Abstract

Background/Objectives: Studies on executive functions in child sex offenders relate their findings to the presence of pedophilia, but they are not able to distinguish between paraphilia and abuse. It is therefore this lack of a distinction that leads us to complement the existing information. Thus, the purpose of this review is to find all available evidence on the neurocognitive and neuroanatomical differences in executive functions among pedophilic and non-pedophilic child sex offenders, and non-offender pedophiles. Methods: The present review, in accordance with the PRISMA statement, ran a systematic search of three databases (Web of Science, Scopus and ProQuest). This search identified 5697 potential articles, but only 16 studies met all the inclusion criteria. Most of the studies were conducted in Europe, using a cross-sectional design with a convenience sample. Results: The results showed alterations in frontal, temporal and parietal structures related to executive functions (e.g., response inhibition) in child sexual offenders, regardless of the presence of pedophilia. Conclusions: In summary, there are differences in brain structure underlying executive functions related to child sexual abuse, but not to pedophilia as such.

1. Introduction

Sexual behavior is one of the most restricted and regulated biopsychosocial processes according to established social norms [1]. Therefore, any sexual affinity that does not correspond to genital or preparatory stimulation with phenotypically normal, physically mature and consenting human partners, within the cultural landscape, is found to be objectionable, abnormal or demeaning [2]. These atypical preferences correspond to what we understand as paraphilias.

One of the most common paraphilias is pedophilia, from the Greek “paidíon-” (children, prepubescent), “-philein/-philos” (love, inclination for, affinity) and “-ia” (quality of). It is translated as the quality of having sexual inclinations toward or an affinity for children or prepubescents. Pedophilia can be understood as an affective or romantic inclination to prepubertal individuals, as a psychological or neurological disorder, or as a sexual inclination including desires, fantasies, thoughts and behaviors [3,4].

On the other hand, child sexual abuse is a term that refers to people who maintain some kind of sexual approach to a minor without his or her consent, apparently related to the phenomenon of pedophilia. In fact, between 50% and 60% of child sex offenders are considered pedophiles [3,5], but this does not establish any causal relationship. Child sexual offenders usually have some characteristics in common, such as a difficulty relating to adults (affinity for children due to congruence with the emotional immaturity of minors), an inability to satisfy emotional and sexual needs, a need for power and control over the other, a lack of self-control (impulsivity), and behavioral disinhibition [6,7,8]. In addition to these, they may also present, in some cases, pedophilic inclinations.

How is child sexual abuse understood from the perspective of neurobiology and psychology?

So far, it has been suspected that pedophilia not acquired by brain injury or damage may be associated with neurodevelopmental disorders [9], although the origin of these alterations and their influence on pedophilia remain unclear. In contrast, numerous studies demonstrate alterations in child sex offenders at the behavioral level [3], at the personality level [10,11] and at the neurocognitive level. But it is not clear whether or not there is a distinction at the neurobiological level between pedophiles and child offenders, since a pedophilic inclination does not necessarily move a person to act according to his or her fantasies [12] and, even less so, to act without consent.

In studies related to child sexual abuse and pedophilia, different theories have been developed. Among the most popular ones related to executive functions is the “frontal lobe” theory [13,14,15,16,17]. This theory refers to alterations in the prefrontal, orbitofrontal and right and left dorsolateral cortex in male pedophiles, whether they have idiopathic (with unknown origin) or acquired (following brain damage) pedophilia [18]. However, these alterations have not allowed for discernment between pedophiles who have committed abuse and those who have not. This leads to the conclusion that the existing evidence does not clarify the role played by sexual preferences [19].

Another theory along the same lines, the motivation–facilitation model [5,20], explains the role that inhibitory control plays in the strong motivation that may appear in the presence of pedophilia. This control could be altered in individuals who go on to commit the act of sexually abusing a minor.

There is also a theory that combines the frontal lobe theory with the temporal lobe theory. The latter refers to the idea that dysfunctions in the temporal lobe could be behind hypersexuality, a frequent characteristic seen in sexual abusers [21]. Therefore, impulsive behavior could be explained by a dysfunction in frontal structures, and its relationship with the need to meet sexual demands could be explained by the simultaneous alteration of temporal structures. However, the possible influence of sexual preferences has not been clarified either. Along the same lines, it was precisely found that dysfunction in fronto-temporal regions was not associated with pedophilia, but with child sexual abuse exclusively [22,23]. Therefore, the relationship between brain dysfunctions associated with impulsive behavior and pedophilia remains a mystery.

Some authors have already become aware that most studies on pedophilia have included a sample of pedophiles who had sexually abused minors and, therefore, that the conclusions were associated with the paraphilia and not with the criminal act; i.e., they did not differentiate between pedophilia and sexual abuse [24,25,26]. One study conducted the first large-scale research effort that differentiated between pedophiles and non-pedophiles, as well as between individuals who had and had not committed sexual abuse. The study identified factors associated with different sexual practices (such as greater impulsivity in pedophile offenders) but did not specify the brain structures responsible for these factors. However, the study did suggest that executive functions may be altered in this type of behavior [24].

Executive functions are understood as all those higher cognitive structures and/or processes that direct, control and facilitate adaptation to new and complex situations, beyond habitual and automatic behaviors [27]. Some of these functions are working memory, behavioral self-control, response inhibition, processing speed and cognitive flexibility, among others [28].

The importance of this study lies in understanding the factors underlying child sexual abuse crimes, with the ultimate goal of helping professionals dedicated to the study of human behavior and its legal implications prevent and evaluate this type of behavior. The present study emphasizes the biological factor, determining whether there are neurobiological alterations in the executive functions of child sexual abusers and whether this phenomenon may be related to sexual preferences. For psychology professionals, it is necessary to detect all risk factors that may predispose individuals to a behavioral alteration of high impact on society, such as child sexual abuse, regardless of whether these factors are biological, psychological or social. A holistic understanding of the causes of child sexual abuse can increase prevention and direct intervention more efficiently in those individuals susceptible to committing this type of behavior.

Created following the PICO methodology, the research question on which the present study was based is as follows: are there differences in executive functions in people who have been convicted of pedophilia versus those who have not committed this type of crime? The aim of this systematic review was to find all the evidence in the literature of neurocognitive and neuroanatomical alterations related to executive functions in order to find differences between pedophile and non-pedophile samples, including both people who have sexually assaulted children and those who have not.

We structured and directed the review around our main question: will the findings differentiate pedophilic and non-pedophilic child sexual abusers?

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a systematic review according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA 2020) statement [29] (see Appendix A). This review was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42022380686), which confirmed that the present study was not duplicated and was free of any reporting bias.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria: (1) are empirical and original research; (2) are published in a peer-review scientific journal; (3) focus on altered sexual behavior toward minors (with and without consummated sexual abuse); (4) examine neurobiological and/or neurocognitive evidence in relation to executive functions; (5) use a sample of adults (i.e., over 18 years of age); (6) include a comparison between adults with different degrees of altered sexual behavior toward minors (taking into consideration pedophilia with and without consummated sexual abuse) and a control group of adults with no altered sexual behavior; (7) are written in English, Spanish, Catalan, French or German. These languages were included according to the authors’ domain. No geographical and time limits were established in the search for studies.

2.2. Search Strategy

Several search strategies were used. In order to establish a specific search strategy, we used the PICO reference [30]. We established inclusion criteria that defined the sample (non-probabilistic sampling by convenience that includes pedophilic and non-pedophilic men who had committed child sexual abuse or had not), the intervention or study objective (neurobiological and/or neurocognitive evidence in relation to executive functions) and the type of study to be compared (exploratory–comparative observational studies) and finally, compiled the results in order to draw conclusion

Then, an electronic search of all databases was performed between November 2022 and October 2024, obtaining representative results in the following three databases: Web of Science, Scopus and ProQuest. In this search, we used the following keywords in the English language: rape* OR rapist* OR “sexual abuse” OR “sexual offender” OR “sexual assault” OR pederast* OR pedophil* AND brain* OR neuroanatomic* OR neurocogni* OR neurobiologic* OR “executive function” OR “attentional control” OR “cognitive inhibition” OR “working memory” OR “inhibitory control” OR “cognitive flexibility. These keywords were combined in different ways and the search strategy was adjusted according to the specific requirements of each electronic database. A total of 5697 studies were identified across all databases (Web of Science: 2265 references; Scopus: 2025 references; and ProQuest: 1407 references).

Secondly, a manual review of reference lists of prior systematic reviews and meta-analyses [9,10,12,18,23,31,32] as well as a reference list of studies included in the present systematic review was performed to identify potential additional studies. This search strategy led us to identify 20 potential studies.

2.3. Study Selection Procedure

The selection procedure was carried out in two phases (pre-selection and selection). Each phase was carried out independently by one of two researchers. Disagreements were resolved through discussion, and, if necessary, a third researcher was consulted.

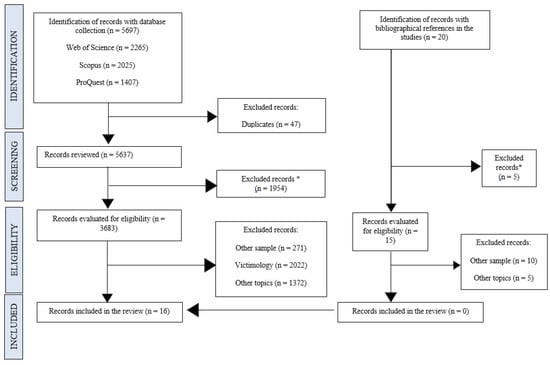

Figure 1 displays a flowchart of the selection procedure. A total of 5697 potential articles were identified through electronic research and reviewed based on their titles and abstracts for eligibility. After 1954 references were removed because their abstracts did not match the inclusion criteria, 3683 full texts were examined. Of them, 3667 studies were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria: 271 studies did not have a control sample, 2022 based their findings around victimology and 1372 studies only took some neurobiological and/or neurocognitive factors in executive functions but not as the main topic. Therefore, the search identified 16 published articles to be included for review, all written in English and published in peer-reviewed journals between 2009 and 2024.

Figure 1.

Prisma 2020 flow diagram of study selection process. * Records excluded because they do not follow the research format. They are written in other formats, mainly systematic reviews, meta-analyses and case studies.

In the manual literature search, a total of 20 potential articles were identified from the bibliographical references of the studies included in this review. The same eligibility criteria were applied, excluding 10 articles due to the sample type, 5 articles that did not include the topic of interest and another 5 that were reviews of the literature. Three of the studies were meta-analyses [9,18,32] and two were systematic reviews [12,31]. Finally, there were no articles left in the manual search to be included in the review.

2.4. Data Extraction

A protocol for data extraction from primary studies was established. Two independent researchers carried out data extraction in a systematic and standardized way. Once again, any disagreements were resolved by consensus, and a third researcher was consulted if required. The characteristics extracted were as follows: (1) authors and year of publication; (2) geographical location (country); (3) methodology (quantitative, qualitative or mixed); (4) research design (longitudinal vs. cross-sectional); (5) sampling method (randomized sample vs. convenience sample); (6) sample size; (7) setting (target population); (8) participants’ age; (9) gender distribution; (10) ethnicity distribution; (11) tools for assessing sexual offenders; (12) tools for assessing cool executive functions; and (13) type of pedophile (child abuse committed vs. child abuse not committed).

2.5. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

The quality of the primary studies was examined using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation, or GRADE [33,34]. The GRADE evaluates the quality of scientific evidence in the clinical and health sciences setting. The GRADE assesses six aspects through a series of items and conditions to be met: (1) the study design; (2) directness (patient population, diagnostic test, comparison of test); (3) the consistency of the results (similar in different studies); (4) the precision of the evidence (according to existing information in the literature); (5) the risk of bias (limitations in the study design and execution, the representativeness of the population that was intended to be sampled); and (6) quality level (all the studies show a moderate quality level). In this analysis, certainty is classified into four categories: high, moderate, low and very low. The high quality level shows high coincidence between the real effect and the estimated one; the moderate level may show a possibility of a gap between the estimated and the actual effect; the low quality level shows limited confidence in the estimate of the effect; and finally, the very low quality level shows very little coincidence between the actual effect and the estimated effect, with the actual effect being very different from the estimated effect. It should be added that randomized clinical trials are generally of high quality. In contrast, case studies, cohort studies and observational studies, among others, tend to have a low level of quality (see Appendix B).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of the Studies

The main characteristics of the studies included are displayed in Table 1. All studies were exploratory and comparative studies and used a non-probabilistic (convenience) sampling method. Most of the studies (10 out of 16 studies) were conducted in Europe [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Moreover, three were conducted entirely in the USA [45,46,47] and three were carried out jointly in the USA and Germany [48,49,50].

Table 1.

Characteristics of individual studies.

The studies’ sample sizes ranged from 29 participants [44] to 283 participants [49], with ages ranging approximately from 26.82 (SD = 9.28) to 44.86 years old (SD = 9.26). The participants were selected mainly from penitentiary centers (12 of the 16 items), social integration programs, outpatient or inpatient populations, online public forums, newspaper advertisements and e-mails. They were divided into pedophile men who had and had not committed child sexual abuse (or SO/NSO = sexual offender/non-sexual offender), non-pedophile men who had committed child sexual abuse and a control group of non-pedophile men who had not committed sexual abuse.

Most of the studies (14 of the 16 studies) analyzed cognitive constructs related to executive functions: inhibition or inhibitory control, planning, attention, or attentional control, working memory, processing fluency and speed, abstraction and abstract language, cognitive empathy, resistance to interference and cognitive flexibility. On the other hand, 2 out of the 16 studies analyzed neuroanatomical constructs related to executive functions, such as grey and white matter, brain surface area and laterality [48,49].

A wide variety of instruments were used to evaluate cognitive constructs. The most commonly used instruments were basic and functional magnetic resonance imaging (7 of the 16 studies), which is useful for creating images (static and moving) of the cervical tissue; the electroencephalogram [38], which obtains a pattern of the electrical activity of the brain; the Go/No-Go test (4 of 16 studies), which is mainly used to measure the capacity to maintain selective attention and inhibitory response control [51]; fractional anisotropy of white matter [49], a technique useful in diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) that quantifies the diffusion (or distribution of molecules across a concentration gradient) of water molecules in different brain tissues, specifically, in the white matter [52]; and finally, psychological tests or scales such as the WAIS-III (5 of 16 studies), among others, which measure cognitive abilities such as intelligence, attention and memory.

3.2. Neurocognitive and Neuroanatomical Alterations

Below are the main findings divided into two sections: neurocognitive or executive function alterations, and neuroanatomical alterations or brain structure changes (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Main neurocognitive and neuroanatomical findings of the studies.

3.2.1. Neurocognitive Alterations

Evidence of this type of alteration was found specifically for attention control and interference in the pedophile population who had committed child sexual abuse. The findings showed a decrease in these capacities, due to abnormality and reduced brain activity in areas such as the superior parietal lobe and supramarginal gyrus [35,39,43,44].

Other relevant evidence is the inhibition of response or behavior in the pedophile population who had committed sexual abuse [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,44,45,48,49,50]. Both pedophiles and non-pedophiles who had committed sexual abuse of minors showed a lower inhibition of response and behavior. The brain areas with less activity that reinforced these findings are the left lower amygdala of the temporal cortex [36], the dorsal–medial prefrontal cortex [36,49], the left upper frontal cortex, the left caudal posterior cingulate cortex and the frontoparietal control network [37]. There was also a decrease in connectivity between amygdala–orbitofrontal cortex interaction [36] and the orbitofrontal cortex itself [40]. In contrast, hyperactivation in the left superior parietal lobe and precentral supramarginal gyrus [44] was seen in pedophiles who had committed sexual abuse.

On the other hand, pedophiles who had not committed sexual abuse of minors showed greater self-control and self-regulation [35,37], lower activation in the left and forehead region of the temporal upper gyrus and greater activation in the left nucleus accumbens [42] than pedophiles who had committed sexual abuse of minors.

The caudal and rostral part of the nucleus accumbens was also affected in the pedophile population that had committed sexual abuse [36,41,42], along with a visible reduction in gray matter. In contrast, in the left nucleus accumbens of pedophilic individuals who had not committed sexual abuse, an increase in activation could be observed [42].

In addition, pedophilic individuals who had committed sexual abuse showed greater cognitive flexibility (set-shifting) and perseverance [40,50] than non-pedophilic individuals who had committed sexual abuse. The latter also showed less capacity for the strategic use of working memory. In contrast, pedophilic individuals who had not committed sexual abuse exhibited less cognitive distortion, took fewer risks and were more prone to interference [39]. In spite of this, compared to the control group, pedophiles are characterized by having less awareness of error (related to risk assumption) [44].

Finally, learning deficiencies were found in pedophiles and non-pedophiles who had committed sexual abuse, as well as lower performance in processing speed (slowed visuomotor integration) in pedophiles (SO) and lower semantic performance in non-pedophiles (with SO) [46,47]. In non-pedophile sexual abusers, a greater display of impulsivity appeared [46].

3.2.2. Neuroanatomical Alterations

Anatomically, a reduction in grey matter could be observed in pedophilic individuals who had committed child sexual abuse. The areas in which these reductions could be observed included the bilateral frontal lobe (including the premotor area, orbitofrontal cortex, frontal pole, inferior frontal junction, and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex), the parietal lobe (including the postcentral gyrus and medial precuneus), the temporal lobe (specifically in the inferior temporal gyrus, fusiform and parahippocampal gyrus) and the occipital lobe [41,43,48]. There was also a significant reduction in grey matter in the bilateral basal ganglia, bilateral cerebellum, bilateral medial cingulate and part of the hippocampus [48]. On the other hand, evidence was found of a reduction in white matter that appeared in the inferior surface area of the left prefrontal cortex and the right upper frontal cortex of pedophilic individuals who had committed child sexual abuse [49].

4. Discussion

The aim of the present systematic review was to find neurocognitive and neuroanatomical evidence underlying executive functions in pedophilic individuals including both those who have committed sexual abuse and those who have not, as well as in non-pedophilic individuals, again, including both those who have and those who have not committed sexual abuse. This study is relevant in that it can assist in determining the neurobiological alterations of executive functions in child sexual abusers and whether this phenomenon could be related to pedophilia. It should be added that the results should not be systematized, since the evaluation using the GRADE methodology shows evidence of a moderate degree of quality in the individual studies, so the results may represent an approach to an understanding of the phenomenon but not a strict conclusion.

Nevertheless, we discuss those approaches that we have been able to observe.

Until now, the scientific literature has shown that the phenomenon of pedophilia is a risk factor for sexual abuse. In fact, several studies have already hinted at causes associated with frontal and temporal neurocognitive impairments in pedophilic individuals [13,14,15,16,17,21]. What have not yet been understood rigorously are the differences in certain characteristics presented by these individuals; i.e., we do not know whether they present psychopathic traits or only paraphilia, or whether they have or have not committed sexual abuse against minors.

The studies have shown significant neurocognitive and neuroanatomical differences between sample groups, specifically between groups of perpetrators of child sexual abuse (see a summary in Table 3 and Table 4). The literature shows that pedophiles who commit child sexual abuse suffer alterations in attentional and interference control, an alteration that can be explained by a decrease in neuronal activity in the superior parietal lobe and the supramarginal gyrus. These areas are involved in the shift of attention through perceptual domains and in the reception of frontal information involved in this attentional shift [53]. This finding can be interpreted as a difficulty for pedophiles who commit sexual abuse in diverting their focal attention from the stimuli that represent their desire [43,44]. Other interpretations could include a difficulty in diverting attention from situations that predispose individuals to abuse or impulsivity (due to its relationship with the frontal lobe). Moreover, pedophiles who have committed sexual abuse show lower performance in processing speed [46,47]. This fact may be linked to a problem in neurodevelopment related to psychopathy.

Table 3.

Main neurocognitive differences between groups.

Table 4.

Main neuroanatomical differences between groups.

One of the main findings regards response or behavioral inhibition in samples of individuals who have committed child sexual abuse, whether or not they were pedophilic individuals [35,36,37,38,39,40,41,44,45,48,49,50]. These findings include hypoactivation found in frontal brain structures [36,37,40,49]. We highlight orbitofrontal foreshortening and its interaction with the amygdala, since this decreased activity is reflected in difficulties in the processing and regulation of emotional content, including aspects such as morality and associations with stimulus reinforcement [36]. Moreover, the alteration in the amygdala corresponds to the findings of previous studies, in which considerable impairment in this structure was found in populations presenting with pedophilia [12,19].

The decrease can be interpreted as a risk factor for engaging in behaviors that require deeper aspects of morality and strong self-regulation of reinforcement, such as the sexual abuse or assault of minors. Moreover, it is related to reward processing and how rewards compensate for the value of punishment [54]. This fact may imply that sexually abusive behavior has a greater benefit than the cost of punishment for committing the action, which would result in biologically justified addictive behavior. It is also worth highlighting superior frontal foreshortening, which, in pedophiles who have committed sexual abuse, shows an important decrease, reflected in a limitation in working memory (essential for response inhibition) [37].

Furthermore, the alteration in the connection between the foreshortened temporal lobe and the left inferior amygdala is also reflected in a disruption of the functional integration of inhibitory regions. This finding could be another risk factor contributing to disinhibition in child sex offenders [36].

Other alterations observed include foreshortened parietal and temporal lobes [36,37,41,42,43,44,48,49]. Specifically, an atrophied or foreshortened parietal lobe [37] indicates a differentiation between offending and non-offending pedophiles. The non-offending pedophiles showed greater inhibitory control, which can be explained by taking into account the apparent normality of their frontal cortex and other structures involved, or by a greater capacity for elaborated self-control (bearing in mind that this sample was already undergoing therapeutic intervention). This evidence would support the motivation–facilitation theory [5,20], which determined that strong behavioral inhibition could control the strong motivation for sexually assaulting a victim. This group also showed greater self-referential processing [55]. In contrast, the offending pedophiles showed less inhibitory control due to decreased activity in parietal structures. Posterior cingulate foreshortening is related to conscientiousness, episodic memory, self-reference, and reactive deactivation when attention is directed outward [37]. Behavioral disinhibition is associated with a more deliberate response style, which could be explained by a lack of awareness of the immoral nature of the act or a strong need to obtain reinforcement. This explanation does not apply to non-offending pedophiles, as this group is characterized by strong behavioral inhibition due to their awareness of the immoral nature and the taboo connotation of their paraphilia. It is also possible that non-offending pedophiles, who do not present frontal disturbances, have greater self-control due to their conscientiousness of social repercussions [45] or due to their attentional control, which could help them to avoid all stimuli and risk factors [35].

As a first conclusion, it can be said that behavioral inhibition is independent of pedophilia and dependent on criminal sexual behavior. This is understandable given the impulsive nature of these types of offenders, as stated in “frontal lobe theory” [13,14,15,16,17].

Another finding is related to the reduction in white and grey matter [41,48,49]. This finding shows that certain areas (basal ganglia and cerebellum) form tank circuits with cortical structures that influence social cognition processes. Offending pedophiles showed an alteration in this area, in contrast to non-offending pedophiles [48], and, moreover, showed higher error-related positivity. This evidence, in contrast to other studies [56], indicates that white and gray matter alterations are associated with the criminal act and not with pedophilia, as found in previous studies [57]. Offending pedophiles also exhibited a reduction in grey matter in the prefrontal cortex, the nucleus accumbens and the temporal lobe that could explain the lack of affective empathic skills and inhibition of sex-related behavior [41], as stated in the “temporal lobe theory” [21]. Thus, there is further evidence to support the possibility that the non-offending pedophile sample’s ability of self-control allows them to have a greater awareness of the consequences of their actions.

Some studies have shown peculiarities in both the pedophilic and non-pedophilic sexual offender populations, such as a deficit in verbal memory performance [40]. This impairment, related to diminished verbal ability, is associated with higher levels of abuse due to the direct relationship it maintains with an inability to verbally mediate interpersonal conflicts [58]. According to these data, it can be inferred that child sexual offenders, regardless of whether or not they are pedophiles, are characterized by a framework of aggressiveness. Moreover, there is greater abstract reasoning in offenders (with and without pedophilia), a fact that may indicate the need for problem solving and the planning of their behavior [45].

Other evidence indirectly related to executive functions has been found and should be discussed before we conclude. In the pedophilic sample who had committed sexual abuse, we found a decrease in activity in the nucleus accumbens [36,41,42] in contrast to the non-offending pedophilic population. This decrease is related to an evaluation of emotional response and the prominence of emotional and motivational information about oneself and others, and is also involved in the initiation of goal-directed behavior and conflict control (moral and emotional mediation). Therefore, it could be said that these altered functions may also be behind sexual abuse.

4.1. Limitations and Future Research

Firstly, there was a limitation in the incorporation of articles that, in our first review of the summaries, appeared to meet all the inclusion criteria. Upon being analyzed in greater detail, they were excluded for not presenting sufficient information or for presenting unclear information regarding relationships with executive functions. This resulted in a greater time cost and a final review with fewer studies included. Moreover, most of the studies included were carried out in Europe; therefore, the conclusions inferred may not be significant in other populations.

Secondly, the type of sampling used was non-probabilistic for convenience, a sample type that does not guarantee the generalizability of the results, as stated in the objectives of this study. In addition, there was no homogeneous sample included in the studies. The same number of pedophile and non-pedophile samples were not obtained, regardless of whether they had committed child sexual abuse or not. This limitation is due to the difficulty in finding pedophiles who are not residing in rehabilitation programs or in clinical or penitentiary institutions. It is difficult for individuals in these condition to openly reveal their inclinations and, furthermore, to agree to participatein studies on their condition. Moreover, it is difficult to find a sample that has committed child sexual abuse and yet has not been deprived of its liberty, residing instead either in prisons or in clinical and reintegration centers. This could be a risk factor for bias in the performance of the tests or in the results obtained, since executive functions can be altered in long periods of liberty deprivation [59]. Samples that have received psychological treatment can also generate a certain bias, in comparison with other individuals with the same condition who have not received prior treatment. Furthermore, the differences between offending and non-offending pedophiles are not clear, as they may be influenced by social disaffection. However, it is also true that the variety in the sample has been able to resolve this uncertainty by producing clear results between the different groups as well as greatly reducing the possible range of social disaffection.

Thirdly, there is difficulty in interpreting the findings due to the fact that the evidence of child sexual abuse included does not differentiate between the types and severity of sexual abuse. The different variables that can complement sexual abuse, such as the violence perpetrated, could help in inferring one psychological profile or another. These variables are not taken into account in this review. Furthermore, the neurocognitive alterations found in child sex offenders and adult sex offenders are not differentiated. This fact could also be discerned in the activation of brain areas underlying executive functions.

As a final limitation of our review, we will add the impossibility of complementing the research with a meta-analysis, due to the lack of homogeneity in the methods and instruments used in each of the individual studies. In addition, the application of the GRADE methodology for the assessment of the risk of bias in individual studies showed evidence of a moderate degree of quality, leaving a gap in the analysis of the internal validity of the methodologies used, which hinders the conclusion of the work and indicates the importance of the use of a more specific questionnaire in the analysis of individual studies for future systematic reviews.

Thus, a first proposal for future research is to compare executive functions between child sex offenders and adult sex offenders in order to rule out the conclusion that the victim’s choice of age is determined by some kind of frontal neurocognitive alteration. In addition to a focus on the alterations in activation, an emphasis on the characteristics and connectivity of neural networks is also recommended.

It is known that there are certain factors that affect predisposition to child sexual abuse, such as the vulnerability and choice of the victim, distinguishing between pedophilia and hebephilia [60], an interest in children and disinterest in adults [61], a lack of social skills of the offender that are necessary to maintain social relationships with adults [3], low self-regulation of inhibition, which would mean low facilitation [5,20], and the predisposition and opportunistic backdrop, such as childcare, although these factors cannot apparently be explained by frontal executive alteration. It would also be advisable to review offenders who share these predisposing factors and see if they differ according to the age of the victim chosen. It is possible to hypothesize that child sexual offenders will have a greater lack of social skills with adults than adult sexual offenders.

Finally, the next alternative would be to compare pedophile child offenders and non-pedophile child offenders more exhaustively in order to assess whether there are alterations in other executive processes, such as planning and modus operandi. Lastly, as previously stated, it is necessary to differentiate between different types of sexual abuse (including more variables that can differentiate between abuse carried out by a pedophile and abuse perpetrated by a non-pedophile).

4.2. Implications for Clinical Practice and Social Policy

The present review therefore aims to improve the search for all those risk factors that predispose an individual to commit sexual abuse against minors. It is important to consider all the possible perspectives of a maladaptive behavioral phenomenon. This means including not only the underlying psychological or psychosocial phenomena, but also all the neurobiological characteristics that may indicate a previous alteration or susceptibility to the behavior. The social and judicial considerations of what these results represent must be taken into account. Our study does not conclude that there are other altered neurocognitive functions in pedophilic individuals apart from alterations in executive functioning. It is only concluded that pedophilia, from the point of view of the neurophysiology that supports behavioral self-control, is not a risk factor in child sexual abuse. It can be concluded that pedophilia is a risk factor in the choice of victim, but only if there is a cognitive predisposition to needing a victim, or if there is an abnormal pattern of sexual arousal caused by alterations in functional connectivity [32]. If there are no new neuroanatomical and neurocognitive findings in the relevant brain areas, pedophilia should not pose any criminal risk, from an executive point of view, in the sample used.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, we cannot answer the initial question with complete certainty, as to whether the findings can differentiate pedophilic and non-pedophilic child sexual offenders. The quality assessment of the primary studies included in this analysis, using the GRADE system, showed that all the studies were of moderate quality, with consistent findings in several exploratory and comparative studies, despite some limitations related to study design and sample representativeness. However, we found that non-offending pedophiles show greater self-control, a greater awareness of the consequences of their actions, greater social and emotional cognition and less risk-taking behavior than those pedophiles who have committed sexual abuse toward children. Offending pedophiles do not differ from offending non-pedophiles in most executive functions, which leads to the conclusion that the neurocognitive alterations present are associated with the criminal act and not with the paraphilia, as concluded in other reviews [10,23]. Therefore, the “frontal lobe” theory [13,14,15,16,17] can be reaffirmed, but only under the condition of samples having committed child sexual abuse.

Such a conclusion shows that the executive frontal structures that are responsible for behavioral control, an awareness or self-reference of one’s own actions, and the act of letting oneself be driven by an impulse or avoiding stimuli (in relation to attention), as well as other processes, are not the ones that can explain why an individual with pedophilia may commit child sexual abuse. This is due to the fact that the functioning or alteration of these structures does not differ significantly from those of other individuals without the presence of paraphilia.

Therefore, it is possible that future studies may take into consideration and possibly find more evidence of the role that pedophilia plays in these type of behaviors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.A.-G. and M.M.-V.; methodology, F.G.-S. and L.B.-R.; validation, Y.A.-G. and M.M.-V.; formal analysis, F.G.-S. and L.B.-R.; investigation, Y.A.-G. and F.G.-S.; resources, M.M.-V.; data curation, Y.A.-G. and L.B.-R.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.A.-G. and L.B.-R.; writing—review and editing, F.G.-S. and M.M.-V.; visualization, Y.A.-G.; supervision, L.B.-R.; project administration, M.M.-V.; funding acquisition, M.M.-V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors are willing to make the data privately available to researchers who request the data.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

Appendix A

Table A1.

PRISMA Protocol Guidelines (2020).

Table A1.

PRISMA Protocol Guidelines (2020).

| Items | Item n. º | Item Location |

|---|---|---|

| Title. Identifies the publication as a systematic review | 1 | 1 |

| Abstract. Structured summary | 2 | 2 |

| Introduction. Justification | 3 | 3–6 |

| Introduction. Objectives | 4 | 6 |

| Methods. Eligibility criteria | 5 | 7 |

| Methods. Sources of information | 6 | 7 |

| Methods. Research strategy | 7 | 8–9 |

| Methods. Study selection process | 8 | 8–9 |

| Methods. Data extraction process | 9 | 9–10/34 |

| Methods. List of data | 10 a* | 10 |

| Methods. List of data (variables) | 10 b* | 10 |

| Methods. Bias ratio in individual studies | 11 | 10 |

| Methods. Measures of the effect | 12 | - |

| Methods. Results synthesis (selection criteria) | 13 a* | 10 |

| Methods. Results synthesis (required method) | 13 b* | 10 |

| Methods. Results synthesis (presentation method) | 13 c* | 9–10 |

| Methods. Results synthesis (justification) | 13 d* | 9–10 |

| Methods. Results synthesis (heterogeneity) | 13 e* | 10 |

| Methods. Results synthesis (robustness) | 13 f* | 10 |

| Methods. Assessment by publication | 14 | 10 |

| Methods. Assessment of the certainty of the evidence | 15 | 10 |

| Results. Selection of the studies (research) | 16 a* | 10–11 |

| Results. Selection of the studies (inclusive) | 16 b* | 10–11 |

| Results. Characteristics of the studies | 17 | 36–39 |

| Results. Individual studies bias ratio | 18 | - |

| Results. Results of individual studies | 19 | 40–42 |

| Results. Results of the synthesis (characteristics) | 20 a* | 12–14 |

| Results. Results of the synthesis (presentation) | 20 b* | 12–14 |

| Results. Results of the synthesis (heterogeneity) | 20 c* | 12–14 |

| Results. Results of the synthesis (robustness) | 20 d* | 12–14 |

| Results. Publication bias | 21 | - |

| Results. Certainty of the evidence | 22 | 34 |

| Discussion. Interpretation of results | 23 a* | 14–19 |

| Discussion. Limitations of the evidence | 23 b* | 19 |

| Discussion. Limitations of the review process | 23 | 19–22 |

| Discussion. Implications and future lines of action | 23 d* | 22 |

| Other information. Registry and protocol (registry) | 24 a* | - |

| Other information. Registry and protocol (access) | 24 b* | - |

| Other information. Registry and protocol (amendment) | 24 c* | - |

| Other information. Funding | 25 | 23 |

| Other information. Conflict of interest | 26 | 23 |

| Availability of data, codes and other materials | 27 | 23 |

Note: Page et al., 2021 [29]. * Items a–f are subsections of each item.

Appendix B

Table A2.

Evidence analysis—GRADE system.

Table A2.

Evidence analysis—GRADE system.

| Quality Level | Study Design | Directness | Consistence | Precision | Risk of Bias | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [45] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [35] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [36] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [37] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [48] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [49] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [50] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [38] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [39] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [40] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [41] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [42] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [46] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [47] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [43] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

| [44] | Moderate | * | Mod. | High | Mod. | Mod. |

Note: The studies have been analyzed according to methodology characteristics. Mod = Moderate; * all investigations were exploratory and comparative studies and used a non-probabilistic (convenience) sampling method.

References

- Quintero, D.M. ¿Las parafilias, un paradigma o un problema de salud pública? Salud Arte Cuid. 2023, 16, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, J. DSM-5® Guía Para el Diagnóstico Clínico; Editorial El Manual Moderno: Ciudad De León, Gto, Mexico, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Seto, M.C. Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children: Theory, Assessment, and Intervention; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.C. Pedophilia. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2009, 5, 391–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seto, M.C. Defining pedophilia. In Pedophilia and Sexual Offending Against Children: Theory, Assessment, and Intervention; Seto, M.C., Ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2018; pp. 9–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkelhor, D. Child Sexual Abuse: New Theory and Research; Free Press: New York, NY, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, A. Análisis Documental del Perfil del Abusador Sexual Infantil. Tesis de Grado Universidad de Antioquia. 2018. Available online: https://repository.ucc.edu.co/bitstream/20.500.12494/7300/1/2019_abusador_sexual_caracteristicas.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2022).

- Kruger, T.H.; Schiffer, B. Neurocognitive and personality factors in homo- and heterosexual pedophiles and controls. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 1650–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyal, C.C.; Beaulieu-Plante, J.; de Chantérac, A. The neuropsychology of sex offenders: A meta-analysis. Sex. Abus. 2014, 26, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillien, T.; Brazil, I.A.; Sabbe, B.; Goethals, K. Personality features of sexual offenders who committed offences against children. J. Sex. Aggress. 2023, 29, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strassberg, D.S.; Eastvold, A.; Kenney, J.W.; Suchy, Y. Psychopathy among pedophilic and nonpedophilic child molesters. Child Abus. Negl. 2012, 36, 379–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohnke, S.; Müller, S.; Amelung, T.; Krüger, T.H.; Ponseti, J.; Schiffer, B.; Walter, M.; Beier, K.B.; Walter, H. Brain alterations in pedophilia: A critical review. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 122, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burns, J.M.; Swerdlow, R.H. Right orbitofrontal tumor with pedophilia symptom and constructional apraxia sign. Arch. Neurol. 2003, 60, 437–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flor-Henry, P.; Lang, R.A.; Koles, Z.J.; Frenzel, R.R. Quantitative EEG studies of pedophilia. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 1991, 10, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Graber, B.; Hartmann, K.; Coffman, J.A.; Huey, C.J.; Golden, C.J. Brain damage among mentally disordered sex offenders. J. Forensic Sci. 1982, 27, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffer, B.; Krueger, T.; Paul, T.; de Greiff, A.; Forsting, M.; Leygraf, N.; Schedlowski, M.; Gizewski, E. Brain response to visual sexual stimuli in homosexual pedophiles. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2008, 33, 23–33. [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer, B.; Peschel, T.; Paul, T.; Gizewski, E.; Forsting, M.; Leygraf, N.; Schedlowski, M.; Krueger, T.H. Structural brain abnormalities in the frontostriatal system and cerebellum in pedophilia. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2007, 41, 753–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarpazza, C.; Finos, L.; Genon, S.; Masiero, L.; Bortolato, E.; Cavaliere, C.; Pezzaioli, J.; Monaro, M.; Navarin, N.; Battaglia, U.; et al. Idiopathic and acquired pedophilia as two distinct disorders: An insight from neuroimaging. Brain Imaging Behav. 2021, 15, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenbergen, G.; Wittfoth, M.; Frieling, H.; Ponseti, J.; Walter, M.; Walter, H.; Beier, K.M.; Schiffer, B.; Kruger, T.H. The neurobiology and psychology of pedophilia: Recent advances and challenges. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2015, 9, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, M.C. The motivation-facilitation model of sexual offending. Sex. Abus. 2019, 31, 3–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, J.M.; Kabani, N.; Christensen, B.K.; Zipursky, R.B.; Barbaree, H.E.; Dickey, R.; Klassen, P.E.; Mikulis, D.J.; Kuban, M.E.; Blak, T.; et al. Cerebral white matter deficiencies in pedophilic men. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2008, 42, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dillien, T.; Goethals, K.; Sabbe, B.; Brazil, I.A. The neuropsychology of child sexual offending: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 54, 101406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, D.; Rettenberger, M. Neuropsychological functioning in child sexual abusers: A systematic review. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2020, 54, 101405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerwinn, H.; Weiß, S.; Tenbergen, G.; Amelung, T.; Födisch, C.; Pohl, A.; Massau, C.; Kneer, J.; Mohnke, S.; Kärgel, C.; et al. Clinical characteristics associated with pedophilia and child sex offending–Differentiating sexual preference from offence status. Eur. Psychiatry 2018, 51, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, E.H.; Bopp, L.L.; Rosenfeld, B. Neuropsychological Functioning in Sexual Offenders With and Without Pedophilic Disorder. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2024, 53, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storch, M.; Kanthack, M.; Amelung, T.; Beier, K.M.; Krueger, T.H.; Sinke, C.; Schoenknecht, P. Hypothalamic volume in pedophilia with or without child sexual offense. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2023, 273, 1295–1306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cock, M.R.; Matute, E.; Jurado, M.B. Las funciones ejecutivas a través de la vida. Rev. Neuropsicol. Neuropsiquiatría Neurocienc. 2008, 8, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, M.R.T.; Coelho, C.; Turkstra, L.; Ylvisaker, M.; Moore Sohlberg, M.; Yorkston, K.; Chiou, H.H.; Kan, P.F. Intervention for executive functions after traumatic brain injury: A systematic review, meta-analysis and clinical recommendations. Neuropsychol. Rehabil. 2008, 18, 257–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaration PRISMA 2020: An updated guideline for systematic review publication. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, C.M.D.C.; Pimenta, C.A.D.M.; Nobre, M.R.C. The PICO strategy for the research question construction and evidence search. Rev. Lat. Am. Enferm. 2007, 15, 508–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fonteille, V.; Cazala, F.; Moulier, V.; Stoléru, S. Pedophilia: Contribution of neurology and neuroimaging techniques. L’encephale 2012, 38, 496–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poeppl, T.B.; Eickhoff, S.B.; Fox, P.T.; Laird, A.R.; Rupprecht, R.; Langguth, B.; Bzdok, D. Connectivity and functional profiling of abnormal brain structures in pedophilia. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015, 36, 2374–2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguayo-Albasini, J.L.; Flores-Pastor, B.; Soria-Aledo, V. Sistema GRADE: Clasificación de la calidad de la evidencia y graduación de la fuerza de la recomendación. Cirugía Española 2014, 92, 82–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schünemann, H.; Brożek, J.; Guyatt, G.; Oxman, A. GRADE Handbook for Grading Quality of Evidence and Strength of Recommendations. The GRADE Working Group. 2013. Available online: https://gdt.gradepro.org/app/handbook/handbook.html (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Jordan, K.; Fromberger, P.; Müller, I.; Wernicke, M.; Stolpmann, G.; Müller, J.L. Sexual interest and sexual self-control in men with self-reported sexual interest in children—A first eye tracking study. J. Psychiatr. 2018, 96, 138–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kärgel, C.; Massau, C.; Weiß, S.; Walter, M.; Kruger, T.H.; Schiffer, B. Diminished functional connectivity on the road to child sexual abuse in pedophilia. J. Sex. Med. 2015, 12, 783–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kärgel, C.; Massau, C.; Weiß, S.; Walter, M.; Borchardt, V.; Krueger, T.H.; Schiffer, B. Evidence for superior neurobiological and behavioral inhibitory control abilities in non-offending as compared to offending pedophiles. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2017, 38, 1092–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosburg, T.; Deuring, G.; Boillat, C.; Lemoine, P.; Falkenstein, M.; Graf, M.; Mager, R. Inhibition and attentional control in pedophilic child sexual offenders– An event-related potential study. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2018, 129, 1990–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosburg, T.; Pflueger, M.O.; Mokros, A.; Boillat, C.; Deuring, G.; Spielmann, T.; Graf, M. Indirect and neuropsychological indicators of pedophilia. Sex. Abus. 2021, 33, 579–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, B.; Vonlaufen, C. Executive dysfunctions in pedophilic and nonpedophilic child molesters. J. Sex. Med. 2011, 8, 1975–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffer, B.; Amelung, T.; Pohl, A.; Kaergel, C.; Tenbergen, G.; Gerwinn, H.; Mohnke, S.; Massau, C.; Matthias, W.; Weiss, S.; et al. Gray matter anomalies in pedophiles with and without a history of child sexual offending. Transl. Psychiatry 2017, 7, e1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuler, M.; Mohnke, S.; Amelung, T.; Beier, K.M.; Walter, M.; Ponseti, J.; Schiffer, B.; Tillmann, H.C.; Walter, H. Neural processing associated with cognitive empathy in pedophilia and child sexual offending. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2022, 17, 712–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczypiński, J.; Wypych, M.; Krasowska, A.; Wiśniewski, P.; Kopera, M.; Suszek, H.; Wojnar, M. Abnormal behavioral and neural responses in the right dorsolateral prefrontal cortex during emotional interference for cognitive control in pedophilic sex offenders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2022, 151, 131–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weidacker, K.; Kärgel, C.; Massau, C.; Krueger, T.H.; Walter, M.; Ponseti, J.; Walter, H.; Schiffer, B. Interference inhibition in offending and non-offending pedophiles: A preliminary event-related fMRI study. Neuropsychologia 2022, 173, 108301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastvold, A.; Suchy, Y.; Strassberg, D. Executive function profiles of pedophilic and nonpedophilic child molesters. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2011, 17, 295–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchy, Y.; Whittaker, J.W.; Strassberg, D.S.; Eastvold, A. Neurocognitive differences between pedophilic and nonpedophilic child molesters. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2009, 15, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y.; Eastvold, A.D.; Strassberg, D.S.; Franchow, E.I. Understanding processing speed weaknesses among pedophilic child molesters: Response style vs. Neuropathology. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2014, 123, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, M.S.; Jordan, K.; Kiehl, K.A.; Nyalakanti, P.K.; Harenski, C.L.; Müller, J.L. Widespread and interrelated gray matter reductions in child sexual offenders with and without pedophilia: Evidence from a multivariate structural MRI study. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2021, 75, 331–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lett, T.A.; Mohnke, S.; Amelung, T.; Brandl, E.J.; Schiltz, K.; Pohl, A.; Gerwinn, H.; Kärgel, C.; Massau, C.; Tenbergen, G.; et al. Multimodal neuroimaging measures and intelligence influence pedophile child sexual offense behavior. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018, 28, 818–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massau, C.; Tenbergen, G.; Kärgel, C.; Weiß, S.; Gerwinn, H.; Pohl, A.; Amelung, T.; Mohnke, S.; Kneer, J.; Wittfoth, M.; et al. Executive functioning in pedophilia and child sexual offending. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2017, 23, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez, P.; Ratcliff, R.; Perea, M. A model of the go/no-go task. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2007, 136, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Iglesia-Vayá, M.; Molina-Mateo, J.; Escarti-Fabra, M.J.; Martí-Bonmatí, L.; Robles, M.; Meneu, T.; Aguilar, E.J.; Sanjuán, J. Técnicas de análisis de posproceso en resonancia magnética para el estudio de la conectividad cerebral. Radiología 2011, 53, 236–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenberg, A.S.; Esterman, M.; Wilson, D.; Serences, J.T.; Yantis, S. Control of spatial and feature-based attention in frontoparietal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2010, 30, 14330–14339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kringelbach, M.L.; Rolls, E.T. The functional neuroanatomy of the human orbitofrontal cortex: Evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychology. Prog. Neurobiol. 2004, 72, 341–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buckner, R.L.; Andrews-Hanna, J.R.; Schacter, D.L. The Brain’s Default Network: Anatomy, Function, and Relevance to Disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1124, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popovic, D.; Wertz, M.; Geisler, C.; Kaufmann, J.; Lähteenvuo, M.; Lieslehto, J.; Witzel, J.; Bogerts, B.; Walter, M.; Falkai, P.; et al. Patterns of risk—Using machine learning and structural neuroimaging to identify pedophilic offenders. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1001085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cantor, J.; Blanchard, R. White matter volumes in pedophiles, hebephiles, and teleiophiles. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2012, 41, 749–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, R.L.; Liossi, D.; Psych, C. Neuropsychological and neurobehavioral correlates of aggression following traumatic brain injury. J. Neuropsychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2006, 18, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lapornik, R.; Lehofer, M.; Moser, M.; Pump, G.; Egner, S.; Posch, C.; Hildebrandt, G.; Zapotoczky, H.G. Long-term imprisonment leads to cognitive impairment. Forensic Sci. Int. 1996, 82, 121–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stephens, S.; Seto, M.C. Hebephilic sexual offending. In Sexual Offending: Predisposing Antecedents, Assessments and Management; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippers, E.E.; Smid, W.J.; Hoogsteder, L.M.; Planting, C.H.; de Vogel, V. Pedophilia is associated with lower sexual interest in adults: Meta-analyses and a systematic review with men who had sexually offended against children. Aggress. Violent Behav. 2023, 69, 101813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).