Direct Contact Membrane Distillation: A Critical Review of Transmembrane Heat and Mass Transfer Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

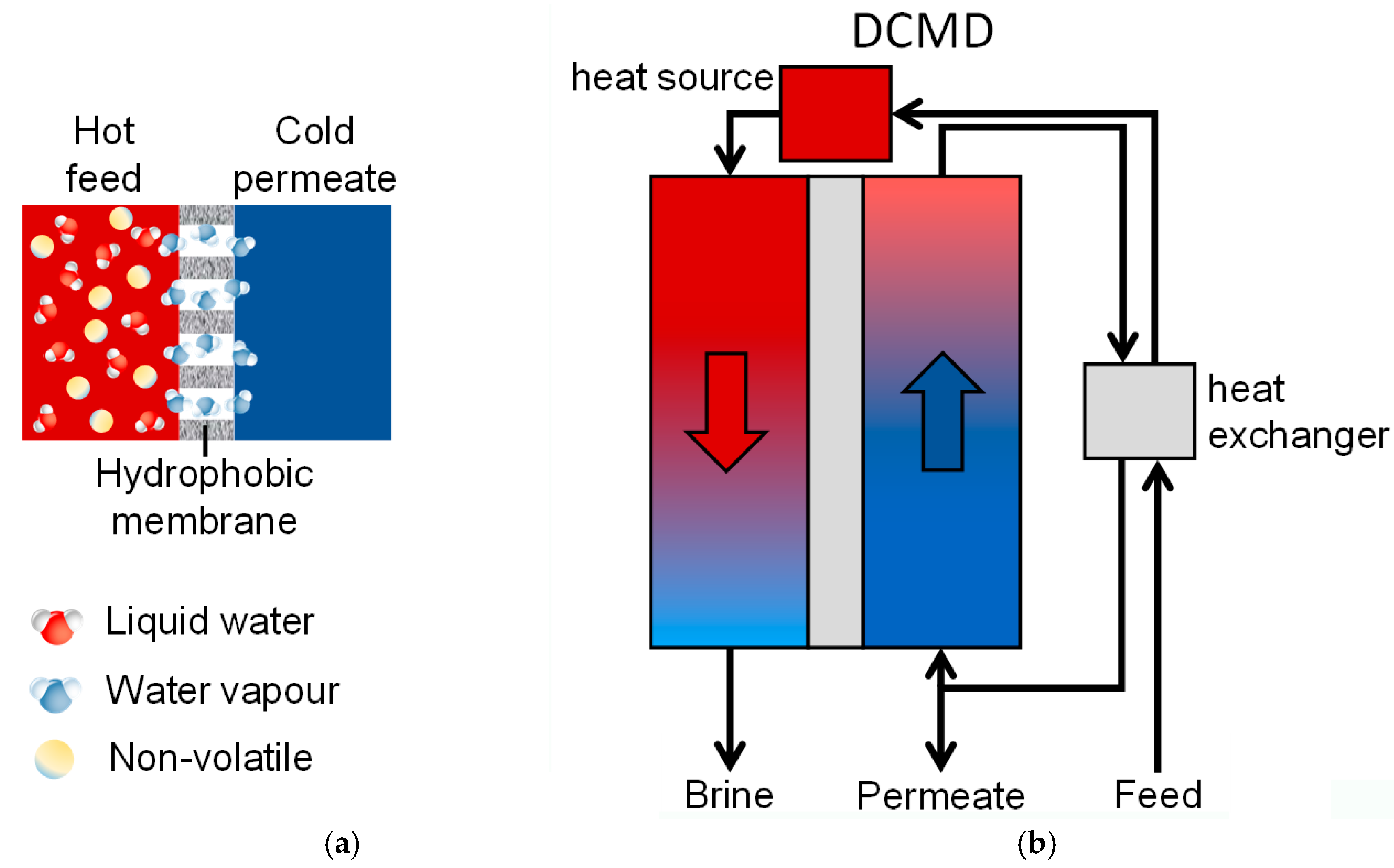

- Direct Contact MD (DCMD), where both the feed and permeate liquids are in direct contact with the membrane (Figure 1b);

- -

- Air Gap MD (AGMD), where an air layer between the membrane and condensation surface serves as a barrier;

- -

- Sweep Gas MD (SGMD), which uses a carrier gas to sweep vapor out of the membrane module to an external condenser;

- -

- Vacuum MD (VMD), where a vacuum on the permeate side draws vapor, which then condenses externally.

2. Thermophysical Properties of Salt Water

- -

- Salinity S, or mass fraction, is defined as the ratio of mass of salt to mass of solution and, of course, is dimensionless and insensitive to the mass units adopted, provided they are the same for salt and the solution (although it is often measured in g/kg, i.e., as 1000·S, in percent, i.e., as 100·S, or in ppm, or parts per million, i.e., as 106 S).

- -

- Molar fraction x is defined as the ratio of moles of salt to moles of solution (water + salt) and thus, like the salinity, it is dimensionless. The quantity x is related to S as follows:in which MWw and MWs are the molecular weights of water and salt, expressed, as is usual, in g/mol (18 and 58.44, respectively).

- -

- Molality m is defined as the ratio of moles of salt to the mass of water, expressed in mol/kg. It is related to the above-defined salinity S as follows:

- -

- Molarity M is defined as the ratio of moles of salt to volume of solution. If expressed, as is usual, in mol/L, it is related to the above-defined salinity S as follows:in which ρ(S) is the density of the solution of salinity S, expressed in kg/m3, as discussed below.

- -

- Finally, for computational purposes, it may be preferable to express the molar concentration in moles of salt per cubic meter of solution rather than per liter, using the molar concentration C related to molarity M as follows:

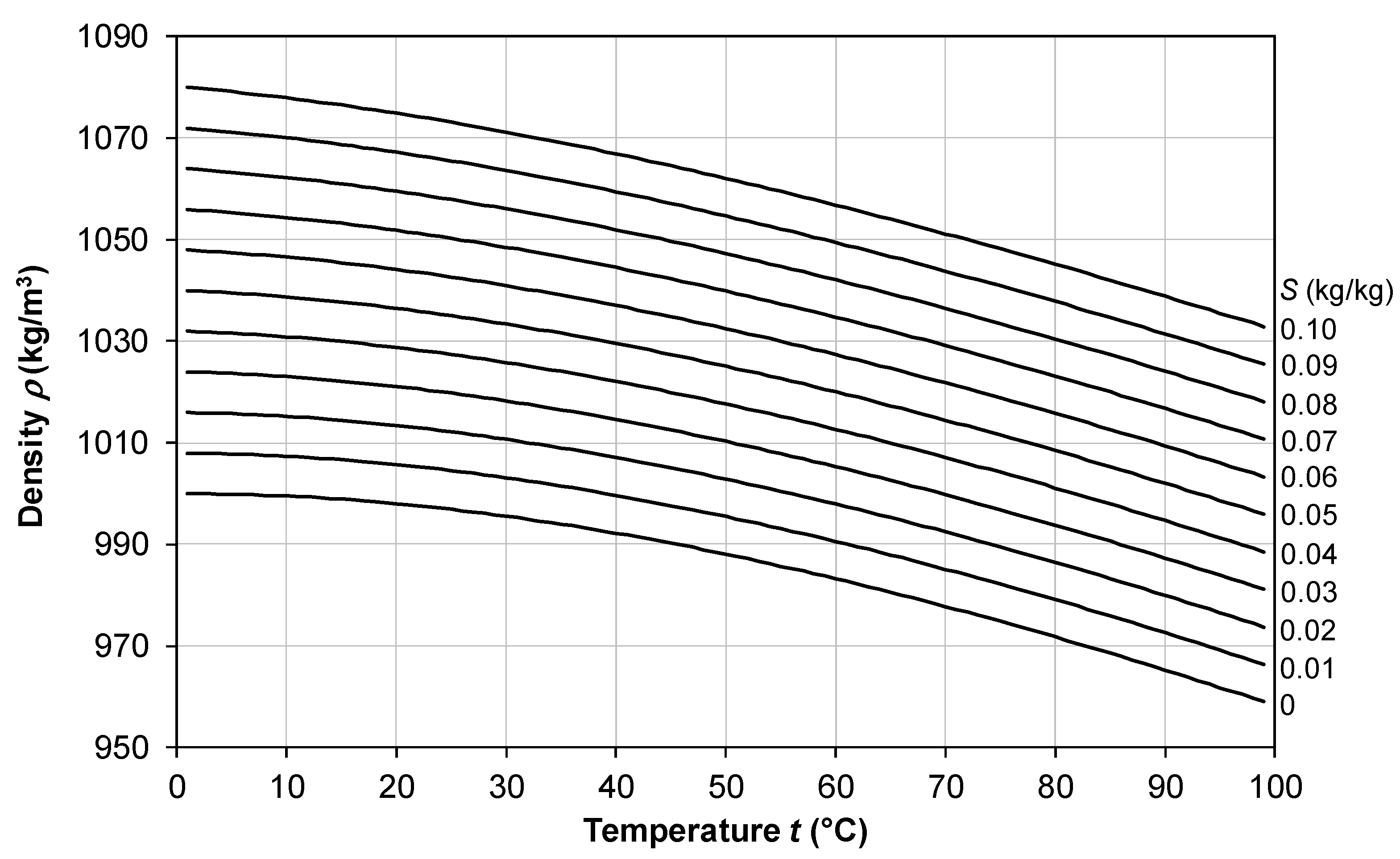

2.1. Density

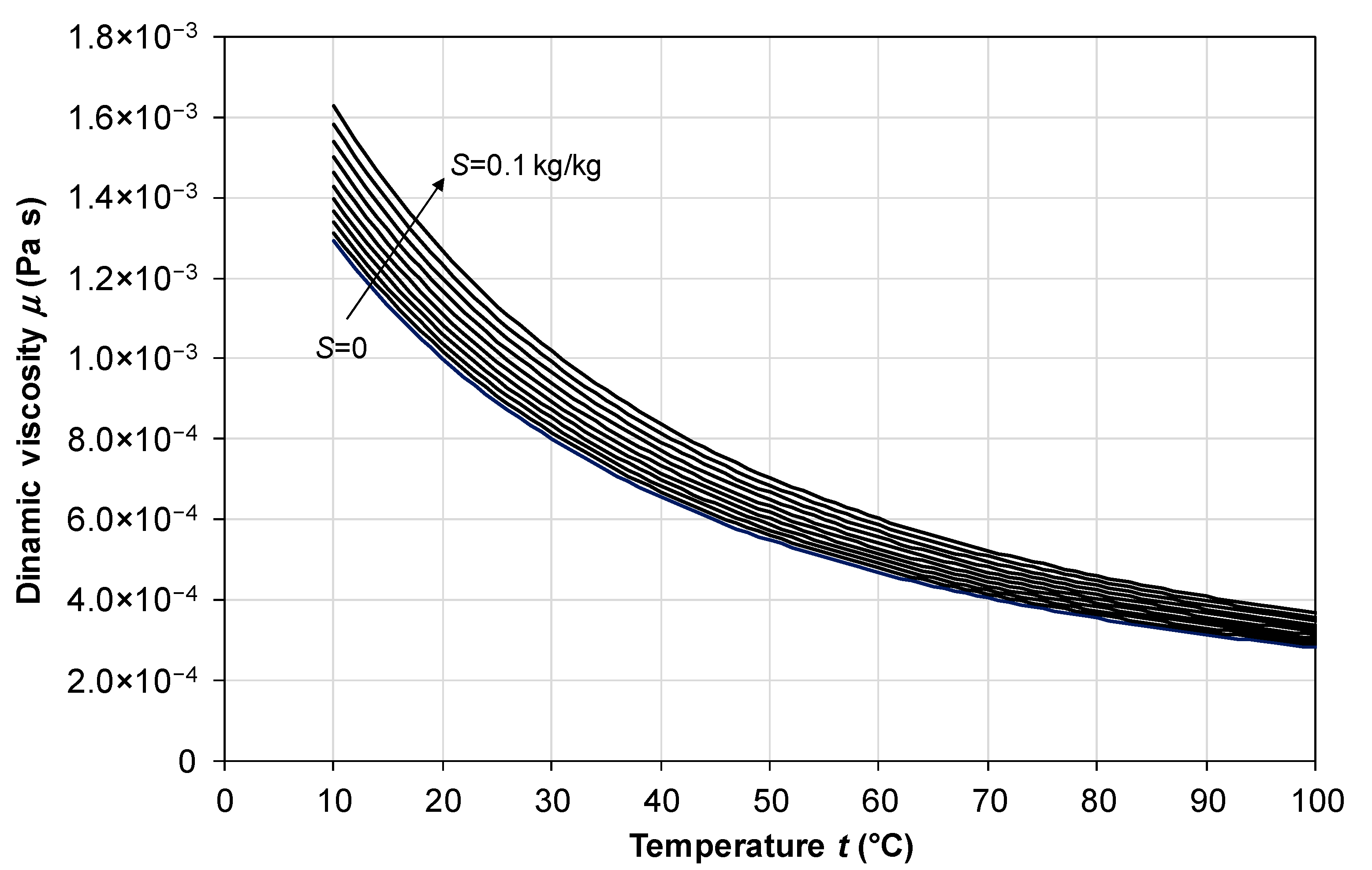

2.2. Dynamic Viscosity

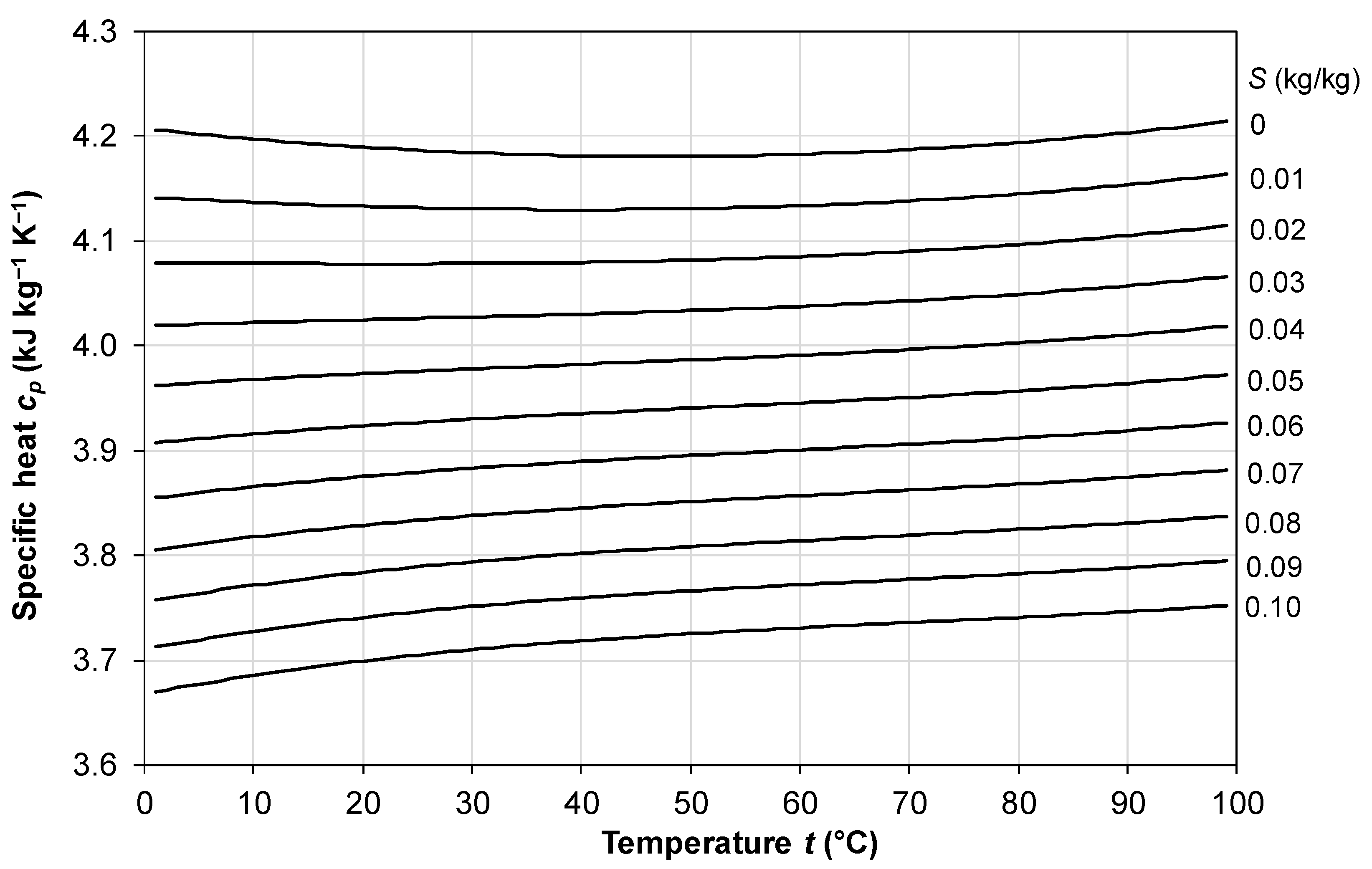

2.3. Specific Heat Capacity

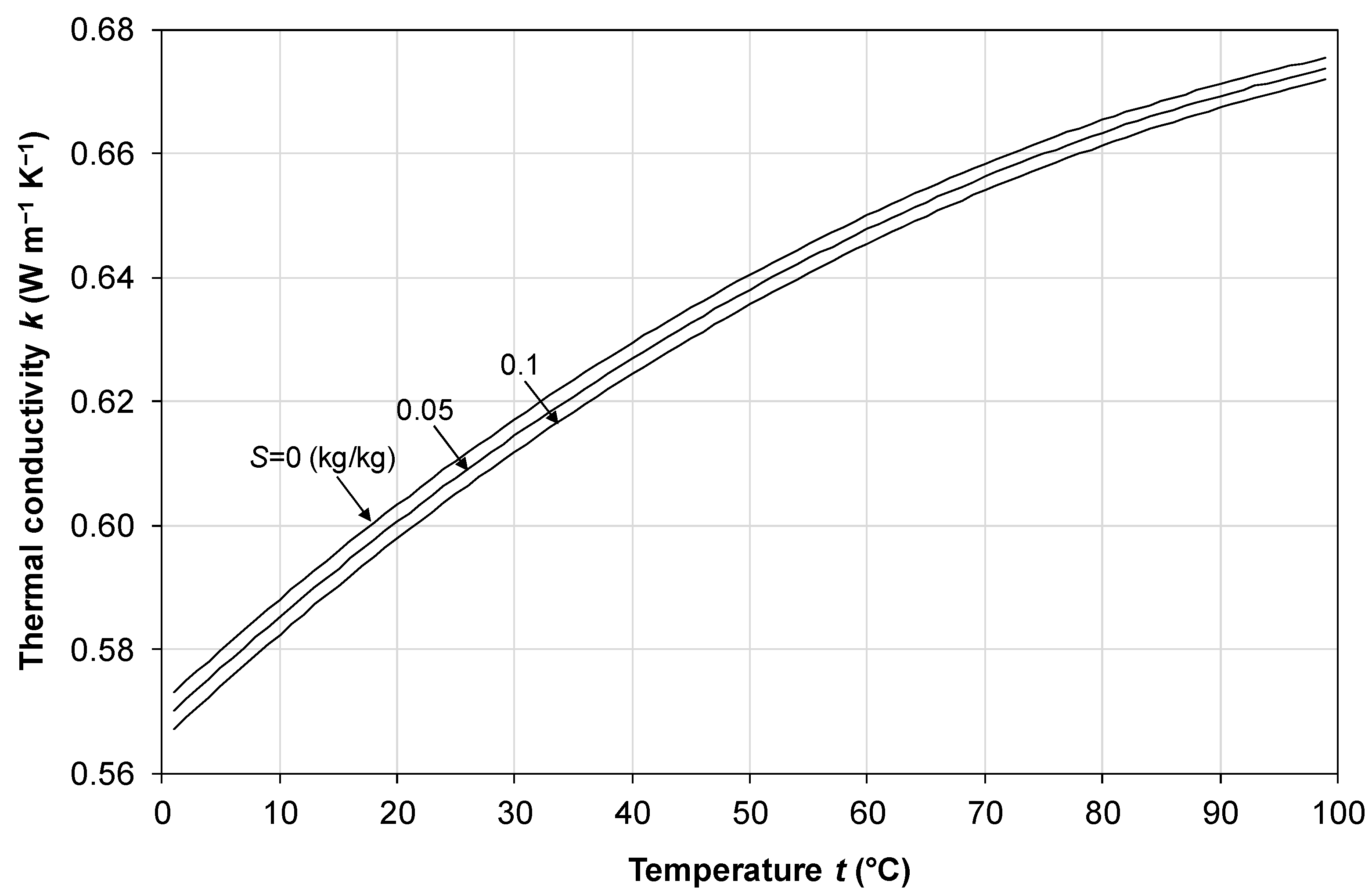

2.4. Thermal Conductivity

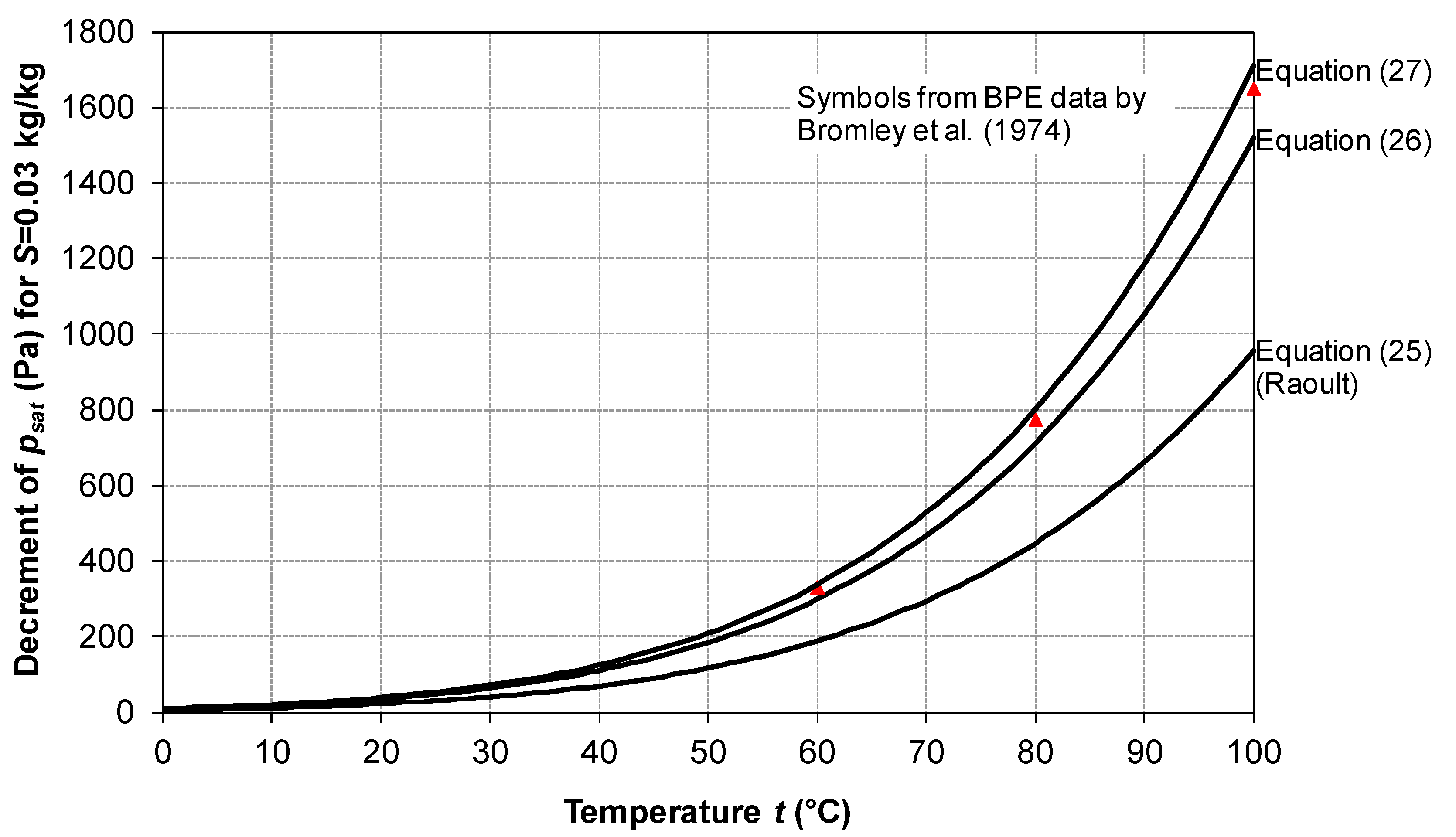

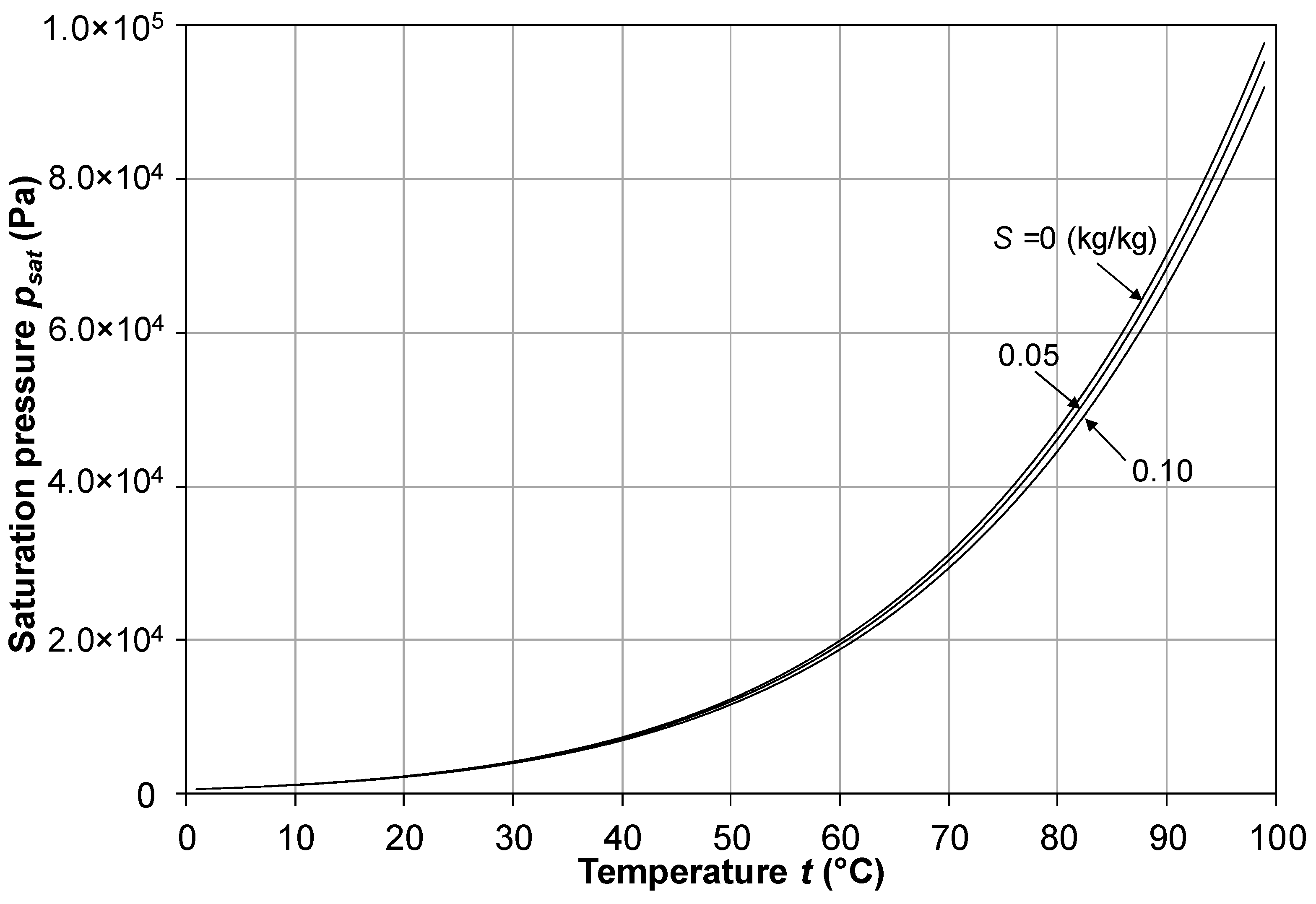

2.5. Vapor Saturation Pressure

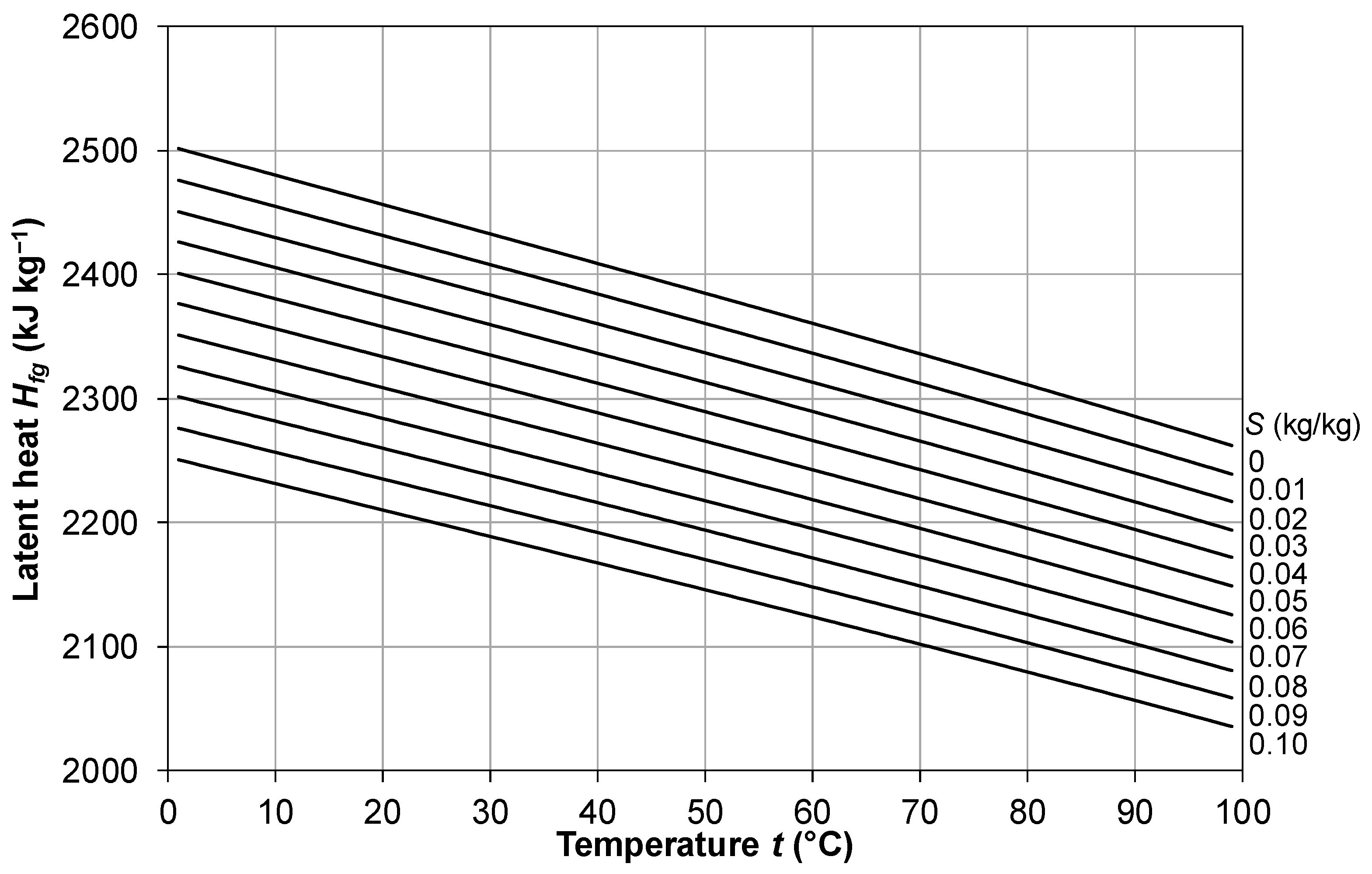

2.6. Latent Heat of Vaporization

3. Membrane Morphology and Properties

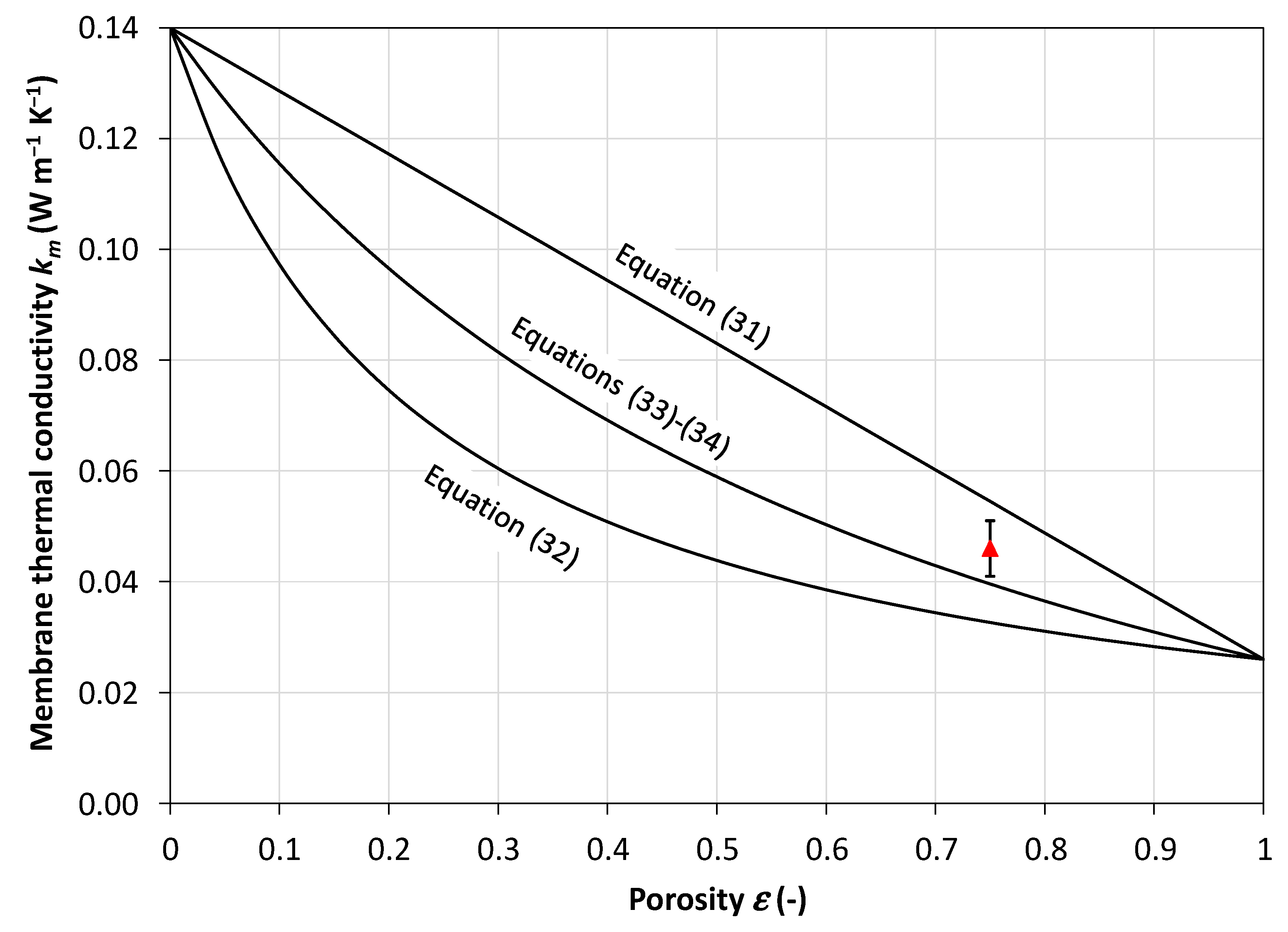

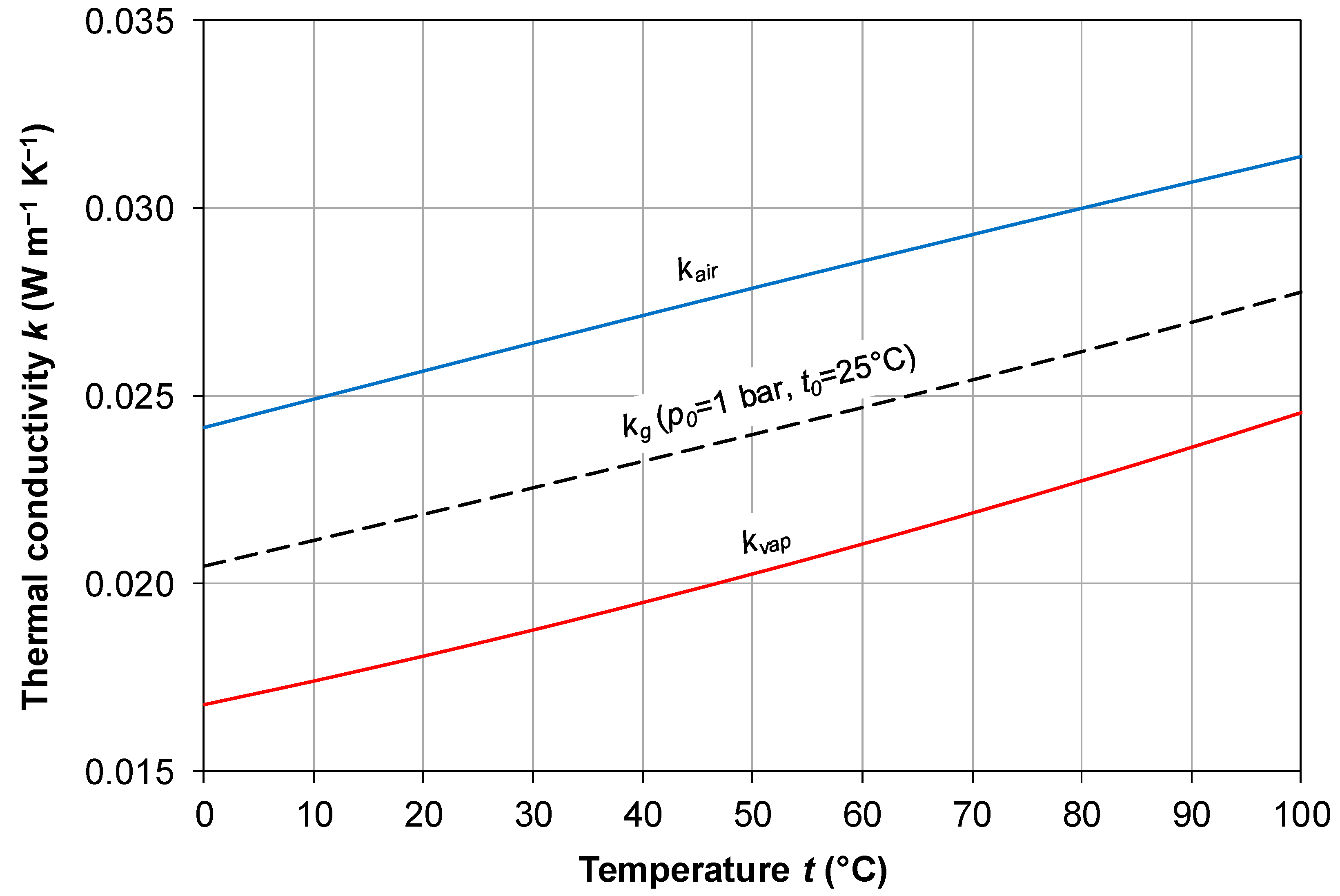

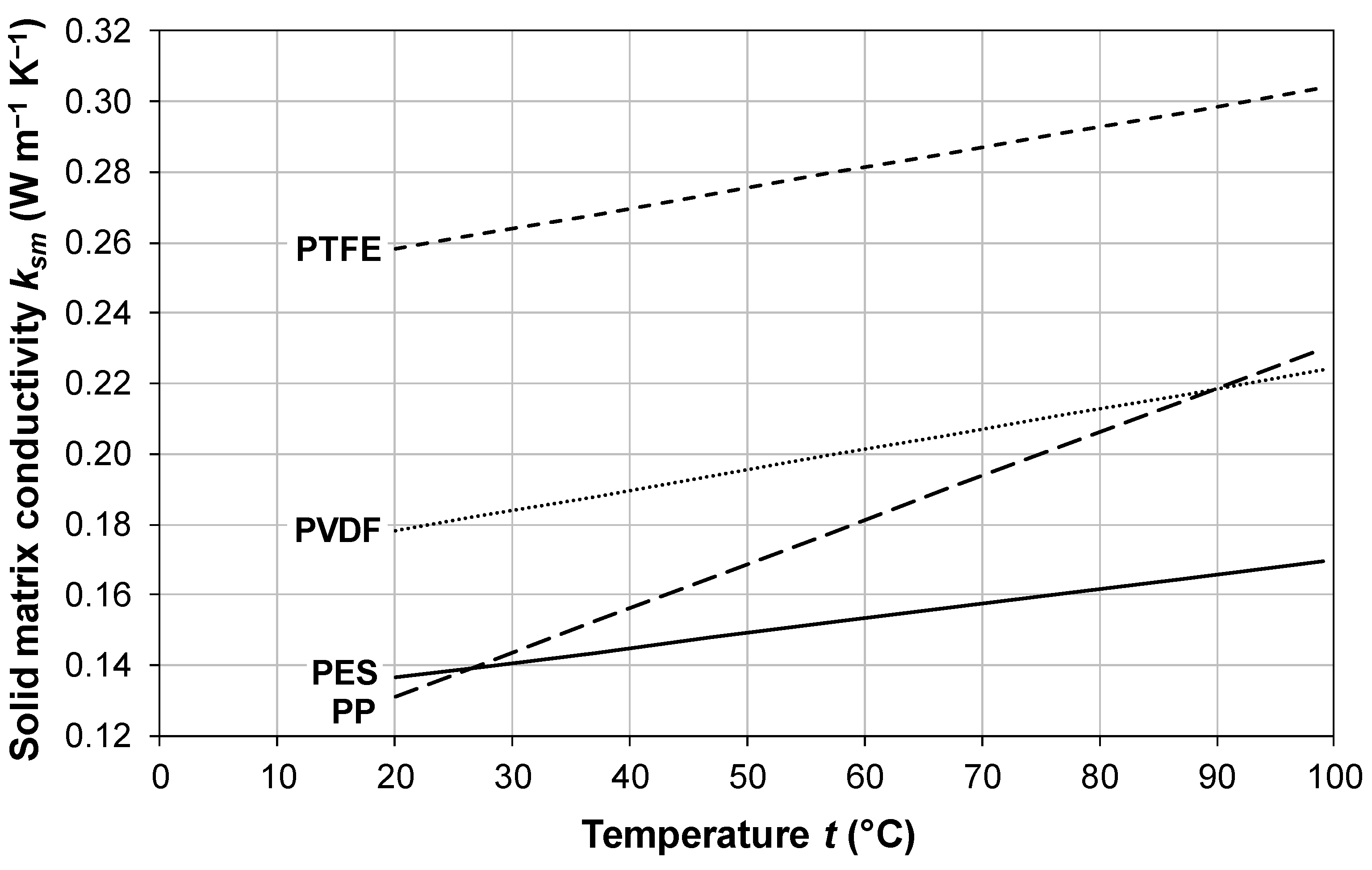

3.1. Membrane Thermal Conductivity

3.2. Pore Size and Its Distribution

3.3. Membrane Porosity and Pore Tortuosity

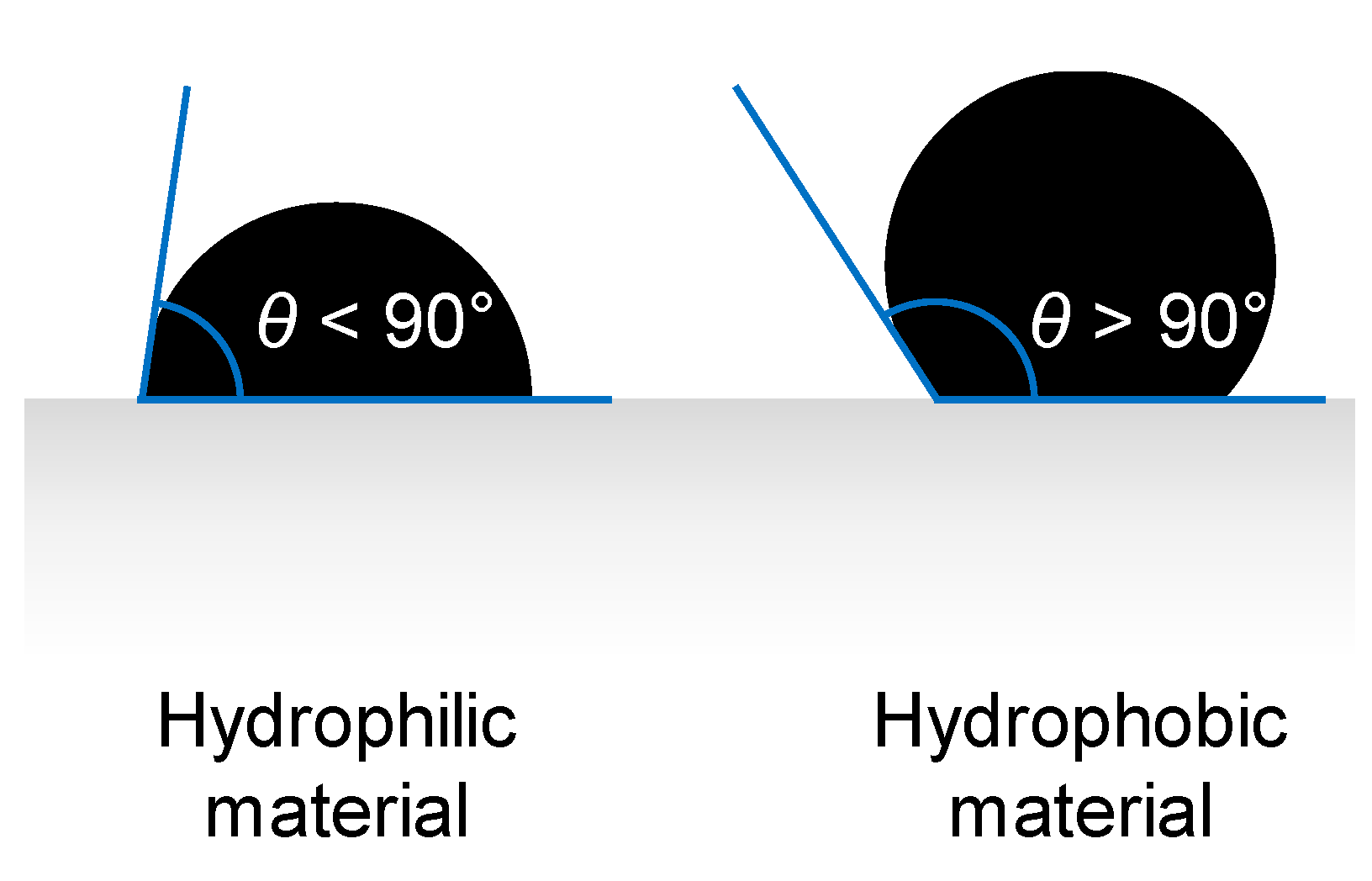

3.4. Liquid Entry Pressure

4. Transmembrane Mass Transfer

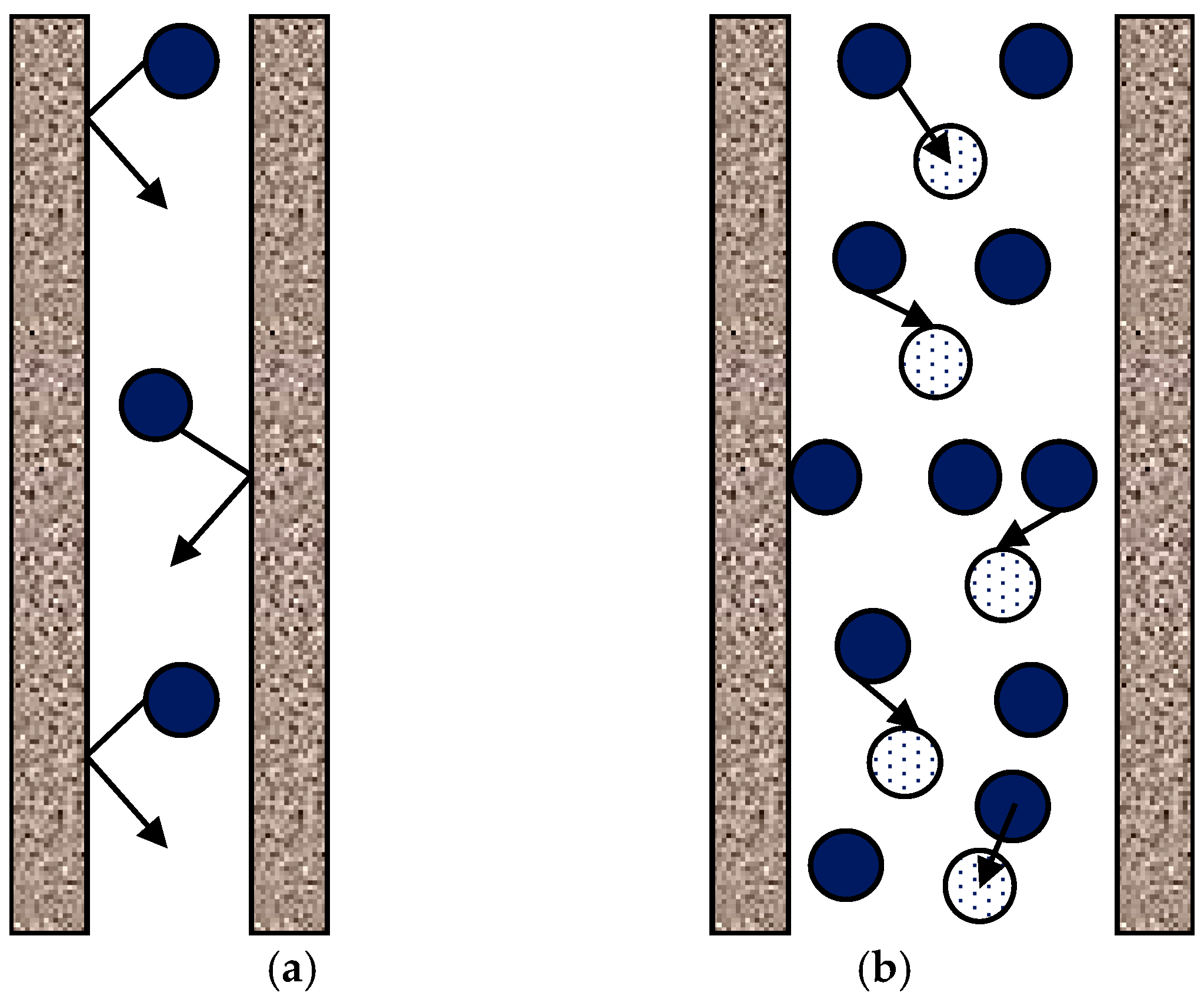

4.1. Case I (Small Pores, Knudsen Regime): dp < λ or Kn > 1

4.2. Case II (Large Pores, Diffusion Regime): dp > 100λ or Kn < 0.01

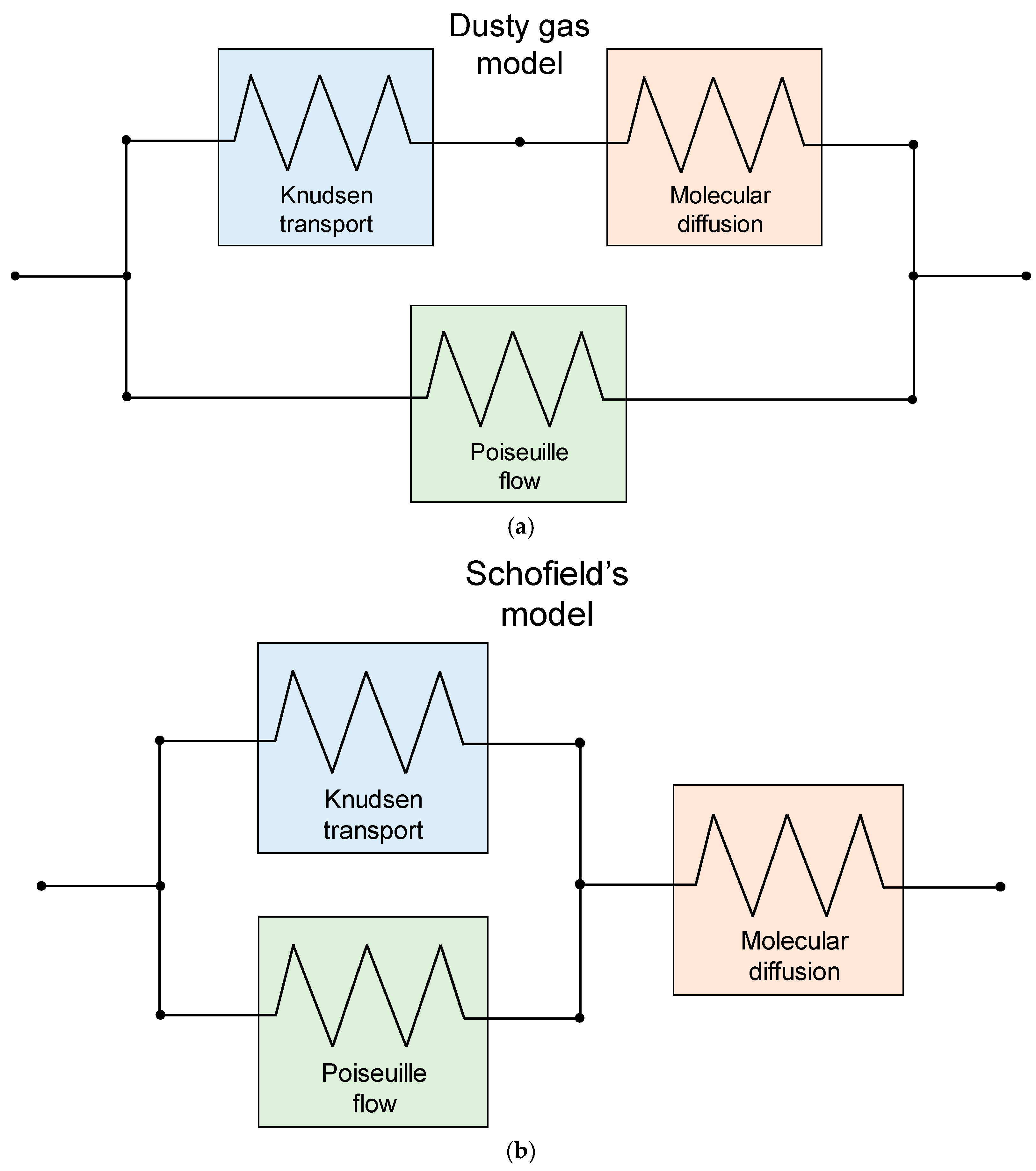

4.3. Case III (Intermediate Pore Size, Transitional Regime): λ < dp < 100λ or 0.01 ≤ Kn ≤ 1

4.4. Contribution of Poiseuille Flow

4.5. Experimental Validation of Permeance Models

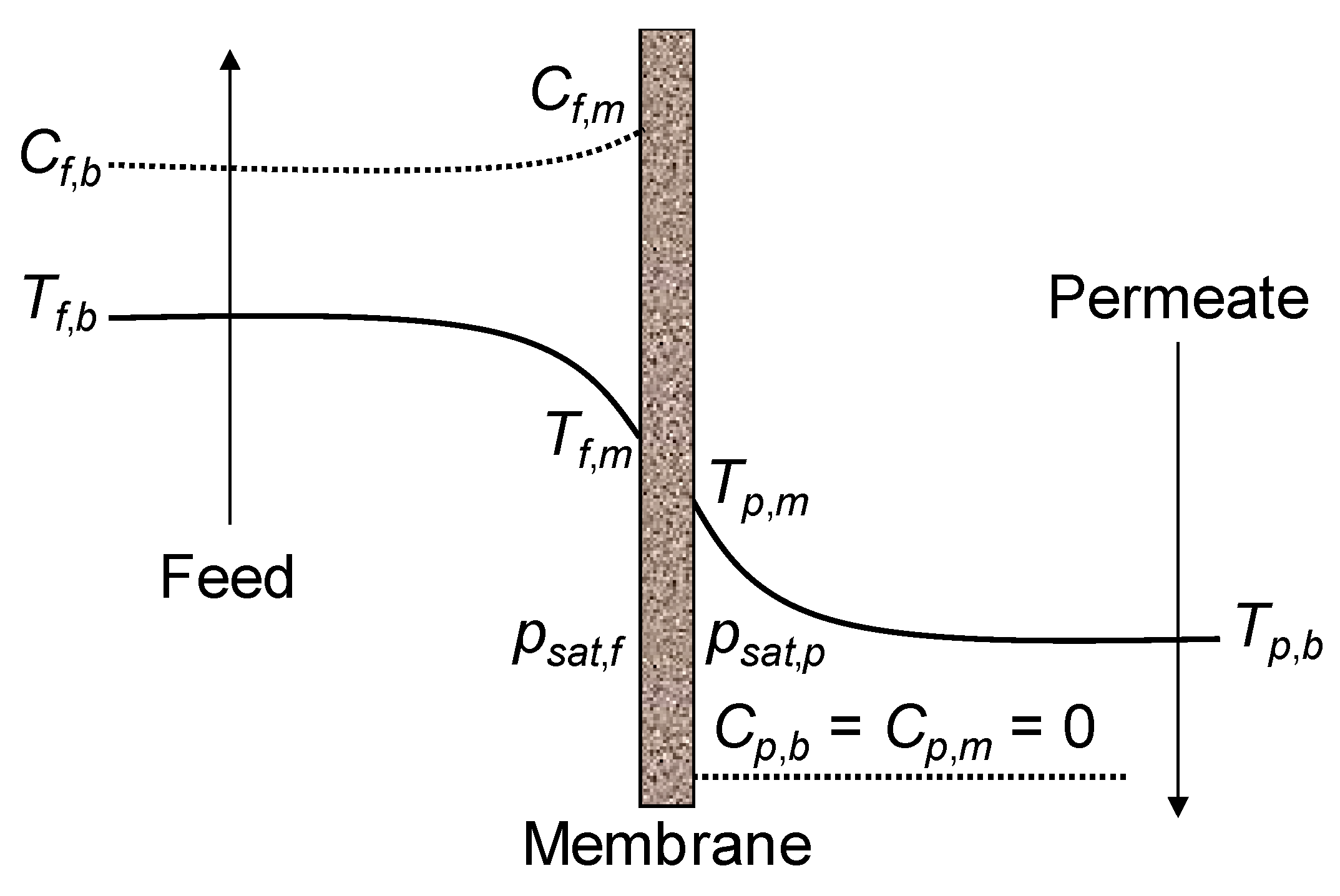

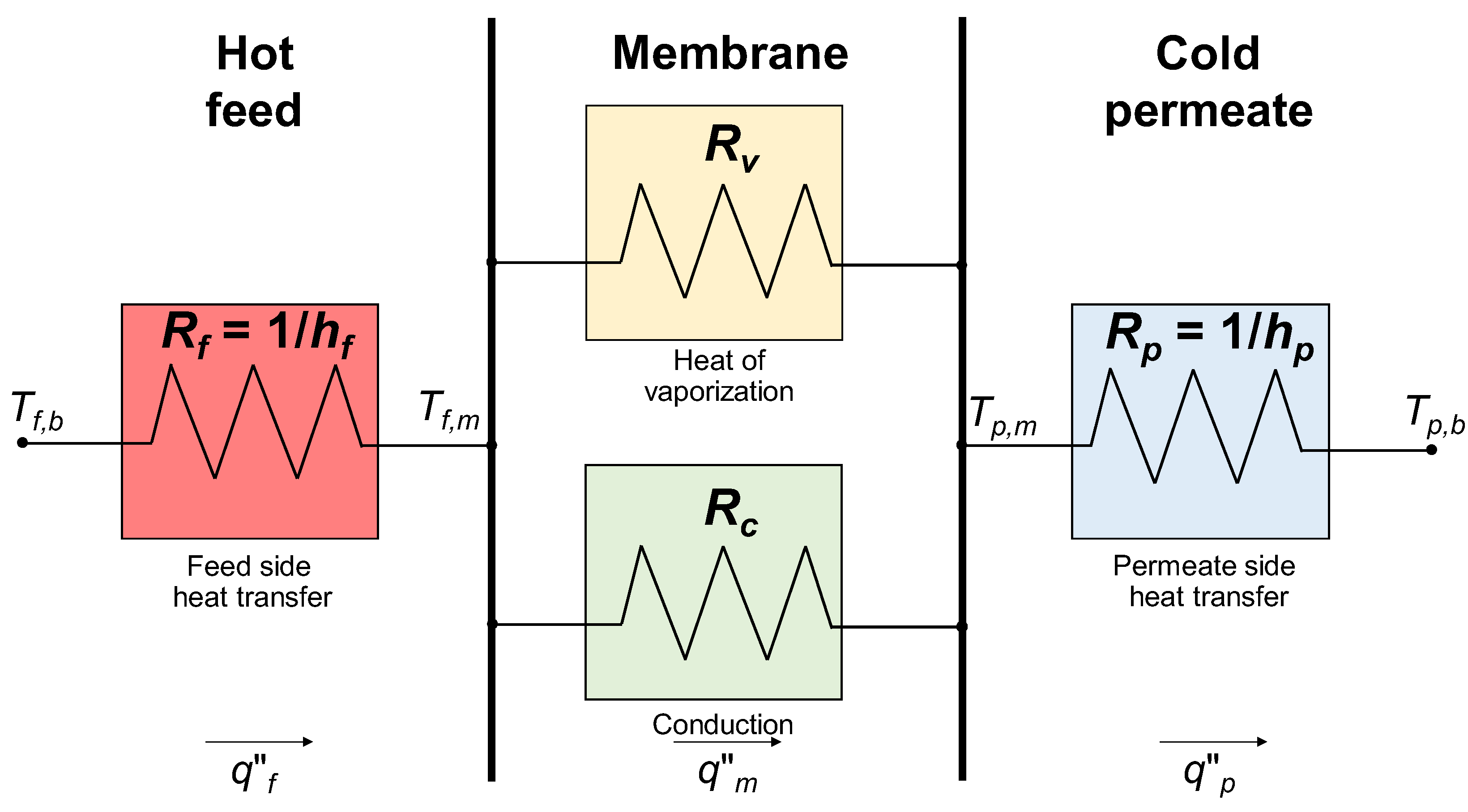

5. Transmembrane Heat Transfer

- (a)

- Heat transfer from the feed bulk to the feed–membrane interface;

- (b)

- Heat transfer from the feed–membrane interface to the membrane–permeate interface;

- (c)

- Heat transfer from the membrane–permeate interface to the permeate bulk.

- -

- Heat flux due to the conduction across the polymeric membrane material and the gas-filled pores, which is denoted here as q″c;

- -

- Heat flux due to the latent heat associated with the water vapor, which is denoted here as q″v.

5.1. Temperature Polarization Phenomena

5.2. Concentration Polarization Phenomena

6. Conclusions

- -

- The membrane pores are filled with a binary mixture of water vapor (moving from feed to permeate) and still, trapped air;

- -

- The mean free path of water (vapor) molecules in the pores can be evaluated by Equation (54);

- -

- The diffusivity of water (vapor) molecules in the pores can be evaluated by Equation (60) (Fuller equation) in the molecular diffusion regime and by Equation (56) in the Knudsen regime. Also, the resulting expressions for the membrane permeance, Equations (57) and (58), are shared by almost all authors (apart from the choice of units and other details);

- -

- The Liquid Entry Pressure (LEP) can be estimated as a function of the surface tension, the pore radius and the solution–membrane contact angle using Equation (50).

- -

- -

- -

- Choosing the temperature at which to evaluate the membrane properties, i.e., the arithmetic mean of Tf,m and Tp,m (most authors) or their geometric mean (Phattaranawik and Jiraratananon [63]);

- -

- Predicting the membrane thermal conductivity as a function of porosity and of the conductivities of the polymeric matrix and the filling gas (Equations (31)–(34));

- -

- Predicting the pore tortuosity as a function of porosity (Equation (48) versus Equation (49)).

- -

- A comparison of the proposed models and correlations for transmembrane transport with both experimental results and ab initio molecular dynamics predictions and other advanced approaches;

- -

- An integration of the above results within more complete and fully predictive computational models accounting for the fluid dynamic aspects of the process. This will also make it possible to conduct sensitivity analyses on the influence of different correlations and model options on practical quantities such as freshwater yield and thermal consumption;

- -

- A combination of heat and mass transfer models with economic and environmental assessment tools to support the scale-up of DCMD at a semi-industrial scale level;

- -

- An exploration of new module designs using computational fluid dynamics, which should be evaluated alongside economic considerations such as manufacturing, operating and maintenance costs;

- -

- The use of 3D-printed or nano-engineered modules could offer unprecedented control over membrane properties and module design, allowing for the creation of complex architectures customized for specific applications.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | Membrane area (m2) |

| A1, B1 | Coefficients in the dynamic viscosity correlation, Equation (11) |

| A2, B2, C2, D2 | Coefficients in the specific heat capacity correlation, Equation (15) |

| aw | Water activity (-) |

| B | Geometric pore coefficient in Equation (50) (-) |

| C | Molar concentration, Equation (4) (mol/m3) |

| Cm | Membrane permeance (kg m−2 h−1 Pa−1 or mol m−2 h−1 Pa−1) |

| cp | Specific heat capacity (J kg−1 K−1) |

| CPC | Concentration polarization coefficient, Equation (74) (-) |

| D | Diffusivity (m2/s) |

| dp | Pore diameter (m) |

| h | Heat transfer coefficient (W m−2 K−1) |

| Hfg | Latent heat of vaporization (J kg−1) |

| ID | Inner fiber diameter of the fiber (m) |

| J | Mass / molar flux (kg m−2 h−1 / mol m−2 h−1) |

| k | Thermal conductivity (W m−1 K−1) |

| KB | Boltzmann’s constant (J K−1) |

| Kn | Knudsen number (-) |

| L | Length of the hollow fiber membrane (m) |

| l | Pore length of the membrane (m) |

| LEP | Liquid Entry Pressure, Equation (50) (Pa) |

| M | Molarity, Equation (3) (mol/L) |

| m | Molality, Equation (2) (mol/kg) |

| MW | Molecular weight (g/mol) |

| OD | Outer fiber diameter of the fiber (m) |

| p | Pressure (Pa) |

| psat | Vapor saturation pressure (Pa or atm) |

| q″ | Heat flux (W/m2) |

| R | Heat transfer resistance (m2 K W−1) |

| Rg | Universal gas constant (J mol−1 K−1) |

| rmax | Largest pore radius (m) |

| S | Salinity (or mass fraction) (kg/kg) |

| SDlog | Standard deviation of lognormal function (-) |

| T | Absolute temperature (K) |

| t | Temperature (°C) |

| TPC | Temperature polarization coefficient, Equation (73) (-) |

| V | Diffusion volume (cm3/mol) |

| w | Membrane mass (kg) |

| x | Molar fraction, Equation (1) (mol/mol) |

| Greek symbols | |

| α, β | Coefficients in Equation (42) |

| Γ | Surface tension (mN/m) |

| γω | Activity coefficient (-) |

| δ | Membrane thickness (m) |

| ε | Porosity of the membrane (-) |

| ζ | Coefficient in Equations (33) and (34) (-) |

| η | Thermal efficiency (-) |

| θ | Contact angle (degree) |

| λ | Mean free path (m) |

| μ | Dynamic viscosity (Pa s) |

| ρ | Density (kg/m3) |

| σ | Collision diameter of the molecule (m) |

| τ | Pore tortuosity of the membrane (-) |

| Subscripts | |

| air | Air |

| aug | Augmented |

| b | Bulk |

| c | Conduction |

| f | Feed |

| g | Gas |

| k | Kerosene |

| m | Membrane |

| max | Maximum |

| p | Permeate |

| pol | Polymeric material |

| s | Salt |

| sat | Saturation |

| sm | Solid matrix |

| v | Vaporization |

| vap | Water vapor |

| w | Water |

| 0 | Referred to pure water |

| 1 | Referred to before the immersion in kerosene |

| 2 | Referred to before the immersion in kerosene |

| Superscripts | |

| C | Referred to the transitional (combined between diffusion and Knudsen) region |

| D | Referred to diffusion region |

| Kn | Referred to Knudsen region |

| Averages | |

| 〈 〉 | Mean value |

Abbreviations

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| CPC | Concentration Polarization Coefficient |

| DCMD | Direct Contact Membrane Distillation |

| LEP | Liquid Entry Pressure |

| MD | Membrane Distillation |

| PES | Polyethersulfone |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PTFE | Polytetrafluoro-ethylene |

| PVDF | Polyvinylidene fluoride |

| TPC | Temperature Polarization Coefficient |

References

- Politano, A.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Alnajdi, S.; Alsaati, A.; Athanassiou, A.; Bar-Sadan, M.; Beni, A.N.; Campi, D.; Cupolillo, A.; D’Olimpio, G.; et al. 2024 Roadmap on Membrane Desalination Technology at the Water-Energy Nexus. J. Phys. Energy 2024, 6, 021502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, J.; Yusuf, A.; Giwa, A.; Sodiq, A. The Global Status of Desalination: An Assessment of Current Desalination Technologies, Plants and Capacity. Desalination 2020, 495, 114633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Porfiri, P.; Ramos-Paredes, S.; Núñez, P.; Gorgojo, P. Towards the Technological Maturity of Membrane Distillation: The MD Module Performance Curve. Npj Clean Water 2023, 6, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.E.; Khalil, A.; Hilal, N. Emerging Desalination Technologies: Current Status, Challenges and Future Trends. Desalination 2021, 517, 115183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassrullah, H.; Anis, S.F.; Hashaikeh, R.; Hilal, N. Energy for Desalination: A State-of-the-Art Review. Desalination 2020, 491, 114569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xian, H. Review of Hybrid Membrane Distillation Systems. Membranes 2024, 14, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahzad, M.W.; Burhan, M.; Ang, L.; Ng, K.C. Energy-Water-Environment Nexus Underpinning Future Desalination Sustainability. Desalination 2017, 413, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhudhiri, A.; Darwish, N.; Hilal, N. Membrane Distillation: A Comprehensive Review. Desalination 2012, 287, 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, L.M.; Dumée, L.; Zhang, J.; de Li, J.; Duke, M.; Gomez, J.; Gray, S. Advances in Membrane Distillation for Water Desalination and Purification Applications. Water 2013, 5, 94–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curcio, E.; Drioli, E. Membrane Distillation and Related Operations-A Review. Sep. Purif. Rev. 2005, 34, 35–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drioli, E.; Ali, A.; Macedonio, F. Membrane Distillation: Recent Developments and Perspectives. Desalination 2015, 356, 56–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, D.; Amigo, J.; Suárez, F. Membrane Distillation: Perspectives for Sustainable and Improved Desalination. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 80, 238–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandro, F.; Macedonio, F. A Critical Review of Membrane Distillation Using Ceramic Membranes: Advances, Opportunities and Challenges. Materials 2025, 18, 3296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, R.V.; Yadav, A.; Shahi, V.K. Advances in Membrane Distillation for Wastewater Treatment: Innovations, Challenges, and Sustainable Opportunities. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 969, 178749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshmukh, A.; Boo, C.; Karanikola, V.; Lin, S.; Straub, A.P.; Tong, T.; Warsinger, D.M.; Elimelech, M. Membrane Distillation at the Water-Energy Nexus: Limits, Opportunities, and Challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwantes, R.; Cipollina, A.; Gross, F.; Koschikowski, J.; Pfeifle, D.; Rolletschek, M.; Subiela, V. Membrane Distillation: Solar and Waste Heat Driven Demonstration Plants for Desalination. Desalination 2013, 323, 93–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurreri, L.; La Cerva, M.; Ciofalo, M.; Cipollina, A.; Tamburini, A.; Micale, G. Application of Computational Fluid Dynamics Technique in Membrane Distillation Processes. In Current Trends and Future Developments on (Bio-) Membranes; Basile, A., Ghasemzadeh, K., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 161–208. [Google Scholar]

- Skuse, C.; Gallego-Schmid, A.; Azapagic, A.; Gorgojo, P. Can Emerging Membrane-Based Desalination Technologies Replace Reverse Osmosis? Desalination 2021, 500, 114844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, A.A.; Kattan Readi, O.M. An Industrial Perspective on Membrane Distillation Processes. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2018, 93, 2047–2055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olatunji, S.O.; Camacho, L.M. Heat and Mass Transport in Modeling Membrane Distillation Configurations: A Review. Front. Energy Res. 2018, 6, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashoor, B.B.; Mansour, S.; Giwa, A.; Dufour, V.; Hasan, S.W. Principles and Applications of Direct Contact Membrane Distillation (DCMD): A Comprehensive Review. Desalination 2016, 398, 222–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pangarkar, B.L.; Deshmukh, S.K.; Sapkal, V.S.; Sapkal, R.S. Review of Membrane Distillation Process for Water Purification. Desalin. Water Treat. 2016, 57, 2959–2981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.M.; Shirazi, M.A.; Nthunya, L.; Castro-Munoz, R.; Ismail, N.; Tavajohi, N.; Zaragoza, G.; Quist-Jensen, C.A. Progress in module design for membrane distillation. Desalination 2024, 581, 117584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anvari, A.; Azimi Yancheshme, A.; Kekre, K.M.; Ronen, A. State-of-the-Art Methods for Overcoming Temperature Polarization in Membrane Distillation Process: A Review. J. Memb. Sci. 2020, 616, 118413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaadi, A.S.; Francis, L.; Amy, G.L.; Ghaffour, N. Experimental and Theoretical Analyses of Temperature Polarization Effect in Vacuum Membrane Distillation. J. Memb. Sci. 2014, 471, 138–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, W.; Chen, H.; Lu, G.; Xu, X.; Cheng, M.; Huang, C.; Guan, X.; An, A.K. In-Situ Temperature Measurement and Non-Linear Interaction Analysis of Temperature Polarization in Direct Contact Membrane Distillation. J. Memb. Sci. 2025, 735, 124508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Díez, L.; Vázquez-González, M. Temperature and Concentration Polarization in Membrane Distillation of Aqueous Salt Solutions. J. Memb. Sci. 1999, 156, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayet, M.; Matsuura, T. Membrane Distillation-Principles and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, R.W.; Fane, A.G.; Fell, C.J.D.; Macoun, R. Factors Affecting Flux in Membrane Distillation. Desalination 1990, 77, 279–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Díez, L.; Vázquez-González, M. Effects of Polarization on Mass Transport through Hydrophobic Porous Membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 1998, 37, 4128–4135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayet, M.; Godino, M.P.; Mengual, J.I. Study of Asymmetric Polarization in Direct Contact Membrane Distillation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2004, 39, 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitsov, I.; Maere, T.; de Sitter, K.; Dotremont, C.; Nopens, I. Modelling Approaches in Membrane Distillation: A Critical Review. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2015, 142, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharqawy, M.H.; Lienhard, J.H.V.; Zubairb, S.M. Thermophysical properties of seawater: A review of existing correlations and data. Desal. Water Treat. 2010, 16, 354–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dessouky, H.T.; Ettouney, H.M. Fundamentals of Salt Water Desalination; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isdale, J.D.; Spence, C.M.; Tudhope, J.S. Physical properties of sea water solutions: Viscosity. Desalination 1972, 10, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korosi, A.; Fabuss, B.M. Viscosity of liquid water from 25 °C to 150 °C. J. Anal. Chem. 1968, 40, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D.T.; Tudhope, J.S.; Morris, R.; Cartwright, G. Physical properties of sea water solutions: Heat capacity. Desalination 1969, 7, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, D.T.; Tudhope, J.S. Physical properties of sea water solutions–Thermal Conductivity. Desalination 1970, 8, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, A.; Singh, C.P.; Patel, R.V.; Kumar, A.; Labhasetwar, P.K. Investigations on the effect of spacer in direct contact and air gap membrane distillation using computational fluid dynamics. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 654, 130111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalifa, A.; Ahmad, H.; Antar, M.; Laoui, T.; Khayet, M. Experimental and theoretical investigations on water desalination using direct contact membrane distillation. Desalination 2017, 404, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momeni, M.; Kargari, A.; Dadvar, M.; Jafari, A. 3D-CFD simulation of hollow fiber direct contact membrane distillation module: Effect of module and fibers geometries on hydrodynamics, mass, and heat transfer. Desalination 2024, 576, 117321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, A.; Galogahi, F.M.; Millar, G.; Helfer, F.; Thiel, D.V.; Soukane, S.; Ghaffour, N. Computational fluid dynamics simulations of solar-assisted, spacer-filled direct contact membrane distillation: Seeking performance improvement. Desalination 2023, 545, 116181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Li, B.; Sirkar, K.K.; Gilron, J.L. Direct Contact Membrane Distillation-Based Desalination: Novel Membranes, Devices, Larger-Scale Studies, and a Model. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2007, 46, 2307–2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouguecha, S.T.; Aly, S.E.; Al-Beirutty, M.H.; Hamdi, M.M.; Boubakri, A. Solar driven DCMD: Performance evaluation and thermal energy efficiency. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2015, 100, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eykens, L.; Hitsov, I.; De Sitter, K.; Dotremont, C.; Pinoy, L.; Nopens, I.; Van der Bruggen, B. Influence of membrane thickness and process conditions on direct contact membrane distillation at different salinities. J. Membr. Sci. 2016, 498, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, Z.; Long, R.; Liu, Z.; Liu, W. Analysis of temperature and concentration polarizations for performance improvement in direct contact membrane distillation. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2019, 145, 118724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Zhang, H. An efficient and economic evacuated U-tube solar collector powered air gap membrane distillation hybrid system for seawater desalination. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 394, 136382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kariman, H.; Mohammed, H.A.; Zargar, M.; Khiadani, M. Performance comparison of flat sheet and hollow fibre air gap membrane distillation: A mathematical and simulation modelling approach. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 721, 123836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASHRAE. Thermophysical Properties of Refrigerants. In 2017 ASHRAE Handbook: Fundamentals; ASHRAE: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Jia, Z.; Li, R.; Gu, Z. Analysis and Experimental Study on Water Vapor Partial Pressure in the Membrane Distillation Process. Membranes 2022, 12, 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.; Ho, C.-D.; Chen, Y.-H.; Chen, L.; Hsu, T.-H.; Lim, J.-W.; Chiou, C.-P.; Lin, P.-H. Enhancing the Permeate Flux of Direct Contact Membrane Distillation Modules with Inserting 3D Printing Turbulence Promoters. Membranes 2021, 11, 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, L.A.; Singh, D.; Ray, P.; Sridhar, S.; Read, S.M. Thermodynamic Properties of Sea Salt Solutions. AIChE J. 1974, 20, 326–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Dow, N.; Duke, M.; Ostarcevic, E.; Jun-De, L.; Gray, S. Identification of material and physical features of membrane distillation membranes for high performance desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 349, 295–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, R.W.; Fane, A.G.; Fell, C.J.D. Heat and mass transfer in membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 1987, 33, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phattaranawik, J.; Jiraratananon, R.; Fane, A.G. Effect of pore size distribution and air flux on mass transport in direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2003, 215, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcıa-Payo, M.C.; Izquierdo-Gil, M.A. Thermal resistance technique for measuring the thermal conductivity of thin microporous membranes. J.Phys. D 2004, 37, 3008–3016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, K.; Laesecke, A. The Thermal Conductivity of Fluid Air. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 1985, 14, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology. NIST Chemistry WebBook, SRD69. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/fluid/ (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Udoetok, E.S. Thermal Conductivity of binary mixtures of gases. Front. Heat Mass Transf. 2013, 4, 023008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Bourawi, M.S.; Ding, Z.; Ma, R.; Khayet, M. A framework for better understanding membrane distillation separation process. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 285, 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, K.W.; Lloyd, D.R. Membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 1997, 124, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Nuaimi, R.; Thankamony, R.L.; Boross de Levay, J.-P.B.; Yuan, B.; Lai, Z. Uniformly porous PVDF-co-HFP membranes prepared by mixed solvent phase separation for direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2024, 711, 123175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phattaranawik, J.; Jiraratananon, R. Direct contact membrane distillation: Effect of mass transfer on heat transfer. J. Membr. Sci. 2001, 188, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, S.; Nguyen, D.T.; Martinez, J.; Chau, J.; Fung, K.; Sirkar, K.; Straub, A.P.; Ding, Y. The effect of Sharklet patterns on thermal efficiency and salt-scaling resistance of poly (vinylidene fluoride) membranes during direct contact membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 715, 123476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y.; Dai, X.; Zhao, L.; Gao, L.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, J. Review of Transport Phenomena and Popular Modelling Approaches in Membrane Distillation. Membranes 2021, 11, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayet, M.; Velázquez, A.; Mengual, J.I. Modelling mass transport through a porous partition: Effect of pore size distribution. J. Non-Equilib. Thermodyn. 2004, 29, 279–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, J.; Pellegrino, J.; Burch, J. Generalized guidance for considering pore-size distribution in membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 368, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolder, K.; Franken, A.D.M. Terminology for Membrane Distillation. Desalination 1989, 72, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayet, M.; Matsuura, T. Preparation and characterization of polyvinylidene fluoride membranes for membrane distillation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2001, 40, 5710–5718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Zhang, X.; Gusnawan, P.; Zhang, G.; Yu, J. Crosslinked PVDF based hydrophilic-hydrophobic dual-layer hollow fiber membranes for direct contact membrane distillation desalination: From the seawater to oilfield produced water. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 619, 118802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Field, R.W.; Wu, H.Y.; Wu, J.J. Multi-scale modelling of membrane distillation: Some theoretical considerations. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013, 52, 8822–8828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasuda, H.; Tsai, J.T. Pore size of microporous polymer membranes. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 1974, 18, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srisurichan, S.; Jiraratananon, R.; Fane, A.G. Mass transfer mechanisms and transport resistances in direct contact membrane distillation process. J. Membr. Sci. 2006, 277, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackie, J.S.; Meares, E. The Diffusion of Electrolytes in a Cation-Exchange Resin Membrane. I. Theoretical. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A Math. Phys. Sci. 1955, 232, 498–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciofalo, M.; Lombardo, S.; Pettinato, D.; Quattrocchi, D. Experimental investigation of two-side heat transfer in spacer-filled channels representative of Membrane Distillation. Exp. Therm. Fluid Sci. 2023, 140, 110770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, A.C.M.; Nolten, J.A.M.; Mulder, M.H.V.; Bargeman, D.; Smolders, C.A. Wetting criteria for the applicability of membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 1987, 33, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, K.P.; Wang, R.; Hjelvik, E.A.; Lin, S.; Straub, A.P. Toward a universal framework for evaluating transport resistances and driving forces in membrane-based desalination processes. Sci. Adv. 2023, 9, eade0413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomaszewska, M. Preparation and properties of flat-sheet membranes from poly(vinylidene fluoride) for membrane distillation. Desalination 1996, 104, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sghaier, N.; Prat, M.; Ben Nasrallah, S. On the influence of sodium chloride concentration on equilibrium contact angle. Chem. Eng. J. 2006, 122, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rácz, G.; Kerker, S.; Kovács, Z.; Vatai, G.; Ebrahimi, M.; Czermak, P. Theoretical and Experimental Approaches of Liquid Entry Pressure Determination in Membrane Distillation Processes. Period. Polytech. Chem. Eng. 2014, 58, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cussler, E. Diffusion Mass Transfer in Fluid Systems, 3rd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, A.F. Mass Transfer, 2nd ed.; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Ghaleni, M.M.; Bavarian, M.; Nejati, S. Model-guided design of high-performance membrane distillation modules for water desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 563, 794–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geankoplis, C.J. Transport Processes and Separation Process Principles (Includes Unit Operations), 4th ed.; Prentice Hall Press: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Poling, B.E.; Prausnitz, J.M.; O’Connell, J.P. The Properties of Gases and Liquids, 5th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bosanquet, C.H. British TA Report BR-507; London, UK, 1944. [Google Scholar]

- Pollard, W.G.; Present, R.D. On gaseous self-diffusion in long capillary tubes. Phys. Rev. 1948, 73, 762–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishna, E.; van Baten, J.M. Investigating the validity of the Bosanquet formula for estimation of diffusivities in mesopores. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2012, 69, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, J.-H.; Quist-Jensen, C.; Ali, A. Multipass hollow fiber membrane modules for membrane distillation. Desalination 2023, 548, 116239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schofield, R.W.; Fane, A.G.; Fell, C.J.D. Gas and vapour transport through microporous membranes. II. Membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 1990, 53, 173–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Ma, Z.; Liao, X.; Kosaraju, P.B.; Irish, J.R.; Sirkar, K.K. Pilot plant studies of novel membranes and devices for direct contact membrane distillation-based desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 323, 257–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Li, L.; Obusckovic, G.; Chau, J.; Sirkar, K.K. Novel cylindrical cross-flow hollow fiber membrane module for direct contact membrane distillation-based desalination. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 545, 312–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancilla, N.; Bounou, A.; Ciofalo, M.; Tamburini, A.; Micale, G. CFD prediction of flow and heat transfer in hollow fiber bundles for Membrane Distillation: A comparison of regular and random arrangements. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2026, 254, 127672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, C.-D.; Chen, L.; Lim, J.-W.; Lin, P.-H.; Lu, P.-T. Distillate Flux Enhancement of Direct Contact Membrane Distillation Modules with Inserting Cross-Diagonal Carbon-Fiber Spacers. Membranes 2021, 11, 973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schock, G.; Miquel, A. Mass transfer and pressure loss in spiral wound modules. Desalination 1987, 64, 339–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picioreanu, C.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Three-dimensional modeling of biofouling and fluid dynamics in feed spacer channels of membrane devices. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 345, 340–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koutsou, C.P.; Yiantsios, S.G.; Karabelas, A.J. A numerical and experimental study of mass transfer in spacer-filled channels: Effects of spacer geometrical characteristics and Schmidt number. J. Membr. Sci. 2009, 326, 234–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburini, A.; Renda, M.; Cipollina, A.; Micale, G.; Ciofalo, M. Investigation of heat transfer in spacer-filled channels by experiments and direct numerical simulations. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2016, 93, 1190–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ponzio, F.N.; Tamburini, A.; Cipollina, A.; Micale, G.; Ciofalo, M. Experimental and computational investigation of heat transfer in channels filled by woven spacers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2017, 104, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.K.; Liang, Y.Y.; Lau, W.J.; Fimbres Weihs, G.A. 3D CFD study of hydrodynamics and mass transfer phenomena for spiral wound membrane submerged-type feed spacer with different node geometries and sizes. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2022, 191, 122819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliakellis, P.; Koutsou, C.; Karabelas, A. The effect of gap reduction on fluid dynamics and mass transfer in membrane narrow channels filled with novel spacers-a detailed computational study. Membranes 2023, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciofalo, M.; Cancilla, N.; Cipollina, A.; Tamburini, A.; Micale, G. Influence of thermal buoyancy on heat transfer in spacer-filled channels for membrane distillation. J. Phys.–Conf. Ser. 2025, 2940, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cancilla, N.; Tamburini, A.; Tarantino, A.; Visconti, S.; Ciofalo, M. Friction and heat transfer in membrane distillation channels: An experimental study on conventional and novel spacers. Membranes 2022, 12, 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qamar, A.; Kerdi, S.; Ali, S.M.; Shon, H.K.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Ghaffour, N. Novel hole-pillar spacer design for improved hydrodynamics and biofouling mitigation in membrane filtration. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Chen, D.; Wu, J.J.; Wang, B.; Field, R.W. Arch-type feed spacer with wide passage node design for spiral-wound membrane filtration with reduced energy cost. Desalination 2022, 540, 115980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamar, A.; Kerdi, S.; Vrouwenvelder, J.S.; Ghaffour, N. Airfoil-shaped filament feed spacer for improved filtration performance in water treatment. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, Y.K.; Liang, Y.Y.; Fimbres Weihs, G.A. Validation and characterisation of mass transfer of 3D-CFD model for twisted feed spacer. Desalination 2023, 554, 116516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.E.; Jung, S.Y.; Kang, T.G. Robust design of a stacked-filament feed spacer inducing chaotic advection for enhanced reverse osmosis filtration. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 734, 124431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schilling, S.; Glade, H. Review and Analysis of Heat Transfer in Spacer-Filled Channels of Membrane Distillation Systems. Membranes 2023, 13, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabrizi, A.B.; Wu, B. Review of computational fluid dynamics simulation techniques for direct contact membrane distillation systems containing filament spacers. Desalin. Water Treat. 2019, 162, 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Polymeric Material | Constants | ksm

at 20 °C (W m−1 K−1) | ksm

at 40 °C (W m−1 K−1 | ksm

at 60 °C (W m−1 K−1) | ksm

at 80 °C (W m−1 K−1) | ksm

at 100 °C (W m−1 K−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polypropylene (PP) | α = 12.5 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.23 |

| β = −23.5 | ||||||

| Polyethersulfone (PES) | α = 4.17 | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.16 | 0.17 |

| β = 1.45 | ||||||

| Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) | α = 5.77 | 0.18 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 0.21 | 0.22 |

| β = 0.914 | ||||||

| Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) | α = 5.77 | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.29 | 0.30 |

| β = 8.914 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Cancilla, N.; Cipollina, A.; Gurreri, L.; Ciofalo, M. Direct Contact Membrane Distillation: A Critical Review of Transmembrane Heat and Mass Transfer Models. Membranes 2026, 16, 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020064

Cancilla N, Cipollina A, Gurreri L, Ciofalo M. Direct Contact Membrane Distillation: A Critical Review of Transmembrane Heat and Mass Transfer Models. Membranes. 2026; 16(2):64. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020064

Chicago/Turabian StyleCancilla, Nunzio, Andrea Cipollina, Luigi Gurreri, and Michele Ciofalo. 2026. "Direct Contact Membrane Distillation: A Critical Review of Transmembrane Heat and Mass Transfer Models" Membranes 16, no. 2: 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020064

APA StyleCancilla, N., Cipollina, A., Gurreri, L., & Ciofalo, M. (2026). Direct Contact Membrane Distillation: A Critical Review of Transmembrane Heat and Mass Transfer Models. Membranes, 16(2), 64. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes16020064