Abstract

This paper assesses the effects of percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) on pain- and function-related outcomes by means of a scoping review of studies with single cases, case-series, quasi-experimental, and randomized or non-randomized trial designs. We consulted the PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. Data were extracted by two reviewers. The methodological quality of studies was assessed using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale for experimental studies and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for case reports or cases series. Mapping of the results included: (1), description of included studies; (2), summary of results; and, (3), identification of gaps in the existing literature. Eighteen articles (five randomized controlled trials, one trial protocol, nine case series and three case reports) were included. The methodological quality of the papers was moderate to high. The conditions included in the studies were heterogeneous: chronic low back pain, lower limb pain after lumbar surgery, chronic post-amputation pain, rotator cuff repair, foot surgery, knee arthroplasty, knee pain, brachial plexus injury, elbow pain and ankle instability. In addition, one study included a healthy athletic population. Interventions were also highly heterogeneous in terms of sessions, electrical current parameters, or time of treatment. Most studies observed positive effects of PENS targeting nerve tissue against the control group; however, due to the heterogeneity in the populations, interventions, and follow-up periods, pooling analyses were not possible. Based on the available literature, PENS interventions targeting peripheral nerves might be considered as a potential therapeutic strategy for improving pain-related and functional outcomes. Nevertheless, further research considering important methodological quality issues (e.g., inclusion of control groups, larger sample sizes and comparatives between electric current parameters) are needed prior to recommending its use in clinical practice.

1. Introduction

Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (PENS) consists of the application of electric current through a solid filiform needle. The needle is inserted and ultrasound-guided until the tip of the needle is placed into musculoskeletal structures, but also nearby peripheral nerves to induce sensitive or motor stimulation with different therapeutic objectives [1]. This intervention is defined as a minimally invasive treatment and the US-guided use ensures patient safety with regard to avoiding adverse events derived from needling punctures of sensible tissues. Thus, it is a cost-effective intervention compared with pharmacological treatments or infiltrations [2]. The electrical current most commonly applied is biphasic, with different frequencies (ranging from 2–5 Hz or 80–100 Hz) and pulse widths (ranging from 250 to 500 ms), depending on the therapeutic objectives and effects desired [3,4].

It should be noted that there are several differences between PENS, neural PENS, TENS (transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) and electroacupuncture. For instance, TENS is characterized by the use of surface electrodes and no needles are used. However, its effectiveness has yet to be confirmed [5]. On the other hand, PENS targets peripheral nerves (neural PENS) or any other musculoskeletal structure to improve the patients’ symptomatology, while electroacupuncture is based on traditional Chinese medicine reasonings aiming specific points [4,5,6].

Although PENS was first described in 1952 [7], this therapeutic tool has been increasingly used for chronic pain management during the last 50 years [8,9], since this approach has been suggested to induce afferent input changes in the central nervous system (also known as the neuromodulation effect) [10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17]. In fact, previous studies have observed that PENS effectively reduced pain (either acute or chronic) [18,19,20] and also alleviate neuropathic pain conditions [16,21,22]. In addition, PENS has demonstrated other relevant applications, including the improvement of sports performance [17,23,24,25].

Scoping reviews are the most adequate method to examinate the current state of evidence regarding specific topics, to summarize the most relevant findings, to identify potential flaws providing novel guidelines for future research, to clarify concepts and to evaluate whether study designs are appropriate for future systematic reviews [26]. Therefore, it is a feasible alternative to other review designs (e.g., systematic reviews and meta-analyses) in those cases where reporting the meaningfulness or effectiveness of a therapeutic intervention is not possible [27]. Therefore, this scoping review aimed to map the existing literature regarding the effects of PENS targeting peripheral nerves on pain and function-related outcomes.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design

This scoping review will provide the readers with a broad overview of the existent literature on PENS targeting peripheral nerves, where the heterogeneity of methods and populations could be comprised. As recommended by Arksey and O’Malley [28], we first identified the research question, identified relevant studies on this topic, selected the studies, charted the data and, finally, collated, summarized and reported the results extracted from the studies. We followed the guidelines reported on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) [29]. This scoping review was prospectively registered on 17 May 2022 in the Open Science Framework (registration DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/64RVM).

2.2. Identifying the Research Question

The research question aimed to analyze the potential clinical utility of PENS interventions aimed peripheral nerves for improving pain or functional outcomes. Therefore, the research question was: “Is Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation that targeting peripheral nerves an effective intervention for improving pain and related-functions?”

2.3. Identifying the Relevant Studies

A literature search was conducted on three databases as recommended by Dhammi and Haq [30] up to 31 May 2022 in the PubMed, MEDLINE and EMBASE databases. After a first scanning, we also revised those articles referenced in the identified papers. Since not all journals are indexed in those databases, we manually screened the articles published in specific key journals. The search was conducted by two members of the research group with the assistance of an experienced health science librarian. Articles were filtered to those published in the English or Spanish languages, conducted in humans and including single case studies, case-series, quasi-experimental, and randomized or non-randomized clinical trials.

The search strategy combined the following terms using Boolean operators follows for all databases as follows (Table 1).

Table 1.

Database formulas during literature search.

2.4. Selecting the Studies

The PCC (Participants, Concept, Context) framework was followed to identify the main concepts:

Participants: Healthy participants or clinical populations with musculoskeletal pain.

Concept: Use of PENS targeting peripheral nerves.

Context: Evaluation of functional and pain-related changes after intervention

After a first screening, consisting of a first title and abstract reading, a full-text read of the remaining studies was conducted. In case of discrepancies between both reviewers, a third author would be asked to make a determination.

2.5. Charting the Data

Data extraction was conducted with a data charting form as recommended by Arkesy and O’Malley [28], providing a standardized summary of the results for each article included in the scoping review. All data were extracted by two authors including the authors’ information, year of publication, population, sample size, intervention details and pain or functional outcomes assessed [31]. Again, both authors had to achieve consensus on each item and in case of disagreement, a third author would provide a final decision.

2.6. Mapping the Data

After data extraction, we mapped the literature thematically, providing a description of the identified and included studies, a summary of the results and, finally, identifying gaps in the existing literature.

2.7. Methodological Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of all studies was assessed by both authors using the Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale [32] for experimental studies and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) tool for case reports [33].

The PEDro scale is widely used to assess the methodological quality of experimental trials and includes 11 items. The first item, although is not included in the score, is related to external validity. The following 10 items are used to calculate the final score (ranging from 0 to 10 points), evaluating the random allocation, concealed allocation, similarity at baseline, subject blinding, therapist blinding, assessor blinding, lost follow-up, intention-to-treat analysis, between-group statistical comparison, and point/variability measures for at least one key outcome. Total scores between 0 and 3 are considered “poor”, 4 and 5 as “fair”, 6 and 8 are considered “good”, and 9 and 10 are “excellent” for this scale [32].

The methodological quality of case series and case reports was assessed using the JBI tool [33,34]. The critical appraisal of case reports assesses whether the studies describe the patient’s demographic characteristics, the patient’s history, the clinical condition of the patient, the diagnostic tests and results, the interventions, post-clinical conditions and adverse events, and if there is any key lesson learned from the exposed case, in an eight-item scale with Yes/No/Unclear possible answers for each item [33]. On the other hand, the JBI tool used for assessing the methodological quality of case series considers whether the studies described the inclusion criteria, if measurement tools were standard, valid and reliable, consecutive inclusion, completed inclusion of participants, reported the demographics and clinical information of participants, described the outcomes, presented the sites and clinics demographic information and statistical analyses were appropriate on a 10-point scale [34].

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection

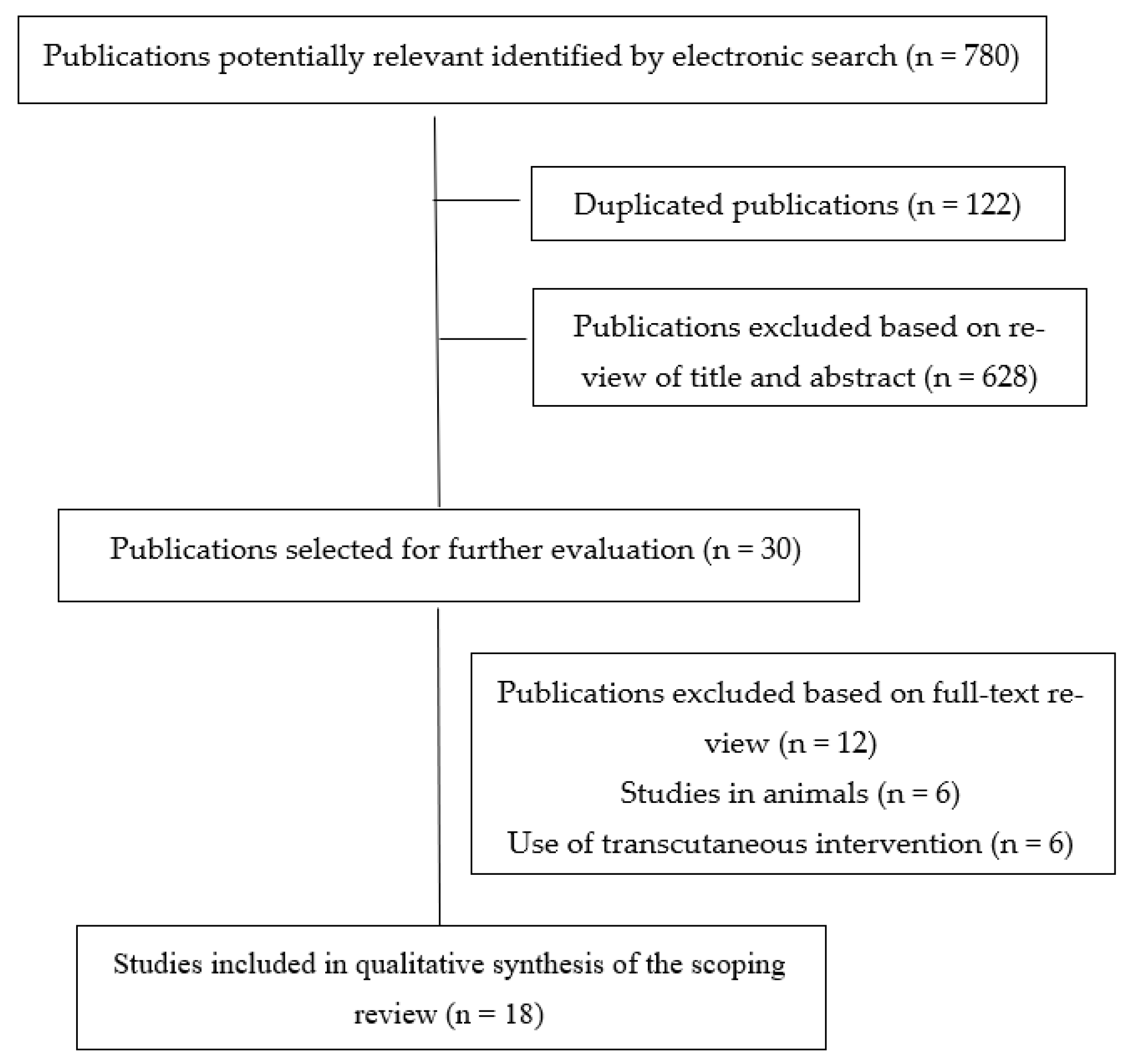

Our electronic search resulted in 780 potential studies being included in this scoping review. After removing duplicates (n = 122) and those not meeting the first filter (n = 628), the full view text of 30 studies was conducted. After extensive reading, 12 studies were excluded. Therefore, a total of eighteen (n = 18) studies [10,11,12,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] were included in the literature data mapping (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) flow diagram.

3.2. Study Designs

All experimental studies were published in the last five years (from 2019). From six experimental studies, five were randomized controlled trials [11,36,37,47,49] and one was a trial protocol [12] reporting no results. Thus, nine studies were case series [10,35,39,41,42,43,45,46,48] and three articles described case reports [38,40,44].

3.3. Methodological Quality

The methodological quality assessment of the experimental studies is reported in Table 2. Scores ranged from 4 to 8 with a mean value of 6.5 ± 1.5 points. The most repeated flaw was the lack of intention to treat analysis [11,12,36,37,49]. On the other hand, all the studies considered a random allocation.

Table 2.

Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro) scale for assessing the methodological quality of the studies included.

The methodological quality assessment of case reports is reported in Table 3. The only three case reports found during the review had a methodological quality score of 7 out of 8 points, this being the lack of adverse events description, which was the only flaw found in all of the studies [38,40,44,45].

Table 3.

JIB tool for assessing the methodological quality of case reports.

Finally, the methodological quality assessment of case series is summarized in Table 4. All studies assessed the conditions with standard and reliable tools, used valid methods for identifying the condition, clearly reported the outcomes during the follow-up period and clearly reported the sites’ demographic information. The most constant flaw was the absence of consecutive inclusion of participants. In fact, only one study provided this information [43].

Table 4.

JIB tool for assessing the methodological quality of case series.

3.4. Summarizing Findings

The characteristics of the participants in the included studies are reported in Table 5. The total sample consisted of 257 patients (139 men, 128 women) with recruited samples ranging from single case reports [38,44] to clinical trials including 80 subjects [36].

Table 5.

Data extraction of the studies included in the scoping review.

Pain conditions were heterogeneous and included patients with chronic lower back pain [10,43,46], lower limb pain after lumbar surgery [38], chronic post-amputation pain [11], musculoskeletal impairments after unilateral rotator cuff repair [35], foot surgery [39] and knee arthroplasty [48], reduced hamstring flexibility [36], unilateral anterior knee pain [37,42], brachial plexus injury [40], lateral elbow pain [44] and ankle instability [45]. In addition, one study included a healthy athletic population [47].

Interventions were also heterogeneous in terms of sessions (Cohen et al. [10] programmed a 6-month intervention, 6 h per day while De-la-Cruz-Torres et al. [35] performed a single intervention of 1.5 min of duration), nerves targeted (medial branches of dorsal spinal ramus [10,43,46], femoral nerve [11,37,41,42,47,48], sciatic nerve [11,12,36,39,48], brachial plexus [12,35], peroneal nerve [38], radial nerve [40,44,49], tibial nerve [45]) and follow-up periods (ranging from post-intervention [42] to 2 years [44]). Regarding the electric parameters set among the studies, two therapeutic strategies could be differentiated. Half of the studies set approximately 100 Hz of frequency, 0.2 to 20 mA of amplitude and 15 to 200 μs pulse duration [10,11,35,39,41,48], while the other half set <10 Hz of frequency and 250 μs pulse duration [36,37,42,43,44,45,46,47,49].

Finally, the most assessed outcomes were pain intensity [10,11,12,35,37,38,39,40,41,43,44,46,48,49], range of movement [36,37,39,48], disability [43,44,46,49], medication intake [12,41,46], strength [42], stiffness [36], quality of life [40], body balance [45], morphological nerve changes [49] and sports performance [47]. Most studies observed positive effects of the intervention against the control group; however, due to the heterogeneity in the populations, interventions, and follow-up periods, pooling analyses were not possible.

4. Discussion

Although a previous meta-analysis analyzing the efficacy of PENS in pain-related outcomes has been published [5], this is the first scoping review focusing on pain and functional changes when PENS is specifically applied targeting the peripheral nerves.

4.1. Literature Mapping

Despite the short lifetime of this novel therapeutic approach, multiple pain conditions benefited from the use of PENS targeting peripheral nerve tissue. The most widely assessed conditions were chronic low back pain (three articles, all of them with a case series design [10,43,46]) and unilateral anterior knee pain (two articles, a randomized clinical trial [37] and a case series [42]). Even though one of the most important discussions is currently whether the frequency, duration, intensity and pulse width may induce different effects, none of the studies compared two different modalities of PENS in the same article.

Although previous studies have reported the mechanisms behind high-frequency and low-frequency currents (regarding the activation of endogenous opioid receptors) supporting the different peripheral antinociceptive responses depending on the stimulation received [5], three studies reported similar improvements in low back pain intensity and disability in the mid-term [43] and long-term [10,46]. However, it should be noted that previous studies analyzing the effects of electric current parameters on sensory variables were mostly focused on mechano-sensitivity indicators (e.g., pressure pain thresholds) instead of clinical self-reported pain intensity. While pain experience is highly subjective and a complex experience influenced by several factors [50], local responses dependent of electrical current parameters may produce changes in primary or secondary hyperalgesic areas [5].

Regarding the efficacy of PENS targeting peripheral nerves in populations with unilateral anterior knee pain, both studies used similar current parameters [37,42] and assessed pain-related (in the study conducted by García-Bermejo et al. [37]) and physical conditioning (in the study conducted by Álvarez-Prats et al. [42]) outcomes. In both cases, the studies showed significant changes compared with the baseline in terms of maximal isometric strength of the quadriceps, range of movement, pain intensity and disability in the short term.

Comparison between studies for the rest of the conditions including lower limb pain after lumbar surgery [38], chronic post-amputation pain [11], musculoskeletal impairments after unilateral rotator cuff repair [35], foot surgery [39] and knee arthroplasty [48], reduced hamstring flexibility [36], brachial plexus injury [40], lateral elbow pain [44] and ankle instability [45] was not possible as only one study was found for each condition. However, in general all studies reported good results in the short, middle and long term after PENS interventions targeting peripheral nerves.

Finally, the experimental studies including a comparative group were also heterogeneous. For instance, Garcia-Bermejo et al., [36] compared the effects of a single PENS intervention between clinical and healthy populations (with comparable effects between groups) while Gallego-Sendarrubias et al., [47] compared the inclusion of PENS as a complementary intervention to a training program in a sample of semiprofessional soccer players without symptoms. While the effects of PENS seem to be similar in both the clinical and healthy populations, the inclusion of this technique demonstrated additional improvements in the short-term regarding sports performance. However, in the mid-term these differences are not significant.

4.2. Strengths and Limitations of the Review

The results from this scoping review should be interpreted according to its potential strengths and limitations. Strengths of this scoping review include a comprehensive literature search, methodological rigor, data extraction, and the inclusion of studies (experimental studies, case reports and case series) of moderate to high methodological quality. However, some potential limitations are also present. First, despite the high number of studies initially identified, only a relatively small number (n = 17) were finally included in the review, since the remaining paper was a proposed protocol. The most important issue was the heterogeneity in the conditions, nerves targeted, outcomes and populations included. Second, most studies are from the same research teams. Third, most of the studies had a design with no control groups and limited samples, which limits the clinical application or the real effectiveness of this intervention. As has been previously stated, studies investigating the efficacy of PENS targeting different peripheral nerves, in different clinical conditions and assessing different outcomes (i.e., pain intensity, function, sports performance, muscle strength, muscle stiffness, range of movement or balance, for mentioning some), should be conducted to further elucidate whether this intervention could be recommended in specific conditions. In addition, further studies should consider the comparison between different current modalities in the short-, middle- and long-term in order to provide clinicians with guidelines based on adequate scientific evidence.

5. Conclusions

This scoping review analyzed the efficacy of PENS intervention targeting peripheral nerves on pain-related and functional outcomes in both clinical and asymptomatic populations. The results were highly heterogeneous in terms of conditions assessed, outcomes measured, follow-up periods, study designs, electric current parameters, samples, intervention programs, number of sessions and nerves targeted. Based on the available literature, PENS interventions targeting peripheral nerves might be considered as a potential therapeutic strategy for improving pain-related and functional outcomes. Nevertheless, further research considering important methodological quality issues (e.g., inclusion of control groups, larger sample sizes and comparatives between electric current parameters) are needed prior to recommending its use in clinical practice.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, all authors.; methodology, A.G.-C.; software, A.G.-C.; validation, all authors; formal analysis, A.G.-C. and J.A.V.-C.; investigation, all authors; resources, J.L.A.-B.; data curation, A.G.-C. and J.A.V.-C.; writing—original draft preparation, all authors; writing—review and editing, all authors; visualization, all authors; supervision, J.L.A.-B.; C.F.-d.-l.-P.; project administration, C.F.-d.-l.-P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data derived from this study is reported in this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Minaya Muñoz, F.; Valera Garrido, F. (Eds.) Neuromodulación percutánea ecoguiada. In Fisioterapia Invasive, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Barcelona, Spain, 2016; pp. 283–294. [Google Scholar]

- Dunning, J.; Butts, R.; Henry, N.; Mourad, F.; Brannon, A.; Rodriguez, H.; Young, I.; Arias-Buría, J.L.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C. Electrical dry needling as an adjunct to exercise, manual therapy and ultrasound for plantar fasciitis: A multi-center randomized clinical trial. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernández, J.V.L.; Martín-Pintado-Zugasti, A.; Frutos, L.G.; Alguacil-Diego, I.M.; de la Llave, A.I.; Fernandez-Carnero, J. Immediate and short-term effects of the combination of dry needling and percutaneous TENS on post-needling soreness in patients with chronic myofascial neck pain. Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2016, 20, 422–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kawakita, K.; Okada, K. Mechanisms of Action of Acupuncture for Chronic Pain Relief—Polymodal Receptors Are the Key Candidates. Acupunct. Med. 2006, 24, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza-Manzano, G.; Gómez-Chiguano, G.F.; Cleland, J.A.; Arías-Buría, J.L.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Santana, M.N. Effectiveness of percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for musculoskeletal pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Pain 2020, 24, 1023–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, W.; Wand, B.M.; O’Connell, N.E. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2017, 9, CD011976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ketterl, W.; Kierse, H.; Tischler, R. A new electromedical method to control pain in preparation of dental cavities; electroanalgesia with oscillator by MACH method. Zahnarztl. Rundsch. 1952, 61, 498–502. [Google Scholar]

- White, J.C.; Sweet, W.H. Pain and the neurosurgeon: A forty-year experience. JAMA 1969, 210, 1766. [Google Scholar]

- Steude, U. Percutaneous Electro Stimulation of the Trigeminal Nerve in Patients with Atypical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Neurochirurgia 1978, 21, 66–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Gilmore, C.; Kapural, L.; Hanling, S.; Plunkett, A.; McGee, M.; Boggs, J. Percutaneous Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for Pain Reduction and Improvements in Functional Outcomes in Chronic Low Back Pain. Mil. Med. 2019, 184 (Suppl. S1), 537–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmore, C.; Ilfeld, B.; Rosenow, J.; Li, S.; Desai, M.; Hunter, C.; Rauck, R.; Kapural, L.; Nader, A.; Mak, J.; et al. Percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation for the treatment of chronic neuropathic postamputation pain: A multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2019, 44, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilfeld, B.M.; Plunkett, A.; Vijjeswarapu, A.M.; Hackworth, R.; Dhanjal, S.; Turan, A.; Cohen, S.P.; Eisenach, J.C.; Griffith, S.; Hanling, S.; et al. Percutaneous Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (Neuromodulation) for Postoperative Pain: A Randomized, Sham-controlled Pilot Study. Anesthesiology 2021, 135, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, T.; Gargya, A.; Singh, H.; Sivanesan, E.; Gulati, A. Mechanism of Peripheral Nerve Stimulation in Chronic Pain. Pain Med. 2020, 21 (Suppl. S1), S6–S12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakovlev, A.; Karasev, S.A.; Resch, B.E.; Yakovleva, V.; Strutsenko, A. Treatment of a typical facial pain using peripheral nerve stimulation. Neuromodulation 2011, 14, 553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McRoberts, W.P.; Cairns, K. A Retrospective Study Evaluating the Effects of Electrode Depth and Spacing for Peripheral Nerve Field Stimulation in Patients with Back Pain. In Proceedings of the 14th Annual Meeting of North American Neuromodulation Society—Neuromodulation: Vision 2010, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2–5 December 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, M.; Decarolis, G.; Liberatoscioli, G.; Iemma, D.; Nosella, P.; Nardi, L.F. A Novel Mini-invasive Approach to the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain: The PENS Study. Pain Physician 2016, 19, E121–E128. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rozand, V.; Grosprêtre, S.; Stapley, P.J.; Lepers, R. Assessment of Neuromuscular Function Using Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 103, e52974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reverberi, C.; Dario, A.; Barolat, G. Spinal Cord Stimulation (SCS) in Conjunction with Peripheral Nerve Field Stimulation (PNfS) for the Treatment of Complex Pain in Failed Back Surgery Syndrome (FBSS). Neuromodulation 2013, 16, 78–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Rizvi, S. Historical and Present State of Neuromodulation in Chronic Pain. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2014, 18, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, R.L.; Lee, W.C. One-shot percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation vs. transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation for low back pain: Comparison of therapeutic effects. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2002, 81, 838–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopsky, D.J.; Ettema, F.W.L.; Van Der Leeden, M.; Dekker, J.; Stolwijk-Swüste, J.M. Percutaneous Nerve Stimulation in Chronic Neuropathic Pain Patients due to Spinal Cord Injury: A Pilot Study. Pain Pract. 2014, 14, 252–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, Y.; Kamibeppu, T.; Nishii, R.; Mukai, S.; Wakeda, H.; Kamoto, T. Ct Evaluation of Acupuncture Needles Inserted into Sacral Foramina. Acupunct. Med. 2016, 34, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, B.; Ereline, J.; Gapeyeva, H.; Pääsuke, M. Posttetanic Potentiation in Knee Extensors after High-Frequency Submaximal Percutaneous Electrical Stimulation. J. Sport Rehabil. 2005, 14, 249–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Requena, B.; Gapeyeva, H.; Ereline, J.; Pääsuke, M. Acute effect of percutaneous electrical stimulation of knee extensor muscles on isokinetic torque and power production performance. Isokinet. Exerc. Sci. 2007, 15, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regina Dias Da Silva, S.; Neyroud, D.; Maffiuletti, N.A.; Gondin, J.; Place, N. Twitch potentiation induced by two different modalities of neuromuscular electrical stimulation: Implications for motor unit recruitment. Muscle Nerve 2015, 51, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; McEwen, S.A. A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhammi, I.K.; Haq, R.U. How to Write Systematic Review or Metaanalysis. Indian J. Orthop. 2018, 52, 575–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement. Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moseley, A.M.; Elkins, M.R.; Van der Wees, P.J.; Pinheiro, M.B. Using research to guide practice: The Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro). Braz. J. Phys. Ther. 2019, 24, 384–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moola, S.; Munn, Z.; Tufanaru, C.; Aromataris, E.; Sfetcu, R. Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020; Chapter 7. [Google Scholar]

- Munn, Z.; Barker, T.H.; Moola, S.; Tufanaru, C.; Stern, C.; McArthur, A.; Stephenson, M.; Aromataris, E. Methodological quality of case series studies: An introduction to the JBI critical appraisal tool. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2127–2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilfeld, B.M.; Iv, J.J.F.; Gabriel, R.A.; Said, E.T.; Nguyen, P.L.; Abramson, W.B.; Khatibi, B.; Sztain, J.F.; Swisher, M.W.; Jaeger, P.; et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation: Neuromodulation of the suprascapular nerve and brachial plexus for postoperative analgesia following ambulatory rotator cuff repair. A proof-of-concept study. Reg. Anesthesia Pain Med. 2019, 44, 310–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De-La-Cruz-Torres, B.; Carrasco-Iglesias, C.; Minaya-Muñoz, F.; Romero-Morales, C. Crossover effects of ultrasound-guided percutaneous neuromodulation on contralateral hamstring flexibility. Acupunct. Med. 2021, 39, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Bermejo, P.; De-La-Cruz-Torres, B.; Romero-Morales, C. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Neuromodulation in Patients with Unilateral Anterior Knee Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira-Dos-Santos, G.; Hurdle, M.F.B.; Gupta, S.; Clendenen, S.R. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Peripheral Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Lower Extremity Pain: A Rare Case Report. Pain Pract. 2019, 19, 861–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilfeld, B.M.; Gabriel, R.A.; Said, E.T.; Monahan, A.M.; Sztain, J.F.; Abramson, W.B.; Khatibi, B.; Finneran, J.J.; Jaeger, P.T.; Schwartz, A.K.; et al. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Peripheral Nerve Stimulation: Neuromodulation of the Sciatic Nerve for Postoperative Analgesia Following Ambulatory Foot Surgery, a Proof-of-Concept Study. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2018, 43, 580–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.H.; Shin, S.H.; Lee, Y.R.; Lee, H.S.; Chon, J.Y.; Sung, C.H.; Hong, S.J.; Lee, J.Y.; Moon, H.S. Ultrasound-guided peripheral nerve stimulation for neuropathic pain after brachial plexus injury: Two case reports. J. Anesth. 2017, 31, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilfeld, B.M.; Said, E.T.; Finneran, J.J.; Sztain, J.F.; Abramson, W.B.; Gabriel, R.A.; Khatibi, B.; Swisher, M.W.; Jaeger, P.; Covey, D.C.; et al. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Peripheral Nerve Stimulation: Neuromodulation of the Femoral Nerve for Postoperative Analgesia Following Ambulatory Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Proof of Concept Study. Neuromodulation 2019, 22, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Prats, D.; Carvajal-Fernández, O.; Pérez-Mallada, N.; Minaya-Muñoz, F. Changes in Maximal Isometric Quadriceps Strength after the Application of Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Neuromodulation of the Femoral Nerve: A Case Series. J. Invasive Tech. Phys. Ther. 2019, 2, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanmartin-Enriquez, F.; Valera-Garrido, F.; Álvarez-Prats, D.; Carvajal-Fernández, O. Ultrasound-Guided percutaneous neuromodulation in non-radiating low back pain. J. Invasive Tech. Phys. Ther. 2019, 2, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Arias-Buría, J.L.; Cleland, J.A.; El Bachiri, Y.R.; Manzano, G.P.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation of the Radial Nerve for a Patient with Lateral Elbow Pain: A Case Report with a 2-Year Follow-up. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 2019, 49, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodríguez-Rosal, M.; Sánchez-Sixto, A.; Álvarez-Barbosa, F.; Yáñez-Álvarez, A. Effect of ultrasound-guided percutaneous neuromodulation in ankle instability: A case study. J. Invasive Tech. Phys. Ther. 2019, 2, 100–101. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore, C.A.; Kapural, L.; McGee, M.J.; Boggs, J.W. Percutaneous Peripheral Nerve Stimulation (PNS) for the Treatment of Chronic Low Back Pain Provides Sustained Relief. Neuromodulation 2019, 22, 615–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallego-Sendarrubias, G.; Arias-Buría, J.; Úbeda-D’Ocasar, E.; Hervás-Pérez, J.; Rubio-Palomino, M.; Fernández-De-Las-Peñas, C.; Valera-Calero, J. Effects of Percutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation on Countermovement Jump and Squat Performance Speed in Male Soccer Players: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilfeld, B.M.; Gilmore, C.A.; Grant, S.A.; Bolognesi, M.P.; Del Gaizo, D.J.; Wongsarnpigoon, A.; Boggs, J. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation for analgesia following total knee arthroplasty: A prospective feasibility study. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2017, 12, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De-La-Cruz-Torres, B.; Abuín-Porras, V.; Navarro-Flores, E.; Calvo-Lobo, C.; Romero-Morales, C. Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Neuromodulation in Patients with Chronic Lateral Epicondylalgia: A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 4877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Úbeda-D’Ocasar, E.; Valera-Calero, J.; Hervás-Pérez, J.; Caballero-Corella, M.; Ojedo-Martín, C.; Gallego-Sendarrubias, G. Pain Intensity and Sensory Perception of Tender Points in Female Patients with Fibromyalgia: A Pilot Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).