Abstract

Music conveys emotion through a complex interplay of structural and acoustic cues, yet how these features map onto specific affective interpretations remains a key question in music cognition. This study explored how listeners, unaware of contextual information, categorized 110 emotionally diverse excerpts—varying in key, tempo, note density, acoustic energy, and expressive gestures—from works by Bach, Beethoven, and Chopin. Twenty classically trained participants labeled each excerpt using six predefined emotional categories. Emotion judgments were analyzed within a supervised multi-class classification framework, allowing systematic quantification of recognition accuracy, misclassification patterns, and category reliability. Behavioral responses were consistently above chance, indicating shared decoding strategies. Quantitative analyses of live performance recordings revealed systematic links between expressive features and emotional tone: high-arousal emotions showed increased acoustic intensity, faster gestures, and dominant right-hand activity, while low-arousal states involved softer dynamics and more left-hand involvement. Major-key excerpts were commonly associated with positive emotions—“Peacefulness” with slow tempos and low intensity, “Joy” with fast, energetic playing. Minor-key excerpts were linked to negative/ambivalent emotions, aligning with prior research on the emotional complexity of minor modality. Within the minor mode, a gradient of arousal emerged, from “Melancholy” to “Power,” the latter marked by heightened motor activity and sonic force. Results support an embodied view of musical emotion, where expressive meaning emerges through dynamic motor-acoustic patterns that transcend stylistic and cultural boundaries.

1. Introduction

Music, a universal human experience, possesses a remarkable capacity to convey and evoke emotions across cultures and individual differences. This expressive power hinges on a rich interplay of auditory cues—such as timbre, mode, tempo, and dynamic contour—each of which contributes to listeners’ affective interpretation of musical passages. Increasingly, empirical research has begun to disentangle the neural, perceptual, and cultural mechanisms underlying this process, shedding light on how the brain decodes emotional content in music [1,2,3,4]. The objective of this study was to determine whether brief, context-free piano excerpts elicited consistent emotional categorizations across listeners, and to identify the structural and performance-level acoustic/motor features that best explain this convergence. In this study, we conceptually distinguish between emotional perception (listeners’ affective categorization), aesthetic judgment (evaluations of beauty or artistic value), and expressive properties of the musical stimulus; the present work focuses exclusively on the first, while drawing on the latter as structural predictors.

Recently Brattico et al. [5] explored the neural and musical correlates of perceived beauty during naturalistic music listening, employing behavioral ratings, fMRI, and expert analysis of Adios Nonino by Astor Piazzolla and The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky. Passages rated as beautiful elicited increased activity in the orbitofrontal cortex and reduced activation in auditory cortices, suggesting a top-down aesthetic evaluation mechanism. Notably, Piazzolla’s piece was generally more appreciated by musically untrained participants than Stravinsky’s. The “beautiful” fragments were more tonal, traditional, melodic, sad, calm, slow, and simple—characteristics associated with a melancholic, low-arousal emotional state reminiscent of “tenderness” and “serenity.” In contrast, excerpts labeled as “ugly” were more atonal, original, agitated, fast, rhythmically driven, and complex. Expert composers, however, attributed high aesthetic value to The Rite of Spring precisely because of these features, recognizing its sublimity, innovation, and artistic depth. If aesthetic appreciation is modulated by one’s experience and familiarity with a given style, this raises a crucial question: are there structural properties of music that can elicit emotional responses in a universal and unequivocal manner—responses that transcend cultural background [4,6,7].

A growing body of evidence supports the multifaceted nature of emotional communication in music. Armitage et al. [8] demonstrated that variations in timbre and mode significantly influenced the perceived emotional valence of melodies, with these effects moderated by the listener’s musical experience. In line with the cue redundancy theory, Kwoun [9] emphasized that cross-cultural emotion recognition in music relies on overlapping auditory cues, ensuring communicative robustness even across divergent cultural contexts. These findings reinforce the notion that music utilizes a multilayered communicative code—one resilient to cultural variability yet sensitive to individual experiential frameworks. Khalfa et al. [10] identified activation patterns in the anterior cingulate cortex and auditory cortices during the recognition of happy and sad musical excerpts, suggesting a distributed neural network dedicated to music-evoked emotions. Again, Proverbio and Piotti [11] reported that sad or negatively valenced melodic contours elicited greater activation in the right auditory regions of the superior temporal gyrus, whereas positively valenced (happy) melodic contours preferentially engaged the inferior frontal gyrus.

Beyond static acoustic features, dynamic elements such as expressive timing and bodily movement also shape affective experience. Irrgang and Egermann [12], using accelerometry, demonstrated that body motion can predict emotional judgments, highlighting the embodied nature of musical perception. The structural parallels between music and speech offer further insight into how emotional meaning is encoded. Poon and Schutz [13], analyzing 24-piece sets by Bach and Chopin, found that tempo and mode systematically influenced emotional perception: faster tempos and major modes were associated with high-arousal, positive emotions (e.g., happiness), while slower tempos and minor modes were linked to low-arousal or negative emotions (e.g., sadness). These patterns closely mirror the prosodic features of emotional speech, supporting the hypothesis that music and language share biologically grounded expressive strategies.

Early experimental work by Scherer and Oshinsky [14] synthesized eight-tone sequences manipulated along dimensions such as amplitude variation, pitch level and contour, tempo, and envelope. Listeners rated these on affective and dimensional scales (e.g., pleasantness-unpleasantness, activity-passivity, potency-weakness) and identified basic emotions such as happiness, sadness, anger, fear, boredom, surprise, and disgust. Tempo emerged as the most influential factor in predicting emotional ratings. Similarly, Juslin [15], focusing on performance features (tempo, sound level, spectrum, articulation, tone attack), found that emotional responses could be reliably predicted through linear combinations of acoustic features. A meta-analysis by Juslin and Laukka [3], further confirmed that basic emotions, such as happiness, sadness, anger, threat, and tenderness, can be decoded from music with above-chance accuracy by listeners regardless of cultural background. More recently, Nordströma and Laukka [16] demonstrated the rapidity of this process: emotional recognition accuracy was above chance for stimuli as short as ≤100 ms (for anger, happiness, neutral, sadness) and ≤250 ms for more complex emotions. The harmonic structure and timing of a musical fragment are thus promptly processed and interpreted by the brain’s auditory regions. Supporting this, Khalfa et al. [10] reported that fast-paced music tends to convey joyful sensations, whereas slow music is typically associated with sadness. Vieillard et al. [17] similarly found that happy excerpts (fast tempo, major mode) were perceived as arousing and pleasant; sad excerpts (slow tempo, minor mode) as low in arousal; threatening excerpts (minor mode, intermediate tempo) as arousing and unpleasant; and peaceful excerpts (slow tempo, major mode) as low in arousal but pleasant.

In order to further investigate the structural underpinnings of emotional responses to music, the present study examined how listeners categorized emotionally diverse musical excerpts based on their structural features, using a within-subjects design with piano works by Bach, Chopin, and Beethoven. Given the role of musical expertise in shaping perceptual and categorization strategies, the present study explicitly situates its findings within a listener population with formal musical training, without implying generalization to non-expert audiences. By linking affective judgments to musical properties such as key, tempo, and energy, this study aims to clarify how structural cues shape emotional perception in Western classical music. We hypothesized that minor versus major tonality would elicit greater sense of melancholy and sadness [17,18,19,20,21]; that faster tempos would enhance liveliness and joy in the major key, as opposed to relaxation and peace. Conversely, in the minor key, slower tempos were expected to be associated with sadness or depression [17,21], whereas a livelier tempo and higher arousal might convey a more active or constructive emotional tone. Finally, we predicted that the intensity of sound and energy of musical gesture, reflected in greater sonority, would be perceived, through a process of mimicry, as a sensation of power. Moreover, we hypothesized that greater musical complexity, operationalized as an increased number of notes played, would enhance the perception of unease or tension in the minor mode, and the sense of vitality in the major mode.

Across key studies on music and emotion, the nature of musical stimuli varies markedly in terms of origin, length, familiarity, and structural design. Some investigations, e.g., refs. [5,13] employed full-length or excerpted segments from canonical classical works (e.g., Stravinsky, Piazzolla, Bach, Chopin), preserving ecological validity and stylistic richness. Excerpts typically ranged from 8 bars to 60 s and were chosen based on their expressive characteristics or structural features. In contrast, other studies, e.g., refs. [14,15] utilized synthetic or manipulated stimuli designed to isolate specific acoustic dimensions (e.g., tempo, timbre, pitch contour). These were often brief (under 30 s) and purpose-built to ensure experimental control. Others, e.g., refs. [8,17] adopted emotionally categorized or cross-culturally validated excerpts—either composed ad hoc or drawn from lesser-known but affectively potent music. Meta-analytical findings [3,16] confirm that both naturalistic and minimal stimuli sometimes as short as 100 ms can effectively convey basic emotions. Overall, stimuli range from masterworks to synthetic sequences, selected or constructed to balance ecological realism with experimental precision. In the present study, we employed musical excerpts approximately 10–11 s in length, drawn from works of exceptionally high artistic value composed by seminal figures from distinct historical periods and stylistic traditions.

Specifically, we selected pieces by Johann Sebastian Bach (Baroque era, characterized by intricate counterpoint, harmonic clarity, and affective expressiveness), Ludwig van Beethoven (Classical to early Romantic transition, marked by formal innovation, dynamic contrast, and emotional depth), and Frédéric Chopin (Romantic period, known for lyrical phrasing, harmonic richness, and introspective expressivity). By using excerpts from such diverse yet universally acclaimed composers, our aim was to investigate whether specific structural properties of music—such as tonality, tempo, complexity and energy— might influence listeners’ emotional responses in a systematic manner, allowing us to test the extent to which such regularities emerge within a shared musical tradition [18]. Any claims regarding universality are therefore treated as hypotheses rather than conclusions. Categorical emotion labels are used here as an operational choice, without addressing the categorical–dimensional debate. Motor measures were treated as stimulus-level expressive cues perceptually accessible to listeners, rather than as performer-specific idiosyncrasies. Three limitations warrant consideration. First, restricting the sample to trained musicians was a deliberate choice to ensure sensitivity to parametric variations in tempo, modality, and energy; however, this choice also constrains generalization beyond expert listeners. Second, although familiarity with the repertoire was measured, it was not modeled analytically, as doing so would have shifted the focus away from structural musical parameters. Third, the single-performer design minimized expressive variability but necessarily conflated emotional expression with performer-specific motor and interpretive features, a point that future multi-performer studies should address.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Twenty healthy volunteers served as participants (8 M: mean age: 39.25, SD = 13.56; 12 F: mean age: 43.58, SD = 12.33; group: mean age: 41.85, SD = 12.47, range = 23–63). Recruitment of musicians was carried out by posting notices within academic circles of conservatories. Inclusion criteria were professional musicians with formal academic training (conservatory degree or equivalent), active engagement in musical practice, inclusion of both sexes, an age range between 20 and 65 years, and normal hearing and normal/corrected vision. Exclusion criteria comprised any history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, uncorrected sensory deficits, motor impairments affecting task performance, lack of formal musical education, or absence of current professional musical activity. All volunteers had received academic musical training: 17 were professional musicians, and three were non-professional musicians (see Table 1). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to inclusion in the study. A sensitivity power analysis for a repeated-measures ANOVA (within-subjects, 6 levels, α = 0.05, power = 0.80, n = 20) revealed that the design was sensitive to detect an effect size of f = 0.28 (partial η2 ≈ 0.075). This corresponds to a medium effect according to Cohen’s conventions. Written informed consent was obtained, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and institutional ethical guidelines and was approved by the Local University Ethics Committee (CRIP, protocol number RM-2023-605) on 1 October 2023.

Table 1.

Demographic information about the participants’ sample. Prof. Mus. = Professional Musicianship; Self-reported familiarity with the musical excerpts (rated on a 5-point Likert scale, where 1 = not at all familiar and 5 = extremely familiar) yielded a mean score of 3.45 (SD = 1.10), reflecting a moderate degree of prior acquaintance with the material. Familiarity ratings were collected for descriptive control purposes and were not included as analytical predictors, as the study focused on stimulus-driven effects rather than individual prior exposure.

2.2. Stimuli

The experimental stimuli comprised six piano works: J. S. Bach’s Die Kunst der Fuge (BWV 1080), specifically Contrapunctus I, VII, IX, and XI; Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 110, Adagio excerpt (bars 8–114); and Frédéric Chopin’s Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23, excerpt (bars 65–125). The scores used were: Bach’s The Art of Fugue, BWV 1080: Performance Score, edited and engraved by Dr. Dominic Florence, published by Contrapunctus Press in 2021; Chopin’s National Edition of the Works of Fryderyk Chopin, edited by Jan Ekier and Paweł Kamiński, published by PWM Edition; and Beethoven’s Beethovens Werke, Serie 16: Sonaten für das Pianoforte, Nr. 154 (pp. 113–128), Leipzig: Breitkopf und Härtel, originally published circa 1862. Hereafter, the works will be succinctly referred to as Bach Contrapunctus I, VII, IX, and XI, Chopin, and Beethoven.

All performances were delivered live by a 30-year-old right-handed professional concert pianist of international standing who began piano training at age four and graduated with honors from a globally recognized conservatory. He has garnered extensive international concert experience, appearing at prestigious venues and collaborating with renowned institutions worldwide, including, among others, New York’s Carnegie Hall, the Wiener Konzerthaus, London’s Wigmore Hall, the Nagoya Philharmonic Orchestra, Teatro alla Scala in Milan, and the Philharmonic Orchestra in Seoul. Therefore he was fully capable of executing the experimental repertoire with both technical mastery and expressive subtlety. The single-performer design was adopted to control interpretive variability and focus on stimulus-level structural properties. The performer had normal vision and hearing and reported no history of neurological or psychiatric disorders, including motor or cognitive impairments. The pianist performed in an anechoic chamber using a Yamaha P-225B digital piano set to the default grand piano sound. Performance audio was recorded in WAV format, with EEG and behavioral data collected simultaneously. The repertoire comprised six pieces, totaling approximately 27 min of performance. All works were performed from memory, informed by interpretative paradigms drawn from recent commercial recordings and the pianist’s touring repertoire, and were executed with stylistic coherence and interpretative naturalness following a brief phase of focused preparatory concentration.

2.3. Stimulus Structural Analysis and Selection

Audio processing was performed using Audacity version 3.7.0. This study used single-track mode for audio processing, and the time measurement accuracy reached milliseconds. The beat start time was determined by identifying the initial rise in the amplitude of the waveform corresponding to each beat observed in Audacity. When the left- and right-hand parts were inconsistent with the score in time, they were divided according to the main melody line. The recorded audio was divided into 110 musically meaningful fragments of about ten seconds (n = 110, M = 10.782, SD = 0.66) and randomly shuffled. At the same time, each music fragment was recorded with the start-end bars of the corresponding work, the elapsed time of the fragments, the number of bars, the number of notes for the left and right hands, the number of gestures, the number of gestures per measure, the number of gestures per second, and the mean intensity (see Supplementary file). Gestures were defined as each new key-press onset event within any passage. The number of notes for each hand was determined by counting the key-press onset events produced independently by the left and right hands. Notes sustained in legato passages, i.e., without new key presses, were excluded from all counts. The mean dBFS (decibels relative to full scale) values were computed using Audacity version 3.7.0. Specifically, the software’s Measure RMS function was employed to determine the average root-mean-square amplitude of each selected musical fragment. Two external pianists, both with extensive professional performance backgrounds and refined musical discernment, were engaged to conduct a preliminary classification (strictly based on structural parameters) and assist in the development of emotional labels. P1 was a 25-year-old female pianist with 20 years of formal piano training; P2, a 63-year-old male pianist and conservatory professor, had 54 years of formal instruction. The pianists were asked to classify each excerpt based on a range of musical attributes—such as tonality (major or minor), structural complexity, tempo, and dynamic contour—without access to any technical data or structural measurements, which were only introduced in subsequent phases of the analysis. Expert pianists jointly defined the emotion labels through consensus rather than independent rating. Six emotional categories were subsequently identified, grounded both in the structural characteristics of the excerpts and the emotional responses they evoked. They were: Peacefulness, Joy, Melancholy, Argumentative, Tension and Power (see Table 2), regardless of composer and style. Emotion labels were defined to ensure semantic clarity, while their assignment to musical excerpts was performed exclusively by participants. Given the specific nature of the piano excerpts under consideration, emotional classification was deemed unfeasible using either Russell’s [22] circumplex model of affect—which maps valence along the x-axis and arousal along the y-axis—or categorical annotation via the nine-factor Geneva Emotional Music Scale (GEMS-9; [23]). For ease of comparison with existing frameworks, our categories can still be related to established models such as GEMS [23] and the circumplex model [22] (i.e., Joy ≈ Joyful Activation/positive–high arousal; Peacefulness ≈ Peacefulness/positive–low arousal; Melancholy ≈ Sadness/negative–low arousal; Tension ≈ Tension/negative–high arousal; Power ≈ Power/high arousal), whereas Argumentative does not have a direct counterpart in these models, as it reflects a parametric–functional musical profile rather than a phenomenological emotion label.

Table 2.

Emotional categories used for classification of 110 musical excerpts, based on their key, tempo and acoustic energy. While the structural differences were objective, the emotional label reflected a psychological sensation (see also the rightmost row in the Supplementary file, reporting information about Feelings conveyed. The dash indicates a non-systematic association with the tagged variables.

While emotional categories such as Joy, Peacefulness, Tension, and Power have been recurrently employed in previous studies on music and affect (e.g., [17,24]), the evocative label Melancholy was introduced to capture those passages which, while imbued with a tone of reflective sadness, nonetheless exhibited an underlying structural coherence and expressive continuity—hallmarks of a refined aesthetic modality increasingly recognized in musicological discourse as Melancholy (e.g., [25,26]). On the other hand, the category Argumentative was employed to characterize selective minor-key passages which, despite their tonal tension, articulated a constructive impulse (argumentative, [27]) and a forward-oriented affective stance subtly suffused with hope. The emotional states of peace and joy were consistently associated with the major mode, while the perception of power and potency was primarily driven by acoustic energy. In contrast, the remaining three emotional states were reliably linked to the minor mode. The gradient from melancholy to tension and struggle was systematically modulated by the perceived level of acoustic and musical energy, while a similar energy-based modulation characterized the transition from peace to vitality within the major mode.

The attribution of emotional categories was carried out using a method grounded in phenomenological introspection, combining an objective assessment of key and tempo with a concurrent evaluation of perceived arousal or energy, conducted blind to the actual measured dBFS intensity values. Despite its noncanonical nature, the label “Argumentative” showed high consistency in listener judgments, supporting its perceptual clarity.

2.4. Experimental Procedure

All participants in the study were instructed to use headphones to listen to the audio stimuli. Following an introduction to the experimental protocol by the research staff, the participants listened to 110 randomly shuffled (bot for author and for order) music fragments, each approximately 10–11 s in duration. After each fragment, participants had 5 s to select one of the category labels (i.e., Peacefulness, Joy, Melancholy, Argumentative, Tension and Power) to match. The study took around 50 min to complete. After the experiment, participants were asked to rate their overall familiarity with the music fragments, according to the Likert scale from 1 to 5, where 1 = Not familiar at all and 5 = Very familiar. Instructions were: “Could you describe the kind of feeling or emotional state evoked by listening to these musical phrases (each approximately 10 s long)? How would you characterize your sensation based on the following six categories?” The list of labels remained constantly visible to participants throughout the selection process, and the categories were initially briefly defined as reported below (Table 3). Emotion categories were intentionally defined at a descriptive level, allowing listeners to use semantically rich labels that may not map one-to-one onto canonical emotion taxonomies, but capture perceived expressive qualities of the stimuli.

Table 3.

Conceptual definitions presented to participants to clarify the intended meaning of the emotional labels. Emotion labels were intentionally minimally specified to allow individual interpretative variability in perceptual judgments.

Participants were not provided with any information regarding the structural properties of the pieces, their tonalities, or the identities of the composers or works included in the experiment. The musical excerpts were presented in random sequences, and participants were given no interpretative framework other than a brief, two- to three-word definition for each of the six emotional categories. The entire set of 110 piano excerpts was categorized by percentage of participant-selected emotion tags and combined with the emotion classification results of two external pianists, ranked from highest to lowest frequency of label assignment. Emotional valence was assessed solely through explicit verbal labeling by listeners; no facial, gestural, or neurophysiological data were collected from participants, while quantitative analyses were restricted to computationally extracted features of the musician’s gestures. Stimuli were validated based on perceptual discriminability and structural differentiation, following standard procedures in perceptual research. Emotion categories were used as operational, structure-based classes rather than theory-defined emotional ground truth.

2.5. Confusion Matrix

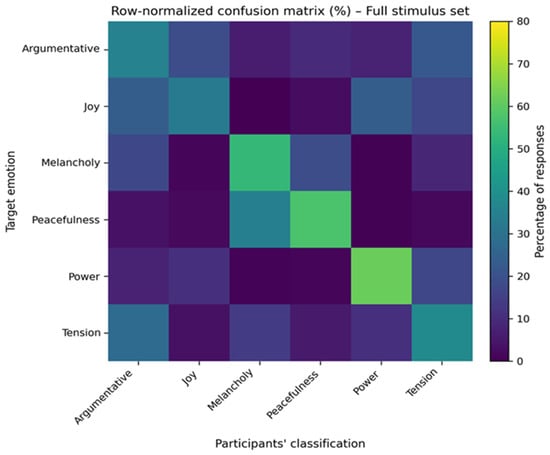

Participants’ emotion judgments were analyzed within a supervised multi-class classification framework, allowing systematic quantification of agreement and misclassification patterns relative to predefined target categories. Category-level classification metrics applied to judges’ evaluations on all fragments revealed systematic differences in performance across emotion labels (Figure 1). Power and Melancholy showed the highest F1-scores (0.59 and 0.58, respectively), indicating both high precision and recall. Peacefulness exhibited moderate performance (F1 = 0.49), with frequent confusions with Melancholy. High-arousal categories showed lower and more variable performance. Tension (F1 = 0.45) and Argumentative (F1 = 0.39) were frequently confused with one another, while Joy showed the lowest overall performance (F1 = 0.31), reflecting diffuse use of this label across multiple energetic emotional states.

Figure 1.

Row-normalized confusion matrix of emotion classification relative to the initial set of 110 musical phrases. Rows represent target emotion categories, and columns represent participants’ classifications. Cell color indicates the percentage of responses assigned to each category within each target emotion (rows sum to 100%). The heatmap highlights systematic misclassification patterns, with strong within-category agreement for Melancholy, Peacefulness, and Power, and substantial overlap among high-arousal categories such as Tension and Argumentative.

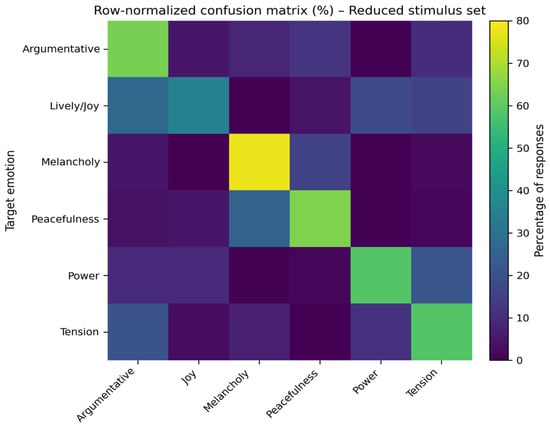

To improve classification reliability, stimuli with low recognizability were excluded, resulting in a reduced set of 56 musical fragments (10 per emotion category, except Peacefulness, n = 6). After exclusion of poorly recognizable stimuli, emotion classification performance improved consistently across all categories. The reduced stimulus set comprised 56 musical excerpts (10 per emotion category, except Peacefulness, n = 6) and yielded clearer and more stable classification patterns. Given the use of authentic musical repertoire, stimuli were selected based on intrinsic expressive clarity rather than forced category balance. These excerpts thus represented the most prototypical exemplars for each emotional condition and underwent statistical processing for understanding the relationship between musical structure and perceived emotional tone. The discarded fragments showed anyhow an above-chance accuracy rate of 47% (chance threshold being 16.67%). The row-normalized confusion matrix revealed a marked strengthening of within-category agreement relative to the full stimulus set (see Figure 2). Melancholy showed the highest classification stability, with a recall of 0.78 and an F1-score of 0.71, indicating that this emotional category was both reliably recognized and selectively used by participants (see Table 4).

Figure 2.

Row-normalized confusion matrix for the reduced stimulus set (56 musical fragments). Rows represent target emotion categories and columns represent participants’ classifications. Cell color indicates the percentage of responses assigned to each category within each target emotion. After exclusion of poorly recognized stimuli, classification accuracy increased across all emotion categories, with particularly strong within-category agreement for Melancholy, Peacefulness, and Power. High-arousal categories continued to show partial overlap, indicating graded rather than categorical emotion representations.

Table 4.

Category-level classification performance for the reduced stimulus set (56 musical excerpts). Precision, recall, and F1-scores are reported for each emotion category, computed from the global confusion matrix after exclusion of poorly recognizable stimuli. The reduced stimulus set shows increased classification performance across all categories, with particularly high F1-scores for Melancholy narration, Peacefulness, and Power, indicating enhanced within-category agreement following stimulus selection.

Peacefulness also exhibited high performance (F1 = 0.66), despite the relatively smaller number of stimuli, suggesting robust perceptual coherence for low-arousal affective states. Among high-arousal categories, Power achieved a comparatively high F1-score (0.64), reflecting improved precision following stimulus selection. Argumentative and Tension showed intermediate performance (F1 = 0.58 for both), with persistent but reduced mutual confusability. Joy remained the least stable category (F1 = 0.41), although its performance improved substantially compared to the full stimulus set. Lower classification accuracy for Joy likely reflects its greater expressive variability rather than reduced perceptual consistency, with performance remaining well above chance. Overall, the reduced stimulus set demonstrated increased classification accuracy and reduced ambiguity, particularly for low-arousal emotional categories. Residual misclassifications were primarily confined to conceptually related high-arousal emotions, supporting the interpretation that musical emotion perception is organized along graded affective dimensions rather than strictly discrete categories. Despite shared high-arousal features, tonal modality enabled listeners to differentiate qualitatively distinct emotional categories

2.6. Statistical Analyses

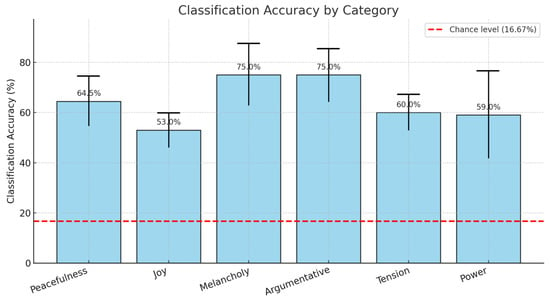

As for hit percentages, to determine whether each emotional category was classified significantly above chance level (16.67%), we conducted a series of one-sample t-tests. For each category, mean classification accuracy and standard deviation were used to assess group-level performance (n = 20 per category). The results indicated that all emotional categories were recognized significantly above chance (see Figure 3):

Figure 3.

Classification accuracy by emotional category (hits). Mean classification accuracy (%) is displayed for each emotional category, with error bars indicating standard error of the mean (SEM). The red dashed line represents the theoretical chance level (16.67%), corresponding to random classification across six categories. Notably, all categories were classified significantly above chance, with the highest accuracy observed for Argumentative (75.0%) and Melancholy (75%) the lowest for Joy (53.0%). Please note that category-wise accuracy reflects recall (correct identification of the target emotion), whereas F1-scores additionally account for false-positive responses and therefore provide a more conservative measure of categorical reliability.

- Peacefulness: M = 64.5%, SD = 9.86, t (19) = 19.86, p < 0.001

- Joy: M = 53.0%, SD = 6.92, t (19) = 22.63, p < 0.001

- Melancholy: M = 75.0%, SD = 12.24, t (19) = 16.05, p < 0.001

- Argumentative: M = 75.0%, SD = 10.74, t (19) = 20.11, p < 0.001

- Tension: M = 60.0%, SD = 7.09, t (19) = 31.27, p < 0.001

- Power: M = 59.0%, SD = 17.33, t (19) ≈ 11.50, p < 0.001

All p-values remained significant after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. These findings confirm that each emotional category was reliably classified well above chance, supporting the robustness of the classification model across diverse affective domains.

The structural parameters —such as the number of notes played by the left and right hands, intensity, and number of musical gestures—were analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVAs. The between-subject factor was either the emotional category or the composer, while the structural properties served as dependent variables. Given the within-subject design and the robustness of the ANOVA framework, no outlier testing or data exclusion procedures were applied, and all data points were retained. Effect sizes were estimated using partial eta squared (η2p), which reflects the proportion of variance accounted for by a given factor, partialling out other sources of variance. This measure was chosen as it is widely used and facilitates comparison with similar studies in the literature. The Greenhouse–Geisser ε correction was applied to account for possible non-sphericity of the data.

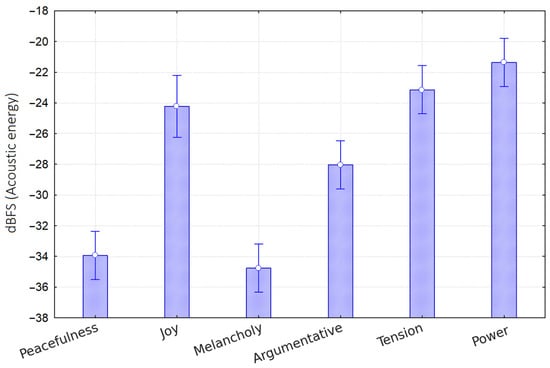

3. Results

The ANOVA conducted on the dBFS intensity values of the musical excerpts revealed a significant effect of the factor Emotional Category [F (5,50) = 51.6, p < 0.0001, ε = 1, η2p = 0.838] (Figure 4). Post hoc tests indicated significantly lower sound intensity for the emotions of Peace and Melancholy (p < 0.0001), intermediate levels for the Argumentative category, and similarly high levels of acoustic energy for the emotional categories of Joy (p < 0.02), Tension and Power (p < 0.0001).

Figure 4.

Mean acoustic energy (dBFS) across musical excerpts categorized by perceived emotional tone. Emotional categories were assigned based on listeners’ ratings. Bars show average root mean square (RMS) energy for each category, with error bars indicating ± 1 standard error of the mean (SEM). Perceived high-arousal tones such as Power and Tension, but also Joy were associated with significantly higher acoustic energy, whereas low-arousal tones like Peacefulness and Melancholy exhibited lower energy levels. Energy depended both on the intrinsic properties of the musical material and the expressive interpretation provided by the pianist.

The ANOVA conducted on the number of played notes (per fragment) revealed a significant interactive effect of Hand x Composer [F (2,53) = 3.74, p < 0.03, η2p = 0.12]. Post hoc analyses indicated that both Chopin and especially Bach excerpts (p < 0.01) exhibited a significantly higher proportion of right-hand keystrokes compared to left-hand ones. Bach fragments showed the highest overall note density (i.e., total number of played notes per fragment), followed by Chopin. Conversely, Beethoven excerpts were characterized by the highest number of left-hand notes and the lowest number of right-hand notes (p < 0.001), suggesting a left-hand dominant motor profile. Despite the substantial structural and stylistic differences among the three composers, fragments with similar acoustic and structural properties were associated with comparable emotional perceptions across pieces. This suggests that expressive features contributing to emotional tone can transcend compositional style.

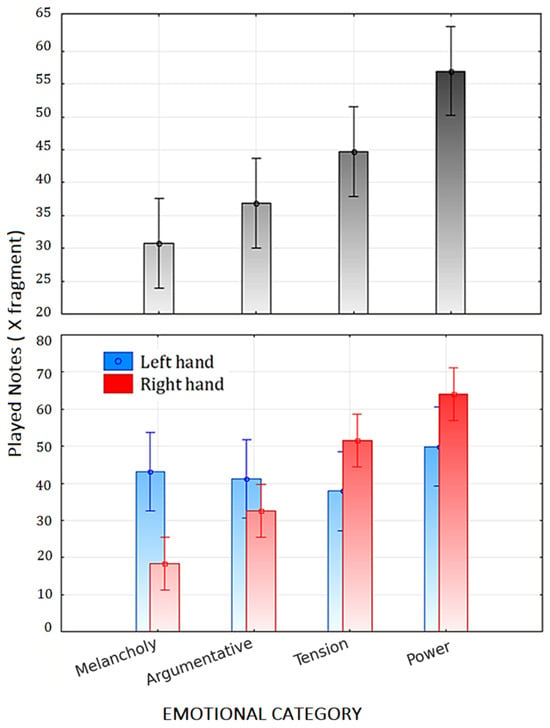

An additional ANOVA was conducted on the number of notes played in minor key phrases, using as a factor the emotional category identified by participants (Melancholy, Argumentative, Tension, and Power). The analysis (Figure 5) revealed a significant main effect of emotional category [F (3,36) = 11.37, p < 0.00002, η2p = 0.49] and of its interaction with Hand [F (3,36) = 10.37, p < 0.00005, η2p = 0.46]. Post hoc comparisons revealed comparable levels of structural complexity (as indexed by the number of notes played) between the melancholic and argumentative fragments, albeit with a trend toward increased complexity in the latter. A marked rise in complexity was observed in fragments conveying tension or struggle (p < 0.005), and an even more pronounced increase was noted in those associated with the expression of power (p < 0.001). Notably, the interaction between factors indicated that this effect was specific to the right-hand piano part, with no significant differences emerging in the left-hand part as a function of emotional category. Interestingly, the left hand (reflecting right-hemispheric engagement) was significantly more involved in executing notation associated with low-arousal affective states—such as Melancholy (p < 0.0001)—whereas the right hand exhibited greater involvement in performing notation linked to high-arousal states, such as Power (p < 0.02), as evidenced by post hoc analyses.

Figure 5.

Distribution of played notes across affective musical fragments and manual lateralization. (Top): Average number of notes played per fragment across four expressive categories (Melancholy, Argumentative, Tension, and Power). A progressive increase in note density is observed with increasing emotional intensity. (Bottom): Manual lateralization of note execution, showing a greater involvement of the left hand (blue) in fragments conveying low-arousal states (e.g., Melancholy), and of the right hand (red) in high-arousal states (e.g., Power). Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM). Post hoc comparisons revealed significant differences in hand usage across affective conditions (p < 0.0001 for Melancholy; p < 0.02 for Power).

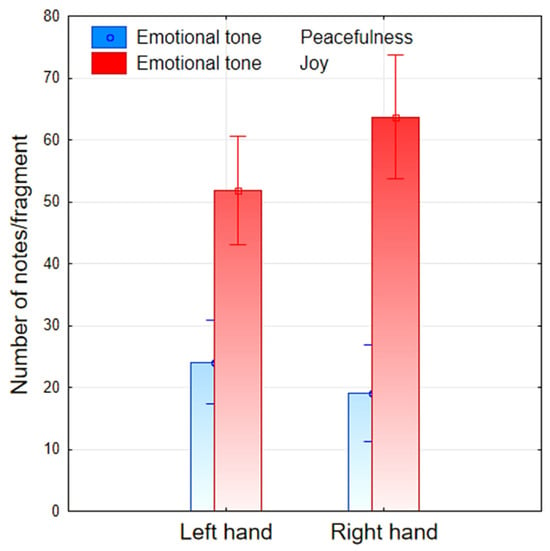

A further ANOVA was conducted on the number of notes played in major key phrases, using as a factor the emotional category identified by participants (Peacefulness and Joy). The analysis (Figure 6) revealed a significant main effect of Emotional category [F (1,14) = 52, p < 0.00001, η2p= 0.79]. The number of notes associated with the Joyful emotional state (M = 57.75, SD = 3.96) was markedly higher than that employed to convey a sense of Peacefulness (M = 21.6, SD = 3.01), highlighting a substantial increase in musical density corresponding to heightened emotional arousal, regardless of composer. The further interaction of Emotional category x Hand [F (3,36) = 10.37, p < 0.00005, η2p = 0.50], and relative post hoc comparisons, revealed no significant hand asymmetry in the execution of musical fragments conveying Peacefulness, whereas a pronounced right-hand dominance emerged for high-arousal emotional states such as Joy—a pattern reminiscent of that observed in the performance of passages in the minor key.

Figure 6.

Manual distribution of note execution as a function of emotional tone. Bar plot illustrating the number of notes per fragment performed by the left and right hands for two contrasting emotional states: Peacefulness (low-arousal) and Joy (high-arousal). While no significant lateral asymmetry was observed for Peacefulness, Joy elicited a markedly greater involvement of the right hand, suggesting a motoric correlate of emotional arousal. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM).

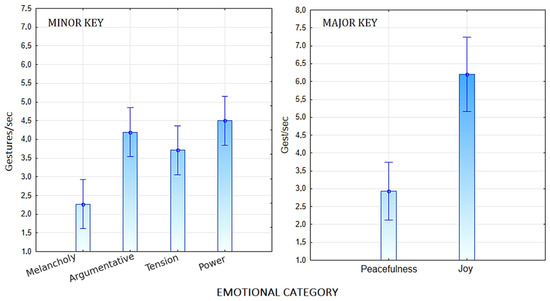

A further ANOVA was conducted on the number of gestures/sec, reflecting both executive complexity, and motoric energy, for fragments in minor and major modes, respectively. The first ANOVA showed the significance of Emotional category [F (3,36) = 9.44, p < 0.00001, η2p = 0.44]. Post hoc comparisons indicated a markedly lower execution speed (gestures per second) in fragments perceived as expressing Melancholy, compared to other types of emotional states conveyed in the minor key (see Figure 7). The second ANOVA also revealed a significant main effect of Emotional Category [F (1,14) = 28.24, p < 0.0001, η2p = 0.67], with a markedly higher execution speed observed for fragments conveying Joy compared to those expressing Peacefulness.

Figure 7.

Average gesture frequency (gestures/sec) associated with distinct expressive categories under two musical modes: minor key (left) and major key (right). Blue bars indicate mean values; vertical lines represent standard error. In the minor mode, Argumentative, Tension, and Power conditions elicited significantly higher gesture rates compared to Melancholy. In the major mode, Joy was associated with markedly more gestural activity than Peacefulness. These results suggest a systematic relationship between the emotional–prosodic qualities of music and the intensity of bodily expressivity and motor activity of the pianist.

4. Discussion

The present findings offer compelling evidence for a tight coupling between perceived emotional tone in music and its underlying acoustic and motoric features, as revealed by performance-level analyses. Specifically, variations in key, acoustic energy, tempo, note density, and manual lateralization systematically aligned with the emotional categories assigned by listeners, suggesting a shared encoding of affective intent across expressive and structural dimensions [3,10,15,17]. Higher emotional arousal—indexed by categories such as Power, Tension, and Joy—was consistently associated with increased sound intensity (dBFS) and note density, particularly within the right-hand register. This pattern is consistent with prior evidence linking high-arousal states to elevated motor output and increased activation of left-hemispheric motor networks, commonly associated with right-hand dominance in pianistic execution. Conversely, low-arousal emotional tones (e.g., Peacefulness, Melancholy) were marked by reduced acoustic intensity, lower motoric complexity, and enhanced involvement of the left hand, pointing to a possible right-hemispheric specialization for the expressive rendering of subdued or introspective affective states [28,29,30], consistent with a functional right-hemispheric involvement inferred from hand-specific motor patterns, without implying direct neural evidence.

Interestingly, despite the stylistic and structural differences among the selected composers (Bach, Chopin, Beethoven, see Figure 8), similar emotional categories elicited comparable acoustic and motor profiles, suggesting that expressive features shaping emotional perception may transcend compositional idiom.

Figure 8.

Representative excerpts highlighting the extreme stylistic differences in considered piano works by Bach, Chopin, and Beethoven. The musical passages correspond to J. S. Bach’s The Art of Fugue (BWV 1080), specifically Contrapunctus XI, mm. 153–156 (top); Frédéric Chopin’s Ballade No. 1 in G minor, Op. 23, mm. 94–96 (middle); and Ludwig van Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in A♭ major, Op. 110, mm. 10–11 (bottom). Each excerpt exemplifies the composer’s distinct approach to thematic development and texture—from Bach’s intricate fugal counterpoint, to Chopin’s dramatic lyricism and pianistic idiom, and Beethoven’s late-period synthesis of structural clarity and expressive depth.

The observed right-hand lateralization for high-arousal states, alongside the increased execution speed in both major and minor key passages, further underscores a motor-expressive coupling underlying musical performance, without implying neural mechanisms. These effects may reflect the embodied nature of emotion processing, wherein affective meaning is not only perceived but also enacted through differential motor planning and execution [31]. Finally, the interaction between musical mode (major vs. minor) and emotional content highlights the importance of context-dependent mappings between harmonic structure and affective interpretation [10,17]. While fragments in major mode conveyed arousal-related differences (e.g., Joy vs. Peacefulness), similar gradations were also evident in minor-mode passages (Melancholy to Power), emphasizing that musical affect arises from a dynamic interplay between structural, expressive, and sensorimotor dimensions [13]. Several studies have explored the perceptual and physiological underpinnings of how slow, minor-mode music is commonly perceived as sad. For instance, Huron [32,33] has compellingly argued that this association is rooted in embodied cues that mirror the expressive behaviors of individuals experiencing low affective states, such as depression. In such conditions, diminished dopaminergic activity can lead to reduced muscle tone, including in the laryngeal and articulatory systems, resulting in vocal expressions that are weak, breathy, and characterized by lower fundamental frequencies. Moreover, the overall motor behavior of individuals with depressed mood tends to be marked by hypokinesia—slow, sparse, and lethargic movements. These observable markers, when encoded in the auditory qualities of music—namely, slow tempi, subdued dynamics, and a narrow pitch range—are interpreted as communicative signals of sadness. Huron posits that listeners, whether consciously or not, draw on these embodied correlations to infer emotional content, thus explaining the widespread tendency to perceive such musical features as expressive of sorrow. Indeed, in the minor scale, the lowering of the third, sixth, and seventh degrees by a semitone may play a crucial role in its distinctive emotional tone. In a mirror-like fashion, sad utterances similarly exhibit lower pitch, minimal pitch variation, reduced intensity, and slower tempo—all cues associated with sadness in speech. These features parallel the characteristics of sad music, such as dark timbres and repetitive, minimally articulated phrases, which resemble a mimed lamentation [18].

Acoustic spectrum analyses of speech and vocalizations have further demonstrated that expressions of sadness and anger tend to use frequency intervals typical of minor tonality, whereas joy is often expressed through major tonality. Consequently, the brain processes music as if it were a form of voice, intuitively grasping its emotional meaning through innate mechanisms. In a series of three studies, we investigated the existence of a unified neural mechanism for decoding auditory emotional cues by transforming speech prosody and vocalizations into instrumental music and comparing event-related potentials (ERPs) elicited by speech, music, and voices [34,35,36] examined the neural encoding of emotional vocalizations and their musical counterparts—violin music digitally transformed from the same vocalizations. Positive and negative stimuli elicited enhanced late positive potentials (LP) and amplified N400 components, respectively. Source reconstruction revealed that negative stimuli consistently activated the right middle temporal gyrus, whereas positive stimuli engaged the inferior frontal cortex, irrespective of stimulus modality (voice or music). Acoustic analysis further demonstrated that emotionally negative stimuli tended to align with a minor key, while positive stimuli were associated with a major key, offering valuable insights into the brain’s ability to interpret music through an emotional lens.

The current study provides robust evidence that emotional perception in music is tightly coupled with measurable acoustic and motoric parameters during performance, aligning with and expanding upon previous findings in affective neuroscience and music cognition [37,38]. By systematically manipulating and analyzing expressive musical fragments across different emotional categories and composers, our data demonstrate that emotional tone is not merely a subjective interpretation, but reflects quantifiable expressive features, including acoustic energy (dBFS), note density, gesture speed, and lateralized motor output.

A central contribution of this work lies in showing that arousal-based emotional states, such as Power, Tension, and Joy, are consistently associated with higher sound intensity, increased note density, and faster execution speed. These findings converge with neurophysiological evidence indicating that high-arousal emotions engage sensorimotor and premotor networks more intensely, particularly in the left hemisphere, which is associated with right-hand dominance in pianistic execution [39,40]. In contrast, low-arousal emotions such as Peacefulness and Melancholy were marked by reduced acoustic and motoric complexity and a significant shift toward left-hand execution, potentially reflecting a right-hemispheric specialization for the processing of introspective, low-arousal affective states [28,41]. This manual dissociation supports previous work suggesting that emotion-related lateralization in music can be behaviorally observed through expressive performance features [31].

One of the most compelling aspects of this study might be its innovative approach to emotional categorization, especially regarding the inclusion of musically nuanced affective states such as Argumentative or Melancholy. Unlike traditional basic emotion frameworks (e.g., anger, fear, disgust; [42]), which may poorly capture the affective subtleties of instrumental music, particularly in the context of composers like Bach, this study introduces a functionally expressive lexicon more aligned with music’s semantic and rhetorical dimensions [43,44]. Strikingly, listener ratings revealed that such abstract, non-basic emotional categories were readily understood and reliably attributed, indicating a shared cognitive-affective schema that listeners apply when decoding musical intention, even in the absence of linguistic content. This finding is particularly noteworthy in light of work on music as a communicative system, which posits that music may express intentions, tensions, and resolution strategies through time-structured gestures, mirroring the dynamics of narrative or argumentation [32,38,45]. The reliable identification of categories such as Argumentative suggests that listeners can decode goal-oriented emotional trajectories in music, especially in styles such as Baroque counterpoint, which lend themselves to dialogic or rhetorical interpretations. The present study does not aim to introduce a novel emotion taxonomy, but to demonstrate that musically grounded, non-basic affective categories can be reliably perceived and systematically related to acoustic and motoric features of performance. Moreover, despite marked structural and stylistic differences among composers (e.g., the contrapuntal density of Bach, the lyrical asymmetry of Chopin, and Beethoven’s rhythmic-motoric force), the results show that musical fragments associated with similar emotional states were expressed and perceived similarly across composers. This points to shared expressive mechanisms that may operate independently of stylistic convention—possibly mediated by common neural processes for affective interpretation and sensorimotor simulation [46,47]. Taken together, these findings underscore the embodied nature of musical emotion, where expressive intentions are mapped onto specific acoustic-motor configurations, and perceived affect arises from the listener’s internal simulation of these motoric gestures [12,48,49,50]. The observed hand-specific lateralization—right hand for high-arousal, left hand for low-arousal—adds further weight to the notion that emotions in music are enacted through distinct motor profiles, potentially reflecting the affective-motor coupling proposed in embodied cognition theories. In the present framework, performer agency is not treated as separable from listener perception, but as a mediating link through which compositional structure is translated into embodied gestures that listeners implicitly simulate during emotional decoding.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study advances the neuroscience of music emotion by offering a richer and more ecologically valid taxonomy of affective states, grounded in the expressive realities of piano performance. By going beyond conventional emotion labels and embracing musically meaningful categories, we demonstrate that music can convey a spectrum of psychological states with high specificity and intersubjective recognizability—affirming its role not just as an emotional stimulus, but as a language of embodied meaning. Throughout the study, emotional categories are treated as task-dependent perceptual constructs elicited by the listening context, rather than as stable or trait-like psychological entities. In sum, the present results provide novel empirical support for the neurocognitive embodiment of musical emotion [49], revealing how performers implicitly adapt acoustic and motoric strategies in accordance with perceived emotional tone—thereby aligning expressive nuance with the neural architecture of affective and motor control. Confusion matrix analyses further indicate that observers reliably discriminate fine-grained emotional nuances on the basis of acoustic and structural features such as tempo, tonal complexity, dynamic intensity, and motor expressivity, supporting the view that emotional meaning in music emerges from systematic mappings between sound, action, and affect. Our results may contribute to the rational selection of musical stimuli for therapeutic contexts by informing hypotheses about emotion–music associations; however, any application to clinical populations (e.g., depression, PTSD, or autism spectrum disorders) would require targeted clinical validation beyond the scope of the present study.

6. Study Limitations

While the present study offers compelling evidence for the structural and motoric underpinnings of perceived musical emotion, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the exclusive use of Western classical piano repertoire—albeit stylistically diverse—limits the generalizability of the findings to other musical traditions or genres, such as non-Western, vocal, or electronically produced music. Second, all excerpts were performed by a single expert pianist, which, while ensuring interpretive consistency, may constrain the variability of expressive nuances and introduce performer-specific biases in dynamics and gesture. Third, although the sample comprised highly trained musicians, their shared background may have led to convergent interpretative strategies, potentially inflating classification accuracy; future research should examine the same stimuli in musically untrained or cross-cultural populations. Additionally, the emotional categories employed, while musically nuanced, were predefined and may not fully capture the richness or ambiguity of listeners’ affective experiences. Stimuli were randomized across composers and emotional categories; potential fatigue effects would therefore be nonspecific. Although the present interpretations are informed by affective neuroscience frameworks, the study relies exclusively on behavioral and acoustic data; therefore, alternative explanations based on salient perceptual cues (e.g., tempo or density), rather than embodied motor simulation, cannot be excluded and should be addressed in future neurophysiological investigations. Addressing these limitations will be crucial for refining models of embodied musical cognition and for expanding the universality claims regarding emotional decoding in music.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16031371/s1, Table S1: Structural, performative, and affective features of selected musical excerpts.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.M.P.; methodology, A.M.P., C.Q. and M.M.; formal analysis, C.Q. and M.M.; investigation, A.M.P., C.Q. and M.M.; resources, A.M.P.; data curation, C.Q. and M.M.; writing—original and final draft preparation, A.M.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the ATE—Fondo di Ateneo 2025 (Grant No. 2025-ATE-0077; project code 66232).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Local University Ethics Committee (CRIP, protocol number RM-2023-605) on 1 October 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data supporting the findings of this study are included within the article. Additional information or data sharing are available from the author upon reasonable request, particularly to support scientific collaboration.

Acknowledgments

We are deeply grateful to all those who made this unprecedented live recording possible, and especially to the anonymous pianist, whose generous participation and exceptional musical expertise were essential to the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations were used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| dBFS | Decibels relative to full scale |

| F1 | Fidelity score |

| FMRI | Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging |

| LP | Late Positivity |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

References

- Fuentes-Sánchez, N.; Espino-Payá, A.; Prantner, S.; Sabatinelli, D.; Pastor, M.C.; Junghöfer, M. On joy and sorrow: Neuroimaging meta-analyses of music-induced emotion. Imaging Neurosci. 2025, 3, imag_a_00425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S. A coordinate-based meta-analysis of music-evoked emotions. Neuroimage 2020, 223, 117350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslin, P.N.; Laukka, P. Communication of emotions in vocal expression and music performance: Different channels, same code? Psychol. Bull. 2003, 129, 770–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslin, P.N.; Sloboda, J.A. Music and emotion. In The Psychology of Music, 3rd ed.; Deutsch, D., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2011; Volume 3, pp. 583–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattico, E.; Brusa, A.; Dietz, M.; Jacobsen, T.; Fernandes, H.M.; Gaggero, G.; Toiviainen, P.; Vuust, P.; Proverbio, A.M. Beauty and the brain—Investigating the neural and musical attributes of beauty during naturalistic music listening. Neuroscience 2025, 567, 308–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Mehr, S.A. Universality, domain-specificity, and development of psychological responses to music. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 2023, 2, 333–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sievers, B.; Polansky, L.; Casey, M.; Wheatley, T. Music and movement share a dynamic structure that supports universal expressions of emotion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 70–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Armitage, J.; Eerola, T.; Halpern, A.R. Play it again, but more sadly: Influence of timbre, mode, and musical experience in melody processing. Mem. Cogn. 2024, 53, 869–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwoun, S.J. An examination of cue redundancy theory in cross-cultural decoding of emotions in music. J. Music Ther. 2009, 46, 217–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khalfa, S.; Schön, D.; Anton, J.-L.; Liégeois-Chauvel, C. Brain regions involved in the recognition of happiness and sadness in music. Neuroreport 2005, 16, 1981–1984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, A.M.; Piotti, E. Common neural bases for processing speech prosody and music: An integrated model. Psychol. Music 2022, 50, 1408–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Irrgang, M.; Egermann, H. From motion to emotion: Accelerometer data predict subjective experience of music. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0154360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poon, M.; Schutz, M. Cueing musical emotions: An empirical analysis of 24-piece sets by Bach and Chopin documents parallels with emotional speech. Front. Psychol. 2015, 6, 1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scherer, K.R.; Oshinsky, J.S. Cue utilisation in emotion attribution from auditory stimuli. Motiv. Emot. 1977, 1, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juslin, P.N. Perceived emotional expression in synthesized performances of a short melody: Capturing the listener’s judgment policy. Musicæ Sci. 1997, 1, 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordström, H.; Laukka, P. The time course of emotion recognition in speech and music. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2019, 145, 3058–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieillard, S.; Peretz, I.; Gosselin, N.; Khalfa, S.; Gagnon, L.; Bouchard, B. Happy, sad, scary and peaceful musical excerpts for research on emotions. Cogn. Emot. 2008, 22, 720–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, A.M. A unified mechanism for interpreting the emotional content of voice, speech and music: Comment on “The major-minor mode dichotomy in music perception”. Phys. Life Rev. 2025, 52, 107–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraturo, G.; Pando-Naude, V.; Costa, M.; Vuust, P.; Bonetti, L.; Brattico, E. The major-minor mode dichotomy in music perception. Phys. Life Rev. 2025, 52, 80–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpern, A.R.; Martin, J.S.; Reed, T.D. An ERP study of major–minor classification in melodies. Music Percept. 2008, 25, 181–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huron, D. Distinguishing nature and nurture in understanding the sadness of the minor mode. Phys. Life Rev. 2025, 53, 144–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. A circumplex model of affect. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 39, 1161–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobsen, P.-O.; Strauß, H.; Vigl, J.; Zangerle, E.; Zentner, M. Assessing aesthetic music-evoked emotions in a minute or less: A comparison of the GEMS 45 and the GEMS 9. Musicæ Sci. 2024, 29, 184–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuilleumier, P.; Trost, W. Music and emotions: From enchantment to entrainment. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015, 1337, 212–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Hernando, A. Constellations, Loss and Phantasy: A Study of the Melancholic Self and Its Discourse in Hamlet, Ulysses and The Sound and The Fury. Master’s Thesis, Complutense University of Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Toth, R.; Dienlin, T. Bittersweet symphony: Nostalgia and melancholia in music reception. Music Sci. 2023, 6, 20592043231155640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varwig, B. One more time: J.S. Bach and seventeenth-century traditions of rhetoric. Eighteenth-Century Music 2008, 5, 179–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R.J.; Irwin, W. The functional neuroanatomy of emotion and affective style. Trends Cogn. Sci. 1999, 3, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gainotti, G. Emotions and the right hemisphere: Can new data clarify old models? Neuroscientist 2019, 25, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, D. Depression and the hyperactive right hemisphere. Neurosci. Res. 2010, 68, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altenmüller, E.; Schürmann, K.; Lim, V.K.; Parlitz, D. Hits to the left, flops to the right: Different emotions during listening to music are reflected in cortical lateralisation patterns. Neuropsychologia 2002, 40, 2242–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huron, D. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Huron, D. Why is sad music pleasurable? A possible role for prolactin. Musicæ Sci. 2011, 15, 146–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, A.M.; De Benedetto, F.; Guazzone, M. Shared neural mechanisms for processing emotions in music and vocalizations. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2020, 51, 1980–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proverbio, A.M.; Santoni, S.; Adorni, R. ERP markers of valence coding in emotional speech processing. iScience 2020, 23, 100933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proverbio, A.M. Cognitive Neuroscience of Music (Neuroscienze Cognitive Della Musica); Zanichelli: Bologna, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Juslin, P.N.; Västfjäll, D. Emotional responses to music: The need to consider underlying mechanisms. Behav. Brain Sci. 2008, 31, 559–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koelsch, S. Brain correlates of music-evoked emotions. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014, 15, 170–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumgartner, T.; Lutz, K.; Schmidt, C.F.; Jäncke, L. The emotional power of music: How music enhances the feeling of affective pictures. Brain Res. 2006, 1075, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trost, W.; Ethofer, T.; Zentner, M.; Vuilleumier, P. Mapping aesthetic musical emotions in the brain. Cereb. Cortex 2012, 22, 2769–2783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, L.A.; Trainor, L.J. Frontal brain electrical activity (EEG) distinguishes valence and intensity of musical emotions. Cogn. Emot. 2001, 15, 487–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. An argument for basic emotions. Cogn. Emot. 1992, 6, 169–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brattico, E.; Alluri, V.; Bogert, B.; Jacobsen, T.; Vartiainen, N.; Nieminen, S.; Tervaniemi, M. A functional MRI study of happy and sad emotions in music with and without lyrics. Front. Psychol. 2011, 2, 308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, A.D. Music, Language, and the Brain; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Limb, C.J. Structural and functional neural correlates of music perception. Anat. Rec. A 2006, 288, 435–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zatorre, R.J.; Chen, J.L.; Penhune, V.B. When the brain plays music: Auditory–motor interactions in music perception and production. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Molnar-Szakacs, I.; Overy, K. Music and mirror neurons: From motion to “e”motion. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 2006, 1, 235–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leman, M. Embodied Music Cognition and Mediation Technology; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Freedberg, D.; Gallese, V. Motion, emotion and empathy in aesthetic experience. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 197–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallese, V.; Freedberg, D. Mirror and canonical neurons are crucial elements in aesthetic response. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007, 11, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.