Preparation of Cu-MnO2/GO/PVDF Catalytic Membranes via Phase Inversion Method and Application for Separation Removal of Dyes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experiment

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of GO and Cu-MnO2

2.3. Preparation of Catalytic Membrane

2.4. Instruments and Characteristics

2.5. Average Contact Angle and Water Flux

2.6. Separation and Degradation Evaluation

3. Results and Discussion

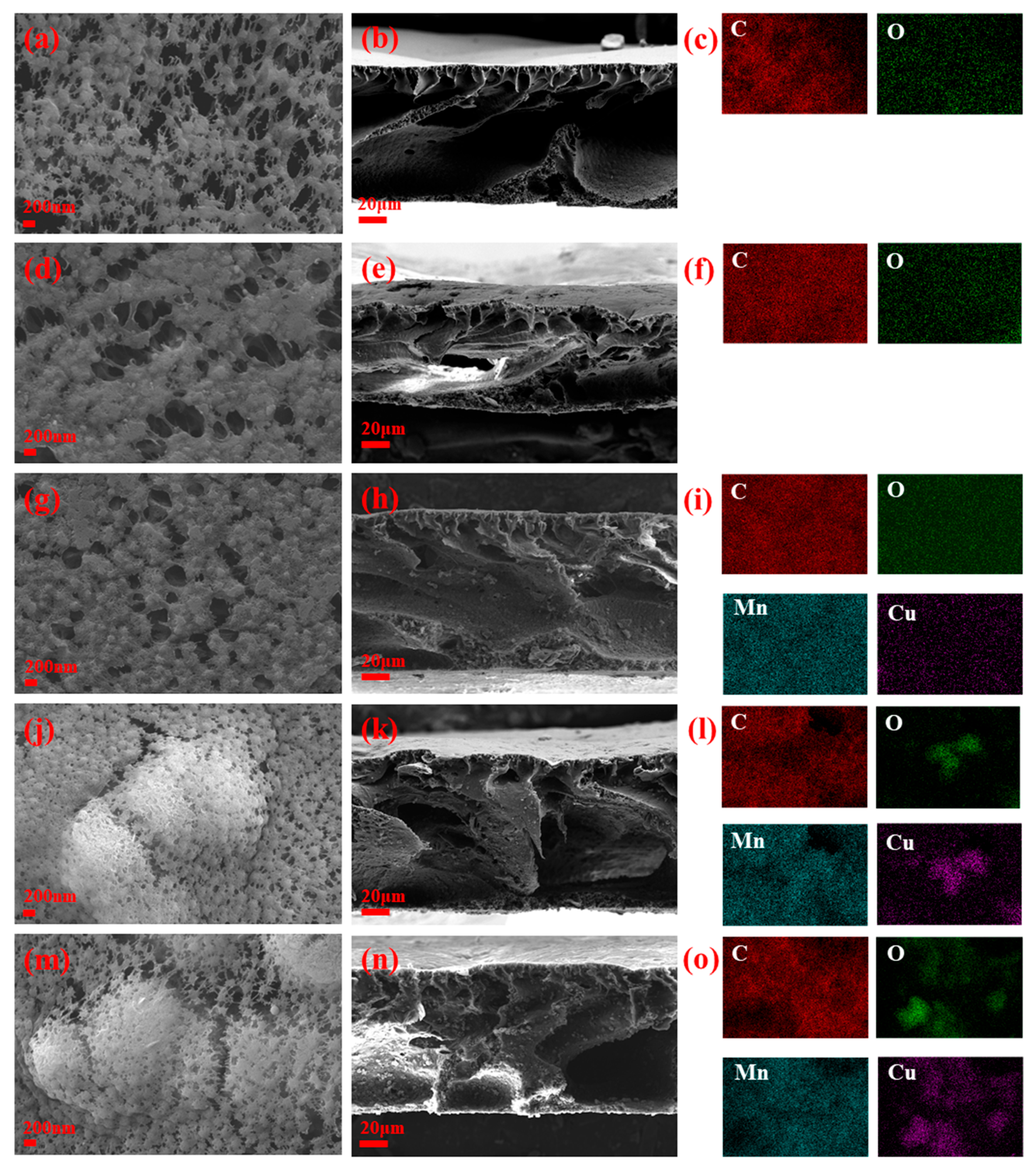

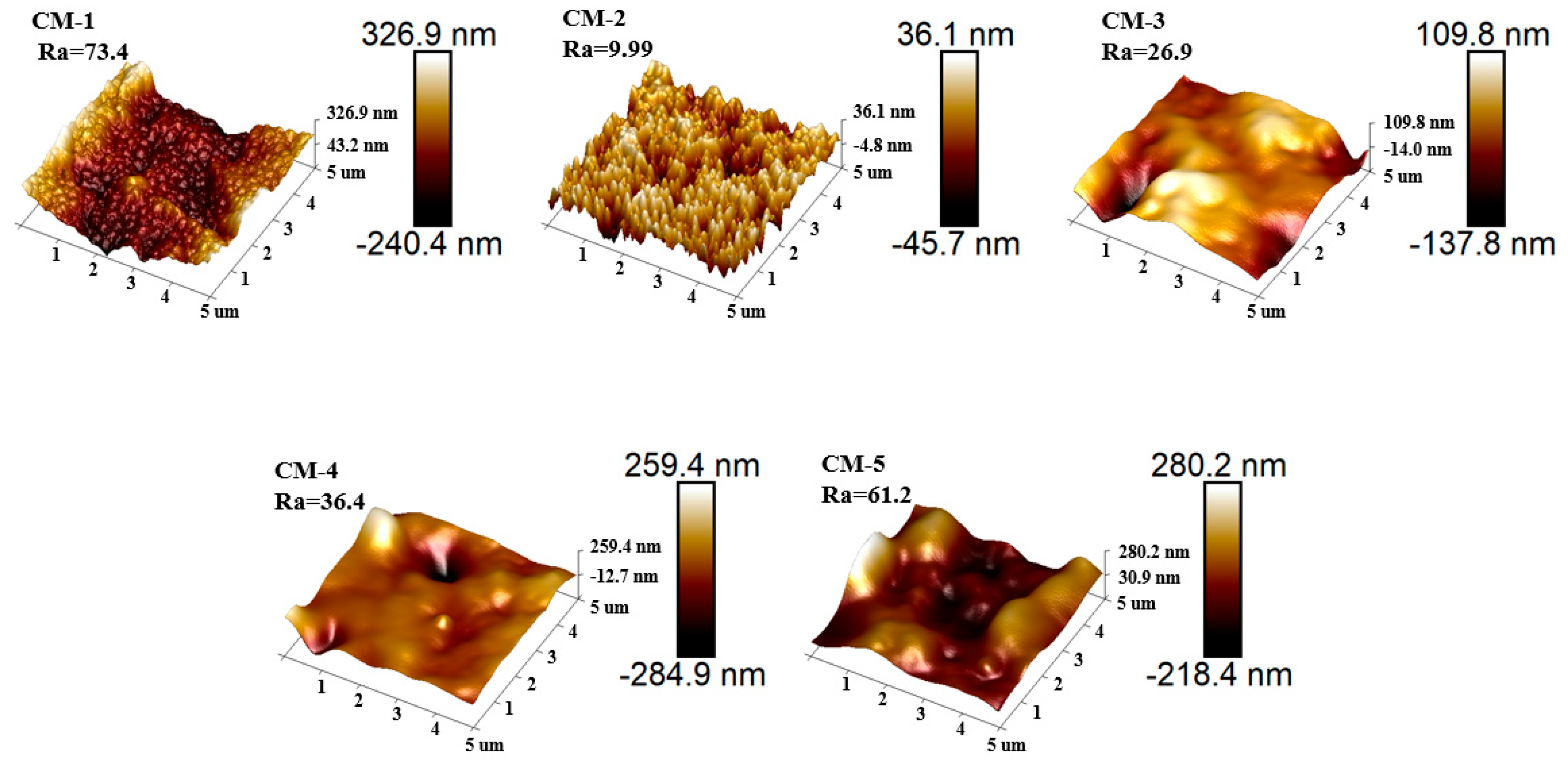

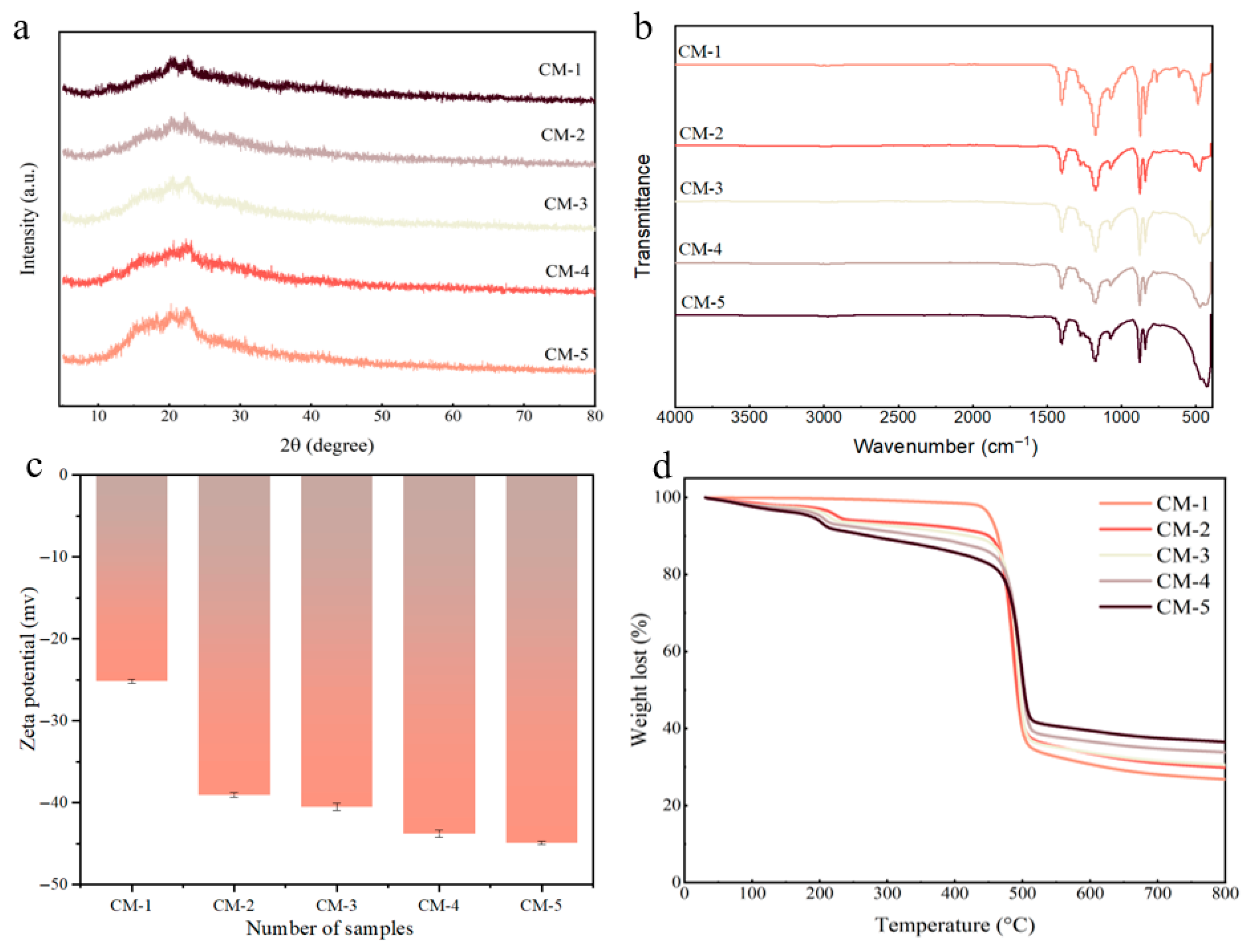

3.1. Structure and Morphology Characterization of Membrane

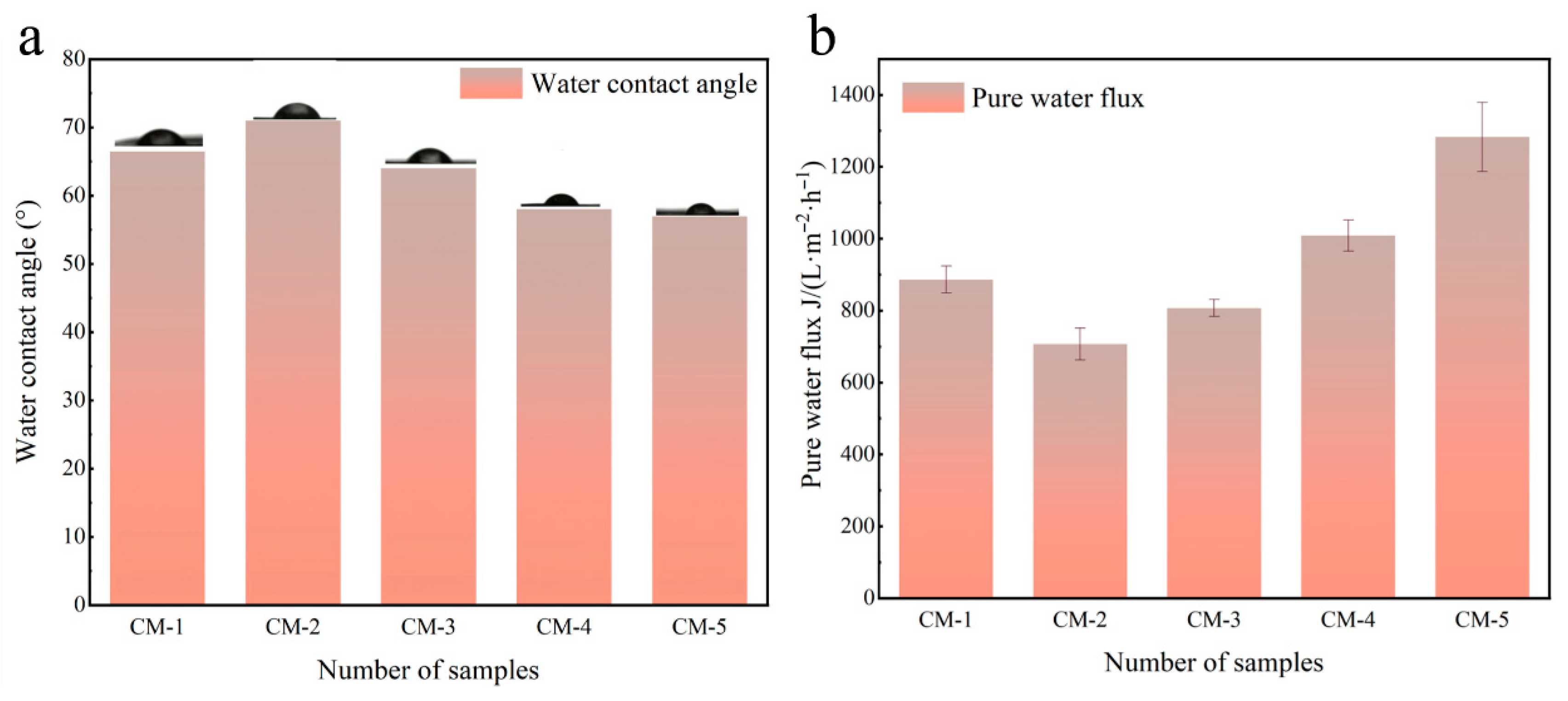

3.2. Membrane Performance

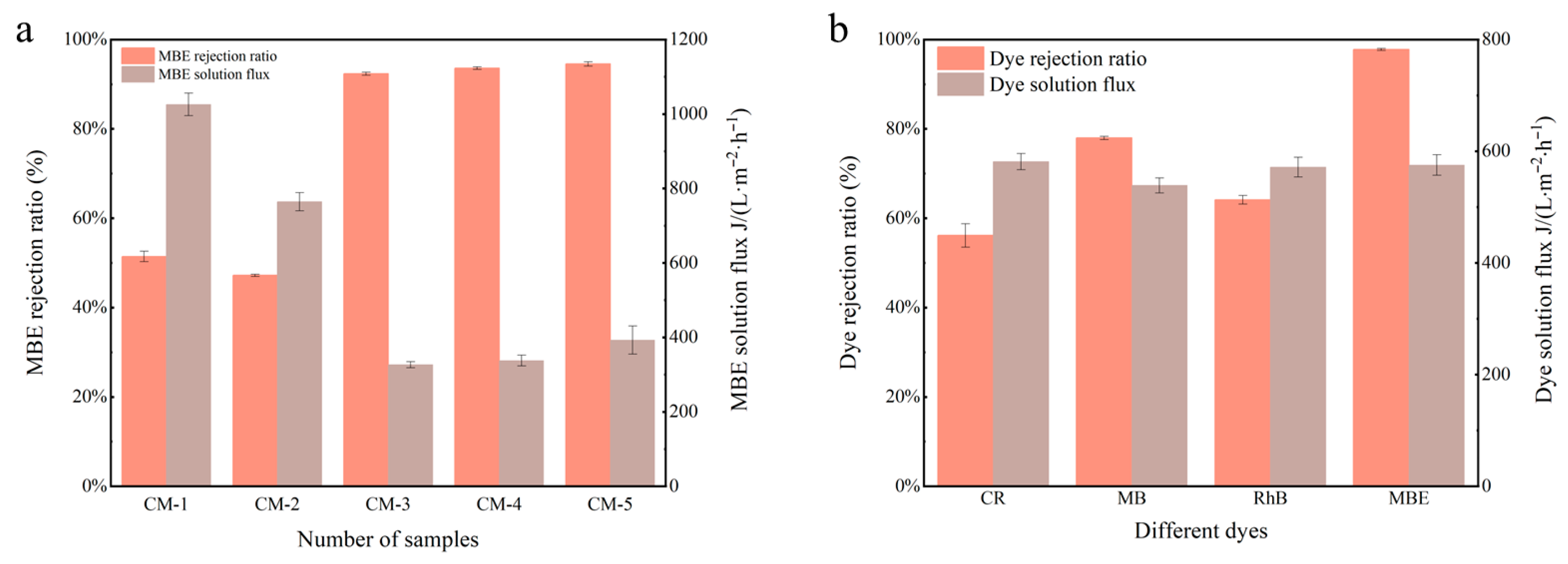

3.2.1. Membrane Flux and Interception

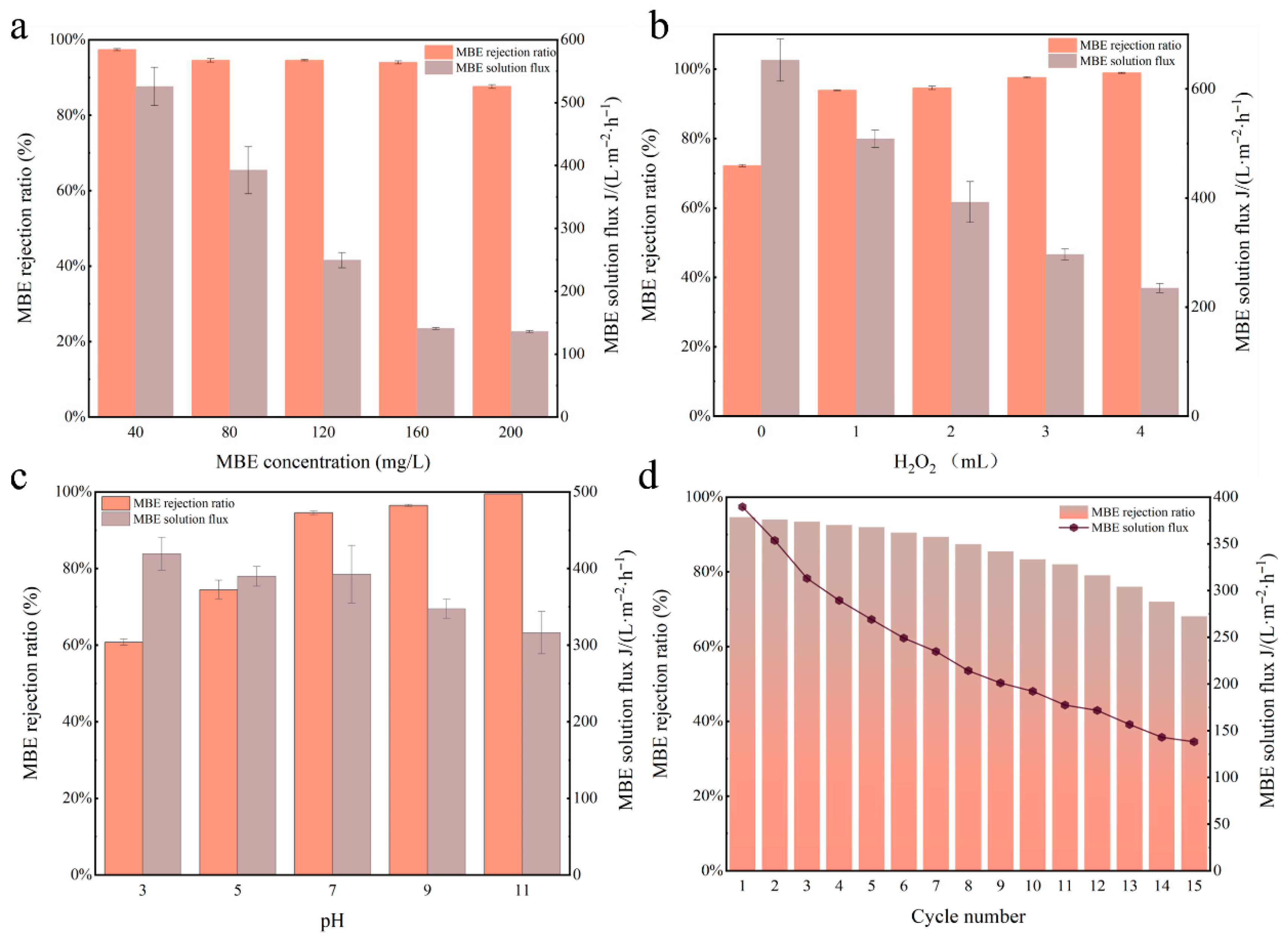

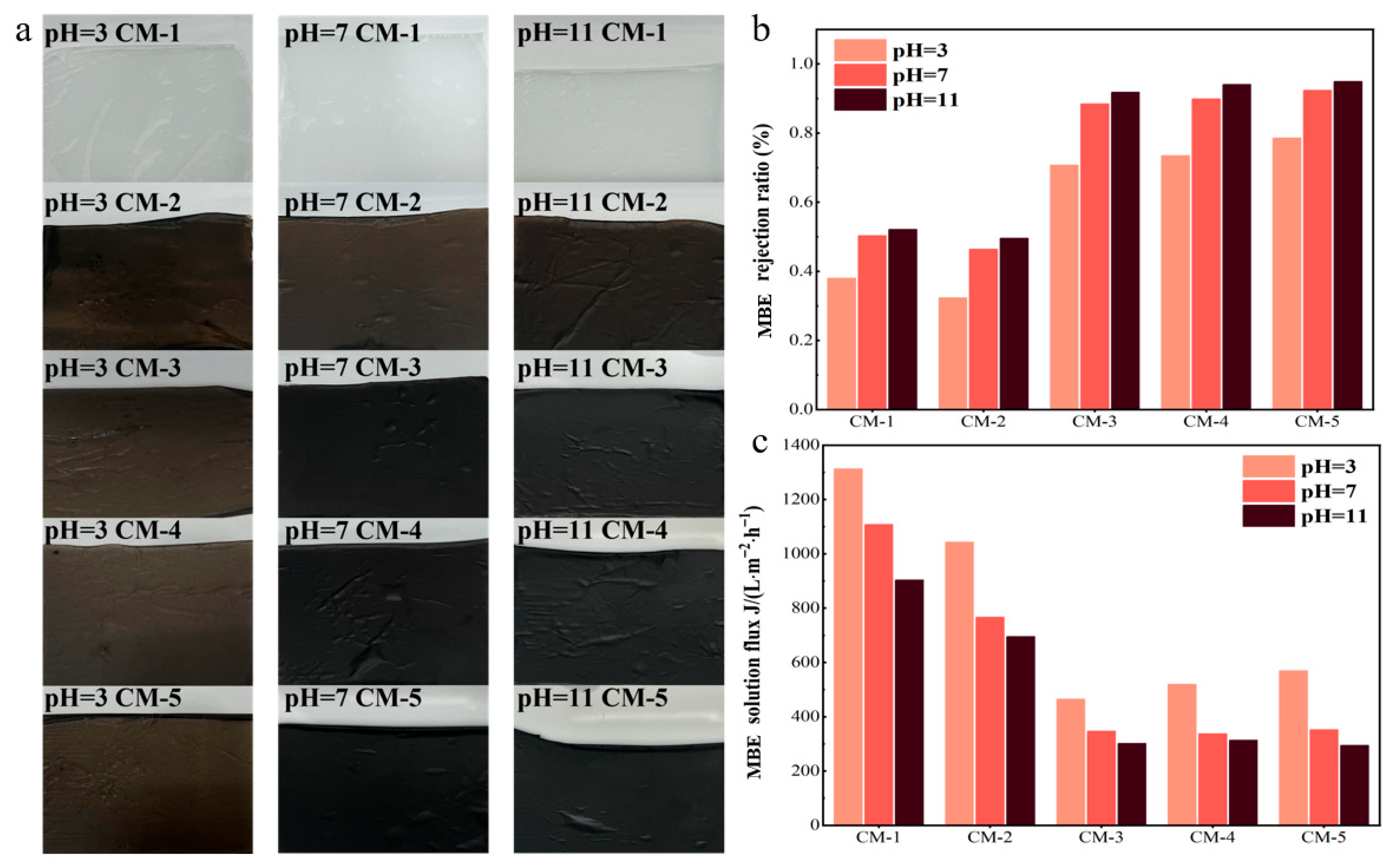

3.2.2. Study on the Stability of the Membrane

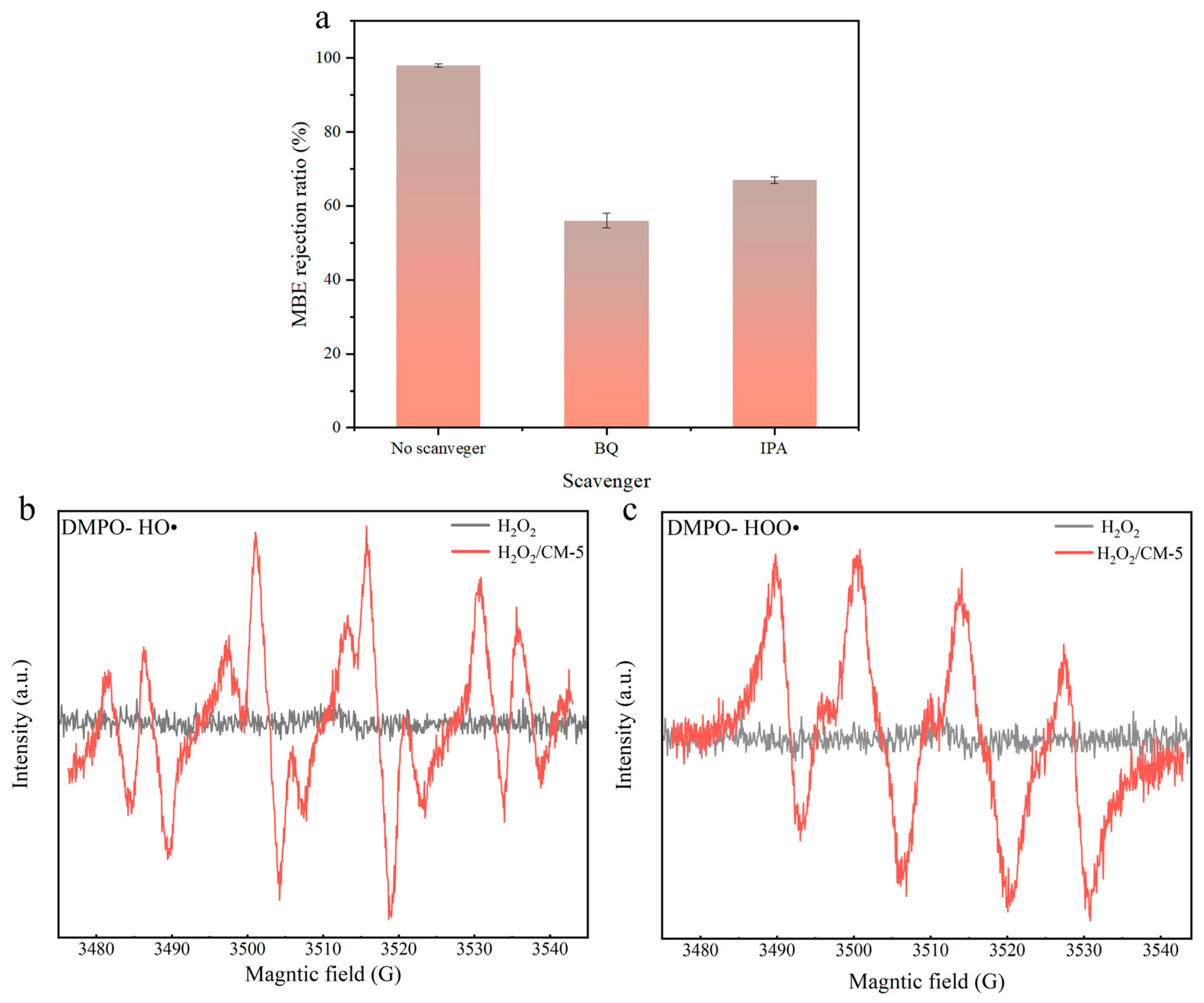

3.2.3. Degradation Mechanism

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yu, H.; Shangguan, S.; Yang, H.; Rong, H.; Qu, F. Chemical cleaning and membrane aging of poly (vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) membranes fabricated via non-solvent induced phase separation (NIPS) and thermally induced phase separation (TIPS). Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 313, 123488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Li, T.; Cao, J.; Sun, Z.; Xue, C.; Huang, C.; Zhao, W.; Zeng, H. Preparation of novel ACMO-AA/PVDF composite membrane by one-step process and its application in removal of heavy metal ions from aqueous solutions. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 702, 135163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, W.; Li, R.; Wang, M.; Gao, Q.; Li, J.; Lin, H. Fabrication of hydrophilic and antibacterial poly (vinylidene fluoride) based separation membranes by a novel strategy combining radiation grafting of poly (acrylic acid) (PAA) and electroless nickel plating. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2019, 543, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Li, R.; Hong, H.; Shen, L.; Lin, H.; Liao, B.-Q. Enhanced permeability and antifouling performance of polyether sulfone (PES) membrane via elevating magnetic Ni@MXene nanoparticles to upper layer in phase inversion process. J. Membr. Sci. 2021, 623, 119080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, J.; Zhang, D.; Fu, Y.; Ni, Y.; Wang, Y.; Protsak, I.; Yang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Tan, J.; Yang, J. Comb-like structural modification stabilizes polyvinylidene fluoride membranes to realize thermal-regulated sustainable transportation efficiency. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 591, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efome, J.E.; Baghbanzadeh, M.; Rana, D.; Matsuura, T.; Lan, C.Q. Effects of superhydrophobic SiO2 nanoparticles on the performance of PVDF flat sheet membranes for vacuum membrane distillation. Desalination 2015, 373, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Y.; Liu, F.; Xue, L. Under seawater superoleophobic PVDF membrane inspired by polydopamine for efficient oil/seawater separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2015, 476, 321–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manouras, E.; Ioannou, D.; Zeniou, A.; Sapalidis, A.; Gogolides, E. Superhydrophobic and oleophobic Nylon, PES and PVDF membranes using plasma nanotexturing: Empowering membrane distillation and contributing to PFAS free hydrophobic membranes. Micro Nano Eng. 2024, 24, 100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Yang, J. Fabrication and modification of PVDF membrane by PDA@ZnO for enhancing hydrophilic and antifouling property. Arab. J. Chem. 2023, 16, 105206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.X.; Zuo, X.; Liu, Q.L.; He, H.; Chen, S.G. The Transition Matal Doping Effect on the Catalytic Activity of α-MnO2 for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Hans J. Chem. Eng. Technol. 2020, 10, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ongayo, G.; Magallanes, P. Efficient Removal of Aqueous Copper (II) Ions Using EDTA-Modified Graphene Oxide: An Adsorption Study. Eng. Chem. 2024, 8, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahich, S.; Saini, Y.K.; Devra, V.; Aggarwal, K.; Kumar, A.; Kumar, D.; Singh, A.; Arya, Y. Metal-free adsorption and photodegradation methods for methylene blue dye removal using different reduction grades of graphene oxide. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Du, R.; Cao, Z.; Li, C.; Xue, J.; Ma, X.; Wang, S. Research Progress in Graphene-Based Adsorbents for Wastewater Treatment: Preparation, Adsorption Properties and Mechanisms for Inorganic and Organic Pollutants. C 2024, 10, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fashandi, H.; Abolhasani, M.M.; Sandoghdar, P.; Zohdi, N.; Li, Q.; Naebe, M. Morphological changes towards enhancing piezoelectric properties of PVDF electrical generators using cellulose nanocrystals. Cellulose 2016, 23, 3625–3637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anegbe, B.; Ifijen, I.H.; Maliki, M.; Uwidia, I.E.; Aigbodion, A.I. Graphene oxide synthesis and applications in emerging contaminant removal: A comprehensive review. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2024, 36, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebrekrstos, A.; Muzata, T.S.; Ray, S.S. Nanoparticle-Enhanced β-Phase Formation in Electroactive PVDF Composites: A Review of Systems for Applications in Energy Harvesting, EMI Shielding, and Membrane Technology. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2022, 5, 7632–7651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Li, J.; Li, R.; He, R.; Gao, W.; Yu, N. Preparation of Heterogeneous Fenton Catalysts Cu-Doped MnO2 for Enhanced Degradation of Dyes in Wastewater. Nanomaterials 2024, 14, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hummers, W.S., Jr.; Offeman, R.E. Preparation of Graphitic Oxide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1958, 80, 1339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhou, Z.; Xie, A.; Wang, Q.; Liu, S.; Lang, J.; Li, C.; Yan, Y.; Dai, J. Facile preparation of grass-like structured NiCo-LDH/PVDF composite membrane for efficient oil–water emulsion separation. J. Membr. Sci. 2019, 573, 226–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, G.; Jin, X.; Hu, H. Electrospun polyvinylidene fluoride/polyacrylonitrile composite fibers: Fabrication and characterization. Iran. Polym. J. 2020, 29, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunkalekar, R.K.; Salker, A.V. Low temperature CO oxidation over nano-sized Cu–Pd doped MnO2 catalysts. React. Kinet. Mech. Catal. 2013, 108, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahari, A.M.; Shuo, C.W.; Sathishkumar, P.; Yusoff, A.R.M.; Gu, F.L.; Buang, N.A.; Lau, W.-J.; Gohari, R.J.; Yusop, Z. A reusable electrospun PVDF-PVP-MnO2 nanocomposite membrane for bisphenol A removal from drinking water. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018, 6, 5801–5811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Majalca, B.C.; Domínguez-Arvizu, J.L.; Ibarra -Rodríguez, L.I.; Valenzuela-Castro, G.E.; Gaxiola-Cebreros, F.A.; Ocampo-Pérez, R.; Padilla-Ortega, E.; Collins-Martínez, V.H.; López-Ortiz, A. Comparative study of photocatalytic hydrogen production using high charge carrier mobility graphene Oxide-TiO2 heterojunctions. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 161, 150638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aradhana, R.; Mohanty, S.; Nayak, S.K. Comparison of mechanical, electrical and thermal properties in graphene oxide and reduced graphene oxide filled epoxy nanocomposite adhesives. Polymer 2018, 141, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhou, L.; Huang, X. Upgrading MnO2@CuO with GO as a superior heterogeneous nanocatalyst for transesterification of dairy waste oils to biodiesel through electrolysis procedure. Mater. Today Sustain. 2023, 24, 100607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, D.; Rath, C. Structural, optical and magnetic properties of α- and β-MnO2 nanorods. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 557, 149693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Z.; Li, Z.; Guo, M.; Li, P.; Da, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, Y.; He, Y.; Chen, J. MnO2-x nanowires on carbon cloth based superamphiphilic and under-oil superhydrophilic filtration membrane for oil/water separation with robust anti-oil fouling performance. Compos. Part B Eng. 2020, 199, 108286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Sheng, Q.; Wei, J.; Wen, Q.; Ma, D.; Li, J.; Xie, Y.; Shen, J.; Sun, X. Novel strategy for membrane biofouling control in MBR with nano-MnO2 modified PVDF membrane by in-situ ozonation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 151996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, G.; Galiano, F.; Yoo, M.J.; Mancuso, R.; Park, H.B.; Gabriele, B.; Figoli, A.; Drioli, E. Development of graphene-PVDF composite membranes for membrane distillation. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 604, 118017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Xu, X.; Shi, L.; Yin, Y.; Zhang, L.-C.; Wu, Z.; Duan, X.; Wang, S.; Sun, H. Manganese oxide integrated catalytic ceramic membrane for degradation of organic pollutants using sulfate radicals. Water Res. 2019, 167, 115110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 5749-2022; Standards for Drinking Water Quality. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Li, X.; Yu, Z.; Shao, L.; Feng, X.; Zeng, H.; Liu, Y.; Long, R.; Zhu, X. Self-cleaning photocatalytic PVDF membrane loaded with NH2-MIL-88B/CDs and Graphene oxide for MB separation and degradation. Opt. Mater. 2021, 119, 111368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, L.; Gao, W.; Zhou, Z.; Chang, M. Integrated α-MnO2 nanowires PVDF catalytic membranes for efficient puri-fication of dye wastewater with high permeability. J. Water Process Eng. 2023, 56, 104315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.R.; James, A.; Mohamed Said, K.A.; Namakka, M.; Khandaker, M.U.; Jiunn, W.H.; Al-Humaidi, J.Y.; Althomali, R.H.; Rahman, M.M. A TiO2 grafted bamboo derivative nanocellulose polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) nanocomposite mem-brane for wastewater treatment by a photocatalytic process. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 7617–7636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zheng, X.; Zhu, M.; Xiao, C.; Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, L. CuO-Fe3C-C modified PVDF membrane for catalysis and antifouling. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2025, 355, 129601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Xu, H.; Li, R.; Quan, L.; Zhan, C.; Han, P.; Liu, Y.; Tong, Y. g-C3N4 coupled with GO accelerates carrier separation via high conductivity for photocatalytic MB degradation. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 703, 135311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Xu, D. Development of multifunctional and freestanding PVDF/SMA/CuS membranes with antibacterial, oil-water separation and dye degradation for wastewater treatment. Surf. Interfaces 2025, 77, 108026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Wang, Y.; Huang, H.; Ma, S.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z.-L. High efficient reduction of 4-nitrophenol and dye by filtration through Ag NPs coated PAN-Si catalytic membrane. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 127995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Membrane | GO (g) | Cu-MnO2 (g) | PVDF (g) | NMP (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CM-1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 30 |

| CM-2 | 0.5 | 0 | 3 | 30 |

| CM-3 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 3 | 30 |

| CM-4 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 3 | 30 |

| CM-5 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 3 | 30 |

| Substrate | Catalyst | Dye | Co (PPm) | Jdye (L m−2 h−1) | Testing Condition (MPa) | Rdye (%) | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVDF | PVP-MnO2 | BPA | 10 | 469.02 | 0.1 | 100 | [22] |

| PVDF/GO | NH2-MIL-88B (Fe) | MB | 20 | 335.07 | 0.1 | 99.6 | [32] |

| CS/GO/PVDF | α-MnO2 | MBE | 40 | 923.72 | 0.1 | 97.78 | [33] |

| PVDF | NC/TiO | MB | 1 | 274.23 | 0.1 | 98 | [34] |

| PVDF | CuO-Fe3C-C | TC | 12 | 422.27 | 0.1 | 97.9 | [35] |

| PVDF | SMA/CuS | RhB | 10 | 735.3 | 0.1 | 99.7 | [36] |

| PVDF | MgFe2O | RhB | 20 | 1792 | 0.1 | 99 | [37] |

| PAN-Si | Ag NPs | Methyl orange | 1 | 230 | 0.1 | 99 | [38] |

| PVDF | Cu-MnO2-GO | MBE | 80 | 434.94 | 0.1 | 100 | This work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, F.; Hou, X.; He, R.; Song, J.; Xie, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, X. Preparation of Cu-MnO2/GO/PVDF Catalytic Membranes via Phase Inversion Method and Application for Separation Removal of Dyes. Membranes 2025, 15, 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120384

Wang F, Hou X, He R, Song J, Xie Y, Yang Z, Liu X. Preparation of Cu-MnO2/GO/PVDF Catalytic Membranes via Phase Inversion Method and Application for Separation Removal of Dyes. Membranes. 2025; 15(12):384. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120384

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Fei, Xinyu Hou, Runze He, Jiachen Song, Yifan Xie, Zhaohui Yang, and Xiao Liu. 2025. "Preparation of Cu-MnO2/GO/PVDF Catalytic Membranes via Phase Inversion Method and Application for Separation Removal of Dyes" Membranes 15, no. 12: 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120384

APA StyleWang, F., Hou, X., He, R., Song, J., Xie, Y., Yang, Z., & Liu, X. (2025). Preparation of Cu-MnO2/GO/PVDF Catalytic Membranes via Phase Inversion Method and Application for Separation Removal of Dyes. Membranes, 15(12), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/membranes15120384