MSHI-Mamba: A Multi-Stage Hierarchical Interaction Model for 3D Point Clouds Based on Mamba

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

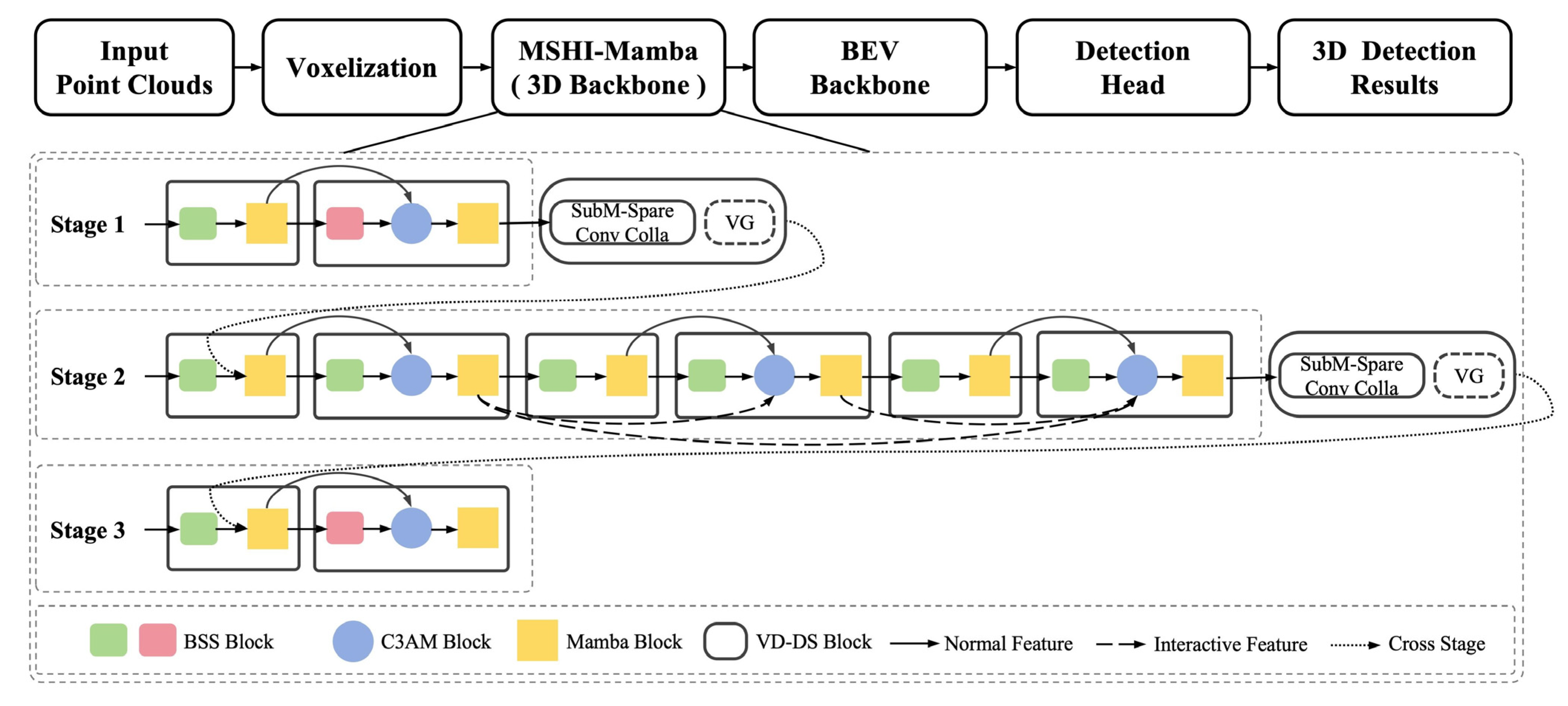

- We propose MSHI-Mamba, a Mamba-based multi-stage hierarchical interaction architecture for 3D voxels, which enables the interactive fusion of feature information across layers and stages.

- (2)

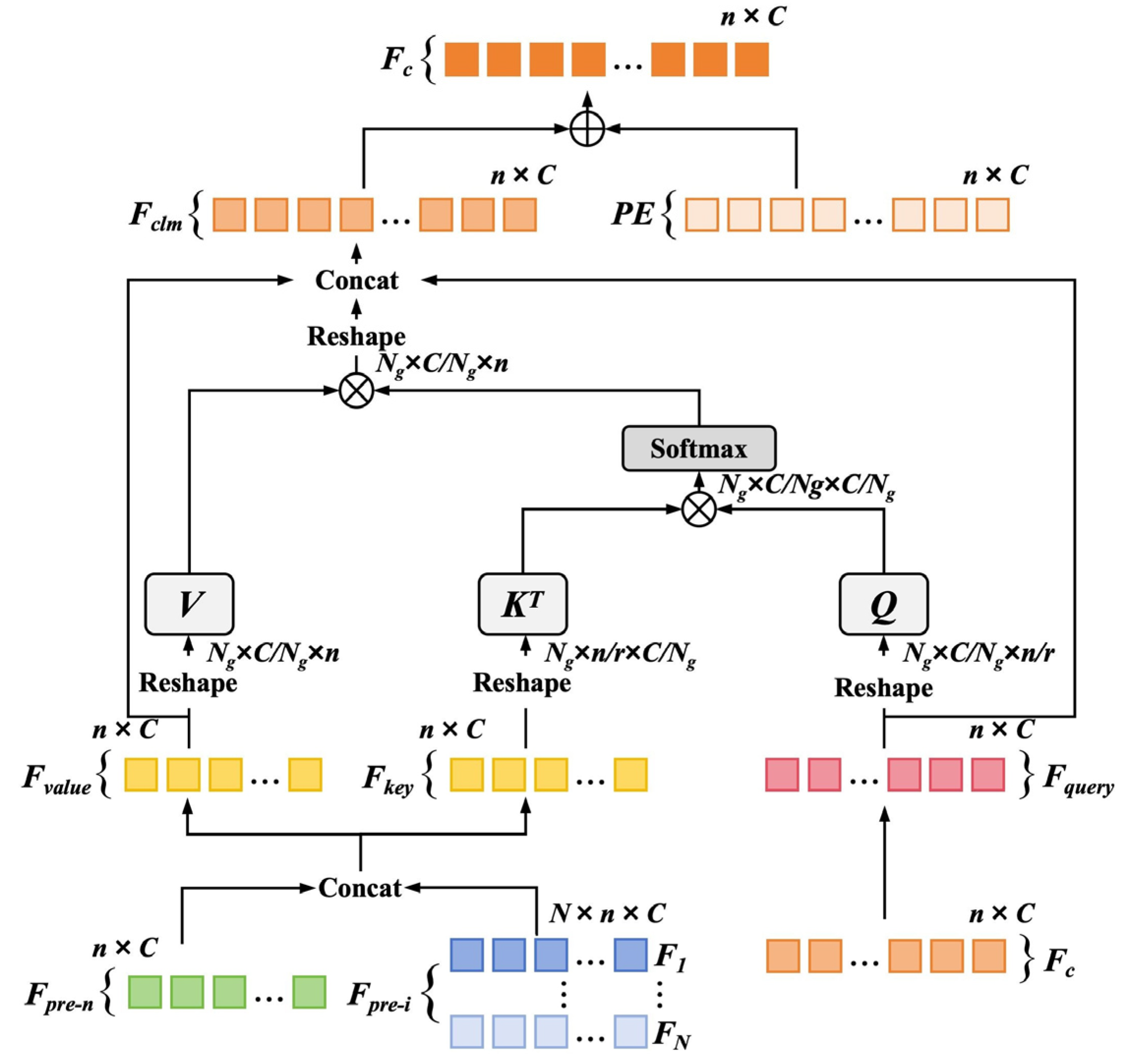

- We define a cross-layer complementary cross-attention mechanism, enhancing feature complementarity between layers, reducing information redundancy, and further improving the network’s cross-layer representation capabilities.

- (3)

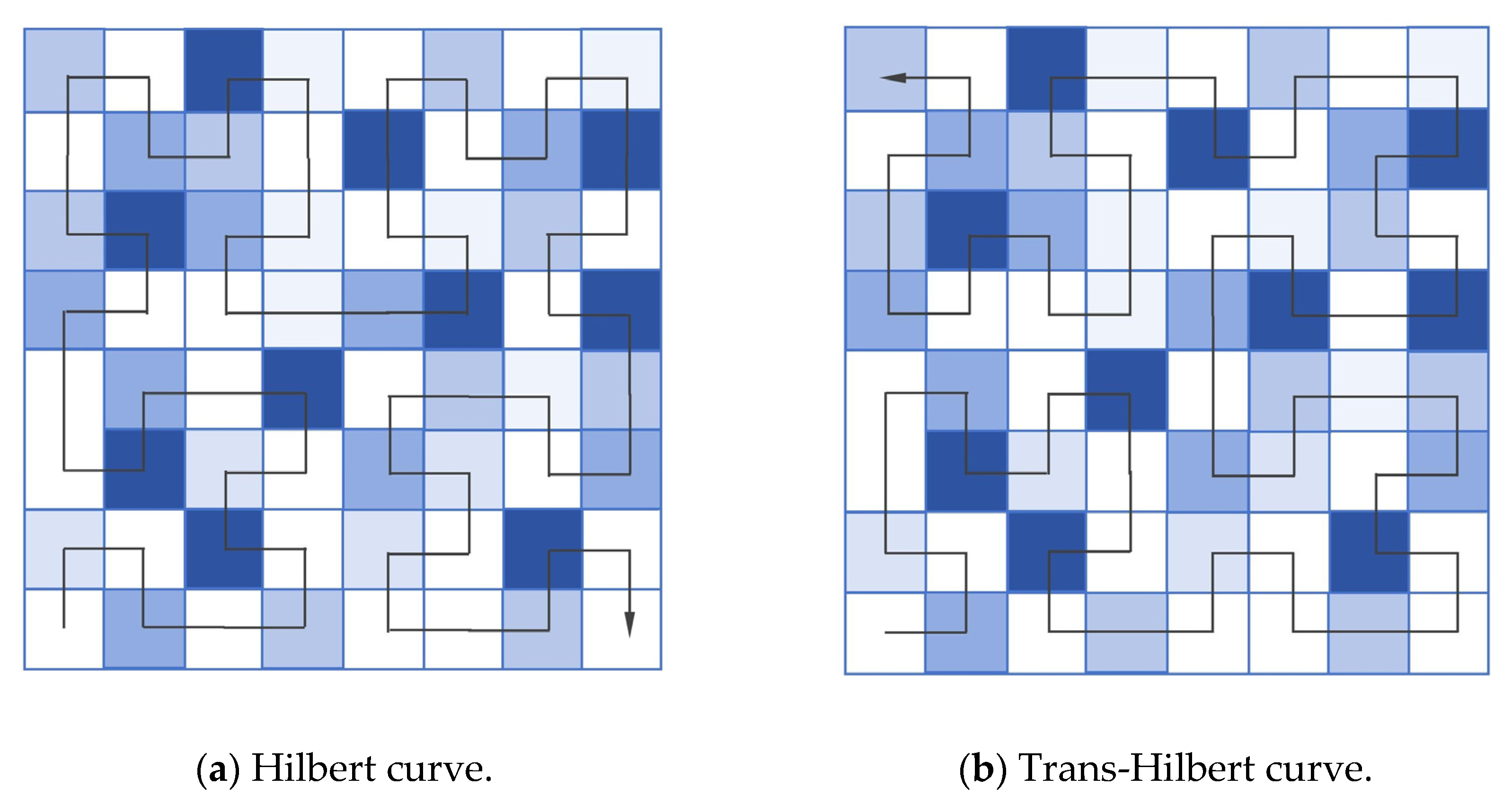

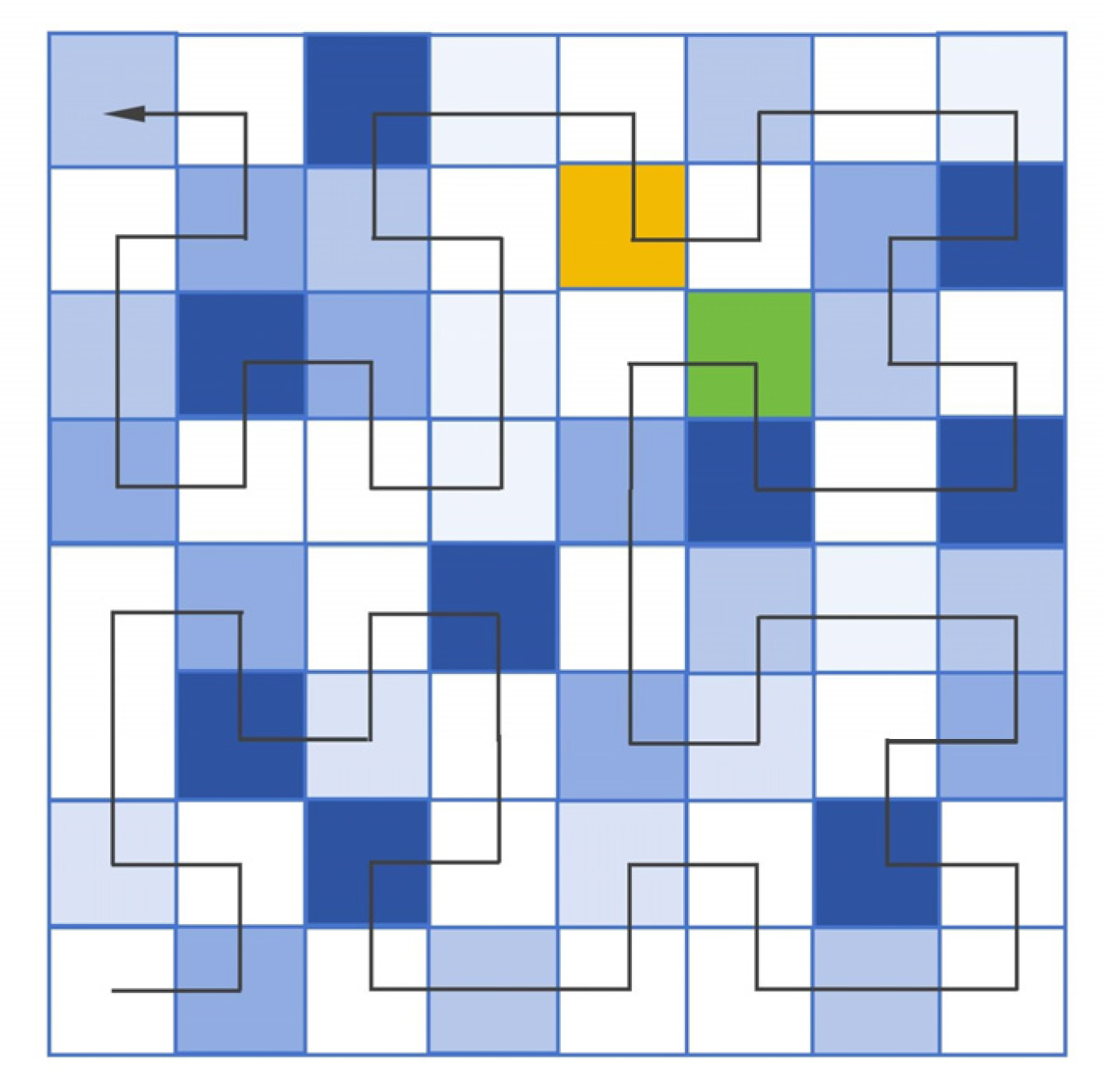

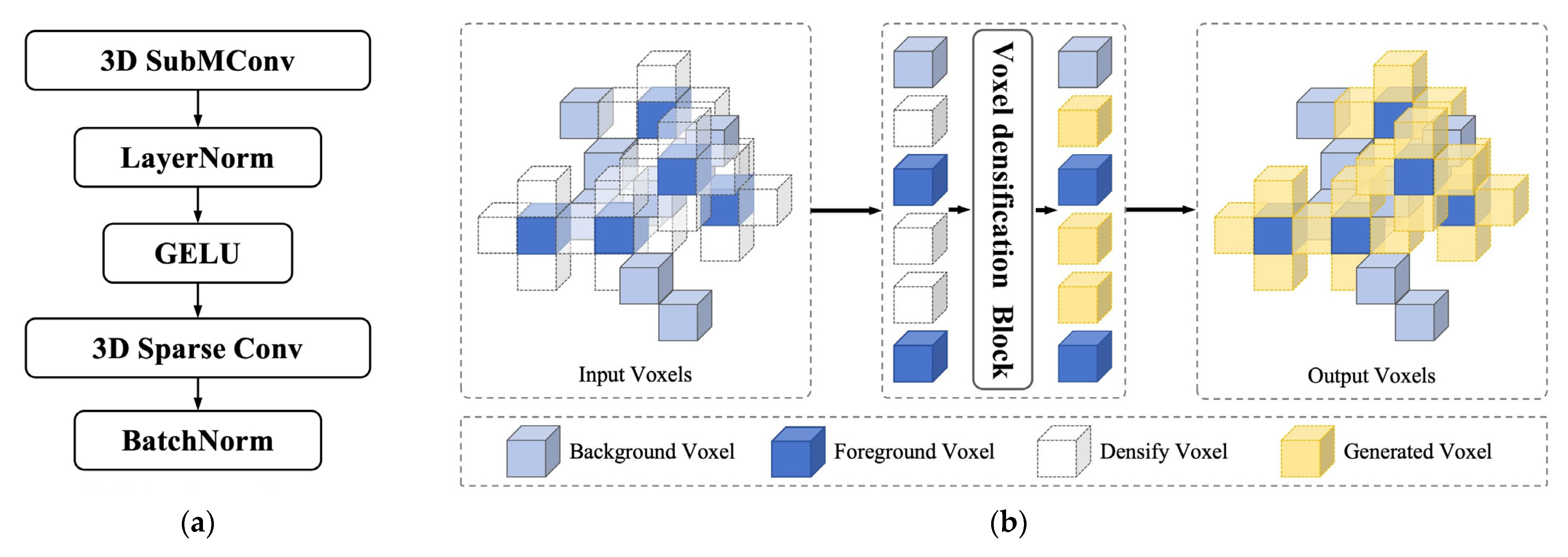

- To mitigate spatial proximity loss caused by voxel serialization and expand the model’s perception range, we propose a bi-shift scanning strategy and voxel densification downsampling. These enhance local spatial information, selectively generate key foreground voxels, and enable cross-regional spatial information perception.

- (4)

- Our experimental results demonstrate the effectiveness of the proposed approach. On the KITTI dataset, MSHI-Mamba achieves a 4.2% improvement in the mAP compared to the baseline method. Competitive performance is also observed on the nuScenes dataset.

2. Related Work

2.1. Three-Dimensional Object Detection Based on Point Clouds

2.2. Three-Dimensional Point Cloud Transformers

2.3. State Space Models and Space-Filling Curves

3. Method

3.1. Multi-Stage Hierarchical Interaction Architecture (MSHI)

3.2. Cross-Layer Complementary Cross-Attention

3.3. Bi-Shift Scanning Strategy

3.4. Voxel Densification Downsampling

4. Experiments

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Indicators

4.2. Implementation Details

4.3. Main Results

4.3.1. Three-Dimensional Detection Results

4.3.2. Inference Efficiency

4.4. Ablation Study

4.4.1. Ablation Study of Cross-Layer Complementary Cross-Attention (C3AM)

4.4.2. Ablation Study of Bi-Shift Scanning Strategy (BSS)

4.4.3. Ablation Study of Voxel Densification Downsampling

4.5. Limitations and Assumptions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Liu, B.; Wang, M.; Foroosh, H.; Tappen, M.; Penksy, M. Sparse convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 806–814. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Q.; Zhong, Y.; Neumann, U. Behind the curtain: Learning occluded shapes for 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 28 February–1 March 2022; pp. 2893–2901. [Google Scholar]

- Deng, J.; Shi, S.; Li, P.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, Y.; Li, H. Voxel R-CNN: Towards high performance voxel-based 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence (AAAI), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2–9 February 2021; pp. 1201–1209. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.; Guo, C.; Jiang, L.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Li, H. PV-RCNN: Point-voxel feature set abstraction for 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10529–10538. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Qi, X.; Jia, J. Voxelnext: Fully sparse voxelnet for 3D object detection and tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 21674–21683. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Kuai, T.; Waslander, S. Point density-aware voxels for lidar 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 8469–8478. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.; Jiang, L.; Jia, J.; Torr, P.; Koltun, V. Point transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 16259–16268. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, J.; Xue, Y.; Niu, M.; Bai, H.; Feng, J.; Liang, X.; Xu, H.; Xu, C. Voxel transformer for 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3164–3173. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Shi, C.; Shi, S.; Lei, M.; Wang, S.; He, D.; Schiele, B.; Wang, L. DSVT: Dynamic sparse voxel transformer with rotated sets. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 13520–13529. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Tang, H.; Yang, S.; Han, S. FlatFormer: Flattened window attention for efficient point cloud transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 1200–1211. [Google Scholar]

- He, C.; Li, R.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, L. Scatterformer: Efficient voxel transformer with scattered linear attention. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 74–92. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, D.; Zhou, X.; Xu, W.; Zhu, X.; Zou, Z.; Ye, X.; Tan, X.; Bai, X. PointMamba: A simple state space model for point cloud analysis. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.; Tang, L.; Rao, Y.; Huang, T.; Zhou, J.; Lu, J. Point-BERT: Pre-training 3D point cloud transformers with masked point modeling. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 19313–19322. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Dao, T.; Ermon, S.; Rudra, A.; Re, C. Hippo: Recurrent memory with optimal polynomial projections. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2020, Virtual, 6–12 December 2020; pp. 1474–1487. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, A.; Johnson, I.; Goel, K.; Saab, K.; Dao, T.; Rudra, A.; Ré, C. Combining recurrent, convolutional, and continuous-time models with linear state space layers. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2021, Virtual, 6–14 December 2021; pp. 572–585. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Jiao, J.; Liu, Y. VMamba: Visual state space model. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 103031–103063. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model. In Proceedings of the 41st International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), Vienna, Austria, 21–27 July 2024; pp. 62429–62442. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, W.; Zhu, H.; Lin, S.; Luo, X.; Shen, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, G.; Zhang, B. Fusion-mamba for cross-modality object detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 7392–7406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrouz, A.; Santacatterina, M.; Zabih, R. Mambamixer: Efficient selective state space models with dual token and channel selection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.; Li, J.; Dai, T.; Ouyang, Z.; Ren, X.; Xia, S. MambaIR: A simple baseline for image restoration with state-space model. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 222–241. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Bian, K.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, P.; An, W.; Zhou, J.; Shao, K. Vim-F: Visual state space model benefiting from learning in the frequency domain. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.18679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Fan, L.; He, C.; Lei, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, L. Voxel mamba: Group-free state space models for point cloud based 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024; pp. 81489–81509. [Google Scholar]

- Han, X.; Tang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, X. Mamba3D: Enhancing local features for 3D point cloud analysis via state space model. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 4995–5004. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, S.; Wang, X.; Li, H. PointRCNN: 3D object proposal generation and detection from point cloud. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 770–779. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Sun, Y.; Liu, S.; Jia, J. 3DSSD: Point-based 3D single stage object detector. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition(CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11040–11048. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, W.; Rajkumar, R. Point-GNN: Graph neural network for 3D object detection in a point cloud. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition(CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 1711–1719. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, C.; Yi, L.; Su, H.; Guibas, L. Pointnet++: Deep hierarchical feature learning on point sets in a metric space. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2017, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, R.; Lai, X.; Li, X. BADet: Boundary-aware 3D object detection from point clouds. Pattern Recognit. 2022, 125, 108524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Cai, S.; Liu, Y.; Deng, B.; Huang, J.; Hua, X.; Zhao, M. Improving 3D object detection with channel-wise transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 2743–2752. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Y.; Wang, W.; Tay, F.; Liu, W.; Tian, Y.; Yuan, L. Masked autoencoders for point cloud self-supervised learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; pp. 604–621. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P. OctFormer: Octree-based transformers for 3D point clouds. ACM Trans. Graph. 2023, 42, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Chen, Y.; Tian, H.; Tao, C.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, G.; Li, H.; Qiao, Y.; Lu, L.; et al. BEVformer v2: Adapting modern image backbones to bird’seye-view recognition via perspective supervision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 17830–17839. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Xia, C.; Lv, F.; Shi, Y. RT-DETRv3: Real-time End-to-End Object Detection with Hierarchical Dense Positive Supervision. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Tucson, AZ, USA, 26 February–6 March 2025; pp. 1628–1636. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Ma, W.; Lv, F.; Shi, Y. 3D Object Detection Based on Multilayer Multimodal Fusion. Acta Electron. Sin. 2024, 52, 696–708. [Google Scholar]

- Lang, A.; Vora, S.; Caesar, H.; Zhou, L.; Yang, J.; Beijbom, O. Pointpillars: Fast encoders for object detection from point clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 12697–12705. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Jiang, L.; Wang, P.; Liu, Z.; Liu, X.; Qiao, Y.; Ouyang, W.; He, T.; Zhao, H. Point transformer v3: Simpler faster stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 4840–4851. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, O.; Torun, H.; Swaminathan, M. HilbertNet: A probabilistic machine learning framework for frequency response extrapolation of electromagnetic structures. IEEE Trans. Electromagn. Compat. 2024, 64, 405–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Wang, M.; Yang, Y.; Yu, K.; Yuan, L.; Yue, Y. Pointgpt: Auto-regressively generative pre-training from point clouds. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2023, 36, 29667–29679. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, M.; Fu, Y.; Yu, Y. SparX: A Sparse Cross-Layer Connection Mechanism for Hierarchical Vision Mamba and Transformer Networks. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 19104–19114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. Pyramid vision transformer: A versatile backbone for dense prediction without convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 568–578. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Xie, E.; Li, X.; Fan, D.; Song, K.; Liang, D.; Lu, T.; Luo, P.; Shao, L. PVT v2: Improved baselines with pyramid vision transformer. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 415–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, A.; Lenz, P.; Stiller, C.; Urtasun, R. Vision meets robotics: The kitti dataset. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2013, 32, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesar, H.; Bankiti, V.; Lang, A.; Vora, S.; Liong, V.; Xu, Q.; Krishnan, A.; Pan, Y.; Baldan, G.; Beijbom, O. nuScenes: A multimodal dataset for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11621–11631. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, T.; Zhou, X.; Krähenbühl, P. CenterPoint: Center-based 3D Object Detection and Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 10–25 June 2021; pp. 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Tuzel, O. Voxelnet: End-to-end learning for point cloud based 3D object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4490–4499. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Y.; Mao, Y.; Li, B. Second: Sparsely embedded convolutional detection. Sensors 2018, 18, 3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zhao, X.; Huang, T.; Hu, R.; Zhou, Y.; Bai, X. Tanet: Robust 3D object detection from point clouds with triple attention. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 11677–11684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Wang, Z.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Li, H. From points to parts: 3D object detection from point cloud with part-aware and part-aggregation network. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 43, 2647–2664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Jiang, L.; Deng, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, C.; Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Li, H. PV-RCNN++: Point-voxel feature set abstraction with local vector representation for 3D object detection. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2023, 131, 531–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Pang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H.; Wang, F.; Wang, N.; Zhang, Z. Embracing single stride 3D object detector with sparse transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 8458–8468. [Google Scholar]

| Model | Car | Pedestrian | Cyclist | mAP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Med. | Hard | Easy | Med. | Hard | Easy | Med. | Hard | ||

| VoxelNet [45] | 77.5 | 65.1 | 57.7 | 39.5 | 33.7 | 31.5 | 61.2 | 48.4 | 44.4 | 51.0 |

| SECOND [46] | 83.1 | 73.7 | 66.2 | 51.1 | 42.6 | 37.3 | 70.5 | 53.9 | 46.9 | 58.4 |

| PointPillars [35] | 79.1 | 75.0 | 68.3 | 52.1 | 43.5 | 41.5 | 75.8 | 59.1 | 52.9 | 60.8 |

| PointRCNN [24] | 85.9 | 75.8 | 68.3 | 49.4 | 41.8 | 38.6 | 73.9 | 59.6 | 53.6 | 60.8 |

| TANet [47] | 83.8 | 75.4 | 67.7 | 54.9 | 46.7 | 42.4 | 73.8 | 59.9 | 53.3 | 62.0 |

| Flatformer * [10] | 86.5 | 75.6 | 74.1 | 54.4 | 48.2 | 43.3 | 80.6 | 62.9 | 61.1 | 65.2 |

| DSVT-Voxel * [9] | 86.4 | 77.8 | 75.8 | 60.8 | 55.4 | 52.1 | 85.1 | 66.8 | 63.9 | 69.3 |

| MSHI-Mamba (Baseline) | 83.8 | 74.8 | 73.5 | 54.2 | 47.3 | 43.3 | 82.6 | 62.9 | 59.7 | 64.7 |

| MSHI-Mamba (Ours) | 88.9 | 78.2 | 75.9 | 61.1 | 50.8 | 46.8 | 86.4 | 67.2 | 63.6 | 68.9 |

| Model | mAP | NDS |

|---|---|---|

| PointPillars [35] | 30.5 | 45.3 |

| 3DSSD [25] | 42.6 | 56.4 |

| CenterPoint [44] | 58.0 | 65.5 |

| Voxel Mamba [22] | 69.0 | 73.0 |

| DSVT [9] | 68.4 | 72.7 |

| MSHI-Mamba (Ours) | 59.3 | 67.7 |

| Model | Backbone | Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|

| Part-A2 [48] | SpCNN | 2.9 |

| PV-RCNN++ [49] | 17.2 | |

| SST [50] | Transformers | 6.8 |

| DSVT-Voxel [9] | 4.2 | |

| Voxel Mamba [22] | SSMs | 3.7 |

| MSHI-Mamba (Ours) | 4.3 |

| Model | FPS |

|---|---|

| PointRCNN [24] | 10.0 |

| PV-RCNN [4] | 8.9 |

| SECOND [46] | 30.4 |

| TANet [47] | 28.7 |

| PointPillars [35] | 42.4 |

| MSHI-Mamba (Ours) | 10.7 |

| Model | C3AM | Car | Pedestrian | Cyclist | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CSI | IML | Easy | Med. | Hard | mAP | Med. | Med. | |

| Baseline | ✗ | ✗ | 83.8 | 74.8 | 73.5 | 77.3 | 47.3 | 62.6 |

| MSHI-Mamba | √ | N = 1 | 86.6 | 76.9 | 74.4 | 79.3 | 48.5 | 64.9 |

| √ | N = 2 | 87.5 | 77.2 | 74.7 | 79.8 | 48.8 | 65.8 | |

| √ | N = 3 | 86.7 | 77.0 | 74.6 | 79.4 | 48.1 | 65.2 | |

| ✗ | N = 2 | 85.8 | 76.1 | 74.2 | 78.7 | 47.6 | 64.7 | |

| Model | BSS | Car | Pedestrian | Cyclist | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Med. | Hard | mAP | Med. | Mod. | ||

| Baseline | ✗ | 83.8 | 74.8 | 73.5 | 77.3 | 47.3 | 62.6 |

| MSHI-Mamba | √ | 86.8 | 77.2 | 74.2 | 79.4 | 48.4 | 65.7 |

| Model | C3AM | BSS | VD-DS | Car | Pedestrian | Cyclist | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Easy | Med. | Hard | mAP | Med. | Med. | ||||

| Baseline | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | 83.8 | 74.8 | 73.5 | 77.3 | 47.3 | 62.6 |

| MSHI-Mamba | √ | ✗ | ✗ | 86.8 | 77.2 | 74.2 | 79.4 | 48.4 | 65.7 |

| √ | √ | ✗ | 87.4 | 77.9 | 75.1 | 80.2 | 49.9 | 66.1 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 88.9 | 78.2 | 75.9 | 81.0 | 50.8 | 67.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhou, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhou, X. MSHI-Mamba: A Multi-Stage Hierarchical Interaction Model for 3D Point Clouds Based on Mamba. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 1189. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031189

Zhou Z, Wang Q, Zhou X. MSHI-Mamba: A Multi-Stage Hierarchical Interaction Model for 3D Point Clouds Based on Mamba. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(3):1189. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031189

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Zhiguo, Qian Wang, and Xuehua Zhou. 2026. "MSHI-Mamba: A Multi-Stage Hierarchical Interaction Model for 3D Point Clouds Based on Mamba" Applied Sciences 16, no. 3: 1189. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031189

APA StyleZhou, Z., Wang, Q., & Zhou, X. (2026). MSHI-Mamba: A Multi-Stage Hierarchical Interaction Model for 3D Point Clouds Based on Mamba. Applied Sciences, 16(3), 1189. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16031189