Abstract

Building individualization is a critical preprocessing step for refined applications of oblique photogrammetry 3D models, yet existing semantic segmentation methods encounter accuracy bottlenecks when applied to ultra-high-resolution orthophotos. To overcome this challenge, this study constructs an automated technical framework following a workflow from orthophoto generation to high-precision semantic segmentation, and finally to dynamic 3D rendering. The framework comprises three stages: (1) converting the 3D model into a 2D orthophoto to ensure that the extracted building contours can be precisely registered with the original 3D model in space; (2) utilizing the proposed Gated-ASPP High-Resolution Network (GA-HRNet) to extract building contours, enhancing segmentation accuracy by synergizing HRNet’s spatial detail preservation capability with ASPP’s multi-scale context awareness; (3) mapping the extracted 2D vector contours back to the 3D model and achieving interactive building individualization via dynamic rendering technology. Evaluated on a custom-built Hong Kong urban building dataset, GA-HRNet achieved an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 91.25%, an F1-Score of 95.41%, a Precision of 93.31%, and a Recall of 97.70%. Its performance surpassed that of various comparative models, including FCN, U-Net, MBR-HRNet, and others, with an IoU lead of 1.46 to 5.62 percentage points. This method enables precise building extraction and dynamic highlighting within 3D scenes, providing an efficient and reliable technical path for the refined application of large-scale urban oblique photogrammetry models.

1. Introduction

In recent years, with the development of digital twins and smart city technologies, 3D reconstruction based on multi-view optical imaging has gradually become one of the mainstream modeling methods [1,2,3]. Among them, oblique photogrammetry technology is currently the mainstream choice due to its efficiency and automation [4,5,6]. This technology mainly uses Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) equipped with multi-lens sensors to capture images simultaneously from a “one vertical, four oblique” combined angle. By fully capturing high-resolution texture details of both the top and sides of the target, and combining high-precision positioning, multi-view imaging, and dense matching tech, it can efficiently generate realistic 3D models that are highly consistent with the real world [7,8,9,10]. However, these 3D models are essentially just dense 3D meshes with realistic textures, basically presenting a “continuous skin” characteristic in their topological structure. Buildings, trees, and ground are all fused together, lacking clear semantic boundaries and independent geometric instances. This characteristic severely restricts the independent management, attribute editing, and interactive analysis of specific objects in the scene (such as individual buildings), failing to meet the refined needs of downstream applications like smart cities [11]. Therefore, achieving high-precision building individualization for such 3D models generated by multi-view optical systems has become a critical and urgent problem in the field of 3D vision.

Building individualization primarily refers to effectively separating individual buildings from the original model—either visually or physically—to support interactive operations [11,12,13]. Although current individualization methods cover various technical paths like physical segmentation, model reconstruction, and attribute labeling [14,15,16,17,18], they usually need complex geometric calculations or spatial matching. Their final results depend a lot on how accurate the initial contours are, making it hard to balance efficiency and accuracy. To solve this, Xu W et al. [19] proposed a method based on multi-elevation plane sections, providing a new approach for the individualization of oblique photography 3D models. However, this method relies on extracting building contours from multi-elevation plane sections, and its precision and robustness may require further validation when applied to areas with significant building height disparities.

Obviously, the key prerequisite for building individualization is effectively identifying and extracting building regions. However, current technology faces some challenges. First, direct segmentation of buildings within 3D data is typically time-consuming, introduces a large amount of redundant data, and is not conducive to spatial computational analysis [11,14]. Second, using traditional single-view remote sensing images brings inherent projection distortions, meaning the extracted contours are difficult to align geometrically with the multi-view 3D models [20,21,22]. Finally, while converting 3D models into distortion-free digital orthophotos (DOM) for identification and extraction fixes the alignment issue, the ultra-high-resolution characteristic of the resulting orthophotos presents new challenges for segmentation models: On one side, the images are packed with extremely rich details, requiring the model to possess a capability for spatial detail preservation at such an ultra-high resolution. On the other side, the massive scale of the data and block processing strategies often cause the model to lose necessary context due to a limited receptive field, leading to incomplete segmentation or inconsistent results within the same class.

To solve the aforementioned problems, this paper proposes a Gated-ASPP High-Resolution Network (GA-HRNet) designed for the individualization of oblique photogrammetry 3D models. By synergizing the spatial detail representation capability of HRNet with the multi-scale context perception capability of ASPP, this network achieves a deep fusion of spatial precision and semantic consistency, thereby extracting building regions to realize high-precision building individualization of oblique photogrammetry models. Specifically, the main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- Proposed a novel segmentation head named Gated-ASPP (G-ASPP). This module introduces a context-aware gating mechanism into the classic ASPP structure, utilizing ASPP’s own global context information to dynamically and channel-wise recalibrate its multi-scale feature responses, thereby improving boundary delineation accuracy for large-footprint buildings while reducing false positives in complex urban backgrounds.

- Developed the GA-HRNet model. This model combines HRNet’s spatial detail preservation capability with G-ASPP’s dynamic context reasoning capability. It achieved performance superior to multiple existing advanced segmentation models on a building dataset constructed based on publicly available 3D model data of the Kowloon Peninsula, Hong Kong, thereby verifying the effectiveness and superiority of the proposed method.

- Established an end-to-end framework for building individualization from oblique photogrammetry models. The framework integrates orthophoto generation, deep learning-based segmentation, and coordinate-based 3D mapping with interactive visualization, providing a practical solution for large-scale urban 3D model applications that avoids the geometric complexity of direct 3D segmentation.

In summary, by realizing a fully automated workflow from raw 3D models to interactive individualized objects, this study significantly reduces the high costs of traditional manual individualization and addresses the accuracy challenges of building individualization in large-scale 3D urban scenarios. This provides a feasible technical route for the refined and interactive application of large-scale 3D models in fields such as urban planning [23,24] and intelligent security [25,26].

2. Literature Review

Based on Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) architectures, researchers have successively proposed a series of advanced network architectures for building extraction, such as DR-Net [27], PCL–PTD Net [28], EUNet [29], and SFGNet [30]. As shown in Table 1, Liu Y et al. [31] constructed ARC-Net by introducing an end-to-end attention refinement mechanism, which significantly enhanced the discriminative power of feature maps; Shao Z et al.’s BRRNet [32] introduced a residual refinement module, which effectively corrected predicted boundaries; Zhu Q et al.’s MAP-Net [33] utilized multiple parallel attention paths, achieving a deep capture of spatial and semantic information; Moghalles K et al. [34] improved the segmentation performance of the U-Net network by introducing a parallel distance map prediction task, effectively enhancing the smoothness and quality of building segmentation results; Yildirim F.S et al. [35] proposed the FwSVM-Net model by introducing a support vector machine, thereby improving the model’s training efficiency. However, although these methods have made significant progress on specific datasets, they are difficult to apply directly to the ultra-high-resolution orthophotos generated from 3D models. This is mainly because they involve multiple downsampling and upsampling operations. This mechanism, while expanding the receptive field, causes the loss of a large amount of spatial detail information, making the final extracted building contours often not sharp enough to meet the precision requirements for geometric boundaries in individualization.

With the rise of Vision Transformers, using self-attention mechanisms for image segmentation has become a new trend. In the field of remote sensing building extraction, BuildFormer [36] combines convolution with window attention mechanisms to enhance the frequency perception capabilities of features; MSTrans [37] is a multi-scale Transformer architecture that can achieve robust perception of building targets of different sizes; Yilmaz E.O et al. [38] proposed the DeepSwinLite model by designing a multi-scale feature fusion module, effectively improving the model’s computational efficiency and performance. However, applying such Transformer architectures directly to oblique photography individualization tasks presents significant challenges, primarily due to the massive demand for training data. Our preliminary experiments indicate that even state-of-the-art models pre-trained on large-scale datasets (e.g., Mask2Former [39]) exhibit severe convergence difficulties when fine-tuned on the ultra-high-resolution orthophotos used in this study, often resulting in invalid segmentation outputs. This confirms that Transformer architectures heavily rely on ultra-large-scale datasets to learn spatial structural features. However, in the specific domain of building individualization, high-precision pixel-level annotation samples derived from oblique photogrammetry models are extremely scarce and costly to produce. Consequently, under restricted training data conditions, Transformer architectures struggle to converge effectively and are highly prone to overfitting.

Table 1.

Summary of existing building extraction methods and their limitations in the context of this study.

Table 1.

Summary of existing building extraction methods and their limitations in the context of this study.

| Category | Model | Key Mechanism | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN-based Methods | ARC-Net [31] | End-to-end attention refinement mechanism | Enhances discriminative power of feature maps | Involves repeated down-sampling and up-sampling operations, easily leading to spatial information loss. |

| BRRNet [32] | Residual refinement module | Effectively corrects predicted boundaries | ||

| MAP-Net [33] | Multi-parallel attention paths | Deeply captures spatial and semantic information | ||

| Modified U-Net [34] | Parallel distance map prediction | Improves smoothness and quality of segmentation results | ||

| FwSVM-Net [35] | Support Vector Machine (SVM) integration | Improves model training efficiency | ||

| Transformer-based Methods | BuildFormer [36] | Convolution + Window attention mechanism | Enhances frequency perception capability | Massive demand for training data; difficult to converge and prone to overfitting with small sample sizes. |

| MSTrans [37] | Multi-scale Transformer architecture | Robust perception of buildings with different sizes | ||

| DeepSwinLite [38] | Multi-scale feature fusion module | Improves computational efficiency and performance | ||

| Foundation of Proposed Method | HRNet [40] | Parallel multi-resolution subnetworks | Maintains high-resolution representations throughout, reducing spatial information loss | Relatively limited contextual understanding capability. |

| DeepLabV3+ [41] | Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) | Expands receptive field to capture multi-scale context | Prone to spatial information loss and difficult to adapt to complex scale variations in ultra-high-resolution orthophotos. |

Therefore, CNN architectures, with their generalization ability under small sample conditions, become the optimal choice for this study. Among them, HRNet [40] maintains high-resolution representations throughout the network forward propagation process by connecting multi-resolution subnetworks in parallel, fundamentally avoiding the spatial information loss caused by traditional down-sampling. Meanwhile, the Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling (ASPP) module, widely used in the DeepLabV3+ [41] series, can effectively expand the receptive field to capture multi-scale context. Clearly, organically synergizing HRNet’s spatial detail preservation capability with ASPP’s multi-scale semantic perception capability should theoretically satisfy the requirements of building individualization.

3. Materials and Methods

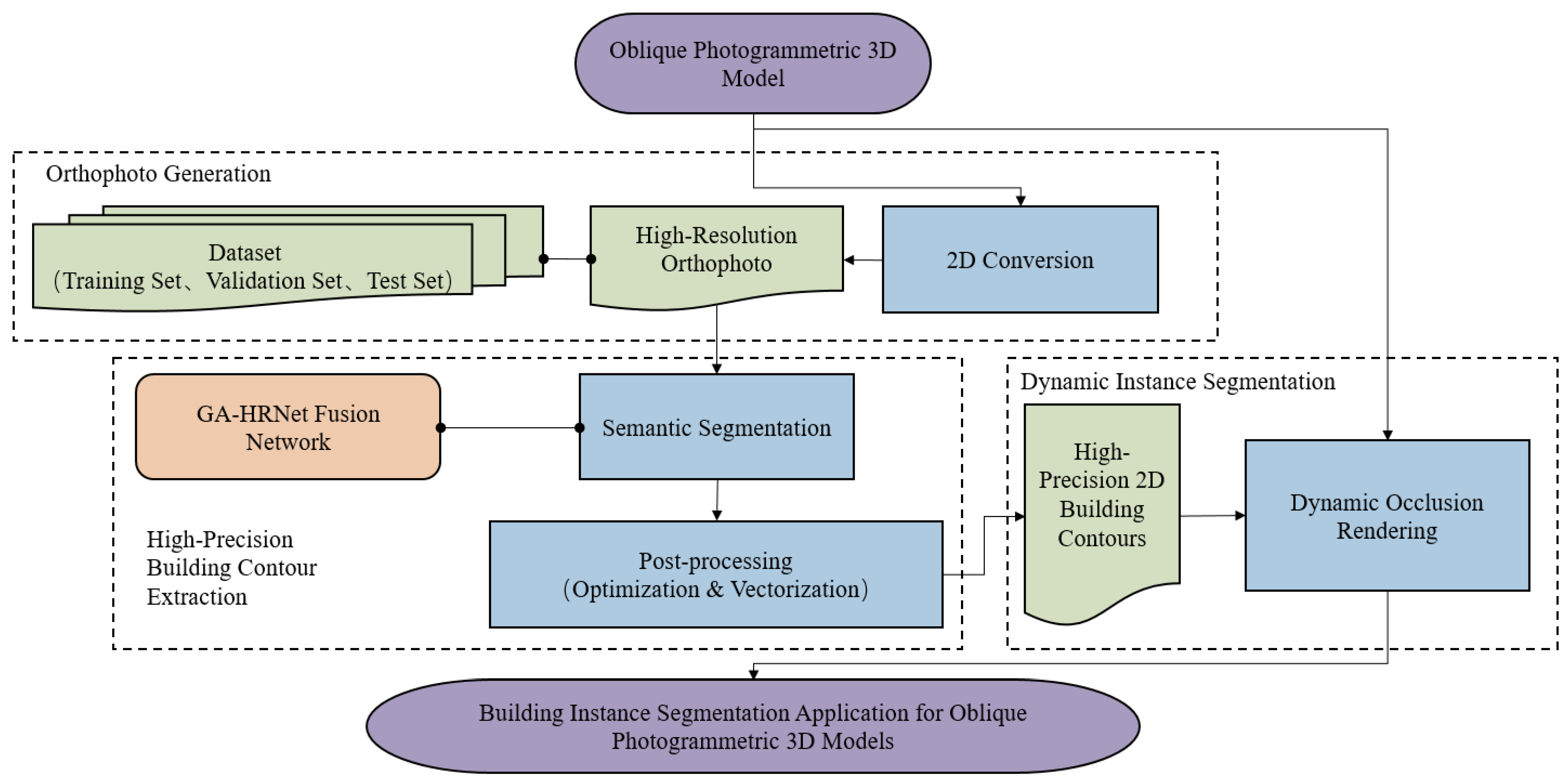

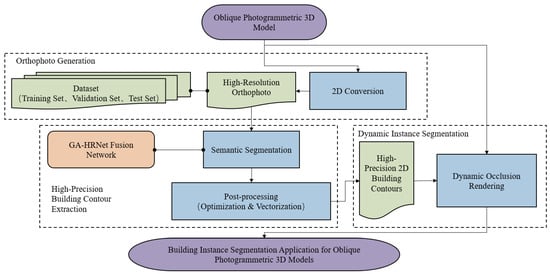

The individualization method proposed in this paper adopts the technical route of “Orthophoto Generation → High-Precision Building Contour Extraction → 3D Dynamic Inclusion Rendering”. The overall framework is shown in Figure 1. This method mainly includes three core stages: orthophoto generation, high-precision contour extraction, and dynamic individualization. First, an orthophoto with geographic coordinates is generated based on the 3D model, and training, validation, and test datasets are constructed. Then, the GA-HRNet network is utilized to perform semantic segmentation on the orthophoto, and 2D building contour polygons are extracted via post-processing. Finally, the 2D contour results are associated back to the original 3D model, realizing the visual individualization effect of the model buildings through dynamic inclusion rendering technology.

Figure 1.

Overall Technical Route. Dashed boxes delineate the three main processing stages. Colors distinguish different functional modules (e.g., orange for the neural network, blue/green for processing steps). Document symbols (with wavy edges) represent data inputs and outputs, while rectangular boxes represent specific processing operations.

3.1. Study Area

The experimental data for this study were derived from the 3D reality model of the Kowloon Peninsula, publicly released by the Hong Kong Planning Department. This model was constructed based on high-resolution aerial oblique photogrammetry images acquired in 2018. As one of the areas with the highest building density and most complex vertical spatial structures globally, the urban landscape of the Kowloon Peninsula provides an ideal testing ground for validating the robustness of segmentation algorithms in extreme environments.

To ensure the diversity and representativeness of the constructed dataset and to prevent potential leakage issues caused by spatial autocorrelation of data, this study carefully selected multiple geographically independent sub-regions within the Kowloon Peninsula for sampling. As shown in Figure 2, these selected areas cover typical complex urban environments characterized by high building density and significant morphological heterogeneity. Specifically, the study area encompasses various building types, including closely packed high-rise residential communities, large-scale industrial plants with complex textures and large footprints, and modern commercial buildings with varied geometric structures.

Figure 2.

A sample area of the experimental data (2018), showcasing a complex urban environment with high building density and significant morphological diversity. Note: The map orientation is North-up.

3.2. Dataset Construction

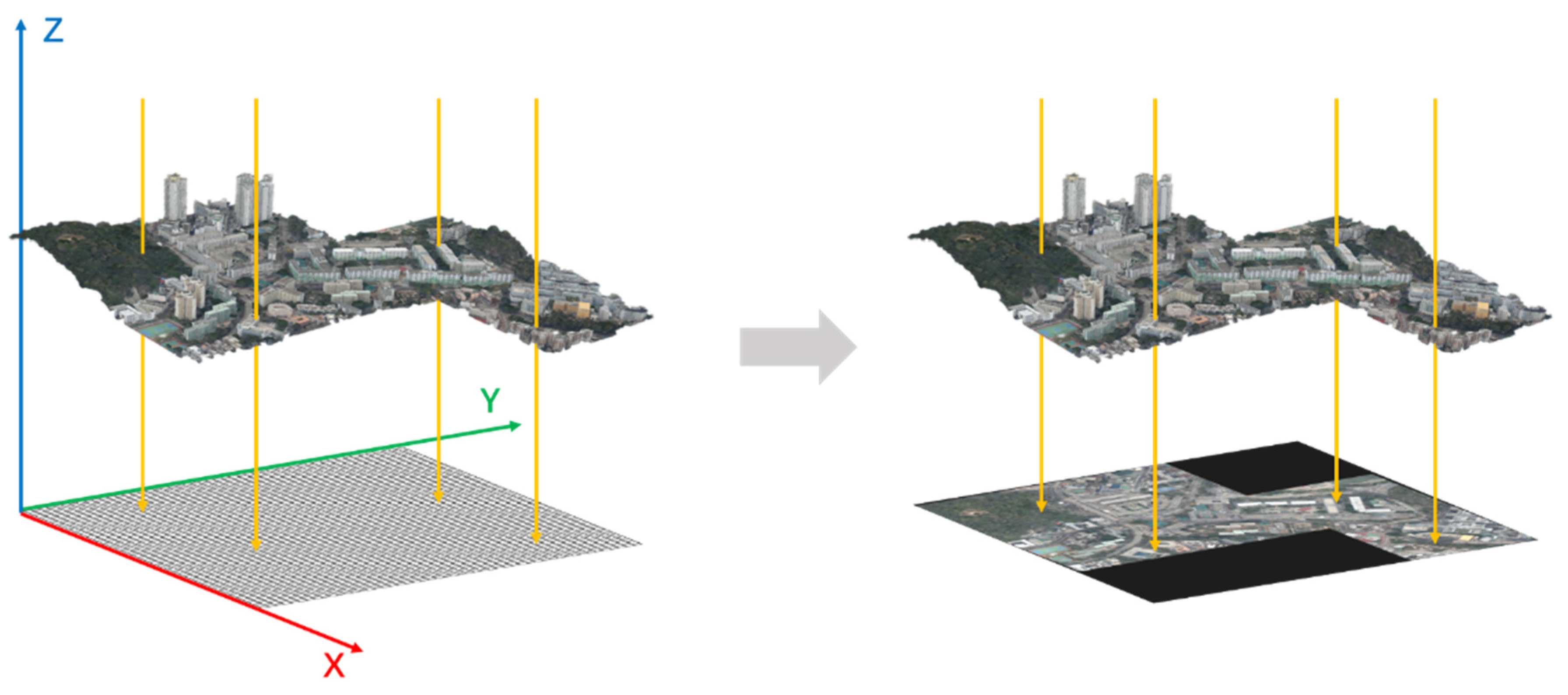

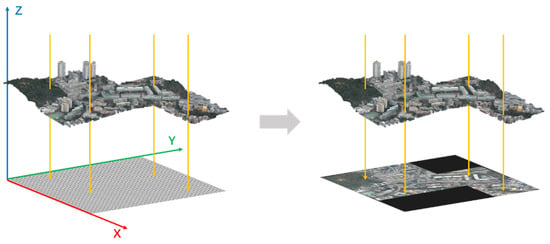

The key prerequisite for the precise individualization of a 3D model is to convert complex spatial information into easily processable 2D data. To this end, this study adopts a method based on orthogonal projection to directly generate a 0.05-m resolution DOM from the oblique photography model [42,43]. As shown in Figure 3, this method first calculates the axis-aligned bounding box of the 3D model to lock the geographic range. Subsequently, an orthogonal projection camera for the scene is constructed within this range. This camera is placed directly above the model’s bounding box with its line of sight strictly perpendicular to the ground plane (Z-axis direction), and the size of its view frustum is set to perfectly cover the entire XY planar extent of the model. Finally, the surface texture colors of the model are projected onto the 2D plane, while areas not covered by the model are filled with black pixels. This process completely eliminates the building geometric distortions caused by viewing angles and terrain that are present in traditional single-view remote sensing images, and ensures that the building contours in the image can be precisely registered with the spatial coordinates of the original 3D model, providing a high-precision data foundation for subsequent building extraction and 3D dynamic rendering.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of orthophoto generation. Note: The yellow arrows indicate the camera line of sight, and the black grid represents the calculated geographic extent. The red, green, and blue arrows represent the X, Y, and Z axes of the spatial coordinates, respectively.

This study implemented a rigorous data annotation and automated quality control process to ensure the high precision and consistency of the ground truth labels. First, based on the 0.05-m ultra-high-resolution orthophotos, building contours were meticulously manually vectorized using ArcGIS Pro software (version 3.0.1). For ambiguous boundaries caused by shadows or texture interference, a “3D-assisted interpretation” strategy was adopted, which involved cross-referencing the geometric structure of the original 3D model to precisely locate the edges. Subsequently, to eliminate geometric logic errors potentially introduced by manual operation, a strict automated topology check was introduced within the software to automatically detect and rectify potential geometric anomalies.

In constructing the experimental dataset suitable for deep learning, apart from setting aside a portion of an independent region as the final test set, the orthophotos and corresponding building labels from the remaining areas were processed into non-overlapping 512 × 512 pixel image patches. This resulted in a dataset containing 2662 pairs of original images and labels for model training and validation. Then, this dataset was partitioned via stratified random sampling based on geographic regions at an 8:2 ratio into a training set comprising 2129 samples and a validation set comprising 533 samples.

3.3. GA-HRNet Network

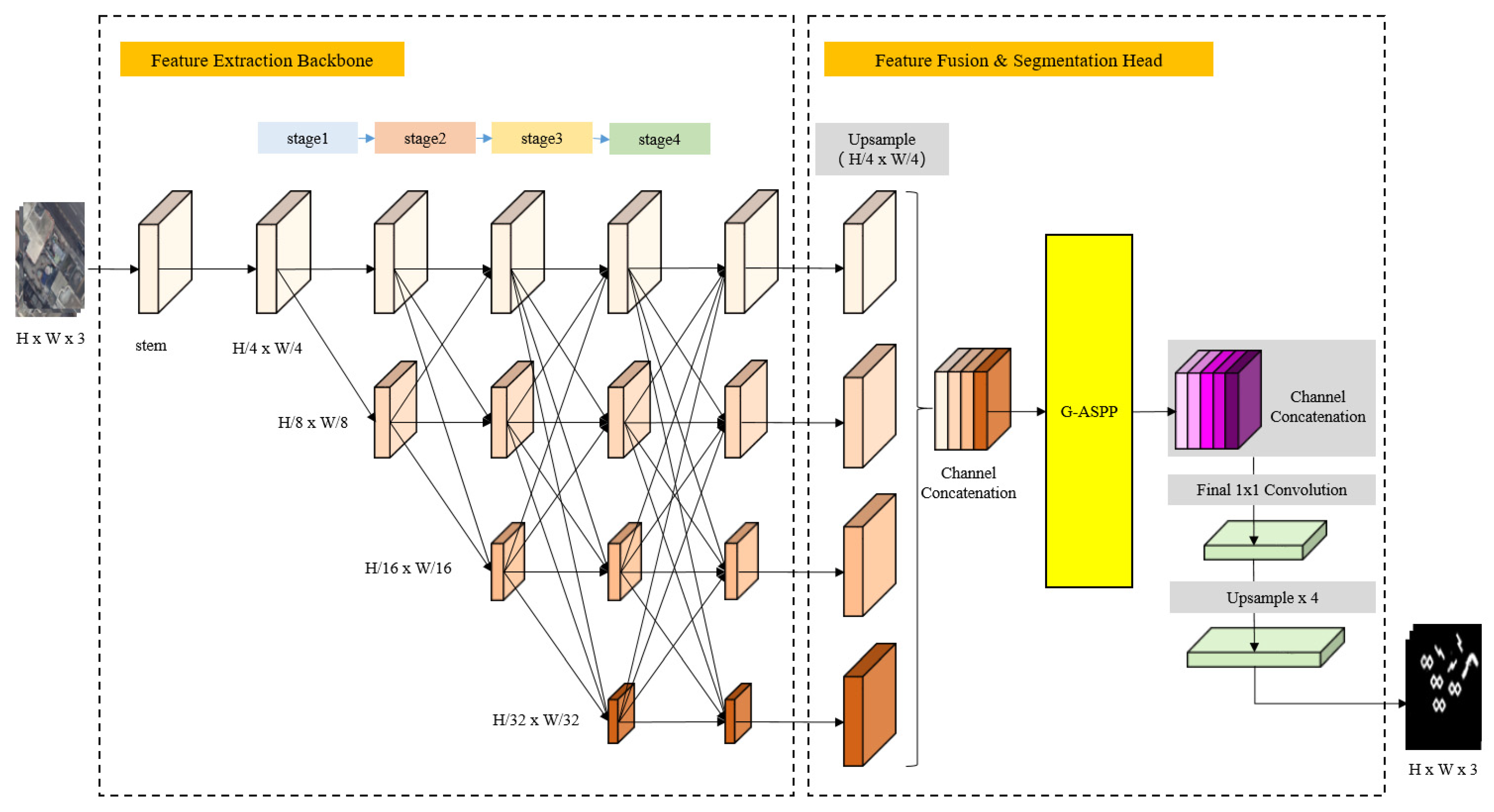

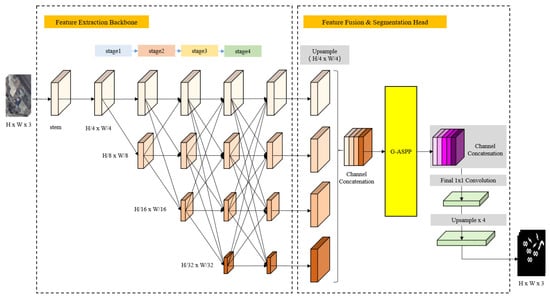

To achieve high-precision extraction of buildings from super-high-resolution orthophotos generated by oblique photography models, this study proposes a Gated-ASPP High-Resolution Network (GA-HRNet). Figure 4 illustrates the overall architecture of GA-HRNet, with specific data flows and component details described as follows:

Figure 4.

GA-HRNet Network Structure. Block size represents spatial resolution (larger blocks indicate higher resolution), while color intensity from light to dark represents increasing channel counts. Crossing lines denote multi-scale fusion operations.

The backbone of GA-HRNet adopts the HRNet-W32 architecture (where W = 32 denotes the base multiplier for the high-resolution channel width). The input image first passes through the illustrated Stem module (consisting of two 3 × 3 convolutions with a stride of 2), reducing the feature map resolution to 1/4 of the original size (i.e., H/4 × W/4) and expanding the channel count to 64. Subsequently, the network progresses through four deepening feature extraction stages (Stage 1 to Stage 4). As shown, the network starts with a single branch and progressively adds lower-resolution branches in parallel as the depth increases, ultimately constructing four parallel feature streams at Stage 4. The resolutions of these four branches are 1/4, 1/8, 1/16, and 1/32 of the input image, respectively, with corresponding channel widths configured as 32, 64, 128, and 256. Between these streams, the crossing lines in the diagram represent repeated multi-scale fusion operations, enabling interaction between features of different resolutions via strided convolutions (down-sampling) and bilinear interpolation (up-sampling). This ensures that the high-resolution branch continuously absorbs deep semantic information while low-resolution branches obtain precise spatial positional calibration.

After deep feature extraction by the backbone, to leverage multi-scale information for precise segmentation, the data flow enters the Feature Fusion & Segmentation Head section shown in the dashed box on the right of Figure 4. First, the feature maps from the three lower-resolution branches (H/8, H/16, H/32) output by HRNet are forcibly up-sampled via bilinear interpolation to match the size of the high-resolution branch (H/4 × W/4). Subsequently, a channel concatenation operation is performed to generate a fused feature map containing both rich details and semantics, with a total channel count accumulating to 480. This feature map is then fed into the G-ASPP module for segmentation.

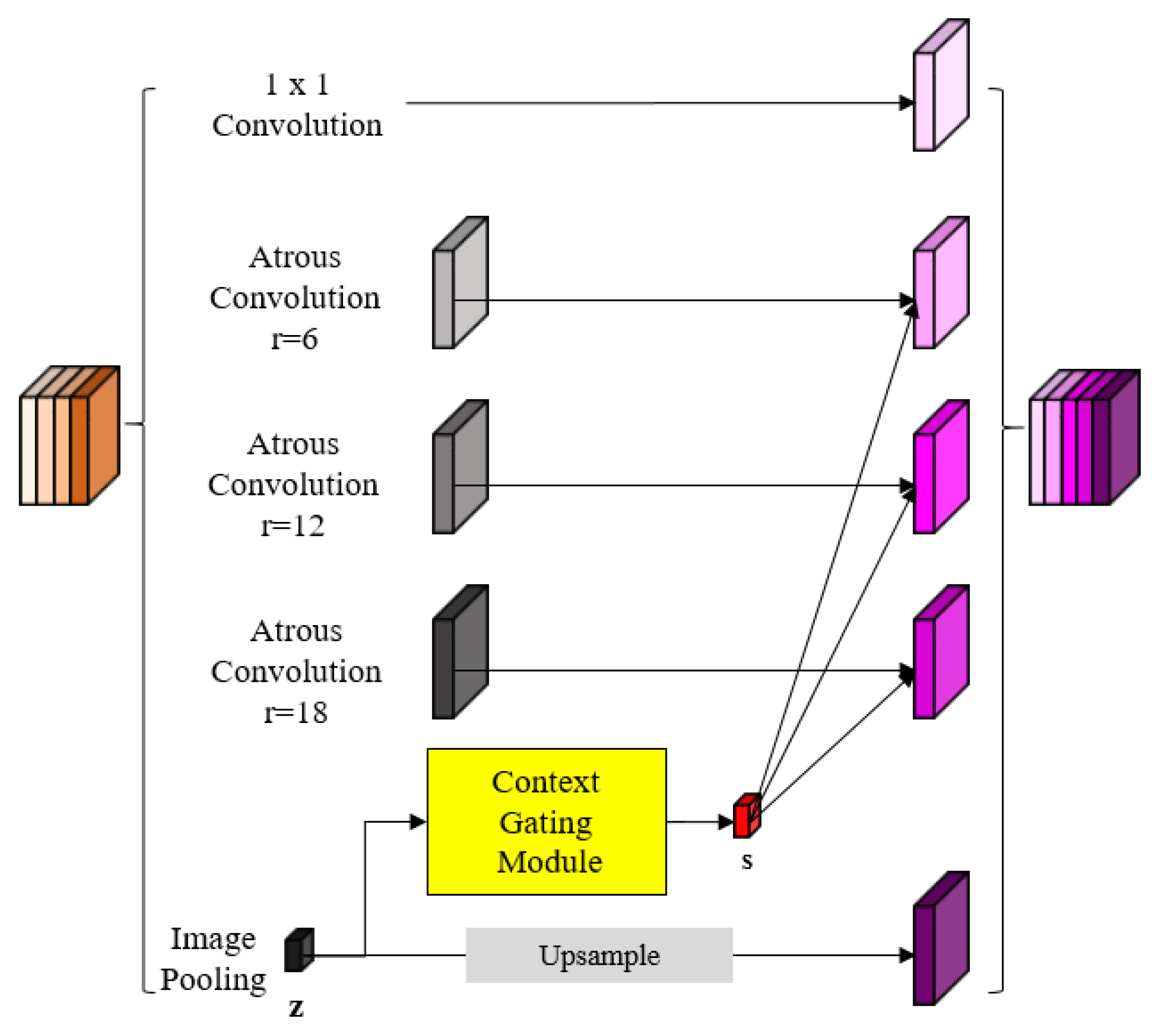

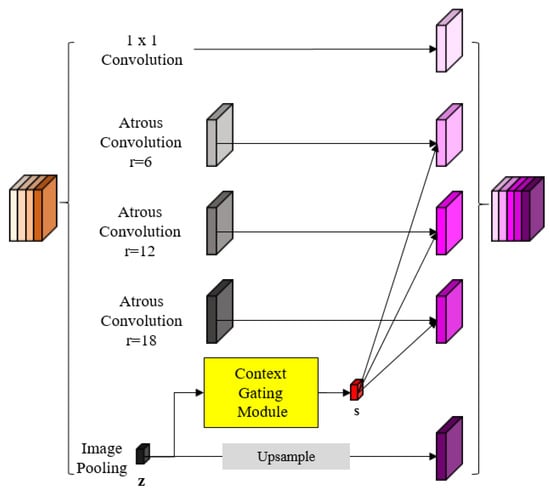

The traditional ASPP module captures multi-scale context through multiple parallel atrous convolution branches, but the information in each branch is independent, lacking a mechanism to dynamically adjust its internal information flow based on the input features. Therefore, this study designed a Gated-ASPP (G-ASPP) module, as shown in Figure 5. This module leverages the global pooling branch of ASPP itself as an information source to construct a context-gated feedback loop that dynamically modulates the other parallel branches. The main workflow consists of three steps:

Figure 5.

G-ASPP Module Structure. Block size corresponds to spatial dimensions. Component colors indicate specific functions: Grey = Atrous Convolutions; Yellow = Context Gating Module; Black (z) = Global context descriptor; Red (s) = Gating signal.

Parallel Feature Extraction and Global Context Encoding: As in original ASPP, the feature map is fed simultaneously into five parallel branches of the G-ASPP: one 1 × 1 convolution branch, three 3 × 3 atrous convolution branches with dilation rates of 6, 12, and 18, respectively, and one image-level global pooling branch. Among these branches, the Image Pooling branch can generate a global context descriptor through global average pooling () and a 1 × 1 convolution, as shown in Equation (1). Simultaneously, the other four branches independently calculate their initial feature maps .

Gating Signal Generation: The global context descriptor is subsequently fed into the bottleneck structure of the Context Gating Module. The module first compresses the channel count to (where the reduction ratio is set to 16 in this study) via a 1 × 1 convolution, followed by ReLU activation, and then expands it back to the original channel dimension. Finally, a Sigmoid function generates the gating signal normalized to the (0, 1) interval, as shown in Equation (2):

where and represent the weights of two 1×1 convolution layers, respectively, is the number of channels processed and output internally by the G-ASPP module, is the reduction ratio, is the ReLU activation function, and is the Sigmoid activation function. The Sigmoid function normalizes each channel value of the gating signal to the (0,1) interval, allowing it to be interpreted as a channel-wise attention weight.

Channel-wise Feature Recalibration: The generated gating signal is used to modulate the output feature maps of the three atrous convolution branches, as shown in Equation (3):

where denotes element-wise multiplication. In this operation, the spatial dimensions of are broadcast to be the same as . Through this feature recalibration process, the model can adaptively enhance feature channels most relevant to the current scene and suppress irrelevant feature channels that may cause interference based on the global context.

During the network training process, this study adopts the Binary Cross Entropy with Logits Loss function as the optimization objective. This function integrates a Sigmoid activation layer and the Binary Cross Entropy Loss (BCELoss) into a single class, ensuring numerical stability while effectively measuring the difference between the predicted probability distribution and the true label distribution. For the pixel-level building extraction task, the total loss is shown in Equation (4):

where is the total number of pixels in the input image patch, represents the true label of pixel for building foreground, 0 for background), is the non-normalized logits value output by the model, and is the Sigmoid activation function, used to map the output to the (0,1) probability interval. By minimizing this loss function, the model can optimize the semantic classification accuracy of building targets pixel by pixel.

Finally, the gate-modulated features are concatenated with the features from the unmodulated 1 × 1 convolution branch and the up-sampled global context features . These are then passed through a final 1 × 1 convolution to output class probability maps, followed by a 4× bilinear up-sampling to obtain the preliminary building segmentation result.

3.4. Post-Processing

The building extraction results from image segmentation are still raster data, lacking the vector geometric entity attributes required for 3D interaction. Therefore, it is necessary to post-process the results before dynamic individualization. First, the prediction results need to be binarized, and the Suzuki Border Following Algorithm is used to extract the topological contours of all connected components. As a classic method for topological analysis of binary images in computer vision, the core advantage of this algorithm lies in its ability to parse the hierarchical relationships (Hierarchy) between contours. This means it can not only extract the outer boundaries of buildings but also effectively identify and preserve internal courtyards or atriums (i.e., hole structures) within large buildings, thereby ensuring the integrity and correctness of the building topology. Based on this characteristic, and benefiting from the high segmentation precision of GA-HRNet (where mis-segmentation noise is typically minute in area), a standard area threshold filtering is sufficient to remove minor background noise while accurately preserving authentic internal architectural structures.

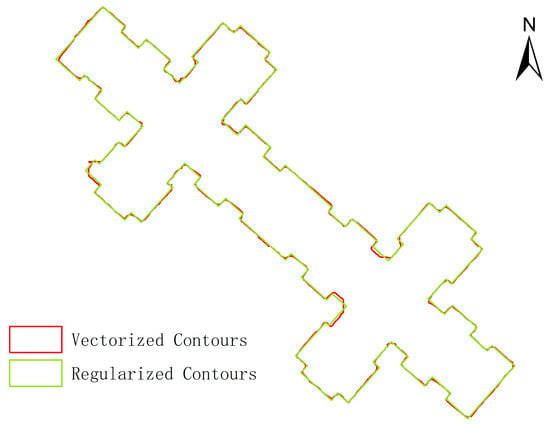

Subsequently, based on the geographic transformation matrix of the original image, the pixel coordinates in image space are accurately mapped back to geographic space coordinates through an affine transformation. To address the jagged edges inherent in raster segmentation, an orthogonal geometric regularization algorithm based on least-squares optimization can be further introduced. It is crucial to note that this process is implemented under strict precision control. Utilizing the regularization toolchain of ArcGIS Pro (version 3.0.1), explicit Simplification Tolerance and orthogonality weight constraints are preset to forcibly reconstruct irregular pixel edges into regularized vector polygons that conform to the right-angled morphological characteristics of buildings. This parameter-controlled constructive process provides an intrinsic guarantee for the geometric regularity of the final output at the algorithmic level.

3.5. Dynamic Individualization

To efficiently map the aforementioned 2D geometric information back into 3D space, this study selects dynamic inclusion rendering for 3D individualization. This method places the individualization process within the real-time rendering pipeline, avoiding the complexity of physical segmentation and the high cost of manual reconstruction, thus possessing significant advantages in implementation efficiency. This study primarily implements this process via programming based on the open-source Web 3D globe engine, CesiumJS: In the visualization rendering pipeline of the 3D scene, when a user clicks on a specific building, the system uses its corresponding 2D segmentation mask as a screen-space overlay layer, dynamically projecting it based on the current viewpoint. This mask layer is assigned a specific color and transparency and is directly superimposed on the final rendered image frame. Synchronized with the popping up of the associated attribute information box, the system visually generates a bounding box to highlight the target building, realizing interactive dynamic individualization.

4. Experiment

4.1. Experimental Settings

All experiments were implemented based on the PyTorchdeep learning framework (version 2.5.1+cu121), with the hardware environment being an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3060 (12GB VRAM) (NVIDIA Corp., Santa Clara, CA, USA). To ensure fairness and consistency in the comparative experiments, all baseline models in this study were trained and evaluated using the exact same dataset of orthophoto patches generated from the oblique photogrammetry models as GA-HRNet. During the data pre-processing stage, all input images were standardized based on the ImageNet statistical distribution. Furthermore, to enhance the model’s convergence speed and feature extraction capabilities, weights pretrained on the ImageNet dataset were loaded to initialize the HRNet backbone, followed by fine-tuning on the custom-built dataset. In the network training process, the AdamW optimizer was used for parameter updates, with an initial learning rate set to 0.0001, a batch size set to 8, and a total of 50 training epochs. During the inference and evaluation stage, to eliminate block edge effects, all models used a 512 × 512 pixel sliding window with a 0.5 overlap for prediction, with the average value taken for overlapping regions. The evaluation metrics include Intersection over Union (IoU), F1-Score, Precision, and Recall.

4.2. Overall Model Performance Evaluation

To validate the effectiveness of GA-HRNet in real-world application scenarios, a comprehensive qualitative and quantitative evaluation was conducted on the independent test set. As shown in Table 2, the model demonstrates superior comprehensive segmentation capabilities across various statistical metrics, achieving an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 91.25% and an F1-Score of 95.41%.

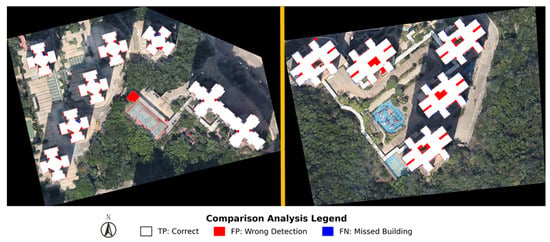

Table 2.

GA-HRNet Various Metric Results.

First, addressing the challenge that rich image details require high spatial detail preservation capabilities, the high Precision of 93.31% and IoU of 91.25% indicate that the predicted pixels align closely with the ground truth in spatial location. This confirms that the HRNet backbone, by maintaining high-resolution feature streams throughout, successfully adapts to the detailed characteristics of the 0.05-m resolution imagery, effectively reducing the common issues of boundary blurring or detail loss in traditional methods. Second, regarding the challenge where large data scales and block processing strategies tend to limit receptive fields, leading to large-scale incomplete segmentation, the model also achieved a Recall of 97.70%. Combined with the visualization results in Figure 6, it can be observed that blue pixels (representing omission errors) are almost non-existent in the test area, with no significant fragmentation appearing within large building footprints. This indicates that the G-ASPP module, through its gating mechanism, effectively aggregates global context, compensating for the local perspective limitations and ensuring intra-class prediction consistency. In summary, these results confirm that GA-HRNet effectively synergizes the spatial detail preservation capability of HRNet with the multi-scale context awareness of ASPP, successfully achieving high-precision building extraction.

Figure 6.

Segmentation Result.

4.3. Experiment Results

To further benchmark the performance of the GA-HRNet model for the task of high-precision building extraction for 3D individualization, a lateral comparison was conducted against several classic and recent advanced semantic segmentation models. Comparative models include: classic encoder–decoder architectures FCN and U-Net, as well as SCA-Net [44], MBR-HRNet [45], and Easy-Net [46], which have performed well in the field of remote sensing image segmentation in recent years.

The quantitative evaluation results of each model on the test set are shown in Table 3. The data shows that GA-HRNet achieved excellent performance on all four key evaluation metrics. Its Intersection over Union (IoU) reached 91.25%, and its F1-Score reached 95.41%; these two comprehensive metrics reflect that it achieved the best balance between segmentation accuracy and completeness.

Table 3.

Performance Comparison of Different Models on the Test Set.

In comparison with the baseline FCN and U-Net, GA-HRNet led by 5.62% and 4.92% in IoU respectively, demonstrating the advancements of modern network architectures in feature representation and context modeling capabilities.

In comparison with more advanced models from recent years, GA-HRNet’s advantage is equally obvious. Among them, MBR-HRNet also uses the HRNet model as a backbone but optimizes extracted building contours by introducing parallel auxiliary boundary loss, while GA-HRNet enhances feature representation by designing a context gating mechanism inside the main segmentation head. Experimental results show that GA-HRNet’s IoU is 1.46% higher than MBR-HRNet. This result reflects that, for the task scenario of this study, optimizing the internal consistency of the backbone feature stream may be a more critical path to performance improvement than simply imposing external boundary constraints.

Although Easy-Net achieved the highest score of 97.89% in the Recall metric, slightly higher than GA-HRNet’s 97.70%, its Precision was only 90.27%, which is at a lower level among advanced models in recent years. This indicates that in the high-precision building extraction task of this study, Easy-Net exhibits a tendency of high recall and low precision. While this tendency ensures maximum detection of building targets, it also leads to more background pixels being misclassified as buildings, causing its comprehensive metric IoU (88.42%) to lag significantly.

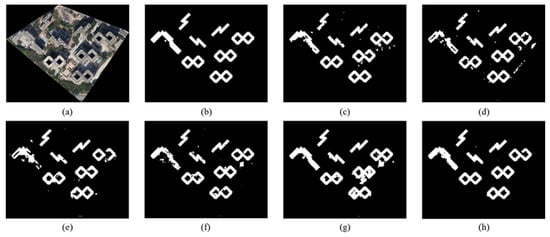

As shown in Figure 7, compared to other models, the gating mechanism of GA-HRNet not only effectively maintains high building integrity by enhancing contextual understanding but also makes the judgment of building boundaries more precise by suppressing irrelevant features, thereby reducing the misclassification of the background.

Figure 7.

Comparison of various models. (a) Original image; (b) Ground truth; (c) FCN; (d) U-Net; (e) SCA-Net; (f) MBR-HRNet; (g) Easy-Net; (h) GA-HRNet. Note: The map orientation is North-up.

4.4. Ablation Study

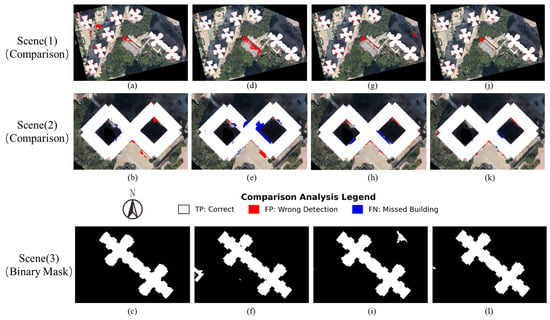

To quantify the synergistic effect of HRNet and ASPP within the GA-HRNet architecture, DeepLabV3+ served as the baseline. Key components were then gradually introduced or replaced to enable comparative analysis. The detailed outcomes are shown in Table 4 and Figure 8.

Table 4.

Ablation Study Performance Comparison.

Figure 8.

Comparison of Model Extraction Effects. (a–c) DeepLabV3+; (d–f) HRNet-V2; (g–i) HRNet-ASPP; (j–l) GA-HRNet.

Comparing the performance of DeepLabV3+ and HRNet-V2, HRNet-V2 possesses a clear advantage of 1.23% in the IoU metric, strongly proving that its design of continuously maintaining high-resolution feature streams can effectively avoid spatial information loss. This is also intuitively verified in Scene (3) of Figure 8: compared to the overly smooth and rounded contours in the DeepLabV3+ prediction results, the building boundaries generated by HRNet-V2 are sharper and fit the real right-angled edges better.

However, while achieving sharp boundaries, HRNet-V2 also exposed its deficiency in context understanding capabilities. As shown in Table 4, its Recall metric is relatively low, and missed detections of target areas and several obvious holes appeared inside the extracted building regions in Scene (2) and Scene (3) of Figure 8. This indicates that high-resolution features alone are insufficient to ensure segmentation completeness.

On the basis of HRNet-V2, after replacing the decoder with the classic ASPP module, the resulting HRNet-ASPP model further improved IoU by 0.25%. More importantly, its Recall metric significantly rebounded to 97.63%, effectively verifying ASPP’s ability to capture multi-scale context information. From Scene (1) in Figure 8, it can be seen that HRNet-ASPP significantly reduced mis-segmentation in many areas compared to the former two, proving that multi-scale context helps to better distinguish targets from backgrounds. Especially in Scene (2), HRNet-ASPP also effectively filled the missing parts after HRNet-V2 segmentation, improving the completeness of the building subject.

Finally, the GA-HRNet proposed in this paper achieved the best performance across all metrics by introducing a context gating mechanism into ASPP. Its IoU reached 91.25%, achieving another 0.73% improvement compared to HRNet-ASPP. Unlike the static traditional ASPP, G-ASPP dynamically recalibrates multi-scale features channel-wise via a dynamic gating signal. This adaptive mechanism enables GA-HRNet to inherit the fine boundary delineation capability of HRNet while reinforcing context perception, achieving superior subject completeness and background purity.

To further validate the rationality of the loss function selection and to address the potential class imbalance issue in the dataset, the experiment further explored the impact of different loss functions on model performance. In addition to the standard BCE Loss, the experiment also introduced two classic loss functions specifically designed for class imbalance for comparison: (1) Dice Loss, a region-based metric learning loss; and (2) Focal Loss, a loss function that focuses training on hard examples by down-weighting easy samples. The results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Impact of Different Loss Functions on GA-HRNet Performance.

All experiments were conducted on the GA-HRNet model. The results show that introducing complex balancing loss functions did not lead to an improvement in overall performance. Using Dice Loss resulted in a significant drop in IoU to 87.91% and F1-Score to 93.55%. Although Focal Loss achieved a marginal advantage in Precision (93.42%), its IoU (90.67%) and Recall (96.96%) were both slightly lower than the standard BCE Loss. This may be because the G-ASPP module within GA-HRNet already possesses strong contextual feature selection capabilities, which can effectively suppress background noise at the feature level, thus mitigating the reliance on loss function weighting. Furthermore, BCE Loss provides a smoother optimization landscape, which is conducive to robust convergence on ultra-high-resolution imagery. The empirical analysis indicates that although class imbalance exists in the dataset, it does not constitute a primary bottleneck limiting model performance, and also confirms the effectiveness and suitability of the standard BCE Loss for this high-resolution remote sensing segmentation task.

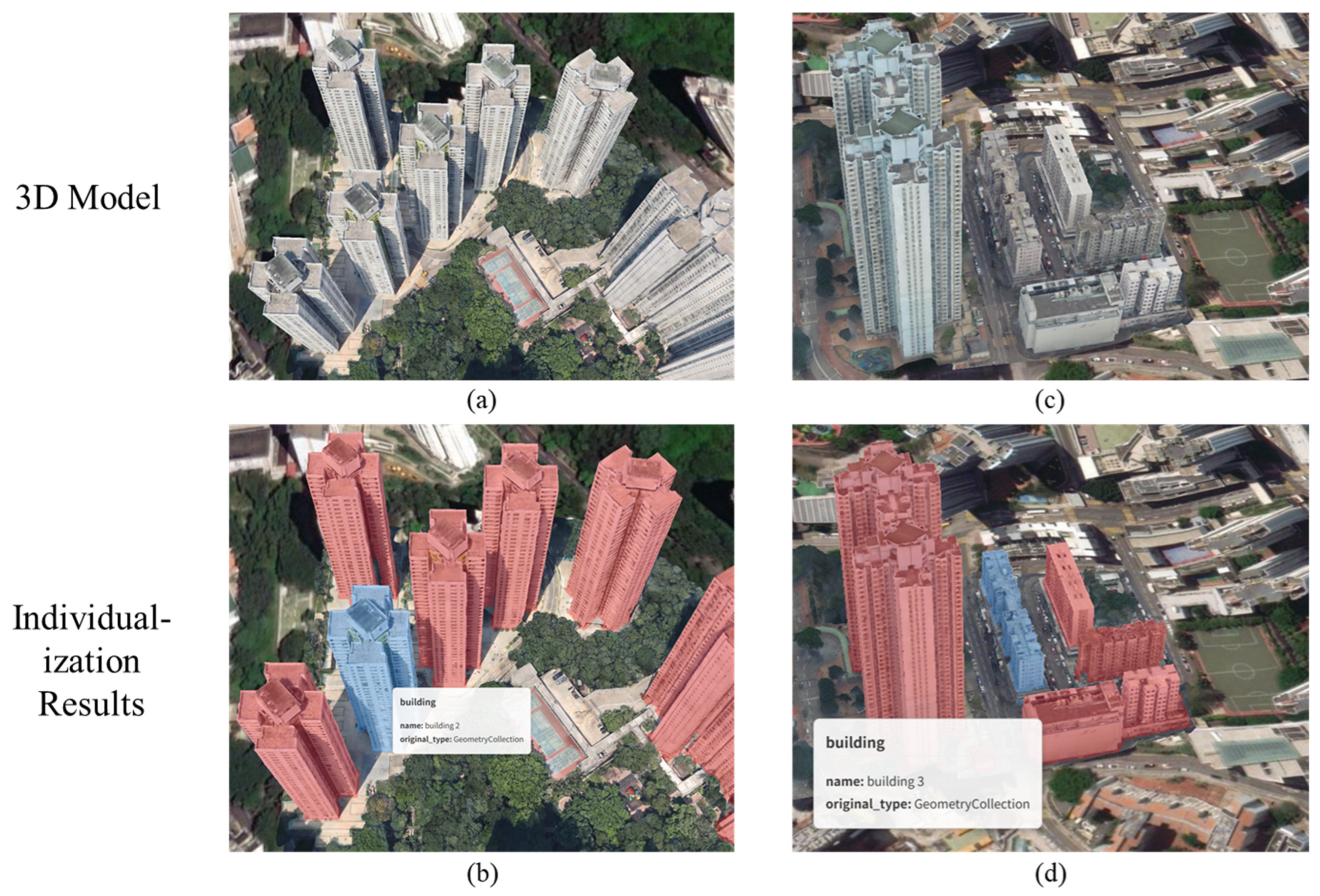

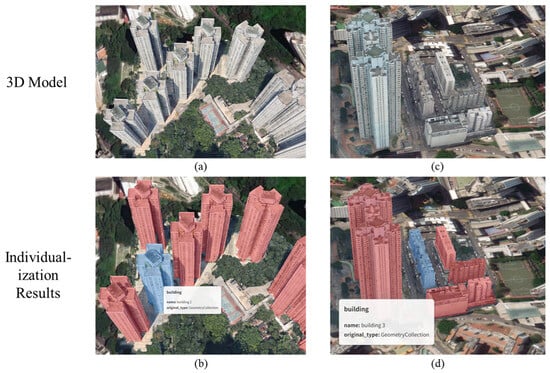

4.5. Dynamic Individualization Effect Display

The ultimate goal of this study is to verify that the 2D high-precision segmentation results generated by the proposed GA-HRNet model can effectively support the efficient dynamic individualization application of oblique photography 3D models. The process is based on the optimal segmentation mask output by GA-HRNet, which, after vectorization and geometric regularization processing, generates precise building contour vector data, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Building Vector Results.

Subsequently, these high-precision vector contours were integrated into a Web 3D scene based on CesiumJS to achieve interactive highlighting of target buildings through dynamic inclusion rendering. Figure 10 visually displays the final application results of this technical workflow (to enhance scene realism, a satellite map was used as the basemap). As shown in the figure, whether in the scene shown in Scene 1, characterized by relatively uniform building heights and morphologies, or in the scene depicted in Scene 2, featuring significant height disparities and diverse building forms, our method consistently achieves robust segmentation and precise dynamic individualization for all building targets within the model. When a target building is selected in the 3D scene, the system utilizes the precise 2D vector contour to project and fit a semitransparent mask onto the building surface in real-time and dynamically via mask overlay. Thanks to the GA-HRNet model’s powerful capability to capture fine boundaries, the individualized visual boundary can precisely conform to every corner and contour variation of the building, ensuring that the final dynamic rendering effect is free of noticeable offsets, rendering omissions, or erroneous inclusion issues. Furthermore, this dynamic rendering method is highly efficient because it does not involve any physical cutting or modification of the original oblique photography 3D model (OSGB) data, only performing mask overlay at the end of the rendering pipeline. This allows users to perform smooth, real-time roaming, zooming, and point-selection queries in the 3D scene and instantly obtain high-precision building individualization highlighting feedback.

Figure 10.

Dynamic individualization effects: (a,b) Scene 1: an area with relatively uniform building heights and similar morphologies; (c,d) Scene 2: an area with significant building height disparities and diverse morphologies.

5. Discussion

Based on the preceding experimental results, this study has verified the effectiveness of GA-HRNet in the task of building extraction from oblique photogrammetry, as well as the feasibility of the “orthophoto generation → high-precision contour extraction → dynamic 3D rendering” technical route. To further elucidate the contributions and shortcomings of this study relative to existing methods, this section provides an in-depth discussion from the perspectives of performance mechanisms and study limitations.

5.1. Mechanism of Performance Advantage

In the comparative experiments, even structurally simpler models like FCN and U-Net achieved commendable IoU scores exceeding 85%. This is primarily attributed to the extremely rich feature details and clear boundaries provided by the 0.05-m ultra-high-resolution orthophotos, which, to some extent, compensated for the models’ capability limitations. However, the inability of these classic models to break the 90% accuracy bottleneck highlights an intrinsic contradiction in fixed architectures when processing such data: the ultra-high resolution requires high spatial detail preservation, while the complete semantic understanding of large buildings relies on large receptive fields gained through deep down-sampling. As noted by Wang J et al. [40] in semantic segmentation research, traditional segmentation networks trade receptive fields via a “downsample–upsample” mechanism, leading to irreversible spatial information loss; this explains why the contours generated by DeepLabV3+ [41] often appear rounded at corners. In contrast, the results of this study confirm that the parallel resolution architecture inherited from HRNet, by maintaining high-resolution feature streams throughout, fundamentally reduces the information loss caused by down-sampling. This architectural design maximally preserves spatial geometric information, allowing the pixel grid of the feature maps to maintain strict alignment with the physical edges in the ultra-high-resolution orthophotos, thereby producing boundaries that are sharper, more regular, and more consistent with the right-angled characteristics of buildings.

Furthermore, to address the issue of omission errors under high resolution due to a lack of sufficient global context, the modified G-ASPP module in this study effectively mitigates this problem by introducing a gating mechanism. Unlike Zhu et al. [33] in MAP-Net, who focused on using channel attention for feature fusion, G-ASPP utilizes global context to generate dynamic gating signals, realizing adaptive recalibration of feature channels. Compared to models such as SCA-Net [44], MBR-HRNet [45], and Easy-Net [46], GA-HRNet demonstrates superior adaptability: when dealing with large-scale targets like shopping malls and factories, its gating mechanism activates large-dilation-rate channels to expand the effective receptive field, thereby reducing large-scale segmentation holes within buildings; conversely, when facing small-scale targets, the global context indicates high-frequency spatial changes, prompting the model to suppress the weights of large-dilation-rate channels and focus on local features. This effectively reduces the introduction of irrelevant background information, prevents the phenomenon of “over-segmentation,” and improves background purity.

From the perspective of the overall framework, the technical route of this paper also exhibits good adaptability. Since the orthophotos are directly generated from the 3D model [42,43], a strict mathematical linear mapping relationship between 2D pixel coordinates and 3D spatial coordinates is guaranteed. This implies that every building contour extracted by GA-HRNet can be precisely aligned with the geometric position of the original model when mapped back to 3D space, effectively avoiding the registration errors commonly observed when using traditional remote sensing images for building extraction.

5.2. Limitations

Despite proposing a complete high-precision individualization framework, this study is subject to certain limitations imposed by data characteristics and environmental complexity.

First, the experimental data for this study were primarily derived from the high-density urban scenarios of the Kowloon Peninsula, Hong Kong. While this area is highly representative and challenging, the model’s generalization ability in low-density rural areas or regions with different architectural styles (e.g., historical European buildings) remains to be verified in future work through the introduction of multi-source heterogeneous data.

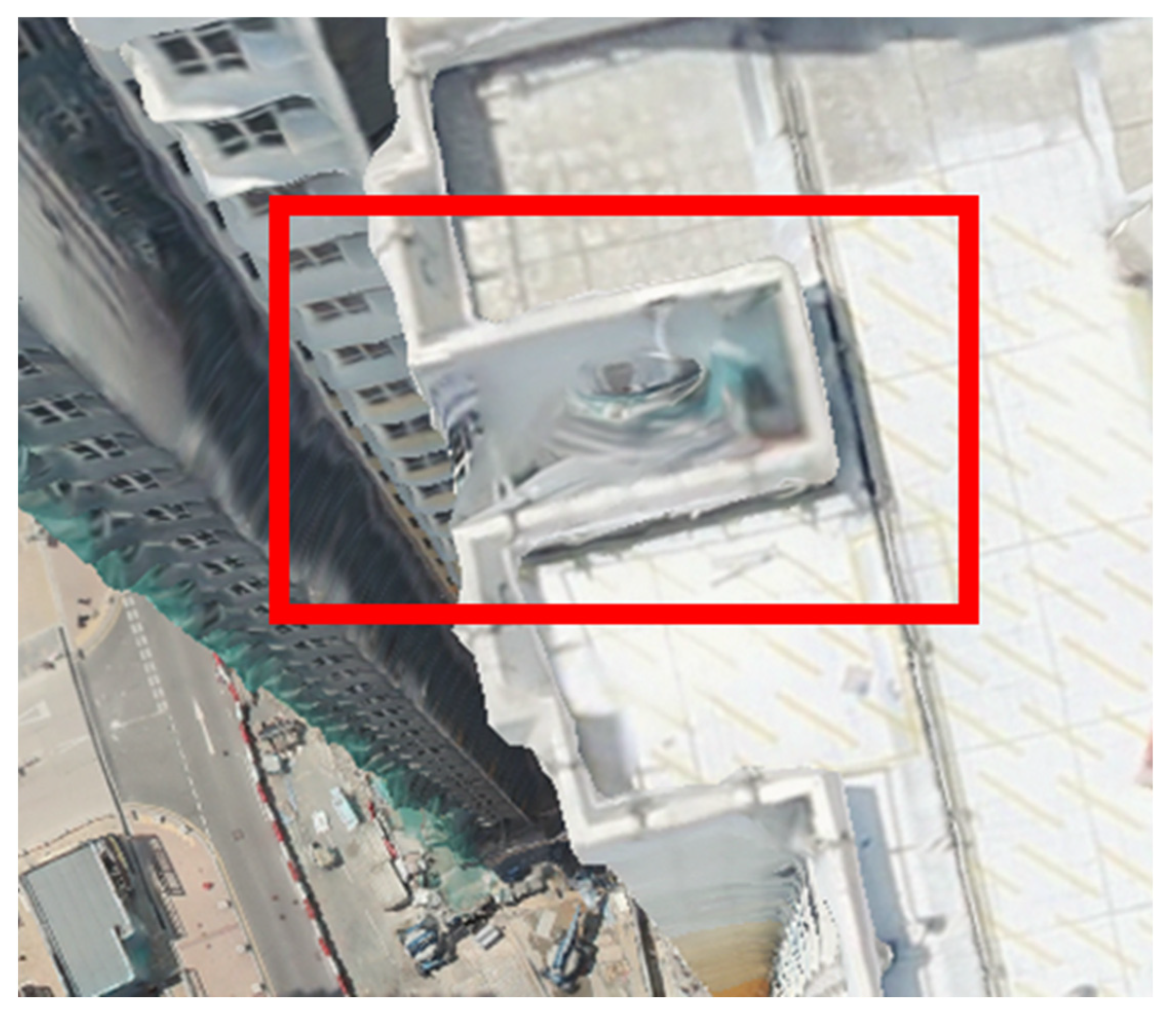

Second, although GA-HRNet performs exceptionally well overall, there is still room for improvement in segmentation accuracy when dealing with extreme scenes involving severe vegetation occlusion or strong shadow coverage.

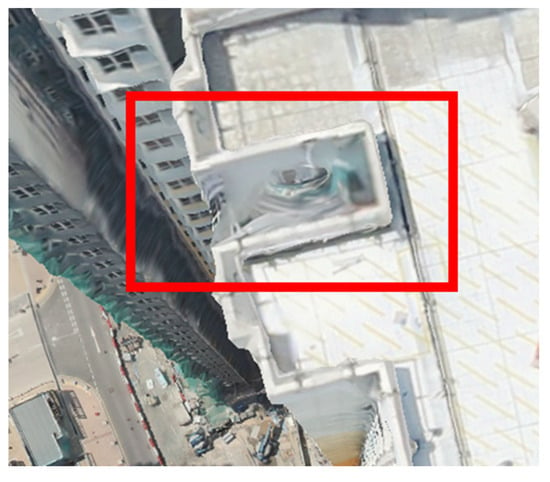

Finally, in some narrow spaces between buildings, oblique photogrammetry models often exhibit geometric “adhesion” due to the physical bottlenecks of multi-view matching algorithms, as shown in Figure 11. These areas appear as connected geometries in the original 3D model, causing the generated orthophotos to also present visually continuous pixel blocks. Although human annotators typically separate these areas based on cognitive experience when creating ground truth labels, this also introduces certain errors. As shown in the segmentation results for some buildings in the preceding Figure 6, the segmentation network tends to faithfully reflect the adhered features in the imagery, identifying the narrow spaces with building adhesion as part of the building itself, which results in inconsistencies with the manual ground truth.

Figure 11.

Geometric adhesion phenomenon (the highlight in red) in oblique photogrammetry models.

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Addressing the application challenges of building individualization in oblique photography 3D models, this study proposed the GA-HRNet model and, based on this model, constructed and verified a building individualization technical framework integrating 2D high-precision segmentation and 3D dynamic rendering. Experimental results indicate that the constructed GA-HRNet model achieved an Intersection over Union (IoU) of 91.25% on a custom-built dataset, outperforming multiple comparative models. This result confirms the effectiveness of the proposed context gating mechanism in synergizing the advantages of HRNet and ASPP. Based on the high-precision segmentation results output by this model, efficient and precise individualization of oblique photography 3D models was finally achieved through dynamic inclusion rendering technology, validating the feasibility and value of this technical route in refined urban 3D data management and visualization applications. In the future, the extracted high-precision contours can be used as geometric priors to constrain and guide the 3D model reconstruction of individual buildings, thereby achieving physical-level instance segmentation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and J.Z.; methodology, Y.Z., J.Z. and F.L.; software, J.Z. and Y.Q.; validation, J.Z., J.W., R.W. and Y.Z.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and J.Z.; investigation, J.W.; resources, F.L., R.W. and Y.Z.; data curation, J.Z., F.L. and R.W.; writing—original draft preparation, J.Z. and Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z. and Y.Q.; visualization, J.W.; supervision, Y.Z.; project administration, Y.Z.; funding acquisition, Y.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Open Fund of Key Laboratory of Monitoring, Evaluation and Early Warning of Territorial Space Planning, Ministry of Natural Resources, grant number LMEE-KF2024011; the Performance Incentive Guidance Program for Scientific Research Institutions of Chongqing Municipality, grant number CSTB2025JXJL-YFX0008; the Key Research and Development Program of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, grant number 2024BEG02042; and the Research Project of Chongqing Planning and Natural Resources Bureau, grant number KJ-2025014 and KJ-2025016.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. The raw 3D model data can be found here: https://www.pland.gov.hk/pland_en/info_serv/3D_models/download.htm (accessed on 23 June 2025). The processed building extraction dataset generated during the study is available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions regarding detailed spatial information and ongoing internal research projects.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the Planning Department of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region for providing the 3D reality models used in this study. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used Gemini 3 pro for translation assistance and language polishing. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DOM | Digital Orthophoto Map |

| ASPP | Atrous Spatial Pyramid Pooling |

| HRNet | High-Resolution Network |

| GA-HRNet | Gated-ASPP High-Resolution Network |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| GAP | Global Average Pooling |

References

- Riaz, K.; McAfee, M.; Gharbia, S.S. Management of climate resilience: Exploring the potential of digital twin technology, 3D city modelling, and early warning systems. Sensors 2023, 23, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiğit, A.Y.; Uysal, M. Virtual reality visualisation of automatic crack detection for bridge inspection from 3D digital twin generated by UAV photogrammetry. Measurement 2025, 242, 115931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christodoulides, A.; Tam, G.K.L.; Clarke, J.; Smith, R.; Horgan, J.; Micallef, N.; Morley, J.; Villamizar, N.; Walton, S. Survey on 3D Reconstruction Techniques: Large-Scale Urban City Reconstruction and Requirements. IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graph. 2025, 31, 9343–9367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Chen, W.; Lu, X. Automated Assessment of Wind Damage to Windows of Buildings at a City Scale Based on Oblique Photography, Deep Learning and CFD. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 52, 104355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Chen, J.; Song, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, F.; Wang, S.; Liu, D. Proposition of UAV multi-angle nap-of-the-object image acquisition framework based on a quality evaluation system for a 3D real scene model of a high-steep rock slope. Int. J. Appl. Earth Obs. Geoinf. 2023, 125, 103558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, F.; Shi, L.; Liu, Z.; Wang, C.; Fan, Y. Rapid integration strategy for oblique photogrammetry terrain and highway BIM models in large-scale scenarios. Autom. Constr. 2025, 177, 106354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.A.H.; Nguyen, C.; Li, H.; Li, B. Fixed-Lens camera setup and calibrated image registration for multifocus multiview 3D reconstruction. Neural Comput. Appl. 2021, 33, 7421–7440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verykokou, S.; Ioannidis, C. An overview on image-based and scanner-based 3D modeling technologies. Sensors 2023, 23, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Gao, J.; Ji, S.; Zeng, C.; Zhang, S.; Gong, J. Deep learning based multi-view stereo matching and 3D scene reconstruction from oblique aerial images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2023, 204, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Zhou, P.; Du, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhu, J. NMSCANet: Stereo Matching Network for Speckle Variations in Single-Shot Speckle Projection Profilometry. Opt. Express 2024, 32, 5849–5863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, C.; Song, Y.; Ji, J.; Jia, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Gao, P.; Liu, S. Automatic classification of rural building characteristics using deep learning methods on oblique photography. Build. Simul. 2022, 15, 1161–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, G.; Sun, W. Automatic Extraction of Building Geometries Based on Centroid Clustering and Contour Analysis on Oblique Images Taken by Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2022, 36, 453–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, X.; Lin, L.; Lu, H.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, W.; Yue, J.; Li, Z. A Single Data Extraction Algorithm for Oblique Photographic Data Based on the U-Net. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.Y.; Zhang, X.P.; Shi, L. Research on the Algorithm of Building Object Boundary Extraction Based on Oblique Photographic Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE 3rd Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chongqing, China, 12–14 October 2018; pp. 1957–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Rottensteiner, F.; Heipke, C. Modelling of buildings from aerial LiDAR point clouds using TINs and label maps. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 154, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.; Ji, S.; Liu, J.; Wei, S. Automatic 3D building reconstruction from multi-view aerial images with deep learning. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 171, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübner, P.; Weinmann, M.; Wursthorn, S.; Hinz, S. Automatic voxel-based 3D indoor reconstruction and room partitioning from triangle meshes. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2021, 181, 254–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, S.; Sarker, P.; Stone, G.; Gorman, R.; Tavakkoli, A.; Bebis, G.; Sattarvand, J. A comprehensive overview of deep learning techniques for 3D point cloud classification and semantic segmentation. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2024, 35, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zeng, Y.; Yin, C. 3D City Reconstruction: A Novel Method for Semantic Segmentation and Building Monomer Construction Using Oblique Photography. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.; Fernandez-Beltran, R.; Sun, X.; Ni, J.; Plaza, A. Deep Learning-Based Building Footprint Extraction With Missing Annotations. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 3002805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.H.; Shin, H.; Kwon, N.; Ho, J.; Ahn, Y. Deep Learning Based Urban Building Coverage Ratio Estimation Focusing on Rapid Urbanization Areas. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 11428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oostwegel, L.J.N.; Schorlemmer, D.; Guéguen, P. From Footprints to Functions: A Comprehensive Global and Semantic Building Footprint Dataset. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrotter, G.; Hürzeler, C. The Digital Twin of the City of Zurich for Urban Planning. J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Geoinf. Sci. 2020, 88, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; He, J. Evaluation of the urban heat island effect based on 3D modeling and planning indicators for urban planning proposals. J. Asian Archit. Build. Eng. 2025, 24, 5634–5656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Antwi-Afari, M.F.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Manu, P. BIM, IoT, and GIS integration in construction resource monitoring. Autom. Constr. 2025, 174, 106149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcaraz, C.; Lopez, J. Digital Twin: A Comprehensive Survey of Security Threats. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2022, 24, 1475–1503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wu, J.; Liu, L.; Zhao, W.; Tian, F.; Shen, Q.; Zhao, B.; Du, R. DR-Net: An Improved Network for Building Extraction from High Resolution Remote Sensing Image. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boonpook, W.; Tan, Y.; Torsri, K.; Kamsing, P.; Torteeka, P.; Nardkulpat, A. PCL–PTD Net: Parallel cross-learning-based pixel transferred deconvolutional network for building extraction in dense building areas with shadow. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 773–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, R.; Fan, X.; Liu, J. EUNet: Edge-UNet for Accurate Building Extraction and Edge Emphasis in Gaofen-7 Images. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, J.; Liu, D. SFGNet: Salient-feature-guided real-time building extraction network for remote sensing images. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 317, 113413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Qi, W.; Li, X.; Gross, L.; Shao, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Ni, L.; Fan, X.; Li, Z. ARC-Net: An Efficient Network for Building Extraction From High-Resolution Aerial Images. IEEE Access. 2020, 8, 154997–155010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Z.; Tang, P.; Wang, Z.; Saleem, N.; Yam, S.; Sommai, C. BRRNet: A Fully Convolutional Neural Network for Automatic Building Extraction From High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Liao, C.; Hu, H.; Mei, X.; Li, H. MAP-Net: Multiple Attending Path Neural Network for Building Footprint Extraction From Remote Sensed Imagery. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 59, 6169–6181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghalles, K.; Li, H.C.; Al-Huda, Z.; Hezzam, E.A. Multi-task deep network for semantic segmentation of building in very high resolution imagery. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference of Technology, Science and Administration (ICTSA), Taiz, Yemen, 22–24 March 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, F.S.; Karsli, F.; Bahadir, M.; Yildirim, M. FwSVM-Net: A novel deep learning-based automatic building extraction from aerial images. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 96, 110473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Fang, S.; Meng, X.; Li, R. Building Extraction with Vision Transformer. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5625711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, F.; Jiang, F.; Li, J.; Lu, L. MSTrans: Multi-Scale Transformer for Building Extraction from HR Remote Sensing Images. Electronics 2024, 13, 4610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.O.; Kavzoglu, T. DeepSwinLite: A Swin transformer-based light deep learning model for building extraction using VHR aerial imagery. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, B.; Misra, I.; Schwing, A.G.; Kirillov, A.; Girdhar, R. Masked-attention Mask Transformer for Universal Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1280–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Sun, K.; Cheng, T.; Jiang, B.; Deng, C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, D.; Mu, Y.; Tan, M.; Wang, X.; et al. Deep High-Resolution Representation Learning for Visual Recognition. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 3349–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-C.; Zhu, Y.; Papandreou, G.; Schroff, F.; Adam, H. Encoder-Decoder with Atrous Separable Convolution for Semantic Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 801–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Jiang, G.; Li, Y. A Novel Method for Digital Orthophoto Generation from Top View Constrained Dense Matching. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yan, Q.; Qu, Y.; Gao, W.; Yang, J.; Deng, F. Ortho-NeRF: Generating a True Digital Orthophoto Map Using the Neural Radiance Field from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Images. Geo-Spat. Inf. Sci. 2024, 28, 741–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Wu, Y.; Tian, W.; Zhang, G. SCA-Net: Multiscale Contextual Information Network for Building Extraction Based on High-Resolution Remote Sensing Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 4466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, G.; Jing, H.; Li, H.; Guo, H.; He, S. Enhancing Building Segmentation in Remote Sensing Images: Advanced Multi-Scale Boundary Refinement with MBR-HRNet. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Liu, J.; Wang, R. Easy-Net: A Lightweight Building Extraction Network Based on Building Features. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 4501515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.