Abstract

Objectives: The aim of this meta-analysis was to determine the effects of respiratory muscle training (RMT) on functional ability, pain-related outcomes, and respiratory function in individuals with sub-acute and chronic low back pain (LBP). Methods: The study selection was as follows: (participants) adult individuals with >4 weeks of LBP; (intervention) RMT; (comparison) any comparison RMT (inspiratory or expiratory or mixed) versus control; (outcomes) postural control, lumbar disability, pain-related outcomes, pain-related fear-avoidance beliefs, respiratory muscle function, and pulmonary function; and (study design) randomized controlled trials. Results: 11 studies were included in the meta-analysis showing that RMT produces a statistically significant increase in postural control (mean difference (MD) = 21.71 [12.22; 31.21]; decrease in lumbar disability (standardized mean difference (SMD) = 0.55 [0.001; 1.09]); decrease in lumbar pain intensity (SMD = 0.77 [0.15; 1.38]; increase in expiratory muscle strength (MD = 8.05 [5.34; 10.76]); and increase in forced vital capacity (FVC) (MD = 0.30 [0.03; 0.58]) compared with a control group. However, RMT does not produce an increase in inspiratory muscle strength (MD = 18.36 [−1.61; 38.34]) and in forced expiratory volume at the first second (FEV1) (MD = 0.36 [−0.02; 0.75]; and in the FEV1/FVC ratio (MD = 1.55 [−5.87; 8.96]) compared with the control group. Conclusions: RMT could improve expiratory muscle strength and FVC, with a moderate quality of evidence, whereas a low quality of evidence suggests that RMT could improve postural control, lumbar disability, and pain intensity in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. However, more studies of high methodological quality are needed to strengthen the results of this meta-analysis.

1. Introduction

Currently, cognitive, emotional, and behavioral factors, such as pain catastrophizing and pain-related fear, contribute to the pathophysiology and chronicity of low back pain (LBP) [1,2]. This leads individuals with LBP to adopt safe-seeking practices and movement avoidance [3,4], causing the development of the “disuse syndrome”, which encompasses musculoskeletal decline, impaired coordination, motor control [1], and lumbar segmental instability [5]. Recent meta-analysis findings suggest that LBP reduces the ability to dissociate movement between the trunk and pelvis, increases lumbar paraspinal activation and stiffness, and impairs abdominal postural function [6]. Apart from its respiratory role, the diaphragm and abdominal muscles play a crucial part in spine stabilization [7]. Individuals with chronic LBP often experience diaphragm fatigue [8,9] and struggle to compensate for respiration-related postural sway [10]. Furthermore, the abdominal muscles and lumbar multifidus display a compromised core-stabilizing function, resulting in impaired postural control in individuals with LBP [11]. Therefore, there is a need to explore interventions that target the physical and psychological consequences of disuse syndrome in individuals with LBP.

Clinical practice guidelines highly recommend therapeutic exercise for the treatment of sub-acute and chronic LBP, given that exercise programs are effective in reducing pain and disability and in improving overall recovery, function, and health-related quality of life [12]. Respiratory muscle training (RMT) is a therapeutic exercise modality that improves inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength and respiratory muscle endurance [13]. Recent studies suggest RMT could improve the activation pattern [14] and thickness [15,16] of the diaphragm, transversus abdominis, and lumbar multifidus in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. RMT has been proven to reduce pain intensity [17] and improve respiratory muscle strength [17,18], physical function [17,18], balance [19], and consequently, the overall quality of life [17,18] in several population groups. Finally, recent research highlighted RMT could decrease sympathetic modulation [20], lowering pain intensity levels [21] and psychological distress [22]. Therefore, it seems that the benefits found by RMT in different populations would be of particular interest in individuals with subacute and chronic LBP.

Although several studies have investigated the effects of RMT in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP, no systematic review has pooled this evidence. This research is required to reveal whether RMT might have a positive effect on spinal control, respiratory function, and consequently, on LBP symptoms. Given that LBP is a high-burden disease, it is important for physicians and therapists to acquire a complete understanding of the effects of RMT on this population. The objective of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to determine the effects of RMT on functional ability, pain-related outcomes, and respiratory function in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP.

2. Materials and Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed the criteria of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [23].

2.1. Study Selection Criteria

The inclusion and exclusion of the reviewed studies relied on clinical and methodological aspects based on the population–interventions–comparison–outcomes of interest strategy [24] and was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42023387813).

Population: Individuals with >4 weeks of LBP (>3 pain on the visual analogue scale [VAS]) were selected to fit the established standards of sub-acute and chronic LBP [12]. No age or sex limitations were imposed. Data from participants with additional comorbidities were excluded.

Intervention and comparison: The experimental intervention required training the respiratory musculature in terms of strength and/or endurance. Studies employing threshold, resistive loading, or voluntary isocapnic hyperpnea devices and other methods to provide resistance to the respiratory musculature were included. Inspiratory muscle training (IMT), expiratory muscle training (EMT), or combined muscle training (IMT+EMT) modalities were included. Given that the comparisons should permit the extraction of the total effect attributable to RMT, the included studies had to compare RMT versus (1) passive control or (2) sham RMT (without sufficient intensity to generate a training effect). An additional standard intervention could be included if conducted under the same protocol in all study arms. A minimum training period of 4 weeks was required, given that this is the minimum period for physiological adaptations.

Outcomes: The outcomes of interest were as follows: functional ability as evaluated by postural control (center-of-pressure [CoP] path length) and lumbar disability (Athletes Disability Index, Oswestry Disability Index, and Roland–Morris Low Back Pain and Disability Questionnaire); pain-related outcomes measured in terms of pain intensity (VAS, numeric rating scale) and pain-related fear-avoidance beliefs (Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire or Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia [TSK]); and respiratory function as evaluated by measuring inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength (maximal inspiratory and expiratory pressure [MIP and MEP], forced vital capacity (FVC), forced expiratory volume at the first second (FEV1), and the FEV1/FVC ratio.

Study design: Only randomized controlled trials (RCTs) were included. Articles were included if they were published in English, Spanish, or Portuguese.

2.2. Search Strategy

The search strategy was performed following the guidelines of Russell-Rose et al. [25]. Searches were conducted in the MEDLINE, Web of Science, Scopus, PEDro, CINHAL, Science Direct, and CENTRAL electronic databases, with no date restrictions, up to 16 December 2022. The search string was adapted to each database, according to the data in Appendix S1. If clinical or methodological doubts arose from potential eligible studies, the authors were contacted by e-mail. Two independent reviewers conducted the search using the same methodology (RFG and IRM), and any discrepancies were resolved with the intervention of a third reviewer (ILUV).

2.3. Selection Criteria and Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers (RFG and IRM) screened the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the retrieved studies following the Cochrane recommendations [26]. After selecting potentially eligible, relevant, peer-reviewed papers, full-text copies were reviewed and checked as to whether they met the inclusion criteria and to identify and record the reasons for excluding the ineligible studies. Disagreements were resolved by consensus, including a third reviewer (ILUV). Relevant data were extracted for each included study (RFG and IRM).

2.4. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias Assessment

The PEDro scale was employed to assess the quality of the included trials because it is a reliable method for assessing RCT quality [27]. The total score for each study was stratified as follows: poor (<4 points), fair (4–5 points), good (6–8 points), and excellent (9–10 points) [28]. The risk of bias in each included study was assessed in accordance with the Cochrane recommendations, and a descriptive justification for the judgment was recorded following their guidelines [26]. In the “other bias” category, we clarified the specific criteria that could have affected the results. Detection bias was analyzed independently for objective physical variables and subjective patient-reported outcome measures.

Two independent trained assessors (RFG and IRM) examined the quality and risk of bias for the selected studies using the same methods, and disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consulting the third reviewer (ILUV). The inter-rater reliability was determined using the Kappa coefficient: >0.81–1.00 indicated excellent agreement between the assessors; 0.61–0.80 indicated good agreement; 0.41–0.60 indicated moderate agreement; and 0.21–0.40 indicated poor agreement [29].

2.5. Qualitative Analysis

The qualitative analysis was performed according to the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluation [30].

2.6. Data Analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with RStudio 3.0 software, employing the “meta” and “esc” packages. All significance tests were conducted at a level of 5%. A meta-analysis was performed only when data for the analyzed variables were represented in at least 3 trials.

To increase the accuracy and thus the generalizability of our analyses, multiple trials from several studies (e.g., CoP path length in overhead squat test and CoP path length in single-leg squat test) were included in all analyses. Regarding the post-intervention period, the mean difference and standard deviation (SD) values were extracted for each outcome. When necessary, the mean scores and SDs were estimated from graphs. When the trial reported only standard errors, they were converted to SD in accordance with the Cochrane recommendations [26].

The summary statistics for all analyses were presented using forest plots. The raw mean difference (MD) was used as the overall effect size if studies used the same unit/tool of measurement. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was employed as the overall effect size if studies used different units/tools of measurement. A random-effects model was employed in all analyses to determine the overall effect size. The effect size of the statistical significance of the overall SMD was examined using Hedges’ g and interpreted as follows: trivial effect (g < 0.20); small effect (g = 0.20–0.49); moderate effect (g = 0.50–0.79); and large effect (g ≥ 0.80). The confidence interval around the pooled effect was calculated using the Knapp–Hartung adjustments [31].

The degree of heterogeneity among the studies was estimated using Cochran’s Q test and the inconsistency index (I2) [32]. Heterogeneity was considered when Cochran’s Q test was significant (p < 0.1) and/or the I2 was >50% [33]. To help with the clinical interpretation of the heterogeneity, the prediction interval (PI) based on the between-study variance tau-squared (τ2) were reported. The PI estimates the true intervention effect that can be expected in future settings [34]. As recommended for continuous outcomes [35], the restricted maximum likelihood estimator was used to calculate the between-study variance τ2.

The possible influence of the studies on the results obtained in the meta-analysis, as well as their robustness, were assessed with an exclusion sensitivity analysis. To detect publication bias, the funnel plots were visually assessed, with an asymmetric graph considered to indicate the presence of bias. The Luis Fury Kanamori (LFK) index was employed as a quantitative measure to detect publication bias [36]: no asymmetry (LFK within ±1); minor asymmetry (LFK exceeding ±1 but within ±2); and major asymmetry (LFK exceeding ±2). If there was significant asymmetry, a small-study effect method was applied to correct for publication bias using the Duval and Tweedie trim-and-fill method [37].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

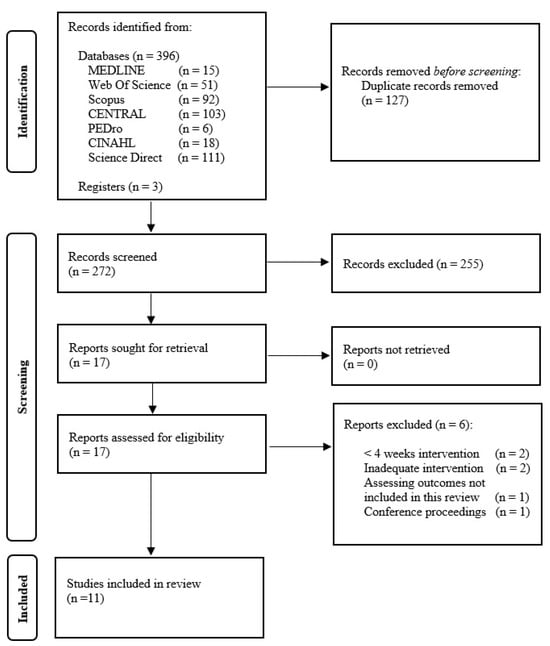

The search strategy yielded a total of 399 citations. After excluding articles not meeting the inclusion criteria, a total of 11 studies were selected for the final analysis. Figure 1 displays the flowchart of the search strategy.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Characteristics of the Included Studies

A total of 457 individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP (mean age 29.89 years) were included in the studies (Table 1). Only the study by Janssens et al. [38] compared an RMT intervention with a sham RMT. A strength training program (frequently oriented toward the lower back) was performed in all groups, with the experimental group additionally performing an RMT program in 10 studies [14,15,16,39,40,41,42,43,44,45]. Seven studies assessed IMT alone, employing threshold loading devices [14,15,38,40,41,45], except for the Park at al. [44] study, which used the therapist’s hands to offer inspiration resistance. Four studies assessed combined training (IMT+EMT) with resistive loading devices [16,39,42,43]. The studies that used a threshold loading device applied either progressive [14,40,45] or stable [15,38,41] loads between 50% and 90% of MIP, with 60% being the most commonly selected MIP [20,40,43]; the training intensity ranged from “difficult” to “slightly difficult” (<14 in rated self-perceived exertion) [16,39,42,43]. The training programs were implemented between 4 [16,39,42] and 8 weeks [14,15,38,40,41,45] for 2 [15,41] and 7 [14,38,40,45] times per week (Table 1). None of the studies reported serious adverse events.

Table 1.

Methodological characteristics and results of the included studies.

3.3. Methodological Quality and Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

The mean PEDro score of the included studies was 5.2 (range 4–6) (Appendix S2). The level of inter-evaluator agreement was high for inter-rater reliability (к = 0.895).

The risk of bias assessment of the included studies is summarized in Figure S1. In general, the risk of bias of the trials in the current meta-analysis was high. The highest risk of bias was found in the blinding of the outcome assessment and adequate stopping rules. However, all the included studies had an unclear risk of allocation concealment bias. The risk of bias in blinding the participants and assessors was judged low in all studies because the totality of the assessed studies adhered to strict protocols, a necessary requirement in exercise interventions to reduce the risk of differential behavior by the personnel delivering the intervention [46].

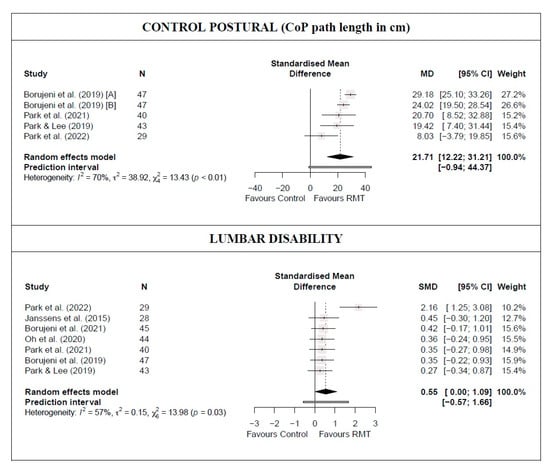

3.4. Functional Ability

There was low-quality evidence from four studies [39,42,43,45] that RMT produces a statistically significant increase in postural control (five trials; n = 159; MD = 21.71 cm [12.22; 31.21]), as well as a moderate and statistically significant decrease in lumbar disability (seven studies [16,38,39,40,43,45] [7 trials; n = 276]; SMD = 0.55 [0.001; 1.09]) compared with the control group (Figure 2 and Table 2). In both outcomes, heterogeneity was significant (I2 ≥ 57%) and the PI crossed zero; thus, future studies might find contradictory results. Based on the influence analyses, no single study significantly affected the overall MD in postural control. However, for the lumbar disability meta-analysis results, the study by Park et al. [43] was considered an outlier. The removal of this study still maintained the statistical significance of the estimated effect (small effect), reducing heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), and the PI did not cross zero (Figure 2 and Table 2), which will make the observed results more robust. Evidence of publication bias was detected in both outcomes (asymmetric funnel plot shape; major asymmetry for postural control [LFK index = −3.22]; and minor asymmetry for lumbar disability [LFK index = 1.67]; Figure S2). When the sensitivity analysis was adjusted for publication bias in both outcomes, there was no influence on the estimated effect because the trim-and-fill method considered that no studies should be added. Therefore, the initial results were maintained.

Figure 2.

Synthesis forest plot for postural control and lumbar disability for respiratory muscle training versus control group [16,38,39,40,42,43,45].

Table 2.

GRADE evidence profile for the effects of respiratory muscle training.

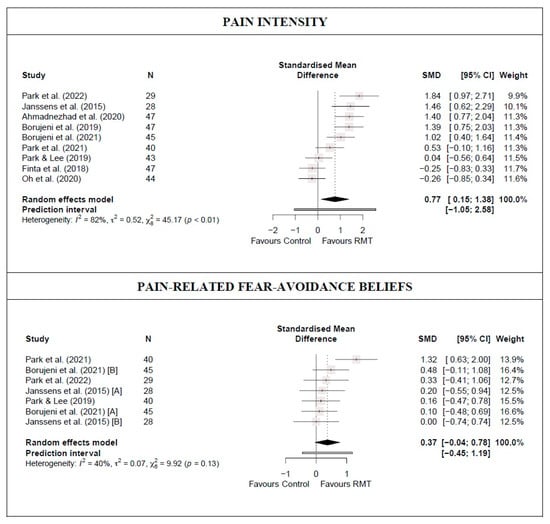

3.5. Pain-Related Outcome Intensity and Pain-Related Fear-Avoidance Beliefs

There was low-quality evidence from nine studies [14,15,16,38,39,40,42,43,45] (nine trials; n = 370) that RMT produces a moderate and statistically significant decrease in lumbar pain intensity compared with a control group (SMD = 0.77 [0.15; 1.38]; Figure 3 and Table 2). Heterogeneity was significant (I2 = 82%), and the PI crossed zero (−1.05; 2.58); thus, future studies might find contradictory results. Although no single study significantly affected the overall SMD, evidence of publication bias was detected (symmetric funnel plot shape; minor asymmetry [LFK index = 1.6]; Figure S3). When the sensitivity analysis was adjusted for publication bias, the initial results were maintained because the trim-and-fill method considered that no studies should be added.

Figure 3.

Synthesis forest plot for pain intensity and pain-related fear-avoidance beliefs for respiratory muscle training versus control group [14,15,16,38,39,40,42,43,45].

There was moderate-quality evidence from five studies [38,39,40,42,43] (seven trials; n = 182) that RMT shows no statistically significant difference in reducing pain-related fear-avoidance beliefs compared with a control group (SMD = 0.37 [−0.04; 0.78)]; Figure 3 and Table 2). Heterogeneity was not significant (I2 = 40%). No single study significantly affected the overall SMD, and no evidence of publication bias was detected (symmetric funnel plot shape; no asymmetry [LFK index = 0.97]; Figure S3).

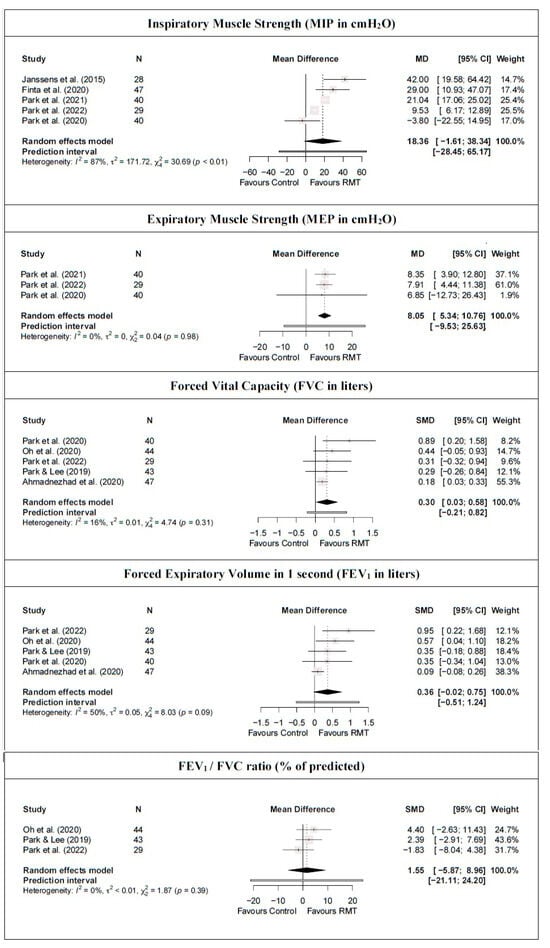

3.6. Respiratory Function

For respiratory muscle strength, the meta-analysis results showed that RMT statistically significantly increases expiratory muscle strength (moderate-quality evidence from three studies [42,43,44] [three trials; n = 109]; MD = 8.05 cmH2O [5.34; 10.76]) but not inspiratory muscle strength (low-quality evidence from five studies [38,41,42,43,44] [five trials; n = 184]; MD = 18.36 cmH2O [−1.61; 38.34]) compared with a control group (Figure 4 and Table 2). Heterogeneity was significant for MIP (I2 = 87%) but not for MEP (I2 = 0%). In addition, the PI crossed zero (−9.53; 25.63) in the MEP meta-analysis results; thus, future studies might find contradictory results. Based on the influence analyses, no single study significantly affected the overall MD in MEP. However, the leave-one-out analysis for MIP suggested that by removing the Park et al. [44] study, RMT showed a statistically significant increase with respect to the control group. Evidence of publication bias was detected in both outcomes (asymmetric funnel plot shape; major asymmetry for MIP [LFK index = 3.83] and MEP [LFK index = −2.71]; Figure S4). When the sensitivity analysis was adjusted for publication bias, the initial results were maintained because the trim-and-fill method considered that no studies should be added.

Figure 4.

Synthesis forest plot for respiratory muscle strength and pulmonary function for respiratory muscle training versus control group [14,16,38,39,41,42,43,44].

For pulmonary function, there was moderate-quality evidence that RMT produces a statistically significant increase in FVC compared with a control group (FVC: five studies [14,16,39,43,44] [five trials; n = 203], MD = 0.30 L [0.03; 0.58]) but not in FEV1 and the FEV1/FVC ratio (FEV1: five studies [14,16,39,43,44] [five trials; n = 203], MD = 0.36 L [−0.02; 0.75]; FEV1/FVC: three studies [16,39,43] [three trials; n = 116], MD = 1.55% [−5.87; 8.96]; Figure 4 and Table 2). Heterogeneity was not significant for any pulmonary function outcomes (I2 ≤ 50%). No single study significantly affected the overall MD of the FEV1/FVC ratio meta-analysis results. However, the removal of the study by Oh et al. [16], Park et al. [43], or Park and Lee [39] implies an absence of statistically significant differences in FVC between the RMT and control groups. Similarly, removing the study by Ahmadnezhad et al. [14] shows that RMT produces a statistically significant increase in FEV1. In addition, evidence of publication bias was detected for FVC and FEV1 (symmetric funnel plot shape; major asymmetry [LFK index ≥ 4.65]; Figure S4). When the sensitivity analysis of these variables was adjusted for publication bias, the trim-and-fill method considered that three studies should be added. However, there was no influence on the estimated effect because the initial results were maintained.

4. Discussion

The main findings of the present systematic review and meta-analysis suggest that RMT could improve MEP and FVC, with a moderate quality of evidence, whereas a low quality of evidence suggests that RMT could improve postural control, lumbar disability, and pain intensity in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. Given that the quality of the evidence supporting these findings is still low to moderate, more high-quality RCTs are required to confirm these trends.

Most individuals with LBP present altered motor control, impaired abdominal postural function [6], and lumbar segmental instability [5] partly due to the avoidance of movement. Lumbar stabilization is highly dependent on increased intra-abdominal pressure, which allows the unloading of the spine in weight-bearing and balance tasks without involving an excessive activation of the paraspinal muscles [38]. The main factor responsible for the increase in abdominal pressure is the co-contraction of the abdominal muscles [38]. This relationship between postural control and expiratory muscle strength was confirmed in this meta-analysis, in which both CoP path length and MEP improve after RMT in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. RMT could induce hypertrophy [15] and improved the recruitment pattern [14] of the abdominal muscles in individuals with chronic LBP, leading to a positive impact on lumbar stability.

Lumbar disability was significantly decreased by RMT in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. However, if one of the studies is excluded, the effect is not significant, which still reflects preliminary evidence. The most disabled individuals with chronic LBP were shown to demonstrate greater pain intensity, a longer duration of symptoms, more days off work, and poorer psychological well-being [47]. All these negative factors could be attenuated by RMT prescription and its subsequent disability reduction via greater abdominal stability and better neuromuscular function [48]. The Park et al. [43] study prescribed the longest intervention (5 weeks) and introduced significant heterogeneity in lumbar disability outcomes, which disappeared consistently when removed, confirming that RMT can improve lumbar disability in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP.

Although the stabilizing function of the diaphragm appears to be impaired in individuals with LBP [8,9], RMT has demonstrated positive effects in terms of diaphragm hypertrophy and activation [14,15,16]. The present review found no increases in inspiratory muscle strength after RMT in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP, but these results could have been negatively influenced by the validity of the RMT method employed in the Park et al. study [44] (therapist’s hands against the chest). The elimination of this study leads to significant improvements in MIP, which is consistent with prior literature [17,18] and is clinically meaningful [49].

The results of this review suggest that RMT, especially when combined with strength exercise, is more effective in reducing pain intensity than strength exercise alone in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. This result is supported by a recent meta-analysis that confirmed (1) the analgesic effect of physical exercise and (2) that high training volumes and the addition of co-interventions reduce functional limitations in individuals with chronic LBP [50]. The gradual exposure of patients to movements and exercises that they had feared justifyies the overall reduction in fear-avoidance beliefs in all intervention groups [51], explaining the lack of significant results between groups found by this review. Notably, variables related to pain catastrophizing were not evaluated in the included studies. We suggest that future research incorporate these measures for a more comprehensive and precise assessment.

RMT appears to improve MEP, but not MIP, in individuals with LBP. However, the exclusion of Park et al.’s [44] study leads to significant improvements in MIP, which is in line with the previous literature on this population [14,15,16]. Therefore, RMT is able to modify the maximum respiratory pressures, which may influence the coordination and position of the diaphragm, found to be altered in individuals with LBP favoring fatigability and the persistence of the symptomology of chronic LBP [8,9]. RMT can increase the force-producing abilities of the diaphragm and abdominal muscles [52], resulting in a greater expansion of the lungs and chest walls, leading to increased chest wall compliance and increased FVC. However, it is unlikely that RMT modifies FEV1, given that it is directly dependent on the airway condition rather than on effort [53].

Overall, RMT appears to be a beneficial intervention for improving pain intensity, postural control, and lumbar disability, positively impacting on functionality and the quality of life of individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. RMT can be applied simultaneously with core-strengthening and stabilization exercises [15,16,39,41,42,43], which makes it an inexpensive, effective, and feasible therapeutic approach for this population. The simplicity of RMT allows independent performance by the patient, allowing the minimal control required by healthcare professionals, reducing the need for healthcare resources, and providing economic savings. Clinicians should consider incorporating RMT as a complementary intervention for individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. However, more high-quality randomized controlled trials are needed to strengthen the level of evidence supporting the effectiveness of RMT in this population, which is still low. Future studies should also investigate the optimal frequency, intensity, duration, and type of RMT, as well as the potential long-term effects and the cost-effectiveness of this intervention. Additionally, the mechanisms underlying the benefits of RMT in individuals with LBP should be further explored.

The current study presents several limitations. The low-to-moderate quality of evidence found in the variables analyzed suggests that the results should be interpreted with caution. The training periodicity and intensity varied widely, and the RMT devices were not homogeneous, with threshold and resistive devices and therapist’s hands being examined in the included studies. The heterogeneity in the protocols hinders obtaining clear conclusions on the effectiveness of RMT in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP. The inclusion of individuals with sub-acute and chronic low back pain limits the generalizability of the findings to those with acute pain or other types of low back pain. Due to the limited number of studies included, it was impossible to perform subanalyses to address this clinical heterogeneity. The lack of long-term follow-up data in the included studies limits the ability to draw conclusions about the sustained effectiveness of RMT for sub-acute and chronic LBP. Future reviews should address these issues and more high-quality RCTs are required in different LBP populations.

5. Conclusions

The current systematic review and meta-analysis indicates that RMT could improve expiratory muscle strength and FVC in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP, with moderate-quality evidence. Low-quality evidence suggests that RMT could enhance postural control, reduce lumbar disability, and decrease pain intensity in the same population. The quality of the evidence supporting these findings presents room for improvement, and the heterogeneity of training protocols is still high. More high-quality RCTs are required to confirm the effects of RMT in individuals with sub-acute and chronic LBP.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/jcm13113053/s1, Appendix S1: Full search strategy; Appendix S2: PEDro scores for included studies (n = 11); Figure S1: Risk of bias summary and graph; Figure S2. Sensitivity and publication bias funnel plots for the comparison in postural control and lumbar disability; Figure S3: Sensitivity and publication bias funnel plots for the comparison in pain intensity and pain-related fear-avoidance beliefs; Figure S4: Sensitivity and publication bias funnel plots for the comparison in inspiratory and expiratory muscle strength, forced vital capacity, forced expiratory volume in 1 s, and ratio FEV1/FVC.

Author Contributions

I.L.-d.-U.-V. devised this project, the main conceptual ideas, investigation, methodology, and formal analysis. R.F.-G. and I.R.-M. performed data curation and wrote the original draft. T.d.C. and G.P.-M. supervised the manuscript writing and contributed to the final version of this manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Leeuw, M.; Goossens, M.E.J.B.; Linton, S.J.; Crombez, G.; Boersma, K.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S. The Fear-Avoidance Model of Musculoskeletal Pain: Current State of Scientific Evidence. J. Behav. Med. 2007, 30, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verbunt, J.A.; Sieben, J.M.; Seelen, H.A.M.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Bousema, E.J.; van der Heijden, G.J.; Knottnerus, J.A. Decline in physical activity, disability and pain-related fear in sub-acute low back pain. Eur. J. Pain 2005, 9, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fujii, R.; Imai, R.; Shigetoh, H.; Tanaka, S.; Morioka, S. Task-specific fear influences abnormal trunk motor coordination in workers with chronic low back pain: A relative phase angle analysis of object-lifting. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2022, 23, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osumi, M.; Sumitani, M.; Otake, Y.; Nishigami, T.; Mibu, A.; Nishi, Y.; Imai, R.; Sato, G.; Nagakura, Y.; Morioka, S. Kinesiophobia modulates lumbar movements in people with chronic low back pain: A kinematic analysis of lumbar bending and returning movement. Eur. Spine J. 2019, 28, 1572–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Sullivan, P.B. Masterclass. Lumbar segmental ‘instability’: Clinical presentation and specific stabilizing exercise management. Man. Ther. 2000, 5, 2–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Stabbert, H.; Bagwell, J.J.; Teng, H.L.; Wade, V.; Lee, S.P. Do people with low back pain walk differently? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Sport Health Sci. 2022, 11, 450–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodges, P.W.; Butler, J.E.; McKenzie, D.K.; Gandevia, S.C. Contraction of the human diaphragm during rapid postural adjustments. J. Physiol. 1997, 505, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janssens, L.; Brumagne, S.; McConnell, A.K.; Hermans, G.; Troosters, T.; Gayan-Ramirez, G. Greater diaphragm fatigability in individuals with recurrent low back pain. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 2013, 188, 119–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolář, P.; Šulc, J.; Kynčl, M.; Šanda, J.; Čakrt, O.; Andel, R.; Kumagai, K.; Kobesová, A. Postural function of the diaphragm in persons with and without chronic low back pain. J. Orthop. Sport. Phys. Ther. 2012, 42, 352–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimstone, S.K.; Hodges, P.W. Impaired postural compensation for respiration in people with recurrent low back pain. Exp. Brain Res. 2003, 151, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hides, J.; Stanton, W.; Dilani Mendis, M.; Sexton, M. The relationship of transversus abdominis and lumbar multifidus clinical muscle tests in patients with chronic low back pain. Man. Ther. 2011, 16, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qaseem, A.; Wilt, T.J.; McLean, R.M.; Forciea, M.A. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann. Intern. Med. 2017, 166, 514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Göhl, O.; Walker, D.J.; Walterspacher, S.; Langer, D.; Spengler, C.M.; Wanke, T.; Petrovic, M.; Zwick, R.-H.; Stieglitz, S.; Glöckl, R.; et al. Respiratory muscle training: State-of-the-Art. Pneumologie 2016, 70, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmadnezhad, L.; Yalfani, A.; Gholami Borujeni, B. Inspiratory Muscle Training in Rehabilitation of Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Sport Rehabil. 2020, 29, 1151–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finta, R.; Nagy, E.; Bender, T. The effect of diaphragm training on lumbar stabilizer muscles: A new concept for improving segmental stability in the case of low back pain. J. Pain Res. 2018, 11, 3031–3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oh, Y.-J.; Park, S.-H.; Lee, M.-M. Comparison of Effects of Abdominal Draw-In Lumbar Stabilization Exercises with and without Respiratory Resistance on Women with Low Back Pain: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2020, 26, e921295-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomas-Carus, P.; Biehl-Printes, C.; del Pozo-Cruz, J.; Parraca, J.A.; Folgado, H.; Pérez-Sousa, M.A. Effects of respiratory muscle training on respiratory efficiency and health-related quality of life in sedentary women with fibromyalgia: A randomised controlled trial. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2022, 40, 1119–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Medeiros, A.I.C.; Fuzari, H.K.B.; Rattesa, C.; Brandão, D.C.; de Melo Marinho, P.É. Inspiratory muscle training improves respiratory muscle strength, functional capacity and quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease: A systematic review. J. Physiother. 2017, 63, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferraro, F.V.; Gavin, J.P.; Wainwright, T.W.; McConnell, A.K. Association Between Inspiratory Muscle Function and Balance Ability in Older People: A Pooled Data Analysis before and after Inspiratory MUSCLE Training. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2022, 30, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Abreu, R.M.; Rehder-Santos, P.; Minatel, V.; dos Santos, G.L.; Catai, A.M. Effects of inspiratory muscle training on cardiovascular autonomic control: A systematic review. Auton. Neurosci. 2017, 208, 29–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlereth, T.; Birklein, F. The sympathetic nervous system and pain. Neuromolecular. Med. 2008, 10, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Morree, H.M.; Szabó, B.M.; Rutten, G.J.; Kop, W.J. Central nervous system involvement in the autonomic responses to psychological distress. Neth. Heart J. 2013, 21, 64–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Prisma Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Methley, A.M.; Campbell, S.; Chew-Graham, C.; McNally, R.; Cheraghi-Sohi, S. PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014, 14, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russell-Rose, T.; Chamberlain, J. Expert Search Strategies: The Information Retrieval Practices of Healthcare Information Professionals. JMIR Med. Inform. 2017, 5, e33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.; Sally, G. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Version 5.1.0; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2012; pp. 199–255. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, C.G.; Sherrington, C.; Herbert, R.D.; Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M. Reliability of the PEDro Scale for Rating Quality of Randomized Controlled Trials. Phys. Ther. 2003, 83, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhogal, S.K.; Teasell, R.W.; Foley, N.C.; Speechley, M.R. The PEDro scale provides a more comprehensive measure of methodological quality than the Jadad scale in stroke rehabilitation literature. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2005, 58, 668–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McHugh, M.L. Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012, 22, 276–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A.D.; Alderson, P.; Dahm, P.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Nasser, M.; Meerpohl, J.; Post, P.N.; Kunz, R.; et al. GRADE guidelines: 14. Going from evidence to recommendations: The significance and presentation of recommendations. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013, 66, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, G.; Hartung, J. Improved tests for a random effects meta-regression with a single covariate. Stat. Med. 2003, 22, 2693–2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bown, M.J.; Sutton, A.J. Quality Control in Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses. Eur. J. Vasc. Endovasc. Surg. 2010, 40, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IntHout, J.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; Rovers, M.M.; Goeman, J.J. Plea for routinely presenting prediction intervals in meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016, 6, e010247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veroniki, A.A.; Jackson, D.; Viechtbauer, W.; Bender, R.; Bowden, J.; Knapp, G.; Kuss, O.; Higgins, J.P.; Langan, D.; Salanti, G. Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 2016, 7, 55–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furuya-Kanamori, L.; Barendregt, J.J.; Doi, S.A.R. A new improved graphical and quantitative method for detecting bias in meta-analysis. Int. J. Evid. Based Healthc. 2018, 16, 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duval, S.; Tweedie, R. Trim and Fill: A Simple Funnel-Plot-Based Method of Testing and Adjusting for Publication Bias in Meta-Analysis. Biometrics 2000, 56, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janssens, L.; McConnell, A.K.; Pijnenburg, M.; Claeys, K.; Goossens, N.; Lysens, R.; Troosters, T.; Brumagne, S. Inspiratory muscle training affects proprioceptive use and low back pain. Med. Sci. Sport. Exerc. 2015, 47, 12–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.-H.; Lee, M.-M. Effects of a Progressive Stabilization Exercise Program Using Respiratory Resistance for Patients with Lumbar Instability: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Med. Sci. Monit. 2019, 25, 1740–1748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borujeni, B.G.; Yalfani, A.; Ahmadnezhad, L. Eight-Week Inspiratory Muscle Training Alters Electromyography Activity of the Ankle Muscles During Overhead and Single-Leg Squats: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J. Appl. Biomech. 2021, 37, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finta, R.; Boda, K.; Nagy, E.; Bender, T. Does inspiration efficiency influence the stability limits of the trunk in patients with chronic low back pain? J. Rehabil. Med. 2020, 52, jrm00038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Oh, Y.J.; Jung, S.H.; Lee, M.M. The Effects of Lumbar Stabilization Exercise Program Using Respiratory Resistance on Pain, Dysfunction, Psychosocial Factor, Respiratory Pressure in Female Patients in ’40s with Low Back Pain: Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann. Appl. Sport Sci. 2021, 9, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.-H.; Oh, Y.-J.; Seo, J.-H.; Lee, M.-M. Effect of stabilization exercise combined with respiratory resistance and whole body vibration on patients with lumbar instability: A randomized controlled trial. Medicine 2022, 101, e31843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.J.; Kim, Y.M.; Yang, S.R. Effects of lumbar segmental stabilization exercise and respiratory exercise on the vital capacity in patients with chronic back pain. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2020, 33, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borujeni, B.G.; Yalfani, A. Reduction of postural sway in athletes with chronic low back pain through eight weeks of inspiratory muscle training: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Biomech. 2019, 69, 215–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcot, O.; Boric, M.; Dosenovic, S.; Poklepovic Pericic, T.; Cavar, M.; Puljak, L. Risk of bias assessments for blinding of participants and personnel in Cochrane reviews were frequently inadequate. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2019, 113, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doualla, M.; Aminde, J.; Aminde, L.N.; Lekpa, F.K.; Kwedi, F.M.; Yenshu, E.V.; Chichom, A.M. Factors influencing disability in patients with chronic low back pain attending a tertiary hospital in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2019, 20, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, B.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, X.; Gong, D. Correlations between lumbar neuromuscular function and pain, lumbar disability in patients with nonspecific low back pain: A cross-sectional study. Medicine 2017, 96, e7991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakura, M.; Okura, K.; Kubota, M.; Sugawara, K.; Kawagoshi, A.; Takahashi, H.; Shioya, T. Estimation of minimal clinically important difference for quadriceps and inspiratory muscle strength in older outpatients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: A prospective cohort study. Phys. Ther. Res. 2021, 24, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayden, J.A.; Ellis, J.; Ogilvie, R.; Stewart, S.A.; Bagg, M.K.; Stanojevic, S.; Yamato, T.P.; Saragiotto, B.T. Some types of exercise are more effective than others in people with chronic low back pain: A network meta-analysis. J. Physiother. 2021, 67, 252–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Calderon, J.; Flores-Cortes, M.; Morales-Asencio, J.M.; Luque-Suarez, A. Conservative Interventions Reduce Fear in Individuals With Chronic Low Back Pain: A Systematic Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2020, 101, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Sarmiento, A.; Orozco-Levi, M.; Guell, R.; Barreiro, E.; Hernandez, N.; Mota, S.; Sangenis, M.; Broquetas, J.M.; Casan, P.; Gea, J. Inspiratory muscle training in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Structural adaptation and physiologic outcomes. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002, 166, 1491–1497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, S.S. Effect of effort versus volume on forced expiratory flow measurement. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 1988, 138, 1002–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).