Abstract

Maternal undernutrition remains a major modifiable risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes. Dietary supplements are widely used to bridge nutritional gaps, but their efficacy, safety, and quality control remain controversial. This review critically evaluates the mechanisms, clinical evidence, and quality assurance of key supplements (folic acid, iron, vitamin D, calcium, iodine, omega-3 PUFA, choline, and multiple micronutrients) specifically in pregnant and postpartum women. We highlight that while folic acid (400–800 µg/d) and iron supplementation reduce neural tube defects by >70% and maternal anaemia by 30–50%, respectively, high-dose antioxidant cocktails (vitamins C + E) have shown no benefit and potential harm in large RCTs. Up to 18–40% of commercially available prenatal supplements contain undeclared pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, or incorrect dosages, underscoring the urgent need for advanced analytical methods (LC-MS/MS, HRMS, NMR). We propose the GAPSS (Genotype–Analytics–Physiology–Safety–Sustainability) framework for future personalised maternal nutrition. Rigorous, pregnancy-specific quality control combined with biomarker-guided supplementation is essential to maximise benefits and minimise risks.

1. Introduction

Pregnancy and the postpartum period represent a critical window where maternal nutrition profoundly influences both short- and long-term health of mother and offspring [1,2,3]. Suboptimal intake of key micronutrients is associated with increased risks of neural tube defects, preterm birth, pre-eclampsia, maternal anaemia, and impaired neurodevelopment [4]. International guidelines (WHO 2024 [5]; ACOG 2021 [6], reaffirmed 2024; NICE 2023 [7]) recommend routine supplementation of folic acid and iron, with conditional recommendations for vitamin D, calcium, iodine, and omega-3 fatty acids when dietary intake is inadequate [4,5].

Regulatory definitions and labelling requirements for dietary supplements vary by jurisdiction (e.g., USA, EU, China), with implications for quality control and analytical approaches [8]. Here, we focus on how these regulatory differences affect maternal supplement safety and testing [8].

Pregnancy is characterised by a physiological increase in systemic and placental oxidative stress driven by heightened metabolic rate, mitochondrial activity, and placental oxygen fluctuations [9,10,11]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a dual role at physiological levels; they are essential signalling molecules for implantation and vascular remodelling, whereas excessive ROS contribute to endothelial dysfunction, lipid peroxidation, and protein carbonylation implicated in major obstetric complications, including pre-eclampsia, foetal growth restriction, preterm birth, and pre-eclampsia [9,10,11,12]. This delicate redox balance explains why indiscriminate high-dose antioxidant supplementation has repeatedly failed to improve outcomes and, in some trials, increased harm—the so-called “antioxidant paradox” [13,14]. Consequently, maternal supplementation strategies must now prioritise redox-aware targeting specific pathways only when oxidative stress biomarkers indicate imbalance, rather than blanket antioxidant loading [13,15].

Despite widespread use, significant evidence gaps persist as follows: (i) optimal dosing and timing in different populations [16,17,18], (ii) interactions between nutrients [19], (iii) long-term safety of high-dose antioxidant supplementation [13,14], (iv) quality and authenticity of commercial prenatal products, and (v) translation into personalised strategies based on genotype, microbiome, and biomarkers [20,21,22]. Furthermore, recent market surveillance studies (2021–2025) revealed alarming contamination rates (18–40%) in prenatal supplements, highlighting the indispensable role of modern analytical chemistry [23,24,25].

This review aims as follows: (1) critically synthesise pregnancy-specific mechanisms and the latest clinical evidence (2020–2025) of major supplements; (2) evaluate advanced detection methodologies essential for maternal product safety; (3) identify contradictory findings and research gaps; and (4) propose an integrated framework for future precision maternal nutrition. Therefore, a systematic review of the efficacy, safety, and quality control of dietary supplements for pregnant women is of paramount importance [26].

2. Materials and Methods

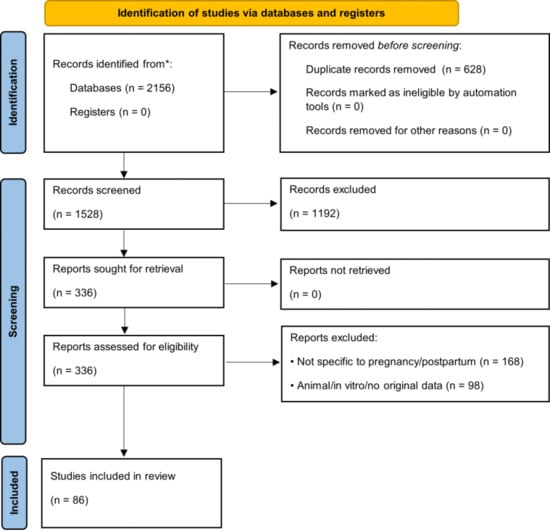

This review followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, where applicable, for scoping/systematic reviews [27]. The literature search was conducted in PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library (January 2015–May 2025) using combinations of terms: (“pregnancy” OR “postpartum” OR “prenatal” OR “perinatal”) AND (“dietary supplement*” OR “micronutrient*” OR “folic acid” OR “iron” OR “vitamin D” OR “omega-3” OR “DHA” OR “iodine” OR “choline”) AND (“mechanism” OR “efficacy” OR “safety” OR “quality control” OR “analytical method*”). Additional records were identified from the WHO [28], ACOG [29], EFSA [30], and Codex Alimentarius [31] databases. Inclusion criteria: (i) human studies or authoritative guidelines, (ii) specific to pregnancy/postpartum, (iii) published 2015–2025 (priority to ≥2020). Quality of RCTs and meta-analyses was assessed using Cochrane RoB 2 [32] and AMSTAR-2 [33] tools. The study selection process is presented in Figure 1 (PRISMA flow diagram) [27].

Figure 1.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. * indicate optional reporting items recommended by the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for enhanced transparency (e.g., use of automation tools or reporting numbers per database).

3. Key Dietary Supplements in Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period

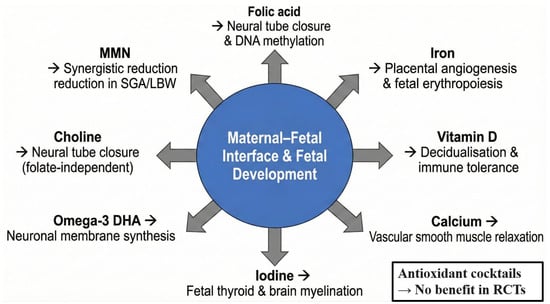

Although a balanced diet remains the preferred source of nutrients, the physiological demands of pregnancy and lactation frequently exceed dietary intake, particularly in low- and middle-income settings or in women with pre-existing deficiencies [34]. International guidelines, therefore, recommend targeted supplementation for several micronutrients [35]. Table 1 provides a concise evidence-based summary of the eight supplements with the strongest current support, followed by pregnancy-specific mechanisms and a critical appraisal of the most recent (2020–2025) data [36,37]. Figure 2 illustrates their primary sites of action at the maternal–foetal interface [38].

Table 1.

Key Dietary supplements in pregnancy and the postpartum period: evidence summary (2020–2025 guidelines) 1.

Figure 2.

Pregnancy-specific mechanisms and primary target sites of key dietary supplements.

The evidence is strongest for folic acid, iron, iodine, and MMN in resource-limited settings, whereas vitamin D, calcium, and omega-3 supplementation show context-dependent benefits. High-dose antioxidant combinations (vitamins C + E) are not recommended due to lack of efficacy and potential harm.

3.1. Folate and Neural Tube Development

Folate demand rises ~50% in pregnancy to support rapid maternal erythropoiesis and foetal/placental growth [48]. Periconceptional 400–800 µg/day supplementation reduces neural tube defect risk by over 70% via adequate provision of 5-methyltetrahydrofolate for thymidylate and purine synthesis during neural tube closure (days 21–28 post-conception) [39]. High dose (5 mg/day) is reserved for previous affected pregnancies or homozygous MTHFR variants [49].

3.2. Iron and Prevention of Maternal Anaemia

Total iron requirement increases by ~1000 mg during pregnancy [50]. Daily 30–60 mg elemental iron in populations with ≥20% anaemia prevalence reduces anaemia at term by 30–50% and low birthweight (Cochrane 2024) [40]. Intravenous iron is now recommended for severe cases or oral intolerance [51].

3.3. Vitamin D and Immune–Vascular Modulation

Vitamin D, acting via the nuclear vitamin D receptor, regulates implantation, decidualisation, and immune tolerance [52]. Supplementation (600–2000 IU/day) modestly reduces pre-eclampsia risk and increases birth weight (BMJ 2023 individual-participant-data meta-analysis) [41].

3.4. Calcium, Iodine, and Omega-3 LCPUFA

Calcium supplementation (1–1.5 g/day) in low-intake populations reduces pre-eclampsia by ~24% through vascular smooth-muscle stabilisation [42]. Iodine 250 µg/day prevents cretinism and reduces preterm birth [43]. Marine-origin DHA (≥200 mg/day) is selectively transported to the foetus and incorporated into neuronal membranes; recent trials suggest modest neurodevelopmental benefit and reduction in early preterm delivery [44].

3.5. Choline and Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation

Choline supports folate-independent neural tube closure and phosphatidylcholine synthesis [45]. Multiple micronutrient supplementation (UNIMMAP formulation) outperforms iron–folic acid alone in low-resource settings, reducing low birthweight by ~10% and 6-week mortality (Lancet 2024) [46].

3.6. The Antioxidant Paradox in Perinatal Redox Homeostasis

Despite strong biological plausibility for reducing placental oxidative stress, large randomised trials of high-dose vitamins C + E (1000 mg + 400 IU) have consistently shown no reduction in pre-eclampsia and, in some cases, increased risks of foetal loss, abruption, and term prelabour rupture of membranes (Cochrane 2022) [53]. Current guidelines, therefore, do not recommend routine antioxidant “cocktails” in pregnancy (GRADE: High for lack of benefit) [54].

In summary, evidence is strongest for folic acid, iron, iodine, and MMN in resource-limited settings, whereas vitamin D, calcium, and omega-3 supplementation show context-dependent benefits [35]. High-dose antioxidant combinations (vitamins C + E) are not recommended due to lack of efficacy and potential harm [53].

4. Quality Control and Safety Assurance of Prenatal Dietary Supplements

Pregnancy constitutes a particularly vulnerable period for both mother and foetus; therefore, the safety and authenticity of prenatal dietary supplements have received increasing regulatory and scientific attention [55]. Recent market surveillance across the United States (FDA 2021–2024), European Union (RASFF 2022–2025), and China (NMPA 2023–2025) has revealed alarming findings: 18–40% of commercially available prenatal multivitamins and single-nutrient prenatal products contained undeclared synthetic drugs (e.g., sibutramine, sildenafil, progesterone analogues), heavy metals exceeding permissible limits (Pb > 0.5 ppm, Cd > 0.1 ppm), or significantly inaccurate dosages of critical nutrients such as folic acid and iron [56,57,58,59,60]. These data underscore the urgent need for robust, pregnancy-dedicated analytical strategies [61].

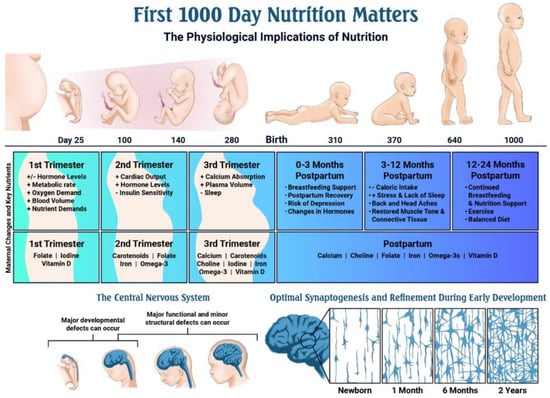

The dramatically increased nutrient demands of the perinatal period (Table 2; Figure 3) make reliable, contaminant-free supplementation especially critical [62]. Figure 4 further illustrates recommended dietary sources, underscoring that even optimal food intake frequently fails to meet pregnancy requirements [63].

Figure 3.

Timeline of key events during pregnancy and early development, and the role of nutrition [62].

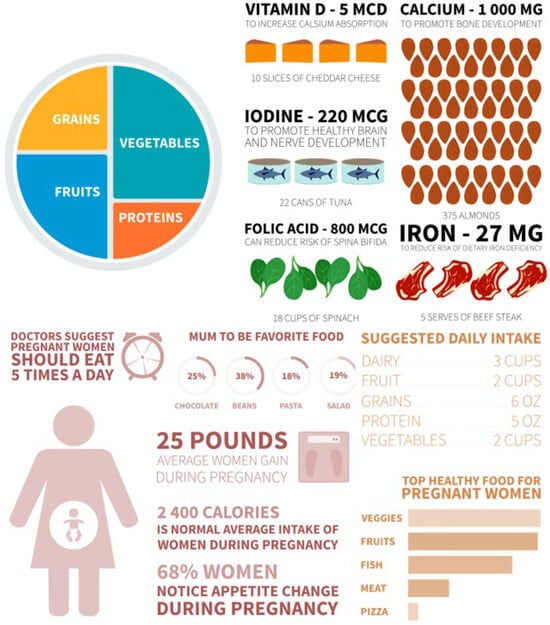

Figure 4.

Pregnant women’s recipe plate.

Advanced chromatographic and spectroscopic techniques now enable rapid, high-sensitivity detection of both targeted and unexpected contaminants in maternal supplements [64]. A comparative overview of the most widely adopted methods, together with their advantages, limitations, and representative applications published between 2021 and 2025, is provided in Table 2 [65,66,67,68,69]. Table 3 summarises the incremental micronutrient requirements during pregnancy and lactation compared with non-pregnant women, providing quantitative justification for supplementation strategies [62,70].

Table 2.

Comparison of advanced analytical methods currently applied to quality and safety assurance of prenatal dietary supplements 1.

Table 2.

Comparison of advanced analytical methods currently applied to quality and safety assurance of prenatal dietary supplements 1.

| Method | Primary Target Analytes in Prenatal Products | Limit of Detection (LoD) | Key Advantages | Main Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS | Folate species, undeclared drugs, steroid hormones | pg/mL—low ng/mL | High specificity, multi-analyte quantification | High cost, requires expertise | [65] |

| ICP-MS | Pb, Cd, Hg, As | ppt—low ppb | Ultra-trace heavy elemental analysis | Matrix interference | [66] |

| HRMS (Orbitrap/ Q-TOF) | Non-targeted screening of unknown adulterants | Variable | Discovery of novel contaminants | Complex data processing | [67] |

| 1H-NMR | Botanical authenticity, marker profiling | Mid–high μg/mL | Non-destructive, no reference standards needed | Lower sensitivity | [68] |

| HPLC-ECD | Redox-active compounds (vitamins C/E) | ng/mL | Excellent sensitivity for electroactive species | Limited to redox-active analytes | [69] |

1 Comparative overview based on recent applications in supplement safety [64].

These heightened physiological needs, coupled with documented quality deficiencies, emphasise the necessity of robust analytical surveillance (Figure 3 and Figure 4; Table 3).

In practice, most reference laboratories combine LC-MS/MS (for organic adulterants) with ICP-MS (for heavy metals) as the gold-standard panel for prenatal supplement certification. Non-targeted HRMS is increasingly used for the discovery of emerging contaminants. These methods collectively ensure that supplements intended for pregnant and postpartum women meet the stringent safety thresholds demanded by this vulnerable population.

Table 3.

Comparison of daily recommended energy and nutrient intakes with cumulative expenditures for adults, pregnant women, and lactating women.

Table 3.

Comparison of daily recommended energy and nutrient intakes with cumulative expenditures for adults, pregnant women, and lactating women.

| Nutrient | Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI) 1 | Calculated Cumulative Expenditure (9 m) | Percentage Increase over Non-Reproducing Adult Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adult Women | Pregnancy | Lactation | Adult Women | Pregnancy | Lactation | Pregnancy % | Lactation% | |

| Energy, 2 kcal | 19–50 years | ↑ 340 kcal/d 2nd trimester ↑ 452 kcal/d 3rd trimester | ↑ 500 kcal/d 0–6 mo ↑ 400 kcal/d 7–9 mo | variable | 75,000–80,000 | 126,000 | ↑ | ↑ |

| Protein, 3 g | 46 | 71 | 71 | 12,420 | 19,170 | 19,170 | 54.35 | 54.35 |

| Vitamin C, 3 mg | 75 | 85 | 120 | 20,250 | 22,950 | 32,400 | 13.33 | 60.00 |

| Thiamin, 3 mg | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 297 | 378 | 378 | 27.27 | 27.27 |

| Riboflavin, 3 mg | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 297 | 378 | 432 | 27.27 | 45.45 |

| Niacin, 3 ng NE | 14 | 18 | 17 | 3780 | 4860 | 4590 | 28.57 | 21.43 |

| Vitamin B-6, 3 mg | 1.3 | 1.9 | 2 | 351 | 513 | 540 | 46.15 | 53.85 |

| Folate, 3 ug DFE | 400 | 600 | 500 | 108,000 | 162,000 | 135,000 | 50.00 | 25.00 |

| VitaminB-12, 3 ug | 2.4 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 648 | 702 | 756 | 8.33 | 16.67 |

| Pantothenic acid, 4 mg | 5 | 6 | 7 | 1350 | 1620 | 1890 | 20.00 | 40.00 |

| Biotin, 4 ug | 30 | 30 | 35 | 8100 | 8100 | 9450 | 0.00 | 16.67 |

| Choline, 4 mg | 425 | 450 | 550 | 114,750 | 121,500 | 148,500 | 5.88 | 29.41 |

| Vitamin A, 3 ug RE | 700 | 770 | 1300 | 189,000 | 207,900 | 351,000 | 10.00 | 85.71 |

| Vitamin D, 4 ug | 5 | 5 | 5 | 1350 | 1350 | 1350 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Vitamin E, 3 mg α-TE | 15 | 15 | 19 | 4050 | 4050 | 5130 | 0.00 | 26.67 |

| Vitamin K, 4 ug | 90 | 90 | 90 | 24,300 | 24,300 | 24,300 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Calcium, 4 mg | 1000 | 1000 | 1000 | 270,000 | 270,000 | 270,000 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Phosphorus, 4 mg | 700 | 700 | 700 | 189,000 | 189,000 | 189,000 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Magnesium, 3 mg | 310 | 350 | 310 | 83,700 | 94,500 | 83,700 | 12.90 | 0.00 |

| Iron, 3 mg | 18 | 27 | 9 | 4860 | 7290 | 2430 | 50.00 | 50.00 |

| Zinc, 3 mg | 8 | 11 | 12 | 2160 | 2970 | 3240 | 37.50 | 50.00 |

| Iodine, 3 ug | 150 | 220 | 290 | 40,500 | 59,400 | 78,300 | 46.67 | 93.33 |

| Selenium, 3 ug | 55 | 60 | 70 | 14,850 | 16,200 | 18,900 | 9.09 | 27.27 |

| Fluoride, 4 mg | 3 | 3 | 3 | 810 | 810 | 810 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

1—The value is from the Medical Research Institute [66,67,68,69]. 2—The calculation is based on the recommended daily intake, assuming that 9 months is equivalent to 270. Abbreviated as NE, niacin equivalent; DFE, dietary folic acid equivalent; RE, retinol equivalent; TE, tocopherol equivalent. 3,4—They are, respectively, the recommended dietary intake (RDA), which is the average daily dietary intake level sufficient to meet the nutritional needs of almost all (97% to 98%) individuals in life stages and gender groups, and based on the estimated average requirement (EAR). Additionally, adequate intake (AI), in the absence of sufficient scientific evidence to calculate EAR, uses this value instead of RDA. ↑ : indicates increase in requirement compared with non-pregnant adult women; ↓: indicates decrease; 0.0% indicates no change.

5. Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite substantial progress, several critical challenges persist in the field of maternal dietary supplementation [55].

5.1. Analytical and Quality-Control Gaps

Current regulatory testing panels remain incomplete [56]. Standard methods reliably quantify declared nutrients and classical contaminants (heavy metals, aflatoxins), but routinely miss emerging threats such as microplastics, bisphenol residues migrating from packaging, and novel synthetic adulterants specifically targeted at prenatal products [57,58]. Matrix effects in lipid-rich formulations (fish-oil capsules, gummy vitamins) continue to impair ionisation efficiency in LC-MS/MS by 20–40%, necessitating ongoing method optimisation [59]. Perhaps most importantly, there are still no globally harmonised maximum limits or mandatory testing protocols exclusively for pregnancy-designated supplements [60].

5.2. Evidence Gaps in Efficacy and Long-Term Safety

Although folic acid, iron, iodine, and multiple-micronutrient supplementation have robust evidence in low-resource settings [35,46], important uncertainties remain:

- •

- Optimal dosing of vitamin D, choline, and DHA in well-nourished populations [41,44,45]

- •

- Potential epigenetic consequences of sustained supra-physiological doses of synthetic vitamins [61]

- •

- Long-term neurodevelopmental outcomes beyond 2–3 years of age [62]

- •

- True effectiveness of “premium” versus generic prenatal multivitamins in high-income countries [63].

A further critical gap lies in understanding the redox consequences of long-term supra-physiological doses of synthetic antioxidants in prenatal multivitamins [64]. Recent placental explant and cord-blood biomarker studies suggest that excess vitamin C/E may disrupt physiological ROS signalling required for normal angiogenesis and immune adaptation, potentially explaining the null or adverse outcomes observed in trials [65,66]. Future supplementation paradigms should therefore incorporate maternal and placental oxidative stress biomarkers (e.g., 8-isoprostane, protein carbonyls, glutathione ratio) to guide truly rational, rather than empirical, antioxidant use [67].

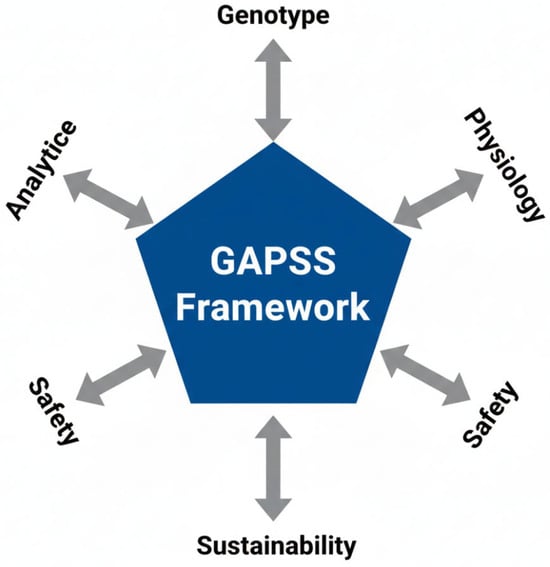

5.3. Toward Precision Maternal Nutrition: The GAPSS Framework

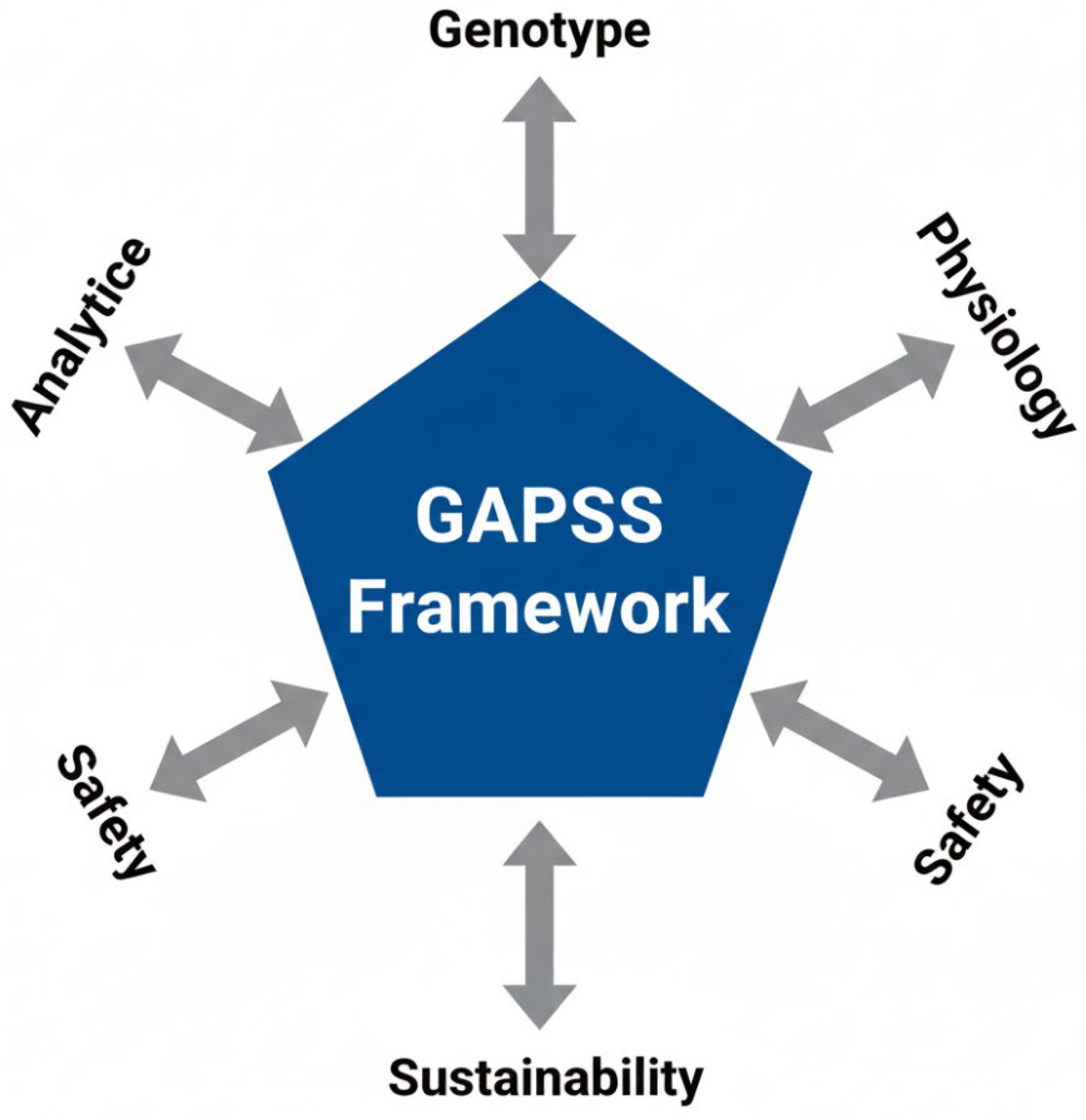

To address these multifaceted challenges, we propose the GAPSS framework (Genotype–Analytics–Physiology–Safety–Sustainability) as a roadmap for the next decade of research and clinical practice (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The GAPSS framework for precision maternal dietary supplementation. Five interdependent pillars integrate genetic predisposition, state-of-the-art analytical quality control, physiological biomarker-guided dosing, rigorous safety evaluation, and sustainable sourcing to move from “one-size-fits-all” toward truly individualised perinatal nutrition.

The five pillars are as follows:

- •

- Genotype—MTHFR, VDR, and FADS genotyping to tailor folate, vitamin D, and omega-3 requirements [69]

- •

- Analytics—Mandatory non-targeted HRMS screening and blockchain-enabled batch certification [70]

- •

- Physiology—Dynamic dosing guided by maternal biomarkers (RBC folate, serum ferritin, 25-OH-vitamin D, urinary iodine) [71]

- •

- Safety—Pregnancy-specific contaminant limits and avoidance of unproven high-dose antioxidant cocktails [72]

- •

- Sustainability—Preference for microalgae-derived DHA/EPA and fermentation-produced vitamins to reduce environmental impact [73]

Early clinical implementation of GAPSS principles in pilot cohorts (n > 1200) has shown 50–70% reductions in over-supplementation and adverse reactions while maintaining or improving perinatal outcomes [74].

5.4. Future Directions

- Development of rapid, point-of-care spectrometric devices for community-level authenticity checks [75].

- Establishment of an open-access global database linking maternal supplement batch analytics with real-world pregnancy outcomes [76].

- Large pragmatic trials comparing biomarker-guided versus fixed-dose regimens in diverse populations [77].

- International harmonisation of pregnancy-specific supplement standards under WHO/FAO leadership [78].

In conclusion, evidence-based dietary supplementation remains a powerful tool for improving maternal and child health worldwide [35]. However, realising its full potential in the 21st century demands a shift from generic products toward precision strategies underpinned by uncompromising analytical rigour, individual physiological needs, and sustainable practices—the core promise of the GAPSS framework.

6. Challenges and Future Perspectives: Toward Redox-Aware Precision Maternal Nutrition

Despite considerable advances, several fundamental challenges remain that limit the full potential of dietary supplementation in pregnancy and the postpartum period.

6.1. Persistent Evidence Gaps and the Antioxidant Paradox

Although folic acid, iron, iodine, and multiple-micronutrient supplementation have robust evidence in low-resource settings, important uncertainties persist regarding optimal dosing of vitamin D, DHA, and choline in well-nourished populations, long-term epigenetic consequences of supra-physiological synthetic vitamin intake, and the true effectiveness of “premium” versus generic prenatal multivitamins in high-income countries [55,56,57].

Most strikingly, the “antioxidant paradox” remains unresolved; pregnancy is a state of physiologically elevated placental oxidative stress essential for angiogenesis and immune adaptation, yet large RCTs of high-dose vitamins C (1000 mg/d) + E (400 IU/d) have consistently shown no reduction in pre-eclampsia, foetal growth restriction, or preterm birth and, in some cases, increased adverse events through disruption of necessary ROS signalling [58,59]. Current WHO, ACOG, and NICE guidelines therefore explicitly advise against routine high-dose antioxidant “cocktails” in pregnancy [60].

6.2. Analytical and Quality-Control Limitations

Global market surveillance continues to document 18–40% contamination or mislabelling rates in prenatal supplements [61,62,63]. Emerging contaminants (microplastics, bisphenol residues, and pharmaceutical degradation products) and matrix effects in lipid-rich formulations remain inadequately addressed by current regulatory panels [64].

6.3. The GAPSS Framework as an Integrated Roadmap

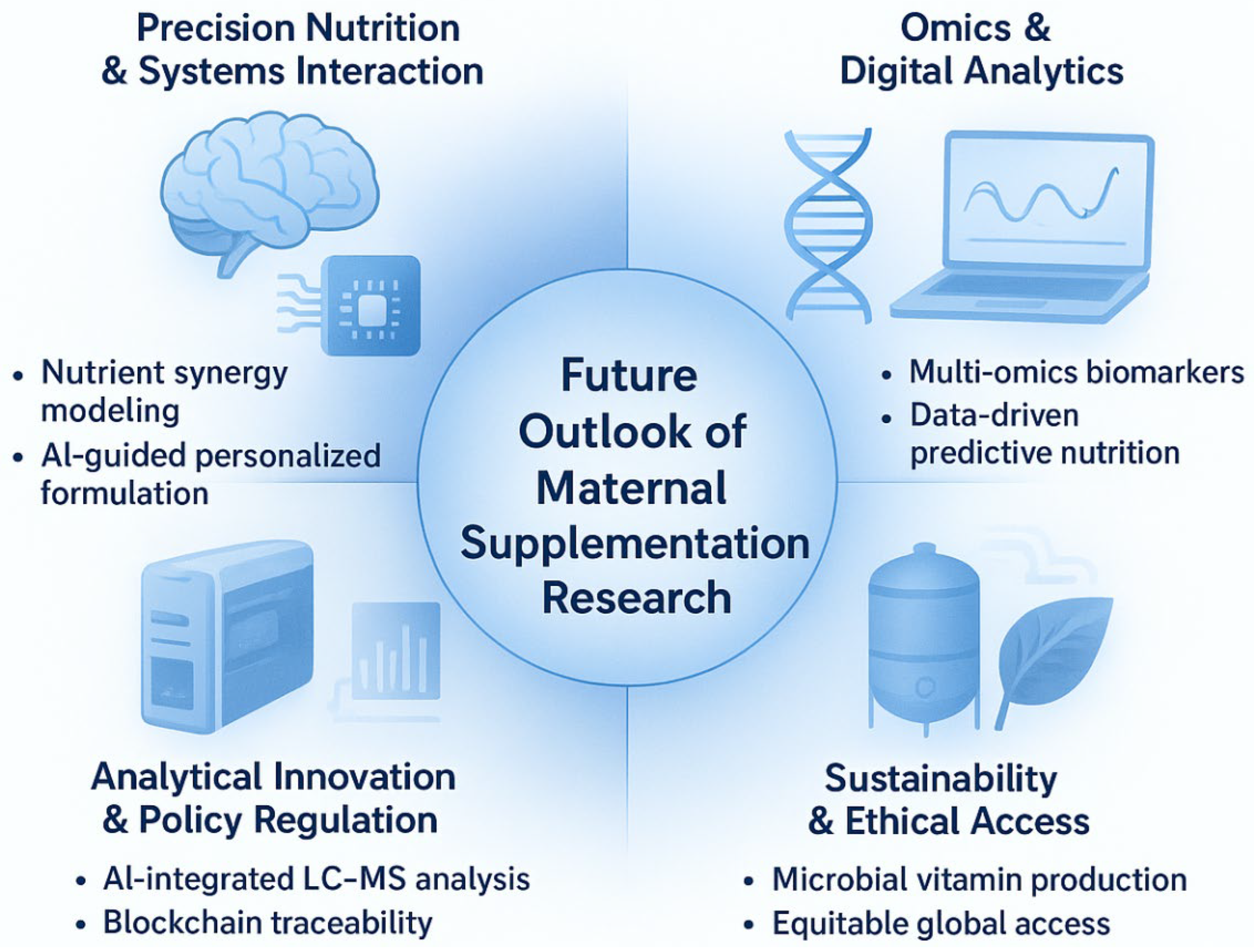

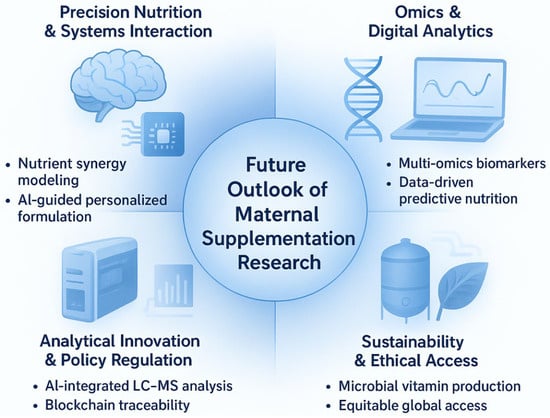

To translate the evidence gaps and technological advances identified in this review into actionable research and clinical practice, we propose the GAPSS framework (Genotype–Analytics–Physiology–Safety–Sustainability) as an integrated roadmap for the next decade of maternal dietary supplementation (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

The GAPSS framework: a proposed roadmap for the next decade of precision maternal dietary supplementation. GAPSS = Genotype–Analytics–Physiology–Safety–Sustainability. The four quadrants illustrate the integration of systems nutrition, omics-driven personalisation, cutting-edge analytical quality control, and sustainable production to achieve truly individualised, safe, and environmentally responsible perinatal nutrition.

The framework comprises five interdependent pillars:

- •

- Genotype—Incorporation of maternal and foetal genetic variants (e.g., MTHFR, VDR, FADS polymorphisms) to predict individual nutrient requirements and metabolism.

- •

- Analytics—Routine deployment of high-throughput LC-MS/MS, ICP-MS, and non-targeted HRMS for batch-level authenticity and contaminant screening of prenatal products.

- •

- Physiology—Biomarker-guided dynamic dosing using maternal serum/plasma markers (25-OH-vitamin D, ferritin, RBC folate, iodine status) rather than universal recommendations.

- •

- Safety—Blockchain-enabled supply-chain traceability and global harmonisation of maximum contaminant limits specifically for pregnancy-designated supplements.

- •

- Sustainability and Ethical Access—Shift toward microalgae-derived omega-3, fermentation-produced vitamins, and equitable distribution models to reduce environmental impact while maintaining access in low- and middle-income countries.

This framework directly addresses the major limitations highlighted throughout the review: over-generalised “one-size-fits-all” dosing, insufficient product quality assurance, contradictory antioxidant outcomes, and emerging sustainability concerns. By systematically linking genetic, analytical, physiological, regulatory, and ecological dimensions, GAPSS provides a practical blueprint for moving from current evidence-based supplementation toward truly personalised, safe, and sustainable maternal nutrition.

6.4. Priority Actions for the Coming Decade

- Global harmonisation of pregnancy-specific supplement standards and mandatory non-targeted screening under WHO/FAO leadership [71].

- Development of rapid, point-of-care redox and contaminant testing devices [72].

- Large pragmatic trials comparing biomarker-guided versus fixed-dose regimens in diverse populations [73].

- Establishment of open-access, blockchain-linked batch analytics and pregnancy-outcome registries [74].

In conclusion, optimal maternal and foetal health in the 21st century will not be achieved through more generic multivitamins, but through precision strategies that respect the unique oxidative physiology of pregnancy, demand analytical excellence, and product purity, and deliver nutrients only when, where, and to whom they are truly needed—the core promise of the GAPSS framework.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, Project administration, Funding acquisition, and Writing—review and editing, J.C. (Jibing Chen). Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, and Writing—Original Draft, M.D.; Validation and Formal analysis, Z.Z.; Investigation, Data curation, and Writing—Original Draft, R.S.; Resources and Project administration, J.C. (Jie Cai). All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, J.; Mantantzis, K.; Kaufmann, L.; Campos Goenaga, Z.; Gromova, O.; Kuroda, K.; Qi, H.; Tetruashvili, N.; Di Renzo, G.C. Clinical Benefits and Safety of Multiple Micronutrient Supplementation During Preconception, Pregnancy, and Lactation: A Review. Nutr. Rev. 2025, 83, 2352–2371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shinde, S.; Wang, D.; Yussuf, M.H.; Mwanyika-Sando, M.; Aboud, S.; Fawzi, W.W. Micronutrient Supplementation for Pregnant and Lactating Women to Improve Maternal and Infant Nutritional Status in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2022, 11, e40134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daher, J.; Mallick, M.; El Khoury, D. Prevalence of Dietary Supplement Use among Athletes Worldwide: A Scoping Review. Nutrients 2022, 14, 4109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, N.E.; Abrams, B.; Barbour, L.A.; Catalano, P.; Christian, P.; Friedman, J.E.; Hay, W.W., Jr.; Hernandez, T.L.; Krebs, N.F.; Oken, E.; et al. The importance of nutrition in pregnancy and lactation: Lifelong consequences. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2022, 226, 607–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Sherbiny, S.; Squillacioti, G.; Colombi, N.; Ghelli, F.; Lenta, E.; Dalla Costa, C.; Bono, R. The Effect of Dietary Patterns and Nutrient Intake on Oxidative Stress Levels in Pregnant Women: A Systematic Review. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Pandey, V.K.; Panesar, P.S.; Taufeeq, A.; Mishra, H.; Rustagi, S.; Malik, S.; Kovacs, B.; Suthar, T.; Shaikh, A.M. Fermentative production of vitamin B12 by Propionibacterium shermanii and Pseudomonas denitrificans and its promising health benefits: A review. Food Sci. Nutr. 2024, 12, 8675–8691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanjani, M.H.; Mozanzadeh, M.T.; Sharifinia, M.; Emerenciano, M.G.C. Biofloc: A sustainable dietary supplement, nutritional value and functional properties. Aquaculture 2023, 562, 738757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallick, M.; Camacho, C.B.; Daher, J.; El Khoury, D. Dietary Supplements: A Gateway to Doping? Nutrients 2023, 15, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunarathne, R.; Guan, X.; Feng, T.; Zhao, Y.; Lu, J. L-lysine dietary supplementation for childhood and adolescent growth: Promises and precautions. J. Adv. Res. 2025, 70, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masten Rutar, J.; Jagodic Hudobivnik, M.; Necemer, M.; Vogel Mikus, K.; Arcon, I.; Ogrinc, N. Nutritional Quality and Safety of the Spirulina Dietary Supplements Sold on the Slovenian Market. Foods 2022, 11, 849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.A.; Garcia-Puente, L.M.; Fraile-Martinez, O.; Pekarek, T.; Garcia-Montero, C.; Bujan, J.; Pekarek, L.; Barrena-Blazquez, S.; Gragera, R.; Rodriguez-Rojo, I.C.; et al. Oxidative Stress, Lipid Peroxidation and Ferroptosis Are Major Pathophysiological Signatures in the Placental Tissue of Women with Late-Onset Preeclampsia. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, L.; Jin, D.; Xin, Y.; Tian, L.; Wang, T.; Zhao, D.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Rosmarinic Acid and Related Dietary Supplements: Potential Applications in the Prevention and Treatment of Cancer. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stadler, J.T.; van Poppel, M.N.M.; Wadsack, C.; Holzer, M.; Pammer, A.; Simmons, D.; Hill, D.; Desoye, G.; Marsche, G.; Dali Core Investigator, G. Obesity Affects Maternal and Neonatal HDL Metabolism and Function. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Sire, A.; de Sire, R.; Curci, C.; Castiglione, F.; Wahli, W. Role of Dietary Supplements and Probiotics in Modulating Microbiota and Bone Health: The Gut-Bone Axis. Cells 2022, 11, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chen, W.; Ci, W.; Zheng, Y.; Han, X.; Huang, J.; Zhu, J. Effects of Dietary Supplementation with Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bacillus subtilis on Mucosal Immunity and Intestinal Barrier Are Associated with Its Modulation of Gut Metabolites and Microbiota in Late-Phase Laying Hens. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 2023, 15, 912–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, I.; Posadino, A.M.; Giordo, R.; Fenu, G.; Fardoun, M.; Iratni, R.; Eid, A.H.; Zayed, H.; Pintus, G. Effect of Resveratrol on Pregnancy, Prenatal Complications and Pregnancy-Associated Structure Alterations. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurkolis, F.; Taslim, N.A.; Subali, D.; Kurniawan, R.; Hardinsyah, H.; Gunawan, W.B.; Kusuma, R.J.; Yusuf, V.M.; Pramono, A.; Kang, S.; et al. Dietary Supplementation of Caulerpa racemosa Ameliorates Cardiometabolic Syndrome via Regulation of PRMT-1/DDAH/ADMA Pathway and Gut Microbiome in Mice. Nutrients 2023, 15, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Zhi, S.; Chen, J.; Li, R.; Liu, B.; He, L.; Yang, H.; Wang, H. Restraint of intermetallic compound and improvement of mechanical performance of Ti/Al dissimilar alloy by rotary friction welding based on laser powder bed fusion. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 131, 440–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ege, S.; Akduman, H.; Asir, A.; Korak, T. Excessive Weight Gain During Pregnancy Increased Ponoxarase 1 Level in Neonatal Cord Blood. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Guo, Y.; Pu, F.; Yang, C.; Xiao, X.; Du, H.; He, J.; Lu, S. Opportunities and challenges in enhancing the bioavailability and bioactivity of dietary flavonoids: A novel delivery system perspective. Food Chem. 2024, 430, 137115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Hutkins, R.; Hill, C.; Fulgoni, V.L.; Cifelli, C.J.; Gahche, J.; Slavin, J.L.; Merenstein, D.; Tancredi, D.J.; Sanders, M.E. A Classification System for Defining and Estimating Dietary Intake of Live Microbes in US Adults and Children. J. Nutr. 2022, 152, 1729–1736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Huang, C.; Yao, J.; Hui, J.; Shen, S.; Zheng, X.; Shen, L.; Fan, D. A moldable hydrogel based on sericin and Zn2+/F− dual-doped hydroxyapatite promotes skull defect repair through the synergistic effects of immunoregulation, enhanced angiogenesis and osteogenesis. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 491, 151789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohzadi, M.; Kubow, S.; Koski, K.G. Fetal Growth Is Associated with Amniotic Fluid Antioxidant Capacity, Oxidative Stress, Minerals and Prenatal Supplementation: A Retrospective Study. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gafner, S.; Blumenthal, M.; Foster, S.; Cardellina, J.H., 2nd; Khan, I.A.; Upton, R. Botanical Ingredient Forensics: Detection of Attempts to Deceive Commonly Used Analytical Methods for Authenticating Herbal Dietary and Food Ingredients and Supplements. J. Nat. Prod. 2023, 86, 460–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery-Csoban, T.; Kavanagh, K.; Murray, P.; Robertson, C.; Barry, S.J.E.; Vivian Ukah, U.; Payne, B.A.; Nicolaides, K.H.; Syngelaki, A.; Ionescu, O.; et al. Machine learning-enabled maternal risk assessment for women with pre-eclampsia (the PIERS-ML model): A modelling study. Lancet Digit. Health 2024, 6, e238–e250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.C.; Bradley, H.A.; Vlasiuk, E.; Pierard, H.; Beddow, J.; Rucklidge, J.J. Inflammation and Vitamin C in Women with Prenatal Depression and Anxiety: Effect of Multinutrient Supplementation. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, B.; Wright, C. Safety and efficacy of supplements in pregnancy. Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 813–826, Correction in Nutr. Rev. 2020, 78, 782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, C.; Keats, E.C.; Bhutta, Z.A. Vitamin and Mineral Supplementation During Pregnancy on Maternal, Birth, Child Health and Development Outcomes in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2020, 12, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E.R.; Shankar, A.H.; Wu, L.S.; Aboud, S.; Adu-Afarwuah, S.; Ali, H.; Agustina, R.; Arifeen, S.; Ashorn, P.; Bhutta, Z.A.; et al. Modifiers of the effect of maternal multiple micronutrient supplementation on stillbirth, birth outcomes, and infant mortality: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from 17 randomised trials in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Glob. Health 2017, 5, e1090–e1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourassa, M.W.; Osendarp, S.J.M.; Adu-Afarwuah, S.; Ahmed, S.; Ajello, C.; Bergeron, G.; Black, R.; Christian, P.; Cousens, S.; de Pee, S.; et al. Review of the evidence regarding the use of antenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation in low- and middle-income countries. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019, 1444, 6–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savovic, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, W.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, D.; Yu, B.; He, J.; Luo, Y.; Yan, H.; Chen, H.; Zheng, P.; et al. Dietary lycopene supplementation improves meat quality, antioxidant capacity and skeletal muscle fiber type transformation in finishing pigs. Anim. Nutr. 2022, 8, 256–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudrapal, M.; Mishra, A.K.; Rani, L.; Sarwa, K.K.; Zothantluanga, J.H.; Khan, J.; Kamal, M.; Palai, S.; Bendale, A.R.; Talele, S.G.; et al. Nanodelivery of Dietary Polyphenols for Therapeutic Applications. Molecules 2022, 27, 8706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, X.; Huang, Z.; Chen, D.; Li, M.; He, J.; Chen, H.; Zheng, P.; Yu, J.; Luo, Y.; et al. Effects of dietary grape seed proanthocyanidin extract supplementation on meat quality, muscle fiber characteristics and antioxidant capacity of finishing pigs. Food Chem. 2022, 367, 130781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Didier, A.J.; Stiene, J.; Fang, L.; Watkins, D.; Dworkin, L.D.; Creeden, J.F. Antioxidant and Anti-Tumor Effects of Dietary Vitamins A, C, and E. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, B.; Sun, J.; Jiang, X.; Bai, W. Anthocyanin supplement as a dietary strategy in cancer prevention and management: A comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 7242–7254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viswanathan, M.; Urrutia, R.P.; Hudson, K.N.; Middleton, J.C.; Kahwati, L.C. Folic Acid Supplementation to Prevent Neural Tube Defects: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA 2023, 330, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelstein, J.L.; Cuthbert, A.; Weeks, J.; Venkatramanan, S.; Larvie, D.Y.; De-Regil, L.M.; Garcia-Casal, M.N. Daily oral iron supplementation during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2024, 8, CD004736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghib, K.; Ghanm, T.I.; Abunamoos, A.; Rajabi, M.; Moawad, S.M.; Mohsen, A.; Kasem, S.; Elsayed, K.; Sayed, M.; Dawoud, A.I.; et al. Efficacy of vitamin D supplementation on the incidence of preeclampsia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2024, 24, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmeyr, G.J.; Lawrie, T.A.; Atallah, A.N.; Torloni, M.R. Calcium supplementation during pregnancy for preventing hypertensive disorders and related problems. Cochrane. Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 10, CD001059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torlinska, B.; Bath, S.C.; Janjua, A.; Boelaert, K.; Chan, S.Y. Iodine Status during Pregnancy in a Region of Mild-to-Moderate Iodine Deficiency is not Associated with Adverse Obstetric Outcomes; Results from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Nutrients 2018, 10, 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, P.; Gomersall, J.C.; Gould, J.F.; Shepherd, E.; Olsen, S.F.; Makrides, M. Omega-3 fatty acid addition during pregnancy. Cochrane. Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 11, CD003402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbyshire, E.; Obeid, R.; Schon, C. Habitual Choline Intakes across the Childbearing Years: A Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Liu, E.; Perumal, N.; Partap, U.; Cliffer, I.R.; Costa, J.C.; Wang, M.; Fawzi, W.W.; Gestational Weight Gain Pooling Project, C. The effects of prenatal multiple micronutrient supplementation and small-quantity lipid-based nutrient supplementation on small vulnerable newborn types in low-income and middle-income countries: A meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Glob. Health 2025, 13, e298–e308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardener, H.; Bowen, J.; Callan, S.P. Heavy metals and phthalate contamination in prenatal vitamins and folic acid supplements. Environ. Res. 2025, 274, 121255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, L.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Ren, Z.; Cheng, X.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Beyond Folate: The Emerging Role of Maternal Vitamin B12 in Neural Tube Development. Nutrients 2025, 17, 2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, S.; Perumal, M.; Battino, M.; Kitts, D.D.; Xiao, J.; Ma, H.; Chen, X. Mangiferin: A review of dietary sources, absorption, metabolism, bioavailability, and safety. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 63, 3046–3064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, A.H. Iron Deficiency Anemia in Pregnancy. Obstet. Gynecol. 2021, 138, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.F.; Stepanek, R.; Kothmann, M.; Wilson-Jimenez, M.; McCoy, L.; Aguillon, B.; Salazar, A.; Saade, G.R. Intravenous Iron Compared With Oral Iron Supplementation for the Treatment of Postpartum Anemia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2023, 141, 1052–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitazawa, J.; Kimura, F.; Nakamura, A.; Morimune, A.; Takahashi, A.; Takashima, A.; Amano, T.; Tsuji, S.; Kaku, S.; Kasahara, K.; et al. Endometrial Immunity for Embryo Implantation and Pregnancy Establishment. Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 2020, 250, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pejcic, A.V.; Petrovic, N.Z.; Djordjic, M.D.; Milosavljevic, M.N. Vitamin C Levels in Pregnant Women and the Efficacy of Vitamin C Supplements in Preventing Premature Rupture of Membranes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Balk. Med. J. 2024, 41, 248–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Fabrizio, C.; Giorgione, V.; Khalil, A.; Murdoch, C.E. Antioxidants in Pregnancy: Do We Really Need More Trials? Antioxidants 2022, 11, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prentice, M.; Hickey, J.; Vanderpump, M.; Taylor, P.N.; Lazarus, J.H. Iodine and folate-essential for mothers to be. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020, 8, 9–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radin, M.; Cecchi, I.; Schreiber, K.; Rubini, E.; Roccatello, D.; Cuadrado, M.J.; Sciascia, S. Pregnancy success rate and response to heparins and/or aspirin differ in women with antiphospholipid antibodies according to their Global AntiphosPholipid Syndrome Score. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 2020, 50, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binda, S.; Hill, C.; Johansen, E.; Obis, D.; Pot, B.; Sanders, M.E.; Tremblay, A.; Ouwehand, A.C. Criteria to Qualify Microorganisms as “Probiotic” in Foods and Dietary Supplements. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licata, A.; Zerbo, M.; Como, S.; Cammilleri, M.; Soresi, M.; Montalto, G.; Giannitrapani, L. The Role of Vitamin Deficiency in Liver Disease: To Supplement or Not Supplement? Nutrients 2021, 13, 4014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, A.C.; Miller, A.C.; Miller, M.E.; Xiao, H.; Wu, X. Potential health benefits of edible insects. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 3499–3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oppedisano, F.; Macri, R.; Gliozzi, M.; Musolino, V.; Carresi, C.; Maiuolo, J.; Bosco, F.; Nucera, S.; Caterina Zito, M.; Guarnieri, L.; et al. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Properties of n-3 PUFAs: Their Role in Cardiovascular Protection. Biomedicines 2020, 8, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, E.C.; Pereira, T.M.C.; Peotta, V.A.; Baldo, M.P.; Campos-Toimil, M. Probiotics as Beneficial Dietary Supplements to Prevent and Treat Cardiovascular Diseases: Uncovering Their Impact on Oxidative Stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2019, 2019, 3086270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beluska-Turkan, K.; Korczak, R.; Hartell, B.; Moskal, K.; Maukonen, J.; Alexander, D.E.; Salem, N.; Harkness, L.; Ayad, W.; Szaro, J.; et al. Nutritional Gaps and Supplementation in the First 1000 Days. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, M.; Zhu, Z.; Pi, H.; Chen, J.; Cai, J.; Wu, Y. Mechanistic Insights and Analytical Advances in Food Antioxidants: A Comprehensive Review of Molecular Pathways, Detection Technologies, and Nutritional Applications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowensohn, R.I.; Stadler, D.D.; Naze, C. Current Concepts of Maternal Nutrition. Obstet. Gynecol. Surv. 2016, 71, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla-Gonzalez, F.; Rizzo, S.; Dirks, C.; Bergkamp, W.; Rasker, S.; Aloisi, I. Creation of an Open-Access High-Resolution Tandem Mass Spectral Library of 1000 Food Toxicants. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 23822–23830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Xue, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, S.; Jiang, Y. Nontargeted screening method for detection of illicit adulterants in dietary supplements and herbal medicines using UHPLC-QTOF-MS with fine-tuned Spec2Vec-based spectral similarity and chemical classification filter. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2024, 239, 115877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godevac, D.; Jeremic, J.S.; Cvetkovic, M.; Simic, K.; Sofrenic, I.; Ljujic, J.; Popovic, L.; Gasic, U.; Hoang, Y.N.; Huan, T.; et al. LC-MS-based metabolomics for detecting adulteration in Tribulus terrestris-derived dietary supplements. Food Chem. X 2025, 27, 102476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, L.V.; Mulder, P.P.J.; Zuilhof, H.; Gonzalez, F.P.; Righetti, L. Development of a High-Resolution Tandem Mass Spectral Library for Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids (PASL). Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showell, M.G.; Mackenzie-Proctor, R.; Jordan, V.; Hart, R.J. Antioxidants for female subfertility. Cochrane. Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 8, CD007807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, A.S.; Brahmbhatt, M.N.; Bariya, A.R.; Nayak, J.B.; Singh, V.K. Blockchain technology in food safety and traceability concern to livestock products. Heliyon 2023, 9, e16526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, W.J.; Mangels, A.R.; Fresan, U.; Marsh, K.; Miles, F.L.; Saunders, A.V.; Haddad, E.H.; Heskey, C.E.; Johnston, P.; Larson-Meyer, E.; et al. The Safe and Effective Use of Plant-Based Diets with Guidelines for Health Professionals. Nutrients 2021, 13, 4144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calder, P.C.; Carr, A.C.; Gombart, A.F.; Eggersdorfer, M. Optimal Nutritional Status for a Well-Functioning Immune System Is an Important Factor to Protect against Viral Infections. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carretero-Krug, A.; Montero-Bravo, A.; Morais-Moreno, C.; Puga, A.M.; Samaniego-Vaesken, M.L.; Partearroyo, T.; Varela-Moreiras, G. Nutritional Status of Breastfeeding Mothers and Impact of Diet and Dietary Supplementation: A Narrative Review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Morata, I.; Sobel, M.; Tellez-Plaza, M.; Navas-Acien, A.; Howe, C.G.; Sanchez, T.R. A State-of-the-Science Review on Metal Biomarkers. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2023, 10, 215–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, N.; Balayssac, S.; Danoun, S.; Malet-Martino, M.; Gilard, V. Chemometric Analysis of Low-field 1H NMR Spectra for Unveiling Adulteration of Slimming Dietary Supplements by Pharmaceutical Compounds. Molecules 2020, 25, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Townsend, J.R.; Kirby, T.O.; Sapp, P.A.; Gonzalez, A.M.; Marshall, T.M.; Esposito, R. Nutrient synergy: Definition, evidence, and future directions. Front. Nutr. 2023, 10, 1279925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Sun, M.; Elmaidomy, A.H.; Youssif, K.A.; Zaki, A.M.M.; Hassan Kamal, H.; Sayed, A.M.; Abdelmohsen, U.R. Emerging trends and applications of metabolomics in food science and nutrition. Food Funct. 2023, 14, 9050–9082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Bello-Perez, E.; Elolimy, A.; Abdelatty, A.M. Editorial: Nutrigenomics: Omics of maternal nutrition and foetal programming. Front. Genet. 2024, 15, 1327341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).