Abstract

With the continuous increase in high-speed train operating speeds, effective vibration suppression of the car body is critical for ensuring passenger comfort. This study proposes a composite damping device based on particle damping technology, featuring a variable cavity structure incorporating spring components designed for space-constrained areas. The primary aim of this work is to elucidate the energy dissipation mechanism of granular media under adaptive boundary conditions and to establish a novel method for overcoming the saturation limitations of traditional fixed-cavity dampers. The energy dissipation characteristics were investigated using coupled Discrete Element Method (DEM) and Multibody Dynamics (MBD) numerical simulations. Parametric analysis quantitatively demonstrated significant performance variations: 2 mm particles outperformed larger diameters by maximizing collision frequency, and cast iron particles (29.497 J) achieved approximately five times the energy dissipation of steel particles (5.909 J). Furthermore, the filling rate exhibited a non-linear relationship with damping performance, peaking at a 98% filling rate (57.251 J)—a nearly 9-fold increase compared to a 90% filling rate. Most notably, quantitative comparison confirms that the introduction of the spring-adaptive mechanism enhanced the total energy dissipation to approximately 2 times that of the traditional fixed-cavity design. Simulation results reveal that the flexible cavity significantly enhances performance by preventing particle packing and stagnation. The dynamic deformation continuously “recruits” particles into high-energy collision regimes, ensuring sustained broadband attenuation. These findings establish the spring-based variable volume design as a high-efficiency strategy for high-speed rail applications.

1. Introduction

High-speed trains have consistently achieved breakthroughs in technological innovation and industrial modernization, with operational speeds rising continuously. The development and entry into service of 400 km/h EMUs [1] mark a significant milestone in the progression toward higher speed grades. However, these increased speeds inevitably exacerbate vibration issues during operation. Vibrations generated by high-speed motion severely limit the broad application of related technologies and impair passenger com-fort [2], making vibration suppression a critical area of research in recent years. Generally, higher operating speeds induce more severe vibrations.

In high-speed regimes, excitation intensity typically scales with travel speed, arising from a diverse array of sources: mechanical imbalances in the wheel–axle assemblies, aerodynamic pressure fluctuations on the car body surface, and track geometric irregularities—such as subgrade settlement or rail wear. Excessive vibrational responses can undermine the stability of wheel–rail contact forces, thereby increasing derailment risks and parasitic energy consumption [3]. Under sustained cyclic loading, critical structural components become highly susceptible to fatigue-induced degradation or catastrophic brittle fracture, severely jeopardizing operational safety. Furthermore, vibration-induced pitching and swaying significantly degrade ride comfort, accelerate component wear and aging, and ultimately drive up lifecycle maintenance costs.

Current mitigation strategies primarily center on three subsystems: suspension systems, yaw dampers, and structural damping. While passive suspension [4,5], comprising primary and secondary stages, and yaw dampers [6] are standard for ensuring dynamic stability and isolating shocks, they often face limitations in broadband performance. Against this backdrop, this paper investigates particle damping technology as a robust solution for car body vibration control. By utilizing loose particles within sealed cavity, this technology leverages inelastic energy dissipation primarily through high-frequency collisions and friction to attenuate vibrational energy. Compared to conventional damping methods, particle damping offers compelling advantages, including structural simplicity, exceptional environmental resilience, and superior broadband dissipation performance.

The fundamental mechanism of particle damping centers on the dissipation of kinetic energy through inelastic collisions and frictional interactions among discrete particles confined within a sealed cavity [7]. This technology is characterized by several distinct advantages, including its non-intrusive nature, exceptional operational reliability, and thermal stability across extensive temperature gradients [8,9,10]. Consequently, it has seen widespread implementation in high-speed rail systems [11,12,13], precision machine tools [14], and rotating machinery. Conceptually, particle damping evolved from the impact damper originally pioneered by Paget [15] for turbine blade mitigation. Subsequent theoretical advancements have expanded this field into a sophisticated taxonomy, ranging from single-unit, single-particle configurations to complex multi-unit, multi-particle systems [16,17,18,19,20].

While the literature offers diverse strategies for vibration control—such as active yaw dampers [21], acceleration-driven control (ADD) [22], acoustic metamaterials for floor structures [23], and optimized variable-thickness plates [24]—the application of particle damping to high-speed rail remains a critical frontier. For instance, Xiao et al. [25] leveraged the Discrete Element Method (DEM) to develop dampers specifically for rail sidewall skins. Despite these advancements, conventional particle dampers typically utilize fixed-volume cavities. This rigidity limits their adaptability to varying excitation conditions and often leads to particle “jamming” or stagnation, reducing energy dissipation efficiency. To overcome these limitations, researchers have explored composite structures incorporating intrusive moving parts or elastic elements. For instance, Bai et al. [26] pioneered a piston-based particle damper and investigated the effect of piston immersion depth via particle dynamics simulations. Their work demonstrated that the interaction between the moving piston and the granular bed is crucial for vibration attenuation, though their design lacked self-adaptive volume capabilities. Further evolving this concept, Zhang et al. [27] developed a Tuned Particle Damper (TPD) by combining a dynamic vibration absorber with a particle damper. Their experimental results proved that the introduction of stiffness (springs) significantly broadens the suppression frequency band compared to traditional designs.

While experiments provide macroscopic validation, visualizing the internal microscopic energy dissipation mechanism remains a challenge. Consequently, the coupling of the DEM and Multibody Dynamics (MBD) has emerged as a robust numerical approach. Shen et al. [28] recently proposed a parallel coupling framework between RecurDyn and DEM software, rigorously validating the method’s accuracy using a spring-damper system and complex industrial applications. Following this state-of-the-art methodological trend, Ye et al. [29] utilized the coupled DEM-MBD method to analyze the energy dissipation characteristics of a spring-particle system. Their study quantified the energy contribution of particle–particle versus particle–wall interactions, confirming that optimizing filling parameters can enhance damping performance.

Particle damping is inherently a non-linear energy dissipation mechanism that exhibits strong frequency dependence. In traditional fixed-cavity dampers, the damping efficiency peaks only within a specific bandwidth where the particle motion resonates with the structural vibration (i.e., the ‘fluid-like’ state). Consequently, performance often degrades significantly when the excitation frequency shifts away from this optimal range. However, existing studies have either focused on external spring-mass systems or fixed-motion pistons. There remains a lack of comprehensive research on spring-adaptive variable cavities, where an internal spring actively modulates the cavity volume to prevent particle stagnation.

This study is fundamentally distinct from prior approaches in three key aspects: Unlike Tuned Particle Dampers (TPDs) where springs are used externally to suspend the entire damper mass, our design integrates the spring internally to act directly on the granular boundary. This transforms the cavity from a passive container into an active dynamic component. Compared to traditional piston-based dampers where the immersion depth is typically fixed or mechanically preset, our sliding plate performs a passive self-adaptive oscillation. This allows the cavity volume to expand and contract instantaneously in response to excitation intensity, preventing the ‘locking’ state often seen in fixed-volume piston dampers. Traditional flexible dampers often rely on material compliance (e.g., rubber walls). In contrast, our stiffness-governed boundary creates a ‘pumping effect’ that maintains particle fluidization even at extremely high filling rates, effectively overcoming the saturation limitations of conventional designs.

The primary aim of this work is to elucidate the energy dissipation mechanism of granular media under these adaptive boundary conditions and to establish a novel method for overcoming the saturation limitations of traditional fixed-cavity dampers. To achieve this, the research proceeds in four stages: (1) structural design and modeling; (2) quantification of collision-induced energy dissipation using DEM; (3) parametric sensitivity analysis of particle properties and spring integration; and (4) evaluation of the damper’s efficacy in mitigating high-speed vehicle body vibrations.

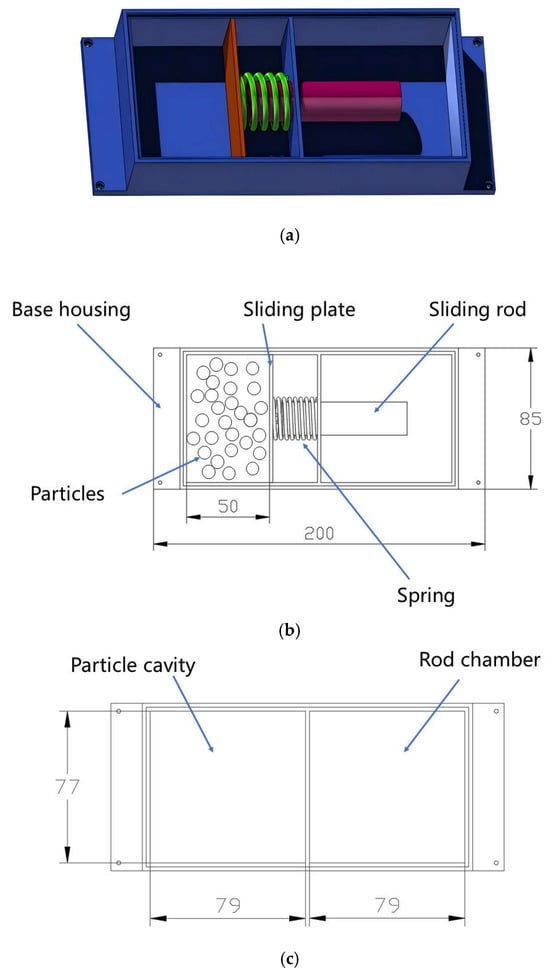

2. Geometric Design of the Particle Damper

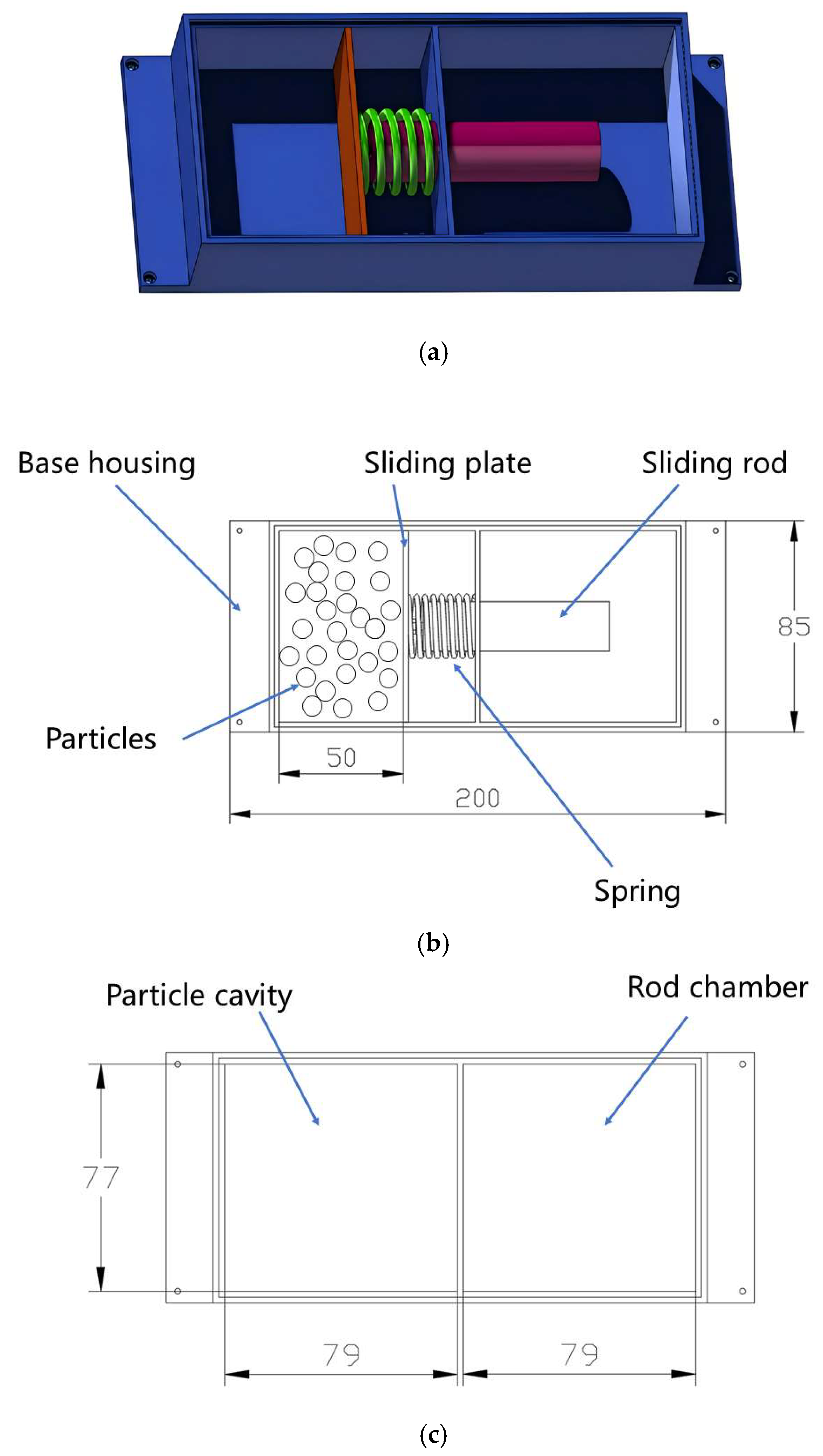

The internal architecture of the particle damper, specifically engineered for integration into a high-speed train car body sidewall, is depicted in Figure 1. To facilitate structural attachment, the base plate features an integrated mounting flange equipped with four bolt holes. The assembly comprises five primary components: the base housing, a sliding rod, a sliding plate, a compression spring, and a sealing cover. Given the stringent spatial constraints within the car body, the device’s footprint is precisely optimized: the base measures 200 mm × 85 mm with a 35 mm depth and a uniform wall thickness of 2 mm. Internally, a transverse bulkhead partitions the housing into two distinct zones: a particle-filled cavity and a sliding rod chamber. This bulkhead is precision-drilled with through-holes to accommodate the 20 mm diameter, 75 mm long sliding rod. Situated within the particle cavity, the 77 mm × 30 mm sliding plate is rigidly coupled to the rod via a bolted connection. A spring is seated between the internal bulkhead and the sliding plate to provide the necessary restorative force. Finally, the assembly is enclosed by a sealing plate, secured by a peripheral bolt pattern along the upper rim of the base. Figure 1b illustrates the internal assembly and the initial working length of 50 mm, while Figure 1c displays the maximum structural length of 79 mm for each chamber.

Figure 1.

Internal Structure of the Particle Damper. (a) 3D schematic diagram; (b) General schematic of the particle damper; (c) Schematic of the particle damper base.

The particle damper is characterized by a compact architecture, with its geometric envelope meticulously optimized for integration within the spatially restricted environments of the train car body. At the core of this design is an integral particle-spring composite mechanism. This configuration enables the damping cavity to exhibit an adaptive dynamic response to varying excitation intensities: the spring assembly concurrently absorbs and dissipates kinetic energy from particle clusters while facilitating the adaptive modulation of the effective cavity volume. This synergistic interaction significantly bolsters the system’s overall energy dissipation capacity. Critical design parameters—including particle diameter, material composition, filling ratio, and the spring-governed volumetric variability—are systematically optimized via subsequent numerical simulations to satisfy stringent vibration attenuation requirements.

3. Fundamental Principles of the Discrete Element Method and Particle Energy Dissipation Mechanism

3.1. Fundamental Principles of the Discrete Element Method

To accurately evaluate vibration suppression, the DEM is employed to simulate the intricate collision dynamics between particles and chamber boundaries. By resolving the motion of individual units across successive time increments, DEM [7] bridges the gap between micro-scale particle interactions and macroscopic system response. The computational core relies on calculating contact forces based on inter-particle overlap via specialized models (e.g., Hertzian or soft-sphere). These forces are then aggregated, and the kinematic response of each particle is determined through the integration of Newton’s equations of motion.

3.2. The Particle Energy Dissipation Mechanism

In this study, the widespread Hertz–Mindlin (no-slip) contact model is adopted to simulate the inter-particle interactions. As this is a well-established theoretical framework in granular mechanics [30,31], this section focuses on the specific implementation and the underlying physical simplifications adopted for the particle damper simulation.

To balance computational efficiency with physical accuracy, the following key assumptions are made:

Idealized Geometry: Particles are modeled as soft spheres, where the overlap represents physical deformation.

Viscoelastic Interaction: The normal force includes both a non-linear elastic Hertzian term and a dissipative dashpot term to capture energy loss during impact.

Coulomb Friction: Tangential forces are modeled using Mindlin–Deresiewicz theory, capped by the Coulomb friction limit (μsFn).

Based on these assumptions, the normal contact force Fn is expressed as the sum of the elastic force (Fn,e) and the damping force (Fn,d):

where E∗ is the equivalent Young’s modulus, R∗ is the equivalent radius, δn is the normal overlap, m∗ is the equivalent mass, is the relative normal velocity, and Sn is the normal stiffness. The damping factor β is related to the coefficient of restitution (e) by :

The tangential contact force Ft, which accounts for sliding friction, is determined by the tangential overlap δt and stiffness St, limited by the coefficient of static friction μs:

where δt denotes the tangential overlap and St is the tangential stiffness, expressed as:

where Gi and Gj are the shear moduli of particles i and j, respectively;

The energy dissipation capability of the damper is the primary metric of interest. The total energy loss (Eloss) is quantified by integrating the work done by non-conservative forces—specifically, the inelastic collision damping and frictional sliding—over the duration of contact:

Here, δ represents the logarithmic decrement, ui denotes the displacement amplitude of the i-th peak, ui+j indicates the amplitude of the (i + j)-th peak, and j signifies the number of cycles between the two peaks. ξ represents the damping ratio of the structure. For small damping ratios (ξ < 0.2), the aforementioned equation simplifies to ξ = δ 2π.

This integral form explicitly accounts for the energy dissipated through the normal dashpot (collision) and tangential sliding (friction).

Finally, to evaluate the macroscopic damping performance of the structure, the equivalent damping ratio ξ is calculated using the logarithmic decrement method based on the time-domain displacement response [32]:

where ui and ui+j represent the peak amplitudes of the i-th and (i + j)-th oscillation cycles, respectively.

4. Numerical Simulation Setup

This section employs a co-simulation framework integrating EDEM2020 and RecurDyn v9r4 to analyze inter-particle collisions and the underlying energy dissipation mechanisms within the damper. Through systematic parametric simulations under identical boundary conditions, the influence of various design variables on energy dissipation efficiency is evaluated. These results establish a robust foundation for the structural optimization of the particle damping system.

EDEM (Altair), a high-fidelity DEM platform, is utilized to track particle trajectories and contact forces via its iterative time-stepping algorithm. While traditional FEA tools like ANSYS support fluid–structure interaction, they often face limitations in bidirectional coupling for this specific class of granular-mechanical problems. In contrast, this study requires a tightly coupled bidirectional interface to investigate the interplay between the variable-volume cavity—governed by the spring assembly—and the granular media. Consequently, RecurDyn (FunctionBay), a specialized Multi-Body Dynamics (MBD) suite, was selected for its superior capability in resolving complex kinematic and contact transients.

To optimize computational economy, standalone EDEM simulations are performed for initial parametric studies involving rigid-body interactions, such as particle diameter, material, and filling ratios. However, for stages involving the flexible damping spring, the EDEM–RecurDyn co-simulation strategy is implemented. This approach accurately captures the transient dynamic response and the bidirectional feedback between particle motion and structural compliance, enabling a comprehensive performance evaluation across diverse parameter sets.

This study employs a sequential optimization strategy. Initially, within the framework of a conventional particle damper, the optimal parameter combination of particle diameter, material, and packing ratio is systematically determined. Subsequently, spring components are introduced to construct a composite damping system. Using the predetermined particle parameters as a baseline, the spring stiffness is matched and calibrated. The selection of stiffness aims to achieve a critical balance: ensuring sufficient driving force to excite energy-dissipating particle motion, while preventing the system ‘stiffening’ effect caused by excessive rigidity, thereby preserving the dynamic adaptability of the particle enclosure’s nonlinear damping characteristics.

Given that the preliminary phase of this study focuses exclusively on rigid-body interactions, standalone EDEM simulations were conducted. The numerical geometry, originally modeled in SolidWorks2022, was imported into the EDEM environment with a defined particle cavity of 77 × 50 × 18 mm and a spring reserve length of 27 mm. The simulation setup incorporated comprehensive material and constitutive properties, including density, shear modulus, and coefficients of restitution, as well as static and rolling friction for both particle–particle and particle–wall interactions. Subsequently, a constant frequency excitation of 100 Hz was applied to the moving components. Regarding simulation parameters, the fixed time step was set to 20% of the Rayleigh time step, and the cell size was defined as 3R. Gravitational acceleration was set to 9.81 m/s2, and the Hertz–Mindlin (no-slip) contact model was employed to resolve the granular dynamics.

Following the incorporation of spring components, a bidirectional co-simulation was initiated using EDEM and RecurDyn. To enhance computational efficiency, the sliding rod and moving plate were modeled as a single integrated rigid assembly. This approach effectively represented the bolted connection while maintaining kinematic equivalence. Based on preliminary iterative simulations, the spring configuration was finalized with an initial length of 27 mm, 5 coils, and a stiffness coefficient of 100. Upon completion of mesh generation, the geometry was exported as a wall file and imported into the EDEM environment. Finally, after verifying the particle parameters and maintaining the fixed time step at 20% and cell size at 3R, the coupling server was activated to commence the co-simulation.

5. Simulation Results and Analysis

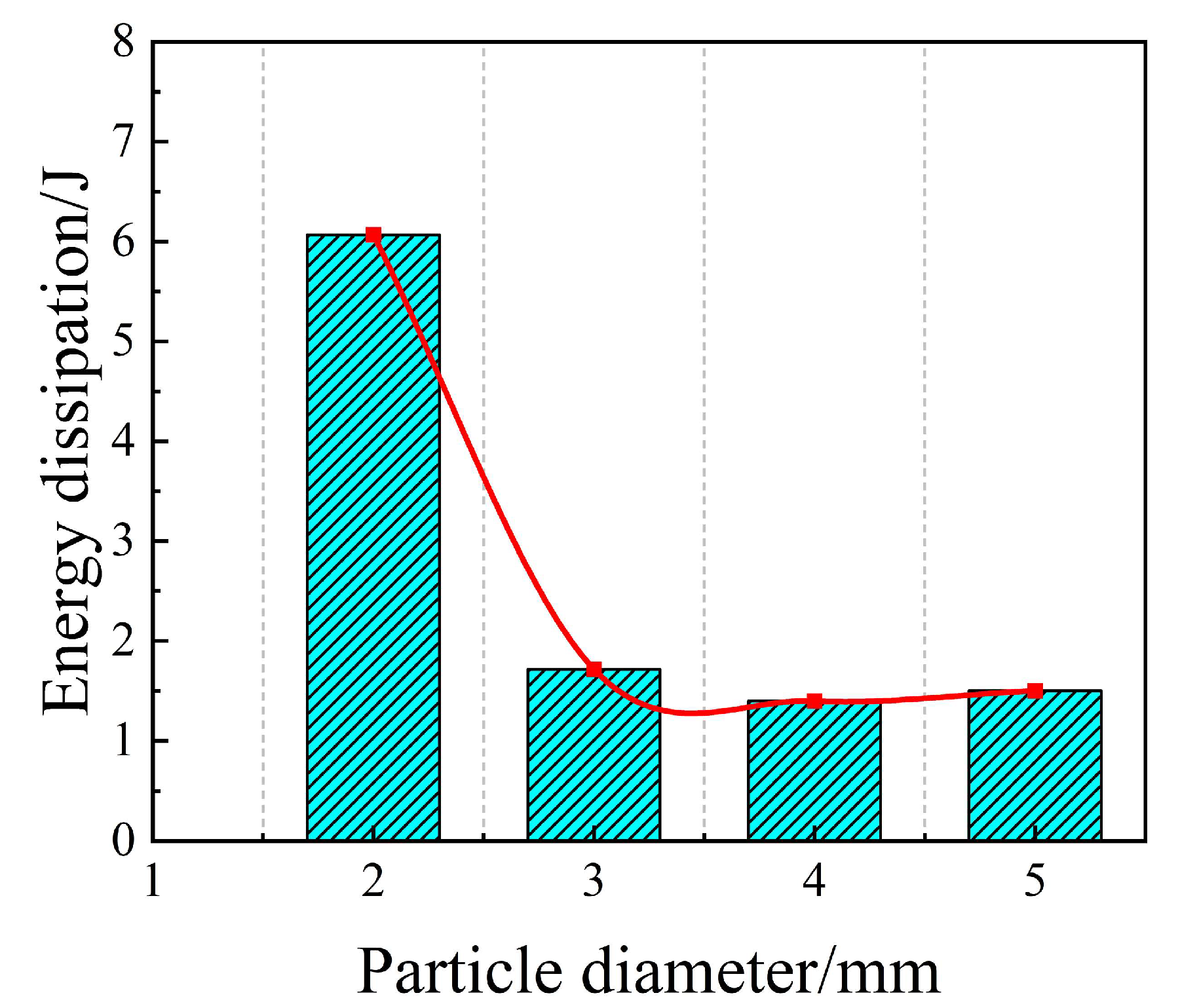

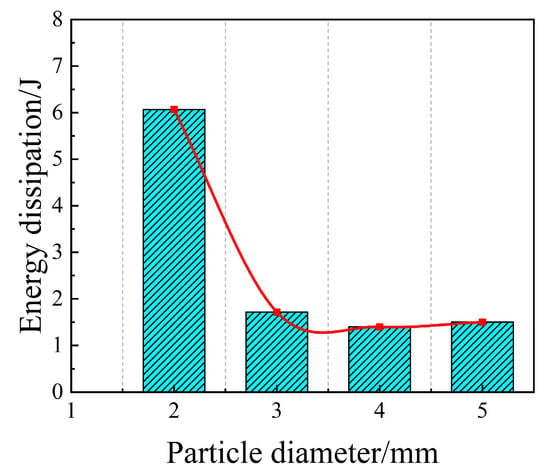

5.1. Particle Diameter Selection for Particle Dampers

Particle diameter serves as a pivotal design variable in determining the efficacy of particle dampers. It dictates the spatial scales of particle trajectories, modulates the system’s frequency response characteristics, and governs the dominant energy-dissipation mechanisms. Consequently, suboptimal particle sizing—whether excessively large or small—can disrupt the particle motion regime, thereby diminishing overall damping efficiency.

To evaluate the sensitivity of energy dissipation to particle size, four diameters of cast-iron particles—5, 4, 3, and 2 mm—were systematically investigated. Benchmarked against the methodology of Xiao et al. [25], simulations were conducted under a harmonic excitation of 100 Hz with a 90% initial filling ratio. Due to the inherent interstitial voids in granular packing, the packing porosity scales with particle diameter, leading to a discrepancy between theoretical and experimental particle counts, as quantified in Table 1. Notably, the actual packing efficiency (actual/theoretical count) increases from approximately 55% at 5 mm to about 59% at 2 mm, indicating the smaller the particle diameter, the higher the particle packing efficiency.

Table 1.

The ideal and actual filling number of particles.

As shown in Figure 2 and Table 2, it is noteworthy that the energy dissipation profile exhibits a local minimum at d = 4 mm (1.398 J), which is slightly lower than that of the 5 mm particles (1.501 J). For larger particles (5 mm), the damping is dominated by the high kinetic energy of individual impacts due to their larger mass. As the diameter decreases to 4 mm, the individual mass drops significantly (reducing impact intensity), yet the increase in particle count is not sufficient to trigger a fully fluidized state. Furthermore, given the cavity depth of 18 mm, the 4 mm particles are prone to forming stable semi-rigid structures (structural locking or arching) within the confined space, which restricts the relative motion and suppresses energy dissipation. In contrast, as the diameter further decreases to 3 mm and 2 mm, the particle bed enters a ‘fluid-like’ regime where the exponential increase in collision frequency overwhelms the loss of individual mass, leading to a surge in total energy dissipation. Under the prescribed spatial constraints, the 2 mm diameter exhibits decisive superiority in energy attenuation and is therefore identified as the optimal parameter for subsequent damper refinement.

Figure 2.

Energy dissipation of different particle diameter.

Table 2.

Particle diameter energy dissipation.

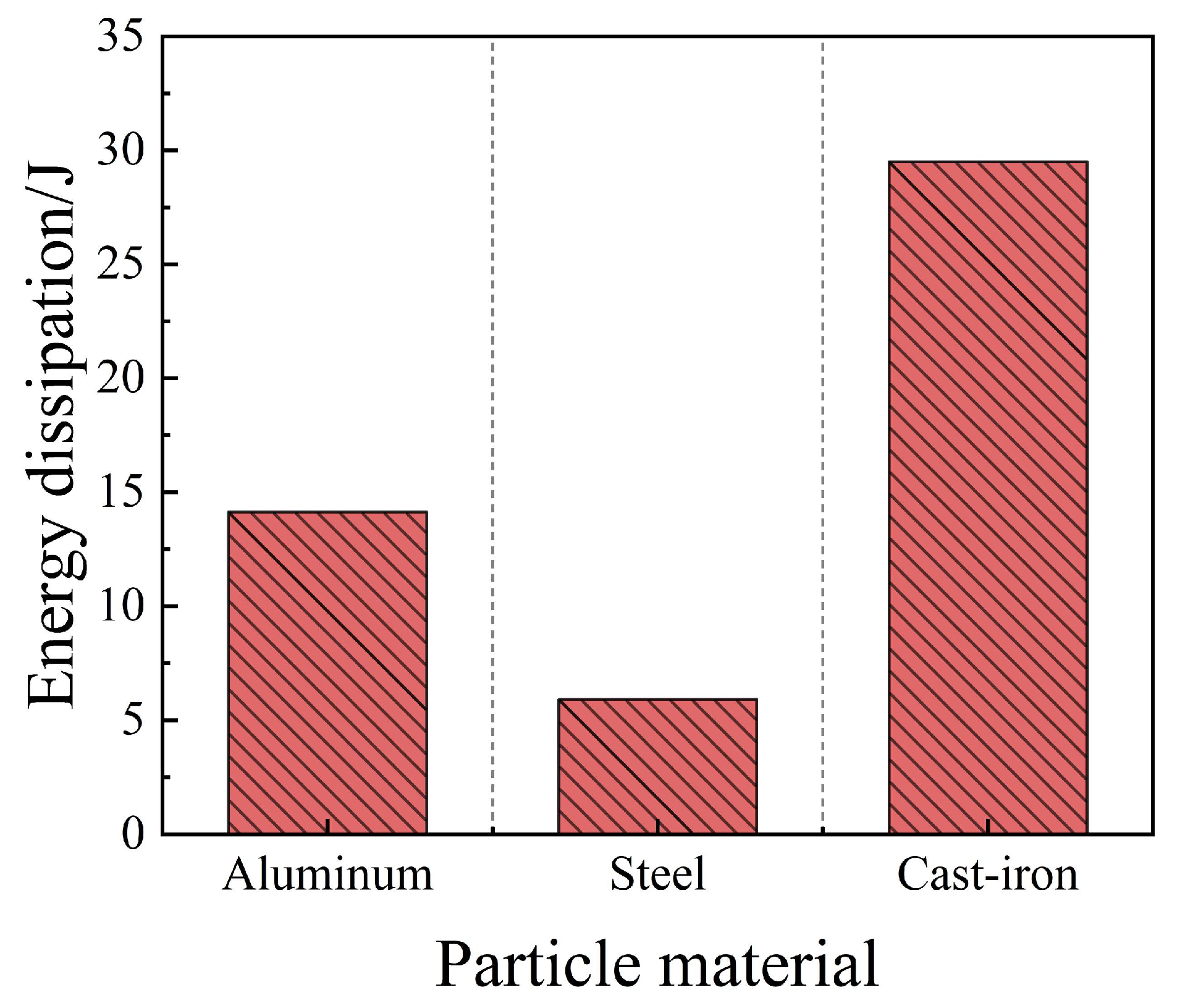

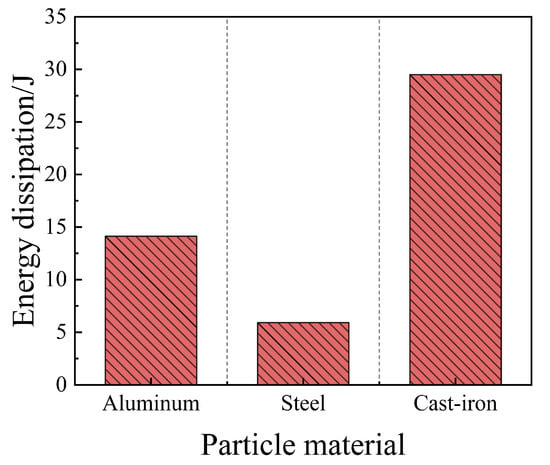

5.2. Selection of Particle Material for Particle Dampers

Material selection is a critical determinant of particle damper performance, as intrinsic properties—such as density, elastic modulus, and friction coefficients—profoundly influence the dissipative capacity of the system. To isolate the effects of material composition, this section evaluates three distinct media: steel, aluminum, and cast-iron spheres. Simulations were conducted using a 2 mm particle diameter at a 95% filling ratio under a sustained 100 Hz harmonic excitation.

As illustrated in Figure 3, the energy dissipation characteristics exhibit significant material-dependent variability. Under identical boundary conditions, cast-iron particles demonstrate the highest damping efficacy (29.497 J), followed by aluminum, while steel particles yield the lowest dissipation rates. This hierarchy is inherently linked to the constitutive behavior of the materials. Specifically, materials with a lower elastic modulus are more susceptible to transient deformation, which enhances energy attenuation through prolonged contact durations and potentially localized plastic work. Conversely, the high stiffness of steel favors elastic deformation dominated by elastic hysteresis, a mechanism that is comparatively less efficient in this granular context. Furthermore, the specific density and surface morphology of cast iron likely facilitate more robust momentum transfer and intensified interfacial friction, collectively maximizing energy loss during stochastic collisions.

Figure 3.

Energy dissipation of different particle materials.

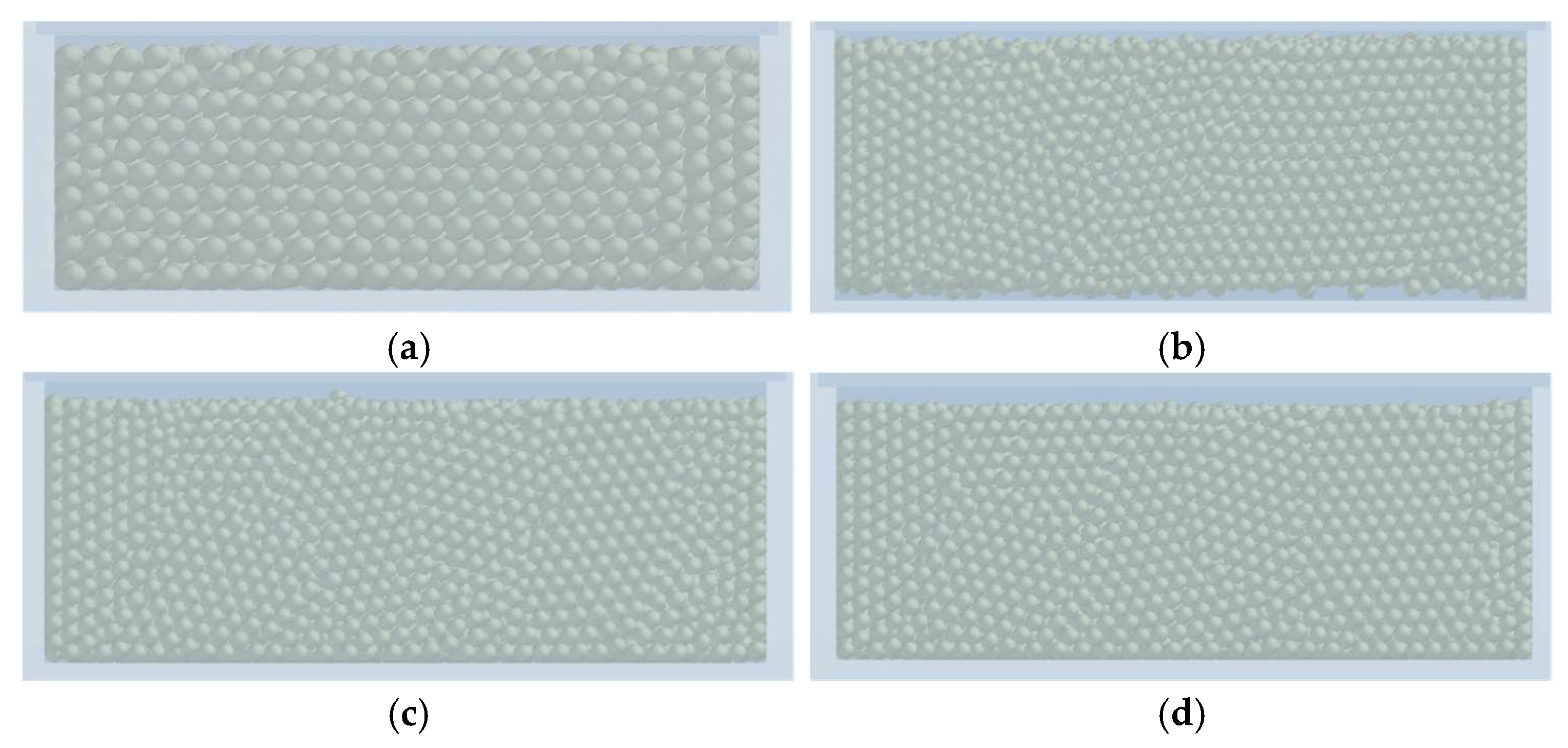

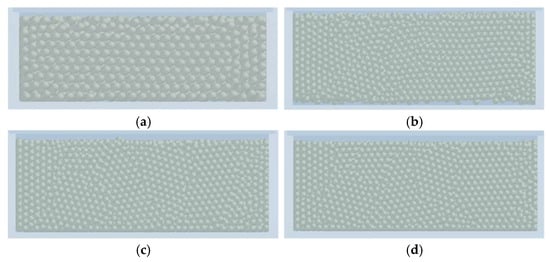

5.3. Selection of Particle Filling Rate for Particle Dampers

The filling ratio serves as a pivotal design parameter, as it modulates the internal granular dynamics—including flow regimes, collisional frequency, and frictional interactions—that govern the damper’s dissipative pathways. Consequently, it exerts a decisive influence on the overall vibration attenuation efficacy. To systematically evaluate this sensitivity, numerical experiments were executed across four discrete filling ratios: 90%, 95%, 98%, and 99% (modeled in Figure 4), utilizing the optimized 2 mm cast-iron particles. Following the DEM simulations, EDEM’s post-processing suite was leveraged to quantify the energy dissipation derived from inter-particle interactions. The resulting dissipation profiles facilitate a comprehensive comparative and quantitative assessment, delineating the functional relationship between filling density and energy attenuation performance.

Figure 4.

Energy dissipation model of different particle filling rate. (a) represents a 90% fill rate; (b) represents a 95% fill rate; (c) represents a 98% fill rate; (d) represents a 99% fill rate.

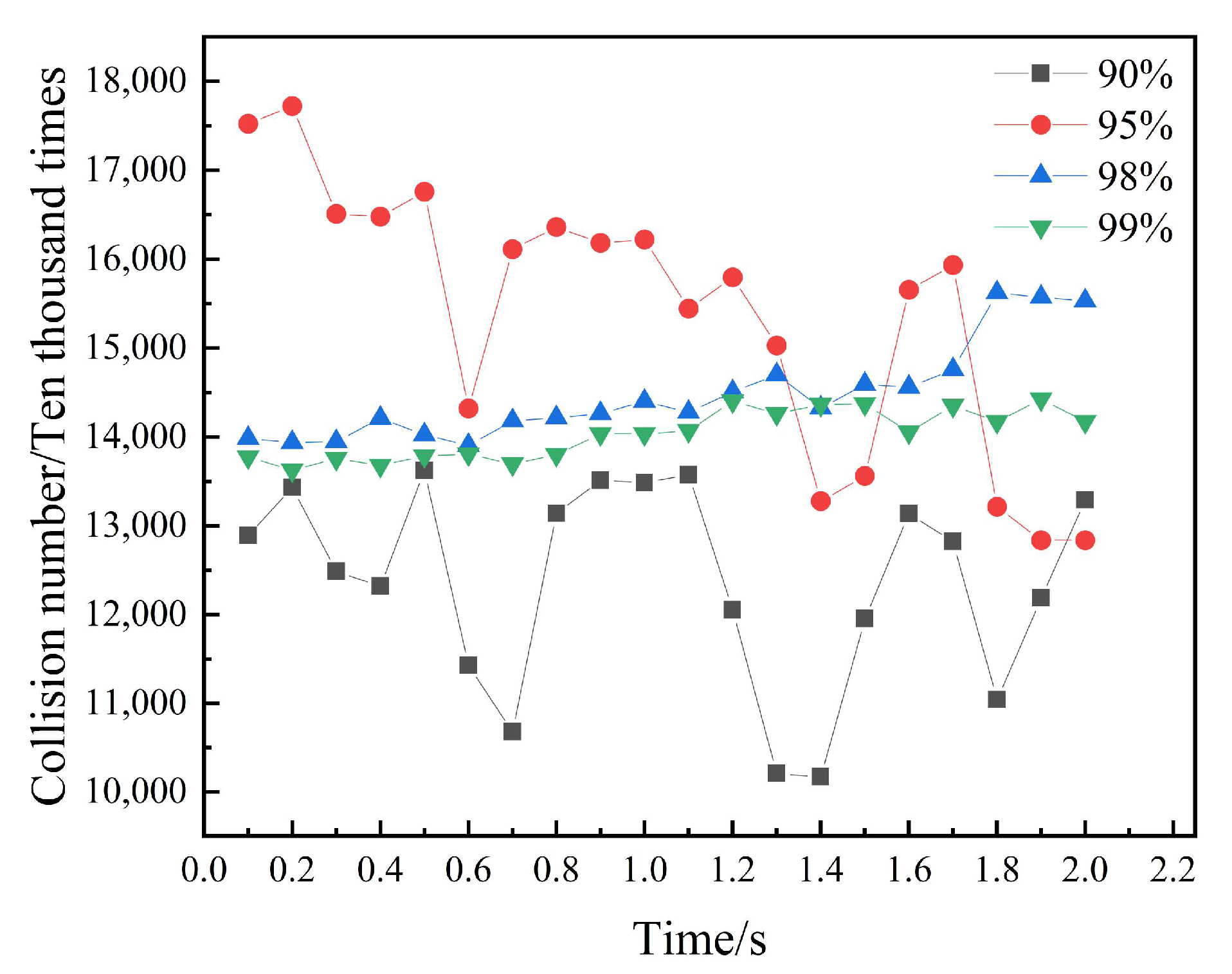

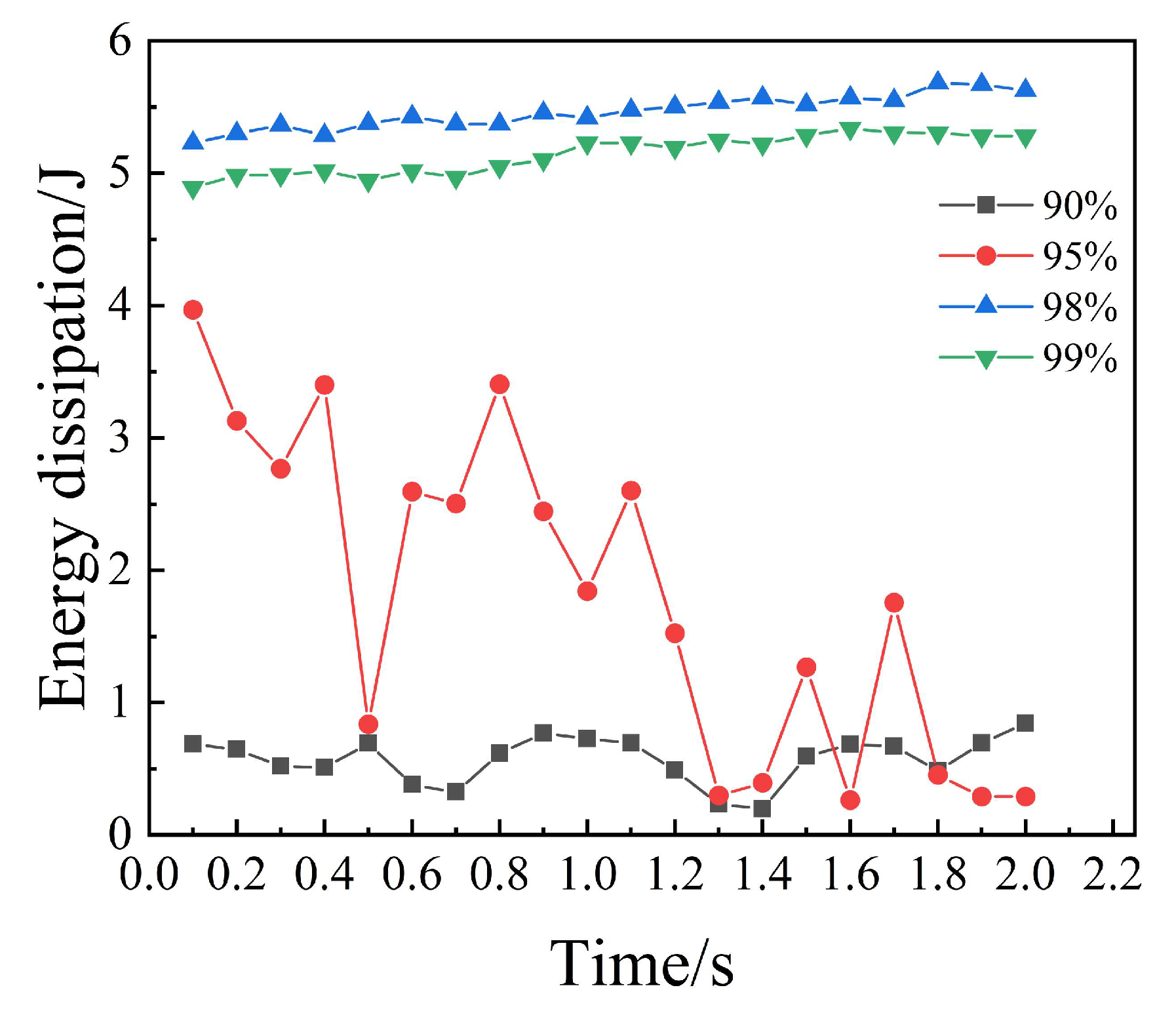

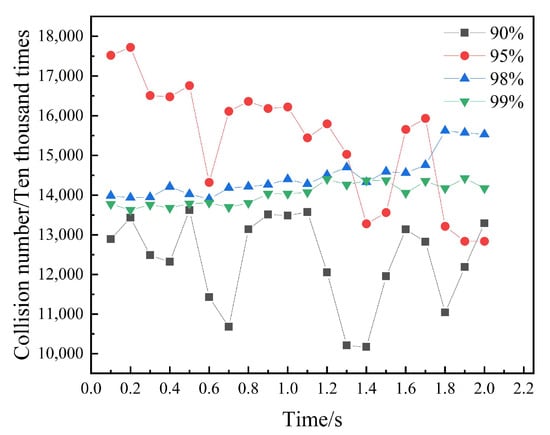

As evidenced by the collision frequency profiles (Figure 5) and summarized data (Table 3), the average particle collision count exhibits a non-linear response to the filling ratio. Specifically, the count surges from 12.48 million at a 90% ratio to a peak of 15.47 million at 95%, suggesting that moderate compaction facilitates intensified interfacial interactions. However, further densification to 98% and 99% results in a decline to 14.43 million and 14.00 million, respectively. This trend indicates that excessively high filling ratios—exceeding 95%—constrain the mean free path of the particles, inducing a transition toward quasi-solid or ‘jammed’ behavior that suppresses overall collisional activity.

Figure 5.

The number of collisions of particles with different filling rates.

Table 3.

Energy dissipation value and collision times of particles with different filling rates.

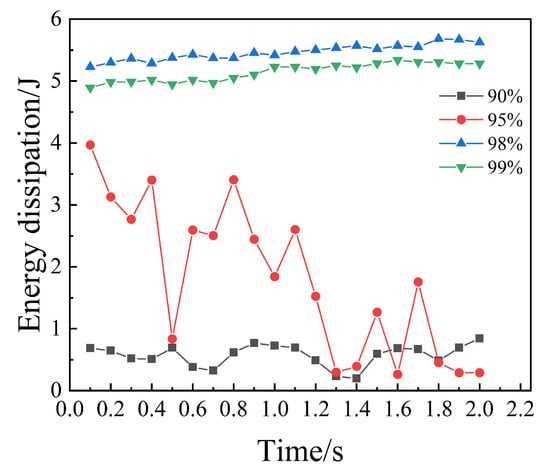

The energy dissipation profiles (Figure 6 and Table 3) further delineate this relationship: at 90%, energy attenuation is minimal due to excessive inter-particle spacing, which hampers efficient kinetic energy transfer. At 95%, the dissipated energy increases by approximately 3.3-fold relative to the 90% baseline, as optimized packing significantly bolsters the contribution of friction and inelastic impacts. The global optimum occurs at a 98% filling ratio, where energy dissipation peaks at 57.251 J. This value is 9.3 times greater than that at 90% and 2.8 times greater than that at 95%. This peak performance is attributed to the high-density packing which promotes a regime dominated by high-frequency micro-collisions and persistent frictional contact. Beyond this threshold, at 99%, dissipation slightly diminishes to 53.839 J (a 6% drop from the peak), as over-packing restricts the mobilization of particle kinetic energy. These findings strongly corroborate the theoretical framework proposed by Xiao [33].

Figure 6.

Energy dissipation of different filling rate.

5.4. Effect of Variable Cavities on Particle Damper Performance

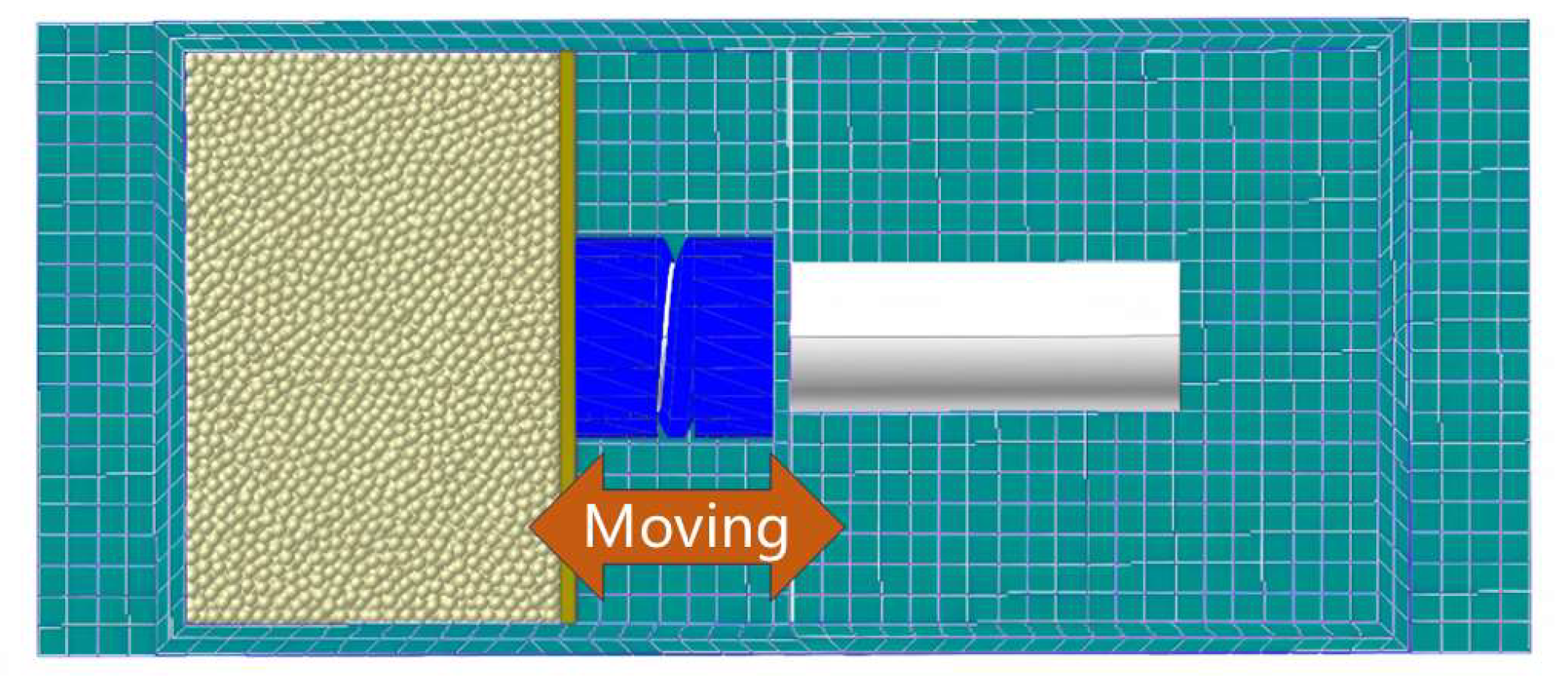

This section investigates the dynamic evolution of energy dissipation as the damper cavity transitions from a static to a variable-volume configuration through the integration of a compliant spring. Since EDEM is natively optimized for rigid-body dynamics and lacks the constitutive models for flexible spring mechanics, a RecurDyn–EDEM co-simulation framework was implemented. This bidirectional coupling ensures a high-fidelity resolution of the intricate interplay between the oscillating chamber boundaries and the granular media.

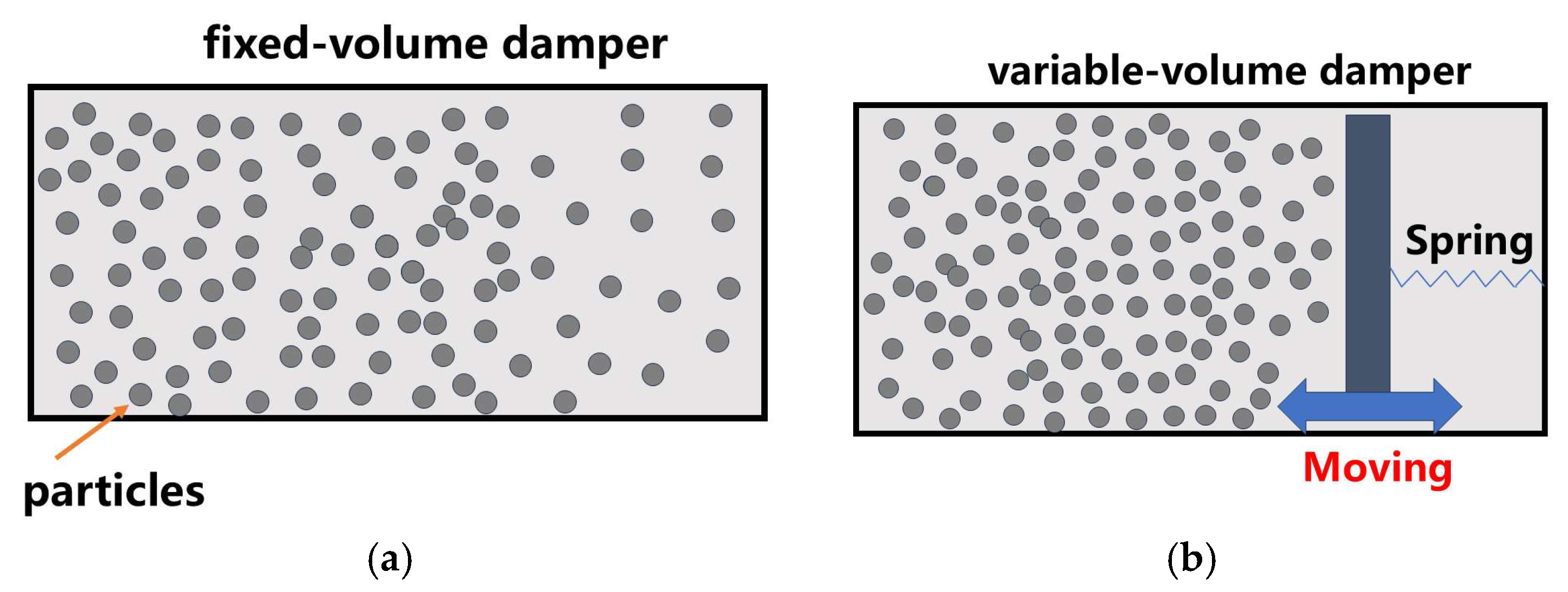

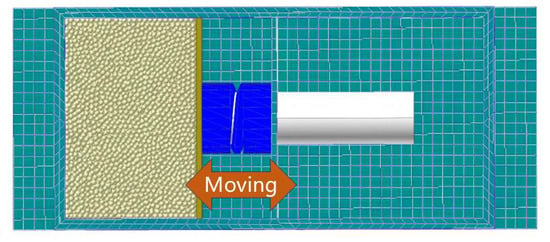

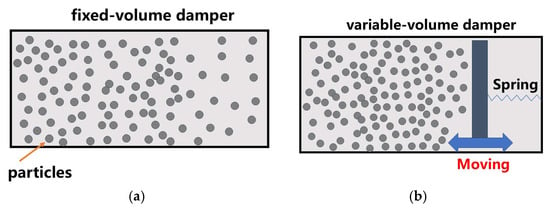

To investigate the effect of the variable cavity, two distinct configurations are defined and modeled, as illustrated in Figure 7 and Figure 8: Configuration 1 (Fixed Cavity): The sliding plate is rigidly fixed to the housing, simulating a traditional particle damper with a constant cavity volume. Configuration 2 (Variable Cavity): The sliding plate is connected via a compression spring, allowing the cavity volume to self-adaptively change in response to excitation.

Figure 7.

Variable cabin dissipation model.

Figure 8.

Schematic comparison of the two damper configurations. (a) Configuration 1: fixed-volume damper; (b) Configuration 2: variable-volume damper.

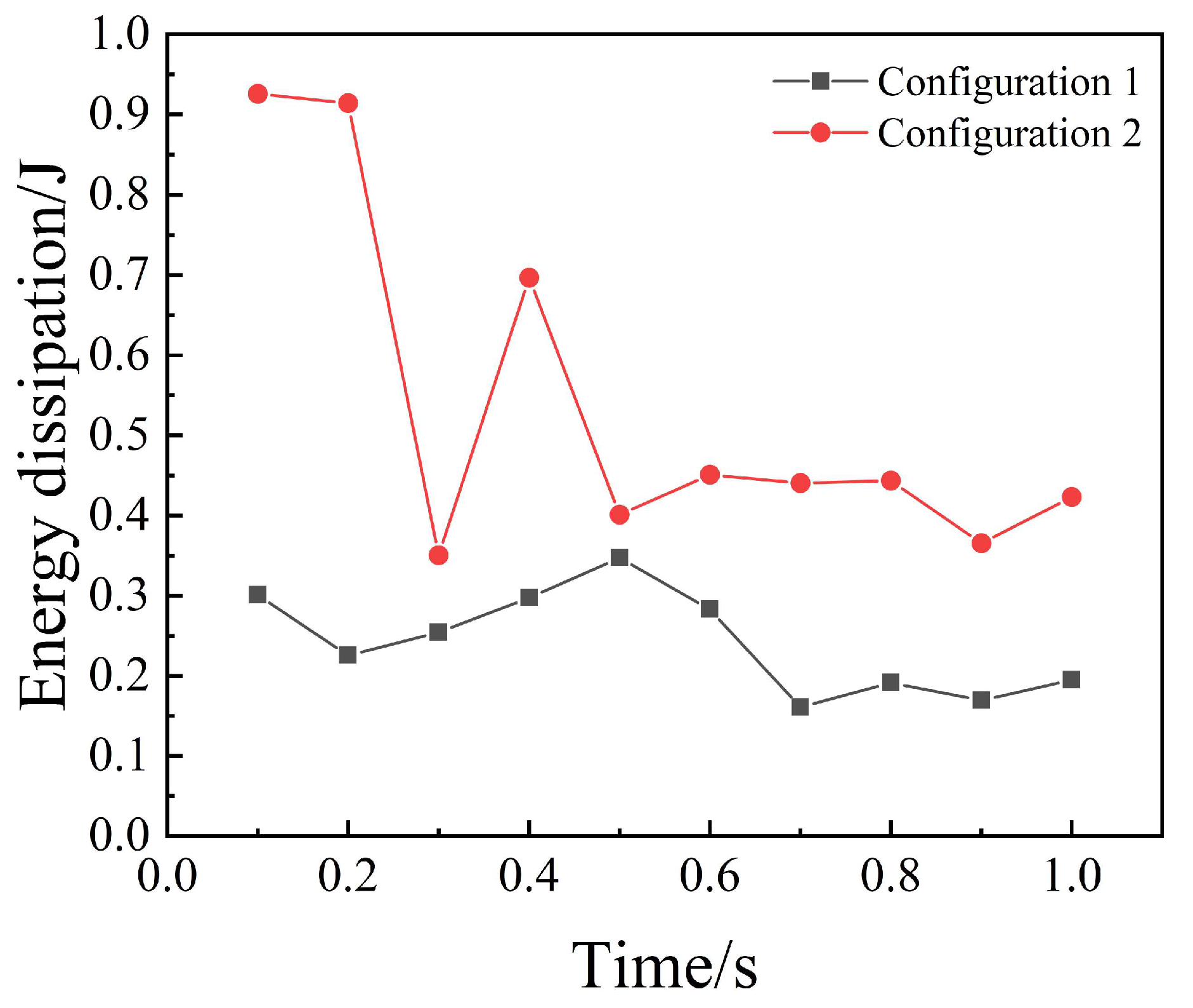

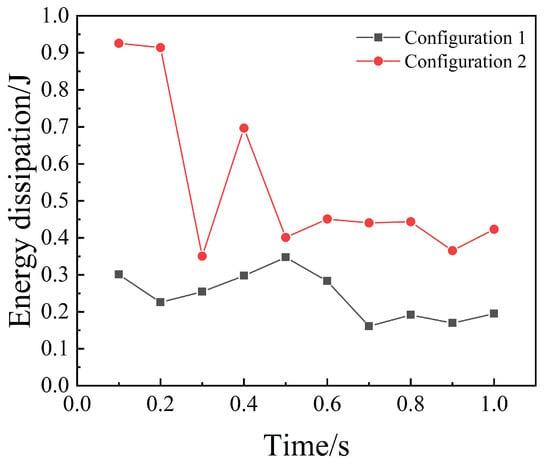

The dynamic responses of these two configurations are outlined in Figure 9, which compares the temporal dissipation profiles for the conventional fixed-volume damper (Config. 1) and the proposed variable-volume design (Configuration 2). The results reveal that the spring-integrated architecture significantly alters the system’s performance. Initially, Configuration 2 exhibits a sharper dissipation gradient, suggesting that the dynamic volume modulation more effectively invigorates stochastic particle motion. Furthermore, after reaching its peak, Configuration 2 demonstrates a more sustained decay profile. After reaching a steady state, the particle energy dissipation in Configuration 2 is concentrated within the range of 0.45 to 0.5, whereas in Configuration 1, it is primarily between 0.15 and 0.2.

Figure 9.

The introduction of spring components energy dissipation.

The non-stationarity of the energy dissipation process shown in Figure 9 is physically governed by distinct time-dependent components in the two configurations.

For Configuration 1 (fixed cavity), the relevant time-dependent process is the transient settling of the particle bed. As time t progresses, particles gradually lose kinetic energy due to friction and gravity, evolving from a chaotic fluid-like state to a jammed solid-like structure. Consequently, the energy dissipation E(t) exhibits a monotonic decay over time.

In contrast, for Configuration 2 (variable cavity), the dominant time-dependent component is the instantaneous velocity of the spring-loaded sliding plate, vp(t). Unlike a static wall, the sliding plate performs a continuous oscillation driven by the spring, meaning the boundary condition itself is a function of time (x (t)). This oscillating boundary acts as a ‘pump’, where the magnitude of energy dissipation correlates directly with the plate’s time-varying velocity. This dynamic coupling prevents particle settling and sustains the fluctuations (non-stationarity) observed in the energy curve, as the system constantly exchanges potential and kinetic energy over time. This indicates that the continuous boundary perturbations prevent the premature kinetic stagnation or ‘settling’ often observed in fixed-volume cavities, thereby maintaining high dissipation efficacy over an extended duration.

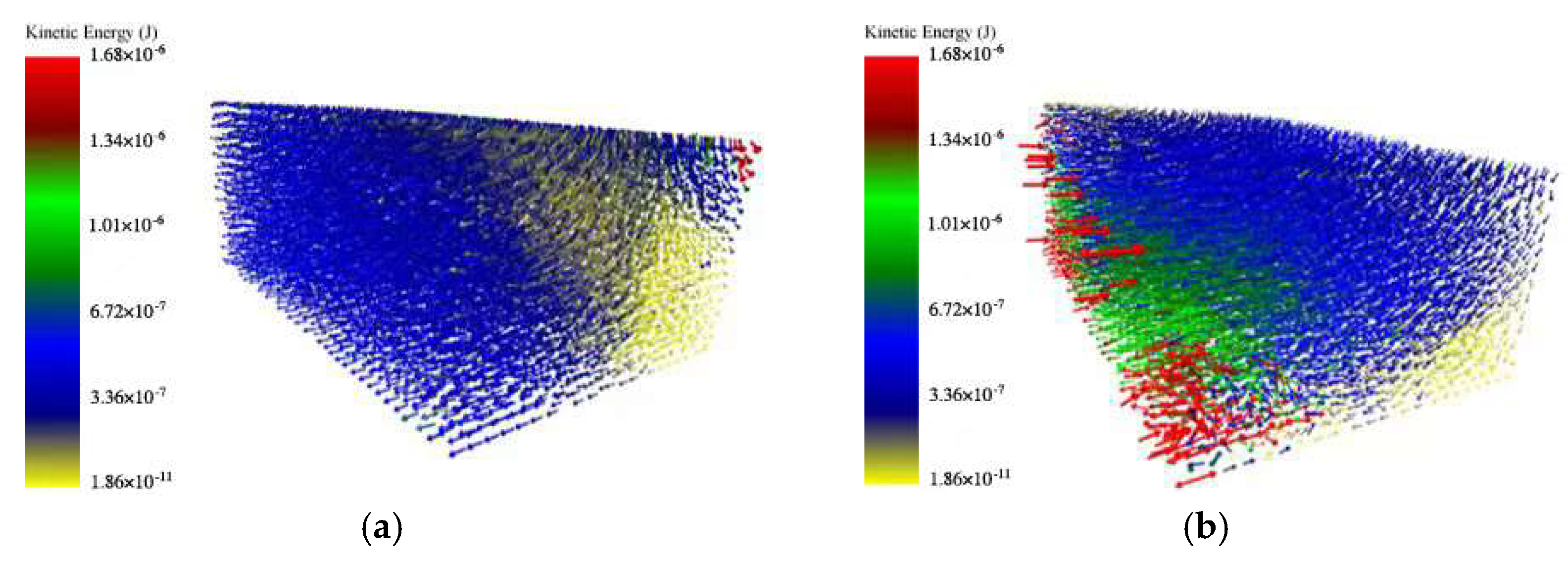

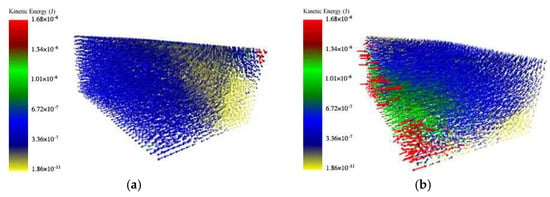

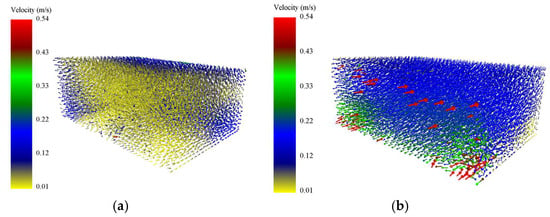

The kinetic energy distributions (Figure 10) further elucidate the dissipative superiority of the proposed design. In Configuration 1 (fixed-volume), the majority of particles occupy low-energy states within a narrow distribution, signifying constrained mobility and insufficient collisional intensity. In contrast, Configuration 2 (variable-volume) exhibits a significantly broadened energy spectrum with a higher population of particles reaching elevated energy levels. This stratified distribution reflects a more vigorous dynamic regime characterized by frequent and high-intensity inter-particle interactions. By facilitating adaptive volumetric fluctuations, the spring mechanism effectively recruits a larger fraction of the granular bed into high-energy collisional and frictional processes, thereby extending the suppression bandwidth.

Figure 10.

Kinetic energy diagram of particle damper. (a) represents the kinetic energy diagram for Configuration 1; (b) represents the kinetic energy diagram for Configuration 2.

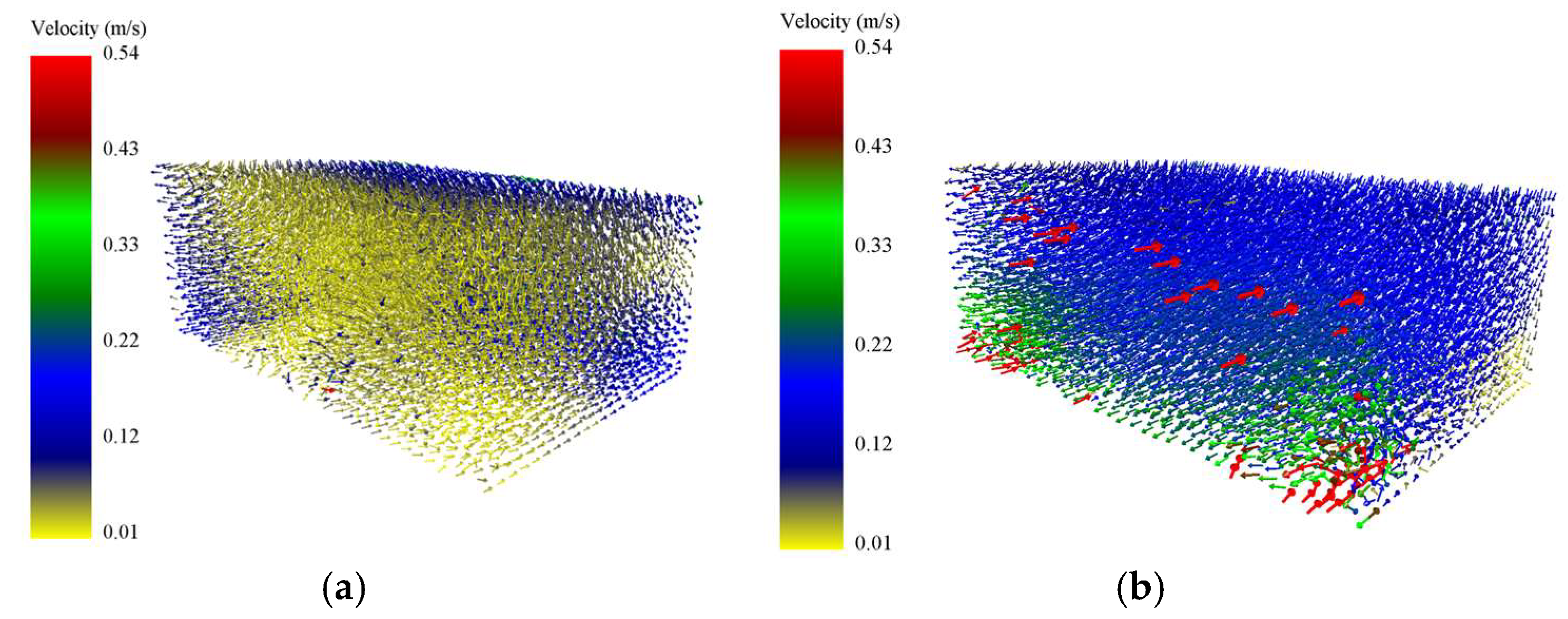

The velocity vector fields (Figure 11) provide further spatial evidence of this enhancement. In the fixed-cavity baseline, particle velocities remain predominantly low and stochastically scattered, suggesting localized stagnation and poor energy exchange. Conversely, Configuration 2 demonstrates not only higher velocity magnitudes but also enhanced vectorial coherence within the particle bed. The spring-governed boundary motion facilitates a more efficient momentum transfer from the housing to the granular medium, promoting synchronized high-velocity interactions.

Figure 11.

Particle damper velocity vector diagram. (a) Velocity vector diagram representing Configuration 1; (b) Velocity vector diagram representing Configuration 2.

The cumulative effect of these microscopic dynamics is evidenced by the substantially larger area under the dissipation curve for Configuration 2, indicating superior integrated energy attenuation. The inherent flexibility of the spring allows the cavity to undergo adaptive conformational changes in response to external excitation. This synergistic interplay between structural compliance and granular dynamics ensures that particle collisions are utilized more effectively, transforming a traditional passive damper into a high-performance, adaptive energy-dissipation system.

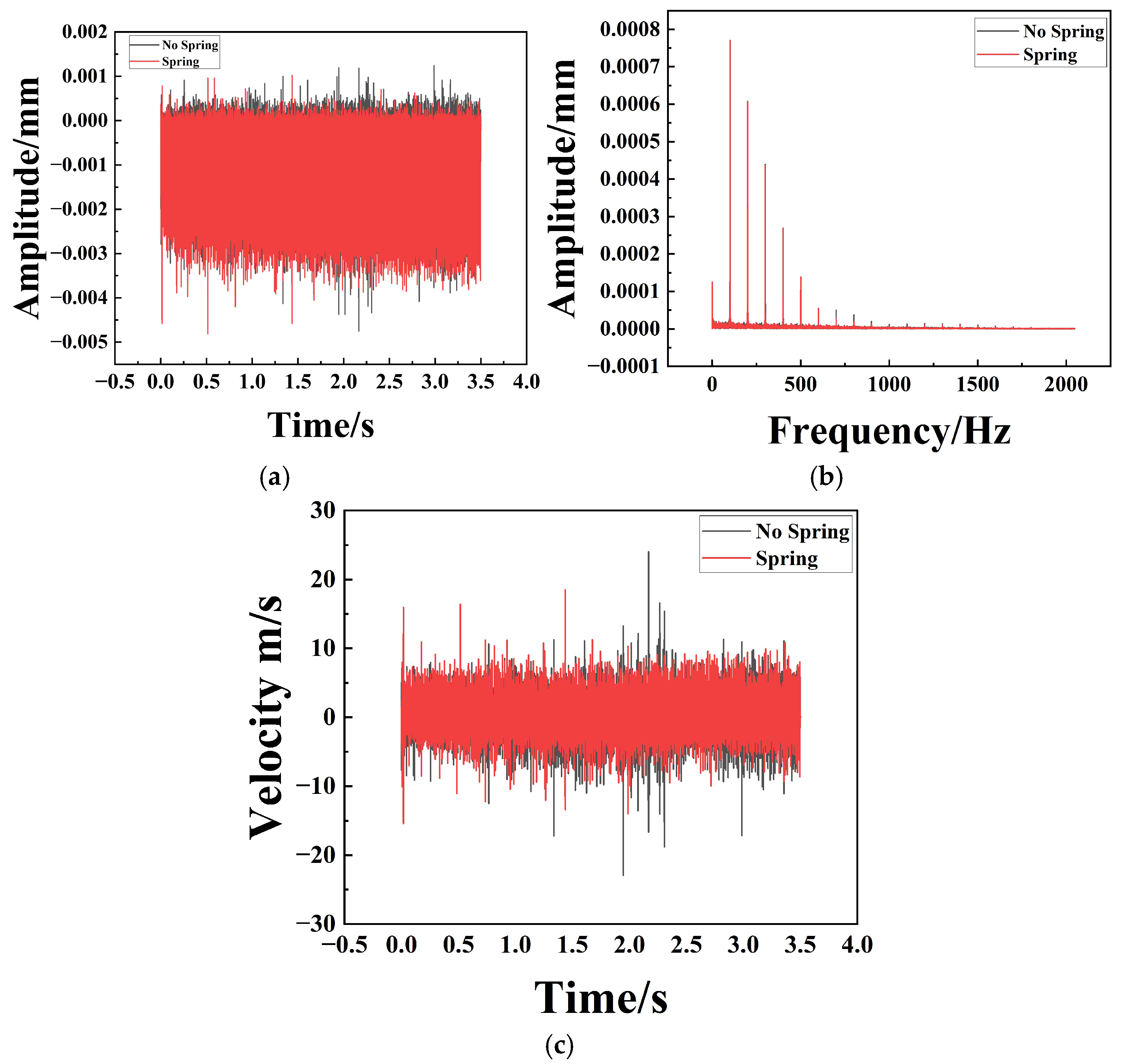

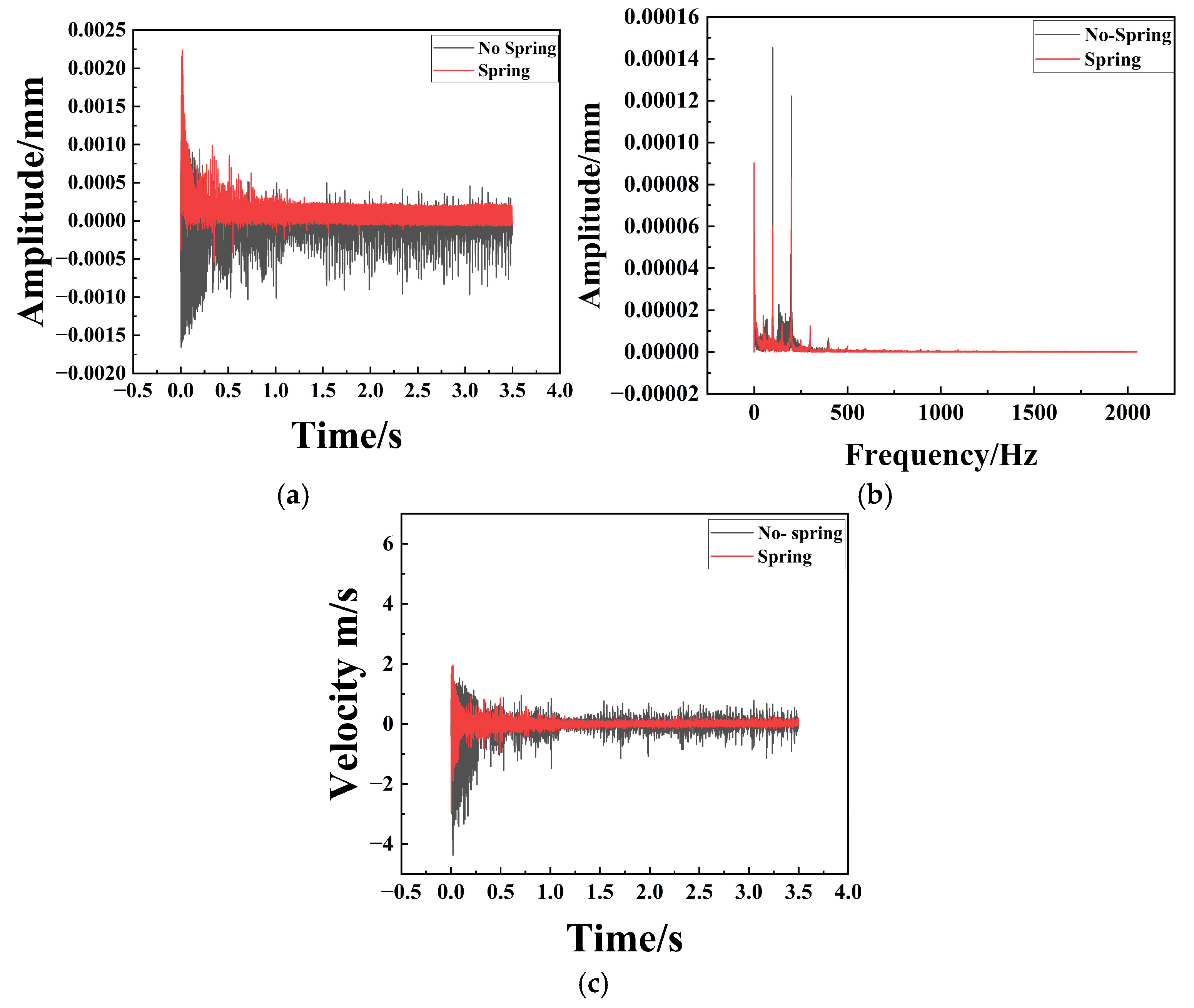

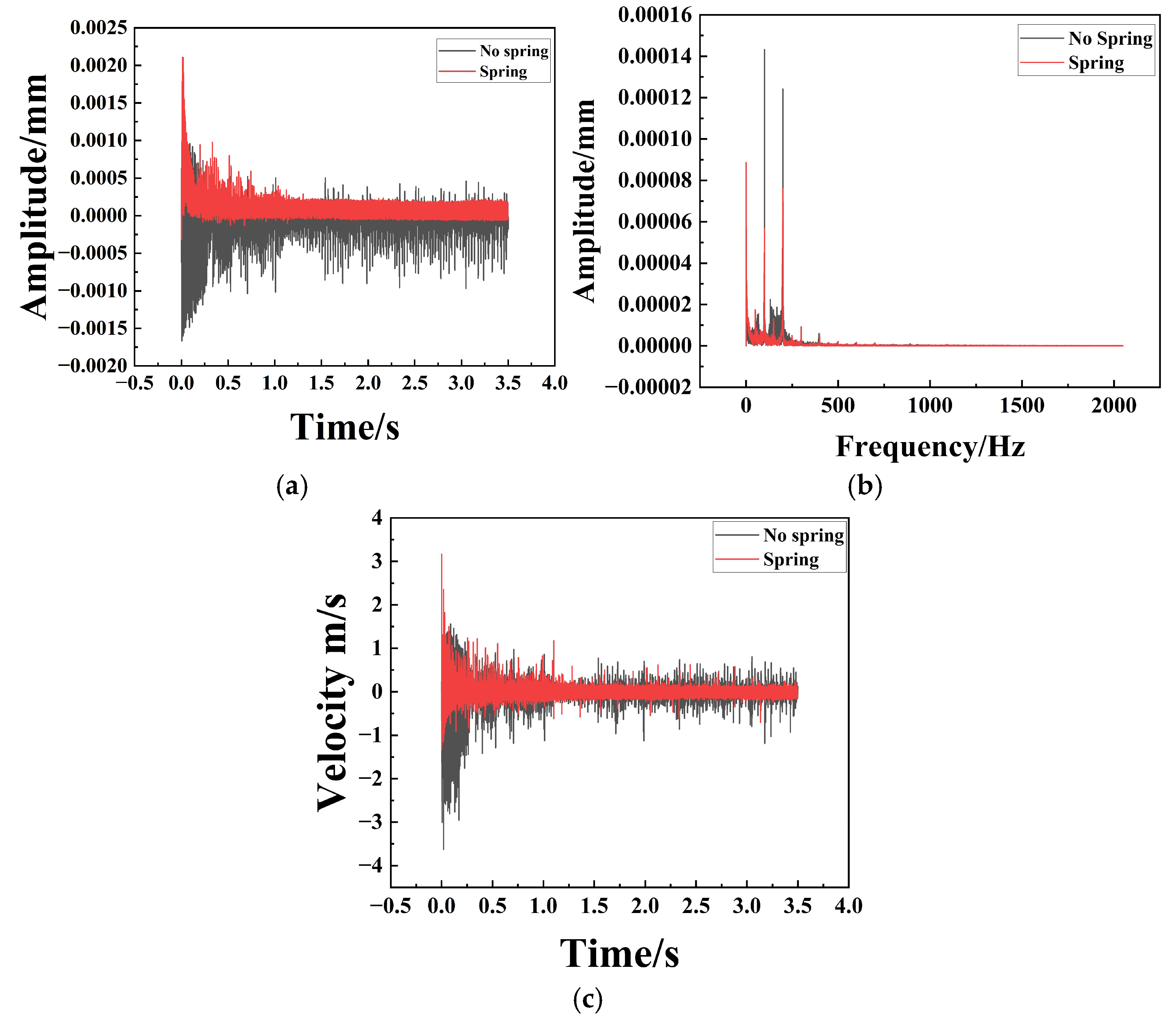

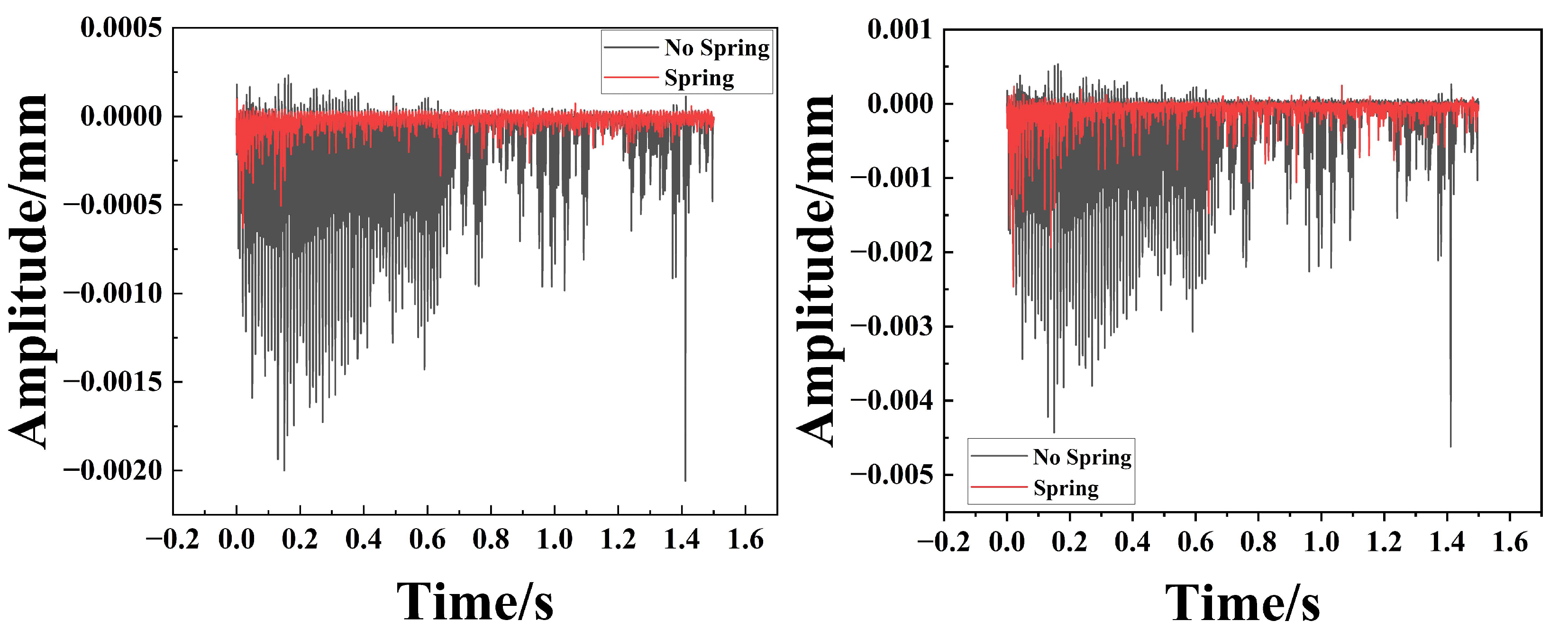

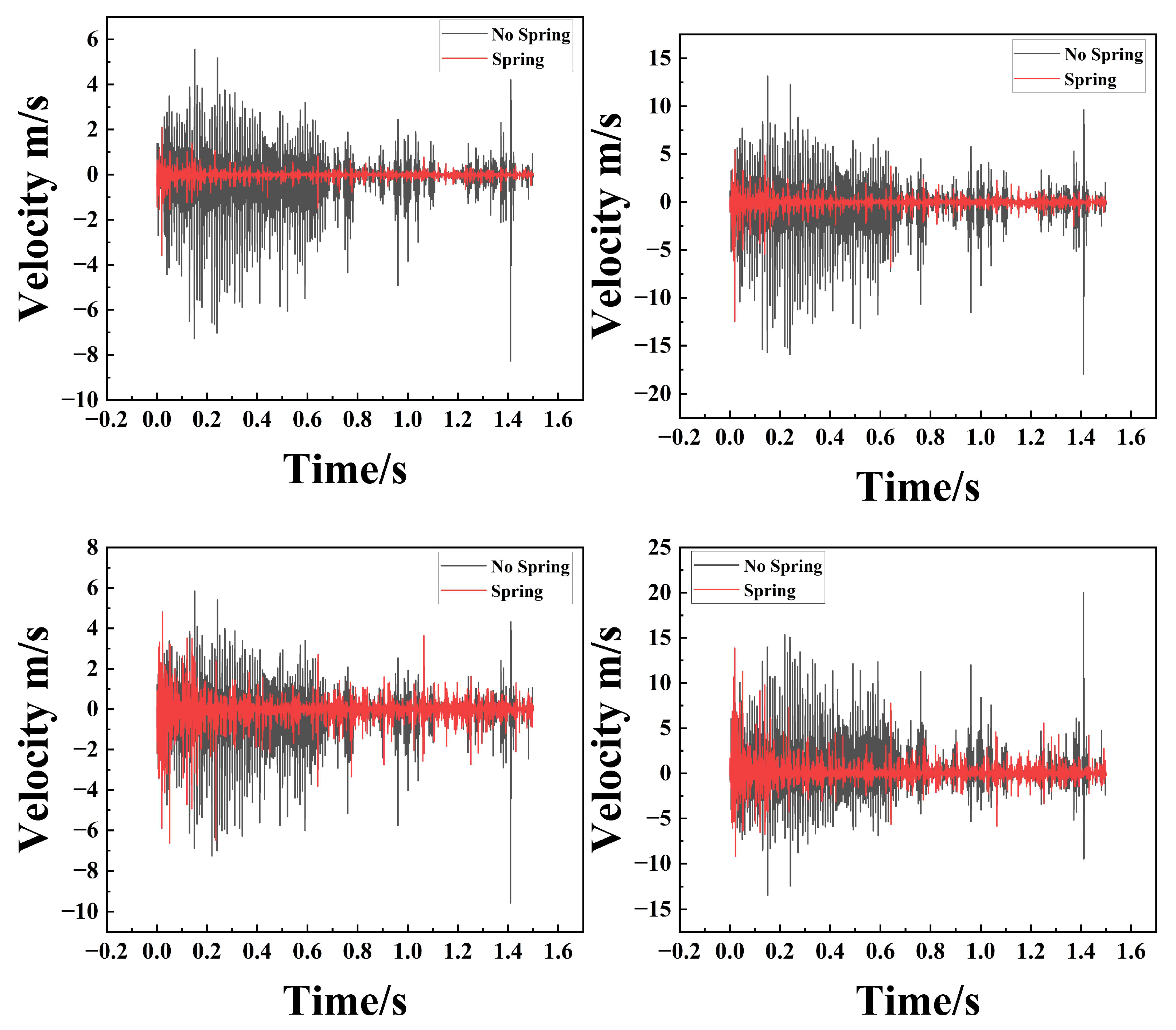

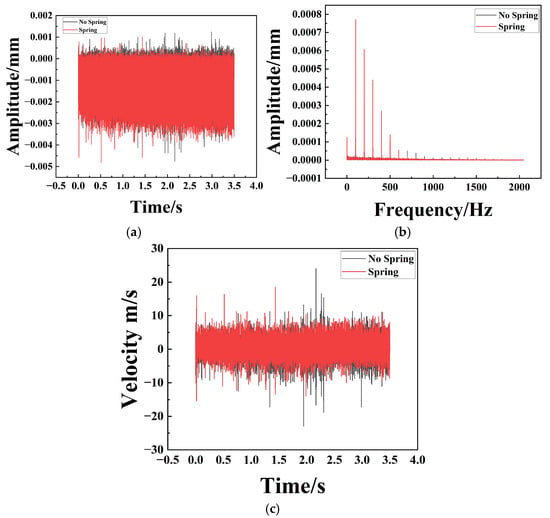

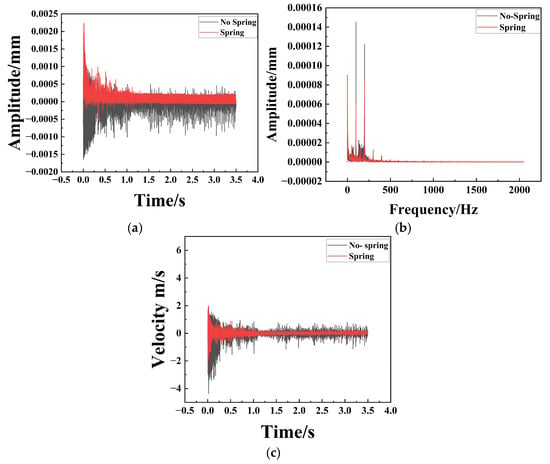

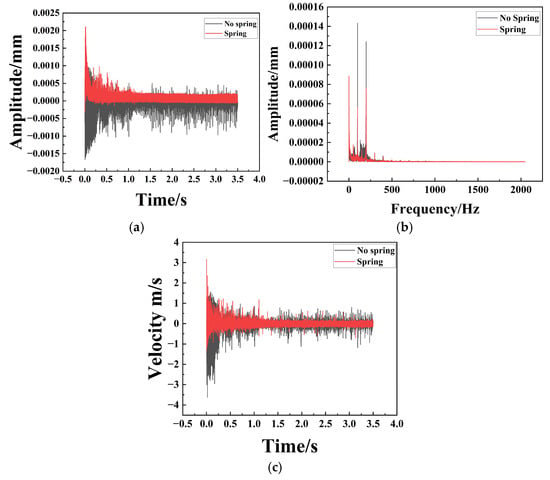

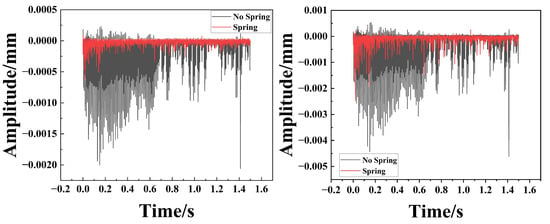

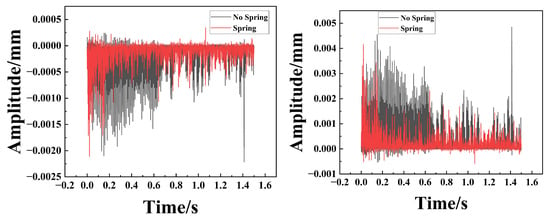

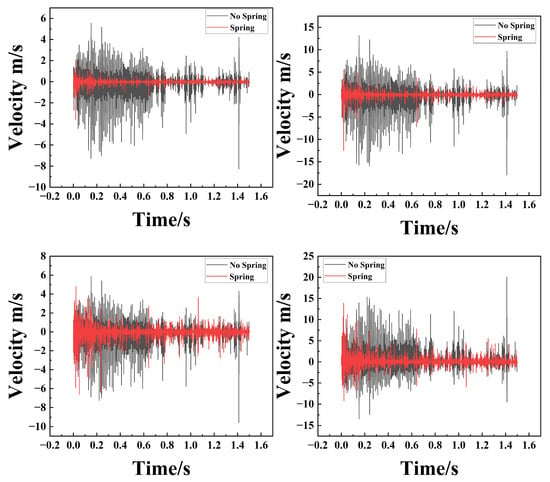

The dynamic response, characterized at the mounting base via RecurDyn, is presented in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14. These results provide a comparative assessment of the amplitude, frequency, and velocity profiles along the X, Y, and Z axes for both the un-sprung (baseline) and spring-augmented configurations. The analysis reveals that while vibration attenuation remains marginal along the longitudinal (X) axis, it is pronounced and statistically significant along the lateral (Y) and vertical (Z) axes.

Figure 12.

Comparison of X-axis Amplitude, Frequency, and Velocity for Particle Dampers with and without Spring Assemblies. (a) Represents the time–amplitude diagram; (b) Represents the frequency–amplitude diagram; (c) Represents the time–velocity diagram.

Figure 13.

Comparison of Y-axis Amplitude, Frequency, and Velocity for Particle Dampers with and without Spring Assemblies. (a) Represents the time–amplitude diagram; (b) Represents the frequency–amplitude diagram; (c) Represents the time–velocity diagram.

Figure 14.

Comparison of Z-axis Amplitude, Frequency, and Velocity for Particle Dampers with and without Spring Assemblies. (a) Represents the time–amplitude diagram; (b) Represents the frequency–amplitude diagram; (c) Represents the time–velocity diagram.

Spectral analysis (Figure 13b and Figure 14b) reveals that the system exhibits distinct multi-frequency response characteristics. This phenomenon is fundamentally attributed to the strong nonlinearity inherent in the particle damping system. Unlike linear viscous dampers, the energy dissipation in particle dampers relies on discontinuous inelastic collisions and Coulomb friction. These nonlinear interactions cause a transfer of vibrational energy from the fundamental excitation frequency to higher-order harmonics and broader frequency bands, manifesting as the multi-frequency peaks observed in the spectrum.

Furthermore, the coupling between the macroscopic motion of the spring-mass system and the microscopic stochastic motion of the granular media generates complex modulation sidebands. This mechanism not only broadens the frequency response range but also effectively ‘smears’ the resonance peaks, thereby preventing the concentration of vibrational energy at specific eigenfrequencies.

In the time domain (Figure 13 and Figure 14), the unspring configuration exhibits prolonged oscillatory decay, whereas the spring-equipped variant achieves rapid transient stabilization. Specifically, the unspring damper requires approximately 0.6 s to reach a steady velocity state, compared to only about 0.3 s for the spring design. This twofold reduction in settling time demonstrates a significantly enhanced effective damping ratio. The un-spring damper exhibits high-amplitude fluctuations during the initial transient phase, while the single-spring architecture yields a stable, low-variance response. Compared to the baseline design without springs, the spring particle damper exhibits a 50% lower operational amplitude, demonstrating a superior capacity for vibration attenuation. Mechanistically, the spring transforms the cavity into an adaptive, compliant environment that continuously energizes the granular medium. The resulting volumetric modulation increases the collisional flux and impact intensity, channeling vibrational energy into the efficient particle-based dissipation pathway. Consequently, the spring-incorporated design represents a sophisticated solution for achieving high-performance, rapid attenuation of both transient shocks and steady-state oscillations.

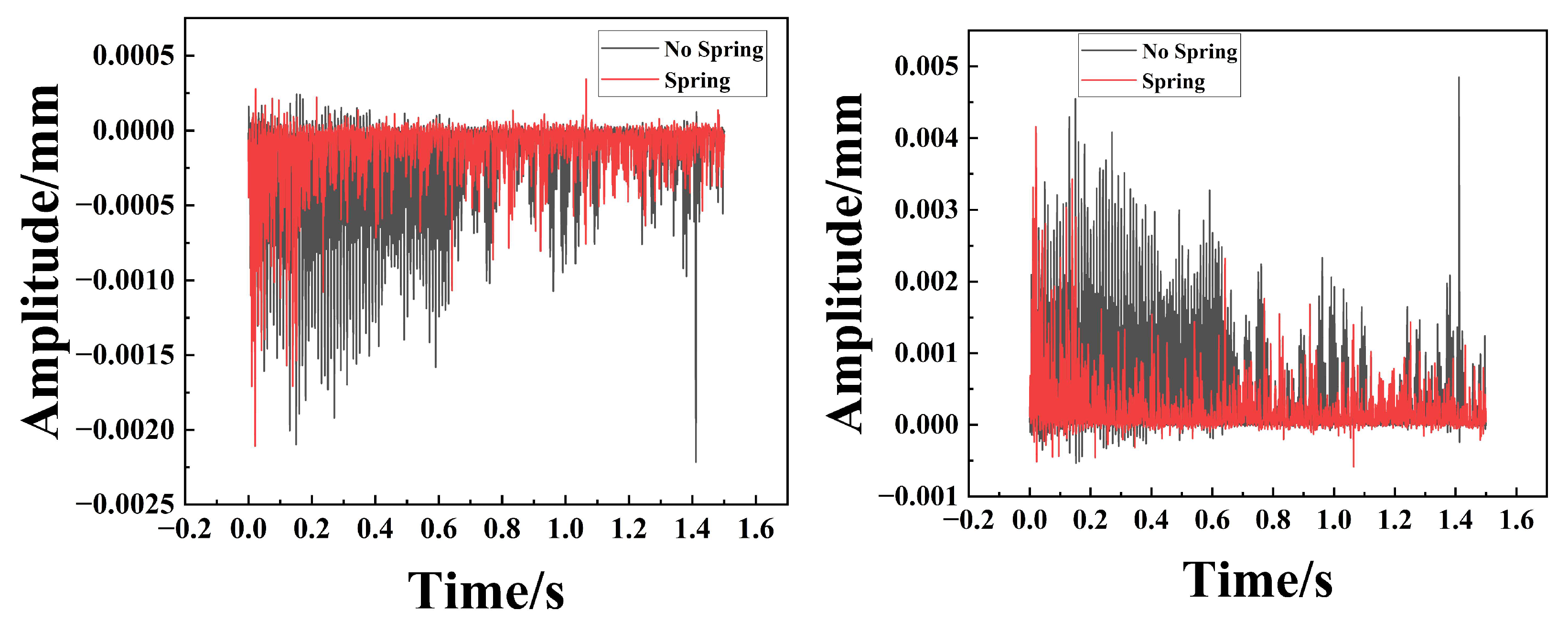

To quantitatively evaluate the reliability of the numerical simulations and verify the associated uncertainties, a systematic validation procedure was conducted.

First, to address model convergence, independence tests concerning time step and mesh size were performed, as illustrated in Figure 15. The results indicate that with refined calculation parameters, the amplitude decay curves remain highly consistent, exhibiting no significant numerical drift. This confirms that the numerical model satisfies convergence criteria, ensuring robust and reliable computational results. Furthermore, the particle damper equipped with a spring assembly consistently exhibited superior vibration attenuation performance compared to the non-spring configuration, thereby validating the model’s effectiveness.

Figure 15.

Comparison of Amplitudes for Different Parameters.

Second, accounting for the inherent stochasticity of the discrete particle system, multiple independent simulations were conducted under identical operating conditions to assess statistical uncertainty. As depicted in Figure 16, statistical analysis reveals minimal deviation in the velocity decay trends of the spring-equipped system. This demonstrates that the simulation results possess statistical significance and reliability, ruling out coincidental artifacts. Finally, comparative analysis indicates that the introduction of the spring component significantly reduces the settling time for both system amplitude and velocity from 0.6 s (in the non-spring configuration) to 0.3 s. This substantial reduction in stabilization time further validates the efficacy of the proposed design.

Figure 16.

Comparison of Speeds at Different Parameters.

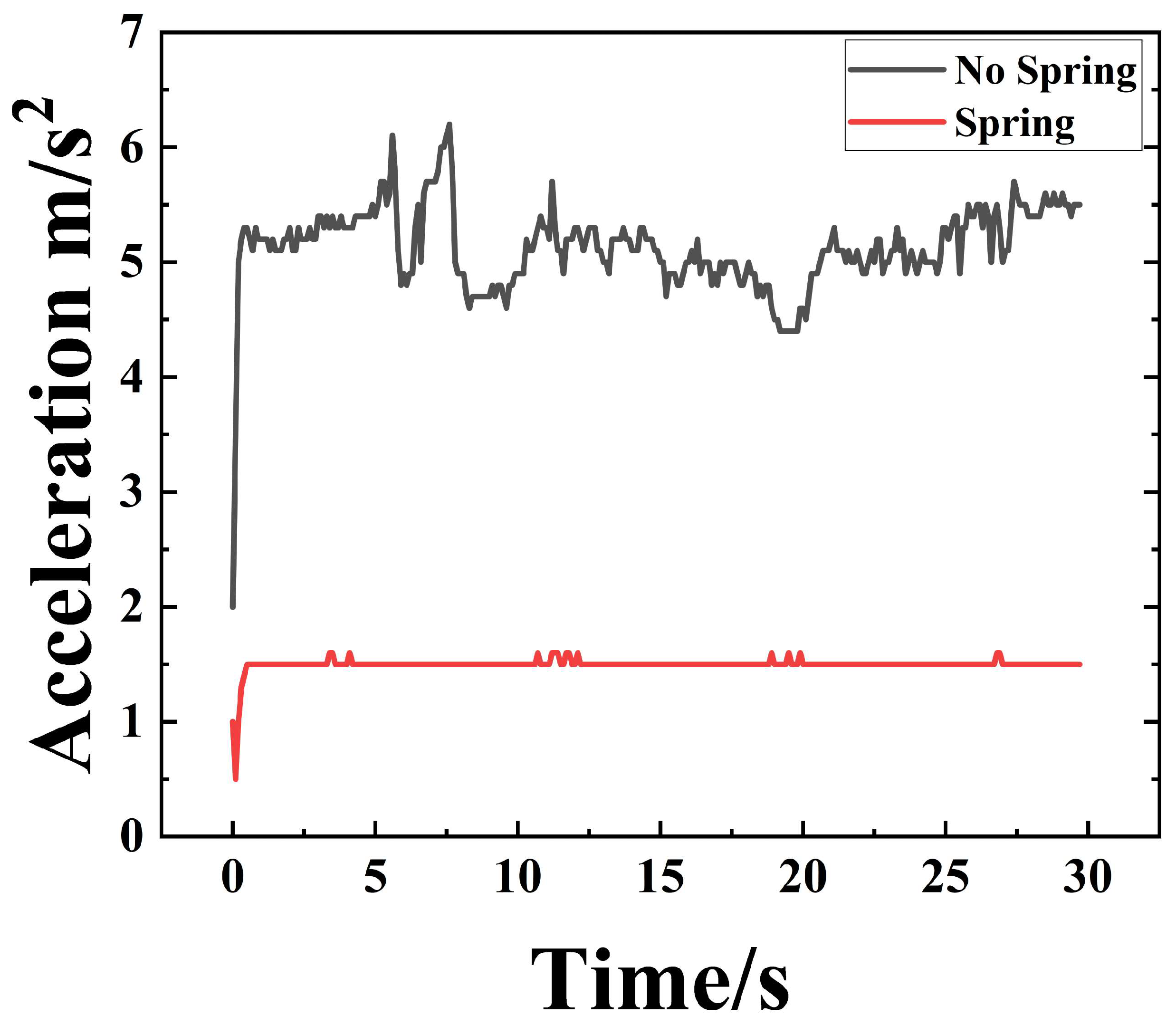

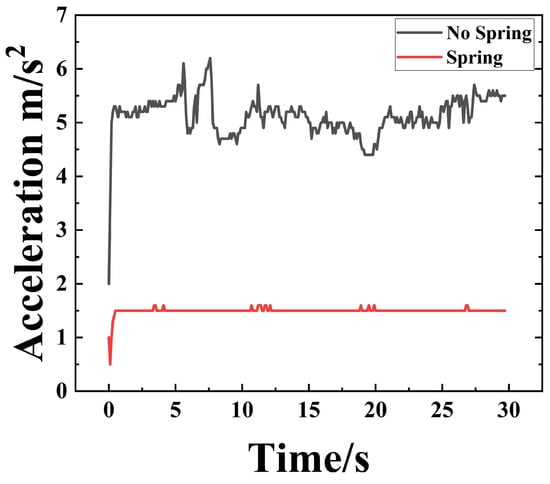

To validate the numerical simulation results and further investigate the dynamic performance of the granular damper with the added spring assembly, experimental testing was conducted. Two identical granular damper prototypes were fabricated: one without the spring assembly and another incorporating the proposed spring assembly. The same particle material type, particle size distribution, and packing density as in the simulations were maintained. Both configurations were tested under identical vibration inputs to elicit their full dynamic responses. The acceleration measurements for the two configurations are compared in Figure 17. The experimental results conclusively demonstrate that the spring-integrated design exhibits superior damping capabilities. The particle damper without the spring assembly exhibited sustained oscillatory decay and high-amplitude fluctuations, whereas the damper with the spring assembly rapidly decayed its acceleration response to steady-state levels. This significant reduction in operating acceleration amplitude confirms the vibration-damping effectiveness of the particle damper incorporating the spring assembly.

Figure 17.

Acceleration Comparison Chart.

Crucially, these dynamic characteristics directly translate into system-level performance enhancements regarding passenger comfort and structural durability. As evidenced in Figure 13a and Figure 14a, the spring-adaptive configuration reduces the vibration settling time by approximately compared to the fixed-cavity design. In high-speed rail operations, this rapid decay of transient shocks—induced by track irregularities or aerodynamic buffeting—is vital for improving ride comfort, as it minimizes the prolonged ‘after-shake’ sensation perceived by passengers. Furthermore, the spectral analysis indicates a significant suppression of high-frequency resonance peaks. By reducing the amplitude of these high-frequency stress cycles, the damper effectively lowers the cumulative fatigue damage accumulation on the sidewall structures. Therefore, the reduction in vibration amplitude and the increase in energy dissipation fundamentally protect the structural integrity of the car body and enhance the subjective experience of the passengers.

6. Discussion

This study proposes and validates a spring-adaptive cavity particle damper, designed to overcome the saturation and clogging issues inherent in traditional fixed-cavity dampers for vibration suppression in high-speed trains. This section situates the key findings within the broader scholarly context, clarifies their novelty and scientific value, and addresses potential concerns.

Compared to traditional fixed-cavity particle dampers, e.g., the optimized design for sidewall skins by Xiao et al. [25], the spring-adaptive mechanism introduced herein delivers enhanced performance. Simulation results indicate that the total energy dissipation for the variable-cavity design (Configuration 2) is approximately 2 times that of the fixed-cavity design (Configuration 1) shown in Figure 9. This enhancement does not stem from a simple increase in particle material or quantity but is attributed to the dynamic boundary conditions induced by the spring assembly. As noted by Lu et al. [7], the performance of conventional dampers is limited by particle “clogging”, leading to a sharp decline in energy dissipation efficiency after the transient response. The present design, by enabling reciprocating motion of the sliding plate via the spring, continuously perturbs the particle bed, effectively preventing stagnation shown in Figure 11. This maintains the particles in a highly efficient state of inelastic collisions and friction. This principle aligns with the concept of “activating” particle motion to enhance performance observed by Zhang et al. [27] in tuned particle dampers. However, our design achieves adaptive, continuous perturbation through passive mechanical coupling, offering greater practicality for engineering applications.

Regarding the optimization of key parameters, the findings of this study resonate with and deepen existing understanding. For instance, the optimal particle diameter selection (2 mm outperforming larger diameters) and the influence of particle material (cast iron > aluminum > steel) corroborate the dependence of particle damping performance on particle inertia (mass) and material dissipation properties. This study further quantifies this disparity: cast iron particles dissipate significantly more energy than steel particles. This pronounced gap can be attributed to the greater plastic deformation energy and inelastic dissipation generated by cast iron during collisions. Concerning filling ratio, this study reveals a non-monotonic optimal relationship, with a peak at 98% show in Figure 6. Our analysis suggests that filling ratios between 95% and 98% strike an optimal balance between particle free motion (collision frequency) and dense contact (frictional dissipation) show in Figure 5, Table 3. Exceeding 98%, excessive spatial confinement suppresses particle kinetic energy, leading to a slight performance decline (53.839 J at 99%).

The core innovation of this research lies in elucidating the synergistic mechanism between “structural compliance” and “nonlinear particle damping”. By employing a coupled DEM-MBD simulation approach [28], we deciphered how the spring-driven dynamic variation in cavity volume regulates the macroscopic particle motion state. As shown in Figure 10, the particle kinetic energy distribution under the variable-cavity design is broader, with more particles in a high-energy state. This indicates that the spring boundary acts like an “energy pump”, continuously injecting and dispersing external vibrational energy into the particle medium. This not only increases the instantaneous dissipation peak but, more crucially, extends the duration of high-efficiency dissipation show in Figure 9, addressing the rapid response decay of traditional dampers. This adaptive mechanism allows the damper to maintain high performance under broad-frequency excitation, e.g., wheel–rail impacts and aerodynamic loads encountered by high-speed trains [2], representing a shift from a “passive-fixed” to a “passive-adaptive” paradigm. Its scientific value lies in providing a novel pathway for designing highly efficient passive damping within constrained spaces.

It is important to acknowledge that the simulation results presented herein are based on a discrete excitation frequency (100 Hz). Particle damping is inherently a non-linear energy dissipation mechanism that exhibits strong frequency dependence. In traditional fixed-cavity dampers, the damping efficiency peaks only within a specific bandwidth where the particle motion resonates with the structural vibration (i.e., the ‘fluid-like’ state). Consequently, performance often degrades significantly when the excitation frequency shifts away from this optimal range.

While the single-frequency simulation simplifies the complex coupling dynamics to elucidate the fundamental mechanism, it represents a specific operational point. However, the spring-adaptive cavity design proposed in this study offers a potential solution to this frequency sensitivity. Unlike fixed-cavity dampers, the spring-loaded boundary introduces an additional degree of freedom. This allows the cavity volume to self-modulate in response to varying excitation intensities, thereby maintaining an active particle collision regime even when the external frequency might otherwise lead to particle stagnation or ‘jamming’ in a fixed cavity. Therefore, while the quantitative dissipation values are specific to the tested conditions, the qualitative mechanism suggests that the spring-adaptive damper holds superior general applicability and robustness for the broadband and random vibration environments typical of high-speed rail operations.

From an engineering application perspective, the findings have clear implications for improving ride comfort and structural durability in high-speed trains. Simulations demonstrate that the spring-adaptive design reduces the system settling time by approximately 50% (from 0.6 s to 0.3 s) and significantly attenuates vertical and lateral vibration amplitudes shown in Figure 13 and Figure 14. Faster transient decay means a substantial reduction in the passenger-perceived “after-shock” sensation caused by track irregularities, directly enhancing comfort. Concurrently, the suppression of high-frequency resonant peaks in the spectrum (Figure 13b and Figure 14b) helps reduce the high-frequency alternating stresses borne by critical structures like the car body sidewalls, thereby mitigating fatigue damage accumulation [1,11]. This aligns with the objective of Wang et al. [13] in applying particle damping to rail systems for vibration and noise reduction. However, our design, with its integrated and adaptive characteristics, is more suitable for direct deployment in space-limited areas within the car body.

It is important to note that the current study is primarily based on numerical simulation. Only a single acceleration comparison test was conducted to verify the performance of particle dampers with and without spring dampers. Although a validated Hertz–Mindlin contact model was employed and parameter sensitivity analyses were conducted, the conclusions necessitate further verification through subsequent experimental studies. Furthermore, simulations were performed under constant 100 Hz harmonic excitation. Future research should extend to broader frequency bands and random excitation spectra to comprehensively evaluate performance under realistic track excitation profiles. The spring stiffness (set to 100 in this study), as a critical design variable, likely requires optimization dependent on specific installation locations and primary structural frequencies, warranting further parametric investigation. Different amplitudes and frequencies could be applied to select a more suitable spring stiffness for given operational conditions. In numerical simulations, different vibration functions are incorporated according to various operating conditions, primarily by setting different spring stiffness values. The spring stiffness must both ensure the ability to drive the particles and maintain the adaptability of the particle chamber. Finally, the vibration reduction effects are analyzed by setting different observation points.

In summary, this work significantly advances the performance ceiling of particle dampers for high-speed train applications by introducing a spring-adaptive cavity. Its innovativeness lies not only in the specific structural design but, more fundamentally, in elucidating a universal mechanism whereby dynamic boundary conditions continuously energize the particle medium to sustain a high dissipation state. This paves the way for developing high-performance, compact passive damping solutions suitable for other transportation vehicles or precision instruments.

7. Conclusions

In this work, we have developed and validated an advanced variable-volume particle damping system that overcomes the inherent limitations of traditional passive dampers in high-speed rail applications. By synergizing the Discrete Element Method with Multi-Body Dynamics, we elucidated the complex energy-dissipation pathways of granular media within a compliant boundary.

Our findings reveal that the spring-governed volumetric modulation acts as a dynamic agitator, effectively ‘recruiting’ a larger fraction of the particle bed into high-energy collision regimes. This mechanism not only enhances the peak dissipation rate but also ensures sustained energy attenuation, preventing the rapid efficiency drop associated with particle settling in static cavities. The optimized 2 mm cast-iron configuration at a 98% filling ratio provides a decisive benchmark for high-performance damping.

Ultimately, this study proves that introducing structural flexibility into particle damping chambers can fundamentally alter the system’s dynamic characteristics, resulting in superior spectral flattening and accelerated transient decay. The particle damper with spring components achieves approximately 50% more amplitude attenuation than the traditional particle damper with a fixed chamber, and the settling time of velocity is shortened from 0.6 s to 0.3 s. This adaptive damping paradigm offers a promising solution for enhancing passenger comfort and structural integrity in the evolving landscape of global high-speed rail technology.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: R.W., X.C. and Z.H.; Computational Methods: R.W. and Z.H.; Numerical Simulation Analysis: R.W., X.C. and Z.H.; Data Processing: R.W. and Z.H.; Figure and Table Preparation: R.W., X.C. and Z.H.; Manuscript Drafting: R.W. and Z.H.; Manuscript Writing and Revision: R.W., X.C. and Z.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Program For Scientific Research Start-up Funds of Guangdong Ocean University (060302062312), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51275201), and Key Projects of Jilin Province Science and Technology Development Plan (20220201047GX).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sun, L.X.; Hu, X.Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, J.S.; Gong, D.; Wu, N. Research Status and Prospect on Service Safety of 400 km/h High-speed Train. China Railw. 2025, 6, 15–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Zeng, J.; Shi, H.; Jiang, X. Parameter optimization of multi-suspended equipment to suppress carbody vibration of high-speed railway vehicles: A comparative study. Int. J. Rail Transp. 2024, 12, 1000–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, S.Q.; Du, J.T. DSS Research on Aerodynamic Drag Reduction of Surface Microstructure of High-speed Maglev Train. Railw. Tech. Stand. (Chin. Engl.) 2023, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, M.M.; Anne, S.; Lu, F. An analysis of relation between China railways high-speed noises and velocities. J. Appl. Acoust. 2014, 33, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, R.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Q.; Wen, J. Hunting stability control of high-speed bogie based on active yaw damper. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control. 2024, 43, 1827–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.C.; Huang, X.; Zeng, J.; Wang, Q.S. Study on adaptive control strategy of hunting stability for high-speed trains. Mod. Manuf. Eng. 2025, 2, 61–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, Z.; Lu, X.L.; Yan, W.M. A survey of particle damping technology. J. Vib. Shock 2013, 32, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Z.; Mao, K.; Wei, S.; Wang, X.; Fang, Y.; Yang, S. Application of genetic algorithm-support vector regression model to predict damping of cantilever beam with particle damper. J. Low Freq. Noise Vib. Act. Control. 2017, 36, 138–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Wu, C.; Wu, H. A novel composite vibration control method using double-decked floating raft isolation system and particle damper. J. Vib. Control 2018, 24, 4407–4418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, X.; Wu, C. Investigating the optimal damping performance of a composite dynamic vibration absorber with particle damping. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2018, 6, 503–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, W.Q.; Ye, S.Z.; Wang, X.M.; Jia, S.S.; Pan, D.K.; Lu, D.J. Numerical Analysis and Experimental Study of Particle Dampers for Vibration Reduction of EMU End Wall Structures. China Mech. Eng. 2021, 32, 481–489. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.Q.; Chen, H.; Xu, Z.H.; Wang, X.M.; Jia, S.S.; Pan, D.K. Study on the Vibration Reduction of Internal Combustion EMU Powerpack Frame under Multiple Loading Conditions Based on Particle Damping. J. Mech. Eng. 2022, 58, 250–257. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.C.; Zhang, Y.B.; Fan, Y.X. Research on Vibration and Noise Reduction Effect of Particle Damping Absorbers for Track Systems. Noise Vib. Control 2022, 42, 220–224. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Wu, C.; Wu, H.; Wang, J.; Lei, X. Vibration isolation performance of nonobstructive particle damping in a machine rack. J. Vib. Control 2019, 25, 1122–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paget, A.L. Vibration in steam turbine buckets and damping by impacts. Engineering 1937, 143, 305–307. [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, P.; Jensen, D.P. An acceleration damper: Development, design, and some applications. Trans. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 1945, 67, 523–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masri, S.F. Analytical and experimental studies of multiple-unit impact dampers. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1969, 45, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalou, A.; Masri, S.F. Performance of particle dampers under random excitation. J. Vib. Acoust. 1996, 118, 614–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeki, M. Analytical study of multi-particle damping. J. Sound Vib. 2005, 281, 1133–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.A.; Semercigil, S.E. A beam like damper for attenuating transient vibrations of light strucvtures. J. Sound Vib. 1993, 164, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zeng, J.; Qu, S. Linear stability analysis of a high-speed rail vehicle concerning suspension parameters variation and active control. Veh. Syst. Dyn. 2023, 61, 2976–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, Y.X. Research of Vehicle Semi-Active Control Based on Improved ADD Control STRATEGY. Mech. Eng. Autom. 2023, 12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, D.; Peng, W.; Wang, R.; Li, J.; Guo, S. Optimal design of lightweight acoustic metamaterials for low-frequency noise and vibration control of high-speed train composite floor. Appl. Acoust. 2022, 199, 109041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.X.; Dong, Z.; Su, J.J. Influence of thickness distribution on the vibration characteristics of thin plates with variable thickness. J. Vib. Shock. 2022, 41, 289–297. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, W.Q.; Shao, B. Vibration reduction of side wall skin of high-speed EMU based on particle damping. J. Railw. Sci. Eng. 2023, 20, 3251–3261. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.M.; Shah, B.; Keer, L.M.; Wang, Q.J.; Snurr, R.Q. Particle dynamics simulations of a piston-based particle damper. Powder Technol. 2009, 189, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Xi, Y.; Chen, T.; Ma, Z. Experimental studies of tuned particle damper: Design and characterization. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 99, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhou, D.; Wang, Z.; Zhou, L.; Ma, H.; Zhao, Y. A parallel coupling framework for DEM-MBD: Model verification and application. Powder Technol. 2024, 448, 120257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin-Xiao, Y.E.; Zheng-Qi, Y.; Min, J.I.; Ying, J.M.; Lin-Chang, Y.E.; Zhao-Wang, X.I.A. Energy Dissipation Characteristics Analysis of Spring-particle Damper Vibration Control Systems. Noise Vib. Control 2025, 45, 74. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji, Y.; Tanaka, T.; Ishida, T. Lagrangian numerical simulation of plug flow of cohesionless particles in a horizontal pipe. Powder Technol. 1992, 71, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mindlin, R.D. Compliance of elastic bodies in contact. J. Appl. Mech. 1949, 16, 259–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warburton, G.B. Dynamics of structures. In Earthquake Engineering & Structural Dynamics; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995; Volume 24, pp. 457–462. ISBN 0-07-011394-7. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, Y.N.; Dai, Y.; Xiao, W.Q.; Shao, K. Vibration and Noise Reduction Design for High-Speed Rail Interior Wood Flooring Based on Particle Damping. Electr. Transm. Locomot. 2024, 1, 85–92. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.