Factors Affecting Mortality Following Hip Fracture Surgery: Insights from a Long-Term Study at a Level I Trauma Center—Does Timing Matter?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Subgroup Analyses Regarding Baseline Characteristics and Mortality Rates

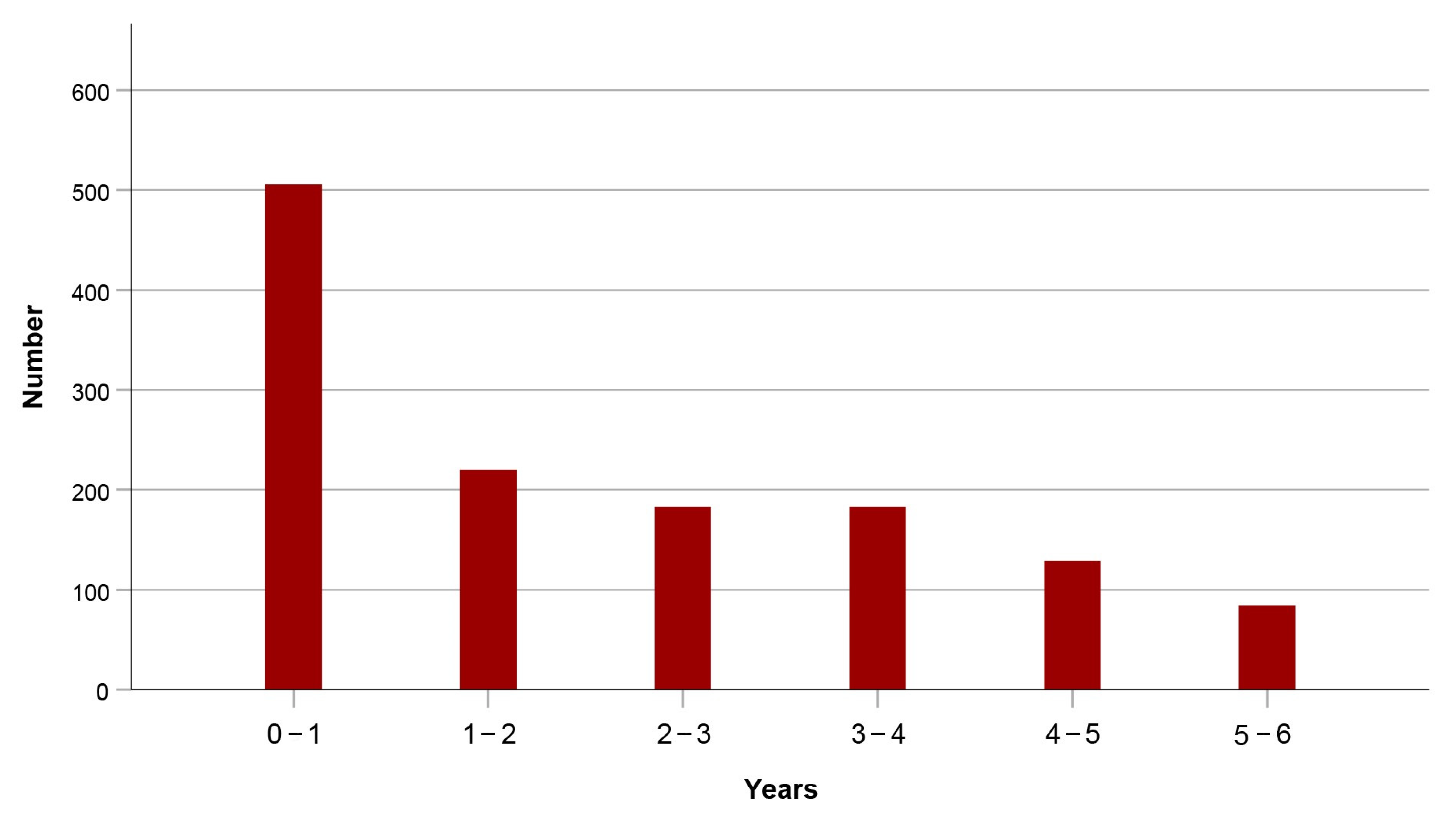

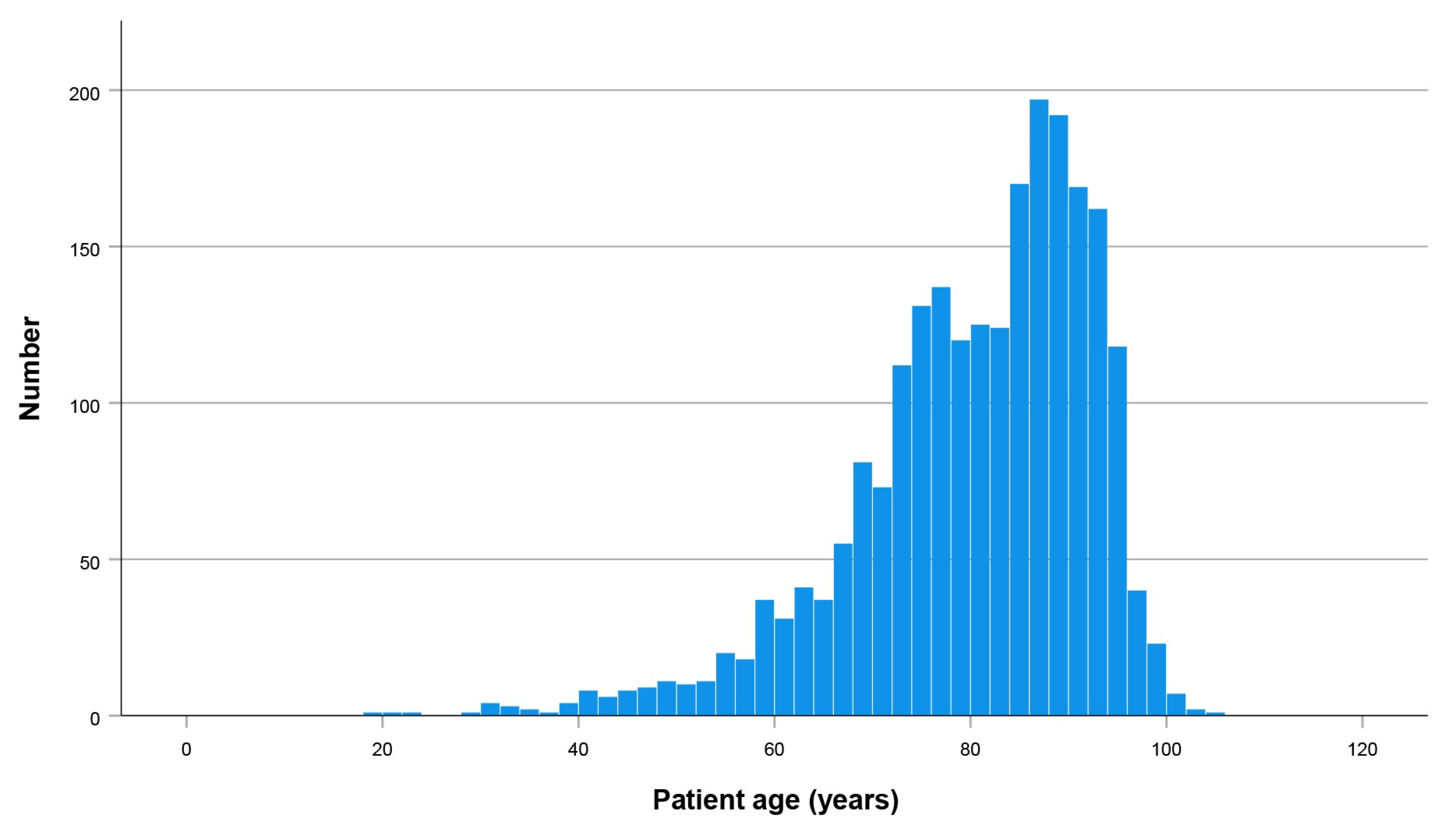

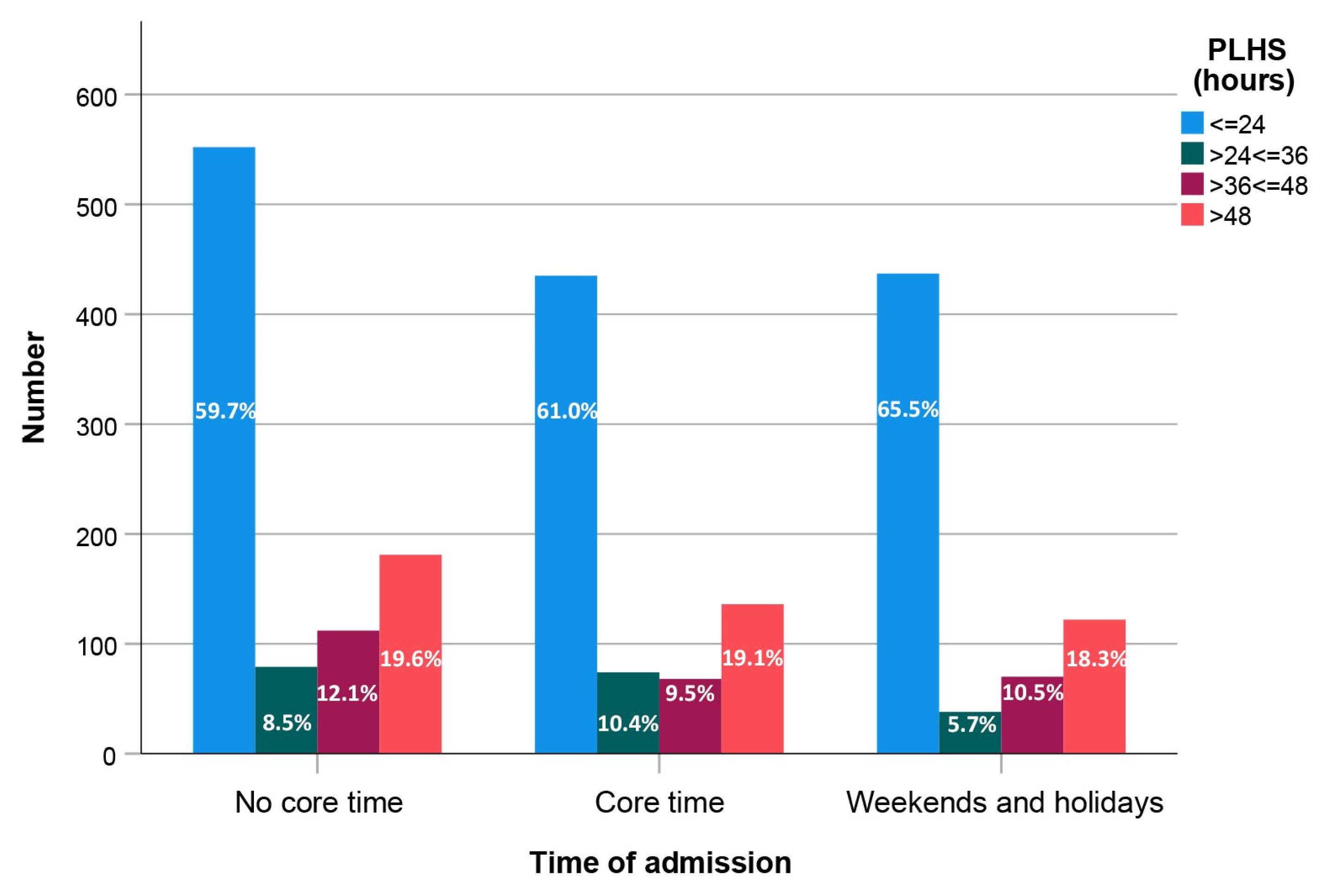

3.2. Distribution of Patient Ages and Admission Times

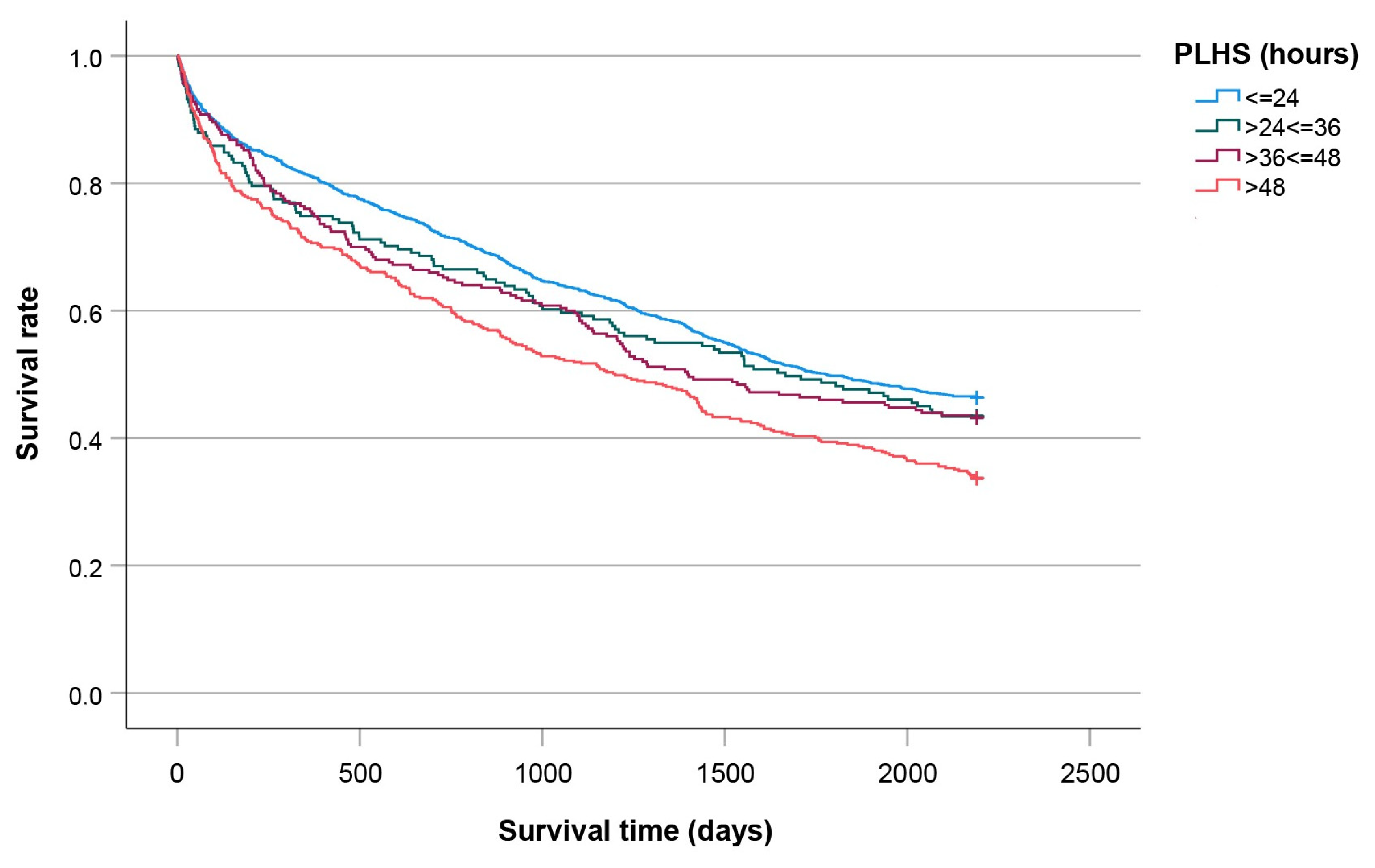

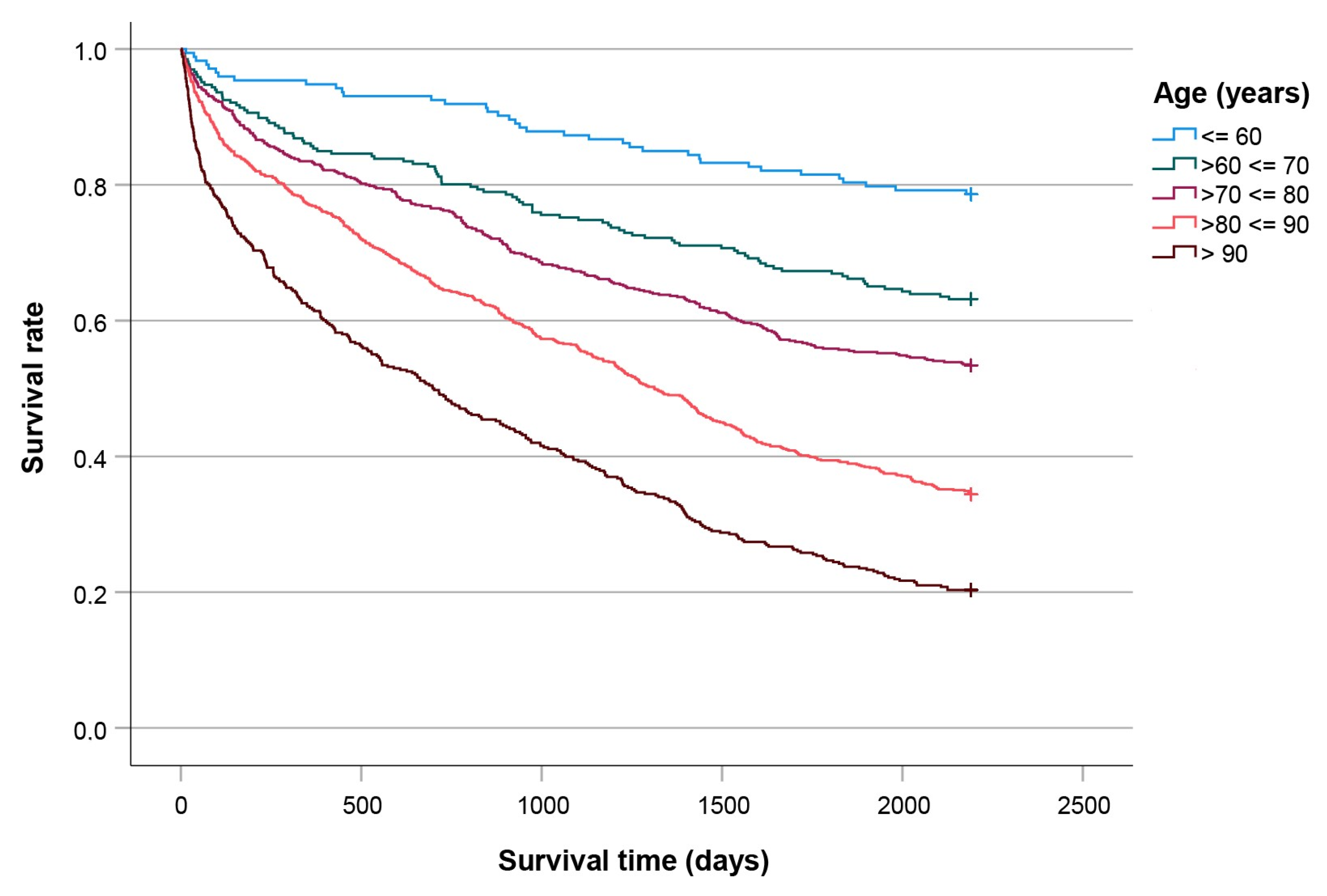

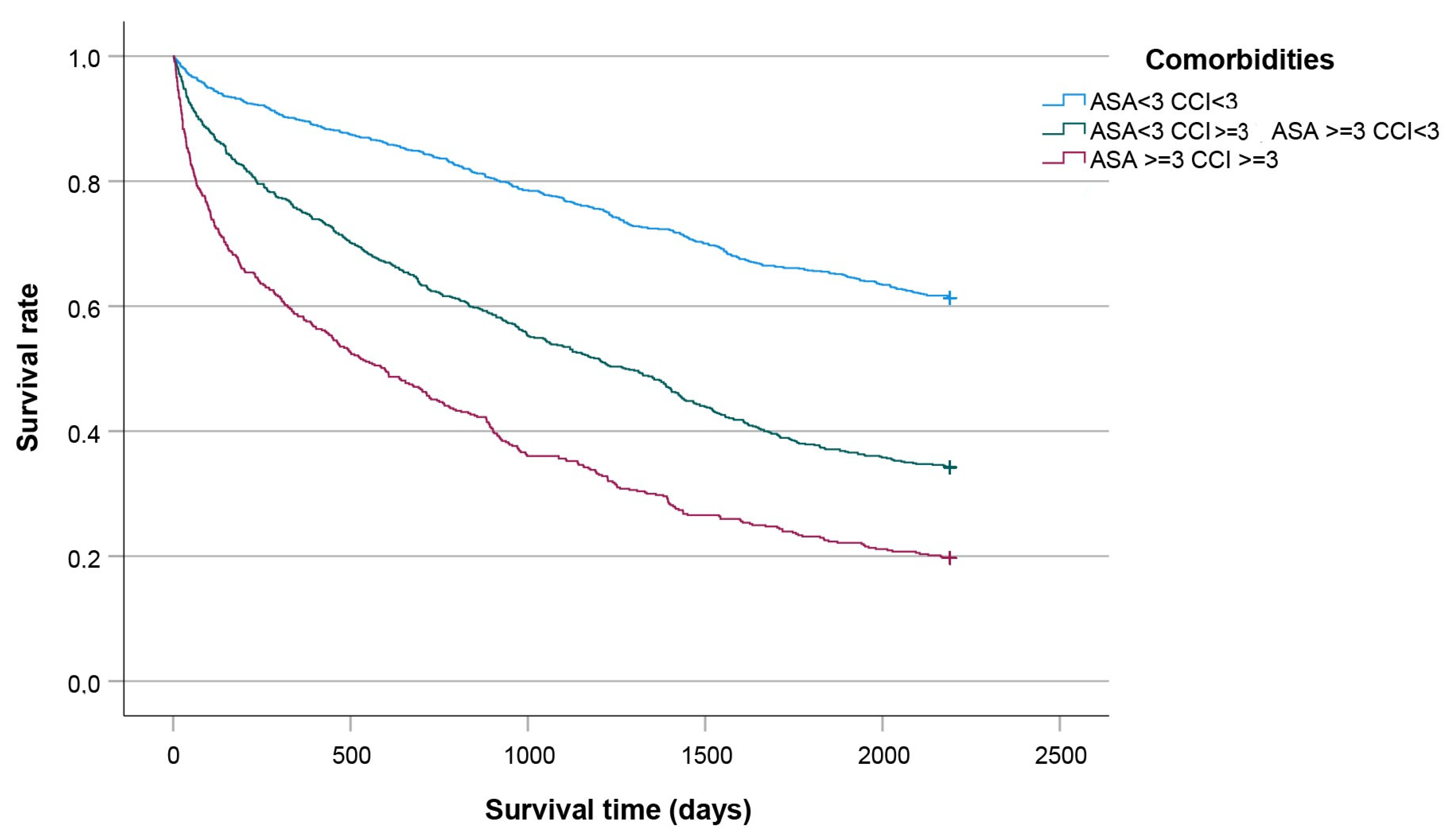

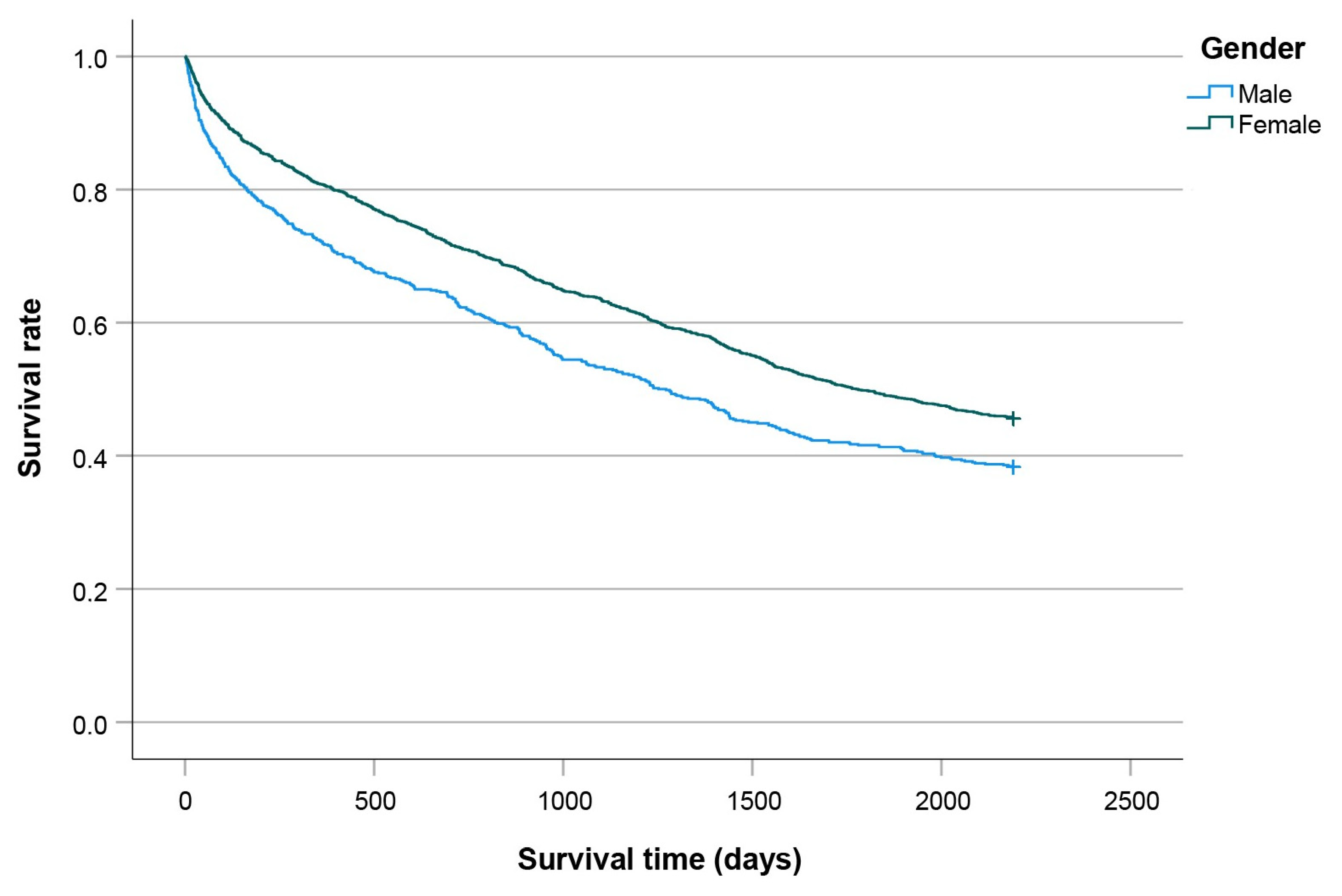

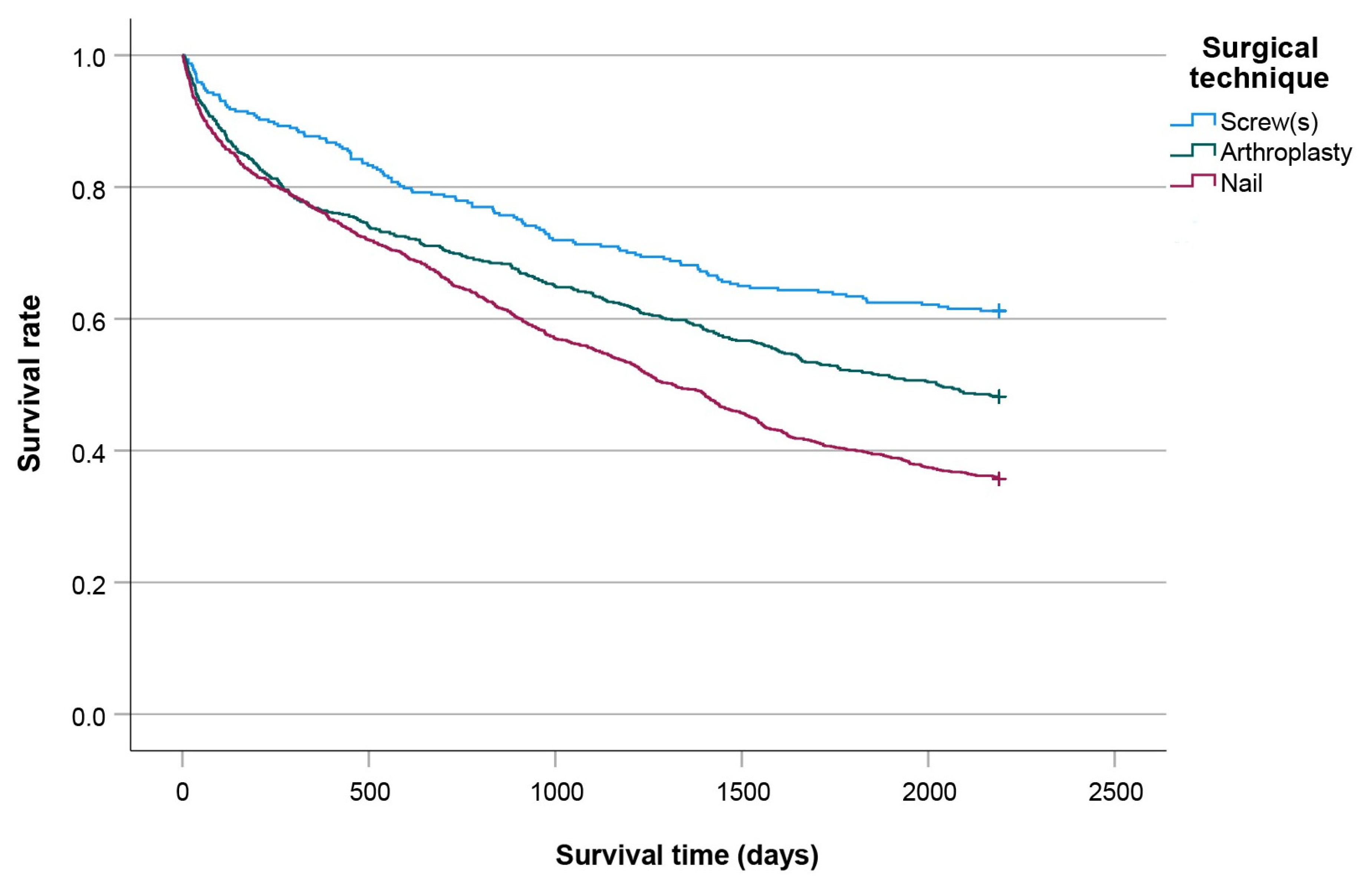

3.3. Kaplan-Meier Curves

3.4. Cox Regression Analyses

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Leal, J.; Gray, A.M.; Prieto-Alhambra, D.; Arden, N.K.; Cooper, C.; Javaid, M.K.; Judge, A. REFReSH study group. Impact of hip fracture on hospital care costs: A population-based study. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 549–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-P.; Kuo, Y.-J.; Liu, C.-H.; Chien, P.-C.; Chang, W.-C.; Lin, C.-Y.; Pakpour, A.H. Prognostic factors for 1-year functional outcome, quality of life, care demands, and mortality after surgery in Taiwanese geriatric patients with a hip fracture: A prospective cohort study. Ther. Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis. 2021, 13, 1759720X211028360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Prospects 2022: Summary of Results. UN DESA/POP/2022/TR/NO. 3. 2022. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/wpp2022_summary_of_results.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2025).

- Holvik, K.; Ellingsen, C.L.; Solbakken, S.M.; Finnes, T.E.; Talsnes, O.; Grimnes, G.; Tell, G.S.; Søgaard, A.-J.; Meyer, H.E. Correction to: Cause-specific excess mortality after hip fracture: The Norwegian Epidemiologic Osteoporosis Studies (NOREPOS). BMC Geriatr. 2023, 23, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsoulis, M.; Benetou, V.; Karapetyan, T.; Feskanich, D.; Grodstein, F.; Pettersson-Kymmer, U.; Eriksson, S.; Wilsgaard, T.; Jørgensen, L.; Ahmed, L.A.; et al. Excess mortality after hip fracture in elderly persons from Europe and the USA: The CHANCES project. J. Intern. Med. 2017, 281, 300–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubljanin-Raspopović, E.; Marković-Denić, L.; Marinković, J.; Nedeljković, U.; Bumbaširević, M. Does early functional outcome predict 1-year mortality in elderly patients with hip fracture? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 2703–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klestil, T.; Röder, C.; Stotter, C.; Winkler, B.; Nehrer, S.; Lutz, M.; Klerings, I.; Wagner, G.; Gartlehner, G.; Nussbaumer-Streit, B. Impact of timing of surgery in elderly hip fracture patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 13933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welford, P.; Jones, C.S.; Davies, G.; Kunutsor, S.K.; Costa, M.L.; Sayers, A.; Whitehouse, M.R. The association between surgical fixation of hip fractures within 24 hours and mortality: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Bone Jt. J. 2021, 103, 1176–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristiansson, J.; Hagberg, E.; Nellgård, B. The influence of time-to-surgery on mortality after a hip fracture. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2020, 64, 347–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztürk, B.; Johnsen, S.P.; Röck, N.D.; Pedersen, L.; Pedersen, A.B. Impact of comorbidity on the association between surgery delay and mortality in hip fracture patients: A Danish nationwide cohort study. Injury 2019, 50, 424–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hongisto, M.T.; Nuotio, M.S.; Luukkaala, T.; Väistö, O.; Pihlajamäki, H.K. Delay to Surgery of Less Than 12 Hours Is Associated with Improved Short- and Long-Term Survival in Moderate- to High-Risk Hip Fracture Patients. Geriatr. Orthop. Surg. Rehabil. 2019, 10, 2151459319853142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leer-Salvesen, S.; Engesæter, L.B.; Dybvik, E.; Furnes, O.; Kristensen, T.B.; Gjertsen, J.E. Does time from fracture to surgery affect mortality and intraoperative medical complications for hip fracture patients? An observational study of 73,557 patients reported to the Norwegian Hip Fracture Register. Bone Jt. J. 2019, 101, 1129–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iida, H.; Takegami, Y.; Sakai, Y.; Watanabe, T.; Osawa, Y.; Imagama, S. Early surgery within 48 hours of admission for hip fracture did not improve 1-year mortality in Japan: A single-institution cohort study. Hip Int. 2024, 34, 660–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristan, A.; Omahen, S.; Cimerman, M. Causes for Delay to Surgery in Hip Fractures and How It Impacts on Mortality: A Single Level 1 Trauma Center Experience. Acta Chir. Orthop. Traumatol. Cech. 2021, 88, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huette, P.; Abou-Arab, O.; Djebara, A.-E.; Terrasi, B.; Beyls, C.; Guinot, P.-G.; Havet, E.; Dupont, H.; Lorne, E.; Ntouba, A.; et al. Risk factors and mortality of patients undergoing hip fracture surgery: A one-year follow-up study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Huang, P.-J.; Huang, H.-T.; Lin, S.-Y.; Wang, H.-Y.; Fang, T.-J.; Lin, Y.-C.; Ho, C.-J.; Lee, T.-C.; Lu, Y.-M.; et al. Impact of orthogeriatric care, comorbidity, and complication on 1-year mortality in surgical hip fracture patients: An observational study. Medicine 2019, 98, e17912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lund, C.A.; Møller, A.M.; Wetterslev, J.; Lundstrøm, L.H. Organizational factors and long-term mortality after hip fracture surgery. A cohort study of 6143 consecutive patients undergoing hip fracture surgery. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e99308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smektala, R.; Endres, H.G.; Dasch, B.; Maier, C.; Trampisch, H.J.; Bonnaire, F.; Pientka, L. The effect of time-to-surgery on outcome in elderly patients with proximal femoral fractures. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2008, 9, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gdalevich, M.; Cohen, D.; Yosef, D.; Tauber, C. Morbidity and mortality after hip fracture: The impact of operative delay. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2004, 124, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åhman, R.; Siverhall, P.F.; Snygg, J.; Fredrikson, M.; Enlund, G.; Björnström, K.; Chew, M.S. Determinants of mortality after hip fracture surgery in Sweden: A registry-based retrospective cohort study. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greve, K.; Modig, K.; Talbäck, M.; Bartha, E.; Hedström, M. No association between waiting time to surgery and mortality for healthier patients with hip fracture: A nationwide Swedish cohort of 59,675 patients. Acta Orthop. 2020, 91, 396–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Jang, S.-Y.; Cha, Y.; Jang, H.; Kim, B.-Y.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, G.-O. The Impact of Hospital Volume and Region on Mortality, Medical Costs, and Length of Hospital Stay in Elderly Patients Following Hip Fracture: A Nationwide Claims Database Analysis. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2025, 17, 80–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farley, B.J.; Shear, B.M.; Lu, V.; Walworth, K.; Gray, K.; Kirsch, M.; Clements, J.M. Rural, urban, and teaching hospital differences in hip fracture mortality. J. Orthop. 2020, 21, 453–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total | PLHS | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≤24 h | >24 h, ≤36 h | >36 h, ≤48 h | >48 h | ||||

| Patients (n) | 2304 | 1424 (61.8%) | 191 (8.3%) | 250 (10.9%) | 439 (19.1%) | ||

| Female | 69.6% | 71.3% | 71.2% | 72.4% | 62.0% | 0.020 | |

| Age (y) | 82 [19, 104] | 82 [19, 104] | 81 [40, 99] | 84 [32, 101] | 82 [41, 97] | 0.272 | |

| ASA ≥ 3 | 53.2% | 43.2% | 63.4% | 62.8% | 75.3% | <0.001 | |

| CCI ≥ 3 | 22.5% | 16.9% | 28.4% | 23.9% | 37.4% | <0.001 | |

| Femoral neck fractures | 46.4% | 39.0% | 49.7% | 54.4% | 64.2% | <0.001 | |

| Intertrochanteric fractures | 45.3% | 52.3% | 41.9% | 38.8% | 27.6% | ||

| Subtrochanteric fractures | 3.7% | 3.7% | 4.2% | 4.0% | 3.2% | ||

| Inter- + subtroch. fractures | 4.6% | 4.9% | 4.2% | 2.8% | 5.0% | ||

| Additional injury | 6.8% | 6.8% | 6.8% | 6.0% | 7.1% | 0.960 | |

| Anticoagulation therapy | 48.4% | 38.9% | 54.3% | 64.1% | 71.9% | <0.001 | |

| Anesthesia | Regional | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.0% | 0.4% | 0.7% | <0.001 |

| Spinal | 59.3% | 66.1% | 57.4% | 51.2% | 44.9% | ||

| General | 39.6% | 33.6% | 42.6% | 48.4% | 54.1% | ||

| Type of surgery | Screws | 5.6% | 6.1 | 4.7 | 4.4 | 5.3 | <0.001 |

| Dynamic hip screw | 8.2% | 11.4 | 4.7 | 3.2 | 2.5 | ||

| Short nail | 44.7% | 50.8 | 44.0 | 39.6 | 28.5 | ||

| Long nail | 8.0% | 9.3 | 5.8 | 5.2 | 6.4 | ||

| Hemiarthroplasty | 27.8% | 20.1 | 33.0 | 36.8 | 45.9 | ||

| Total arthroplasty | 5.4% | 2.3 | 7.9 | 10.8 | 11.4 | ||

| Duration of surgery (min) | 65 [10, 295] | 60 [13, 295] | 70 [20, 190] | 70 [15, 225] | 80 [10, 250] | <0.001 | |

| Post-surgery hospital stay (d) | 12 [0, 145] | 12 [1, 145] | 12 [0, 92] | 12 [1, 78] | 13 [0, 78] | <0.001 | |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 13 [1, 145] | 12 [2, 145] | 13 [1, 93] | 14 [3, 80] | 17 [3, 78] | <0.001 | |

| Stay in the ICU | 2.7% | 1.3% | 4.2% | 3.2% | 6.9% | <0.001 | |

| Complications | None | 66.4% | 69.7% | 57.1% | 66.4% | 59.7% | 0.002 |

| Surgical | 5.7% | 5.4% | 6.8% | 6.0% | 5.9% | ||

| General | 25.3% | 22.8% | 33.0% | 24.4% | 30.3% | ||

| Both | 2.8% | 2.1% | 3.1% | 3.2% | 4.1% | ||

| In-hospital mortality rate | 3.6% | 2.7% | 7.3% | 2.8% | 5.5% | 0.001 | |

| 30-day mortality rate | 5.2% | 4.8% | 6.8% | 4.8% | 5.9% | 0.592 | |

| One-year mortality rate | 22.0% | 19.0% | 25.1% | 24.4% | 28.9% | <0.001 | |

| Six-year mortality rate | 56.6% | 53.7% | 56.5% | 56.8% | 66.3% | <0.001 | |

| PLHS ≤ 24 h | 24 h < PLHS ≤ 36 h | 36 h < PLHS ≤ 48 h | PLHS > 48 h | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survivor | Fatality | Survivor | Fatality | Survivor | Fatality | Survivor | Fatality | |

| Patients (n) | 1154 | 270 | 143 | 48 | 189 | 61 | 312 | 127 |

| Age (y) | 81 [19, 104] | 87 [45, 101] | 79 [40, 98] | 89 [66, 98] | 83 [32, 98] | 87 [55, 101] | 80 [51, 97] | 87 [41, 97] |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.013 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| ASA ≥ 3 | 37.7% | 67.0% | 55.2% | 87.5% | 58.2% | 77.0% | 68.6% | 92.1% |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.008 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| CCI ≥ 3 | 12.6% | 36.0% | 23.1% | 44.7% | 20.4% | 34.4% | 30.4% | 54.8% |

| p < 0.001 | p = 0.004 | p = 0.026 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| 60 y < Age≤ 70 y | 70 y < Age≤ 80 y | 80 y < Age≤ 90 y | Age > 90 y | |||||

| Survivor | Fatality | Survivor | Fatality | Survivor | Fatality | Survivor | Fatality | |

| Patients (n) | 228 | 38 | 503 | 102 | 633 | 189 | 270 | 168 |

| PLHS | 21 [1, 355] | 25 [3, 269] | 16 [1, 255] | 23 [2, 840] | 15 [2, 422] | 25 [2, 318] | 16 [1, 155] | 18 [1, 784] |

| p = 0.646 | p = 0.042 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.344 | |||||

| ASA ≥ 3 | 39.5% | 78.9% | 44.7% | 85.1% | 50.9% | 72.3% | 58.4% | 74.8% |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| CCI ≥ 3 | 17.6% | 57.9% | 19.3% | 54.5% | 16.5% | 36.1% | 20.6% | 35.4% |

| p = 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | |||||

| Total | Dynamic Hip Screw | Short and Long Nails | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 1144 | 17 | 1127 | |

| Female | 71.6% | 58.8% | 71.8% | 0.240 |

| Age (y) | 84 [28, 104] | 80 [28, 92] | 84 [32, 104] | 0.019 |

| ASA ≥ 3 | 54.5% | 41.2% | 54.7% | 0.267 |

| CCI ≥ 3 | 24.4% | 11.8% | 24.5% | 0.223 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 50 [13, 295] | 60 [30, 135] | 50 [13, 295] | 0.059 |

| PLHS (h) | 13 [1, 422] | 12 [3, 287] | 13 [1, 422] | 0.506 |

| Post-surgery hospital stay (d) | 12 [0, 145] | 12 [5, 21] | 12 [0, 145] | 0.424 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 13 [2, 145] | 12 [5, 26) | 13 [2, 145] | 0.586 |

| Stay in the ICU | 2.6% | 0.0% | 2.6% | 0.459 |

| In-hospital complications | 33.4% | 29.4% | 33.5% | 0.726 |

| In-hospital mortality | 4.1% | 0.0% | 4.1% | 0.390 |

| 30-day mortality | 6.5.% | 0.0% | 6.5% | 0.275 |

| One-year mortality | 23.8% | 17.6% | 23.9% | 0.550 |

| Six-year mortality | 64.8% | 52.9% | 65.0% | 0.304 |

| Total | Screws/DHS | Arthroplasty | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients (n) | 1062 | 302 | 760 | |

| Female | 67.1% | 63.6% | 68.6% | 0.119 |

| Age (y) | 80 [21, 101] | 76 [21, 100] | 82 [41, 101] | <0.001 |

| ASA ≥ 3 | 51.4% | 45.8% | 53.6% | 0.023 |

| CCI ≥ 3 | 20.3% | 16.6% | 21.7% | 0.062 |

| Duration of surgery (min) | 85 [5, 250] | 49 [10, 180] | 95 [5, 250] | <0.001 |

| PLHS (h) | 23 [1, 840] | 7 [1, 784] | 35 [2, 840] | <0.001 |

| Post-surgery hospital stay (d) | 12 [0, 92] | 11 [0, 64] | 12 [0, 92] | <0.001 |

| Length of hospital stay (d) | 13 [1, 93] | 12 [3, 64] | 14 [1, 93] | <0.001 |

| Stay in the ICU | 2.9% | 1.3% | 3.6% | 0.052 |

| In-hospital complications | 33.5% | 26.8% | 36.2% | 0.004 |

| In-hospital mortality | 2.8% | 1.7% | 3.3% | 0.147 |

| 30-day mortality | 3.8.% | 2.3% | 4.3% | 0.118 |

| One-year mortality | 20.3% | 12.6% | 23.4% | <0.001 |

| Six-year mortality | 48.4% | 38.4% | 52.4% | <0.001 |

| Covariates | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | aHR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| PLHS ≤ 24 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.703 | 0.614 | 0.804 | <0.001 | 0.890 | 0.767 | 1.033 | 0.126 |

| 24 h < PLHS ≤ 36 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.779 | 0.624 | 0.971 | 0.026 | 0.826 | 0.660 | 1.035 | 0.097 |

| 36 h < PLHS ≤ 48 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.795 | 0.650 | 0.971 | 0.025 | 0.860 | 0.700 | 1.057 | 0.151 |

| Intertrochanteric vs. femoral neck f | 1.508 | 1.344 | 1.691 | <0.001 | 1.406 | 1.161 | 1.703 | <0.001 |

| Subtrochanteric vs. femoral neck f | 1.164 | 0.861 | 1.574 | 0.463 | 1.139 | 0.804 | 1.615 | 0.463 |

| Inter- and subtroch. vs. femoral neck f | 1.482 | 1.151 | 1.909 | 0.002 | 1.609 | 1.193 | 2.170 | 0.002 |

| Arthroplasty vs. osteosynthesis | 0.841 | 0.747 | 0.946 | 0.004 | 1.005 | 0.819 | 1.233 | 0.965 |

| No core time vs. weekend/holiday | 0.922 | 0.808 | 1.052 | 0.226 | ||||

| Core time vs. weekend/holiday | 0.970 | 0.844 | 1.112 | 0.664 | ||||

| No core time vs. core time | 1.031 | 0.897 | 1.185 | 0.445 | ||||

| Age (y) | 1.050 | 1.044 | 1.057 | <0.001 | 1.050 | 1.044 | 1.056 | <0.001 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.780 | 0.695 | 0.875 | <0.001 | 0.596 | 0.527 | 0.674 | <0.001 |

| ASA (≥3 vs. <3) | 2.565 | 2.283 | 2.881 | <0.001 | 1.716 | 1.501 | 1.962 | <0.001 |

| CCI (≥3 vs. <3) | 2.427 | 2.156 | 2.732 | <0.001 | 1.632 | 1.430 | 1.861 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital complications (yes vs. no) | 1.417 | 1.267 | 1.585 | <0.001 | 1.207 | 1.072 | 1.357 | 0.002 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 1.015 | 1.009 | 1.020 | <0.001 | 1.007 | 1.001 | 1.013 | 0.026 |

| Femoral Neck Fractures | Intertrochanteric Fractures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | aHR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| PLHS ≤ 24 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.903 | 0.727 | 1.112 | 0.356 | 0.872 | 0.693 | 1.099 | 0.246 |

| 24 h < PLHS ≤ 36 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 1.040 | 0.755 | 1.434 | 0.809 | 0.611 | 0.428 | 0.872 | 0.007 |

| 36 h < PLHS ≤ 48 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.913 | 0.678 | 1.230 | 0.549 | 0.845 | 0.618 | 1.156 | 0.293 |

| Age (y) | 1.049 | 1.039 | 1.059 | <0.001 | 1.048 | 1.039 | 1.057 | <0.001 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.637 | 0.529 | 0.766 | <0.001 | 0.576 | 0.482 | 0.689 | <0.001 |

| ASA (≥3 vs. <3) | 1.923 | 1.549 | 2.389 | <0.001 | 1.612 | 1.339 | 1.941 | <0.001 |

| CCI (≥3 vs. <3) | 1.780 | 1.442 | 2.196 | <0.001 | 1.520 | 1.265 | 1.827 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital complications (yes vs. no) | 1.194 | 0.993 | 1.436 | 0.060 | 1.267 | 1.073 | 1.497 | 0.005 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 1.012 | 1.003 | 1.020 | 0.006 | 0.999 | 0.989 | 1.009 | 0.817 |

| Arthroplasty vs. osteosynthesis | 1.029 | 0.827 | 1.281 | 0.796 | ||||

| Subtrochanteric Fractures | Both Inter- and Subtrochanteric Fractures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | HR | 95% CI | p-Value | aHR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| PLHS ≤ 24 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 1.274 | 0.517 | 3.139 | 0.598 | 0.721 | 0.377 | 1.377 | 0.321 |

| 24 h < PLHS ≤ 36 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 6.421 | 1.749 | 25,564 | 0.005 | 0.648 | 0.247 | 1.698 | 0.377 |

| 36 h < PLHS ≤ 48 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 1.843 | 0.516 | 6582 | 0.347 | 0.481 | 0.157 | 1.475 | 0.200 |

| Age (y) | 1.084 | 1.048 | 1.122 | <0.001 | 1.070 | 1.037 | 1.104 | <0.001 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.400 | 0.171 | 0.934 | 0.034 | 0.357 | 0.189 | 0.674 | 0.002 |

| ASA (≥3 vs. <3) | 3.242 | 1.322 | 7.953 | 0.010 | 1.191 | 0.672 | 2.111 | 0.550 |

| CCI (≥3 vs. <3) | 1.376 | 0.643 | 2.942 | 0.411 | 1.668 | 0.893 | 3.116 | 0.109 |

| In-hospital complications (yes vs. no) | 0.941 | 0.463 | 1.910 | 0.865 | 1.395 | 0.805 | 2.417 | 0.235 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 1.011 | 0.984 | 1.038 | 0.439 | 1.015 | 0.997 | 1.033 | 0.113 |

| Patients < 65 Years | Patients ≥ 65 Years | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | aHR | 95% CI | p-Value | aHR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| PLHS ≤ 24 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.787 | 0.383 | 1.618 | 0.515 | 0.963 | 0.826 | 1.122 | 0.627 |

| 24 h < PLHS ≤ 36 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.251 | 0.055 | 1.148 | 0.075 | 0.868 | 0.690 | 1.090 | 0.222 |

| 36 h < PLHS ≤ 48 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.477 | 0.137 | 1.660 | 0.245 | 0.933 | 0.757 | 1.150 | 0.516 |

| Intertrochanteric vs. femoral neck f | 2.473 | 1.041 | 5.870 | 0.040 | 1.514 | 1.248 | 1.836 | <0.001 |

| Subtrochanteric vs. femoral neck f | 0.460 | 0.081 | 2.607 | 0.381 | 1.204 | 1.210 | 1.717 | 0.306 |

| Inter- and subtroch. vs. femoral neck f | 1.069 | 0.122 | 9.402 | 0.952 | 1.638 | 1.210 | 2.217 | 0.001 |

| Arthroplasty vs. osteosynthesis | 2.215 | 0.822 | 5.965 | 0.116 | 1.026 | 0.834 | 1.262 | 0.809 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.622 | 0.353 | 1.097 | 0.101 | 0.689 | 0.609 | 0.781 | <0.001 |

| ASA (≥3 vs. <3) | 4.409 | 2.154 | 9.022 | <0.001 | 1.822 | 1.592 | 2.085 | <0.001 |

| CCI (≥3 vs. <3) | 1.693 | 0.822 | 3.486 | 0.153 | 1.536 | 1.343 | 1.757 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital complications (yes vs. no) | 0.984 | 0.535 | 1.810 | 0.960 | 1.270 | 1.126 | 1.432 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 1.028 | 0.999 | 1.057 | 0.060 | 1.004 | 0.998 | 1.010 | 0.160 |

| Patients with ASA < 3 | Patients with ASA ≥ 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covariates | aHR | 95% CI | p-Value | aHR | 95% CI | p-Value | ||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| PLHS ≤ 24 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.842 | 0.598 | 1.187 | 0.327 | 0.896 | 0.757 | 1.060 | 0.199 |

| 24 h < PLHS ≤ 36 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.962 | 0.592 | 1.564 | 0.876 | 0.805 | 0.622 | 1.042 | 0.099 |

| 36 h < PLHS ≤ 48 h vs. PLHS > 48 h | 0.896 | 0.565 | 1.422 | 0.642 | 0.867 | 0.688 | 1.093 | 0.228 |

| Intertrochanteric vs. femoral neck f | 2.039 | 1.433 | 2.901 | <0.001 | 1.171 | 0.933 | 1.471 | 0.596 |

| Subtrochanteric vs. femoral neck f | 1.215 | 0.536 | 2.623 | 0.620 | 1.078 | 0.726 | 1.599 | 0.174 |

| Inter- and subtroch. vs. femoral neck f | 2.729 | 1.675 | 4.445 | <0.001 | 1.187 | 0.803 | 1.754 | 0.710 |

| Arthroplasty vs. osteosynthesis | 1.258 | 0.865 | 1.828 | 0.230 | 0.890 | 0.697 | 1.136 | 0.351 |

| Age (y) | 1.072 | 1.061 | 1.084 | <0.001 | 1.037 | 1.029 | 1.045 | <0.001 |

| Gender (female vs. male) | 0.519 | 0.418 | 0.644 | <0.001 | 0.646 | 0.556 | 0.751 | <0.001 |

| CCI (≥3 vs. <3) | 2.088 | 1.339 | 3.256 | 0.001 | 1.574 | 1.372 | 1.806 | <0.001 |

| In-hospital complications (yes vs. no) | 1.433 | 1.161 | 1.769 | <0.001 | 1.133 | 0.984 | 1.305 | 0.083 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 1.014 | 1.002 | 1.026 | 0.022 | 1.004 | 0.997 | 1.011 | 0.292 |

| Study | Design | Facility | Inclusion Criteria | n | Demographics | Covariates in Multivariable Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kristiansson et al. [9] 2020 | Retrospective | Tertiary hospital | Age ≥ 60 y | 9270 | Mean age, 82.6 y 30-day mortality rate, 7.6% | Age, gender, type of surgery |

| Öztürk et al. [10] 2019 | Retrospective | Data base | Age > 65 y | 36,552 | Age, gender, BMI, type of fracture and surgery, housing condition, marital status, CCI, drug use, anticoagulation | |

| Hongisto et al. [11] 2019 | Prospective | Central hospital | Age ≥ 65 y ASA ≥ 3 | 724 | Mean age, 84.1 y one-year mortality rate, 9.1% | Age, gender, previous living arrangements, polypharmacy, type of fracture |

| Leer-Salvesen et al. [12] 2019 | Retrospective | Data base | Age ≥ 50 y | 38,754 | Mean age, 81.5 y | Age, gender, ASA, type of fracture, and surgery |

| Iida et al. [13] 2024 | Retrospective | Age > 60 y Low-energy trauma | 389 | Mean age, 84.1 y one-year mortality rate, 10% | ||

| Kristan et al. [14] 2021 | Retrospective | Tertiary hospital | 641 | Median age, 82 y; 2% younger than 40 y 30-day mortality rate, 5.1%; one-year mortality rate, 18.4% | Age, ASA, preinjury residence, surgery type, anticoagulation | |

| Huette et al. [15] 2020 | Prospective | Tertiary hospital | Age ≥ 65 y | 309 | Median age, 85 y one-year mortality rate, 23.9% | Age, ASA, BMI, prefracture status, type of surgery |

| Chen et al. 2019 [16] | Retrospective | Tertiary hospital | Age > 65 y fragility fractures | 313 | One-year mortality rate, 10.9% | |

| Lund et al. [17] 2014 | Retrospective | Data base | Age > 65 y | 6143 | 62.2% older than 80 y one-year mortality rate, 30.0% | |

| Smektala et al. [18] 2008 | Prospective | 268 acute care hospitals | Age ≥ 65 y | 2916 | Median age, 82 y one-year mortality rate, 19.7% | Age, gender, ASA, BMI, malignancy, kidney dysfunction, COPD, postoperative complications |

| Gdalevich et al. [19] 2004 | Retrospective | Regional hospital | Age ≥ 60 y | 651 | 49.6% aged 80 y or older one-year mortality rate, 18.9% | Age, gender, ASA, postoperative complications, post-injury mental deterioration |

| Åhman et al. [20] 2018 | Retrospective | Data base | Age ≥ 18 y | 14,942 | Median age, 83 y 30-day mortality rate, 8.2%; one-year mortality rate, 23.6% | Age, gender, ASA, type, period, and duration of surgery, ICU admission, type of anesthesia |

| Greve et al. [21] 2020 | Retrospective | Data base | Age ≥ 65 y | 59,675 | Mean age, 83 y 30-day mortality rate, 8% | Age, ASA, type of fracture, and surgery |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Negrin, L.L.; Christian, T.; Kalus, S.; Kiss, G.; Ristl, R.; Hajdu, S. Factors Affecting Mortality Following Hip Fracture Surgery: Insights from a Long-Term Study at a Level I Trauma Center—Does Timing Matter? J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8104. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228104

Negrin LL, Christian T, Kalus S, Kiss G, Ristl R, Hajdu S. Factors Affecting Mortality Following Hip Fracture Surgery: Insights from a Long-Term Study at a Level I Trauma Center—Does Timing Matter? Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(22):8104. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228104

Chicago/Turabian StyleNegrin, Lukas L., Thomas Christian, Sandra Kalus, Gyula Kiss, Robin Ristl, and Stefan Hajdu. 2025. "Factors Affecting Mortality Following Hip Fracture Surgery: Insights from a Long-Term Study at a Level I Trauma Center—Does Timing Matter?" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 22: 8104. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228104

APA StyleNegrin, L. L., Christian, T., Kalus, S., Kiss, G., Ristl, R., & Hajdu, S. (2025). Factors Affecting Mortality Following Hip Fracture Surgery: Insights from a Long-Term Study at a Level I Trauma Center—Does Timing Matter? Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(22), 8104. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14228104