Abstract

Pregnant women are vulnerable to developing influenza complications. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy is crucial to avoid infection. The COVID-19 pandemic might exacerbate fear and anxiety in pregnant women. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on influenza vaccination and determine the factors associated with influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in Korea. We conducted a cross-sectional study using an online survey in Korea. A survey questionnaire was distributed among pregnant or postpartum women within 1 year after delivery. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the factors associated with influenza vaccination among pregnant women. A total of 351 women were included in this study. Of them, 51.0% and 20.2% were vaccinated against influenza and COVID-19 during pregnancy, respectively. The majority of participants who had a history of influenza vaccination reported that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect (52.3%, n = 171) or increased the importance (38.5%, n = 126) of their acceptance of the influenza vaccine. Factors associated with influenza vaccine acceptance were knowledge of influenza vaccine (OR 1.21; 95% CI 1.09, 1.35), trust in healthcare providers (OR 2.57; 95% CI 1.43, 4.65), and COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy (OR 6.11, 95% CI 2.86, 13.01). Participants were more likely to accept the influenza vaccine when they received a COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy, but the rate of influenza vaccination was not affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. This study showed that the COVID-19 pandemic did not influence influenza vaccine uptake in the majority of pregnant women in Korea. The results emphasize the necessity of appropriate education for pregnant women to enhance awareness of vaccination.

1. Introduction

Influenza can develop into severe illness and the influenza-associated all-cause deaths from 2009 to 2016 were found to be 10.59 per 100,000 people annually in Korea [1]. Pregnant women are at high risk for developing complications from influenza, including hospitalization, intensive care unit admission, and death [2]. Infants of pregnant women with influenza infection are more likely to be born preterm, which is associated with neonatal morbidity and mortality [3,4]. Thus, pregnant women should receive the influenza vaccination as a critical strategy to prevent infection; their uptake of the influenza vaccine should also be increased [5]. Additionally, receiving the influenza vaccine during pregnancy effectively prevents influenza infection in infants up to 6 months of age who are ineligible for influenza vaccination [6,7]. Therefore, it is recommended that pregnant women receive an influenza vaccination [8,9].

The number of confirmed cases and deaths due to the COVID-19 pandemic is still increasing [10]. In Korea, 35,086 reported COVID-19 cases and 112 reported hospitalizations on 26 January 2023 [11]. As of June 2022, 211,551 pregnant women had contracted COVID-19 in the United States, contributing to a total of 33,123 hospitalizations and 295 deaths [12]. Studies have suggested that pregnant women with COVID-19 are at a higher risk for hospitalization, mechanical ventilation, intensive care, and death compared to non-pregnant women [13,14,15]. This can negatively impact pregnant women, causing fear and anxiety [16]. In addition, the medical burden has increased due to the COVID-19 pandemic, causing delayed access to healthcare services [17], which is clearly associated with adverse outcomes among pregnant women [18]. Although pregnant women are classified as a COVID-19-vulnerable population, original clinical trials evaluating the efficacy and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine excluded pregnant and lactating women [19,20,21].

Emerging data have provided no evidence of increased adverse outcomes—including miscarriage, preterm birth, or neonatal intensive care unit admission—among pregnant women who received the COVID-19 vaccine [22,23,24]. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy reduces the risks of infection and COVID-19-related hospitalization [25,26,27]. Furthermore, completing a two-dose COVID-19 vaccine regimen during pregnancy can help prevent hospitalization in infants up to 6 months of age [28]. Currently, the COVID-19 vaccination is recommended for pregnant women [29,30,31].

Despite recommendations for vaccination among pregnant women, the acceptance of both influenza and COVID-19 vaccines is low [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. Previous studies have investigated the factors influencing influenza or COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women [35,36,42,43,44,45,46,47,48]. A few studies have examined the knowledge and attitudes towards influenza vaccination among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic [49,50]. However, no studies have investigated the acceptance of the influenza vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant women in Korea.

This study aimed to evaluate the acceptance of the influenza vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic and determine the factors associated with the influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in Korea. This study also examined the knowledge of the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, and health beliefs regarding the influenza vaccine among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

This cross-sectional study was conducted using an online survey in Korea between 1 April 2022 and 15 April 2022. A self-administered questionnaire was created online and distributed through the largest online panel operated by Tillion Pro in Korea [51]. Pregnant or postpartum women within one year of delivery were eligible and participation in the survey was voluntary. To obtain a representative sample of the Korean population, participants were recruited via stratification of regional residences. Individuals under 12 weeks of gestation and who were giving birth to their first child were excluded from the analysis. The sample size was calculated with the following assumptions: the acceptance rate of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy was 62.3% [46], with a confidence interval of 95% and an alpha of 0.05. The sample size was 361. The participants’ identifying information was removed from the data analyzed in this study to ensure confidentiality and anonymity. The study was approved by the Chung-Ang University Institutional Review Board (1041078-202203-HR-063).

2.2. Survey Questionnaires

A structured questionnaire developed based on a literature review was distributed to participants covering the following information: background characteristics, characteristics related to vaccine acceptance, knowledge of the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, and health beliefs related to the influenza vaccine. A pilot test among a sample of 50 pregnant women was conducted as non-facial validation to enhance the clarity and validity of the survey questions.

2.2.1. Background Characteristics

Background characteristics were divided into sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics. Sociodemographic characteristics consisted of age, region of residence, religious affiliation, education, current employment status, economic status, and self-rated health status. Pregnancy characteristics included gestational age, parity, history of miscarriage, complications during pregnancy, and respiratory disease status.

2.2.2. Characteristics Related to Vaccine Acceptance

The participants were asked whether they were vaccinated for influenza and/or COVID-19 during pregnancy. The acceptance of influenza vaccine among pregnant women was collected by asking the question, ‘Have you been vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy?’ We used the question ‘Have you ever been vaccinated against influenza?’ to collect the participants’ histories of influenza vaccination. Their reasons for deciding not to receive a vaccination during pregnancy were also collected using a multiple-choice format in the questionnaire. Side effects after vaccination were also surveyed.

2.2.3. Knowledge Regarding Influenza Vaccine

Eleven items were used to examine participants’ knowledge of the influenza vaccine, including the effectiveness and safety of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, the number of influenza vaccinations, and the recommendations for influenza vaccination during pregnancy. Three responses could be chosen: yes, no, or not sure. If the correct answer was chosen, one point was added to the total score. The total score ranged from 0 to 11.

2.2.4. Trust in Healthcare Providers

Trust in healthcare providers of pregnant women was collected by providing the following two items: (1) If healthcare providers recommend the influenza vaccination, I would get vaccinated; (2) I can trust healthcare providers to give appropriate and effective treatment that is best for me. Answers were scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = do not agree at all to 4 = strongly agree.

2.2.5. Health Beliefs Related to Influenza and Vaccination

Four categories were included: (1) perceived susceptibility to influenza infection; (2) perceived severity of influenza infection; (3) perceived benefits of influenza vaccination; and (4) perceived barriers to influenza vaccination. The participants were asked to rate each item on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = do not agree at all to 4 = strongly agree.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Data were statistically analyzed with SPSS version 27.0. Descriptive statistics were presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means ± standard deviations for continuous variables. Cronbach’s α coefficients were calculated to assess the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire for knowledge, trust in healthcare providers, and health beliefs. Chi-square or t-tests were performed to examine the significance of the differences between the background characteristics of the participants and their influenza vaccine acceptance. A t-test was conducted to compare study variables, including knowledge, trust in healthcare providers, and health beliefs related to the acceptance of the influenza vaccine. Pearson’s correlation coefficients and Point-biserial correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate significant correlations between study variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify the factors associated with the acceptance of the influenza vaccine among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Variables without multicollinearity in univariate logistic regression analyses were entered in multivariate logistic regression analyses. Background characteristics were included in Model 1, and study variables were entered in Model 2. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated and unstandardized regression coefficients (B) were presented in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Two-tailed p < 0.05 was used to define statistical significance.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Study Population

A total of 351 women who were either pregnant (n = 201, 57.3%) or postpartum (n = 150, 42.7%) were included in this study (Table 1). One hundred percent of the study participants (n = 351) responded to all of the questions. Of these women, 50.4% were less than 35 years old, and 49.3% lived in a metropolitan area. The mean gestation age among the participating pregnant women was 23.88 weeks. The majority (80.4%) of women had experienced at least one delivery, and 27.1% had a history of miscarriage. Of the total participants, 51.0% were vaccinated against influenza during pregnancy. Most women had a history of influenza vaccination (n = 327, 93.2%). The COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate during pregnancy was only 20.2% among participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics of the study population.

3.2. Effect of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Influenza Vaccination

In this study, 52.3% (n = 171/327) of the participants who had a history of influenza vaccination reported that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect their acceptance of the influenza vaccine. In contrast, 38.5% (n = 126/327) of them indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic had increased the importance of their acceptance of the influenza vaccine. Only 9.2% (n = 30/327) of them did not believe that influenza vaccination would be necessary.

The majority of women who had never been vaccinated for influenza (91.7%, n = 22/24) reported that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect their acceptance of the influenza vaccine.

3.3. Acceptance of the Influenza Vaccine by Sociodemographic and Pregnancy Characteristics

The mean age of the participants who were vaccinated against influenza was significantly higher than the mean age of the unvaccinated participants (p = 0.007). Furthermore, 36.9% of women vaccinated against influenza had experienced two or more births. Pregnant women with a history of miscarriage, history of education regarding vaccination, willingness to receive the influenza vaccine during pregnancy, history of influenza vaccination, and vaccination against COVID-19 during pregnancy were more likely to accept the influenza vaccination (p < 0.05, Table 2). Cronbach’s α coefficients were in the range of 0.706–0.91.

Table 2.

Acceptance of the influenza vaccine among pregnant women by sociodemographic and pregnancy characteristics.

3.4. Acceptance of the Influenza Vaccine by Knowledge, Trust in Healthcare Providers, and Health Beliefs

Pregnant women who were vaccinated against influenza scored significantly higher than unvaccinated pregnant women on knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, perceived susceptibility to influenza infection, perceived severity of influenza infection, and perceived benefits of influenza vaccination (p < 0.05, Table 3).

Table 3.

Acceptance of the influenza vaccine by knowledge, trust in healthcare providers, and health beliefs.

3.5. Correlation between Knowledge, Trust in Healthcare Providers, Health Beliefs and Acceptance of the Influenza Vaccine

Significant correlations were observed between study variables (Table 4). Influenza vaccination was significantly related to increased knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and perceived benefits (p < 0.01). Knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine and perceived susceptibility was positively related to trust in healthcare providers. Perceived severity was positively related not only to trust in healthcare providers but also to perceived susceptibility. Perceived benefits were positively related to knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, perceived susceptibility, and perceived severity. Perceived barriers were negatively related to knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine, while perceived barriers had a significantly positive correlation with perceived susceptibility and perceived severity.

Table 4.

Correlation between knowledge, trust in healthcare providers, health beliefs, and acceptance of the influenza vaccine.

3.6. Factors Associated with Acceptance of the Influenza Vaccine during Pregnancy

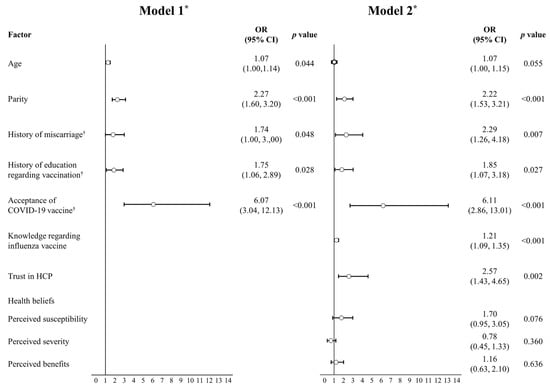

Age, parity, history of miscarriage (1 = yes; 0 = no), history of education regarding vaccination (1 = yes; 0 = no), and acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy (1 = yes; 0 = no) were included in Model 1. Knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and perceived benefits were entered in Model 2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Factors associated with the acceptance of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. n = 351. * Model 1: Hosmer & Lemeshow χ2(5) = 10.77, p > 0.05, Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.276; Model 2: Hosmer & Lemeshow χ2(10) = 8.26, p > 0.05, Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.406. † yes = 1; no = 0. OR: odds ratio; HCP: healthcare providers.

Regression Model 1 fitted the data well (χ2(5) = 10.77; p > 0.05), explaining 27.6% of the variance in the acceptance of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy (Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.276). In Model 1, age (OR 1.07; 95% CI 1.00, 1.14), parity (OR 2.27; 95% CI 1.60, 3.20), history of miscarriage (OR 1.74; 95% CI 1.00, 3.00), history of education regarding the influenza vaccine (OR 1.75; 95% CI 1.06, 2.89), and acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy (OR 6.07; 95% CI 3.04, 12.13) significantly increased the chance for acceptance of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy.

Regression Model 2 also fitted the data well (χ2(10) = 8.26; p > 0.05), explaining 40.6% of the variance in the acceptance of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy (Nagelkerke’s R2 = 0.406). In Model 2, parity (OR 2.22; 95% CI 1.53, 3.21), history of miscarriage (OR 2.29; 95% CI 1.26, 4.18), history of education regarding the influenza vaccine (OR 1.85; 95% CI 1.07, 3.18), acceptance of the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy (OR 6.11; 95% CI 2.86, 13.01), knowledge regarding the influenza vaccine (OR 1.21; 95% CI 1.09, 1.35), and trust in healthcare providers (OR 2.57; 95% CI 1.43, 4.65) significantly increased the chance for acceptance of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy. However, health beliefs including perceived susceptibility, perceived severity, and perceived benefits were not significantly associated with influenza vaccine acceptance.

4. Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first to assess the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on influenza vaccine uptake among pregnant women in Korea. This study also investigated the factors associated with the acceptance of the influenza vaccine, including knowledge of the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, and COVID-19 vaccine uptake.

The acceptance rate of the influenza vaccine was 51% among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Before this pandemic in 2018–2019, the influenza vaccination rates in Korea were 59.3–62.3%, which were similar to the results in this study [46,52]. This result could be attributed to the report of the majority of participants who indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect their acceptance of the influenza vaccine in this study. Conversely, in a recent qualitative interview study that explored the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women’s attitudes toward maternal vaccines in the United Kingdom, participants felt that the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the importance of maternal vaccination, including the influenza vaccine [53]. Another study showed an increase in the acceptance rate of the influenza vaccine during the COVID-19 pandemic among pregnant women [54]. Therefore, it is possible that pregnant women in Korea lacked sufficient education regarding influenza vaccination during the pandemic.

In this study, only 20.2% of women were vaccinated against COVID-19 during pregnancy in Korea. These findings were similar to previous results of studies on pregnant women in other countries [35,36,55,56]. However, a recent study conducted in 16 countries showed that the acceptance rate of the COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant women was 52% (range: 28.8–84.4%) [57]. Another study in China reported a higher rate of COVID-19 vaccination among pregnant women (77.4%) [58]. Therefore, the acceptance rate of the COVID-19 vaccine substantially varied globally.

The COVID-19 vaccination rate was low among pregnant women in Korea likely because pregnant women have concerns about the effectiveness and safety of the COVID-19 vaccine [35,36,47,55,56]. In the present study, more than 60% (n = 172) of the participants who did not receive the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy had concerns regarding the lack of data about vaccine efficacy or its potential side effects, and 27.5% (n = 77) feared that it would harm the fetus.

Our study showed that the vaccinated population was slightly older than the unvaccinated population (34.87 and 33.76 years old, respectively; p = 0.007). The acceptance rate of the influenza vaccine among pregnant women younger than 30 years was 41.3%; whereas, for women older than 40 years, it was 64.3%. In France, a previous study showed that older pregnant women are more likely to be vaccinated against influenza [34]. Our study also found that the participants with high parity or a history of miscarriage were more likely to accept the influenza vaccine. Conversely, influenza vaccination is not influenced by parity and history of miscarriage in several studies [34,46,59]. In the present study, more than two-thirds of women who had a history of education regarding vaccination were vaccinated against influenza. This finding was consistent with the result of a previous study conducted in Korea [46]. Therefore, a recommendation that emerges from this study is that accurate information about vaccination through education should be provided to promote vaccine uptake. Additionally, pregnant women vaccinated against COVID-19 were more likely to accept the influenza vaccination. Similar results were reported in a previous study in Poland [50]. These findings suggested a possible association between receiving influenza and COVID-19 vaccinations among pregnant women.

This study also found that pregnant women vaccinated against influenza had a higher knowledge score on the influenza vaccine than unvaccinated women. Similar results were observed in previous studies. One study showed that pregnant women with a higher knowledge score regarding the influenza vaccine and influenza infection were more likely to accept the influenza vaccination [59]. Another study reported that improving pregnant women’s knowledge about vaccination has helped to increase the acceptance rate of the influenza vaccine [60]. These findings are attributed to the positive association of knowledge about influenza vaccination with acceptance rate [61,62,63]. Healthcare providers play a key role in helping women make an informed choice about vaccines when they are deciding whether to accept the influenza vaccine during pregnancy [64]. In the present study, trust in healthcare providers was significantly higher in pregnant women vaccinated against influenza than in unvaccinated pregnant women. Pregnant women were more likely to get vaccinated when they had a higher perceived susceptibility and severity of infection regarding influenza and know of more benefits from the influenza vaccination. These results are in line with previous studies [45,49,59]. Therefore, pregnant women should receive information about susceptibility to influenza infection and the benefits of influenza vaccination. Moreover, they should recognize the severity of influenza infection.

This study confirmed that the acceptance of the influenza vaccine during pregnancy is associated with various factors, including knowledge of the influenza vaccine and trust in healthcare providers. Pregnant women who received education regarding the influenza vaccine and had a high level of knowledge about the influenza vaccine were more likely to get vaccinated against influenza. These findings were similar to previous studies conducted among pregnant women [59,65,66]. In the present study, trust in healthcare providers was also significantly correlated with the acceptance of the influenza vaccine among pregnant women. A previous qualitative evidence synthesis showed that pregnant women’s trust in healthcare providers can promote making the decision to get vaccinated against influenza [67]. Therefore, acceptance of the influenza vaccine could be improved by increasing the opportunity for healthcare providers who established a good relationship of trust with pregnant women to provide accurate information regarding the influenza vaccine. Furthermore, evidence-based and professional training or education is a necessity for healthcare providers to promote the discussion of influenza vaccination and address the concerns of pregnant women [67].

Participants were six times more likely to accept the influenza vaccine when they received a COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy. This study suggested that influenza vaccination was strongly associated with COVID-19 vaccination. On the other hand, a recent study performed on pregnant women in the United States reported that having had or intending to have an influenza vaccine is highly negatively associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy [68].

This study has several strengths. This study is the first to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on pregnant women’s influenza vaccine uptake in Korea. This study also determined the factors associated with influenza vaccine acceptance among pregnant women in Korea during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, in contrast to previous studies performed in healthcare settings on influenza vaccine acceptance, this is the first survey that uses the online panel stratified by region in Korea. However, this study has several limitations. First, all data were self-reported and could not be validated independently, resulting in a potential reporting bias in the results. Second, although the sample population was stratified by region of residence to minimize potential selection bias, the study population might not be representative of all pregnant women in Korea. The participants were not randomly selected because a panel survey platform was used to perform the online survey. Lastly, the cross-sectional design of this study could not establish causal relationships between factors.

5. Conclusions

This cross-sectional study showed that the influenza vaccine uptake of pregnant women was not influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. Even though pregnant women are vulnerable to both influenza and COVID-19, we found that the acceptance rates of these vaccines were still low in Korea. These results suggest that education for pregnant women was not substantial enough to encourage vaccination, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, knowledge of the influenza vaccine, trust in healthcare providers, and receiving the COVID-19 vaccination were significantly associated with the acceptance of the influenza vaccine among pregnant women. Therefore, additional educational campaigns are needed to enhance awareness of the importance of vaccination and provide information about the vaccine by reliable healthcare providers. This will improve vaccine uptake in pregnant women in Korea.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.K.; methodology, E.K. and B.K.; validation, E.K. and B.K.; formal analysis, E.K. and B.K.; investigation, E.K. and B.K.; data curation, E.K. and B.K.; writing-original draft preparation, B.K.; writing-review and editing, E.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by grant funded by the Korea government (Ministry of Science and ICT, MICT) (NRF2021R1F1A1062044), and by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant Number 2021R1A6A1A03044296), which had no further role in study design, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Chung-Ang University (1041078-202203-HR-063).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in the study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hong, K.; Sohn, S.; Chun, B.C. Estimating influenza-associated mortality in Korea: The 2009–2016 seasons. J. Prev. Med. Public Health 2019, 52, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakala, I.G.; Honda-Okubo, Y.; Fung, J.; Petrovsky, N. Influenza immunization during pregnancy: Benefits for mother and infant. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2016, 12, 3065–3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mosby, L.G.; Rasmussen, S.A.; Jamieson, D.J. 2009 pandemic influenza a (H1N1) in pregnancy: A systematic review of the literature. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2011, 205, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine Committee on Understanding Premature Birth and Assuring Healthy Outcomes. The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health; National Academies Press (USA): Washington, DC, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Tamma, P.D.; Steinhoff, M.C.; Omer, S.B. Influenza infection and vaccination in pregnant women. Expert Rev. Respir. Med. 2010, 4, 321–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaman, K.; Roy, E.; Arifeen, S.E.; Rahman, M.; Raqib, R.; Wilson, E.; Omer, S.B.; Shahid, N.S.; Breiman, R.F.; Steinhoff, M.C. Effectiveness of maternal influenza immunization in mothers and infants. N. Engl. J. Med. 2008, 359, 1555–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eick, A.A.; Uyeki, T.M.; Klimov, A.; Hall, H.; Reid, R.; Santosham, M.; O’Brien, K.L. Maternal influenza vaccination and effect on influenza virus infection in young infants. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2011, 165, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Vaccines against influenza: WHO position paper—May 2022. In Weekly Epidemiological Record; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 19, pp. 185–208. [Google Scholar]

- Jung, E. Guidelines for Adult Immunization, 2nd ed.; Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Chungbuk, Republic of Korea, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cases of COVID-19 in Korea; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2023; Available online: https://ncov.kdca.go.kr/bdBoardList_Real.do?brdId=1&brdGubun=11&ncvContSeq=&contSeq=&board_id=&gubun= (accessed on 29 January 2023).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID Data Tracker; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker (accessed on 3 June 2022).

- Jering, K.S.; Claggett, B.L.; Cunningham, J.W.; Rosenthal, N.; Vardeny, O.; Greene, M.F.; Solomon, S.D. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of hospitalized women giving birth with and without COVID-19. JAMA Intern. Med. 2021, 181, 714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Yeni, C.M.; Utami, N.A.; Masand, R.; Asrani, R.K.; Patel, S.K.; Kumar, A.; Yatoo, M.I.; Tiwari, R.; Natesan, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection during pregnancy and pregnancy-related conditions: Concerns, challenges, management and mitigation strategies-a narrative review. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 863–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allotey, J.; Stallings, E.; Bonet, M.; Yap, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Kew, T.; Debenham, L.; Llavall, A.C.; Dixit, A.; Zhou, D.; et al. Clinical manifestations, risk factors, and maternal and perinatal outcomes of coronavirus disease 2019 in pregnancy: Living systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2020, 370, m3320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymecka, J.; Gerymski, R.; Iszczuk, A.; Bidzan, M. Fear of coronavirus, stress and fear of childbirth in Polish pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 13111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, E.K.; Yun, J.; Hwang, S.H.; Lee, H.; Lee, J.Y. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the healthcare utilization in Korea: Analysis of a nationwide survey. J. Infect. Public Health 2022, 15, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacagnella, R.C.; Cecatti, J.G.; Parpinelli, M.A.; Sousa, M.H.; Haddad, S.M.; Costa, M.L.; Souza, J.P.; Pattinson, R.C. Delays in receiving obstetric care and poor maternal outcomes: Results from a national multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2014, 14, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. People with Certain Medical Conditions; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/people-with-medical-conditions.html (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- Baden, L.R.; El Sahly, H.M.; Essink, B.; Kotloff, K.; Frey, S.; Novak, R.; Diemert, D.; Spector, S.A.; Rouphael, N.; Creech, C.B.; et al. Efficacy and safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 384, 403–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polack, F.P.; Thomas, S.J.; Kitchin, N.; Absalon, J.; Gurtman, A.; Lockhart, S.; Perez, J.L.; Pérez Marc, G.; Moreira, E.D.; Zerbini, C.; et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 383, 2603–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimabukuro, T.T.; Kim, S.Y.; Myers, T.R.; Moro, P.L.; Oduyebo, T.; Panagiotakopoulos, L.; Marquez, P.L.; Olson, C.K.; Liu, R.; Chang, K.T.; et al. Preliminary findings of mRNA Covid-19 vaccine safety in pregnant persons. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 384, 2273–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanne, J.H. Covid-19: Vaccination during pregnancy is safe, finds large us study. BMJ 2022, 376, o27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, S.; Kalafat, E.; Blakeway, H.; Townsend, R.; O’Brien, P.; Morris, E.; Draycott, T.; Thangaratinam, S.; Le Doare, K.; Ladhani, S.; et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and perinatal outcomes of COVID-19 vaccination in pregnancy. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 2414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldshtein, I.; Nevo, D.; Steinberg, D.M.; Rotem, R.S.; Gorfine, M.; Chodick, G.; Segal, Y. Association between BNT162b2 vaccination and incidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in pregnant women. JAMA 2021, 326, 728–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dagan, N.; Barda, N.; Biron-Shental, T.; Makov-Assif, M.; Key, C.; Kohane, I.S.; Hernán, M.A.; Lipsitch, M.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Reis, B.Y.; et al. Effectiveness of the BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine in pregnancy. Nat. Med. 2021, 27, 1693–1695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Deng, J.; Liu, Q.; Du, M.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Effectiveness and safety of COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant women in real-world studies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccines 2022, 10, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halasa, N.B.; Olson, S.M.; Staat, M.A.; Newhams, M.M.; Price, A.M.; Boom, J.A.; Sahni, L.C.; Cameron, M.A.; Pannaraj, P.S.; Bline, K.E.; et al. Effectiveness of maternal vaccination with mRNA COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy against COVID-19-associated hospitalization in infants aged <6 months—17 states, July 2021–January 2022. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2022, 71, 264–270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Vaccines while Pregnant or Breastfeeding; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2022. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/pregnancy.html (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. COVID-19 Vaccination Considerations for Obstetric–Gynecologic Care; The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists: Washington, DC, USA, 2022; Available online: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/practice-advisory/articles/2020/12/covid-19-vaccination-considerations-for-obstetric-gynecologic-care# (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- World Health Organization. Questions and Answers: COVID-19 Vaccines and Pregnancy; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-FAQ-Pregnancy-Vaccines-2022.1 (accessed on 5 June 2022).

- Irving, S.A.; Ball, S.W.; Booth, S.M.; Regan, A.K.; Naleway, A.L.; Buchan, S.A.; Katz, M.A.; Effler, P.V.; Svenson, L.W.; Kwong, J.C.; et al. A multi-country investigation of influenza vaccine coverage in pregnant individuals, 2010–2016. Vaccine 2021, 39, 7598–7605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brixner, A.; Brandstetter, S.; Böhmer, M.M.; Seelbach-Göbel, B.; Melter, M.; Kabesch, M.; Apfelbacher, C.; KUNO-Kids study group. Prevalence of and factors associated with receipt of provider recommendation for influenza vaccination and uptake of influenza vaccination during pregnancy: Cross-sectional study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbeau, M.; Mulliez, A.; Chenaf, C.; Eschalier, B.; Lesens, O.; Vorilhon, P. Trends of influenza vaccination coverage in pregnant women: A ten-year analysis from a french healthcare database. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 7153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncu Ayhan, S.; Oluklu, D.; Atalay, A.; Menekse Beser, D.; Tanacan, A.; Moraloglu Tekin, O.; Sahin, D. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in pregnant women. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2021, 154, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egloff, C.; Couffignal, C.; Cordier, A.G.; Deruelle, P.; Sibiude, J.; Anselem, O.; Benachi, A.; Luton, D.; Mandelbrot, L.; Vauloup-Fellous, C.; et al. Pregnant women’s perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine: A French survey. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeway, H.; Prasad, S.; Kalafat, E.; Heath, P.T.; Ladhani, S.N.; Le Doare, K.; Magee, L.A.; O’Brien, P.; Rezvani, A.; von Dadelszen, P.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy: Coverage and safety. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 236.e1–236.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stock, S.J.; Carruthers, J.; Calvert, C.; Denny, C.; Donaghy, J.; Goulding, A.; Hopcroft, L.E.M.; Hopkins, L.; McLaughlin, T.; Pan, J.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 vaccination rates in pregnant women in Scotland. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 504–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaghi, H.; Meghani, M.; Pingali, C.; Crane, B.; Naleway, A.; Weintraub, E.; Kenigsberg, T.A.; Lamias, M.J.; Irving, S.A.; Kauffman, T.L.; et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage among pregnant women during pregnancy—eight integrated health care organizations, United States, December 14, 2020–May 8, 2021. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2021, 70, 895–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, D.; D’Alton, M.; Zhang, Y.; Kahe, K.; Cepin, A.; Goffman, D.; Staniczenko, A.; Yates, H.; Burgansky, A.; Coletta, J.; et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant, breastfeeding, and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. MFM 2021, 3, 100403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steffen, A.; Rieck, T.; Siedler, A. Monitoring of influenza vaccination coverage among pregnant women in Germany based on nationwide outpatient claims data: Findings for seasons 2014/15 to 2019/20. Vaccines 2021, 9, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Napolitano, F.; Napolitano, P.; Angelillo, I.F. Seasonal influenza vaccination in pregnant women: Knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in Italy. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eppes, C.; Wu, A.; You, W.; Cameron, K.A.; Garcia, P.; Grobman, W. Barriers to influenza vaccination among pregnant women. Vaccine 2013, 31, 2874–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, C.M.; Rench, M.A.; Montesinos, D.P.; Ng, N.; Swaim, L.S. Knowledge and attitiudes of pregnant women and their providers towards recommendations for immunization during pregnancy. Vaccine 2015, 33, 5445–5451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ditsungnoen, D.; Greenbaum, A.; Praphasiri, P.; Dawood, F.S.; Thompson, M.G.; Yoocharoen, P.; Lindblade, K.A.; Olsen, S.J.; Muangchana, C. Knowledge, attitudes and beliefs related to seasonal influenza vaccine among pregnant women in Thailand. Vaccine 2016, 34, 2141–2146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, B.S.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, W.J.; Wie, J.H.; Park, I.Y.; Ko, H.S. Influenza vaccination during pregnancy and influencing factors in Korea: A multicenter questionnaire study of pregnant women and obstetrics and gynecology doctors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, M.K.; Mehl, R.; Costantine, M.M.; Johnson, A.; Cohen, J.; Summerfield, T.L.; Landon, M.B.; Rood, K.M.; Venkatesh, K.K. Characteristics and perceptions associated with COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among pregnant and postpartum individuals: A cross-sectional study. BJOG 2022, 129, 1342–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skirrow, H.; Barnett, S.; Bell, S.; Riaposova, L.; Mounier-Jack, S.; Kampmann, B.; Holder, B. Women’s views on accepting COVID-19 vaccination during and after pregnancy, and for their babies: A multi-methods study in the UK. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2022, 22, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, O.A.; Halperin, O. Influenza virus vaccine compliance among pregnant women during the COVID-19 pandemic (pre-vaccine era) in Israel and future intention to uptake BNT162b2 mRNA COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisula, A.; Sienicka, A.; Pawlik, K.K.; Dobrowolska-Redo, A.; Kacperczyk-Bartnik, J.; Romejko-Wolniewicz, E. Pregnant women’s knowledge of and attitudes towards influenza vaccination during the COVID-19 pandemic in Poland. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tillion Pro. Available online: https://pro.tillionpanel.com/ (accessed on 12 October 2022).

- Im, J.H.; Choi, D.H.; Baek, J.; Kwon, H.Y.; Choi, S.R.; Chung, M.H.; Lee, J.S. Altered influenza vaccination coverage and related factors in pregnant women in Koea from 2007 to 2019. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2021, 36, e42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, E.; Brigden, A.; Davies, A.; Shepherd, E.; Ingram, J. Maternal vaccines during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative interview study with UK pregnant women. Midwifery 2021, 100, 103062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lumbreras Areta, M.; Valiton, A.; Diana, A.; Morales, M.; Wiederrecht-Gasser, J.; Jacob, S.; Chilin, A.; Quarta, S.; Jaksic, C.; Vallarta-Robledo, J.R.; et al. Flu and pertussis vaccination during pregnancy in Geneva during the COVID-19 pandemic: A multicentric, prospective, survey-based study. Vaccine 2022, 40, 3455–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jayagobi, P.A.; Ong, C.; Thai, Y.K.; Lim, C.C.; Jiun, S.M.; Koon, K.L.; Wai, K.C.; Chan, J.K.; Mathur, M.; Chien, C.M. Perceptions and acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine among pregnant and lactating women in Singapore: A cross-sectional study. medRxiv 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaal, N.K.; Zöllkau, J.; Hepp, P.; Fehm, T.; Hagenbeck, C. Pregnant and breastfeeding women’s attitudes and fears regarding the COVID-19 vaccination. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2022, 306, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skjefte, M.; Ngirbabul, M.; Akeju, O.; Escudero, D.; Hernandez-Diaz, S.; Wyszynski, D.F.; Wu, J.W. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among pregnant women and mothers of young children: Results of a survey in 16 countries. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 197–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, L.; Wang, R.; Han, N.; Liu, J.; Yuan, C.; Deng, L.; Han, C.; Sun, F.; Liu, M.; Liu, J. Acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine and associated factors among pregnant women in China: A multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2021, 17, 2378–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Tao, L.; Han, N.; Liu, J.; Yuan, C.; Deng, L.; Han, C.; Sun, F.; Chi, L.; Liu, M.; et al. Acceptance of seasonal influenza vaccination and associated factors among pregnant women in the context of COVID-19 pandemic in China: A multi-center cross-sectional study based on health belief model. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021, 21, 745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yudin, M.H.; Salripour, M.; Sgro, M.D. Impact of patient education on knowledge of influenza and vaccine recommendations among pregnant women. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2010, 32, 232–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goss, M.D.; Temte, J.L.; Barlow, S.; Temte, E.; Bell, C.; Birstler, J.; Chen, G. An assessment of parental knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs regarding influenza vaccination. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1565–1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilich, E.; Dada, S.; Francis, M.R.; Tazare, J.; Chico, R.M.; Paterson, P.; Larson, H.J. Factors that influence vaccination decision-making among pregnant women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0234827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantino, C.; Mazzucco, W.; Bonaccorso, N.; Cimino, L.; Conforto, A.; Sciortino, M.; Catalano, G.; D’Anna, M.R.; Maiorana, A.; Venezia, R.; et al. Educational interventions on pregnancy vaccinations during childbirth classes improves vaccine coverages among pregnant women in Palermo’s province. Vaccines 2021, 9, 1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavell, V.I.; Moniz, M.H.; Gonik, B.; Beigi, R.H. Influenza immunization in pregnancy: Overcoming patient and health care provider barriers. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 207, S67–S74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bödeker, B.; Walter, D.; Reiter, S.; Wichmann, O. Cross-sectional study on factors associated with influenza vaccine uptake and pertussis vaccination status among pregnant women in Germany. Vaccine 2014, 32, 4131–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.; McEntee, E.; Drew, R.; O’Reilly, F.; O’Carroll, A.; O’Shea, A.; Cleary, B. Influenza vaccination in pregnancy: Vaccine uptake, maternal and healthcare providers’ knowledge and attitudes. A quantitative study. BJGP Open 2018, 2, bjgpopen18X101599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhendyani, F.; Jolly, K.; Jones, L.L. Views and experiences of maternal healthcare providers regarding influenza vaccine during pregnancy globally: A systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, L.A.; Whipps, M.D.M.; Phipps, J.E.; Satish, N.S.; Swamy, G.K. Understanding COVID-19 vaccine uptake during pregnancy: ‘Hesitance’, knowledge, and evidence-based decision-making. Vaccine 2022, 40, 2755–2760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).