Abstract

Narcolepsy Type 1 (NT1) is a rare chronic neurological disorder characterized by core clinical manifestations such as excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), cataplexy, sleep paralysis (SP), hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations (HHs), and disrupted nocturnal sleep (DNS). Patients often experience comorbidities, including cognitive impairment, psychiatric disorders, and metabolic syndrome, necessitating lifelong management. Current therapeutic approaches primarily involve pharmacologic treatments for symptomatic relief, supplemented by non-pharmacologic interventions aimed at alleviating EDS and cataplexy. However, existing therapies are limited in efficacy and do not offer a cure. In recent years, a deeper understanding of the central role played by the orexin (hypocretin) system in the pathogenesis of NT1 has led to breakthrough advances in mechanism-based therapies targeting this pathway. Notably, selective orexin-2 receptor (OX2R) agonists such as TAK-861 have shown remarkable efficacy in Phase II/III clinical trials, holding the potential to fundamentally reshape the NT1 treatment landscape. This review systematically outlines current treatment options for NT1, with a focus on management strategies for atypical symptoms and special populations. It also highlights emerging therapeutic directions—including orexin-targeted agents, immunotherapies, and orexin cell/gene treatments—along with their future development.

1. Introduction

Narcolepsy is a disabling chronic neurological disorder with a prevalence of approximately 1 in 2000 []. According to the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 3rd Edition (ICSD-3), the disorder is primarily classified into Type 1 (NT1) and Type 2 (NT2). NT1 is characterized by cataplexy and significantly reduced orexin levels in cerebrospinal fluid (<110 pg/mL) []. Its pathogenesis is closely associated with genetic susceptibility (e.g., HLA-DQB1*06:02 allele), autoimmune mechanisms (e.g., orexin-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cell-mediated neuronal damage), and environmental triggers (e.g., H1N1 influenza infection or vaccination) []. The core pathological alteration involves defects in the hypothalamic orexin system, characterized by the specific loss or epigenetic silencing of orexin-producing neurons []. Patients typically exhibit low cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) orexin (Hcrt-1) levels, leading to disruption of the sleep–wake regulatory circuitry [].

The classic “pentad” of NT1 symptoms includes excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), cataplexy, disrupted nocturnal sleep (DNS), sleep paralysis (SP), and hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations (HH) []. However, its clinical manifestations extend far beyond this scope, often accompanied by significant cognitive impairment, psychiatric symptoms (such as depression and anxiety), and autonomic dysfunction. It frequently coexists with comorbidities such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, and sleep apnea, severely impacting patients’ quality of life and social functioning []. Current treatment strategies for NT1 primarily focus on symptom control, improving daytime functioning, and preventing complications. Although existing medications (such as wakefulness-promoting agents, sodium oxybate, antidepressants, etc.) relieve symptoms, they cannot reverse the disease progression. They also present challenges, including side effects, insufficient efficacy, and significant interindividual variability. Therefore, exploring novel therapies based on disease mechanisms is crucial.

This review outlines individualized management for narcolepsy type 1 (NT1), including pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies, and critically evaluates emerging therapies such as orexin-targeted drugs, immunotherapies, and cell/gene-based treatments. Through integration of current evidence and recent advances, it aims to guide clinical practice and inform the development of next-generation NT1 therapies.

2. Current Treatment

NT1 exhibits high heterogeneity in severity []. While primarily characterized by excessive daytime sleepiness and cataplexy, it is frequently accompanied by multiple comorbidities [,]. Management should be individualized, integrating pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies tailored to individual profiles. Initial monotherapy with agents targeting multiple symptoms is recommended. Special attention is warranted for specific populations (e.g., children, women of childbearing potential, the elderly). Close follow-up with regimen adjustments based on efficacy and feedback is essential.

2.1. Pharmacological Treatment

Pharmacological treatment is the cornerstone for managing the core symptoms of narcolepsy type 1 (NT1). Internationally recognized guidelines—specifically those from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) [] and the European guidelines on narcolepsy management []—offer evidence-based recommendations for both adult and pediatric populations, though they differ in certain details and scope. Current pharmacological treatments based on these two guidelines are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, while the pharmacology of narcolepsy treatments is outlined in Table 3 and Table 4.

Table 1.

Summary of Guideline Recommendations for Pharmacological Treatment of Narcolepsy in Adults.

Table 2.

Summary of Guideline Recommendations for Pharmacological Treatment of Narcolepsy in Children.

Table 3.

Pharmacology of Pharmacological Treatments for Narcolepsy in Adults.

Table 4.

Pharmacology of Pharmacological Treatments for Narcolepsy in Children.

2.1.1. EDS Pharmacological Treatment

Modafinil

Modafinil, a non-amphetamine stimulant, acts by (1) inhibiting dopamine transporters (DAT) to increase dopamine; (2) activating norepinephrine α1B receptors to promote norepinephrine release; (3) increasing glutamate and decreasing GABA, enhancing excitatory neurotransmission; and (4) reducing oxidative stress via glutathione elevation []. RCTs show modafinil reduces ESS scores by 4–6 points (p < 0.001), prolongs MWT sleep latency by 3–5 min (p < 0.001), and improves fatigue (30–40% reduction), mood (20–25% reduction), and cognitive function (15–20% improvement) [,]. A 12-month study demonstrated sustained EDS improvement in 80–85% of patients with no significant tolerance []. It has no major effects on adult sleep, but in children, it may prolong sleep onset latency (SOL) (p = 0.014), requiring morning dosing []. Adult dose: start at 100 mg/day, increase to 200–400 mg/day if needed. Pediatric: 50–400 mg/day (2–8 mg/kg) once daily []. Common side effects: headache, insomnia, and nausea, usually resolving in 1–2 weeks. Serious rare effects: psychiatric symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, <1%), Stevens-Johnson syndrome [,,]. Pregnancy: EMA/ANSM alert for potential congenital malformation risk early in pregnancy, but studies conflict; risk unconfirmed. Recommend discontinuing use in early pregnancy [,,].

Pitolisant

Pitolisant, a selective H3-receptor competitive antagonist/inverse agonist, acts via blocking autoreceptors to enhance histamine release, moderately modulating dopamine/norepinephrine systems, and inhibiting GABAergic neuronal activity []. In the Harmony-CTP trial, the 36 mg/day dose significantly reduced ESS scores by 5–7 points (p < 0.001), prolonged MWT by 4–6 min (p < 0.001), and decreased weekly cataplexy episodes by 75% (p < 0.001) []. Real-world studies demonstrated sustained efficacy, with ESS scores declining from 15.3 to 10.5, alongside improved quality of life (EQ-5D-5L VAS +12.3) and reduced depressive symptoms (BDI from 7.5 to 4.7) [,]. Pediatric trials (≥6 years) showed a 6.3-point reduction in UNS total score (p = 0.007), decreased ESS from 19 to 13.5 (p < 0.001), and reduced cataplexy frequency [,]. Pharmacokinetics: ~90% oral absorption, ~20-h half-life, CYP2D6-metabolized, no dose adjustment for hepatic/renal impairment []. Dosing: adults start at 9 mg/day, increasing to 18–36 mg/day after 2 weeks; children start at 4.5 mg/day, increasing to 9–36 mg/day []. Common adverse events include headache, insomnia, nausea, and anxiety, mostly mild and transient. Serious adverse events were rare (0.5%), with long-term safety confirmed []. Minimal cardiovascular impact makes it suitable for elderly patients. A drug-holiday regimen reduced modafinil dosage by 41% (p < 0.0001) while improving side effects [,].

Solriamfetol

Solriamfetol is a wake-promoting agent that inhibits dopamine and norepinephrine transporters (DAT/NET) []. It is indicated for excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) in narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), especially in narcolepsy type 1 with comorbid OSA. The drug is rapidly absorbed (Tmax ~2 h) and has a half-life of ~7.1 h, with ~90% excreted unchanged in urine. Dose adjustment is required for renal impairment: reduce by half for eGFR 30–59 mL/min/1.73 m2 and avoid if eGFR < 15 [].

Randomized controlled trials have shown improvements in EDS. In a 12-week Phase III trial, solriamfetol (150 mg and 300 mg) increased MWT duration and reduced ESS scores, irrespective of cataplexy status []. Another Phase III trial reported mean MWT increases of 9.8 and 12.3 min (vs. 2.1 for placebo), and ESS reductions of 5.4 and 6.4 points (vs. 1.6 for placebo) for the 150 mg and 300 mg doses, respectively []. A meta-analysis of six RCTs showed a mean MWT increase of 9.93 min and ESS reduction of 4.44 points, alongside higher improvement rates on Patient and Clinician Global Impression of Change scales (PGI-C/CGI-C) []. Network meta-analyses have reported that solriamfetol was ranked as superior to pitolisant, sodium oxybate, and modafinil/armodafinil in improving ESS and MWT [,]. Real-world data (SURWEY) supported these findings, with ESS scores decreasing from 17.6 to 13.6 (mean reduction: 4.3 points) [].

Safety profiles are generally favorable. Common adverse events include headache, nausea, and decreased appetite, with incidence rates similar to placebo in clinical trials []. Solriamfetol has low abuse potential (<1% drug craving) and no withdrawal rebound []. Mild increases in blood pressure (~2–3 mmHg systolic) and heart rate (~2–3 bpm) may occur but usually require no intervention []. Efficacy and safety are unaffected by depression history []. During long-term treatment (52 weeks), 25.7% of patients experienced ≥5% weight loss, showing a dose-dependent pattern []

Sodium Oxybate (SXB) and Its Derivatives

Sodium Oxybate (SXB, brand name Xyrem®), the sodium salt of gamma-hydroxybutyric acid (GHB), is the only agent that simultaneously improves EDS, cataplexy, and disrupted nighttime sleep (DNS) in narcolepsy. It modulates neurotransmission by binding to GHB receptors and activating GABAB receptors, improving sleep architecture by increasing slow-wave sleep and reducing nocturnal awakenings []. It exhibits rapid absorption and a short half-life, necessitating twice-nightly dosing on an empty stomach []. The adult starting dose is 4.5 g/night, titratable to a maximum of 9 g/night [,].

Clinical trials confirm SXB’s efficacy. It reduces weekly cataplexy attacks in a dose-dependent manner [] and significantly improves EDS, with additive effects when combined with modafinil []. SXB also enhances sleep continuity and quality [,]. A systematic review of 9 RCTs confirmed its benefits for EDS, cataplexy, and sleep structure []. Common adverse reactions are nausea, dizziness, and headache [], though psychiatric symptoms have been reported [,]. Long-term use is associated with weight loss and a significant sodium load (1100–1640 mg/night), equating to 2.8–4.2 g of salt intake nightly, posing potential cardiovascular risks [,]. A network meta-analysis indicated that LXB had the most favorable tolerability profile among anti-EDS drugs [].

Low-Sodium Oxybate (LXB, brand name Xywav®)

LXB is a mixture of oxybate salts with 92% less sodium than SXB. It is indicated for patients requiring sodium restriction []. Phase 3 trials demonstrate non-inferior efficacy to SXB in reducing EDS and cataplexy, with a reduced risk of cardiovascular adverse events []. Long-term use is associated with weight loss and improved quality of life [].

Once-Nightly Sodium Oxybate (ON-SXB, brand name Lumyrz®)

ON-SXB is an extended-release formulation allowing single bedtime dosing, improving adherence compared to SXB []. The Phase 3 REST-ON trial confirmed its efficacy in improving EDS, sleep quality, and cataplexy within weeks of treatment []. Its safety profile is similar to SXB, with no new signals identified [].

Clinical Caution Box

Sodium Burden of Oxybate Formulations: The high sodium burden associated with SXB (sodium oxybate) may induce hypertension, thereby increasing cardiovascular risk. However, a formal cardiovascular risk model quantifying the long-term benefits of LXB (low-sodium oxybate) over SXB is currently lacking. Thus, conducting relevant pharmacoepidemiological research to fill this evidence gap is crucial.

Other Wake-Promoting Agents

Armodafinil: The active R-enantiomer of modafinil features a longer half-life (12–15 h) for once-daily use. It shows efficacy comparable to modafinil for EDS, but with a lower incidence of insomnia (10% vs. 15%) []. Long-term use may cause mild blood pressure increases and tachycardia, necessitating regular monitoring [].

Methylphenidate: A potent dopamine reuptake inhibitor with significant stimulant effects and high abuse potential. It improves EDS at doses of 10–60 mg/day but is ineffective for cataplexy, making it a choice for refractory cases only []. Common adverse effects include tachycardia, hypertension, and insomnia, with a 5–10% risk of abuse/dependence [].

Amphetamines: These agents exert the strongest wake-promoting effects by enhancing dopamine/norepinephrine release and reuptake inhibition. While effective for refractory EDS, they are ineffective for cataplexy and carry the highest risks of serious adverse effects—including arrhythmias, psychosis, and dependence—and are contraindicated in cardiovascular disease [,].

2.1.2. Cataplexy Pharmacological Treatment

Anti-cataplexy drugs act primarily by modulating serotonin and norepinephrine to prevent emotion-induced loss of muscle tone. First-line treatments include sodium oxybate (SXB) and pitolisant.

First-Line Treatment

SXB activates GABAB receptors, inhibiting brainstem motor inhibitory pathways and stabilizing REM sleep to reduce cataplexy []. Its benefits include dose-dependent efficacy and absence of withdrawal rebound upon discontinuation []. Pitolisant promotes histamine release, enhancing brainstem arousal and moderately modulating dopamine, thereby reducing cataplexy frequency []. Advantages are convenient once-daily dosing and no negative cognitive effects, making it suitable for individuals requiring sustained mental performance [].

Second-Line Treatment (Antidepressants)

Antidepressants, including venlafaxine, clomipramine, fluoxetine, and citalopram, inhibit serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake to increase sympathetic tone. They are reserved for patients unresponsive to first-line agents. European guidelines offer a weak recommendation, while AASM guidelines do not endorse them due to limited evidence. A key advantage is their concurrent benefit for comorbid depression/anxiety.

Venlafaxine (an SNRI) at 37.5–225 mg/day in adults reduces cataplexy by 50–60% []. Common adverse effects are hypertension, headache, and dry mouth. Abrupt withdrawal may trigger cataplectic status, necessitating gradual tapering []. Clomipramine (a TCA), at 10–75 mg/day, is highly effective (60–70% reduction) but limited by anticholinergic effects like dry mouth, tachycardia, and risk of hypotension [,,]. SSRIs (e.g., fluoxetine, citalopram) exhibit weaker efficacy (30–40% reduction) and are reserved for mild-to-moderate cases; side effects include agitation, nausea, and sexual dysfunction [].

Exacerbation of Cataplexy Following Withdrawal of Antidepressants

Discontinuation of antidepressants can provoke cataplexy rebound. A 2009 study showed a significant increase in weekly attacks after stopping TCAs (median 55.7) or SSRIs (median 35.7) versus controls (15.25), which normalized after 4 weeks []. Gradual tapering is essential to mitigate this risk.

2.2. Nonpharmacological Treatment

Patients with narcolepsy often experience significant psychosocial impairment and reduced quality of life, including diminished work productivity, sexual dysfunction, higher traffic accident risks, and increased neuropsychiatric comorbidities like depression and anxiety [,,]. Pharmacological treatment alone is frequently inadequate. Non-pharmacological therapies, which are safe and sustainable, enhance drug efficacy, reduce dosage, and improve long-term prognosis. European guidelines strongly recommend these interventions as cornerstone treatments for NT1 [], such as cognitive behavioral therapy, psychological support, sleep hygiene, and lifestyle management [].

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a core non-pharmacological intervention increasingly used in narcolepsy []. Its goals include: (1) Cognitive restructuring to modify dysfunctional beliefs and stigma; (2) Behavioral adjustment to improve adherence, sleep hygiene, and scheduled napping; (3) Emotion and stress management, using techniques like systematic desensitization for cataplexy []. A tailored CBT for hypersomnia (CBT-H) demonstrated significant ESS score reductions and 15–20% improvements in SF-36 physical and social functioning among 35 patients [].

Specific behavioral strategies include:

Scheduled napping: Planning 2–3 short naps per day, each lasting 15–20 min, can help reduce sleep inertia and improve daytime alertness. The duration should be adjusted based on individual differences [,].

Extending nocturnal sleep duration: When total sleep time increases from 417.0 min to approximately 505.2 min, the daytime sleep latency of patients with narcolepsy significantly increased (p < 0.01) and the number of naps with a sleep latency of less than 10 min decreased (p < 0.02), and subjective sleepiness scores decreased (p < 0.02), indicating that extending night-time sleep can help patients with narcolepsy to reduce EDS [].

Physical activity: Regular exercise can stabilize circadian rhythms and improve sleep quality. Studies have shown that physical activity is associated with lower subjective sleepiness scores and reduced daytime napping in children with narcolepsy [].

Environmental and behavioral modulation: Strategies such as controlling ambient temperature [], avoiding monotonous activities, increasing social interaction, and employing self-stimulating behaviors (e.g., pinching the skin, chewing gum) can temporarily enhance alertness.

Dietary modifications: The low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet (LCKD) is currently the most evidence-supported approach. One study reported an 18% reduction in the total Narcolepsy Symptom Status Questionnaire (NSSQ) score (161.9 vs. 133.5, p = 0.0019), with subscale scores decreasing by 22% for sleepiness, 13% for sleep attacks, and 24% for sleep paralysis. Urinary ketone levels peaked at two weeks (3.7 ± 0.9), correlating with symptom improvement, suggesting a potential role of ketone metabolism in the therapeutic mechanism []

For cataplexy, CBT utilizes systematic desensitization through gradual exposure to emotional triggers (e.g., laughter) alongside relaxation training to mitigate symptom responses. Additional strategies include emotional avoidance and stimulus satiation [,]. Psychological counseling aids patients and families in comprehending disease impact, formulating individualized coping methods, and improving treatment adherence. Peer support alleviates isolation, bolsters coping confidence, and offers practical guidance []. Social adjustments—such as extended test time and flexible work schedules—along with peer groups and patient organizations, enhance life quality.

Tailored interventions are essential: pediatric care involves school support with scheduled naps and prolonged test durations, with 83% of parents noting academic improvement []. Reproductive-aged women benefit from non-pharmacological approaches coordinating sleep with contraception or pregnancy []. Older adults, often with comorbidities, require low-risk measures like consistent sleep–wake routines and sleep education, while avoiding prolonged daytime naps [,]. Although resources are limited, online platforms present new opportunities for patient connectivity.

In summary, non-pharmacological treatments, especially CBT and behavioral strategies, significantly improve psychosocial function and daytime symptoms in narcolepsy (Table 5).

Table 5.

Non-pharmacological Treatment Interventions for Narcolepsy and Their Target Effects.

2.3. Special Populations

Pediatric Patients: Pharmacological treatment in children requires careful consideration of growth, development, and potential long-term effects. Safety signals of particular concern include insomnia and delayed sleep onset (especially with modafinil), cardiovascular effects such as tachycardia and hypertension (with stimulants), and anticholinergic side effects (with tricyclic antidepressants). Dose adjustments are primarily based on body weight (e.g., modafinil, SXB). Data on the QTc interval effects and orthostatic hypotension for many drugs in this population are insufficient. There is a pressing need for more stratified studies focusing on the long-term safety and efficacy of narcolepsy treatments in children [,].

Geriatric Patients: Older adults with narcolepsy often present with multiple comorbidities and polypharmacy, increasing the risk of drug interactions and adverse events. Key considerations include the anticholinergic load (from TCAs), which can exacerbate cognitive impairment or cause urinary retention; orthostatic hypotension (from TCAs, venlafaxine); and QTc prolongation risk (associated with several antidepressants and pitolisant). Sodium oxybate use requires caution due to its CNS depressant effects and high sodium load in patients with heart failure or hypertension. Dose initiation should follow a “start low and go slow” principle. However, robust clinical trial data for most narcolepsy medications in the elderly are lacking, representing a significant evidence gap [,].

3. Emerging Treatments

3.1. Orexin System Targeted Therapy

It is well established that type 1 narcolepsy involves defects in the hypothalamic orexin system, characterized by specific loss or epigenetic silencing of orexin-producing neurons in the lateral hypothalamus, resulting in markedly reduced or absent cerebrospinal fluid orexin. Orexin, a key wake-promoting neuropeptide, acts on two G protein-coupled receptors (OX1R and OX2R) and projects widely to multiple arousal-regulatory brain regions, thereby maintaining and stabilizing wakefulness. In narcolepsy type 1, loss of orexin signaling leads to two core symptoms: excessive daytime sleepiness due to inadequate arousal drive and REM sleep dysregulation, where elements such as muscle atonia intrude into wakefulness, causing cataplexy, sleep paralysis, and hypnagogic hallucinations. Thus, compensating for deficient orexin signaling represents a fundamental therapeutic approach, primarily through either orexin replacement or receptor agonism. Given orexin peptides have poor blood-brain barrier permeability and short half-lives, receptor agonists—particularly selective OX2R agonists, which are crucial for promoting wakefulness—offer greater clinical potential. By precisely activating the arousal pathway, OX2R agonists may fundamentally alleviate core narcolepsy symptoms, shifting treatment from symptomatic to pathophysiology-targeted therapy.

3.1.1. Orexin Receptor Agonists

Research has focused on small-molecule receptor agonists. Among these, OX2R selective agonists have emerged as a research hotspot due to their advantages in improving core symptoms and safety profiles. Relevant preclinical and clinical trials have confirmed their therapeutic potential.

Preclinical Studies of OX2R Selective Agonists

Early preclinical studies established the therapeutic potential of OX2R-selective agonists. In 2017, Yoko Irukayama-Tomobe et al. demonstrated that the novel non-peptide agonist YNT-185 exerts pharmacological activity in transfection, brain slice, and mouse models, supporting a mechanistic treatment for narcolepsy-cataplexy []. A 2022 study in orexin knockout mice showed that the selective OX2R agonist [Ala11, D-Leu15]-orexin-B (AL-OXB) and non-selective orexin-A both alleviated core symptoms, with AL-OXB exhibiting a superior safety profile, confirming OX2R agonism is sufficient for efficacy []. Further studies on danavorexton (TAK-925) revealed rapid binding kinetics (dissociation t1/2 0.87 ± 0.10 min) and an activation profile similar to native orexin. In narcolepsy mouse models, it promoted wakefulness, reduced sleep fragmentation, and induced no significant receptor desensitization []. TAK-925 and ARN-776, despite low brain penetration, dose-dependently delayed NREM sleep onset, reduced cataplexy, and increased gamma power in EEG [].

In 2023, the orally available OX2R agonist TAK-994 activated human OX2R (EC50 19 nM) with >700-fold selectivity and improved sleep fragmentation and cataplexy in mouse models, showing stable efficacy after chronic dosing []. The 2024 discovery of TAK-861 (oveporexton) marked a breakthrough: it activated OX2R with an EC50 of 2.5 nM and ∼3000-fold selectivity over OX1R. It promoted wakefulness in mice and monkeys with ∼10-fold higher potency than TAK-994 and significantly improved symptoms in narcolepsy models without inducing tolerance []. Additionally, phenylglycine-based OX2R agonists 57 and 58, identified via high-throughput screening, showed nanomolar potency (EC50 = 2.5 and 0.4 nM, respectively) and favorable brain penetration after optimization [].

Clinical Trials of OX2R Selective Agonists

Multiple clinical trials have validated the efficacy of OX2R selective agonists in human patients while providing direction for drug optimization.

TAK-925: Two 2022 clinical studies of danavorexton (TAK-925-1001 single-dose escalation, TAK-925-1003 multiple-dose escalation) demonstrated that intravenous infusion of this drug produced a dose-dependent prolongation of the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) sleep latency in NT1 patients (with a maximum effect of up to 40 min), significantly improved EDS and cataplexy. NT2 patients also showed EDS improvement, with overall good tolerability and no serious adverse events [].

TAK-994: In 2023, the phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled trial and extension study of TAK-994 enrolled 73 patients. Results showed that all dose groups (30mg, 90mg, 180mg twice daily) demonstrated significant improvements in: Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) scores (difference from placebo: −10.1 to −13.0 points), and weekly cataplexy attack rates (incidence ratio 0.05–0.20). However, the trial was terminated early due to 5 cases of significant liver enzyme elevation and 3 cases meeting Hy’s law criteria for drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Subsequent mechanistic studies revealed the liver injury was covalent binding-dependent idiosyncratic DILI, not directly linked to OX2R, providing a target for future drug optimization [,].

TAK-861: A Phase 2 trial published in 2025 enrolled 112 patients (90 receiving different doses of TAK-861 and 22 receiving a placebo). After 8 weeks of treatment, all dose groups demonstrated a mean increase in MWT sleep latency of 13.7–26.6 min compared to placebo (adjusted p ≤ 0.001) and a reduction in ESS total scores of 6.4–11.3 points compared to placebo (adjusted p < 0.005). The weekly cataplexy rate was significantly lower in the 2 mg twice daily and 2 mg followed by 5 mg daily groups compared to placebo (adjusted p < 0.05), with no hepatotoxicity observed. 97% of patients completed the trial []. Recently, data from two Phase III clinical trials of TAK-861 (The First Light and The Radiant Light) presented at the 2025 World Sleep Congress further confirmed its efficacy. Regarding improvement in daytime sleepiness: In the First Light study, 83% (53/64) of patients in the 2 mg/2 mg dose group achieved an ESS score ≤ 10 at Week 12, compared to only 17% (2/12) in the placebo group. In The Radiant Light study, these proportions were 84% (56/67) and 12% (4/33), respectively. For enhancing daytime alertness, the proportion of patients in the 2mg/2mg dose group with MWT sleep latency ≥ 20 min was 54% (36/67) in The First Light study, compared to 9% (2/22) in the placebo group. In the Radiant Light study, this proportion reached 80% (46/57) compared to 0% in the placebo group. Regarding reduction in cataplexy episodes, the median number of cataplexy-free days at baseline was 0 days for all patients; In the First Light study, the median number of days without cataplexy at Week 12 increased to approximately 4 days in the 1 mg/1 mg and 2 mg/2 mg dose groups, compared to 0.5 days in the placebo group, with weekly cataplexy rate (WCR) reductions of 66% and 79% from baseline, respectively. In the Radiant Light study, the 2 mg/2 mg dose group showed a median drop in cataplexy days to 5 days, with a 79.0% reduction in WCR [,].

Furthermore, OX2R agonists show potential in mood regulation. Lihua Chen et al. reported that repeated intraperitoneal injections of the OX2R agonist YNT-185 reduced both baseline and morphine withdrawal-induced anxiety-like behaviors in male mice, suggesting OX2R as a potential therapeutic target for anxiety disorders [].

Other investigational drugs such as ALKS 2680 and ORX750 are currently in various clinical development stages, demonstrating active progress in this field. Table 6 lists all OX2R agonists currently in clinical trials.

Table 6.

List of clinical trials of OX2R Agonist for narcolepsy treatment.

3.1.2. Orexin Replacement Therapy

Orexin replacement therapy compensates for endogenous deficiency by exogenously supplementing orexin peptides. Both animal experiments and human studies demonstrate its efficacy in improving certain symptoms. However, its core limitations lie in the difficulty of crossing the blood-brain barrier and its poor therapeutic effect on EDS.

Efficacy and Dosage Exploration in Animal Studies

A 2000 study showed that systemic administration of orexin-A (3 μg/kg) increased activity, prolonged wakefulness, decreased REM sleep without altering non-REM sleep, reduced sleep fragmentation, and produced a dose-dependent reduction in cataplexy in canine narcoleptics. Repeated daily dosing consolidated wake and sleep periods and abolished cataplexy for over three days post-treatment []. However, subsequent work revealed that orexin-A replacement was ineffective in dogs with Hcrtr2 mutations. Only very high intravenous doses (96–384 µg/kg) transiently reduced cataplexy, underscoring the blood-brain barrier (BBB) limitation []. Later advances explored alternative delivery routes. In 2007, both intravenous (2.5–10.0 μg/kg) and intranasal (1.0 μg/kg) Orexin-A improved cognitive performance in sleep-deprived monkeys, with intranasal administration being more effective than the highest IV dose []. A 2008 rat study confirmed that intranasal delivery yielded much lower plasma levels but approximately 80% of the brain concentration—Area under the time curve (AUC) resulted from direct nasal-to-brain transport, confirming intranasal administration bypasses the blood-brain barrier and reduces systemic exposure []. A study found that continuous intrathecal delivery of Orexin-A (1 nmol/1 μL/h) ascends from the spinal cord to the brain, elevating intracerebral orexin levels to endogenous levels in wild-type mice. This significantly reduced cataplexy episodes and sleep-onset rapid eye movement (SOREM) episodes, with receptor-specific efficacy [].

The Findings and Limitations of Human Clinical Trials

A series of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) by Baier et al. identified therapeutic effects of intranasal Orexin A in narcolepsy with cataplexy patients. One study confirmed mild olfactory dysfunction as an inherent symptom linked to central orexin deficiency, reversible by intranasal Orexin A []. A pilot study of 8 patients showed that 435 nmol intranasal human recombinant Orexin-A before bedtime did not affect nocturnal arousals but reduced REM sleep duration (p = 0.02), total REM sleep duration (p = 0.039), and direct wakefulness-to-REM transitions []. Another trial demonstrated stabilized REM sleep and improved attention with intranasal Orexin A []. Current evidence indicates intranasal Orexin A reduces wakefulness-to-REM transitions and total REM duration, improves attention, but does not increase wakefulness or alleviate sleepiness [,,].

3.2. Immunotherapy

Although no direct evidence currently confirms that narcolepsy type 1 (NT1) is an autoimmune disease, increasing indirect evidence supports the autoimmune hypothesis:

- Genetic Susceptibility: Narcolepsy shows a strong association with HLA-DQB1*06:02 [], a molecule responsible for antigen presentation to CD4+ T cells. It is also associated with polymorphisms in immune-related genes such as TCR-α and P2RY11 [,].

- Environmental Triggers: 1. Streptococcal Infection: Individuals who developed streptococcal pharyngitis before age 21 exhibit increased NT1 risk, with higher serum streptococcal antibody levels within 3 years of onset compared to controls []; 2. H1N1 infection/vaccination: NT1 incidence tripled within 6 months following China’s H1N1 pandemic []; increased incidence among Pandemrix vaccine recipients [,], suggesting molecular mimicry between the H1N1 HA protein and hypocretin [].

- Immune cell involvement: 1. CD4+ T cells: Patients harbor hypocretin-specific CD4+ T cells capable of cross-recognizing H1N1 HA protein []; 2. CD8+ T cells: Increased autoreactive CD8+ T cells in patient blood [], and in animal models, CD8+ T cells can directly destroy orexin neurons []; CD8+ T cell clones in CSF correlate with progression from NT2 to NT1 [].

- Evidence of autoantibodies: 1. TRIB2 antibody: Positive in 14% of patients, but also positive in 5% of controls. Acts as an intracellular antigen with no direct pathogenic role []; 2. HCRTR2 antibody: Positive in 85% of post-vaccination NT1 cases (vs. 35% controls), absent in idiopathic NT1, lacking core pathogenic significance [].

Based on the autoimmune hypothesis, various immunotherapy regimens have been attempted for patients with narcolepsy, including corticosteroids, plasma exchange (PLEX), intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), and rituximab. However, most reports are case studies or short-term applications with inconsistent efficacy—for example, IVIG improves cataplexy only in some patients with recent-onset disease, while PLEX provides only temporary relief. Long-term effects remain unvalidated by randomized controlled trials. Recently, targeted therapies against B cells and T cells have also been explored in limited case studies. Table 7 summarizes various immunotherapies in NT1 [,,,,,,,,].

Table 7.

Summary of Immunotherapy in NT1.

3.3. Cell Therapy and Gene Therapy

As a long-term vision for fundamental treatment, these strategies aim to restore the function of the orexin system.

3.3.1. Cell Transplantation

The core pathogenesis of narcolepsy involves massive loss of hypothalamic orexin neurons, leading to significantly reduced cerebrospinal fluid orexin levels. Existing treatments only partially alleviate symptoms and cannot reverse neuronal loss. Successful transplantation of orexin neurons could potentially serve as a fundamental therapeutic approach. Transplantation experience in Parkinson’s disease demonstrates that fetal dopaminergic neurons can survive for over 10 years post-transplantation, integrate into host circuits, and restore function, providing feasibility evidence for orexin neuron transplantation [,]. Experimental evidence has shown that the suspension of orexin neurons extracted from the hypothalamus of 8–10-day-old rat pups, when transplanted into the pons of adult rats (the area where orexin fibers project, without their own neurons), can survive until 36 days after transplantation. The morphology of the surviving neurons is similar to that of mature orexin neurons in adult rats, but the number continuously decreases starting from day 3. This preliminary verification demonstrates the feasibility of orexin neuron cell transplantation [].

3.3.2. Gene Transfer

In recent years, orexin gene supplementation therapy has gained significant research interest. Several studies have successfully improved symptoms in narcoleptic mouse models by delivering the orexin gene to specific brain regions via viral vectors, laying the groundwork for clinical translation. Liu et al. first used a replication-defective HSV-1 amplicon vector to deliver the mouse prepro-orexin gene into the lateral hypothalamus (LH) of orexin knockout mice. Over a 4-day expression period, cataplexy decreased by ~60%, REM sleep duration in the latter half of the night normalized to wild-type levels, and orexin-A was detected in the CSF, confirming the efficacy of targeted gene transfer [].

The same group employed a recombinant AAV (rAAV) vector in orexin-ataxin-3 transgenic mice. They found that orexin delivery to the zona incerta (ZI) or LH significantly reduced cataplexy without altering total sleep–wake time, whereas striatal delivery or targeting MCH neurons was ineffective, underscoring regional specificity. Tracer studies indicated that ZI receives amygdala inputs and projects to the locus coeruleus, suggesting its role in stabilizing motor tone []. Blanco-Centurion et al. injected rAAV-orexin into the dorsolateral pons of orexin KO mice, reporting an 80.7% reduction in cataplexy and an increased proportion of long wake bouts at night (8% to 23%), indicating improved wake maintenance. Notably, control GFP injection worsened cataplexy, highlighting regional sensitivity [].

Kantor et al. targeted the mediobasal hypothalamus in Atx transgenic mice. Following AAV-orexin injection, wake time increased by 13% and wake bout duration lengthened by 48% during the dark phase, with improved diurnal patterns of wakefulness and REM sleep, though cataplexy was not significantly reduced, suggesting symptom-specific neural pathways []. Liu et al. further investigated the amygdala’s role by delivering rAAV-orexin into its central and basolateral nuclei in orexin KO mice. This not only reduced spontaneous cataplexy but also blocked odor-induced cataplexy and increased wakefulness during odor exposure, providing the first evidence that orexin gene transfer suppresses both spontaneous and emotion-triggered cataplexy [].

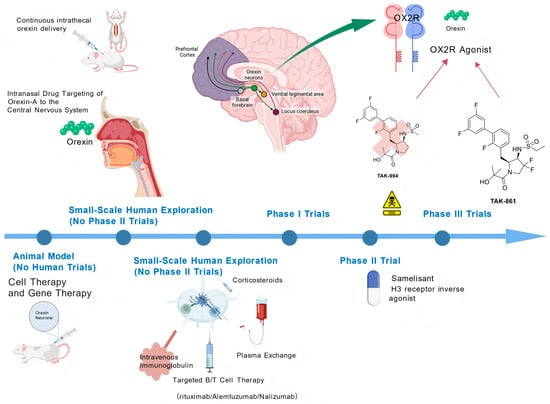

Figure 1 shows the merging Treatment for Narcolepsy Type 1.

Figure 1.

Emerging Treatment for Narcolepsy Type 1.

This illustration outlines key therapeutic strategies targeting the orexin (hypocretin) system—a core pathogenic pathway in narcolepsy Type 1 (NT1)—alongside other emerging treatments. Key elements include the following: Orexin Receptor Agonists: Selective orexin-2 receptor (OX2R) agonists (e.g., TAK-861, TAK-994) and other orexin agonists, which directly activate wake-promoting pathways via central nervous system (CNS) targets such as the prefrontal cortex, ventral tegmental area, and locus coeruleus. Orexin Replacement Therapy: Delivery approaches for orexin-A (e.g., intranasal, continuous intrathecal administration) to bypass the blood-brain barrier and compensate for endogenous orexin deficiency. Emerging Treatments: Immunotherapies (intravenous immunoglobulin, plasma exchange, targeted B/T cell therapies including rituximab, alemtuzumab, nalizumab), cell/gene therapies, corticosteroids, and histamine H3 receptor inverse agonists (e.g., samelisant). Clinical Development Phases: Classification of agents by developmental status (animal models, small-scale human exploration, Phase I/II/III trials) to highlight translational progress. This visualization synthesizes mechanism-based interventions and novel therapeutic directions reshaping NT1 management. Created with BioGDP.com

3.4. Other New Drugs

Samelisant (SUVN-G3031) is a novel, potent, selective histamine H3 receptor (H3R) inverse agonist currently under development for the treatment of narcolepsy. It exhibits favorable ADME properties, including high passive permeability, high plasma free fraction, and primarily renal excretion (accounting for ~78% of total human clearance). Its metabolism relies on CYP3A4 and MAO-A, posing minimal risk of drug interactions. Preclinical studies indicate it modulates neurotransmitter levels such as histamine and dopamine, prolongs wakefulness duration, and reduces cataplexy episodes. Phase 2 clinical trials confirmed significant improvement in excessive daytime sleepiness (with marked reduction in ESS scores), while common adverse reactions include insomnia and abnormal dreams. A sensitive LC-MS/MS quantitative method has been established for clinical detection, and related research is advancing it toward later clinical phases [].

4. Discussion

Currently, the clinical management of narcolepsy type 1 (NT1) primarily relies on symptomatic treatment. Although these drugs can prolong wakefulness to some extent, their ability to improve the quality remains limited. In recent years, selective OX2R agonists have emerged as a novel mechanism-driven therapeutic strategy for NT1. By activating downstream arousal pathways of OX2R, these agonists not only simultaneously improve EDS, cataplexy, and nocturnal sleep fragmentation, but also enhance overall wakefulness quality—including heightened attention and reduced anxiety. The representative drug TAK-861 was evaluated in Phase II clinical trials and was associated with restoration of arousal function to levels considered healthy in most patients. After 8 weeks of treatment, the proportion of patients achieving a mean sleep latency (MWT) ≥20 min across dose groups was as follows: 37% in the 0.5 mg bid group, 81% in the 2 mg bid group, 81% in the 2 mg → 5 mg qd group, and 61% in the 7 mg qd group [,]. To date, the OX2R agonist TAK-861 has shown no hepatotoxicity in trials, with adverse events primarily mild to moderate (e.g., controllable insomnia, urinary urgency, and frequency), suggesting strong potential for clinical application. However, current clinical studies of OX2R agonists lack head-to-head comparisons with comparable agents. Future long-term extension trials are needed to further validate its sustained efficacy and long-term safety. Given the history of TAK-994, rigorous liver safety monitoring remains critical throughout this drug class’s development and any future post-marketing phase. If approved, a Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy (REMS) program, including baseline and periodic liver enzyme tests, would be a prudent risk mitigation measure.

In studies of exogenous orexin replacement therapy, animal experiments demonstrate that orexin supplementation can reverse all core symptoms of narcolepsy type 1 (NT1). However, human studies reveal that while exogenous orexin-A improves sleep structure, olfactory function, and attention in NT1 patients, it fails to significantly alleviate excessive daytime sleepiness—the core clinical manifestation. This discrepancy suggests that orexin deficiency may not be the sole mechanism underlying NT1 pathogenesis. Other potential pathological mechanisms include autoimmune responses damaging orexin neurons while also impairing their receptors; dysregulation of related neural networks within the hypothalamus, such as concomitant histaminergic pathway dysfunction; or loss of neural pathway plasticity due to chronic orexin deficiency, rendering exogenous orexin ineffective at activating arousal-related circuits.

Future therapeutic strategies for narcolepsy type 1 (NT1) targeting the orexin system should prioritize the following directions. First, accelerating the clinical development of OX2R agonists, including head-to-head drug comparisons and evaluations of long-term efficacy, safety, and real-world effectiveness. Second, addressing key evidence gaps by clarifying the clinical benefits of exogenous orexin-A in alleviating non-core symptoms such as cataplexy and sleep paralysis. Third, systematically refining intervention protocols through comparative studies of orexin dosage, frequency, and administration routes (e.g., intranasal, intrathecal) to establish reliable dose-response relationships. Finally, developing multi-target combination therapies—such as pairing selective OX2R agonists with conventional arousal-promoting agents or combining exogenous orexin with receptor agonists—may address the complex pathophysiology of NT1 and offer novel solutions for refractory or severe cases. With ongoing clinical trials and continuous optimization, orexin-targeted therapies are poised to fundamentally reshape NT1 treatment.

Current immunotherapy approaches targeting NT1 primarily focus on B-cell-targeted interventions or broad-spectrum immunosuppression. However, recent immunological studies reveal that CD8+ T cells are the primary effector cells responsible for the selective destruction of orexinergic neurons. Consequently, future immunotherapy development should prioritize the creation of drugs targeting CD8+ T cells (such as alimertinib and natuzumab), with their efficacy validated through rigorous clinical trials. Regarding the optimal intervention timing, clinical observational data indicate that approximately 80% of orexin neurons have already undergone irreversible loss by the time cataplexy symptoms appear. This strongly suggests that effective mechanism-based treatments must be initiated prior to symptom onset. Specifically, the intervention window should be set after the emergence of excessive daytime sleepiness but before the occurrence of cataplexy. For example, in high-risk populations such as those positive for HLA-DQB1*06:02, dynamic monitoring of cerebrospinal fluid orexin levels and CD8+ T cell-related markers could serve as biological indicators for initiating early intervention. Regarding efficacy assessment systems, current approaches suffer from insufficient standardization. Existing assessment tools are heterogeneous, encompassing subjective scales (e.g., Epworth Sleepiness Scale, ESS) and objective measures (e.g., Multiple Sleep Latency Test, MSLT; CSF orexin testing). Furthermore, symptom presentation in pediatric patients differs significantly from adults, necessitating the development of age-specific standardized assessment tools (e.g., child-specific cataplexy diaries) to enhance accuracy and sensitivity. Notably, existing evidence on immunotherapy primarily stems from case reports or non-randomized controlled studies, whose results are susceptible to confounding factors like placebo effects and natural disease fluctuations (some patients may experience short-term spontaneous remission). Therefore, rigorously designed and executed high-quality randomized controlled trials are essential to confirm the true efficacy and safety of immunotherapy. Future research and clinical practice in NT1 immunotherapy should prioritize three key directions: developing CD8+ T cell-targeted therapeutics, optimizing early intervention strategies during prodromal phases, and establishing age-specific standardized efficacy assessment systems. Only through systematic advancement in these areas can the precise role and clinical value of immunotherapy within the overall NT1 management strategy be definitively established.

Cell and gene therapies represent a long-term vision for fundamentally restoring the function of the orexinergic system. Cell therapy involves transplanting stem cell-derived orexinergic neuronal precursors into the brain. Current challenges include (a) limited donor cell sources, still relying largely on postnatal animal hypothalamic tissue; (b) extremely low post-transplantation cell survival rates, reported to be only about 5%; and (c) insufficient evidence of functional integration with host circuits or symptomatic improvement. Future progress depends on generating fully functional orexin neuroblasts that exhibit (1) enhanced survival after transplantation; (2) physiologically regulated orexin release; (3) molecular, morphological, and electrophysiological properties resembling mature orexin neurons; (4) capacity to form functional orexin-releasing terminal networks; and (5) successful integration into host neural circuits to restore arousal regulation. Achieving these goals requires systematic preclinical research using robust animal models.

Gene therapy has demonstrated significant efficacy in multiple narcolepsy mouse models, with effects varying by targeted brain region. Key areas such as the ZI, LH, dorsolateral pons, and amygdala regulate cataplexy, wake maintenance, and circadian rhythms via distinct pathways. These findings support the preclinical foundation for precise gene therapy in human narcolepsy. However, as human narcolepsy is primarily acquired—unlike the genetic orexin-KO models used—validation in more clinically relevant models (e.g., autoimmune orexin neuron injury) is necessary. This field is still in the preclinical research stage and has some way to go before clinical application.

The evaluation of non-pharmacological interventions and overall treatment success in narcolepsy would benefit from standardizing patient-reported outcomes (PROs). Current PRO measures vary widely, limiting comparability. We recommend that future trials and observational studies adopt a core PRO set, minimally including the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ), EQ-5D-5L, and a validated depression scale (e.g., PHQ-9).

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, as a narrative rather than a systematic review, it may be subject to selection bias. Moreover, the quality of included studies—including randomized trials and real-world evidence—was not formally evaluated using standardized risk-of-bias tools (e.g., Cochrane RoB 2). Thus, our conclusions are conditional, and potential bias in the primary literature must be acknowledged. Second, direct head-to-head comparisons among many evaluated agents—particularly newer OX2R agonists versus established therapies—are lacking. To this end, we have summarized the design, potential biases, and methodological limitations of key randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and real-world studies evaluating major pharmacological interventions for NT1 in Table 8. Additionally, the underlying assumptions of cited network meta-analyses (e.g., transitivity and consistency) were not examined, and their findings should be interpreted cautiously. Third, robust long-term safety and efficacy data in special populations (e.g., pediatric and geriatric patients) remain scarce, warranting further study. Finally, the shift toward pathophysiology-targeted therapies like OX2R agonists and LXB raises health economic concerns. The potentially high cost of these novel agents, alongside limited pediatric access and reimbursement challenges, may exacerbate treatment inequities. Formal cost-effectiveness analyses comparing new and existing treatments are urgently needed to inform policy and ensure equitable access, especially for children and resource-limited settings.

Table 8.

Summary of Key RCTs and Real-World Studies on New Drugs for Narcolepsy: Design, Potential Biases, and Methodological Limitations.

5. Conclusions

Current NT1 management relies on pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies for symptom control. First-line EDS pharmacotherapy includes wake-promoting agents (e.g., modafinil, solriamfetol and pitolisant), while sodium oxybate and its derivatives are central to cataplexy management and also improve nocturnal sleep. Non-pharmacological interventions like scheduled napping and CBT provide essential adjunctive support.

The treatment paradigm is shifting towards mechanism-based therapies. The OX2R agonist TAK-861 shows exceptional promise, demonstrating robust efficacy in improving EDS and cataplexy in Phase III trials, with the potential to become a first-line therapy. While challenges remain for other emerging approaches like immunotherapy and orexin replacement, OX2R agonists represent a transformative advance. Future management will increasingly focus on personalized, pathophysiology-targeted treatments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.X., Y.C. and L.Z.; methodology, Q.X., Y.C. and L.Z.; investigation, Q.X., Y.C. and L.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.X., Y.C. and L.Z.; writing—review and editing, T.W. and Q.Z.; supervision, J.X.; formal analysis, J.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sateia, M.J. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: Highlights and modifications. Chest 2014, 146, 1387–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liblau, R.S.; Latorre, D.; Kornum, B.R.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Mignot, E.J. The immunopathogenesis of narcolepsy type 1. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2024, 24, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scammell, T.E. Narcolepsy. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 2654–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahoney, C.E.; Cogswell, A.; Koralnik, I.J.; Scammell, T.E. The neurobiological basis of narcolepsy. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2019, 20, 83–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morse, A.M.; Kim, S.Y.; Harris, S.; Gow, M. Narcolepsy: Beyond the Classic Pentad. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohayon, M.M.; Thorpy, M.J.; Carls, G.; Black, J.; Cisternas, M.; Pasta, D.J.; Bujanover, S.; Hyman, D.; Villa, K.F. The Nexus Narcolepsy Registry: Methodology, study population characteristics, and patterns and predictors of narcolepsy diagnosis. Sleep Med. 2021, 84, 405–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, I.; Thorpy, M. Clinical features, diagnosis and treatment of narcolepsy. Clin. Chest Med. 2010, 31, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Adamantidis, A.; Burdakov, D.; Han, F.; Gay, S.; Kallweit, U.; Khatami, R.; Koning, F.; Kornum, B.R.; Lammers, G.J.; et al. Narcolepsy—Clinical spectrum, aetiopathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2019, 15, 519–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maski, K.; Trotti, L.M.; Kotagal, S.; Robert Auger, R.; Rowley, J.A.; Hashmi, S.D.; Watson, N.F. Treatment of central disorders of hypersomnolence: An American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 1881–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, C.L.A.; Kallweit, U.; Vignatelli, L.; Plazzi, G.; Lecendreux, M.; Baldin, E.; Dolenc-Groselj, L.; Jennum, P.; Khatami, R.; Manconi, M.; et al. European guideline and expert statements on the management of narcolepsy in adults and children. J. Sleep Res. 2021, 30, e13387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamanian, M.Y.; Karimvandi, M.N.; Nikbakhtzadeh, M.; Zahedi, E.; Bokov, D.O.; Kujawska, M.; Heidari, M.; Rahmani, M.R. Effects of Modafinil (Provigil) on Memory and Learning in Experimental and Clinical Studies: From Molecular Mechanisms to Behaviour Molecular Mechanisms and Behavioural Effects. Curr. Mol. Pharmacol. 2023, 16, 507–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicki, D.; Bala, M.M.; Niewada, M.; Wierzbicka, A. Modafinil for narcolepsy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Med. Sci. Monit. 2010, 16, Ra177–Ra186. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, P.M.; Schwartz, J.R.; Feldman, N.T.; Hughes, R.J. Effect of modafinil on fatigue, mood, and health-related quality of life in patients with narcolepsy. Psychopharmacology 2004, 171, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldofsky, H.; Broughton, R.J.; Hill, J.D. A randomized trial of the long-term, continued efficacy and safety of modafinil in narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2000, 1, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W.C.; Huang, Y.S.; Trevor Lam, N.Y.; Mak, K.Y.; Tang, I.; Wang, C.H.; Lin, C. Effects of modafinil on nocturnal sleep patterns in patients with narcolepsy: A cohort study. Sleep Med. 2024, 119, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschini, C.; Pizza, F.; Cavalli, F.; Plazzi, G. A practical guide to the pharmacological and behavioral therapy of Narcolepsy. Neurotherapeutics 2021, 18, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckley, P.J.; Wolf, C.T. Psychosis in a 22-Year-Old Woman With Narcolepsy After Restarting Sodium Oxybate. Psychosomatics 2018, 59, 298–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasui-Furukori, N.; Kusunoki, M.; Kaneko, S. Hallucinations associated with modafinil treatment for narcolepsy. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2009, 29, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, V.; Philippidou, M.; Walsh, S.; Creamer, D. Stevens-Johnson syndrome induced by modafinil. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2018, 43, 191–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesta, C.E.; Engeland, A.; Karlsson, P.; Kieler, H.; Reutfors, J.; Furu, K. Incidence of Malformations After Early Pregnancy Exposure to Modafinil in Sweden and Norway. JAMA 2020, 324, 895–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S.; Braverman, D.L.; Frishman, I.; Bartov, N. Pregnancy and Fetal Outcomes Following Exposure to Modafinil and Armodafinil During Pregnancy. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yang, J. Pitolisant for treating patients with narcolepsy. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Arnulf, I.; Szakacs, Z.; Leu-Semenescu, S.; Lecomte, I.; Scart-Gres, C.; Lecomte, J.M.; Schwartz, J.C. Long-term use of pitolisant to treat patients with narcolepsy: Harmony III Study. Sleep 2019, 42, zsz174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Río-Villegas, R.; Martínez-Orozco, F.J.; Romero-Santo Tomás, O.; Yébenes-Cortés, M.; Gómez-Barrera, M.; Gaig-Ventura, C. Real-life WAKE study in narcolepsy patients with cataplexy treated with pitolisant and unresponsive to previous treatments. Rev. Neurol. 2022, 75, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plazzi, G.; Mayer, G.; Bodenschatz, R.; Bonanni, E.; Cicolin, A.; Della Marca, G.; Dolso, P.; Strambi, L.F.; Ferri, R.; Geisler, P.; et al. Interim analysis of a post-authorization safety study of pitolisant in treating narcolepsy: A real-world European study. Sleep Med. 2025, 129, 20–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Lecendreux, M.; Lammers, G.J.; Franco, P.; Poluektov, M.; Caussé, C.; Lecomte, I.; Lecomte, J.M.; Lehert, P.; Schwartz, J.C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of pitolisant in children aged 6 years or older with narcolepsy with or without cataplexy: A double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triller, A.; Pizza, F.; Lecendreux, M.; Lieberich, L.; Rezaei, R.; Pech de Laclause, A.; Vandi, S.; Plazzi, G.; Kallweit, U. Real-world treatment of pediatric narcolepsy with pitolisant: A retrospective, multicenter study. Sleep Med. 2023, 103, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, Y.; Lang, C.; Kallweit, U.; Apel, D.; Fleischer, V.; Ellwardt, E.; Groppa, S. Pitolisant-supported bridging during drug holidays to deal with tolerance to modafinil in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2023, 112, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subedi, R.; Singh, R.; Thakur, R.K.; C, B.K.; Jha, D.; Ray, B.K. Efficacy and safety of solriamfetol for excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy and obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Sleep Med. 2020, 75, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, M.C.; Carlson, S.; Pysick, H.; Berry, V.; Tondryk, A.; Swartz, H.; Cornett, E.M.; Kaye, A.M.; Viswanath, O.; Urits, I.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Solriamfetol to Treat Excessive Daytime Sleepiness. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 2024, 54, 65–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Shapiro, C.; Mayer, G.; Lammers, G.J.; Emsellem, H.; Plazzi, G.; Chen, D.; Carter, L.P.; Lee, L.; Black, J.; et al. Solriamfetol for the Treatment of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Participants with Narcolepsy with and without Cataplexy: Subgroup Analysis of Efficacy and Safety Data by Cataplexy Status in a Randomized Controlled Trial. CNS Drugs 2020, 34, 773–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorpy, M.J.; Shapiro, C.; Mayer, G.; Corser, B.C.; Emsellem, H.; Plazzi, G.; Chen, D.; Carter, L.P.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; et al. A randomized study of solriamfetol for excessive sleepiness in narcolepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2019, 85, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien, P.Y.; Kuo, C.Y.; Lin, M.H.; Chang, Y.J.; Hung, C.C. Pharmacological Interventions for Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Adults with Narcolepsy: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhan, S.; Ye, H.; Li, N.; Zhang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, Y.; Hu, S.; Hou, Y. Comparative Efficacy and Safety of Multiple Wake-Promoting Agents for the Treatment of Excessive Daytime Sleepiness in Narcolepsy: A Network Meta-Analysis. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2023, 15, 217–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhotra, A.; Shapiro, C.; Pepin, J.L.; Hedner, J.; Ahmed, M.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Strollo, P.J.; Mayer, G.; Sarmiento, K.; Baladi, M.; et al. Long-term study of the safety and maintenance of efficacy of solriamfetol (JZP-110) in the treatment of excessive sleepiness in participants with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 2020, 43, zsz220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystal, A.D.; Benca, R.M.; Rosenberg, R.; Schweitzer, P.K.; Malhotra, A.; Babson, K.; Lee, L.; Bujanover, S.; Strohl, K.P. Solriamfetol treatment of excessive daytime sleepiness in participants with narcolepsy or obstructive sleep apnea with a history of depression. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 155, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malhotra, A.; Strollo, P.J., Jr.; Pepin, J.L.; Schweitzer, P.; Lammers, G.J.; Hedner, J.; Redline, S.; Chen, D.; Chandler, P.; Bujanover, S.; et al. Effects of solriamfetol treatment on body weight in participants with obstructive sleep apnea or narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2022, 100, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.M.; Keating, G.M. Sodium oxybate: A review of its use in the management of narcolepsy. CNS Drugs 2007, 21, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazzi, G.; Ruoff, C.; Lecendreux, M.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Rosen, C.L.; Black, J.; Parvataneni, R.; Guinta, D.; Wang, Y.G.; Mignot, E. Treatment of paediatric narcolepsy with sodium oxybate: A double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised-withdrawal multicentre study and open-label investigation. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 2018, 2, 483–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xyrem® International Study Group. Further evidence supporting the use of sodium oxybate for the treatment of cataplexy: A double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 228 patients. Sleep Med. 2005, 6, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Houghton, W.C. Sodium oxybate improves excessive daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy. Sleep 2006, 29, 939–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.; Pardi, D.; Hornfeldt, C.S.; Inhaber, N. The nightly administration of sodium oxybate results in significant reduction in the nocturnal sleep disruption of patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 829–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drakatos, P.; Lykouras, D.; D’Ancona, G.; Higgins, S.; Gildeh, N.; Macavei, R.; Rosenzweig, I.; Steier, J.; Williams, A.J.; Muza, R.; et al. Safety and efficacy of long-term use of sodium oxybate for narcolepsy with cataplexy in routine clinical practice. Sleep Med. 2017, 35, 80–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshaikh, M.K.; Tricco, A.C.; Tashkandi, M.; Mamdani, M.; Straus, S.E.; BaHammam, A.S. Sodium oxybate for narcolepsy with cataplexy: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2012, 8, 451–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mamelak, M.; Swick, T.; Emsellem, H.; Montplaisir, J.; Lai, C.; Black, J. A 12-week open-label, multicenter study evaluating the safety and patient-reported efficacy of sodium oxybate in patients with narcolepsy and cataplexy. Sleep Med. 2015, 16, 52–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langford, J.; Gross, W.L. Psychosis in the context of sodium oxybate therapy. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2011, 7, 665–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarkanen, T.; Niemelä, V.; Landtblom, A.M.; Partinen, M. Psychosis in patients with narcolepsy as an adverse effect of sodium oxybate. Front. Neurol. 2014, 5, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lecendreux, M.; Plazzi, G.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Rosen, C.L.; Ruoff, C.; Black, J.; Parvataneni, R.; Guinta, D.; Wang, Y.G.; Mignot, E. Long-term safety and maintenance of efficacy of sodium oxybate in the treatment of narcolepsy with cataplexy in pediatric patients. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2022, 18, 2217–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schinkelshoek, M.S.; Smolders, I.M.; Donjacour, C.E.; van der Meijden, W.P.; van Zwet, E.W.; Fronczek, R.; Lammers, G.J. Decreased body mass index during treatment with sodium oxybate in narcolepsy type 1. J. Sleep Res. 2019, 28, e12684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Bogan, R.K.; Šonka, K.; Partinen, M.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Thorpy, M.J. Calcium, Magnesium, Potassium, and Sodium Oxybates Oral Solution: A Lower-Sodium Alternative for Cataplexy or Excessive Daytime Sleepiness Associated with Narcolepsy. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2022, 14, 531–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogan, R.K.; Foldvary-Schaefer, N.; Skowronski, R.; Chen, A.; Thorpy, M.J. Long-Term Safety and Tolerability During a Clinical Trial and Open-Label Extension of Low-Sodium Oxybate in Participants with Narcolepsy with Cataplexy. CNS Drugs 2023, 37, 323–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneider, L.D.; Morse, A.M.; Strunc, M.J.; Lee-Iannotti, J.K.; Bogan, R.K. Long-Term Treatment of Narcolepsy and Idiopathic Hypersomnia with Low-Sodium Oxybate. Nat. Sci. Sleep 2023, 15, 663–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, A.; Stern, T.; Harsh, J.; Hudson, J.D.; Ajayi, A.O.; Corser, B.C.; Mignot, E.; Santamaria, A.; Morse, A.M.; Abaluck, B.; et al. RESTORE: Once-nightly oxybate dosing preference and nocturnal experience with twice-nightly oxybates. Sleep Med. X 2024, 8, 100122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krahn, L.; Roy, A.; Winkelman, J.W.; Morse, A.M.; Gudeman, J. Assessing Early Efficacy After Initiation of Once-Nightly Sodium Oxybate (ON-SXB; FT218) in Participants with Narcolepsy Type 1 or 2: A Post Hoc Analysis from the Phase 3 REST-ON Trial. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harsh, J.R.; Hayduk, R.; Rosenberg, R.; Wesnes, K.A.; Walsh, J.K.; Arora, S.; Niebler, G.E.; Roth, T. The efficacy and safety of armodafinil as treatment for adults with excessive sleepiness associated with narcolepsy. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2006, 22, 761–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, J.E.; Hull, S.G.; Tiller, J.; Yang, R.; Harsh, J.R. The long-term tolerability and efficacy of armodafinil in patients with excessive sleepiness associated with treated obstructive sleep apnea, shift work disorder, or narcolepsy: An open-label extension study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2010, 6, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitler, M.M.; Shafor, R.; Hajdukovich, R.; Timms, R.M.; Browman, C.P. Treatment of narcolepsy: Objective studies on methylphenidate, pemoline, and protriptyline. Sleep 1986, 9, 260–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonard, B.E.; McCartan, D.; White, J.; King, D.J. Methylphenidate: A review of its neuropharmacological, neuropsychological and adverse clinical effects. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2004, 19, 151–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton, W.C.; Scammell, T.E.; Thorpy, M. Pharmacotherapy for cataplexy. Sleep Med. Rev. 2004, 8, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S.Xyrem® Multicenter Study Group. Sodium oxybate demonstrates long-term efficacy for the treatment of cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2004, 5, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szakacs, Z.; Dauvilliers, Y.; Mikhaylov, V.; Poverennova, I.; Krylov, S.; Jankovic, S.; Sonka, K.; Lehert, P.; Lecomte, I.; Lecomte, J.M.; et al. Safety and efficacy of pitolisant on cataplexy in patients with narcolepsy: A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017, 16, 200–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pillen, S.; Pizza, F.; Dhondt, K.; Scammell, T.E.; Overeem, S. Cataplexy and Its Mimics: Clinical Recognition and Management. Curr. Treat. Options Neurol. 2017, 19, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Greenberg, H. Status cataplecticus precipitated by abrupt withdrawal of venlafaxine. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2013, 9, 715–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, M.; Parkes, J.D. Fluvoxamine and clomipramine in the treatment of cataplexy. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 1980, 43, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, W.R. Treatment of Cataplexy with Clomipramine. Arch. Neurol. 1975, 32, 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilleminault, C.; Raynal, D.; Takahashi, S.; Carskadon, M.; Dement, W. Evaluation of short-term and long-term treatment of the narcolepsy syndrome with clomipramine hydrochloride. Acta Neurol. Scand. 1976, 54, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morgenthaler, T.I.; Kapur, V.K.; Brown, T.; Swick, T.J.; Alessi, C.; Aurora, R.N.; Boehlecke, B.; Chesson, A.L., Jr.; Friedman, L.; Maganti, R.; et al. Practice parameters for the treatment of narcolepsy and other hypersomnias of central origin. Sleep 2007, 30, 1705–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ristanovic, R.K.; Liang, H.; Hornfeldt, C.S.; Lai, C. Exacerbation of cataplexy following gradual withdrawal of antidepressants: Manifestation of probable protracted rebound cataplexy. Sleep Med. 2009, 10, 416–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biscarini, F.; Bassi, C.; Menchetti, M.; Zenesini, C.; Baldini, V.; Franceschini, C.; Varallo, G.; Antelmi, E.; Vignatelli, L.; Pizza, F.; et al. Co-occurrence of anxiety and depressive symptoms, suicidal thoughts, and hopelessness in patients with narcolepsy type 1. Sleep Med. 2024, 124, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, L.E.; Morse, A.M.; Krahn, L.; Lavender, M.; Horsnell, M.; Cronin, D.; Schneider, B.; Gudeman, J. A Survey of People Living with Narcolepsy in the USA: Path to Diagnosis, Quality of Life, and Treatment Landscape from the Patient’s Perspective. CNS Drugs 2025, 39, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudka, S.; Haynes, E.; Scotney, J.; Mukherjee, S.; Frenkel, S.; Sivam, S.; Swieca, J.; Chamula, K.; Cunnington, D.; Saini, B. Narcolepsy: Comorbidities, complexities and future directions. Sleep Med. Rev. 2022, 65, 101669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín Agudelo, H.A.; Jiménez Correa, U.; Carlos Sierra, J.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R.; Schenck, C.H. Cognitive behavioral treatment for narcolepsy: Can it complement pharmacotherapy? Sleep Sci. 2014, 7, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, J.C.; Dawson, S.C.; Mundt, J.M.; Moore, C. Developing a cognitive behavioral therapy for hypersomnia using telehealth: A feasibility study. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2020, 16, 2047–2062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roehrs, T.; Zorick, F.; Wittig, R.; Paxton, C.; Sicklesteel, J.; Roth, T. Alerting effects of naps in patients with narcolepsy. Sleep 1986, 9, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullington, J.; Broughton, R. Scheduled naps in the management of daytime sleepiness in narcolepsy-cataplexy. Sleep 1993, 16, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchiyama, M.; Mayer, G.; Meier-Ewert, K. Differential effects of extended sleep in narcoleptic patients. Electroencephalogr. Clin. Neurophysiol. 1994, 91, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filardi, M.; Pizza, F.; Antelmi, E.; Pillastrini, P.; Natale, V.; Plazzi, G. Physical Activity and Sleep/Wake Behavior, Anthropometric, and Metabolic Profile in Pediatric Narcolepsy Type 1. Front. Neurol. 2018, 9, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronczek, R.; Raymann, R.J.; Romeijn, N.; Overeem, S.; Fischer, M.; van Dijk, J.G.; Lammers, G.J.; Van Someren, E.J. Manipulation of core body and skin temperature improves vigilance and maintenance of wakefulness in narcolepsy. Sleep 2008, 31, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, A.M.; Yancy, W.S., Jr.; Carwile, S.T.; Miller, P.P.; Westman, E.C. Diet therapy for narcolepsy. Neurology 2004, 62, 2300–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mundt, J.M.; Pruiksma, K.E.; Konkoly, K.R.; Casiello-Robbins, C.; Nadorff, M.R.; Franklin, R.C.; Karanth, S.; Byskosh, N.; Morris, D.J.; Torres-Platas, S.G.; et al. Treating narcolepsy-related nightmares with cognitive behavioural therapy and targeted lucidity reactivation: A pilot study. J. Sleep Res. 2025, 34, e14384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, D.G.; Jesteadt, L.; Crisp, C.; Simon, S.L. Treatment and care delivery in pediatric narcolepsy: A survey of parents, youth, and sleep physicians. J. Clin. Sleep Med. 2021, 17, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorpy, M.; Zhao, C.G.; Dauvilliers, Y. Management of narcolepsy during pregnancy. Sleep Med. 2013, 14, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kovalská, P.; Kemlink, D.; Nevšímalová, S.; Maurovich Horvat, E.; Jarolímová, E.; Topinková, E.; Šonka, K. Narcolepsy with cataplexy in patients aged over 60 years: A case-control study. Sleep Med. 2016, 26, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakravorty, S.S.; Rye, D.B. Narcolepsy in the older adult: Epidemiology, diagnosis and management. Drugs Aging 2003, 20, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irukayama-Tomobe, Y.; Ogawa, Y.; Tominaga, H.; Ishikawa, Y.; Hosokawa, N.; Ambai, S.; Kawabe, Y.; Uchida, S.; Nakajima, R.; Saitoh, T.; et al. Nonpeptide orexin type-2 receptor agonist ameliorates narcolepsy-cataplexy symptoms in mouse models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, 5731–5736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, H.; Nagumo, Y.; Ishikawa, Y.; Irukayama-Tomobe, Y.; Namekawa, Y.; Nemoto, T.; Tanaka, H.; Takahashi, G.; Tokuda, A.; Saitoh, T.; et al. OX2R-selective orexin agonism is sufficient to ameliorate cataplexy and sleep/wake fragmentation without inducing drug-seeking behavior in mouse model of narcolepsy. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Hara, H.; Kawano, A.; Kimura, H. Danavorexton, a selective orexin 2 receptor agonist, provides a symptomatic improvement in a narcolepsy mouse model. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2022, 220, 173464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Ranjan, A.; Tisdale, R.; Ma, S.C.; Park, S.; Haire, M.; Heu, J.; Morairty, S.R.; Wang, X.; Rosenbaum, D.M.; et al. Evaluation of the efficacy of the hypocretin/orexin receptor agonists TAK-925 and ARN-776 in narcoleptic orexin/tTA; TetO-DTA mice. J. Sleep Res. 2023, 32, e13839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa, T.; Hara, H.; Kawano, A.; Tohyama, K.; Kajita, Y.; Miyanohana, Y.; Koike, T.; Kimura, H. TAK-994, a Novel Orally Available Brain-Penetrant Orexin 2 Receptor-Selective Agonist, Suppresses Fragmentation of Wakefulness and Cataplexy-Like Episodes in Mouse Models of Narcolepsy. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2023, 385, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsukawa, K.; Terada, M.; Yamada, R.; Monjo, T.; Hiyoshi, T.; Nakakariya, M.; Kajita, Y.; Ando, T.; Koike, T.; Kimura, H. TAK-861, a potent, orally available orexin receptor 2-selective agonist, produces wakefulness in monkeys and improves narcolepsy-like phenotypes in mouse models. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 20838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzi, D.; Siegrist, R.; Peters, J.U.; Kohl, C.; Mühlemann, A.; Schlienger, S.; Torrisi, C.; Lindenberg, E.; Kessler, M.; Roch, C. Discovery of a New Class of Orexin 2 Receptor Agonists as a Potential Treatment for Narcolepsy. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 10173–10189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evans, R.; Kimura, H.; Alexander, R.; Davies, C.H.; Faessel, H.; Hartman, D.S.; Ishikawa, T.; Ratti, E.; Shimizu, K.; Suzuki, M.; et al. Orexin 2 receptor-selective agonist danavorexton improves narcolepsy phenotype in a mouse model and in human patients. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207531119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Mignot, E.; Del Río Villegas, R.; Du, Y.; Hanson, E.; Inoue, Y.; Kadali, H.; Koundourakis, E.; Meyer, S.; Rogers, R.; et al. Oral Orexin Receptor 2 Agonist in Narcolepsy Type 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 309–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinozawa, T.; Miyamoto, K.; Baker, K.S.; Faber, S.C.; Flores, R.; Uetrecht, J.; von Hehn, C.; Yukawa, T.; Tohyama, K.; Kadali, H.; et al. TAK-994 mechanistic investigation into drug-induced liver injury. Toxicol. Sci. 2025, 204, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Plazzi, G.; Mignot, E.; Lammers, G.J.; Del Río Villegas, R.; Khatami, R.; Taniguchi, M.; Abraham, A.; Hang, Y.; Kadali, H.; et al. Oveporexton, an Oral Orexin Receptor 2-Selective Agonist, in Narcolepsy Type 1. N. Engl. J. Med. 2025, 392, 1905–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignot, E.; Arnulf, I.; Plazzi, G. Efficacy and safety of Oveporexton (TAK-861), an oral orexin receptor 2 agonist for the treatment of narcolepsy type 1: Results from a phase 3 randomized study in Europe, Japan, and North America. In Proceedings of the World Sleep Congress 2025, Singapore, 8 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Dauvilliers, Y.; Antczak, J.; Buntinx, E.; del Rio Villegas, R.; Hong, S.C.; Sivam, S.; Zhan, S.; Koundourakis, E.; Neuwirth, R.; Olsson, T.; et al. Efficacy and safety of Oveporexton (TAK-861) for the treatment of narcolepsy type 1: Results from a phase 3 randomized study in Asia, Australia, and Europe. In Proceedings of the World Sleep Congress 2025, Singapore, 8 September 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Tian, R.; Wei, S.; Yang, H.; Zhu, C.; Li, Z. Activation of orexin receptor 2 plays anxiolytic effect in male mice. Brain Res. 2025, 1859, 149646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, J.; Wu, M.F.; Siegel, J.M. Systemic administration of hypocretin-1 reduces cataplexy and normalizes sleep and waking durations in narcoleptic dogs. Sleep Res. Online 2000, 3, 23–28. [Google Scholar]