Abstract

Important advancements in the development of novel materials and designs have led to the creation of advanced mineral membranes with high packing densities and enhanced competitiveness in relation to polymeric and classic mineral membranes. Olive juice represents an underutilised source of phenolic and secoiridoid antioxidants, in which industrial valorisation is hindered by some technical limitations, particularly the effective removal of suspended solids during processing. The efficiency of two recrystallized silicon carbide-based microfiltration membranes with an equivalent industrial filtration packing density of 782 m2/m3 was evaluated. One of them had nominal pore sizes of 500 nm and was made of mixed oxides and the other had nominal pore sizes of 200 nm and was made of α-Al2O3. The 500 nm membrane demonstrated superior filtration flux and faster processing compared to the 200 nm membrane, though both achieved complete removal of suspended solids. A greater workload of the 500 nm membrane resulted in a progressive irreversible fouling, caused by the smallest-sized suspended particles and macromolecular colloids. Particle size had a greater impact on fouling than particle load. Both membrane treatments induced a spontaneous increase in the concentrations of up to 24 phenolic, secoiridoid and secoiridoidyl phenylethanoid conjugates. This effect can be considered as an additional benefit of the thus clarified olive juices. Further investigations are warranted to elucidate the underlying mechanisms driving these transformations.

1. Introduction

Olive juice refers to the aqueous phase (vegetation water) derived from a recently obtained, fresh olive paste during olive oil production using 3-phase centrifugal decanters. It typically contains 3–15% suspended solids and 3.5–15% dissolved molecules and ions, including mono-, oligo- and polysaccharides, proteins, phenolic and secoiridoid compounds, secoiridoidyl phenylethanoid conjugates, polyols, oligocarboxylic acids, minerals, residual oils, lipids [1] and a diverse variety of microorganisms [2,3] native to the olive growing area. Some of these molecules are highly reactive, others act as catalysts (enzymes), and many are nutrients that support microbial activity resulting in an important chemical and microbial instability of the juice. Only juices that retain their original molecular composition can be considered of high value, primarily due to their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antibacterial properties [1,4]. The term ‘olive juice’ was introduced to replace the term ‘vegetation waters’, because it shares the same origin and morphology as other fruit juices. This terminology serves to differentiate a recently obtained olive juice (within 24 h after olive crushing), maintained under hygienic conditions from non-preserved olive juices, commonly known as olive mill wastewater (OMWW) or alpechín. The same criteria apply to intermediate products generated during olive oil production, such as wet pomace (alpeorujo or alperujo), collected from 2-phase centrifugal decanters, and pomace (orujo), collected from 3-phase centrifugal decanters. Similarly, the terms ‘semi-skimmed fluid olive paste’ (or fresh wet olive pomace) and ‘semi-skimmed firm olive paste’ are exclusively assigned to fresh pastes derived from healthy olives that are crushed, kneaded and kept under hygienic conditions for a maximum of 24 h after centrifugation. This distinction differentiates them from olive meal wastes (OMW) generated when identical pastes are stored in ponds or tanks at uncontrolled conditions, leading to their decomposition and oxidation. It is important to note that the general terms ‘wet pomace’ or ‘pomace’ do not differentiate between their intact (fresh) and degraded (rotten) state, nor do they account for differences in their water content (60–75% and 50–55%, respectively). Therefore, the adoption of distinct terms, such as ‘semi-skimmed fluid’ or ‘semi-skimmed firm’ olive pastes is necessary for their consideration as intermediate products of the olive oil production industry.

The preservation of the functional properties of both olive juice and semi-skimmed pastes requires immediate processing following malaxation. Delays beyond 24 h can lead to substantial degradation of these intermediate products [1]. In the absence of prompt transformation, the aqueous fraction of the paste is rapidly converted into OMWW. This effluent is characterized by a high chemical and biological oxygen demand (up to 320 and 132 g/L, respectively), which poses important environmental management challenges, which are reviewed with high rigor in [5]. To mitigate the generation of OMWW, over 95% of Spanish olive oil mills have transitioned from 3- to 2-phase centrifugal decanters in recent decades. This operational shift, while eliminating a separate liquid waste stream at the mills, yields the single, very humid by-product: wet pomace which combines the classic (firm) olive pomace and OMWW. The extraction of the residual 1–2% of olive pomace oil, has been consequently centralized in the specialized processing plants known as extractors of olive pomace oil [6]. The recovery of this residual oil is an energy-intensive process that requires the evaporation of the high water content from the wet pomace to dryness. The drying process is conducted in trommel-type dryers by direct contact of the wet pomace with combustion fumes [7]. This operation produces sticky tar and very humid gases that clog any gas purification system and lead to substantial atmospheric pollution [8]. Therefore, the strategic shift to resolve the issue of liquid waste at olive oil mills has transferred the primary environmental burden to atmospheric emissions at the olive pomace oil extraction facilities.

A potential solution to the energy and atmospheric pollution issues associated with 2-phase processing is a return to 3-phase extraction, allowing for the separate management of firm olive pomace and OMWW. However, the viability of this approach is contingent upon developing a large-scale, sustainable valorization strategy for OMWW, a challenge that remains largely confined to laboratory-scale research rather than industrial applications. The primary technical barrier is the inherent instability of the olive juice which requires immediate preservation or post-extraction processing. This requirement implies the implementation of on-line treatment systems that operate continuously throughout the 3-month olive harvesting season and a paradigm shift from viewing OMWW as a waste to treating it as a co-product. Consequently, the effective utilization of olive juice is a critical factor in resolving the broader energy and environmental challenges facing the olive oil industry. In any valorization scenario, the initial steps of fine clarification and microbial stabilization are indispensable prerequisites. These processes are crucial for converting the raw effluent into stable intermediate or value-added end products. Furthermore, the complete removal of suspended solids is an essential requirement for the application of advanced biorefinery technologies, such as the molecular separation techniques described by Federici et al. [9].

At present, pressure-driven microfiltration (MF) and ultrafiltration represent the most efficient unit operations for the simultaneous removal of suspended solids and microorganisms from suspensions in a single step [10]. Among these techniques, mineral ultra-thin film composite monolithic membranes have gained increasing attention due to their enhanced mechanical, chemical and thermal stability, extended operational lifespan, effective cleaning, and reduced fouling tendencies, with respect to polymeric membranes [11,12]. However, a notable technical limitation of these membranes lies in the relatively large-diameter of their flow channels (typically 4–8 mm), which results in broad hydraulic cross-sections. Consequently, high-power pumps are required to sustain the necessary turbulent recirculation flows, leading to increased energy consumption. To address this challenge, a major focus of advanced ceramic membrane development over the past two decades has been the decrease in flow channel diameters to below 3 mm, bringing them closer to those used in polymeric hollow fiber membranes. While this advancement has successfully mitigated energy demands, it has simultaneously introduced a new constraint: since the external diameter of the monolith increases, so does the hydraulic resistance that the permeate faces on its way to the outlet. This phenomenon imposes a practical upper limit on monolith diameters, typically around 50 mm, beyond which filtration flux declines to suboptimal levels. A viable strategy for further increasing mineral membrane filtration surface has been the integration of multiple monolithic elements within a single filtration module, wherein the permeate is collected through the interstitial space between the monoliths. This design innovation has enabled filtration packing densities of up to 184 m2/m3 [1]. Despite the inherent limitations of this improvement, tube-shaped monolithic ceramic membranes remain among the most widely commercialized configurations, particularly by manufacturers such as Altech Innovations GmbH (Gladbeck, Germany), Rauschert Distribution GmbH (BU Inopor®) (Scheßlitz, Germany) or Alsys (KleansepTM) (Salindres, France).

An important advancement in enhancing the filtration packing density of mineral membranes has been the modification of the monolith’s outer geometry from cylindrical to hexagonal. This design innovation permits a more compact arrangement of membrane monoliths within the filtration module, akin to the natural structure of a honeycomb. Leveraging this configuration, Pall Corporation developed the Membralox® filtration modules, thus achieving packing densities of up to 285 m2/m3 [13,14]. Nonetheless, the most impactful breakthrough in the development of high packing density membranes has been the incorporation of multiple internal conduits within the membrane monolith. These conduits are constructed from highly porous materials and feature low-pressure-drop flow paths that facilitate efficient permeate transport to the module outlet [15]. This technolo-gical advancement, pioneered by CeraMem Corporation (Waltham, MA, USA) (now part of Alsys, Salindres, France), enabled the fabrication of monolithic membranes with larger diameters (up to 142 mm) while maintaining excellent hydraulic performance. As a result, packing densities as high as 782 m2/m3 have been achieved [14,16] V03/03/21, 2021). This progress has enabled the design of more compact and energy-efficient membrane systems, thereby narrowing the performance and cost gap between polymeric and mineral membranes in terms of installation footprint and operational efficiency [11,12].

The clarification of fruit juices through pressure-driven MF and ultrafiltration is among the most widely implemented processes in the food industry. Membranes with nominal pore sizes of up to 200 nm are generally preferred [17], since they fulfill a dual role: achieving both effective clarification and cold microbial stabilization of the treated juices. However, the use of such fine-pored membranes can adversely affect filtration flux and may compromise certain quality attributes of the final product [18], a message suggesting that exploring more open membranes may be an interesting alternative for improving productivity in juice clarification activities.

Our recent research has focused on identifying efficient techniques for the complete removal of insoluble solids from olive juice, a critical clarification stage for its subsequent valorization into industrial intermediate or end-products. To this end, we evaluated the performance of some technologically advanced and energy-efficient tangential-flow pressure-driven MF membranes available on the market. This included multichannel membranes with enhanced packing density and improved chemical, mechanical and fouling resistance with nominal pore sizes ranging from 200 nm to 1400 nm. The extensive experimental data generated from these efforts is being presented in a series of publications. The first installment detailed the performance of two α-Al2O3 membranes with enhanced filtration packing density and pore sizes of 800 nm and 600 nm, which are very rarely used in fruit juices clarification [1]. In contrast, the present study explores a distinct set of two MF mineral membranes engineered for high filtration packing densities and low flux-resistant supporting layers. The first is an α-Al2O3 membrane with a 200 nm nominal pore size, representative of membranes commonly employed in juice clarification. The second is a mixed-oxide membrane with a nominal pore size of 500 nm, selected to evaluate the efficacy of more open MF structures, rarely utilized for this application. Both membrane layers were deposited on recrystallized silicon carbide (RSiC) supports featuring 2 × 2 mm square flow channels. This geometry is consistent with industrial monolithic membrane elements designed to achieve very high filtration packing densities, ensuring the industrial scalability of the results and enabling a direct performance comparison under identical operational conditions. The results are likely transferable to similar fruit and vegetable juices.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Olive Juices

To evaluate the filtration performance of the MF500 and MF200 membranes, 50 L of fresh crude olive juice were taken directly from a 3-phase decanter during olive oil production in January 2023 at an olive oil mill located in Navalvillar de Pela (Badajoz, Spain). Similarly, a 60 L of fresh fluid semi-skimmed olive paste were obtained from a 2-phase decanter in November 2022 at an olive oil mill in Los Navalmorales (Toledo, Spain). In both cases, the aliquots corresponded to the Cornicabra olive cultivar. Immediately after collection from the decanters, the olive juices and pastes were frozen within 3–6 h and stored at −20 °C until their use.

On the other hand, to evaluate the impact of suspended solids on MF500 membrane fouling, two 20 L aliquots of clarified olive juice were previously processed using a membrane with a nominal pore size of 800 nm as described in [1]. These juices were frozen immediately following filtration and stored at −20 °C until their use in the present experiments. To assess the impact of dissolved substances on MF500 membrane fouling, other 60 L (3 aliquots of 20 L) of fresh olive juice with different total dissolved substance and similar suspended solid contents were collected directly from a 3-phase decanter from Villafranca de los Caballeros (Toledo, Spain). The juice was frozen within 3 h after collection and stored at −20 °C until use.

2.2. Reagents

Sodium hydroxide, sodium lauryl sulphate, N2, 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) diammonium salt (ABTS), potassium persulfate, Trolox, HPLC-grade methanol and acetonitrile, glacial acetic acid, HPLC-grade pure reference substances, demineralised water and Milli-Q grade water were acquired as described in [1].

2.3. Pilot Scale Pressure-Driven Tangential-Flow Membrane Filtration Unit and Membranes

Olive juices were clarified in a pilot pressure-driven tangential-flow membrane unit as described in detail by [1]. Two mineral membranes, termed M500 and M200 with filtration surface of 0.13 m2 from CeraMem® Corporation (Waltham, MA, USA) were coupled in this unit using a model LM-0500-M stainless steel housing. The technical characteristics of both membranes are presented in Table 1. The main differences between these membranes are their composition and nominal pore sizes of 500 and 200 nm.

Table 1.

Technical characteristics of the studied microfiltration 500 and 200 nm pore size CeraMem membranes [14,15].

As shown in Table 1, the calculated filtration packing density of both studied membranes was just 28.7 m2/m3, apparently similar to the classic ceramic membrane. However, the key advantage of these membranes lies in the highly compact design of their full-scale industrial counterparts, which achieve packing densities as high as 782 m2/m3 per monolithic element. This places them within the category of high packing density membranes, approaching the values typical of polymeric hollow-fiber membranes [19]. This design advantage allows for the maintenance of high tangential-flow velocities while requiring substantially less pumping power [20]. In fact, for pilot-scale applications, CeraMem Corporation recommends tangential flow velocities in the interval of 2–3 m/s, which is one of the lowest velocities found in the literature. Another distinctive feature of these membranes is their RSiC support, characterized by high porosity and a narrow pore size range (5–11 µm). This material imparts exceptional mechanical, chemical, and thermal robustness, as well as enhanced fouling resistance [21]. Moreover, RSiC is among the most hydrophilic materials used in the production of mineral membranes [12,22], which facilitates higher water and polar solute permeability, more efficient filtrate evacuation through the permeate channels, and improved rejection of residual oils and lipids, components typically present in trace amounts in olive juice.

2.4. Membrane Experimental Methodologies

2.4.1. Olive Juice Pre-Treatment

Before each fine membrane clarification, 25–30 L of raw olive juices and semi-skimmed olive pastes were cleaned from coarse insoluble solids and residual oil by centrifugation and screening as previously described [1]. Two aliquots of 20 L of centrifuged olive juice from the Navalvillar de Pela olive mill were taken for filtration with the MF500 membrane and two aliquots of 20 L of centrifuged olive juice from the Los Navalmorales olive mill were taken for filtration with the MF200 membrane.

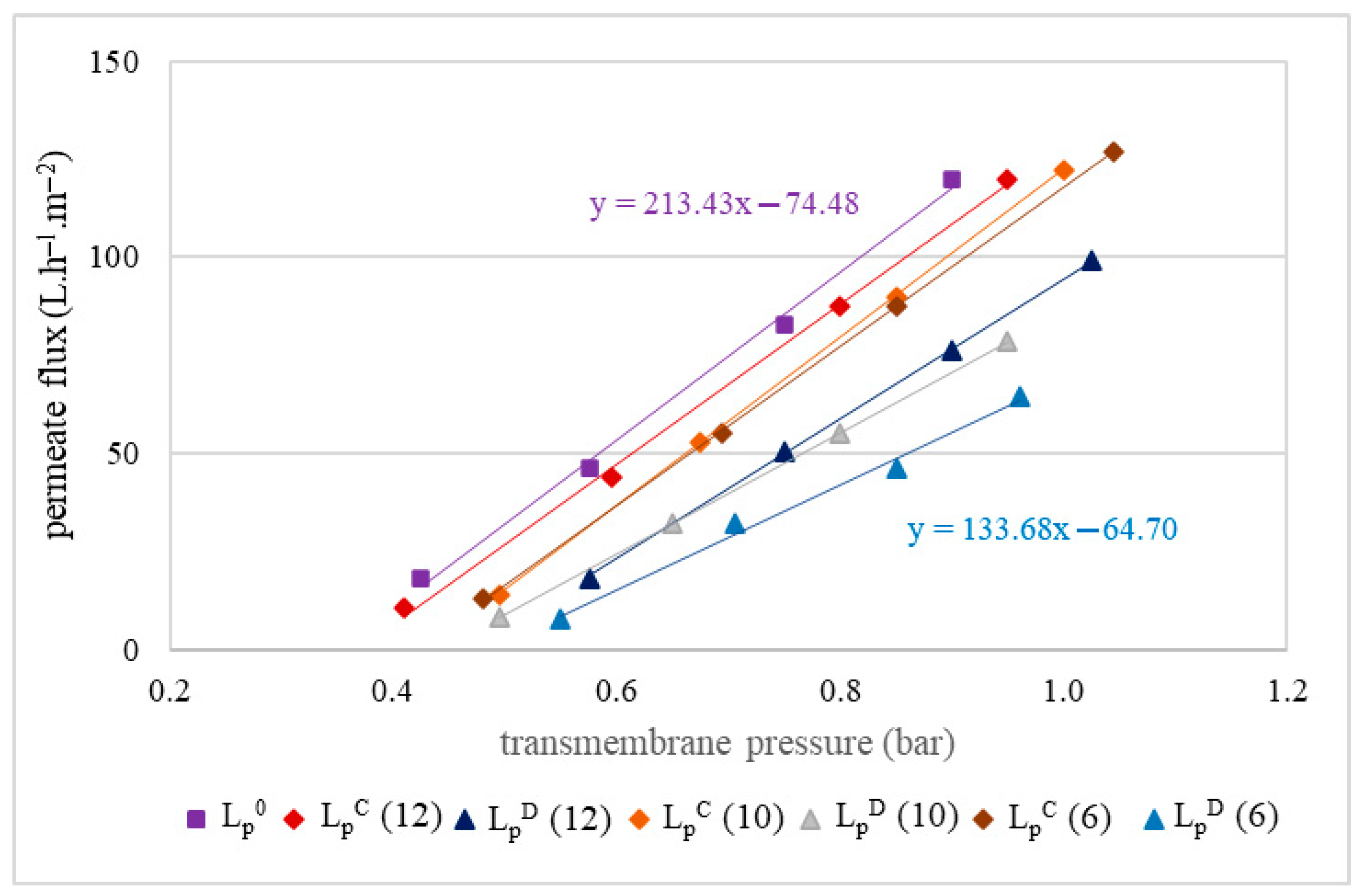

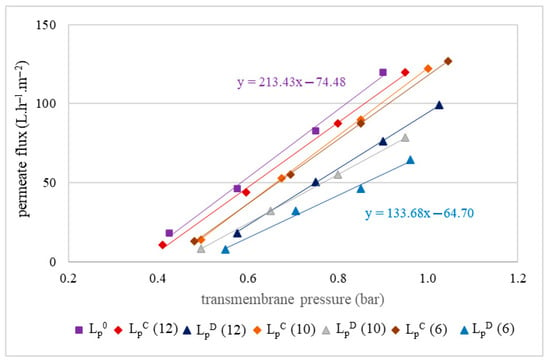

2.4.2. Membrane Hydraulic Permeability Test

The membrane hydraulic permeability was evaluated following the methodology described by Cassano et al. [23], based on the slopes of the straight lines obtained by plotting permeate flux against the applied transmembrane pressures (PTM). Permeability measurements were conducted as described in [1] and recorded under PTM ranging from 0.2 to 1.3 bar, at a tangential flow velocity of 2.5 m/s and a controlled temperature of 25 °C. The loss of hydraulic permeability was calculated as the decrease from the initial value (LP0) relative to the final value (LpC or LpD), considering the initial value as 100%.

2.4.3. Olive Juice Permeability Test

Olive juice permeability test was conducted as previously described [1] at five PTM from the interval of 0.4 to 1.3 bar.

2.4.4. Filtration

Clarification was performed in duplicate in batch concentration mode as described in [1] at temperature of 25 ± 2 °C and a tangential-flow velocity of 2.5 m/s. For each replicate, 20 L of centrifuged olive juice were processed at a PTM of 1.2 bar and 15 L of clarified juice and 5 L of concentrate were obtained. Filtration flux was monitored by collecting the permeate over a 1 min using a class A graduated glass cylinder, at 30 min intervals. Reported flux values represent the mean of three measurements taken at each time point. The volumetric concentration factor (FVC) was calculated using Equation (1).

where Vfeed is the initial feed volume and Vperm is the cumulative volume of collected permeate.

FVC = Vfeed/(Vfeed − Vperm) (−)

2.4.5. Membrane Cleaning and Conservation

Membrane cleaning and conservation was conducted as described in [1] and their hydraulic permeability was evaluated following both chemical cleaning and drying.

2.4.6. Assessment of the Impact of Suspended Solids on MF500 Membrane Fouling

To explore the influence of suspended solids on membrane fouling, two 20 L aliquots of semi-clarified olive juice (permeates generated from the 800 nm nominal pore size membrane studied previously by Gutiérrez-Docio et al. [1]) were re-filtered using the MF500 membrane. These juices had a total dissolved substance content of 6.2 g/100 mL and a turbidity from 50 to 30 Nephelometric Turbidity Unit (NTU), notably higher than those of 19–14 NTU measured immediately after the treatments with the 800 nm pore. This increase was likely due to particle aggregation or re-dispersion after thawing. Filtration conditions, as well as monitoring of the operation parameters, were conducted as described in Section 2.4.4. To evaluate the extent of irreversible membrane fouling, hydraulic permeability tests were performed on the 500 nm membrane prior to filtration, following chemical cleaning, and after drying.

2.4.7. Assessment of the Impact of Dissolved Substances on MF500 Membrane Fouling

The influence of total dissolved substances (TDS) on membrane fouling was also examined using three aliquots of 20 L thawed and centrifuged (17,568· g, 5 min at 20 °C) olive juice. Following centrifugation, the TDS content of the aliquot was 12.4, 10.0 and 6.4 g/100 mL, with turbidity values consistently ranging from 3900 to 4200 NTU. Filtration conditions and process parameter monitoring were implemented as described in Section 2.4.4. Hydraulic permeability measurements were carried out on the 500 nm membrane prior to filtration, following chemical cleaning, and after drying.

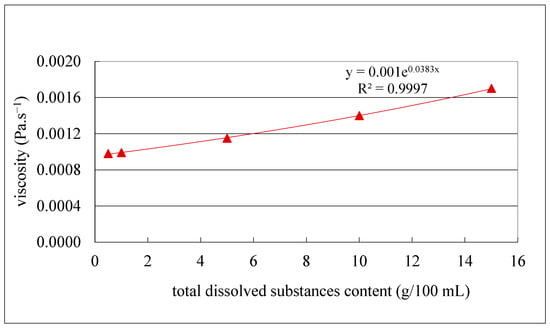

Viscosity measurements were conducted on clarified olive juice with turbidity <0.5 NTU (permeate from the MF500 membrane treatment). For this analysis, 1 L of clarified olive juice was concentrated using a rotary evaporator at 30 °C until a TDS content of 15 g/100 mL was reached. Aliquots were prepared from this concentrate by subsequent dilutions with deionized water to obtain final concentrations of 15, 10, 5, 1, and 0.5 g/100 mL. Viscosity was assessed using a TA Instruments AR-G2 controlled-stress rheometer (TA Instruments, New Castle, DE, USA) with concentric cylinder geometry and a measurement gap of 4000 μm. All measurements were conducted in triplicate at 25 °C using a steady-state flow test over a shear rate range of 1 to 100 1/s. Prior to analysis, samples were thawed at room temperature and homogenized using a vortex mixer for 1 min.

2.5. Physicochemical Analysis

Analyses of total suspended solids (via turbidity), particle size distribution, total dissolved substances, electrical conductivity, pH as well as transfer of matter and retention of certain juice components after clarification were conducted as previously described in detail by Gutiérrez-Docio et al. [1].

2.6. HPLC-PAD-MS Analysis of Individual Phenolic and Secoiridoid Compounds

Identification and quantitative assessment of individual phenolic and secoiridoid compounds and their conjugates in freeze-dried olive juice samples, before and after clarification, were performed using reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) coupled with photodiode array detector (PAD) and mass spectrometer (MS) as described in [1,24,25]. Six new compounds were identified also in this study with very high probability (>95%), according to their retention time, order of elution, UV spectra, and molecular and diagnostic fragment ion masses in comparison with bibliographic data (demethylelenolic acid glucoside (DeMEA-glu) [24], β-Hydroxyverbascoside (caffeoyl-(glucoside-rhamnoside)-3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol or 3,4-DHCA-(glu-rha)-3,4-DHPG) [26], (E)-cafselogoside or (E)-caffeoyl-6′-O-secologanoside [27], oleuropein glucosides isomers 1 and 2 [28], as shown in Table 2. They were quantified as equivalents of EA, (E)-3-Me-4-HCA, (E)-3,4-DHCA and 3,4-DHPE-EA-glu, respectively, for their spectral similarities. One flavon derivative was tentatively identified with low probability according to its retention time, elution order and UV spectra and was quantified as equivalents of luteolin 7-O-glucoside for their spectral similarities. This compound was included in the study just to evidence the effect of clarification on this group of compounds.

Table 2.

Spectroscopic and spectrometric data of the additionally identified phenolic and secoiridoid compounds present in olive juices.

The increase (inc) of the content of some phenolic, secoiridoid and their conjugated derivative compounds in the clarified juices was calculated as the ratio of the compound’s concentration in the clarified juice to its concentration in the reference juice. This ratio was multiplied by 100 and then adjusted by subtracting 100, as shown in Equation (2). All values were expressed on a dry juice matter basis as mg of compound/g of dry juice.

Xinc = (Xclar·Xref − 1) · 100 (%)

2.7. Antioxidant Activity Assessment

Antioxidant activity was assessed using the ABTS assay, as described in [1].

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the IBM SPSS 26.0 statistical software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Differences among membrane treatments were assessed using a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Post hoc Tukey’s tests to analyze variations between replicates and membranes. Pearson’s correlation tests were conducted for additional analyses. An independent samples t-test was employed to compare the mean values of phenolic and secoiridoid compound amounts, and antioxidant activity between the reference and clarified juice for each membrane. Results were considered statistically significant at p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Olive Juice Pre-Treatment

Following thawing of two 25 L aliquots (totaling 50 L) of a 3-phase crude olive juice, a part of the coarse insoluble solids was removed via centrifugation. This treatment yielded 44 L of centrifuged olive juice and 6 kg of wet, coarse insoluble solids, representing 12% of the crude olive juice. Similarly, centrifugation of two 30 L aliquots (60 L total) of fluid semi-skimmed olive paste obtained from a 2-phase decanter produced 30 L of centrifuged olive juice and 27 kg of coarse wet solids, representing a removal of 45% insoluble matter. The resulting centrifuged juice had a TDS content of 12 g/100 mL. Due to the important influence of TDS on viscosity, and consequently on filtration performance [29], an attempt was made to adjust the TDS content to 8 g/100 mL using demineralized and deoxygenated water. However, the juices were slightly over-diluted, resulting in a final TDS concentration of 7.6 g/100 mL and a total volume of 42 L.

3.2. Olive Juice Physicochemical Characteristics

Prior to fine membrane clarification, each batch of 20 L pre-treated (centrifuged) olive juice was characterized in terms of its physicochemical properties. The corresponding analytical results are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Physicochemical characteristics of the centrifuged olive juices before their fine clarification by the MF500 and MF200 membranes.

The centrifuged olive juices were characterized by high turbidity, ranging from 8069 to 8470 NTU for the MF500, and from 4175 to 4428 NTU for the MF200 membrane feeds, indicating a substantial suspended solids load despite prior centrifugation. The lower turbidity observed in the MF200 membrane feed was due to water dilution, as described in Section 3.1. Particle size distribution analysis revealed a mean size range of 0.26 to 777 μm for all treated olive juice replicates. This indicates that centrifugation at 17,568· g removed only particles larger than 777 μm, leaving particles comparable in size to the membrane pores unaffected. Additionally, TDS concentrations differed slightly between the samples: the MF500 membrane feed had a TDS content of 8.0 g/100 mL, while the MF200 filtration feed contained 7.6 g/100 mL. Both juices were moderately acidic (pH 4.94–4.98), and demonstrated high electrolyte concentrations, indicated by electrical conductivity values from 7.73 to 11.53 mS/cm. Although the olive juice from the 2-phase decanter (MF200 membrane) was diluted to achieve a TDS content similar to that from the 3-phase decanter (MF500 membrane), its EC remained notably higher. This indicates that olive pomace possesses much higher TDS and electrolyte contents than the juice, a difference explained by the water addition required in 3-phase decanters for improving oil recovery, a procedure unnecessary in 2-phase systems.

3.3. Olive Juice Permeability Test

The results of the olive juice permeability test for the studied MF500 and MF200 membranes presented linear responses across the whole range (0.4–1.2 bar) of studied PTM. Thus, the highest PTM of 1.2 bar was chosen for filtration of the juices with both membranes. The MF500 membrane demonstrated a flux rate 1.4 times higher than that of the MF200 membrane.

3.4. Effect of the Operating Conditions on Filtration Flux

Filtrations were conducted with 20 L of olive juice per batch at PTM of 1.2 bar and a temperature of 25 ± 2 °C. The treatments concluded when 15 L of filtered juices were recovered and 5 L of concentrated suspensions left in the concentrate circuit, corresponding to a 75% of olive juice recovery. This final ratio represented a volumetric concentration factor (FVC) of 4.

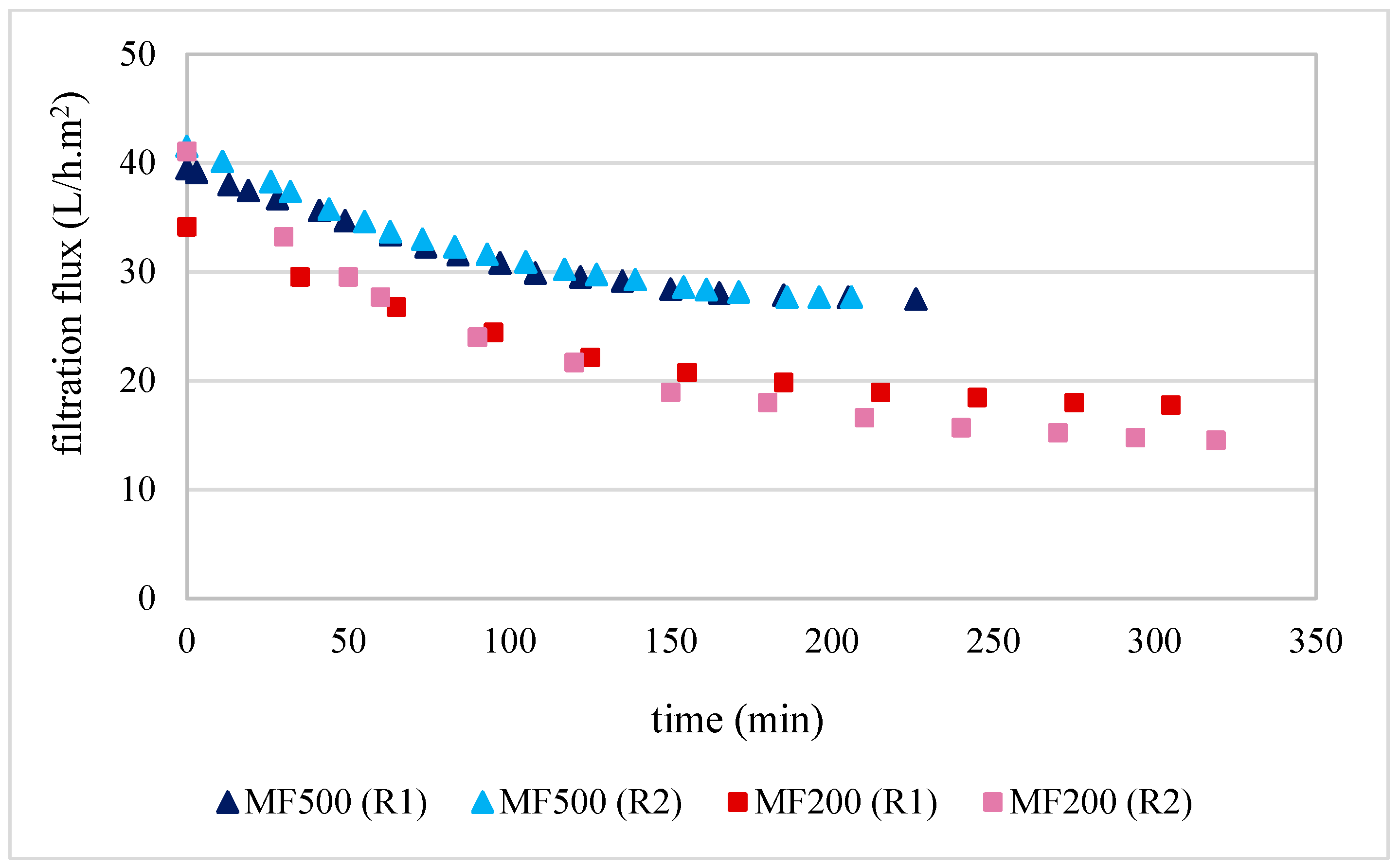

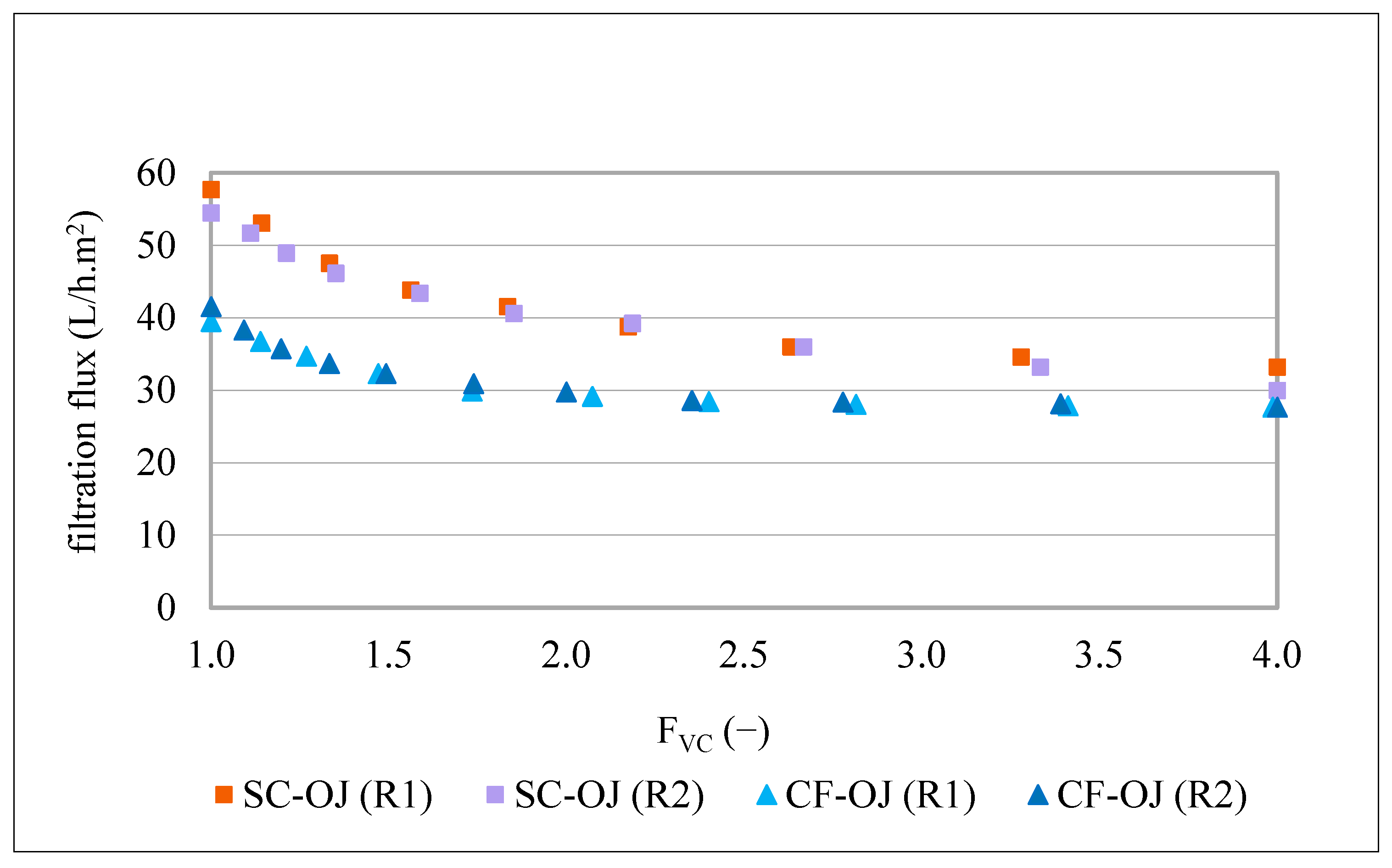

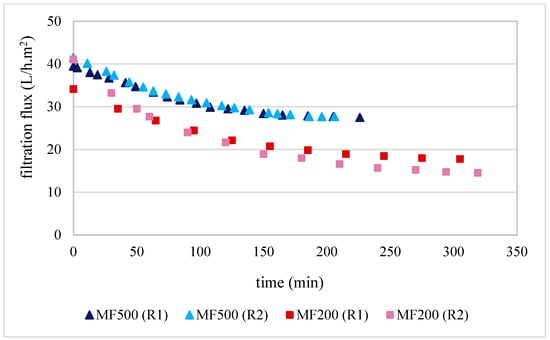

Filtration trials using the MF500 membrane commenced with initial fluxes of 40 and 42 L/h.m2 and concluded after 3 h 56 min and 3 h 26 min for replicates 1 and 2, respectively (Figure 1). A steady-state flux of 28 L/h.m2 was observed during the final 1.5 h of operation in both replicates, corresponding to a flux decline of approximately 30–33%. The high reproducibility between replicates indicates that membrane fouling was primarily reversible and that the chemical cleaning protocol employed was effective in restoring performance.

Figure 1.

Flux kinetics produced during olive juice filtration by MF500 and MF200 membranes for both replicates (R1 and R2) at PTM of 1.2 bar.

One of the studies most comparable to the present investigation on olive juice clarification using the MF500 membrane is that conducted by Gutiérrez-Docio et al. [1]. In this study, an α-Al2O3 membrane with a mean pore size of 600 nm (Inopor) was employed to clarify 40 L of olive juice. The initial average filtration flux declined from 38 to 19 L/h·m2 after filtering an equivalent volume of 20 L, representing a 50% decrease in flux. This decline was approximately 1.7 times greater than that observed with the MF500 membrane in the present study. Notably, the MF500 membrane, despite its smaller nominal pore size, demonstrated superior filtration flux and reduced fouling when compared with the 600 nm α-Al2O3 membrane. These findings can likely be explained by the enhanced hydrophilicity of both the mixed-oxide membrane material and the RSiC support [12] of the MF500 membrane, which are known to enhance antifouling properties. Additionally, it is important to note that the olive juices used in both studies underwent only a single centrifugation step prior to filtration. This pre-treatment likely had limited efficacy in removing fine particles near the membrane pore size, as well as the colloidal fraction of the juice, primarily composed of proteins and polysaccharides (notably pectins), which are well-known membrane foulants [30].

A related study involving a membrane comparable to the MF500 was conducted by Russo [31] who employed two ZrO2 membranes with nominal pore sizes of 450 nm for the filtration of vegetation water, presumably olive juice, that had undergone acidification, enzymatic pectolytic hydrolysis, and centrifugation as pre-treatment steps. The experiments were performed at a PTM of 1.7 bar, a FVC of 3, and a tangential flow velocity of 4.7 m/s. Of the two tested membranes, one was of the Isoflux type and achieved a stable filtration flux of approximately 70 L/h.m2, while the other membrane exhibited a flux of around 50 L/h.m2. These values are notably higher than those obtained with the MF500 membrane in the present study. The superior performance observed by Russo [31] can be primarily attributed to the higher applied PTM and tangential flow velocity, as well as to the more intense pre-treatment, including stronger coarse clarification and enzymatic degradation of pectins, which likely reduced the fouling potential of the feed material.

Regarding the MF200 membrane, the results presented in Figure 1 indicate that filtrations started with fluxes of 34 and 41 L/h·m2 for replicate 1 and 2, respectively. After 5 h and 10 min and 5 h and 30 min of filtration, the filtration fluxes decreased to 18 and 14 L/h·m2 for replicate 1 and 2, under the same operating conditions. Surprisingly, the first replicate of this treatment started with lower filtration flux; however, it reached a higher steady-state flux of 22 L/h·m2 after 2 h of filtration. This behaviour led to an overall flux decline of 47%. These results could be explained by the fact that the membrane was conditioned just by hydration for overnight prior filtration. Consequently, it may have retained some manufacturing impurities, which were progressively removed during the initial filtration and the following chemical cleaning. On the other hand, despite, the second replicate started with a higher filtration flux, it reached a steady-state flux at lower values of 14 L/h·m2, resulting in a higher overall flux decline of 65%. Similar behaviour was already described by Garcia-Castello et al. [32], who employed a 200 nm alumina membrane (Inopor) for the clarification of OMWW over six consecutive filtrations and cleaning cycles. They observed an accumulative build-up of irreversible fouling, despite intermediate chemical cleanings, which led to a progressive decline in filtration performance across cycles. In their study, initial fluxes ranged from 57 to 43 L/h·m2, likely due to the lower TDS content (5.4 g/100 mL) in the OMWW compared to the higher TDS concentrations (7.6–8.0 g/100 mL) in the olive juices used in the present study (Table 3). Additionally, Bazzarelli et al. [10] employed a TiO2 membrane with a mean pore size of 140 nm (Tami Industries) for the direct clarification of OMWW. Operating at a PTM of 1.7 bar and a FVC of 12, the filtration flux declined from 120 to 20 L/h·m2. Although this performance was slightly higher than that observed for the MF200 membrane, the difference can be attributed to the higher PTM and the greater hydrophilicity of the TiO2 membranes [12], which may have compensated for their smaller pore size. This progressive decay of MF200 filtration flux was not evident in the experiments conducted using the MF500 membrane. Overall, the MF200 membrane demonstrated considerably lower filtration flux kinetics compared to the MF500 membrane. Specifically, an average filtration time of 5 h was required to clarify 20 L of olive juice with the MF200 membrane, while the MF500 membrane completed the same volume in just 3 h and 30 min. This corresponds to a 1.3-fold decrease in time efficiency for the MF200 membrane relative to the MF500 membrane. These results suggest that membranes with pore sizes smaller than 200 nm are more susceptible to fouling when exposed to the colloids and suspended solids present in olive juice than those with pore sizes in the 500–600 nm range. In a study on beer clarification by three microfiltration membranes with 200, 500 and 1300 nm nominal pore sizes from CeraMem, Gan et al. [33] found also that the 500 nm pore size membrane gave the best operational and quality parameters of clarification. Furthermore, all these findings raise concerns regarding the practical utility of membranes with pore sizes below 200 nm or above 600 nm for the efficient clarification of olive juice.

3.5. Mass Transfer Through the Membranes During Filtration

3.5.1. Suspended Solids Transfer

Samples from both permeate and concentrate streams were routinely collected and analysed for their turbidity across the membranes, as an indirect measure of their insoluble solids content. The results for permeates and concentrates are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Turbidity variation intervals in the initial and final concentrate and permeate streams during clarification of centrifuged olive juice replicates and their transfer through the MF500 and MF200 membranes.

The results presented in Table 4 demonstrate that the MF500 membrane consistently maintained low and stable permeate turbidity throughout the filtration process, within a narrow interval of 0.06–0.18 NTU. In contrast, the MF200 membrane exhibited higher and more variable turbidities, varying from 0.42 to 1.27 NTU. While both membranes delivered excellent clarification performance, achieving permeate turbidities well below the 2 NTU threshold, the MF500 membrane clearly outperformed the MF200 membrane in terms of both clarity and consistency. Notably, the MF200 membrane, which was expected to provide superior clarification due to its smaller mean pore size, yielded unexpectedly lower performance. However, the data for turbidity transfer indicate that practically all suspended solids remained in the concentrates.

As previously mentioned, Zhao et al. [18] encouraged for the adoption of membranes with larger pore sizes, which can effectively clarify juices and remove microorganisms without adversely affecting their chemical composition, while also enabling higher filtration fluxes. They used a 450 nm α-Al2O3 membrane (Isoflux™ from TAMI) [34] to clarify raw apple juice and reported an average turbidity of 1.55 FNU. This result is comparable to the turbidity levels obtained with the MF200 membrane in the current study and slightly higher than those achieved with the MF500 membrane. Taken together, these findings, particularly when considering both filtration flux and clarification efficiency, provide compelling evidence in support of Zhao et al.’s [18] recommendation. From both a productivity and economic standpoint, the use of MF membranes with larger pore sizes represents a competitive and effective alternative for juice clarification.

3.5.2. Total Dissolved Substances (TDS) Transfer

Table 5 presents the initial and final TDS contents in the concentrate, permeate and their transfer registered during the filtration of replicates 1 and 2 through the MF500 and MF200 membranes.

Table 5.

Total dissolved substances (TDS) content in the initial and final concentrate and permeate streams during clarification of centrifuged olive juice replicates and their transfer through the MF500 and MF200 membranes.

The results obtained for the MF500 membrane indicate an increase in the TDS content of the concentrate streams, from 8.0 to 9.1 g/100 mL and from 7.8 to 8.6 g/100 mL for replicates 1 and 2, respectively. A slight rise in TDS content was also observed in the corresponding permeate streams, attributable to the concentration effect occurring in the retentates [1]. Initially, the TDS transfer through the membrane was high for both replicates (95 and 92%, respectively) but progressively declined to 87 and 86% since the FVC increased to 4. A similar trend was observed during the treatment with the MF200 membrane. In this case, the TDS content in the concentrate streams increased from 7.6 to 8.4 g/100 mL and from 7.6 to 8.5 g/100 mL for replicates 1 and 2, respectively. The initial TDS transfer through the MF200 membrane was comparable to that of the MF500 membrane (94%), yet it declined to 83 and 82% by the end of the filtration.

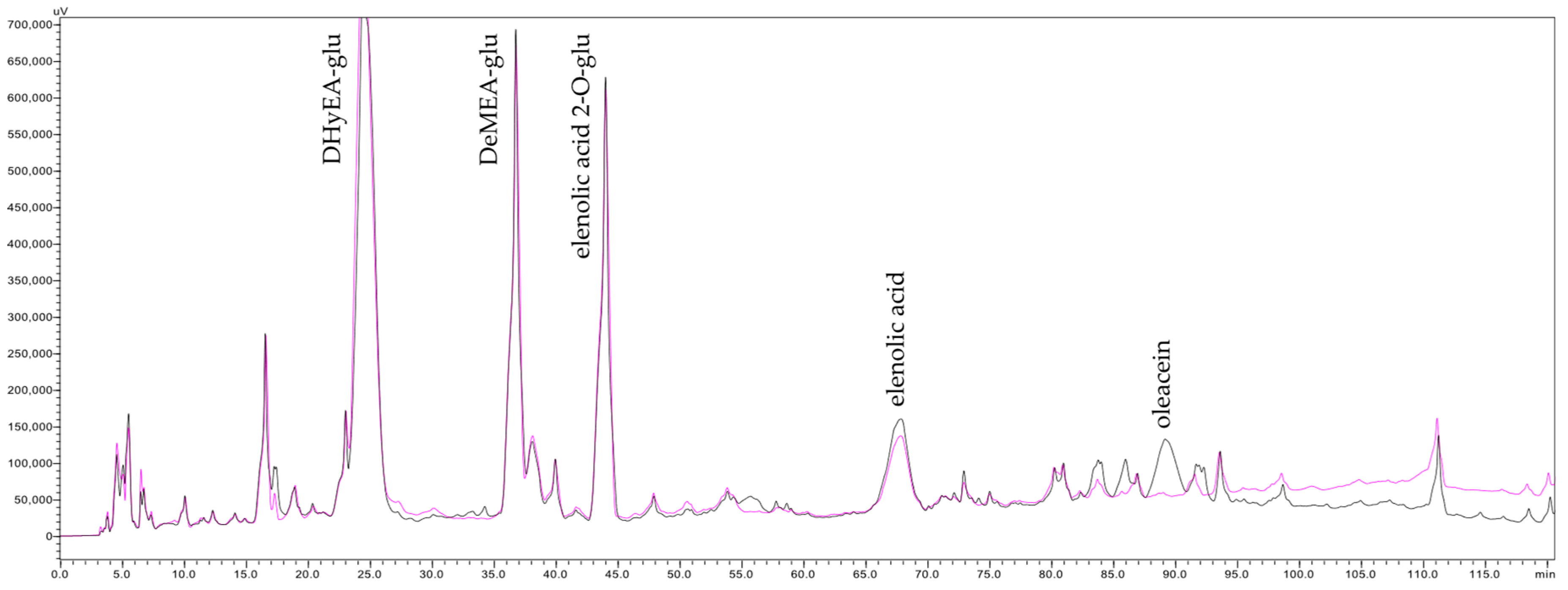

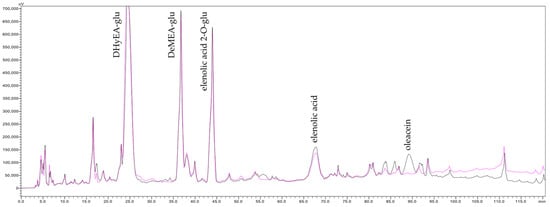

When compared with the performance of 600 nm and 800 nm α-alumina membranes reported by [1], which exhibited final TDS transfer of 92 and 90%, respectively, at a FVC of 4, it becomes evident that MF membranes with pore sizes ranging from 200 to 800 nm do not allow complete TDS transfer. In other words, a consistent partial retention of TDS occurs. Since individual small solutes are generally not retained under microfiltration conditions, the observed TDS retention is likely attributable to macromolecular colloids, such as polysaccharides and proteins. This hypothesis is supported by the results of overlaying HPLC chromatograms of the concentrate and permeate streams collected at the end of MF500 membrane filtration (Figure 2). These chromatograms reveal an elevation of the baseline in the latter segment (min 90–120) of the concentrate chromatogram, indicating an enrichment of macromolecules in the concentrate. These findings challenge the widely held assumption that MF has no impact on juice TDS content during clarification [18,35]. Notably, while previous studies [34] did not report changes in TDS contents, they did observe significant retention of pectin using MF membranes with a wide range of pore sizes (200–1700 nm). However, those studies did not associate pectin retention with TDS variation, likely due to the low pectin concentrations (<0.1 g/100 mL) typically found in apple juices. The present results underscore the necessity of experimental designs that capture the full kinetic evolution of analytical parameters, or at minimum, include measurements at both the beginning and the end of filtration.

Figure 2.

Chromatograms of the last concentrate (pink line) and permeate (black line) of olive juice obtained after filtration by the MF500 membrane, acquired at 240 nm, DHyEA-glu—dihydroelenolic acid glucoside, DeMEA-glu—demethylelenolic acid glucoside.

3.6. Effect of Filtration on Olive Juice Quality

3.6.1. Effect on Physical Parameters

To evaluate the overall impact of filtration on the physical parameters of the studied olive juices, samples from the reference and clarified juices were taken and analyzed for their turbidity and TDS contents and the corresponding to their retentions. The results of these analyses are presented in Table 6.

Table 6.

Turbidity and total dissolved substance content in the reference (centrifuged) and clarified olive juices and their corresponding retentions after clarification with the MF500 and MF200 membranes.

The results obtained for the clarified olive juices (Table 6) demonstrate that both the MF500 and MF200 membranes achieved complete removal of TSS, producing permeates with turbidities consistently below 1 NTU. Given the presence of residual oils in the olive juices, it is particularly noteworthy that all filtrates were visually free of oil (a critical quality requirement), verified by observation under reflected light. These findings confirm the effectiveness of both membranes in producing fully clarified olive juices [17]. However, the MF500 membrane exhibited an important operational advantage, delivering a steady-state filtration flux approximately twice that of the MF200 membrane. This enhanced performance represents a clear benefit in terms of productivity and economic efficiency. Furthermore, both membranes also retained an average of 10 and 10.5% of TDS, respectively, which are primarily attributed to the soluble macromolecular pectic polysaccharides [36,37]. These results underscore the fact that even MF membranes with relatively large pore sizes are not entirely permeable to colloidal macromolecules.

3.6.2. Effect on Small Olive Secondary Metabolites and Their Derivatives

The impact of membrane filtration on individual secondary metabolites and their derivatives present in olive juice was evaluated by a RP-HPLC. Using this approach, a total of 13 compounds were unambiguously identified and quantified, including: 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol, hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol, (E)-caffeic acid, (E)-chlorogenic acid, elenolic acid-2-O-glucoside, (E)-4-coumaric acid, (E)-ferulic acid, elenolic acid, luteolin 7-O-glucoside, (E)-verbascoside, oleuropein, and oleacein. Additionally, 12 other compounds were tentatively identified and quantified based on their retention times and spectral characteristics. These include: hydroxytyrosol-glucoside isomer 1, hydroxytyrosol glucoside isomer 2, dihydroelenolic acid glucoside, tyrosol glucosides isomers 1 and 2, demethylelenolic acid glucoside, β-hydroxyverbascoside, one flavon derivative, (E)-cafselogoside, oleuropein glucosides isomers 1 and 2, and (E)-comselogoside. The concentrations of these compounds before and after filtration, along with their respective retention or enhancement rates, are presented in Table 7.

Table 7.

Secondary metabolites and their derivative contents (on dry matter base) of the pre-treated centrifuged (reference) and the clarified olive juices and their retention (ret) or increase (inc) after clarification with the MF500 membrane (A) and the MF200 membrane (B).

The results presented in Table 7 indicate the existence of some variability in the concentrations of individual phenolic and secoiridoid compounds between the two membrane treatments (MF500 and MF200), as well as across their respective replicates. These differences are likely attributable to variations in harvest conditions, storage time, and sample handling prior to experimentation and analysis. Therefore, results are reported separately for each replicate, and the mean values shown in Table 7 correspond to HPLC analytical replicates rather than averages across experimental filtration runs.

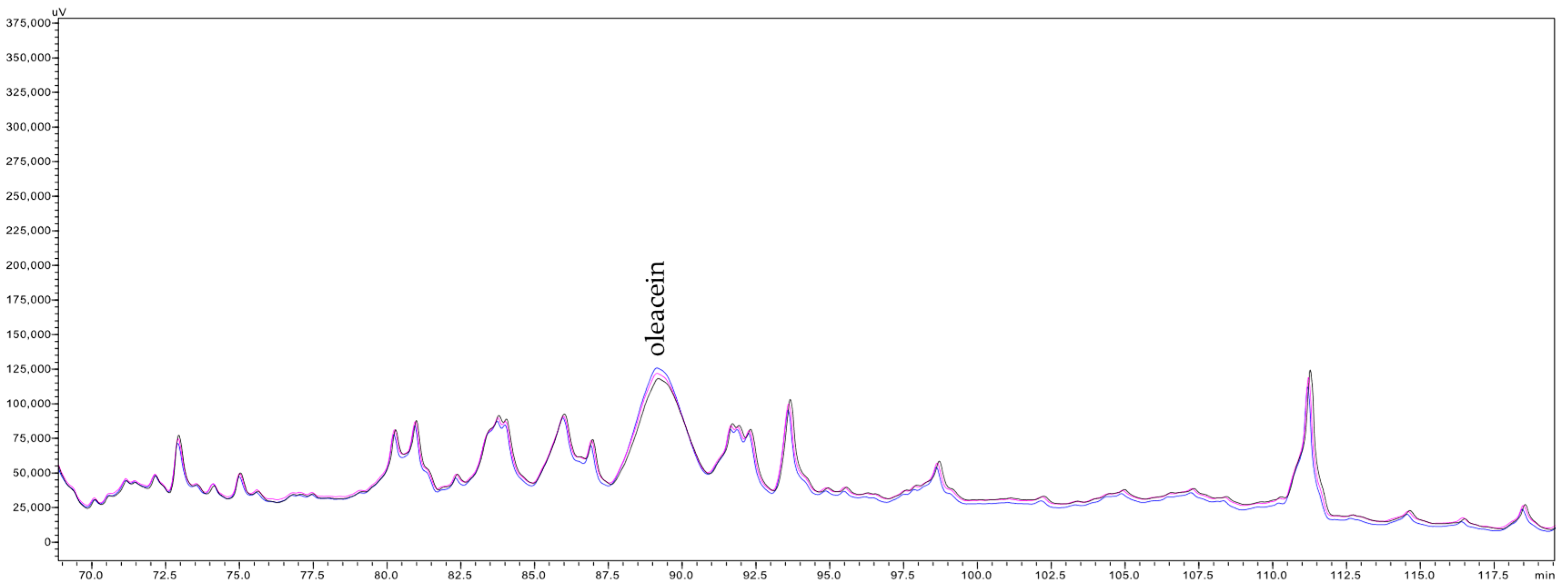

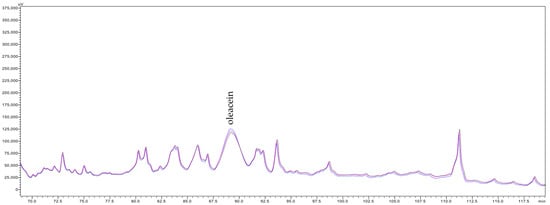

The HPLC analysis indicated that the clarification of olive juice by both studied membranes did not result in the retention of almost all quantified metabolites (Table 7). Only one exception to this trend was observed for 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol (3,4-DHPG), for which a retention of 20–23% was recorded following MF500 membrane treatment. However, this compound passed freely, and even its content increased slightly, passing through the tighter MF200 membrane. This behaviour contrasts with prior findings using 800 and 600 nm α-Al2O3 membranes, which showed no retention of 3,4-DHPG, suggesting that this result may represent an experimental anomaly. Conversely, filtration with the MF500 membrane led to notable increases from 3 to 30% of the concentrations of 3,4-DHPE-glucoside isomer 1, tyrosol (4-HPE) and its glucosides, elenolic acid and its glucoside, demethylelenolic acid glucoside (DeMEA-glu) and (E)-comselogoside in the clarified olive juices. Particularly notable were the 27–39% increase in the contents of oleuropein (3,4-DHPE-EA-glu) and oleuropein glucoside isomer 2 (3,4-DHPE-EA-2glu 2), 37–48% in the content of (E)-cafselogoside, 45% increase in the content of (E)-chlorogenic acid ((E)-3-CQA), 65–69% increase in the content of 3,4-DHPE-EA-2glu isomer 1, 52–68% increase in the content of hydroxytyrosol (3,4-DHPE), 73 and 53% increase in the content of (E)-caffeic acid ((E)-3,4-DHCA) and 271–243 and 345–259% increase in the contents of verbascoside and oleacein (3,4-DHPE-DeCMEADA), respectively. Regarding the MF200 membrane, moderate increases (ranging from 2 to 45%) were observed for several compounds, including 3,4-DHPG, 3,4-DHPE and its glucosides, dihydroelenolic acid glucoside (DHyEA-glu), tyrosol (4-HPE), DeMEA-glu, EA and its glucoside, (E)-verbascoside ((E)-3,4-DHCA-(glu-rha)-3,4-DHPE), and (E)-comselogoside (4-HCA-6’-O-glu-EA). Importantly, the increase in concentrations of these compounds in the permeate was observed consistently throughout the filtration process, suggesting the phenomena responsible for these increases was sustained from the onset to the end of filtration. Figure 3 presents chromatograms acquired at 240 nm showing the peak of oleacein in clarified olive juice samples collected at the beginning, middle, and end of the filtration.

Figure 3.

Fragment of chromatograms of the permeates collected at the beginning (black line), middle (pink line) and end (blue line) of the filtration by MF500 membranes, acquired at 240 nm.

Overall, clarification using the MF500 membrane resulted in an increase in both the number and concentration of phenolic and secoiridoid compounds and their conjugates, compared to the MF200 membrane. Furthermore, the number of compounds unveiling concentration increases following clarification (20 for MF500 and 14 for MF200 membranes) was considerably higher than those reported for the membranes studied in [1] (3 to 6 compounds). This suggests that the membrane material itself may influence the chemical transformations occurring during filtration. However, it is important to note that all olive juices used in the present and previous studies had different chemical compositions. In addition, no consistent trend was observed linking the number of affected compounds or the magnitude of their concentration increase to specific physicochemical properties of the membranes. These findings suggest the following: (1) the chemical transformation of olive juice precursors into their derivatives (products) can be induced not only by α-Al2O3 membranes, but also by mixed oxide membranes and (2) the rate of product formation appears to depend more on the initial composition of the olive juice than on membrane pore size alone. Nonetheless, further research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms and confirm the roles of membrane material and juice composition in modulating the biotransformation of secondary metabolites.

Numerous studies have also emphasized the potential risk of undesirable retention of small or less polar molecules when using MF membranes with pore sizes smaller than 200 nm or made of materials with low hydrophilicity [10,17,23,32]. In contrast, the MF500 and MF200 membranes demonstrated high efficacy in the separation of low molecular mass compounds from insoluble solids. This was evidenced by the absence of measurable retention for any of the monitored analytes, including the less polar species that eluted in the latter half of the HPLC chromatograms (Table 7, since EA).

Analysis of the structures of the compounds showing increased concentrations reveals that the majority belong to the class of phenylethanoid and phenylpropanoid glycosides [38], secondary metabolites widely distributed in the plant kingdom. Structurally, these are characterised by hydroxyphenylethanol (C6–C2) and cinnamic acid (C6–C3, e.g., caffeic, coumaric, or ferulic acid) moieties, conjugated to a β-glucopyranose sugar (such as glucose, galactose, rhamnose, or xylose) via ester and glycosidic linkages, respectively [38,39]. The resulting structures are chains of heterogeneously conjugated molecules, with relatively low masses ranging roughly from 300 to 2000 Da. In the Oleaceae family, acylation with cinnamic acids may be substituted or complemented by secoiridoid moieties such as elenolic acid or its demethylated or decarboxymethylated derivatives. Within this group of secoiridoidyl phenylethanoid glycosides [40], the most affected by membrane clarification were the constituent units 3,4-dihydroxyphenylglycol, tyrosol, hydroxytyrosol and its glucosides, elenolic acid and its derivatives, and oleacein. These changes likely result from spontaneous transformations of oleuropein or its isomers upon contact with the membrane.

One relevant finding of the present study is the observed increase in both oleuropein and oleuropein glucosides concentrations following membrane clarification. This was possible because both compounds were present in the untreated reference juice at quantifiable amounts (Table 7A). Since the chromatographic peaks of both compounds were not fully resolved from one another and their neighbors, they were integrated together. Despite this, it is clear that the content of both molecules increased in the juice clarified by the MF500 membrane. These findings suggest that the observed increases may result from the hydrolysis of structurally complex precursor molecules. This hypothesis aligns with the descripted by Cardoso et al. [41] existence of oleuropein oligomers (up to pentamers) in olive juice, which may be prone to hydrolysis with relatively low energy requirements. Cardoso et al. [42] also identified oleuropein diglucosides as potential precursors capable of yielding the observed simpler forms. Furthermore, still more complex secoiridoidyl phenylethanoid glycoside conjugates have been described in olives, olive juice, and other olive derivatives. For example, jaspolyoside is a heterogeneous pentamer composed of hydroxytyrosol, elenolic acid, glucose, elenolic acid, and glucose moieties (3,4-DHPE-EA-glu-EA-glu) [43]. Similarly, nüzhenide oleoside consists of glucose, elenolic acid, tyrosol, and multiple glucose-elenolic acid units (glu-EA-4-HPE-glu-EA) [44]. These larger conjugated structures may also serve as precursors for the generation of the simpler molecules, discussed here.

With respect to the cinnamoyl phenylethanoid glycoside subgroup, the most affected compounds during membrane clarification were caffeic acid and its derivatives, including chlorogenic acid, verbascoside, cafselogoside, and comselogoside. The observed increase in caffeic acid concentration could plausibly be attributed to the hydrolysis of unidentified caffeoyl phenylethanoid glycosides, such as calceolarioside (3,4-DHCA-glu-4-HPE), which has been previously identified in olive leaves [45] or to caffeic acid oligomers documented in other species within the Oleaceae family [46]. In contrast, explaining the increased concentrations of chlorogenic acid, verbascoside, cafselogoside, and comselogoside is more complex, since no prior studies have reported the presence of higher-order conjugated forms of these compounds in olives or their by-products. An exception is jacraninoside A, a dimer consisting of two structural units analogous to verbascoside, which was identified in the leaves of Jacaranda mimosaefolia, a species taxonomically distant from the Oleaceae family [47].

An additional explanation for the observed increases in the concentrations of certain compounds is that their formation may not solely result from interactions with the proper membrane, but also from enzymatic transformations catalysed by endogenous olive enzymes. It is important to note that the olive juices used in this study underwent minimal processing: they were collected directly from the decanter, transported for 3–6 h, frozen and stored, then thawed and centrifuged for 4–5 h prior to filtration. These conditions likely preserved high levels of enzymatic activity within the juice. Therefore, it cannot be excluded that partial enzymatic catalysis within the membranes could contribute to the observed molecular transformations during olive juice clarification.

3.6.3. Effect on Antioxidant Activity

The results of antioxidant activity of the studied juices are presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Antioxidant activity and total secondary metabolites (TSM) content in reference and clarified olive juices obtained by the MF500 and MF200 membrane.

As presented in Table 8, the antioxidant activity of the clarified olive juices was significantly higher than that of the corresponding reference juices for both membrane treatments (p < 0.005). These results are consistent with the HPLC-based quantification of total secondary metabolites content. First of all, the reference juice used for the MF200 membrane treatment had greater antioxidant capacity (0.35 mmol Trolox/g) and a higher total secondary metabolites concentration (105 mg/g) compared to the reference juice used for the MF500 membrane (0.30 mmol Trolox/g and 93 mg/g, respectively). These differences can be attributed to the degree of fruit ripeness at the time of harvest. Specifically, the olive juice processed with the MF500 membrane was derived from olives harvested in January, when the fruits were completely mature, while the MF200 juice originated from a November harvest. According to literature data [48,49], olive ripening between June and December is associated with a progressive decrease in the contents of simple phenolic compounds.

Despite the initial differences in phenolic and secoiridoid content, no significant differences in antioxidant activity were observed between the clarified juices. This can be explained by the greater relative increase in phenolic and secoiridoid content observed with the MF500 membrane treatment (15%) compared to that achieved with the MF200 membrane (9%). A strong positive correlation (r = 0.93, p < 0.001) was observed between total secondary metabolites content and antioxidant capacity, as measured by the ABTS assay, confirming the predominant contribution of phenolic and secoiridoid compounds to the antioxidant potential of the olive juices [50].

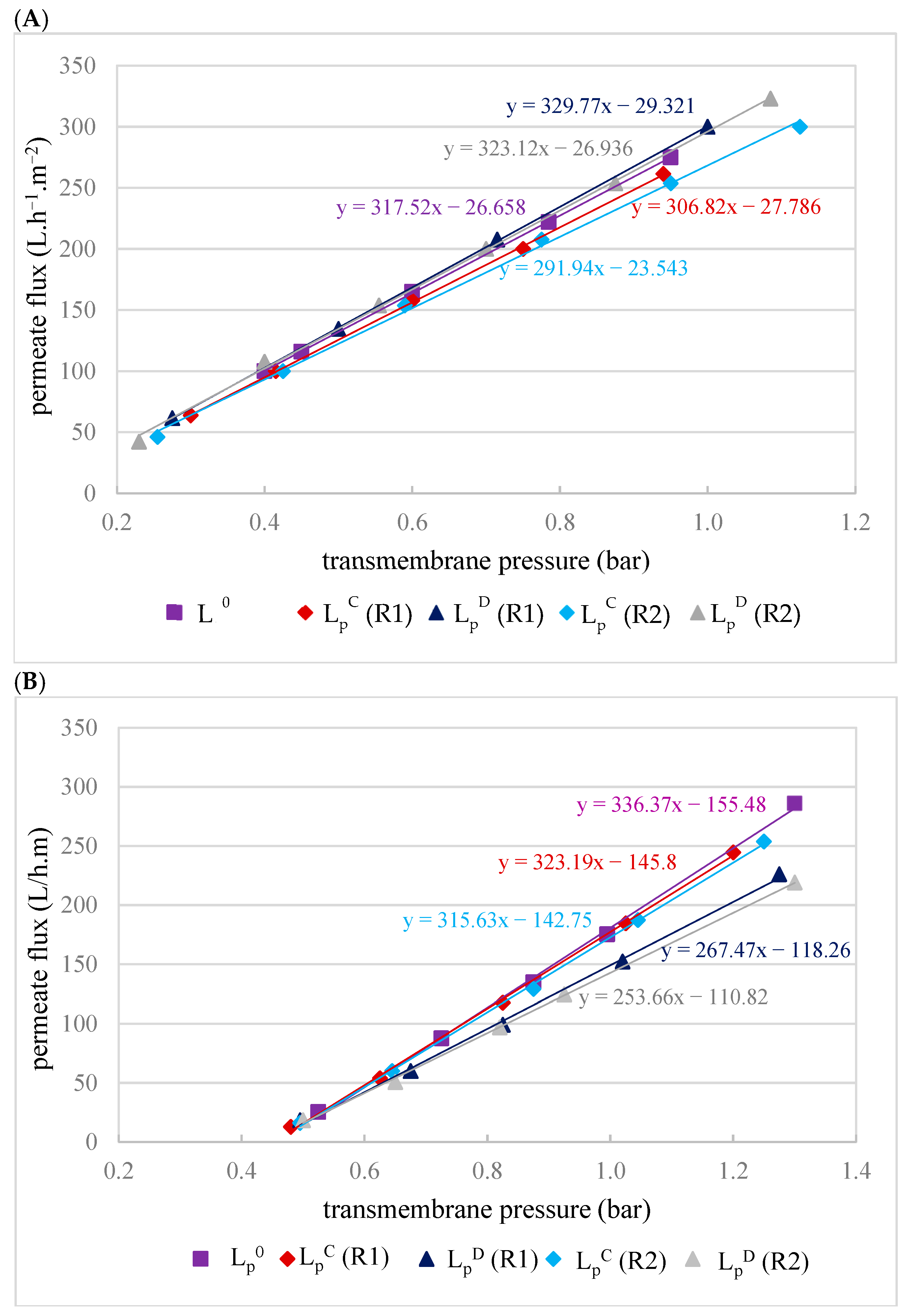

3.7. Effect of Fouling and Chemical Regeneration on Membranes Hydraulic Permeability

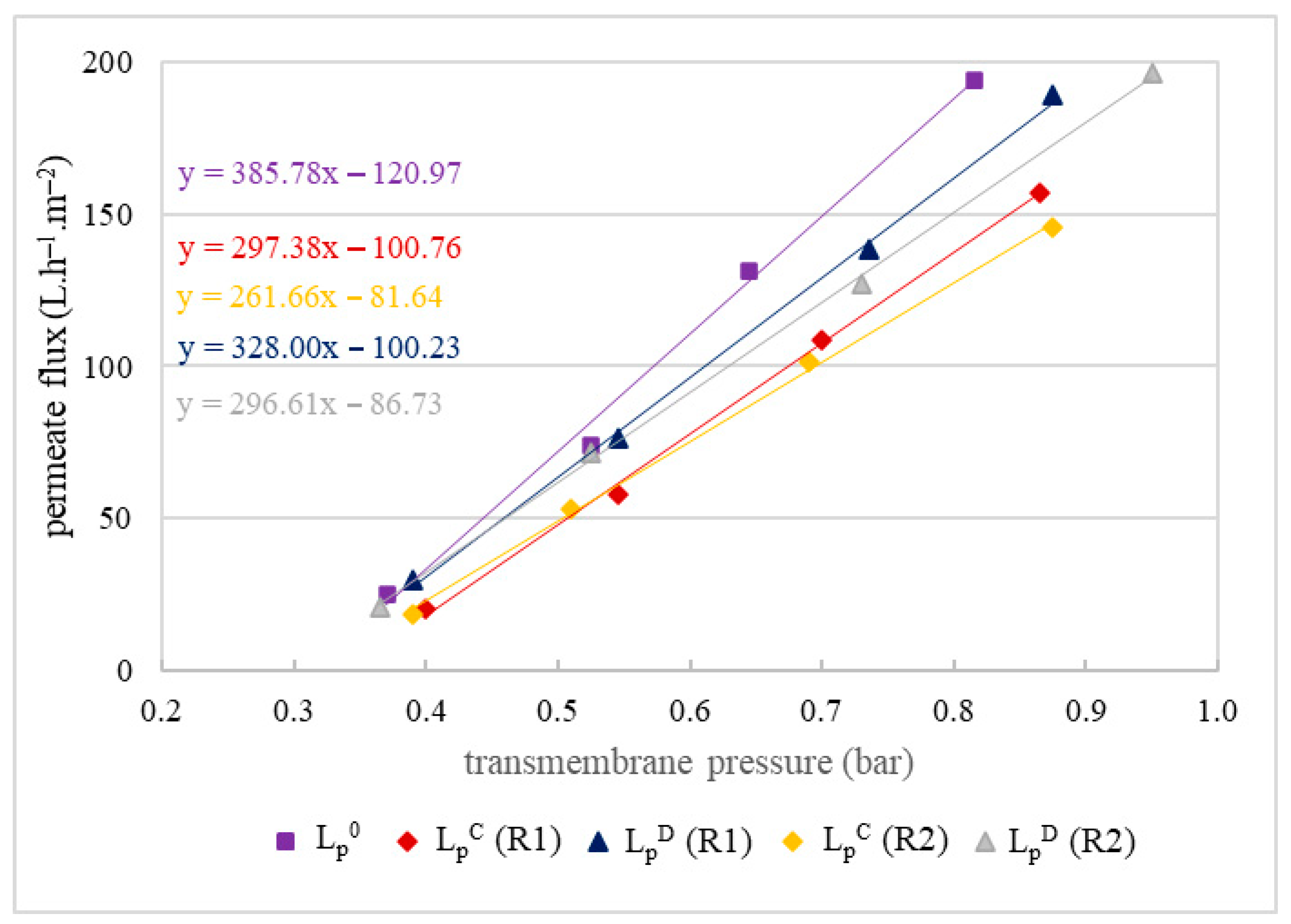

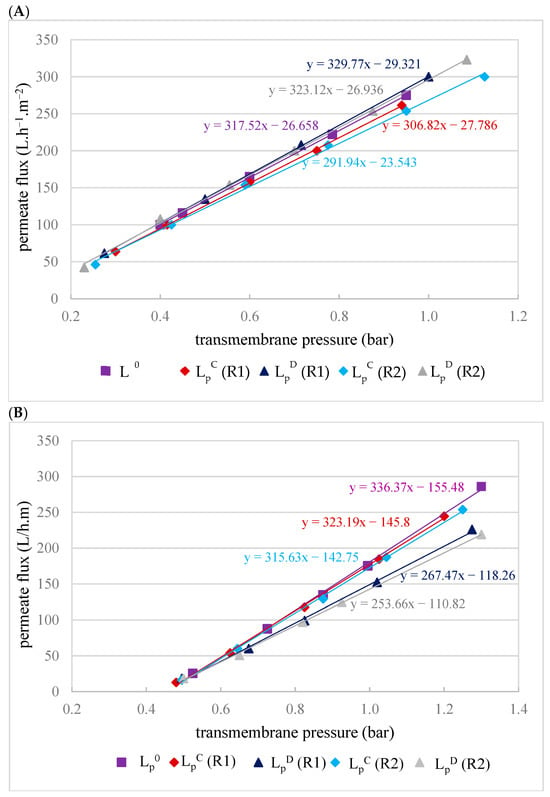

Evaluation of the impact of membrane fouling after filtrations was conducted by hydraulic permeability tests before each filtration and after each chemical cleaning. The results of these tests are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Hydraulic permeability of the MF500 (A) and MF200 (B) membranes before filtration (LP0), after chemical cleaning (LPC) and after drying of the membrane (LPD) for replicates R1 and R2.

Hydraulic permeability tests of the MF500 membrane conducted after each filtration, following a chemical cleaning (LPC), revealed 3–8% decrease in permeability (Figure 4A). Interestingly, after membrane drying (for conservation), subsequent tests (LPD) indicated almost full permeability recovery (LP0). In contrast, the MF200 membrane exhibited a distinct behavior. After chemical cleaning, its hydraulic permeability was almost fully restored (Figure 4B), indicating that the cleaning protocol was effective in removing membrane foulants. However, subsequent drying led to a decline in permeability, suggesting that the drying process adversely affected the membrane structure or surface properties, impairing its performance with an irreversible decrease in permeability of 20–25%.

3.8. Evaluation of the Impact of the Main Olive Juice Foulants on MF500 Membrane Performance

The main olive juice components that interact directly with membranes during tangential-flow filtration are suspended solids, colloids and smaller molecular mass dissolved species.

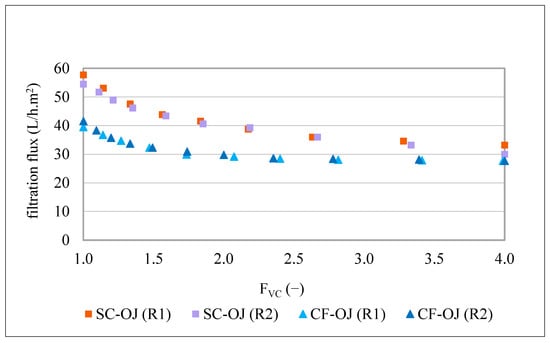

3.8.1. Impact of Olive Juice Suspended Solids on MF500 Membrane Fouling

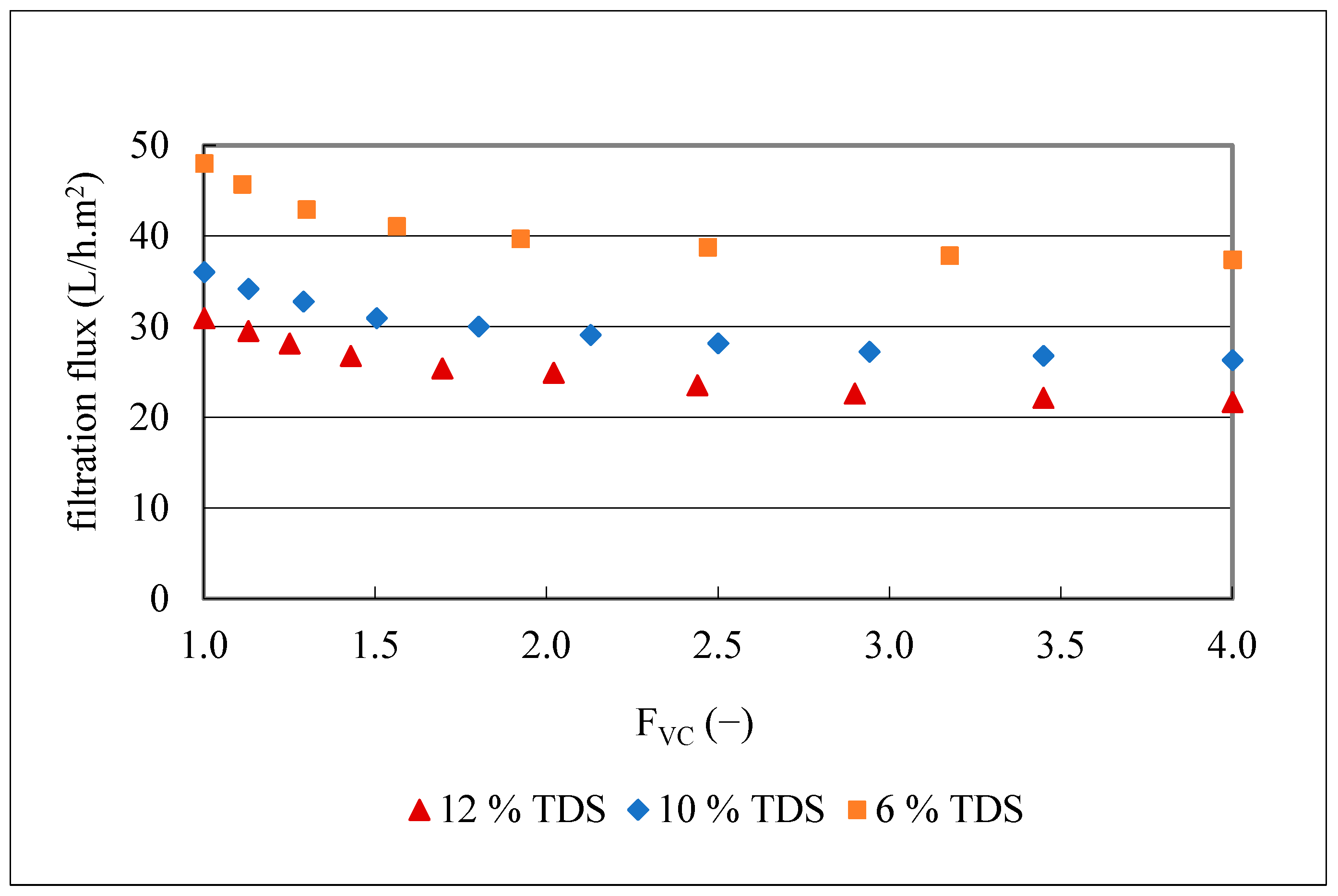

For better understanding of the contribution of the olive juice insoluble (suspended) particles to membrane fouling, two replicates of a semi-clarified olive juice (the 800 nm membrane permeates from the previous study [1]) were filtered by the MF500 membrane, under the same conditions of filtration (1.2 bar, 25 °C and FVC of 4). This semi-clarified olive juice (SC-OJ) had a TDS content of 6.2 g/100 mL, turbidity of 50–30 NTU and particle size distribution within the interval of 0.32–14.2 µm. The kinetics of the filtration fluxes of these treatments are presented in Figure 5. For easier comparison, the kinetics of the MF500 filtration fluxes of the two replicates of centrifuged olive juice (CF-OJ) (Figure 1) are included and all of them are presented as a function of the FVC.

Figure 5.

Flux kinetics produced during MF500 filtration of semi clarified (SC-OJ) and centrifuged (CF-OJ) olive juices (R1 and R2), at 1.2 bar, 25 °C, FVC = 4.

Filtration of the 800 nm membrane permeate, using the MF500 membrane started with fluxes of 58 and 55 L/h.m2 and concluded at 33 and 30 L/h.m2 for the two replicates, respectively. The initial filtration flux was noticeably higher than that obtained for centrifuged juices (40–42 L/h.m2). This is explained by the large difference in turbidity (8060–8490 NTU vs. 50–30 NTU), and TDS content (8.6–9.1 g/100 mL vs. 6.2 g/100 mL). However, the treatment resulted in a flux decline of 43 and 45%, which is considerably higher than the 30 and 33% decline observed during filtration of the centrifuged olive juices, despite the later containing larger suspended solid (0.33–739 µm) [1]. These findings suggest that particle size has a greater impact on fouling than particle load. Since the 800 nm membrane permeate was free of particles bigger than 14.2 µm, the smallest particles, specifically those comparable to the pore size of the MF500 membrane, appear responsible for the observed fouling. Moreover, the removal of larger particles may have aggravated this effect, as larger particles can mechanically score the membrane surface, preventing matter adhesion [34]. While this seems to contradict the utility of centrifugation, which primarily removes the largest particles, it is necessary in production contexts where residual oil exceeds 1%. Previous studies on tangential-flow MF of crude olive juices demonstrated that oily phase concentrations create stable emulsions under turbulent conditions, drastically reducing filtration efficiency. Thus, removing large particles and oil droplets via centrifugation improves net productivity.

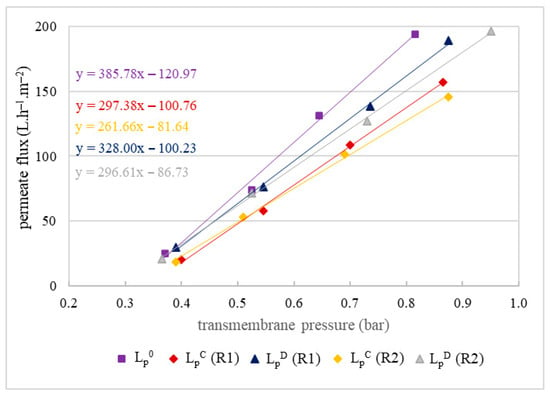

The results of the tests on the impact of suspended solids of the semi-clarified olive juice on the MF500 membrane fouling are presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Hydraulic permeability of the MF500 membrane before filtration (LP0), after chemical cleaning (LPC) and after drying of the membrane (LPD) for replicates R1 and R2 of the semi-clarified juice (the permeate of the 800 nm pore size membrane).

These results revealed another important decrease in permeability of 23–32% (Figure 6). What appeared new in this case was that membrane drying led only to partial recovery of permeability, leaving an irreversible decrease of 15–23%. This decrease was also notably higher than that observed during the filtration of the centrifuged olive juices, confirming the hypothesis that the membrane fouling is more strongly impacted by particle size than by particle amount.

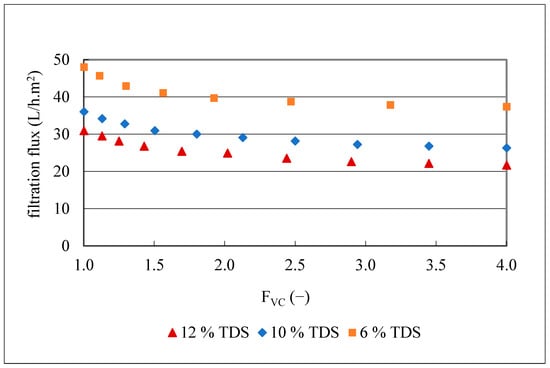

3.8.2. Impact of Total Dissolved Substances on MF500 Membrane Fouling

To better understand the impact of TDS on membrane fouling, filtrations of 20 L of olive juice with three different TDS contents (12.4, 10.0 and 6.4 g/100 mL), but with turbidities of 3900–4200 NTU were conducted with the MF500 membrane at 1.2 bar, 25 °C and FVC of 4. The kinetics of the obtained filtration fluxes are presented in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Flux kinetics during MF500 membrane filtration of three olive juices with different total dissolved substances (TDS) and same turbidity of 3900–4200 NTU.

The obtained results (Figure 7) indicate a clear decrease in the initial filtration flux with increasing TDS content. Specifically, flux dropped from 31 to 21.7 L/h.m2 for the juice with the highest TDS content (12.4 g/100 mL), from 36 to 26.3 L/h.m2 for the juice with 10 g/100 mL TDS content and from 48 to 37 L/h.m2, for the juice with the lowest TDS content (6.4 g/100 mL), corresponding to flux losses of 30, 27 and 22%, respectively. The 2-fold decrease in TDS content from 12 to 6 g/100 mL resulted in a mean 1.6-fold increase in filtration flux and an 8% decrease in flux loss. Since one of the main factors that affects the filtration flux is the juice viscosity (Darcy’s law) [51], samples with different concentrations of TDS were prepared from the clarified olive juice as described in Section 2.4.7 and plotted vs. their viscosity (Figure 8).

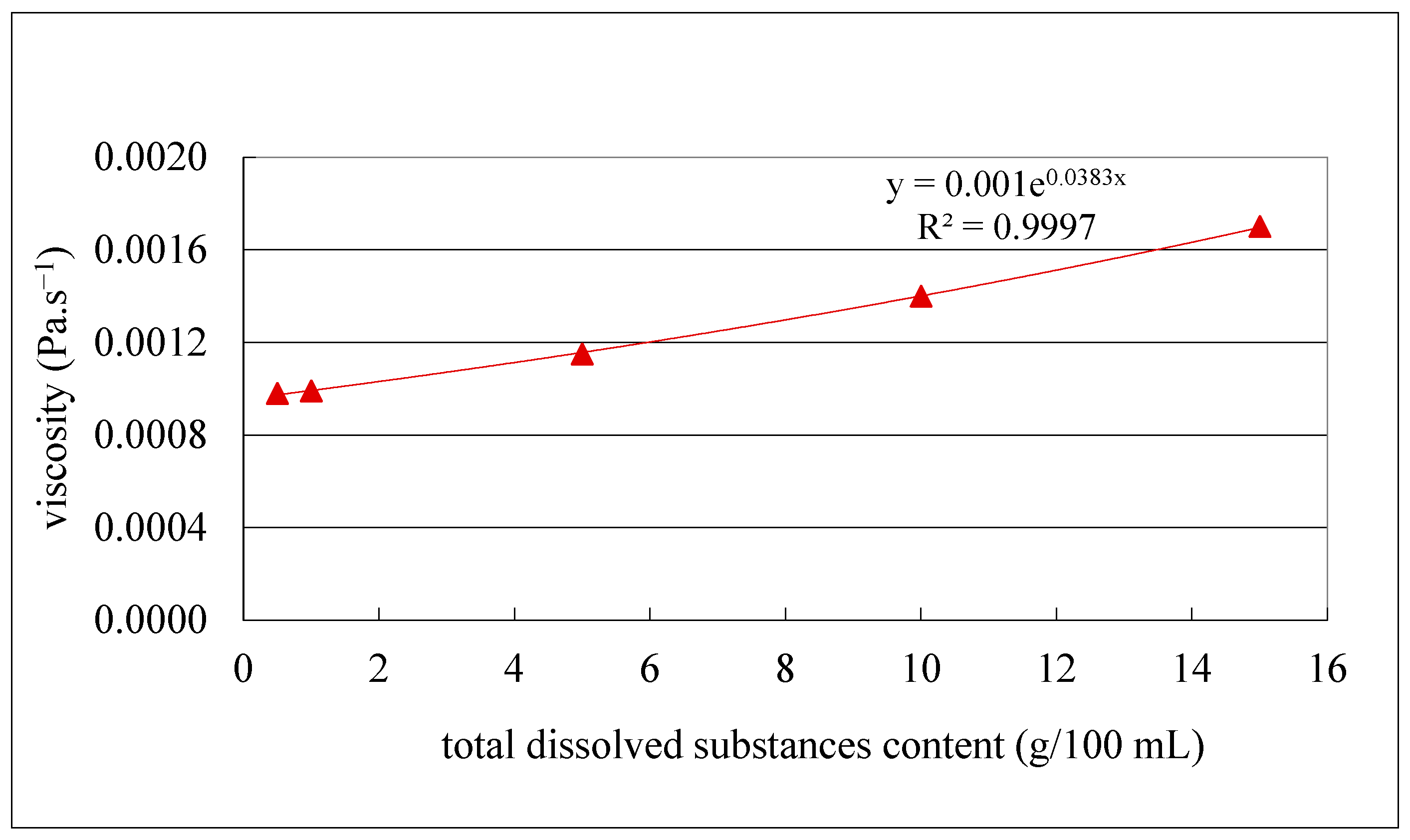

Figure 8.

Viscosity as a function of total dissolved substance content of the clarified olive juice.

The results revealed a very high logarithmic correlation (R2 = 0.9996) (Figure 8), indicating that the 2-fold decrease in TDS content (from 12 to 6 g/100 mL) resulted in only a 1.3-fold increase in viscosity (from 0.0012 to 0.00152 Pa/s). This suggests that the remaining contribution to the viscosity increase is attributable to other factors, likely related to the total resistance to the filtration flux, as previously reported [52]. In addition, hydraulic permeability tests of the MF500 membrane before each filtration and after each chemical cleaning and membrane drying were also carried out. The results of the tests are presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Hydraulic permeability of the MF500 membrane before filtration (LP0), after chemical cleaning (LPC) and after drying of the membrane (LPD) of olive juices with total dissolved substance content of 12, 10 and 6 g/100 mL.

Hydraulic permeability tests conducted after chemical cleaning of the MF500 membrane (Figure 9) revealed a progressive loss of permeability among the three treatments. Notably, the flux recovery attributed to membrane drying diminished, with permeability decreasing by up to 37% after the third filtration/cleaning cycle (Figure 4A). This indicates irreversible fouling, likely due to pore blocking by colloids and the finest insoluble particles. To mitigate colloid-induced fouling, enzymatic hydrolysis of pectin and protein fractions, the most abundant colloids in olive juices, may be effective. Therefore, it would first be important to evaluate the most active available enzymes, especially those that function at room temperature [52]. To address fouling by fine particles, two strategies may be considered. First, hydraulic cleaning techniques, such as backflushing could be employed to reduce the negative effect of the finest particles. Second, optimizing industrial separation by using a 3-phase decanter to maximize oil recovery could enable direct membrane clarification of olive juice (without centrifugation). This would retain larger particles in the feed, potentially enhancing the surface-sweeping effect mentioned earlier [34].

4. Conclusions

Both studied membranes operated efficiently at a relatively low tangential-flow velocity of 2.5 m/s. The 500 nm membrane achieved higher fluxes and shorter processing times than the 200 nm membrane when filtering the same volumes. Importantly, both membranes produced high quality clarified juices, characterized by turbidities below 2 NTU, complete oil removal, and no detectable retention of phenolic and secoiridoid compounds or their conjugates. These results demonstrate the superior performance of the 500 nm pore size membrane and support the use of large pore high filtration density MF membranes as a promising alternative to mineral membranes with smaller pores and wider channels, as well as to organic polymer membranes. However, prolonged operation led to a progressive decline in membrane permeability, which was related to irreversible fouling, caused by the smallest suspended particles and macromolecular colloids. Regarding suspended solids, particle size has a greater impact on fouling than particle load. Further research should focus on strategies to mitigate fouling through enzymatic hydrolysis of macromolecules and selective separation of the smallest particles. This study also confirms that not only α-Al2O3 membranes but also mixed oxide ones can induce a spontaneous increase in the concentrations of phenolic and secoiridoid compounds, as well as some of their conjugates. This effect appears to depend more on the initial composition of the olive juice than on membrane pore size alone. Further research is required to elucidate the underlying mechanisms responsible for this phenomenon and to determine the specific role of each contributing factor. In all cases, it can be considered as an additional benefit of clarified olive juices.

Author Contributions

A.G.-D.: Writing—original draft and review & editing, Investigation, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. A.R.-R.: Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition. M.P.: Writing—review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Methodology, Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We thank the Consejería de Educación e Investigación from Comunidad de Madrid for the financial support of this study and the PhD contract (IND2022/BIO-23619) of Alba Gutiérrez-Docio.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge also Juan Fernández-Bolaños from Instituto de la Grasa (CSIC) (Sevilla, Spain) for the kind supply of 3,4-DHPG reference substance, Diego Arroyo, director of the olive oil mill ‘Matías Arroyo Moñino e hijos’ from Navalvillar de Pela, Badajoz (Spain) for the supply of olive juice, José María Pérez Morales, director of the olive oil mill ‘Labranza Toledana’ from Los Navalmorales, Toledo (Spain) for the supply of semi-skimmed olive paste (alpeorujo) and Luis Fernando Torrijos de Yepes for improving the understanding of the original English version of the manuscript. During the preparation of this work, the authors used ChatGPT 4o only to improve the readability of the Introduction and Results and Discussion sections of the manuscript. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gutiérrez-Docio, A.; Ruiz-Rodriguez, A.; Prodanov, M. Clarification of olive juice by α-alumina microfiltration membranes with enhanced packing density. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2025, 102, 104031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinigaglia, M.; Di Benedetto, N.; Bevilacqua, A.; Corbo, M.R.; Capece, A.; Romano, P. Yeast isolated from olive mil wastewaters from southern Italy: Technological characterization and potential use for phenol removal. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010, 87, 2345–2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leonardis, A.; Masino, F.; Macciola, V.; Montevecchi, G.; Antonelli, A.; Marconi, E. A study on acetification process to produce olive vinegar from oil mil wastewaters. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2019, 245, 2123–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvan, J.M.; Pinto-Bustillos, M.A.; Vázquez-Ponce, P.; Prodanov, M.; Martínez-Rodríguez, A.J. Olive mill wastewater as potential source of antibacterial and anti-inflammatory compounds against the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 51, 177–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamrah, A.; Al-Zghoul, T.M.; Darwish, M.M. A comprehensive review of combined processes for olive mill wastewater treatments. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2023, 8, 100493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ORIVA. Dosier Informativo, Asociación Interprofesional del Aceite de Orujo de Oliva. Available online: https://oriva.es/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ORIVA-dossier-prensa-2025.pdf (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Hernández, D.; Quinteros-Lama, H.; Tenreiro, C.; Gabriel, D. Assessing concentration changes of odorant compounds in the thermal-mechanical drying phase of sediment-like wastes from olive oil extraction. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 519. [Google Scholar]

- la Cruz, F.J.G.-D.; Casanova-Peláez, P.J.; Palomar-Carnicero, J.M.; Cruz-Peragón, F. Characterization and analysis of the drying real process in an industrial olive-oil mill waste rotary dryer: A case of study in Andalusia. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 116, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federici, F.; Fava, F.; Kalogeralis, N.; Mantzavinos, D. Valorisation of agro-industrial by-products, effluents and waste: Concept, opportunities and the case of olive mill wastewaters. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2009, 84, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzarelli, F.; Piacentini, E.; Poerio, T.; Mazzei, R.; Cassano, A.; Giorno, L. Advances in membrane operations for water purification and biophenols recovery/valorization from OMWWs. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 497, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guizard, C.; Stevenson, A. Ceramic membranes technology, current applications and future development. In Handbook of Membrane Separations, Chemical, Pharmaceutical, Food, and Biotechnological Applications; Pabby, A.K., Rizvi, S.S.H., Sastre, A.M., Eds.; CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 215–257. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Lyu, Z.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, L.; Wang, J. Ceramic-based membranes for water and wastewater treatment. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 578, 123513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PIMEMBRAHCBEN. Membralox Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.pall.com/content/dam/pall/chemicals-polymers/literature-library/non-gated/PIMEMBRAHCBEN.pdf (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Lee, M.; Wu, Z.; Li, K. Advances in ceramic membranes for water treatment. In Advances in Membrane Technologies for Water Treatment, Materials, Processes and Applications; Basil, A., Cassano, A., Rastogi, N., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 43–82. [Google Scholar]

- Stobbe, P.; Bishop, B.; Goldsmith, R.L. Cross-Flow Filtration Device with Filtrate Conduit Network and Method of Making Same. US Patent 6126833A, 3 October 2000. [Google Scholar]

- V03/03/21. CeraMem Technical Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.alsys-group.com/app/uploads/2021/03/alsys-us0602-ceramem-ceramic-membranes-and-modules-data-sheet-v03.21-5.pdf (accessed on 11 July 2025).

- Dornier, M.; Belleville, M.P.; Vaillant, F. Membrane technologies for fruit juice processing. In Fruit Preservation: Novel and Conventional Technologies; Rosenthal, A., Deliza, R., Welti-Chanes, J., Barbosa-Cánovas, G.V., Eds.; Springer Science + Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 211–248. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Lau, E.; Padilla-Zakour, O.I.; Moraru, C.I. Role of pectin and haze particles in membrane fouling during cold microfiltration of apple cider. J. Food Eng. 2017, 200, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crittenden, J.C.; Trussell, R.R.; Hand, D.W.; Howe, K.J.; Tchobanoglous, G. Membrane filtration. In MWH’s Water Treatment: Principles and Design, 3rd ed.; Crittenden, J.C., Trussell, R.R., Hand, D.W., Howe, K.J., Tchobanoglous, G., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012; pp. 819–902. [Google Scholar]

- Voutchkov, N.; Semiat, R. Seawater desalination. In Advanced Membrane Technology and Applications; Li, N.N., Fane, A.G., Winston Ho, W.S., Matsuura, T., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2008; pp. 47–86. [Google Scholar]

- Eray, E.; Candelario, V.M.; Boffa, V.; Safafar, H.; Østedgaard-Munck, D.N.; Zahrtmann, N.; Kadrispahic, H.; Jørgensen, M.K. A roadmap for the development and applications of silicon carbide membranes for liquid filtration: Recent advancements, challenges, and perspectives. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 414, 128826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Xu, C.; Rakesh, K.P.; Cui, Y.; Yin, J.; Chen, C.; Wang, S.; Chen, B.; Xhu, L. Hydrophilic SiC hollow fiber membranes for low fouling separation of oil-in-water emulsions with high flux. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassano, A.; Conidi, C.; Drioli, E. Clarification and concentration of pomegranate juice (Punica granatum L.) using membrane processes. J. Food Eng. 2011, 107, 366–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanz, M.; de Simón, B.F.; Cadahía, E.; Esteruelas, E.; Muñoz, A.M.; Hernández, T.; Estrella, I.; Pinto, E. LC-DAD/ESI-MS/MS study of phenolic compounds in ash (Fraxinus excelsior L. and F. americana L.) heartwood. Effect of toasting intensity at cooperage. J. Mass Spectrom. 2012, 47, 905–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvan, J.M.; Guerrero-Hurtado, E.; Gutiérrez-Docio, A.; Alarcon-Cavero, T.; Prodanov, M.; Martinez-Rodriguez, A.J. Olive leaf extracts modulate inflammation and oxidative stress associated with human H. pylori infection. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mulinacci, N.; Innocenti, M.; La Marca, G.; Mercalli, E.; Giaccherini, C.; Romani, A.; Erica, S.; Vincieri, F.F. Solid olive residues: Insight into their phenolic composition. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 8963–8969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innocenti, M.; la Marca, G.; Malvagia, S.; Giaccherini, C.; Vincieri, F.F.; Mulinacci, N. Electrospray ionisation tandem mass spectrometric investigation of phenylpropanoids and secoiridoids from solid olive residue. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2006, 20, 2013–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Senent, F.; Rodríguez-Gutíerrez, G.; Lama-Muñoz, A.; Fernández-Bolaños, J. New phenolic compounds hydrothermally extracted from the olive oil byproduct alperujo and their antioxidative activities. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012, 60, 1175–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genovese, D.B.; Lozano, J.E. Effect of cloud particle characteristics on the viscosity of cloudy apple juice. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 641–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girard, B.; Fukumoto, L.R. Membrane processing of fruit juices and beverages: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2000, 40, 91–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, C. A new membrane process for the selective fractionation and total recovery of polyphenols, water and organic substances from vegetation waters (VW). J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 288, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Castello, E.; Cassano, A.; Criscuoli, A.; Conidi, C.; Drioli, E. Recovery and concentration of polyphenols from olive mil wastewaters by integrated membrane system. Water Res. 2010, 44, 3883–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gan, Q.; Howell, J.A.; Field, R.W.; England, R.; Bird, M.R.; O’Shaughnessy, C.L.; MeKechinie, M.T. Beer clarification by microfiltration–product quality control and fractionation of particles and macromolecules. J. Membr. Sci. 2001, 194, 185–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; Lau, E.; Huang, S.; Moraru, C.I. The effect of apple cider characteristics and membrane pore size on membrane fouling. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 974–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, F.; Millan, A.; Dornier, M.; Decloux, M.; Reynes, M. Strategy for economical optimization of the clarification of pulpy fruit juices using crossflow microfiltration. J. Food Eng. 2001, 48, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vierhuis, E.; Korver, M.; Schols, H.A.; Voragen, A.G.J. Structural characteristics of pectic polysaccharides from olive fruit (Olea europaea cv moraiolo) in relation to processing for oil extraction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2003, 51, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanakis, C.M.; Tornberg, E.; Gekas, V. A study of the recovery of the dietary fibres from olive mill wastewater and the gelling ability of the soluble fibre fraction. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2010, 43, 1009–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çaliş, İ. Biodiversity of phenylethanoid glycosides. In Biodiversity: Biomolecular Aspects of Biodiversity and Innovative Utilization; Şener, B., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2002; pp. 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Z.; Yang, B. Phenylethanoid glycosides: Research advances in their phytochemistry, pharmacological activity and pharmacokinetics. Molecules 2016, 21, 991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Feng, S.; Song, X.; Guo, T.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Q. The oleoside-type secoiridoid glycosides: Potential secoiridoids with multiple pharmacological activities. J. Mol. Struct. 2023, 1283, 135286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, S.M.; Falcão, S.I.; Peres, A.M.; Domingues, M.R.M. Oleuropein/ligstroside isomers and their derivatives in Portuguese olive mill wastewaters. Food Chem. 2011, 129, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]