Abstract

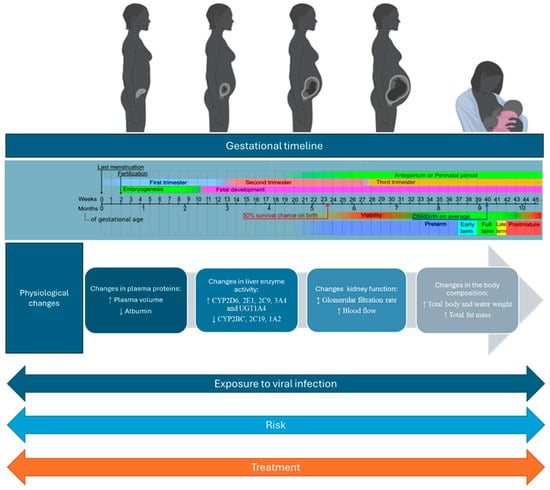

Addressing the complexities of managing viral infections during pregnancy is essential for informed medical decision-making. This comprehensive review delves into the management of key viral infections impacting pregnant women, namely Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), Hepatitis B Virus/Hepatitis C Virus (HBV/HCV), Influenza, Cytomegalovirus (CMV), and SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). We evaluate the safety and efficacy profiles of antiviral treatments for each infection, while also exploring innovative avenues such as gene vaccines and their potential in mitigating viral threats during pregnancy. Additionally, the review examines strategies to overcome challenges, encompassing prophylactic and therapeutic vaccine research, regulatory considerations, and safety protocols. Utilizing advanced methodologies, including PBPK modeling, machine learning, artificial intelligence, and causal inference, we can amplify our comprehension and decision-making capabilities in this intricate domain. This narrative review aims to shed light on diverse approaches and ongoing advancements, this review aims to foster progress in antiviral therapy for pregnant women, improving maternal and fetal health outcomes.

2. Viral Infections Relevant to Pregnancy

Viral infections relevant to pregnancy encompass a variety of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. These infections, contracted before or during pregnancy, can be transmitted to the fetus through various routes, including congenitally during gestation, perinatally during labor and childbirth, and postnatally through breastfeeding [26,29]. Specifically, this review will delve into viruses posing significant risks during pregnancy, as well as those for which optimal treatment strategies are still underexplored. Such viruses include human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV), cytomegalovirus (CMV), influenza A virus (IAV), and the recently emerged SARS-CoV-2.

2.1. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) in Pregnancy

HIV belongs to the Lentivirus genus and Retroviridae family, characterized by single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA [30]. It targets CD4+ lymphocytes, integrating into the host–cell genome, and leads to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) [31]. HIV-1 is globally prevalent and more virulent, while HIV-2 is confined to West Africa. Transmission occurs through blood, semen, and vaginal fluids, with mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) possible during pregnancy, delivery, and breastfeeding [32]. Maternal HIV-1 infection correlates with adverse pregnancy outcomes such as premature labor and miscarriage. Vertical transmission routes include intrauterine, intrapartum, and postpartum transmission, influenced by maternal viral load, immune status, and birth mode [26]. In women with HIV infection, additional infections affecting the placenta, fetal membranes, genital tract, and breast tissue, as well as systemic infections in both the mother and the infant, have been demonstrated to elevate the risk of MTCT of HIV [33].

Maternal HIV diagnosis relies on virologic assays, particularly polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, which are considered the gold standard for detecting HIV infection in both infants and adults. For infant HIV diagnosis, virologic assays are essential due to maternal immunoglobulin IgG transfer, with PCR assays serving as the gold standard. Prompt testing within days of birth and subsequent follow-ups are crucial [34]. All pregnant women should undergo HIV screening, with immediate testing recommended for those with unknown HIV status during labor or delivery. Point-of-care testing for infants can enhance early diagnosis, especially in resource-limited settings [35]. Clinical management strategies, including cesarean section and antiretroviral therapy, significantly reduce the risk of transmission. During pregnancy, the placenta’s antiviral response limits vertical transmission, although HIV persists in peripheral blood monocytes despite antiretroviral therapy [36,37]. Placental alterations, including inflammation and vascular malperfusion, contribute to adverse outcomes. Placental macrophages and T regulatory cells play roles in controlling MTCT [38]; therefore, Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART) is vital, but the timing and type of HAART initiation influence maternal and fetal outcomes. HAART may increase preterm delivery risk due to potential toxicity and immune dysregulation [39]. Assessing antiretroviral safety in pregnancy is crucial for optimizing treatment. The prevention of MTCT is a significant achievement with HAART, recommended for all pregnant women with HIV regardless of CD4+ count. Elective cesarean delivery and neonatal prophylaxis reduce transmission risk, with zidovudine (ZDV) being a common prophylactic treatment [40]. ZDV/lamivudine (3TC) and ZDV are more effective in reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission, with ZDV/3TC also showing a reduced risk of stillbirth [41]. However, concerns remain regarding toxicity in HIV-exposed uninfected infants, emphasizing the need for monitoring and follow-up [22].

2.2. Hepatitis B and C Virus (HBV and HCV) in Pregnancy

HBV and HCV are hepatotropic viruses that belong to the Hepadnaviridae family; they are bloodborne pathogens posing significant risks during pregnancy, primarily through MTCT [42]. HBV, a globally prevalent pathogen, is transmitted mainly in the third trimester, with transmission rates reaching up to 90% [43,44]. Despite effective strategies like immunoprophylaxis and antiviral treatments, vertical transmission rates remain high due to uneven vaccine coverage and prophylaxis failures [45]. HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) is a crucial viral marker, indicating hepatitis B virus infection, while HCV-RNA signifies active hepatitis C virus infection. During pregnancy, women are routinely screened for HBsAg, followed by further testing for HBV-DNA and serologic markers. Likewise, infants born to HCV-positive mothers undergo testing for HCV-RNA and are closely monitored for up to 18 months post-birth. It is advised to minimize invasive prenatal procedures, and cesarean section is not recommended solely for preventing the vertical transmission of hepatitis viruses. However, perinatal HBV transmission can be effectively prevented by identifying HBV-positive pregnant women (HBsAg-positive) and promptly administering the hepatitis B vaccine and immune globulin to newborns within 12 h of delivery [46]. Initiating antiviral therapy for HBV at 28–32 weeks’ gestation can reduce transmission risk for high viral loads [47]. HBV transmission mechanisms include transplacental leakage, placental infection, and the crossing of infected maternal blood cells into the placenta. Maternal immune changes during pregnancy may promote HBV transmission, leading to immune-tolerant HBV infection in the fetus [48]. Conversely, HCV infection alters placental morphology, increasing the risk of complications such as preterm birth and stillbirth [49]. The risk of HCV transmission is heightened when there is a high maternal serum viral load during delivery, indicating active viremia [50]. This risk escalates proportionately with increasing levels of viral load above 105 IU/mL and peaks at levels exceeding 107 IU/mL [51,52]. Tenofovir (TDF) first-line antiviral medication is advised for such instances, beginning at week 28 of pregnancy and continuing until birth. Three months after giving birth, treatment may continue. Every pregnant patient with an HBV diagnosis needs to be referred to a physician who specializes in treating HBV infections for follow-up care. Because liver health and HBV infection can fluctuate over time, it is imperative to have regular monitoring throughout life. Additionally, elevated maternal serum ALT levels in the 12 months preceding pregnancy and/or during delivery are indicative of a higher viral replication rate, potentially leading to more extensive hepatic damage and subsequent ALT elevation [53,54]. Early screening of HCV-exposed infants is essential for prompt treatment and prevention of complications, emphasizing the importance of comprehensive management strategies to mitigate vertical transmission risks of HBV and HCV during pregnancy [22].

2.3. Influenza in Pregnancy

Influenza viruses are RNA viruses from the family Orthomyxoviridae. Influenza viruses, particularly type A, cause respiratory symptoms and spread mainly through airborne droplets. Pregnant women face increased susceptibility and risks of severe complications from influenza, especially in later gestational stages [55]. Influenza virus infection during pregnancy poses significant risks to both the mother and fetus, leading to various acute and chronic complications. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) study published in October 2020 found that flu infection during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of pregnancy loss, a reduction in the birthweight of full-term newborns, and an increased risk of late pregnancy loss (defined as pregnancy loss after 13 weeks gestation). Pregnant women with respiratory illness symptoms and fever were also found to have an increased risk of preterm birth. The study included 11,277 pregnant women from India, Peru, and Thailand during the 2017 and 2018 flu seasons. Only 13% of study participants had been vaccinated against flu. This study underscores the potential importance of flu vaccination in pregnant women to prevent poor pregnancy outcomes associated with flu infection [56].

Although the vertical transmission of the influenza virus to the fetus is rare, maternal infection can still affect fetal health through mechanisms like placental damage, apoptosis, and viral replication, potentially leading to adverse outcomes such as intrauterine growth restriction and birth defects [57]. Pregnancy may increase susceptibility to infection and raise the chance of major illness outcomes due to physiological and immunological changes [58]. Pregnant women exhibit reduced interferon responses, heightening their vulnerability to severe outcomes [59]. The virus can cause placental damage, disrupting nutrient and oxygen exchange between the mother and fetus [60]. Dysregulated maternal immune responses, including excessive inflammation and cytokine production, can contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes and fetal damage [61]. Offspring born to mothers who experienced influenza virus infection during pregnancy face an increased risk of long-term neurological disorders like schizophrenia [62]. In chronic complications, influenza infection during pregnancy can trigger long-term cardiovascular issues due to vascular dysfunction and inflammation [63]. Pregnant women infected with influenza, including types like swine flu (H1N1), may experience more severe symptoms and complications compared to non-pregnant individuals, often resulting in higher hospitalization rates and mortality. Respiratory complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and secondary bacterial or viral pneumonia can occur, contributing to maternal morbidity and mortality [64].

Preventive measures for pregnant individuals include receiving the influenza vaccine, practicing good hygiene, and seeking prompt medical attention if symptoms develop [65]. Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for effectively managing and mitigating the risks associated with influenza virus infection during pregnancy [22]. Further research is imperative to gain a deeper understanding of these outcomes and to differentiate influenza from other pathogens. This differentiation is particularly important given that influenza viruses, while posing risks to pregnancy outcomes, do not fit into the traditional TORCH group. There is a need for more mechanistic studies, to enhance our understanding of influenza’s unique impact on maternal and fetal health.

2.4. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) in Pregnancy

The CMV, a DNA virus belonging to the Betaherpesvirinae subfamily of the Herpesviridae family [66], is associated with severe clinical outcomes in cases of congenital infection, particularly prevalent among individuals with limited socioeconomic resources [67]. The risk of primary CMV infection during pregnancy is notable because a relatively large proportion of women of reproductive age are CMV-seronegative [68]. Unlike other infectious diseases, CMV presents an increased risk of fetal involvement during pregnancy due to the high prevalence of seropositivity among women of childbearing age [69]. The transmission of CMV during pregnancy can range from 20 to 70% during primary maternal infections, with a reduced risk during recurrent infections [70]. Placental dysfunction is a critical factor in the development of congenital CMV infection [71]. CMV replication in cytotrophoblasts leads to placental edema, fibrosis, and compromised nutrient and oxygen transport to the fetus [72]. CMV-induced placental damage results from a combination of molecular mechanisms, such as impaired extracellular matrix development, the IL-10-mediated inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases, and the activation of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor [72]. Untreated CMV infections pose significant risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes, developmental disabilities, and long-term health complications for the newborn, including developmental delays and neurodevelopmental disorders. Neonates infected with CMV may display symptoms like intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), purpura, jaundice, hepatosplenomegaly, microcephaly, hearing impairment, and thrombocytopenia [73]. Long-term complications, such as neurological disorders and sensory impairments, are observed in approximately 40–60% of neonates symptomatic at birth [74].

Diagnosing congenital CMV infection involves serological testing for CMV-specific antibodies (IgM, IgG, and IgG avidity) combined with PCR assays to detect viral DNA in maternal fluids and amniotic fluids [75]. Universal neonatal CMV screening using PCR assays on saliva or urine samples shows promise in identifying high-risk infants, though differentiating congenital from perinatal infection remains challenging [76]. Preventative measures for congenital CMV infection include educating pregnant women on hygiene practices and administering CMV hyperimmune globulins or antiviral drugs in specific cases. However, there is a lack of consensus on screening and preventive strategies which indicates a need for more research to establish evidence-based guidelines. While antiviral medications like valaciclovir, ganciclovir, and valganciclovir demonstrate efficacy in inhibiting CMV replication, there are no officially approved treatments for CMV infection during pregnancy [77]. The existing guidelines recommend that any antenatal therapy for CMV should be provided as part of a research protocol [78], and further research is needed to assess their safety and effectiveness in treating neonatal complications [79]. Studies have revealed significant gaps in knowledge and awareness of CMV among pregnant women and healthcare professionals. This lack of understanding hinders effective prevention and management efforts, highlighting the importance of education and training programs [80]. Evaluations of screening strategies have shown varying cost-effectiveness results, emphasizing the need to identify reliable and sensitive screening tests and establish mechanisms for implementation and monitoring [81]. CMV vaccine development continues to be a major public health priority, as highlighted by the absence of an available active vaccine. Research in this area is crucial to prevent congenital CMV infections and their associated complications [76,82].

2.5. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in Pregnancy

Lastly, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), is famously known for the global pandemic. Belonging to the Coronaviridae family [83], it is a newly discovered β-Coronavirus with a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus. SARS-CoV-2 primarily spreads through droplets and aerosols during close contact, with an incubation period of 2 to 14 days [84]. Neonatal and pediatric cases of SARS-CoV-2 are often mild and linked to family clusters, with evidence suggesting minimal vertical transmission during maternal infection [85,86]. However, diagnosing congenital infection remains challenging, with only a small percentage of neonatal cases confirmed as congenital infections [87]. The association between maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection, placental histomorphology, and perinatal outcomes remains uncertain, with limited published studies on how SARS-CoV-2 affects placental structure in infected pregnant women. However, recent research aimed to investigate these effects by conducting a retrospective cohort study on 47 pregnant women with confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection, matched with non-infected controls. The study found that while only one of the infected cases showed SARS-CoV-2 immunoreactivity in the syncytiotrophoblasts, there were significant histomorphological differences in placentas from SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnancies compared to the control group. These differences included higher rates of decidual vasculopathy, maternal vascular thrombosis, and chronic histiocytic intervillositis in the placentas from SARS-CoV-2-infected pregnancies. Furthermore, active SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy was associated with a lower gestational age at delivery, a higher rate of cesarean section, lower fetal-placental weight ratio, and poorer Apgar scores. Notably, active, symptomatic, and severe-critical maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection, along with placental inflammation, were linked to an increased risk of preterm delivery. Additionally, altered placental villous maturation and severe-critical maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection were associated with an elevated risk of poor Apgar scores at birth and maternal mortality, respectively [88]. In contrast, a prospective cohort study on 30 pregnant women infected with SARS-CoV-2 and their neonates found that maternal anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike antibodies could cross the placenta during pregnancy, resulting in neonates acquiring antibodies at birth. However, all neonates tested negative for SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the immunohistochemical staining for Spike protein in placental tissues was negative. The study also indicated a correlation between maternal and neonatal levels of total anti-SARS-CoV-2 Spike antibodies, with higher concentrations observed in pregnant women with moderate to severe/critical disease [89].

The severity of maternal SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with ischemic placental pathology, potentially leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Despite this, placental tissues did not show detectable SARS-CoV-2 infection, suggesting that placental infection is rare. Instead, SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy primarily induces unique inflammatory responses at the maternal–fetal interface, involving maternal T cells and fetal stromal cells. Additionally, maternal–fetal immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 did not compromise the T-cell repertoire or initiate IgM responses in neonates. Overall, these findings provide insights into the maternal–fetal immune responses triggered by SARS-CoV-2 and highlight the rarity of placental infection during maternal viral infection [90].

Pregnant women with COVID-19 are at an increased risk of developing severe complications, requiring hospitalization, and facing adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes, emphasizing the importance of timely treatment and preventive measures [91]. Therefore, preventing SARS-CoV-2 spread is crucial, with efforts focusing on vaccination, surveillance, and tracking new variants. Limited data on vaccine safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding are available, but initial reports suggest maternal vaccination with mRNA-based vaccines may confer passive immunity to neonates [92]. Continued monitoring is necessary to assess outcomes in vaccinated pregnant women and their infants.

Extensive research on the causes of viral infections during pregnancy is vital in protecting both mothers and babies from emerging pandemics. There is a need to advance our knowledge of antiviral treatments, vaccines, and their effects during pregnancy so we can enhance our ability to manage viral infections in pregnant women more effectively, reducing risks and improving outcomes for both mothers and babies (while mitigating the impact of future pandemics and epidemics). The aforementioned highlights the importance of ongoing research to refine antiviral therapies for pregnant individuals, enhancing our ability to respond effectively to future public health crises.

4. Vaccines and Pregnant Population: Emerging Areas and Strategies

Vaccination in pregnant populations is a critical area of focus to protect both mothers and infants from viral infections. The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the importance of vaccination during pregnancy. Pregnant individuals are at an increased risk of severe disease if they contract SARS-CoV-2 [139]. Fortunately, observational data have shown that the benefits of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination outweigh the potential risks for pregnant, postpartum, and lactating women. The World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and professional organizations recommend SARS-CoV-2 vaccination for this population [140].

Recent studies monitoring pregnant individuals who received SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have not raised any specific safety concerns related to pregnancy. Although pregnant women were initially excluded from clinical trials of SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, observational data have rapidly accumulated, confirming that the benefits of vaccination outweigh the potential risks [140,141]. Regarding the other viral infections discussed here, there is currently no specific HIV and HCV vaccine recommended for pregnant women. In the case of influenza and HBV, vaccines are generally safe during pregnancy. HBV can prevent vertical transmission to the newborn [142]. Inactivated influenza vaccines are recommended for all pregnant women to prevent maternal influenza infection and reduce complications during pregnancy [143]. For CMV, there is no specific vaccine available, pregnant individuals should follow hygiene measures to reduce exposure to CMV [144].

Prophylactic vaccines are generally the most recommended for viral infections during pregnancy, offering direct protection to the mother and indirect protection to the fetus [145]. Therapeutic vaccines, specifically gene vaccines, may have roles in select cases but require thorough evaluation considering the physiological and immunological changes in pregnancy [146]. In Table 2, we summarize information regarding prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines for viral infections during pregnancy. The suitability of different types of vaccination (prophylactic and therapeutic) varies depending on the viral infection and pregnancy stage. Prophylactic vaccines, such as those for influenza and SARS-CoV-2, are commonly used to prevent viral infections during pregnancy [147]. Therapeutic and gene vaccines are still in the early development stages for viruses like HIV, HBV/HCV, CMV, and SARS-CoV-2. Factors influencing vaccine suitability include the virus’s nature, pregnancy stage, and availability of safe candidates. It is crucial to consider specific viral infections, pregnancy stages, and potential risks for both mother and fetus when selecting vaccine types. Some infections may not recommend certain vaccine types, like live-attenuated vaccines, due to safety concerns.

Table 2.

Overview of prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines for viral infections during pregnancy.

HIV-ongoing research related to prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines during pregnancy include the multi-stage HIV vaccine regimen. Researchers from the George Washington University Vaccine Research Unit, in collaboration with other institutions, have developed a multi-stage HIV vaccine regimen. The first stage of this vaccine strategy aims to produce broadly neutralizing antibodies (bnAbs) capable of targeting a wide range of HIV variants. The vaccine showed favorable safety profiles and induced the targeted immune response in 97% of vaccinated individual [148]. Additionally, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) has launched a Phase 1 clinical trial evaluating three experimental HIV vaccines based on a messenger RNA (mRNA). This technology, similar to that used in SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines, holds promise for developing preventive HIV vaccines [149].

In the context of HBV and HCV co-infection in HIV-infected individuals, ongoing research on vaccines aims to enhance the understanding of mechanisms that promote HBV infection in this population. Strategies are being explored to reduce the prevalence of HBV co-infection among individuals living with HIV [150]. It is necessary to understand the specific mechanisms that contribute to increased susceptibility to HBV infection in individuals with HIV. Factors such as immune suppression, altered immune responses, and shared routes of transmission between HIV, HBV, and HCV may play a role in promoting HBV infection in HIV-infected individuals. Vaccines that can effectively prevent HBV infection in individuals living with HIV aim to enhance immune responses, provide long-lasting protection, and reduce the risk of HBV co-infection in the HIV-infected population [151]. Strategies to reduce the prevalence of HBV co-infection in HIV-infected individuals include targeted vaccination programs, early screening for HBV, and integrated care models that address both HIV and HBV management. Efforts are being made to improve access to vaccination, promote adherence to vaccination schedules, and enhance awareness about the importance of HBV prevention in the context of HIV care. By reducing the burden of HBV co-infection in individuals with HIV, these research efforts have the potential to improve health outcomes, reduce liver-related complications, and enhance the overall well-being of HIV-infected individuals. Strategies aimed at preventing HBV co-infection can have a significant impact on public health by reducing the transmission of HBV, improving treatment outcomes, and lowering the overall disease burden in the HIV-infected population.

Influenza vaccines, though not pregnancy-specific, are continually evolving through ongoing research. Recommended for all pregnant women, they prevent maternal influenza infection and related complications during pregnancy. Current research aims to enhance vaccine efficacy, safety, and immune responses, adapting to the dynamic influenza virus [143]. Efforts focus on expanding vaccine coverage, especially among high-risk groups like older women and those with pre-existing conditions. Additionally, research addresses vaccination disparities among socioeconomically disadvantaged women. Safety assessments of influenza vaccination during pregnancy evaluate potential risks of adverse birth outcomes and maternal non-obstetric adverse events. The World Health Organization advocates influenza vaccination for all pregnant women, leading many countries to implement vaccination programs, though coverage varies.

An effective CMV vaccine holds promise for preventing the majority of birth defects associated with congenital CMV infections. Candidate vaccines, including live-attenuated, protein subunit, DNA, and viral-vectored approaches, are under clinical evaluation. Subunit approaches target key CMV proteins, such as pp65, IE1, and glycoprotein B (gB), which induce cytotoxic T cells and neutralizing antibodies [152]. However, recent insights into CMV entry pathways highlight opportunities for improvement. Notably, a 5-subunit pentameric complex is crucial for viral entry into endothelial and epithelial cells, suggesting a potential target for vaccine enhancement [153]. Antibodies may inhibit post-entry CMV spread between cells, limiting viral replication and dissemination to the fetus [154,155]. Next-generation vaccine candidates, including peptides, recombinant proteins, DNA, viral vectors, and inactivated CMV, are in preclinical development, offering hope for a successful candidate [154,156].

SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, including mRNA-based vaccines, have been authorized for use during pregnancy [157]. Ongoing studies monitor safety and effectiveness in pregnant populations. The mRNA vaccines like those used for SARS-CoV-2 offer innovative approaches to immunization [158]. In pregnant populations, gene vaccines can provide robust immune responses without the use of live viruses, enhancing safety profiles for both mother and fetus. However, the implications of gene vaccines in pregnancy require careful consideration due to limited data on long-term effects and potential interactions with maternal and fetal immune systems [159,160]. They offer enhanced safety profiles by eliciting robust immune responses without live viruses, minimizing risks to both mother and fetus. Their rapid development timelines are advantageous for swiftly mutating viruses or public health crises. The adaptable nature of gene vaccine platforms allows for tailored formulations, addressing the unique physiological and immunological changes of pregnancy. Gene vaccines show potential in improving protection against viral infections for both pregnant women and their fetuses. However, adapting regulatory frameworks is crucial to ensure these vaccines are safely approved, monitored, and surveilled post-market. Continued research is essential to fully understand their safety, effectiveness, and optimal use in pregnant populations. Challenges include ensuring safety, addressing limited clinical evidence, and understanding how these vaccines interact immunologically and in terms of vertical transmission. Collaboration among researchers, developers, and regulators is key to advancing safe and effective gene vaccines for pregnant women, thereby enhancing maternal and fetal health protection against viral infections [161].

Recent advancements in maternal vaccination have led to the authorization of the RSV (Respiratory Syncytial Virus) vaccine for pregnant women in both the USA and the EU. In August 2023, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and in September 2023, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) approved the vaccine based on robust clinical data demonstrating its ability to significantly reduce severe RSV infections in infants during their first six months of life. This approval marks a crucial step in preventing RSV-related complications in newborns, as the virus commonly causes conditions like bronchiolitis and pneumonia [162]. Clinical trials have established the safety and efficacy of Abrysvo, the Pfizer-developed RSV vaccine, when administered to pregnant women. By triggering an immune response in the mother, the vaccine transfers protective antibodies to the fetus through the placenta, offering passive immunity to newborns during their early vulnerable months. Abrysvo is recommended for pregnant women between 32–36 weeks gestation, providing infants with protection from birth up to 6 months old. Research indicates that maternal vaccination with Abrysvo can reduce severe RSV illness in infants by 91% [162]. Common side effects reported in pregnant women receiving the vaccine include pain at the injection site, headache, muscle pain, and nausea. While clinical trials showed a slightly higher rate of preterm births in the vaccine group compared to placebo, this difference was not statistically significant [163]. The introduction of the RSV vaccine for pregnant women is expected to have a significant public health impact by decreasing RSV-related hospitalizations and medical visits, thereby improving neonatal outcomes and reducing the strain on healthcare systems during peak RSV seasons. This authorization represents a pivotal advancement in maternal and neonatal health. Continued surveillance and research will be crucial to monitor the long-term benefits and potential risks associated with maternal RSV vaccination.

Vaccines play a vital role in protecting pregnant populations from viral infections. Excluding pregnant women from vaccine safety and efficacy trials poses risks, including the lack of evidence-based guidance, disparities in care and outcomes, missed opportunities for data collection, ethical concerns, and implications for healthcare workers. Addressing these risks is crucial to ensure equitable access to potentially life-saving interventions during public health emergencies [164]. By addressing challenges through tailored vaccine development, robust regulatory oversight, safety monitoring, and epidemiological insights, we can optimize vaccine strategies to safeguard the health of pregnant women and their infants.

6. Future Considerations

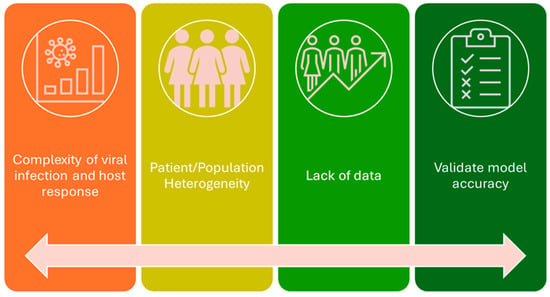

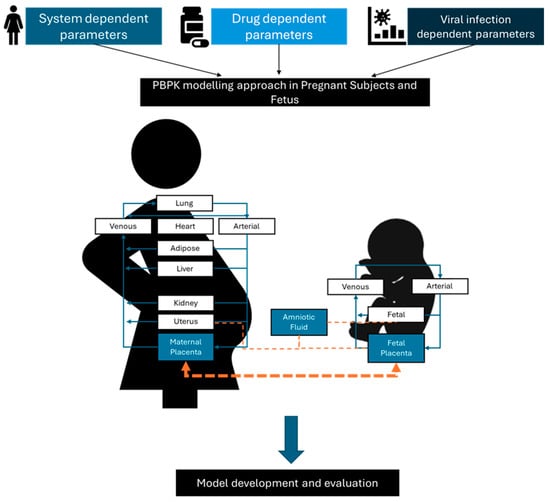

Significant strides have been made in understanding antiviral therapy for pregnant women, but further efforts are needed to combat future pandemics and control viral infections by 2030. Ongoing research aims to address ethical drug experimentation and the pharmacokinetics, metabolism, and pharmacological effects of pregnancy to improve care and save lives during outbreaks. To accelerate progress, preclinical studies should be completed earlier, and under certain conditions, pregnant women could be included in phase III trials to obtain crucial safety and efficacy data sooner. Traditionally excluded from clinical trials, pregnant women need to be included with appropriate safeguards to close the data gap on drug safety and efficacy. There is a pressing need for accurate models of human pregnancy, considering the combined effects of pregnancy and other health conditions on physiological changes. Integrating viral infection dynamics into modeling efforts, such as PBPK modeling, shows promise for future research. Our research group is promoting this approach [208,209,233,234,235,236,237,238,239,240]. By refining these models with more data and incorporating viral dynamics, we can optimize antiviral therapy for pregnant women. Challenges include validating PBPK models and addressing gaps in system models, but opportunities lie in simulating outcomes in clinical studies, establishing registries, and informing individualized dosing decisions. In summary, while there are challenges in integrating viral infection dynamics into PBPK modeling, there are also significant opportunities to enhance our understanding of antiviral therapy for pregnant women. Continued research holds promise for developing tailored therapeutic strategies to meet the unique needs of pregnant individuals and improve treatment outcomes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.V.; methodology, B.C. and M.J.G.; formal analysis, B.C.; M.J.G. and N.V.; investigation, B.C.; writing—original draft preparation, B.C.; writing—review and editing, M.J.G. and N.V.; supervision, N.V.; project administration, N.V.; funding acquisition, N.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financed by Fundo Europeu de Desenvolvimento Regional (FEDER) funds through the COMPETE 2020 Operational Programme for Competitiveness and Internationalisation (POCI), Portugal 2020, and by Portuguese funds through Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT) in the framework of projects IF/00092/2014/CP1255/CT0004 and CHAIR in Onco-Innovation from the Faculty of Medicine, University of Porto (FMUP).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mitchell, A.A.; Gilboa, S.M.; Werler, M.M.; Kelley, K.E.; Louik, C.; Hernández-Díaz, S. Medication Use during Pregnancy, with Particular Focus on Prescription Drugs: 1976–2008. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 51.e1–51.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesley, B.D.; Sewell, C.A.; Chang, C.Y.; Hatfield, K.P.; Nguyen, C.P. Prescription Medications for Use in Pregnancy–Perspective from the US Food and Drug Administration. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 225, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control. Research on Medicines and Pregnancy. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/medicine-and-pregnancy/research/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy/meds/treatingfortwo/research.html (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Werler, M.M.; Kerr, S.M.; Ailes, E.C.; Reefhuis, J.; Gilboa, S.M.; Browne, M.L.; Kelley, K.E.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Smith-Webb, R.S.; Garcia, M.H.; et al. Patterns of Prescription Medication Use during the First Trimester of Pregnancy in the United States, 1997–2018. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 114, 836–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desaunay, P.; Eude, L.-G.; Dreyfus, M.; Alexandre, C.; Fedrizzi, S.; Alexandre, J.; Uguz, F.; Guénolé, F. Benefits and Risks of Antidepressant Drugs During Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Meta-Analyses. Pediatr. Drugs 2023, 25, 247–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramanian, A.; Azcoaga-Lorenzo, A.; Anand, A.; Phillips, K.; Lee, S.I.; Cockburn, N.; Fagbamigbe, A.F.; Damase-Michel, C.; Yau, C.; McCowan, C.; et al. Polypharmacy during Pregnancy and Associated Risk Factors: A Retrospective Analysis of 577 Medication Exposures among 1.5 Million Pregnancies in the UK, 2000–2019. BMC Med. 2023, 21, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macklin, R. Enrolling Pregnant Women in Biomedical Research. Lancet 2010, 375, 632–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, K.E.; Lyerly, A.D. Exclusion of Pregnant Women From Industry-Sponsored Clinical Trials. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 122, 1077–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guinn, D.; Sahin, L.; Fletcher, E.P.; Choi, S.; Johnson, T.; Dinatale, M.; Baisden, K.; Sun, W.; Pillai, V.C.; Morales, J.P.; et al. Pharmacokinetic Evaluation in Pregnancy—Current Status and Future Considerations: Workshop Summary. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 63, S7–S17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaphekar, N.; Dodeja, P.; Shaik, I.H.; Caritis, S.; Venkataramanan, R. Maternal-Fetal Pharmacology of Drugs: A Review of Current Status of the Application of Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Models. Front. Pediatr. 2021, 9, 733823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, P.; Patel, B.; Patel, B. Drug Use in Pregnancy; a Point to Ponder! Indian J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 71, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKiever, M.; Frey, H.; Costantine, M.M. Challenges in Conducting Clinical Research Studies in Pregnant Women. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2020, 47, 287–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feghali, M.; Venkataramanan, R.; Caritis, S. Pharmacokinetics of Drugs in Pregnancy. Semin. Perinatol. 2015, 39, 512–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantine, M.M. Physiologic and Pharmacokinetic Changes in Pregnancy. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheffield, J.S.; Siegel, D.; Mirochnick, M.; Heine, R.P.; Nguyen, C.; Bergman, K.L.; Savic, R.M.; Long, J.; Dooley, K.E.; Nesin, M. Designing Drug Trials: Considerations for Pregnant Women. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2014, 59, S437–S444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.A.; Cragan, J.D.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Schulkin, J. Obstetrician–Gynaecologist Knowledge of and Access to Information about the Risks of Medication Use during Pregnancy. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010, 23, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M.M.; Amoozegar, J.B.; McClure, E.M.; Squiers, L.B.; Broussard, C.S.; Lind, J.N.; Polen, K.N.; Frey, M.T.; Gilboa, S.M.; Biermann, J. Improving Safe Use of Medications During Pregnancy: The Roles of Patients, Physicians, and Pharmacists. Qual. Health Res. 2017, 27, 2071–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic Model Informed Framework to Prioritize Drugs to Be Studied in Pregnant Population. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/science-research/advancing-regulatory-science/physiologically-based-pharmacokinetic-model-informed-framework-prioritize-drugs-be-studied-pregnant (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Pariente, G.; Leibson, T.; Carls, A.; Adams-Webber, T.; Ito, S.; Koren, G. Pregnancy-Associated Changes in Pharmacokinetics: A Systematic Review. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, A.C.; Gebreyohannes, R.D.; Fernandes, M.F.S.; Pillai, V.C. Physiologic Changes During Pregnancy and Impact on Small-Molecule Drugs, Biologic (Monoclonal Antibody) Disposition, and Response. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 63, S34–S50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, R.E.; Metz, T.D.; Ward, R.M.; McKnite, A.M.; Enioutina, E.Y.; Sherwin, C.M.; Watt, K.M.; Job, K.M. Drug Exposure during Pregnancy: Current Understanding and Approaches to Measure Maternal-Fetal Drug Exposure. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1111601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Hu, X.; Cao, B. Viral Infections During Pregnancy: The Big Challenge Threatening Maternal and Fetal Health. Matern. Fetal Med. 2022, 4, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Saadaoui, M.; Al Khodor, S. Infections and Pregnancy: Effects on Maternal and Child Health. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 873253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beltrami, S.; Rizzo, S.; Schiuma, G.; Speltri, G.; Di Luca, D.; Rizzo, R.; Bortolotti, D. Gestational Viral Infections: Role of Host Immune System. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, A.C.; Mirochnick, M.; Lockman, S. Antiretroviral Therapy and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes in People Living with HIV. N. Engl. J. Med. 2023, 388, 344–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auriti, C.; De Rose, D.U.; Santisi, A.; Martini, L.; Piersigilli, F.; Bersani, I.; Ronchetti, M.P.; Caforio, L. Pregnancy and Viral Infections: Mechanisms of Fetal Damage, Diagnosis and Prevention of Neonatal Adverse Outcomes from Cytomegalovirus to SARS-CoV-2 and Zika Virus. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerveny, L.; Murthi, P.; Staud, F. HIV in Pregnancy: Mother-to-Child Transmission, Pharmacotherapy, and Toxicity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) Mol. Basis Dis. 2021, 1867, 166206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westin, A.A.; Reimers, A.; Spigset, O. Should Pregnant Women Receive Lower or Higher Medication Doses? Tidsskr. Nor. Legeforening 2018, 138, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregnancy: Diagnosis, Physiology, and Care. Available online: https://www.lecturio.com/concepts/pregnancy-diagnosis-maternal-physiology-and-routine-care/ (accessed on 3 May 2024).

- Gallo, R.C.; Montagnier, L. The Chronology of AIDS Research. Nature 1987, 326, 435–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoye, A.A.; Picker, L.J. CD4+ T Cell Depletion in HIV Infection: Mechanisms of Immunological Failure. Immunol. Rev. 2013, 254, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, D.N.; Vieira, N.; Hønge, B.L.; da Silva Té, D.; Jespersen, S.; Bjerregaard-Andersen, M.; Oliveira, I.; Furtado, A.; Gomes, M.A.; Sodemann, M.; et al. HIV-1 and HIV-2 Prevalence, Risk Factors and Birth Outcomes among Pregnant Women in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Hospital Study. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 12174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, C.C.; Ellington, S.R.; Kourtis, A.P. The Role of Co-Infections in Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV. Curr. HIV Res. 2013, 11, 10–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo-Giang-Huong, N.; Khamduang, W.; Leurent, B.; Collins, I.; Nantasen, I.; Leechanachai, P.; Sirirungsi, W.; Limtrakul, A.; Leusaree, T.; Comeau, A.M.; et al. Early HIV-1 Diagnosis Using In-House Real-Time PCR Amplification on Dried Blood Spots for Infants in Remote and Resource-Limited Settings. JAIDS J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2008, 49, 465–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochodo, E.A.; Guleid, F.; Deeks, J.J.; Mallett, S. Point-of-Care Tests Detecting HIV Nucleic Acids for Diagnosis of HIV-1 or HIV-2 Infection in Infants and Children Aged 18 Months or Less. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2021, 2021, CD013207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikumi, N.M.; Matjila, M. Preterm Birth in Women With HIV: The Role of the Placenta. Front. Glob. Womens Health 2022, 3, 820759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindle, S.; Brien, M.-È.; Pelletier, F.; Giguère, F.; Trudel, M.J.; Dal Soglio, D.; Kakkar, F.; Soudeyns, H.; Girard, S.; Boucoiran, I. Placenta Analysis of Hofbauer Cell Profile According to the Class of Antiretroviral Therapy Used during Pregnancy in People Living with HIV. Placenta 2023, 139, 120–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, O.; Powers, J.; Bricker, K.M.; Chahroudi, A. Understanding Viral and Immune Interplay During Vertical Transmission of HIV: Implications for Cure. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 757400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleton, J.S.; Nagalli, S. Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART); StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Demas, P.A.; Thea, D.M.; Weedon, J.; McWayne, J.; Bamji, M.; Lambert, G.; Schoenbaum, E.E. Adherence to Zidovudine for the Prevention of Perinatal Transmission in HIV-Infected Pregnant Women: The Impact of Social Network Factors, Side Effects, and Perceived Treatment Efficacy. Women Health 2005, 42, 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabi, F.; Karamouzian, M.; Farhoudi, B.; Moradi Falah Langeroodi, S.; Mehmandoost, S.; Abbaszadeh, S.; Motaghi, S.; Mirzazadeh, A.; Sadeghirad, B.; Sharifi, H. Comparison of Safety and Effectiveness of Antiretroviral Therapy Regimens among Pregnant Women Living with HIV at Preconception or during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dunkelberg, J.C.; Berkley, E.M.F.; Thiel, K.W.; Leslie, K.K. Hepatitis B and C in Pregnancy: A Review and Recommendations for Care. J. Perinatol. 2014, 34, 882–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.-M.; Cui, Y.-T.; Wang, L.; Yang, H.; Liang, Z.-Q.; Li, X.-M.; Zhang, S.-L.; Qiao, F.-Y.; Campbell, F.; Chang, C.-N.; et al. Lamivudine in Late Pregnancy to Prevent Perinatal Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection: A Multicentre, Randomized, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. J. Viral Hepat. 2009, 16, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Yan, Y.; Choi, B.C.K.; Xu, J.; Men, K.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wang, F. Risk Factors and Mechanism of Transplacental Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus: A Case-control Study. J. Med. Virol. 2002, 67, 20–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.-H. Global Prevalence of Hepatitis B Virus Infection and Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 3, 598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navabakhsh, B.; Mehrabi, N.; Estakhri, A.; Mohamadnejad, M.; Poustchi, H. Hepatitis B Virus Infection during Pregnancy: Transmission and Prevention. Middle East J. Dig. Dis. 2011, 3, 92–102. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, K.W.; Lao, T.T.-H. Hepatitis B—Vertical Transmission and the Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2020, 68, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Bai, X.; Xi, Y. Intrauterine Infection and Mother-to-Child Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus: Route and Molecular Mechanism. Infect. Drug Resist. 2022, 15, 1743–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Hang, L.; Zhong, M.; Gao, Y.; Luo, M.; Yu, Y. Maternal HCV Infection Is Associated with Intrauterine Fetal Growth Disturbance. Medicine 2016, 95, e4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pembrey, L.; Newell, M.-L.; Tovo, P.-A.; The EPHN Collaborators. The Management of HCV Infected Pregnant Women and Their Children European Paediatric HCV Network. J. Hepatol. 2005, 43, 515–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babik, J.M.; Cohan, D.; Monto, A.; Hartigan-O’Connor, D.J.; McCune, J.M. The Human Fetal Immune Response to Hepatitis C Virus Exposure in Utero. J. Infect. Dis. 2011, 203, 196–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Molin, G.; D’Agaro, P.; Ansaldi, F.; Ciana, G.; Fertz, C.; Alberico, S.; Campello, C. Mother-to-infant Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus: Rate of Infection and Assessment of Viral Load and IgM Anti-HCV as Risk Factors*. J. Med. Virol. 2002, 67, 137–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Shabrawi, M.H.F.; Kamal, N.M.; Mogahed, E.A.; Elhusseini, M.A.; Aljabri, M.F. Perinatal Transmission of Hepatitis C Virus: An Update. Arch. Med. Sci. 2020, 16, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashida, A.; Inaba, N.; Oshima, K.; Nishikawa, M.; Shoda, A.; Hayashida, S.; Negishi, M.; Inaba, F.; Inaba, M.; Fukasawa, I.; et al. Re-evaluation of the True Rate of Hepatitis C Virus Mother-to-child Transmission and Its Novel Risk Factors Based on Our Two Prospective Studies. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2007, 33, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, R.; Heiden, M.; Offergeld, R.; Burger, R. Influenza Virus. Transfus. Med. Hemother. 2009, 36, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Study Finds Influenza during Pregnancy Is Associated with Increased Risk of Pregnancy Loss and Reduced Birthweight. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/2020-2021/influenza-pregnancy-loss.htm (accessed on 29 April 2024).

- Gozde Kanmaz, H.; Erdeve, O.; Suna Oğz, S.; Uras, N.; Çelen, Ş.; Korukluoglu, G.; Zergeroglu, S.; Kara, A.; Dilmen, U. Placental Transmission of Novel Pandemic Influenza a Virus. Fetal Pediatr. Pathol. 2011, 30, 280–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappenfield, E.; Jamieson, D.J.; Kourtis, A.P. Pregnancy and Susceptibility to Infectious Diseases. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 2013, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giri, T.; Panda, S.; Kelly, J.C.; Pancaro, C.; Palanisamy, A. Upregulated Influenza A Viral Entry Factors and Enhanced Interferon-Alpha Response in the Nasal Epithelium of Pregnant Rats. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weckman, A.M.; Ngai, M.; Wright, J.; McDonald, C.R.; Kain, K.C. The Impact of Infection in Pregnancy on Placental Vascular Development and Adverse Birth Outcomes. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oseghale, O.; Vlahos, R.; O’Leary, J.J.; Brooks, R.D.; Brooks, D.A.; Liong, S.; Selemidis, S. Influenza Virus Infection during Pregnancy as a Trigger of Acute and Chronic Complications. Viruses 2022, 14, 2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Fatemi, S.H.; Sidwell, R.W.; Patterson, P.H. Maternal Influenza Infection Causes Marked Behavioral and Pharmacological Changes in the Offspring. J. Neurosci. 2003, 23, 297–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liong, S.; Oseghale, O.; To, E.E.; Brassington, K.; Erlich, J.R.; Luong, R.; Liong, F.; Brooks, R.; Martin, C.; O’Toole, S.; et al. Influenza A Virus Causes Maternal and Fetal Pathology via Innate and Adaptive Vascular Inflammation in Mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 24964–24973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, B.H.; Mahmood, T.A. Influenza A H1N1 2009 (Swine Flu) and Pregnancy. J. Obstet. Gynecol. India 2011, 61, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopatynsky-Reyes, E.Z.; Chacon-Cruz, E.; Greenberg, M.; Clemens, R.; Costa Clemens, S.A. Influenza Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Descriptive Study of the Knowledge, Beliefs, and Practices of Mexican Gynecologists and Family Physicians. Vaccines 2023, 11, 1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvin, A.; Campadelli-Fiume, G.; Mocarski, E.; Moore, P.S. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; ISBN 9780521827140. [Google Scholar]

- Gugliesi, F.; Coscia, A.; Griffante, G.; Galitska, G.; Pasquero, S.; Albano, C.; Biolatti, M. Where Do We Stand after Decades of Studying Human Cytomegalovirus? Microorganisms 2020, 8, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.; Anderson, B.; Pass, R.F. Prevention of Maternal and Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 55, 521–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Shoham, A.; Schlesinger, Y.; Miskin, I.; Kalderon, Z.; Michaelson-Cohen, R.; Wiener-Well, Y. Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Seroprevalence among Women at Childbearing Age, Maternal and Congenital CMV Infection: Policy Implications of a Descriptive, Retrospective, Community-Based Study. Isr. J. Health Policy Res. 2023, 12, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Britt, W. Maternal Immunity and the Natural History of Congenital Human Cytomegalovirus Infection. Viruses 2018, 10, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Njue, A.; Coyne, C.; Margulis, A.V.; Wang, D.; Marks, M.A.; Russell, K.; Das, R.; Sinha, A. The Role of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection in Adverse Birth Outcomes: A Review of the Potential Mechanisms. Viruses 2020, 13, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pereira, L.; Petitt, M.; Tabata, T. Cytomegalovirus Infection and Antibody Protection of the Developing Placenta. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57 (Suppl. S4), S174–S177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Schleiss, M.R. Congenital Cytomegalovirus: Impact on Child Health. Contemp. Pediatr. 2018, 35, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kabani, N.; Ross, S.A. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, S9–S14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rawlinson, W.D.; Boppana, S.B.; Fowler, K.B.; Kimberlin, D.W.; Lazzarotto, T.; Alain, S.; Daly, K.; Doutré, S.; Gibson, L.; Giles, M.L.; et al. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy and the Neonate: Consensus Recommendations for Prevention, Diagnosis, and Therapy. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, e177–e188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leber, A.L. Maternal and Congenital Human Cytomegalovirus Infection: Laboratory Testing for Detection and Diagnosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2024, 62, e00313-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zammarchi, L.; Lazzarotto, T.; Andreoni, M.; Campolmi, I.; Pasquini, L.; Di Tommaso, M.; Simonazzi, G.; Tomasoni, L.R.; Castelli, F.; Galli, L.; et al. Management of Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy: Is It Time for Valacyclovir? Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2020, 26, 1151–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rybak-Krzyszkowska, M.; Górecka, J.; Huras, H.; Massalska-Wolska, M.; Staśkiewicz, M.; Gach, A.; Kondracka, A.; Staniczek, J.; Górczewski, W.; Borowski, D.; et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy Prevention and Treatment Options: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Viruses 2023, 15, 2142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nigro, G.; Muselli, M. Prevention of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: Review and Case Series of Valaciclovir versus Hyperimmune Globulin Therapy. Viruses 2023, 15, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sartori, P.; Baud, D.; de Tejada, B.M.; Farin, A.; Rossier, M.-C.; Rieder, W.; Rouiller, S.; Robyr, R.; Grant, G.; Eggel, B.; et al. Cytomegalovirus Infection during Pregnancy: Cross-Sectional Survey of Knowledge and Prevention Practices of Healthcare Professionals in French-Speaking Switzerland. Virol. J. 2024, 21, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greye, H.; Henning, S.; Freese, K.; Köhn, A.; Lux, A.; Radusch, A.; Redlich, A.; Schleef, D.; Seeger, S.; Thäle, V.; et al. Cross-Sectional Study to Assess Awareness of Cytomegalovirus Infection among Pregnant Women in Germany. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyholm, J.L.; Schleiss, M.R. Schleiss Prevention of Maternal Cytomegalovirus Infection: Current Status and Future Prospects. Int. J. Womens Health 2010, 2, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Paules, C.I.; Marston, H.D.; Fauci, A.S. Coronavirus Infections—More Than Just the Common Cold. JAMA 2020, 323, 707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Berhanu, G.; Desalegn, C.; Kandi, V. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): An Update. Cureus 2020, 12, e7423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponprabha, R.; Thiagarajan, S.; Balamurugesan, K.; Davis, P. A Clinical Retrospective Study on the Transmission of COVID-19 From Mothers to Their Newborn and Its Outcome. Cureus 2022, 14, e20963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olivini, N.; Calò Carducci, F.I.; Santilli, V.; De Ioris, M.A.; Scarselli, A.; Alario, D.; Geremia, C.; Lombardi, M.H.; Marabotto, C.; Mariani, R.; et al. A Neonatal Cluster of Novel Coronavirus Disease 2019: Clinical Management and Considerations. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2020, 46, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moza, A.; Duica, F.; Antoniadis, P.; Bernad, E.S.; Lungeanu, D.; Craina, M.; Bernad, B.C.; Paul, C.; Muresan, C.; Nitu, R.; et al. Outcome of Newborns with Confirmed or Possible SARS-CoV-2 Vertical Infection—A Scoping Review. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, Y.P.; Tan, G.C.; Omar, S.Z.; Mustangin, M.; Singh, Y.; Salker, M.S.; Abd Aziz, N.H.; Shafiee, M.N. SARS-CoV-2 Infection in Pregnancy: Placental Histomorphological Patterns, Disease Severity and Perinatal Outcomes. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celik, E.; Vatansever, C.; Ozcan, G.; Kapucuoglu, N.; Alatas, C.; Besli, Y.; Palaoglu, E.; Gursoy, T.; Manici, M.; Turgal, M.; et al. Placental Deficiency during Maternal SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Placenta 2022, 117, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Flores, V.; Romero, R.; Xu, Y.; Theis, K.R.; Arenas-Hernandez, M.; Miller, D.; Peyvandipour, A.; Bhatti, G.; Galaz, J.; Gershater, M.; et al. Maternal-Fetal Immune Responses in Pregnant Women Infected with SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBolt, C.A.; Bianco, A.; Limaye, M.A.; Silverstein, J.; Penfield, C.A.; Roman, A.S.; Rosenberg, H.M.; Ferrara, L.; Lambert, C.; Khoury, R.; et al. Pregnant Women with Severe or Critical Coronavirus Disease 2019 Have Increased Composite Morbidity Compared with Nonpregnant Matched Controls. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 224, 510.e1–510.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novillo, B.; Martínez-Varea, A. COVID-19 Vaccines during Pregnancy and Breastfeeding: A Systematic Review. J. Pers. Med. 2022, 13, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Racicot, K.; Mor, G. Risks Associated with Viral Infections during Pregnancy. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 1591–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Recommendations for the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs During Pregnancy. Available online: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines/perinatal/recommendations-arv-drugs-pregnancy-overview#:~:text=Overview,-Panel’s%20Recommendations&text=All%20pregnant%20people%20with%20HIV,and%20sexual%20transmission%20(AI) (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Rasi, V.; Peters, H.; Sconza, R.; Francis, K.; Bukasa, L.; Thorne, C.; Cortina-Borja, M. Trends in Antiretroviral Use in Pregnancy in the UK and Ireland, 2008–2018. HIV Med. 2022, 23, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musanhu, C.C.C.; Takarinda, K.C.; Shea, J.; Chitsike, I.; Eley, B. Viral Load Testing among Pregnant Women Living with HIV in Mutare District of Manicaland Province, Zimbabwe. AIDS Res. Ther. 2022, 19, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassinou, L.C.; Songwa Nkeunang, D.; Delvaux, T.; Nagot, N.; Kirakoya-Samadoulougou, F. Adherence to Option B + Antiretroviral Therapy and Associated Factors in Pregnant and Breastfeeding Women in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huntington, S.E.; Bansi, L.K.; Thorne, C.; Anderson, J.; Newell, M.-L.; Taylor, G.P.; Pillay, D.; Hill, T.; Tookey, P.A.; Sabin, C.A. Treatment Switches during Pregnancy among HIV-Positive Women on Antiretroviral Therapy at Conception. AIDS 2011, 25, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, E.G.; Gendelman, H.E.; Bade, A.N. HIV-1 Integrase Strand Transfer Inhibitors and Neurodevelopment. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilleece, D.Y.; Tariq, D.S.; Bamford, D.A.; Bhagani, D.S.; Byrne, D.L.; Clarke, D.E.; Clayden, M.P.; Lyall, D.H.; Metcalfe, D.R.; Palfreeman, D.A.; et al. British HIV Association Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Pregnancy and Postpartum 2018. HIV Med. 2019, 20, S2–S85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taramasso, L.; Bovis, F.; Di Biagio, A.; Mignone, F.; Giaquinto, C.; Tagliabue, C.; Giacomet, V.; Genovese, O.; Chiappini, E.; Salomè, S.; et al. Intrapartum Use of Zidovudine in a Large Cohort of Pregnant Women Living with HIV in Italy. J. Infect. 2022, 85, 565–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lockman, S.; Brummel, S.S.; Ziemba, L.; Stranix-Chibanda, L.; McCarthy, K.; Coletti, A.; Jean-Philippe, P.; Johnston, B.; Krotje, C.; Fairlie, L.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Dolutegravir with Emtricitabine and Tenofovir Alafenamide Fumarate or Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate, and Efavirenz, Emtricitabine, and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate HIV Antiretroviral Therapy Regimens Started in Pregnancy (IMPAACT 2010/VESTED): A Multicentre, Open-Label, Randomised, Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 1276–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thimm, M.A.; Livingston, A.; Ramroop, R.; Eke, A.C. Pregnancy Outcomes in Pregnant Women with HIV on Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate (TDF) Compared to Tenofovir Alafenamide (TAF). J. AIDS HIV Treat. 2022, 4, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Delicio, A.M.; Lajos, G.J.; Amaral, E.; Lopes, F.; Cavichiolli, F.; Myioshi, I.; Milanez, H. Adverse Effects of Antiretroviral Therapy in Pregnant Women Infected with HIV in Brazil from 2000 to 2015: A Cohort Study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tukei, V.J.; Hoffman, H.J.; Greenberg, L.; Thabelo, R.; Nchephe, M.; Mots’oane, T.; Masitha, M.; Chabela, M.; Mokone, M.; Mofenson, L.; et al. Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes Among HIV-Positive Women in the Era of Universal Antiretroviral Therapy Remain Elevated Compared With HIV-Negative Women. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2021, 40, 821–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avulakunta, I.; Balasundaram, P.; Rechnitzer, A.; Morgan-Joseph, T.; Nafday, S. A Improving Birth-Dose Hepatitis-B Vaccination in a Tertiary Level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit. Pediatr. Qual. Saf. 2023, 8, e693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, A.; Yuen, L.; Jackson, K.M.; Manoharan, S.; Glass, A.; Maley, M.; Yoo, W.; Hong, S.P.; Kim, S.-O.; Luciani, F.; et al. Short Duration of Lamivudine for the Prevention of Hepatitis B Virus Transmission in Pregnancy: Lack of Potency and Selection of Resistance Mutations. J. Viral Hepat. 2014, 21, 809–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.-H. Tenofovir Rescue Therapy in Pregnant Females with Chronic Hepatitis B. World J. Gastroenterol. 2015, 21, 2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dionne-Odom, J.; Cozzi, G.D.; Franco, R.A.; Njei, B.; Tita, A.T.N. Treatment and Prevention of Viral Hepatitis in Pregnancy. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 335–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Q.; Liu, H.; Tang, L.; Wang, F.; Tolufashe, G.; Chang, J.; Guo, J.-T. Mechanism of Interferon Alpha Therapy for Chronic Hepatitis B and Potential Approaches to Improve Its Therapeutic Efficacy. Antivir. Res. 2024, 221, 105782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.W.; Lee, J.S.; Ahn, S.H. Hepatitis B Virus Cure: Targets and Future Therapies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 22, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Quadeer, A.A.; McKay, M.R. Direct-Acting Antiviral Resistance of Hepatitis C Virus Is Promoted by Epistasis. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 7457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freriksen, J.J.M.; van Seyen, M.; Judd, A.; Gibb, D.M.; Collins, I.J.; Greupink, R.; Russel, F.G.M.; Drenth, J.P.H.; Colbers, A.; Burger, D.M. Review Article: Direct-acting Antivirals for the Treatment of HCV during Pregnancy and Lactation—Implications for Maternal Dosing, Foetal Exposure, and Safety for Mother and Child. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2019, 50, 738–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, N.; Hiebert, L.; Armstrong, P.A.; Wester, C.; Ward, J.W. Hepatitis C in Pregnancy and the TiP-HepC Registry. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2022, 7, 598–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Recommendations for Obstetric Health Care Providers Related to Use of Antiviral Medications in the Treatment and Prevention of Influenza. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/antivirals/avrec_ob.htm#:~:text=For%20treatment%20of%20pregnant%20people,with%20oseltamivir%20is%205%20days (accessed on 1 May 2024).

- Goodrich, J.M. Ganciclovir Prophylaxis To Prevent Cytomegalovirus Disease after Allogeneic Marrow Transplant. Ann. Intern. Med. 1993, 118, 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Santis, M.; Apicella, M.; De Luca, C.; D’Oria, L.; Valentini, P.; Sanguinetti, M.; Lanzone, A.; Scambia, G.; Santangelo, R.; Masini, L. Valacyclovir in Primary Maternal CMV Infection for Prevention of Vertical Transmission: A Case-Series. J. Clin. Virol. 2020, 127, 104351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contejean, A.; Leruez-Ville, M.; Treluyer, J.-M.; Tsatsaris, V.; Ville, Y.; Charlier, C.; Chouchana, L. Assessing the Risk of Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes and Birth Defects Reporting in Women Exposed to Ganciclovir or Valganciclovir during Pregnancy: A Pharmacovigilance Study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2023, 78, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahar-Nissan, K.; Pardo, J.; Peled, O.; Krause, I.; Bilavsky, E.; Wiznitzer, A.; Hadar, E.; Amir, J. Valaciclovir to Prevent Vertical Transmission of Cytomegalovirus after Maternal Primary Infection during Pregnancy: A Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Lancet 2020, 396, 779–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leruez-Ville, M.; Ghout, I.; Bussières, L.; Stirnemann, J.; Magny, J.-F.; Couderc, S.; Salomon, L.J.; Guilleminot, T.; Aegerter, P.; Benoist, G.; et al. In Utero Treatment of Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection with Valacyclovir in a Multicenter, Open-Label, Phase II Study. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2016, 215, 462.e1–462.e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G.; Torre, R.L.; Pentimalli, H.; Taverna, P.; Lituania, M.; de Tejada, B.M.; Adler, S.P. Regression of Fetal Cerebral Abnormalities by Primary Cytomegalovirus Infection Following Hyperimmunoglobulin Therapy. Prenat. Diagn. 2008, 28, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G.; Adler, S.P.; Gatta, E.; Mascaretti, G.; Megaloikonomou, A.; Torre, R.L.; Necozione, S. Fetal Hyperechogenic Bowel May Indicate Congenital Cytomegalovirus Disease Responsive to Immunoglobulin Therapy. J. Matern. Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012, 25, 2202–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiaie, L.D.; Neuberger, P.; Vochem, M.; Lihs, A.; Karck, U.; Enders, M. No Evidence of Obstetrical Adverse Events after Hyperimmune Globulin Application for Primary Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnancy: Experience from a Single Centre. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 297, 1389–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seidel, V.; Hackelöer, M.; Rancourt, R.C.; Henrich, W.; Siedentopf, J.-P. Fetal and Maternal Outcome after Hyperimmunoglobulin Administration for Prevention of Maternal–Fetal Transmission of Cytomegalovirus during Pregnancy: Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 302, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nigro, G.; Adler, S.P.; Lasorella, S.; Iapadre, G.; Maresca, M.; Mareri, A.; Di Paolantonio, C.; Catenaro, M.; Tambucci, R.; Mattei, I.; et al. High-Dose Cytomegalovirus (CMV) Hyperimmune Globulin and Maternal CMV DNAemia Independently Predict Infant Outcome in Pregnant Women With a Primary CMV Infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 1491–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adler, S.P. Screening for Cytomegalovirus during Pregnancy. Infect. Dis. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 2011, 942937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salomè, S.; Corrado, F.R.; Mazzarelli, L.L.; Maruotti, G.M.; Capasso, L.; Blazquez-Gamero, D.; Raimondi, F. Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection: The State of the Art and Future Perspectives. Front. Pediatr. 2023, 11, 1276912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandiwana, N.C.; Siedner, M.J.; Marconi, V.C.; Hill, A.; Ali, M.K.; Batterham, R.L.; Venter, W.D.F. Weight Gain After HIV Therapy Initiation: Pathophysiology and Implications. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2024, 109, e478–e487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choodinatha, H.K.; Jeon, M.R.; Choi, B.Y.; Lee, K.-N.; Kim, H.J.; Park, J.Y. Cytomegalovirus Infection during Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. Sci. 2023, 66, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arbabzadeh, T.; Masoumi Shahrbabak, M.; Pooransari, P.; Khatuni, M.; Mirzamoradi, M.; Saleh Gargari, S.; Naeiji, Z.; Rahmati, N.; Omidi, S.; Ebrahimi Meimand, F. Remdesivir in Pregnant Women with Moderate to Severe Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): A Retrospective Cohort Study. Clin. Exp. Med. 2023, 23, 3709–3717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budi, D.S.; Pratama, N.R.; Wafa, I.A.; Putra, M.; Wardhana, M.P.; Wungu, C.D.K. Remdesivir for Pregnancy: A Systematic Review of Antiviral Therapy for COVID-19. Heliyon 2022, 8, e08835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, S.; Metzendorf, M.-I.; Kuehn, R.; Popp, M.; Gagyor, I.; Kranke, P.; Meybohm, P.; Skoetz, N.; Weibel, S. Nirmatrelvir Combined with Ritonavir for Preventing and Treating COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2023, 2023, CD015395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crispino, P.; Marocco, R.; Di Trento, D.; Guarisco, G.; Kertusha, B.; Carraro, A.; Corazza, S.; Pane, C.; Di Troia, L.; del Borgo, C.; et al. Use of Monoclonal Antibodies in Pregnant Women Infected by COVID-19: A Case Series. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magala Ssekandi, A.; Sserwanja, Q.; Olal, E.; Kawuki, J.; Bashir Adam, M. Corticosteroids Use in Pregnant Women with COVID-19: Recommendations from Available Evidence. J. Multidiscip. Healthc. 2021, 14, 659–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- SeyedAlinaghi, S.; Mirzapour, P.; Pashaei, Z.; Afzalian, A.; Tantuoyir, M.M.; Salmani, R.; Maroufi, S.F.; Paranjkhoo, P.; Maroufi, S.P.; Badri, H.; et al. The Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic on Service Delivery and Treatment Outcomes in People Living with HIV: A Systematic Review. AIDS Res. Ther. 2023, 20, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, A.; Mullin, S.; Chapman, S.; Barnard, K.; Bakhbakhi, D.; Ion, R.; Neuberger, F.; Standing, J.; Merriel, A.; Fraser, A.; et al. Interventions to Enhance Medication Adherence in Pregnancy- a Systematic Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2023, 23, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eke, A.C. Adherence Predictors in Pregnant Women Living with HIV on Tenofovir Alafenamide and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate. J. Pharm. Drug. Res. 2022, 5, 585–593. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro, E.A.; Stika, C.S. Drugs in Pregnancy: Pharmacologic and Physiologic Changes That Affect Clinical Care. Semin. Perinatol. 2020, 44, 151221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Yang, H. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Pregnancy: Clinical Update and Perspective. Chin. Med. J. 2023, 136, 1891–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badell, M.L.; Dude, C.M.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Jamieson, D.J. COVID-19 Vaccination in Pregnancy. BMJ 2022, 378, e069741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santi Laurini, G.; Montanaro, N.; Motola, D. Safety of COVID-19 Vaccines in Pregnancy: A VAERS Based Analysis. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2023, 79, 657–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, P.; Dodi, I.; Esposito, S.; Indolfi, G. Prevention of Vertical Transmission of Hepatitis B Virus Infection. World J. Gastroenterol. 2021, 27, 4182–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, D.M.; Fell, D.; Garritty, C.; Hamel, C.; Butler, C.; Hersi, M.; Ahmadzai, N.; Rice, D.B.; Esmaeilisaraji, L.; Michaud, A.; et al. Safety of Influenza Vaccination during Pregnancy: A Systematic Review. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e066182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Muñoz, M.F.; Martín-Martín, C.; Kovacheva, K.; Olivares, M.E.; Izquierdo, N.; Pérez-Romero, P.; García-Ríos, E. Hygiene-Based Measures for the Prevention of Cytomegalovirus Infection in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dad, N.; Buhmaid, S.; Mulik, V. Vaccination in Pregnancy—The When, What and How? Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2021, 265, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, Z.; Greer, O.; Shah, N.M. Is the Host Viral Response and the Immunogenicity of Vaccines Altered in Pregnancy? Antibodies 2020, 9, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goswami, R.; Pavon, C.G.; Miller, I.G.; Berendam, S.J.; Williams, C.A.; Rosenthal, D.; Gross, M.; Phan, C.; Byrd, A.; Pollara, J.; et al. Prenatal Immunization to Prevent Viral Disease Outcomes During Pregnancy and Early Life. Front. Virol. 2022, 2, 849995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Vasan, S.; Kim, J.H.; Ake, J.A. Current Approaches to HIV Vaccine Development: A Narrative Review. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortner, A.; Bucur, O. MRNA-Based Vaccine Technology for HIV. Discoveries 2022, 10, e150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rech-Medeiros, A.F.; Marcon, P.d.S.; Tovo, C.d.V.; de Mattos, A.A. Evaluation of Response to Hepatitis B Virus Vaccine in Adults with Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Ann. Hepatol. 2019, 18, 725–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, L.; Kang, S.; Li, X.; Lu, L.; Liu, X.; Song, X.; Li, Y.; Li, X.; Lyu, W.; et al. Immune Responses to HBV Vaccine in People Living with HIV (PLWHs) Who Achieved Successful Treatment: A Prospective Cohort Study. Vaccines 2023, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McVoy, M.A. Cytomegalovirus Vaccines. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 57, S196–S199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Lanchy, J.-M.; Ryckman, B.J. Human Cytomegalovirus GH/GL/GO Promotes the Fusion Step of Entry into All Cell Types, Whereas GH/GL/UL128-131 Broadens Virus Tropism through a Distinct Mechanism. J. Virol. 2015, 89, 8999–9009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.Y.; McGregor, A. A Fully Protective Congenital CMV Vaccine Requires Neutralizing Antibodies to Viral Pentamer and GB Glycoprotein Complexes but a Pp65 T-Cell Response Is Not Necessary. Viruses 2021, 13, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuter, N.; Kropff, B.; Britt, W.; Mach, M.; Thomas, M. Neutralizing Antibodies Limit Cell-Associated Spread of Human Cytomegalovirus in Epithelial Cells and Fibroblasts. Viruses 2022, 14, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Lim, J.M.; Yu, B.; Song, S.; Neeli, P.; Sobhani, N.; K, P.; Bonam, S.R.; Kurapati, R.; Zheng, J.; et al. The Next-Generation DNA Vaccine Platforms and Delivery Systems: Advances, Challenges and Prospects. Front. Immunol. 2024, 15, 1332939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rosa, C.; Wang, Z.; Brewer, J.C.; Lacey, S.F.; Villacres, M.C.; Sharan, R.; Krishnan, R.; Crooks, M.; Markel, S.; Maas, R.; et al. Preclinical Development of an Adjuvant-Free Peptide Vaccine with Activity against CMV Pp65 in HLA Transgenic Mice. Blood 2002, 100, 3681–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharbanda, E.O.; Vazquez-Benitez, G. COVID-19 MRNA Vaccines During Pregnancy. JAMA 2022, 327, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorgensen, S.C.J.; Hernandez, A.; Fell, D.B.; Austin, P.C.; D’Souza, R.; Guttmann, A.; Brown, K.A.; Buchan, S.A.; Gubbay, J.B.; Nasreen, S.; et al. Maternal MRNA Covid-19 Vaccination during Pregnancy and Delta or Omicron Infection or Hospital Admission in Infants: Test Negative Design Study. BMJ 2023, 380, e074035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röbl-Mathieu, M.; Kunstein, A.; Liese, J.; Mertens, T.; Wojcinski, M. Vaccination in Pregnancy. Dtsch. Ärztebl. Int. 2021, 18, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trovato, M.; Sartorius, R.; D’Apice, L.; Manco, R.; De Berardinis, P. Viral Emerging Diseases: Challenges in Developing Vaccination Strategies. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 2130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleming-Dutra, K.E.; Jones, J.M.; Roper, L.E.; Prill, M.M.; Ortega-Sanchez, I.R.; Moulia, D.L.; Wallace, M.; Godfrey, M.; Broder, K.R.; Tepper, N.K.; et al. Use of the Pfizer Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine During Pregnancy for the Prevention of Respiratory Syncytial Virus–Associated Lower Respiratory Tract Disease in Infants: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, 2023. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2023, 72, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phijffer, E.W.; de Bruin, O.; Ahmadizar, F.; Bont, L.J.; Van der Maas, N.A.; Sturkenboom, M.C.; Wildenbeest, J.G.; Bloemenkamp, K.W. Respiratory syncytial virus vaccination during pregnancy for improving infant outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 5, CD015134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Spall, H.G.C. Exclusion of Pregnant and Lactating Women from COVID-19 Vaccine Trials: A Missed Opportunity. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 2724–2726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taskar, K.S.; Harada, I.; Alluri, R.V. Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modelling of Transporter Mediated Drug Absorption, Clearance and Drug-Drug Interactions. Curr. Drug. Metab. 2021, 22, 523–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathiesen, L.; Buerki-Thurnherr, T.; Pastuschek, J.; Aengenheister, L.; Knudsen, L.E. Fetal Exposure to Environmental Chemicals; Insights from Placental Perfusion Studies. Placenta 2021, 106, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Merdy, M.; Szeto, K.X.; Perrier, J.; Bolger, M.B.; Lukacova, V. PBPK Modeling Approach to Predict the Behavior of Drugs Cleared by Metabolism in Pregnant Subjects and Fetuses. Pharmaceutics 2024, 16, 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, G.; Joshi, J.; Mandal, R.S.; Shrivastava, N.; Virmani, R.; Sethi, T. Artificial Intelligence in Surveillance, Diagnosis, Drug Discovery and Vaccine Development against COVID-19. Pathogens 2021, 10, 1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syme, M.R.; Paxton, J.W.; Keelan, J.A. Drug Transfer and Metabolism by the Human Placenta. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2004, 43, 487–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mao, Q.; Chen, X. An Update on Placental Drug Transport and Its Relevance to Fetal Drug Exposure. Med. Rev. 2022, 2, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S.K.; Campbell, J.P. Placental Structure, Function and Drug Transfer. Contin. Educ. Anaesth. Crit. Care Pain 2015, 15, 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giaginis, C.; Tsantili-Kakoulidou, A.; Theocharis, S. Assessing Drug Transport Across the Human Placental Barrier: From In Vivo and In Vitro Measurements to the Ex Vivo Perfusion Method and In Silico Techniques. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2011, 12, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]