An Early Outcome Analysis of 55 Consecutive Cranioplasty Cases. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2020, 85, e27–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Wen, X.; Shi, H.; Qian, T. Application value of calcium phosphate cement in complete cranial reconstructions of microvascular decompression craniectomies. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2023, 85, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, E.; Restrepo, R.D.; Grant, J.H., 3rd; Myers, R.P. Outcomes of Cranioplasty Strategies for High-Risk Complex Cranial Defects: A 10-Year Experience. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2022, 88, S449–S454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Splavski, B.; Lakicevic, G.; Kovacevic, M.; Godec, D. Customized alloplastic cranioplasty of large bone defects by 3D-printed prefabricated mold template after posttraumatic decompressive craniectomy: A technical note. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2022, 13, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staffa, G.; Nataloni, A.; Compagnone, C.; Servadei, F. Custom made cranioplasty prostheses in porous hydroxy-apatite using 3D design techniques: 7 years experience in 25 patients. Acta Neurochir. 2007, 149, 161–170; discussion 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefini, R.; Zanotti, B.; Nataloni, A.; Martinetti, R.; Scafuto, M.; Colasurdo, M.; Tampieri, A. The efficacy of custom-made porous hydroxyapatite prostheses for cranioplasty: Evaluation of postmarketing data on 2697 patients. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2015, 13, e136–e144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stieglitz, L.H.; Gerber, N.; Schmid, T.; Mordasini, P.; Fichtner, J.; Fung, C.; Murek, M.; Weber, S.; Raabe, A.; Beck, J. Intraoperative fabrication of patient-specific moulded implants for skull reconstruction: Single-centre experience of 28 cases. Acta Neurochir. 2014, 156, 793–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Hu, Y.; Yuan, Q.; Yu, J.; Wu, X.; Du, Z.; Wu, X.; Hu, J. Association between metal hypersensitivity and implant failure in patients who underwent titanium cranioplasty. J. Neurosurg. 2019, 131, 40–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundseth, J.; Berg-Johnsen, J. Prefabricated patient-matched cranial implants for reconstruction of large skull defects. J. Cent. Nerv. Syst. Dis. 2013, 5, 19–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tehli, O.; Kirmizigoz, S.; Evleksiz, D.; Izci, Y.; Kutlay, M.; Balci, I.; Ayyildiz, S. Simultaneous Closure of Bilateral Cranial Defects Using Custom-Made 3D Titanium Implants: A Single Institution Series. Turk. Neurosurg. 2023, 33, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tel, A.; Tuniz, F.; Sembronio, S.; Costa, F.; Bresadola, V.; Robiony, M. Cubik system: Maximizing possibilities of in-house computer-guided surgery for complex craniofacial reconstruction. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 50, 1554–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thien, A.; King, N.K.; Ang, B.T.; Wang, E.; Ng, I. Comparison of polyetheretherketone and titanium cranioplasty after decompressive craniectomy. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unterhofer, C.; Wipplinger, C.; Verius, M.; Recheis, W.; Thomé, C.; Ortler, M. Reconstruction of large cranial defects with poly-methyl-methacrylate (PMMA) using a rapid prototyping model and a new technique for intraoperative implant modeling. Neurol. Neurochir. Pol. 2017, 51, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Gool, A.V. Preformed polymethylmethacrylate cranioplasties: Report of 45 cases. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 1985, 13, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargo, J.D.; Przylecki, W.; Andrews, B.T. Surgical Decision-Making in Microvascular Reconstruction of Composite Scalp and Skull Defects. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, 1895–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velnar, T.; Bosnjak, R.; Gradisnik, L. Clinical Applications of Poly-Methyl-Methacrylate in Neurosurgery: The In Vivo Cranial Bone Reconstruction. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vince, G.H.; Kraschl, J.; Rauter, H.; Stein, M.; Grossauer, S.; Uhl, E. Comparison between autologous bone grafts and acrylic (PMMA) implants—A retrospective analysis of 286 cranioplasty procedures. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2019, 61, 205–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlok, A.J.; Naidoo, S.; Kamat, A.S.; Lamprecht, D. Evaluation of locally manufactured patient-specific custom made implants for cranial defects using a silicone mould. S. Afr. J. Surg. 2018, 56, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.C.; Wei, L.; Xu, J.; Liu, J.F.; Gui, L. Clinical outcome of cranioplasty with high-density porous polyethylene. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2012, 23, 1404–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wesp, D.; Krenzlin, H.; Jankovic, D.; Ottenhausen, M.; Jägersberg, M.; Ringel, F.; Keric, N. Analysis of PMMA versus CaP titanium-enhanced implants for cranioplasty after decompressive craniectomy: A retrospective observational cohort study. Neurosurg. Rev. 2022, 45, 3647–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.R.; Fan, K.F.; Bentley, R.P. Custom-made titanium cranioplasty: Early and late complications of 151 cranioplasties and review of the literature. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 44, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Zhang, Q.; Mai, Y.; Yang, H.; Li, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhang, R. Outcome and risk factors of complications after cranioplasty with polyetheretherketone and titanium mesh: A single-center retrospective study. Front. Neurol. 2022, 13, 926436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Long, J.; Yang, X.; Lei, S.; Xiao, M.; Fan, P.; Qi, M.; Tan, W. Customized Titanium Mesh for Repairing Cranial Defects: A Method with Comprehensive Evaluation. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2015, 26, e758–e761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; Yuan, Y.; Li, X.; Sun, T.; Zhou, Y.; Yu, H.; Guan, J. A Large Multicenter Retrospective Research on Embedded Cranioplasty and Covered Cranioplasty. World Neurosurg. 2018, 112, e645–e651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoli, M.; Di Gino, M.; Cuoci, A.; Palandri, G.; Acciarri, N.; Mazzatenta, D. Handmade Cranioplasty: An Obsolete Procedure or a Surgery That Is Still Useful? J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, 966–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Las, D.E.; Verwilghen, D.; Mommaerts, M.Y. A systematic review of cranioplasty material toxicity in human subjects. J. Cranio-Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 49, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchac, D.; Greensmith, A. Long-term experience with methylmethacrylate cranioplasty in craniofacial surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2008, 61, 744–752; discussion 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csókay, G.; Würsching, T.; Szentpéteri, S.; Nolden, E.L.; Vaszilkó, M.; Bogdán, S. The use of patientspecific implants in maxillofacial reconstruction. Orv. Hetil. 2024, 165, 1594–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malcolm, J.G.; Rindler, R.S.; Chu, J.K.; Grossberg, J.A.; Pradilla, G.; Ahmad, F.U. Complications following cranioplasty and relationship to timing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Neurosci. 2016, 33, 39–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, S.; Khalifian, S.; Flores, J.M.; Bellamy, J.; Manson, P.N.; Rodriguez, E.D.; Dorafshar, A.H. Clinical outcomes in cranioplasty: Risk factors and choice of reconstructive material. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014, 133, 864–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, K.; Kim, J.S.; Kim, J.H.; Somani, S.; Di’Capua, J.; Dowdell, J.E.; Cho, S.K. Anesthesia Duration as an Independent Risk Factor for Early Postoperative Complications in Adults Undergoing Elective ACDF. Global Spine J. 2017, 7, 727–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegyi, P.; Petersen, O.H.; Holgate, S.; Erőss, B.; Garami, A.; Szakács, Z.; Dobszai, D.; Balaskó, M.; Kemény, L.; Peng, S.; et al. Academia Europaea Position Paper on Translational Medicine: The Cycle Model for Translating Scientific Results into Community Benefits. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegyi, P.; Erőss, B.; Izbéki, F.; Párniczky, A.; Szentesi, A. Accelerating the translational medicine cycle: The Academia Europaea pilot. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1317–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).