Abstract

This work focuses on testing and validating a prototype device for measuring mass transfer phenomena in biomass drying processes, patented by the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) and Escuela Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL), WO2025/109237 A1. The first step involved evaluating and calibrating the sensors of the measuring device to ensure accurate and consistent measurements. Subsequently, extensive tests were conducted to validate the prototype’s functionality for obtaining mass diffusivity and the mass transfer coefficient by convection at the solid-air interface. Finally, the results obtained were compared with those provided by existing predictive theoretical models in the literature. Areas for improvement in the theoretical models were identified, and adjustments were made to optimize prediction. The study highlights that the theoretical Sherwood method for estimating the mass transfer coefficient shows discrepancies with experimental data, mainly due to the assumption that the transfer coefficient remains constant during drying, whereas it actually varies with the material’s moisture content. This leads to inaccuracies that affect the efficiency of industrial drying systems. The prototype proved effective in measuring both diffusivity and mass transfer coefficient, validating the method.

1. Introduction to Mass Transfer Models Applied to Drying

When biomass is used as a biofuel, the most important parameters to consider are calorific value, flammability, and density. Calorific value refers to the amount of energy generated per unit of weight (kJ/kg in the SI system). These parameters are closely related to the moisture content of the material to be combusted, making moisture reduction a crucial step in obtaining high-quality solid biofuels [1,2].

One of the most commonly used techniques for achieving rapid biomass drying is the application of a forced hot air stream, which involves both heat convection and mass convection processes. This system significantly reduces drying times [3,4]. Other drying techniques include radiation through visible light, microwaves, or infrared [5,6], as well as vacuum drying [7].

In convective drying processes, there is uncertainty regarding the rate at which water is removed from biomass and, consequently, the drying time under specific conditions. This is influenced by various factors such as air velocity and direction, temperature, relative humidity, particle size, material porosity, pore size, physical barriers like bark, and the physical and chemical structure of the material [4,8]. Several models in the literature attempt to predict the amount of water removed by diffusion and convection [9].

Mass diffusion refers to the random movement of particles from regions of high concentration to regions of low concentration until equilibrium is reached, resulting in a uniform concentration throughout the system. This process occurs due to the natural tendency of particles to distribute evenly within a medium. On the other hand, mass transfer by convection involves the movement of particles from a surface to a fluid in contact with it. This process is influenced by both diffusion and the movement of the fluid over the surface. Convection can be natural (caused by density differences within the fluid) or forced (induced by an external force, such as mechanical agitation or fluid flow over a surface). Particle movement at the surface interface is accelerated by the drag effect of impulsive forces, meaning that convection significantly speeds up the mass transfer process compared to pure diffusion. This is especially relevant in systems where mass transport is a limiting factor in reaction or diffusion rates [10,11].

The amount of water desorbed by diffusion at the solid-air interface is usually modeled according to Fick’s Equation (1), where is the amount of water removed from the solid per unit of time (g water/s); is the diffusivity of water at the solid-air interface (m2/s); is the transfer surface (m2); is the air density (g air/m3); and is the absolute humidity gradient of the air in the -direction, perpendicular to the transfer surface (g water/g air·m).

Fick’s law can be expressed in relative terms, so that represents the amount of water desorbed per unit of time and mass of the solid (g water/s·g solid), and the diffusivity is expressed as with units (m2/s·g solid).

The drying speed by convection follows Newton’s law of mass transfer (3), where is the amount of water removed from the solid per unit of time (g water/s); is the mass transfer coefficient of water by convection at the solid-air interface (m/s); A is the transfer surface (m2); is the air density (g air/m3); is the absolute humidity of the airflow (g water/g air); and is the absolute humidity of saturated air at the solid-air interface (g water/g air).

According to Sahoo et al. (2022) [12] or Gandía et al. (2024) [9], the main scientific challenge is obtaining accurate values of and , as there is generally little literature providing values for these coefficients. Most researchers must estimate them, as no standardized measurement method exists. It is important to note that determining the diffusivity coefficient in a drying process is challenging due to the complexity of the phenomena involved and the factors that affect its calculation. As a critical parameter for understanding moisture transfer behavior in materials, its estimation is subject to several complications. First, the factors that affect mass diffusivity are numerous. These include the following:

- Airflow conditions: Differences in air velocity and temperature can directly affect the mass transfer rate. Warm air typically promotes greater transfer due to its ability to increase the kinetic energy of water molecules, thus facilitating evaporation.

- Relative humidity: Air’s capacity to absorb water vapor is limited, and this affects diffusivity, as high relative humidity can reduce the efficiency of mass transfer.

- Properties of the material being dried: Porosity, internal structure, and composition of the medium play a fundamental role in the resistance to moisture flow within the material. In the case of porous materials, for example, diffusivity can be higher due to the greater connectivity of the pores, while in denser, less porous materials, diffusion is more limited.

- The phase of the medium: As the material transitions from a wetter to a drier phase during the drying process, mass diffusivity varies. In the desorption phase, when the material is partially dry, diffusivity tends to be higher due to the greater availability of water on the surfaces. In the final drying phase, where water is more trapped within the material’s pores, diffusivity decreases considerably, making it difficult to estimate accurately.

In the experiments conducted, the convective mass transfer coefficients differed considerably from the theoretical value estimated by the Sherwood method. This discrepancy could be related to the nonlinear nature of the drying process. The observed behavior reflects how air conditions and the physical properties of the medium affect diffusivity and mass transfer in complex ways. The observed differences suggest that existing models may require further adjustments to more accurately reflect experimental conditions.

Determining the diffusivity coefficient is a complex task due to the numerous factors that affect its value, including material properties, environmental conditions, and the phase of the medium in the drying process. The observed differences between experimental and theoretical values reinforce the need to consider these factors in future studies, which will improve the accuracy of mass transfer models. Comparative analyses between experimental and theoretical values enrich the interpretation of the results [13].

The prediction of drying rates using mass transfer models presents many limitations and, in practical applications, is not sufficiently accurate. Numerous studies demonstrate that both diffusivity and the convective mass transfer coefficient of water are not constant during a drying process but rather depend on the material’s moisture content [10,14].

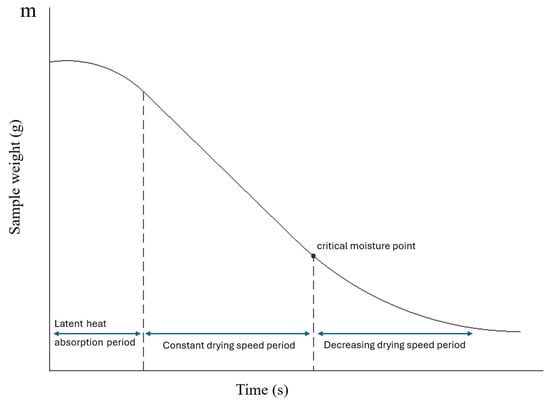

From a kinetic perspective, it is clear that convection dries at a higher rate when the material’s moisture content is high. Modifying the constants in mass transfer models causes variations in the evaporation flux. The kinetics of drying processes can be evaluated through the analysis of drying curves, which show the relationship between biomass moisture content and time. These experimentally obtained curves typically exhibit a decreasing trend with a variable slope and often display an inverted sigmoid structure (Figure 1). It is also important to note that the drying rate corresponds to the slope of the curve. In general, three drying phases can be distinguished in these curves [15]. The figure shows that and are only constant in phase B of Figure 1. After a certain point, called the critical point, they vary with moisture content.

Figure 1.

Typical Drying Curve.

The convective drying model describes a process in which air circulation is used to remove moisture from a material, generally through water evaporation. In this context, air circulation is considered to be practically adiabatic, meaning that there is no significant heat exchange with the environment, and the system maintains its internal energy constant [11,16].

In this type of drying, when a large volume of air comes into contact with a small amount of water, thermal equilibrium is established between the two substances. That is, the air, initially at a higher temperature than the water, transfers part of its heat to the water, causing its evaporation. This heat transfer occurs without a significant change in the enthalpy of the dry air. In simple terms, the enthalpy per kilogram of dry air does not vary substantially when the air comes into contact with the water.

It is established that the mixing does not occur directly between the solid surface and the airflow but rather between the air and a saturated air layer located on the product’s surface. This saturated air layer has a temperature equal to the wet-bulb temperature of the air. In the psychrometric diagram, the point representing this saturated air layer is found at the intersection between the isenthalpic line corresponding to the drying air and the saturation curve.

Predicting the drying rate through mass transfer models can be quite complex, as there are no devices that allow for evaluating the variability of diffusivity and the convection coefficient, and the accuracy of these models is often insufficient for practical applications. One of the main limitations lies in the fact that mass transfer parameters, such as diffusivity and the convective mass transfer coefficient, do not usually remain constant throughout the drying process but instead vary with the material’s moisture content. This means that the drying rate is not uniform and can undergo significant changes as the process progresses and the material’s moisture decreases. This variability makes it difficult to accurately predict the drying rate and requires more sophisticated models that account for these variations in mass transfer parameters.

Additionally, other factors such as material geometry, temperature, air velocity, and relative humidity can also influence the drying rate and must be considered in models to obtain more precise predictions. In general, the development of mass transfer models for predicting the drying rate is an active and evolving research area, requiring a careful and detailed approach to address all the complexities involved in the drying process.

This study aims to optimize the operation of a prototype device for measuring mass transfer phenomena in biomass drying processes. The device, patented by the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV) and the Escuela Politécnica del Litoral (ESPOL) under patent WO2025/109237 A1 [17], allows for determining the mass diffusivity of materials and the convective mass transfer coefficient.

The prototype used in this study focuses on the use of a continuous airflow, which can be either heated or at ambient temperature. It allows for the analysis of variables that determine the drying time for each experiment. On one hand, the air parameters controlled include velocity, temperature, humidity, and direction. On the other hand, the product parameters analyzed include weight, size, structure, and moisture content (percentage of water by weight). By knowing the experimental conditions, time-moisture relationships for the drying product can be established. While the food industry also monitors changes in volume, density, sample dimensions, microstructural alterations in the solid matrix, or the evolution of quality parameters (color, odor, taste) in addition to weight (moisture), for biofuel production, the focus is exclusively on moisture. This is because the drying process does not affect the other properties that determine the fuel material’s quality.

It is crucial to ensure that, for the device to properly evaluate the drying process, the hot air stream flows homogeneously across the entire drying surface. Additionally, the drying rate depends on various factors, such as the product’s sorption isotherm, product dimensions, air temperature, and relative humidity, among others. The study of the drying system focuses on mass transfer models to calculate diffusivity and the convective mass transfer coefficient.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Equipment Description

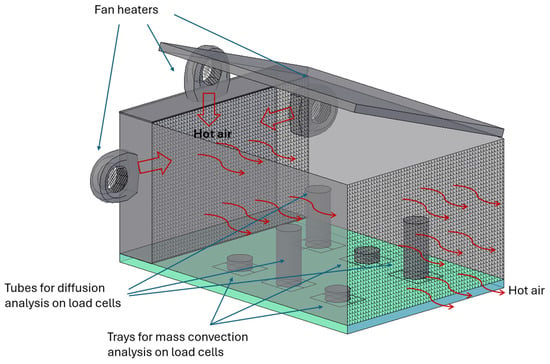

The prototype consists of a prismatic box measuring 120.3 cm × 80 cm × 54.3 cm, made of a prefabricated waterproofing material based on laminated aluminum, coated with modified asphalts and SBS synthetic polymers, which provide high resistance and adhesion. The structure is assembled using 20 mm Bosch profiles. Access to the box is from the top through a hinged lid (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic of the Prototype Box with Hinged Gate.

The box is divided into two sections: a pre-chamber measuring 17 cm in length and a main chamber measuring 103.5 cm in length. These chambers are separated by a micro-perforated steel sheet that allows air to pass between them. The purpose of the pre-chamber is to generate a uniform airflow across the cross-section of the equipment with longitudinal displacement. To achieve this, the pre-chamber houses air generators and heating elements. These generators consist of fans mounted on the transverse walls and upper part of the pre-chamber, ensuring that the airflow does not directly hit the perforated sheet but rather changes direction before passing through.

The accumulation of air in the pre-chamber creates uniform overpressure, forcing the air through the micro-perforations of the separating sheet. This results in a uniform flow with a constant temperature in the longitudinal direction. Additionally, the mixing of air streams helps to homogenize the temperature throughout the pre-chamber.

One of the key claims of the patent is the use of the pre-chamber to homogenize the cross-sectional air flow at a controlled temperature. Another feature is the incorporation of load cells for real-time mass measurement during the drying process by diffusion and convection.

At the end of the main chamber, another micro-perforated sheet is placed to ensure proper airflow (Figure 2).

Inside the main chamber, six platforms are arranged to hold open containers (trays) or semi-open containers (tubes) where the samples are placed. Each platform is equipped with a load cell that periodically records the weight of the samples.

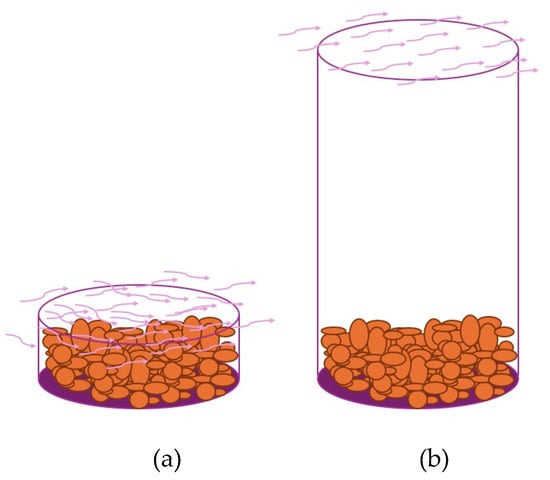

The trays, positioned on the platforms along with the samples, are exposed to an airstream that directly impacts the biomass surface. This airflow facilitates heat and mass transfer, promoting the progressive removal of moisture from the material by convection (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Schematics of the Containers Used in the Prototype.

The tubes are filled with the biomass under study up to a height of 5 cm from the bottom, ensuring a homogeneous distribution of the material inside. Once prepared, these tubes are placed on the weight measurement platforms, enabling continuous monitoring of mass variation throughout the process.

In this setup, the airflow circulates only over the top of the tubes, without making direct contact with the biomass inside. As a result, water removal occurs predominantly through a diffusion mechanism, driven by the humidity gradient between the solid-air interface and the air flowing over the tube’s opening. As the biomass moisture migrates toward the exposed surface, the moving air facilitates its removal, regulating the drying kinetics and influencing the process efficiency based on the relative humidity difference between the material and the airflow (Figure 3b).

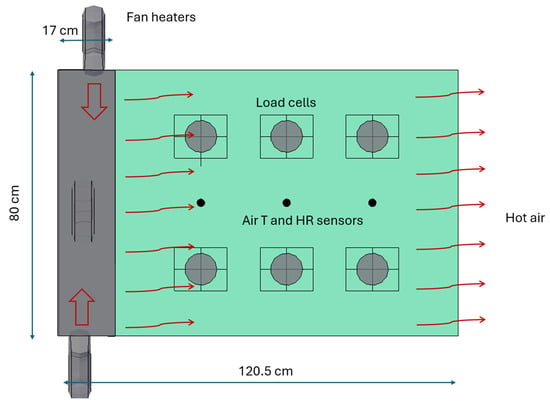

The prototype is equipped with three OK brand OFH 120224 ES fan heaters installed in the pre-chamber (manufactured in Rochin, France). The heating elements have three power levels: 0, 1000, and 2000 W. The heaters are interconnected and operate automatically when the prototype is turned on. Additionally, the heating power of the resistances can be continuously adjusted using a variable controller (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Prototype Diagram (Top View) (T: Air Temperature, HR: Air Relative Humidity).

In the second chamber of the experimental system, a set of measurement devices has been installed to monitor, in real time, variations in biomass mass as well as environmental conditions inside. To determine the weight, six single-point load cells have been incorporated, each with a capacity of 10 kg. These cells, model Screw, have an aluminum housing with dimensions of 25 × 40 × 150 mm and belong to the Siemens brand, ensuring precise mass measurement of the samples.

To characterize the air conditions inside the chamber, five temperature sensors and five humidity sensors have been strategically placed. Four of these sensors are distributed at two height levels: two are positioned 23 cm from the perforated sheet of the pre-chamber, placed at 10 cm and 30 cm above the floor, while the other two are located 50 cm from the same sheet, maintaining the same heights of 10 cm and 30 cm. A fifth sensor has been placed 71 cm from the perforated sheet, at a height of 10 cm above the floor, allowing for a detailed profile of humidity and temperature variation at different points in the chamber.

The temperature sensors used in the system are type K thermocouples, paired with MAX6675 modules (manufactured by Maxim Integrated/Analog Devices, Singapore), which operate based on the junction of two different metals that generate a potential difference proportional to the temperature, with a resolution in the range of microvolts per degree Celsius (µV/°C). For measuring the relative humidity of the air, DHT22 sensors have been employed, high-precision devices that provide real-time data on the hygrometric conditions inside the chamber. This sensor arrangement ensures detailed control of environmental variables, facilitating the analysis of the drying process behavior.

At the bottom of the box, the bases of the load cells are installed, providing stability and precision in measuring the biomass sample weight. These bases ensure a uniform load distribution on the sensors, optimizing the accuracy of the data obtained during the monitoring process.

The data collected by the load cells and environmental sensors is processed by an Arduino Mega 2560 controller (manufactured by Arduino, Scarmagno, Italy), mounted externally on a support for easy accessibility and connection with other devices. The Mega 2560 is a development board based on the Atmega2560 microcontroller (manufactured by Microchip Technology, Penang, Malaysia), characterized by its high processing capacity and a large number of input and output pins, making it ideal for systems with multiple sensors and actuators.

This board features 54 digital input/output pins, 15 of which can function as PWM outputs, allowing for the precise control of electronic devices. Additionally, it has 16 analog inputs, essential for acquiring data from temperature and humidity sensors, as well as 4 UARTs (hardware serial ports) for communication with additional peripherals. Its operation is based on a 16 MHz oscillator, providing adequate processing speed for real-time monitoring tasks.

For power supply, the Mega 2560 can be connected via a USB cable to a computer or through an AC/DC adapter or battery, ensuring flexibility in its use. Furthermore, it includes an ICSP (In-Circuit Serial Programming) connector for direct microcontroller programming and a reset button to restore operation when necessary.

This board is compatible with most shields designed for the Arduino Uno, as well as previous versions like Duemilanove or Diecimila, facilitating integration with other electronic modules. The Mega 2560 is programmed using the Arduino IDE 2x software, an open-source development platform that allows users to write, compile, and upload programs intuitively.

At the bottom of the box, a current variator, model Variac MVT2.5k/9A-1 (manufactured by Carroll & Meynell, Istanbul, Turkey), is installed to precisely regulate the temperature of the resistances used in the drying system. This device operates at a voltage of 240 V, a power of 2.5 kVA, a single phase, and a single output, providing controlled adjustment of the electrical current supplying the heaters.

The Variac simultaneously regulates the three heater resistances, allowing the supplied power to be adjusted according to process requirements. This enables the selection of air temperature inside the chamber, allowing operation with cold, warm, or hot air depending on the percentage of power assigned to the resistances. This precise temperature control is essential for optimizing drying conditions and evaluating the impact of different thermal configurations on the studied biomass.

The system has two main cables ensuring proper operation: on one hand, a DC power supply providing energy to the Variac and the heaters, ensuring a stable power supply for thermal regulation; on the other hand, a USB Type-A cable connecting the Arduino Mega 2560 to the computer responsible for data processing. In addition to transmitting the recorded sensor data, this cable powers the load cells and environmental sensors, eliminating the need for additional external power sources.

This electrical and communication infrastructure ensures efficient system control, allowing temperature regulation and real-time data collection for further analysis.

A dedicated program has been developed for managing the prototype’s data on the computer connected to the Arduino. In this program, the frequency of data extraction can be selected; for this specific study, a three-minute interval between data collection points has been determined as appropriate. Data extraction is structured as follows: first, the readings from the six load cells are recorded, followed by the five temperature sensors, and finally, the five humidity sensors.

The data is exported to an Excel spreadsheet, where calculations are performed to determine the drying rate over time. Based on this determination, the diffusivity coefficient is obtained from the data recorded in the tube samples, and the convective mass transfer coefficient is determined from the data extracted from the tray samples.

2.2. Sample Preparation

For the prototype evaluation tests, experiments were conducted using wood chips obtained from the pruning of Jacaranda mimosifolia trees. The samples were collected from the surroundings of the School of Agricultural and Rural Environment Engineering (ETSIAMN) at the Polytechnic University of Valencia (Valencia, Spain). The thinnest branches from pruning were stored in a refrigerated chamber at 4 °C to maintain their moisture content as much as possible until the experiments were performed, approximately one week later.

After pruning, the branches were shredded using the Bio 320 chipper, manufactured by Greens Power Products S.L., La Garriga (Spain), belonging to the Agricultural Mechanization and Technology Unit of the Universitat Politècnica de València (UPV). This chipper is powered by a Honda GX 270 engine, manufactured in Hamamatsu, Japan. (Figure 5), with a displacement of 270 cm3, driving two fixed blades capable of cutting branches with a maximum diameter of 8 cm.

Figure 5.

Pruning Residue Shredder and Study Material Samples.

From this process, two types of material were obtained: fine shavings and small, whole branch pieces.

To determine the initial moisture content of the wood before each test, four random samples were taken, weighed before and after being placed in an oven at 100 °C for a minimum of two hours.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the particle sizes of the wood chips used in the experiments.

Table 1.

Dimensions of the wood chips used in the drying process (Figure 5).

2.3. Determination of the Diffusivity Coefficient and Mass Transfer by Convection

For the calculation of diffusivity and convection mass transfer coefficients in each experiment, Equations (4) and (5) are used, derived from Fick’s equation (Equation (1)) and the mass transfer by convection equation (Equation (3)).

represents the drying rate (g of water/s), calculated at each instant using Equation (6), where is the mass of the sample at the instant , and is the mass of the sample at the instant .

The mass difference is obtained from the load cells, after correction with the drift curves previously studied. is the length of the tube from the biomass surface to the upper opening, which had a value of 30 cm. is the transfer area, considered as the cross-sectional area of the tube or the area of the tray, respectively, in m2.

The air density at each instant () can be calculated from the average temperatures recorded by the 5 sensors in K, using the ideal gas law, where is the pressure (1 atm), is the air volume in liters, is the universal gas constant (0.082 L·atm/mol·K), and is the number of moles, which can be calculated as the mass of the air divided by the molecular weight of the mixture () of N2 (79%) and O2 (21%), i.e., 28.96 g/mol.

is the absolute humidity of the saturated air at the solid (biomass) and air interface. That is, the g of water/g of dry air, near the surface of the biomass under saturation conditions (maximum allowable moisture in the air as vapor). This humidity can be calculated from the saturated vapor pressure () at the considered temperature T. The saturated vapor pressure is calculated using Equation (10), where is expressed in °C and and atmosphere pressure () are obtained in pascals.

is the absolute humidity of the air circulating through the chamber, passing over the top of the opening of the tubes, or over the top of the biomass placed in trays. This humidity can be calculated using Equation (12), where is the vapor pressure of the air in pascals.

The vapor pressure of the air can be calculated from the relative humidity, which is obtained as the average of the five sensors of the prototype.

From the saturated vapor pressure and the average relative humidity RH (%), obtained from the five sensors, we obtain the vapor pressure, and the pressure will be the air pressure plus the vapor pressure:

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Evaluation of Water Loss by Diffusion

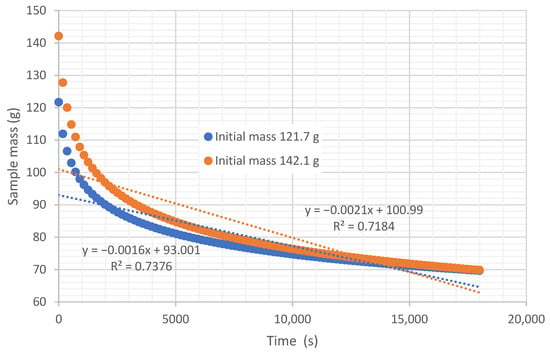

In the experiments conducted with tubes, the objective was to determine the diffusivity at the solid-air interface of the biomass deposited at the base of the tube. Figure 6 shows, as an example, the curves obtained in one of the experiments, performed with an air flow at 45.35 °C and a relative humidity of 22.38%. In this case, the initial wet mass of one of the experiments was 142.1 g, and the other 121.7 g. It can be observed that the mass reaches equilibrium at 70 g. Both samples had a similar initial moisture content on a wet basis of 44.6%.

Figure 6.

Variation in wet mass in the tube over time, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air velocity 0.254 m/s.

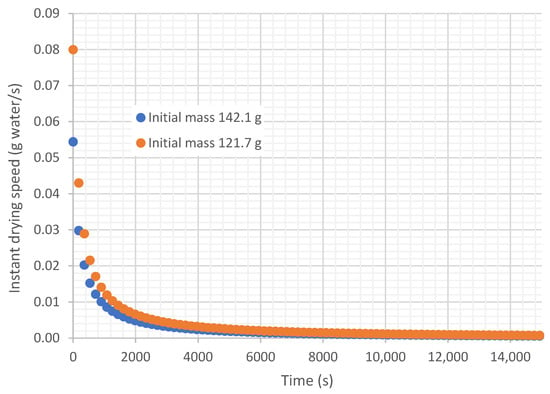

It is demonstrated that the instantaneous drying rate (g of water dried per second) is not constant over time but varies. Figure 7 shows the variation in drying rate over time in the experiments taken as an example. Given this variation in speed, several criteria can be used to define an average drying rate for the experiment. On one hand, many authors calculate the average drying rate as the average of the instantaneous drying rates (average criterion); other authors take the average drying rate as the difference between the initial and final mass, divided by the process time (mass loss criterion); while others take the slope of the linear trend curve as the average drying rate (slope criterion), as is shown in Figure 6 with 0.0021 g dried water/s and 0.0016 g dried water/s.

Figure 7.

Variation in drying rate in the tube with time, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air velocity 0.254 m/s.

The instantaneous drying rate would be calculated with Equation (6), where is the mass of the sample at time , and is the mass of the sample at time .

Table 2 shows the average drying rates and mass diffusivity obtained with each of the criteria in four experiments: two at ambient temperature, and two at elevated temperature.

Table 2.

Values of average drying diffusivity with different criteria.

It can be deduced that the calculation of the average drying rate using the average criterion has the highest value, and therefore would provide a lower estimate of the drying time. This is because, in the initial moments of the process, the drying rate is very high but decreases rapidly. Therefore, when averaging the instantaneous rates, very high values in the early measurements and very low values in the final phase of the experiment are considered, which distorts the estimate. A conservative value would be to use the slope of the linear regression line, which would provide a higher estimate of drying time (Figure 6).

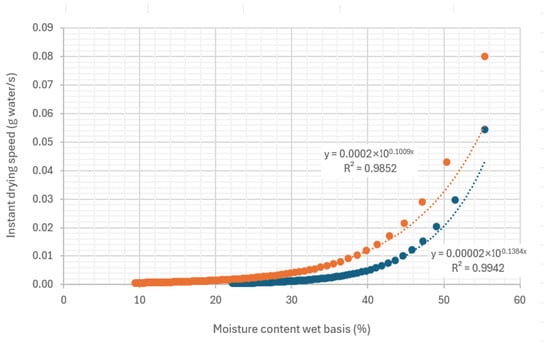

Given fixed characteristics of the biomass (porosity, granulometry, etc.) for conditions of air temperature, relative humidity, and air velocity, the factor that most influences water loss is the moisture content of the material. As moisture decreases, the drying rate also decreases. Figure 8 shows the variation in the drying rate with humidity in the ex-experiments carried out with hot air.

Figure 8.

Variation in drying rate in the tube with the moisture content on a wet basis of the sample, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air velocity 0.254 m/s.

It can be observed in Figure 8 that no initial constant drying rate period was detected. Authors such as Lu et al. (2016) [18], or Tripathi et al. (2019) [19], report that at high moisture levels, there is a period of constant drying rate, with the critical moisture defined as the moisture below which the drying rate is no longer constant (Figure 1). This period of constant drying rate has not been detected with the granulometry and initial moisture content of the evaluated samples. This may be because the initial moisture levels were below the critical moisture.

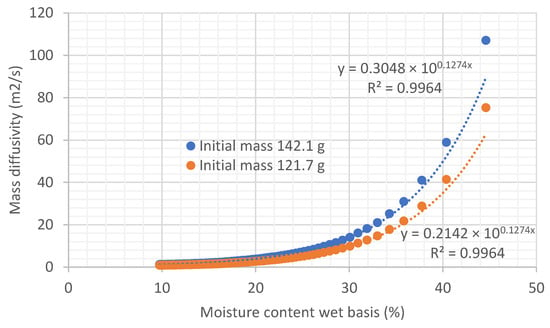

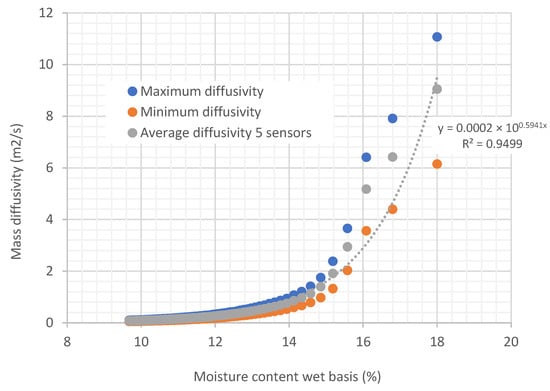

If diffusivity at the solid-air interface of the biomass is calculated using Equation (4), derived from Fick’s Law, it can be observed that the diffusivity of water is also not constant throughout the drying process but depends on the moisture content. Figure 9 shows this variation in diffusivity in the experiments taken as examples. It is shown that the variation in diffusivity with moisture follows an exponential equation.

Figure 9.

Representation of the variation in diffusivity as a function of moisture on a wet basis of the sample, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air velocity 0.254 m/s.

Similarly to what happens with the drying rate, it is difficult to establish an average diffusivity value during the process. Different criteria could be used. One possible approach is to take the average drying rate values with each of the criteria shown in Table 2 to deduce a diffusivity value by applying Equation (4) (with tube sizes: L = 0.3 m, A = 0.2 m2).

Note that diffusivity will depend not only on moisture but also on temperature. The evaluated equipment would allow obtaining equations for the variation in diffusivity for different moisture levels and temperatures for various materials. These curves will differ for biomass with different porosities, the chemical nature of the internal structure of the biomass (due to charges and the polarity of radicals that attract water), granulometry, and apparent density (which can be modified by vibration and compression of the particles).

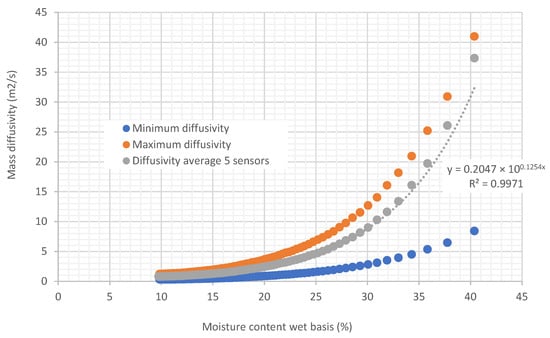

Figure 10 and Figure 11 show two example curves of the relationship between diffusivity and biomass moisture in two of the experiments conducted with the prototype. The experiment in Figure 10 was performed with air flow at ambient temperature, while the experiment in Figure 11 was performed with hot air flow.

Figure 10.

Curves relating diffusivity to the moisture content of biomass in tubes under an air flow at a temperature of 22.35 °C and 43.21% relative humidity, with an airspeed of 0.254 m/s.

Figure 11.

Curves relating diffusivity to biomass moisture in tubes under air flow at a temperature of 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air velocity 0.254 m/s.

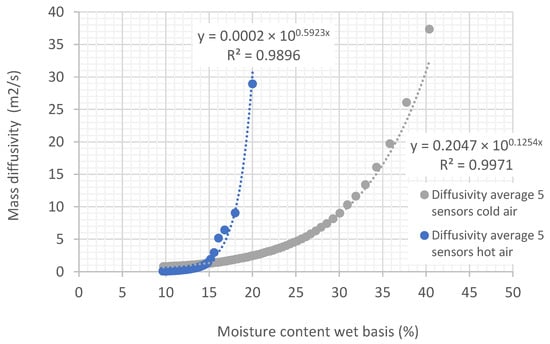

In Figure 10 and Figure 11, it can be observed that diffusivity varies exponentially with the moisture content of the biomass. Note that the temperature in the experiment shown in Figure 11 is 20 degrees higher than the air temperature used in the experiment of Figure 10. When comparing the two curves (Figure 12), it can be seen that the diffusivity obtained at a higher temperature is greater than the diffusivity obtained at lower temperatures. Average values are presented in Table 2.

Figure 12.

Curves relating diffusivity to the moisture content of biomass in tubes under an air flow at temperatures of 22.35 °C and 46.75 °C, with relative humidity of 45.35% and 22.38%, respectively, and an air speed of 0.254 m/s.

Diffusivity generally increases with temperature. This behavior can be explained by the kinetic theory of molecules, which states that as temperature increases, molecules or atoms acquire more kinetic energy. With greater kinetic energy, molecules move faster, facilitating their transport through the medium. In the case of diffusion of liquids or gases, an increase in temperature allows molecules to move more easily through the pores or spaces of the medium. With increasing temperature, molecules not only move faster but can also overcome energy barriers (such as intermolecular interactions) more easily, enabling more efficient transport of matter.

One of the most common models to describe the relationship between diffusivity and temperature is the Arrhenius Equation (14). According to this equation, diffusivity increases exponentially with temperature because the activation energy is more easily overcome at higher temperatures.

is the diffusivity at temperature T.

is a pre-exponential factor that depends on the material.

is the activation energy for the diffusion process.

is the gas constant.

is the temperature in kelvins.

In some cases, an increase in temperature can also modify the structure of the medium through which the solute or molecules diffuse. For example, in solids or gels, an increase in temperature can cause softening or expansion of the material, which facilitates the passage of molecules. In liquids, a higher temperature can reduce viscosity, which also facilitates diffusion.

In general, diffusivity increases with temperature, since higher thermal energy facilitates the movement of molecules and improves mass transfer. This behavior can be described by the Arrhenius equation, although the exact effect depends on the type of material and the state of the medium. At high temperatures, the effects on the material’s structure can also influence the diffusion rate. That is the reason why, compared to Figure 10, it can be observed that Figure 11 has more scattered points in terms of diffusivity.

In this regard, the prototype offers significant potential as a research tool for determining under different conditions. It is also applicable not only to lignocellulosic biomass but also to the drying of leaves, fruits, flowers, food, leather, soils, among others.

3.2. Evaluation of Water Loss by Convection

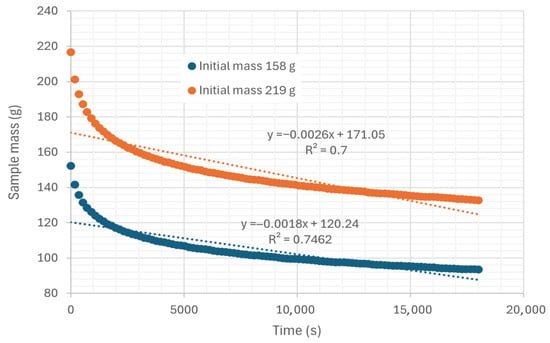

For the evaluation of convection processes, the samples are placed in trays on load cells. The air current directly impacts the biomass surface, allowing the removal of water particles. Table 3 shows four experiments for calculating the transfer coefficient by convection, two performed at room temperature and two performed with hot air. Figure 13 shows the mass variation in two examples of convective drying performed in a tray with hot air. The initial wet mass of one sample was 219 g, while the other was 158 g. In these experiments, the air temperature and relative humidity were 45.35 °C and 22.38%, respectively. The curves are practically parallel if the difference between them corresponds to the difference in mass of the sample.

Table 3.

Average drying rate values in convection using different criteria.

Figure 13.

Representation of the variation in mass as a function of time in trays, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air speed 0.254 m/s.

Notably, the average drying rate is higher than in the diffusion evaluations conducted with the tubes. Table 3 presents the average drying rates calculated using the mean criterion, mass loss criterion, and slope criterion, and the calculation of the mass transfer coefficient by convection using Equation (5).

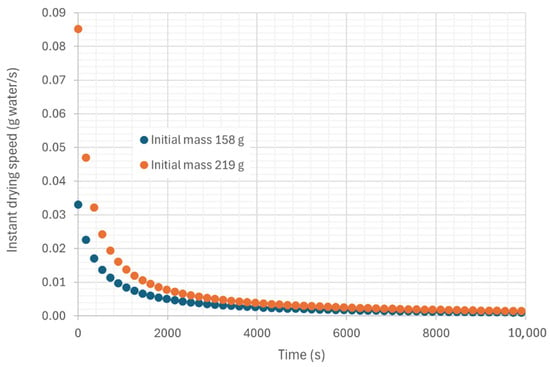

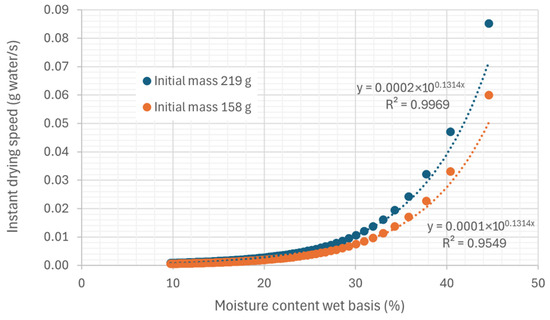

Figure 14 shows the drying rate over time during the hot air convection process, and Figure 15 shows the variation in the drying rate with the moisture content of the biomass on a wet basis.

Figure 14.

Representation of the variation in instantaneous drying rate as a function of time in trays, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air velocity 0.254 m/s.

Figure 15.

Representation of the variation in the instantaneous drying rate as a function of moisture on a wet basis in trays, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air speed 0.254 m/s.

It can be observed that the drying rate gradually decreases over time, a phenomenon common in many dehydration processes. This decrease in drying rate is closely associated with a reduction in the amount of moisture available in the sample as the process progresses.

In the early stages of drying, the sample contains a large amount of free water on its surface and in the larger pores, facilitating rapid moisture exchange between the sample and the environment. However, as drying progresses and the residual moisture decreases, the water in the sample becomes more trapped in the internal layers or more tightly bound to the material’s structure, making its removal more difficult. This phenomenon is known as the delayed drying phase or the slow drying phase, in which the resistance to mass transfer increases due to the reduced availability of water for evaporation.

Furthermore, as the moisture content decreases, the diffusivity of water also decreases, causing the evaporation rate to slow down. This behavior is typical in drying processes where the interaction between residual moisture and the internal structure of the sample limits mass transfer, which is reflected in the drop in drying rate over time.

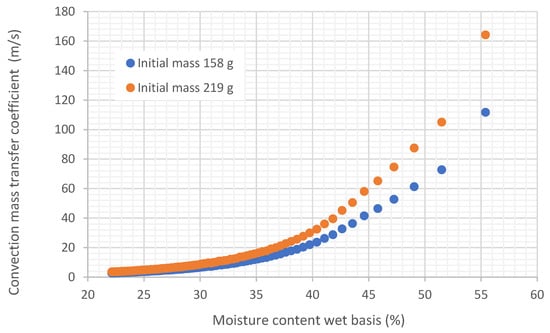

Figure 16 shows the variation in the mass transfer coefficient by convection as a function of moisture.

Figure 16.

Representation of the variation in the mass transfer coefficient by convection as a function of moisture on a wet basis in trays, under an air flow at 45.35 °C and 22.38% relative humidity, air speed 0.254 m/s.

It is demonstrated that the mass transfer coefficient by convection is also variable with moisture. This fact is consistent since it depends on diffusivity.

3.3. Comparison of Experimental Data with Those Obtained from Theoretical Mass Transfer Models

In the literature, there are numerous models attempting to predict the drying rate of various materials in convective processes based on the characteristics of the air flow, such as temperature, relative humidity, and circulation speed. Most of them are based on the drying Equation (3), where the goal is to predict the coefficient for given conditions.

One of the most commonly used methods is that proposed by Sherwood (1929) [20], Sherwood and Comings (1933 and 1934) [21,22]. These researchers proposed Equation (15), relating to a dimensionless number, called the Sherwood number (), the characteristic length of the piece, , and the diffusivity of water particles at the solid-air interface, .

The characteristic length in a horizontal flat surface is the length of the piece in the same direction as the air flow. In a flow perpendicular to a cylindrical or prismatic surface or in an internal flow, is considered to be 4 times the area divided by the perimeter.

The Sherwood number is a dimensionless number that depends on the Reynolds number () and the Schmidt number () through Equation (16), when the regime is laminar, or Equation (17) when it is turbulent. In this way, it relates the drying rate to the flow regime.

The Reynolds number and Schmidt number are calculated using Equations (18) and (19), where v is the air circulation speed, is the air density, and μ is its dynamic viscosity.

Note that for the application of the method proposed by Sherwood, it is necessary to know the mass diffusivity precisely, and on the other hand, the density and viscosity of air depend on temperature.

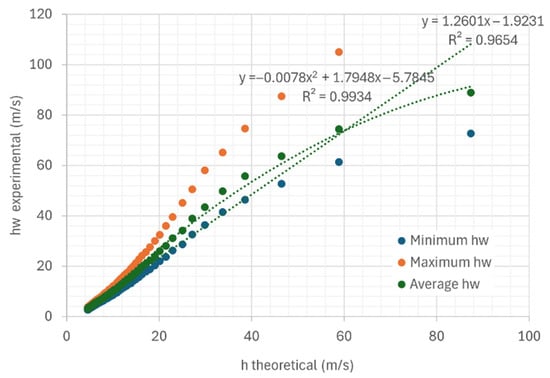

One of the applications of the evaluated prototype is to allow comparison of the experimental measurements with those calculated using the proposed theoretical model. Table 4 shows the theoretical values of the convection drying rate using the Sherwood model in the examples shown.

Table 4.

Theorical drying rate values in convection using Sherwood model.

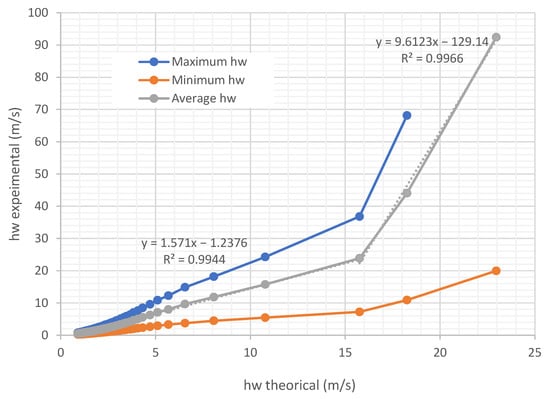

Figure 17 and Figure 18 show example curves comparing the determinations obtained with the prototype and the calculation of by the Sherwood method. The air circulation speed for all the experiments shown is 0.254 m/s. It can be seen that both the theoretical and experimental change throughout the evaluation process. In the experiments carried out (Figure 17 and Figure 18), if we consider the average curve of all the sensors, the mass transfer coefficient by convection differs between 2.54% and 56% from that estimated by the theoretical model.

Figure 17.

Comparison curves of experimental obtained with the prototype and theoretical obtained by the Sherwood method on trays under air flow at a temperature of 22.95 °C and 33.06% relative humidity, air speed 0.254 m/s.

Figure 18.

Comparison curves of experimental obtained with the prototype and theoretical obtained by the Sherwood method on trays under air flow at a temperature of 45.35 °C and 20.38 relative humidity, air speed 0.254 m/s.

In Figure 18, which shows the comparison curves between the experimental obtained with the prototype and the theoretical obtained by the Sherwood method on trays under airflow, the exponential approximation is unsatisfactory. This is because the experimental data do not follow the characteristic behavior of an exponential curve throughout the entire drying process, as would be expected under certain idealized drying conditions.

This two-stage fit provides a more accurate representation of the actual drying process, as it captures both the rapid and slow drying phases more precisely than the exponential model. This approach also better reflects the experimental conditions, where moisture distribution and variability in mass transfer play a significant role.

The deviations of the theoretical estimation from the experimental data increase as the values of this variable grow.

Finally, and importantly, assuming a constant mass transfer coefficient by convection, estimated by the Sherwood method, leads to a significant error in the estimation of the drying rate, since, as demonstrated in this study, the value of this coefficient changes over time, just as the moisture content varies for a given drying temperature.

One of the applications of the prototype is the determination of the Biot number in mass transfer processes. This number is a dimensionless parameter that relates the mass transfer rate by diffusion within the material to the mass transfer rate by convection on the surface. Its mathematical expression is given by:

where is the mass transfer coefficient by convection, is the characteristic length of the material, and is the diffusion coefficient of moisture in the material.

A high Biot number indicates that the rate of water transfer by convection on the surface of the material is considerably greater than the mobility of water inside the material by diffusion. This generates moisture gradients inside the material, where the outer layers have lower moisture content compared to the inner layers. This phenomenon is characteristic of systems with a high mass transfer coefficient by convection and a large characteristic length, making homogeneous drying more difficult.

The occurrence or absence of moisture gradients in materials during the drying process makes modeling very challenging. A significant group of researchers, such as [23,24,25]; Some researches have tried to model drying based on mass transfer phenomena [26]. These models require precise measurements of and [26,27,28].

On the other hand, there is no general agreement on the Biot number value at which models considering these gradients should be used, or models that assume uniform moisture during the process. As demonstrated, the development of the prototype allows for the precise analysis of the Biot number.

4. Conclusions

The present study has shown the following:

- The estimation of the mass transfer coefficient using the theoretical Sherwood method presents significant discrepancies when compared to the experimental data obtained. These deviations can be attributed to the simplification of certain parameters within the theoretical model, which limits its applicability under real operating conditions.

- One of the determining factors for this error is the assumption that the surface mass transfer coefficient, , remains constant throughout the drying process. In practice, this parameter varies depending on various conditions, such as the moisture content in the drying material. By assuming a fixed value for , significant inaccuracies are introduced into the calculation of both the drying time and the rate at which the convection process occurs. These differences can lead to errors in the design and optimization of industrial drying systems, affecting their efficiency and energy performance.

- Due to these limitations, the development of a device capable of accurately measuring the mass transfer coefficient under controlled experimental conditions is crucial. The implementation of a measurement device will allow the adjustment of existing theoretical models and improve the prediction of drying behavior by convection. This will lead to a better understanding of the phenomena involved, optimizing equipment design and reducing operational costs in industrial and laboratory applications.

- In this study, the performance of a prototype from patent WO2025/109237 A1 has been evaluated to assess the mass transfer phenomena in drying processes. It has been demonstrated that the prototype allows for the determination of diffusivity and the mass transfer coefficient by convection in drying processes, validating the proposed method.

- It has been demonstrated that the water diffusivity at the solid-air interface in a diffusion drying process is not constant but depends on the moisture content of the biomass and temperature. Since moisture changes over time, diffusivity also varies. Average values can be taken from different criteria to calculate the average drying rate: the mean criteria, mass loss criteria, and slope criteria.

The prototype is presented as a research instrument that allows the evaluation of the influence of different factors on drying rate, diffusivity, and mass transfer coefficient by convection.

The evaluated equipment would enable the derivation of equations for the variation in diffusivity as a function of different moisture contents and temperatures for various materials. These curves will differ based on the porosity of the biomass, the chemical nature of its internal structure (due to the charges and polarity of the radicals that attract water), the granulometry, and the apparent density, which can be altered by vibration and compression of the particles.

It should be noted that the experiments were performed with a low air velocity (0.254 m/s), resulting in laminar flow according to the classical definitions of fluid dynamics. The authors understand that, in industrial drying, airflow is predominantly turbulent, as this type of flow enhances mass transfer and accelerates the drying process. The choice of laminar conditions was intentional in order to study the process behavior in a controlled and reference scenario, allowing us to analyze how air velocity influences mass transfer within a specific range of low velocities. This enabled us to obtain clear and comparable data on diffusivity and mass transfer coefficients under controlled conditions. Furthermore, laminar flow offers advantages by reducing measurement variability, thus facilitating the interpretation of the results. It exists the need for further experiments with higher air velocities to evaluate the impact of turbulent flow on drying efficiency. However, the measurements obtained provide a useful basis for improving our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms under controlled conditions, which could then be extrapolated or adjusted to more realistic scenarios.

It is important to mention that particle drying processes can be carried out in two main ways. In the first method, the airflow is passed over a tray or tube so that the air stream comes into contact with the particles on the surface of the pile tangentially, facilitating mass transfer. In this case, drying is more efficient when the particles are directly exposed to the airflow, which accelerates the evaporation of water from the exposed surfaces.

In the second method, there are mechanisms in which the airflow is induced through the gaps between the particles, flowing in the same direction as the length of the tube, passing through the mass of the particles. This type of drying is particularly useful when more homogeneous drying is desired, as the air can penetrate the interior of the container and accelerate the removal of moisture from internal layers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: B.V.-M. Methodology: I.G.-V., B.V.-M., I.L.-C. and D.D.M.-V. Investigation: I.G.-V., D.D.M.-V. and I.L.-C. Formal analysis: I.G.-V., B.V.-M. and I.L.-C. Data curation: I.G.-V. and B.V.-M. Writing—original draft preparation: I.G.-V. and B.V.-M., Writing—review and editing: B.V.-M. Supervision, validation, funding acquisition, project administration, and resources: B.V.-M. and I.L.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data generated and analyzed during this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work has been carried out within the framework of the IBEROMASA Network of the Ibero-American Program of Science and Technology for Development (CYTED).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sabbaghi, M.A.; Baniasadi, E.; Genceli, H. Thermodynamic assessment of an innovative biomass-driven system for generating power, heat, and hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 75, 529–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, C.N.; Dhanushkodi, S.; Sudhakar, K. Sustainable Technology for Coconut Processing: Biomass-powered Dryer and Performance Evaluation. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagernäs, L.; Brammer, J.; Wilén, C.; Lauer, M.; Verhoeff, F. Drying of biomass for second generation synfuel production. Biomass Bioenergy 2010, 34, 1267–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, J.; Li, X.; He, J.; Duan, X. Drying efficiency and product quality of biomass drying: A review. Dry. Technol. 2020, 38, 2039–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delfiya, D.S.A.; Prashob, K.; Murali, S.; Alfiya, P.V.; Samuel, M.P.; Pandiselvam, R. Drying kinetics of food materials in infrared radiation drying: A review. J. Food Process. Eng. 2022, 45, e13810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzwa, D.; Musielak, G. Convective–Microwave–IR Hybrid Drying of Kaolin Clay—Kinetics of Process. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, O.; Bond, B. Vacuum drying of wood—State of the art. Curr. For. Rep. 2016, 2, 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Martí, B.; Gaibor-Chávez, J.; Pérez-Pacheco, S. Quantification based on dimensionless dendrometry and drying of residual biomass from the pruning of orange trees in Bolivar province (Ecuador). Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefining 2016, 10, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandía-Ventura, I.; Martí, B.V.; Cortes, I.L.; Guerrero-Luzuriaga, S. Kinetic Models of Wood Biomass Drying in Hot Airflow Systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Martí, B.; Neto, A.B.; Retana, D.N.; Parra, A.C.; Guerrero-Luzuriaga, S. Determination of biomass drying speed using neural networks. Biomass Bioenergy 2024, 186, 107260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujumdar, A.S. Handbook of Industrial Drying; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, M.; Titikshya, S.; Aradwad, P.; Kumar, V.; Naik, S.N. Study of the drying behaviour and color kinetics of convective drying of yam (Dioscorea hispida) slices. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 176, 114258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arranz, J.I.; Miranda, M.T.; Sepúlveda, F.J.; Montero, I.; Rojas, C.V. Analysis of Drying of Brewers’ Spent Grain. Proceedings 2018, 2, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomasson, T.; Raitila, J.; Tsupari, E. Experimental and techno-economic analysis of solar-assisted heat pump drying of biomass. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noguera, A.M.F.; Iturgaiz, I.A. Experimental determination of dynamic pseudo-equilibrium moisture content: A practical limit for the drying process. MethodsX 2023, 11, 102410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velázquez-Martí, B. Treaty on the Energy Use of Biomass; Universitat Politécnica de València: Valencia, Spain, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Velázquez-Martí, B.; Plaza, E.D.; Jaramilo, J.P.; Tigre, J.R. WO2025109237—Mass Transfer Measuring Apparatus. 2025. Available online: https://patentscope.wipo.int/search/en/WO2025109237 (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- Lu, Z.; Ma, C.; Zhao, Z.; Jia, W.; Wang, M. Effects of hot air drying time on properties of biomass brick. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2016, 109, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, N.; Hills, C.D.; Singh, R.S.; Atkinson, C.J. Biomass waste utilisation in low-carbon products: Harnessing a major potential resource. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2019, 2, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, T.K. The drying of solids I. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1929, 21, 12–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, T.K.; Comings, E.W. The drying of solids VII. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1934, 26, 1096–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, T.K.; Comings, E.W. The drying of solids V. Mechanism of drying of clays. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1933, 25, 311–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamtree, S.; Ratanawilai, T.; Nuntadusit, C.; Marzbani, H. Experimental study and numerical modeling of heat and mass transfer in rubberwood during kiln drying. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 57, 453–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dedic, A.D. Modelling of Coupled Heat and Mass Transfer During Convective Drying of Wood. Dry. Technol. 2002, 20, 1299–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koukouch, A.; Bakhattar, I.; Asbik, M.; Idlimam, A.; Zeghmati, B.; Aharoune, A. Analytical solution of coupled heat and mass transfer equations during convective drying of biomass: Experimental validation. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 56, 1971–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalili, M.; Anca-Couce, A.; Zobel, N. On the uncertainty of a mathematical model for drying of a wood particle. Energy Fuels 2013, 27, 6705–6717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, G.V.; Nigay, N.A.; Syrodoy, S.V.; Gutareva, N.Y. Influence of biomass type on its characteristics of convective heating and dehydration. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 7118–7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, G.V.; Syrodoy, S.V.; Nigay, N.A.; Maksimov, V.I.; Gutareva, N.Y. Features of the processes of heat and mass transfer when drying a large thickness layer of wood biomass. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 498–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.