Abstract

Ameloblastoma is a rare, benign, but locally aggressive odontogenic tumor that originates from the epithelial cells involved in tooth development. The surgical approach to treating an ameloblastoma depends on the type, size, location, and extent of the tumor, as well as the patient’s age and overall health. This umbrella review’s aim is to summarize the findings from systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses on the effect of radical or conservative treatment of ameloblastoma on the recurrence rate and quality of life, to evaluate the methodological quality of the included SRs and discuss the clinical management. Three electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, The Cochrane Library) were checked. The primary outcome was the recurrence rate after surgical treatment, while the secondary outcomes were the post-operative complications, quality of life, esthetic, and functional impairment. The methodological quality of the included SRs was assessed using the updated version of “A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Review” (AMSTAR-2). Eighteen SRs were included. The quality of the included reviews ranged from critically low (three studies) to high (eight studies). Four studies were included in meta-analysis, and they revealed that the recurrence rate is about three-times more likely in the conservative treatment group compared to the radical treatment group, and this result is statistically significant. Despite the high recurrence rate, the latter was more appropriate in the case of smaller lesions and younger patients, due to better post-operative quality of life and reduced functional and esthetic impairments. Based on the results of this overview, conservative treatment may be recommended as the first-line approach for intraosseous ameloblastoma not involving soft tissue. However, given the expectation of a higher recurrence rate, it is advisable to reduce the interval between follow-up visits. However, further prospective studies are needed to establish the best treatment choice and follow-up period.

1. Introduction

Ameloblastoma is a rare, benign odontogenic tumor of epithelial origin, accounting for approximately 10% of all jaw tumors [1] and 13–58% of all odontogenic tumors [2]. The global incidence rate of ameloblastoma is 0.92 per million population per year, with heterogeneous incidence rates between studies [3]. Among all the cases, 53.2% cases are male and 46.7% are female, with a male/female ratio of 1.14:1. Overall, the peak incidence of ameloblastoma, worldwide, is in the third decade [3]. Despite its benign nature, ameloblastoma exhibits locally invasive growth, rare metastases, and has high rate of recurrence [4], posing significant challenges in clinical management and impacting patient quality of life and healthcare systems, requiring substantial resources for surgical interventions, long-term follow-up, rehabilitation, and ongoing care [5,6]. The World Health Organization (WHO) 2022 classification of ameloblastoma reflects the latest understanding of its diagnosis, histopathological features, and clinical behavior [7]. Three types of ameloblastoma have been described. Conventional ameloblastoma, previously known as solid/multicystic ameloblastoma, is the most common type, typically occurring in the mandible and exhibiting various histopathological patterns, including follicular, plexiform, acanthomatous, and desmoplastic [8,9]. Unicystic ameloblastoma is a cystic lesion that, while presenting clinical and radiological characteristics typical of an ordinary jaw cyst, contains ameloblastomatous cells within the epithelial lining of the cyst upon histological examination. These cells may or may not infiltrate the lumen of the cyst or its connective tissue wall. This type accounts for approximately 5 to 22% of all ameloblastomas, primarily affecting younger individuals, and presents three histological variants: luminal, intraluminal, and mural [10,11]. Peripheral ameloblastoma is a rare variant occurring in the soft tissues overlying the jaws. Typically, it is less aggressive than intraosseous forms [12,13].

The most common symptom of ameloblastoma is a painless swelling or expansion of the jaw, typically affecting the mandible more than the maxilla [14]. This swelling can become noticeable over time as the tumor grows. Due to the swelling and expansion, patients may exhibit noticeable facial asymmetry. Although often painless initially, as the tumor enlarges, it can cause pain or discomfort, particularly if it invades surrounding tissues or structures, with possible tooth displacement and mobility [15].

Conventional ameloblastoma may appear multilocular (“Soap Bubble” or “Honeycomb”), and this is the classic presentation, where the lesion appears as a radiolucent area with multiple internal septations, creating a bubble-like pattern, or as unilocular radiolucency. In some cases, particularly in smaller or early-stage lesions, ameloblastomas may present as a single, well-defined radiolucent area [16].

The differential diagnosis of ameloblastoma may be difficult when lesions and tumors of the jaw can present similar clinical and radiographic findings. The main conditions to consider are the Odontogenic Keratocyst [17], Dentigerous Cyst, Adenomatoid Odontogenic Tumor (AOT), and Central Giant Cell Granuloma (CGCG) [18].

Currently, surgery is considered the most effective therapeutic option for this odontogenic lesion. To achieve complete excision of the lesion, either a conservative or radical approach can be employed for the treatment of ameloblastoma.

Although invasive surgical procedures like enucleation and resection are commonly preferred treatments, they can lead to serious complications, such as facial deformities, maxillary bone fractures, dental losses, and paresthesia [19,20,21]. In this regard, more conservative surgical techniques, such as marsupialization and decompression, may be suitable options [22]. These techniques are significantly less invasive, and several studies have reported positive results in reducing jaw lesions [23].

Despite the prevalence of surgical intervention, the optimal treatment approach for ameloblastoma remains debated, with various systematic reviews (SRs) examining outcomes like recurrence rates, quality of life, and esthetic and functional impairment. Given the existing body of SRs, an overview of SRs is warranted to synthesize the available evidence, assess the quality of the SRs, and provide clinicians with a comprehensive summary. To our knowledge, this is the first overview conducted on this topic. This overview aims to summarize the findings from SRs and meta-analyses on patients with primary or recurrent conventional or unicystic ameloblastoma treated with radical and conservative approaches, evaluate the methodological quality of the included SRs, and discuss the clinical management of this complex oral pathology.

2. Materials and Methods

This review was designed as an umbrella review (overview of systematic review) with a meta-analysis. It was compiled adhering to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines. According to the PICO (P: population, I: intervention, C: comparison, O: outcome) protocol, this overview aimed to answer to the following question: “Does conservative surgical treatment of ameloblastoma (intervention) lead to a higher recurrence rate (outcome) according to patient’s age and dimension of tumor, compared to radical surgical treatments (Comparison), in patients with primary ameloblastoma or with a recurrent ameloblastoma (Population)?” Conventional surgical treatments are considered as enucleation, curettage, peripheral ostectomy, marsupialization, decompression, Carnoy’s solution or a combination of these techniques, while invasive surgical treatments are considered segmental resection, marginal resection, emimandibulectomy/emimaxillectomy, total jaw resection. All histological types of ameloblastoma were included. Ameloblastic carcinoma and metastasizing ameloblastoma were excluded. The primary outcome was the recurrence rate after surgical treatment, while secondary outcomes were the post-operative complications, quality of life, esthetic, and functional impairment (functional limitations in chewing, speaking, sleeping and inability to perform daily routines and work activities correctly).

2.1. Literature Search

Initially, a pilot search was conducted on PubMed to check the presence of existing overviews and enough systematic reviews (SRs) that could serve as a solid foundation for the creation of the above-mentioned overview. Literature research was conducted for reviews and meta-analyses published up to June 2024 using three electronic databases (PubMed, Scopus, The Cochrane Library). Different combinations of keywords and MeSH terms, according to the database’s rules, were developed to identify suitable studies. Search strategy is reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy for each database.

A manual search was performed in oral surgery journals (International Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Oral Disease, Japanese Dental Science Review), and a further search was performed among the references of the included articles. An attempt to explore grey literature involved searching through conference abstracts published on Web of Science and Scopus, as well as databases of scientific dental congresses (Società Italiana di Chirurgia Odontostomatologica (SIdCO), International Association for Dental Research (IADR), Società Italiana di Patologia e Medicina Orale (SIPMO), European Association of Oral Medicine (EAOM)). Moreover, the reference lists of all included studies and relevant review articles were manually examined to identify any additional studies that may have been missed during the electronic search. The review’s selection was performed by two independent reviewers (MDC, EL). Eligibility criteria were only SRs and meta-analyses addressing the recurrence rate of ameloblastoma and quality of life after a conventional or radical surgical treatment, in English language, published up to June 2024. The exclusion criteria were as follows: clinical controlled trials (CCTs) and randomized controlled trials (RCTs), duplicate publications, narrative reviews, case series, surveys, radiographic studies, studies with solely histological data, animal studies, case reports, letters to the editor, and in vitro studies. Additionally, abstracts and articles written in languages other than English were excluded. Following the screening of titles and abstracts, articles were selected for full-text eligibility. In cases where discrepancies arose in assessing the eligibility of titles and abstracts, full texts were included for final evaluation. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through the involvement of a third reviewer (GS).

Potential sources of bias like selection bias, publication bias, and heterogeneity of included reviews were addressed and minimized by using a thorough and systematic search strategy, clearly reporting the selection criteria for included reviews and evaluating the methodological quality of each systematic review with tools like AMSTAR-2.

2.2. Data Extraction

Two authors (MDC, EL) independently extracted data using a pre-established extraction form to minimize the risk of errors and bias. Each reviewer recorded the data on a separate extraction form. In cases where clarity was lacking in the systematic reviews (SRs), the individual studies themselves were consulted. No further details were sought from the authors. After independent extraction, the two reviewers compared their forms to identify discrepancies. Any differences were discussed and resolved through consensus. If consensus could not be reached, a third reviewer was consulted. From each study, author, publication year, search period, databases, study design (SR with or without meta-analysis), diagnosis, intervention and control groups, quality tool and quality of the individual studies, outcome measures, results, and author’s conclusion were extracted.

2.3. Methodological Quality of Included Reviews

The methodological quality of the included SRs was independently assessed by two reviewers [VS, AA] using the updated version of A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Review (AMSTAR-2) [24]. This independent assessment helped minimize bias and ensured that all aspects of the review were thoroughly evaluated. AMSTAR-2 is a valid and reliable instrument made of 16 items (Protocol Registration, Literature Search Adequacy, Study Design Criteria, Search Strategy Details, Study Selection Process, Data Extraction Process, Explanation of Exclusions, Description of Included Studies: Risk of Bias Assessment, Funding Source Disclosure, Meta-Analysis Methods, Impact of Bias on Results, Risk of Bias in Interpretation, Heterogeneity Assessment, Statistical Methods, Conflicts of Interest), which correspond to three possible responses: “yes,” (indicating the criterion was met), “partial yes” (partially met), or “no.” (not met). Following the assessment of weaknesses identified in both critical and non-critical aspects, the overall quality rating of a systematic review (SR) was categorized as “high”, “moderate”, “low”, or “critically low” as follows: high: no or one non-critical weakness; moderate: more than one non-critical weakness; low: one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses; critically low: more than one critical flaw with or without non-critical weaknesses.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the Restricted Maximum Likelihood method. The pooled effect size was reported with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic, and a 95% prediction interval (PI) was calculated. An I2 value greater than 50% indicated significant heterogeneity, while the 95% PI estimated the potential range of true effects for future studies. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression test. Additionally, a test for excess significance was performed to determine whether the observed number of statistically significant results exceeded the expected number, suggesting potential data tortures or reporting bias. This assessment was conducted using the Proportion of Statistical Significance Test (PSST). If a study was included in multiple meta-analyses, only one instance was retained to avoid bias. Multiple effect sizes reported for a single study were retained if they originated from independent subgroups. In cases where multiple studies shared participants from the same group but compared them to different groups, these studies were identified, and adjustments were made to the calculations by dividing the shared sample size by the number of studies using it.

All statistical analyses were performed using the ‘metaumbrella’ package in the R statistical software (version 4.3.3) [25]. Statistical significance for all tests was set at α = 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

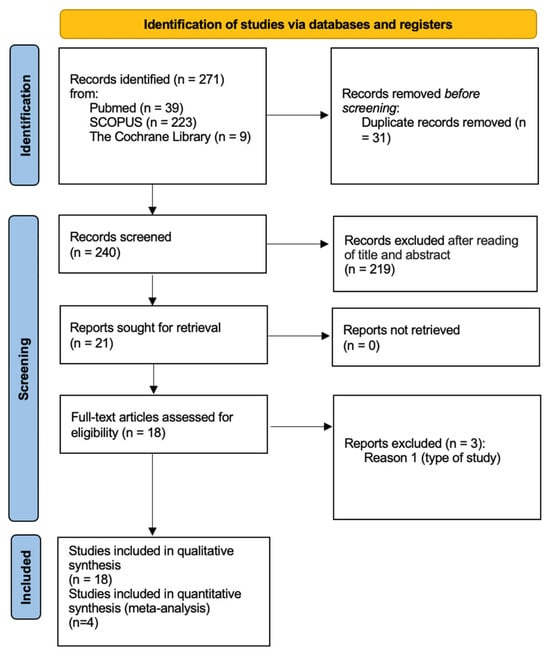

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study selection.

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram. From: https://www.bmj.com/content/372/bmj.n71 (accessed on 7 September 2024).

Thus, 271 records were discovered through both electronic and manual searches. Following the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 240 records were reviewed. Of these, 56 articles were included for full-text reading, while 29 were excluded according to the application of the exclusion criteria.

Finally, 18 SRs were included for the qualitative analysis [26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43].

3.2. Characteristics of Included Reviews

Data extracted from the eighteen (18) SRs are summarized in Table 2. The number of primary studies included in each SR ranged between 6 and 76. Some of SRs were integrated with a meta-analysis [26,29,33,34,38,39,41,42]. Most of the systematic reviews included case reports and case series as primary studies [27,28,29,31,32,33,34,36,38,40,43], while other reviews also included prospective and retrospective studies [34,35,41,42]. Two SRs did not specify the type of primary studies included [26,39]. The number of total subjects included in each review was not always clarified. The diagnosis was related to different types of ameloblastoma: solid or multicystic [26,29,31,33,34,35,38,41,42,43], unicystic [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,38,39,40,41,42,43], desmoplastic ameloblastoma [27], peripheral ameloblastoma [28], adenoid ameloblastoma [32], sinonasal ameloblastoma [37]. All diagnoses were about primary ameloblastomas, while only one study also considered the recurrent form [36].

Table 2.

Study characteristics.

The surgical procedures studied were radical treatments, such as marginal and segmental resection [26,29,31,33,34,36,38,39,41,43], segmental mandibulectomy [31,42,43], and maxillectomy [37,41], and conservative treatments, such as curettage [28,29,31,35,36,37,38,42,44,45], enucleation [26,28,29,32,33,34,35,36,37,39,40,41,42,43], marsupialization, and decompression [30,33,36,40,42]. Both treatments were associated with adjuvant procedures, like cryotherapy [26,29,33,34,39], radiotherapy [28,32,37], Carnoy’s solution [26,33,34,35,36,40,41], bone reconstruction [27,31,43]. Some SRs did not indicate any control group [30,31,38]. In most of the studies, the primary outcome was the recurrence rate. Other reported outcomes were post-operative complications and patient-centered outcomes.

3.3. Methodological Quality Results

The methodological quality of the included reviews, as measured with the AMSTAR-2, ranged from critically low (three studies) to high (eight studies). The most common critical weakness in the included reviews was the absence of clearly a priori established review methods and any significant deviations from the protocol (Table 3).

Table 3.

Quality assessment of the included systematic review.

3.4. Clinical Results

Most authors agreed that radical surgery, as marginal or segmental resection, was more appropriate in reducing the recurrence rate of both multicystic and unicystic ameloblastomas in comparison with conservative treatments [26,29,31,33,34,36,39,41,42,43]. Only Netto and collaborators [38] compared two radical approaches and pointed out that the group that underwent marginal resection was 1.1-times more likely to present recurrence of the lesion compared to the group that underwent segmental resection. However, there was no statistically significant difference between groups in all studies included.

Conservative treatments, like enucleation, decompression, and marsupialization, were not considered as a definitive surgery, but they were useful only to lower the invasiveness of the second surgery [30]. Lesion reduction was generally considered insufficient for these techniques to be used as definitive therapies. Moreover, according to Anpalagana A. [28] and Seintou A. et al. [40], a more conservative approach, consisting of an excision with narrow margin of normal tissue, was found to be appropriate for treating peripheral ameloblastomas with a low recurrence rate.

In Hendra et al. 2019 [33], the pooled recurrence rate of solid/multicystic ameloblastomas following radical treatment was 8%, while conservative treatment caused recurrences in 41%. For unicystic ameloblastomas, these values were 3% and 21%, respectively.

Similarly, Almeida et al. [26] showed that the relative risk of recurrence was 3.15-fold greater when conservative treatment was performed on primary multicystic ameloblastoma in comparison to radical treatment.

In da Silva et al. [41], the pooled values pointed out that the recurrence rate after the conservative surgery is neither comparable nor lower than the radical surgery (p = 0.28).

Seintou [40] and Anand [27] were the only researchers who took into account the age of patients in order to choose the best surgical option. According to both, a conservative approach is preferred in the case of young patients as it offers a better-quality life (functional limitation, physical pain, psychological discomfort). Moreover, according to Anand, specific lesions of less than 3 mm had to be treated by curettage in young people.

De Campos [31] was the only researcher who discussed the impact of surgical treatment of ameloblastoma on the oral health-related quality of life and the surgery-related complications, highlighting that invasive surgical treatment was associated with a high risk of post-operative complications, such as infections, fracture of cortical bone, plate traumatizing oral tissues, and graft loss. Finally, some of the included SRs dealt with the absence of an additive benefit of Carnoy’s solution as an adjuvant in the surgical treatment of ameloblastomas [35,36].

3.5. Meta-Analysis Results

The results of the meta-analysis are presented in Table 4. The primary outcome assessed was the recurrence rate. Only four studies included this in data synthesis [26,33,41,42], as they provided raw data on the recurrence rates for each study included. The meta-analysis revealed a significant combined effect size (RR = 3.01, 95% CI [2.02, 4.51], p < 0.001) with low heterogeneity (I2 < 50%) and a 95% prediction interval (PI) that did not include the value of 1. The test for excess statistical significance was not statistically significant (p = 0.177); however, Egger’s regression test indicated evidence of significant publication bias (p = 0.03).

Table 4.

Meta-analysis results.

4. Discussion

The aim of this overview was to summarize findings from systematic reviews (SRs) and meta-analyses on the radical or conservative treatment of ameloblastoma, to evaluate the methodological quality of the included SRs and discuss the clinical management. Based on the results of the current overview, we confirmed the intuitive concept that a radical approach leads to a lower recurrence rate. However, consideration of the post-operative complications and quality of life may be considered when the tumor affects young people or compromised patients. The recurrence rate depends not only on the surgical treatment but also on multiple other factors, like type of tumor, histological variants, surgical ability, and instruments used. It has been established that multicystic ameloblastoma exhibits a significantly higher recurrence rate compared to unicystic ameloblastoma [44]. Despite this, conservative treatment remains the primary approach for managing unicystic ameloblastoma [45,46]. Histological variants have previously been regarded as different types of ameloblastoma [47], each exhibiting different recurrence rates [48]. Despite these surgery-related risks, factors like the patient’s age, the anatomical location and size of the lesion, and its histological diagnosis should be considered in treatment planning to achieve a better prognosis. In this overview, only a few studies reported histological findings, making the data on recurrence rates not entirely comparable. However, the 2022 classification consolidated these variants into a single entity known as conventional ameloblastoma, potentially overcoming any selection bias. Regarding the surgical ability and instruments used, fully enucleating the lesion and removing all the possible tumor extensions still represent the major clinical challenge, especially for tumors located in proximity to important anatomic structures. A study by Troiano et al. revealed a lower rate of relapse at 5 years’ follow-up for patients treated with piezo surgery compared to conventional peripheral osteotomy in the treatment of conventional ameloblastoma located in proximity to the nervous alveolar bundle [49]. This method ensures highly effective hard tissue cutting and does not harm soft tissues, reporting lower post-operative complications [50]. The AMSTAR scale is a validated tool for assessing the methodological quality of systematic reviews (SRs). AMSTAR-2, developed to appraise both randomized and non-randomized healthcare intervention studies, includes 16 items and evaluates weaknesses in critical domains. This overview found that the methodological quality of reviews ranged from critically low to high, with the most common weakness being the absence of clearly established review methods and significant protocol deviations.

The meta-analysis revealed a significant combined effect size (RR = 3.01, 95% CI [2.02, 4.51], p < 0.001). This means that, on average, the recurrence rate is about three-times more likely in the conservative treatment group compared to the radical treatment group, and this result is statistically significant. The heterogeneity in this meta-analysis is low (I2 < 50%). Low heterogeneity suggests that the studies included in the meta-analysis are relatively consistent in their findings, and the combined effect size is a reliable estimate of the true effect. Another finding suggests that the 95% prediction interval (PI) did not include the value of 1. This is important because the prediction interval provides a range within which the effect size of a future study is expected to fall. Since the PI does not include 1, it suggests that even a new study is likely to find a similar positive effect, reinforcing the robustness of the findings.

The test for excess statistical significance did not show statistical significance (p = 0.177). This means there is no strong evidence that the observed results were due to an excess of studies with statistically significant findings, which could indicate selective reporting or other biases. However, Egger’s regression test indicated significant publication bias (p = 0.03). This finding suggests that the meta-analysis results might be influenced by publication bias, which could inflate the combined effect size. In summary, the meta-analysis demonstrates a strong and significant combined effect with low heterogeneity, but the presence of publication bias should be considered when interpreting the results.

4.1. Clinical Management

The surgical plan of ameloblastoma is determined after thorough clinical and radiographical investigations and histological diagnosis. A CT scan is useful for evaluating tumor boundaries and planning resection margins. For cases with cortical perforation and soft tissue infiltration, marginal or segmental resection, including soft tissue removal, is recommended [51]. Moreover, teeth involved with the tumor should be removed to prevent recurrence within the periodontal ligament [52]. Together with radical treatment, a reconstruction is needed to rehabilitate the esthetics and function [53], especially in young patients. In the present overview, few data have been reported about the complications related to radical surgery. Based on the results of this overview and our experience, we recommend conservative treatment as the first-line approach for intraosseous ameloblastoma not involving soft tissue. However, given the expectation of a higher recurrence rate, it is advisable to reduce the interval between follow-up visits. Early detection of recurrences, which are typically small and surrounded by a large amount of normal bone, allows for management with radical resection. This approach reduces the risk of further recurrence and helps avoid severe cosmetic and functional issues [54].

4.2. Future Perspectives

As reported before, traditionally, the treatment for ameloblastoma has been surgical. However, advancements in molecular biology have opened new perspectives for targeted therapies, particularly focusing on genetic mutations associated with the disease [55].

One of the most significant developments in the understanding of ameloblastoma at the molecular level is the identification of mutations in the BRAF gene [56]. The BRAF V600E mutation, which is common in various cancers, has been detected in a significant proportion of ameloblastoma cases. This discovery has opened the way for the potential use of BRAF inhibitors in the treatment of this tumor, such as vemurafenib and dabrafenib. These inhibitors work by specifically targeting and inhibiting the activity of the mutated BRAF protein, thereby reducing cell proliferation and inducing tumor regression [57]. In a recent study by Mamat Yusof et al. [58], the BRAF V600E mutation had a high pooled prevalence of 70.49% in ameloblastoma. Furthermore, a significant meta-analysis association was reported for those younger than 54 years old and in the mandible. On the contrary, other factors, such as sex, histological variants, and recurrence, were insignificant among ameloblastoma cases with the BRAF V600E mutation. In a study by Singh et al. [59], within the BRAFv600e+ group, females showed a higher reported recurrence rate. However, not all ameloblastomas present the BRAF V600E mutation, so patient selection based on genetic profiling will be important to optimize treatment efficacy. Research into the long-term outcomes of patients treated with BRAF inhibitors is necessary. If BRAF inhibitors prove to be effective, they could potentially reduce the need for extensive surgical procedures, leading to less morbidity and better cosmetic and functional results for patients. However, further well-designed cohort studies are needed to verify the association of the BRAF V600E mutation in ameloblastoma before applying new medical interventions.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

The strength of the present study is the use of a high-quality search method adhering to PRISMA guidelines and a robust quality evaluation method following AMSTAR-2 standards. However, the findings of the current study should be understood in the light of important limitations. Although a comprehensive search strategy was employed and complemented through extensive manual cross-reference searching for the identification of all relevant articles, it may still be possible that some grey literature was missed. Additionally, it should be noted that most of the current literature reported mainly retrospective studies and case report/case series. Further prospective, multicenter, controlled trials with rigorous reporting and analysis of results and long-term follow-up-period studies are encouraged as they are lacking. Encouraging such studies would significantly strengthen the evidence base for ameloblastoma treatment. Moreover, long-term follow-up data are scarce, making it challenging to assess treatment efficacy. Establishing standardized follow-up protocols would facilitate more accurate assessments.

5. Conclusions

The primary finding of this umbrella review is that radical treatments for ameloblastoma are associated with significantly lower recurrence rates compared to conservative treatments. This suggests that radical approaches may offer better long-term disease control. On the other hand, with regard to post-operative complications and esthetic and functional impairments, few results arise from the currently published SRs. For clinicians, this review underscores the importance of weighing the benefits of lower recurrence rates against the risks of adverse outcomes, including esthetic and functional impairments. Moreover, the current overview of SRs highlighted that the quality level of the published SRs was extremely variable, thus ranging from critically low to high. Therefore, researchers are encouraged to focus on high-quality, prospective studies that can provide more definitive evidence on the comparative effectiveness and safety of radical versus conservative treatments. Improved methodological rigor and standardized outcome measures will enhance the reliability of future research and guide clinical decision making. Moreover, advancements in molecular biology may open up new perspectives for targeted therapies, focusing on genetic mutations associated with this disease. Further prospective studies are needed to establish the best treatment choice and follow-up period.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.G. and F.G.; methodology, M.D.C.; software, E.L.; validation, G.S., A.E.d.L. and F.G.; formal analysis, P.D.; investigation, E.L.; resources, A.A.; data curation, M.D.C.; writing—original draft preparation, R.G.; writing—review and editing, G.S.; supervision, A.E.d.L.; project administration, G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Masthan, K.M.; Anitha, N.; Krupaa, J.; Manikkam, S. Ameloblastoma. J. Pharm. Bioallied Sci. 2015, 7 (Suppl. S1), S167–S170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghai, S. Ameloblastoma: An Updated Narrative Review of an Enigmatic Tumor. Cureus 2022, 14, e27734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendra, F.N.; Van Cann, E.M.; Helder, M.N.; Ruslin, M.; de Visscher, J.G.; Forouzanfar, T.; de Vet, H.C.W. Global incidence and profile of ameloblastoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2020, 26, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Naggar, A.K.; Chan, J.K.C.; Takata, T.; Grandis, J.R.; Slootweg, P.J. The fourth edition of the head and neck World Health Organization blue book: Editors’ perspectives. Hum. Pathol. 2017, 66, 10–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasparro, R.; Calabria, E.; Coppola, N.; Marenzi, G.; Sammartino, G.; Aria, M.; Mignogna, M.D.; Adamo, D. Sleep Disorders and Psychological Profile in Oral Cancer Survivors: A Case-Control Clinical Study. Cancers 2021, 13, 1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandu, A.; Smith, A.C.; Rogers, S.N. Health-related quality of life in oral cancer: A review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 64, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vered, M.; Wright, J.M. Update from the 5th Edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Head and Neck Tumors: Odontogenic and Maxillofacial Bone Tumours. Head Neck Pathol. 2022, 16, 63–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correa-Arzate, L.; Portilla-Robertson, J.; Ramírez-Jarquín, J.O.; Jacinto-Alemán, L.F.; Mejía-Velázquez, C.P.; Villanueva-Sánchez, F.G.; Rodríguez-Vázquez, M. LRP5, SLC6A3, and SOX10 Expression in Conventional Ameloblastoma. Genes 2023, 14, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustine, D.; Rao, R.S.; Surendra, L.; Patil, S.; Yoithapprabhunath, T.R.; Albogami, S.; Shamsuddin, S.; Basheer, S.A.; Sainudeen, S. Histopathologic Feature of Hyalinization Predicts Recurrence of Conventional/Solid Multicystic Ameloblastomas. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, R.; Lin, X.; Zhang, W.; Gokavarapu, S.; Lin, C.; Ren, Z.; Hu, Y.; Cao, W.; Ji, T. Unicystic ameloblastoma: A retrospective study on recurrent factors from a single institute database. Oral Dis. 2024, 30, 1475–1482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, S. Unicystic Ameloblastoma: A Perception for the Cautious Interpretation of Radiographic and Histological Findings. J. Coll. Physician. Surg. Park 2015, 25, 761–764. [Google Scholar]

- Ide, F.; Ito, Y.; Miyazaki, Y.; Nishimura, M.; Kusama, K.; Kikuchi, K. A New Look at the History of Peripheral Ameloblastoma. Head Neck Pathol. 2020, 14, 1052–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlAli, A.M.; Hawkins, D.; Glass, S. Peripheral ameloblastoma underlying squamous cell papilloma after a third molar extraction. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Radiol. 2024, 137, e53–e56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeel, M.; Rajput, M.S.A.; Arain, A.A.; Baloch, M.; Khan, M. Ameloblastoma: Management and Outcome. Cureus 2018, 10, e3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elo, J.A.; Tandon, R.; Allen, C.N.; Murray, M.D. Hemimaxillectomy for desmoplastic ameloblastoma with immediate temporalis flap reconstruction. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2014, 118, e33–e39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitisubkanchana, J.; Reduwan, N.H.; Poomsawat, S.; Pornprasertsuk-Damrongsri, S.; Wongchuensoontorn, C. Odontogenic keratocyst and ameloblastoma: Radiographic evaluation. Oral Radiol. 2021, 37, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Lauro, A.E.; Romeo, G.; Scotto, F.; Guadagno, E.; Gasparro, R.; Sammartino, G. Odontogenic keratocystic can be misdiagnosed for a lateral periodontal cyst when the clinical and radiographical findings are similar. Minerva Dent. Oral Sci. 2022, 71, 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, H.; Zhai, G.; Han, J. Differential diagnosis of ameloblastoma and odontogenic keratocyst by machine learning of panoramic radiographs. Int. J. Comput. Assist. Radiol. Surg. 2021, 16, 415–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandriyal, R.; Gupta, A.; Pant, S.; Baweja, H.H. Surgical management of ameloblastoma: Conservative or radical approach. Natl. J. Maxillofac. Surg. 2011, 2, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraddi, G.B.; Arora, K.; Saifi, A.M. Ameloblastoma: A retrospective analysis of 31 cases. J. Oral Biol. Craniofac. Res. 2017, 7, 206–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruslin, M.; Hendra, F.N.; Vojdani, A.; Hardjosantoso, D.; Gazali, M.; Tajrin, A.; Wolff, J.; Forouzanfar, T. The Epidemiology, treatment, and complication of ameloblastoma in East-Indonesia: 6 years retrospective study. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2018, 23, e54–e58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laino, L.; Cicciù, M.; Russo, D.; Cervino, G. Surgical Strategies for Multicystic Ameloblastoma. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2020, 31, e116–e119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liang, Q.; Yang, L.; Zheng, G.S.; Zhang, S.E.; Lao, X.M.; Liang, Y.J.; Liao, G.Q. Marsupialization of mandibular cystic ameloblastoma: Retrospective study of 7 years. Head Neck 2018, 40, 2172–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Br. Med. J. 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosling, C.J.; Solanes, A.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Radua, J. Metaumbrella: The first comprehensive suite to perform data analysis in umbrella reviews with stratification of the evidence. BMJ Ment. Health 2023, 26, e300534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida Rde, A.; Andrade, E.S.; Barbalho, J.C.; Vajgel, A.; Vasconcelos, B.C. Recurrence rate following treatment for primary multicystic ameloblastoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2016, 45, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anand, R.; Sarode, G.S.; Sarode, S.C.; Reddy, M.; Unadkat, H.V.; Mushtaq, S.; Deshmukh, R.; Choudhary, S.; Gupta, N.; Ganjre, A.P.; et al. Clinicopathological characteristics of desmoplastic ameloblastoma: A systematic review. J. Investig. Clin. Dent. 2018, 9, e12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anpalagan, A.; Tzortzis, A.; Twigg, J.; Wotherspoon, R.; Chengot, P.; Kanatas, A. Current practice in the management of peripheral ameloblastoma: A structured review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, e1–e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonoglou, G.N.; Sándor, G.K. Recurrence rates of intraosseous ameloblastomas of the jaws: A systematic review of conservative versus aggressive treatment approaches and meta-analysis of non-randomized studies. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2015, 43, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berretta, L.M.; Melo, G.; Mello, F.W.; Lizio, G.; Rivero, E.R.C. Effectiveness of marsupialisation and decompression on the reduction of cystic jaw lesions: A systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, E17–E42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Campos, W.G.; Alkmin Paiva, G.L.; Esteves, C.V.; Rocha, A.C.; Gomes, P.; Lemos Júnior, C.A. Surgical Treatment of Ameloblastoma: How Does It Impact the Oral Health-Related Quality of Life? A Systematic Review. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Farias Morais, H.G.; Gonçalo, R.I.C.; de Oliveira Costa, C.S.; de Figueiredo Pires, H.; Mafra, R.P.; de Morais, E.F.; da Costa Miguel, M.C.; de Almeida Freitas, R. A Systematic Review of Adenoid Ameloblastoma: A Newly Recognized Entity. Head Neck Pathol. 2023, 17, 688–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendra, F.N.; Natsir Kalla, D.S.; Van Cann, E.M.; de Vet, H.C.W.; Helder, M.N.; Forouzanfar, T. Radical vs conservative treatment of intraosseous ameloblastoma: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Oral Dis. 2019, 25, 1683–1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendra, F.N.; Helder, M.N.; Ruslin, M.; Van Cann, E.M.; Forouzanfar, T. A network meta-analysis assessing the effectiveness of various radical and conservative surgical approaches regarding recurrence in treating solid/multicystic ameloblastomas. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, B.; Kumar, R.D.; Alagarsamy, R.; Shanmuga Sundaram, D.; Bhutia, O.; Roychoudhury, A. Role of Carnoy’s solution as treatment adjunct in jaw lesions other than odontogenic keratocyst: A systematic review. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 59, 729–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.L.; Samman, N. Recurrence related to treatment modalities of unicystic ameloblastoma: A systematic review. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2006, 35, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehta, V.; Sarode, G.S.; Obulareddy, V.T.; Sharma, T.; Kokane, S.; Cicciù, M.; Minervini, G. Clinicopathologic Profile, Management and Outcome of Sinonasal Ameloblastoma—A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Netto, R.; Peralta-Mamani, M.; de Freitas-Filho, S.A.; Moura, L.L.; Rubira, C.M.; Rubira-Bullen, I.R. Segmental resection vs. partial resection on treating solid multicystic ameloblastomas of the jaws—Recurrence rates: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2023, 15, e518–e525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, X.; Shi, J.; Liu, J.; Liu, J.; Guo, Y.; Zhong, M. Recurrence Rates of Intraosseous Ameloblastoma Cases with Conservative or Aggressive Treatment: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 11, 647200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seintou, A.; Martinelli-Kläy, C.P.; Lombardi, T. Unicystic ameloblastoma in children: Systematic review of clinicopathological features and treatment outcomes. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slusarenko da Silva, Y.; Tartaroti, N.A.; Sendyk, D.I.; Deboni, M.C.Z.; Naclério-Homem, M.D.G. Is conservative surgery a better choice for the solid/multicystic ameloblastoma than radical surgery regarding recurrence? A systematic review. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 22, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Dioguardi, M.; Cocco, A.; Laino, L.; Cervino, G.; Cicciu, M.; Ciavarella, D.; Lo Muzio, L. Conservative vs Radical Approach for the Treatment of Solid/Multicystic Ameloblastoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Last Decade. Oral Health Prev. Dent. 2017, 15, 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Vidya, A.; Shruthi, H. Ameloblastomas vs recurrent ameloblastomas: A systematic review. J. Oral Med. Oral Surg. 2022, 28, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Effiom, O.A.; Ogundana, O.M.; Akinshipo, A.O.; Akintoye, S.O. Ameloblastoma: Current etiopathological concepts and management. Oral Dis. 2018, 24, 307–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leite-Lima, F.; Martins-Chaves, R.R.; Fonseca, F.P.; Brennan, P.A.; de Castro, W.H.; Gomez, R.S. A conservative approach for unicystic ameloblastoma: Retrospective clinic-pathologic analysis of 12 cases. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2023, 52, 654–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titinchi, F.; Brennan, P.A. Unicystic ameloblastoma: Analysis of surgical management and recurrence risk factors. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 60, 337–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goh, Y.C.; Siriwardena, B.S.M.S.; Tilakaratne, W.M. Association of clinicopathological factors and treatment modalities in the recurrence of ameloblastoma: Analysis of 624 cases. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2021, 50, 927–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, K.; Chaturvedi, T.P.; Gupta, J.; Agrawal, R. Cell proliferation proteins and aggressiveness of histological variants of ameloblastoma and keratocystic odontogenic tumor. Biotech. Histochem. 2019, 94, 348–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troiano, G.; Inghingolo, A.; Serpico, R.; Ciavarella, D.; Lo Muzio, L.; Cervino, G.; Cicciù, M.; Laino, L. Rate of Relapse After Enucleation of Solid/Multicystic Ameloblastoma Followed by Piezoelectric or Conventional Peripheral Ostectomy. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2018, 29, e291–e293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rullo, R.; Festa, V.M.; Rullo, F.; Trosino, O.; Cerone, V.; Gasparro, R.; Laino, L.; Sammartino, G. The Use of Piezosurgery in Genioplasty. J. Craniofac. Surg. 2016, 27, 414–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, I.; Rozen, W.M.; Ramakrishnan, A.; Mirkazemi, M.; Baillieu, C.; Ptasznik, R.; Leong, J. Achieving adequate margins in ameloblastoma resection: The role for intra-operative specimen imaging. Clinical report and systematic review. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e47897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbate, V.; Togo, G.; Committeri, U.; Zarone, F.; Sammartino, G.; Valletta, A.; Elefante, A.; Califano, L.; Dell’Aversana Orabona, G. Full Digital Workflow for Mandibular Ameloblastoma Management: Showcase for Technical Description. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrovic, I.D.; Migliacci, J.; Ganly, I.; Patel, S.; Xu, B.; Ghossein, R.; Huryn, J.; Shah, J. Ameloblastomas of the mandible and maxilla. Ear Nose Throat J. 2018, 97, E26–E32. [Google Scholar]

- Sammartino, G.; Zarrelli, C.; Urciuolo, V.; di Lauro, A.E.; di Lauro, F.; Santarelli, A.; Giannone, N.; Lo Muzio, L. Effectiveness of a new decisional algorithm in managing mandibular ameloblastomas: A 10-years experience. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007, 45, 306–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiannis, C.; Mascolo, M.; Mignogna, M.D.; Varricchio, S.; Natella, V.; De Rosa, G.; Lo Giudice, R.; Galletti, C.; Paolini, R.; Celentano, A. Expression Profile of Stemness Markers CD138, Nestin and Alpha-SMA in Ameloblastic Tumours. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 3899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebeling, M.; Scheurer, M.; Sakkas, A.; Pietzka, S.; Schramm, A.; Wilde, F. BRAF inhibitors in BRAF V600E-mutated ameloblastoma: Systematic review of rare cases in the literature. Med. Oncol. 2023, 40, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proietti, I.; Skroza, N.; Michelini, S.; Mambrin, A.; Balduzzi, V.; Bernardini, N.; Marchesiello, A.; Tolino, E.; Volpe, S.; Maddalena, P.; et al. BRAF Inhibitors: Molecular Targeting and Immunomodulatory Actions. Cancers 2020, 12, 1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamat Yusof, M.N.; Ch’ng, E.S.; Radhiah Abdul Rahman, N. BRAF V600E Mutation in Ameloblastoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 2022, 14, 5593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Alagarsamy, R.; Chaulagain, R.; Singh, A.; Sapkota, D.; Thavaraj, S.; Singh, R.P. Does BRAF mutation status and related clinicopathological factors affect the recurrence rate of ameloblastoma? A systematic review, meta-analysis and metaregression. J. Oral Pathol. Med. 2023, 52, 895–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).