Abstract

Background. Causing approximately 8 million deaths each year, tobacco smoking represents a significant public health concern. Evidence shows that smoking significantly impairs antibody production and immune cell activity following vaccination. Objectives. This review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature regarding how smoking reduces the effectiveness of active immunization by affecting vaccine-induced immune response. Methods. This study was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines, and the protocol was registered on the PROSPERO platform (ID: CRD42024582638). PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science were consulted as bibliographic and citation databases. Studies published in Italian and English and that aimed to investigate the effects of exposure to active and passive tobacco smoking on vaccine-induced immune response were included. Results. Thirty-four studies were selected. Overall, a decrease in antibody levels and avidity and in immune cell production were observed in individuals exposed to smoke. The meta-analysis showed a weighted mean difference between smokers and non-smokers equal to 0.65 (95% CI: 0.10–1.19, p = 0.02) for vaccinations against COVID-19, influenza, pneumococcus, HBV, HPV, tetanus, pertussis, polio, haemophilus influenzae type b, measles–mumps–rubella, and recurrent urinary tract infections. Conclusions. Smoking cessation campaigns should be considered in order to increase the effectiveness of vaccination programs. Furthermore, the opportunity to adopt different vaccine dosing schemes for smokers and non-smokers, especially in acute epidemics, should be considered.

1. Introduction

Smoking is one of the most common and harmful habits worldwide and it represents a huge and widespread public health problem [1]. The global tobacco epidemic has severe health and economic impacts, which makes tobacco control an essential public health issue [2]. Despite the plethora of initiatives implemented to combat this habit, in 2020, the use of tobacco products remained prevalent among 22.3% of the global population (36.7% of men and 7.8% of women) [1]. In recent decades, new alternative types of tobacco smoke have also appeared on the market and become available for sale, such as electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDSs). The most common of these products are electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), which have also begun to receive much attention from the scientific community [3]. Other new devices include HTPs, which allow users to inhale nicotine by heating reconstituted tobacco to 350 degrees Celsius, in contrast to the way in which it is inhaled via traditional cigarettes [4]. Together with hypertension, smoking constitutes the main risk worldwide for premature death and disability among all age groups [5]. Tobacco smoking, in fact, kills approximately 8 million people a year worldwide. Of these deaths, almost 7 million are directly related to tobacco consumption and over 1.3 million are caused by second-hand smoke exposure for non-smokers [1]. As a result of exposure to tobacco toxins, smoking has several adverse health effects, including an increased risk of developing lung cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, respiratory tract infections from bacteria and viruses, and other conditions [6]. Furthermore, smoking affects the immune system [7]. It has been demonstrated that cigarette smoking is associated with an elevated risk of developing a number of immunological disorders. These include systemic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, and autoimmune diseases, such as allergies and transplant rejection. Additionally, studies have demonstrated that smoking impairs the immune system’s ability to respond to external antigens, which compromises its capacity to combat infections [8,9,10]. Investigations into the effects of smoking on the immune system have also looked into the humoral response following immunization and the persistence of protection elicited by a number of vaccines. According to certain research, active smokers have a higher chance of having low immunoglobulin G (IgG) avidity or lower levels of vaccine-induced antibodies [7]. This hypothesis, if confirmed, could constitute a future public health problem, as the reduction of vaccine effectiveness would reduce vaccination coverage, with a negative impact on both health and public spending. It is widely recognized that smoking affects the humoral response after immunization. However, evidence is insufficient to draw firm conclusions or consensus on this issue. This is probably because the study population varies depending on factors such as age, comorbidities, and smoking history, or because different types of vaccines have different effects [7]. Given the high prevalence of smoking worldwide and the primary importance of vaccines as a priority public health issue, this review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the literature on the impact of tobacco smoking on vaccines’ effectiveness. In particular, the research question of the review is as follows: considering all types of vaccines, how does smoking affect the vaccine-induced immune response?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

This review was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. This tool reports guidelines that are designed to help researchers to perform and report the reason for the systematic review, the methods used, and the main findings [11]. The protocol was recorded on PROSPERO (ID: CRD42024582638). The bibliographic and citation databases used for the search were Scopus, PubMed (Medline) and Web of Science (Science and Social Science Citation Index). The following keywords, with Boolean operators such as AND–OR, were utilized: (“cigarette smoke” OR “smoke” OR “secondhand smoke” OR “thirdhand smoke” OR “smoker *” OR “active smoking” OR “e-cigarette *”) AND (“vaccine *” OR “vaccination *” OR “vaccine efficacy” OR “vaccination efficacy” OR “immunization” OR “antibody response to vaccination” OR “humoral immunity” OR “vaccine antibody levels”). The search was conducted from 9 August 2024 to 30 August 2024. The research included all of the articles published from inception of each database to 30 August 2024.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All studies that were published in Italian and English language and which aimed to investigate the effects of exposure to active and/or passive tobacco smoking, including the use of new tobacco products such as e-cigarettes and heat-not-burn products, on vaccine-induced immune response were included. Any observational, semi-experimental and experimental studies on humans were considered, whereas studies not reporting original data, such as reviews, systematic reviews, case studies, proceedings, qualitative investigations, book chapters, editorials, or commentary studies, were excluded. The evaluation of further critical and systematic review and/or meta-analysis references was undertaken with the aim of finding additional published literature. Any article that did not meet the requirements for inclusion was excluded. In order to structure the research question, the PICOS model was used, as follows:

- Population: all people (individuals of all gender, age, ethnicity and health conditions) vaccinated against any vaccine-preventable disease.

- Intervention: active and/or passive tobacco smoking.

- Control: age-, gender- and condition-matched non-smoking control group (if present).

- Outcomes: effects of active and/or passive tobacco smoking on vaccine-induced immune response.

- Study: observational studies, semi-experimental and experimental studies on humans. All studies that did not satisfy the inclusion criteria were excluded.

The references of all the chosen papers were exported on Zotero citation management software (RRID:SCR_013784), for the purpose of removing any duplicates and to assess the relevance of each article. Firstly, by reviewing the titles and abstracts of the potentially eligible studies, three researchers (A.P., K.V. and F.L.) independently verified the information. The process of examining and evaluating was aided by four topic experts: C.P., F.G., F.V., and C.P.P. The full text of each included article was then assessed separately by the two investigators (A.P., K.V.). Any disagreements over the chosen articles were discussed and resolved by the group.

2.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

Thirty-four studies, of which four were randomized clinical trials, one was a non-randomized clinical trial, eight were cross-sectional studies and twenty-one were cohort studies, were obtained at the end of the evaluation and selection process. Two investigators (A.P., K.V.) independently estimated the quality of each study through the NOS tools and the checklist to evaluate a report of a non-pharmacological trial (CLEAR NPT). The NOS scale, which was adjusted for the cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies assessed, was used to assess the quality of observational research. The overall rating was calculated using this scale. The average of the writers’ ratings was used to establish the final rating of each article. The scale has several numbers of questions and scores for different types of research, as follows: 8 questions with a maximum score of 9 for case-control and cohort studies, and 6 questions with a maximum score of 7 for cross-sectional studies. A score from 7 to 9 indicates good quality, from 5 to 6 indicates average quality, and from 0 to 4 indicates poor quality. The CLEAR NPT checklist was applied specifically to elaborate the quality of non-pharmacological clinical trials. It is composed of 10 questions with 3 answer options each (yes, no, not reported). These questions allowed us to determine the risk of bias for each study (high, medium and low bias risk). Each affirmative answer corresponds to 1 point: 10 to 8 points means a low bias risk, 7 to 5 indicates a medium bias risk and lower than 5 indicates a high bias risk. The group of four researchers debated and solved any dissension about the score obtained for each study. The data extraction table includes the quality assessment. Additionally, first author, publication year, nation, sponsorship, study design, sample size, population characteristics, tobacco smoking type, vaccine type, and the main results of each article are listed in this table.

2.4. Data Synthesis

We also performed a comprehensive meta-analysis in order to assess the impact of smoking on vaccine efficacy [12]. Odds ratios were calculated as effect size (ES) estimates. The reported vaccine efficacy (VE) was calculated using the equation [ratio = (1 − VE%)/100]. The same method was used to obtain 95% confidence intervals (CI). The following risk classification was used to interpret the VE: very low vaccine efficacy (VE 0–0.3), low vaccine efficacy (VE 0.4–0.5), slight vaccine efficacy (VE 0.6–0.8), no effect (VE 0.9–1.1), high vaccine efficacy (VE 1.2–1.6), high vaccine efficacy (VE > 1.7). Cochran’s Q (Hedges Q statistic) was employed for the purpose of assessing the diversity of the named studies and for the testing of the classical measure of diversity. The following thresholds were employed in the interpretation of I2: a value of less than 25% indicates low heterogeneity, a value of less than 50% indicates moderate heterogeneity, and a value of greater than 75% indicates high heterogeneity. In order to estimate potential publication bias due to the high volume of samples included, the Egger’s test and channel plot were performed. Subgroup analyses were conducted for outcomes reported in studies comprising two or more groups within each subgroup. To identify the anticipated sources of heterogeneity, meta-regression and subgroup analysis were employed [13]. A series of predefined subgroup analyses were conducted, taking into account the type of vaccine, sample size, gender, age range, publication year, and methodological quality of the study and design of study. A meta-regression analysis was conducted using the Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software with the unrestricted maximum likelihood method [13].

3. Results

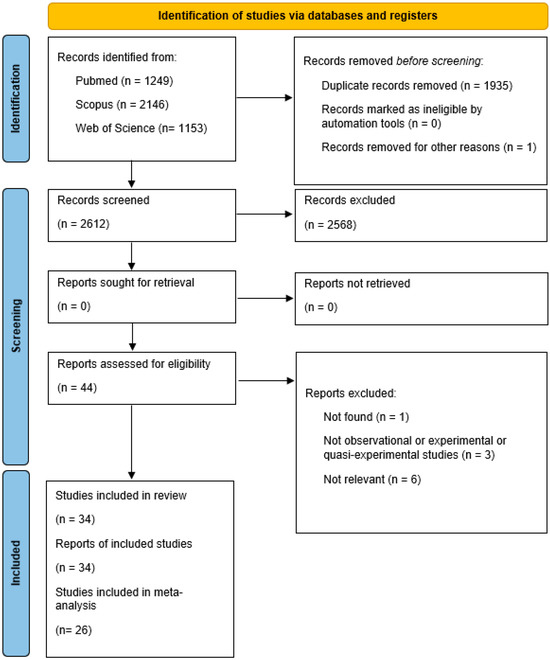

Using the search terms, 4548 records were found across the databases. After the removal of 1935 duplicates and 1 article that had been withdrawn from publication, 2612 items were screened by title and abstract. Of the 44 records remaining, 10 were eliminated because they did not match the qualifying requirements. The final systematic review comprised 34 publications, with 26 papers included in the meta-analysis. Figure 1 outlines the selection procedure.

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for studies included in the analysis.

Table 1 reports the bibliographic information, study design and country, potential corporate sponsorship, sample characteristics, type of smoking, type of vaccination, main results and quality of the selected studies.

Table 1.

Main characteristics and results of the included studies.

Five of the included studies were clinical trials—four [14,16,17,23] were randomized and one [15] was not randomized. According to the CLEAR NPT checklist for bias risk testing, three clinical trials have a medium bias risk and two a low bias risk. Twenty-one of the selected articles [19,20,21,22,24,26,27,28,29,31,32,33,34,37,38,39,42,43,44,45,47] reported cohort studies and the remaining eight reported cross-sectional studies [18,25,30,35,36,40,41,46]. According to the NOS scale for the quality of cohort and cross-sectional studies, twenty-four of them were good quality, four were shown to be of fair quality and only one was shown to be of poor quality. The studies took place in different continents (Europe, Australia, Asia, USA) and were carried out over the period from 1976 to 2024. Vaccinations against COVID-19, influenza, pneumococcus, HBV, HPV, tetanus, pertussis, polio, haemophilus influenzae type b, measles–mumps–rubella, and recurrent urinary tract infections were analysed.

The study populations were divided into non-smokers and smokers. In this last category, two subgroups were identified according to smoking habits: subjects exposed to passive smoking and subjects exposed to active smoking. Among active smokers, a further differentiation between current and former smokers was made. In addition, attention was drawn to the various means for tobacco smoking, such as cigarettes, pipes, cigars, new electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDSs) such as electronic cigarettes, and heated tobacco products (HTPs). Regarding the various types of smoking, thirty-three articles focused on active tobacco smoking [14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47], but only one of these covered cigar and pipe smoking in addition to cigarette smoking [17]. This article showed a significant negative correlation between smoking and influenza vaccine-induced antibody titre.

No studies related to the use of electronic cigarettes were found, whereas two studies were identified regarding both classic tobacco smoking and heated tobacco products [36,40]. Both of these studies evaluated the effect of smoking on the change in antibody titre induced by the BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. The first shows a significant negative correlation between the Fagerstrom test and IgG levels in users of both types of tobacco, but a non-significant negative correlation was found between cotinine and antibody levels. In contrast, the second study highlights that exclusive cigarette smokers have a significant reduction in antibody titre, which is non-significant in heated tobacco users.

Significant reduction in antibody titre (pertussis, polio, haemophilus influenzae type b, measles–mumps–rubella vaccines) has also been shown with regard to the exposure to second-hand smoke, but only one study about this issue was included in the systematic review [18].

Reduced antibody titre has been studied as an outcome in several other studies concerning active smoking [15,19,23,26,27,30,31,32,33,38,39,41,42,44,45,46]. In almost all cases, the negative correlation was found to be statistically significant in relation to two vaccinations: different types of COVID-19 vaccine [26,27,30,31,32,33,38,39,42,44,45] and the pneumococcal vaccine [19]. The latter article also highlights the significant association between the number of cigarettes smoked per day and the number of packs smoked per year with reduced antibody levels. The negative correlation between active tobacco smoking and reduced antibody titre was found to be non-statistically significant for anti-HBV [15], tetanus [23], and anti-COVID-19 vaccination [41,46]. Some peculiarities emerged from the analysed studies. The study of Nomura et al. [28] reported sex differences within the smoking category: the median percentage change in antibody titres was significantly lower in female smokers, indicating a more rapid antibody decline in women than in men. On the other hand, the second article of the same group [27] stated that the difference between sexes in age-adjusted median antibody titres in those who had always smoked vs. those who had never smoked had no significant value. Nevertheless, the same study verifies a significant reduction in vaccine-induced antibody titre not only in comparisons between current smokers and those who have never smoked and between former smokers and those who have never smoked, but also between current and ex-smokers. This striking difference between the latter two categories could be of fundamental importance, as it would imply a potential increase in vaccine efficacy in those who decide to quit smoking. The second most investigated outcome was the negative correlation between active tobacco smoking and vaccine failure, which was found to be statistically significant for HBV [16,22,24], tetanus [23], and COVID-19 BNT162b2 mRNA [29] vaccinations. Nevertheless, some studies have shown a negative but not statistically significant correlation, particularly for HBV vaccination [15] and anti-COVID-19 [25]. A limited number of studies have evaluated the correlation between active tobacco smoking and vaccination efficacy as an outcome. All of these showed a negative association, which was statistically significant for the influenza [17], HBV [47] and HPV [35] vaccines. A negative but non-significant correlation emerged for this latter vaccination in the study by Namujju et al. [21], and for MV140 vaccine in that of Ramirez Sevilla et al. [37].

Finally, the negative correlation between active tobacco smoking and antibody longevity for COVID-19 BNT162b2 mRNA [31,34] and influenza [14] vaccines found was found to be statistically significant. Regarding the latter vaccination, only the study by Nath et al. [20] found no association between active tobacco smoking and response to vaccine.

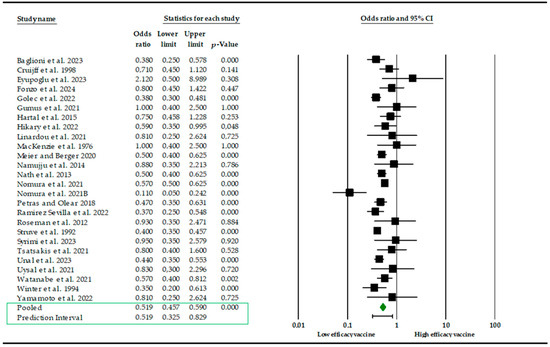

The meta-analysis was based on a synthesis of the findings from 25 studies. Eight studies were excluded from the analysis due to the unavailability of the requisite data. The effect size index is represented by the odds ratio as vaccine efficacy (VE). As illustrated in Figure 2, the meta-analysis results indicate that smokers are at an elevated risk of producing a diminished level of immune cells (VE, 0.519; 95% CI, 0.457–0.590, Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the efficacy of vaccines (VE) after smoking exposure [14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,32,33,34,35,37,40,41,42,43,45,46,47].

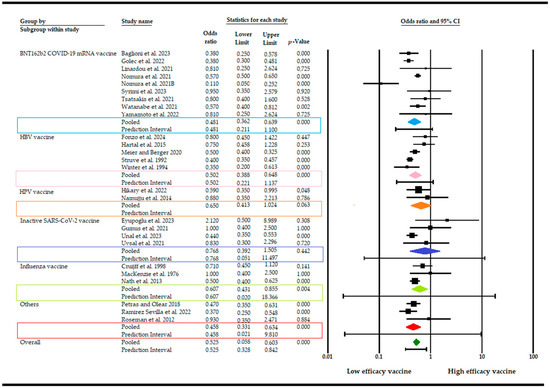

The effects of the individual studies exhibited a moderate level of heterogeneity (Q = 65.16, d.f. = 25, p-value < 0.001, I2 = 62%). Studies incorporated for the analysis demonstrated slight heterogeneity (I2 = 62%; p-value < 0.001), which was adequately addressed with a weighted inverse variance random effects model. For further analysis of this heterogeneity, we used a funnel plot as a subjective assessment and conducted subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and univariate meta-regression for objective assessment of the aetiologies of heterogeneity. Subgroup analysis (Figure 3) based on the type of vaccine revealed that the highest elevated risk of producing a diminished level of immune cells is linked to the BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA vaccine and HBV (VE, 0.481; 95% CI, 0.362–0.639; I2 = 73.2%; p < 0.001; VE, 0.502; 95% CI, 0.388–0.648; I2 = 63%; p < 0.001), while the lowest was in inactive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (VE, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.392–1.505; I2 = 63%; p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the efficacy of vaccines (VE) after smoking exposure with subgroup analysis [14,15,16,17,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,30,32,33,34,35,37,40,41,42,43,45,46,47].

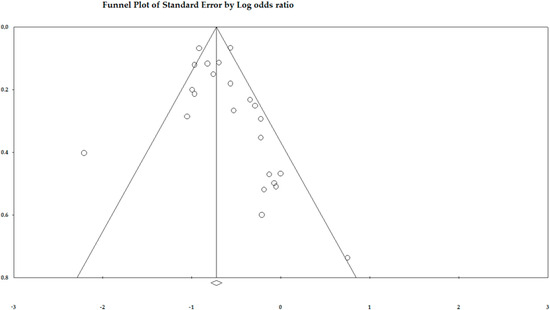

Additionally, subgroup analysis was also based on the design and quality of study. The risk of producing a diminished level of immune cells is similar with reference to the design of the study (VE, 0.514; 95% CI, 0.217–1.739; I2 = 64%; p < 0.001) and the same is true for quality (VE, 0.509; 95% CI: 0.4069–0.552, I2 = 61%; p < 0.001). To investigate the factors influencing the efficacy of the vaccine in smokers, a meta-regression analysis was performed, considering sample size, gender, age, study designs and publication year, as well as the type of vaccine. The results demonstrate that the effect was not dependent on the proportion of female participants in the sample (p = 0.09) or the mean age of participants (p = 0.140). Moreover, the study design (p = 0.690) and quality of study (p = 0.450) seem not to have influenced the results. Conversely, the efficacy of the vaccine exhibited a modest decline contingent on the specific formulation, indicating that smoke exposure might exert a more pronounced influence on vaccine efficacy relative to other variables (Q = 2.62, d.f. = 3, p < 0.05). A comprehensive examination of the impact of smoke exposure on vaccine efficacy was conducted, utilizing data from 26 disparate sources. A sensitivity analysis of the level of immune cells was conducted using a random effects model. The exclusion of studies with a smaller sample size resulted in a slight difference in the pooled VE, which did not significantly affect the stability of the summary result. The potential for publication bias was evaluated both subjectively and objectively. Subjectively, the funnel plot (Figure A1) was examined, and objectively, Egger’s regression test was conducted, yielding a p-value of 0.02 and thus indicating that we cannot exclude the absence of small missing studies and, consequently, the absence of publication bias.

4. Discussion

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to explore the impact of smoke on vaccine efficacy. The final systematic review comprised 34 publications, with 26 papers included in the meta-analysis. The selected articles suggest that the exposure to tobacco may negatively affect the production of vaccine-induced antibodies after immunization, independently of smoking type.

Evidence shows that smoking affects the immune system and cigarette smoking is linked to an increased risk of developing several immunological diseases, including allergies, transplant rejection and rheumatoid arthritis [7]. It also impairs the immune system’s ability to respond to external antigens, increasing the risk of infection [48]. Smoking harms the immune system in multiple ways, affecting both innate and adaptive immunity [7]. Smoking lowers immune cell counts, although the effect of tobacco chemicals varies depending on individual smoking habits and the cells studied. In particular, analyses of Ig have revealed a decreased production of IgA, IgG, and IgM associated with smoking, affecting the ability to generate memory cells [31,49,50,51,52]. Furthermore, effects of smoking have been observed on inflammatory cytokine and chemokine production, chronic inflammation, and reduced T cell proliferation [51,52,53]. It has been demonstrated that smoking, in addition to latent cytomegalovirus infection and body mass index, constitutes a significant external contributor to the development of the disease, almost as important as age, sex and genetics [54]. It has been established that smoking affects both innate and adaptive immune responses [55,56]. The effect of smoking on innate responses is observed to diminish rapidly following cessation of the habit, while the effect on adaptive responses is observed to persist for a longer period of time. Some findings have revealed that, subsequent to smoking cessation, cytokine secretion in the innate immune response reverts to the levels observed in non-smokers but that the effects on the adaptive response persist for years, probably due the epigenetic memory [57,58,59]. In particular, Saint-André et al. have demonstrated that smoking exerts an influence on cytokine responses, the methylation of signal trans-activators and on the regulators of metabolism [60]. Moreover, it seems that several types of smoking, including e-cigarette aerosols, can variously affect the immune system [61,62]. Indeed, although e-cigarettes were first introduced in 2007 as a mean of assisting smokers to quit, specific modifications to the inflammatory and immune milieu associated with long-term use have been identified, probably due to the formation of new decomposition compounds of questionable toxicity [63].

This systematic review has highlighted that smoking detrimentally affects the vaccine-induced immune response. In fact, nearly all of the selected articles showed a negative relationship between tobacco exposure and response to vaccines, whether expressed as antibody titres or vaccine effectiveness, vaccine failure or antibody longevity.

Our meta-analysis results suggest that the efficacy of the vaccine may be reduced by exposure to tobacco, depending on the specific typology of vaccines. The observed heterogeneity among the studies (I2 = 62%; p-value < 0.001) necessitated additional analyses to elucidate the underlying causes. Although a weighted inverse variance random effects model was inadequate for addressing the observed heterogeneity, a combination of subjective assessments through funnel plots and objective analyses, including subgroup analysis, sensitivity analysis, and univariate meta-regression, was employed to gain further insight. The aforementioned approaches were employed to elucidate the potential sources of heterogeneity, thereby affording a more nuanced comprehension of the variability in vaccine efficacy (VE) reported. Subgroup analysis based on the type of vaccine revealed that the COVID-19 mRNA, HBV, MV140, and tetanus vaccines exhibited a greater reduction in efficacy following smoking. Moreover, the efficacy of the vaccine may be influenced by the route of administration and the smoker’s habits. It has been demonstrated that cigarette smoke can lead to a reduction in the responsiveness of the immune system to mucosal vaccines, as evidenced by a decline in antibody production and an increase in the incidence of adverse reactions [64]. Although the results have yet to be corroborated by subsequent studies, it appears that smoking does not impede antibody production in response to the influenza vaccine. Conversely, several studies have indicated that the hepatitis B vaccination may be less effective in smokers than in non-smokers [15,16,24]. Furthermore, the results suggest that there may be a statistically significant impact of smoking on antibody response, contingent on the vaccine formulation. In particular, there appears to be a significant association between smoking and antibody response to mRNA vaccines, whereas the association appears to be relatively weak with inactivated vaccines [65,66]. Nevertheless, the impact of active or previous smoking on the immune response to the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine remains inconclusive, particularly with regard to the underlying mechanisms. Linardou et al. proposed the hypothesis that smoking may exert a suppressive effect on the immune system by directly affecting T cells and dendritic cells, which can impede the vaccination response [26]. A recent study, conducted as part of the VASCO project on healthcare workers, demonstrated that smoking impairs the formation of memory cells, which are essential for maintaining vaccine-induced immunity [31]. Additionally, smoking has been observed to elevate monocyte and macrophage levels, which may potentially influence the clearance of antibodies that typically persist for a duration of 3–4 weeks [67].

This review demonstrates the existence of significant limitations in the research on this topic. Firstly, evidence remains relatively limited, particularly in relation to certain vaccine formulations, such as those based on mRNA. Furthermore, data and findings pertaining to variables such as the duration of smoking, the number of cigarettes smoked per day, passive smoking exposure, and vaccine efficacy are either absent or inconsistent across the various types of vaccines. Moreover, while the majority of retrieved studies employed regression analysis to estimate the independent effect of smoking adjusting for well-established predictors of vaccine response, it is also important to consider that the humoral response to vaccines may be influenced by other factors beyond smoking exposure. These include age, comorbidities, the medication history of the vaccinees, and the number of vaccine doses. Consequently, only preliminary conclusions can be drawn at this stage. In light of these considerations and the inherent limitations in the quality of the data and reporting, our findings should be interpreted with caution and further investigations are required on this issue. In particular, longer controlled studies are needed in order to clarify both the smoking effects on the long-term effectiveness of vaccines and the role of smoking cessation in restoring or improving the vaccine-induced immune response. Nevertheless, the present study represents the inaugural attempt to synthesize epidemiological studies on the impact of smoking on post-vaccination antibody titres in a systematic way. The findings of this research will indubitably inform public health policy and practice. However, the examined studies have demonstrated considerable heterogeneity due to the variability in vaccines and types of exposure investigated. In addition, the effect size may be larger in small studies because we retrieved a biased sample of the smaller studies, and it is also possible that the effect size really is larger in smaller studies—perhaps because the smaller studies used different populations or different protocols than the larger ones. Moreover, it is of the utmost importance to consider the inter-individual variability in immune response when interpreting these data. Further research in this field is necessary to corroborate our findings.

5. Conclusions

Vaccines represent a crucial instrument for the prevention and management of infectious diseases. Evidence suggests that the vaccine-induced immune response is affected by smoking. This review offers a framework for policymakers to address health disparities between smokers and non-smokers. The implementation of health education programs that encourage smoking cessation may enhance the efficacy of immunization campaigns. However, as of today, policies on smoking cessation have limited effectiveness. Thus, in order to enhance the vaccine-induced immune response in smokers, the opportunity to adopt different vaccine dosing schemes for smokers and non-smokers should be considered, especially in the case of acute epidemics. In this perspective, differences in smoking habits across different countries and cultural contexts should be taken in account.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.P., F.V. and F.G.; methodology, K.V., F.L. and A.P.; software, K.V. and A.P.; validation, C.P., F.V. and F.G.; formal analysis, K.V., A.P. and F.L.; data curation, C.P., F.V. and F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, C.P., F.V., K.V., A.P. and F.G.; writing—review and editing, C.P., F.V. and F.G.; resources, G.L.; supervision, C.P, F.V., G.L. and F.G.; project administration, C.P., F.V. and F.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (grant PRIN 2017 n. 20177MKB4H).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analysed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Figure A1.

Funnel plots for meta-analysis regarding the efficacy of vaccines (VE) after smoking exposure.

References

- World Health Organization Tobacco. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Reitsma, M.B.; Kendrick, P.J.; Ababneh, E.; Abbafati, C.; Abbasi-Kangevari, M.; Abdoli, A.; Abedi, A.; Abhilash, E.S.; Abila, D.B.; Aboyans, V.; et al. Spatial, temporal, and demographic patterns in the prevalence of smoking tobacco use and attributable burden of disease in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: A systematic review of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021, 397, 2337–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic 2021: Addressing New and Emerging Products. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240032095 (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Upadhyay, S.; Rahman, M.; Johanson, G.; Palmberg, L.; Ganguly, K. Heated Tobacco Products: Insights into Composition and Toxicity. Toxics 2023, 11, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Available online: https://www.healthdata.org/research-analysis/gbd (accessed on 6 September 2024).

- Taucher, E.; Mykoliuk, I.; Lindenmann, J.; Smolle-Juettner, F.M. Implications of the Immune Landscape in COPD and Lung Cancer: Smoking Versus Other Causes. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 846605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, P.; Gianfredi, V.; Tomaselli, V.; Polosa, R. The effect of smoking on the humoral system Response to COVID-19 vaccines: A systematic review of epidemiological studies. Vaccines 2022, 10, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastratovic, N.; Zdravkovic, N.; Cekerevac, I.; Sekerus, V.; Harrell, C.R.; Mladenovic, V.; Djukic, A.; Volarevic, A.; Brankovic, M.; Gmizic, T.; et al. Effects of Combustible Cigarettes and Heated Tobacco Products on Systemic Inflammatory Response in Patients with Chronic Inflammatory Diseases. Diseases 2024, 12, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Fu, J.; Liu, J.; Wu, X.; Zheng, X.; Wang, S. Association between secondhand smoke exposure and rheumatoid arthritis in US never-smoking adults: A cross-sectional study from NHANES. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 11061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.; Yang, P.; Liu, H.; Wang, Z.; Hu, P.; Ye, P.; Xia, J.; Chen, S. Assessing Causality Between Second-Hand Smoking and Potentially Associated Diseases in Multiple Systems: A Two-Sample Mendelian Randomization Study. Nicotine Tob. Res. 2024, 26, 678–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thompson, S.G.; Deeks, J.J.; Altman, D.G. Measuring Inconsistency in Meta-Analyses. BMJ 2003, 327, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, R.; Friede, T.; Koch, A.; Kuss, O.; Schlattmann, P.; Schwarzer, G.; Skipka, G. Methods for Evidence Synthesis in the Case of Very Few Studies. Res. Synth. Methods 2018, 9, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacKenzie, J.S.; MacKenzie, I.H.; Holt, P.G. The effect of cigarette smoking on susceptibility to epidemic influenza and on serological responses to live attenuated and killed subunit influenza vaccines. J. Hyg. 1976, 77, 409–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Struve, J.; Aronsson, B.; Frenning, B.; Granath, F.; von Sydow, M.; Weiland, O. Intramuscular versus intradermal administration of a recombinant hepatitis B vaccine: A comparison of response rates and analysis of factors influencing the antibody response. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 1992, 24, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, A.P.; Follett, E.A.C.; McIntyre, J.; Stewart, J.; Symington, I.S. Influence of smoking on immunological responses to hepatitis B vaccine. Vaccine 1994, 12, 771–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruijff, M.; Thijs, C.; Govaert, T.; Aretz, K.; Dinant, G.J.; Knottnerus, A. The effect of smoking on influenza, influenza vaccination efficacy and on the antibody response to influenza vaccination. Vaccine 1999, 17, 426–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baynam, G.; Khoo, S.K.; Rowe, J.; Zhang, G.; Laing, I.; Hayden, C.; Kusel, M.; DeKlerk, N.; Sly, P.; Goldblatt, J.; et al. Parental smoking impairs vaccine responses in children with atopic genotypes. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2007, 119, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roseman, C.; Truedsson, L.; Kapetanovic, M.C. The effect of smoking and alcohol consumption on markers of systemic inflammation, immunoglobulin levels and immune response following pneumococcal vaccination in patients with arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2012, 14, R170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, K.D.; Burel, J.G.; Shankar, V.; Pritchard, A.L.; Towers, M.; Looke, D.; Davies, J.M.; Upham, J.W. Clinical factors associated with the humoral immune response to influenza vaccination in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2014, 9, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namujju, P.B.; Pajunen, E.; Simen-Kapeu, A.; Hedman, L.; Merikukka, M.; Surcel, H.M.; Kirnbauer, R.; Apter, D.; Paavonen, J.; Hedman, K.; et al. Impact of smoking on the quantity and quality of antibodies induced by human papillomavirus type 16 and 18 AS04-adjuvanted virus-like-particle vaccine—A pilot study. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartal, M.; Yavnai, N.; Galor, I.; Avramovich, E.; Sela, T.; Kayouf, R.; Tzurel-Ferber, A.; Greenberg, L.J.; Halperin, T.; Levine, H. Seroprevalence of anti-HBs antibodies at young adulthood, before and after a booster vaccine dose, among medical personnel vaccinated in infancy. Vaccine 2015, 33, 4878–4885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petráš, M.; Oleár, V. Predictors of the immune response to booster immunisation against tetanus in Czech healthy adults. Epidemiol. Infect. 2018, 146, 2079–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, M.A.; Berger, C.T. A simple clinical score to identify likely hepatitis B vaccination non-responders—Data from a retrospective single center study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gümüş, H.H.; Ödemiş, İ.; Alışka, H.E.; Karslı, A.; Kara, S.; Özkale, M.; Gül, E. Side effects and antibody response of an inactive severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 vaccine among health care workers. Rev. Assoc. Med. Bras. 2021, 67, 1825–1831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardou, H.; Spanakis, N.; Koliou, G.A.; Christopoulou, A.; Karageorgopoulou, S.; Alevra, N.; Vagionas, A.; Tsoukalas, N.; Sgourou, S.; Fountzilas, E.; et al. Responses to SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Patients with Cancer (ReCOVer Study): A Prospective Cohort Study of the Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group. Cancers 2021, 13, 4621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nomura, Y.; Sawahata, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Kurihara, M.; Koike, R.; Katsube, O.; Hagiwara, K.; Niho, S.; Masuda, N.; Tanaka, T.; et al. Age and Smoking Predict Antibody Titres at 3 Months after the Second Dose of the BNT162b2 COVID-19 Vaccine. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nomura, Y.; Sawahata, M.; Nakamura, Y.; Koike, R.; Katsube, O.; Hagiwara, K.; Niho, S.; Masuda, N.; Tanaka, T.; Sugiyama, K. Attenuation of Antibody Titers from 3 to 6 Months after the Second Dose of the BNT162b2 Vaccine Depends on Sex, with Age and Smoking Risk Factors for Lower Antibody Titers at 6 Months. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitzalis, M.; Idda, M.L.; Lodde, V.; Loizedda, A.; Lobina, M.; Zoledziewska, M.; Virdis, F.; Delogu, G.; Pirinu, F.; Marini, M.G.; et al. Effect of Different Disease-Modifying Therapies on Humoral Response to BNT162b2 Vaccine in Sardinian Multiple Sclerosis Patients. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 781843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsatsakis, A.; Vakonaki, E.; Tzatzarakis, M.; Flamourakis, M.; Nikolouzakis, T.K.; Poulas, K.; Papazoglou, G.; Hatzidaki, E.; Papanikolaou, N.C.; Drakoulis, N.; et al. Immune response (IgG) following full inoculation with BNT162b2 COVID-19 mRNA among healthcare professionals. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2021, 48, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, P.; Ponticelli, D.; Agüero, F.; Caci, G.; Vitale, A.; Borrelli, M.; Schiavone, B.; Antonazzo, I.C.; Mantovani, L.G.; Tomaselli, V.; et al. Does smoking have an impact on the immunological response to COVID-19 vaccines? Evidence from the VASCO study and need for further studies. Public Health 2022, 203, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uysal, E.B.; Gümüş, S.; Bektöre, B.; Bozkurt, H.; Gözalan, A. Evaluation of antibody response after COVID-19 vaccination of healthcare workers. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watanabe, M.; Balena, A.; Tuccinardi, D.; Tozzi, R.; Risi, R.; Masi, D.; Caputi, A.; Rossetti, R.; Spoltore, M.E.; Filippi, V.; et al. Central obesity, smoking habit, and hypertension are associated with lower antibody titres in response to COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Diabetes Metab. Res. Rev. 2022, 38, e3465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golec, M.; Fronczek, M.; Zembala-John, J.; Chrapiec, M.; Konka, A.; Wystyrk, K.; Botor, H.; Brzoza, Z.; Kasperczyk, S.; Bułdak, R.J. Early and Longitudinal Humoral Response to the SARS-CoV-2 mRNA BNT162b2 Vaccine in Healthcare Workers: Significance of BMI, Adipose Tissue and Muscle Mass on Long-Lasting Post-Vaccinal Immunity. Viruses 2022, 14, 868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hikari, T.; Honda, A.; Hashiguchi, M.; Okuma, R.; Kurihara, M.; Fukuda, A.; Okuma, E.; Nakao, Y.; Yokoyama, M. The difference in the effectiveness of human papillomavirus vaccine based on smoking status. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2022, 48, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mori, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Kozai, H.; Hotta, K.; Aoyama, Y.; Shigeno, Y.; Aoike, M.; Kawamura, H.; Tsurudome, M.; Ito, M. Antibody response of smokers to the COVID-19 vaccination: Evaluation based on cigarette dependence. Drug Discov. Ther. 2022, 16, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez Sevilla, C.; Gómez Lanza, E.; Llopis Manzanera, J.; Cetina Herrando, A.; Puyol Pallàs, J.M. A Focus on Long-Term Follow-Up of Immunoprophylaxis to Recurrent Urinary Tract Infections: 10 Years of Experience with MV140 Vaccine in a Cohort of 1003 Patients Support High Efficacy and Safety. Arch. Esp. Urol. 2022, 75, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trontzas, I.P.; Vathiotis, I.; Economidou, C.; Petridou, I.; Gomatou, G.; Grammoustianou, M.; Tsamis, I.; Syrigos, N.; Anagnostakis, M.; Fyta, E.; et al. Assessment of Seroconversion after SARS-CoV-2 Vaccination in Patients with Lung Cancer. Vaccines 2022, 10, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toda, M.; Yoshifuji, A.; Kikuchi, K.; Koinuma, M.; Komatsu, M.; Fujii, K.; Kato, A.; Kikuchi, T.; Nakazawa, A.; Ryuzaki, M. Factors associated with SARS-CoV-2 antibody titers and prognosis of breakthrough infection in hemodialysis patients. Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2022, 26, 571–580, Erratum in Clin. Exp. Nephrol. 2022, 26, 581–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, S.; Tanaka, A.; Ohmagari, N.; Yamaguchi, K.; Ishitsuka, K.; Morisaki, N.; Kojima, M.; Nishikimi, A.; Tokuda, H.; Inoue, M.; et al. Use of heated tobacco products, moderate alcohol drinking, and anti-SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody titers after BNT162b2 vaccination among Japanese healthcare workers. Prev. Med. 2022, 161, 107123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmar, I.; Almahmoud, O.; Yaseen, K.; Jamal, J.; Omar, A.; Naseef, H.; Hasan, S. Assessment of immunoglobin G (spike and nucleocapsid protein) response to COVID-19 vaccination in Palestine. Clin. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2023, 22, 101330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baglioni, I.; Galli, A.; Gatti, C.; Tufoni, S.; Rocchi, R.; Lattanzi, F.; Toia, F.; Santarelli, A.; Marcelli, S. Evaluation of antibody response anti SARS-Cov-2: A retrospective observational study (Marche-Italy). Ig. Sanita Pubbl. 2023, 80, 13–26. [Google Scholar]

- Eyupoglu, G.; Guven, R.; Karabulut, N.; Cakir, A.; Sener, K.; Yavuz, B.G.; Tekyol, D.; Avci, A. Humoral responses to the CoronoVac vaccine in healthcare workers. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2023, 56, e0209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prather, A.A.; Dutcher, E.G.; Robinson, J.; Lin, J.; Blackburn, E.; Hecht, F.M.; Mason, A.E.; Fromer, E.; Merino, B.; Frazier, R.; et al. Predictors of long-term neutralizing antibody titers following COVID-19 vaccination by three vaccine types: The BOOST study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 6505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syrimi, N.; Sourri, F.; Giannakopoulou, M.C.; Karamanis, D.; Pantousas, A.; Georgota, P.; Rokka, E.; Vladeni, Z.; Tsiantoula, E.; Soukara, E.; et al. Humoral and Cellular Response and Associated Variables Nine Months following BNT162b2 Vaccination in Healthcare Workers. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ünal, G.; Sezgin, S.D.; Sancar, M. Evaluation of SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Levels in Pharmacists and Pharmacy Staff Following CoronaVac Vaccination. Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 26, 347–351, Erratum in Turk. J. Pharm. Sci. 2024, 21, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonzo, M.; Palmisano, A.; Trevisan, A.; Bertoncello, C. The Impact of Smoking on Long-Term Protection Following Hepatitis B Vaccination: A 24-Year Cohort Study. Viruses 2024, 16, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saulyte, J.; Regueira, C.; Montes-Martínez, A.; Khudyakov, P.; Takkouche, B. Active or passive exposure to tobacco smoking and allergic rhinitis, allergic dermatitis, and food allergy in adults and children: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2014, 11, e1001611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, K.M.; Çolak, Y.; Ellervik, C.; Hasselbalch, H.C.; Bojesen, S.E.; Nordestgaard, B.G. Smoking and Increased White and Red Blood Cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2019, 39, 965–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, F.; Liang, C.; Liu, H.; Zeng, Y.Q.; Hou, S.; Huang, S.; Lai, X.; Dai, Z. Impacts of cigarette smoking on immune responsiveness: Up and down or upside down? Oncotarget 2017, 8, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sopori, M.L. Effects of cigarette smoke on the immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2002, 2, 372–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.P.; Morrow, K.; Velasco, C.; Wyczechowska, D.D.; Naura, A.S.; Rodriguez, P.C. Effects of cigarette smoke extract on primary activated T cells. Cell Immunol. 2013, 282, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piaggeschi, G.; Rolla, S.; Rossi, N.; Brusa, D.; Naccarati, A.; Couvreur, S.; Spector, T.D.; Roederer, M.; Mangino, M.; Cordero, F.; et al. Immune Trait Shifts in Association with Tobacco Smoking: A Study in Healthy Women. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 637974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Yang, H.; Wu, X.; Luo, X.; Shen, J.; Xiao, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Du, F.; Chen, Y.; et al. Dysregulation of immunity by cigarette smoking promotes inflammation and cancer: A review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 339, 122730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, D.; Yang, D.; Cao, D.; Gong, Z.; He, F.; Hou, Y.; Lin, S. Effect of smoking status on immunotherapy for lung cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Oncol. 2024, 14, 1422160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peer, N.; Nguyen, K.A.; Peprah, E.; Xu, H.; Matsha, T.E.; Chegou, N.N.; Kengne, A.P. Exploring the associations of tobacco smoking and serum cotinine levels with selected inflammatory markers in adults with HIV in South Africa. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 25772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, S.; Rouilly, V.; Patin, E.; Alanio, C.; Dubois, A.; Delval, C.; Marquier, L.G.; Fauchoux, N.; Sayegrih, S.; Vray, M.; et al. Milieu Intérieur Consortium. The Milieu Intérieur study—An integrative approach for study of human immunological variance. Clin. Immunol. 2015, 157, 277–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugade, A.A.; Bogner, P.N.; Thatcher, T.H.; Sime, P.J.; Phipps, R.P.; Thanavala, Y. Cigarette smoke exposure exacerbates lung inflammation and compromises immunity to bacterial infection. J. Immunol. 2014, 192, 5226–5235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, T.C.J.; van der Does, A.M.; Kistemaker, L.E.; Ninaber, D.K.; Taube, C.; Hiemstra, P.S. Cigarette smoke differentially affects IL-13-induced gene expression in human airway epithelial cells. Physiol. Rep. 2017, 5, e13347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saint-André, V.; Charbit, B.; Biton, A.; Rouilly, V.; Possémé, C.; Bertrand, A.; Rotival, M.; Bergstedt, J.; Patin, E.; Albert, M.L.; et al. Smoking changes adaptive immunity with persistent effects. Nature 2024, 626, 827–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marques, P.; Piqueras, L.; Sanz, M.J. An updated overview of e-cigarette impact on human health. Respir. Res. 2021, 22, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, J.J.C.; Rebuli, M.E.; Cass, S.P.; Loeb, M.; Jaspers, I. Smoking and e-cigarette use: Key variables in testing IgA-oriented intranasal vaccines. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 822–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, L.; Crotty Alexander, L.E. A Problem for Generations: Impact of E-Cigarette Type on Immune Homeostasis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 1195–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, F.; Maeyama, J.I.; Kubota, A.; Nishimune, A.; Horiguchi, S.; Takii, T.; Urasaki, Y.; Shimada, I.; Iho, S. Effect of cigarette smoke on mucosal vaccine response with activation of plasmacytoid dendritic cells: The outcomes of in vivo and in vitro experiments. Vaccine 2023, 41, 1447–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Şen, S.; Arslan, G.; Tütüncü, M.; Demir, S.; Dinç, Ö.; Gündüz, T.; Uzunköprü, C.; Gümüş, H.; Tütüncü, M.; Akçin, R.; et al. The Effect of Smoking on Inactivated and mRNA Vaccine Responses Applied to Prevent COVİD-19 in Multiple Sclerosis. Noro Psikiyatr. Ars. 2023, 60, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponticelli, D.; Losa, L.; Campagna, D.; Magliuolo, R.; Vitale, A.; Cacciapuoti, D.; Zampella, A.; Alleanza, L.; Schiavone, B.; Spicuzza, L.; et al. Smoking habits predict adverse effects after mRNA COVID-19 vaccine: Empirical evidence from a pilot study. Public Health 2023, 219, 18–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangani, R.G.; Deepak, V.; Anwar, J.; Patel, Z.; Ghio, A.J. Cigarette Smoking, and Blood Monocyte Count Correlate with Chronic Lung Injuries and Mortality. Int. J. Chronic Obstr. Pulm. Dis. 2023, 18, 431–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).