Abstract

The cutterhead torque of a full-face tunnel boring machine (TBM) is a pivotal parameter that characterises the rock-machine interaction. Its dynamic prediction is of considerable significance to achieve intelligent regulation of the boring parameters and enhance the construction efficiency and safety. In order to achieve high-precision time series prediction of cutterhead torque under complex geological conditions, this study proposes an intelligent prediction method (VBGAP) that integrates signal decomposition mechanism and physical constraints. At the data preprocessing level, a multi-step data cleaning process is designed. This process comprises the following steps: the processing of invalid values, the detection of outliers, and normalisation. The non-smooth torque time-series signal is decomposed by variational mode decomposition (VMD) into narrow-band sub-signals that serve as a data-driven, frequency-specific input for subsequent modelling, and a hybrid deep learning model based on Bi-GRU and self-attention mechanism is built for each sub-signal. Finally, the prediction results of each component are linearly superimposed to achieve signal reconstruction. Concurrently, a novel modal energy conservation loss function is proposed, with the objective of effectively constraining the information entropy decay in the decomposition-reconstruction process. The validity of the proposed method is supported by empirical evidence from a real tunnel project dataset in Northeast China, which demonstrates an average accuracy of over 90% in a multi-step prediction task with a time step of 30 s. This suggests that the proposed method exhibits superior adaptability and prediction accuracy in comparison to existing mainstream deep learning models. The findings of the research provide novel concepts and methodologies for the intelligent regulation of TBM boring parameters.

1. Introduction

In the context of tunnel construction, the Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) is a prevalent choice due to its merits of high efficiency and safety [1]. TBM represents the primary modus operandi in contemporary tunnel construction, amalgamating excavation, grouting, slagging, lining, and surveying with a high degree of automation. It entails intricate machine-rock interaction during the construction process, with cutterhead torque constituting the principal parameter that describes this interaction. Consequently, cutterhead torque is a pivotal index for ascertaining the working condition of the cutter and spindle. Cutterhead torque is defined as the force provided by the cutter drive system when the cutter cuts the soil in the TBM tunnelling process [2]. It has been demonstrated that a reasonable cutterhead torque can effectively reduce the wear of the cutter, improve the TBM tunnelling speed, and simultaneously reduce the disturbance to the surrounding strata [3]. Insufficient torque can result in challenges during excavation, while excessive torque can lead to unwarranted energy expenditure and accelerated equipment degradation. Consequently, the capacity to accurately predict alterations in cutterhead torque in real-time facilitates the anticipation of the TBM’s digging status, thereby providing a crucial foundation for the modification of digging parameters and the optimisation of construction time and financial expenditure.

Currently, the main approaches used to predict TBM cutterhead torque include theoretical modeling, numerical simulation, and artificial intelligence techniques. Among theoretical models, the CSM model developed by the Colorado School of Mines [4] is widely recognized and frequently applied. In addition to the aforementioned classical theoretical models, a significant number of scholars have proposed theoretical analysis methods for calculating cutterhead torque. Lu et al. [5] proposed a torque calculation model for the cutter head that considers the penetration depth of the tool and the earth pressure. By comparing with field data, the rationality of the empirical formula was verified. Zhou et al. [2] established a soil pressure balance shield cutterhead torque estimation model applicable to palm face grinding in composite strata, showing that the cutting torque induced by the disc cutter is particularly important when the proportion of hard rock is large [6]. Yang et al. [7] established a dynamic model of the cutter system by analysing the working process of the motor, coupler, reduction gearbox and gears, and optimised the input torque of the drive motor by using a distributed MPC algorithm. The theoretical analysis method provides a sufficient theoretical basis for the calculation of TBM cutterhead torque. Nevertheless, due to simplified assumptions and ambiguity in parameter selection, the model’s general applicability remains constrained. In the field of numerical analysis, Han et al. [8] developed a methodology for predicting the thrust and torque of the cutter. This was achieved by simulating the cutter-rock interaction through a 3D finite element model. This model takes into account the dynamic effects, material damage and frictional contact. Faramarzi et al. [9] developed a DEM to simulate the interaction of the TBM with excavated materials. This model was able to estimate the cutterhead torque and thrust. It also optimised the performance of the TBM under realistic boundary conditions. Numerical analysis methods have been shown to simulate nonlinear mechanical behaviour and interactions under different stress states with a high degree of accuracy. However, these methods are computationally inefficient, poorly automated and difficult to determine parameters.

The advent of big data and artificial intelligence technologies has precipitated the digitalisation and intelligence of shield tunnel engineering construction [10,11,12]. In the domain of machine learning, Kong et al. [13] utilised the random forest method to predict the torque of a shield cutter. Yin et al. [14] employed a symbolic regression algorithm to analyse the influence of thrust, soil pressure, penetration change and cutter change on cutterhead torque [15]. Xu et al. [16] utilised the LSTM method [17] to predict the tunnel boring rate and torque of a shield tunnel. They then proceeded to analyse the influence of various network parameters on the prediction outcomes. Building upon these findings, Lin et al. [18] further predicted the boring rate and torque of a shield tunnel, employing an LSTM and GRU algorithm. The results demonstrated that the prediction performance of time-sequential deep learning neural networks was superior to that of machine learning methods. Zhang et al. [19] A comparison was made of the prediction performances of LSTM neural networks and random forests. The results demonstrated that LSTM was superior to random forests in terms of accuracy and generalisation ability when predicting the operating parameters of shield tunnels. Qin et al. [20] proposed a convolutional neural network combined with LSTM to predict the operating parameters of shield tunnels. The proposed method has been shown to achieve a higher level of accuracy in predicting cutterhead torque than machine learning methods XGBoost and random forest. Wang et al. [21] used a bidirectional long short-term memory (Bi-LSTM) network to accurately predict the propulsion speed and torque of a mud-water balanced shield machine. Compared to an LSTM network, a Bi-LSTM network can achieve a more accurate prediction of tunnelling parameters with fewer parameters [22,23]. In their respective works, Shi et al. [24] and Qin et al. [25] proposed a shield machine cutterhead torque prediction model combining variational modal decomposition (VMD), empirical wavelet transform (EWT), and LSTM network, and a cutterhead torque prediction model based on adaptive hierarchical decomposition (AHDM), respectively. It should be noted that both of these models are multi-step prediction models. In order to overcome the inability of traditional non-temporal machine learning methods to consider the influence of the temporal characteristics of tunnelling parameters, most of these studies transform the TBM cutterhead torque prediction problem into a time-series prediction problem through the use of deep learning algorithms that sense the temporal characteristics and long-term dependencies of the TBM data with a higher degree of automation and universality [26,27]. However, the prediction scale of these studies is often limited, with the prediction step length being restricted to one or a maximum of ten steps. It is difficult to guarantee the prediction accuracy when the prediction step length increases. Concurrently, the signal decomposition methodologies employed in these studies frequently neglect the consideration of information loss during the signal decomposition-reconstruction process.

A critical analysis of the literature summarized in Table 1 reveals a persistent research gap. While existing decomposition-enhanced deep learning models have proven effective for short-term (e.g., 1–10 step) torque prediction, their focus has primarily been on improving point-wise accuracy. They largely overlook a crucial issue inherent to the “decompose-then-predict” paradigm: information loss during the decomposition-reconstruction process. This manifests as a drift in the energy distribution or spectral characteristics between the original and reconstructed signals over long prediction horizons, fundamentally limiting their reliability for extended multi-step forecasts (e.g., 30 s or more) required for proactive TBM control. Furthermore, the interpretability of the decomposed modes is often assumed but rarely enforced or quantified within the learning objective.

Table 1.

Concise review of data-driven TBM cutterhead torque prediction methods.

This paper therefore addresses the following three key technical challenges: (a) How to achieve high-precision, real-time multi-step prediction of TBM cutterhead torque in the presence of complex, highly non-stationary signals and strongly nonlinear machine-rock interactions. (b) How to design a model framework that effectively integrates signal decomposition and physical constraints, thereby capturing both the multi-scale feature structure and the physical consistency in torque prediction. (c) How to quantify and reduce information loss during the modal decomposition–reconstruction process, ensuring that deep learning models maintain both predictive accuracy and interpretability over extended prediction horizons.

To bridge this gap, this work advances the state of the art in three key aspects. First, we explicitly address the information loss problem by introducing a novel Energy Ratio Loss function. This physics-informed regularizer quantifies and penalizes deviations in the modal energy distribution between predicted and true sub-signals during training. By enforcing energy conservation across modes, it ensures that the long-term temporal structure and physical consistency of the reconstructed torque signal are preserved, which is a novel contribution not present in prior works like [24,25,35]. Second, we move beyond merely assuming decomposition effectiveness by providing a quantitative analysis of modal importance during model fitting. By tracking energy ratio deviations across different VMD modes before and after the decomposition-reconstruction process (see Section 4), we can precisely quantify which frequency bands contribute most to prediction accuracy and which are prone to information loss. This analytical approach provides concrete evidence for the effectiveness of the decomposition. Third, we demonstrate a concrete improvement in the multi-step forecasting framework for tunneling. By integrating VMD, Bi-GRU, and self-attention within this energy-constrained framework, our model achieves superior prediction accuracy for a substantially extended horizon of 30 steps (see Section 4), significantly outperforming existing decomposition-based models that are typically validated on much shorter sequences.

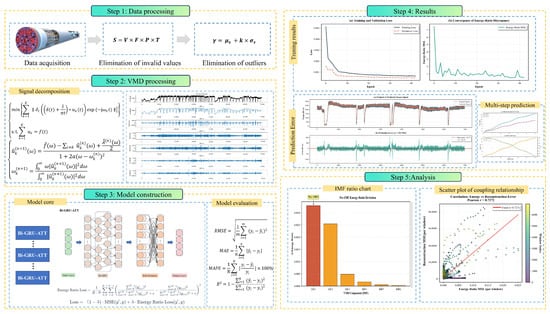

The present study proposes a real-time multi-step prediction method for TBM cutterhead torque that fuses the signal decomposition mechanism with physical constraints. Furthermore, it innovatively proposes an additional loss function based on modal energy conservation. This function effectively constrains the information entropy decay during the decomposition-reconstruction process. The result is enhanced physical interpretability of the model. These enhancements have been demonstrated to improve the prediction accuracy of the model in the real-time cutterhead torque prediction task, thereby effectively extending the credible prediction step size. This, in turn, enables the operator to more effectively monitor the TBM’s operation status and make auxiliary decisions. The flow chart of the overall method is shown in Figure 1. The rest of the paper is organized as follows: Section 2 presents the components and computational principles of TBM cutterhead torque, outlines the step-by-step development of the proposed framework and its underlying algorithms, and explains the criteria and interpretative tools used to assess its performance. Section 3 introduces the project overview and data preprocessing methods of the tunnel project data set used in this study. Section 4 details the model-training procedure and its predictive performance on the dataset, complemented by a SHAP-driven interpretability analysis. Ablation and benchmark studies are further conducted to highlight the architectural strengths of the proposed approach and its edge over prevailing deep-learning algorithms. Section 5 introduces the conclusions drawn, and on this basis, puts forward suggestions for future research.

Figure 1.

The overall flowchart of the method.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Composition of the Cutterhead Torque

It is imperative to comprehend the composition and calculation method of the cutterhead torque prior to undertaking research on the prediction of TBM cutterhead torque. The cutterhead torque of TBM pertains to the combined torque generated by the rolling force of the tool on the rotating shaft of the cutter. This comprises the rolling resistance torque of the cutter, the torque required by the slag mixing, and the torque required by overcoming the cutter’s self-weight. Rolling resistance torque is defined as the rolling resistance torque generated by the rock breaker, which is the primary component of TBM cutterhead torque. The torque required for rock slag mixing is the resistance torque of the rock slag crushed by the cutter rotating with the cutter. The torque required for overcoming cutter weight is the torque required when the cutter is idling. Therefore, the formula for calculating the torque of the TBM cutterhead disc is as follows:

where is the rolling resistance of a single hob, is the distance between the i th hob and the rotating shaft of the cutter head, m is the number of hobs, q is the bulk density of rock slag, is the opening rate of the cutter head, R is the radius of the cutter head, h is the cutting depth per revolution (penetration), is the weight of the cutter head.

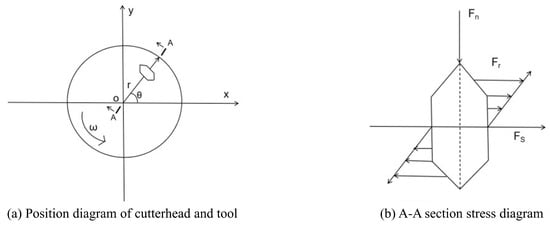

In the process of excavation by TBM, the cutterhead is subjected to normal force, rolling force and lateral force. The torque force model of the cutterhead is illustrated in Figure 2. The radius r, the angle , the rotational speed of the cutterhead , the normal force , the rolling force and the lateral force are all defined in this model.

Figure 2.

Torque force model of cutterhead.

2.2. Variational Mode Decomposition

To address the inherent non-stationarity and complexity of TBM cutterhead torque signals, variational mode decomposition (VMD) is adopted as a preprocessing step in our framework. VMD provides an optimization-based way to adaptively decompose a raw signal into a specified number of modes, each constrained to have a limited bandwidth and distinctive frequency characteristics. Compared to traditional empirical mode decomposition and related techniques, VMD can alleviate mode mixing and endpoint effects to some extent, providing a more stable foundation for downstream modeling [36,37].

In this study, VMD is not considered the central methodological innovation, but serves as a crucial backbone for multi-scale feature extraction. By decomposing the raw torque sequence into K narrow-band modes whose centre frequencies are learned from the data, we enable subsequent modules to focus on sub-signals with distinct spectral content. This decomposition enhances the representation capacity of the overall prediction pipeline and better aligns with the multi-scale nature of torque dynamics.

The selection of modal number K and penalty parameter is based on minimizing reconstruction error and empirical evaluation (see Section 4 for details). The resulting decomposed modes are then used as inputs to the subsequent neural sequence learning and attention fusion modules to exploit frequency-specific structure in the cutterhead torque data.

2.3. Bidirectional Gated Recurrent Unit

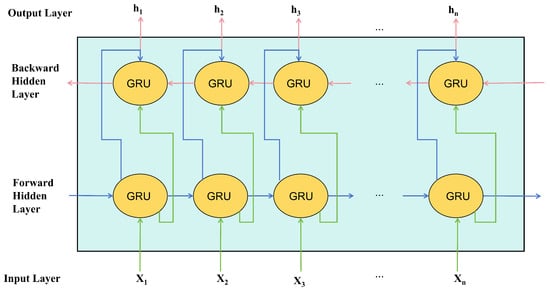

To efficiently capture temporal dependencies and contextual information within each VMD-derived torque component, we utilize a bidirectional gated recurrent unit (Bi-GRU) network as a modular temporal encoder. Bi-GRU processes each decomposed sub-signal in both forward and backward time directions, generating compact sequence embeddings that serve as the basis for downstream feature fusion.

While the Bi-GRU model itself follows established deep learning practices [38,39], its application here is tailored for frequency-specific modeling. In this framework, the Bi-GRU hidden states for all modal components are not end predictions; rather, they are aggregated and further refined by attention and energy-constrained fusion modules (see Section 2.4 and Section 2.5).

This design ensures that temporal knowledge extracted from both directions is preserved and effectively merged, enabling the model to learn both short-term dynamics and latent trends in highly nonlinear, non-stationary TBM torque signals. The process is illustrated schematically in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram of Bi-GRU basic architecture.

2.4. Self-Attention

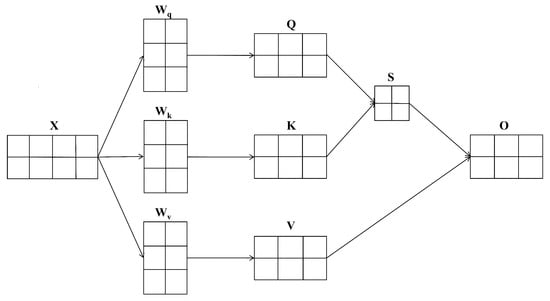

Building upon the modular outputs of Bi-GRU, we introduce a self-attention layer to further refine the feature set by modeling long-range dependencies and adaptive feature weighting.

Unlike conventional sequences where self-attention is applied to raw signals or end-to-end neural outputs, our approach leverages self-attention for two interrelated tasks: (1) adaptively aggregating temporal information across Bi-GRU outputs for each VMD sub-signal, and (2) contextually fusing predictions across different frequency bands to form holistic multi-frequences representations.

Technically, the self-attention mechanism follows standard practice [40] but is tailored in its placement and operational logic: query, key, and value matrices are built from the intermediate hidden states, allowing the network to dynamically adjust the influence of each time step and frequency mode based on learned global relevance. The computational details are illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic diagram of the basic architecture of self-attention mechanism.

The innovation here lies not in attention itself, but in our strategic multi-level use of attention for temporal-frequency fusion and energy-aware physical consistency (see Section 2.5), which together form the cornerstone of our enhanced torque prediction methodology.

2.5. Real-Time Prediction Method of Cutterhead Torque Based on Fusion Signal Decomposition Mechanism and Physical Constraints

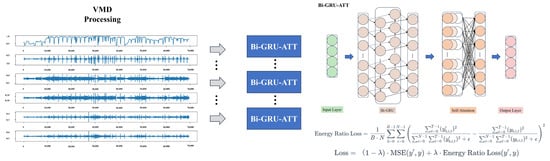

In order to achieve real-time multi-step prediction of TBM cutterhead torque, an intelligent prediction method (VBGAP) is proposed. This method is based on fusing a signal decomposition mechanism with physical constraints on the basis of several algorithms mentioned in the previous sections. Firstly, the raw cutterhead torque data is decomposed into K modal components with different frequencies based on the VMD method. Subsequently, a Bi-GRU-ATT model was constructed for each modal component, drawing upon the principles of Bi-GRU and the self-attention mechanism. This model was utilised to discern the temporal relationships and intrinsic modes inherent within each modal component, facilitating their prediction on an individual basis. Subsequently, the predicted future time series of each modal component are linearly superimposed to obtain a multi-step prediction of the overall cutterhead torque sequence. The flowchart illustrating the overall method is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The overall flow chart of the proposed method.

It is important to note that in this process, an original additional loss function is proposed. This function is based on modal energy conservation and is termed the energy occupancy loss. The formulation for this function is shown in Equation (9). The objective of this loss function is to quantify the discrepancy in energy distribution between the predicted and actual signals. Its fundamental logic is to assess the similarity in energy distribution between the predicted and actual signals by calculating the energy occupancy ratio of the predicted and actual signals on each sub-signal, and by calculating the squared error on the difference of these occupancy ratios. The model is designed to minimise energy share loss, thereby ensuring both the accuracy of the predicted values and the consistency of the energy distribution of the predicted signal with the true signal. Subsequently, integration of the MSE and the Energy Ratio Loss is achieved by establishing a tunable weighting factor, designated as . The model is then employed to minimise the Energy Ratio Loss. The overall loss function of the model is demonstrated in Equation (10). The combination of these two types of losses enables the model to learn both the underlying patterns and to capture the energy distribution characteristics of the data during training. This process achieves a balance between prediction accuracy and consistency of physical meaning.

where B is the batch size, N is the number of sub-signals, T is the time step, is the predicted value of the b-th batch, the i-th sub-signal, the t-th time step, is the true value of the b-th batch, the i-th sub-signal, the t-th time step, the small positive number to prevent the denominator from being zero, the default value is 1 × . MSE represents the mean square error loss function, is an adjustable weight coefficient.

2.6. Model Evaluation Indicators

In order to better assess the prediction performance of the model, this study adopts several evaluation indexes to quantitatively assess the model performance. These include the root mean square error (RMSE), the mean absolute error (MAE), the mean absolute percentage error (MAPE), and the coefficient of determination (). It is evident that these metrics offer a comprehensive reflection of the prediction accuracy and goodness-of-fit of the model from a variety of perspectives. Consequently, they provide a multi-dimensional quantitative basis for the objective assessment of model performance.

where represents the actual value, represents the predicted value.

3. Case Study

3.1. Project Overview

The tunnel project under scrutiny in this paper is situated in a water diversion project tunnel in Northeast China, which boasts a total boring length of 19,771 m, with four primary rock types: granite, limestone, tuff and diorite. The primary technical parameters of the open-type hard rock tunnel boring machine employed in the present project are enumerated below: Cutter diameter: 7.93 m, Number of hobs: 56, Rated torque: 9410 kN·m, Maximum thrust: 23,260 kN. Propulsion system cylinder stroke: 1.8 m Rated propulsion speed: 120 mm/min. The machine is equipped with 199 data acquisition channels, capable of recording key parameters such as cutter speed, thrust, and torque in real time at a frequency of 1 Hz. The machine is equipped with 199 data acquisition channels, the purpose of which is to record the blade speed, thrust, torque and other key parameters in real time at a frequency of 1 Hz. The cutter drive employs a motor-reducer system, and the breakaway torque is reported to reach 12,615 kN·m. The conveyor capacity of the host belt conveyor is commensurate with the demand of large-diameter cutter breaking. Table 2 presents detailed parameter information.

Table 2.

Overview of key parameters of TBM equipment.

3.2. Data Pre-Processing

The present study focuses on the TBM digging parameter data from three consecutive days of the project. However, it should be noted that these raw data cannot be used directly for the training of the model and require preliminary processing.

During the process of TBM, a substantial amount of invalid data is generated between two adjacent tunnel cycles. The data collected by the TBM encompasses both boring and non-boring data; however, the non-boring data is of limited utility for the study and is thus eliminated post-identification. When the value of Equation (8) is equivalent to zero, the TBM can be regarded as being in a state of non-digging.

where V is the cutter speed, F is the total thrust, P is the penetration, and T is the cutterhead torque. Records with S = 0 are discarded as invalid.

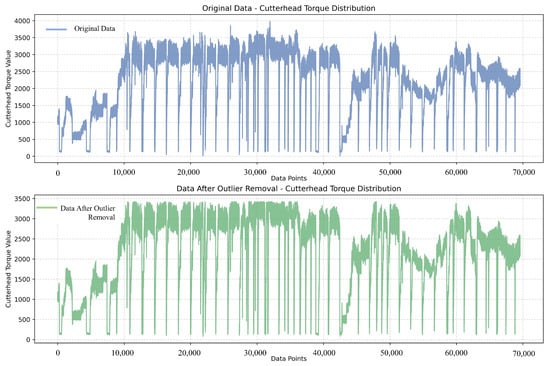

Raw recordings are heavily corrupted by outliers and noise stemming from site conditions, machinery behaviour, and operator skill, all of which degrade model performance. To cleanse the data, we apply the Isolation Forest algorithm to identify and remove anomalous observations before denoising.

In this paper, the isolated forest algorithm was implemented using the scikit-learn library, with the relevant hyperparameters set accordingly. These included the number of trees () and the amount of subsamples (). The path length of each data point was calculated using Equation (9) for the TBM cutterhead torque data, and the dynamic thresholding method was employed to determine the anomaly boundaries:

where is the mean value of the scores and is the standard deviation, k is adjusted to 2 according to the TBM working conditions. is the anomaly threshold above which the samples with scores higher than this threshold will be marked as anomalous.

We compare the results obtained before and after outlier processing of three consecutive days of cutterhead torque data. As illustrated in Figure 6, the original data demonstrates significant fluctuations, particularly in the torque values of the cutter disc, which exhibit substantial high and low variations. These outliers may be attributed to measurement errors, sensor failure or other abnormal factors. In contrast, the processed data exhibits a reduced fluctuation range and is more concentrated within a reasonable range, manifesting as a more stable and smooth trend. This is advantageous for subsequent analysis and modelling.

Figure 6.

Comparison of the treatment effect of abnormal torque value of TBM cutterhead.

Subsequently, in order to circumvent the repercussions of disparate data scales on model performance, the normalisation of data is facilitated by the implementation of Equation (10) following the elimination of outliers. This, in turn, serves to mitigate the deleterious impact that fluctuations in the dimensions and sizes of feature parameters during model training exert.

where is the original data at moment t; is the minimum value of the set of data; is the maximum value of the set of data; is the data at moment t after normalisation.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Experiment and Results

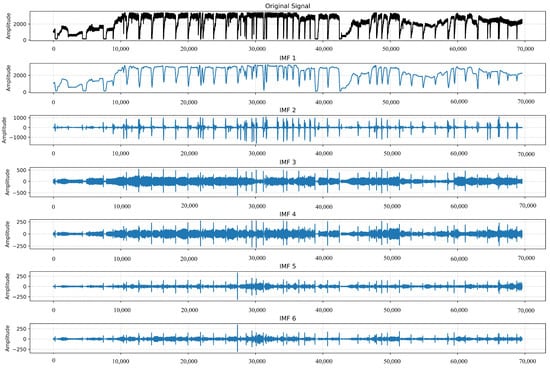

To mitigate overfitting and align with real-world tunneling conditions, the cleaned dataset is split into training, validation, and test subsets in an 8:1:1 ratio, preserving the original time sequence. The model was trained using an adaptive moment estimation (Adam) optimiser and optimised by an early stopping algorithm, with the patience value (Patience) set to 5 and 32 samples used in each iteration. Concurrently, the pivotal parameters, K and , which are indispensable for the VMD decomposition process, were preliminarily calibrated through the grid search method in conjunction with the other hyperparameters of the model. The optimisation outcomes yielded K = 6 (a choice that is further justified through a comprehensive performance analysis across multiple K values in Section 4), = 2000, and the remaining optimal hyperparameters are delineated in Table 3.

Table 3.

Search grids and final tuned configuration.

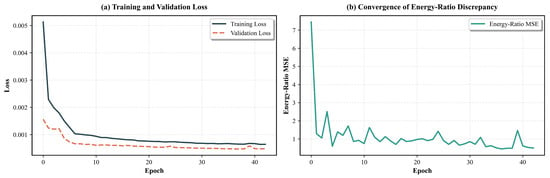

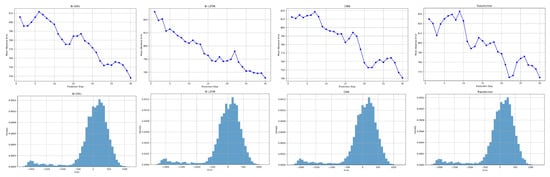

The remaining VMD decomposition parameters are stipulated as such: the time interval, tau = 0.1; the DC component, DC = FALSE to ensure its non-retention; the initialisation method, random initialisation, init = random; and the tolerance, tol = 1 ×. The execution of the VMD, based on the aforementioned parameters, yields six modal components with differing centre frequencies. The results of the VMD decomposition are presented in Figure 7. Subsequently, the model is trained using each of the optimised optimal hyper-parameters, and the variation of the loss curve of the model is shown in Figure 8. As the training process is undertaken, there is a gradual decline in the loss fluctuation of the training set, which ultimately stabilises. A comparable trend is exhibited by the loss fluctuation of the validation set, which attains its lowest value around the 38th round of training. This observation signifies that the model has attained convergence.

Figure 7.

Original waveform and its VMD-based modal splitting.

Figure 8.

Training and Validation Loss Curves.

The remaining VMD decomposition parameters are defined as follows: the time interval ; the DC component, DC = FALSE, to ensure it is not preserved; the initialization method is set to random (); and the tolerance is set to . The VMD procedure, based on these parameters, produces six modal components with distinct central frequencies, as shown in Figure 7. The model is subsequently trained with each set of optimized hyperparameters, and the evolution of the training process is illustrated in Figure 8. Specifically, panel (a) of Figure 8 demonstrates the progression of both the training and validation losses over the course of training epochs. Both losses decrease rapidly during the initial epochs, reflecting effective learning, and gradually stabilize as training proceeds. Notably, the validation loss reaches its minimum around the 50th epoch, indicating the point of best generalization and suggesting model convergence. Panel (b) of Figure 8 presents the convergence of the energy-ratio mean squared error (MSE), which quantifies the discrepancy in modal energy distribution between predicted and ground truth signals. This metric also converges rapidly within the first 10 epochs and maintains a low value throughout, confirming the model’s ability to preserve the physical consistency of the reconstructed signal.

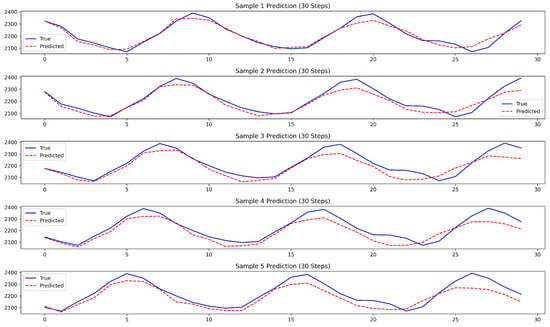

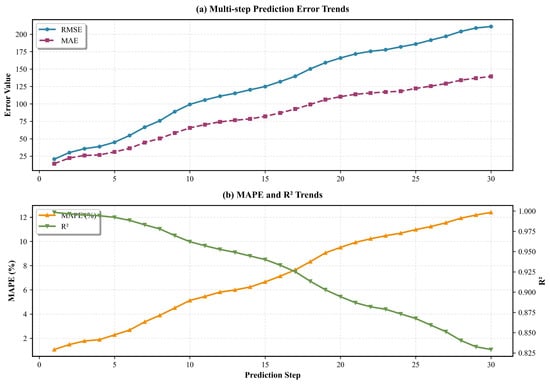

In order to verify the prediction performance of the proposed method and to consider the information loss in the signal decomposition-reconstruction process, a comparison was made of the prediction results of the test set with the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal (the result of linear superposition of real sub-signals) and the original cutterhead torque signal, respectively. As illustrated in Figure 9, the multi-step prediction results of the proposed method on the test set are compared with the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal (with 5 prediction samples) after training in this experiment. As illustrated in Table 4 and Figure 10, the paper presents the step-by-step prediction accuracy metrics and their trends in relation to the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal on the test set. It can be seen that the algorithm proposed in this paper has high prediction accuracy for the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal. The RMSE, MAE, MAPE and R2 values of the 30-step prediction results are not less than 161.24, 113.72, 7.48% and 0.9346, respectively.

Figure 9.

The multi-step prediction results of VBGAP for the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal (taking 5 prediction samples as an example).

Table 4.

The multi-step prediction performance of VBGAP for the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal on the test set.

Figure 10.

The multi-step prediction accuracy change of VBGAP for reconstructing the cutterhead torque signal. ((a) multi-step prediction error trends (RMSE and MAE); (b) MAPE and R2 trends).

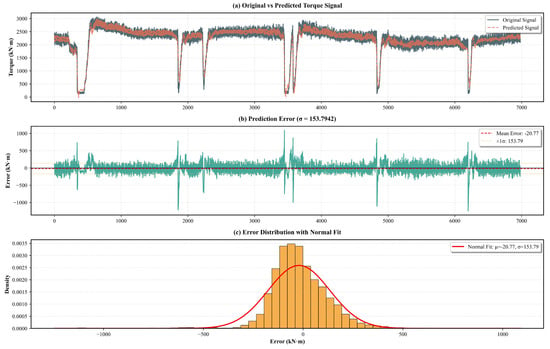

As illustrated in Figure 11, these figures demonstrate the prediction results, absolute errors, and error distributions of VBGAP on the test set in relation to the prediction results for the original cutterhead torque signal when updating the prediction results using a moving window of size 30 at a prediction length of 30. As illustrated in Table 5, the prediction accuracy for the test set is demonstrated for both the reconstructed and original cutterhead torque signals. It is evident that the proposed method also yields favourable prediction outcomes for the original cutterhead torque signal. Conversely, the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal is equivalent to the result of the noise reduction of the original cutterhead torque signal. This renders the prediction of the reconstructed cutterhead torque signal more meaningful in an engineering context.

Figure 11.

VBGAP forecast versus actual cutterhead torque and its absolute error. ((a) comparison of original and predicted torque signals; (b) prediction error time series; (c) error distribution with normal fit).

Table 5.

Comparison of prediction accuracy of VBGAP on original and reconstructed blade torque signals on test set.

4.2. Discussion and Analysis

Regarding the selection of the VMD mode number K, our primary criterion for choosing K was empirical performance, guided by the trade-off between decomposition granularity and model generalization. As shown in Table 6, we evaluated K values ranging from 2 to 9. The results indicate that yields the best overall prediction accuracy across all metrics (RMSE, MAE, MAPE, and ). Specifically, at , the model achieves the lowest RMSE (150.743) and MAPE (9.71%) and the highest (0.9174). Increasing K beyond 6 does not lead to further improvement; instead, performance slightly degrades or plateaus, suggesting that over-decomposition may introduce redundant or noisy sub-signals that hinder generalization. Conversely, fewer modes () result in coarser decomposition and poorer predictive performance, likely because important multi-scale features of the torque signal remain unseparated. Therefore, represents an optimal balance: it provides sufficient modal resolution to capture the underlying physical processes (e.g., distinct frequency components related to cutter–rock interaction, rotational harmonics, and operational fluctuations) while avoiding excessive complexity that could increase computational cost and risk of overfitting. This data-driven selection ensures that our model leverages the most informative signal decomposition for accurate multi-step torque forecasting.

Table 6.

Prediction performance of VBGAP under different numbers of VMD modes.

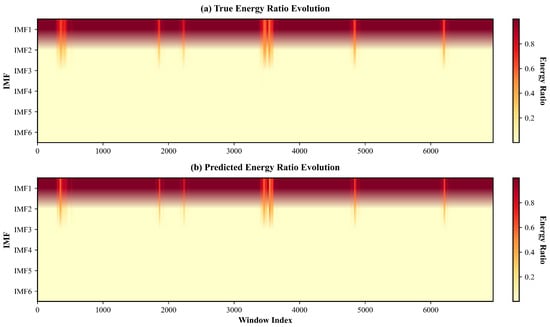

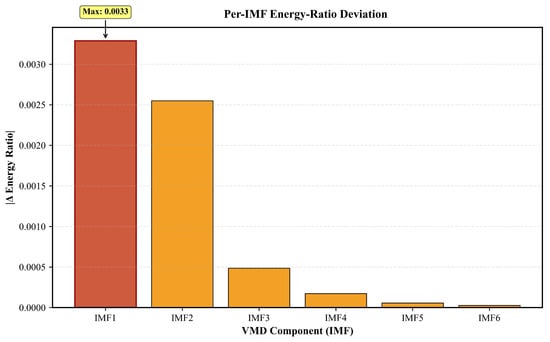

To further explore the mechanism by which the energy ratio loss function constrains the energy distribution in the reconstructed signal and thereby reduces information loss, we conducted a series of visual analyses. Physically, the energy ratio loss acts as a soft conservation law: it penalizes any artificial creation or dissipation of modal energy during the decomposition–reconstruction cycle, mimicking the principle of energy conservation that governs real cutterhead dynamics. By keeping the relative energy share of each IMF constant, the loss discourages the model from “borrowing” energy from high-frequency modes to fit low-frequency trends (or vice-versa), a situation that often produces visually plausible but physically implausible torque trajectories. Figure 12 presents heatmaps of the energy ratio evolution for each VMD modal component (IMF) across all data windows. Panel (a) shows the true energy ratio evolution, while panel (b) displays the predicted ratios generated by the proposed model. It is evident that the predicted energy distribution closely tracks the true distribution for the dominant components (IMF1 and IMF2), demonstrating the model’s ability to preserve modal energy profiles over time. Lower-order IMFs (IMF3–IMF6) maintain minor yet stable energy ratios, indicating that the energy ratio loss function effectively compels the model to maintain a physically meaningful modal energy structure throughout the prediction process. Figure 13 further reveals that energy ratio deviations predominantly arise in the leading modal component (IMF1), with higher-order components contributing negligible error. This outcome demonstrates that the energy ratio loss function specifically targets the principal energetic content, enabling the model to effectively constrain and preserve the most informative features.

Figure 12.

Heatmaps of energy ratio evolution for each VMD modal component (IMF) across all windows. (a) True energy ratio evolution. (b) Predicted energy ratio evolution.

Figure 13.

Bar chart of per-IMF energy ratio deviation. The largest deviation is observed in IMF1, while higher-order components contribute negligibly. This indicates that the energy ratio loss function primarily constrains the main energetic modal component. (The varying shades of colour in the diagram are intended to indicate the relative magnitude of the values.)

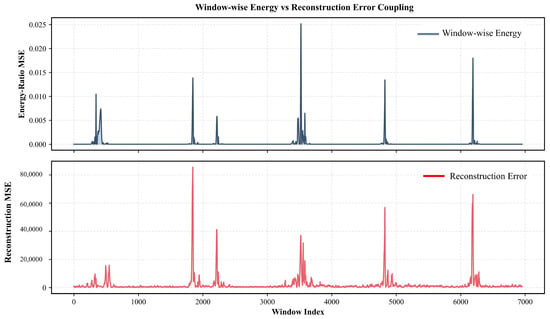

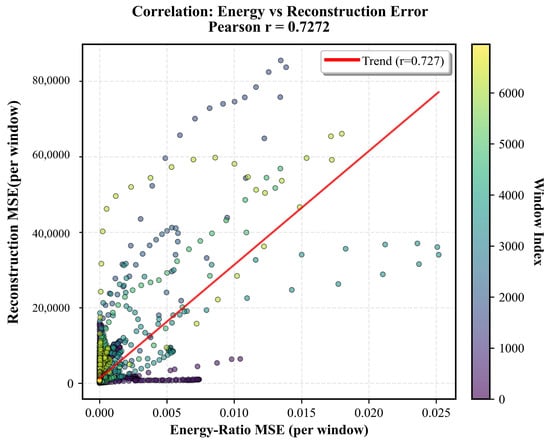

Beyond global temporal consistency, we investigated the coupling between window-wise energy ratio error and reconstruction error. Figure 14 illustrates this relationship, where peaks in the energy ratio mean squared error (MSE) consistently align with spikes in the reconstruction MSE, confirming that deviations in modal energy distribution directly contribute to increased information loss in signal reconstruction. This connection is quantified in Figure 15, where a moderate positive correlation (Pearson ) is observed between energy ratio MSE and reconstruction MSE for individual windows. These results underscore that improved matching of modal energy profiles not only enhances physical interpretability, but also directly translates into lower operational error and better predictive fidelity. These analyses validate that introducing energy ratio loss facilitates modal energy consistency and significantly mitigates information loss in multicomponent signal prediction tasks.

Figure 14.

Window-wise coupling of energy ratio mean squared error (MSE) and signal reconstruction MSE. Peaks in energy-ratio error correspond to spikes in reconstruction error, indicating regions of reduced modal energy consistency and increased information loss.

Figure 15.

Scatter plot illustrating the positive correlation between window-wise energy ratio MSE and reconstruction MSE. The Pearson correlation coefficient () quantifies the coupling between modal energy distribution error and reconstruction error.

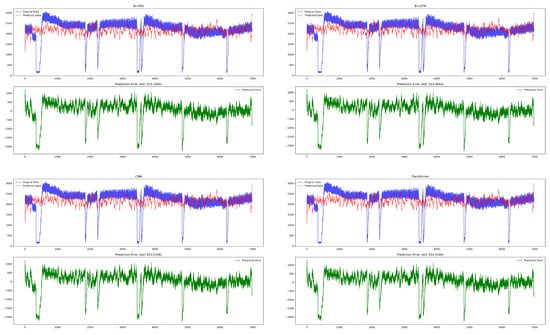

The study further corroborates the proposed approach by benchmarking it against four widely used deep-learning architectures—Bi-GRU, Bi-LSTM, CNN, and Transformer—on an authentic cutter-head torque test set. Every contender is trained under an identical protocol and structure, while their hyper-parameters are fine-tuned with a grid-search routine to guarantee a fair comparison. As illustrated in Figure 16 and Figure 17, the prediction outcomes and multi-step prediction error variations of these various deep learning models for the original cutterhead torque signal test set are demonstrated. Notably, although Bi-LSTM and Transformer are capable of capturing temporal dependencies, they struggle to model the non-stationary and multi-scale characteristics inherent in TBM torque signals, leading to error accumulation over longer prediction horizons. CNN, despite its local feature extraction capability, lacks the capacity to effectively encode long-range temporal dynamics, resulting in phase lag and amplitude underestimation in multi-step forecasts [41]. Bi-GRU, while more parameter-efficient than Bi-LSTM, still fails to disentangle the entangled frequency components, especially under varying geological conditions. It can be seen that the prediction accuracy of various methods is not much different. However, it is obvious that their accuracy is much lower than the method proposed in this paper. Specifically, as shown in Table 7, VBGAP reduces RMSE by 45.1%, 44.8%, 46.8%, and 45.5% compared to Bi-GRU, Bi-LSTM, CNN, and Transformer, respectively. More critically, the R2 score of VBGAP reaches 0.9174, significantly outperforming the second-best model (Bi-LSTM at 0.9011), indicating a superior ability to explain the variance in the torque signal. Meanwhile, the prediction error curves of several models demonstrate a high degree of similarity to the shapes of the original cutterhead torque signals, particularly with regard to the volatility of the signals. This finding suggests that the volatility of the original cutterhead torque signals is a significant factor contributing to the inadequate prediction accuracy of the models. The method outlined in this paper involves the signal decomposition and reconstruction by VMD, followed by a reduction in information loss through the implementation of an additional loss function based on modal energy conservation. This approach enables the model to accurately perceive the volatility of the original cutterhead torque signal, while simultaneously retaining essential fluctuation information and reducing data noise. Unlike end-to-end models that attempt to learn directly from raw signals, VBGAP explicitly disentangles the multi-scale frequency components, allowing each Bi-GRU submodule to specialize in a specific spectral band. This decomposition-guided specialization significantly enhances the model’s robustness to signal non-stationarity and geological variability. Consequently, this enhances the model’s prediction accuracy. As demonstrated in Figure 9 and Figure 10, the shape of the VBGAP prediction error curve is more symmetrical and more uniformly distributed. This indicates that the prediction error originates more from the high-frequency modal components in the signal decomposition-reconstruction process, as well as from the sensor noise. This is a topic that we intend to explore further in depth in our future research.

Figure 16.

Test-set forecasts of competing neural models for raw torque signals.

Figure 17.

Prediction error versus horizon length for competing deep-learning approaches.

Table 7.

RMSE, MAE, MAPE and comparison of deep models for raw blade torque forecasting.

In order to further validate the prediction performance of the proposed VBGAP method and the contribution of each algorithmic module in the method to enhance the prediction capability, individual module ablation experiments on VBGAP were conducted. Utilising the VBGAP model as a benchmark, each algorithmic module is systematically eliminated, and a comparison is made of its prediction performance. Table 8 confirms that VBGAP delivers the best forecasting accuracy among all examined models. However, the removal of any of the algorithmic modules results in a decline in model accuracy. In the present study, the loss function of the energy share is shown to play a pivotal role in the prediction process. It is demonstrated that the accuracy of the model is significantly diminished upon the removal of the loss function, thereby substantiating the efficacy of the methodology proposed in this paper. Furthermore, we explored the effect of attention head design by replacing the multi-head attention module in VBGAP with a single-head attention mechanism (denoted as VBGAP-MultiATT in Table 8). The results show a slight but consistent degradation across all evaluation metrics compared to the full VBGAP model, indicating that multi-head attention captures richer, diversified feature representations from different VMD sub-signals. This ablation confirms that the multi-head design contributes to the model’s predictive fidelity, supporting its inclusion in the proposed framework.

Table 8.

Comparison of ablation experiments with the VBGAP model.

To explain the selection of the 30-s prediction window, we conducted additional experiments evaluating forecast horizons ranging from 10 to 60 s (Table 9). The results demonstrate a clear trade-off between prediction horizon and accuracy: as the forecast window lengthens, all error metrics (RMSE, MAE, MAPE) increase while decreases, reflecting the inherent challenge of multi-step forecasting in highly dynamic TBM operations. The 30-s horizon was ultimately chosen as the operational compromise for the following reasons: (1) it provides a sufficiently long look-ahead time (30 s) to support proactive decision-making in TBM control; (2) it maintains a high prediction accuracy with an of 0.9174 and a MAPE below 10%, indicating reliable performance; and (3) beyond 30 s, the error growth becomes more pronounced (e.g., drops to 0.8871 at 40 s), suggesting a steep decline in prediction reliability. Therefore, the 30-s window strikes an optimal balance between extending the credible prediction scale and preserving acceptable forecasting precision, fulfilling the core objective of our real-time multi-step prediction framework.

Table 9.

Prediction performance of VBGAP across different forecast horizons (10–60 s).

Several decomposition-based torque prediction models exist, we conducted a comparative analysis of four common signal decomposition techniques: VMD, CEEMDAN (Complete Ensemble Empirical Mode Decomposition with Adaptive Noise), HVD (Hilbert Vibration Decomposition), and EMD (Empirical Mode Decomposition). Each method was integrated into the proposed VBGAP framework (replacing the VMD module), and their performance was evaluated on the same test set. The comprehensive results are presented in Table 10. While CEEMDAN achieves the lowest RMSE (126.45), it exhibits catastrophic failure in MAPE (1168.26%) and (0.1712), indicating severe instability and poor generalization due to mode mixing and sensitivity to noise—a known limitation of EMD-family methods for non-stationary signals. HVD, despite its extremely fast decomposition (0.06 s), yields prediction accuracy inferior to VMD (RMSE = 277.82 vs. 146.06, = 0.7207 vs. 0.9183), as it assumes a simplistic harmonic structure inconsistent with the complex, multi-component nature of TBM torque signals. EMD performs similarly poorly in terms of (0.1569) and MAPE (393.36%), suffering from endpoint effects and mode aliasing. In contrast, VMD achieves an optimal balance: it maintains high prediction accuracy ( = 0.9183, MAPE = 8.02%), requires moderate total computational time (522.81 s), and demonstrates robust performance. This aligns with findings in structural health monitoring literature, where VMD has been shown to outperform CEEMDAN and HVD in handling non-stationary vibration signals [42]. Therefore, VMD is selected not only for its empirical superiority in our task but also for its theoretical robustness in quasi-orthogonal modes from complex operational data, which is critical for reliable multi-step torque forecasting.

Table 10.

Comparative analysis of different signal decomposition methods for TBM cutterhead torque prediction.

5. Conclusions

In this study, an intelligent prediction method (VBGAP) integrating signal decomposition mechanism and physical constraints is proposed to address the problem of insufficient accuracy of real-time multi-step prediction of cutterhead torque of tunnel boring machine under complex geological conditions. A physically explicit modal decomposition of non-smooth torque time series signals is achieved through the implementation of variational modal decomposition. The experimental findings, derived from empirical data obtained from a real tunnel project in Northeast China, demonstrate that the proposed method attains an average RMSE, MAPE, and R2 of 150.743, 104.096, 9.71 and 91.74%, respectively, in a multi-step prediction task with a 30-s time step. The model demonstrates a superior performance to conventional deep learning models (including Bi-GRU, Bi-LSTM, CNN, and Transformer) in terms of prediction accuracy, as evidenced by the significantly lower prediction error. Furthermore, the distribution of prediction errors is more uniform, which serves as a testament to the model’s reliability in long-step prediction tasks. In-depth analysis based on energy ratio heatmaps, window-wise error coupling, and correlation studies provides further evidence for the effectiveness of the energy ratio loss function. The observed high temporal correspondence between spikes in energy-ratio error and reconstruction error, as well as the strong positive correlation between these metrics, verifies that constraining modal energy ratios leads directly to improved signal reconstruction accuracy and reduces information loss. The ablation experiments further demonstrate that the synergy of VMD decomposition, Bi-GRU and self-attention mechanism, as well as the energy-conserving loss function have key contributions to improve the prediction accuracy. It has been demonstrated through empirical investigation that the proposed methodology has the capacity to facilitate the anticipation of alterations in the status of the cutter, thereby optimising the configuration of the digging parameters. This, in turn, has the potential to mitigate the risk of equipment degradation and enhance the construction efficiency.

The contributions of this study are as follows: (1) The original signal is decomposed into a set of narrow-band modes by VMD, and combined with the hybrid deep learning model to model separately, which effectively solves the problem of non-stationary signal feature extraction. (2) An energy proportion loss function is proposed, which suppresses the energy distribution deviation in signal reconstruction from the perspective of physical constraints, and enhances the physical consistency and generalization ability of the model. (3) The multi-step prediction of high-precision cutterhead torque in 30 s is realized, which provides reliable technical support for real-time control and intelligent decision-making of TBM tunneling parameters. Although VBGAP has achieved good results, the problem of information loss in signal decomposition-reconstruction and the prediction of high-frequency modal components need to be further solved. We will explore more solutions in future research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.F. and Y.Y.; methodology: J.F.; software: J.F., Y.H. and Y.L.; validation: S.C.; formal analysis: J.F.; investigation: S.C.; resources: Y.H. and Y.Y.; data curation: Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation: J.F.; writing—review and editing: J.F., Y.H., Y.Y., Y.L. and S.C.; visualization: J.F. and Y.L.; supervision: Y.H. and Y.Y.; project administration: Y.Y.; funding acquisition: Y.H. and Y.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Wuhan Science and Technology Achievement Transformation Project (2024030803010163), and the 2024 Wuhan Metropolitan Circle Collaborative Innovation Science and Technology Project of China (2024070904020435).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in this article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the staff who participated in the project.

Conflicts of Interest

Author You Ying was employed by the Hubei Provincial Key Laboratory of Modern Manufacturing Quality Engineering; the remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Pang, S.; Hua, W.; Fu, W.; Liu, X.; Ni, X. Multivariable real-time prediction method of tunnel boring machine operating parameters based on spatio-temporal feature fusion. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2024, 62, 102924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.P.; Zhai, S.F. Estimation of the cutterhead torque for earth pressure balance TBM under mixed-face conditions. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2018, 74, 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ates, U.; Bilgin, N.; Copur, H. Estimating torque, thrust and other design parameters of different type TBMs with some criticism to TBMs used in Turkish tunneling projects. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2014, 40, 46–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, L. Development of Theoretical Equations for Predicting Tunnel Boreability. Ph.D. Thesis, Colorado School of Mines, Golden, CO, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Wang, M.Y.; Xia, Y.P.; Rong, X.L. Calculation model of cutterhead torque for earth pressure balance shield. J. Zhejiang Univ. (Eng. Sci.) 2014, 48, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar]

- Samadi, H.; Hassanpour, J. EPB-TBM cutterhead torque and thrust modelling in rock tunnels through an analytical method and TSFS model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, L.; Xie, W.; Zhang, J. Sequential and iterative distributed model predictive control of multi-motor driving cutterhead system for TBM. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 46977–46989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, M.; Cai, Z.; Qu, C.; Jin, L. Dynamic numerical simulation of cutterhead loads in TBM tunnelling. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2017, 70, 286–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faramarzi, L.; Kheradmandian, A.; Azhari, A. Evaluation and optimization of the effective parameters on the shield TBM performance: Torque and thrust—using discrete element method (DEM). Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2020, 38, 2745–2759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Chen, Z.; Luo, H.; Wang, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, L.; Ling, D.; Jing, L. Tunnel boring machines (TBM) performance prediction: A case study using big data and deep learning. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 110, 103636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, K.; Narihiro, O.; Ikeda, H.; Adachi, T.; Kawamura, Y. Soft ground micro TBM jack speed and torque prediction using machine learning models through operator data and micro TBM-log data synchronization. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 9728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, D.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Li, Z.; Li, P.; Chen, Z. Advance prediction of collapse for TBM tunneling using deep learning method. Eng. Geol. 2022, 299, 106556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Lu, D.; Ma, Y.; Li, J.; Tian, T. Analysis and intelligent prediction for displacement of stratum and tunnel lining by shield tunnel excavation in complex geological conditions: A case study. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 22206–22216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Z.Q.; Zhai, W.J.; Han, A.M.; Chen, D.; Hao, B.; Li, T.; Chen, C. Predictive research of cutterhead torque for metro shield boring machine based on symbolic regression algorithm. Urban Mass Transit 2021, 24, 127–131. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cachim, P.; Bezuijen, A. Modelling the torque with artificial neural networks on a tunnel boring machine. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2019, 23, 4529–4537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Q.; Huang, X.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, S. TBM performance prediction using LSTM-based hybrid neural network model: Case study of Baimang River tunnel project in Shenzhen, China. Undergr. Space 2023, 11, 130–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long short-term memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.S.; Shen, S.L.; Zhang, N.; Zhou, A. Modelling the performance of EPB shield tunnelling using machine and deep learning algorithms. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 101177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wu, H.N.; Chen, R.P.; Meng, F.Y.; Wang, H.B. A critical evaluation of machine learning and deep learning in shield-ground interaction prediction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2020, 106, 103593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Shi, G.; Tao, J.; Yu, H.; Jin, Y.; Lei, J.; Liu, C. Precise cutterhead torque prediction for shield tunneling machines using a novel hybrid deep neural network. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 151, 107386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Li, D.; Chen, E.J.; Liu, Y. Dynamic prediction of mechanized shield tunneling performance. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, P.; Guo, D.; Li, X.; Chen, Z. Advanced prediction of tunnel boring machine performance based on big data. Geosci. Front. 2021, 12, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Zhang, L. Spatio-temporal feature fusion for real-time prediction of TBM operating parameters: A deep learning approach. Autom. Constr. 2021, 132, 103937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Qin, C.; Tao, J.; Liu, C. A VMD-EWT-LSTM-based multi-step prediction approach for shield tunneling machine cutterhead torque. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 228, 107213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Shi, G.; Tao, J.; Yu, H.; Jin, Y.; Xiao, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, C. An adaptive hierarchical decomposition-based method for multi-step cutterhead torque forecast of shield machine. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 175, 109148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, E.; Wang, S. Prediction of tunnel boring machine operating parameters using various machine learning algorithms. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2021, 109, 103699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumder, I.; Dash, P.K.; Bisoi, R. Variational mode decomposition based low rank robust kernel extreme learning machine for solar irradiation forecasting. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 171, 787–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głąb, K.; Wehrmeyer, G.; Thewes, M.; Broere, W. Predictive machine learning in earth pressure balanced tunnelling for main drive torque estimation of tunnel boring machines. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 146, 105642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Yang, J.; You, Y.; Fu, J.; Zheng, X.; Zhang, C. Multi-output prediction for TBM operation parameters based on stacking ensemble algorithm. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, l152, 105960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Qin, C.; Tao, J.; Liu, C.; Liu, Q. A multi-channel decoupled deep neural network for tunnel boring machine torque and thrust prediction. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 133, 104949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, F.; He, X.; Armaghani, J.; Xu, H.; Liu, X.; Sheng, D. Real-time forecasting of TBM cutterhead torque and thrust force using aware-context recurrent neural networks. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2024, 152, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, T.; Zhang, T.; Song, X. A novel hybrid transfer learning framework for dynamic cutterhead torque prediction of the tunnel boring machine. Energies 2022, 15, 2907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, K.; Liu, S.; Su, C.; Zhang, Q. A multi-stage learning method for excavation torque prediction of TBM based on CEEMD-EWT-BiLSTM hybrid network model. Measurement 2025, 247, 116766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Hou, Y.; Yang, S. Real-time prediction of tunnel boring machine thrust based on multi-resolution analysis and online learning. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 5212–5227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, Y.; Yang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, X. Multi-step prediction of TBM tunneling speed based on advanced hybrid model. Buildings 2024, 14, 4027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomiretskiy, K.; Zosso, D. Variational mode decomposition. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2014, 62, 531–544. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Li, X.; Yang, L.; Qu, H.; Wang, Y.; Hao, C. Application of variational mode decomposition in power system harmonic detection. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2018, 46, 69–76. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton, J. Ian Goodfellow, Yoshua Bengio, and Aaron Courville: Deep learning. Genet. Program. Evolvable Mach. 2018, 19, 305–307. [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lecun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-based learning applied to document recognition. Proc. IEEE 1998, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Civera, M.; Surace, C. A comparative analysis of signal decomposition techniques for structural health monitoring on an experimental benchmark. Sensors 2021, 21, 1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.