Abstract

Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is commonly used in gas-separation studies because of its high CO2 permeability and stable mechanical properties. In this work, mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) were prepared by incorporating the bimetallic MOFs Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 into a PDMS matrix. The membranes were fabricated by solution casting and characterized by SEM, XRD, FT-IR, and BET analyses, which confirmed uniform filler dispersion and the successful incorporation of the MOF-74 structures. Single-gas permeation tests showed clear performance improvements with MOF loading. The best results were obtained for the membrane containing 1 wt.% Ni-Cu-MOF-74, which reached a CO2 permeability of 3188.25 Barrer and a CO2/N2 selectivity of 35.10. The improvement is attributed to the accessible metal sites and high surface area provided by the MOF-74 framework, which enhanced adsorption–diffusion pathways for CO2 transport. These results show that PDMS/MOF-74 mixed-matrix membranes are effective for CO2/N2 separation, with Ni-Cu-MOF-74 achieving the highest performance.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of industrial activity and global economic development has caused a continuous rise in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, with direct consequences for the climate and for public health. In the early stages of industrialization, most emissions originated from developed countries, but in recent decades, contributions from developing nations have increased sharply. This shift has made international coordination necessary rather than relying on a small group of emitters. An important step in this direction was the Kyoto Protocol, adopted in 1997, which established a framework for limiting greenhouse gas emissions globally [1]. CO2 is of particular concern because it enhances the greenhouse effect and contributes directly to atmospheric warming [2]. Among the main greenhouse gases, it stands out for its large emissions and long atmospheric residence time, both of which intensify its environmental and health impacts [3,4]. The combustion of fossil fuels remains the dominant source of anthropogenic CO2. Typical flue gas from fossil-fuel-based power plants and industrial processes contains about 12–15% CO2 and 70–75% N2, along with smaller amounts of other gases [5]. Due to these high emissions levels, effective carbon capture technologies are required to mitigate climate-related risks and reduce environmental burden. In parallel, CO2 is increasingly recognized as a valuable carbon source for large-scale chemical production, providing additional incentive to design efficient capture and utilization processes [6]. At present, carbon capture and sequestration is mainly carried out through four technological routes: adsorption, absorption, cryogenic distillation, and membrane-based gas separation, each with its own operating window and separation limitations [7].

Among these, membrane-based gas separation has emerged as a practical option for large-scale CO2 capture because it typically requires lower operating costs and less energy and can be integrated with relatively simple process equipment [8,9]. These features make it particularly suitable for industrial use. A wide range of membrane materials has been investigated for gas separation and can be broadly classified as organic or inorganic. Organic membranes are usually dense, non-porous polymeric materials [10], whereas inorganic membranes are based on ceramic and metallic systems, including amorphous silica, zeolites, and palladium alloys [11].

Most membrane materials still present important limitations. Ceramic membranes, for example, tend to develop cracks during fabrication, which reduces their separation performance [12], and their large-scale manufacture remains expensive [13]. Metallic membranes also pose difficulties, including embrittlement, high operating costs, and limited service lifetimes [14]. In contrast, polymeric membranes are widely used because they are easier to fabricate and operate and can offer good selectivity [15,16,17]. However, their relatively low gas permeability results in the well-known permeability–selectivity trade-off described by Robeson’s upper bound [18,19]. Overcoming this trade-off is essential for the development of high-performance membrane systems [20]. One strategy to address this issue is the design of hybrid polymer–inorganic systems, or mixed matrix membranes (MMMs), in which inorganic fillers are dispersed within dense polymer matrices [21,22]. MMMs combine the good processability of polymers with the thermal and chemical stability of inorganic phases. Their enhanced CO2 separation performance is largely due to the intrinsic high gas separation capabilities of the inorganic components [23]. Among these, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have become especially attractive as fillers for MMM fabrication because they typically offer good compatibility with polymer matrices, very high surface area and porosity, and a strong affinity for CO2 [24,25,26,27,28,29]. Recent work using MOFs as fillers in MMMs has reported significant improvements in CO2 separation performance. For instance, M.A. Rodrigues et al. [30] incorporated MIL-101(Cr) into a polyurethane matrix and obtained a CO2/N2 selectivity of 42.4 with a CO2 permeability of 83.1 Barrer. In another study, Q. Zhang et al. [31] prepared triptycene-functionalized polyimide MMMs containing ZIF-90, achieving a CO2/N2 selectivity of 26.18 and a CO2 permeability of 12.75 Barrer, surpassing the 2008 Robeson upper bound. More recent work has aimed to alleviate the permeability–selectivity trade-off by creating MOF-based transport pathways within polymer matrices. For example, the use of amino-modified UiO-66 in a polysulfone matrix resulted in high CO2 permeability and reasonably high CO2/N2 selectivity [32]. Likewise, surface-modified UiO-66 incorporated into a Matrimid matrix enhanced permeation properties and produced a modest improvement in CO2/N2 selectivity [33]. Coating strategies have also been used to improve MOF-based MMMs. For example, MIL-101(Cr) particles coated with polyethyleneimine and dispersed in a sulfonated poly (ether ether ketone) matrix produced membranes whose performance exceeded the 2008 Robeson upper bound [34]. To further enhance the separation properties of MOF-filled MMMs, bimetallic MOFs have been investigated. M. Loloei et al. [35] incorporated a bimetallic Zn-Co ZIF (ZIF-8-67) into a 6FDA-ODA polyimide matrix and reported a maximum CO2/CH4 selectivity of 45.1 and a CO2 permeability of 44.2 Barrer. Compared with MMMs containing monometallic ZIF-8 or ZIF-67, the bimetallic filler provided higher selectivity and permeability. In a related study, X. Du et al. [36] synthesized a bimetallic UiO-66 based on Ce and Zr, applied amine functionalization, and incorporated it into a PEBAX matrix. The resulting MMMs showed a CO2/N2 selectivity of 76.4 and a CO2 permeability of 100.7 Barrer at a low loading of 3 wt.%, together with good pressure resistance, indicating their potential for industrial operation.

Recent work on bimetallic MOFs incorporated into polymer matrices has reported improved gas-separation performance. In this study, three bimetallic MOF-74 materials—Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74—are incorporated into a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) matrix to prepare mixed matrix membranes (MMMs). Their CO2/N2 separation performance is examined through single-gas permeation tests. Structural and morphological features of the membranes are analyzed using SEM, XRD, and FT-IR.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials Used

The following materials were used for the synthesis of mixed matrix membranes (MMMs):

- Polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS, CAS No. 63148-62-9) obtained from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA;

- Toluene (CAS No. 208-88-3, Mw = 92.14 g mol−1, ACS reagent grade, 99.7% purity) purchased from Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA;

- Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 fillers obtained from another Research group within the institute;

- High-purity CO2 (99.999 vol%) and N2 (99.999 vol%) gases purchased from Paradise Gases, Islamabad, Pakistan.

All chemicals, solvents, and reagents were used as received without additional purification.

2.2. Synthesis of Metal–Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

Ni-M-MOF-74 (M = Cu, Co, Zn) fillers were prepared by a solvothermal route, following the method of Asad et al. [37], with minor adjustments to the metal composition. In a typical synthesis, 1 mmol of 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalic acid (H4DOBDC) was dissolved in a mixed solvent of DMF, ethanol, and deionized water (1:1:1, v/v/v). In separate solutions, Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (99 mol%) and a secondary metal nitrate—Cu(NO3)2·6H2O (2 mol%), Co(NO3)2·6H2O (1 mol%), or Zn(NO3)2·6H2O (1 mol%)—were dissolved in water and then combined with the ligand solution under stirring. The resulting mixtures were placed in Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclaves and heated at 120 °C for 12 h. After cooling to room temperature, the solids were collected by centrifugation, washed several times with ethanol and deionized water, and finally dried under vacuum at 60 °C for 24 h to yield Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 powders.

2.3. Synthesis of Mixed Matrix Membranes (MMMs)

The PDMS-based mixed matrix membranes were prepared as follows. First, 4 g of PDMS elastomer (40% w/v) was dissolved in 10 mL of toluene, and the mixture was stirred magnetically at 300 rpm for 2 h. In parallel, bimetallic MOF particles were dispersed in toluene at a filler loading of 1 wt.% and treated by magnetic stirring, followed by bath sonication, to improve dispersion. The MOF dispersion was then added to the PDMS solution, and the mixture was sonicated for an additional 1 h. To eliminate trapped air, the resulting polymer–filler suspension was degassed under ultrasonic irradiation for 30 min. Finally, the mixture was cast into a Petri dish and dried in an oven at 80 °C for 2–3 h to obtain a dense membrane with a thickness in the range of 170–180 µm. The synthesis procedure is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Synthesis procedure for Ni-Cu-MOF-74/PDMS, Ni-Co-MOF-74/PDMS, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74/PDMS MMMs.

3. Testing and Characterization

3.1. Fourier Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

FT-IR spectroscopy was used to examine the chemical structure of mixed-matrix membranes (MMMs) containing bimetallic MOFs dispersed in a polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) matrix. For comparison, FT-IR spectra of the corresponding bimetallic MOF powders were also recorded. Measurements were carried out on a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 FT-IR spectrometer over the wavenumber range 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1.

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy

SEM imaging was carried out using a JEOL JSM-6490LA (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) analytical low-vacuum instrument. For the membranes, both the surface and cross-section were examined. Cross-sectional images were recorded at magnifications between 250× and 5000×, and surface images between 500× and 10,000×. For the MOF particles, only surface morphology was analyzed at magnifications ranging from 250× to 10,000×. These measurements were used to assess the morphology and internal structure of the MMMs and the MOF fillers.

3.3. X-Ray Diffraction

XRD measurements were used to examine the crystallographic structure of the MOF filler particles and the PDMS-based MMMs, and to assess how incorporation into the polymer matrix affected MOF crystallinity. The patterns were recorded on a Bruker D2 (Bruker AXS GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany) Phaser diffractometer equipped with a copper sample holder, using Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5406 Å) at 30 kV and 10 mA.

3.4. Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET)

The specific surface area and porosity of the membranes were obtained from nitrogen adsorption isotherms using the BET method on an ASAP 2460 Surface area and Porosimetry Analyzer (Micromeritics Instrument Corporation, Norcross, GA, USA). These measurements provide quantitative information on the accessible surface and pore structure, parameters that directly influence gas uptake and diffusion and are therefore important for interpreting the membranes’ separation performance.

3.5. Gas Permeation

Gas permeation experiments aim to provide a method for calculating selectivity and permeability, as these factors significantly influence the performance of a given membrane [38]. The gas flow rate, membrane area, membrane thickness, and pressure differential across the membrane may all be used to calculate a gas’s permeability. It is depicted in mathematical form in Equation (1) as shown [39]:

PA = (Q × ∆l)/(A × ∆P)

Here, PA is the gas A permeability through the membrane (expressed in cm3-cm/s-cm2-cm Hg), Q is the flow rate (volumetric) of the gas (expressed in cm3/s), Δl is the thickness of the membrane (expressed in cm), and ΔP is the pressure difference.

Selectivity, defined as the ratio of permeabilities of two gases, is represented mathematically in Equation (2) [40]:

where αA/B is the selectivity of gas A over gas B.

αA/B = PA/PB

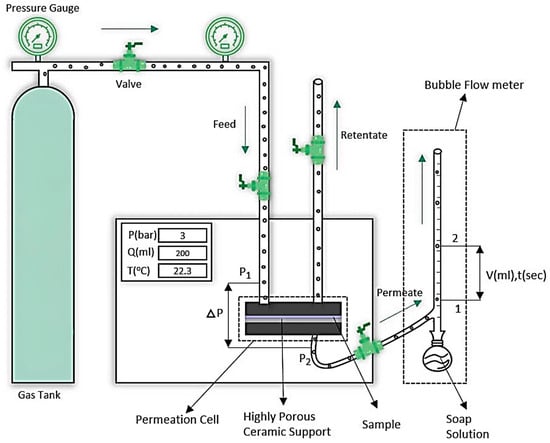

Single gas permeation testing was conducted using a standard Gas Permeability Test System from PHILOS, (Gwangmyeong-si, South Korea). The system features a circular stainless steel permeation rig with an active surface area of 8 cm2. The test membrane sample was secured between two porous ceramic plates, and rubber O-rings prevented leakage. Carbon dioxide and nitrogen gases were used as test gases, and experiments were performed at pressures ranging from 2 to 5 bars, with readings taken at 1-bar increments. The gas permeation rate was measured using a bubble flow meter connected to the permeate side of the system. All tests were conducted at room temperature (25 °C; 298 K), and each membrane was tested three times under identical conditions to verify reproducibility. These parameters were used to calculate the permeability of CO2 and N2 gases using Equation (1). Permeation testing was also conducted for PDMS-based MMMs containing 1 wt.% Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 particles. The experimental setup is schematically represented in Figure 2 [41].

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the gas permeability test system [41].

4. Analysis

4.1. Fourier Transform Infra-Red (FT-IR) Spectroscopic Analysis

Three types of MOF particles—Ni-Co-MOF-74, Ni-Zn-MOF-74, and Ni-Cu-MOF-74—were examined, together with the corresponding MMMs containing 1 wt.% of each filler. The FT-IR spectra of the MOFs and MMMs are shown in Figure 3. The MOF powders displayed the expected characteristic absorption bands associated with their framework functional groups. Similar bands were observed in the spectra of the MMMs, confirming that the MOF particles were successfully incorporated into the PDMS matrix. The preservation of these bands in the MMMs indicates that the MOF structures remained chemically intact during membrane fabrication. Overall, the FT-IR results clarify the chemical composition of the MMMs and support the interpretation of their behaviour in subsequent gas separation measurements.

Figure 3.

(a) FT-IR spectrum for Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74; (b) FT-IR spectra for MOF-based MMMs for all MOF samples.

4.1.1. Analysis of MOF Particles

Figure 3a represents the FT-IR spectra of the three MOF samples:

Ni-Cu MOF-74:

Symmetric and asymmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxylate (–COO−) groups are observed at 1630.47 cm−1 and 1410.12 cm−1, respectively. Bands at 1126.05 cm−1 and 817.74 cm−1 are assigned to C-H bending vibrations. A strong band at 734.72 cm−1 corresponds to Ni-O stretching, while the peak at 525.58 cm−1 is attributed to Cu-O stretching vibrations.

Ni-Co-MOF-74:

The FT-IR spectrum of Ni-Co-MOF-74 shows bands similar to those of Ni-Cu-MOF-74, with slight shifts, indicating a comparable chemical structure. The bands at 1576.67 cm−1 and 1389.06 cm−1 are assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxylate groups, respectively. Peaks at 1148.19 cm−1 and 826.48 cm−1 correspond to C-H bending vibrations. The band at 741.24 cm−1 is attributed to Ni-O stretching, while the peak at 560.79 cm−1 is assigned to Co-O stretching vibrations.

Ni-Zn-MOF-74:

Bands at 1582.06 cm−1 and 1371.67 cm−1 are assigned to the asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations of the carboxylate groups, respectively. Peaks at 1145.05 cm−1 and 819.59 cm−1 correspond to C-H bending vibrations. The band at 749.27 cm−1 is attributed to Ni-O stretching, while the peak at 478.83 cm−1 arises from Zn-O stretching and is consistent with a highly crystalline framework. Overall, the FT-IR spectra confirm the presence of 2,5-dihydroxyterephthalate (DOBDC) linkers and metal–oxygen bonds in the MOF structures, indicating successful synthesis and good crystallinity.

4.1.2. Analysis of MOF-Based MMMs

Figure 3b shows the FT-IR spectra of the MMMs containing Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74. The spectra include the characteristic bands of the MOFs together with additional signals from the PDMS matrix. Peaks at around 1600 cm−1, 1400 cm−1, 700 cm−1, and 500 cm−1 coincide with those observed for the corresponding MOF powders (Figure 3a). These peaks are assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric stretching of the carboxylate groups, C-H bending, and metal–oxygen (Ni-O, Cu-O, Co-O, Zn-O) stretching vibrations.

In addition, intense bands at 805 cm−1, 1024 cm−1, and 1258 cm−1 correspond to Si-C-H, Si-O-Si, and Si-C vibrations of the PDMS phase, respectively. A weak band near 2960 cm−1 is attributed to sp3 C-H stretching. The simultaneous presence of MOF-related and PDMS-related bands confirms that Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 were successfully incorporated into the PDMS matrix and that the hybrid MMMs were properly formed.

4.2. SEM Analysis

SEM analysis was used to examine the morphology of Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 particles and of the corresponding MMMs containing 1 wt.% of each filler in the PDMS matrix. Representative micrographs are shown in Figure 4. The images of the MOF powders (Figure 4a–c) indicate uniform particle morphology, in good agreement with previous reports [42,43]. The surface SEM images of the MMMs (Figure 4d–f) show dense, continuous membranes without visible cracks or voids. The MOF particles appear well dispersed within the PDMS phase, with no obvious agglomeration, suggesting good compatibility and adhesion between the fillers and the polymer [44]. This uniform dispersion is important for preserving both selectivity and permeability in gas separation [45]. Cross-sectional images (Figure 4g–i) reveal compact membrane structures with an even distribution of MOF particles across the membrane thickness and no evidence of interfacial voids or phase separation. These observations further support the presence of strong interfacial bonding between the MOF fillers and the PDMS matrix.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of (a) Ni-Cu-MOF-74, (b) Ni-Co-MOF-74, and (c) Ni-Zn-MOF-74; surface morphology of MMMs based on (d) Ni-Cu-MOF-74, (e) Ni-Co-MOF-74, and (f) Ni-Zn-MOF-74; and cross-sectional morphology of MMMs based on (g) Ni-Cu-MOF-74, (h) Ni-Co-MOF-74, and (i) Ni-Zn-MOF-74.

4.3. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

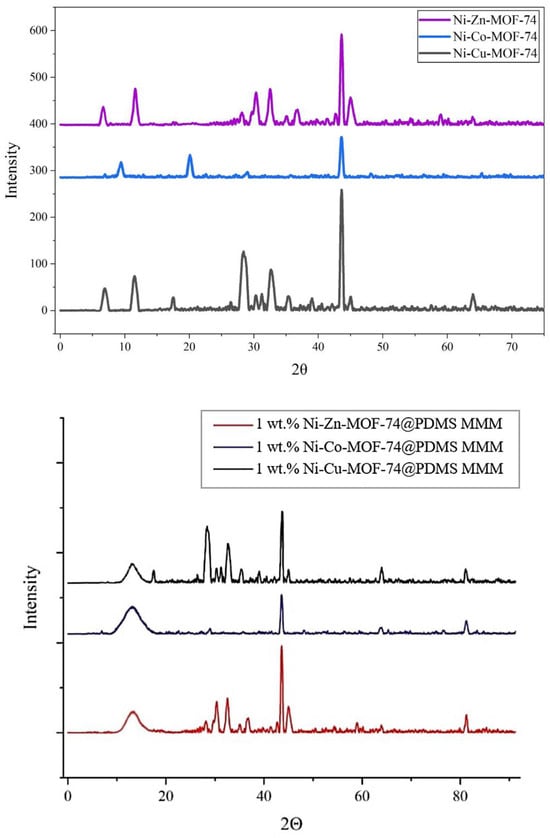

XRD analyses were carried out for Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 samples. The results of the analysis are represented in Figure 5 as shown:

Figure 5.

XRD spectra for Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 samples.

4.3.1. XRD Analysis of MOF Samples

The XRD patterns of Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Zn-MOF-74, and Ni-Co-MOF-74 exhibit the expected reflections corresponding to their crystalline frameworks. For Ni-Cu-MOF-74, a sharp reflection at 2θ = 43.2° is assigned to the Ni-based structure [37], while peaks at 6.7° and 11.6° correspond to the Cu-containing framework and agree with reported data [46]. In the case of Ni-Zn-MOF-74, the pattern includes the Ni-related peak at 43.2° together with reflections at 6.7° and 11.7° attributed to the Zn-based structure, consistent with previous studies [37,47]. For Ni-Co-MOF-74, a peak at 43.2° again indicates the Ni-based structure, and additional reflections at 9.2° and 20.2° are associated with the Co-containing framework [37,48]. Overall, the XRD profiles of the three samples are very similar, indicating that they share the same underlying topology [49]. The results, therefore, support the formation of isostructural MOFs in which the metal centres are varied while the framework structure is preserved [49].

4.3.2. XRD Analysis of MOF-Based MMMs

X-ray diffraction (XRD) was used to study the structure of PDMS-based mixed matrix membranes containing Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Zn-MOF-74, and Ni-Co-MOF-74 at a loading of 1 wt.% relative to PDMS. The diffraction patterns of the membranes show the characteristic MOF peaks superimposed on the broad amorphous halo of the PDMS phase, confirming that the crystalline fillers were successfully incorporated into the polymer matrix. The MOFs retain their signature reflections at higher 2θ values, corresponding to their well-defined crystalline planes and consistent with the reported structures of the respective frameworks. The persistence of these peaks after incorporation indicates that the MOF crystallinity is preserved within the PDMS matrix. Thus, the membranes consist of an amorphous PDMS phase containing dispersed crystalline MOF domains. This combination is expected to favour gas separation by coupling the molecular sieving behaviour of the MOFs with the intrinsic permeation characteristics of PDMS, making these MMMs suitable candidates for CO2 capture applications.

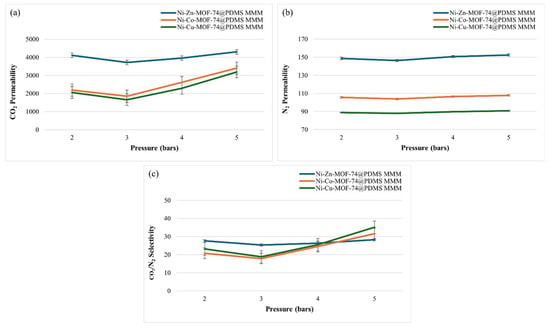

4.4. Gas Separation Performance Analysis

The gas separation performance of the MOF-based MMMs was evaluated by single-gas permeation experiments with CO2 and N2 using a stainless-steel permeation cell. The permeation data for membranes containing Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 are listed in Table 1. The corresponding trends in CO2 and N2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity as a function of feed pressure are shown in Figure 6.

Table 1.

Gas permeation analysis.

Figure 6.

Graphical representation of (a) CO2 permeability, (b) N2 permeability (c) CO2/N2 selectivity for MOF-incorporated MMMs.

In Figure 6a, the CO2 permeability of the MMMs containing Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, and Ni-Zn-MOF-74 generally increases with feed pressure, with a small decrease at 3 bar. This deviation is consistent with swelling and sorption effects in the PDMS phase, which can temporarily hinder gas transport [50]. Among the samples, the Ni-Zn-MOF-74-based MMM shows the highest CO2 permeability. This behaviour is associated with weaker framework–gas interactions and the slightly enlarged pore structure induced by Zn2+ incorporation, which reduces metal-ligand bond strength and promotes faster gas diffusion through the membrane [51,52,53]. The N2 permeability data in Figure 6b follow a similar pressure dependence, including a dip at 3 bar, and again the Ni-Zn-MOF-74 MMM exhibits the highest values, consistent with its larger effective pore size. The resulting CO2/N2 selectivities are plotted in Figure 6c. The 1 wt.% Ni-Cu-MOF-74@PDMS membrane achieves the highest selectivity, with a value of 35.10. Favourable interfacial interactions between the MOF fillers and the PDMS phase lead to a dense, defect-free morphology in the Ni-Cu-MOF-74-based MMM [54]. This good contact at the filler–polymer interface promotes more effective, selective transport pathways for CO2, as reflected in the high separation performance. By contrast, the Ni-Zn-MOF-74 MMM, although showing the highest CO2 permeability, exhibits the lowest CO2/N2 selectivity, illustrating the typical permeability–selectivity compromise observed in polymer-based MMMs [55]. Considering both parameters, the Ni-Cu-MOF-74@PDMS membrane offers the most favourable combination, with a CO2 permeability of 3188.25 Barrer and a CO2/N2 selectivity of 35.10, and is therefore identified as the best-performing composition in this work.

4.5. BET Analysis

The physical properties of the nickel-based MMMs containing Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Zn-MOF-74, and Ni-Co-MOF-74 are listed in Table 2. BET measurements show surface areas of 0.1166 m2/g for the Ni-Cu-MOF-74 MMM, 0.0070 m2/g for the Ni-Zn-MOF-74 MMM, and 0.0666 m2/g for the Ni-Co-MOF-74 MMM. Among the three, the Ni-Cu-MOF-74 membrane has the largest surface area, consistent with its higher CO2 permeability relative to pristine PDMS. The increased BET surface area indicates a more developed porous structure, providing a greater number of accessible sites for gas adsorption and transport.

Table 2.

BET Analysis.

The BET and permeation data indicate that the Ni-Cu-MOF-74-based MMM combines high surface area with strong framework–CO2 interactions. The presence of both Ni and Cu metal centres in the MOF lattice likely increases the number and variety of CO2 adsorption sites, enhancing CO2 affinity. This bimetallic composition also improves the dispersion of the MOF particles within the PDMS phase, limiting interfacial defects and strengthening polymer–filler contact. The higher BET surface area of the Ni-Cu-MOF-74 membrane is consistent with a more accessible porous network, which promotes CO2 uptake and diffusion through the matrix. These structural features account for the observed increase in CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity, making the Ni-Cu-MOF-74-based MMM well suited for CO2 separation applications.

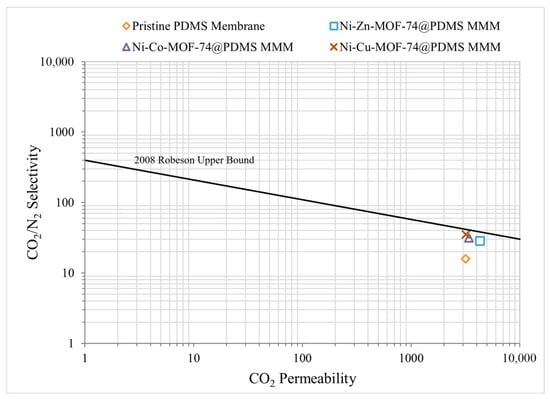

5. Performance Comparison

The Robeson (2008) [16] upper bound was used as a reference to assess the balance between gas permeability and ideal selectivity. The performance of all fabricated membranes plotted in Figure 7 shows that the MOF-based MMMs shift above the position of pristine PDMS, with simultaneous increases in CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity. Among the modified membranes, the PDMS membrane containing 1 wt.% Ni-Cu-MOF-74 exhibits the largest deviation from the upper bound of pristine PDMS, reflecting the most pronounced improvement in separation performance. The PDMS/Ni-Zn-MOF-74 and PDMS/Ni-Co-MOF-74 MMMs also show clear gains in both permeability and selectivity relative to the unfilled polymer. These trends indicate that incorporation of MOF-74-type fillers effectively enhances the transport properties of the PDMS matrix and yields a more favourable compromise between CO2 permeability and CO2/N2 selectivity.

Figure 7.

Performance Analysis of Membrane Samples.

6. Conclusions

Membrane-based carbon capture offers a practical route to reducing CO2 emissions from industrial sources. In this work, mixed matrix membranes (MMMs) were prepared using PDMS as the continuous phase and Ni-Cu-MOF-74, Ni-Co-MOF-74, or Ni-Zn-MOF-74 as dispersed fillers. The membranes were fabricated by solution casting and examined by XRD, SEM, FT-IR, and BET analysis. These characterizations confirmed the formation of smooth, dense, defect-free films with well-dispersed MOF particles in the PDMS matrix. Single-gas permeation tests with CO2 and N2 showed that incorporation of Ni-Cu-MOF-74 at 1 wt.% provided the most favourable transport properties. The 1 wt.% Ni-Cu-MOF-74@PDMS membrane reached a CO2/N2 selectivity of 35.10 and a CO2 permeability of 3188.25 Barrer, both higher than those of pristine PDMS, and representing a good compromise between permeability and selectivity. Overall, the results indicate that PDMS-based MMMs containing bimetallic MOF-74 fillers, particularly Ni-Cu-MOF-74, are suitable candidates for CO2/N2 separation in industrial gas treatment and CO2 capture processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.A., M.A. and T.N.; methodology and visualization, S.A. and H.R.; investigation, S.A.; resources and validation, T.N. and S.F.; writing—original draft preparation, S.A.; writing—review and editing and supervision, M.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors hereby acknowledge the technical support provided by Sarah Farrukh from MEMAR Lab, School of Chemical and Materials Engineering (SCME), National University of Sciences and Technology (NUST), Islamabad, Pakistan.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Omer, A.M. Energy, Environment and Sustainable Development. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2008, 12, 2265–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, G.; Zou, X.; Sun, L.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, P.; Zhu, G. Constructing Connected Paths between UiO-66 and PIM-1 to Improve Membrane CO2 Separation with Crystal-Like Gas Selectivity. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lashof, D.A.; Ahuja, D.R. Relative Contributions of Greenhouse Gas Emissions to Global Warming. Nature 1990, 344, 529–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Z. Agglomeration Effect of CO2 Emissions and Emissions Reduction Effect of Technology: A Spatial Econometric Perspective Based on China’s Province-Level Data. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 204, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, D.M.; Smit, B.; Long, J.R. Carbon Dioxide Capture: Prospects for New Materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 6058–6082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Mamoori, A.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Rownaghi, A.A.; Rezaei, F. Carbon Capture and Utilization Update. Energy Technol. 2017, 5, 834–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.R.; Ma, Y.; McCarthy, M.C.; Sculley, J.; Yu, J.; Jeong, H.K.; Balbuena, P.B.; Zhou, H.C. Carbon Dioxide Capture-Related Gas Adsorption and Separation in Metal-Organic Frameworks. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2011, 255, 1791–1823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Feron, P.H.M.; Deng, L.; Favre, E.; Chabanon, E.; Yan, S.; Hou, J.; Chen, V.; Qi, H. Status and Progress of Membrane Contactors in Post-Combustion Carbon Capture: A State-of-the-Art Review of New Developments. J. Memb. Sci. 2016, 511, 180–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Zhu, G. Microporous Organic Materials for Membrane-Based Gas Separation. Adv. Mater. 2018, 30, 1700750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W. Membrane Technology and Applications; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Mohshim, D.F.; Mukhtar, H.B.; Man, Z.; Nasir, R. Latest Development on Membrane Fabrication for Natural Gas Purification: A Review. J. Eng. 2013, 2013, 101746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangnekar, N.; Mittal, N.; Elyassi, B.; Caro, J.; Tsapatsis, M. Zeolite Membranes—A Review and Comparison with MOFs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2015, 44, 7128–7154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Tang, C.Y. Novel Membranes and Membrane Materials. In Membrane-Based Salinity Gradient Processes for Water Treatment and Power Generation; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 201–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.B.; Lee, S.W.; Park, J.S.; Lee, D.W.; Hwang, K.R.; Ryi, S.K.; Kim, S.H. Long-Term CO2 Capture Tests of Pd-Based Composite Membranes with Module Configuration. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2013, 38, 7896–7903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fard, A.K.; McKay, G.; Buekenhoudt, A.; Al Sulaiti, H.; Motmans, F.; Khraisheh, M.; Atieh, M. Inorganic Membranes: Preparation and Application for Water Treatment and Desalination. Materials 2018, 11, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robeson, L.M. The Upper Bound Revisited. J. Memb. Sci. 2008, 320, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulze, A.; Marquardt, B.; Went, M.; Prager, A.; Buchmeiser, M.R. Electron Beam-Based Functionalization of Polymer Membranes. Water Sci. Technol. 2012, 65, 574–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koros, W.J.; Mahajan, R. Pushing the Limits on Possibilities for Large Scale Gas Separation: Which Strategies? J. Memb. Sci. 2001, 181, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.W.; Low, B.T. Gas Separation Membrane Materials: A Perspective. Macromolecules 2014, 47, 6999–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Fan, Y.; Wu, L.; Zhang, L.; Guan, D.; Ma, C.; Li, N. Ultra-Selective Molecular-Sieving Gas Separation Membranes Enabled by Multi-Covalent-Crosslinking of Microporous Polymer Blends. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Chernikova, V.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Belmabkhout, Y.; Shekhah, O.; Zhang, C.; Yi, S.; Eddaoudi, M.; Koros, W.J. Mixed Matrix Formulations with MOF Molecular Sieving for Key Energy-Intensive Separations. Nat. Mater. 2018, 17, 283–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiaz, A.; Othman, M.H.D.; Jilani, A.; Khan, I.U.; Kamaludin, R.; Samuel, O. ZIF-Filler Incorporated Mixed Matrix Membranes (MMMs) for Efficient Gas Separation: A Review. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 108541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robeson, L.M. Correlation of Separation Factor versus Permeability for Polymeric Membranes. J. Memb. Sci. 1991, 62, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzaqui, M.; Pillai, R.S.; Sabetghadam, A.; Benoit, V.; Normand, P.; Marrot, J.; Menguy, N.; Montero, D.; Shepard, W.; Tissot, A.; et al. Revisiting the Aluminum Trimesate-Based MOF (MIL-96): From Structure Determination to the Processing of Mixed Matrix Membranes for CO2 Capture. Chem. Mater. 2017, 29, 10326–10338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waqas Anjum, M.; Bueken, B.; De Vos, D.; Vankelecom, I.F.J. MIL-125(Ti) Based Mixed Matrix Membranes for CO2 Separation from CH4 and N2. J. Memb. Sci. 2016, 502, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Q.; Nataraj, S.K.; Roussenova, M.V.; Tan, J.C.; Hughes, D.J.; Li, W.; Bourgoin, P.; Alam, M.A.; Cheetham, A.K.; Al-Muhtaseb, S.A.; et al. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF-8) Based Polymer Nanocomposite Membranes for Gas Separation. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 8359–8369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Jie, X.; Liu, D.; Cao, Y.; Yuan, Q. Post-Treatment Effect on Gas Separation Property of Mixed Matrix Membranes Containing Metal Organic Frameworks. J. Memb. Sci. 2014, 466, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, J.O.; Balkus, K.J.; Ferraris, J.P.; Musselman, I.H. MIL-53 Frameworks in Mixed-Matrix Membranes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 196, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anjum, M.W.; Vermoortele, F.; Khan, A.L.; Bueken, B.; De Vos, D.E.; Vankelecom, I.F.J. Modulated UiO-66-Based Mixed-Matrix Membranes for CO2 Separation. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 25193–25201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, M.A.; de Ribeiro, J.S.; de Costa, E.S.; de Miranda, J.L.; Ferraz, H.C. Nanostructured Membranes Containing UiO-66 (Zr) and MIL-101 (Cr) for O2/N2 and CO2/N2 Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 192, 491–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Luo, S.; Weidman, J.R.; Guo, R. Preparation and Gas Separation Performance of Mixed-Matrix Membranes Based on Triptycene-Containing Polyimide and Zeolite Imidazole Framework (ZIF-90). Polymer 2017, 131, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.C.; Sun, D.T.; Beavers, C.M.; Britt, D.K.; Queen, W.L.; Urban, J.J. Enhanced Permeation Arising from Dual Transport Pathways in Hybrid Polymer–MOF Membranes. Energy Environ. Sci. 2016, 9, 922–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venna, S.R.; Lartey, M.; Li, T.; Spore, A.; Kumar, S.; Nulwala, H.B.; Luebke, D.R.; Rosi, N.L.; Albenze, E. Fabrication of MMMs with Improved Gas Separation Properties Using Externally-Functionalized MOF Particles. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2015, 3, 5014–5022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Q.; Ouyang, J.; Liu, T.; Li, Z.; Li, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, S.; Wu, H.; Jiang, Z.; Cao, X. Enhanced Interfacial Interaction and CO2 Separation Performance of Mixed Matrix Membrane by Incorporating Polyethylenimine-Decorated Metal-Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 1065–1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loloei, M.; Kaliaguine, S.; Rodrigue, D. CO2-Selective Mixed Matrix Membranes of Bimetallic Zn/Co-ZIF vs. ZIF-8 and ZIF-67. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2022, 296, 121391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Feng, S.; Luo, J.; Zhuang, Y.; Song, W.; Li, X.; Wan, Y. Pebax Mixed Matrix Membrane with Bimetallic CeZr-MOFs to Enhance CO2 Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 322, 124251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asad, E.; Raza, A.; Safdar, A.; Khan, M.N.A.; Roafi, H. Advanced Cellulose Triacetate-Based Mixed Matrix Membranes Enhanced by Bimetallic Ni-Cu-BTC MOFs for CO2/CH4 Separation. Polymers 2025, 17, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daglar, H.; Erucar, I.; Keskin, S. Recent Advances in Simulating Gas Permeation through MOF Membranes. Mater. Adv. 2021, 2, 5300–5317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, K.C.; Lai, S.O.; Thiam, H.S.; Teoh, H.C.; Heng, S.L. Recent Progress of Oxygen/Nitrogen Separation Using Membrane Technology. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. 2016, 11, 1016–1030. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, B.D. Basis of Permeability/Selectivity Tradeoff Relations in Polymeric Gas Separation Membranes. Macromolecules 1999, 32, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayub, A.; Farrukh, S.; Jan, R.; Azeem, M.; Salahuddin, Z.; Hussain, A. Gas Barrier Properties Evaluation for Boron Nitride Nanosheets-Polymer (Polyethylene-Terephthalate) Composites. Appl. Nanosci. 2021, 11, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leo, P.; Orcajo, G.; Briones, D.; Calleja, G.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.; Martínez, F. A Recyclable Cu-MOF-74 Catalyst for the Ligand-Free O-Arylation Reaction of 4-Nitrobenzaldehyde and Phenol. Nanomaterials 2017, 7, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.J.; Chen, J.K.; Lin, K.S.; Huang, C.Y.; Huang, C.L. Improved H2 Production of ZnO@ZnS Nanorod-Decorated Ni Foam Immobilized Photocatalysts. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 46, 11357–11368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah Buddin, M.M.H.; Ahmad, A.L. A Review on Metal-Organic Frameworks as Filler in Mixed Matrix Membrane: Recent Strategies to Surpass Upper Bound for CO2 Separation. J. CO2 Util. 2021, 51, 101616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopi, S.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M.; Al-onazi, W.A.; Soliman Elshikh, M.; Yun, K. Metal Organic Framework-Derived Ni-Cu Bimetallic Electrocatalyst for Efficient Oxygen Evolution Reaction. J. King Saud. Univ. Sci. 2021, 33, 101379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.L.; Chen, L.B.; Li, M.H.; Lu, J.X.; Wang, H. Cu-MOF-74-Derived CuO-400 Material for CO2 Electroreduction. Catalysts 2024, 14, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzbahari, S.; Mehri Lighvan, Z.; Ghadimi, A.; Sadatnia, B. ZIF-8@Zn-MOF-74 Core–Shell Metal–Organic Framework (MOF) with Open Metal Sites: Synthesis, Characterization, and Gas Adsorption Performance. Fuel 2023, 339, 127463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshorifi, F.T.; El Dafrawy, S.M.; Ahmed, A.I. Fe/Co-MOF Nanocatalysts: Greener Chemistry Approach for the Removal of Toxic Metals and Catalytic Applications. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 23421–23444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sui, Y.; Wei, F.; Qi, J.; Meng, Q.; Ren, Y.; He, Y. Self-Supported 3D Layered Zinc/Nickel Metal-Organic-Framework with Enhanced Performance for Supercapacitors. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 2019, 30, 18101–18110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibrov, G. Polydimethylsiloxane Membrane. In Encyclopedia of Membranes; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 1591–1593. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, W.; Wang, L.; Liang, W.; Guo, R.; Li, Z. Bimetallic MOF-74-Based Mixed Matrix Membrane for Efficient CO2 Separation. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2024, 379, 113288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Hong, C.S. MOF-74-Type Frameworks: Tunable Pore Environment and Functionality through Metal and Ligand Modification. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 1377–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wasik, D.O.; Vicent-Luna, J.M.; Luna-Triguero, A.; Dubbeldam, D.; Vlugt, T.J.H.; Calero, S. The Impact of Metal Centers in the M-MOF-74 Series on Carbon Dioxide and Hydrogen Separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2024, 339, 126539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Shamsaei, E.; Lin, X.; Hu, Y.; Simon, G.P.; Seong, J.G.; Kim, J.S.; Lee, W.H.; Lee, Y.M.; Wang, H. The Enhanced Hydrogen Separation Performance of Mixed Matrix Membranes by Incorporation of Two-Dimensional ZIF-L into Polyimide Containing Hydroxyl Group. J. Memb. Sci. 2018, 549, 260–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Lian, S.; Li, R.; Yu, Z.; Liu, Q.; Zang, G.L.; Song, C. Architecting MOFs-Based Mixed Matrix Membrane for Efficient CO2 Separation: Ameliorating Strategies toward Non-Ideal Interface. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 443, 136290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).