Abstract

Hydraulic fracturing is crucial for the effective development of unconventional oil and gas reservoirs. This paper systematically reviews the damage issues caused by conventional fracturing fluids in tight unconventional reservoirs, highlighting problems such as significant formation damage and high risks of scale deposition and plugging. To address these shortcomings, a phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid is proposed and compared with a guar gum fracturing fluid and slickwater fracturing fluid. The self-propping fluid offers advantages of low damage and low fluid loss. It can undergo a phase transition to form solid particles that effectively prop the fractures, thereby significantly reducing damage such as reservoir pore structure blockage. This study demonstrates that the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid is well-suited for tight, low-permeability reservoirs due to its ability to minimize formation damage. Furthermore, the reservoir damage evaluation methodology established in this work provides an effective means for analyzing damage mechanisms and assessing effectiveness during the fracturing process.

1. Introduction

The importance of hydraulic fracturing in oil and gas extraction lies in its efficiency as a method for recovering vast unconventional hydrocarbon resources.

Conventional proppants exhibit significant performance drawbacks [1]. Due to their relatively low strength, they are prone to crushing under high formation pressure, generating fine particles (fines) [2]. This not only drastically reduces fracture conductivity but also, combined with their high density, leads to severe settling issues [3]. These factors make it difficult to transport proppants to the far ends of fractures, resulting in limited propped fracture length [4]. To ensure effective transport, fracturing operations must rely on high-viscosity carrier fluids, which increases costs and environmental impact [5]. Moreover, their poor sphericity increases fluid flow resistance, accelerates equipment wear during pumping, and raises the risk of sand plugs within fractures, ultimately compromising production efficiency [6].

The phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid represents an innovation over traditional hydraulic fracturing technology. Its core concept is to be injected as a liquid, which then transforms into solid particles within the fractures to provide propping support [7]. At the surface, this fluid is a low-viscosity, solids-free liquid, allowing it to be pumped as easily as water and to readily penetrate deep into the finest fracture networks of the formation [8]. When the fluid reaches the target depth within the fractures, the “self-propping fluid” components are activated by the formation temperature. Their molecular structure reorganizes, transitioning from a liquid to solid particles that act as proppants [9]. The complete fluid system typically consists of “phase-change” and “non-phase-change” components [10]. The phase-change component forms the solid particles to prop the fractures, while the non-phase-change component, after flowback, leaves behind interconnected open channels, providing efficient pathways for hydrocarbon flow [11].

The phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid described in this paper utilizes a formula for ultra-low density micro-nano proppants designed for unconventional reservoir fracturing: Resin composition: vinyl ester resin (DERAKANE MOMENTUM 411-350)—40 parts, α-Methylstyrene—45 parts, and isobornyl acrylate—15 parts. Functional nano-filler: hydrophobically treated nano-silica, accounting for 10% of the total mass of the resin composition. Emulsifier: Span-80 (3 parts), Tween-80 (1.5 parts), and AEO-9 (1 part), totaling 5.5 parts. Curing agent: tert-Butyl peroxybenzoate (TBPB), accounting for 1.5% of the total mass of the resin composition. Aqueous phase: deionized water (with a mass ratio of oil phase to aqueous phase of 1:3), containing 0.5% magnesium chloride as an electrolyte. Promoter: N, N-Dimethyl-p-toluidine, accounting for 0.5% of the total mass of the resin composition. The above components constitute the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid. This fracturing fluid is environmentally friendly and can undergo phase-change at the designed simulated fracture temperature to form proppants.

Phase-change self-propping fracturing technology is still under development and refinement. Current research focuses on developing high-performance phase-change materials [12]. For instance, methods such as constructing a “styrene-divinylbenzene” copolymer cross-linked structure, modifying the initiation system, or doping with inorganic fillers (e.g., nano-graphite) have been employed to produce self-generating proppants with high strength (average single-particle strength up to 56.2 N), controllable phase-change time, and rapid growth [13].

Currently, research on the damage potential of phase-change liquid materials to reservoir pore matrices remains scarce [14]. As an external fluid, fracturing fluid can cause various types of damage to the reservoir during the invasion and subsequent flowback processes [15]. For low-porosity, low-permeability gas reservoirs post-fracturing [16], it is essential to effectively control the fracturing fluid’s performance parameters to avoid exacerbating formation damage [17]. The primary factors controlling reservoir sensitivity include pore-throat characteristics [18], the type and distribution of clay minerals in interstitial materials, and the reservoir’s physical properties [19]. Invasion of fracturing fluid into the matrix can alter the morphology and structure of porous flow paths. Through mechanisms like rock swelling [20], it can further compress the already minimal pore space in shale matrices [21]. Incompatibility between the fracturing fluid and reservoir properties can lead to low fracturing efficiency, high damage, and poor production enhancement [22]. Tight sandstone reservoirs, characterized by low permeability, and fine and complex pore-throat structures, are highly susceptible to formation damage during fracturing due to factors like fluid loss and incomplete flowback [23]. Damage caused by solid residue retention from fracturing fluid is permanent and irreversible [24], making the study of the sources and mechanisms of both self-propping liquid and solid damage particularly important [25]. Research indicates that the primary reasons for permeability reduction are filter cake formation on rock surfaces and adsorption bridging plugging by residual gels and solids from the fracturing fluid [26].

Reservoir damage is defined as a series of processes that result in the reduction of the natural productivity inherent to oil and gas producing formations [27], as well as the decline in the injectivity capacity of water or gas injection wells [28]. In the course of oil and gas field development operations [29], fluids, geomechanical stresses and other adverse agents can block the hydrocarbon flow channels, which in turn leads to a reduction in the permeability of reservoir formations [30]. Hydraulic fracturing has revolutionized hydrocarbon recovery from unconventional shale plays, yet water-sensitive formations pose major challenges, as conventional water-based fracturing fluids induce clay swelling, reduce permeability, and damage reservoirs [31].

While proppants serve as a core material for hydrocarbon exploitation, they suffer from multiple inherent limitations: proppant sedimentation triggers early screen-out and reduces the coverage of effective propped zones, and fracturing fluid filtration leads to the narrowing of fracture aperture [32]. Therefore, there is an urgent need to exploit lightweight proppant materials that exhibit lower settling rates, longer transport distances, and excellent thermal-mechanical stability [33].

To clarify the damage caused by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid to the reservoir, this study conducted core damage experiments using low-permeability cores. Laboratory-prepared phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid and guar gum fracturing fluid were injected into a core flooding apparatus to damage the cores. The permeability damage was then measured. Subsequently, a configured formation water was used for reverse flooding to simulate the flowback process, and the permeability recovery was assessed. Additionally, by sectioning the cores, the invasion depth of the self-propping fluid into cores with different permeabilities was analyzed. Based on the experimental data, the damage profile of the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid was determined.

This research aims to investigate the invasion damage of the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid on cores with varying permeabilities. Since the fluid transforms into solid proppants, it presents both liquid-phase and solid-phase damage potentials. In contrast, the guar gum fracturing fluid remains liquid throughout the damage experiment. By comparing the invasion damage extent caused by both fluids, the superior advantages of the self-propping fluid in reducing core damage can be highlighted.

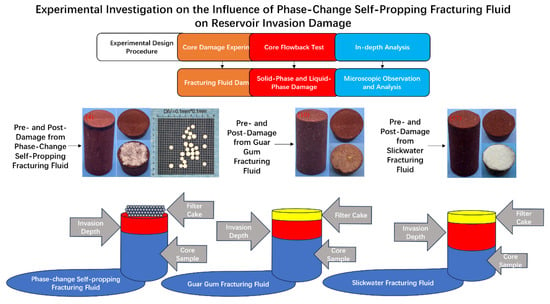

Figure 1 illustrates the distinct behaviors of the three fracturing fluids during the experiment, particularly highlighting their differing invasion depths into the core and the corresponding filter cake formation.

Figure 1.

Analysis chart of fracturing fluid’s impact on core damage.

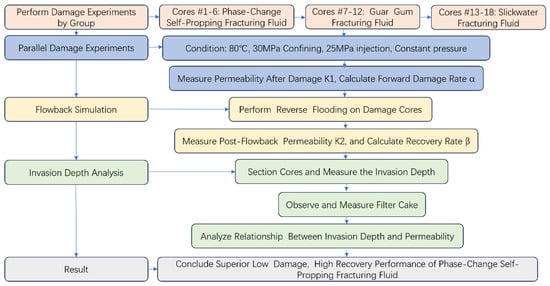

Figure 2 presents the overall research framework of this study.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of the parallel core damage experiments. The diagram illustrates the comparative experimental design for evaluating the damage and recovery performance of three fracturing fluids (phase-change self-propping, guar gum, and slickwater) on rock cores, including damage induction, flowback simulation, and invasion depth analysis.

2. Materials and Methods

Phase-change experiments were conducted on cores of different permeabilities using the research materials. The primary instruments included a core flooding apparatus and a constant-flow pump.

Absolute permeability damage refers to the reduction in the absolute permeability of the rock within the invaded zone. This can be caused by polymer invasion, clay swelling or migration, scale or wax precipitation, stable emulsions, and similar physical alterations of porosity. For this discussion, it is assumed that permanent damage does not change during cleanup and production.

The experimental procedure involved: (1) Flow experiments using cores of different permeabilities, (2) damage experiments with guar gum, slickwater fracturing fluid, and phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid, and (3) sectioning of damaged cores to determine the invasion depth. This comprehensive approach was used to analyze the damage profile and, consequently, the damage performance of the self-propping fluid under simulated reservoir conditions.

A 2% KCl solution was used to simulate formation water. The initial permeability of each core was determined using a multi-function core flooding apparatus. Due to variations in porosity and permeability, cores exhibited different degrees of damage. Flooding was conducted at a stable rate of 1–5 mL/min to simulate, as closely as possible, the damage scenario during field operations.

Core damage experiments were conducted using rock cores of the same type with similar permeability and porosity, employing three types of fluids: phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid, guar gum fracturing fluid, and slickwater fracturing fluid. Based on the damage caused by these three fracturing fluids to the same type of rock core, their invasion depths into the core were analyzed. This reflects the true damage performance of the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid during its invasion into the rock core.

By performing displacement experiments on the damaged sections of the core using the three types of fracturing fluids, we can obtain permeability data before and after the damage, thereby determining the extent of formation damage caused by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid to the rock.

First, the permeability and porosity of the cores were measured and categorized into groups based on permeability for subsequent liquid permeability testing. Core samples 1–6 were damaged using the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid; samples 7–12 were damaged using guar gum fracturing fluid; and samples 13–18 were damaged using slickwater fracturing fluid as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Core porosity data.

The cores were then saturated with a 2% KCl solution to simulate the internal state of rock under formation pressure. The phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid was injected to induce the phase change. The resulting proppant distribution and core permeability were measured to analyze the damage.

Subsequently, reverse flooding with simulated formation water was performed to simulate the flowback process. The core permeability was measured again to evaluate the recovery from the damage caused by the self-propping fluid.

Finally, for the 18 cores, an invasion depth experiment was conducted. The cores were sectioned starting from the injection end to analyze the damage depth. Based on core tightness classification, the damage performance of the fracturing fluid was assessed. The detailed experimental steps were as follows:

(1) As shown in Table 1, 18 cores with distinct permeabilities (categorized as high, medium, and low) were selected. After gas permeability and porosity measurement, they were saturated with 2% KCl, and their liquid permeability was determined via core flooding with the same solution.

(2) The cores were cleaned in an extraction tower using carbon tetrachloride, dried in an oven, and then vacuum-saturated with 2% KCl solution for 24 h.

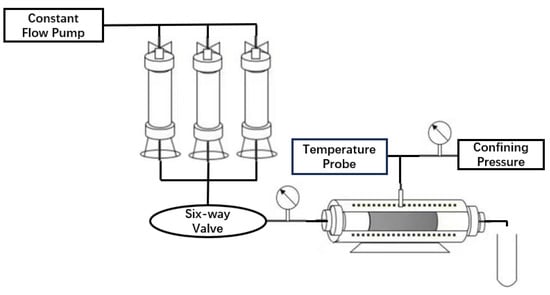

(3) As shown in Figure 4, the core was placed in a core holder. A confining pressure of 30 MPa was applied. A constant injection pressure of 25 MPa was applied at the inlet for brine displacement, with a backpressure of 25 MPa at the outlet. The injection rate fluctuated slightly with the constant-pressure pump, simulating a pressure differential across the formation. A heating jacket around the holder maintained a temperature of 80 °C to simulate reservoir conditions. The phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid was injected into the core face to undergo phase change. During this process, the permeability of the newly formed solid particles was preliminarily assessed. Figure 3 shows the apparatus for the displacement experiment.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the core flooding experiment.

(4) For complex, low-permeability tight cores, minimizing invasion volume and reducing flowback initiation pressure during flowback is crucial to quickly remove fracturing fluid and lower damage. Reverse flooding was performed to allow permeability recovery.

(5) Comparative damage experiments were conducted using guar gum fracturing fluid to evaluate the damage extent of both fluids.

The damaged cores were sectioned at specific intervals from the injection face to determine the damage depth. Trends were identified based on the inherent permeability of the cores. To analyze the damage caused by the self-propping fluid on cores of different permeability, damage rate and recovery rate were defined. A higher damage rate indicates a greater permeability reduction after damage, while a higher recovery rate indicates a stronger ability for permeability to recover.

Permeability is defined as follows:

where K is permeability, m2; Q is fluid flow rate, m3/s; is fluid viscosity Pa·s; L is core length, m; A is cross-sectional area, m2; and Δp is pressure difference, Pa.

Theorem 1.

For the steady-state laminar flow of an incompressible fluid through a homogeneous, isotropic porous medium, the volumetric flow rate Q is proportional to the cross-sectional area A of the medium, the fluid viscosity μ, and the pressure gradient Δp (or hydraulic head difference Δh) along the flow direction, and is inversely proportional to the flow path length L.

The definition of the damage rate α\alpha during forward displacement is as follows:

where K0 is the initial permeability of the core m2, and K1 is the permeability of the core after damage, m2.

Theorem 2.

In the evaluation of formation damage induced by fracturing fluids, the damage rate αα quantifies the percentage reduction in a core sample’s permeability immediately after exposure to the fracturing fluid, relative to its initial undamaged state.

The definition of the recovery rate β is as follows:

where K2 is the permeability of the core after recovery, m2.

Theorem 3.

In the context of formation damage evaluation during hydraulic fracturing, the recovery rate β quantifies the degree to which the permeability of a core sample is restored after cleanup (e.g., flowback of fracturing fluid) relative to the permeability loss incurred during damage.

3. Experimental Results and Analysis

3.1. Analysis of Core Fluid Loss

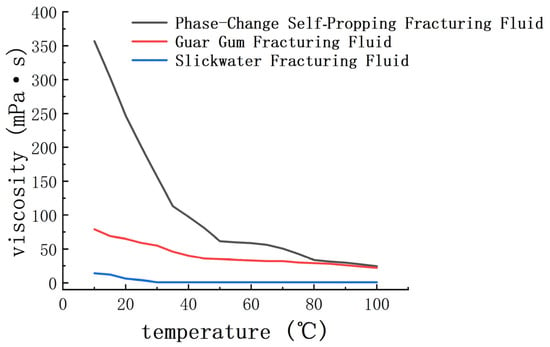

The viscosity of the three fracturing fluids was measured using a six-speed viscometer, with the initial experiment temperature set at room temperature (25 °C). The viscosity curve of the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid was recorded. For the commonly used engineering formulation of guar gum fracturing fluid, a 0.5% concentration of guar gum was combined with 0.15% ammonium persulfate. The viscosity curve obtained from slickwater fracturing fluid was prepared at a 0.5% concentration and subsequently broken with ammonium persulfate at a concentration of 0.15%. These three fracturing fluids were then used for core damage experiments.

As shown in Figure 4, at room temperature, the three fracturing fluids exhibit significant differences in viscosity. Consequently, at the initial stage of the core damage experiment, the high-viscosity fluid reduces damage to the core matrix, while the low-viscosity fluid causes substantial fluid loss. Under the experimental temperature of 80 °C, the viscosities of the three fluids converge. Notably, the phase-change and self-propping fracturing fluid forms solid spherical particles, thereby eliminating associated liquid-phase damage.

Figure 4.

Viscosity curves: phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid, guar gum fracturing fluid, and slickwater fracturing fluid.

The experimental temperature was set at 80 °C, which is both the optimal phase-change temperature and close to the actual reservoir temperature. At this temperature, the viscosities of the three fracturing fluids were comparable. The phase-change self-propping fluid undergoes phase-change to form spherical solid particles. The size of these particles is predominantly determined by the shear duration and rate applied to the fluid prior to phase change.

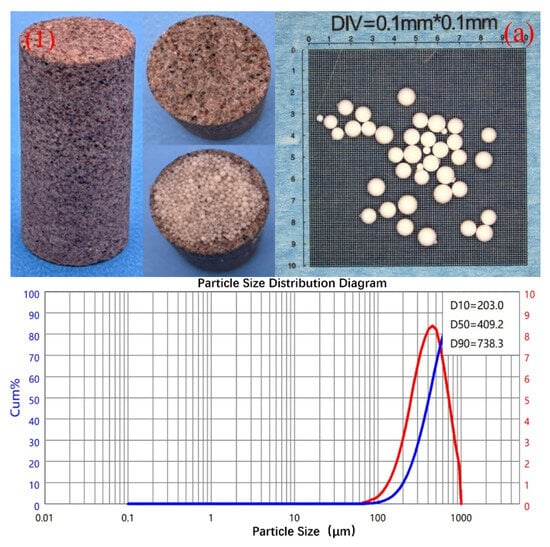

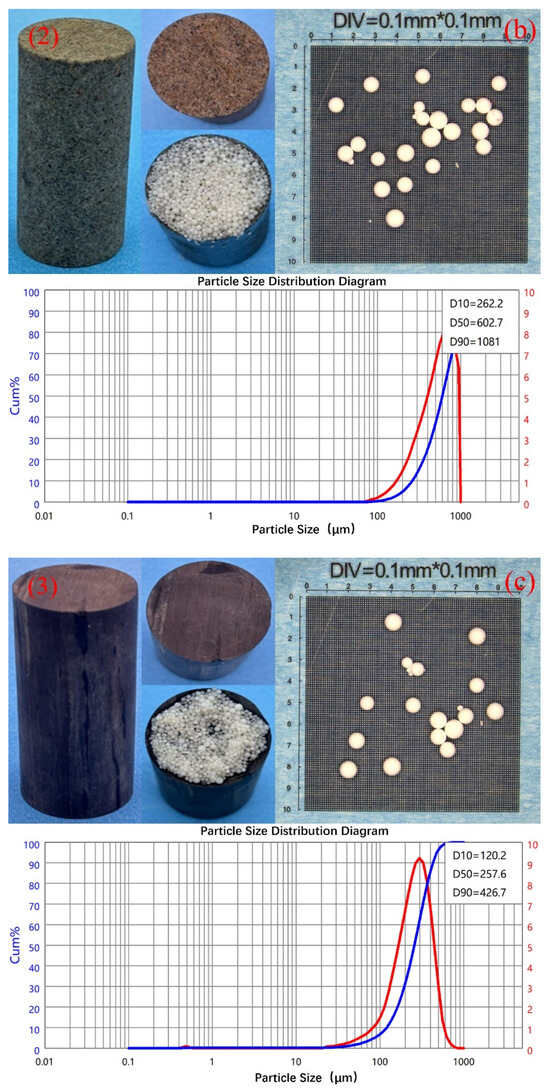

In the displacement experimental apparatus, the solid particles formed by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid were well-distributed and exhibited superior sphericity compared to conventional ceramic or quartz sand proppants. Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9 present microscopic images and particle size distributions (The BT-9300S laser particle size analyzer is a new model developed by Bettersize Instruments Ltd., Dandong, China) of the solid particles formed inside the core holder across different core samples. The results indicate that these particles possess regular shapes, well-defined edges, and a concentrated size distribution, demonstrating favorable uniformity.

Figure 5.

Solid particles formed at the face of the core by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid and their particle size distribution ((a–f) correspond to Cores #1 through #6, respectively).

Figure 6.

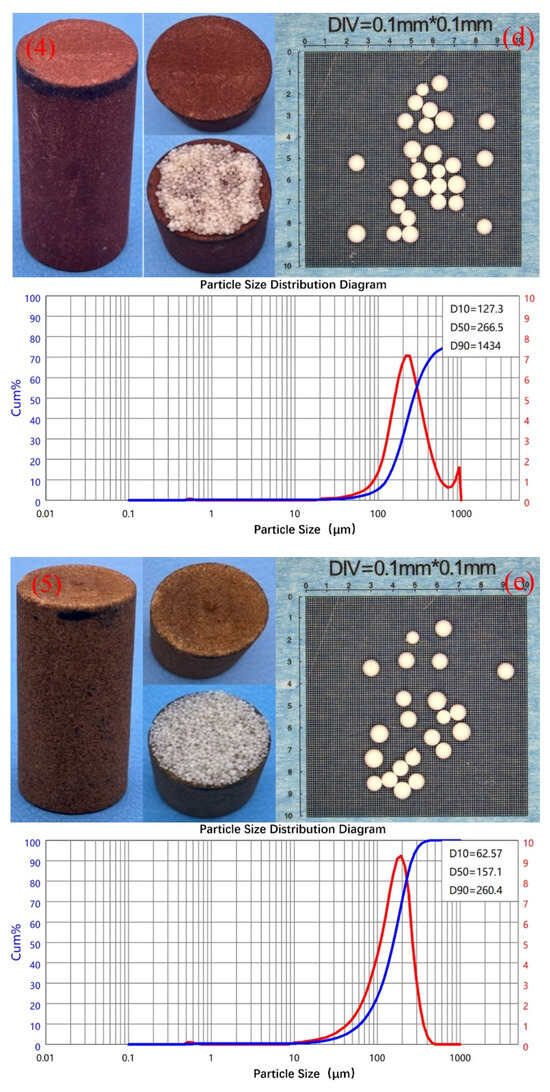

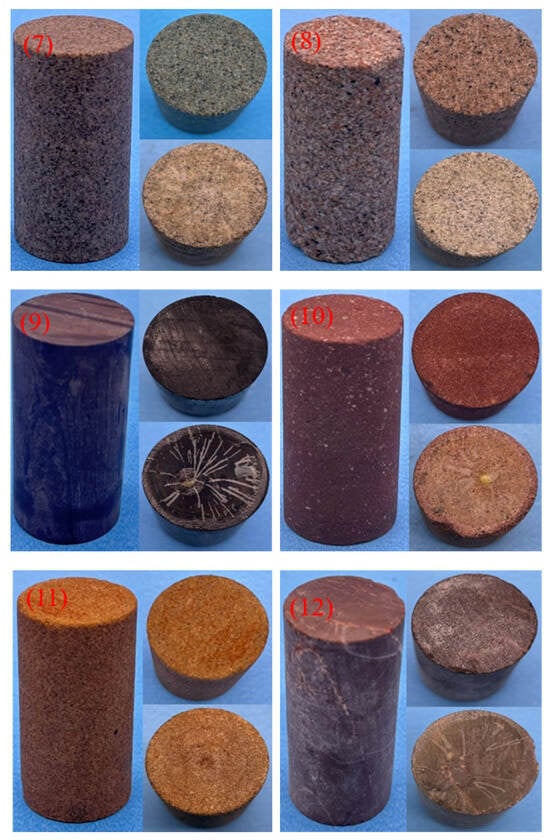

Core before and after guar gum fracturing fluid damage.

Figure 7.

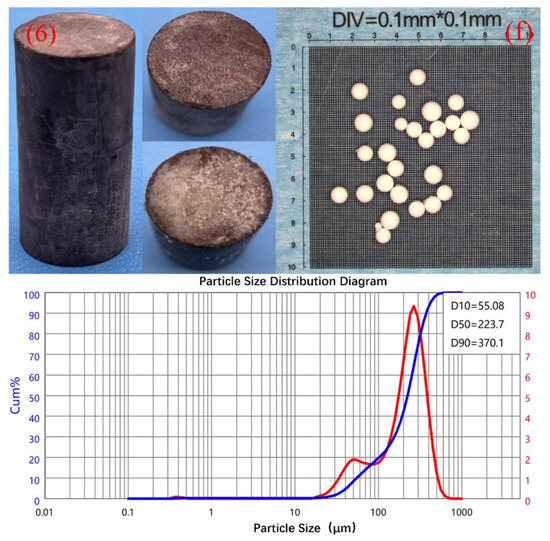

Core before and after slickwater fracturing fluid damage.

Figure 8.

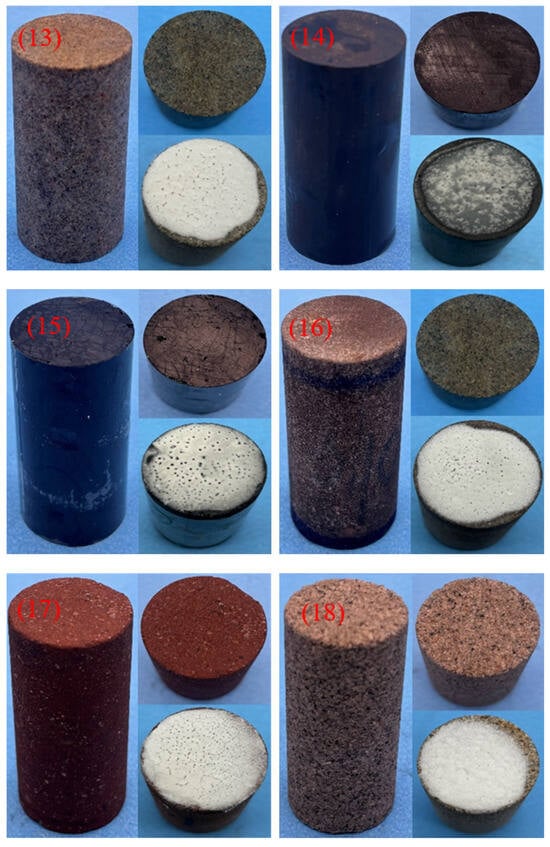

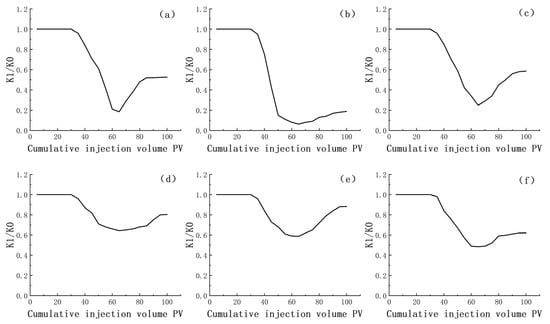

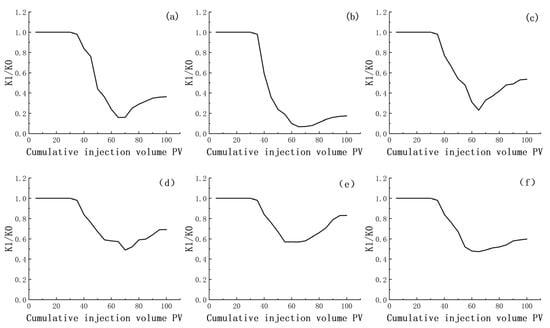

Variation of core permeability recovery after damage ((a) shows the core damaged by phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid, (b) shows the core damaged by guar gum fracturing fluid, and (c) shows the core damaged by slickwater fracturing fluid).

Figure 9.

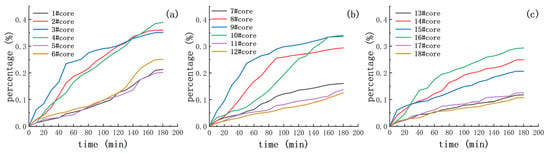

Cores #1 to #6 are presented in figures (a–f), which illustrate the permeability damage inflicted on cores by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid and the subsequent recovery following flowback simulation.

Further observation reveals that the particles have smooth surfaces and neat edges, with no significant fragmentation or sharp corners, suggesting that the phase change process was well-controlled and the formation was stable. Their uniform size and high sphericity contribute to the establishment of a stable and permeable proppant structure within porous media, effectively maintaining fluid pathways. Compared with traditional proppants, these characteristics offer potential advantages in enhancing conductivity and reducing embedment.

Additionally, the particle size distribution curves show that the dominant particle size range is concentrated within a narrow distribution, further confirming the controllability and reproducibility of the phase-change process under different core conditions. This series of morphological and structural characteristics indicates that the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid holds promising potential for improving reservoir stimulation outcomes.

Figure 5 presents front and top views of the filter cake containing self-propping particles on the core faces after flooding. The self-propping fluid underwent transition at the core face, forming a highly permeable filter cake of solid particles. The particle size distribution diagrams indicate that simulated wellbore shear in the experimental setup produced relatively uniform particles.

Microscopic observation and laser particle size analysis confirm that the phase-change fluid forms stable, uniformly sized particles under shear, resulting in proppants with excellent properties. Good sphericity ensures conductivity and minimizes flow resistance.

During the displacement process, as the temperature of the displacement equipment sleeve increased, the viscosity of the guar gum fracturing fluid gradually decreased. This allowed the fluid to penetrate into the core interior, forming a dense filter cake at the cross-sectional end, which ultimately led to a reduction in the core’s permeability. Figure 6 shows the core damaged by guar gum fracturing fluid, whose permeability is on the same order of magnitude as that of the core damaged by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid. After damage by the guar gum fracturing fluid, the cross-section of the core formed a transparent guar gum film after displacing 100 pore volumes of solution. During displacement, this film influenced permeability, causing a decline and further damaging the internal matrix of the core.

Figure 6 presents cross-sectional images of cores damaged by guar gum fracturing fluid. Subfigures (7) to (12) reveal a thin film formed by the dehydration and retention of high-molecular-weight polymer residues at 80 °C. As notably observed in subfigures (7) and (12), this film, essentially forming a filter cake, is particularly pronounced and dense within the tight cores, where it substantially reduces permeability by blocking pore throats. In contrast, for cores with relatively higher permeability, the formation and detrimental impact of such a filter cake are less significant.

Figure 7 shows the cross-sectional morphology of cores damaged by slickwater fracturing fluid. As depicted in subfigures (13) to (18), a relatively thick filter cake is formed at the core face regardless of the initial core permeability. This filter cake, composed of concentrated fine solids and residual friction reducers from the slickwater, acts as a significant flow barrier, leading to a marked reduction in core permeability and resulting in considerable formation damage.

3.2. Core Damage and Recovery Experiments of Self-Propping Proppant

Simulating the internal rock state under formation pressure, the main self-propping fluid was injected to induce particle formation. Permeability was measured after phase-change. Reverse flooding permeability was then measured to assess damage recovery. Results are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Core damage and recovery results.

The injection of self-propping agent into cores of different permeabilities caused varying degrees of permeability damage. The change in core permeability with injection time is shown in Figure 6. Key observations are as follows: (1) All cores experienced damage; permeability decreased with prolonged injection time, with the rate of decrease diminishing over time. (2) Cores with higher initial permeability suffered greater absolute permeability reduction and higher damage rates.

Figure 8 indicates that the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid offers the highest core damage recovery, outperforming guar gum fracturing fluid, with slickwater fracturing fluid showing the poorest recovery outcome.

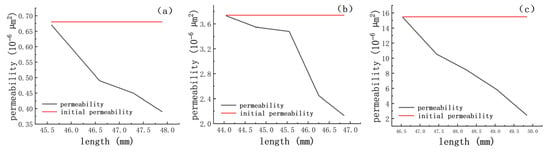

Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show the damage rate trends during the damage and recovery process for the self-propping fluid. The recovery degree for cores damaged by this fluid shows a distinct advantage over those damaged by guar gum fluid and slickwater fracturing fluid.

Figure 10.

Cores #7 to #12 are presented in figures (a–f), which illustrate the permeability damage inflicted on cores by the guar gum fracturing fluid and the subsequent recovery following flowback simulation.

Figure 11.

Cores #13 to #18 are presented in figures (a–f), which illustrate the permeability damage inflicted on cores by the slickwater fracturing fluid and the subsequent recovery following flowback simulation.

Reverse flooding of damaged cores was performed to observe permeability recovery over time. Measuring post-reverse-flooding permeability allowed characterization of the recovery behavior.

Cores with higher initial permeability exhibited greater damage rates after injection of the self-propping fluid and were more difficult to recover (lower recovery rate). Low-permeability cores showed lower damage rates and were relatively easier to recover (higher recovery rate). This indicates that the damage caused by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid has a reversible component. This offers both environmental and economic benefits while achieving reduced formation damage.

3.3. Invasion Damage Depth Experiments for Cores of Different Permeability

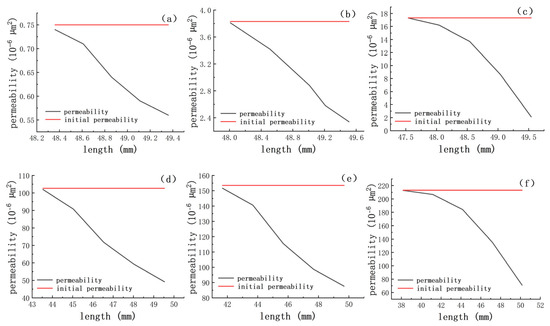

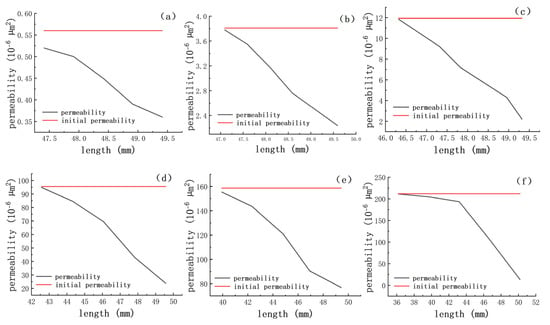

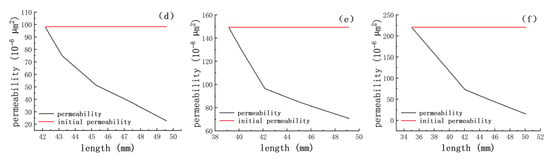

To further analyze the damage, cores were sectioned from the injection end to determine the invasion depth. Based on core tightness classification, the damage performance was evaluated.

As seen in Table 2, cores with higher permeability generally have higher porosity, and vice versa. During damage experiments, the fluid invades the internal pores of the core.

Experimental data show that cores with low, medium, and high permeability, due to their different internal structures, experience varying degrees and depths of damage during the phase-change process.

The 18 cores were divided into three groups based on permeability and damaged using the three fracturing fluids to assess their impact on invasion depth.

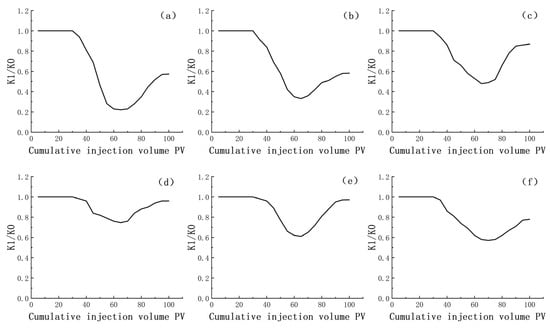

Sectioning the cores allowed observation of damage from both the liquid and solid phases of the self-propping fluid. As shown in Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, for low-permeability cores, damage depth reached up to 15 mm. For ultra-low permeability cores, damage depth was around 2 mm because the smaller pore-throats limited fluid invasion, reducing damage. For tight cores, damage was minimal (<1 mm), indicating difficulty of fluid entry. Overall, analysis of Figure 9, Figure 10 and Figure 11 indicates that higher permeability cores experience deeper fluid retention and are more susceptible to damage.

Figure 12.

Cores #1 to #6 are presented in figures (a–f), which show the invasion depth profile of the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid into the core and the corresponding permeability restoration characteristics.

Figure 13.

Cores #7 to #12 are presented in Figures (a–f), which show the invasion depth profile of the guar gum fracturing fluid into the core and the corresponding permeability restoration characteristics.

Figure 14.

Cores #13 to #18 are presented in Figures (a–f), which show the invasion depth profile of the slickwater fracturing fluid into the core and the corresponding permeability restoration characteristics.

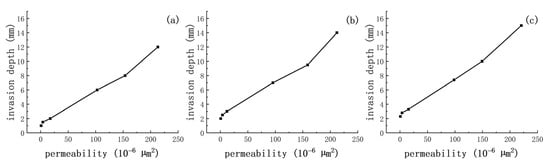

Figure 15 illustrates the relationship between damage depth and initial permeability for all 18 cores. Compared to guar gum fracturing fluid and slickwater fracturing fluid, the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid demonstrates significantly lower damage to the cores. Based on Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14, it can be observed that under the same fracturing fluid, cores with lower permeability experience less damage. The generated proppants cause almost no solid-phase damage to tight cores, indicating that this technology is suitable for fracturing operations in tight and shale oil/gas reservoirs.

Figure 15.

Relationship between fracturing fluid invasion depth and permeability ((a) shows the results using phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid, while (b) shows those using guar gum fracturing fluid, and (c) shows those using slickwater fracturing fluid).

4. Discussion

This study, through systematic core flooding experiments, elucidates the invasion damage characteristics of a phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid on cores with varying permeabilities and highlights its differences compared to two conventional fracturing fluids (guar gum fracturing fluid and slickwater). The experimental results support the initial hypothesis that the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid, by virtue of its unique working mechanism of being “injected as a liquid and transforming into solid proppants within the formation fractures,” can significantly reduce damage to the reservoir matrix. The following discussion will interpret the results, connect them with previous studies, analyze the technical advantages and underlying mechanisms, and address research limitations and future directions.

4.1. Key Findings and Mechanism Analysis

Experimental data show that the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid generally results in lower core permeability damage rates and higher recovery rates compared to guar gum and slickwater fracturing fluids. This advantage can be explained by its mechanism of action: The fluid exhibits low viscosity at room temperature, facilitating easy pumping and entry into fractures. At the simulated formation temperature (80 °C), its components undergo a phase change, forming solid particles in situ within the fractures that are uniform in size and exhibit good sphericity. These particles provide propping support within the fracture network, and crucially, their formation primarily occurs within the fracture space rather than inside the matrix pores. The solid particles formed by the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid exhibit a mean diameter of approximately 200 μm. This size range is significantly larger than the typical pore-throat dimensions of tight reservoir matrices, thereby effectively preventing particle invasion and retention within the pore network and avoiding solid-phase damage to the core. In contrast, guar gum fracturing fluid relies on high-molecular-weight polymers for viscosity, and its residues and filter cake readily plug the core face and pore throats, causing severe liquid retention and solid-phase damage. Slickwater, while having low viscosity and strong invasion capability, lacks effective proppant transport and temporary blocking capacity. Moreover, the microscopic damage it leaves after flowback is more dispersed, leading to lower recovery rates.

Invasion depth experiments further reveal that the self-propping fluid has limited invasion depth into low-permeability (especially ultra-low permeability) cores, while it invades deeper into high-permeability cores. This aligns with Darcy’s law: higher permeability facilitates greater fluid invasion. However, the key distinction lies in the fate of the invading fluid. The self-propping fluid undergoes its transformation mainly within larger pores or micro-fractures, forming particles that create a propped structure. These particles can maintain certain flow pathways even after flowback. Conversely, the liquid components and residues of guar gum and slickwater invade deeper into the pore network, causing more persistent and difficult-to-reverse damage through mechanisms like adsorption and bridging. Therefore, the advantage of the self-propping fluid is more pronounced for tight reservoirs with fine pore throats, as the risk of substantial matrix blockage by its solid products is lower.

4.2. Consistency with Existing Research and Technical Advantages

The findings of this study are consistent with recent research directions focusing on low-damage fracturing fluids and self-generating proppant technologies. Literature has indicated that limitations of conventional proppants—such as low strength, susceptibility to crushing, and transport difficulties—along with damage from polymer residues, are key constraints on fracturing effectiveness in tight reservoirs. The design concept of the phase-change self-propping fluid used in this study is in line with the phase-change propping technologies reported by researchers like Yu and Zhao, all aiming to avoid the injection of external solid proppants and associated damage. Our experimental data provide direct, comparative reservoir damage evaluation evidence for this technological pathway, addressing the relative lack of research on the damage mechanisms of self-propping fluids to the reservoir matrix.

4.3. Research Limitations and Future Directions

It is important to note that this study was conducted primarily at the laboratory core scale using homogeneous cores under constant temperature and pressure conditions. These conditions differ from real formations characterized by heterogeneity, varying temperature and pressure, multiphase flow, and complex fracture networks. Subsequent research could focus on the following directions:

First, long-term conductivity evaluation: simulating long-term formation closure pressure to evaluate the conductivity decay law of fractures filled with self-propping proppants.

Second, fluid formulation optimization: developing novel phase-change material systems tailored to different reservoir properties, enabling control over phase-change time, particle strength, and size distribution. This could involve exploring more environmentally friendly raw materials or incorporating functional nanomaterials to enhance particle performance.

5. Conclusions

Through experiments involving injection of phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid into cores of varying permeability, reverse flooding with 2% KCl, invasion depth tests, and comparison with guar gum fracturing fluid and slickwater fracturing fluid, the damage extent of the self-propping fluid was summarized. The recovery characteristics after reverse flooding and sectioning were analyzed. The main conclusions are as follows:

First, cores with higher permeability and porosity experience greater damage. Due to their internal pore structure, the viscous self-propping fluid invades the core, causing damage. The difference in damage impact between the two fluids is approximately 5%, with the self-propping fluid performing better. The guar gum fracturing fluid and slickwater fracturing fluid form a filter cake that plugs the core face, causing a rapid permeability decline. Recovery degree is closely related to permeability. Higher permeability/porosity cores have lower recovery rates. Under constant-rate reverse flooding simulating flowback, cores with higher initial permeability recovered less effectively than those with lower initial permeability. The highest-permeability core had a recovery rate of 12.6%, while lower-permeability cores achieved recovery rates exceeding 40%.

Second, compared to guar gum fracturing fluid and slickwater, the phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid exhibits higher viscosity, which effectively limits its invasion into the core matrix and reduces the risk of pore-throat blockage. Moreover, the solid particles formed after the phase change demonstrate favorable permeability characteristics, with uniform particle size distribution contributing to stabilized flow conductivity. In contrast, both guar gum fracturing fluid and slickwater tend to form a continuous thin film at the core interface, which hinders fluid flow and significantly impairs permeability.

Third, the extent of core damage was influenced by the distinct filter-cake morphologies of the different fracturing fluids. The guar gum and slickwater fluids created a dense, continuous film that acted as a barrier, thereby reducing core permeability. Conversely, the phase-change self-propping fluid formed a porous pack of uniformly distributed particles (mean diameter: 200 μm). This structure provided effective proppant support while ensuring favorable fluid permeability. Through damage and recovery experiments on cores with different permeabilities, this study demonstrates the suitability of phase-change self-propping fracturing fluid for tight reservoir applications. It clarifies the engineering conditions for its use and provides an effective experimental and analytical methodology for evaluating formation damage during fracturing. Future applications can be explored in the development of tight and shale oil/gas reservoirs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and Methodology, Y.P.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T. and J.Z.; data curation, L.Z., X.S. and W.T.; writing—review and editing, F.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This paper is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12272350).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yuxin Pei was employed by KeShengGao Energy Technology (Changzhou) Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Donghe, Y.; Weiyu, C.; Guohua, L.; Zhao, L.; Jia, Y.; Xu, K.; Zhang, N. Preparation and Performance Evaluation of Supramolecular Phase Change Fracturing Fluid with Thermal Stimuli-response. Oilfield Chem. 2021, 38, 223–229. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Ji, C.; Zhao, B.; Li, J.; Luo, P.; Fang, H. Research of temperature-responsive subsurface self-generated proppant. Pet. Drill. Tech. 2022, 50, 45–51. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Bian, C.; Zhang, J.; Fu, X.; Xu, M.; Yin, J.; Bismark, O.; Song, Y.; Ren, X.; Zhong, Y. Development of self-generated proppants with accelerated growth speed based on the investigation of the nano-fillers. Mater. Today Commun. 2025, 45, 112190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, N.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Yu, D.; Liu, P.; Chen, W.; Liu, G.; Du, J.; Li, N. Laboratory study and field application of self-propping phase-transition fracturing technology. Nat. Gas Ind. 2020, 40, 60–67. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Yu, D.; Zhao, L.; Liu, G.; Zhang, N.; Jia, Y.; Xu, K. Optimization of Phase-transition in-situ Generated Solid-phase Chemical Fracturing Stimulation. Drill. Prod. Technol. 2021, 44, 64. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.J.; Zhang, B.H.; Li, Z.H. Study on the law of imbibition damage in the whole process of tight gas fracturing fluid and reservoir. J. Yangtze Univ. 2022, 19, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.T.; Cui, L.; Cheng, F.; Guan, B.S.; Liang, L. Computed Tomography Technology for Fracturing Fluid Damage. Nondestruct. Test. 2019, 41, 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, J.; Xu, K.; Yi, X.-B.; Liu, C.; Lai, J.L.; Wang, T.Y. Research progress on the fracturing fluid damage mechanism on shale reservoir. Appl. Chem. Ind. 2023, 52, 2920–2923. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, W.; Ning, C.; Huang, K. Current Situation and Prospect of Research on Coalbed Methane Fracturing Fluid. China Coalbed Methane 2023, 20, 30–35. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L.; Zhang, S.; Ma, X. Characteristics of Damage of Guar Fracturing Fluid to Reservoir Permeability. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2016, 37, 456–459. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.; Ren, X. Damage characteristics of fracturing fluid in tight gas reservoir and analysis of experimental factors. Petrochem. Ind. Appl. 2017, 1673–5285. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J. Preparation of Self-generated Proppant and Study of Phase Transition and Growth Process. Master’s Thesis, Southwest University of Science and Technology, Mianyang, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, N.; Liu, F.; Jiang, L.; Luo, Z.; Ju, Y.; Liu, P.; Zhao, L.; Pei, Y. Effects of phase-transition heat on fracture temperature in self-propping phase-transition fracturing technology. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2024, 51, 1374–1383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, H.; Li, G.; Ning, K.; Wang, X.; He, N. Current status and prospect of fracturing fluid damage in tight reservoirs. Petrochem. Ind. Appl. 2023, 42, 7–10+32. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Guo, J.-C.; Wang, S.-B.; Zhao, F.; He, Y. Research status and development trend of low-damage fracturing fluid. Mod. Chem. Ind. 2018, 38, 20–22+24. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Bao, H. Mechanism of action and development prospect of proppant in oil fracturing. Chem. Eng. 2019, 33, 20190870. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhamid, M.S.; Marouf, M.; Kamal, Y.; Shaaban, A.; Mathur, A.; Yosry, M.; Kraemer, C. Field Development Study: Channel Fracturing Technique Combined with Rod-shaped Proppant Improves Production, Eliminates Proppant Flowback Issues and Screen-outs in the Western Desert, Egypt. In Proceedings of the North Africa Technical Conference and Exhibition, Cairo, Egypt, 15–17 April 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Jin, Y.; Shi, A.; Xu, Q. Review and prospect of fracturing proppant development. Pet. Sci. Bull. 2023, 3, 330–346. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.-S.; Wang, W.B.; Yang, D.Y.; Liao, J.; Zhang, H.L.; Wang, L.-B.; Wang, H.-J. Application and Development of Massive Hydraulic Fracturing Technology in China. Liaoning Chem. Ind. 2012, 41, 46–50. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Z.; Li, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, C.; Adenutsi, C.D. Experimental study on microscopic formation damage of low permeability reservoir caused by HPG fracturing fluid. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2016, 36, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazin, B.; Bekri, S.; Vizika, O.; Herzhaft, B.; Aubry, E. Fracturing in Tight Gas Reservoirs: Application of Special-Core-Analysis Methods to Investigate Formation-Damage Mechanisms. SPE J. 2010, 15, 975–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Zhang, S.; Guan, H.; Liu, Y.; Guan, B.; Zhang, F.; Cui, W. Relationship between characteristics of tight oil reservoirs and fracturing fluid damage: A case from Chang 7 Member of the Triassic Yanchang Fm in Ordos Basin. Oil Gas Geol. 2015, 36, 848–854. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, L.; Xing, X.; Lan, X.-T.; Li, N.-Y.; Luo, Z.-F. Characteristics of Formation Damage by Guar-Gum Fracturing Fluids. Oilfield Chem. 2014, 31, 334–338. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Liu, B.; Fang, X.; Yan, J.; Lin, Y. Experimental study on fracturing damage in low permeability tight gas reservoir. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2009, 16, 81–82+104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Li, L.; He, Q.; Luo, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G. Discussion on damage mechanism of fracturing fluid in tight sandstone reservoir. Fault-Block Oil Gas Field 2013, 20, 639–643. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Wang, W.; Zhao, B.; Dui, A.; Cai, S.; Chen, L. Experimental Research on Damage of Hydroxypropylguar Gum Fracturing Fluid Filter Cake on Cores. Drill. Prod. Technol 2018, 41, 92–94+101+7. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, H.; Tang, H.; He, J.; Zhao, F.; Zhang, L.; Liao, J.; Wang, Q.; Yuan, X. Damage mechanism of water-based fracturing fluid to tight sandstone gas reservoirs: Improvement of The Evaluation Measurement for Properties of Water-based Fracturing Fluid: SY/T 5107-2016. Nat. Gas Ind. B 2021, 8, 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, H.; Zhu, Q. Experimental Study on the Damage Caused by Thickener of Guanidine Gum of Low Permeability Sandstone Gas Reservoir. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2015, 15, 24–28. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Radwan, A.E. Reservoir formation damage analysis application on oil reservoirs: A case study from the Gulf of Suez, Egypt. In Proceedings of the Offshore Mediterranean Conference and Exhibition, Ravenna, Italy, 28–30 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Civan, F. Reservoir Formation Damage: Fundamentals, Modeling, Assessment, and Mitigation; Gulf Professional Publishing: Houston, TX, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Nath, F.; Garcilazo, R., Jr.; Collazo, J., Jr. Optimizing Hydraulic Fracturing in Water-Sensitive Shales: A Comparative Study of Frac Fluid Performance. In Proceedings of the SPE/AAPG/SEG Unconventional Resources Technology Conference, Houston, TX, USA, 9–11 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Chang, C.; Hai, K.; Huang, H.; Li, H. A review of experimental studies on the proppant settling in hydraulic fractures. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoveidavianpoor, M.; Gharibi, A.; bin Jaafar, M.Z. Experimental characterization of a new high-strength ultra-lightweight composite proppant derived from renewable resources. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 170, 1038–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.