Abstract

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are very common in children, especially in the first five years of life, and several viruses, such as the influenza virus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus, and Rhinovirus, are triggers for symptoms that usually affect the upper airways. It has been known that during respiratory viral infections, a condition of oxidative stress (OS) occurs, and many studies have suggested the potential use of antioxidants as complementary components in prophylaxis and/or therapy of respiratory viral infections. Preliminary data have demonstrated that antioxidants may also interfere with the new coronavirus 2’s entry and replication in human cells, and that they have a role in the downregulation of several pathogenetic mechanisms involved in disease severity. Starting from preclinical data, the aim of this narrative review is to evaluate the current evidence about the main antioxidants that are potentially useful for preventing and treating Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in adults and to speculate on their possible use in children by exploring the most relevant issues affecting their use in clinical practice, as well as the associated evidence gaps and research limitations.

1. Introduction

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are very common in children, especially in the first five years of life, and several viruses, such as the influenza virus, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), and Rhinovirus, are triggers for symptoms that usually affect the upper airways. Although being a benign and self-limiting condition, RTIs have a significant medical burden and social cost [1]. It has been known that during respiratory viral infections, a condition of oxidative stress (OS), due to a pro-oxidant–antioxidant imbalance, occurs [2,3] with a reduction in the cellular antioxidant defense system [4]. Two are the main reactive species produced: reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), both of them associated with an increased risk of tissue injury [3]. Increased production of ROS, secondary to respiratory viral infections, has been reported to contribute to airways’ inflammation and tissue damage [4]. Evidence suggests that during respiratory viral infections, the use of antioxidants may help reduce symptoms and facilitate recovery in affected children [5,6], especially if they are administered early before the beginning of a severe pro-inflammatory response in the host [7]. For instance, preclinical studies demonstrated that ascorbic acid is an essential factor for the antiviral immune responses against influenza A virus (H3N2) in the early stages of the infection [8]. At the same time, Huang et al. have shown, in vitro, the suppressive role of melatonin on RSV infection by modulating toll-like receptor (TLR)-3 signaling [9]. Additionally, zinc supplementation would be fundamental in decreasing OS as well as in shortening the duration of symptoms in adults, due to its direct antiviral effect on RSV, dengue virus and coronaviruses [5]. Starting from these assumptions, many researchers have focused their attention on the role that antioxidants could have as complementary components in prophylaxis and/or therapy of respiratory viral infections in adults and children [10]. In fact, antioxidants are able to elicit immune-boosting properties [10] by increasing the number of circulating white cells and reducing ROS level [11]. Furthermore, antioxidant deficiency seems to be correlated to an alteration in T-cells’ activity and a dysregulation of the antibody-mediated immune response, increasing an individual’s susceptibility to infections [12]. Antioxidants can be divided into three groups: those that enhance endogenous antioxidant enzymes, with acceleration of inactivation of free radicals (i.e., N-Acetyl-Cysteine, that reduces the formation of proinflammatory cytokines), non-enzymatic scavengers (dietary antioxidants) and other compounds affecting OS (i.e., using oxygen supplementation and inhaled corticosteroids together) [13]. A large proportion of endogenous antioxidants are encoded by the Nuclear Erythroid Factor 2-Related Factor 2 (Nrf2) pathway; alternatively, exogenous antioxidants are derived from the oral intake of synthetic formulations or a normal diet [14]. Nrf2 is a transcription factor that contributes to the expression of cell-protective genes in response to OS; in particular, it is able to activate several antioxidant genes such as superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) and glutathione (GSH) [15]. High intracellular concentrations of glutathione are required to support several redox reactions [16]. Transcription of Nrf2 is inhibited: under OS, Nrf2 translocates into the nucleus and activates an antioxidant response in the elements battery of genes [17]. Recently, Transient Receptor Potential (TRP) channels have also been studied for their important role in mediating airway tissue injury and inflammation. Among them, Vanilloid-TRP 1 (TRPV1) works as a multisensory receptor for damage signals and plays an important role in the transduction of noxious stimuli and in the maintenance of inflammation [18]. Further, the TRP-ankyrin 1 (TRPA1), expressed by nociceptors, is activated by oxidizing substances and plays a major role in modulating inflammatory pain [19]. Furthermore, a study conducted in animal models demonstrated that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 (ACE2) plays an important role in reducing OS by converting angiotensin II into angiotensin, with a consequent attenuation of inflammatory signaling cascades [20]. Coronavirus 2 is able to bind cell membrane angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE)-2 receptor [21], with the consequent release of the viral load [22]. The reduction in bioavailable ACE2 induces an overexpression of angiotensin II, that is able to activate the Nicotinamide Adenine Dinucleotide PHosphate (NADPH) oxidase pattern, leading to OS and inflammatory response [21,23]. During Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, ROS and RNS are able to regulate the gene expression via Nuclear Factor kappa B (NF-kB); when hyper-expressed, this transcription factor correlates to a progression of severe cases of Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) [3,7]. The Nrf2 is also involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection; in particular, its higher levels are associated with a less severe form of COVID-19 [3]. Antioxidants capable of activating Nrf2 (i.e., dimethyl fumarate, BG12) could be used in the treatment of COVID-19 [24]. BG12 is a molecule able both to activate Nrf2 antioxidant response pathway and to inhibit the proinflammatory cascade. In particular, the efficacy of BG-12 has been demonstrated in clinical experiments involving patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. In fact, the oral use of BG12, if compared to placebo, reduced the proportion of patients who had a clinical and radiological relapse [25]. A recent prospective study including 40 pediatric patients with a confirmed diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection has been conducted by Gumus et al. to determine the relationship between Nrf2 and oxidative balance in this population. The study showed a decreased level of Nrf2 that was correlated to a decreased total antioxidant status, with a contextual increase in total oxidant status (TOS) and OS index (OSI) compared to the control group. The decrease in Nrf2 levels, through an increase in ROS production, might explain the lung tissue damage related to COVID-19; moreover, the more symptomatic the child was, the higher the TOS and OSI values were [26]. In particular, reduced Nrf2 levels were associated with bronchopulmonary inflammation, epithelial damage and mucous cell metaplasia [26]. An antioxidant diet, rich in vegetables (i.e., broccoli), can have a clinical benefit, although in clinical cases of SARS-CoV-2 affected patients who were given broccoli capsules, the clinical benefit was partial [24]. In addition, TRPA1 and TRPV1 play an important role in causing several symptoms of COVID-19 since they are able to mediate airway tissue injury and inflammation [24]. For this reason, another mechanism that could be used to reduce inflammation in SARS-CoV-2 infection is the activation of TRPA1/TRPV1 by dietary antioxidants. For example, TRPV1 localized in the sensory neurons can be desensitized by capsaicin (contained in red peppers); this consequent dose-dependent desensitization may be effective within minutes and for up to a few hours [24]. Aykac et al. [2] showed that serum native thiol and total thiol levels were significantly lower in adults and in children affected by COVID-19 than in controls (p-value = 0.001). Thiols are the main elements of the antioxidant defense system and a good indicator of cellular redox status [2]. In a study involving 160 hospitalized COVID-19 adult patients, Ducastel et al. demonstrated a reduction in thiol plasma concentration correlated with the severity of the disease [27]. These results support the hypothesis that thiol concentration could be used as a predictor of Intensive Care Unit admission (p-value < 0.001) [2,27]. Furthermore, thiol-derived compounds might be used to control the inflammatory response in COVID-19 patients. For instance, Disulfiram [28], a thiol-reacting Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drug to treat alcohol use disorder, is a potent anti-inflammatory agent able to inhibit MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV proteases [2,28]. Finally, elevated interleukin (IL)-6 and calprotectin levels have been associated with an increased mortality among patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection [27]. Moreover, in a recent observational study conducted by Passoss et al., it has been demonstrated that the new coronavirus 2 is able to increase OS biomarkers’ serum levels, such as the glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and the receptor for advanced glycation end products (RAGE), whose increase is directly proportional to the level of neurological damage in patients affected by COVID-19 [23]. The main OS patterns in SARS-CoV-2 infection are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Oxidative stress patterns involved in SARS-CoV-2 infection.

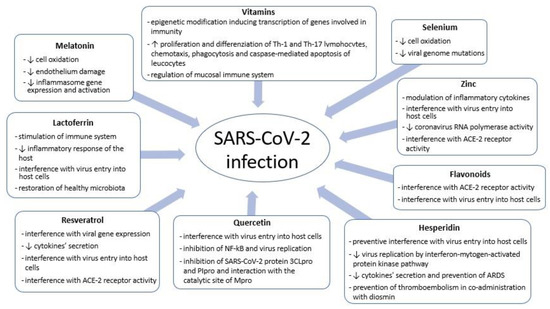

Several agents endowed with antioxidant properties have been assayed or proposed to lower the risk of being affected by SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or to be used as an adjunctive treatment in case of severe COVID-19 [29]. Due to the encouraging preclinical data, we analyzed here the antioxidants on which more studies are available about the mechanisms of interactions with coronavirus 2 (Figure 1) and on which more clinical data are present in literature. These compounds seem to have a relevant role in modulating the immune response during respiratory viral infections (Table A1); starting from evidence on adults, we speculated on their potential use in children.

Figure 1.

SARS-CoV-2 and antioxidants: mechanisms of interaction between coronavirus 2 and host cells.

2. Methods

An electronic literature search was conducted using the Pubmed and Google Scholar databases. The following medical subject heading (MeSH) words were used individually in the search: antioxidants, vitamin A, ascorbic acid, flavonoids, hesperidin, quercetin, lactoferrin, resveratrol, zinc, selenium, melatonin and respiratory tract infection. In the latter case, the subheading “virology” was included. The following MeSH terms were used in combination: respiratory tract infections and antioxidants, respiratory tract infections and flavonoids, respiratory tract infections and quercetin, respiratory tract infections and hesperidin, respiratory tract infections and lactoferrin, respiratory tract infections and melatonin, respiratory tract infections and resveratrol, respiratory tract infections and vitamin A, respiratory tract infections and ascorbic acid, respiratory tract infections and zinc, respiratory tract infections and selenium, COVID-19 and antioxidants, COVID-19 and flavonoids, COVID-19 and quercetin, COVID-19 and hesperidin, COVID-19 and lactoferrin, COVID-19 and melatonin, COVID-19 and resveratrol, COVID-19 and vitamin A, COVID-19 and ascorbic acid, COVID-19 and zinc, and COVID-19 and selenium. The search was limited to studies published within the last decade (2011–2022) and selected based on the following eligibility criteria.

Exclusion criteria:

- Studies without full text available.

- Published studies in local languages, except for English.

- Non-relevant studies about other antioxidants, for the paucity of data in respiratory tract infections (i.e., copper, vitamin E, pentoxifylline).

- Studies about molecules that do not have a primary antioxidant role (i.e., vitamin D).

- Studies about the role of antioxidants in bacterial respiratory tract infections.

- Commentaries, letters and case-reports.

Inclusion criteria:

- In vitro studies about the interaction mechanism between coronavirus 2 and antioxidants.

- Clinical studies evaluating the potential role in preventing and/or treating SARS-CoV-2 infection of the main reviewed antioxidants in adults and children.

The reference lists of the retrieved articles were also consulted.

4. Conclusions and Future Perspectives

The uncontrolled spread of SARS-CoV-2 is a health and social issue that has plagued the world for more than two years. However, today, we can take advantage of prevention and treatment measures that are based on passive and active immunization mechanisms. The administration of multiple doses of messenger-RNA vaccine together with hygienic norms (especially mask use and physical distancing) have determined an epidemiological change and the prevalence of less severe clinical forms of COVID-19, rarely requiring intensive support and treatment. The topic of this narrative review stems from the interest in nutrition and the constant questioning of the role that diet could play in the prevention and treatment of various diseases, including viral respiratory infections. It has been speculated that a dietary supplementation may be of high importance in the current COVID-19 pandemic, so several studies on this topic have been initiated [70]. Nevertheless, this issue is still highly controversial, particularly in relation to SARS-CoV-2 infection in the pediatric age group. We found that antioxidants might have a protective and therapeutic role against COVID-19 and, starting from clinical data obtained in adults (Table 2), this review provides an opportunity to consider and speculate on whether new trials in children should be conducted, allowing for stronger scientific evidence than those currently available. The benefit that could be obtained would be significant, since most of these substances are included in a free non-selective diet and are easily available. However, more studies are necessary to evaluate the real safety and efficacy of these compounds; an additional issue to be investigated concerns bioavailability, and therefore, data comparing the effects obtained according to different routes of administration are also necessary. In conclusion, although COVID-19 in children is generally a mild disease, the availability of compounds such as antioxidants which could be able to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection and/or reduce the length of respiratory symptoms could presumably have significant epidemiological effects, reducing both medical burden and social cost.

Table 2.

Potential clinical use of antioxidants in prophylaxis and/or treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection in adults.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.F. and M.G.; methodology, G.F.; writing—original draft preparation, V.N. and C.M.; writing—review and editing, V.N. and C.M.; supervision, M.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Influence of antioxidants on the immune system.

Table A1.

Influence of antioxidants on the immune system.

| Type of Antioxidant | Innate Immunity | Adaptive immunity |

|---|---|---|

| Flavonoids | Inhibition of ROS-generating enzymes and chelation of transition metal ions, which can catalyze ROS production [30] | Increase in lymphocyte proliferation and regulation of IFN-γ secretion [38]; reduction in IL-2 and IFN-γ release [45] |

| Quercetin | Inhibition of NF-κB activation; increase in neutrophil chemotaxis, NK-cells’ activity and macrophages’ phagocytosis [38] | Increase in lymphocyte proliferation and regulation of IFN-γ secretion [38] |

| Hesperidin | Reduction in TNF-α and IL-6 release [45] | Reduction in IL-2 and IFN-γ release [45] |

| Lactoferrin | Increase in neutrophils’ aggregation and NK-cells’ activity [48,49] Reduction in TNF-α and IL-6 serum levels [50] | Promotion of T and B-lymphocytes differentiation [49] |

| Melatonin | Inhibition of NF-κB activation [55] Suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome [55,56] | Increase in T-cells’ differentiation [56] |

| Zinc | Increase in neutrophils’ aggregation, macrophages’ phagocytosis and NK-cells’ activity [61] | Increase in T-cells’ differentiation, especially Th-1 cells [61,63] |

| Selenium | Increase in macrophages’ phagocytosis and NK-cells’ activity [61] Inhibition of NF-κB activation [69] Reduction in TNF-α and IL-6 serum levels [69] | Promotion of T-cells’ differentiation [61] Regulation of IFN-γ secretion [61] |

| Vitamin C | Increase in macrophages’ and neutrophils’activity [73,74,75,76] Promotion of NK-cells’ activity [73] Inhibition of NF-κB activation [73] | Promotion of T-cell differentiation, especially Th-1 and Th-17 cells [73,74,75,76] Promotion of antibody production [73] |

| Vitamin A | Promotion of dendritic cells’activity [84] Increase in macrophages’, NK-cells’ and neutrophils’activity [84] | Promotion of T-reg cell differentiation [82] Increase in IgAs production [82] |

| Resveratrol | Suppression of NLRP3 inflammasome [92] Inhibition of NF-κB activation [90,93] Reduction in IL-6 release [93] | Promotion of T-cell differentiation [92] |

ROS: Reactive Oxygen Species; IFN-γ: Interferon-γ; TNF-α: Tumor Necrosis Factor-α; IL: Interleukin; NF-κB: Nuclear Factor-kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; NK: Natural-killer; NLRP3: NLR family pyrin domain containing-3; Th: T-helper cells; T-reg: regulatory T-cells; IgAs: immunoglobulins A.

References

- Chiappini, E.; Santamaria, F.; Marseglia, G.L.; Marchisio, P.; Galli, L.; Cutrera, R.; de Martino, M.; Antonini, S.; Becherucci, P.; Biasci, P.; et al. Prevention of recurrent respiratory infections. Inter-society Consensus. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2021, 47, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aykac, K.; Ozsurekci, Y.; Yayla, B.C.C.; Gurlevik, S.L.; Oygar, P.D.; Bolu, N.B.; Tasar, M.A.; Erdinc, F.S.; Ertem, G.T.; Neselioglu, S.; et al. Oxidant and antioxidant balance in patients with COVID-19. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2021, 56, 2803–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciano-Machuca, O.; Villegas-Rivera, G.; López-Pérez, I.; Macías-Barragán, J.; Sifuentes-Franco, S. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Following SARS-CoV-2 Infection: Role of Oxidative Stress. Front. Immunol. 2021, 19, 723654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khomich, O.A.; Kochetkov, S.N.; Bartosch, B.; Ivanov, A.V. Redox Biology of Respiratory Viral Infections. Viruses 2018, 10, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecora, F.; Persico, F.; Argentiero, A.; Neglia, C.; Esposito, S. The Role of Micronutrients in Support of the Immune Response against Viral Infections. Nutrients 2020, 12, 3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayawardena, R.; Sooriyaarachchi, P.; Chourdakis, M.; Jeewandara, C.; Ranasinghe, P. Enhancing immunity in viral infections, with special emphasis on COVID-19: A review. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. 2020, 14, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keles, E.S. Mild SARS-CoV-2 infections in children might be based on evolutionary biology and linked with host reactive oxidative stress and antioxidant capabilities. New Microbes New Infect. 2020, 36, 100723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Bae, S.; Choi, J.; Lim, S.Y.; Lee, N.; Myung Kong, J.; Hwang, Y.; Kang, J.S.; Lee, W.J. Vitamin C is an essential factor on the anti-viral immune responses through the production of interferon-α/β at the initial stage of influenza A virus (H3N2) infection. Immune Netw. 2013, 13, 70–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.H.; Cao, X.J.; Liu, W.; Shi, X.Y.; Wei, W. Inhibitory effect of melatonin on lung oxidative stress induced by respiratory syncytial virus infection in mice. J. Pineal Res. 2010, 48, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, S.; Das, J.K.; Ismail, T.; Wahid, M.; Saeed, W.; Bhutta, Z.A. Nutritional perspectives for the prevention and mitigation of COVID-19. Nutr. Rev. 2021, 79, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Stadio, A.; Della Volpe, A.; Korsch, F.M.; De Lucia, A.; Ralli, M.; Martines, F.; Ricci, G. Difensil Immuno Reduces Recurrence and Severity of Tonsillitis in Children: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Junaid, K.; Ejaz, H.; Abdalla, A.E.; Abosalif, K.O.A.; Ullah, M.I.; Yasmeen Younas, S.; Hamam, S.S.M.; Rehman, A. Effective Immune Functions of Micronutrients against SARS-CoV-2. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Victoni, T.; Barreto, E.; Lagente, V.; Carvalho, V.F. Oxidative Imbalance as a Crucial Factor in Inflammatory Lung Diseases: Could Antioxidant Treatment Constitute a New Therapeutic Strategy? Oxid Med. Cell. Longev. 2021, 2021, 6646923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.F.; Harris, R.; Stout-Delgado, H.W. Targeted Antioxidants as Therapeutics for Treatment of Pneumonia in the Elderly. Transl. Res. 2020, 220, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.; Jang, J.; Park, S.M.; Yang, S.R. An Update on the Role of Nrf2 in Respiratory Disease: Molecular Mechanisms and Therapeutic Approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, S.P.; Bhatnagar, A. Role of Thiols in Oxidative Stress. Curr. Opin. Toxicol. 2018, 7, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, S.M.U.; Luo, L.; Namani, A.; Wang, X.J.; Tang, X. Nrf2 Signaling Pathway: Pivotal Roles in Inflammation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta BBA-Mol. Basis Dis. 2017, 1863, 585–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liviero, F.; Campisi, M.; Mason, P.; Pavanello, S. Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid Subtype 1: Potential Role in Infection, Susceptibility, Symptoms and Treatment of COVID-19. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 753819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zhang, H.; Wei, L.; Liu, Q.; Xie, M.; Weng, J.; Wang, X.; Chung, K.F.; Adcock, I.M.; Chen, Y.; et al. Role of TRPA1/TRPV1 in acute ozone exposure induced murine model of airway inflammation and bronchial hyperresponsiveness. J. Thorac. Dis. 2022, 14, 2698–2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, R.A.P.; Chu, Y.; Miller, J.D.; Mitchell, I.J.; Penninger, J.M.; Faraci, F.M.; Heistad, D.D. Impact of ACE2 Deficiency and Oxidative Stress on Cerebrovascular Function with Aging. Stroke 2012, 43, 3358–3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, M.T.; Wu, C.C.; Wu, S.F.V.; Lee, M.C.; Hu, W.C.; Tsai, K.W.; Yang, C.H.; Lu, C.L.; Chiu, S.K.; Lu, K.C. Resveratrol as an Adjunctive Therapy for Excessive Oxidative Stress in Aging COVID-19 Patients. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Ligt, M.; Hesselink, M.K.C.; Jorgensena, J.; Hoebersb, N.; Blaak, E.E.; Goossens, G.H. Resveratrol supplementation reduces ACE2 expression in human adipose tissue. Adipocyte 2021, 10, 408–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passos, F.R.S.; Heimfarth, L.; Monteiro, B.S.; Corrêa, C.B.; Rodrigues de Moura, T.; De Souza Araújo, A.A.; Martins-Filho, P.R.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J.; De Souza Siqueira Quintans, J. Oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in patients with COVID-19: Potential role of RAGE, HMGB1, GFAP and COX-2 in disease severity. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2022, 104, 108502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bousquet, J.; Czarlewskic, W.; Zuberbiera, T.; Mullole, J.; Blainf, H.; Cristolg, J.P.; De La Torre, R.; Lozano, N.P.; Le Moing, V.; Bedbrook, A.; et al. Potential Interplay between Nrf2, TRPA1, and TRPV1 in Nutrients for the Control of COVID-19. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 2021, 182, 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gold, R.; Kappos, L.; Arnold, D.L.; Bar-Or, A.; Giovannoni, G.; Selmaj, K.; Tornatore, C.; Sweetser, M.T.; Yang, M.; Sheikh, S.I.; et al. DEFINE Study Investigators. Placebo-Controlled Phase 3 Study of Oral BG-12 for Relapsing Multiple Sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1098–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, H.; Erat, T.; Öztürk, I.; Demir, A.; Koyuncu, I. Oxidative stress and decreased Nrf2 level in pediatric patients with COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2022, 94, 2259–2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducastel, M.; Chenevier-Gobeaux, C.; Ballaa, Y.; Meritet, J.F.; Brack, M.; Chapuis, N.; Pene, F.; Carlier, N.; Szwebel, T.A.; Roche, N.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Inflammatory Biomarkers for the Prediction of Severity and ICU Admission in Unselected Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.H.; Moses, D.C.; Hsieh, C.H.; Cheng, S.C.; Chen, Y.H.; Sun, C.Y.; Chou, C.Y. Disulfiram can inhibit MERS and SARS coronavirus papain-like proteases via different modes. Antivir. Res. 2018, 150, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Flora, S.; Balansky, R.; La Maestra, S. Antioxidants and COVID-19. J. Prev. Med. Hyg. 2021, 62 (Suppl. 3), E34–E45. [Google Scholar]

- Mierziak, J.; Kostyn, K.; Kulma, A. Flavonoids as important molecules of plant interactions with the environment. Molecules 2014, 19, 16240–16265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J.; Song, J.H.; Park, K.S.; Kwon, D.H. Inhibitory effects of quercetin 3-rhamnoside on influenza A virus replication. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2009, 37, 329–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Li, R.; Li, X.; He, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, S.; Yang, J. Quercetin as an Antiviral Agent Inhibits Influenza A Virus (IAV) Entry. Viruses 2015, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Margolin, L.; Luchins, J.; Margolin, D.; Margolin, M.; Lefkowitz, S. 20-Week Study of Clinical Outcomes of Over-the-Counter COVID-19 Prophylaxis and Treatment. J. Evid. Based Integr. Med. 2021, 26, 2515690X211026193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Magro, G. COVID-19: Review on latest available drugs and therapies against SARS-CoV-2. Coagulation and inflammation cross-talking. Virus Res. 2020, 286, 198070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaul, R.; Paul, P.; Kumar, S.; Büsselberg, D.; Dwivedi, V.D.; Chaari, A. Promising Antiviral Activities of Natural Flavonoids against SARS-CoV-2 Targets: Systematic Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 11069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shawan, M.M.A.K.; Halder, S.K.; Hasan, M.A. Luteolin and abyssinone II as potential inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2: An in silico molecular modeling approach in battling the COVID-19 outbreak. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2021, 45, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anaya-Loyola, M.A.; García-Marín, G.; García-Gutiérrez, D.G.; Castaño-Tostado, E.; Reynoso-Camacho, R.; López-Ramos, J.E.; Enciso-Moreno, J.A.; Pérez-Ramírez, I.F. A mango (Mangifera indica L.) juice by-product reduces gastrointestinal and upper respiratory tract infection symptoms in children. Food. Res. Int. 2020, 136, 109492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Z.; Yang, Z.; Wang, J.; Xu, Y.; Tan, R.X.; Li, E. Houttuynia cordata blocks HSV infection through inhibition of NF-κB activation. Antiviral. Res. 2011, 92, 341–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, D.S.; Azhar, I.E.; Madani, T.A.; Ntoumi, F.; Kock, R.; Dar, O.; Ippolito, G.; Mchugh, T.D.; Memish, Z.A.; Drosten, C.; et al. The continuing 2019-nCoV epidemic threat of novel coronaviruses to global health-The latest 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak in Wuhan, China. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 91, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.Y.; Yuk, H.J.; Ryu, H.W.; Lim, S.H.; Kim, K.S.; Park, K.H.; Ryu, Y.B.; Lee, W.S. Evaluation of polyphenols from Broussonetia papyrifera as coronavirus protease inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2017, 32, 504–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.H.; Wu, K.L.; Zhang, X.; Deng, S.Q.; Peng, B. In silico screening of Chinese herbal medicines with the potential to directly inhibit 2019 novel coronavirus. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 18, 152–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marín-Corral, J.; Rodríguez-Morató, J.; Gomez-Gomez, A.; Pascual-Guardia, S.; Muñoz-Bermúdez, R.; Salazar-Degracia, A.; Pérez-Terán, P.; Restrepo, M.I.; Khymenets, O.; Haro, N.; et al. Metabolic Signatures Associated with Severity in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shohan, M.; Nashibi, R.; Mahmoudian-Sani, M.R.; Abolnezhadian, F.; Ghafourian, M.; Alavi, S.M.; Sharhani, A.; Khodadadi, A. The therapeutic efficacy of quercetin in combination with antiviral drugs in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2022, 914, 174615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pierro, F.; Iqtadar, S.; Khan, A.; Ullah Mumtaz, S.; Masud Chaudhry, M.; Bertuccioli, A.; Derosa, G.; Maffioli, P.; Togni, S.; Riva, A.; et al. Potential Clinical Benefits of Quercetin in the Early Stage of COVID-19: Results of a Second, Pilot, Randomized, Controlled and Open-Label Clinical Trial. Int. J. Gen. Med. 2021, 14, 2807–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haggag, Y.A.; El-Ashmawy, N.E.; Okasha, K.M. Is hesperidin essential for prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19 Infection? Med. Hypotheses 2020, 144, 109957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buscemi, S.; Rosafio, G.; Arcoleo, G.; Mattina, A.; Canino, B.; Montana, M.; Verga, S.; Rini, G. Effects of red orange juice intake on endothelial function and inflammatory markers in adult subjects with increased cardiovascular risk. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 95, 1089–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jose, R.J.; Manuel, A. COVID-19 cytokine storm: The interplay between inflammation and coagulation. Lancet Respir. Med. 2020, 8, e46–e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Yang, N.; Deng, J.; Liu, K.; Yang, P.; Zhang, G.; Jiang, C. Inhibition of SARS pseudovirus cell entry by lactoferrin binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e23710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, G.; Kochergina, I.; Albors, A.; Diaz, E.; Oroval, M.; Hueso, G.; Serrano, J.M. Liposomal Lactoferrin as Potential Preventative and Cure for COVID-19. Int. J. Res. Health Sci. 2020, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, R.; Ng, T.B.; Sun, W.Z. Lactoferrin as potential preventative and adjunct treatment for COVID-19. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2020, 56, 106118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campione, E.; Cosio, T.; Rosa, L.; Lanna, C.; Di Girolamo, S.; Gaziano, R.; Valenti, P.; Bianchi, L. Lactoferrin as Protective Natural Barrier of Respiratory and Intestinal Mucosa against Coronavirus Infection and Inflammation. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Root-Bernstein, R. Age and Location in Severity of COVID-19 Pathology: Do Lactoferrin and Pneumococcal Vaccination Explain Low Infant Mortality and Regional Differences? Bioessays 2020, 42, e2000076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campione, E.; Lanna, C.; Cosio, T.; Rosa, L.; Conte, M.P.; Iacovelli, F.; Romeo, A.; Falconi, M.; Del Vecchio, C.; Franchin, E.; et al. Lactoferrin as potential supplementary nutraceutical agent in COVID-19 patients: In vitro and in vivo preliminary evidences. bioRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algahtani, F.D.; Elabbasy, M.T.; Samak, M.A.; Adeboye, A.A.; Yusuf, R.A.; Ghoniem, M.E. The Prospect of Lactoferrin Use as Adjunctive Agent in Management of SARS-CoV-2 Patients: A Randomized Pilot Study. Medicina 2021, 57, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Carballo, A.; Jerez-Calero, A.E.; Muñoz-Hoyos, A. Possible Protective Role of Melatonin in Pediatric Infectious Diseases and Neurodevelopmental Pathologies. J. Child. Sci. 2020, 10, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shneider, A.; Kudriavtsev, A.; Vakhrusheva, A. Can melatonin reduce the severity of COVID-19 pandemic? Int. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 39, 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köken Yayici, Ö.; Gültutan, P.; Güngören, M.S.; Bayhan, G.I.; Yılmaz, D.; Gürkaş, E.; Özyürek, H.; Çitak Kurt, A.N. Impact of COVID-19 on serum melatonin levels and sleep parameters in children. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 1640–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnoosh, G.; Akbariqomi, M.; Badri, T.; Bagheri, M.; Izadi, M.; Saeedi-Boroujeni, A.; Rezaie, E.; Gouvarchin Ghaleh, H.E.; Aghamollaei, H.; Fasihi-Ramandi, M.; et al. Efficacy of a Low Dose of Melatonin as an Adjunctive Therapy in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Randomized, Double-blind Clinical Trial. Arch. Med. Res. 2022, 53, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, Z.T.; Al Atrakji, M.Q.Y.M.A.; Mehuaiden, A.K. The Effect of Melatonin on Thrombosis, Sepsis and Mortality Rate in COVID-19 Patients. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022, 114, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García García, I.; Rodriguez-Rubio, M.; Rodríguez Mariblanca, A.; Martínez de Soto, L.; Díaz García, L.; Monserrat Villatoro, J.; Queiruga Parada, J.; Seco Meseguer, E.; Rosales, M.J.; González, J.; et al. A randomized multicenter clinical trial to evaluate the efficacy of melatonin in the prophylaxis of SARS-CoV-2 infection in high-risk contacts (MeCOVID Trial): A structured summary of a study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dharmalingam, K.; Birdi, A.; Tomo, S.; Sreenivasulu, K.; Charan, J.; Yadav, D.; Purohit, P.; Sharma, P. Trace Elements as Immunoregulators in SARS-CoV-2 and Other Viral Infections. Ind. J. Clin. Biochem. 2021, 36, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez-Estevez, N.S.; Alvarez-Guevara, A.N.; Rodriguez-Martinez, C.E. Effects of zinc supplementation in the prevention of respiratory tract infections and diarrheal disease in Colombian children: A 12-month randomised controlled trial. Allergol Immunopathol. 2016, 44, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemilä, H.; Chalker, E. Vitamin C for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Database Syst.Rev. 2013, 31, CD000980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, J.; Villada, O.A.; Rojas, M.L.; Montoya, L.; Díaz, A.; Vargas, C.; Chica, J.; Herrera, A.M. Efecto del zinc aminoquelado y el sulfato de zinc en la incidencia de la infección respiratoria y la diarrea en niños preescolares de centros infantiles. Biomédica 2014, 34, 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, H.O. Therapeutic supplementation with zinc in the management of COVID-19-related diarrhea and ageusia/dysgeusia:mechanisms and clues for a personalized dosage regimen. Nutr. Rev. 2022, 80, 1086–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Elsalam, S.; Soliman, S.; Esmail, E.S.; Khalaf, M.; Mostafa, E.F.; Medhat, M.A.; Ahmed, O.A.; Abd El Ghafar, M.S.; Alboraie, M.; Hassany, S.M. Do Zinc Supplements Enhance the Clinical Efficacy of Hydroxychloroquine? A Randomized, Multicenter Trial. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 3642–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elalfy, H.; Besheer, T.; El-Mesery, A.; El-Gilany, A.H.; Abdel-Aziz Soliman, M.; Alhawarey, A.; Alegezy, M.; Elhadidy, T.; Hewidy, A.A.; Zaghloul, H.; et al. Effect of a combination of nitazoxanide, ribavirin, and ivermectin plus zinc supplement (MANS.NRIZ study) on the clearance of mild COVID-19. J. Med. Virol. 2021, 93, 3176–3183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelmaksoud, A.A.; Ghweil, A.A.; Hassan, M.H.; Rashad, A.; Khodeary, A.; Aref, Z.F.; Abdelrhman Sayed, M.A.; Elsamman, M.K.; Bazeed, S.E.S. Olfactory Disturbances as Presenting Manifestation Among Egyptian Patients with COVID-19: Possible Role of Zinc. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2021, 199, 4101–4108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, S.S.; Huang, Y.; Acuna, L.; Laverde, E.; Trujillo, D.; Barbieri, M.A.; Tamargo, J.; Campa, A.; Baum, M.K. Role of Selenium in Viral Infections with a Major Focus on SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 23, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heller, R.A.; Sun, Q.; Hackler, J.; Seelig, J.; Seibert, L.; Cherkezov, A.; Minich, W.B.; Seemann, P.; Diegmann, J.; Pilz, M.; et al. Prediction of survival odds in COVID-19 by zinc, age and selenoprotein P as composite biomarker. Redox Biol. 2021, 38, 101764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Nagabhushanam, K.; Medicie, M.D.S.G.; Mundkur, L. An exploratory study of selenium status in healthy individuals and in patients with COVID-19 in a south Indian population: The case for adequate selenium status. Nutrition 2021, 82, 111053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoodpoor, A.; Hamishehkar, H.; Shadvar, K.; Ostadi, Z.; Sanaie, S.; Saghaleini, S.H.; Nader, N.D. The Effect of Intravenous Selenium on Oxidative Stress in Critically III Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Immunol. Invest. 2019, 48, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerullo, G.; Negro, M.; Parimbelli, M.; Pecoraro, M.; Perna, S.; Liguori, G.; Rondanelli, M.; Cena, H.; D’Antona, G. The Long History of Vitamin C: From Prevention of the Common Cold to Potential Aid in the Treatment of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 574029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemilä, H. Vitamin C and Infections. Nutrients 2017, 9, 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carr, A.C.; Maggini, S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients 2017, 9, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozonet, S.M.; Carr, A.C.; Pullar, J.M.; Vissers, M.C. Enhanced human neutrophil vitamin C status, chemotaxis and oxidant generation following dietary supplementation with vitamin C-rich SunGold kiwifruit. Nutrients 2015, 7, 2574–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, E.; Quidel, S.; Bravo-Soto, G.; Ortigoza, Á. Does vitamin C prevent the common cold? Medwave 2018, 18, e7235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, L.; Zhao, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Y.; Tseng, Y.; Bu, H. Extra Dose of Vitamin C Based on a Daily Supplementation Shortens the Common Cold: A Meta-Analysis of 9 Randomized Controlled Trials. Biomed Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 1837634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majidi, N.; Rabbani, F.; Gholami, S.; Gholamalizadeh, M.; BourBour, F.; Rastgoo, S.; Hajipour, A.; Shadnoosh, M.; Akbari, M.E.; Bahar, B. The Effect of Vitamin C on Pathological Parameters and Survival Duration of Critically Ill Coronavirus Disease 2019 Patients: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 717816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sulaiman, K.; Aljuhani, O.; Saleh, K.B.; Badreldin, H.A.; Al Harthi, A.; Alenazi, M.; Alharbi, A.; Algarni, R.; Al Harbi, S.; Alhammad, A.M. Ascorbic acid as an adjunctive therapy in critically ill patients with COVID-19: A propensity score matched study. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fowler, A.A.; Syed, A.A.; Knowlson, S.; Sculthorpe, R.; Farthing, D.; DeWilde, C.; Farthing, C.A.; Larus, T.L.; Martin, E.; Brophy, D.F.; et al. Phase I safety trial of intravenous ascorbic acid in patients with severe sepsis. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Rao, X.; Li, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, F.; Guo, G.; Luo, G.; Meng, Z.; De Backer, D.; Xiang, H. Pilot trial of high-dose vitamin C in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Ann. Intensive Care 2021, 11, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, S.; Patel, D.; Bittel, B.; Wolski, K.; Wang, Q.; Kumar, A.; Il’Giovine, Z.J.; Mehra, R.; McWilliams, C.; Nissen, S.E. Effect of High-Dose Zinc and Ascorbic Acid Supplementation vs Usual Care on Symptom Length and Reduction Among Ambulatory Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection: The COVID A to Z Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021, 4, e210369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chattha, K.S.; Kandasamy, S.; Vlasova, A.N.; Saif, L.J. Vitamin A deficiency impairs adaptive B and T cell responses to a prototype monovalent attenuated human rotavirus vaccine and virulent human rotavirus challenge in a gnotobiotic piglet model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e82966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jee, J.; Hoet, A.E.; Azevedo, M.P.; Vlasova, A.N.; Loerch, S.C.; Pickworth, C.L.; Hanson, J.; Saif, L.J. Effects of dietary vitamin A content on antibody responses of feedlot calves inoculated intramuscularly with an inactivated bovine coronavirus vaccine. Am. J. Vet. Res. 2013, 74, 1353–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, J.L.; Kelly, S.M.; Guerra-Maupome, M.; Winkley, E.; Henningson, J.; Narasimhan, B.; Sacco, R.E. Vitamin A deficiency impairs the immune response to intranasal vaccination and RSV infection in neonatal calves. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotto, I.; Mimouni, M.; Gdalevich, M.; Mimouni, D. Vitamin A supplementation and childhood morbidity from diarrhea and respiratory infections: A meta-analysis. J. Pediatr. 2003, 142, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amaral, C.T.; Pontes, N.N.; Maciel, B.L.L.; Bezerra, H.S.M.; Triesta, A.N.A.B.; Jeronimo, S.M.B.; McGowan, S.E.; Dantas, V.M. Vitamin A deficiency alters airway resistance in children with acute upper respiratory infection. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 2013, 48, 481–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.S.; Kim, I.K.; Park, Y.J.; Kim, Y.S.; Kim, Y.J.; Chang, W.S.; Lee, Y.S.; Kweon, M.N.; Chung, Y.; Kang, C.Y. Conversion of Th2 memory cells into Foxp3+ regulatory T cells suppressing Th2-mediated allergic asthma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 8742–8747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teran, R.; Mitre, E.; Vaca, M.; Erazo, S.; Oviedo, G.; Hübner, M.P.; Chico, M.E.; Mattapallil, J.J.; Bickle, Q.; Rodrigues, L.C.; et al. Immune system development during early childhood in tropical Latin America: Evidence for the age-dependent down regulation of the innate immune response. Clin. Immunol. 2011, 138, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midha, I.K.; Kumar, N.; Kumar, A.; Madan, T. Mega doses of retinol: A possible immunomodulation in Covid-19 illness in resource-limited settings. Rev. Med. Virol. 2021, 31, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varricchio, A.M.; Capasso, M.; Della Volpe, A.; Malafronte, L.; Mansi, N.; Varricchio, A.; Ciprandi, G. Resveratrol plus carboxymethyl-β-glucan in children with recurrent respiratory infections: A preliminary and real-life experience. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Wei, J.; Huang, T.; Lei, L.; Shen, C.; Lai, J.; Yang, M.; Liu, L.; Yang, Y.; Liu, G.; et al. Resveratrol inhibits the replication of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in cultured Vero cells. Phytother. Res. 2021, 35, 1127–1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, G.A.; Sacco, O.; Capizzi, A.; Mastromarino, P. Can Resveratrol-Inhaled Formulations Be Considered Potential Adjunct Treatments for COVID-19? Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 670955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassarre, M.E.; Di Mauro, A.; Labellarte, G.; Pignatelli, M.; Fanelli, M.; Schiavi, E.; Mastromarino, P.; Capozza, M.; Panza, R.; Laforgia, N. Resveratrol plus carboxymethyl-β-glucan in infants with common cold: A randomized double-blind trial. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).