Abstract

The presence of tinnitus does not necessarily imply associated suffering. Prediction models on the impact of tinnitus on daily life could aid medical professionals to direct specific medical resources to those (groups of) tinnitus patients with specific levels of impact. Models of tinnitus presence could possibly identify risk factors for tinnitus. We systematically searched the PubMed and EMBASE databases for articles published up to January 2021. We included all studies that reported on multivariable prediction models for tinnitus presence or the impact of tinnitus on daily life. Twenty-one development studies were included, with a total of 31 prediction models. Seventeen studies made a prediction model for the impact of tinnitus on daily life, three studies made a prediction model for tinnitus presence and one study made models for both. The risk of bias was high and reporting was poor in all studies. The most used predictors in the final impact on daily life models were depression- or anxiety-associated questionnaire scores. Demographic predictors were most common in final presence models. No models were internally or externally validated. All published prediction models were poorly reported and had a high risk of bias. This hinders the usability of the current prediction models. Methodological guidance is available for the development and validation of prediction models. Researchers should consider the importance and clinical relevance of the models they develop and should consider validation of existing models before developing new ones.

1. Introduction

Prediction models are made to inform clinical decision making. They quantify the relative importance of findings, characteristics and different types of factors when evaluating an individual patient [1]. Over the past decade, there has been a steep increase in the number of prediction models in clinical research. Before it can be decided whether models on tinnitus prediction could be applied in clinical care and research, more clarity regarding the quality, performance and outcomes of these models is necessary.

Tinnitus can be described as the hearing of a phantom sound. The sheer presence of tinnitus does not necessarily imply associated suffering. Quality of life is severely reduced in 0.5–1% of the population due to tinnitus [2]. Because of this, recently two operational definitions have been proposed to distinguish between the two: tinnitus and tinnitus disorder [3]. To measure the impact of tinnitus on daily life multi-item questionnaires are used in clinical practice such as the Tinnitus Functional Index (TFI), the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory (THI) and the Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ) or single-item questions [3,4,5,6].

Adequate prediction of the experience of tinnitus or the impact of tinnitus on daily life could be beneficial for preventive or therapeutic purposes. Prediction models on the impact of tinnitus on daily life could aid medical professionals to direct specific medical resources to those (groups of) tinnitus patients with specific levels of impact. Models on tinnitus presence could possibly identify risk factors for tinnitus. Through this, preventive measures could be taken to avoid the potential negative impact of tinnitus on daily life.

In prediction models, the patient specific value of each included factor is taken and combined to calculate risk estimates on the outcome for each individual. For adequate development of a clinically useful prediction model, three steps are needed. In the first step, the model is derived. This phase includes the identification of predictors, for which weights are obtained. Model validation is the second phase. During the development of a model, internal validation serves to assess and correct overfitting in the model. With external validation, the performance of the model is assessed in a different dataset. In the third and last phase, the model’s clinical impact is assessed by using the prediction rule as a decision rule [7]. In prognostic model development, it is advised that one should search, review, critically appraise and externally validate already existing prediction models before one starts to develop a new prediction model [7]. We aimed to systematically review the published prediction models of tinnitus presence and impact on daily life.

2. Materials and Methods

In this systematic review, we followed the Cochrane guidance for critical appraisal and data extraction for systematic reviews of prediction modelling studies (the CHARMS checklist) and the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) [8,9]. The protocol for this systematic review was registered at the international prospective register of systematic reviews (PROSPERO) with registration number CRD42021240493 [10].

2.1. Search Strategy

We searched the electronic literature databases of PubMed and EMBASE on the 21st of January 2021. The Ingui filter for finding studies on clinical prediction models was used in our search [11]. The search syntax can be found in Appendix A. In addition to the electronic database searches, reference lists were screened to identify additional studies. We searched for developmental as well as validation studies.

2.2. Study Selection/Eligibility Criteria

We included all studies that reported on multivariable prediction models. Multivariable models were defined as having two or more predictors included. Models were included when predicting the presence of tinnitus in adults or the effect of tinnitus on daily life. We included a broad range of outcomes to measure tinnitus-related effects on daily life. These included, but were not restricted to: tinnitus burden, tinnitus severity, tinnitus distress, tinnitus-associated quality of life, tinnitus-associated annoyance and tinnitus intrusiveness. These outcomes could be measured by using single-question and multiple-question questionnaires. We excluded letters to editors, reviews and animal studies. If articles reported multiple prediction models with a unique combination of predictors, we considered these as separate models.

We differentiated between articles reporting on the development and the external validation of studies. Articles were classified as developmental studies if the authors described the development of one or multiple models in their objectives or conclusions or if it was clear from other information (like information in the methods section) that a prediction model was developed in the study.

2.3. Screening Process

Two researchers (I.S., M.M.R.) independently screened the title and abstract of the articles for eligibility after removal of duplicates. Subsequently, the selected studies were reviewed for full text screening using predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved by discussion.

2.4. Data Extraction and Analysis

We created a data extraction form. This was based on the CHARMS checklist and previous research projects [9,12,13]. The following items were extracted from the included studies and included in the data extraction form: authors of the study, year of publication, journal of publication, the continent where the research was conducted, study design, study setting, instrument(s) used to measure the impact of tinnitus on daily life or tinnitus presence, the provided definition of tinnitus, percentage of patients with tinnitus in the study, mean impact of tinnitus on daily life measured with questionnaires or single questions, duration of tinnitus, number of research centres, number of participants, gender of the included patients, age of the included patients, horizon of prediction, number of predictor candidates, number of included predictor candidates in the final model, the number of predictor models, missing data, used statistical methods and the results of the prediction model. The data extraction form was triple checked by S.M.M.

2.5. Critical Appraisal (CAT)

The risk of bias (RoB) of the included studies was independently assessed by two researchers (M.M.R., I.S.) using the prediction model RoB assessment tool (PROBAST) [14]. The PROBAST tool consists of 20 signalling questions divided over four domains: participants, predictors, outcome and analysis. These domains were scored on RoB and applicability as low, high or unclear risk, based on the criteria that were provided by PROBAST [14]. PROBAST provided specific definitions for different domains to detect RoB. For example: the reasonable number of participants with a specific outcome relative to the number of candidate predictor candidates is defined as >20 (EPV >20) in model development studies. For the specific definition per domain and more explanation see: Moons et al. 2019: PROBAST: A tool to assess Risk of Bias and applicability of prediction model studies: Explanations and Elaboration [15]. Disagreements between the two researchers were solved by discussion.

2.6. Descriptive Analyses

The results of the data-extraction were summarized with descriptive statistics. No quantitative analyses were performed as this was beyond the scope of our study

3. Results

3.1. Search Results

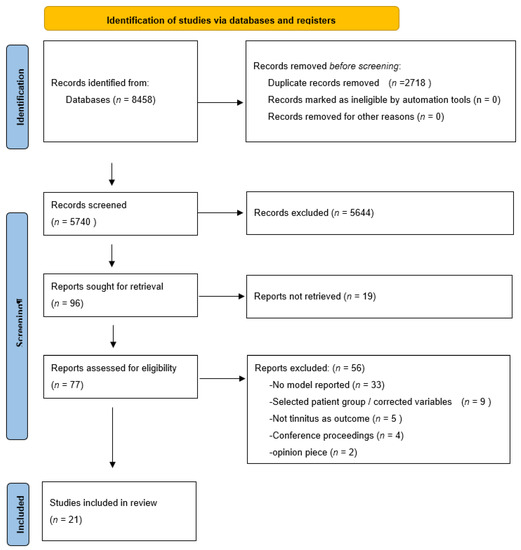

Our search yielded 3241 hits on PubMed and 5217 hits on EMBASE. After deduplication (n = 2718), we screened 5740 articles on title and abstract. Of those, we read the full text of 73 articles. One study was screened after cross referencing and was not included in the final selection. Based on the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria, we included 21 studies in this systematic review. Of those, 21 were developmental studies and 0 involved external validation of studies. (Figure 1: flowchart)

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

3.2. Developmental Studies

3.2.1. Study Design and Study Populations

The 21 developmental studies were published between 1999 and 2021. Of these, 71% took place in Europe. Fourteen out of the 21 studies reported on one prediction model. Dawes et al., Andersson 2005 et al. and Beukes et al. reported on three models [16,17,18] and four studies reported on two models [19,20,21,22]. Four studies were retrospective cohort studies [20,23,24,25], two studies were prospective cohort studies [21,26] and 13 studies had a cross sectional design [16,17,18,19,22,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. One had a nested case control design [36]. Twelve out of 21 studies were performed in a hospital setting at an outpatient clinic [17,18,20,22,23,24,25,26,29,30,32,35], seven studies were performed in the general population [16,19,21,27,28,31,34], one in a general practice setting and one in a combination of a hospital and the general population [33,36]. The number of participants per study varied between 44 and 168348. The reported mean age varied between 35.8 years and 69 years. The percentage of female participants ranged between 27.7% and 66.5%. The mean duration of tinnitus was reported in nine studies and ranged between 1.6 weeks and 12.5 years [17,18,20,22,24,25,26,29,32] (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Study characteristics.

3.2.2. Risk of Bias

Based on the criteria that were provided by PROBAST [14], the overall RoB was judged to be high in all studies, mainly due to a high RoB in the analysis domain. No studies accounted for overfitting, underfitting or optimism. No studies reported on relevant model performance measures. The RoB in the participants, predictor and outcome domain was low. Ten studies reported on a reasonable number of participants with the outcome [16,17,19,21,27,28,29,31,33,36], and for four studies no information on this account was provided [25,26,34,35]. Eight studies did not handle missing data appropriately [16,18,20,23,25,27,29,31], and thirteen studies did not provide any information on missing data [17,19,21,22,24,26,28,30,32,33,34,35,36]. The applicability of the participants, predictor and outcome domain was judged to be low (see Table 2: CAT).

Table 2.

Critical Appraisal of Topic (CAT).

3.2.3. Outcomes of Prediction Models

A total of 31 prediction models were described in the 21 included studies. Seventeen studies made a prediction model for the impact of tinnitus on daily life [17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35], three studies made a prediction model for tinnitus presence [21,28,36] and one study made models for both [16].

3.2.4. Tinnitus Impact

The impact of tinnitus on daily life was assessed by using different multi-items in 13 studies [17,18,20,22,23,25,26,27,29,31,32,33,35]. The THI was used in eight studies [20,22,23,26,27,29,32,33]. The TQ was used by two studies [20,35] and the psychological distress scale of the TQ was used by one study [25]. The mini Tinnitus Questionnaire (mTQ) was used in one study [31]. One study used the Tinnitus Reaction Questionnaire (TRQ) [17]. One study used the Klockhoff and Lindblom classification of tinnitus severity scale [24]. Three studies used single-item questionnaires to measure the impact of tinnitus [16,19,30]. The questions and answer possibilities used are reported in Table 3.

Table 3.

Studies with impact of tinnitus on daily life as outcome.

The reported mean THI scores varied between 38.3 and 48.3 points. Bhatt also used the THI but did not report the mean THI score [27]. Instead, they reported that 88.5% of the patients had a THI score <16, whereas 8.6% had a score >18. Beukes et al. did not report the mean TFI score, but subdivided the TFI score into three categories demonstrating that 10% had a score below 25 (mild tinnitus), 30% had a score between 25 and 50 (significant tinnitus) and 60% had a sore above 50 (severe tinnitus) [18]. Wallhauser-Franke et al. categorized outcomes of scores using the mTQ: 37.6% had a total score of seven or lower, 49% had a total score between 8 and 18, and 13.4% had a total score of 19 or higher [31]. Andersson (2005) used the TRQ and reported a mean of 37.4 [17]. The studies using single-item questionnaires reported ‘bothersome tinnitus’ with different definitions in 9.1–30.9% of the cases [16,19,28].

Predictors of Tinnitus Impact

The number of candidate predictors reported in the included studies varied between two and 70 [16,17,18,19,20,22,23,24,25,26,27,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. In three studies, the number and type of predictor candidates were not (clearly) reported and therefore the predictor candidates could not be extracted [25,26,34]. The five most common candidate predictors for tinnitus impact were: depression-related questionnaire scores (in 15 models), anxiety-related questionnaire scores (in 15 models), age (in 14 models), gender (in 9 models) and tinnitus duration (in 10 models) (Table 4/Appendix B).

Table 4.

Most frequently used predictor candidates and included predictors.

The number of final model predictors for impact models differed between two and 13. In the prediction models on the impact on daily life, scores of questionnaires in which depressive symptoms (n = 12) were assessed or symptoms of anxiety (n = 8) were most commonly used. In addition, age (n = 5), gender (n = 3), alcohol use (n = 2), smoking (n = 2), occupational noise exposure (n = 2), music noise exposure (n = 2), tinnitus duration (n = 2) and tinnitus location (n = 1) were used.

Modelling Method and Prediction Horizon in Tinnitus Impact Models

Multiple different modelling methods were used: Multiple linear regression [17,23], Stepwise multiple regression [20,25,32], multivariable adjusted regression [19], hierarchical linear multiple regression [18], ordinal logit regression [26], discriminant function analysis [24], linear regression [27], multiple regression [35], stepwise multiple linear regression [22], multiple ordinary least square regression analysis [29], stepwise forward regression analysis [30,33], multiple logistic regression, backward elimination with complex sampling [34], binary stepwise logistic regression [31], and multinomial logistic regression [16]. Only the studies by Dawes et al., Holgers et al. and Langebach et al. had a reporting horizon of, respectively, 4.2 years, 18 and 6 months [16,25,30]. All other studies were cross-sectional designs.

Model Presentation and Predictive Performance in Tinnitus Impact Models

All except Andersson 1999 et al. [24] and Andersson 2005 et al. [17] presented a regression slope, and two studies also presented a intercept [18,30]. Overall model performance was reported by the proportion of variance (R2) in eleven studies [17,18,19,20,23,24,25,27,31,33]. Holgers et al. used a probability regression plot [30]. The other studies did not report about predictive performance [22,26,28,29,35,37]. (Table 5)

Table 5.

Overall reported performance measures.

3.2.5. Tinnitus Presence

Tinnitus presence was assessed with different questions. The questions and answer possibilities used are reported in Table 4. In Kostev et al., tinnitus presence was defined using the first International Classification of Diseases (ICP) diagnosis of tinnitus [36]. Patients with ICP diagnosed tinnitus were matched 1:1 with persons without tinnitus. (Table 6). The presence of tinnitus reported in the four studies varied between 17.3% and 59% [16,21,28,36].

Table 6.

Studies with tinnitus presence as an outcome.

Predictors of Tinnitus Presence

The number of candidate predictors reported in the included studies varied between 16 and 125 [16,21,28,36]. The most common candidate predictors for tinnitus presence were: Gender (in 5 models), age (in 3 models) and occupational or music noise exposure (both in 3 models). In the final models the most commonly used predictors were gender (n = 3) followed by age (n = 2). (Table 4/Appendix B).

Modelling Method and Prediction Horizon in Tinnitus Presence Models

Multiple different modelling methods were used: logistic hierarchical regression [28], multinomial logistic regression [16], Stepwise multivariate logistic regression [36], multinomial logit regression model [21]. Only the study of Dawes et al. had a prediction horizon of respectively 4.3 years [16]. The other studies had a cross-sectional design.

Model Presentation and Predictive Performance in Tinnitus Presence Models

All studies presented a regression slope. Couth et al. reported an intercept [28]. Overall model performance was reported by proportion of variance (R2) by two studies [16,28]. Moore et al. [21] used the Akaike Information Criterion [37]. Kostev et al. did not report their predictive performance [36]. (Table 6)

3.3. Validation Studies

Zero studies were internally validated.

4. Discussion

In this systematic review, we presented the published prediction models on tinnitus presence, and the impact of tinnitus on daily life. We identified 21 different studies with a total of 31 models. Of these 31 models, five reported on tinnitus presence and 26 on the impact of tinnitus on daily life. For models of tinnitus presence, the most common predictors were age, gender and smoking. For models in which the impact of tinnitus of daily life was predicted, scores of depression-associated questionnaires and anxiety-associated questionnaires were the most common. Model performance was mostly reported by using the proportion of variance (R2).

Despite the high number of developed models, the quality of prognostic modelling in tinnitus research is low. To date, regrettably, no models have been validated. Due to the lack of validation and impact analyses, the models cannot be used in clinical care. None of the included models were tested for calibration and discriminative performance [38]. Earlier studies showed that the discriminative and calibration abilities of models which are based on small datasets with simple statistical methods are generally poor. The use of categorized instead of continuous data further lowers that performance [39]. Therefore, it is necessary that sufficient statistical methods are used in the context of prediction modelling [38].

Van Royen et al. recently described the difficulties of model adaptation to clinical care. The authors described four reasons why the adaptation of prediction models can fail [7]. The first reason is that models do not fit a clinical purpose, for example when a model includes a patient population that does not correspondent with the patient population in the clinic. A second reason is that the model is not validated, or reporting is incomplete. As demonstrated in this manuscript, this is applicable for the present tinnitus models. This makes it difficult for clinicians and researchers to further develop and use the models. The third reason is that there are difficulties with the implementation—for example, when the model has no impact on decision making, or when local or national regulations are a hindrance to the implementation. The last reason is failed model adaption. Examples include non-useful or non-trusted predictions, or outdated models. Most of these reasons seem to fit the tinnitus literature, whereby the lack of validation, lack of fitness for purpose due to different opinions about outcome measures, included populations and poorly reported models seem to be most prominent.

Collaboration between different research groups can lead to less accumulation or repeating of studies [40]. An improvement in tinnitus prediction research might be to improve and intensify these collaborations. Currently, there is still room for improvement. For example, many similar predictor candidates were used by the different models, of which only a minority are used in the final model. We noticed that tinnitus-specific variables and variables on somatic comorbidities are most frequently used as predictor candidates. However, only in about 25% of the models were the tinnitus specific variables used in the final models. This is in contrast to demographic factors and somatic or psychological comorbidities. These groups of variables tend to end up in the final model in about 50%. This raises the question of whether or not we should continue researching the predictive value of tinnitus-specific variables or put the scope on other domains of characteristics. This review might serve as a base for future research groups to critically assess which predictor candidates or predictors they should use, to improve prediction models’ performance and their application in clinical practice. The focus could then be shifted towards model validation, rather than more model development studies.

Prediction models aim to provide guidance in clinical decision making, and should therefore be handled with care by those who develop the models. In all these stages of prediction model development, clinical knowledge about the setting, patients and pathways should be combined with the statistical and methodological know-how of model development. Therefore, we advise researchers to develop prediction models in a collaborative effort involving clinicians, statisticians and epidemiologists. The use of reporting tools can also be a helpful next step in improving tinnitus prediction modelling. Guidance can further be found in the PROBAST statement, which can help with identifying the risk of bias in prognostic studies, whereas the TRIPOD statement is suitable for guidance in reporting [14,41]. As demonstrated in our study, the majority of studies based their model on statistical methods. However, it is recommended to build models based on clinical expertise and previous literature, rather than making them purely data driven [42]. Other ideas to improve the quality of future research are the use of prospective, large, population-based studies, and the consequent use of similar, validated, outcome measures such as the TFI [3]. This would help compare prediction models in meta-analyses, and would ease external validation. This might help to create clinically applicable prediction models.

5. Conclusions

We identified 21 different studies, which report a total of 31 models on either the presence or the impact of tinnitus on daily life. All included models were in the development stage. The reporting of the models was found to be poor and the risk of bias high. No studies regarding model validation or risk assessment were found. Knowing the impact prediction models can have on clinical decision making as well as on directing future research and policy making, we need to improve the quality of our prediction research. Better reporting of methods, collaboration between research groups and disciplines could aid future prediction model development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: M.M.R., I.S. and A.L.S. Investigation: M.M.R., S.M.M. and I.S. Methodology: M.M.R., I.S. and A.L.S. Writing—original draft preparation: M.M.R. and S.M.M. Writing—review and editing: M.M.R., S.M.M., I.S. and A.L.S. Supervision: I.S. and A.L.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Search strategy.

Table A1.

Search strategy.

| PubMed | (“Tinnitus”[Mesh] OR Tinnitus [tiab]) |

|---|---|

| AND | ((“Risk Factors”[Mesh] OR “Predictive Value of Tests”[Mesh] OR prediction model*[tiab] OR prediction rule*[tiab] OR decision support*[tiab] OR predictive model*[tiab] OR risk prediction*[tiab] OR risk scoring system*[tiab] OR scoring scheme*[tiab] OR risk assessment*[tiab] OR risk appraisal*[tiab] OR risk assessor*[tiab] OR risk calculation*[tiab] OR risk factor*[tiab] OR predict*[tiab] OR scoring system*[tiab]) OR ((Validat*[tiab] OR Predict*[tiab] OR Rule*[tiab]) OR (Predict*[tiab] AND (Risk*[tiab] OR Model*[tiab])) OR ((Criteria[tiab] OR Scor*[tiab]) AND (Predict*[tiab] OR Model*[tiab] OR Decision*[tiab] OR Prognos*[tiab]) OR (Decision*[tiab] AND (Model*[tiab] OR logistic models[mesh])) OR (Prognostic[tiab] AND (Criteria[tiab] OR Scor*[tiab] OR Model*[tiab])))) OR ((“Discrimination”[tiab] OR “Discriminate”[tiab] OR “c-statistic”[tiab] OR “c statistic”[tiab] OR “Area under the curve”[tiab] OR “AUC”[tiab] OR “Calibration”[tiab] OR “Algorithm”[tiab])))) OR (((tinnitus[Title/Abstract]) OR (tinnitus[MeSH Terms])) AND ((characterist*[Title/Abstract]) OR (risk*[Title/Abstract]))) |

| EMBASE | ‘Tinnitus’/exp OR Tinnitus :ti,ab,kw |

| AND | (‘risk factor’/exp OR ‘risk assessment’/exp OR ‘predictive value’/exp OR ‘prediction’/exp OR prediction model*:ti,ab,kw OR prediction rule*:ti,ab,kw OR decision support*:ti,ab,kw OR predictive model*:ti,ab,kw OR risk prediction*:ti,ab,kw OR risk scoring system*:ti,ab,kw OR scoring scheme*:ti,ab,kw OR risk assessment*:ti,ab,kw OR risk appraisal*:ti,ab,kw OR risk assessor*:ti,ab,kw OR risk calculation*:ti,ab,kw OR risk factor*:ti,ab,kw OR predict*:ti,ab,kw) OR (validat*:ti,ab,kw OR predict*:ti,ab,kw OR rule*:ti,ab,kw OR (predict*:ti,ab,kw AND (risk*:ti,ab,kw OR model*:ti,ab,kw)) OR ((criteria:ti,ab,kw OR scor*:ti,ab,kw) AND (predict*:ti,ab,kw OR model*:ti,ab,kw OR decision*:ti,ab,kw OR prognos*:ti,ab,kw)) OR (decision*:ti,ab,kw AND (model*:ti,ab,kw OR logistic) AND ‘models’/exp) OR (prognostic:ti,ab,kw AND (criteria:ti,ab,kw OR scor*:ti,ab,kw OR model*:ti,ab,kw) |

| OR | ((Tinnitus:ti,ab,kw OR ‘tinnitus’/exp) AND (characterist*:ti,ab,kw OR risk*:ti,ab,kw)) |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Used predictor candidates per study.

Table A2.

Used predictor candidates per study.

| Predictor Categories | Tinnitus Presence Studies | Impact on Daily Life Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | # used as predictor candidate for different (final) models | candidates | In final model | candidates | In final model | |

| Age | 6 | Couth 2019, Moore (2×), Dawes (1×) | Couth 2019, Dawes (1×) | Aazh, Basso 2020 (2×), Beukes 2020 (3×), Degeest 2016, Han 2019 (2×), Hesser 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×), Wallhauser 2012, Dawes (1×), Holgers 2005 | Basso 2020 (2×), Hesser 2016, Kim 2015, Dawes (1×) | |

| Gender | 5 | Couth 2019, Moore (2×), Dawes (1×) | Couth 2019, Dawes (1×) | Beukes 2020 (3×), Bhatt 2018 (1×), Degeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×), Wallhauser 2012, Dawes (1×) | Bhatt 2018 (1×), Kim 2015, Dawes (1×) | |

| Ethnicity | 2 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Bhatt 2018 (1×), | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | |

| SES | 2 | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | |

| Townsend Quartiel | 1 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | |||

| Marital Status | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Bruggemann 2016 | |||

| Employment | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×), Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Basso | |||

| Industry type (vs. finance) | ||||||

| Agricultural | 1 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | |||

| construction | 1 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | |||

| Music | 1 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | |||

| Income level | Holgers 2005 | |||||

| Educational level | 2 | Basso 2020 (2×), Hoekstra 2014 (2×), Holgers 2005 | Basso 2020 (2×), Hoekstra 2014 (1×) | |||

| Risk Factors | Alcohol use | 2 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Basso 2020 (2×), Dawes (2×), Holgers 2005 | Dawes (2×) |

| Smoking | 3 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Basso 2020 (2×), Bhatt 2018 (1×), Dawes (1×), Holgers 2005 | Bhatt 2018 (1×), Dawes (1×) | |

| Snus use | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Drug use | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Ototoxic medication | 3 | Couth 2019, Dawes (1×) | Couth 2019, Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | |

| Noise exposure | Loud noise exposure | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | |||

| Occupational noise exposure | 3 | Couth 2019, Moore (2×) | Couth 2019 | Dawes (2×) | Dawes (2×) | |

| Music noise exposure | 3 | Couth 2019, Moore (2×) | Couth 2019 | Dawes (2×) | Dawes (2×) | |

| Tinnitus specific | ||||||

| Pitch | 1 | Degeest 2016 | Andersson 1999 | |||

| Pitch (VAS) | 1 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Unterrainer 2003 | |||

| Tinnitus loudness | 2 | Bhatt 2018 (1×), Degeest 2016, Hesser 2016 | Bhatt 2018 (1×), Hesser 2016 | |||

| Loudness VAS | 4 | Aazh, Han 2019 (2×), Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Aazh (1×), Hoekstra 2014 (2×), Unterrainer 2003 | |||

| Duration | 2 | Beukes 2020 (3×), Bhatt 2018 (1×), Degeest 2016, Han 2019 (2×), Hoekstra 2014 (2×), Wallhauser 2012 | Bhatt 2018 (1×), Bruggemann 2016 | |||

| Variability in pitch and loudness | 1 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Hoekstra 2014 (1×) | |||

| How often is the tinnitus heard | Beukes 2020 (3×) | |||||

| Complex sound | 1 | Hesser 2016 | Hesser 2016 | |||

| Family history of tinnitus | 0 | Degeest 2016 | ||||

| Pulsatile | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | ||||

| Initial onset (gradual/abrupt) | 0 | Degeest 2016, Hoekstra (2×) Wallhauser 2012 | ||||

| Location | 1 | Beukes 2020 (3×), Degeest 2016, Han 2019, (2×) Hoekstra (2×), Walhauser 2012 | Wallhauser 2012 | |||

| Age at onset | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Type of tinnitus | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×), Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Number of sounds | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Tinnitus awareness | 2 | Degeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | |||

| Permanent awerenss | 1 | Wallhauser 2012 | Wallhauser 2012 | |||

| Tinitus awareness vas | 0 | Han 2019 (2×) | ||||

| Tinnitus presence (vas) | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Tinnitus annoyance (VAS) | 2 | Aazh, Han 2019 (2×) | Aazh, Han 2019 (1×) | |||

| Tinnitus effect on life (VAS) | 2 | Aazh, Han 2019 (2×) | Aazh, Han 2019 (1×) | |||

| Tinnitus Acceptance questionnaire | 1 | Hesser 2016 | Hesser 2016 | |||

| Change in perception over time | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Tinnitus changed significantly | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | ||||

| Working less because of tinnitus | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | ||||

| Tolerance in relation to onset | 1 | Andersson 1999 | ||||

| Influence on tinnitus | masking of tinnitus by environmental/external sounds | 0 | Degeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | |||

| Influence of head and neck movement | 0 | Degeest 2016 | ||||

| sounds distract or mask tinnitus | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | ||||

| Somatosensory modulation | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Tinnitus treatment | medication to help tinnitus or comorbidities | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | |||

| Previous tinnitus treatment | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | ||||

| Hearing loss | Hearing ability | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||

| Hearing related difficulties | 2 | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Degeest 2016, Wallhauser 2012, Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | |

| Hearing related difficulties in social situations | 2 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (2×) | |||

| Self-reported hearing loss | 1 | Beukes 2020 (3×), Bhatt 2018 (1×) | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | |||

| Presence of hearing loss | 0 | Han 2019 (2×) | ||||

| Hearing disability (HHIA-S) | 2 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | Beukes 2020 (2×) | |||

| Hearing aids | 1 | Beukes 2020 (3×), Degeest 2016, Wallhauser 2012 | Wallhauser 2012 | |||

| Hyperacusis | Hyperacusis subjective | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | |||

| Hyperacusis Questionnaire | 2 | Aazh, Beukes 2020 (3×), Degeest 2016 | Aazh, DeGeest 2016 | |||

| Subjective noise tolerance | 0 | Degeest 2016 | ||||

| Sound sensitivity | 1 | Hesser 2016 | Hesser 2016 | |||

| Sound level tolerance | 1 | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | |||

| Distortion of sound | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Audiological measures | ||||||

| PTA | 0 | DeGeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| PTA worse ear | 0 | Aahz | ||||

| PTA better ear | 0 | Aahz | ||||

| PTA (0.5,1,2 Hz) right ear | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| PTA (0.5,1,2 Hz) left ear | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| PTA (0.5,1,2 Hz) both ears | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| PTA (2,4,6 Hz) right ear | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| PTA (2,4,6 Hz) left ear | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| PTA (2,4,6 Hz) both ears | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| Hearing loss | 1 | Kim 2015 | ||||

| Speech perception | Speech in noise right ear | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| Speech in noise left ear | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| Speech in noise both ears | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| SRT better ear | 2 | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | |

| Loudness/Hyperacusis tests | average ULL in ear with lowest ULL | 0 | Aazh | |||

| Loudness discomfort Levels | 0 | Degeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Masking | MMI white noise | 0 | Degeest 2016 | |||

| MMI narrow band noise | ||||||

| Residual inhibition | 0 | Degeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Tinnitus | ||||||

| Loudness matchting | 0 | DeGeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Pitch matching | 0 | Degeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Audiometric maskability | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Minimal masking levels | 1 | Degeest 2016, Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Andersson 1999 | |||

| Comorbidities | Sleep | |||||

| Poor sleep quality | 2 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (2×) | |||

| Sleep problems | 1 | Wallhauser 2012 | Wallhauser 2012 | |||

| Insomnia (ISIS) | 3 | Aazh (1×), Beukes 2020 (3×) | Aazh, Beukes 2020 (2×) | |||

| Sleep disturbances | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Initial insomnia (van structrd tnitus interview) | 1 | Langebach 2005 (1×) | ||||

| Cardiovascular | Cardiovascular disease | 2 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) |

| Hypertension | 0 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||

| Hyperlipedemia | 2 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Kim 2015 | |

| Diabetes | 0 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||

| BMI | 1 | Couth 2019 | Couth 2019 | Holgers 2005 | ||

| Pain | ||||||

| Pain complaints | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Chronic pain | 1 | Wallhauser 2012 | Wallhauser 2012 | |||

| Fibromyalgia | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) | |||

| Chronic shoulder pain | 2 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (2×) | |||

| Ear | ||||||

| Vertigo | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Otalgia | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Ear fullness | 0 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | ||||

| Recurring ear infections | 1 | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | |||

| Dizziness | 0 | Wallhauser 2012 | ||||

| Morbus Meniere | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) | |||

| Neurological | Epilepsy | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Other | Asthma | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | |||

| Thyroid disease | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) | |||

| Metabolic risk | 2 | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Systematic lupus erythematosus | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Somatic complaints | 1 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Hoekstra 2014 (1×) | |||

| Migraine | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Osteoarthritis | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) | |||

| Somatic comorbidities | 0 | Wallhauser 2012 | ||||

| Health history | 1 | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | |||

| Comorbidity | 1 | Unterrainer 2003 | ||||

| Comorbidities psychological | ||||||

| Depression | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| HADS-D | 5 | Aazh, Andersson 2005 (3×), Hesser 2016 | Aazh, Andersson 2005 (3×), Hesser 2016 | |||

| BDI | 2 | Han 2019 (2×) | Han 2019 (2×) | |||

| PHQ9/15 | 2 | Beukes 2020 (3×), Wallhauser 2012 | Beukes 2020 (1×), Wallhauser 2012 | |||

| Algemeines depression skala (ADS) | 1 | Unterrainer 2003 | ||||

| Self reported depression and/or anxiety | 2 | Hoekstra 2014 (2×) | Hoekstra 2014 (2×), | |||

| Anxiety | Hads A | 5 | Aazh, Andersson 2005 (3×), Hesser 2016 | Aazh, Andersson 2005 (3×), Hesser 2016 | ||

| Generalized anxiety syndrome | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) | |||

| GAD | 1 | Beukes 2020 (3×), Wallhauser 2012 | Wallhauser 2012 | |||

| Panic disorder | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Agoraphobia | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Social anxiety | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Anxiety (SCL-90-R) | 1 | Langebach 2005 (1×) | ||||

| Stress | PTSS | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | |||

| Perceived Stress Questionnaire | 1 | Bruggemann 2016 | ||||

| Bepsi-K | 1 | Han 2019 (2×) | Han 2019 (1×) | |||

| traumatic/stressful experiences | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Stress | 1 | Kim 2015 | ||||

| Other | Burnout | 1 | Basso 2020 (2×) | Basso 2020 (1×) | ||

| Bipolar | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| Obsessive compulsive disorder | 0 | Basso 2020 (2×) | ||||

| PHQ15 | 0 | Wallhauser 2012 | ||||

| Diagnosed with a psychological condition | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | ||||

| ‘Avoidance of situations because of tinnitus’ | 1 | Andersson 1999 | ||||

| QoL | Satisfaction of life (SWLQ) | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | |||

| Cognition | cognitive failures (CFq) | 0 | Beukes 2020 (3×) | |||

| Other | Noise dose | 1 | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | Bhatt 2018 (1×) | ||

| Physical activity | 3 | Couth 2019, Dawes (1×) | Couth 2019, Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | |

| Neuroticism | 1 | Dawes (1×) | Dawes (1×) | |||

| Personality | Life satisfaction (freiburger personalitatinvntar) | 1 | Langebach 2005 (1×) | |||

| Five Big Personality dimensions scale | 1 | Strumila 2017 | Strumila 2017 | |||

| Internal Locus of control | 1 | Unterrainer 2003 | ||||

| external locus of control | 1 | Unterrainer 2003 | ||||

| Fatalistic externality | 1 | Unterrainer 2003 | ||||

| Perception of illeness | 1 | Unterrainer 2003 | ||||

| Perfectionism | concern over mistake | 3 | Andersson 2005 (3×) | Andersson 2005 (3×) | ||

| personal standards | 3 | Andersson 2005 (3×) | Andersson 2005 (3×) | |||

| parental expectations | 3 | Andersson 2005 (3×) | Andersson 2005 (3×) | |||

| parrental criticism | 3 | Andersson 2005 (3×) | Andersson 2005 (3×) | |||

| doubts about action | 3 | Andersson 2005 (3×) | Andersson 2005 (3×) | |||

| organisation | 3 | Andersson 2005 (3×) | Andersson 2005 (3×) | |||

| TSQ | 1 how much does tinnitus reduce the quality of life overall | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| 2. when you are in a quiet environment, but not trying to sleep, how much discomfort does your tinnitus cause | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| 3. how often do you notice tinnitus during your waking hours | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| 4. how often does tinnitus impair your concentratio, for example when reading | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| 5. how often is it difficult for you to go to sleep, and get back to sleep, due to tinnitus? | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| how often can you surpress or forget your tinnitus by some acitivy, for example watching TV or talking to somebody? | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| 7. if you are exposed to every day sounds, how easily do these sound reduce or drown you rtinnitus | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| 8. how often does tinnitus make you feel anxious or worried? | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| 9. how often does tinnitus makeyou feel tense or irritable? | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| 10. how often does tinnitus make you feel depressed and miserable? | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| Nottingham health profile (NHP) | emotional distrubances | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| sleep distrubances | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| energy | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| pain | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| physical mobility | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| social isolation | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| NHP Emotional disturbances | I feel that life is not worth living | 1 | Holgers 2005 | Holgers 2005 | ||

| Worry is keeping me awake at night | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I feel as if im losing control | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| Things are getting me down | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’ve forgotten what it’s like to enjoy myself | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I wake up feeling depressed | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I lose my temper easily these days | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| The days seem to drag | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m feeling on edge | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| NHP sleep disturbances | I lie awake for most of the night | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| I take tablets to help me sleep | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I sleep badly at night | 1 | Holgers 2005 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| It takes me a long time to get to sleep | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m waking up in the early hours of the morning | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| NHP energy | Everything is an effort | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| I’m tired all the time | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I soon run out of energy | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| NHP Pain | I’m in constant pain | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| I have unearable pain | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I have pain at night | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m in pain when I walk | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I find it painful to change position | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m in pain when I’m sitting | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m in pain when I’m standing | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m in pain when going up and down stairs | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| NHP Physical mobility | I am unable to walk at all | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| I find it hard to dress myself | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I need help to walk about outside | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I can only walk about indoors | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I find it hard to bend | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I have trouble getting up and down stairs | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I find it hard to stand for long | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I find it hard to reach for things | 0 | Holgers 2005 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| NHP social isolation | I feel I am a burden to people | 0 | Holgers 2005 | |||

| I feel lonely | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I feel there is nobody I am close to | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m finding it hard to make contact with people | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| I’m finding it hard to get on with people | 0 | Holgers 2005 | ||||

| International classification of disease 10th revision (ICD-10) | Diseases of the ear (diseases of middle ear and mastoid) [H65–H75] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| H65 Nonsuppurative otitis media | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| H66 Suppurative and unspecified otitis media | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| H68 Eustachian salpingitis and obstruction | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| Diseases of inner ear [H80–H83] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| H81.0 Menieres disease | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| H81.1 Benign paroxysmal vertigo | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| H81.2 Vestibular neuronitis | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| H81.9 Disorder of vestibular function, unspecified | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| Other disorders of ear [H90–H95] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| H91.9 presbycusis | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| H92 Otalgia and effusion of thee ar | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| Diseases of the upper respiratory tract (J30–J39) | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| J30 Allergic rhinitis | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| J31 Chronic rhinitis | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| J32 Chronic sinusitis | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| Mental disorders (organic, including symptomatic, mental disorders [F00–F09] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Mood [affective] disorders [F30–F39] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| F32, F33 Depression | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| Neurotic, stress-related, and somatoform disorders [F40–F48] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| F41 Anxiety disorder | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| F43 Reaction to severe stress, and adjustment disorders | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| F45 somatoform disorders | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| Diseases of the nervous system (extrapyramidal and movement disorders [G20–G26] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Other degenerative diseases of the nervous system [G30–G32] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Demyelinating diseases of the central nervous system [G35–G37] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Episodic and paroxysmal disorders [G40–G47] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| G43 migraine | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| Endocrine diseases (disorders of the thyroid gland [E00–E07] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus [E10–E14] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Diseases of the circulatory system (hypertensive diseases) [I10–I15] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Cerebrovascular diseases [I60–I69] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| Atherosclerosis [I70] | 2 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| I24, I25 coronary heart disease | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| other and unspecified disorders of the circulatory system [I95–I99] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| I95 hypotension | 1 | Kostev 2019 | Kostev 2019 | |||

| hemolytic anemias (nutritional anemias [D50–D53] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| hemolytic anemias [D55–D59] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

| aplastic and other anemias [D60–D64] | 0 | Kostev 2019 | ||||

# = total number.

References

- Reilly, B.M.; Evans, A.T. Translating clinical research into clinical practice: Impact of using prediction rules to make decisions. Ann. Intern. Med. 2006, 144, 201–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFerran, D.J.; Stockdale, D.; Holme, R.; Large, C.H.; Baguley, D.M. Why Is There No Cure for Tinnitus? Front. Neurosci. 2019, 13, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ridder, D.; Schlee, W.; Vanneste, S.; Londero, A.; Weisz, N.; Kleinjung, T.; Shekhawat, G.S.; Elgoyhen, A.B.; Song, J.J.; Andersson, G.; et al. Tinnitus and tinnitus disorder: Theoretical and operational definitions (an international multidisciplinary proposal). Prog. Brain Res. 2021, 260, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Newman, C.W.; Jacobson, G.P.; Spitzer, J.B. Development of the Tinnitus Handicap Inventory. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1996, 122, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meikle, M.B.; Henry, J.A.; Griest, S.E.; Stewart, B.J.; Abrams, H.B.; McArdle, R.; Myers, P.J.; Newman, C.W.; Sandridge, S.; Turk, D.C.; et al. The tinnitus functional index: Development of a new clinical measure for chronic, intrusive tinnitus. Ear Hear. 2012, 33, 153–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goebel, G.; Hiller, W. The tinnitus questionnaire. A standard instrument for grading the degree of tinnitus. Results of a multicenter study with the tinnitus questionnaire. HNO 1994, 42, 166–172. [Google Scholar]

- van Royen, F.S.; Moons, K.G.M.; Geersing, G.-J.; van Smeden, M. Developing, validating, updating and judging the impact of prognostic models for respiratory diseases. Eur. Respir. J. 2022, 60, 2200250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, K.G.M.; de Groot, J.A.H.; Bouwmeester, W.; Vergouwe, Y.; Mallett, S.; Altman, D.G.; Reitsma, J.B.; Collins, G.S. Critical appraisal and data extraction for systematic reviews of prediction modelling studies: The CHARMS checklist. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stegeman, I.; Rademaker, M.; Smit, D.A.L. Prediction Models for Tinnitus Presence and Tinnitus Severity: A Systematic Review. PROSPERO 2021 CRD42021240493. Available online: https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021240493 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Geersing, G.-J.; Bouwmeester, W.; Zuithoff, P.; Spijker, R.; Leeflang, M.; Moons, K.G.M. Search filters for finding prognostic and diagnostic prediction studies in Medline to enhance systematic reviews. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damen, J.A.A.G.; Hooft, L.; Schuit, E.; Debray, T.P.A.; Collins, G.S.; Tzoulaki, I.; Lassale, C.M.; Siontis, G.C.; Chiocchia, V.; Roberts, C.; et al. Prediction models for cardiovascular disease risk in the general population: Systematic review. BMJ 2016, 353, i2416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velde, H.M.; Rademaker, M.M.; Damen, J.; Smit, A.L.; Stegeman, I. Prediction models for clinical outcome after cochlear implantation: A systematic review. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 137, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, R.F.; Moons, K.G.M.; Riley, R.D.; Whiting, P.F.; Westwood, M.; Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Kleijnen, J.; Mallett, S.; PROBAST Group. PROBAST: A Tool to Assess the Risk of Bias and Applicability of Prediction Model Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moons, K.G.; Wolff, R.F.; Riley, R.D.; Whiting, P.F.; Westwood, M.; Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Kleijnen, J.; Mallett, S.; PROBAST Group. PROBAST: A Tool to Assess Risk of Bias and Applicability of Prediction Model Studies: Explanation and Elaboration. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 170, W1–W33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, P.; Newall, J.; Stockdale, D.; Baguley, D.M. Natural history of tinnitus in adults: A cross-sectional and longitudinal analysis. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e041290. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, G.; Airikka, M.-L.; Buhrman, M.; Kaldo, V. Dimensions of perfectionism and tinnitus distress. Psychol. Health Med. 2005, 10, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beukes, E.W.; Manchaiah, V.; Allen, P.M.; Andersson, G.; Baguley, D.M. Exploring tinnitus heterogeneity. Prog. Brain Res. 2021, 260, 79–99. [Google Scholar]

- Basso, L.; Boecking, B.; Brueggemann, P.; Pedersen, N.L.; Canlon, B.; Cederroth, C.R.; Mazurek, B. Gender-Specific Risk Factors and Comorbidities of Bothersome Tinnitus. Front. Neurosci. 2020, 14, 706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoekstra, C.E.L.; Wesdorp, F.M.; van Zanten, G.A. Socio-demographic, health, and tinnitus related variables affecting tinnitus severity. Ear Hear. 2014, 35, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, D.R.; Zobay, O.; Mackinnon, R.C.; Whitmer, W.M.; Akeroyd, M.A. Lifetime leisure music exposure associated with increased frequency of tinnitus. Hear Res. 2017, 347, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, T.S.; Jeong, J.-E.; Park, S.-N.; Kim, J.J. Gender Differences Affecting Psychiatric Distress and Tinnitus Severity. Clin. Psychopharmacol. Neurosci. 2019, 17, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aazh, H.; Lammaing, K.; Moore, B.C.J. Factors related to tinnitus and hyperacusis handicap in older people. Int. J. Audiol. 2017, 56, 677–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, G.; Lyttkens, L.; Larsen, H.C. Distinguishing levels of tinnitus distress. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied. Sci. 1999, 24, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Langenbach, M.; Olderog, M.; Michel, O.; Albus, C.; Köhle, K. Psychosocial and personality predictors of tinnitus-related distress. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 2005, 27, 73–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unterrainer, J.; Greimel, K.V.; Leibetseder, M.; Koller, T. Experiencing tinnitus: Which factors are important for perceived severity of the symptom? Int. Tinnitus J. 2003, 9, 130–133. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatt, I.S. Prevalence of and Risk Factors for Tinnitus and Tinnitus-Related Handicap in a College-Aged Population. Ear Hear. 2018, 39, 517–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couth, S.; Mazlan, N.; Moore, D.R.; Munro, K.J.; Dawes, P. Hearing Difficulties and Tinnitus in Construction, Agricultural, Music, and Finance Industries: Contributions of Demographic, Health, and Lifestyle Factors. Trends Hear. 2019, 23, 2331216519885571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesser, H.; Bånkestad, E.; Andersson, G. Acceptance of Tinnitus as an Independent Correlate of Tinnitus Severity. Ear Hear. 2015, 36, e176–e182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holgers, K.M.; Zöger, S.; Svedlund, K. Predictive factors for development of severe tinnitus suffering-further characterisation. Int. J. Audiol. 2005, 44, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallhäusser-Franke, E.; Brade, J.; Balkenhol, T.; D’Amelio, R.; Seegmüller, A.; Delb, W. Tinnitus: Distinguishing between subjectively perceived loudness and tinnitus-related distress. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degeest, S.; Corthals, P.; Dhooge, I.; Keppler, H. The impact of tinnitus characteristics and associated variables on tinnitus-related handicap. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2016, 130, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strumila, R.; Lengvenytė, A.; Vainutienė, V.; Lesinskas, E. The role of questioning environment, personality traits, depressive and anxiety symptoms in tinnitus severity perception. Psychiatr. Q. 2017, 88, 865–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.-J.; Lee, H.-J.; An, S.-Y.; Sim, S.; Park, B.; Kim, S.W.; Lee, J.S.; Hong, S.K.; Choi, H.G. Analysis of the prevalence and associated risk factors of tinnitus in adults. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, P.; Szczepek, A.J.; Rose, M.; McKenna, L.; Olze, H.; Mazurek, B. Impact of Multiple Factors on the Degree of Tinnitus Distress. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kostev, K.; Alymova, S.; Kössl, M.; Jacob, L. Risk Factors for Tinnitus in 37,692 Patients Followed in General Practices in Germany. Otol. Neurotol. 2019, 40, 436–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozdogan, H. Model selection and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC): The general theory and its analytical extensions. Psychometrika 1987, 52, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steyerberg, E.W.; Vickers, A.J.; Cook, N.R.; Gerds, T.; Gonen, M.; Obuchowski, N.; Pencina, M.J.; Kattan, M.W. Assessing the performance of prediction models: A framework for traditional and novel measures. Epidemiology 2010, 21, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steyerberg, E.W.; Uno, H.; Ioannidis, J.P.A.; van Calster, B. Poor performance of clinical prediction models: The harm of commonly applied methods. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2018, 98, 133–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glasziou, P.; Chalmers, I. Research waste is still a scandal—An essay by Paul Glasziou and Iain Chalmers. BMJ 2018, 363, k4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, G.S.; Reitsma, J.B.; Altman, D.G.; Moons, K.G.M. Transparent reporting of a multivariable prediction model for individual prognosis or diagnosis (TRIPOD): The TRIPOD statement. BMJ 2015, 350, g7594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wynants, L.; Van Calster, B.; Collins, G.S.; Riley, R.D.; Heinze, G.; Schuit, E.; Bonten, M.M.; Dahly, D.L.; Damen, J.A.; Debray, T.P.; et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of COVID-19: Systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ 2020, 369, m1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).