Abstract

Wind turbine blades (WTBs) are inevitably exposed to harsh environmental conditions, leading to surface damages such as cracks and corrosion that compromise power generation efficiency. While UAV-based inspection offers significant potential, it frequently encounters challenges in handling irregular defect shapes and preserving fine edge details. To address these limitations, this paper proposes DMR-YOLO, an Improved Wind Turbine Blade Surface Damage Detection Method Based on YOLOv8. The proposed framework incorporates three key innovations: First, a C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module is designed to dynamically adjust feature weights, enabling the model to more effectively focus on the geometric structural details of irregular defects. Secondly, a Multi-Scale Edge Perception Enhancement (MEPE) module is introduced to extract edge textures directly within the network. This approach prevents the decoupling of edge features from global context information, effectively resolving the issue of edge information loss and enhancing the recognition of small targets. Finally, the detection head is optimized using a Re-parameterized Shared Convolution Detection Head (RSCD) strategy. By employing weight sharing combined with Diverse Branch Blocks (DBB), this design significantly reduces computational redundancy while maintaining high localization accuracy. Experimental results demonstrate that DMR-YOLO outperforms the baseline YOLOv8n, achieving a 1.8% increase in mAP@0.5 to 82.2%, with a notable 3.2% improvement in the “damage” category. Furthermore, the computational load is reduced by 9.9% to 7.3 GFLOPs, while maintaining an inference speed of 92.6 FPS, providing an effective solution for real-time wind farm defect detection.

1. Introduction

The global transition towards renewable energy resources is a pivotal strategy for mitigating climate change and enhancing energy security [1]. As a critical component of energy harvesting, the structural integrity and service performance of WTBs directly dictate the power generation efficiency and operational stability of the entire system [2]. Throughout their lifecycle, WTBs must withstand complex environmental stresses, including saline corrosion, extreme temperature fluctuations, and high-impact loads, which inevitably lead to progressive surface degradations such as cracks, erosion, and delamination [3,4]. If left undetected, minor surface damage can propagate into catastrophic structural failures, incurring prohibitive maintenance costs and significant safety hazards [5]. Consequently, implementing regular and precise WTB defect detection is of vital significance to the sustainable growth of the wind power industry [6].

Traditionally, WTB inspection primarily relied on manual visual assessment or contact-based sensors, such as vibration [7], acoustic emission [8], and ultrasonic sensors [9]. However, these methods are often constrained by environmental sensitivity and operational complexity. To enable autonomous diagnosis, deploying deep learning algorithms directly on UAV onboard edge devices has become a standard paradigm [10,11]. Visual inspection methodologies primarily categorize into instance segmentation and object detection. While segmentation approaches like Mask R-CNN [12] theoretically offer pixel-level precision, their complex decoder architectures and pixel-wise processing impose prohibitive memory and latency burdens on resource-constrained UAV chips. In contrast, real-time object detection strikes an optimal balance between diagnostic accuracy and computational efficiency. By localizing defects via bounding boxes rather than dense masks, this lightweight paradigm aligns far better with the strict operational constraints of industrial UAV inspection.

However, while object detection offers a viable deployment solution, its efficacy is severely compromised by the unique characteristics of WTB imagery [13]. A primary bottleneck in current autonomous detection frameworks arises from the intrinsic geometric mismatch between standard convolutional kernels and the diverse morphologies of WTB defects. Unlike generic objects with rigid structures, structural damage on WTBs exhibits extreme randomness in shape and topology. These defects range from slender cracks to, more commonly, irregular peeling and diffuse erosion patches. Such non-rigid targets possess arbitrary boundaries that defy the fixed grid geometry of standard bounding boxes. Standard detectors employ rigid receptive fields that lack the spatial flexibility to conform to these unpredictable variations, leading to feature misalignment where the detection box fails to tightly wrap around the irregular defect contours.

Compounding this geometric challenge is the indistinguishability of boundary cues. In complex aerial scenarios, the visual texture of WTB surface damage—such as rust spots or coating detachment—often shares high similarity with environmental noise or surface accumulation such as dirt. During the feature extraction process of deep networks, the subtle gradients defining the edges of these defects are easily submerged by the dominant semantic features of the background. This “texture confusion” causes the detector to lose track of the precise defect extent, resulting in coarse localization and a high rate of false negatives for targets with blurred or low-contrast margins.

To address these multifaceted challenges, we propose DMR-YOLO, a sophisticated and efficient framework specifically optimized for WTB surface damage detection. Our approach systematically tackles the aforementioned problems through the following innovations:

- We formulate a geometry-aware feature alignment mechanism to resolve the geometric mismatch inherent in standard convolutions. Specifically, our proposed C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module utilizes Multi-path Coordinate Attention to actively predict spatial offsets for Deformable Convolutions. This allows the receptive field to dynamically deform and align with the topological variations of arbitrary peeling and erosion patches, ensuring precise feature extraction for non-rigid targets.

- We introduce an explicit edge-guided reconstruction strategy to overcome boundary degradation caused by texture confusion. Through the MEPE module, we establish a dedicated processing branch that extracts high-frequency cues and re-injects them into the semantic flow. This explicitly compensates for the edge information lost during downsampling, preventing the localization drift often seen in blurred defects.

- We develop a decoupled training-inference strategy to harmonize detection accuracy with deployment efficiency. The RSCD head employs diverse branch topologies during training to capture rich features, which are then mathematically collapsed into a streamlined single-path structure for inference. This achieves the representational power of a complex model with the real-time speed required for UAV edge computing.

2. Related Work

Classic object detection algorithms are generally categorized into two-stage and one-stage paradigms. Two-stage models, such as Faster R-CNN [14] and Cascade R-CNN [15], prioritize accuracy by extracting candidate regions before classification. Conversely, one-stage models like SSD [16] and the YOLO series [17] directly predict bounding boxes and class probabilities in a single forward pass. Recently, Transformer-based models like REDef-DETR [18] and improved RT-DETR [19] have shown remarkable potential in industrial defect detection. However, their substantial computational overhead often limits deployment on resource-constrained edge devices. In contrast, CNN-based detectors, particularly YOLO, offer a superior balance between speed and accuracy. Consequently, one-stage methods remain the preferred choice for real-time aerial inspection scenarios.

However, applying these standard detectors to WTBs reveals significant challenges, primarily regarding the representation of non-rigid object features. Standard CNNs, with their fixed rectangular kernels, struggle to represent the irregular geometries of blade cracks. To address this, Zou et al. [20] developed DCW-YOLO, integrating Dynamic Separable Convolution (DSConv) to capture the geometric structural details of irregular and elongated defects. Similarly, for ultrasonic testing, Wu et al. [19] proposed UCD-YOLO, which combines deformable convolutional networks and context enhancement to extract features of complex damage forms like stratification. Beyond pure CNN architectures, Yuan et al. [21] explored the Transformer-based RT-DETR framework, proposing a Hierarchical Scale Feature Pyramid Network (HS-FPN) to robustly adapt to defects with varying topographies, such as scratches and pitting.

In addition to geometric deformation, precise localization is often hindered by weak boundary signals. Since boundaries represent high-frequency components, Dong et al. [22] proposed HEFPNet with an edge feature enhancement fusion module. To further strengthen the extraction of small targets, Hang et al. [23] introduced MIP-YOLO, incorporating Haar wavelet attention (HWA) to explicitly extract object edge features. Addressing the separation of tiny defects from complex backgrounds, Ma et al. [24] developed SPDP-Net, which utilizes semantic prior mining to capture fine-grained pixel-level location priors. Furthermore, to tackle image blurring caused by the non-planar curvature of blades, Ye et al. [25] introduced a multi-scale morphological enhancement algorithm based on top-hat operations to sharpen edge features under uneven illumination.

Finally, structural reparameterization has emerged as a pivotal strategy for balancing detection accuracy and inference efficiency on edge devices. For instance, Yao et al. [26] optimized a YOLOX-based model by integrating RepVGG blocks and cascaded feature fusion. Similarly, Zhang et al. [27] introduced the Rep-GFPN in CGIW-YOLOv8 to facilitate efficient cross-scale feature fusion. In the context of large-kernel designs, Zou et al. [28] proposed AUD-YOLO, which integrates UniRepLKNet. By utilizing structural re-parameterization to combine non-dilated large kernels with dilated small kernels, this architecture decouples the receptive field from model depth, capturing comprehensive image details without the computational cost of deep stacking.

Despite these significant advancements, current frameworks still face limitations when deployed in complex field environments. Most existing approaches address specific challenges—such as geometric deformation, edge blurring, or inference speed—in isolation. They typically lack a unified mechanism to simultaneously tackle the intrinsic geometric mismatch of non-rigid defects and the boundary degradation of weak targets while maintaining the strict efficiency required for UAV onboard computing. Consequently, missed detections of minute cracks and false positives in low-contrast regions remain prevalent issues that necessitate a more holistic architectural design.

3. Methods

3.1. Overall Architecture of DMR-YOLO

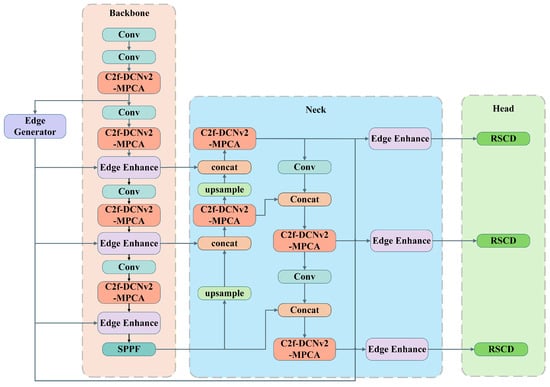

The architecture of the proposed DMR-YOLO is illustrated in Figure 1. The C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module is utilized to globally replace the standard C2f units to construct a dynamic feature extraction framework, which actively aligns the receptive field with irregular defect morphologies so as to deal with the problem of geometric mismatch in non-rigid damage detection. Simultaneously, a parallel Edge Generator stream is introduced to inject explicit gradient priors via hierarchical Edge Enhancement (EE) modules, addressing the issue of boundary degradation and feature loss in low-contrast UAV images. In addition, the RSCD head is designed to decouple training complexity from inference latency; this mechanism optimizes the boundary box regression in the prediction part, thereby ensuring real-time performance on resource-constrained UAV platforms without compromising detection accuracy.

Figure 1.

Architecture of DMR-YOLO: integrating dynamic feature alignment, multi-scale edge guidance, and re-parameterized shared detection.

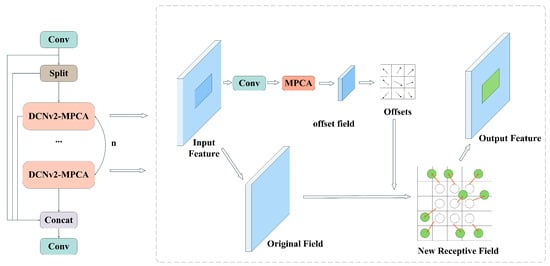

3.2. C2f-DCNv2-MPCA

The intrinsic challenge in detecting wind turbine blade defects lies in the geometric mismatch between the fixed grid geometry of standard convolutions and the non-rigid morphological variations of defects. While DCNv2 [29] introduces deformable sampling, its effectiveness hinges on the quality of the learned offsets. To ensure the network focuses on salient defect regions amidst complex backgrounds, we propose the C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module, integrating a Multi-path Coordinate Attention (MPCA) mechanism as an active geometric navigator, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The structure diagram of C2f-DCNv2-MPCA.

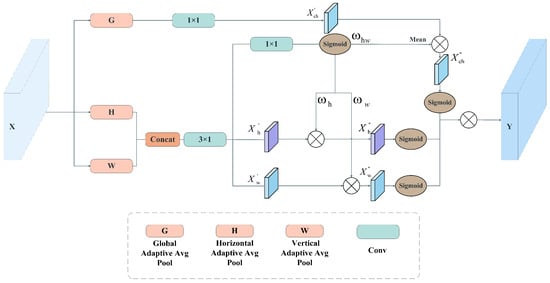

The MPCA is engineered to capture holistic context through a synergistic tri-path architecture. Distinct from standard Coordinate Attention, which relies solely on spatial encoding, MPCA introduces a global channel interaction stream to complement direction-aware features. As illustrated in Figure 3, the mechanism begins by decomposing the input tensor X into orthogonal feature descriptors via pooling operations. A global adaptive average pooling (G) compresses the input into a channel descriptor (capturing global semantics), while horizontal (H) and vertical (W) pooling kernels generate direction-aware vectors and (capturing spatial location):

Figure 3.

The structure diagram of MPCA.

To facilitate cross-directional interaction, the spatial descriptors and are concatenated and fused via a convolution. Simultaneously, the channel descriptor is projected via a convolution. These operations yield the refined intermediate features:

Subsequently, a shared attention map is generated from the spatial features through a convolution followed by a Sigmoid function. This map is then used to modulate all three branches. Specifically, is split into and for spatial paths, while its global mean is computed to modulate the channel path. The re-calibrated intermediate features are formulated as:

Finally, the output feature map Y is generated by synergistically applying these re-calibrated signals to the original input. Each branch undergoes a Sigmoid activation to form a specialized attention gate, which is element-wise multiplied with the input X:

Crucially, this attention-modulated map Y is fed directly into the offset regression layer of the DCNv2. By utilizing the explicitly modeled spatial priors from Equation (4), the network predicts precise sampling offsets, allowing the receptive field to dynamically deform and tightly wrap around the irregular boundaries of non-rigid defects.

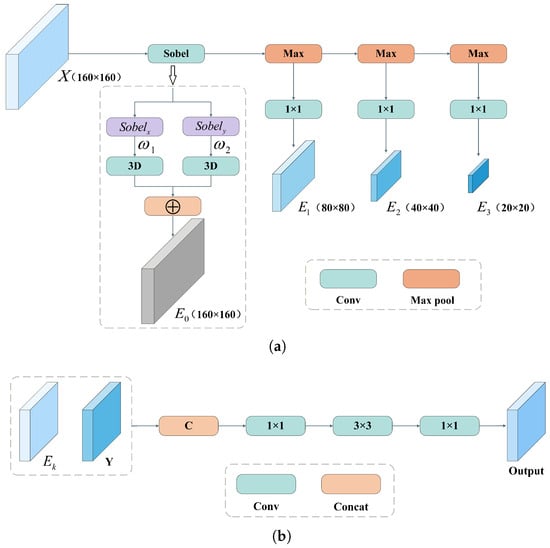

3.3. Multi-Scale Edge Perception Enhancement

In aerial imagery of WTBs, the visual boundaries of defects are often submerged by surface texture noise such as oil stains or dirt, leading to boundary degradation and texture confusion. Conventional detection paradigms often address this by employing edge operators in a decoupled preprocessing step. However, this approach introduces computational overhead and severs the connection between edge cues and deep semantic features. To address this, we propose the MEPE module, an end-to-end integrated architecture designed for explicit edge-guided reconstruction. As depicted in Figure 4, the MEPE module orchestrates a dual-stage process comprising a Multi-scale Edge Generator (MEG) and an Edge Enhancement (EE) unit.

Figure 4.

The structure diagram of Multi-scale Edge Perception Enhancement: (a) multi-scale edge generator; (b) edge enhancement unit.

The MEG (Figure 4a) is strategically positioned at the initial stage to construct a pyramid of edge representations. Unlike standard learnable convolutions, the process commences with a specialized gradient extraction layer utilizing non-learnable 3D kernels initialized with fixed weights () derived from horizontal and vertical Sobel operators. This explicitly captures gradient magnitude maps from low-level features. To preserve boundary details across scales while filtering minor texture noise, undergoes hierarchical max-pooling and convolution refinement:

This hierarchical downsampling ensures that high-frequency edge information is captured from fine to coarse granularities, maintaining sensitivity to boundary cues even at larger receptive fields.

Subsequently, the EE unit (Figure 4b) injects these reconstructed edge features back into the main semantic stream. The process is not merely concatenation but an explicit semantic alignment. It is important to note that these Sobel operators serve only as a weak inductive prior to guide the network’s attention to high-frequency regions; the subsequent learnable convolutions are responsible for adaptively fusing these cues with semantic features. The multi-scale edge maps are first concatenated and fused via a convolution to compress channel dimensionality. A subsequent convolution models the local spatial context, further refining the boundary definitions before projecting them into the backbone feature space. This explicit injection of gradient information acts as a boundary correction signal, sharpening the blurred edges of deep semantic features and significantly improving localization accuracy for low-contrast defects.

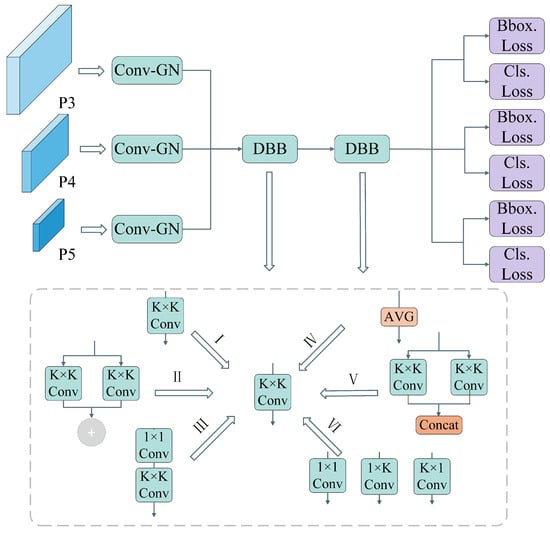

3.4. Re-Parameterized Shared Convolutional Detection Head

To reconcile the conflict between the need for high-capacity feature representation and the strict latency constraints of UAV onboard inference, we propose the RSCD head. As illustrated in Figure 5, this module transforms the detection paradigm by integrating a cross-scale parameter-sharing mechanism with a decoupled training-inference strategy based on structural re-parameterization.

Figure 5.

The structure diagram of RSCD.

The architecture commences by processing the multi-scale feature maps from the pyramid levels (). Unlike standard heads that employ independent parameters for each scale, RSCD first unifies these inputs through a Conv-GN [30] layer. This combines convolution with Group Normalization to standardize feature distributions across scales while minimizing computational overhead. These unified features are then fed into a shared feature transformation backbone composed of a cascade of two DBB [31].

This DBB-based backbone employs a structural re-parameterization strategy to decouple training complexity from inference speed. During the training phase, as depicted in the bottom panel of Figure 5, each DBB enhances representation diversity by aggregating multiple heterogeneous branches—including convolutions, convolutions, sequential convolutions, and average pooling paths. This over-parameterized topology creates a vast hypothesis space, capturing subtle feature nuances required for small target detection.

Crucially, for the inference phase, the DBB mathematically collapse these complex parallel branches into a single stream. Exploiting the linearity of convolution, the diverse kernels and biases from the training topology (I–VI) are merged into a single equivalent convolution kernel and bias.

This transformation ensures that the deployment model executes with the high throughput of a simple single-path network while retaining the powerful representational capacity learned during training. Finally, the processed features are bifurcated into lightweight task-specific heads to compute bounding box regression and classification losses, completing the efficient detection pipeline.

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Dataset

The experimental evaluation utilizes the UAV-based wind turbine inspection dataset constructed by Shihavuddin [32]. This dataset comprises 2995 high-resolution images ( pixels) capturing critical components such as blades, rotors, and towers. To ensure robust generalization, the dataset was partitioned into training, validation, and testing sets in an 8:1:1 ratio.

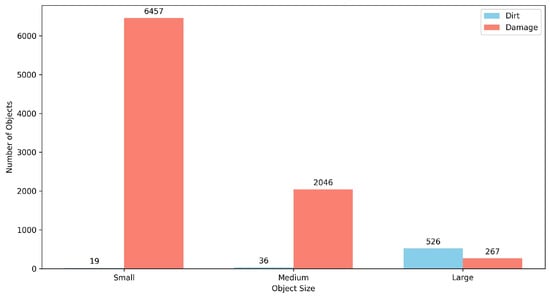

The annotated defects are categorized into “dirt” (581 instances) and “damage” (8770 instances). As illustrated in Figure 6, the defects exhibit diverse morphologies. Figure 7 highlights the significant class imbalance: the “dirt” category predominantly consists of large-scale targets, whereas the “damage” category—comprising 6547 instances—is characterized by small-scale, irregular features such as cracks and surface peeling. Enhancing detection accuracy for these small-scale “damage” targets is the primary objective of this study.

Figure 6.

Representative defect samples from the dataset.

Figure 7.

Distribution of target sizes for dirt and damage categories.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively assess the performance of the proposed model, we employ standard metrics, including Precision (P), Recall (R), Average Precision (), and Mean Average Precision ().Precision measures the accuracy of positive predictions, while Recall quantifies the ability to identify all positive instances. They are defined as:

where , , and represent True Positives, False Positives, and False Negatives, respectively. Average Precision (AP) is calculated as the area under the Precision-Recall (P-R) curve for a single class:

Mean Average Precision (mAP) represents the mean of AP values across all classes. Specifically, mAP@0.5 denotes the mAP calculated at an IoU threshold of 0.5, mAP@0.95 indicates the mAP calculated at an IoU threshold of 0.95:

where (dirt and damage). To evaluate the feasibility of deployment on resource-constrained UAVs, we utilize Parameters (M) and GFLOPs to assess spatial complexity and computational cost. Furthermore, Frames Per Second (FPS) is adopted to quantify the actual inference speed, encompassing pre-processing, inference, and Non-Maximum Suppression (NMS) time. It is defined as:

where represents the time consumption (in milliseconds) for model inference per image, respectively. This metric is critical for verifying whether the algorithm meets the strict real-time requirements of aerial inspection tasks.

4.3. Experiment Environment and Settings

All experiments were implemented using the PyTorch (version 1.12.1) deep learning framework on a high-performance computing server equipped with an Intel(R) Core(TM) i5-12400F CPU and an NVIDIA GeForce RTX 3090 GPU. The specific hyperparameters, detailed in Table 1, were selected via a manual tuning process guided by the model’s performance on the validation set. To ensure fair comparisons, these optimized settings were consistently applied across all experimental models.

Table 1.

Detailed experimental hyperparameter configuration.

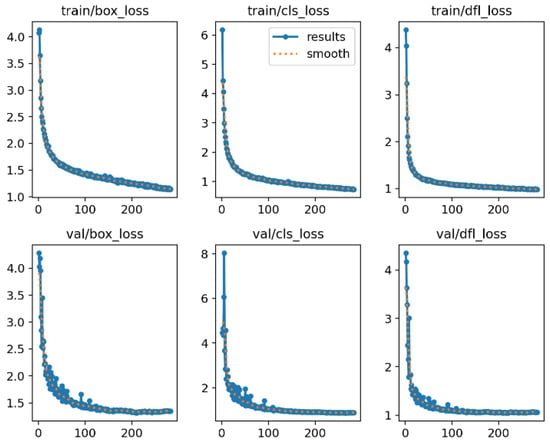

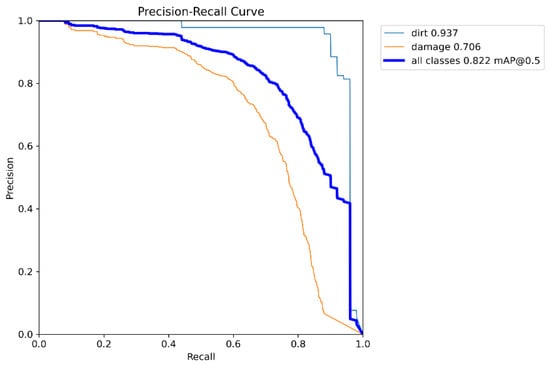

4.4. Analysis of Training Results Graph

As shown in Figure 8, the box regression, classification, and DFL losses exhibit a consistent downward trend on both training and validation sets, indicating that the model effectively learned feature representations without overfitting. Figure 9 presents the P-R curve. The model achieves an AP of 93.7% for “dirt” and 70.6% for “damage,” resulting in an overall mAP@0.5 of 82.2%. Despite the irregular nature of damage defects, the high AP score confirms the model’s robustness.

Figure 8.

Training and validation loss curves.

Figure 9.

Precision-Recall (P-R) curve.

4.5. Ablation Experiments

To quantify the individual contribution of each proposed module, a stepwise ablation study was conducted using YOLOv8n as the baseline. The quantitative results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Ablation experiment. The “✔” indicates that the specific module is included in the model configuration.

The baseline model (Exp. 1) achieved an mAP@0.5 of 80.4% but exhibited limited performance on the “damage” category (67.4% AP) due to the non-rigid nature of the defects. The integration of the C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module (Exp. 2) improved the overall mAP@0.5 by 1.0%. More importantly, it specifically boosted the accuracy for the irregular “damage” category from 67.4% to 69.2% (+1.8%), validating that the active geometric alignment mechanism effectively captures complex morphological variations. Subsequently, the MEPE module (Exp. 3) further raised the overall performance to 82.0% and the to 70.7%, proving that explicit gradient priors enhance the definition of low-contrast boundaries. Finally, the RSCD head (Exp. 4) optimized the inference architecture. Through structural re-parameterization, this design reduced the parameter count by 18.4% and GFLOPs by 18.0% (from 8.9 to 7.3) compared to Exp. 3, while maintaining the peak accuracy of 82.2%. Notably, the stricter metric mAP@0.5:0.95 exhibited a substantial improvement of 4.4% (from 52.5% to 56.9%), indicating that the proposed modules significantly enhance bounding box tightness and localization precision for irregular defects. The final model achieves a 1.8% mAP gain over the baseline with reduced computational cost, demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed add-on modules.

4.6. Internal Analysis of Core Mechanisms

This section provides a deeper analysis of the internal mechanism design, specifically evaluating the effectiveness of the attention guidance and the edge fusion strategy.

4.6.1. Evaluation of Attention Mechanisms

We benchmarked the proposed MPCA against mainstream mechanisms, including Coordinate Attention (CA) [33], SimAM [34], DDSM [35], and EMA [36]. As shown in Table 3, while mechanisms like CA and EMA improve overall performance compared to the standard DCNv2, they plateau around 68% AP for the challenging “damage” category. In contrast, our MPCA achieves the highest mAP@0.5 (82.2%) and specifically outperforms the second-best EMA by a significant margin of 2.6% in the “damage” category. This superiority stems from the proposed tri-path synergistic architecture. Standard CA relies solely on two spatial paths () to encode position, which often struggles to distinguish subtle defects from textured background noise. Our MPCA introduces an extra global channel path () to complement spatial encoding. This allows the network to simultaneously leverage spatial priors to trace the irregular defect topology and global semantic context to suppress environmental interference, making it significantly more robust for WTB inspection tasks.

Table 3.

Comparison of different attention mechanisms combined with DCNv2.

4.6.2. Analysis of Edge Fusion and Head Designs

We further validated the architectural decisions for the MEPE module and the RSCD head. The results are presented in Table 4. Regarding edge fusion, the results indicate that integrating the edge module solely with the backbone (MEPE-1) or the neck (MEPE-2) suffers from insufficient feature propagation. In contrast, our multi-location strategy achieves 82.2% mAP@0.5, confirming that preserving edge consistency across multiple scales is critical. Regarding the detection head, the proposed DBB-based RSCD head surpasses the standard RepConv-based head [37] by 4.0% in mAP. This demonstrates that the diverse branch topology used during training effectively expands the hypothesis space.

Table 4.

Comparative results of edge fusion strategies and detection heads.

4.7. Comparative Experiments

To verify the superiority of DMR-YOLO, we compared it with representative detectors including Faster R-CNN [14], SSD [16], RT-DETR [38], and the full YOLO series ranging from YOLOv5 to the latest YOLOv13. The comprehensive accuracy results are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Comprehensive performance comparison with state-of-the-art methods.

As indicated in Table 5, DMR-YOLO achieves the highest detection precision of 82.2% mAP@0.5. Compared to the baseline YOLOv8n, our model improves the overall mAP by 1.8%. More importantly, it outperforms the most recent state-of-the-art models, including YOLOv12n and YOLOv13n, by 0.7%. Specifically, in the challenging “damage” category, DMR-YOLO surpasses YOLOv13n by 1.9% and YOLOv12n by 1.1%. This result highlights that while newer generic YOLO iterations focus on architectural optimization for general objects, our specialized design—combining geometric alignment, edge enhancement, and re-parameterization—is more effective for handling the irregular and non-rigid defects specific to WTBs.

4.8. Inference Efficiency and Deployment Analysis

In addition to detection accuracy, inference speed is a critical metric for UAV-based inspection tasks. Table 6 reports the real-world inference speed measured on an NVIDIA RTX 3090 GPU.

Table 6.

Inference speed comparison.

While introducing additional geometric alignment and edge enhancement modules typically increases latency, the structural re-parameterization strategy in our RSCD head effectively mitigates this impact. Our model achieves an inference speed of 92.6 FPS. Although slightly lower than the newest YOLOv13n due to the heavy coordinate attention computations and edge fusion, it satisfies the real-time requirement for aerial UAV inspection. Considering the superior detection accuracy (YOLOv13n), DMR-YOLO offers a balanced trade-off between precision and deployment efficiency for this specific industrial application.

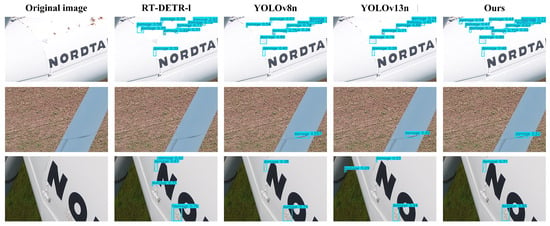

4.9. Qualitative Analysis

To intuitively demonstrate the superiority of DMR-YOLO, we visualize the detection results and use Grad-CAM heatmaps to interpret the model’s decision-making process.

4.9.1. Visual Comparison of Detection Results

Figure 10 compares the detection performance across varying environmental conditions, highlighting the robustness of our method.

Figure 10.

Visual comparison of detection results.

In scenarios characterized by strong illumination, the high reflectivity of the blade surface typically washes out textural details and reduces pixel intensity contrast. This poses a significant challenge for generic models like YOLOv8n and YOLOv13n, which rely heavily on local intensity patterns, leading to missed detections of minute peeling spots. In contrast, DMR-YOLO maintains high sensitivity under these high-exposure conditions. This robustness is fundamentally attributed to the C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module. By prioritizing active geometric alignment over simple intensity matching, the module enables the network to capture the underlying morphological structure of defects even when surface textures are degraded by glare.

When detecting defects against complex backgrounds—ranging from textured soil to highly cluttered environments with vegetation and text logos—generic detectors often struggle with both boundary definition and semantic distractions. As observed in the visual results, RT-DETR-l suffers from severe false positives by confusing text characters with defects, while standard YOLO variants produce loose bounding boxes due to background noise. DMR-YOLO, conversely, demonstrates superior discrimination capability and localization precision. It robustly filters out semantic interferences and focuses exclusively on actual damage. This confirms the efficacy of the MEE module. By explicitly injecting gradient priors, MEE enhances the discriminative power of defect boundaries, allowing the model to effectively decouple the target signal from background clutter and establish precise detection boundaries.

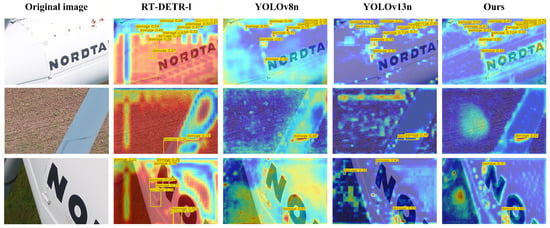

4.9.2. Interpretation of Model Focus via Heatmaps

To further elucidate the underlying mechanism of the detection improvements, we employed Grad-CAM to visualize the attention distribution of the backbone network (Figure 11).

Figure 11.

Grad-CAM visualization comparison among different models. Red regions indicate high model attention, while blue regions indicate low attention.

The heatmaps reveal that the performance degradation in comparison models stems from distinct attention failures. RT-DETR-l exhibits severe attention misalignment, where activation is predominantly concentrated on irrelevant semantic features, such as text logos and grass textures, rather than on the defects. This confirms that without domain-specific constraints, the global attention mechanism tends to overfit background noise. Conversely, YOLOv13n and YOLOv8n display scattered and weak activation intensities (indicated by faint blue regions), which correlate with their inability to effectively resolve low-contrast boundaries under complex environments.

Unlike these behaviors, DMR-YOLO exhibits sharper attention to defect boundaries and irregular areas. This visual improvement implicitly verifies the effectiveness of our core components: the C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module guides the network to cover non-rigid regions, thereby successfully ensuring that the network’s attention strictly conforms to the geometric irregularities of the target. And the MEPE module enhances the signal-to-noise ratio of defect edges, effectively filtering out texture interference, thus suppressing background noise and highlighting edge details, achieving precise localization in the heatmap.

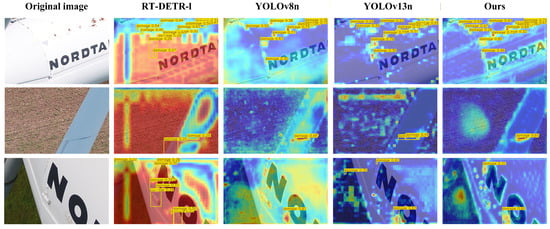

4.9.3. Validation of MPCA Against Other Attention Mechanisms

Finally, to specifically validate the design rationale of the C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module, Figure 12 compares the activation patterns of different attention mechanisms trained within the same framework.

Figure 12.

Visualization of different attention mechanisms combined with DCNv2. Red regions indicate high model attention, while blue regions indicate low attention.

Standard modules such as SimAM and DDSM exhibit fragmented activation maps, often focusing on salient local points while failing to cover the entire extent of slender defects. Although EMA shows improved focus, it still struggles to define clear boundaries, resulting in feature spillover into the background. In comparison, the proposed MPCA demonstrates a unique capability to trace the continuous morphological structure of cracks while maintaining a clean background. This visual coherence is a direct result of its tri-path synergistic architecture: the spatial paths () enable the network to strictly follow the irregular defect topology, while the global channel path (C) enhances semantic discrimination to prevent feature spillover. This confirms that the combined encoding of spatial coordinates and global context is indispensable for guiding the deformable receptive field to fit wind turbine blade defects.

5. Discussion

While DMR-YOLO demonstrates state-of-the-art performance, a deeper analysis of failure cases reveals insights into the model’s limitations under extreme conditions (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Visualization of failure cases: (a) the red box highlights a missed defect caused by gradient loss in extreme low light; (b) the red arrow points to a false positive caused by cloud texture confusion in overcast weather.

Figure 13a illustrates a missed detection in severe low-light scenarios. Here, insufficient illumination compresses the dynamic range, causing defect features to blend indistinguishably with the background. Consequently, the MEPE module fails to activate due to the effective elimination of gradient signals. Conversely, Figure 13b shows a false positive under overcast conditions. The complex cloud texture shares high-frequency characteristics with surface peeling, leading the model to misinterpret the background as a defect. This highlights a limitation in the training set, which lacks explicit negative samples for semantic categories like “sky”.

These failure modes underscore the critical dependency on dataset diversity. Compared to general datasets like COCO, the public benchmark used here contains a scarcity of samples under extreme meteorological conditions, limiting generalization in rare atmospheric scenarios. To address this, future work will focus on two key areas: expanding data collection across diverse weather conditions (e.g., fog, dusk) to capture environmental variability, and employing semi-supervised learning or synthetic data generation to enhance robustness against long-tail anomalies, thereby bridging the gap between academic research and industrial deployment.

6. Conclusions

This study addresses the critical challenge of balancing detection accuracy and computational efficiency in WTBs inspection by proposing the DMR-YOLO framework. To overcome the limitations of standard convolutions in handling irregular cracks and minute surface defects, the proposed model introduces three synergistic architectural innovations.

First, the integration of the C2f-DCNv2-MPCA module endows the network with superior geometric adaptability. By utilizing Multi-path Coordinate Attention to guide deformable convolutions, it achieves precise feature alignment for non-rigid defect shapes. Second, the MEPE module explicitly embeds gradient priors into the feature extraction process, effectively reconstructing high-frequency boundary cues that are typically attenuated in low-contrast UAV imagery. Third, the RSCD head resolves the efficiency bottleneck. It mitigates computational redundancy through structural re-parameterization, decoupling the multi-branch training topology from the efficient single-stream inference structure.

Comprehensive experimental evaluations confirm the robustness of the proposed method. DMR-YOLO achieves an mAP of 82.2%, outperforming the baseline YOLOv8n by 1.8% while reducing the computational load (GFLOPs) by 9.9%. Most notably, the detection accuracy for the challenging “damage” category improved by a substantial 3.2%, validating the model’s efficacy in identifying subtle and irregular defects in complex wind farm environments. Furthermore, with an inference speed of 92.6 FPS, the proposed model fully satisfies the real-time processing requirements for UAV-based aerial inspections.

Author Contributions

L.S. contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, and validation. S.W. contributed to conceptualization, software, validation, data curation, methodology, original draft writing, and review and editing. J.Z. was responsible for project administration, supervision, and resources. Z.K. and L.W. contributed to methodology and resources. L.M. and H.Y. were responsible for visualization. H.W. contributed to conceptualization and formal analysis. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Part of this research was supported by the Jilin Provincial Science and Technology Development Plan Project (Project No.: 20260203050SF) and the development of the space laser communication target detection and trajectory prediction system.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset used for this study is publicly available and accessible online from DOI: https://doi.org/10.17632/hd96prn3nc.2.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Z.; Bu, L.; Han, S. AI-enabled and multimodal data driven smart health monitoring of wind power systems: A case study. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2023, 56, 102018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; He, Y.; Gu, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, R.; Chady, T.; Zhou, B. UAV based defect detection and fault diagnosis for static and rotating wind turbine blade: A review. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 40, 1691–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, W.; Park, H. Structural Design and Safety Analysis for Optimized Segmentation of Wind Turbine Blades with Composite Materials. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 11445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martini, F.; Ibrahim, H.; Contreras Montoya, L.; Rizk, P.; Ilinca, A. Turbulence modeling of iced wind turbine airfoils. Energies 2022, 15, 8325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.S.; Yan, J.; Hu, W.; Jiang, Z.; Shi, W.; Teuwen, J.J. A review of impact loads on composite wind turbine blades: Impact threats and classification. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2023, 178, 113261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Heath, W.P. Wavelet package energy transmissibility function and its application to wind turbine blade fault detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 13597–13606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashkarkalaei, M.; Ghiasi, R.; Pakrashi, V.; Malekjafarian, A. Feature selection for unsupervised defect detection of a wind turbine blade considering operational and environmental conditions. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2025, 230, 112568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mielke, A.; Benzon, H.H.; McGugan, M.; Chen, X.; Madsen, H.; Branner, K.; Ritschel, T.K. Analysis of damage localization based on acoustic emission data from test of wind turbine blades. Measurement 2024, 231, 114661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Séguin-Charbonneau, L.; Walter, J.; Théroux, L.D.; Scheed, L.; Beausoleil, A.; Masson, B. Automated defect detection for ultrasonic inspection of CFRP aircraft components. NDT E Int. 2021, 122, 102478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Du, W.; Zhu, R.; Li, F. Research and development of wind turbine blade damage detection technology. Proc. CSEE 2022, 43, 4614–4630. [Google Scholar]

- Bošnjaković, M.; Martinović, M.; Đokić, K. Application of artificial intelligence in wind power systems. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Bao, Y. Review on automated condition assessment of pipelines with machine learning. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 53, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster r-cnn: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, Z.; Vasconcelos, N. Cascade r-cnn: Delving into high quality object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6154–6162. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single shot multibox detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; Proceedings, Part I 14. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You only look once: Unified, real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Jiang, C.; Liang, T. REDef-DETR: Real-time and efficient DETR for industrial surface defect detection. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 105411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wu, R.; Wang, H.; Cheng, Z.; To, S. Real-time detection of blade surface defects based on the improved RT-DETR. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Chen, A.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Sun, Y. DCW-YOLO: An improved method for surface damage detection of wind turbine blades. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Jia, B.; Huang, B.; Seah, W.K. Wind Turbine Blade Surface Defect Detection Based on FFDA-YOLO. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing, Ningbo, China, 26–29 July 2025; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2025; pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, X.; Wang, J.; Dong, B. alient object detection in optical remote sensing images based on hybrid edge fusion perception. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 165, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, X.; Zhu, X.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L. Study on crack monitoring method of wind turbine blade based on AI model: Integration of classification, detection, segmentation and fault level evaluation. Renew. Energy 2024, 224, 120152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. SPDP-Net: A semantic prior guided defect perception network for automated aero-engine blades surface visual inspection. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2024, 22, 2724–2733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, L.; Huang, C.; Luo, X. Wind turbine blade defect detection with a semi-supervised deep learning framework. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 136, 108908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Wang, G.; Fan, J. WT-YOLOX: An efficient detection algorithm for wind turbine blade damage based on YOLOX. Energies 2023, 16, 3776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Fang, Y.; Gao, W.; Liu, X.; Yang, H.; Tong, Y.; Wang, M. Attention mechanism based on deep learning for defect detection of wind turbine blade via multi-scale features. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2024, 35, 105408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, L.; Chen, A.; Yang, X.; Sun, Y. An improved method of AUD-YOLO for surface damage detection of wind turbine blades. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Hu, H.; Lin, S.; Dai, J. Deformable convnets v2: More deformable, better results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 9308–9316. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; Shen, C.; Chen, H.; He, T. Fcos: Fully convolutional one-stage object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9627–9636. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Zhang, X.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Diverse branch block: Building a convolution as an inception-like unit. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 10886–10895. [Google Scholar]

- Shihavuddin, A.; Chen, X.; Fedorov, V.; Nymark Christensen, A.; Andre Brogaard Riis, N.; Branner, K.; Bjorholm Dahl, A.; Reinhold Paulsen, R. Wind turbine surface damage detection by deep learning aided drone inspection analysis. Energies 2019, 12, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, D.; Feng, J. Coordinate attention for efficient mobile network design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13713–13722. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Zhang, R.Y.; Li, L.; Xie, X. Simam: A simple, parameter-free attention module for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Virtual, 18–24 July; PMLR: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2021; pp. 11863–11874. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Ren, W.; Cao, X.; Knoll, A. Focal network for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023; pp. 13001–13011. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, D.; He, S.; Zhang, G.; Luo, M.; Guo, H.; Zhan, J.; Huang, Z. Efficient multi-scale attention module with cross-spatial learning. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2023–2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes Island, Greece, 4–9 June 2023; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Soudy, M.; Afify, Y.; Badr, N. RepConv: A novel architecture for image scene classification on Intel scenes dataset. Int. J. Intell. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 22, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, J.; Du, S.; Ying, S.; Yong, J.H.; Li, Y.; Ding, G.; Ji, R.; Gao, Y. Hyper-yolo: When visual object detection meets hypergraph computation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 47, 2388–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.