Abstract

Background/Objectives: Asthma is a condition caused by chronic lower airway inflammation. Its primary treatment focuses on managing the condition and reducing the frequency of exacerbation episodes. Monitoring the level of asthma control among adults is essential for both clinical care and public health planning. This systematic review aimed to assess the level of asthma control among adults in Saudi Arabia and to determine the prevalence of controlled asthma in this population. Methods: The literature search was conducted using PubMed. We included all English-language, empirical, quantitative studies that investigated the prevalence of asthma control among Saudi adults. National Institutes of Health (NIH) Study Quality Assessment Tools guided determination of the quality of the included studies. This review is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024484711). Results: Of the 107 initially identified studies, 17 met the inclusion criteria. Quality assessment tool rated 11 studies as good, 5 as fair, and 1 as poor. Most of the included studies used cross-sectional design from different geographical locations and varied in sample size. Overall, the prevalence of uncontrolled asthma among Saudi adults ranged from 23.4% to 68.1%. In some studies, well-controlled asthma was reported in as few as 3% of patients. Factors associated with uncontrolled asthma included lower educational attainment, unemployment, low income, female gender, tobacco use, poor medication adherence, and lack of regular medical follow-up. Environmental triggers and comorbid conditions, such as allergic rhinitis, were also frequently cited as contributing factors. Conclusions: Asthma control among adults in Saudi Arabia remains a significant public health concern. Improving outcomes requires a multifaceted approach that includes patient education, regular follow-up care (including pulmonary function tests, asthma severity assessments, and personalized treatment plans), and broader public health initiatives aimed at reducing exposure to allergens and pollutants. Strengthening primary care services and implementing nationwide asthma management programs may play a critical role in enhancing disease control and improving quality of life. Continued research in this field is strongly recommended.

1. Background

Asthma is a chronic respiratory condition characterized by inflammation of the lower airways, resulting in symptoms such as shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, and airway obstruction [1,2]. While it was traditionally considered a single disease with a standardized treatment approach, asthma is now recognized as a complex and heterogeneous disorder with various phenotypes and underlying mechanisms [2]. The Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) has identified distinct phenotypes based on demographic, clinical, and pathophysiological characteristics. These include allergic asthma, non-allergic asthma, late-onset asthma, asthma with fixed airflow limitation, and asthma associated with obesity [2]. Identifying these phenotypes is critical for guiding targeted therapies and achieving better asthma control. However, there is still limited understanding of how these phenotypes relate to disease progression and treatment response [2]. Various factors contribute to the development and exacerbation of asthma, including respiratory infections, cold air, allergens, genetic predispositions, obesity, and exposure to tobacco smoke [2]. The immune response—mediated by multiple cell types such as macrophages, mast cells, eosinophils, neutrophils, T lymphocytes, and epithelial cells—plays a central role in the airway inflammation characteristic of asthma [3]. Asthma can be broadly classified into allergic and non-allergic subtypes, with the presence of IgE antibodies typically indicating allergic asthma [3]. The prevalence of asthma varies widely across countries due to environmental exposures, as well as differences in measurement tools and epidemiological definitions. Several studies have assessed the prevalence of asthma and asthma-related symptoms among adults in Saudi Arabia. For example, Al Ghobain et al. conducted a study in Riyadh using the European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS) questionnaire to evaluate asthma prevalence [4]. The study found that 18.2% of participants reported wheezing or chest whistling in the past 12 months, with no significant gender differences. Asthma diagnosed by a physician was reported by 11.3% of participants, and 10.6% were actively taking asthma treatment at the time of the survey. The study also reported a 33.3% prevalence of nasal allergic reactions. Common asthma symptoms included morning chest tightness (33%), dyspnea (31%), coughing fits (43%), and recent asthma episodes (5.6%) [4]. Another study by Moradi Lakeh et al. aimed to estimate the national prevalence of asthma in Saudi Arabia using a random sampling technique [5]. The study found an estimated asthma prevalence of 4.05% among individuals aged 15 years and older, highlighting a substantial number of Saudis living with the condition. Uncontrolled asthma significantly impairs patients’ quality of life and underscores the need for effective management and strategies to prevent exacerbations [6]. Providing patients with adequate education and guidance on asthma self-management can empower them to manage mild symptoms at home and reduce the frequency of daytime asthma attacks [7]. However, studies have shown that a significant proportion of individuals in Saudi Arabia have uncontrolled asthma, with only a small percentage successfully managing their condition [6]. This alarming discrepancy highlights the urgent need for improved asthma management and control strategies across the country. Limited research and small sample sizes have contributed to the lack of comprehensive data on asthma control in the Middle East, specifically in Saudi Arabia [8]. Asthma affects not only physical health but also broader aspects of daily life, leading to missed school and workdays, hospitalizations, emergency department visits, and increased financial burden [2]. Moreover, individuals with asthma often face ongoing challenges, including morning symptoms, muscle soreness, and persistent anxiety [9,10,11].

This study aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the prevalence of controlled asthma among adults in Saudi Arabia. By examining the impact of asthma on daily activities and health-related outcomes, this study provides a valuable reference for researchers, respiratory therapists, pulmonologists, and other healthcare providers engaged in asthma care and health policy development.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

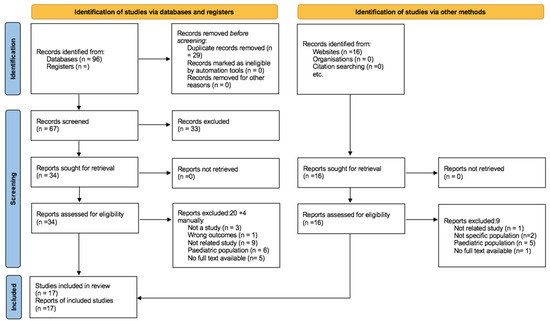

This systematic review was carried out following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA). This review examined the prevalence of asthma control among adults in Saudi Arabia. The study protocol was registered with PROSPERO (registration number: CRD42024484711) (see Supplementary Materials, Figure S1, for more details).

2.2. Data Source

The literature search was conducted using PubMed (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accessed on 15 March 2024). We included all English-language, empirical quantitative studies that investigated the prevalence of asthma control among Saudi adults. The quality of the identified studies was assessed using the NIH Study Quality Assessment Tools (https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools, accessed on 15 March 2024).

2.3. Study Selection

Data were collected from relevant databases by four reviewers (D.A., A.A., F.A., and N.A.) using PubMed. Each reviewer independently screened all titles and abstracts based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Full-text articles were then reviewed, and any disagreements were resolved by a fifth reviewer (M.A.).

2.4. Inclusion Criteria

In this systematic review, we included observational or intervention studies in which the study population consisted of adults aged 18 years and older with asthma. Asthma diagnosis in the included studies was based either on self-reported responses—where participants were asked whether they had ever been diagnosed with asthma—or on a confirmed clinical diagnosis by a physician. Additionally, studies that reported asthma-related respiratory symptoms such as breathlessness, dyspnea, breathing difficulties, wheezing, coughing, sputum production, and phlegm were also included (see Table 1 for more details).

Table 1.

Summary of Included Studies on Asthma Control Among Adults in Saudi Arabia.

2.5. Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review excluded publications that involved animal studies or did not report on adult asthma patients or asthma-related respiratory symptoms. Furthermore, any published systematic reviews (but screened the reference lists), non-English, manuscripts, non-Saudi Arabia research, conference abstracts with no full-text and non-full text articles were also excluded from the study (see Figure 1 for more details).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart for searches of databases, registers, and other sources.

2.6. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

In each included study, data extraction for all relevant outcomes was conducted independently by four reviewers (XX, YY, XY, and YX). These reviewers also gathered details on study characteristics, including the research design (e.g., interventional, cross-sectional, observational, or experimental), characteristics of the study population, participant age, and methods used to assess asthma control. Risk of bias (ROB) was evaluated independently by three reviewers (XX, YY, and XY) at both the study and outcome levels using the NIH Study Quality Assessment Tools. Studies were classified as having low risk of bias if they provided a thorough assessment and implemented appropriate adjustments for study-related factors (refer to Supplementary Materials, Table S1, for additional details).

3. Results

3.1. Quality Assessment and Risk of Bias

The included studies employed a variety of designs, including cross-sectional and randomized controlled trials, and incorporated both qualitative and quantitative research methodologies (see Table 2). Each study was evaluated using standardized quality assessment tools, specifically the NIH Quality Assessment Tool. Based on these assessments, 14 studies were rated as fair, 8 as good, and 2 as poor (see Supplementary Materials, Table S1, for more details).

Table 2.

Prevalence of Asthma Control and Associated Factors Reported in Included Studies.

3.2. Study Selection and Characteristics

Out of 94 eligible studies, only 17 met the inclusion criteria. Of these, nine were conducted in Riyadh, one in the Aseer Region, one in Jeddah, one in Najran, one in Al-Baha, and two in other Middle Eastern countries. Additionally, one study was conducted across both Jazan and Jeddah.

Among the 17 studies reviewed for the systematic review, 2 studies had sample sizes of fewer than 100 participants, 11 studies had sample sizes ranging from 100 to just under 1000 participants, and 4 studies involved sample sizes exceeding 1000 participants. The smallest study sample size was 53 [23], and it was 7955 in the largest study [17] (Figure 1).

3.3. Prevalence of Asthma Control

Among the 17 included studies, asthma control was most commonly assessed using the Arabic version of the Asthma Control Test (ACT) (n = 10 [6,12,14,15,16,19,21,22,23,26]), followed by the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines (n = 3 [8,24,25]), Mini Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (MiniAQLQ) (n = 1 [20]), objective clinical measures such as FeNO and spirometry in conjunction with ACT (n = 1 [23]), and modified ISAAC or Global Asthma Network (GAN)-based symptom questionnaires (n = 3 [13,17,18]). Asthma control among Saudi adults was found to be suboptimal in most of the studies. The prevalence of uncontrolled asthma was reported in six studies and ranged from 23.4% to 68.1% [6,12,14,15,25,27]. The prevalence of asthma control varied significantly across different studies conducted in Saudi Arabia. According to Ahmed A.E. (2014), the average asthma control score was 17.5 (±3.8), with control levels influenced by factors such as the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs), consistency in follow-up, and education about asthma [12]. Alanazi et al. (2021) reported that among 200 asthma patients, 33.5% had well-controlled asthma, 27.5% had partially controlled asthma, and 39% had uncontrolled asthma [27]. In a study by Al-Jahdali et al. (2008) involving 1060 participants, 64% had uncontrolled asthma, 31% had well-controlled asthma, and 5% had completely controlled asthma [14]. Another study by Al-Jahdali et al. (2012) found that 23.4% of participants had uncontrolled asthma, 74.4% had partially controlled asthma, and 1.8% had completely controlled asthma [15]. BinSaeed (2015) observed that 68.1% of 260 patients had uncontrolled asthma [6]. Similarly, Tayeb et al. (2017) reported that 63% of their study population had uncontrolled asthma, 34% had partially controlled asthma, and only 3% had well-controlled asthma [25] (see Table 1 for more details).

3.4. Impact of Uncontrolled Asthma on Daily Life and Health-Related Outcomes

For the included studies, we found that asthma has a significant impact on the daily lives of Saudi adults, as evidenced by various studies uncontrolled asthma can be linked to education, employment status, income level, gender, age, regional, environmental factors, tobacco use, hospitalization, quality of life, adherence to medications, and asthma symptoms or exacerbations [12,19,20] (see Table 2 for more details).

- Education

Education relating to controlling asthma symptoms was discussed in seven studies [8,12,14,15,16,19,21]. Ahmed A.E. (2014) highlighted that asthma control scores varied significantly with the severity of asthma, emphasizing the importance of education about asthma medication and disease. Specifically, participants who received education about asthma medication had slightly better control scores (17.7 ± 3.6) compared to those who did not (17.4 ± 3.9) [12]. Similarly, those who received education about asthma disease or have higher education degree had control scores 3.1 times (OR 3.1) higher compared to those who did not [12,21]. Al-Jahdali et al. also emphasized that higher education levels and regular follow-up with clinics were crucial for better asthma control [8,14,15,16]. For instance, in a 2012 study, regular ICS use was associated with better control (80.6% vs. 72.4%), and follow-up with clinics showed better control (77.8% vs. 75.1%). Poor asthma control was often linked to improper use of inhalers and a lack of education, with 45% of participants in a 2013 study using inhaler devices improperly [16]. Additionally, Al-Zahrani J.M. et al. (2015) reported that uncontrolled asthma was more prevalent among individuals with lower education levels and those who were unemployed. For instance, 39.8% of patients had uncontrolled asthma, with improper device use being more frequent among those with uncontrolled asthma (64.2% vs. 35.8%) [19].

- Employment status

With regards to employment status, two studies found that unemployment is associated with higher rates of uncontrolled asthma [19,21]. Al-Zahrani J.M. et al. (2015) reported 39.8% of unemployed patients had uncontrolled asthma, while Alzayer et al. (2022) highlighted that unemployed, disabled, or ill patients had higher odds (OR 3.1) of uncontrolled asthma [19,21].

- Income level

Torchyan et al. (2017) found that a higher monthly household income was associated with better asthma-related quality of life (AQL), with a monthly income of SAR 25,000 or more linked to improved AQL among men [26]. Al-Jahdali et al. (2019) reported that patients without medical insurance coverage were more likely to have controlled asthma, highlighting the crucial role of access to healthcare resources, which can be influenced by income level, in asthma control [8].

- Gender differences

Based on the included studies, there are notable gender differences in asthma control in six studies [8,13,14,17,20,26]. Al-Ghamdi et al. (2019) reported that in the Aseer Region, the prevalence of wheezing in the past 12 months was higher in females (21.5%) compared to males (18.3%) [13]. Al-Jahdali et al. (2008) found that uncontrolled asthma was prevalent among both genders, but the data did not specify a significant difference between males and females [14]. However, Al-Jahdali et al. (2019) highlighted that a higher level of asthma control was reported among male patients compared to females, with the mean Asthma Control Test (ACT) score being 17.1 (±4.6) for the overall population [8]. Torchyan et al. (2017) found no statistically significant difference in asthma-related quality of life (AQL) between males and females, with mean AQL scores of 4.3 (SD = 1.5) for males and 4.0 (SD = 1.3) for females (p = 0.113) [26]. Alomary et al. (2022) indicated that 56.9% of the participants were males, but did not provide specific data on gender differences in asthma control [17]. Similarly, Alzahrani et al. (2024) involved 151 patients, with 23.8% males and 76.2% females, but did not specify gender differences in asthma control, noting instead that most participants did not smoke [20].

- Age and regional variation

Five studies highlight age-related variations in asthma control across different studies in Saudi Arabia. Al-Jahdali et al. (2008) [14] conducted a study in Riyadh and found that younger age groups had better asthma control compared to older age groups. Specifically, the prevalence of uncontrolled asthma was lower in participants under 20 years old (50%) compared to those aged 20–39 (66%), 40–60 (66%), and over 60 (65%). However, other studies reported that age did not significantly affect asthma control, with similar rates of uncontrolled asthma across different age groups [8,15,23,25].

- Environmental factors

Two of the included studies revealed that environmental and lifestyle factors also play a crucial role in asthma management. Al-Ghamdi et al. (2019) indicated that exposure to both outdoor and indoor aeroallergens, such as ragweed and dust mites, was higher among asthmatics [13]. For example, 24.5% of asthmatics had positive specific IgE antibodies to ragweed compared to 20.5% of non-asthmatics [13]. Additionally, living near heavy traffic, having pets, and using analgesics were identified as significant risk factors for asthma. The study found that living near heavy truck traffic increased the risk of asthma (aOR = 1.67), and having cats in the house was also a significant factor (aOR = 2.27) [13]. Alomary et al. (2022) [17] further supported these findings, showing that tobacco use, exposure to moisture, and heating the house were associated with increased wheezing and asthma symptoms. Specifically, daily tobacco use was associated with wheezing (aOR 2.7) [17].

- Tobacco Use

The relationship between tobacco use and asthma control has been discussed in five included studies, revealing significant associations between smoking and poor asthma outcomes. Al-Jahdali et al. (2012) found that active smoking was strongly linked to uncontrolled asthma, with 52.2% of active smokers experiencing uncontrolled asthma compared to 47.8% of non-smokers [15]. Similarly, Alomary et al. (2022) indicated that daily tobacco use was significantly associated with wheezing, with an adjusted odds ratio (aOR) of 2.7 (95% CI: 2.0–3.5), highlighting the impact of smoking on respiratory health [17]. BinSaeed (2015) further demonstrated that daily tobacco smokers had a higher prevalence of uncontrolled asthma (85%) compared to those who smoked less frequently or not at all (67.2%) [6]. Additionally, Torchyan et al. (2017) found that daily tobacco smoking among males was associated with a decrease in asthma-related quality of life (AQL) by 0.72 points (95% CI: −1.30 to −0.14) [26]. Women who had a household member smoking inside the house also had a significantly lower AQL (B = −0.59, 95% CI: −1.0 to −0.19) [26]. However, Al-Jahdali et al. (2019) reported no significant difference in asthma control levels between non-smokers, active smokers, and past smokers (p = 0.824), suggesting that other factors may also play a role in asthma management [8].

- Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalizations

Four included studies underscored the relationship between uncontrolled asthma and healthcare utilization, particularly in terms of emergency department (ED) visits and hospitalizations. Ahmed A.E. (2014) found a strong association between frequent ED visits and poor asthma control, with participants experiencing poor asthma control requiring more frequent doctor and hospital visits [12]. Specifically, the study reported that patients with fewer than three ED visits had an average asthma control score of 18.0 (±3.6), while those with three or more ED visits had a lower average score of 16.6 (±3.6) [12]. Similarly, Al-Jahdali et al. (2012) reported that patients with uncontrolled asthma had more frequent ED visits compared to those with controlled asthma [15]. Additionally, Al-Jahdali et al. (2013) linked uncontrolled asthma to higher rates of hospitalizations due to asthma exacerbations [16]. Tarrafa H et al. (2018) further supported these findings, noting that frequent nighttime symptoms and exacerbations affecting daily activities and sleep were prevalent among patients with uncontrolled asthma, leading to increased hospital admissions [24].

- Quality of Life

The quality of life (QoL) and psychological well-being of asthma patients were discussed in four included studies. Torchyan et al. (2017) demonstrated that uncontrolled asthma is associated with a lower asthma-related quality of life (AQL), with daily tobacco smoking among males decreasing AQL by 0.72 points (95% CI: −1.30 to −0.14) [26]. This study also found that women who had a household member smoking inside the house experienced a significantly lower AQL (B = −0.59, 95% CI: −1.0 to −0.19), indicating the broader impact of second-hand smoke on asthma patients [26]. Al-Jahdali et al. (2019) corroborated these findings, showing that patients with controlled asthma had better QoL according to the SF-8 questionnaire [8]. Furthermore, Alzahrani et al. (2024) linked uncontrolled asthma to higher levels of frustration and fear of not having asthma medication, with 12% of patients feeling afraid all the time and 13% feeling frustrated some of the time [20]. Alzayer et al. (2022) found that poorly controlled asthma was associated with lower scores on the Asthma Control Test (ACT), indicating a negative impact on mental health [21].

- Adherence to Medication

Adherence to medication including follow-up with healthcare providers, particularly inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs), was reported in three included studies. Al-Jahdali et al. (2012) demonstrated that regular use of ICSs was associated with better asthma control, with 80.6% of patients who regularly used ICSs having partially or fully controlled asthma compared to 72.4% of those who did not use ICSs regularly [15]. Al-Jahdali et al. (2013) also highlighted the impact of improper use of inhaler devices on asthma control, linking it to higher rates of uncontrolled asthma, with 45% of patients using inhaler devices improperly [16]. Regular follow-up with healthcare providers is another critical factor, as Ahmed AE (2014) found that patients who consistently followed up with their doctors had better asthma control, with an average asthma control score of 17.4 (±3.4) for those who followed up regularly compared to 17.8 (±4.2) for those who did not [1]. Al-Jahdali et al. (2012) supported this finding, showing that patients who regularly attended clinic visits had better asthma control compared to those who did not [15].

- Asthma symptoms

Only one study, by Ghaleb Dailah (2021), provided insights into asthma control levels and symptom frequency among the participants. The study found that the majority of the control group had somewhat controlled asthma (38.1%), while completely controlled asthma was observed in 23.8% of the control group. Additionally, poorly controlled asthma was present in 11.1% of the participants. The study also highlighted the frequency of asthma symptoms, with 27% of participants experiencing symptoms such as wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness or pain once or twice a week. Furthermore, 31.7% of the participants reported using rescue inhalers or nebulizers (such as albuterol) two or three times per week. These findings underscore the varying levels of asthma control among the participants and the regular occurrence of asthma symptoms and medication use [22]. Symptoms reviewed in the included studies cough [22], wheezing [13,17,22], shortness of breath [20,22,25], sleep disturbance or sleep quality [15,20,24], and limited daily activities [24,25].

- Meta-analysis

The meta-analysis revealed an overall odds ratio of 1.23 (95% CI: 0.98–1.54), suggesting a slight but statistically non-significant association between asthma control status and the examined factors. The unadjusted analysis yielded a broader range with an odds ratio of 0.11 (95% CI: 0.07–6.58), indicating high variability across studies (refer to Supplementary Materials, pooled analysis for the meta, for additional details).

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review is to comprehensively assess the literature on the significant burden of uncontrolled asthma among the Saudi Arabian population, with particular attention to contributing factors such as education level, environmental exposure, and treatment adherence. This review seeks to deepen the understanding of studies that examine factors and conditions influencing asthma control and management. Specifically, it focuses on the prevalence and impact of uncontrolled asthma, as well as key determinants that affect disease control. Investigating the prevalence of uncontrolled asthma in Saudi Arabia and identifying its contributing factors is essential for developing effective management strategies and improving patient outcomes. In particular, understanding the role of socioeconomic and environmental influences is critical for shaping public health policies aimed at reducing disparities in asthma prevalence and outcomes across regions of the Kingdom. Furthermore, examining these factors promotes a comprehensive approach to asthma management that extends beyond pharmacological treatment. It encourages healthcare systems to consider the broader context of patients’ lives, including education level, living conditions, and social support networks—elements that ultimately contribute to better quality of life and improved asthma outcomes. Overall, our findings underscore the urgent need for targeted interventions, including patient education, improved access to inhaled corticosteroids (ICSs), and strategies to reduce environmental triggers, in order to enhance asthma control and optimize patient care in Saudi Arabia.

Understanding the prevalence of asthma control is essential as it reflects the effectiveness of current management strategies and highlights variations in outcomes across different patient demographics [28,29]. This, in turn, can inform public health initiatives and guide resource allocation to optimize disease control. Analysis of the six studies reporting asthma symptom prevalence in Saudi Arabia reveals that approximately 68% of patients with asthma experience uncontrolled symptoms across the Kingdom. Moreover, our review finds that poor asthma control significantly impairs patients’ daily functioning.

The included studies consistently demonstrate a negative association between asthma control and factors such as education level, employment status, gender, age, medication adherence, tobacco use, quality of life, and frequency of emergency visits. In contrast, a positive correlation is observed between medication adherence and improved asthma symptom control. These findings align with previous research indicating that poor asthma control adversely impacts patient well-being, leading to more frequent exacerbations, increased healthcare utilization, and reduced quality of life [30]. Additionally, a study by Backman et al. (2019) showed that inadequate asthma control can worsen health disparities and impose substantial economic burdens on affected populations [31]. Overall, these findings underscore the urgent need to improve asthma management in Saudi Arabia to mitigate these outcomes and enhance patient care.

Our study suggests that awareness of asthma, level of education, employment status, and income level are all associated with the prevalence of asthma control in Saudi Arabia. A study by Nguyen et al. (2018) found that patients with higher education levels demonstrate better understanding of asthma management and experience improved disease outcomes, whereas patients with lower educational attainment face difficulties comprehending information provided by healthcare professionals [32]. Furthermore, enhancing patient awareness of asthma and its medications has been shown to improve medication adherence by 80%, leading to reduced emergency department visits and hospital admissions [16,33]. Additional studies have also shown that patients with stable employment status tend to have better asthma control [34]. Similarly, our findings indicate that patients with higher education levels, stable employment, and greater knowledge about asthma achieve better outcomes than their counterparts. These findings underscore the importance of asthma education, which can be effectively delivered through asthma clinics. Such clinics can play a critical role in improving patients’ knowledge and equipping them with essential self-management skills, ultimately leading to improved asthma control. Addressing disparities in health education may also promote better asthma outcomes and contribute to broader public health improvements, including enhanced job stability, increased income, and improved overall quality of life [35].

Our systematic review demonstrates that patients with uncontrolled asthma symptoms in Saudi Arabia experience lower asthma-related quality of life (QoL). The impact of daily tobacco smoking and passive smoke exposure on asthma control was inconclusive: two studies reported that both active and passive smoking negatively affected asthma-related quality of life (AQL), while another study found no significant association. These findings are consistent with previous research showing that active smokers with asthma experience higher rates of exacerbation and significantly poorer asthma-related quality of life compared to non-smokers [36]. Similarly, Mroczek et al. (2015) reported that low asthma control is associated with increased treatment costs and reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL) [37]. Overall, these results emphasize the importance of effective asthma management strategies and the implementation of smoking cessation programs to improve patient outcomes and reduce the burden of disease.

The management and prevalence of asthma symptoms and exacerbations are influenced by multiple factors, including gender, age, environmental exposures, and regional variations [38,39,40,41,42]. Gender in particular plays a significant role in asthma prevalence. A study by Almqvist et al. (2008) reported that asthma is more prevalent in boys than girls during childhood, while the trend reverses during adolescence, with women exhibiting higher rates than men [38]. Similarly, our review identified notable gender differences, with asthma being more frequently reported among women. Moreover, the analysis indicated that men with asthma generally had better symptom control compared to women.

Environmental and regional factors also significantly affect asthma symptoms and the frequency of exacerbations [43,44]. Studies have shown that patients living near factories, in areas with poor air quality, or in agricultural regions, as well as those with high exposure to dust mites, mold, or pollen are more likely to experience asthma exacerbations and have lower levels of asthma control [45,46]. These findings are consistent with our review, which notes associations between increased exposure to environmental triggers—such as ragweed, moisture, dust mites, and heavy traffic—and a higher prevalence of symptoms like wheezing. These results underscore the importance of evaluating a wide range of contributing factors when designing asthma management strategies. Enhancing patient awareness of environmental triggers and expanding clinical support services—particularly in regions with high exposure to such triggers—can play a vital role in improving asthma care in Saudi Arabia. Furthermore, implementing routine asthma screenings in educational institutions may improve early identification and long-term disease control, ultimately enhancing patient outcomes.

Adherence to medication, asthma symptoms, and emergency department (ED) visits have been widely associated with asthma severity and patients’ quality of life [47,48,49,50,51]. Our review finds that asthma control is positively influenced by adherence to medication and negatively affected by frequent symptoms and ED visits. Specifically, patients who adhere to inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) therapy and attend regular follow-ups demonstrate better asthma outcomes. Additionally, our findings show that patients who experience asthma symptoms more than 2–3 times per week and rely on rescue inhalers more than twice per week often report limited daily activity and sleep disturbances. Furthermore, poor asthma control is associated with increased rates of ED visits and hospital admissions. Our review also indicates that patients with uncontrolled asthma have lower scores on both the Asthma Quality of Life Questionnaire (AQLQ) and the Asthma Control Test (ACT), alongside reported emotional burdens such as frustration and fear related to medication availability. These findings highlight the critical importance of effective asthma management, which can be supported through routine assessments such as pulmonary function tests (PFTs) and blood tests to evaluate asthma severity. Increasing patient awareness of medication usage and ensuring access to asthma therapies are essential steps toward reducing exacerbation frequency, improving quality of life, and lowering overall healthcare costs.

5. Limitations

This systematic review provides valuable insights into asthma control among residents of Saudi Arabia; however, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, there was considerable heterogeneity in the study samples, methodologies, and reported outcomes across the included studies, which may affect the comparability of findings. Second, this review did not include adolescent populations—a demographic that may exhibit different patterns or disparities in asthma control outcomes. Despite these limitations, this systematic review makes a meaningful contribution to the growing body of knowledge on the prevalence and determinants of asthma control in Saudi Arabia.

6. Conclusions

Asthma control among adults in Saudi Arabia remains a significant public health concern. Despite the availability of effective treatment options and national clinical guidelines, many patients continue to experience poor disease control due to factors such as limited awareness, medication non-adherence, socioeconomic status, employment conditions, age, and environmental triggers. Improving asthma outcomes requires a multifaceted approach that includes patient education, regular follow-up visits (including pulmonary function tests [PFTs] and asthma severity assessments), individualized treatment plans, and broader public health initiatives aimed at reducing exposure to allergens and pollutants. Strengthening primary care services and implementing nationwide asthma management programs can play a critical role in enhancing disease control and improving quality of life for adults living with asthma in Saudi Arabia. Additionally, further research is recommended to better understand the factors influencing asthma control and to inform evidence-based interventions tailored to the Saudi context [52].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm14165753/s1, Figure S1: Asthma control in Saudi Arabia. Table S1: Summary of included studies in the meta-analysis, Calculation of Odd ratio by Sample size. PRISMA 2020 Checklist. Reference [52] is cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

M.M.A. (Mohammed M. Alqahtani) and H.A.-J. conceived and designed the study. Methodology development and protocol planning were conducted by M.M.A. (Mansour M. Alotaibi), S.M.A., M.M.A. (Mansour M. Alotaibi), and A.A. Literature search and data extraction were performed by J.H., F.A., N.A., D.F.A., and A.A.A. Quality assessment of included studies was completed by S.M.A., N.A., and D.F.A. Data analysis and interpretation were carried out by M.M.A. (Mansour M. Alotaibi), M.M.A. (Mansour M. Alotaibi), and S.M.A. The initial draft of the manuscript was written by M.M.A. (Mansour M. Alotaibi), J.H., and D.F.A. All authors, including H.A.-J., F.A., N.A., A.A., and A.A.A., contributed to the critical review and editing of the manuscript. Supervision and overall project oversight were provided by H.A.-J. and M.M.A. (Mansour M. Alotaibi), with administrative coordination supported by M.M.A. (Mansour M. Alotaibi) and H.A.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA through the project number NBU-FFR-2025-2508-03. The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Northern Border University, Arar, KSA for funding this research work.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mims, J.W. Asthma: Definitions and pathophysiology. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015, 5, S2–S6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gans, M.D.; Gavrilova, T. Understanding the immunology of asthma: Pathophysiology, biomarkers, and treatments for asthma endotypes. Paediatr. Respir. Rev. 2020, 36, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslan, J.; Mims, J.W. What is asthma? Pathophysiology, demographics, and health care costs. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2014, 47, 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ghobain, M.O.; Algazlan, S.S.; Oreibi, T.M. Asthma prevalence among adults in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2018, 39, 179–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi-Lakeh, M.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Daoud, F.; Tuffaha, M.; Kravitz, H.; Al Saeedi, M.; Basulaiman, M.; Memish, Z.A.; Al Mazroa, M.A.; Al Rabeeah, A.A.; et al. Prevalence of asthma in Saudi adults: Findings from a National Household Survey, 2013. BMC Pulm. Med. 2015, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BinSaeed, A.A. Asthma control among adults in Saudi Arabia: Study of determinants. Saudi Med. J. 2015, 36, 599–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zalabani, A.H.; Almotairy, M.M. Asthma control and its association with knowledge of caregivers among children with asthma: A cross-sectional study. Saudi Med. J. 2020, 41, 733–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AL-Jahdali, H.; Wali, S.; Salem, G.; Al-Hameed, F.; Almotair, A.; Zeitouni, M.; Aref, H.; Nadama, R.; Algethami, M.M.; Al Ghamdy, A.; et al. Asthma control and predictive factors among adults in Saudi Arabia: Results from the Epidemiological Study on the Management of Asthma in Asthmatic Middle East Adult Population study. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2019, 14, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Emotional Effects of Asthma. Available online: https://www.uillinois.edu/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Meal Planning and Eating. Available online: https://www.mylungsmylife.org/ (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- Kharaba, Z.; Feghali, E.; El Husseini, F.; Sacre, H.; Abou Selwan, C.; Saadeh, S.; Hallit, S.; Jirjees, F.; AlObaidi, H.; Salameh, P.; et al. An assessment of quality of life in patients with asthma through physical, emotional, social, and occupational aspects. A cross-sectional study. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 883784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, A.E.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Al-Harbi, A.; Khan, M.; Ali, Y.; Al Shimemeri, A.; Al-Muhsen, S.; Halwani, R. Factors associated with poor asthma control among asthmatic patient visiting emergency department. Clin. Respir. J. 2014, 8, 431–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ghamdi, B.R.; Koshak, E.A.; Omer, F.M.; Awadalla, N.J.; Mahfouz, A.A.; Ageely, H.M. Immunological factors associated with adult asthma in the Aseer Region, Southwestern Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jahdali, H.H.; Al-Hajjaj, M.S.; Alanezi, M.O.; O Zeitoni, M.; Al-Tasan, T.H. Asthma control assessment using asthma control test among patients attending 5 tertiary care hospitals in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med. J. 2008, 29, 714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Al-Jahdali, H.; Anwar, A.; Al-Harbi, A.; Baharoon, S.; Halwani, R.; Al Shimemeri, A.; Al-Muhsen, S. Factors associated with patient visits to the emergency department for asthma therapy. BMC Pulm. Med. 2012, 12, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Jahdali, H.; Ahmed, A.; Al-Harbi, A.; Khan, M.; Baharoon, S.; Bin Salih, S.; Halwani, R.; Al-Muhsen, S. Improper inhaler technique is associated with poor asthma control and frequent emergency department visits. Allergy Asthma Clin. Immunol. 2013, 9, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomary, S.A.; Al Madani, A.J.; Althagafi, W.A.; Adam, I.F.; Elsherif, O.E.; Al-Abdullaah, A.A.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Jokhdar, H.A.; Alqahtani, S.H.; Nahhas, M.A.; et al. Prevalence of asthma symptoms and associated risk factors among adults in Saudi Arabia: A national survey from Global Asthma Network Phase I. World Allergy Organ. J. 2022, 15, 100623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, J.M. Atopy and allergic diseases among Saudi young adults: A cross-sectional study. J. Int. Med. Res. 2020, 48, 300060519899760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Zahrani, J.M.; Ahmad, A.; Abdullah, A.-H.; Khan, A.M.; Al-Bader, B.; Baharoon, S.; Shememeri, A.; Al-Jahdali, H. Factors associated with poor asthma control in the outpatient clinic setting. Ann. Thorac. Med. 2015, 10, 100–104. [Google Scholar]

- Alzahrani, S.J.M.; Alzahrani, H.A.K.; Alghamdi, S.M.M.; A Alzahrani, A.N. Health-Related Quality of Life of Asthmatic Patients in Al-Baha City, Saudi Arabia. Cureus 2024, 16, e53601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzayer, R.; Almansour, H.A.; Basheti, I.; Chaar, B.; Al Aloola, N.; Saini, B. Asthma patients in Saudi Arabia–preferences, health beliefs and experiences that shape asthma management. Ethn. Health 2022, 27, 877–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb Dailah, H. Investigating the outcomes of an asthma educational program and useful influence in public policy. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 736203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habib, S.S.; Alzoghaibi, M.A.; Abba, A.A.; Hasan, M. Relationship of the Arabic version of the asthma control test with ventilatory function tests and levels of exhaled nitric oxide in adult asthmatics. Saudi. Med. J. 2014, 35, 397–402. [Google Scholar]

- Tarraf, H.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Al Qaseer, A.H.; Gjurovic, A.; Haouichat, H.; Khassawneh, B.; Mahboub, B.; Naghshin, R.; Montestruc, F.; Behbehani, N. Asthma control in adults in the Middle East and North Africa: Results from the ESMAA study. Respir. Med. 2018, 138, 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayeb, M.M.S.; Aldini, M.A.M.; Laskar, A.K.A.; Alnashri, I.A.M. Prevalence of asthma-triggering drug use in adults and its impact on asthma control: A cross-sectional study–Saudi (Jeddah). Australas. Med. J. 2017, 10, 1003–1007. [Google Scholar]

- Torchyan, A.A.; BinSaeed, A.A.; Khashogji, S.d.A.; Alawad, S.H.; Al-Ka’ABor, A.S.; Alshehri, M.A.; Alrajhi, A.A.; Alshammari, M.M.; Papikyan, S.L.; Gosadi, I.M.; et al. Asthma quality of life in Saudi Arabia: Gender differences. J. Asthma 2017, 54, 202–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alanazi, T.M.; Alghamdi, H.S.; Alberreet, M.S.; Alkewaibeen, A.M.; Alkhalefah, A.M.; Omair, A.; Al-Jahdali, H.; Al-Harbi, A. The prevalence of sleep disturbance among asthmatic patients in a tertiary care center. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, C.; Sicras-Mainar, A.; Sicras-Navarro, A.; Sogo, A.; Mirapeix, R.; Engroba, C. Prevalence, T2 Biomarkers, and Cost of Severe Asthma in the Era of Biologics: The BRAVO-1 Study. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 2024, 34, 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Gao, J.; Lai, K.; Zhou, X.; He, B.; Zhou, J.; Wang, C.; Fehrenbach, H. The characteristic of asthma control among nasal diseases population: Results from a cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0191543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mishra, R.; Kashif, M.; Venkatram, S.; George, T.; Luo, K.; Diaz-Fuentes, G. Role of Adult Asthma Education in Improving Asthma Control and Reducing Emergency Room Utilization and Hospital Admissions in an Inner City Hospital. Can. Respir. J. 2017, 2017, 5681962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Backman, H.; Jansson, S.A.; Stridsman, C.; Eriksson, B.; Hedman, L.; Eklund, B.M.; Sandström, T.; Lindberg, A.; Lundbäck, B.; Rönmark, E. Severe asthma—A population study perspective. Clin. Exp. Allergy 2019, 49, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.N.; Huynh, T.T.H.; Chavannes, N.H. Knowledge on self-management and levels of asthma control among adult patients in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. IJGM 2018, 11, 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Lai, Z.; Qiu, R.; Guo, E.; Li, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, N. Positive change in asthma control using therapeutic patient education in severe uncontrolled asthma: A one-year prospective study. Asthma Res. Pract. 2021, 7, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrichs, K.; Hummel, S.; Gholami, J.; Schultz, K.; Li, J.; Sheikh, A.; Loerbroks, A. Psychosocial working conditions, asthma self-management at work and asthma morbidity: A cross-sectional study. Clin. Transl. Allergy 2019, 9, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, S.; Jaan, G.; Nadeem, A.; Nadeem, J.; Fatima, K.; Sajjad, A.; Javed, F.; Mazhar, M.; Iqbal, M.Z. Effect of educational intervention on quality of life of asthma patients: A systematic review. Med. Sci. 2024, 28, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiotiu, A.; Ioan, I.; Wirth, N.; Romero-Fernandez, R.; González-Barcala, F.J. The Impact of Tobacco Smoking on Adult Asthma Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mroczek, B.; Kurpas, D.; Urban, M.; Sitko, Z.; Grodzki, T. The Influence of Asthma Exacerbations on Health-Related Quality of Life. In Ventilatory Disorders; Pokorski, M., Ed.; Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 873, pp. 65–77. Available online: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/5584_2015_157 (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Almqvist, C.; Worm, M.; Leynaert, B. WP 2.5 ‘Gender’for the working group of G. Impact of gender on asthma in childhood and adolescence: A GA2LEN review. Allergy 2008, 63, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.R.; Lingam, R.; Owens, L.; Chen, K.; Shanthikumar, S.; Oo, S.; Schultz, A.; Widger, J.; Bakar, K.S.; Jaffe, A.; et al. Social deprivation and spatial clustering of childhood asthma in Australia. Glob. Health Res. Policy 2024, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Hussain, S.; Ayesha Farhana, S.; Mohammed Alnasser, S. Time Trends and Regional Variation in Prevalence of Asthma and Associated Factors in Saudi Arabia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BioMed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 8102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murray, C.S.; Foden, P.; Sumner, H.; Shepley, E.; Custovic, A.; Simpson, A. Preventing Severe Asthma Exacerbations in Children. A Randomized Trial of Mite-Impermeable Bedcovers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 196, 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalçınkaya, G.; Kılıç, M. Asthma Control Level and Relating Socio-Demographic Factors in Hospital Admissions. Int. J. Stat. Med. Res. 2022, 11, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleid, A.; Alolayani, R.A.; Alkharouby, R.; Gawez, A.R.A.; Alshehri, F.D.; Alrasan, R.A.; Alsubhi, R.S.; Al Mutair, A. Environmental Exposure and Pediatric Asthma Prevalence in Saudi Arabia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Cureus 2023, 15, e46707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cilluffo, G.; Ferrante, G.; Fasola, S.; Malizia, V.; Montalbano, L.; Ranzi, A.; Badaloni, C.; Viegi, G.; La Grutta, S. Association between Asthma Control and Exposure to Greenness and Other Outdoor and Indoor Environmental Factors: A Longitudinal Study on a Cohort of Asthmatic Children. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, Y.; Yuan, S.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Wu, J.; Zhang, J.; Yin, Y. Research on the improvement of allergic rhinitis in asthmatic children after reducing dust mite exposure: A randomized, double-blind, cross-placebo study protocol. Res. Sq. 2020, 21, 686. [Google Scholar]

- Jaakkola, M.S.; Hyrkäs-Palmu, H.; Jaakkola, J.J.K. Residential Exposure to Dampness Is Related to Reduced Level of Asthma Control among Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 11338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Engelkes, M.; Janssens, H.M.; Jongste, J.C.; de Sturkenboom, M.C.J.M.; Verhamme, K.M.C. Medication adherence and the risk of severe asthma exacerbations: A systematic review. Eur. Respir. J. 2015, 45, 396–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosse, R.C.; Bouvy, M.L.; Vries, T.W.; de Koster, E.S. Effect of a mHealth intervention on adherence in adolescents with asthma: A randomized controlled trial. Respir. Med. 2019, 149, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onubogu, U.C.; Owate, E. Pattern of Acute Asthma Seen in Children Emergency Department of the River State University Teaching Hospital Portharcourt Nigeria. Open J. Respir. Dis. 2019, 9, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Timilsina, M.; Banstola, S. Impact of Pharmacist-led Interventions on Medication Adherence and Inhalation Technique in Adult Patients with COPD and Asthma. J. Health Allied Sci. 2023, 13, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.K.; Peterson, E.L.; Wells, K.; Ahmedani, B.K.; Kumar, R.; Burchard, E.G.; Chowdhry, V.K.; Favro, D.; Lanfear, D.E.; Pladevall, M. Quantifying the proportion of severe asthma exacerbations attributable to inhaled corticosteroid nonadherence. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 1185–1191.e2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).