Abstract

The separator is a key component of lithium-ion batteries, and its properties play a crucial role in the performance of such batteries. However, the most widely used polyolefin separators are not only made from non-renewable resources such as petroleum, but also have poor wettability to electrolytes, and their low melting points may cause short circuits or even explosions. Therefore, advanced separators that meet the increasing requirements of such batteries are urgently needed. Compared to polyolefin separators, renewable biomass fiber-based separators have better compatibility with electrolytes, higher thermal stability, and are naturally abundant. Their use is not only in line with sustainable development, but it also lowers their material cost. Therefore, biomass fiber-based separators are considered a promising candidate for replacing polyolefin separators for lithium-ion batteries in the future. In this article, studies on the preparation and application of biomass fiber-based separators in lithium-ion batteries in recent years are reviewed, looking forward to their future development, with the aim of providing a reference for researchers.

1. Introduction

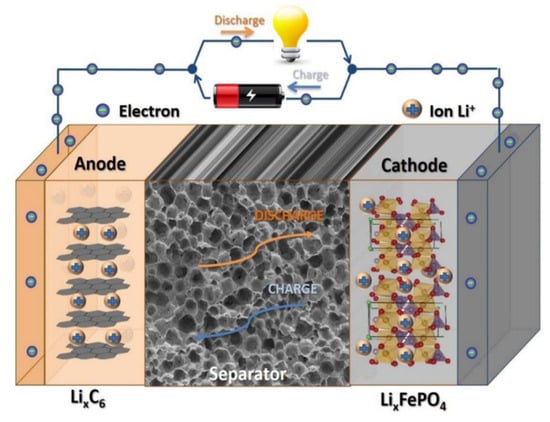

Lithium-ion batteries have become ideal energy storage devices due to their high specific energy, high power, excellent charge and discharge cycling capabilities, and environmental friendliness [,,]. Recently, they have been widely applied in portable electronic devices such as computers and cameras, as well as in large medical, automotive, and aerospace devices, and in other fields [,]. They are composed of mainly five parts: a positive electrode, a separator, a negative electrode, an electrolyte, and a battery shell []. The separator in lithium-ion batteries is a permeable membrane that physically isolates the positive and negative electrodes [,]. Its main function is to prevent short circuits caused by contact between the positive and negative electrodes, while allowing lithium ions to pass through and form ion currents, as shown in Figure 1 []. Therefore, the separator plays a crucial role in liquid electrolyte batteries [,,]. Its electrolyte wettability guarantees efficient electrochemical reactions in lithium-ion batteries, and its pore structure (related to the transport rate of lithium ions), heat-resistant quality, and mechanical strength also significantly affect the energy density, safety, and lifespan of lithium-ion batteries [,]. However, the most widely used polyolefin (polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), and their copolymers) separators have inherent hydrophobicity and relatively poor porosity, which has raised serious concerns over the insufficient wettability of the electrolyte, and their low melting points may cause short circuits or even explosions in lithium-ion batteries [,]. In addition, polyolefin separators are made from non-renewable resources such as petroleum, which are unsustainable and non-biodegradable [,,]. Therefore, developing more advanced separators has become an urgent requirement for the development of high-performance lithium-ion batteries [,,].

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the main components of a lithium-ion battery [].

In recent years, widely sourced and renewable biomass fiber-based separators have attracted people’s attention and quickly become a research hotspot [,,]. So far, a variety of biomass fiber-based separators, including pure biomass fiber-based separators and biomass fiber-based composite separators, e.g., cellulose/silica (SiO2), cellulose/polydopamine, cellulose/polysulfonamide, lignocellulose/polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), and polyformaldehyde/cellulose nanofibers (POM/CNF), have been fabricated and employed in lithium-ion batteries [,,,,,,,,,]. In comparison with traditional polyolefin separators, biomass fiber-based separators exhibit remarkably improved electrolyte absorption, heat resistance, and electrochemical properties, especially under high-temperature conditions [,,,,,,,,,]. Meanwhile, several approaches for manufacturing biomass fiber-based separators have been proposed and studied, such as electrospinning, forcespinning, vacuum filtration, spray deposition, and papermaking [,,,,,,]. However, the immature large-scale production, such as the time-consuming process, still limits the practical application of biomass fiber-based separators [,,]. In this article, the preparation and application of biomass microfiber-based separators, biomass nanofiber-based separators, and composite separators prepared by combining traditional polyolefin with biomass fibers in lithium-ion batteries are reviewed, with the aim of providing a reference for researchers.

2. Source and Characteristics of Biomass Fiber-Based Separators

Biomass fibers come from a variety of organisms such as plants (wood, bamboo, cotton, linen, etc.), animals (shrimp shells, crab shells, etc.), microorganisms (bacteria, fungi, etc.), and algae []. As the most widely available raw material for biomass fibers, cellulose accounts for (percent by weight) approximately 33% in vegetables, 40% to 50% in wood, and as high as 90% in cotton fibers. According to a rough estimate, cellulose represents an annual output of 150 billion tons of biomass, which makes biomass fibers a vast repository of renewable resources []. Compared to traditional commercial polyolefin separators, biomass fiber-based separators have several advantages [,,,,]: (i) Biomass fiber-based separators have high porosity and are easily functionalized, providing tailored functionalities for the resulting compounds. (ii) Due to their hydrophilicity, the compatibility between biomass fiber-based separators and electrolytes is stronger, which is beneficial for electrolyte absorption in separators, enhancing the transmission efficiency of lithium ions and reducing the internal resistance in lithium-ion batteries. (iii) Biomass fiber-based separators have high thermal resistance up to 200 °C, while commercial polyolefin separators undergo thermal shrinkage above 90 °C and gradually melt above 150 °C. (iv) Unlike polyolefin substances produced from finite fossil oil, biomass cellulose is naturally abundant, biodegradable, and renewable. This is not only in line with the sustainable development of the environment but also greatly reduces the material cost of separators. Therefore, biomass fiber-based separators have high potential to replace polyolefin separators in lithium-ion batteries in the future.

3. Preparation and Application of Biomass Fiber-Based Separators

3.1. Biomass Microfiber-Based Separators

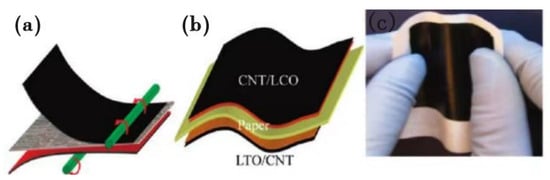

Biomass microfibers are one of the most important components of plants; they are also widely available and renewable. In recent years, researchers have applied low-cost biomass microfibers to lithium-ion battery separators. Cui et al. [] used commercial photocopy paper (Xerox paper) as both the separator and mechanical substrate, and integrated all components of a lithium-ion battery through a simple lamination process onto this paper, creating a lithium-ion paper battery. In it, independent carbon nanotube thin films with high conductivity were employed as current collectors for both the anode and cathode, which showed a sheet resistance as low as ~5 Ω·m−2. Moreover, although this lithium-ion paper battery was thin (thickness: ~300 μm), it showed strong mechanical flexibility (bending capacity: less than 6 mm), as demonstrated in Figure 2. Furthermore, the battery could achieve a high energy density of 108 mAh·g−1. The accelerated development of flexible electronic devices has put forward higher requirements for lithium-ion batteries, requiring them to be not only safe but also flexible to adapt to integrated flexible electronic devices. Therefore, this lamination, through which all components are integrated into a lithium-ion paper battery, offers a new design concept for the manufacturing of flexible electronic devices.

Figure 2.

(a) Schematic diagram of the lamination process. (b) Schematic diagram of the lithium-ion paper battery structure. (c) Photograph of the lithium-ion paper battery before packaging [].

Chen et al. [] first used commercial rice paper (RP) as a separator for lithium-ion batteries. This separator is composed of cross-linked cellulose fibers with diameters ranging from 5 to 40 μm and its structure has a high porosity. This separator exhibits satisfactory electrochemical stability at a voltage of 4.5 V (vs. Li+/Li, measured in Li/RP/stainless-steel cells with 1 M LiPF6 in an ethylene carbonate/ethylene carbonate electrolyte) and shows good compatibility with electrodes such as graphite, LiFePO4, LiCoO2, and LiMn2O4. Compared with commercial PP/PE/PP separators, the RP separator has lower resistance under the same thickness conditions, which could be attributed to its highly porous structure. In addition, with its good flexibility, excellent electrochemical performance, and low cost, this RP separator is expected to partially replace the commercial separators currently used in low-power lithium-ion batteries.

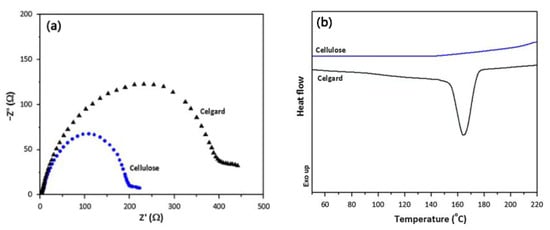

Using commercial paper as the separator can successfully lead to lithium-ion batteries with excellent mechanical flexibility. This paper separator is lightweight and low-cost, but its thickness is high (Table 1), which is not conducive to reducing the internal resistance of lithium-ion batteries and increasing their energy density. A comparison of the properties of the various separators mentioned is shown in Table 1. To reduce the thickness of this separator and improve its pore structure, Alcoutlabi et al. [] prepared a fibrous cellulose membrane via forcespinning using cellulose acetate as the raw material. When used as the separator for lithium-ion batteries, this membrane exhibits a three-dimensional network structure with a porosity of up to 76%, in which the cellulose fibers are randomly oriented and fully interconnected. This structure can not only enhance the electrolyte wettability and absorption capacity of the separator but also reduce the interface resistance between the separator and the electrode. Therefore, compared with commercially available PP separators, the fibrous cellulose membrane separator exhibits higher ion conductivity (2.12 × 10−3 S·cm−1), lower interfacial resistance (Figure 3a), and superior thermal stability, as can be seen from the differential scanning calorimetry results (Figure 3b). These advantages mean that a fibrous cellulose membrane can be used as the separator in high-performance lithium-ion batteries.

Table 1.

The characteristics of the various separators mentioned in the manuscript.

Figure 3.

Electrochemical impedance spectra (a) and differential scanning calorimetry curves (b) of fibrous cellulose membrane and commercial PP separator [].

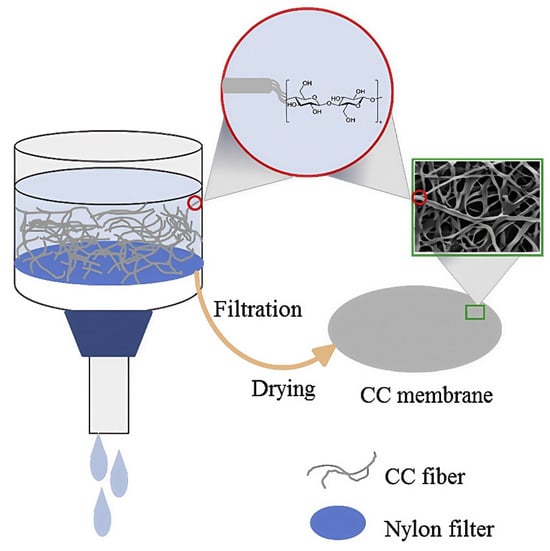

In addition to their usual thickness of over 60 μm, biomass microfibers have drawbacks such as large pore size and low mechanical strength, which can make it easier for the lithium dendrites to pierce the separator and cause battery short circuits []. To solve this problem, PAN et al. [] prepared a lithium-ion battery separator using Cladophora cellulose (CC) as the raw material and adopted a process similar to that of papermaking, featuring vacuum filtration, as shown in Figure 4. The mesoporous CC separator has a thickness of ~35 μm and an average pore size of ~20 nm. Meanwhile, its Young’s modulus can reach up to 5.9 GPa. The decrease in separator thickness can reduce its volume resistance, and the nanoscale pore size provides it with high porosity. The excellent pore structure of the CC separator may be attributed to the high crystallinity of CC, which makes this type of separator less prone to aggregation when dried. Therefore, a LiFePO4/Li battery using the CC separator exhibits excellent cycling stability. After 50 cycles at a current density of 0.2 C, its discharge capacity retention rate can reach 99.5%.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the preparation process of the Cladophora cellulose separator [].

Although multiple measures have been taken to address the issues of large pore size and low mechanical strength in cellulose microfiber-based separators, there is still a significant gap between them and current commercial separators. The surface of cellulose microfibers is rich in hydroxyl groups, which makes the separator highly flammable and hygroscopic. In recent years, various biomass microfiber-based composite separators have been prepared by combining biomass microfibers with functional substances. Compared to pure biomass microfiber-based separators, these composite separators have shown significantly superior electrochemical properties and safety performance [,,].

3.2. Biomass Microfiber-Based Composite Separators

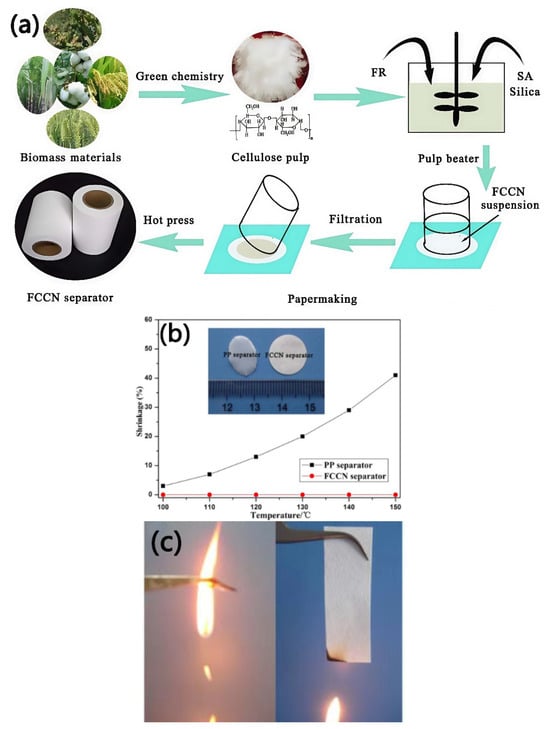

Cui et al. [] first fabricated a cellulose-based composite nonwoven separator (FCCN separator) using cellulose fibers and flame retardants as raw materials, as shown in Figure 5. In comparison with commercial PP separators, the FCCN separator exhibits better rate performance, which could be ascribed to its interconnected pore spaces and hydrophilic properties, resulting in high electrolyte absorption and ion conductivity. In addition, the FCCN separator also exhibits superior thermal stability, which may be due to the outstanding heat resistance of cellulose. When used for a LiFePO4/Li half-cell at a high temperature of 120 °C, the FCCN separator exhibits excellent cycling performance, while the PP separator is almost unable to charge and discharge normally. Furthermore, the higher limiting oxygen index (LOI) value of the FCCN separator indicates its superior flame-retardant properties compared to the PP separator. Good heat resistance and flame retardancy help enhance the safety of lithium-ion batteries, while the simple papermaking process enables the large-scale production and application of this composite separator.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the manufacturing process of the FCCN separator (a). Thermal shrinkage rate (b) (the inserted photograph shows the two separators after being heated at 150 °C for 0.5 h) and combustion behavior (c) of the PP separator and FCCN separator [].

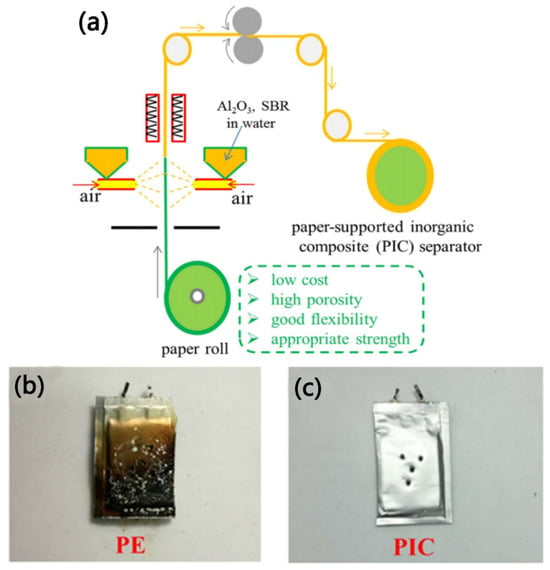

Wang et al. [] prepared a paper-based inorganic composite separator (PIC separator) by spraying Al2O3 particles onto the surface of commercial paper-based material, as shown in Figure 6a. Due to the interaction between the hydroxyl groups of the paper-based material and the polar groups of Al2O3, the adhesion between the paper-based material and Al2O3 is enhanced, thereby ensuring the structural stability of the PIC separator. Compared with traditional PE separators (43%), the PIC separator has better porosity (56%). This could be due to the fact that after spraying Al2O3 particles, the large pores of the paper-based structure are partially covered and transformed into mesopores or micropores, thereby improving their absorption of electrolytes and reducing the self-discharge of lithium-ion batteries. Moreover, in the nail penetration experiment of batteries, as shown in Figure 6b,c, when the nail penetrated the bag battery featuring the PIC separator, no smoke or combustion was observed, while when the bag battery containing the PE separator was penetrated by the nail, a burning phenomenon was observed on the surface. This could be attributed to the better thermal stability of the cellulose fibers and the Al2O3 coating, which contribute to the PIC separator’s satisfactory safety performance for use in lithium-ion batteries.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of the preparation process of the PIC separator (a). The nail penetration test results of pouch cells with different separators (the PE separator (b) and the PIC separator (c), respectively) [].

3.3. Biomass Nanofiber-Based Separators

Although there have been reports of biomass microfiber-based separators used as lithium-ion battery separators [,,], their pore structure and mechanical properties still have inherent defects which limit their practical applications. Compared with biomass microfibers, biomass nanofibers with a nanometer-scale diameter (cellulose acetate membrane (fiber diameter: 1.18 μm) [] vs. CNFs (fiber diameter: <50 nm) []) and a micrometer-scale length, as well as better mechanical properties and thermal stability, are more suitable for use as separators in lithium-ion batteries [,]. Among them, the nanometer-scale diameter is a key factor in controlling the pore structure of the separators.

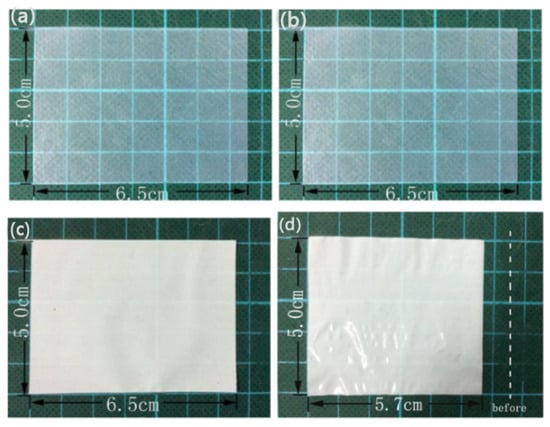

Lee et al. [] first employed a simple self-assembly method to transform a cellulose nanofiber (CNF) suspension into cellulose nanofiber paper. The obtained cellulose nanofiber paper has a unique pore structure, and it can also be adjusted by changing the proportion of different solvents (isopropanol/water) in the CNF suspension, ultimately forming abundant network channels and displaying excellent mechanical strength. However, relying solely on adjusting the solvents is not sufficient to control the pore structure of the separator properly. Jiang et al. [] used a bacterial cellulose (BC) nanofiber separator in a lithium-ion battery. Unlike ordinary cellulose, BC fibers have an average diameter of less than 100 nm and can form a porous three-dimensional structure through mutual cross-linking and overlapping, which enables the BC separator to have good electrolyte wettability. In addition, compared with commercial Celgard® separators, the BC separator has outstanding thermal stability. After heat treatment at 100 °C for 12 h, the BC separator showed almost no thermal shrinkage, while the commercial Celgard® separator rapidly contracted in the first 10 min, as shown in Figure 7. Even after heat treatment at a high temperature of 180 °C for 3 h, the BC separator maintained good structural stability, while the Celgard® separator rapidly melted at 165 °C. However, despite its many advantages, the ion conductivity of the BC separator is not satisfactory and further improvements are still needed to enhance this characteristic.

Figure 7.

Photographs of BC separators (a,b) and Celgard® separators (c,d) before (a,c) and after (b,d) annealing at 100 °C for 12 h [].

In order to improve the pore structure of BC separator, Xu et al. [] prepared a 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO)-oxidized bacterial cellulose (TOBC) separator by first converting the BC separator into a BC suspension using 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpylperidine-l-oxyl radial (TEMPO)-mediated oxidation, followed by vacuum filtration. The TOBC separator is composed of fibers with an average diameter of ~48 nm, which can be attributed to the change in the chemical structure of BC fibers caused by TEMPO oxidation. The mutual repulsion between aldehyde and aldehyde groups in the BC fibers enhances their dispersibility in water, thereby improving the uniformity of pore size distribution of the TOBC separator after drying. The TOBC separator has high porosity (91.1%), a good electrolyte absorption capacity (339%), low interface resistance with a lithium electrode (96 Ω), and an ion conductivity up to 13.45 mS·cm−1. When the TOBC separator is used for Li/LiFePO4 half-cells, the discharge specific capacity of the battery can reach 166 mAh·g−1 at a current density of 0.2 C, and the capacity retention rate achieves 94% after 100 cycles.

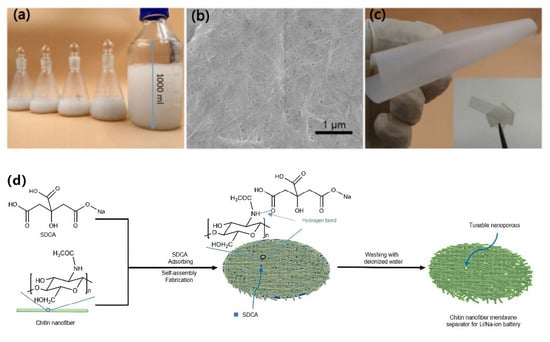

In addition to the oxidation method, the template method is also an effective way to create pores during the production of a separator. Yu et al. [] prepared porous chitosan nanofiber membrane (CNM) separators using sodium dihydrogen citrate (SDCA) as a template, as shown in Figure 8. The hydroxyl groups of SDCA can form hydrogen bonds with the functional groups of chitosan nanofibers, allowing SDCA to be uniformly adsorbed on the surface of chitosan nanofibers. During solvent evaporation, SDCA plays a role in preventing the tight packing of chitosan nanofibers. After removal of SDCA via washing, a porous CNM separator is obtained, and its pore structure can be regulated by changing the mass ratio of SDCA to chitin nanofibers. The electrochemical performance of the prepared Chitin/SDCA-40% separator at room temperature is comparable to that of a commercial PP separator. However, under a high-temperature condition of 120 °C, it exhibits a significantly superior electrochemical performance.

Figure 8.

(a) Photograph of chitin nanofiber suspension. (b) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of chitin nanofibers. (c) Photograph of CNM obtained from chitin nanofiber suspension by vacuum drying. (d) Schematic diagram of manufacturing process of CNM separator using SDCA [].

3.4. Biomass Nanofiber-Based Composite Separators

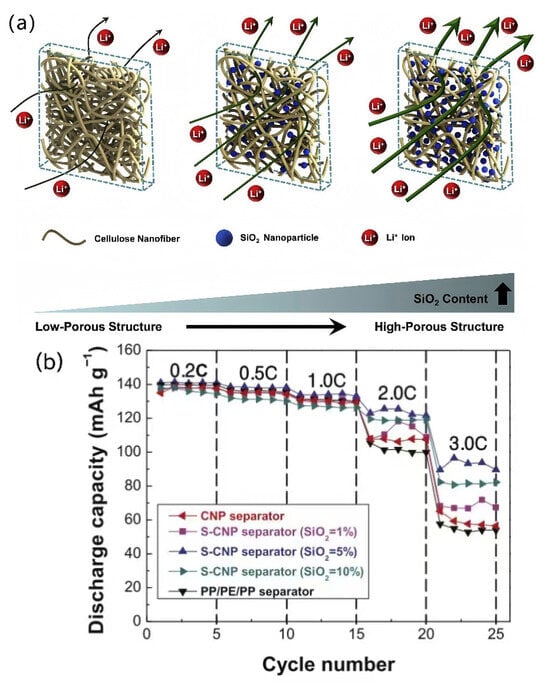

Compared to biomass nanofiber-based separators, biomass nanofiber-based composite separators exhibit superior performance, such as superior porosity and liquid absorption, and have become an important development direction [,,]. Lee et al. [] added colloidal SiO2 nanoparticles, a pore-forming agent, to a cellulose nanofiber (CNF) suspension and synthesized a SiO2-containing cellulose nanofiber paper separator (S-CNP separator) by vacuum filtration. SiO2 nanoparticles can prevent tight packing between nanofibers during solvent evaporation, thus effectively improving the porosity of the cellulose nanofiber-based separator. More importantly, the pore structure of the prepared S-CNP separator can be adjusted according to the SiO2 content in the suspension, as shown in Figure 9. The experimental results showed that the S-CNP separator containing 5 wt.% SiO2 exhibited the best ion conductivity and electrochemical performance, and its rate performance was better than those of the CNP separator without SiO2 and traditional commercial separators.

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic diagram of S-CNP separator and influence of SiO2 nanoparticles on its ionic transport. (b) Rate performance of various S-CNP separators and other separators [].

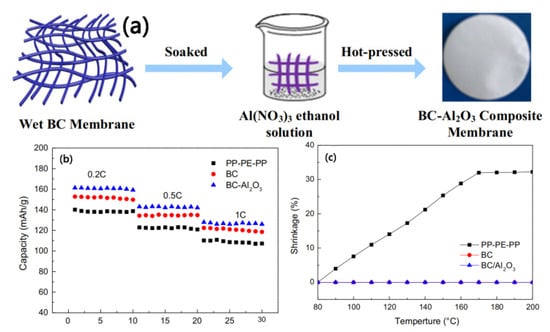

Although the S-CNP separator prepared by Lee et al. has excellent electrochemical performance, its complex preparation method is not conducive to large-scale production. In view of this, Xu et al. [] prepared BC/Al2O3 nanofiber composite separators using a simple in situ pyrolysis method, as shown in Figure 10a. In high-temperature air, the Al(NO3)3 coated on the surface of BC decomposes and releases NO2 and O2 molecules, and the formed Al2O3 can be covalently connected to BC fibers. The Al2O3 on the surface of BC fibers helps to improve the dispersion of BC fibers, thereby increasing the porosity of the prepared separator. The test results show that the BC/Al2O3 composite separator has high porosity (74.7%), excellent electrolyte absorption (625%), and outstanding ion conductivity (4.91 mS·cm−1). Compared with the BC separator and a commercial PP-PE-PP separator, the BC/Al2O3 composite separator exhibits superior rate performance in batteries, as shown in Figure 10b. It is particularly noteworthy from Figure 10c that the BC/Al2O3 composite separator possesses remarkable thermal stability at a high temperature of 200 °C, while the commercial PP-PE-PP separator shows significant thermal shrinkage under the same conditions.

Figure 10.

(a) Schematic diagram of manufacturing process of BC-Al2O3 composite separator. (b) Rate performance of different separators. (c) Thermal shrinkage behavior of different separators at different temperatures for 30 min [].

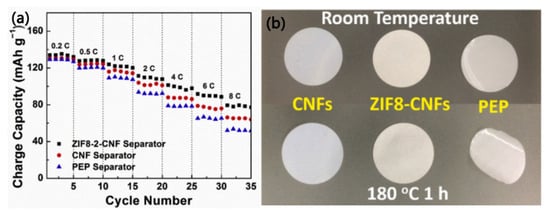

Wu et al. [] first introduced zeolitic imidazolate framework-8 (ZIF-8) into the separator of lithium-ion batteries. A ZIF-8-CNF composite separator was fabricated by synthesizing ZIF-8 crystals on the surface of cellulose nanofibers (CNFs), which helps to prevent CNF aggregation and thereby improves their pore size uniformity and electrolyte wettability. Compared to the pure CNF separator (porosity: 42%), the porosity of the ZIF8-2-CNF (ZIF8:CNF ratio: 0.6:1) separator can be increased to 55%. Moreover, compared with the pure CNF separator and a commercial PEP separator, the ZIF8-2-CNF separator shows superior electrochemical performance in batteries and better thermal stability under a high temperature condition of 180 °C, as can be seen in Figure 11a,b, respectively. It is worth noting that in lithium-ion batteries, no obvious decomposition of the main components was observed for the ZIF8-2-CNF and CNF separators before 4.4 V, comparable to the commercial PEP separator.

Figure 11.

(a) Rate performance of lithium-ion batteries with different separators. (b) Thermal shrinkage behavior of different separators at 180 °C for 1 h [].

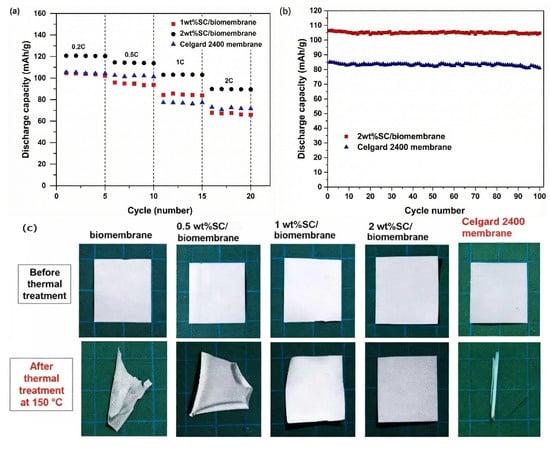

As is well known, the thermal stability of the separator plays a decisive role in the high-temperature performance of the battery. Manuspiya et al. [] used sulfonated cellulose (SC) and poly(lactic acid)/poly(butylene succinate) (PLA/PBS) composites to prepare SC/biomembranes by a phase inversion method. The test results revealed that the 2 wt% SC/biomembrane exhibited the best electrochemical performance. Its porosity was estimated to be 87.7%, significantly higher than that (42.1%) of the commercial Celgard 2400 membrane, which resulted in its better electrolyte uptake and lower interfacial resistance with electrodes. When used as a separator in a LiCoO2/graphite battery, a discharge specific capacity of 106 mAh·g−1 was delivered by the battery assembled with the 2 wt% SC/biomembrane after 100 cycles at 1 C, while the battery with the Celgard 2400 membrane displayed a capacity of only 81 mAh·g−1, as shown in Figure 12a,b. In addition, the 2 wt% SC/biomembrane has superior thermal stability, with almost no thermal shrinkage at a high temperature of 150 °C, while the Celgard 2400 membrane exhibited significant severe deformation, as seen in Figure 12c. Therefore, the 2 wt% SC/biomembrane is more promising for use as a separator in high-safety lithium-ion batteries.

Figure 12.

(a) Rate performance of lithium-ion batteries with different separators. (b) Cycling performance of lithium-ion batteries with different separators at 1 C. (c) Thermal shrinkage behavior of different separators after heat treatment at 150 °C [].

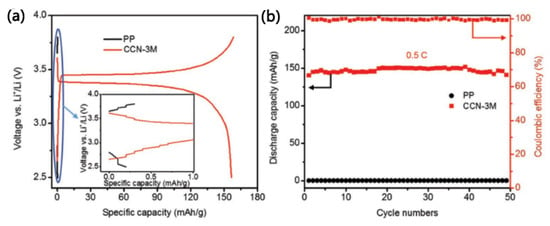

Yao et al. [] used natural polymer nanofibers (chitosan nanofibers) as raw materials and chemically modified them by grafting cyanoethyl groups onto their surfaces to obtain a dense chitin nanofiber-based separator (CCN separator). The CCN separator possesses an extremely high tensile strength (120 MPa), far exceeding the porous chitosan nanofiber-based separator (80 MPa) previously reported. Moreover, the grafting of cyanoethyl groups gives CCN separators high ion conductivity (0.45 mS·cm−1), which is approximately 13 times that of the unmodified chitosan nanofiber-based separators (0.035 mS·cm−1). Furthermore, the excellent thermal stability of CCN separators enables LiFePO4/Li batteries to operate at 120 °C, which is not achievable with commercial polyolefin separators, as shown in Figure 13. The chemical modification method for chitosan nanofibers presented in this study could provide inspiration for the preparation of other natural polymer fiber-based composite separators.

Figure 13.

(a) The charge–discharge voltage profiles of LiFePO4/Li half-cells with different separators at 0.5 C (120 °C). The figure insert shows the failure of the cell with the PP separator. (b) Cycling ability of the cells with different separators at 0.5 C (120 °C) [].

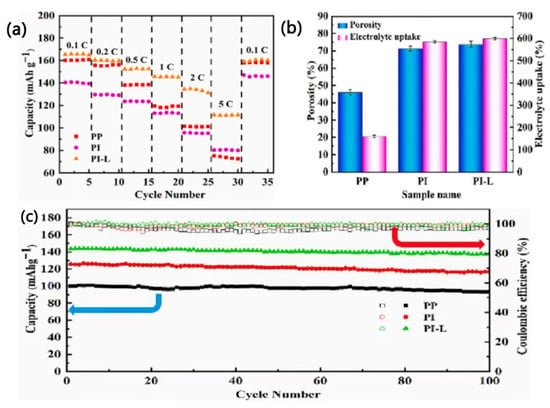

Wang et al. [] prepared a new biomass nanofiber separator (PI-L separator) by using polyimide (PI) and lignin (L) as raw materials through simple physical mixing and electrospinning techniques. In addition to the excellent thermal stability of the PI-L separator (above 450 °C), the polar groups of lignin can also enhance the affinity between the PI-L separator and the electrolyte, thereby increasing the electrolyte absorption of the PI-L separator (592%) (Figure 14b). The PI-L separator thus exhibits high ion conductivity (1.78 × 10−3 S·cm−1) and lithium ion mobility (0.787). Additionally, due to the introduction of lignin, the cycling and rate performance of the battery are improved, as shown in Figure 14a. After 100 cycles at the 1 C rate, the capacity retention rate of the LiFePO4|PI-L|Li battery reaches 95.1%, which is clearly higher than those of PI separators and current commercial PP separators (90%) (Figure 14c). Moreover, the SEM results indicate that lignin can inhibit the formation of lithium dendrites and generate a stable solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) film, which helps to enhance the safety of the PI-L separator [].

Figure 14.

(a) Rate performance of batteries with different separators at room temperature. (b) Porosity and electrolyte uptake of different separators. (c) Cycling performance of batteries with different separators at 1 C [].

4. Summary

In recent years, great progress has been made in the application of biomass fiber-based separators in lithium-ion batteries due to their excellent electrolyte compatibility, thermal stability, abundant reserves, and environmental sustainability. As well as summarizing the advantages of biomass fiber-based separators, their shortcomings, such as pore structure, mechanical properties, and industrialization issues, are also pointed out in this review. This review will be beneficial for researchers, providing a reference for urgent issues to start from when preparing suitable separators for high-performance lithium-ion batteries.

- (i)

- In the battery industry, to prevent lithium dendrites from piercing the separator, the pore size of the separator should generally be less than 1 µm. Therefore, the pore structure of the separator must be practical: the pore size needs to be controlled at the nanometer level and the pore size distribution needs to be uniform, as this is beneficial for the rapid migration of lithium ions within the separator.

- (ii)

- Appropriate modification of biomass fibers can improve their physicochemical properties, allowing researchers to fully utilize the advantages of biomass fiber-based separators while avoiding the impact of their disadvantages. Especially for synthesizing biomass fiber-based composite separators, the addition of other substances can effectively alleviate fiber aggregation and then improve the electrolyte absorption and mechanical strength of the separators.

- (iii)

- The mass production of biomass fiber-based separators for lithium-ion batteries has not yet been achieved. This indicates that their preparation process and production equipment do not currently meet the requirements for large-scale production. Therefore, research efforts can be increased in these two areas, for example, to improve textile and surface coating technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.C. and C.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, C.C.; writing—review and editing, B.L.; visualization, B.L.; supervision, C.Z.; project administration, C.Z.; funding acquisition, C.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a school–enterprise cooperation project, grant number 118-08024340.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the School of Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, Wuhan Polytechnic University, Wuhan 430023, China.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, D.; Zhou, Z.; Feng, C.; Lv, W.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, K.H.L.; Lin, B.; Wu, S.; Lei, T.; Guo, X.; et al. An Upgraded Lithium Ion Battery Based on a Polymeric Separator Incorporated with Anode Active Materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1803627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Shen, J.; Wang, T.; Dai, M.; Si, C.; Xie, J.; Li, M.; Cong, X.; Sun, X. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-67 based separator for enhanced high thermal stability of lithium ion battery. J. Power Sources 2018, 400, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Ye, P.; Zheng, M.; Zhou, N.; Wang, D. Template-free synthesis of biomass-derived carbon coated Li4Ti5O12 microspheres as high performance anodes for lithium-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 459, 572–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Chen, Y.; Ma, W.; Zhang, S. A High Performance Polyacrylonitrile Composite Separator with Cellulose Acetate and Nano-Hydroxyapatite for Lithium-Ion Batteries. Membranes 2022, 12, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Qiu, L.; Ma, X.; Dong, L.; Jin, Z.; Xia, G.; Du, P.; Xiong, J. Electrospun cellulose polymer nanofiber membrane with flame resistance properties for lithium-ion batteries. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 234, 115907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shen, L.; Shen, J.; Liu, F.; Chen, G.; Tao, R.; Ma, S.; Peng, Y.; Lu, Y. Anion-Sorbent Composite Separators for High-Rate Lithium-Ion Batteries. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1808338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croguennec, L.; Palacin, M.R. Recent Achievements on Inorganic Electrode Materials for Lithium-Ion Batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 3140–3156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, D.; Yang, L.; Zheng, S.; Niu, J.; Sun, Z.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Li, B. Modified alginate dressing with high thermal stability as a new separator for Li-ion batteries. Chem. Commun. 2020, 56, 6149–6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.M.; Lee, Y.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Recent advances on separator membranes for lithium-ion battery applications: From porous membranes to solid electrolytes. Energy Storage Mater. 2019, 22, 346–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhang, X.; Wen, J.; Wang, C.; Ma, X.; Yang, Y.; Huang, G.; Ye, H.-M.; Xu, S. Research progress on high-temperature resistant polymer separators for lithium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2022, 51, 638–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raja, M.W.; Basu, R.N.; Pramanik, N.C.; Das, P.S.; Das, M. Paperator: The Paper-Based Ceramic Separator for Lithium-Ion Batteries and the Process Scale-Up Strategy. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 5841–5854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.; Wang, Y.; Cai, C.; Wei, Z.; Fu, Y. 3D-cellulose acetate-derived hierarchical network with controllable nanopores for superior Li+ transference number, mechanical strength and dendrites hindrance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 274, 118620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Guccini, V.; Lu, H.; Salazar-Alvarez, G.; Lindbergh, G.; Cornell, A. Lithium Ion Battery Separators Based On Carboxylated Cellulose Nanofibers From Wood. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2018, 2, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhang, M.; Xu, T.; Liu, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Yuan, Z.; Si, C. Nanocellulose/metal-organic frameworks composites for advanced energy storage of electrodes and separators. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 500, 157318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Liang, J.; Chen, Q.; Huang, J. Environmentally friendly separators based on cellulose diacetate-based crosslinked networks for lithium-ion batteries. Polymer 2024, 290, 126564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andonegi, M.; Serra, J.P.; Silva, M.M.; Gonçalves, R.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Mendez, S.; de la Caba, K.; Guerrero, P. Lithium-ion battery separators based on sustainable collagen and chitosan hybrid membranes. Electrochim. Acta 2025, 526, 146087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhiman, N.; Sharma, V.; Ghosh, S. Perspective on Biomass-Based Cotton-Derived Nanocarbon for Multifunctional Energy Storage and Harvesting Applications. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 1970–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Zhu, W.; Tang, Q.; Huang, Z.; Yu, P.; Gui, X.; Lin, S.; Hu, J.; Tu, Y. Mini Review on Cellulose-Based Composite Separators for Lithium-Ion Batteries: Recent Progress and Perspectives. Energy Fuels 2021, 35, 12938–12947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.A.; Ong, H.L.; Villagracia, A.R.; Halim, K.A.A.; Ganganboina, A.B.; Doong, R.-A. Biomass–derived cellulose nanofibrils membrane from rice straw as sustainable separator for high performance supercapacitor. Ind. Crops Prod. 2021, 170, 113694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Cai, S.; Gao, H.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y. Cellulose-based separators for lithium batteries: Source, preparation and performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Liu, W.; Liao, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zeng, G. Pure cellulose nanofiber separator with high ionic conductivity and cycling stability for lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 250, 126078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, N.; Lv, T.; Chen, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dong, K.; Cao, S.; Chen, T. Natural wood-derived free-standing films as efficient and stable separators for high-performance lithium ion batteries. Nanoscale Adv. 2022, 4, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rehman, W.U.; Ma, Y.; Khan, Z.; Laaskri, F.Z.A.; Xu, J.; Farooq, U.; Ghani, A.; Rehman, H.; Xu, Y. Biomass-derived carbon materials for batteries: Navigating challenges, structural diversities, and future perspective. Next Mater. 2025, 7, 1718–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Yao, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, M.; Hong, W. Advances in biomass-based nanofibers prepared by electrospinning for energy storage devices. Fuel 2024, 355, 129534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Li, K.; Ran, T.; Ruan, S.; Yang, X.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H. Cellulose-based membrane with ion regulating function for high-safety lithium-ion battery at low temperature enabled by grafting structural engineering. J. Membr. Sci. 2025, 727, 124093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Shi, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yang, H.; Mao, X.; Chi, M.; Sun, L.; Yuan, S. Porous cellulose diacetate-SiO2 composite coating on polyethylene separator for high-performance lithium-ion battery. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 147, 517–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Kong, Q.; Zhang, C.; Pang, S.; Yue, L.; Wang, X.; Yao, J.; Cui, G. Renewable and Superior Thermal-Resistant Cellulose-Based Composite Nonwoven as Lithium-Ion Battery Separator. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2012, 5, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Yue, L.; Cui, G. Polydopamine-coated cellulose microfibrillated membrane as high performance lithium-ion battery separator†. RSC Adv. 2013, 4, 7845–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, J.; Yue, L.; Duan, Y.; Cui, G. Cellulose/Polysulfonamide Composite Membrane as a High Performance Lithium-Ion Battery Separator. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2013, 2, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, A.N.M.A.; Zhang, Y.; Naebe, M. A review on lignocellulose/poly (vinyl alcohol) composites: Cleaner approaches for greener materials. Cellulose 2021, 28, 10741–10764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, K.; Mo, Y.; Wang, S.; Han, D.; Xiao, M.; Meng, Y. Highly safe lithium-ion batteries: High strength separator from polyformaldehyde/cellulose nanofibers blend. J. Power Sources 2018, 400, 502–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Ayoub Arbab, A.; Jatoi, A.W.; Khatri, M.; Memon, N.; Khatri, Z.; Kim, I.S. Ultrasonic-assisted deacetylation of cellulose acetate nanofibers: A rapid method to produce cellulose nanofibers. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 36, 319–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.Y.; Li, M.X.; Chang, Z.; Wang, Y.F.; Gao, J.; Zhu, Y.S.; Wu, Y.P.; Huang, W. A Sandwich PVDF/HEC/PVDF Gel Polymer Electrolyte for Lithium Ion Battery. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 245, 752–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, X.; Huang, Y.; Song, A.; Liu, B.; Yin, Z.; Wu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, X.; Cao, H. Gel polymer electrolyte with high performances based on biodegradable polymer polyvinyl alcohol composite lignocellulose. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2019, 229, 232–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, X.; Wu, J.; Ma, X.; Deng, X.; Cai, J.; Chen, Q.; Liu, J.; Nan, J. A poly(vinylidene fluoride)/ethyl cellulose and amino-functionalized nano-SiO2 composite coated separator for 5 V high-voltage lithium-ion batteries with enhanced performance. J. Power Sources 2018, 407, 44–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, A.; Jiang, Z.; Li, S.; Du, J.; Tao, Y.; Lu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H. A degradable membrane based on lignin-containing cellulose for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 213, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, D.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Li, H. Recent progress of bacterial cellulose-based separator platform for lithium-ion and lithium-sulfur batteries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 133419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, J.P.; Uranga, J.; Gonçalves, R.; Costa, C.M.; de la Caba, K.; Guerrero, P.; Lanceros-Mendez, S. Sustainable lithium-ion battery separators based on cellulose and soy protein membranes. Electrochimica Acta 2023, 462, 142746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Zhao, G.; Zhang, S.; Xie, C.; Yang, R.; Li, X. Chitosan nanofiber paper used as separator for high performance and sustainable lithium-ion batteries. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 329, 121530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, Y.; Fang, L.; Shi, Z.; Xiong, C.; Yang, Q.; An, Q. High-performance cellulose aerogel membrane for lithium-ion battery separator. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 303, 140535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Zhong, X.; Xu, L.; Xiong, Y.; Deng, W.; Zou, G.; Hou, H.; Ji, X. Biomass-derived carbon dots: Synthesis, modification and application in batteries. Chem. Sci. 2025, 16, 4937–4970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Gu, M.; Lee, D.H.; Kim, J.-H.; Oh, Y.-S.; Min, S.H.; Kim, B.-S.; Lee, S.-Y. Functionalized Nanocellulose-Integrated Heterolayered Nanomats toward Smart Battery Separators. Nano Lett. 2016, 16, 5533–5541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Zhuang, J.; Wang, W.; Abbas, S.C.; Fu, C.; Zhang, H.; Chen, T.; Yuan, Y.; Zhao, X.; et al. Exploitation of function groups in cellulose materials for lithium-ion batteries applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2024, 325, 121570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Liang, Y. Preparation and characterization of a Lithium-ion battery separator from cellulose nanofibers. Heliyon 2015, 1, e00032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Dai, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, H.; Xie, L.; Chen, J.; Yan, C.; Yuan, H.; Wang, H.; Chen, C. Cellulose nanofiber separator for suppressing shuttle effect and Li dendrite formation in lithium-sulfur batteries. J. Energy Chem. 2022, 67, 736–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.Z.; Lina, Z. Recent advances in regenerated cellulose materials. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2016, 53, 169–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneventi, D.; Chaussy, D.; Curtil, D.; Zolin, L.; Bruno, E.; Bongiovanni, R.; Destro, M.; Gerbaldi, C.; Penazzi, N.; Tapin-Lingua, S. Pilot-scale elaboration of graphite/microfibrillated cellulose anodes for Li-ion batteries by spray deposition on a forming paper sheet. Chem. Eng. J. 2014, 243, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, F.; Xu, Y.; Peng, B.; Su, Y.; Jiang, F.; Hsieh, Y.-L.; Wei, Q. Coaxial Electrospun Cellulose-Core Fluoropolymer-Shell Fibrous Membrane from Recycled Cigarette Filter as Separator for High Performance Lithium-Ion Battery. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2015, 3, 932–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krol, L.F.; Beneventi, D.; Alloin, F.; Chaussy, D. Microfibrillated cellulose-SiO2 composite nanopapers produced by spray deposition. J. Mater. Sci. 2015, 50, 4095–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabbour, L.; Bongiovanni, R.; Chaussy, D.; Gerbaldi, C.; Beneventi, D. Cellulose-based Li-ion batteries: A review. Cellulose 2013, 20, 1523–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Liu, P.; Fu, Q.S.; Gong, Y.; Zhang, S.R.; He, H.J.; Chen, J. Study on preparation of polyacrylonitrile/polyimide composite lithium-ion battery separator by electrospinning. J. Mater. Res. 2019, 34, 642–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goikuria, U.; Larrañaga, A.; Vilas, J.L.; Lizundia, E. Thermal stability increase in metallic nanoparticles-loaded cellulose nanocrystal nanocomposites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 171, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lizundia, E.; Costa, C.M.; Alves, R.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Cellulose and its derivatives for lithium ion battery separators: A review on the processing methods and properties. Carbohydr. Polym. Technol. Appl. 2020, 1, 100001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, P.; Liu, K.; Wang, Z.; Shi, L.; Yuan, S. Multifunctional separators for high-performance lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2021, 499, 229973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Gu, J.; Pan, C.; Zhang, J.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y. Recent developments of composite separators based on high-performance fibers for lithium batteries. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2022, 162, 107132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.-W.; Tian, T.; Shen, B.; Song, Y.-H.; Yao, H.-B. Recent advances on biopolymer fiber based membranes for lithium-ion battery separators. Compos. Commun. 2019, 14, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, A.; Wanyan, H.; Lu, S.; Mosisa, M.T.; Zhou, X.; Xiao, H.; Liu, K.; Huang, L.; Chen, L.; Wu, H. A review on cellulose-based derivatives and composites for sustainable rechargeable batteries. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Q.; Luo, W.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H. Cellulose-based mesoporous membrane co-engineered with MOF for high-safety lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Lett. 2024, 360, 136000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Feng, Y.; Li, D.; Li, K.; Yan, Y. Towards the sustainable production of biomass-derived materials with smart functionality: A tutorial review. Green Chem. 2024, 26, 9075–9103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.-J.; Alaboina, P.K.; Zhang, L.; Cho, S.-J. A low-cost, environment-friendly lignin-polyvinyl alcohol nanofiber separator using a water-based method for safer and faster lithium-ion batteries. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 2017, 223, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Wu, H.; La Mantia, F.; Yang, Y.; Cui, Y. Thin, Flexible Secondary Li-Ion Paper Batteries. ACS Nano 2010, 4, 5843–5848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.C.; Sun, X.; Hu, Z.; Yuan, C.C.; Chen, C.H. Rice paper as a separator membrane in lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2012, 204, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, B.; Xu, F.; Alcoutlabi, M.; Mao, Y.; Lozano, K. Fibrous cellulose membrane mass produced via forcespinning® for lithium-ion battery separators. Cellulose 2015, 22, 1311–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Cheung, O.; Wang, Z.; Tammela, P.; Huo, J.; Lindh, J.; Edström, K.; Strømme, M.; Nyholm, L. Mesoporous Cladophora cellulose separators for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2016, 321, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yue, L.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Q.; Zhang, B.; Ding, G.; Qin, B.; et al. Sustainable, heat-resistant and flame-retardant cellulose-based composite separator for high-performance lithium ion battery. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 3935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiang, H.; Wang, L.; Xia, R.; Nie, S.; Chen, C.; Wang, H. A paper-supported inorganic composite separator for high-safety lithium-ion batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2018, 553, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F.; Yin, L.; Yu, Q.; Zhong, C.; Zhang, J. Bacterial cellulose nanofibrous membrane as thermal stable separator for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2015, 279, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Ji, H.; Yang, Y.; Guo, B.; Luo, L.; Meng, Z.; Fan, L.; Xu, J. TEMPO-oxidized bacterial cellulose nanofiber membranes as high-performance separators for lithium-ion batteries. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 230, 115570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Shen, B.; Yao, H.B.; Ma, T.; Yu, S.H. Prawn Shell Derived Chitin Nanofiber Membranes as Advanced Sustainable Separators for Li/Na-Ion Batteries. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 4894–4901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-H.; Kim, J.-H.; Choi, E.-S.; Yu, H.K.; Kim, J.H.; Wu, Q.; Chun, S.-J.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-Y. Colloidal silica nanoparticle-assisted structural control of cellulose nanofiber paper separators for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 2013, 242, 533–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Wei, C.; Fan, L.; Peng, S.; Xu, W.; Xu, J. A bacterial cellulose/Al2O3 nanofibrous composite membrane for a lithium-ion battery separator. Cellulose 2017, 24, 1889–1899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Li, M.; Ren, S.; Lei, T.; Lee, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Wu, Q. Zeolitic imidazolate framework-cellulose nanofiber hybrid membrane as Li-Ion battery separator: Basic membrane property and battery performance. J. Power Sources 2020, 454, 227878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiangtham, S.; Saito, N.; Manuspiya, H. Asymmetric Porous and Highly Hydrophilic Sulfonated Cellulose/Biomembrane Functioning as a Separator in a Lithium-Ion Battery. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 6206–6218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.W.; Chen, J.L.; Tian, T.; Shen, B.; Peng, Y.D.; Song, Y.H.; Jiang, B.; Lu, L.L.; Yao, H.B.; Yu, S.H. Sustainable Separators for High-Performance Lithium Ion Batteries Enabled by Chemical Modifications. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2019, 29, 1902023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Gao, C.; Peng, Q.; Gibril, M.E.; Wang, X.; Wang, S.; Kong, F. A novel high-performance electrospun of polyimide/lignin nanofibers with unique electrochemical properties and its application as lithium-ion batteries separators. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 246, 125668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, R.; Lizundia, E.; Silva, M.M.; Costa, C.M.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Mesoporous Cellulose Nanocrystal Membranes as Battery Separators for Environmentally Safer Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 3749–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.; Li, J.; Fan, W.; Zhao, T.; Chen, X.; Li, H.; Cui, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhao, Y. A review on nanofibrous separators towards enhanced mechanical properties for lithium-ion batteries. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 243, 110105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andresen, M.; Johansson, L.-S.; Tanem, B.S.; Stenius, P. Properties and characterization of hydrophobized microfibrillated cellulose. Cellulose 2006, 13, 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siró, I.; Plackett, D. Microfibrillated cellulose and new nanocomposite materials: A review. Cellulose 2010, 17, 459–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Li, X.; Zhuang, J.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, W. Cellulose microspheres enhanced polyvinyl alcohol separator for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolaimate, A.; Desbrieres, J.; Rhazi, M.; Alagui, A. Contribution to the preparation of chitins and chitosans with controlled physico-chemical properties. Polymer 2003, 44, 7939–7952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yano, H.; Nakahara, S. Bio-composites produced from plant microfiber bundles with a nanometer unit web-like network. J. Mater. Sci. 2004, 39, 1635–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Fu, J.; Du, Z.; Jia, X.; Qu, Y.; Yu, F.; Du, J.; Chen, Y. High-strength and flexible cellulose/PEG based gel polymer electrolyte with high performance for lithium ion batteries. J. Membr. Sci. 2020, 593, 117428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Biswal, B.K.; Zhang, J.; Balasubramanian, R. Hydrothermal Treatment of Biomass Feedstocks for Sustainable Production of Chemicals, Fuels, and Materials: Progress and Perspectives. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 7193–7294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, S.-J.; Choi, E.-S.; Lee, E.-H.; Kim, J.H.; Lee, S.-Y.; Lee, S.-Y. Eco-friendly cellulose nanofiber paper-derived separator membranes featuring tunable nanoporous network channels for lithium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 16618–16626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, L.; Li, Z.; Shi, R.; Quan, F.; Wang, B.; Ma, X.; Ji, Q.; Tian, X.; Xia, Y. Preparation and Properties of an Alginate-Based Fiber Separator for Lithium-Ion Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 38175–38182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Zhang, J.; Chai, J.; Ma, J.; Yue, L.; Dong, T.; Zang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, B.; Cui, G. Sustainable and Superior Heat-Resistant Alginate Nonwoven Separator of LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4/Li Batteries Operated at 55 °C. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 3694–3701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, L.; Liang, Y.; Huang, J.; Xing, L.; Hu, H.; Xiao, Y.; Dong, H.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, M. Mixed-Biomass Wastes Derived Hierarchically Porous Carbons for High-Performance Electrochemical Energy Storage. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2019, 7, 10393–10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ifuku, S.; Ikuta, A.; Egusa, M.; Kaminaka, H.; Izawa, H.; Morimoto, M.; Saimoto, H. Preparation of high-strength transparent chitosan film reinforced with surface-deacetylated chitin nanofibers. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 98, 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).