Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Novel influenza vaccines—including HD-IIV, rIV, cIV, and aIV—show superior relative vaccine efficacy (rVE) compared with standard-dose inactivated influenza vaccines (SD-IIV).

- However, when examined through the risk difference (ΔRD) and the number needed to vaccinate (ΔNNV), the absolute benefit at the population level is modest, with fewer than 10 additional cases prevented per 1000 vaccinations.

What are the implications of the main findings?

- Although newer influenza vaccines offer improved relative efficacy, the modest absolute benefit highlights that standard-dose influenza vaccines remain highly relevant and valuable for public health.

- This suggests that while enhanced vaccines provide incremental improvements, broadening immunization continues to be an important and effective strategy, irrespective of vaccine type, especially when considering cost, availability, and overall impact at the population level.

Abstract

Annual influenza vaccination remains critical for mitigating severe illness and reducing healthcare strain, particularly among high-risk populations. Despite advancements in vaccine platforms, the comparative efficacy of novel vaccines—such as high-dose (HD-IIV), recombinant (rIV), cell-based (cIV), and adjuvanted (aIV) influenza vaccines—versus standard-dose non-adjuvanted (SD-IIV) vaccines remains a public health concern. Traditional Relative Vaccine Efficacy (rVE) metrics, though robust, may overestimate population-level benefits. This short communication explores alternative comparative efficacy measures: risk difference (ΔRD) and number needed to vaccinate (ΔNNV). Analysis of data derived from randomized controlled trials (RCTs), or robust pragmatic trials, shows that while rVE values for newer vaccines often indicate superior efficacy, ΔRD and ΔNNV highlight the limits in incremental protection at the population level, with ΔRD generally below 10 cases per 1000 vaccinated. These findings underline the sustained relevance of SD-IIV in immunization programs and emphasize the need for broader vaccine coverage to highlight the benefits of vaccination and enhance population health outcomes.

1. Introduction

Influenza remains a global health threat, causing a significant socioeconomic burden. It strains healthcare systems and leads to reduced productivity. This underscores the urgent need for effective prevention and management strategies [1].

Annual vaccination is the most effective way to prevent severe disease, reduce epidemic impact, and alleviate strain on healthcare systems [2]. It serves dual purposes: direct protection of vaccinated individuals and indirect protection through reduced viral circulation. Influenza vaccines with an optimal (absolute) efficacy profile can better protect people from the viral infection and its consequences; in addition, when vaccine coverage is sufficiently high, herd immunity can protect individuals who cannot be vaccinated. Vaccination is especially crucial for high-risk groups. Despite this, influenza vaccination coverage remains suboptimal in most countries, limiting the full potential of immunization programs [2].

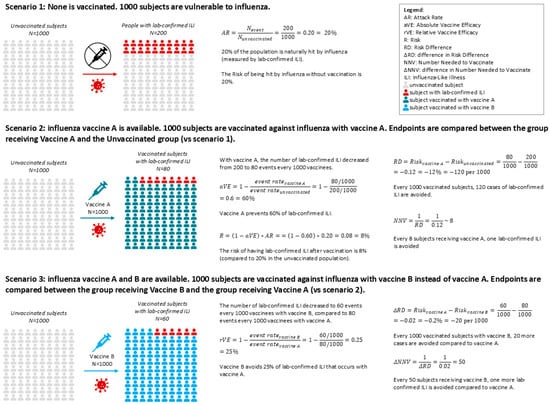

Traditionally, the vaccine efficacy/effectiveness (VE) measures how well a vaccine prevents specific flu-related outcomes (see Figure 1), but could depend on various vaccine-independent factors such as vaccine type, influenza season, geography, matching status, and subject subgroup [3]. To enhance protection, newer vaccines with higher antigen content have been developed, the high-dose influenza vaccine (HD-IIV, 60 µg HA per strain) and the recombinant influenza vaccine (rIV, 45 µg HA per strain), which are more immunogenic compared to standard-dose vaccines (SD-IIV, 15 µg HA per strain) and could provide better protection [4,5,6]. Additionally, rIV and cell-based influenza vaccines (cIV) avoid egg-based manufacturing, allowing for faster production, avoiding the risk of egg shortages and of potential egg-adaptive mutations [7]. Further, adjuvants like MF59 can be added to the vaccine formulation to increase the immune response in the recipients [8].

Figure 1.

Example of natural incidence of influenza in an unvaccinated population (Scenario 1), and how it changes when the population is vaccinated with two different vaccines (Scenarios 2 and 3). Scenario 1: Natural incidence of influenza. Scenario 2: The Absolute Vaccine Efficacy aVE represents how well a vaccine can prevent the disease. Scenario 3: If the placebo arm is absent in an RCT comparing vaccine A with vaccine B, it is not possible to calculate the AR and the aVE for each vaccine and then compare the two to calculate the relative efficacy. Regardless, estimates of relative values are possible. Vaccination could be more impactful in the case of higher aVE, or if the disease has a higher attack rate (more cases to prevent).

Beyond VE, population-level metrics such as risk difference (RD) and number needed to vaccinate (NNV) offer valuable insights for public health planning: the RD measures the proportion of patients who avoid the infection-related outcome because of being vaccinated [9], while the NNV is the number of people who need to be vaccinated to prevent one outcome event, taking into account both the efficacy of the vaccine and the incidence of the disease [10]. These metrics quantify the absolute benefit of vaccination and help policymakers assess the real-world impact of vaccine strategies. When comparing newer vaccines to SD-IIV, these measures become relative (relative vaccine efficacy/effectiveness [rVE], difference in risk difference [ΔRD], and difference in number needed to vaccinate [ΔNNV]), providing a more nuanced understanding of incremental benefits (Figure 1).

It is well established that a high rVE value obtained in clinical trials, although describing a better performance of one vaccine over the other, may not always translate into substantially greater absolute benefits at the population level, and does not necessarily reflect the actual extent of added public health benefit over the standard of care. The difference in ΔRD and ΔNNV could be more relevant from a societal perspective.

This study aims to compare the public health benefits of newer vaccines and SD-IIV by estimating and comparing the respective ΔRD and ΔNNV, specifically focusing on clinical efficacy outcomes measured in randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

2. Materials and Methods

Several authors presented comprehensive systematic reviews and meta-analyses based on the extensive available literature on newer IV formulations (HD−IIV, cIV, rIV, aIV) [11]. We screened the reference lists of these reviews for articles that contain eligible study data on HD-IIV, cIV, or rIV (umbrella retrieval approach) [12] and focused our search on comparative RCTs against SD-IIV assessing lab-confirmed influenza-like illness (ILI).

We made an exception in the case of the adjuvanted vaccine (aIV): for this formulation, there is a lack of comparative RCTs against SD-IIV assessing lab-confirmed ILI, as highlighted in a previous systematic review [11], and only a few observational studies provided effectiveness estimates against lab-confirmed influenza, with highly heterogeneous results. For this review, a pragmatic trial [13] comparing adjuvanted vaccines with non-adjuvanted influenza vaccines against flu-related hospitalizations was included.

For each vaccine type, one representative study was selected to calculate rVE, ΔRD, and ΔNNV.

Calculations were based on reported event rates in the selected studies. ΔRD was defined as the difference in absolute risk between newer vaccines and SD-IIV, while ΔNNV was calculated as the inverse of ΔRD. These metrics were used to assess the incremental population-level benefit of newer vaccines over SD-IIV. Confidence intervals were included to evaluate statistical significance, and comparisons crossing zero were noted as not statistically significant (Table 1).

Table 1.

Definitions and formulas.

3. Results

3.1. Population Benefits Comparison of HD-IIV vs. SD-IIV

The DiazGranados 2014 [4] study evaluated HD-IIV in elderly populations, reporting a statistically significant rVE of 24% (95% CI [9.7, 36]) against lab-confirmed ILI (Table 2).

Table 2.

Vaccine-specific event rates, extrapolated from RCTs Diaz Granados 2014 [4], Dunkle 2017 [6], and Frey 2010 [14], and respective Relative Vaccine Efficacy (rVE), risk difference (ΔRD), and number needed to vaccinate (ΔNNV). A) HD-IIV vs. SD-IIV; B) rIV vs. SD-IIV; C) cIV vs. SD-IIV; D) aIV vs. SD-IIV.

Based on the data reported in the study, the ΔRDHD|SD against any lab-confirmed protocol-defined ILI was statistically significant at 4.6 per 1000 (95% CI [1.8, 7.4]) vaccinated individuals; the statistically significant ΔNNVHD|SD was 219 (95% CI [136, 565]).

There is limited available data about the efficacy profile stratified by virus subtype or matching status. Subgroup analyses showed ΔRD values of 2.3 (95% CI [−0.064, 4.6]) for matched B strains and 4.4 (95% CI [−0.2, 9.1]) (unmatched A-H3N2 strains) per 1000, though these were not statistically significant. Notably, the rVE was higher for matched strains at 31% (95% CI [−1.0, 53]) than for unmatched at 16% (95% CI [−1, 30]), and both were not statistically significant, highlighting the complexity of interpreting efficacy across subtypes. The ΔNNVHD|SD values for matched B strains and unmatched A-H3N2 strains were 436 (95% CI [22, ∞]) and 222 (95% CI [11, ∞]), respectively, with both being statistically significant.

3.2. Population Benefits Comparison of rIV vs. SD-IIV

The Dunkle 2017 paper compared the efficacy of rIV with SD-IIV in older adults (above 50 years of age) during the 2014–2015 influenza season [6]. The study showed that an rVErIV|SD of 30% (95% CI [10, 47]) overall and an rVErIV|SD of 36% (95% CI [14, 53]) during a season with an antigenic mismatch were both statistically significant. Antigenically matched rVE was 4.2% (95% CI [−72, 46]), which was not statistically significant.

The ΔRDrIV|SD against any lab-confirmed protocol-defined ILI was statistically significant at 9.8 per 1000 (95% CI [2.9, 17]) persons. The corresponding ΔNNVrIV|SD was 102 (95% CI [59, 345]), which was statistically significant. In case of antigenic mismatch, ΔRDrIV|SD is 9.1 per 1000 persons (95% CI [3.0, 1.5]), and the corresponding ΔNNVrIV|SD is 110 (95% CI [66, 332]), with both statistically significant. The ΔRDrIV|SD and ΔNNVrIV|SD were 0.23 per 1000 (95% CI [−0.29, 3.3]) and 4256 (95% CI [303, ∞]), where neither were statistically significant (Table 2).

These results suggest that rIV may offer greater benefit in seasons with poor antigenic match, though the absolute gains remain modest.

3.3. Population Benefits Comparison of cIV vs. SD-IIV

The Frey 2010 study assessed cIV in adults under 50 and reported a not statistically significant rVE of 17% (95% CI [−24, 45]) against lab-confirmed ILI [14]. The ΔRDcIV|SD was 2.3 per 1000 persons (95% CI [−2.7, 7.4]), not statistically significant; and ΔNNVcIV|SD was statistically significant at 426 (95% CI [13, ∞]). In matched H1N1 seasons, rVE reached 40% (95% CI [−84, 80]), not statistically significant, with the respective ΔRDcIV|SD being not statistically significant at 0.87 per 1000 persons (95% CI [−0.010, 2.8]) and statistically significant ΔNNVcIV|SD being 1143 (95% CI [358, ∞]). For mismatched B strains, rVE was −4% (95% CI [−74, 39]) and not statistically significant, and the ΔRDcIV|SD was not statistically significant at −0.26 per 1000 (95% CI [−4.2, 3.7]). The ΔNNVcIV|SD was statistically significant and estimated to be less than 0. These findings highlight the limited incremental benefit of cIV in younger populations (Table 2).

3.4. Population Benefits Comparison of aIV vs. Non-Adjuvanted SD-IIV

The McConeghy 2021 study compared the immunogenicity and effectiveness of the aIV versus the non-adjuvanted SD-IIV in preventing hospitalizations in nursing homes among older adults (≥65 years) [13]. The study reported a statistically significant rVE of 21% (95% CI [6.7, 33]) against pneumonia and influenza-related hospitalizations. The ΔRDaIV|SD was 2.6 per 1000 patients (95% CI [0.08, 4.4]), while the corresponding ΔNNVaIV|SD was 383 (95% CI [225, 1282]), with both being statistically significant.

4. Discussion

The results of our analysis demonstrate the population-level impact of influenza vaccination using available vaccine formulations. SD-IIV provide a foundational level of protection, while newer and enhanced vaccines—such as HD-IIV, rIV, cIV, and aIV—offer modest incremental benefits when evaluated through ΔRDnew|SD and ΔNNVnew|SD metrics.

The two measures included, ΔRDnew|SD and ΔNNVnew|SD, provided a different perspective on the added population protection related to uptake of newer vaccines. While ΔRDnew|SD per 1000 shows how many more people are protected by the new vaccines if 1000 persons receive the new vaccines instead of the SD-IIV, the ΔNNVnew|SD is the number of persons who should receive the newer vaccine (besides the ones receiving the SD-IIV) to prevent one extra outcome (over the cases already prevented by the SD-IIV).

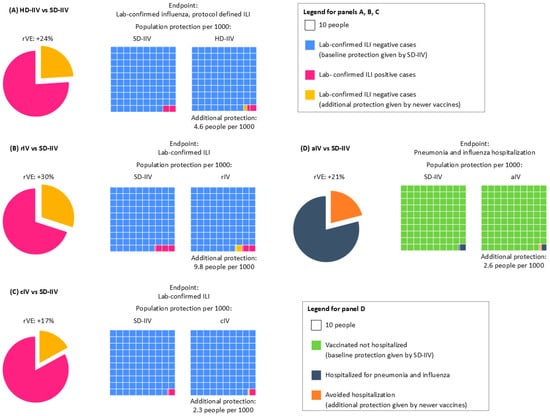

While rVE values for the four newer vaccines often appear favorable, they do not necessarily translate into substantial public health gains. For example, ΔRD values generally remain below 10 cases per 1000 vaccinated individuals. Indeed, it is well known that when all the vaccines are effective and rVE is high, the ΔRD could remain small if the disease incidence is relatively low. The calculated NNV is high, indicating that a large number of individuals must be vaccinated to prevent a single additional case [15,16]. Conversely, the smaller the ΔNNV, the more impactful the newer vaccine is compared to the SD-IIV. Overall, a favorable rVE is not indicative of significantly better population protection conferred by the new vaccines compared to the SD-IIV, while the ΔRD and the ΔNNV indicate that SD-IIV still has good population protection rates, and that newer vaccines can provide modest benefits. This underscores the importance of interpreting efficacy data through a population lens, especially when informing public health strategies (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Relative Vaccine Efficacy and impact of vaccinating people with (A) HD-IIV, (B) rIV, (C) cIV, or (D) aIV compared with SD-IIV. Panels A, B, and C show rVE against lab-confirmed ILI, as extrapolated from RCTs Diaz Granados 2014 [4], Dunkle 2017 [6], and Frey 2010 [14]. Panel D shows rVE against pneumonia and influenza hospitalization, as extrapolated from the pragmatic trial McConeghy 2021 [13]. The four cases show the following: pie chart on the left, the rVE or each vaccine compared to SD-IIV (in yellow), and on the right, the outcome incidence rate with the two vaccines (pink boxes for A, B, and C; gray boxes for D). The yellow boxes in A–D highlight the additional number of cases avoided with the use of newer vaccines compared to the baseline cases avoided by SD-IIV.

From a policymaker’s perspective, these findings suggest that the modest protection gains of newer vaccines may not justify widespread replacement of SD-IIV in national immunization programs, particularly given cost considerations or logistical constraints.

For instance, people vaccinated with HD-IIV are at lower risk of developing lab-confirmed ILI than those receiving SD-IIV (rVE 24%), but the incremental protection provided by HD-IIV, as highlighted by small ΔRD values, is modest (Figure 2A). Achieving additional benefits on a societal level requires a large number of vaccinees to materialize. Further, a recent publication has also reported that the HD vaccine showed limited incremental benefit in reducing hospitalizations compared to the SD vaccine, even in high-risk populations [17]. Similarly, rIV and cIV demonstrate improved rVE in certain scenarios, such as antigenic mismatch seasons, but their ΔRD values remain modest, and ΔNNV values are often prohibitively high (Figure 2B,C). rIV seemed to offer high protection against lab-confirmed ILI compared to SD-IIV (rVE 30%), which can be higher (rVE 36%) during seasons with an antigenic mismatch (Figure 2B). Also for rIV, when considering population benefits, the data available so far did not provide evidence of a better performance of rIV against SD-IIV, as the ΔRD remains below 10 cases per 1000 vaccinated persons (Figure 2B).

The efficacy profile of cIV suffers similar issues: while rVE against lab-confirmed ILI is 17%, reaching up to 40% in the case of the H1N1 predominantly matched season, the benefits at the population level are less evident, with only 2.3 additional people better protected per 1000 persons (down to 0.87 in case of H1N1 predominantly matched season) (Figure 2C).

aIV showed an efficacy of 17% against pneumonia and influenza-related hospitalization over non-adjuvanted SD-IIV; however, only 2.6 people per 1000 were better protected (Figure 2D).

A recent study showed that rIV performs significantly better against influenza infection (PCR confirmed), but there is no significance for hospitalization endpoints [18]. Further, it is associated with a larger NNV, as around 3000 individuals must be vaccinated with the recombinant vaccine to prevent one extra case of lab-confirmed influenza compared to the SD-IIV in certain age groups [19].

One limitation of our study is that we considered only one influenza-related endpoint/outcome for practical reasons. Meta-analyses have shown that HD-IIV may reduce all-cause hospitalizations by approximately 11% compared with SD-IIV [20], and influenza vaccination overall is associated with significant reductions in cardiovascular mortality [21]. These findings underscore that influenza vaccine impact extends beyond influenza case prevention and includes secondary benefits that are clinically and economically relevant. Nevertheless, given the epidemiological characteristics of influenza, the magnitude of benefit depends primarily on population coverage rather than vaccine type. We intend to emphasize that rVE, ΔRD, and ΔNNV should be interpreted in the context of their calculation, not as standalone values. Broader endpoints such as all-cause hospitalizations or mortality are clinically relevant, but estimating their population-level impact would require assumptions that expose them to high risks of bias. For this reason, we focused on consistently reported endpoints from RCTs and pragmatic trials, while acknowledging that the ultimate goal of vaccination is to reduce severe outcomes and improve public health.

While our analysis focused on comparative efficacy metrics, vaccine platform characteristics such as production timelines and avoidance of adaptive mutations could be relevant for public health planning in the case of pandemic scenarios, where rapid scale-up or improved antigenic fidelity are critical for disease control.

Importantly, the RD and NNV metrics focus on direct protection and do not account for indirect effects such as reduced transmission and herd immunity. As highlighted in previous studies, the full impact of vaccination is nonlinear and extends beyond individual-level efficacy [22]. Therefore, while newer vaccines may offer advantages in specific subpopulations, broad vaccine coverage remains the most effective strategy for maximizing public health outcomes [23,24].

5. Conclusions

This comparative analysis confirms that while newer and enhanced influenza vaccines offer incremental benefits, SD-IIV continues to play a critical role in influenza control at the population level. This overall conclusion aligns with the assessment of the WHO, which advocates the use of standard vaccines that are broader in coverage, more widely available, and more affordable than newer vaccines. For policymakers, the decision to adopt newer vaccines should be guided not only by rVE but also by ΔRD, ΔNNV, and broader public health considerations. Given the modest population-level impact (small reduction in ΔRD, large estimate for ΔNNV) and higher costs associated with newer vaccines, maintaining widespread access to SD-IIV in national immunization programs targeting at-risk populations is a pragmatic and effective approach. Newer and enhanced vaccines will continue having a role in providing improved protection for at-risk groups with specific risk factors, and to guarantee supply chain resilience and manufacturing diversification, which is important for long-term planning but beyond the scope of this analysis. Policymakers must weigh these implications when designing immunization strategies.

Furthermore, indirect benefits of vaccination—such as reduced transmission and enhanced herd protection—are not captured by rVE, ΔRD, or ΔNNV metrics but are essential to achieving long-term public health goals.

Beyond direct influenza control, vaccination irrespective of type contributes to reducing severe outcomes, including hospitalizations and cardiovascular mortality, as highlighted by recent consensus recommendations [25]. These secondary benefits reinforce the importance of broad coverage as the primary driver of public health impact.

Increasing coverage is a key public health priority and aligns with global health policy goals. Altogether, this evidence supports the need for further efforts to increase vaccination uptake with the currently available vaccines, rather than focusing on selective uptake of newer formulations in specific and small subgroups. Our findings are fully in line with the Vaccines against influenza: WHO position paper—May 2022 [1].

In summary, a population-focused strategy that emphasizes coverage and equity in vaccine access will yield the greatest public health benefit, supporting the continued use of SD-IIV as a cornerstone of influenza prevention.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C., A.P., and S.H.; Data curation, L.C. and A.P.; Formal analysis, L.C. and A.P.; Funding acquisition, S.H.; Investigation, L.C. and A.P.; Methodology, A.P.; Project administration, L.C.; Resources, L.C., A.P., and S.H.; Supervision, S.H.; Validation, A.P. and S.H.; Visualization, L.C.; Writing—original draft, L.C.; Writing—review and editing, L.C., A.P., and S.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This manuscript has been supported by Viatris.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

Editorial support was provided by Pramod Mallikarjuna, Viatris Inc.

Conflicts of Interest

Laura Colombo is an employee of Viatris. Abraham Palache is a consultant for Viatris. Sanjay Hadigal is an employee of Viatris and holds shares.

References

- Vaccines Against Influenza: WHO Position Paper. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/who-wer9719 (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Influenza Vaccination Coverage and Effectiveness. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/influenza-vaccination-coverage-and-effectiveness (accessed on 12 December 2025).

- Osterholm, M.T.; Kelley, N.S.; Sommer, A.; Belongia, E.A. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2012, 12, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- DiazGranados, C.A.; Dunning, A.J.; Kimmel, M. Efficacy of High-Dose versus Standard-Dose Influenza Vaccine in Older Adults. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Gaglani, M.; Kim, S.S.; Naleway, A.L.; Levine, M.Z.; Edwards, L.; Murthy, K.; Dunnigan, K.; Zunie, T.; Groom, H.; Ball, S.; et al. Effect of Repeat Vaccination on Immunogenicity of Quadrivalent Cell-Culture and Recombinant Influenza Vaccines Among Healthcare Personnel Aged 18–64 Years: A Randomized, Open-Label Trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, e1168–e1176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunkle, L.M.; Izikson, R.; Patriarca, P.; Goldenthal, K.L.; Muse, D.; Callahan, J.; Cox, M.M. Efficacy of Recombinant Influenza Vaccine in Adults 50 Years of Age or Older. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017, 376, 2427–2436. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, N.C.; Lv, H.; Thompson, A.J.; Wu, D.C.; Ng, W.W.; Kadam, R.U.; Lin, C.-W.; Nycholat, C.M.; McBride, R.; Liang, W.; et al. Preventing an Antigenically Disruptive Mutation in Egg-Based H3N2 Seasonal Influenza Vaccines by Mutational Incompatibility. Cell Host Microbe 2019, 25, 836–844.e5. [Google Scholar]

- O’hAgan, D.; Ott, G.; De Gregorio, E.; Seubert, A. The mechanism of action of MF59—An innately attractive adjuvant formulation. Vaccine 2012, 30, 4341–4348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ranganathan, P.; Pramesh, C.S.; Aggarwal, R. Common pitfalls in statistical analysis: Absolute risk reduction, relative risk reduction, and number needed to treat. Perspect. Clin. Res. 2016, 7, 51–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A.; Dang, V.; Bolotin, S.; Crowcroft, N.S. How and why researchers use the number needed to vaccinate to inform decision making--a systematic review. Vaccine 2015, 33, 753–758. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- ECDC. Systematic Review Update on the Efficacy, Effectiveness and Safety of Newer and Enhanced Seasonal Influenza Vaccines for the Prevention of Laboratory-Confirmed Influenza in Individuals Aged 18 Years and Over; ECDC: Stockholm, Sweden, 2024.

- Ioannidis, J.P.A. Integration of evidence from multiple meta-analyses: A primer on umbrella reviews, treatment networks and multiple treatments meta-analyses. Can. Med Assoc. J. 2009, 181, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConeghy, K.W.; Davidson, H.E.; Canaday, D.H.; Han, L.; Saade, E.; Mor, V.; Gravenstein, S. Cluster-randomized Trial of Adjuvanted Versus Nonadjuvanted Trivalent Influenza Vaccine in 823 US Nursing Homes. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2021, 73, e4237–e4243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, S.; Vesikari, T.; Szymczakiewicz-Multanowska, A.; Lattanzi, M.; Izu, A.; Groth, N.; Holmes, S. Clinical Efficacy of Cell Culture–Derived and Egg-Derived Inactivated Subunit Influenza Vaccines in Healthy Adults. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, 997–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardeny, O.; Kim, K.; Udell, J.A.; Joseph, J.; Desai, A.S.; Farkouh, M.E.; Hegde, S.M.; Hernandez, A.F.; McGeer, A.; Talbot, H.K.; et al. Effect of High-Dose Trivalent vs Standard-Dose Quadrivalent Influenza Vaccine on Mortality or Cardiopulmonary Hospitalization in Patients With High-risk Cardiovascular Disease: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, L.R.; Ferguson, N.M.; Donnelly, C.A.; Grassly, N.C. Measuring Vaccine Efficacy Against Infection and Disease in Clinical Trials: Sources and Magnitude of Bias in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccine Efficacy Estimates. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, e764–e773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaron, S.; Yechezkel, M.; Yamin, D.; Razi, T.; Borochov, I.; Shmueli, E.; Arbel, R.; Netzer, D. Incremental benefit of high dose compared to standard dose influenza vaccine in reducing hospitalizations. npj Vaccines 2025, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hsiao, A.; Yee, A.; Fireman, B.; Hansen, J.; Lewis, N.; Klein, N.P. Recombinant or Standard-Dose Influenza Vaccine in Adults under 65 Years of Age. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 389, 2245–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebell, M.H. High-Dose Recombinant Influenza Vaccine: NNT = 3,000 to Prevent One More Infection, No Impact on Hospitalization. Am. Fam. Physician. 2024, 109, 372. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.K.; Lam, G.K.; Yin, J.K.; Loiacono, M.M.; Samson, S.I. High-dose influenza vaccine in older adults by age and seasonal characteristics: Systematic review and meta-analysis update. Vaccine X 2023, 14, 100327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yedlapati, S.H.; Khan, S.U.; Talluri, S.; Lone, A.N.; Khan, M.Z.; Khan, M.S.; Navar, A.M.; Gulati, M.; Johnson, H.; Baum, S.; et al. Effects of Influenza Vaccine on Mortality and Cardiovascular Outcomes in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2021, 10, e019060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuite, A.R.; Fisman, D.N. Number-needed-to-vaccinate calculations: Fallacies associated with exclusion of transmission. Vaccine 2013, 31, 973–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahmeier, K.; Speckemeier, C.; Neusser, S.; Wasem, J.; Biermann-Stallwitz, J. Vaccinating the German Population Aged 60 Years and Over with a Quadrivalent High-Dose Inactivated Influenza Vaccine Compared to Standard-Dose Vaccines: A Transmission and Budget Impact Model. Pharmacoeconomics 2023, 41, 1539–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, D.; Anastassopoulou, A.; Nautrup, B.P.; Schmidt-Ott, R.; Eichner, M.; Schwehm, M.; Dos Santos, G.; Ultsch, B.; Bekkat-Berkani, R.; von Krempelhuber, A.; et al. Cost-utility analysis of increasing uptake of universal seasonal quadrivalent influenza vaccine (QIV) in children aged 6 months and older in Germany. Hum. Vaccines Immunother. 2022, 18, 2058304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidecker, B.; Libby, P.; Vassiliou, V.S.; Roubille, F.; Vardeny, O.; Hassager, C.; Gatzoulis, M.A.; Mamas, M.A.; Cooper, L.T.; Schoenrath, F.; et al. Vaccination as a new form of cardiovascular prevention: A European Society of Cardiology clinical consensus statement. Eur. Heart J. 2025, 46, 3518–3531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.