Abstract

Electro slag remelting steel is a technology of tertiary metallurgy that can be used in the production of special structural steels where high purity is required to influence the quality of the final products. This work deals with the evolution of steel purity comparing vacuum degassing (VD) and electro slag remelting (ESR) technologies in terms of the chemical composition of non-metallic inclusions and their morphology. The present work primarily studies the creep behavior of special structural steel at two different initial material states (VD and ESR steel) tested in the range from 450 to 650 °C. A rather unique plastometric experimental methodology of accelerated creep testing, which consists of a slow plastic deformation of a material under long-term stress at an elevated temperature, was used to study the behavior of the prepared specimens. The results show that, after remelting the steel, there was an increase in micropurity due to a reduction in the average size and, in particular, a reduction in the maximum size of non-metallic inclusions. The results of creep behavior show a particular difference at 600 °C, where ESR steel shows higher relaxation phase stress values as well as higher creep strength factor values compared with VD steel.

1. Introduction

The current growing demand for steel with exceptional mechanical properties, micropurity and surface and internal quality is forcing metallurgical manufacturers to constantly monitor, improve and innovate their production technology processes [1,2,3]. Special structural steels are primarily used in nuclear power engineering [4,5,6], the aviation industry [7,8,9], healthcare [10,11,12], the defense industry [13,14,15], and special engineering [16,17,18].

These special structural steels can be produced using VD technology [19,20,21] as part of secondary metallurgy. To ensure higher purity, the steel can then be remelted using ESR equipment [22,23,24] as part of tertiary metallurgy. The main objective of the ESR process is to achieve higher purity and the desired microstructure of the remelted metal semi-finished product [25,26,27]. The production of steel using ESR technology is a complex process involving a series of physical–chemical processes, including melting, multiphase steel flow, and chemical reactions (i.e., processes occurring between slag and metal) to solidification [28,29,30].

Steel produced in this way is usually subsequently processed into products with a final shape using plastic deformation methods (conventional [31,32,33], unconventional [34,35,36], or combinations thereof [37,38,39,40]). However, modern manufacturing methods also include powder metallurgy [41,42,43] and additive manufacturing [44,45,46]. The quality and higher usability of steels can be improved by increasing their purity during primary, secondary, or tertiary metallurgy and subsequent casting [47,48,49,50,51] or by performing controlled thermomechanical forming treatments, e.g., with optimized heating used to control the microstructures [52,53,54].

Especially for challenging materials, it is highly important to characterize and optimize their thermomechanical behaviors not only to make the production processes more efficient but also to possibly increase the lifetime of the final products. The thermomechanical behavior of a specific material to be used under challenging high-temperature conditions can be characterized using plastometric tests, such as the accelerated creep test (ACT) [55,56,57]. The methodology of ACT is based on a low-cycle thermomechanical deformation–relaxation process and can be performed using the Gleeble equipment [58,59,60]. During this test, it is possible to dynamically acquire important data on stress, strain (deformation), and temperature [61,62,63].

The steel purity and behavior of the steel especially focus on (high-temperature) fatigue, as has already been studied. Dong et al. [64] studied wettability between slag with different CaF2 contents ranging from 30 to 70 wt. % and non-metallic inclusions during ESR. The results showed that increasing the CaF2 content reduces the apparent contact angle of wetting. This suggests that a higher CaF2 content in the slag increases the resistance of non-metallic inclusions to penetration into the slag. Shi [65] investigated the effect of MgO in slag on the final purity of CrMoV steel after remelting on an ESR equipment. An increase in the MgO content of the slag leads to an increase in the total amount of non-metallic inclusions, while the MgO content remains relatively stable during remelting [66]. Li et al. [67] evaluated the influence of ternary Al2O3-CaO-CaF2 slag during low-frequency ESR. As the CaO content increased, there was a steady decrease in the total number and size of non-metallic inclusions. The lowest number and smallest size of non-metallic inclusions were observed at a CaO content of 20 wt. % in the slag.

Sawada et al. [68] studied the tensile strength and creep rupture properties of CrMoV steel, which is used in high-temperature and high-pressure reactors. The creep tests were conducted at temperatures ranging from 450 to 600 °C. The results were influenced by the previous heat treatment conditions. Chen et al. [69] studied the effects of different stress levels, specifically when applying stresses of 300, 310, and 320 MPa, on the creep and fatigue behavior and cycle life of CrMo steel at 560 °C in a series of stress-controlled creep–fatigue interaction (CFI). The relationship between stress amplitude and average stress on material durability was investigated. Shang et al. [70] conducted steel creep tests under constant load at a temperature of 650 °C at various applied stresses ranging from 110 to 155 MPa. Tests were conducted in both air and a superheated steam environment in order to investigate the interaction between creep and oxidation.

Special structural steels produced by ESR are of wide interest, given the versatility of their application with requirements for a high degree of reliability of steel components. However, information about the creep behavior of structural steels, especially when performed in an accelerated manner, is very limited. The aim of this research was therefore to investigate the (accelerated) creep behaviors of structural steels produced via two technologies; specimens of ESR structural steel and VD structural steel were prepared. This study is supplemented by an assessment of steel purity, with a particular focus on the occurrence of non-metallic inclusions to provide data on the relations between steel purity and creep behaviors of the specimens and on the effects of the different steel production technologies on the overall performance of the specimens.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

Special CrNiMoV steel, manufactured by ŽĎAS, a.s. steelworks, Žďár nad Sázavou, Czech Republic, was used to evaluate the purity of steel and study creep behavior. The average chemical composition of this steel is shown in Table 1. The steel production process consisted of primary metallurgy in the form of melting in an Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) and its subsequent processing in secondary metallurgy equipment in the form of vacuum degassing. The steel produced in this way was then electro slag remelted using tertiary metallurgy on ESR equipment. Structural steel produced using VD technology was compared with structural steel remelted using ESR equipment. Two commercially available slags, AKF 235 and AKF 226, both from ISOMAG GmbH, Kraubath an der Mur, Austria, were used for ESR. Their average chemical compositions are shown in Table 2 and their main properties are shown in Table 3. The main difference between these slags was the content of the two basic ESR slag components, CaF2 and CaO, as well as the content of MgO, which significantly affects the size and quantity of non-metallic inclusions in steel after remelting.

Table 1.

Chemical composition of used structural steel (wt. %).

Table 2.

Chemical compositions of commercially available ESR slags used for remelting (wt. %).

Table 3.

The thermophysical properties of used slags.

2.2. Purity

The aim of the Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) evaluation of non-metallic inclusions in steel was to compare the impact of different steel production technologies on the level of micropurity achieved in terms of the chemical composition and morphology of the non-metallic inclusions in structural steel intended for special applications. The specimens were subjected to analysis of microstructures via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) using a JEOL device of JEOL, Ltd., Akishima, Tokyo, Japan, equipped with EDS and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) detectors. Specimens were taken from forgings that were produced using a variety of different manufacturing technologies. These were VD technology (VD variant), ESR technology using forged electrode remelted under standard AKF 235 slag (ESR forged variant), ESR technology using cast electrode remelted under standard AKF 235 slag (ESR cast AKF 235 variant) and ESR technology using cast electrode remelted under AKF 226 slag with reduced MgO content (ESR cast AKF 226 variant). A total of 32 steel specimens were analyzed. Approximately 10 non-metallic inclusions were analyzed from each specimen. The chemical composition of the non-metallic inclusions and their morphology, i.e., their size and shape, were evaluated.

2.3. Mechanical Properties

To map the long-term strength and thermal resistance of the studied vacuum degassed structural steel as VD steel (VD variant from the purity assessment) and electro slag remelted structural steel as ESR steel (ESR forged variant from the purity assessment), a series of accelerated creep tests (ACT) was carried out. These tests were performed on a Gleeble 3800-GTC thermo-mechanical testing system (Dynamic Systems Inc., Poestenkill, NY, USA) using the Pocket Jaw mobile interchangeable testing unit. The creep behavior was mapped over a wide temperature range from 450 °C to 650 °C in 50 °C increments.

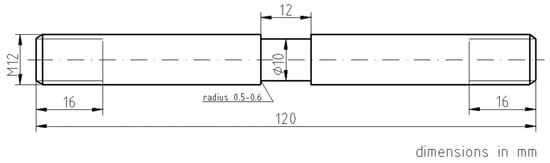

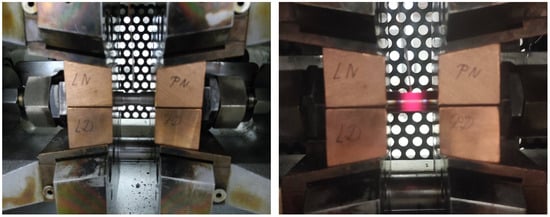

The Gleeble system implements the ACT as a low-cycle thermo-mechanical deformation–relaxation process. Figure 1 shows the schematic of the Gleeble-ACT test specimen, while Figure 2 illustrates its setup in the test chamber and the ACT process itself. The dimensions and positioning of the specimen in the test chamber allow a uniform heating zone to be created in the middle of the specimen’s length (thanks to achieving a balance between direct electrical resistance heating of the specimen and heat flow from the specimen into the cold copper jaws). The portion of material in this zone then undergoes transformation. To better define this zone, the specimen has a reduced diameter in the middle [61,62].

Figure 1.

ACT specimen scheme [61,62].

Figure 2.

Placing the ACT specimen in the test chamber and the course of the test itself.

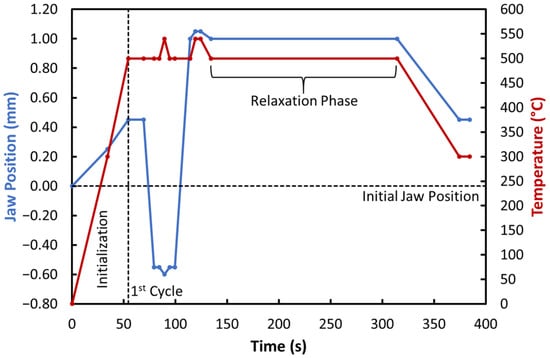

Each test specimen had to be preloaded with a pretension tensile force of approximately 3000 kgf (i.e., about 30 kN) before the ACT itself could begin. The specimen was then heated at a rate of 16 °C·s−1 to the desired initial temperature, which is 200 °C lower than the required test temperature. The ACT procedure itself was based on changes in test temperature and alternating tensile-compressive loading, combined into cycles. An example of a single ACT cycle for a test temperature of 500 °C is shown in Figure 3. Each cycle consisted of identical temperature changes and small variations between tensile and compressive loading. Within each cycle, one relaxation phase always occurred, during which the specimen was subjected to tensile stress (stretched by 1 mm) at the defined test temperature for 3 min. This cyclic pattern was repeated until the integrity of the specimen was compromised (either crack initiation or specimen fracture) or until the prescribed number of cycles was reached (55 in this study). The correct temperature was achieved using direct electrical resistance heating, and the temperature was measured by a pair of type K thermocouple wires (i.e., Ni-Cr (+) and Ni-Al (–)) that were spot-welded to the specimen’s surface at mid-length. The test chamber was maintained under vacuum during the experiment (approximately 10−1 Torr, achieved by a rotary vacuum pump) to prevent oxidation processes.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of one ACT cycle.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of Purity

An evaluation of the identified parameters of non-metallic inclusions in steel was carried out based on the results of analyses of these non-metallic inclusions. The evaluation of steel micropurity focused on the chemical composition, size, and shape of non-metallic inclusions. An evaluation of the chemical composition of non-metallic inclusions found in the steel specimens revealed a total of 50 different types of non-metallic inclusions.

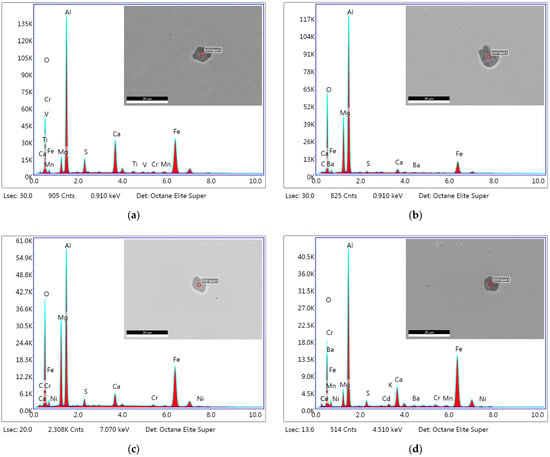

Together with electron microscope images of non-metallic inclusions, the presence of individual elements in the analyzed locations, marked on the images as EDS Spot 1, was graphically depicted. The following images show non-metallic inclusions in steel specimens for individual variants (VD, ESR forged, ESR cast AKF 235, and ESR cast AKF 226). These always represent the most common occurrence of non-metallic inclusions, according to their chemical composition (see Table 4), average size (see Table 5) and shape (see Table 6) for the relevant variant. Figure 4a shows the most common non-metallic inclusion, Al2O3 (53.1%), for the VD variant. This non-metallic inclusion has a size that corresponds to the average non-metallic inclusion size for this variant (10.15 µm). Specifically, it is 10 µm in size and oval-shaped (44%). Figure 4b shows the most common non-metallic inclusion of the Al2O3·MgO type (42.5%) for the ESR forged variant, which has an average size of 10 µm (10.21 μm) and an oval shape (36%). Figure 4c shows representatives of the ESR cast AKF 235 variant, which is a non-metallic inclusion of the Al2O3·MgO type (56.5%) with a size of 8 µm (7.71 µm) and an oval shape (39%). Last but not least, Figure 4d illustrates the most prevalent non-metallic inclusion, Al2O3 (45%), with a size of 8 µm (8.56 µm) and a globular shape (49%) for the ESR cast AKF 226 variant.

Table 4.

The chemical composition of the non-metallic inclusions and their representation in the steel specimens (%).

Table 5.

The size of the non-metallic inclusions for individual variant (μm).

Table 6.

Shares of non-metallic inclusion shapes for individual variant (%).

Figure 4.

Spot chemical analysis of the most typical non-metallic inclusions from specimens of special structural steel for the variants: (a) VD; (b) ESR forged; (c) ESR cast AKF 235; (d) ESR cast AKF 226.

Table 4 shows the values representing the most significant individual types of non-metallic inclusions found in the examined steel specimens. Other types of non-metallic inclusions occurred in quantities representing less than 5% of the total volume of non-metallic inclusions analyzed.

The results of the analysis of the chemical composition of non-metallic inclusions were examined in terms to the representation of non-metallic inclusions in steel specimens according to the method of steel production. Pollution was found in steel specimens produced using VD technology, particularly in the form of Al2O3 (53.1%) and Al2O3·MgO (25.9%) non-metallic inclusions. In the case of the ESR forged variant, the specimens contained 37.5% and 42.5% non-metallic inclusions of Al2O3 and Al2O3·MgO, respectively. Steel specimens of the ESR cast AKF 235 variant contained 56.5% Al2O3·MgO and 11.8% TiN non-metallic inclusions. In the ESR cast AKF 226 variant, the specimens contained 45% non-metallic inclusions of Al2O3 and 32.5% Al2O3·MgO.

After determining the chemical composition of non-metallic inclusions, the size of non-metallic inclusions was evaluated. A total of 32 specimens (8 for each production variant) were analyzed and 10 non-metallic inclusions were evaluated for each specimen. In total, 320 non-metallic inclusions were compared in terms of their size according to the production technology used. Table 5 shows the minimum, maximum and average sizes of the non-metallic inclusions that were measured.

As can be seen clearly in Table 5, the level of steel micropurity achieved in terms of the average size of non-metallic inclusions differs between the monitored production technologies. As expected, the lowest contamination of steel with non-metallic inclusions was found in the case of material production on ESR equipment from cast electrode (ESR cast variants). Steel processed only by VD technology without subsequent remelting on ESR equipment was found to have higher values of the average size of non-metallic inclusions. At the same time, the results show that material produced using ESR technology from forged electrode exhibits a comparable level of micropurity in terms of the average size of non-metallic inclusions to that produced using VD technology. The results also show that the size distribution of non-metallic inclusions for the VD variant is shifted towards a higher average size of individual non-metallic inclusions compared to the ESR cast AKF 235 variant. The size distribution of non-metallic inclusions confirms that ESR technology contributes to reducing the number of non-metallic inclusions between 10 and 18 μm in size and removes those larger than 18 μm. It is also clear that the size distribution of non-metallic inclusions is comparable for ESR cast AKF 235 variant and ESR cast AKF 226 variant. A greater dispersion of values towards higher-size non-metallic inclusions is evident in steel processed on ESR equipment using forged electrode (ESR forged variant).

Last but not least, non-metallic inclusions were also quantified according to their shape. Table 6 shows the individual percentage shares of detected non-metallic inclusions in the monitored steel specimens.

Globular and oval non-metallic inclusions predominate in all monitored groups according to the type of steel production (VD, ESR forged, ESR cast AKF 235, or ESR cast AKF 226 variant). Furthermore, from the results in Table 6, we can conclude that, in ESR material from cast electrode (ESR cast AKF 235), there is a reduced proportion of elongated non-metallic inclusions but an increased proportion of sharp-edged non-metallic inclusions. It is also evident that, in ESR material from a cast electrode remelted under slag with reduced MgO content (ESR cast AKF 226 variant), there is a higher proportion of globular non-metallic inclusions at the expense of oval non-metallic inclusions.

3.2. Evaluation of Mechanical Properties

During the ACT test, the loading force F (N) and the actual values of temperature and jaw displacement Δl (mm) are recorded. From the measured values of F and Δl, the engineering strain e (–) and the corresponding stress σ (MPa) are then evaluated, according to the following relations:

where the values l0 (mm) and d0 (mm) correspond to the initial length and diameter of the reduced central section of the test specimen, i.e., l0 = 12 mm and d0 = 10 mm (see the schematic in Figure 1).

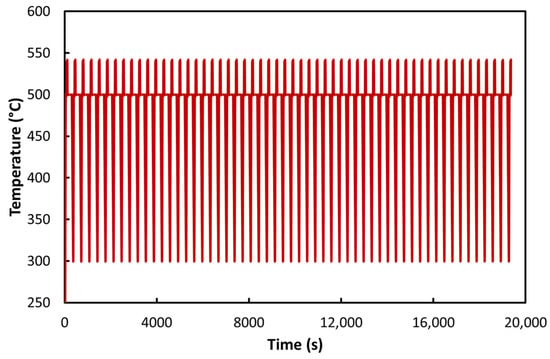

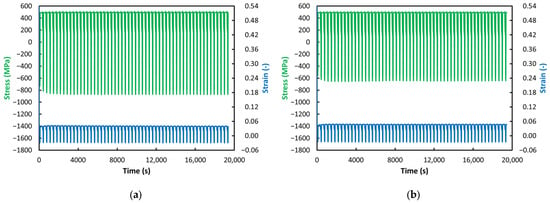

Figure 5 shows an example of the temperature–time relationship obtained for the ACT process carried out at 500 °C, while Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 present the strain–time and stress–time relationships for all tested specimens. Regarding the temperature dependence, Figure 5 shows a typical temperature profile for 500 °C and 55 cycles, as can be inferred from Figure 3. A similar profile can be observed in the other tests as well.

Figure 5.

Temperature dependence for a test temperature of 500 °C and 55 cycles.

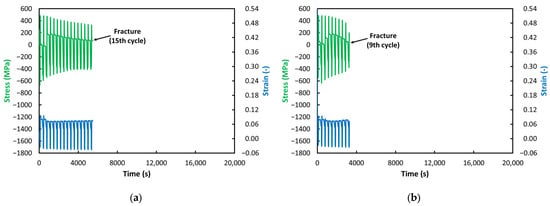

Figure 6.

ACT at 650 °C: (a) VD (15 Cycles); (b) ESR (9 Cycles).

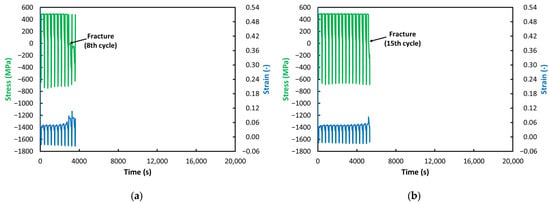

Figure 7.

ACT at 600 °C: (a) VD (8 Cycles); (b) ESR (15 Cycles).

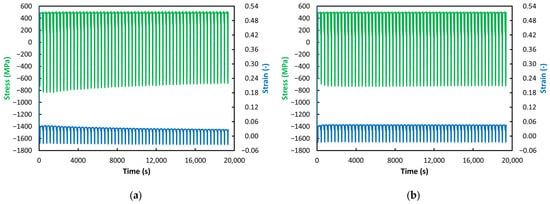

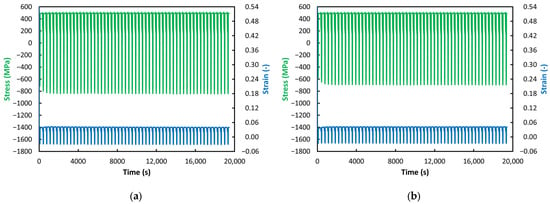

Figure 8.

ACT at 550 °C: (a) VD (55 Cycles); (b) ESR (55 Cycles).

Figure 9.

ACT at 500 °C: (a) VD (55 Cycles); (b) ESR (55 Cycles).

Figure 10.

ACT at 450 °C: (a) VD (55 Cycles); (b) ESR (55 Cycles).

Much more significant are the trends in the time-dependent behavior of strain and stress (see Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). The VD and ESR steels tested at 650 °C (see Figure 6) underwent a typical ACT course, in which the specimen’s strain gradually increases with each subsequent cycle and the stress in the relaxation phases decreases accordingly. The only exceptions are the first two (VD) or three (ESR) cycles, in which these trends appear to differ. Interestingly, the stress in these initial cycles is much lower than in the later stages, and the strain is paradoxically the highest—as if the material were offering virtually no resistance to deformation. Nevertheless, when considering the trends from the third (VD) and fourth (ESR) cycles onward, the progressively increasing strain levels and decreasing stress levels indicate gradual material degradation—the development of a crack. The drop of stress to zero can then be associated with a loss of specimen cohesion, as a highly developed crack is visible along the specimen perimeter in both steels. It is evident that, in the ESR steel, this failure occurred six cycles earlier, although this can be considered a negligible difference. Everything else—stress level as well as strain—is practically identical. This suggests a certain similarity in the creep resistance of the two examined materials.

If the testing temperature is reduced by just 50 °C, the trends we observed above take on a dramatically different character (see Figure 7). Compared with the 650 °C tests (see Figure 6), lowering the temperature to 600 °C results, for the ESR steel (see Figure 7b), in a significant reduction in the material’s ability to deform; the strain values shift closer to zero (both in tension and compression). However, we still observe a gradual increase in strain with an increasing number of cycles, as we did at 650 °C.

The VD steel behaves somewhat differently at this temperature (see Figure 7a). Its ability to deform is slightly higher than that of the ESR steel. Most likely for this reason, failure in the VD steel occurred seven cycles earlier at this temperature. Nevertheless, both steels exhibit the same trend with respect to stress (see Figure 7): the stress during the relaxation phase remains essentially constant throughout the entire test. In contrast to the behavior at 650 °C (see Figure 6), we do not observe a gradual decrease in stress toward zero that would indicate an approaching loss of cohesion. While at 650 °C the crack developed gradually, at 600 °C both specimens experienced an abrupt and complete fracture.

With further decreases in temperature, not only does the previously observed gradual decrease in stress toward zero disappear but the phenomenon of gradually increasing strain also vanishes (see Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). At temperatures of 550 °C and below, the strain values in the relaxation phase are essentially constant and even nearly identical—approximately 0.04 or slightly above (with the exception of the VD steel at 550 °C, see Figure 8a). A more detailed examination of the jaw-movement record showed that specimens tested at 550 °C and below could not be elongated by the prescribed 1 mm during the relaxation phase but only by about 0.8 mm. This resulted in the reduced and constant strain levels mentioned above. These observations can be attributed to material strengthening due to decreasing temperature under load. As expected, a lower loading temperature leads to increased resistance to creep. As noted above, a significant deviation from this trend is observed in the VD steel at 550 °C (see Figure 8a). Its ability to deform paradoxically decreases markedly with increasing cycle count, suggesting a bizarre phenomenon in which the material’s strength—and thus its ability to resist creep—increases over time. The stress behavior is unusual as well; although the stress in the relaxation phase remains constant, a gradual decrease in compressive stress is observed during the compression phase of the cycle, meaning the material should be offering less and less resistance to deformation, similar to what occurs at 650 °C. However, this contradicts the observed decrease in strain.

As for the stress values, as noted above, from 600 °C downward, these values remain at the same level throughout the entire test during the relaxation phases; the expected decrease does not occur and the stress levels are even identical across the individual test temperatures (see Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10). Differences can therefore be found only in the compression phase. For the VD steel, it can be observed that, at temperatures from 650 °C down to 550 °C, the stress in the compression phase decreases with increasing cycle count (the values move from negative toward zero)—very pronounced at 650 °C and 550 °C (see Figure 6a and Figure 8a) and less pronounced at 600 °C (see Figure 7a). At 500 °C and 450 °C, the stress values in the compression phase for VD steel are essentially constant—just as in the relaxation phase (see Figure 9a and Figure 10a).

In contrast, for the ESR steel, a constant stress level in the compression phase appears already at 600 °C and below. This suggests that ESR steel may be slightly more creep-resistant up to 600 °C. However, when comparing the stress levels in the compression phase at 600 °C and lower (see Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10), the graphs show that VD steel exhibits a higher compressive stress level than ESR steel at the same temperature. This difference is most pronounced at 500 °C, where VD steel shows compressive stress approaching 900 MPa (see Figure 9a), whereas ESR steel is only slightly above 600 MPa (see Figure 9b). A similar difference is observed at 450 °C (see Figure 10a,b). This observation may indicate higher creep resistance in favor of VD steel.

Based on the experimental ACT data obtained, the value of the so-called creep strength factor FACT (MPa) for the given tested material can be determined [61,62]:

where RS (MPa) is the tensile relaxation stress, representing the average value of the stress σ (2) calculated from all ACT cycles during their relaxation phase. The parameter PACT then embodies the combined effect of test duration and test temperature [61,62]:

where T (K) and t (ks) represent the test temperature and duration. This parameter therefore ensures the comparability of results obtained from different ACT experiments (materials and temperatures). The values of the above quantities for the investigated material are then given in Table 7.

Table 7.

Comparison of achieved ACT results.

The results in Table 7 clearly show that both investigated materials exhibit the highest creep resistance at temperatures of 550 °C and below. Even after reaching 55 cycles, neither fracture nor cracking occurred. The stress values in the relaxation phase are practically identical for these temperatures and higher than at the two higher temperatures, regardless of the steel type (compare 492 MPa for the VD steel and 491 MPa for the ESR steel). Only the VD steel at 550 °C deviates slightly, with an RS value about 4 MPa lower.

At first glance, the creep strength factor (3) values may appear confusing, as they should increase with decreasing temperature and thereby indicate improved creep resistance. However, this expected trend is visible only in the temperature range from 650 °C to 550 °C. At 500 °C and 450 °C, a paradoxical decreasing trend appears. This, however, is caused by the PACT parameter (4): with the test duration held constant (limited by the maximum number of cycles), decreasing temperature inevitably reduces PACT and thus also the FACT factor (3).

It is rather difficult to estimate how many cycles would be required to reach loss of cohesion at 550 °C and below. However, given the logarithmic dependence of the PACT parameter on time (and therefore the logarithmic dependence of the FACT factor on time), one can expect that, even with a significantly increased time to fracture, FACT values would rise only very slightly (especially under constant stress levels in the relaxation phase). Further increasing the number of cycles therefore has no practical significance. However, this does not change the fact that—assuming the number of cycles to failure increases with decreasing temperature—the FACT factor should also increase (albeit slowly). Thus, the temperature of 450 °C should demonstrate the greatest creep resistance.

If we compare the creep resistance of VD and ESR steels, the results in Table 7 show that, at temperatures of 550 °C and below, both steels exhibit practically identical performance. However, at 650 °C and 600 °C, the results tilt the balance in favor of the ESR steel. At these temperatures, ESR steel shows higher relaxation-phase stress values as well as higher creep-strength factor values compared with VD steel. The difference is particularly striking at 600 °C.

An interesting observation is that the specimens of both steels at the two higher temperatures failed by the same type of loss of cohesion (crack formation at 650 °C and complete fracture at 600 °C) but with opposite numbers of cycles. Unexpectedly, the VD steel failed earlier at 600 °C rather than at 650 °C. Either way, if we disregard the 600 °C temperature, the creep resistance appears to be almost identical for both steels. These two specific tested variants (VD and ESR forged steel) can be recommended for long-term use at temperatures up to 550 °C.

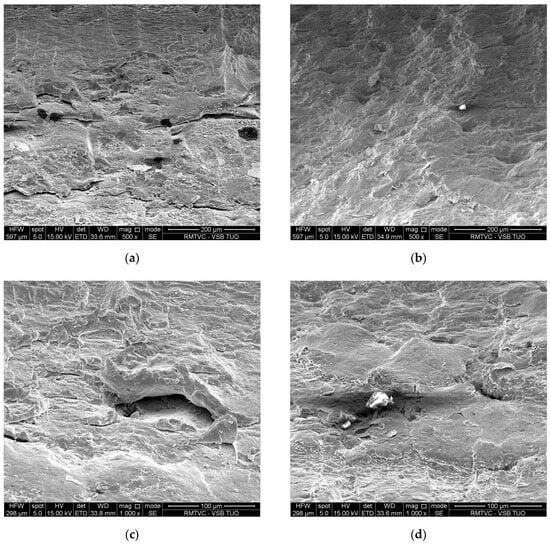

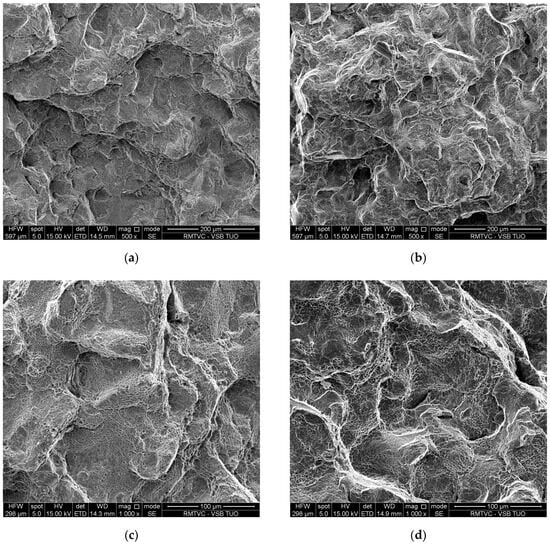

Last but not least, an evaluation of cracks and fracture surfaces in the relevant specimens was also included in the ACT results. The cracks are illustrated in Figure 11a,c for the VD steel and Figure 11b,d for the ESR steel. The fracture surfaces are illustrated in Figure 12a,c for the VD steel and Figure 12b,d for the ESR steel.

Figure 11.

The cracks at an ACT temperature of 650 °C are shown by electron microscope at a magnification of 500 and 1000 for each specimen: (a,c) VD steel; (b,d) ESR steel.

Figure 12.

The fracture surfaces at an ACT temperature of 600 °C are shown by electron microscope at a magnification of 500 and 1000 for each specimen: (a,c) VD steel; (b,d) ESR steel.

Structural steel after VD and after ACT at a temperature of 650 °C (see Figure 11a,c) shows significant formation of open cavities, which are mainly oriented in the direction of deformation. These cavities are relatively large and have irregular, plastically deformed edges, indicating significant local creep deformation. The defect areas suggest that the damage was probably initiated at grain boundaries or in areas of local stress concentration, followed by coalescence of creep cavities. The character of surface corresponds to an advanced stage of creep failure, whereby cavities gradually open up and connect with each other. In contrast, for ESR material, the surface after ACT at a temperature of 650 °C (see Figure 11b,d) is more compact and homogeneous, with smaller and more localized defects, and the edges of the cavities are sharper, indicating a lower degree of plastic deformation. The observed defect has a smaller scope and is partially filled with a non-metallic inclusion or a fragment of material that was formed during the process of deformation. The overall character of material failure ESR indicates slower initiation and growth of creep cavities, resulting from reduced non-metallic inclusions and a refined microstructure. Compared to VD steel, which exhibits a higher degree of local creep deformation, ESR steels increase creep resistance and slow down microstructure degradation.

The fracture surface of structural steel after VD and after ACT at a temperature of 600 °C (see Figure 12a,c) shows a significantly plastically deformed character. The surface consists of coarser, irregular areas that correspond to the coalescence of creep cavities. The heterogeneous morphology of the fracture is also evident. This structure suggests that the fracture originated and spread due to gradual creep damage, primarily resulting from the nucleation and growth of cavities at grain boundaries, followed by their coalescence. Based on the observed morphology, the fracture can be classified as a ductile creep fracture. In contrast, the fracture surface of structural steel after ESR and after ACT at a temperature of 600 °C (see Figure 12b,d) exhibits a finer morphology and more homogeneous structure. The surface consists of more evenly distributed plastically deformed areas. Compared to the state after VD, the fracture surface is less rugged and more compact. This indicates that creep deformation is distributed more uniformly throughout the material volume. There are no significant visible initiators of fracture in the form of larger defects or clusters of non-metallic inclusions. This is consistent with the higher metallographic purity and homogeneity of the material after ESR. The character of the fracture can also be described as a ductile creep fracture but with slower damage kinetics and less localized plastic deformation.

4. Discussion

When producing special structural steels, the high purity required must correspond to the quality of tertiary metallurgy. Performance analyses and comparisons of materials produced by secondary metallurgy and materials subsequently processed by tertiary metallurgy revealed differences between individual materials in terms of purity and related creep behavior.

The results of the steel purity assessment confirmed the assumption that remelting in the ESR would improve the micropurity of the steel. Regarding the overall chemical composition of the non-metallic inclusions found in all the studied variants, the most prevalent were based on either Al2O3 or Al2O3·MgO [71]. Sources of aluminum and magnesium included non-metallic inclusions from the original ingot and ESR slag containing oxides of both metals. Material processed using ESR technology under standard slag contains a higher proportion of non-metallic inclusions based on Al2O3·MgO and a lower proportion of non-metallic inclusions based on Al2O3 than material processed only by the VD process. This difference can be attributed to the higher MgO content (3 wt.%) in ESR slag [72]. The same applies to material processed using ESR technology under slag with a reduced MgO content (1.5 wt.%) but to a significantly lesser extent. Clearly, processing cast electrodes using ESR technology significantly reduces the average size of non-metallic inclusions. After processing steel on an ESR, there is also a significant reduction in the maximum size of non-metallic inclusions compared to VD technology [73]. Processing steel on an ESR using slag with reduced MgO content results in the smallest amount of the smallest sizes of non-metallic inclusions in the steel. The aim is to achieve such a quantity, chemical composition, size, shape, and arrangement of non-metallic inclusions in steel that have the least impact on the required properties [74]. The results of accelerated creep tests correspond to the results of micropurity evaluation of steel. The tested VD and ESR forged variants showed similar micropurity ratings, whether in terms of the total amount of Al2O3 and Al2O3·MgO non-metallic inclusions or the average size of non-metallic inclusions, which was 10.15 and 10.21 µm, respectively. This is related to the similar results of creep behavior because non-metallic inclusions can cause crack and subsequent fracture [75]. Therefore, it is assumed that the results of the creep behavior tests would be significantly better for steel processed on ESR equipment when using specimens from cast ESR electrodes.

5. Conclusions

This research aimed to analyze micropurity in detail and subsequently study the creep behavior of special structural steel produced using vacuum degassing and electro slag remelting technologies. The influence of technologies of vacuum degassing, use of electro slag remelting on a cast electrode, use of electro slag remelting on a forged electrode, and the influence of using slag with a reduced MgO content on the chemical composition and morphology of non-metallic inclusions in steel was compared. The main conclusions of this research are:

- Comparing electro slag remelting technology with the vacuum degassing process demonstrated a significant improvement in purity, also documented by the achieved values for the average size of non-metallic inclusions.

- A comparison of electro slag remelting material from cast and forming steel revealed significant differences in the achieved value of average size of non-metallic inclusions. Smaller non-metallic inclusions were found in the electro slag remelting material from the cast electrode.

- The electro slag remelting process affects the morphology of Al2O3 non-metallic inclusions, and the MgO concentration in electro slag remelting slag affects the proportion of Al2O3 and MgO non-metallic inclusions in the produced steel.

- The highest creep resistance for both investigated materials (after vacuum degassing and electro slag remelting technology) is achieved at temperatures of 550 °C and below. No loss of cohesion was observed even after reaching 55 cycles.

- Temperatures of 600 °C and above cannot be recommended for long-term service loading of the investigated materials, given the very low number of cycles to failure during the accelerated creep test.

- Due to the low number of cycles to failure, exposing both materials (after vacuum degassing and electro slag remelting technology) to temperatures of 600 °C and 650 °C may be risky even under short-term loading conditions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.W.; methodology, J.W., P.O. and F.V.; validation, J.W. and F.V.; formal analysis, J.W.; investigation, J.W., P.O. and F.V.; resources, J.W. and R.K.; data curation, J.W. and F.V.; writing—original draft preparation, J.W.; writing—review and editing, P.O., F.V. and R.K.; visualization, J.W. and P.O.; supervision, R.K.; project administration, J.W.; funding acquisition, J.W. and R.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project TQ03000386 Optimization of Technological Parameters of Electro Slag Remelting of Steels for Special Applications co-financed by the state budget by the Technology agency of the Czech Republic under the SIGMA Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw/processed data required to reproduce these findings cannot be shared at this time due to technical or time limitations.

Acknowledgments

The cooperation of Lenka Kunčická, VSB—Technical University of Ostrava, Pavel Fila and Martin Balcar, ŽĎAS, a.s. is greatly appreciated.

Conflicts of Interest

Author František Vrána was employed by the company ŽĎAS, a.s., Žďár nad Sázavou, Czech Republic. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Hlaváč, L.M.; Kocich, R.; Kunčická, L.; Hlaváčová, I.M.; Gřunděl, J. Effect of thermomechanical post-processing of additively manufactured AISI 316L steel on abrasive water jet wear. Wear 2025, 570, 205952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunčická, L.; Kocich, R.; Németh, G.; Dvořák, K.; Pagáč, M. Effect of post process shear straining on structure and mechanical properties of 316 L stainless steel manufactured via powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2022, 59, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Li, S.; Xiao, Y.; Li, R.; Li, X.; Han, X.; Chen, J. Exploring structural origins responsible for the exceptional mechanical property od additively manufactured 316L stainless steel via in-situ and comparative investigations. Int. J. Plast. 2023, 170, 103769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litovchenko, I.Y.; Akkuzin, S.A.; Polekhina, N.A.; Almaeva, K.V.; Moskvichev, E.N.; Kim, A.V.; Linnik, V.V.; Chernov, V.M. New low-activation austenitic steel for nuclear power engineering. Lett. Mater. 2022, 12, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Dai, J.; Li, Y.; Dai, X.; Xie, C.; Li, L.; Chen, L. Progress of Steels for Nuclear Reactor Pressure Vessels. Materials 2022, 15, 8761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.; Kim, M.; Yoon, J.; Hong, J. Characterization of high strength and high toughness Ni–Mo–Cr low alloy steels for nuclear application. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2010, 87, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanovski, V.; Frantskevich, V.; Kazlouski, V.; Kasach, A.; Paspelau, A.; Hedberg, Y.; Romanovskaia, E. Inappropriate cleaning treatments of stainless steel AISI 316L caused a corrosion failure of a liquid transporter truck. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 117, 104938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z. Creep-resistant aeroengine shaft steels: Precipitates and consequences. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2019, 35, 1405–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, R.; Liu, D.; Chen, J.; Wang, J. Investigation of Microstructure and Properties of Ultra-High Strength Steel in Aero-Engine Components following Heat Treatment and Deformation Processes. Metals 2023, 13, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunčická, L.; Kocich, R.; Lowe, T.C. Advances in metals and alloys for joint replacement. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2017, 88, 232–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shang, C.; Wu, H.-H.; Zhang, C.; Hou, F.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Gao, J.; Zhao, H.; Mao, X. Recent developments in low-expansion alloys for high-performance applications. Rare Met. 2025, 44, 7088–7105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Li, J. Shock and Spallation Behavior of a Compositionally Complex High-Strength Low-Alloy Steel under Different Impact Stresses. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhan, D.; Jiang, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y. Progress on improving strength-toughness of ultra-high strength martensitic steels for aerospace applications: A review. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 23, 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, H. Experimental Study on the Dynamic Behavior of a Cr-Ni-Mo-V Steel under Different Shock Stresses. Metals 2023, 13, 663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.-F.; Lu, H.-H.; Shen, X.-Q. Coupled effects of banded structure and carbide precipitation on mechanical performance of Cr-Ni-Mo-V steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 832, 142478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Huang, B.; Zhang, C.; Sun, W.; Zheng, K.; Hu, J. Strengthening mechanism and precipitate evolution of a multi-application special engineering steel designed based on a hybrid idea. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 942, 169053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Jo, M.C.; Sohn, S.S.; Zargaran, A.; Ryu, J.H.; Kim, N.J.; Lee, S. Novel medium-Mn (austenite + martensite) duplex hot-rolled steel achieving 1.6 GPa strength with 20% ductility by Mn-segregation-induced TRIP mechanism. Acta Mater. 2018, 147, 247–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, K.; Eckert, J. Effect of tempering and deep cryogenic treatment on microstructure and mechanical properties of Cr-Mo-V-Ni steel. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2020, 787, 139520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, L. Fluid flow, slag entrainment, and composition evolution of slag inclusions during vacuum degassing refining. Metall. Res. Technol. 2024, 121, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Xu, J.; Luo, D.; Liu, S.; Zhou, Z.; Lai, C. Numerical simulation on dehydrogenation behavior during argon blowing enhanced vacuum refining process of high-quality steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 6481–6493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konar, B.; Quintana, N.; Sharma, M. Modeling and Optimization of the Vacuum Degassing Process in Electric Steelmaking Route. Processes 2025, 13, 2368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walek, J.; Odehnalová, A.; Kocich, R. Analysis of Thermophysical Properties of Electro Slag Remelting and Evaluation of Metallographic Cleanliness of Steel. Materials 2024, 17, 4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walek, J.; Kunčická, L. Effect of Oxide Systems on Purity of Tool Steels Fabricated by Electro Slag Remelting. Molecules 2025, 30, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Midhun, P.M.; Basu, S. Influence of SiO2 on the Structure and Melting Characteristics of CaF2-CaO-Al2O3-SiO2 Slag for Use in Electroslag Remelting. J. Sustain. Metall. 2025, 11, 941–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agham, M.C.; Khanmiri, M.H.; Mousalou, H.; Yazdani, S. Design and high strain rate response of a nanostructured bainitic steel for enhanced austenite stability. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 37, 2203–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.R.; Dey, S.; Florist, V.; Pai, N.; Sadhasivam, M.; Tripathy, D.; Pradeep, K.G.; Murty, S. Understanding the anomalous mechanical behavior of Monel K500 at cryogenic temperatures: The defining role of twinning. J. Alloys Compd. 2025, 1032, 181066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, W. Mechanism of Formation and Evolution of Slag Shells in the Electroslag Remelting Process Utilizing Two Series-Connected Electrodes. Steel. Res. Int. 2025, 2500440, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Wang, J.; Chen, H. Deformation Behavior and Grain Refinement during Multi-pass Hot Compression of Mn18Cr18N Steel. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025, 34, 23463. [Google Scholar]

- Suo, H.; Liu, F.; Kang, C.-P.; Li, H.; Jiang, Z.; Geng, X. Effects of Pressure on Nitrogen Content and Solidification Structure during Pressurized Electroslag Remelting Process with Composite Electrode. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 2400520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Deshmukh, A.; Joshi, A.; Ballal, N.B.; Basu, S. Chromium Alloying in Steel during Electroslag Refining by Cr2O3 Addition to Slag. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 534–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; Sun, X.; Guo, X.; Zhao, Y.; Yin, X.; Du, Z. Achieving 1.7 GPa Considerable Ductility High-Strength Low-Alloy Steel Using Hot-Rolling and Tempering Processes. Materials 2024, 17, 4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Zhao, J.; Du, W.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Z. Effects of rolling processes on ridging generation of ferritic stainless steel. Mater. Charact. 2018, 137, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojeda-López, A.; Botana-Galvín, M.; González-Rovira, L.; Botana, F.J. Numerical Simulation as a Tool for the Study, Development, and Optimization of Rolling Processes: A Review. Metals 2024, 14, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeisl, S.; Lassnig, A.; Hohenwater, A.; Mendez-Martin, F. Precipitation behavior of a Co-free Fe-Ni-Cr-Mo-Ti-Al maraging steel after severe plastic deformation. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 2022, 833, 142416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straumal, B.B.; Kulagin, R.; Klinger, L.; Rabkin, E.; Straumal, P.B.; Kogtenkova, O.A.; Baretzky, B. Structure Refinement and Fragmentation of Precipitates under Severe Plastic Deformation. A review. Materials 2022, 15, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kunčická, L.; Walek, J.; Kocich, R. Deformation Behavior of La2O3-Doped Copper during Equal Channel Angular Pressing. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2025, 27, 2402412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocich, R.; Kunčická, L. Optimizing structure and properties of Al/Cu laminated conductors via severe shear strain. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 956, 170124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Chen, X.; Hammond, V.; Kecskes, L.J.; Mathaudhu, S.N.; Kondoh, K.; Wei, Q. The effect of rolling on the microstructure and compression behavior of AA5083 subjected to large-scale ECAE. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 695, 3589–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshizumi, H.; Yuasa, M.; Miyamoto, H.; Somekawa, H. Influence of different wrought processes on the microstructure and texture evolution in AZ31 magnesium alloys. Mater. Charact. 2024, 217, 114446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Guo, T.; Feng, R.; Qian, D.; Huang, D.; Zhang, G.; Ling, D.; Ding, Y. High strength high conductivity copper prepared by C-ECAP and Cryo-rolling. Mater. Charact. 2024, 208, 113665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sufiyarov, V.S.; Razumov, N.G.; Mazeeva, A.K.; Razumova, L.V.; Popovich, A.A. Modern Methods of Creation and Application of Powder Ferritic/Martensitic ODS Steels. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2024, 66, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmetov, A.S.; Eremeeva, Z.V. Investigation of the Structure of Sintered Blanks from Powder Mixture of R6M5K5 High-Speed Steel Containing Diffusion-Alloyed Powder. Metallurgist 2022, 66, 299–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, H.; Dabhade, V.V.; Blais, C. Analysis of machining green compacts of a sinter-hardenable powder metallurgy steel: A perspective of material removal mechanism. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 41, 430–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, J.; Yim, S.; Yamanaka, K.; Aoyagi, K.; Wang, H.; Chiba, A. Multi-material additive manufacturing of steel/Al alloy by controlling the liquid/solid interface in laser beam powder bed fusion. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 96, 104529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotov, A.; Kantyukov, A.; Popovich, A.; Sufiiarov, V. A Review on Additive Manufacturing of Functional Gradient Piezoceramic. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Kosiba, K.; Suryanarayana, C.; Lu, T.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Prashanth, K.G. Feedstock preparation, microstructures and mechanical properties for laser-based additive manufacturing of steel matrix composites. Int. Mater. Rev. 2023, 68, 1192–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, L.; Geng, Y.; Zang, X.; Jing, Y.; Li, D.; Thomas, B.G. Air Gap Measurement During Steel-Ingot Casting and Its Effect on Interfacial Heat Transfer. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2021, 52, 2224–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernhard, M.; Kavic, D.; Presoly, P.; Wi, T.-G.; Park, W.-B.; Rossler, R.; Jungreithmeier, A.; Ilie, S.; Bernhard, C.; Kang, Y.-B. A Hybrid Up-date of the Fe-Si System by DSC, Thermodynamic Modeling and Statistical Learning from Ladle Refining Data of Electrical Steels. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2025, 56, 5682–5699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sviželová, J.; Tkadlečková, M.; Michalek, K.; Walek, J.; Saternus, M.; Pieprzyca, J.; Merder, T. Numerical Modelling of Metal Refining Process in Ladle with Rotating Impeller and Breakwaters. Arch. Metall. Mater. 2019, 64, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, R.; Zhang, C.; Ren, Y.; Zhang, L. Kinetic model for the generation and accumulation of Al2O3 in mold flux during the continuous casting of a Fe-Al-Mn-C steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2025, 35, 5137–5146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, M.; Zhang, M. Development of a Novel Strand Reduction Technology for the Continuous Casting of Homogeneous High-Carbon Steel Billet. Steel Res. Int. 2023, 94, 2200740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohaeri, E.; Omale, J.; Rahman, K.M.M.; Szpunar, J. Effect of post-processing annealing treatments on microstructure development and hydrogen embrittlement in API 5L X70 pipeline steel. Mater. Charact. 2020, 161, 110124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walek, J.; Kocich, R.; Kunčická, L. Adjusting recrystallization kinetics of WNiCo alloy by intensive shear strain. Int. J. Refract. Met. Hard Mater. 2025, 131, 107219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunčická, L.; Walek, J.; Kocich, R. Microstructure Development of Powder-Based Cu Composite During High Shear Strain Processing. Metals 2024, 14, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoddam, S.; Solhjoo, S.; Hodgson, P.D. State of the art methods to post-process mechanical test data to characterize the hot deformation behavior of metals. Adv. Mech. Eng. 2021, 13, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Sun, J.; Yang, Y.; Liu, B.; Si, Y.; Zhou, J. Finite Element Analysis of Dynamic Recrystallization Model and Microstructural Evolution for GCr15 Bearing Steel Warm-Hot Deformation Process. Materials 2023, 16, 4806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opěla, P.; Walek, J.; Kopeček, J. Machine Learning Techniques in Predicting Hot Deformation Behavior of Metallic Materials. Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 142, 713–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koptseva, N.V.; Nikitenko, O.A.; Efimova, Y.Y. Study of Microstructure Formation of Carbon Steel Under High-Speed and Multicycle Hot Plastic Compressive Deformation Using A Gleeble 3500 Unit. Met. Sci. Heat Treat. 2016, 58, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosmatsky, Y.I.; Barichko, B.V.; Fokin, N.V.; Nikolenko, V.D. Application of the Gleeble 3800 System in Developing Hot Pipe Extrusion and Pipe End Upsetting Technologies. Metallurgist 2021, 65, 404–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhakumari, A.; Senthilkumar, T.; Mahadevan, G.; Ramasamy, N. Interface and microstructural characteristics of titanium and 304 stainless steel dissimilar joints by upset butt welding using a Gleeble thermo mechanical simulator. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 26, 7460–7470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziej, S.T. Simulative Accelerated Creep Test on Gleeble. Mater. Sci. Forum 2010, 638–642, 2646–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziej, S.T. Low-cycle thermal-mechanical fatigue as an accelerated creep test. Procedia Eng. 2010, 2, 349–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandziej, S.T.; Vyrostkova, A.; Solar, M. Accelerated Creep Testing of New Creep-Resisting Weld Metals. Weld. World 2010, 54, R160–R172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, J.; Jiang, Z.; Fang, J.; Li, W.; Sun, C. Study on the wettability behaviour between electroslag remelting slag and inclusions. Ironmak. Steelmak. 2025, 52, 893–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C. Deoxidation of Electroslag Remelting (ESR)—A Review. ISIJ Int. 2020, 60, 1083–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Wang, H.; Li, J. Effects of Reoxidation of Liquid Steel and Slag Composition on the Chemistry Evolution of Inclusions During Electroslag Remelting. Metall. Mater. Trans. B 2018, 49, 1675–1689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Wang, Y.; Hu, Q.; Wang, B.; Yao, L.; Chang, L.; Shi, X. Influence of slag composition on the cleanliness of electroslag igot during low frequency electroslag remelting. Metall. Res. Technol. 2025, 122, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, K.; Taniuchi, Y.; Sekido, K.; Nojima, T.; Kimura, K. Creep properties and analysis of creep rupture data of 2.25Cr-1Mo-0.3V steels. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. Methods 2022, 2, 198–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L. Creep-Fatigue Interaction Life Prediction and Fracture Behavior of 1.25Cr0.5Mo Steel at 560 °C. Steel Res. Int. 2025, 96, 148–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, C.G.; Wang, M.L.; Zhou, Z.C.; Lu, Y.H.; Yagi, K. Study on the Mechanism of Oxidation-Accelerated Creep Damage of P92 Steel in 650 °C Superheated Steam. High Temp. Corros. Mater. 2025, 102, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Porter, D.; Komi, J.; Heikkinen, E.-P.; Eissa, M.; El Faramawy, H.; Mattar, T. The Effect of Electroslag Remelting on the Cleanliness of CrNiMoWMnV Ultrahigh-Strength Steels. J. Min. Metall. Sect. B Metall. 2019, 55, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Lee, M.J.; Su, Y.; Mu, W.; Kim, D.S.; Park, J.H. Evolution od nonmetallic inclusions in 80-t 9CrMoCoB large-scale ingots during electroslag remelting process. Int. J. Miner. Metall. Mater. 2024, 31, 1525–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Li, B.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, T.; Chai, Y.; Wu, X. Oxygen transport behavior and characteristics of nonmetallic inclusions during vacuum electroslag remelting. Vacuum 2019, 164, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Ma, G.; Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Li, Z. Evolution of MnS and MgO·Al2O3 inclusions in AISI M35 steel during electroslag remelting. J. Iron Steel Res. Int. 2021, 28, 1605–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Meng, T.; Su, Y.; He, X.; Guo, Z.; Wu, D.; Ma, T.; Li, W. The effect of inclusions and pores on creep crack propagation of linear friction welded joints of GH4169 superalloy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 29, 4636–4649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.