Abstract

Background/Objectives: This systematic review presents how neural and emotional networks are integrated into EEG-based emotion recognition, bridging the gap between cognitive neuroscience and practical applications. Methods: Following PRISMA, 64 studies were reviewed that outlined the latest feature extraction and classification developments using deep learning models such as CNNs and RNNs. Results: Indeed, the findings showed that the multimodal approaches were practical, especially the combinations involving EEG with physiological signals, thus improving the accuracy of classification, even surpassing 90% in some studies. Key signal processing techniques used during this process include spectral features, connectivity analysis, and frontal asymmetry detection, which helped enhance the performance of recognition. Despite these advances, challenges remain more significant in real-time EEG processing, where a trade-off between accuracy and computational efficiency limits practical implementation. High computational cost is prohibitive to the use of deep learning models in real-world applications, therefore indicating a need for the development and application of optimization techniques. Aside from this, the significant obstacles are inconsistency in labeling emotions, variation in experimental protocols, and the use of non-standardized datasets regarding the generalizability of EEG-based emotion recognition systems. Discussion: These challenges include developing adaptive, real-time processing algorithms, integrating EEG with other inputs like facial expressions and physiological sensors, and a need for standardized protocols for emotion elicitation and classification. Further, related ethical issues with respect to privacy, data security, and machine learning model biases need to be much more proclaimed to responsibly apply research on emotions to areas such as healthcare, human–computer interaction, and marketing. Conclusions: This review provides critical insight into and suggestions for further development in the field of EEG-based emotion recognition toward more robust, scalable, and ethical applications by consolidating current methodologies and identifying their key limitations.

1. Introduction

Emotions are arguably the most important aspect of human life, closely linked to cognition and the quality and richness of human experience [1,2,3]. The rapid development of effective computing technology has resulted in systems being developed for several domains to measure, understand, and respond to human needs [4,5,6]. One of the principal subfields in affective computing is based on non-invasive EEG [7,8]. This subdomain will be reviewed and discussed according to human emotions, EEG channels and bands, applications, databases, and machine learning algorithms [9,10].

Currently, advances in computer technology have allowed the creation of systems that are prepared to interpret, recognize, and express emotions, allowing the development of medical systems that diagnose and follow up on different emotional states, virtual reality applications capable of identifying the user’s emotional state to adapt the environment or change the users’ VR experience, or marketing applications capable of capturing the user’s reactions to different company products [11,12,13,14,15]. All these examples fall within the affective computing rubric, a multidisciplinary area that extends to computer science, psychology, and social expression science, whose purpose is to understand, measure, and respond to human emotions [16,17,18,19,20].

In artificial intelligence, recognizing bioelectric signals, especially electroencephalogram (EEG) signals, can represent the users’ emotional patterns. This is known as EEG-based emotion recognition [21,22,23]. The original intention of emotion recognition was to help people who could not perceive other people’s emotions well, including patients with autism, agnosia, and other neuropsychiatric diseases. However, recent research has mainly focused on moving towards real-world applications helping machines recognize people’s emotional words [24,25,26]. However, the advancement of signal processing techniques and affective neuroscience has not been fully utilized in this decade-long research. This review aims to integrate and summarize the recent progress of emotion recognition and provide some recommendations and current challenges for researchers interested in this topic [27,28].

This research aims to merge different complex knowledge bases, from affective neuroscience to signal processing. Furthermore, we hope the separation between researchers from various research areas will gradually decrease after summarizing these vast and diverse studies. These embedded communities share the same EEG signal but with different expectations and could benefit from each other’s designs. Our article will describe the purpose and methods of each work, and we will summarize the significant conclusions of each study. This article will compare the discrepancies between the considerable findings of different tasks and identify future challenges for the research community. Specifically, we will carefully discuss the emotional feedback loops for integrating future real-world applications.

2. Literature Review

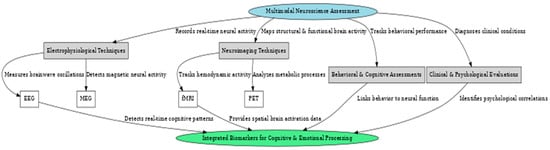

2.1. Neural Networks in Cognitive Neuroscience

First should be an introduction to the problem area. A more detailed description of neural networks might help understand the two subfields. Ideally, the description should include the current state of the art, frontiers of research, and a bit of a pragmatic tone to be educational. Then, more specialized information for each subfield should follow [29,30,31]. For the last part, bridge phrases should draw the two subfields together and point to the limitations of the current practice in both. The conclusion should end the section after a couple of sentences summarizing what has been said. The study and modeling of cognitive processes through a neurobiological approach are as old and diverse as the field of cognitive neuroscience itself. Cognitive neuroscience has grown around integrating a pattern of specialized but segregated neural networks that process different categories of sensory input and an abstract model of higher cognitive activity [32,33,34]. Moreover, while asymmetry in brain function was often beyond direct observation in external behavior or internal experience, the same dichotomy eventually appeared in psychological models of emotional and cognitive processes, notably with the identification in the last decades of a mentalizing network and a central executive large-scale network model. Equally significant, albeit a less researched aspect, a growing body of evidence has suggested that the core cognitive control role of the central executive network also extends to the processing of emotionally salient information by recruiting the regions in emotional regulation and in recruiting them for the top-down deployment of selective attention on emotional stimuli, particularly when resisting interfering emotional activity [35,36].

2.1.1. Fundamentals of Neural Networks

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are computational models inspired by the structure and function of biological neural networks in the human brain. ANNs consist of interconnected layers of artificial neurons that process and transmit information through weighted connections. Typically, ANNs have an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. The input layer receives raw data, the hidden layers transform this data through weighted computations and activation functions, and the output layer provides the final processed information, which can represent various outcomes, such as classification, regression, or decision-making tasks [37,38]. Each neuron in an ANN applies a mathematical function to its inputs, typically a weighted sum followed by an activation function. Standard activation functions include sigmoid, ReLU (Rectified Linear Unit), and tanh, which introduce non-linearity into the model, allowing it to learn complex patterns [39]. Training an ANN involves adjusting the weights of connections using optimization techniques such as gradient descent to minimize the difference between predicted and actual outputs. ANNs have broad applications, including pattern recognition, natural language processing, and speech recognition. In speech processing, ANNs can identify phonetic patterns even in noisy environments, enabling robust voice recognition systems [40,41]. One of the most used architectures is the multilayer perception (MLP), which consists of multiple layers of neurons and uses backpropagation for training [42]. Unlike biological neural networks, where neurons are specialized for different functions, such as sensory or motor neurons, the neurons in an ANN are generalized computational units. The output layer can take various forms depending on the application, ranging from a classification label to a numerical prediction [43]. Furthermore, real-time processing applications like robotics and autonomous systems can integrate ANNs with sensor input to enable adaptive decision-making based on incoming data [44,45].

2.1.2. Applications in Cognitive Neuroscience

Direct observation of neural activities evoked by emotional stimuli and scenarios is often needed to understand the neural dynamics of emotion. Therefore, the practical and precise technique for measuring brain emotional responses becomes indispensable. With high temporal resolution, simultaneously recorded electrophysiological signals, such as the electroencephalogram and magnetoencephalogram, contain significant information about the neural processes at a millisecond level during different emotional states, which modern machine learning models capture as features to recognize emotional states [46]. Generally, in cognitive neuroscience, EEG routines have a higher temporal resolution when subjects watch specific video clips or pictures that elicit explicit emotions [47]. Besides, EEG is widely applied to record brain response signals during face-to-face social-emotional communication [48]. With a more natural experimental setup that does not pressure the subjects, real emotions can be effectively elicited among people. Compared to facial expressions and speech data, which have some disadvantages in the field of actual application, such as needing a specific well-focused context and environmental noise—the advantages of well-known, pre-processed, and widely acknowledged private databases of well-collected non-subjective neural signals make EEG seemingly more suitable under non-controlling and natural environments [49].

2.2. Emotional Networks and EEG-Based Emotion Recognition

Motivated by the increased urgent need for real-time automatic emotion recognition in unobtrusive cognitive models of complex human behaviors, this systematic review first comprehensively reviews the recent progress of emotion recognition by analyzing how it is used in cognitive neuroscience. We aim to extract valuable key techniques and methods for developing the next generation of cognitive models of emotion recognition. Then, we identify a gap between cognitive neural models of dynamic emotional cognitive processes and rule- or plasticity-based static or classifier-based computational models of emotion recognition [50]. Motivated by this gap, this systematic review finally shows how real-world EEG-based effective computational emotion recognition has been developed and will be developed and outlines possible useful emotional and neural features unique to EEG data that can support and improve the development of the next generation of cognitive neural models of human emotions and emotional disorders [51]. Neural emotional networks encode emotions from core brain elements such as the amygdala, thalamus, prefrontal cortex, and related structures. This macro or functional network provides essential clues to neural models of emotions; that is, in addition to neural support, cognitive and real-world behavioral models should preferably capitalize on information measured from these emotional networks [52]. The capacity needed is consistent with our previous work supporting cognitive neuro-economical models. Ideally, neuro-economical models operate on a wireless measurement of emotional or implicit feedback measured from these neural elements. These models should be non-invasive and cost-effective for real-world applications [53,54,55].

2.2.1. Understanding Emotional Networks

Understanding the process underlying the generation and processing of emotional states is a key challenge in emotional and social neuroscience. The Papez circuit, consisting primarily of the prefrontal cortex, cingulate cortex, subcortical regions, and hippocampus, was initially described as the “emotional brain” and was accepted as the most relevant pathway for understanding the generation of basic emotional states for several decades. However, as new data has been made available, these ideas have been revisited. Currently, this network is considered part of the default mode network, including the anterior cingulate cortex and the insula [56]. An extensive body of evidence demonstrates that multiple brain structures generate, recognize, and regulate emotional reactions. These structures include the prefrontal cortex and limbic system-related regions, including the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, insula, orbital frontal cortex, and ventral striatum [57]. These and additional areas not considered part of the default mode network are more strongly activated during the generation or perception of emotional states [58,59].

A significant part of the research that describes the neurobiological aspects of emotion recognition has emerged from studying patients with neurological or psychiatric disorders. Patients with lesions in specific regions of the brain, particularly the prefrontal cortex and the limbic region, tend to present deficits in generating emotions [60]. Moreover, studies in subjects diagnosed with depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, antisocial personality, and schizophrenia have reported significant impairments in their ability to produce, interpret, and/or regulate their own and others’ emotions during interpersonal communications, which impairments are correlated with aspects of social cognition [61]. These observations suggest that success in emotionally motivated behaviors is associated with integrating numerous physical sensations, thoughts, and ongoing contextual and affective experiences and promptly producing the most appropriate responses. These observations underscore the importance of engaging the right NRF in each moment of interpersonal interaction [62,63].

2.2.2. EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Techniques

EEG-based emotion recognition relies on analyzing electrical activity in the brain to identify emotional states. This process typically involves two main steps: feature extraction and emotion classification. Feature extraction involves identifying and isolating relevant EEG signal characteristics, while classification applies machine learning or statistical techniques to categorize emotions based on these extracted features. Additionally, feature extraction is a crucial step in EEG-based emotion recognition, as it aims to extract discriminative features that represent underlying emotional states. The following are several commonly used feature extraction techniques:

- Event-Related Potentials (ERPs): ERPs are transient, time-locked EEG responses to specific sensory, cognitive, or affective stimuli. They are obtained by averaging EEG responses across multiple presentations of the same event, allowing researchers to isolate neural activity associated with emotional processing. Key ERP components, such as P300, N200, and LPP (Late Positive Potential), have been linked to emotional processing and cognitive evaluation of stimuli. ERPs provide high temporal resolution, which is ideal for tracking dynamic emotional responses. However, their dependency on repeated trials and controlled experimental conditions can limit their real-world applicability [64,65,66].

- Spectral Features and Frequency Band Analysis: EEG signals are decomposed into different frequency bands—delta (0.5–4 Hz), theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), beta (13–30 Hz), and gamma (30–100 Hz)—each of which plays a role in cognitive and emotional processes. For instance, increased theta and delta power is often associated with emotional arousal. At the same time, alpha asymmetry between hemispheres is linked to emotional valence (e.g., more significant left-hemisphere alpha activity is associated with positive emotions, while right-hemisphere dominance correlates with negative emotions). Spectral power analysis helps quantify these variations and is widely used in emotion recognition studies [67,68,69].

- Power Asymmetry Analysis: Emotional states are often associated with hemispheric asymmetry in EEG activity, particularly in the frontal cortex. The frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) model suggests that more excellent left-frontal alpha activity is linked to approach-related positive emotions. In contrast, right-frontal alpha activity is associated with withdrawal-related negative emotions. Power asymmetry analysis can effectively distinguish between emotional states, making it a valuable feature for EEG-based emotion recognition [70].

- Time-Frequency Analysis: This method integrates temporal and spectral information, allowing researchers to track how EEG power distributions evolve. Wavelet Transform (WT) and Short-Time Fourier Transform (STFT) are commonly used for time-frequency analysis in emotion recognition. These methods provide insights into transient changes in EEG rhythms that correlate with emotional responses, enhancing the robustness of emotion classification models [71].

- Effective Connectivity Analysis: Beyond analyzing isolated EEG components, effective connectivity methods assess how different brain regions communicate during emotional processing. Techniques such as Granger causality analysis, phase-locking value (PLV), and dynamic causal modeling (DCM) help quantify the directional influence of neural activity between brain regions. Effective connectivity metrics are beneficial for understanding the neural circuits underlying emotional experiences and have been applied in advanced emotion recognition frameworks [72,73].

2.3. Integration of Neural Networks and Emotional Networks

Integrating Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and Emotional Networks in EEG-based emotion recognition offers a promising avenue for enhancing our understanding of the neural mechanisms underlying affective states. This integration bridges computational intelligence with insights from cognitive neuroscience, enabling more accurate and adaptive emotion recognition systems. By leveraging deep learning techniques such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) and Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), emotion recognition models can extract discriminative EEG features while incorporating the dynamic properties of emotional networks observed in the brain’s limbic and prefrontal systems [74,75,76,77,78,79].

This paper presents a systematic review that explores EEG-based emotion recognition from the novel perspective of integrating neural and emotional networks. Unlike previous studies that primarily focused on either machine learning techniques or neuroscience-driven approaches in isolation, our framework synthesizes both domains, emphasizing their complementary roles in emotion detection. Specifically, our analysis addresses:

- How neural networks enhance EEG feature extraction by utilizing deep learning models to capture complex temporal and spatial EEG dynamics related to emotions.

- How emotional networks contribute to understanding affective processing, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and anterior cingulate cortex, which play pivotal roles in emotional regulation and perception.

- The application of hybrid neural–emotional models in real-time, subject-adaptive emotion recognition will pave the way for personalized AI-driven affective computing.

2.4. Research Questions

The research questions below are structured to connect technological advancements, experimental design, emotion recognition methodologies, and real-world implementations. These questions aim to bridge interdisciplinary approaches while emphasizing the role of neural and emotional networks in enhancing our understanding and application of emotion recognition systems.

RQ1: [Data-Driven Techniques] How can machine learning, data augmentation, and signal processing methods enhance the extraction and classification of EEG features for emotion recognition across diverse datasets and real-world conditions? This question addresses the need for advanced computational methods that overcome variability in datasets, improving the scalability and accuracy of EEG-based models in dynamic and diverse environments.

RQ2: [Experimental Paradigms and Approaches] What experimental setups, protocols, and stimuli are most effective in eliciting robust, ecologically valid EEG responses for studying emotional and cognitive processes across diverse populations? This question highlights the importance of ecological validity by focusing on the experimental design. It explores how experimental protocols can simulate real-world emotional experiences.

RQ3: [Emotion Recognition Techniques] What are the strengths and limitations of current EEG-based emotion recognition methodologies, and how can multimodal integration improve their real-time performance and adaptability in practical applications? This question examines the methodologies and multimodal techniques that enhance the real-time applicability of EEG-based systems while addressing their inherent limitations, such as noise and variability.

RQ4: [Behavioral and Cognitive Insights] How do EEG patterns reflect individual differences in emotional and cognitive processing, and what insights can they provide into personality traits, behavioral responses, and neuropsychological conditions? This question delves into the relationship between neural activity and individual differences, emphasizing the potential for personalized emotion recognition systems.

RQ5: [Applications and Ethical Considerations] How can EEG-based emotion recognition systems be applied effectively in real-world contexts, such as healthcare, education, and marketing, while addressing technical challenges and ethical implications? The final question extends the discussion to practical implementations, exploring the potential for EEG-based systems to transform various industries and the ethical considerations that must be addressed in such applications.

These interrelated questions serve as a comprehensive guide to understanding the multifaceted challenges and opportunities in EEG-based emotion recognition. They align closely with the manuscript’s objectives, offering a structured approach to integrating theoretical insights with practical applications.

3. Materials and Methods

This systematic review explores the interface between cognitive neuroscience, affective neuroscience, and practical applications of EEG-based emotion recognition with the PRISMA methodology (Supplementary Materials) [80]. This research will integrate studies concerning advancement in the integration of neural and emotional networks, with special attention to EEG-based emotion detection methods and their applications in real-world contexts, including healthcare, human–computer interaction, and marketing. The review covers methodologies related to feature extraction, emotion classification, and multimodal approaches, underlining novel machine learning techniques and signal processing methods. Current trends are discussed, including challenges in adaptability, real-time processing, and scalability for applications across different environments. Also, this review considers results from 64 studies in detail and underlines significant advancements and lacunae; therefore, it deeply recognizes the role of EEG-based emotion recognition in promoting interdisciplinary research and practical implementations.

3.1. Search Strategy

The query strings for each database/interface combination were designed to capture studies relevant to EEG-based emotion recognition, guided by the inclusion criteria and research objectives.

For PubMed, the query string was ((EEG OR “electroencephalogram”) AND (“emotion recognition” OR “affective neuroscience”) AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR CNN OR RNN)) AND (2000:2024 [Date-Publication]).

In Scopus, the search employed TITLE-ABS-KEY ((EEG OR “electroencephalogram”) AND (“emotion recognition” OR “affective neuroscience”) AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR CNN OR RNN)) AND PUBYEAR > 1999.

For Web of Science, the query was TS = (EEG OR “electroencephalogram”) AND TS = (“emotion recognition” OR “affective neuroscience”) AND TS = (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR CNN OR RNN) AND PY = (2000–2024).

Also, the Google Scholar search string used was “EEG emotion recognition” AND (“machine learning” OR “deep learning” OR CNN OR RNN) AND (“affective neuroscience”) after: 1999.

Finally, in PsycINFO via EBSCOhost, the query string was (DE “Electroencephalography” OR DE “EEG”) AND (DE “Emotion Recognition” OR DE “Affective Neuroscience”) AND (DE “Machine Learning” OR DE “Deep Learning”) AND (PY 2000–2024). These query strings incorporated Boolean operators and database-specific syntax to ensure comprehensive retrieval of relevant studies while filtering for publication years, methodologies, and focus areas.

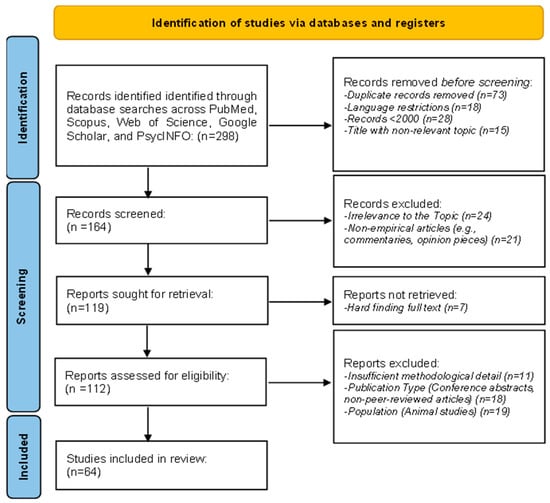

The search has been carried out following a systematic PRISMA methodology to ensure comprehensiveness. A protocol detailing the objectives, eligibility criteria, information sources, and analysis methods was registered on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/36qzj (accessed on 14 February 2025) | Registration DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/36QZJ) [81]. Database searches identified 298 records in the following databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and PsycINFO. After removing 73 duplicates, language restrictions excluded 18, and 28 records for publication dates before 2000 were removed; 15 more were for irrelevant titles, and thus, 164 remained to be screened. Of these, 24 records were excluded during screening as unrelated to the topic, and 21 were excluded as non-empirical works, that is, commentaries or opinion pieces. Full-text reports were sought for retrieval on 119 of these; 7 could not be accessed. Of the 112 reports assessed for eligibility, 11 were excluded due to insufficient methodological detail, 18 due to being conference abstracts, and 19 due to focusing on unrelated populations, such as animal studies. Finally, 64 studies were selected as eligible for inclusion in the final systematic review, providing a strong basis for the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of PRISMA methodology.

3.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established to maintain focus on EEG-based emotion recognition within cognitive neuroscience and its real-world applications.

Studies were included if they met all of the following criteria:

- Presented empirical findings on EEG-based emotion recognition and its applications in healthcare, human–computer interaction, education, and marketing.

- Were published in peer-reviewed journal articles between 2000 and 2024.

- Utilized EEG signal processing, machine learning techniques, or emotion classification frameworks.

- Involved human participants and provided relevant neuroimaging data applicable to emotion recognition.

- Were published in English.

Studies were excluded if they met any of the following criteria:

- Were non-empirical works such as commentaries, reviews, opinion pieces, or theoretical articles without experimental data.

- Included conference abstracts, gray literature, or non-peer-reviewed publications.

- Were published in languages other than English.

- Were published before 2000.

- Focused on animal studies unless explicitly related to neural mechanisms applicable to human emotions.

- Lacked sufficient methodological detail or did not meet the rigor required for systematic analysis.

- Were not directly relevant to EEG-based methods, emotion recognition, or neuroimaging techniques within the scope of cognitive neuroscience.

These criteria ensured the inclusion of studies that adhered to methodological rigor while directly applicable to the review’s objectives.

3.3. Risk of Bias Assessment

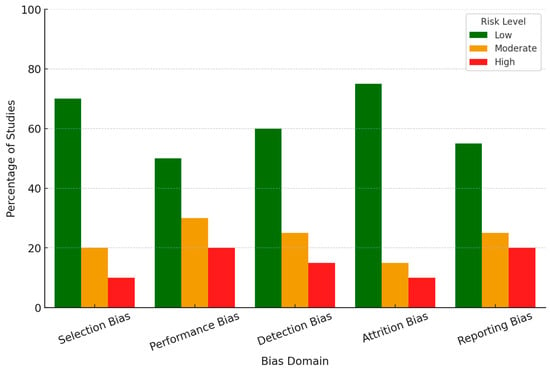

All the studies selected for this review underwent a systematic assessment for bias with an appropriate tool based on study design (Table 1). In this case, the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool was used for randomized controlled studies, while observational studies were assessed for their quality using the Newcastle–Ottawa Scale. Each study was evaluated for the five domains: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias (Figure 2). The selection of participants had a low risk of bias in some studies, where randomization techniques and appropriate inclusion/exclusion criteria were reported. However, the risk was unclear in a few studies because there was insufficient detail about randomization or recruitment methods. Regarding blinding, many studies involving EEG experiments, especially those in which emotional stimuli are administered, showed inconsistent practice. About 20% of the studies did not report whether the participants or researchers were blinded to the conditions or did so inadequately, presenting a moderate risk of performance bias. Most studies showed robust EEG signal acquisition and processing techniques with appropriate validation for machine learning-based emotion classification. However, incomplete validation procedures or lack of cross-validation were reported in some of the studies, which gave them a higher risk of bias regarding detection methods. Most of the studies had very minimal participant dropouts. However, several included studies did not report any methods for missing EEG data; thus, a moderate risk of attrition bias was introduced. In a few studies, selective outcome reporting was considered where either outcome was incompletely reported or replaced with exploratory findings, indicating a high risk of reporting bias. Of the 64 included studies, 60% were rated as low risk of bias, 25% as moderate risk, and 15% as high risk across the five domains. Most studies that showed a high risk of bias lacked methodological detail in randomization, blinding, or data handling. These biases were considered during the synthesis of results by focusing on the findings of the low-risk studies and discussing critically any potential bias of higher-risk studies. This provides a more robust and valid conclusion from this systematic review.

Table 1.

Research articles of systematic analysis (N = 64).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment across five domains.

4. Results

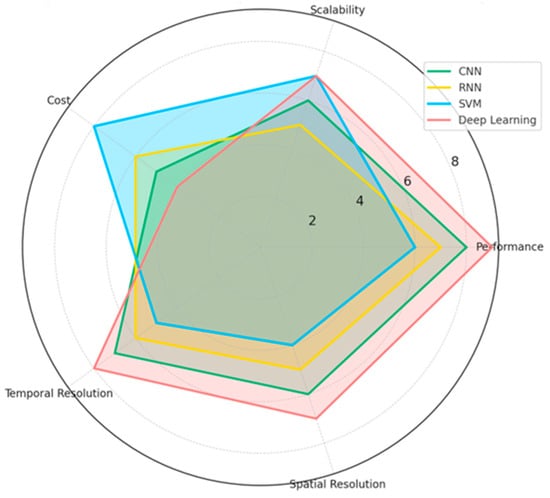

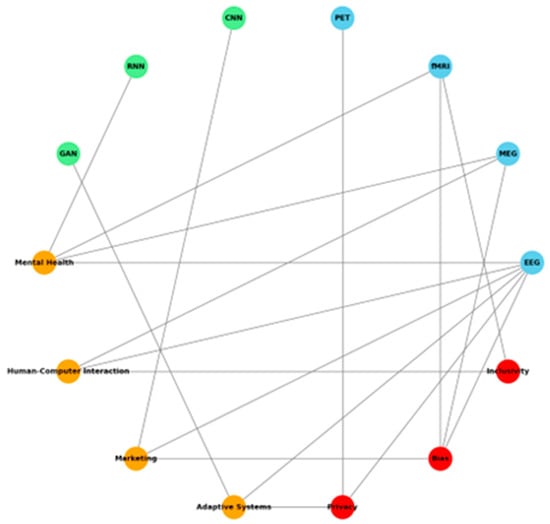

The results of this systematic review explore integrating EEG-based emotion recognition methodologies, neural networks, and their applications across diverse fields. In total, 64 studies showed the main trends in EEG feature extraction, classification techniques, and emotion recognition performance. The review discusses the leading machine learning methods, the most used EEG channels, and frequency bands. Moreover, it gives a clear visualization that helps the reader understand the strengths and limitations of each technique for its performance, scalability, and practical applicability in enhancing real-world applications such as healthcare, human–computer interaction, and marketing. The chart below (Figure 3) compares the machine learning techniques in EEG-based emotion recognition studies. Techniques such as CNN, RNN, SVM, and deep learning are assessed across key dimensions: performance, scalability, cost, temporal resolution, and spatial resolution. The results highlight the strengths and trade-offs of each approach. For example, deep learning excels in performance and temporal resolution, while SVM stands out for its cost-effectiveness and scalability. CNN achieves a balance across most metrics, whereas RNN demonstrates competitive scalability and temporal performance.

Figure 3.

Comparison of EEG techniques based on research insights.

4.1. [RQ1]: How Can Machine Learning, Data Augmentation, and Signal Processing Methods Enhance the Extraction and Classification of EEG Features for Emotion Recognition Across Diverse Datasets and Real-World Conditions?

Understanding EEG-based emotion recognition requires integrating advanced signal processing, feature extraction, and machine learning techniques. This section provides detailed analysis, structuring findings into distinct subsections: signal processing methods, feature extraction techniques, classification models, real-world applications, and methodological considerations. The extended discussion aims to critically analyze state-of-the-art methods and their limitations, fostering deeper insight into emerging trends and potential research directions.

4.1.1. Signal Processing Techniques for EEG Preprocessing

Effective preprocessing to reduce noise and enhance the signal quality is indispensable for emotion recognition. ICA remains one of the gold-standard techniques for eliminating electrical, muscular, and visual artifacts [109]. However, there are significant limitations to the application of ICA, especially regarding its sensitivity to parameter selection and computational cost. In return, AAR has been introduced as an implemented technique for eliminating eye movement and blinking artifacts [128]. The REST technique increases the emotional modulation effects at occipitotemporal electrodes and, when combined with band-pass filtering of 0.1–120 Hz, enhances the clarity of the signal [128]. Normalization techniques, such as z-score standardization and min–max scaling, reduce interparticipant variability, thus allowing for more robust generalization across datasets [132]. Other recent extensions include Kalman filtering for spike removal [140], cumulative general linear modeling to account for drift, and autoregressive modeling to correct serial correlations. These methods yield considerable improvements in the clarity of the EEG signal, thereby lowering error rates in subsequent classification tasks. However, these extensions increase the computational load and, as they are not yet standardized within different research groups, they also need to be validated.

4.1.2. Feature Extraction: Temporal, Spectral, and Connectivity Analysis

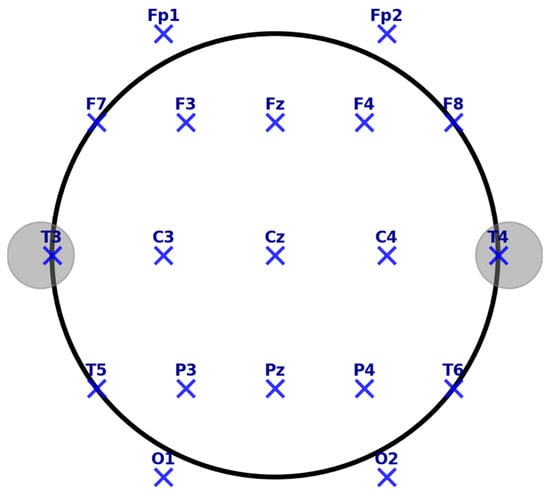

Feature extraction determines the discriminability of the emotional states from the EEG data. Temporal features include EEP, occurring at 120–180 ms post-stimulus at Fz, Cz, and Pz electrodes [114], and FRN is observed from 200 to 400 ms post-feedback at the frontocentral electrodes that provide the key information in the process of emotion recognition. It is essential to mention the 10–20 system, a standardized electrode placement method in EEG recordings, ensuring consistency across research and clinical applications. Electrodes are positioned relative to specific brain regions, facilitating studying cognitive and affective processes. In this system, electrodes are labeled based on their location:

- Frontal (F), Central (C), Parietal (P), Temporal (T), and Occipital (O) regions.

- Electrodes along the midline are denoted with a “z” (e.g., Fz, Cz, Pz) to indicate their position along the sagittal plane.

Key midline electrodes include the following:

- Fz (Frontal Midline)—Located in the prefrontal cortex, associated with cognitive control, attention regulation, and decision-making.

- Cz (Central Midline)—Positioned at the vertex of the scalp, crucial for sensorimotor processing and movement-related potentials.

- Pz (Parietal Midline)—Situated over the parietal cortex, involved in spatial cognition, working memory, and sensory integration.

The accompanying EEG electrode placement map (Figure 4) visually represents the 10–20 system, highlighting key electrode locations and their functional relevance. The layout ensures optimal coverage of neural activity, supporting accurate signal acquisition for emotion recognition and cognitive neuroscience applications. This standardized electrode configuration plays a fundamental role in EEG-based emotion recognition, providing a structured framework for analyzing emotional, cognitive, and physiological responses in real-world and experimental settings.

Figure 4.

EEG electrode placement (10–20 system).

Spectral feature analysis indicates emotion-specific frequency band dynamics. Delta-band activity is associated with motivational and behavioral inhibition processes [143], whereas gamma-band activity corresponds to the processing of positive emotional imagery [144]. The theta oscillations (4–8 Hz) have been related to cognitive control and emotional regulation, particularly in frontal regions [145]. Connectivity analyses allow higher-order views of neural interactions. Techniques such as lagged phase synchronization [109], discriminative spatial network patterns [129], and Imaginary Part of Coherency [135] reduce volume conduction artifacts and provide deeper insights into network-wide emotional processing. While these approaches enhance feature extraction, they require high computational power; therefore, real-time applications are impractical without further optimization.

4.1.3. Classification Techniques: Traditional and Deep Learning Approaches

Traditional machine learning and deep learning models have been applied to evolving EEG-based emotion recognition. Traditional classifiers, such as L1-regularized logistic regression, are computationally efficient and yield good generalization capability [132]. Polynomial kernel SVMs have also been robust in emotion classification tasks [102]. Deep learning models have significantly improved classification performance: Shallow ConvNet reaches 99.65% in mix-subject scenarios, while Deep ConvNet reaches 95.43% [128]. Transfer learning approaches integrating intra- and inter-subject classification strategies have further improved limited datasets. However, deep learning models require much-labeled data, which remains challenging given the few publicly available EEG datasets. A seminal study [134] has shown how deep learning models could predict conflict engagement with 95% accuracy and 33% over chance. In this work, the key neuro-physiological markers in the occipital cortex and superior frontal gyrus were identified to demonstrate the potential of deep networks in decoding emotion-related neural signatures. However, interpretability could not be ensured because of the black-box nature of the deep learning models, which introduces serious risks in critical domains such as healthcare.

4.1.4. Real-World Applications and Wearable EEG Devices

Wearable EEG devices revolutionized the applications of emotion recognition outside the laboratory. The Emotiv EPOC+ headset successfully measures six neural emotional parameters [113]. The Muse headband shows proper reliability within ecological contexts [87]. Despite such progress, environmental noise and inter-subject variability are formidable challenges [89]. The clinical applications of neurofeedback training based on EEG data are promising. Machine learning models have classified symptom severity in PTSD patients and predicted treatment outcomes for depression [118]. These studies suggest that EEG-based emotion recognition may have profound implications for diagnostics and intervention strategies in mental health. However, real-world implementation faces several challenges due to movement artifacts contaminating signals, the requirement for standardized protocols, and the poor battery life of portable EEG systems. These barriers can only be overcome with further development of adaptive noise filtering techniques and more efficient feature extraction methods.

4.1.5. Methodological Considerations and Future Directions

The evaluation of an EEG-based emotion recognition system must not be based solely on classification accuracy. In fact, AUC, sensitivity, specificity, and kappa statistics can also further indicate the quality of a model. It is still essential to consider cross-validation to avoid model overfitting [132], but variations in validation strategy in different research works call for unified benchmarking. A study [86] has shown that a low-pass filter at 30 Hz and a high-pass filter at 0.16 Hz could retain the emotional signals and eliminate the noise. These parameters may not be appropriate for all datasets; thus, adaptive filtering methods may be more suitable. Another important factor contributing to generalizability is the diversity of datasets. A demographic-balanced study of 11 participants (6 males, 5 females, 7 Asians, and 4 Caucasians) underlined the importance of diverse training for emotion recognition models [128]. Moreover, ecological validity is increased due to naturalistic paradigms like emotional film clips and IAPS images [97,135], further ensuring that emotion recognition systems perform well in the wild. For EEG-based emotion recognition, multimodal integration opens new perspectives. Robustness could be further improved by combining this modality with fMRI [127], behavioral measures [87], and physiological markers such as heart rate variability. Future work should consider adaptive approaches that will consider individual differences in neural responses, including creative self-efficacy-mediating variance and alexithymia-related emotional processing differences [145].

4.1.6. EEG Emotion Recognition Techniques and Performance

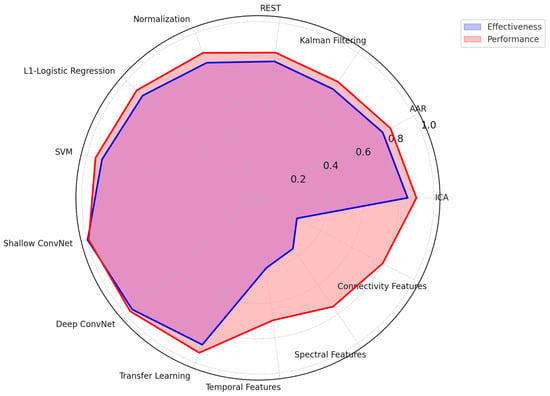

Figure 5 below shows a more integrated visual view into the effectiveness and performance of different EEG-based emotion recognition methodologies from three critical standpoints: (a) pre-processing techniques of signals, (b) model classification techniques, and (c) techniques to extract features. While having effectiveness in blue, overlaid by red, representing performance, one gets an account of various methodologies with trade-offs regarding their strength. Here are the key insights from the radar chart:

Figure 5.

Radar chart of EEG emotion recognition techniques and performance.

- Preprocessing Techniques

- ○

- Independent Component Analysis (ICA) and Normalization exhibit the highest effectiveness and performance, making them crucial for artifact removal and data standardization.

- ○

- Kalman Filtering and REST demonstrate moderate effectiveness but perform less due to computational complexity and real-time limitations.

- Classification Models

- ○

- Deep learning models (Shallow ConvNet, Deep ConvNet) outperform traditional methods, achieving high accuracy and robustness.

- ○

- SVM and Logistic Regression, while computationally efficient, show lower performance than deep learning approaches.

- Feature Extraction Methods

- ○

- Temporal, Spectral, and Connectivity-based feature extraction techniques all contribute significantly to emotion recognition.

- ○

- Spectral analysis demonstrates higher performance, likely due to its ability to capture relevant frequency-based neural patterns.

Accuracy, computational efficiency, and real-world applicability again show a trade-off in this analysis. While deep learning models and advanced preprocessing techniques have demonstrated high performance, their high computational cost presents a challenge in real-time EEG emotion recognition systems. Therefore, further research should optimize such techniques to assure high accuracy and feasibility in real-life applications.

In conclusion, machine learning, data augmentation, and signal processing techniques have significantly advanced EEG-based emotion recognition. Deep learning-based approaches achieved state-of-the-art classification performance, while new multimodal strategies promise auspicious improvements concerning real-world applicability. However, challenges include inter-subject variability and sensitivity to environmental noise. Refined preprocessing techniques, more diversity in the datasets, and integration of other complementary modalities will be necessary in future studies to further improve robustness and applicability. By continuously incorporating advances in computational models and tackling several methodological challenges, EEG-based emotion recognition could bring more real-life impact across the board of application domains, ranging from healthcare to human–computer interaction.

4.2. [RQ2] What Experimental Setups, Protocols, and Stimuli Are Most Effective in Eliciting Robust, Ecologically Valid EEG Responses for Studying Emotional and Cognitive Processes Across Diverse Populations?

Researchers have developed and refined various experimental setups, protocols, and stimuli to investigate emotional and cognitive processes using EEG across diverse populations. The most effective methodologies integrate standardized and naturalistic stimuli, multimodal approaches, rigorous experimental designs, and considerations for population-specific factors. The complexity of these experimental designs and their increasing relevance in applied settings necessitate a closer examination of each domain’s strengths, limitations, and advancements.

4.2.1. Stimuli for Inducing Robust Emotional and Cognitive EEG Responses

Standardized image databases, such as IAPS, have been commonly utilized to present emotionally salient stimuli within an EEG experiment to ensure similar responses across subject groups. These images are presented in blocks of positive, negative, or neutral content, which presents reliable neural correlations of emotion but includes necessary cool-down periods to minimize carry-over effects [135,139]. More recently, film clips have been used more because they possess more substantial ecological validity and are dynamic, capturing more complicated emotional responses than static images alone can provide [97]. Scientists have investigated that the point-light display effectively assesses emotion recognition using minimalist visual cues that isolate fundamental aspects of emotional processing [124,137]. Advances have also been made in creating more naturalistic social stimuli, with animated 3D avatars particularly useful in capturing emotion recognition and social cognition mechanisms [86]. Using dynamically emotional faces through face morphing algorithms has further improved stimulus realism and validity, enabling a more nuanced exploration of emotion recognition and regulation [140]. Recent studies have moved to multimodal stimulation, demonstrated by visual and auditory stimulation combinations, to increase ecological validity. For instance, it has been shown that presenting IAPS images with emotionally congruent auditory stimulation enhances EEG responses, indicating a deeper interaction between visual and auditory emotional processing [139]. Researchers investigating resting-state EEG paradigms have used slideshow presentations of natural versus urban environments to study their impact on emotional states, demonstrating that environmental context plays a crucial role in modulating neural responses [109]. The increasing adoption of multimodal approaches highlights the importance of integrating multiple sensory channels into experimental setups to capture a more comprehensive picture of emotional and cognitive processing.

4.2.2. Experimental Protocols and Paradigms

Such experimental paradigm refinement has significantly enhanced EEG research’s robustness in emotional and cognitive processes. The Affective Posner Task has been used to study emotion regulation patterns through attentional shifts. This indicates that attentional biases toward emotionally salient cues modulate early- and late-stage EEG components [134]. Cognitive reappraisal tasks have provided key insights into how individuals actively regulate emotional reactivity, with findings indicating distinct neural activation patterns associated with successful versus unsuccessful emotion regulation [120]. The Go/NoGo Emotion Recognition Task has been employed to examine the rapid categorization of emotional stimuli. ERP trials show distinct activity patterns in response to positive and negative facial expressions at approximately 170 ms at occipitotemporal electrodes [132]. These findings suggest emotion processing may involve early perceptual mechanisms and higher-order cognitive appraisals. Resting-state EEG has become a meaningful way to establish a baseline of neural activity associated with various emotional states. Many such studies, using pre- and post-stimulus resting-state EEG recordings, have investigated functional connectivity changes following an affective stimulus, which are differentially affected in various populations [109]. Indeed, the value of EEG for tracking stability and change in emotional processing over extended periods has also been shown in longitudinal studies. For example, neurofeedback training programs based on EEG-based markers of emotional regulation have reported significant changes in neural activity after weeks of training [82,142]. Longitudinal EEG studies have provided important information about the efficacy of therapeutic interventions and training regimens in modifying emotional and cognitive responses.

4.2.3. Technological Considerations in EEG Data Collection

Improvements in EEG technology have enabled better data capture for varying experimental conditions. High-resolution systems, like a 64-channel arrangement from NeuroScan, have been employed for various neurophysiological recordings; these arrangements give excellent temporal and spatial resolutions of brain activity [132]. This trend is further supported by the increasingly frequent use of portable EEG headsets, such as the Muse and Emotiv EPOC+, in real-world research settings due to their increased ease of use and better signal quality, thus enabling data collection in more naturalistic conditions [87,113]. Beyond integrating with other physiological measures such as fMRI, ECG, and GSR, it has further strengthened the capability to record complete data from both affective and cognitive processes [95,118,127]. Indeed, co-registered EEG-fMRI has been shown to provide complementary insights into the neural dynamics–brain structure interplay, especially regarding emotion regulation and decision-making processes [127]. Real-time neurofeedback applications have opened new avenues for adaptive interventions in emotional regulation. These studies using EEG-based video-game training report that participants can actively self-modulate their neural responses through continuous feedback, resulting in long-term improvements in emotional control and cognitive flexibility [88,89,140]. Such findings indicate the potential of EEG neurofeedback paradigms for therapeutic use, especially in populations requiring emotion regulation training. Preprocessing techniques such as realignment, spatial smoothing, and temporal filtering have enhanced the clarity of EEG signals, hence allowing high-quality data collection and analysis [140]. Sampling rates as high as 5000 Hz have enabled the capture of accurate temporal patterns of neural activity associated with emotional processing.

4.2.4. Population-Specific and Contextual Considerations

EEG investigations have diversified to include an increasingly broad range of populations, allowing the complex emotion and cognition interaction effects to be investigated across demographic and clinical groups. There are EEG studies investigating responses in terminal cancer patients receiving palliative care, which indicate altered affective processing due to chronic illness [122]. Chronic stroke patients also have distinct EEG features of emotional dysregulation that emerge, indicating a need for individually tailored interventions in neurorehabilitation [130]. The examination of EEG responses in female genocide survivors has provided critical insights into trauma-related emotional processing and the potential for neurofeedback-based interventions [89]. Professional groups, such as managers versus non-managers, have also been compared; occupational experiences shape cognitive and affective processing patterns [87]. Further, cultural influences have also been widely investigated, and EEG studies have also included a variety of ethnic backgrounds to identify universal and culture-specific patterns of emotional processing [128].

4.2.5. Future Directions and Integrative Approaches

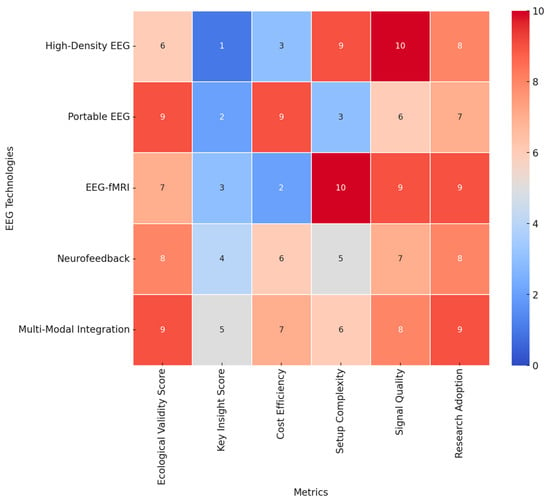

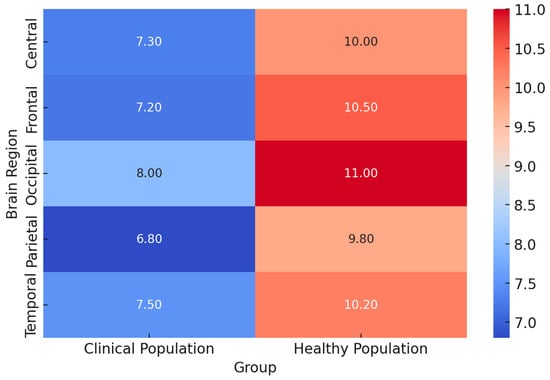

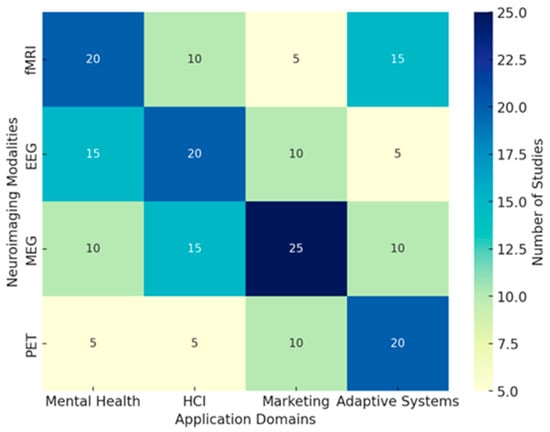

Future EEG research should be done to extend the use of real-world settings in enhancing ecological validity, with field studies assessing effective and cognitive processes in naturalistic environments. Refining personalized EEG paradigms to individual differences in emotional and cognitive traits will enable sensitive inquiries into neural variability. Neurofeedback interventions using real-time EEG adaptive algorithms hold promises of clinical use, especially in the mental health sector, where emotion regulation is among the critical therapeutic targets. Integrating machine learning techniques in analyzing EEG data will further enhance this, hence providing a more accurate classification of emotions and cognitions that may enable higher-order applications in brain–computer interfaces. While high-resolution recordings and multimodal integration remain key developing trends in the EEG research arena, population-specific adaptations will largely dictate the future of affective and cognitive neuroscience. In the interest of a broad review of these EEG technologies, we’ve designed a heat map displaying a few of these methodologies using key metrics. The ecological validity score, for obvious reasons, has the first weight, given the reason for assessment is to test ecological validity, i.e., the technology applied to real-life circumstances. Cost efficiency, the technical set-up complication level, the signal quality, and popularity within the studies’ rate supplementation will give this scoring more integrity. Figure 6 provides insights into key aspects considered on the heatmap below:

Figure 6.

Heatmap of EEG technologies: ecological validity and additional metrics.

- Ecological Validity: Portable EEG and multimodal integration techniques demonstrate the highest ecological validity (score: 9), making them ideal for real-world applications. High-density EEG, while offering superior resolution, has lower ecological validity due to its lab-based constraints (score: 6).

- Cost Efficiency: Portable EEG has the highest cost efficiency (score: 9), making it more accessible for large-scale studies and real-world applications. EEG-fMRI has the lowest cost efficiency (score: 2) due to the high operational and maintenance costs.

- Setup Complexity: EEG-fMRI has the highest setup complexity (score: 10), requiring specialized facilities, whereas portable EEG has the lowest complexity (score: 3), allowing for easy deployment in field settings.

- Signal Quality: High-density EEG provides the highest signal quality (score: 10), offering superior temporal and spatial resolution. Portable EEG, while ecologically valid, has lower signal quality (score: 6).

- Research Adoption: Multimodal integration and EEG-fMRI show the highest adoption rates in research (scores: 9), highlighting their importance in neuroscience and cognitive studies.

This intensive analysis of heatmaps now reveals the trade-off between ecological validity, cost, complexity, and signal quality within EEG research. Portable EEG and multimodal integrations are the most flexible approaches that balance usability and scientific rigor. High-density EEG and EEG-fMRI remain pivotal to high-resolution neural studies, though with reduced ecological applicability. These insights will provide a valuable framework for selecting appropriate EEG technologies based on research objectives and practical constraints. The resulting visualization can be a decision tool for researchers to optimize experimental settings concerning feasibility, accuracy, and ecological relevance in EEG studies into emotional and cognitive processes across diverse populations. In conclusion, the most potent EEG experimental paradigms combine standardized and naturalistic stimuli with rigorous task designs, multimodal integration, and population-specific considerations. The development of real-time analysis, wearables, and ecological validity inspires the future of EEG emotion and cognition research. It remains key to finding a balance between methodological rigor and real-life relevance to further our understanding of neural responses to emotional and cognitive processes across diverse populations.

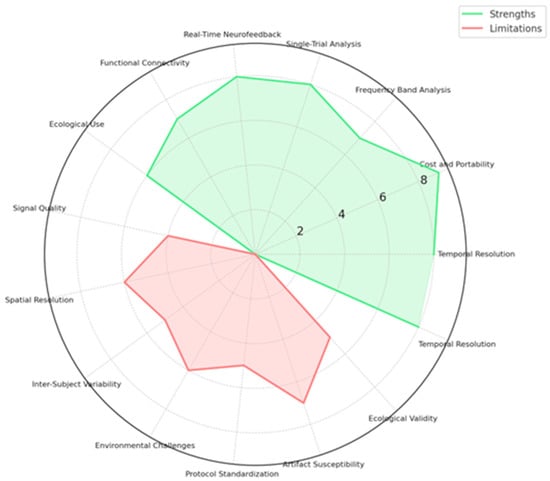

4.3. [RQ3] What Are the Strengths and Limitations of Current EEG-Based Emotion Recognition Methodologies, and How Can Multimodal Integration Improve Their Real-Time Performance and Adaptability in Practical Applications?

Among various promising methodologies, EEG-based emotion recognition has emerged to capture rapid neural responses associated with emotional processes. However, several challenges restrict their applicability in real-world scenarios and call for exploring practical approaches to multimodal integration for improved performance and adaptability. In this regard, this section critically analyzes the strengths and weaknesses of the methodologies of EEG-based emotion recognition concerning issues related to the signal processing aspect, generalizability, and real-time application. It also discusses how the multimodal approach, especially the combination of EEG with other physiological and neuroimaging modalities, may help to overcome these challenges and move toward more robust and practical emotion recognition systems.

4.3.1. Strengths of EEG-Based Emotion Recognition

Another essential benefit of EEG-based emotion recognition is the high temporal resolution; even emotional responses that occur several milliseconds after stimulation can be elicited. Numerous studies have shown that EEG may be sensitive to emotional effects as quickly as 20 ms after stimulus onset, thereby supplying crucial insights about the beginning of emotional processes [139]. Non-invasiveness and the capability to measure rapid neural dynamics make EEG particularly suitable for applications requiring real-time monitoring of emotional states, such as brain–computer interfaces and affective computing systems [132]. In addition, EEG has played a key role in studying event-related potentials, including the well-known N170 and P300 components, which have been widely used to differentiate between positive and negative emotional stimuli. With these well-defined neural markers, EEG-based emotion classification models become more reliable in detecting affective states across different experimental conditions with high accuracy [133].

Another strong point of EEG is that it is non-invasive and relatively inexpensive compared to other neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In modern times, relatively cheap and easy-to-operate EEG devices have helped modern EEG devices become common in both laboratory and real-world settings, including wearable EEG headsets such as Emotiv EPOC+, which have already demonstrated effective emotion recognition capabilities in natural environments [113]. Furthermore, EEG offers fundamental information in the frequency domain, where discrete frequency bands are associated with different emotional states. Alpha-band activity has been proven sensitive to emotional stimuli; asymmetry in frontal alpha power commonly signals emotional valence [92]. Larger scales have been used, though; recording delta and gamma band activities in EEG has reported high-arousal emotional states, further expanding the possibility of identifying such affective states [135]. Despite these advantages, EEG-based emotion recognition has limitations, mainly when conducted outside controlled experimental settings. This section addresses significant challenges encountered by EEG-based emotion recognition systems in terms of the quality of signals, spatial resolution, individual variability, and ecological validity.

4.3.2. Limitations and Challenges in EEG-Based Emotion Recognition

Signaling quality is the most resistant problem in developing an EEG-based emotion recognition system. In general, raw EEG data easily gets exposed to various muscle and eye blinking-related artifacts and can easily deteriorate due to noise. A real-time application suffers from these artifacts because using efficient preprocessing methods will lose crucial emotional information due to noise filtration. This increases the complexity of the EEG signal processing pipeline and may hinder the feasibility of real-time emotion recognition outside of controlled environments [132]. Apart from that, EEG inherently maintains the issue of spatial resolution, as it mainly records cortical surface electrical activity and provides limited access to deeper brain structures involved in critical emotional processing, such as the amygdala and hippocampus. This is the limitation of the spatial grounds that decrease the capability of EEG in presenting a full image of the neural mechanisms behind the emotion and needs integration with fMRI for high spatial resolution imaging [118].

Another limitation is the well-known inter-subject variability problem that seriously interferes with generalization in models for emotion recognition. Individual differences in neurophysiology, baseline EEG pattern, and emotional reactivity may yield substantial variability in EEG signals, so a single model that demonstrates generally good performance across different subjects may hardly be found. Research has indicated that models trained on one group of participants fail to generalize well to new subjects. Therefore, adaptive and personalized approaches are necessary for EEG-based emotion recognition [128]. Furthermore, the success of EEG-based emotion recognition largely depends on the conditions under which data is collected. Various studies have utilized carefully controlled stimuli in laboratory settings. However, applying these findings to real-world environments presents significant challenges due to factors such as environmental noise, distractions, and varying levels of user engagement during EEG acquisition. These inconsistencies reduce the reliability of emo-tion classification algorithms when deployed outside the lab [113]. These limitations have driven the investigation of multimodal approaches for enhancing robustness and accuracy in EEG-based emotion recognition, often in combination with other physiological and behavioral measures. The following section will discuss how multimodal integration can balance the deficiencies of EEG to improve real-time performances in applications involving emotion recognition.

4.3.3. Enhancing EEG Emotion Recognition Through Multimodal Integration

Integrating multimodal approaches represents a set of emerging solutions to such challenging issues, including multiple sources related to physiological and neuroimaging aspects of EEG-based affective detection. One of the most feasible modalities involves integrating EEG with functional magnetic resonance imaging to compensate for the latter’s poor resolution by offering extensive anatomic visualization of the affective activities of the brain. Studies have demonstrated that EEG-fMRI integration enables the simultaneous capture of high-temporal and high-spatial-resolution data, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of the neural correlates of emotion [118,142]. This approach has been particularly valuable in clinical applications, where precise localization of brain regions involved in emotional processing can aid in developing targeted interventions for mood disorders.

Another popular multimodal approach includes the combination of EEG with other physiological signals like electrocardiography and galvanic skin response. These physiological markers provide additional information on the activities of the autonomic nervous system, which plays a vital role in emotional arousal and regulation. Indeed, studies have indicated that including heart rate variability measures along with EEG improves the detection of stress and emotional arousal, resulting in better classification accuracy than using EEG only [95]. Similarly, incorporating facial expression analysis and video-based behavioral tracking has improved emotion recognition performance by adding observable affective cues to neural data [145].

Besides the advantages of multimodal signal integration, recent advances in machine learning further play a vital role in promoting the adaptability of EEG-based emotion recognition systems. By applying deep learning techniques, such as CNN and RNN, a very competitive performance increase can be achieved, which allows some research works to realize high-reliable and near real-time emotion recognition. Researchers have shown that CNNs are particularly good at extracting hierarchical features from the raw EEG signals, providing better generalization across subjects and experimental conditions [117,128]. Besides, performing transfer learning and domain adaptation helps tackle inter-subject variability with limited re-training over a new user by the model [129].

4.3.4. Future Directions and Practical Applications

Integrating EEG-based emotion recognition with real-time neurofeedback systems holds significant clinical and practical application potential. Neurofeedback is training wherein real-time visual or auditory information is provided about the activities of the brain, which can help in achieving better emotional regulation and reduce the symptoms of various psychiatric disorders like PTSD and depression. Clinically meaningful symptom severity reductions have been reported after EEG-based neurofeedback interventions, indicating the great potential of such systems for mental health applications [89,119]. Furthermore, wearable EEG devices have opened new avenues for continuous emotion monitoring in everyday settings, enabling applications in human–computer interaction, affective gaming, and personalized healthcare [113].

Although significant strides have been made in developing EEG-based emotion recognition technologies, many obstacles must be addressed regarding broad applicability. Further advances will require attention to the standardization of experimental protocols, enhancing robustness against environmental variability, and elaborating ethical frameworks governing the responsible use of effective computing systems. Conquering these identified challenges above would, therefore, demand interdisciplinarity between neuroscience, artificial intelligence, and human–computer interaction research. Further developments in multimodal integration and adaptive learning algorithms may provide a broader pathway to more practical and scalable emotion recognition systems. This brings us closer to the real-world implementation of real-time, user-adaptive, and ethically responsible applications in EEG-based affective computing.

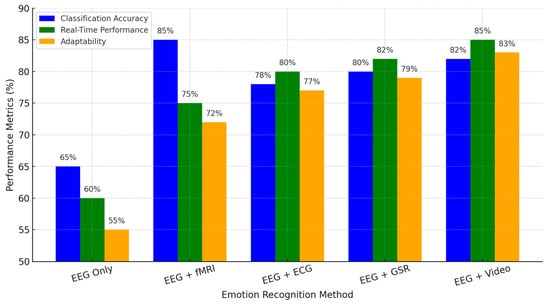

Figure 7 below compares three different EEG-based emotion recognition approaches, including advantages and disadvantages concerning their unimodality and multimodality on classification accuracy and real-time and adaptability properties. EEG-based approaches show only the lowest ratings in all criteria, revealing many limitations in a single modality regarding signal reliability, spatial resolution, and poor generalizability. Complementing EEG with fMRI, ECG, GSR, and video significantly enhances recognition accuracy and improves real-time adaptation, addressing major challenges in EEG-based emotion detection.

Figure 7.

Strengths, limitations, and multimodal integration in EEG-based emotion recognition.

EEG + fMRI offers the best classification performance at 85% due to the good spatial resolution provided by fMRI. At the same time, this modality lags in real-time performance due to its computationally complex nature with a processing delay. EEG + ECG and EEG + GSR demonstrate better real-time efficiency and are suitable for wearable and clinical applications, particularly in mental health monitoring and affective computing. EEG + Video: This is a balanced approach toward the multimodal capture of neural and behavioral emotional responses. Thus, it has the most relevance to human–computer interaction applications and AI-driven emotion recognition systems.

This comparison underlines how effectively multimodal integration compensates for the intrinsic weaknesses of EEG and points toward paths involving practical, real-time, and adaptive solutions for emotion recognition. Advances in machine learning, real-time data fusion, and personalized neuroadaptive systems are foreseen to further refine this methodology at higher robustness for applicability in natural environments.

4.4. [RQ4] How Do EEG Patterns Reflect Individual Differences in Emotional and Cognitive Processing, and What Insights Can They Provide into Personality Traits, Behavioral Responses, and Neuropsychological Conditions?

EEG patterns provide valuable insights into individual differences in emotional and cognitive processing. These neural markers reflect relationships with personality traits, behavioral responses, and neuropsychological conditions. To enhance analytical depth, this section examines how EEG markers contribute to understanding cognitive and emotional variability across individuals.

4.4.1. EEG and Emotional Processing in Neurodevelopmental and Clinical Populations

EEG studies have also shown significant variability in emotional processing across neurodevelopmental and clinical groups. For example, individuals with Asperger syndrome have weaker theta synchronization, indicating atypical emotional regulation [141]. Other EEG-based assessments have identified differences in emotional processing pre- and post-therapy, including improved affective regulation following music therapy in cancer patients [122]. EEG patterns, especially, prove to help characterize emotional impairments. Research using single-trial N170 ERPs has shown that EEG features accurately classify positive and negative emotional stimuli [132]. The implication is that EEG is diagnostic and useful in monitoring therapeutic outcomes and behavioral changes across different populations. Moreover, differences in the EEG components reflect differential emotional reactivity and provide a neural basis for understanding why some individuals show heightened sensitivity to emotional stimuli while others evidence blunted responses.

Table 2 below summarizes comparisons related to EEG features observed in Asperger syndrome, ASD, schizophrenia, MDD, GAD, and PTSD from the perspective of several neurodevelopmental and clinical conditions, including all conditions under discussion. Key abnormalities include altered theta synchronization, increased variability, and power fluctuations across the frequency spectrum. These neural markers relate to cognitive and emotional dysregulation and give important diagnostic and therapeutic insights. The table has underlined EEG as one of the essential approaches in studying neural signatures associated with the conditions and helping assist in early detection and personalized strategy treatment.

Table 2.

EEG Features in Neurodevelopmental and Clinical Conditions.

4.4.2. EEG and Personality Traits in Emotional Responses

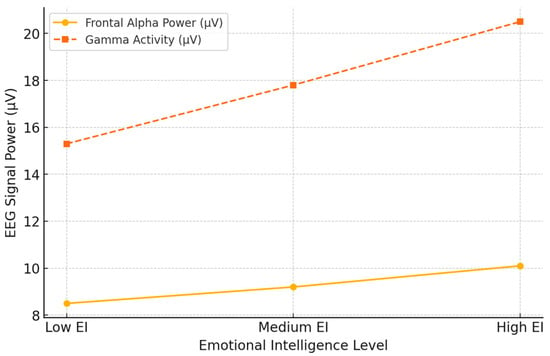

EEG coherence and neural activation patterns reflect personality-driven emotional processing. High-EI individuals exhibit higher EEG coherence in social perception-related brain areas, while low-EI individuals show object perception tendencies [93]. These differences become real-time in emotional interactions: the EEG signatures of emotional intelligence align with behavioral adaptability. The studies reveal a negative correlation between left amygdala activation and susceptibility to anger, underlining neural markers of emotional reactivity [144,145]. This implies that EEG can help predict emotional responses from personality, providing a quantified measure of a person’s ability to regulate affective states. Moreover, highly empathetic individuals show higher cortical gamma activity in response to emotional stimuli [115], supporting that EEG markers can discern individuals according to their emotional sensitivity and social responsiveness. These findings have practical implications for tailoring interventions that enhance emotional intelligence and stress resilience.

Figure 8 below shows EEG variations in individuals with different levels of Emotional Intelligence by comparing Frontal Alpha Power and Gamma Activity across low, medium, and high EI groups. The results showed that individuals with higher EI exhibited increased frontal alpha power, reflecting better emotional regulation and cognitive flexibility. Also, gamma activity, reflecting enhanced neural processing and emotional sensitivity, was higher in individuals with greater emotional intelligence.

Figure 8.

EEG variations across different emotional intelligence levels.

These findings correspond with previous evidence that higher emotional intelligence parallels more efficient neural activity in affective brain areas. Again, the increasingly higher scores obtained in both measures from the Low to High EI groups point to the potential that EEG biomarkers may have for evaluating emotional intelligence and related cognitive–emotional functions. Such neural markers may provide essential insights into tailored emotional control and social cognition interventions.

4.4.3. EEG and Cognitive Processing Efficiency

EEG patterns also reflect cognitive control, decision-making, and attentional regulation. It is possible to make single-trial EEG data-based individualized predictions of cognitive efficiency and response speed [117]. P300 amplitudes correlate positively with attentional focus and short-term memory performance [125], which indicates that these signals can act as biomarkers of cognitive workload and information-processing efficiency. EEG theta-band activity was associated with higher executive control and better adaptive emotional functioning [100]. Further, different degrees of frontal-midline theta power also serve as essential markers concerning the extent to which cognitive control mechanisms are adequate to afford complex problem-solving and high-stakes decisions. EEG-based assessments could have limited applications in cognitive performance training. Those who revealed the poorest degree of cognitive control would most likely benefit from neurofeedback intervention centered on attention optimization and executive functions.

4.4.4. EEG and Emotional Regulation Strategies

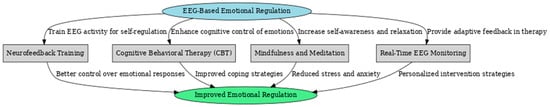

EEG’s role in emotional self-regulation is given in biofeedback and therapeutic practice. Neurofeedback interventions using the mentioned EEG markers have been reported to be effective in enhancing emotional self-regulation, mood stability, and anxiety management [119]. Increased frontal activation is related to better emotion regulation [97], thus setting a neurophysiological basis for behavioral therapies focused on enhancing cognitive control over emotional reactions. EEG-based measures also predict treatment efficacy in various psychological interventions, further strengthening their clinical value [122]. The potential impact of such a skill in regulating affective states through EEG-guided self-regulation could be far-reaching, ranging from improved resilience to stress to reduced emotional dysregulation in psychiatric disorders. Figure 9 below depicts, in flowchart form, some EEG-based emotional regulation interventions by describing mechanisms and expected outcomes. The central concept of EEG-based emotional regulation is linked to four key intervention strategies:

Figure 9.

Flowchart of EEG-based emotional regulation interventions.

- Neurofeedback Training—This method trains individuals to regulate their EEG activity, enhancing self-control over emotional responses. By reinforcing desired brainwave patterns, neurofeedback helps improve emotional stability and resilience.

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)—EEG can be used alongside CBT to enhance cognitive control of emotions. Real-time EEG monitoring allows therapists to track neural correlations of emotional regulation and adapt treatment strategies accordingly.

- Mindfulness and Meditation—EEG-guided mindfulness practices help individuals develop greater self-awareness and relaxation. Increased alpha and theta activity, commonly observed during meditation, improves emotional regulation and reduces stress.

- Real-Time EEG Monitoring—This approach provides adaptive feedback during therapy sessions, helping clinicians personalize interventions based on a patient’s real-time emotional and cognitive state.

All these interventions lead to improved emotional regulation, with specific outcomes such as better control over emotional responses, enhanced coping strategies, reduced stress and anxiety, and personalized therapeutic approaches. This flowchart highlights the integrative role of EEG in developing targeted interventions for emotional and mental well-being.

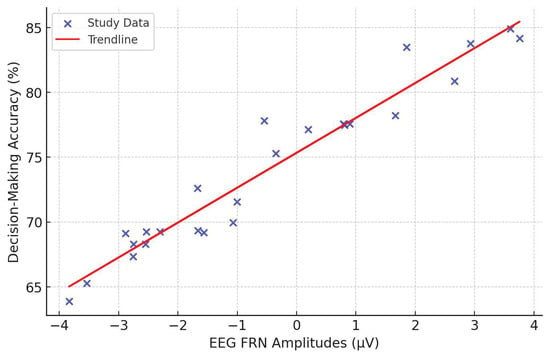

4.4.5. EEG and Reward-Based Decision-Making

Among neural markers of decision-making and reward sensitivity are the EEG-based measures. FRN amplitudes are higher in individuals with high reward sensitivity but low risk-taking propensity [90], which implies that EEG components help outline certain cognitive biases within decision-making frameworks. P300 amplitudes reflect attention allocation and cognitive decision-making processes, as shown in studies [86,87], further depicting how EEG works in understanding the mechanisms of risk evaluation and reward processing. EEG-derived emotional positivity indexes sensitivity to affective primes 130, underlining the complex neural interaction of cognition and affective influences on decision-making. The knowledge obtained will be instrumental in setting up more precise predictive models concerning consumer behavior, financial decision-making, and psychological treatment concerning maladaptive risk-taking attitudes.