Abstract

Mechanical and thermoelectric performance of a SiGe thermoelectric module were investigated through finite element analysis. N-type and P-type SiGe thermoelectric materials were synthesized, and their mechanical and thermoelectric properties were experimentally measured. Thermal stress distributions within the SiGe module and the integrated “heat collector–module–heat sink” assembly are simulated, and the results were compared with the measured mechanical strength of the SiGe materials. The simulations show that among the three electrode structures evaluated—C/W/C sandwich, 0.5 mm W/C, and 0.1 mm W/C—the C/W/C sandwich configuration yields the lowest thermal stress. An inter-leg spacing of 0.5 mm also leads to reduced stress compared to a 0.1 mm gap. However, fully constraining the cold end or directly integrating the module with heat collection and dissipation components significantly increases thermal stress. The use of copper cooling plates induces higher stress than C-C plates, exceeding the tolerable strength of the materials. Simulation of a module with 28 SiGe legs (each 10 mm × 10 mm × 1.5 mm) predicts an output power of 7.42 W and a conversion efficiency of 7.11% at a hot-side temperature of 967 °C and a cold-side temperature of 412 °C.

1. Introduction

A thermoelectric module is an energy conversion device that directly converts thermal energy into electrical energy via the Seebeck effect [1,2]. It has significant applications in areas such as waste heat recovery [3,4,5,6], wearable devices [7] and nuclear power systems for deep-space exploration [8,9,10]. Structurally, a typical module comprises N-type and P-type thermoelectric legs interconnected by metal electrodes. During operation, a temperature difference is applied across the module—with the hot-side electrode at a high temperature and the cold-side electrode at a lower temperature—establishing a temperature gradient along the thermoelectric legs. Under such conditions, the mismatch in the coefficients of thermal expansion (CTE) among the N-type material, P-type material, and metal electrodes induces thermal stress. If this stress exceeds the bonding strength of the materials or interfaces, it may lead to crack initiation or even module failure [11,12,13].

Numerous studies have addressed thermal stress-related issues in thermoelectric modules, primarily attributing them to the CTE mismatch between materials. For instance, Kwang et al. [14] and Haizikraniotis et al. [15] reported that thermal cycling substantially degrades the performance of thermoelectric generators due to stress-induced cracking. Simulations by Hori et al. [16] on bismuth telluride modules revealed thermal stresses as high as 142.6 MPa under a temperature gradient, a direct consequence of CTE mismatch. This finding is further corroborated by the simulation works of Ravi et al. [17] and Venkatasubramanian et al. [18]. Beyond intrinsic material properties, the geometric design of a module is a critical factor governing thermal stress distribution. Studies have shown that the dimensions of insulating layers and electrodes significantly influence stress levels; Wang et al. [19] demonstrated that a thinner insulating layer reduces interlaminar stress, whereas Yu et al. [20] found that increasing the weld layer thickness effectively mitigates stress in bismuth telluride legs. Furthermore, Li et al. [21] proposed that a split structure for ceramic substrates, combined with thin substrates and thick electrodes, can alleviate thermal stress in skutterudite-based modules. The geometry of the thermoelectric legs themselves is another vital design parameter. Beker et al. [22] revealed that a tapered leg cross-section develops lower thermal stress than a conventional rectangular one. Similarly, Yan et al. [23] demonstrated that the interfacial stress in segmented modules can be optimized by adjusting the cross-sectional area ratio of the segments. Ugur et al. [24,25] systematically investigated the influence of leg geometry, dimensions, and spacing. They concluded that cylindrical and trapezoidal prism legs exhibit lower thermal stress levels compared to rectangular prism legs. Furthermore, thermal stress was found to escalate with increasing leg width and spacing but decrease with greater leg height. Wang et al. [26] found that the optimization directions for the mechanical and output performance of the studied Bi2Te3 thermoelectric module are generally opposing; thus, the optimal structure must strike a balance between mechanical properties and output performance. Collectively, these studies substantiate that strategic optimization of the module’s structure and dimensions is an effective approach to mitigating detrimental stress concentrations.

Silicon-germanium (SiGe) thermoelectric modules are high-performance devices that can operate at temperatures up to 1000 °C. They have been successfully implemented in Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs) for missions such as Voyager, Cassini, and Galileo [27,28,29]. In these systems, SiGe is typically configured as unicouple elements. To meet the growing demands of future applications—including RTGs, space nuclear reactors, and waste heat recovery systems—there is a need to develop multi-leg SiGe modules that offer higher output power density and more compact structures. Among various configurations, SiGe modules utilizing tungsten electrodes and graphite diffusion barriers exhibit excellent thermal stability, high power density, and structural integrity, positioning them as promising candidates for next-generation high-temperature thermoelectric systems [30].

In space nuclear power applications, SiGe thermoelectric modules will experience extreme temperature differentials, with the hot side reaching 1000 °C and the cold side maintained at 300 °C. Under such severe conditions, significant thermal stress arises, influenced by the module’s structural design. Therefore, the structure of thermoelectric module should be designed to minimize thermal stress. Moreover, in practical applications, thermoelectric modules are integrated into an assembled structure comprising a hot-side heat collector and a cold-side heat sink. The thermal stress distribution in this integrated system (heat collector–module–heat sink) differs from that in a standalone module, underscoring the need to evaluate thermomechanical behavior in a coupled configuration.

This study focuses on multi-leg SiGe thermoelectric modules with tungsten electrodes and a graphite diffusion barrier. To simulate and judge the stability of the structure, the mechanical properties of SiGe materials are measured. Using finite element simulation, we investigate the effects of three key structural parameters—electrode geometry, inter-leg spacing, and leg dimensions—on the magnitude and distribution of thermal stress and analyze the underlying mechanisms. We further identify optimal structural parameters that minimize thermal stress. Additionally, the thermomechanical response of the SiGe module within an assembled structure—comprising a molybdenum heat collector, the SiGe module, and a C-C composite heat sink—is examined. The thermoelectric output performance of the module is also evaluated.

2. Experimental Details

N-type and P-type SiGe alloys were synthesized via ball milling followed by hot pressing [31]. For preparation of P-type SiGe, powder mixtures of silicon (>99.99%, Aladdin, Shanghai, China), germanium (>99.99%, Aladdin), and boron (>99%, Alfa Aesar, Haverhill, MA, USA) were weighed according to the nominal compositions of Si0.8Ge0.2B0.0075 with total weight of 50 g. For preparation of N-type SiGe, powder mixtures of silicon (>99.99%, Aladdin), germanium (>99.99%, Aladdin), phosphorus (>99%, Alfa Aesar), and gallium phosphide (>99%, Alfa Aesar) were weighed according to the nominal compositions of Si0.79Ge0.2Ga0.0025P0.01 with a total weight of 50 g. The two kinds of powder mixture were transferred into two hardened steel jars sealed in an argon-filled glove box, respectively. The powder-to-ball mass ratio was 1:20. Ball milling was conducted in a planetary mill (Fritsch P5 PL, FRITSCH, Idar-Oberstein, Germany) at 400 rpm for 4 h, employing a cyclic routine of 10 min milling followed by 10 min pause to reduce overheating of the powder. The ball milled alloy powders were subsequently sintered in a cylindrical graphite die with an internal diameter of 50 mm under 60 MPa pressure at 1473 K by hot pressing for 40 min.

XRD patterns were collected using a Bruker D8 diffractometer with Cu-Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å) (Bruker, Karlsruhe, Germany). The as-prepared N- and P-type SiGe bulks were cut into bar-shaped and rectangular specimens for mechanical property evaluations, as illustrated in Figure 1. Bending strength and composing strength were carried out on a universal testing machine (INSTRON 5967, INSTRON, Norwood, MA, USA) equipped with a 5 kN load cell. Bending strength are measured by three-point bending test method using samples with dimension of 3 mm × 4 mm × 36 mm. Composing strength were measure using samples with dimension of 4 mm × 4 mm × 6 mm. Young’s modulus (E) and Poisson’s ratio (ν) are measured on the high-temperature resonant frequency and damping analyzer (RFDA-HTVP-1750C, IMCE, Leuven, Belgium) by the resonant frequency method using samples with dimensions of 30 mm × 40 mm × 3 mm. Each property was evaluated using five independent samples, and the reported results represent the average values.

Figure 1.

Pictures of SiGe samples for mechanical properties test: (a) bending strength; (b) compressive strength; (c) Young’s modulus (E) and Poisson’s ratio (ν).

The thermoelectric properties of the as-prepared N-SiGe and P-SiGe bulks were measured. Bar-shaped specimens (10 × 2 × 2 mm3) were used to measure the Seebeck coefficient (S) and electrical conductivity (σ) from room temperature to 1273 K in a helium atmosphere using a commercial Seebeck/resistivity measurement system (Cryoall, CTA-1100, Beijing, China). Thermal diffusivity (D) and specific heat (Cp) were obtained by the laser flash method (LFA 457, NETZSCH, Selb, Germany) on square plates (10 × 10 × 1.5 mm3). The total thermal conductivity (κ) was calculated via κ = D·Cp·ρ, where the density (ρ) was derived from the sample mass and geometric dimensions.

3. Phase Structure and Properties of the as Prepared N-SiGe and P-SiGe Thermoelectric Materials

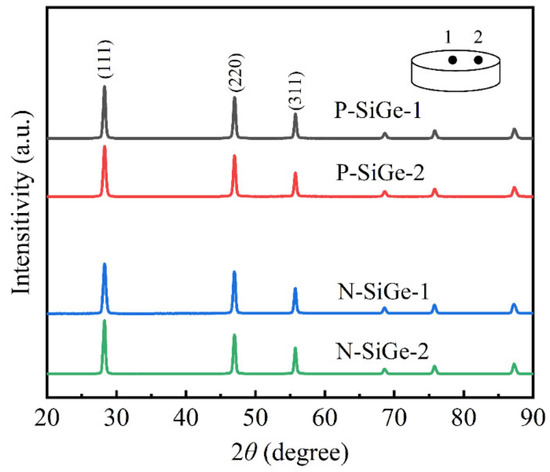

The XRD patterns in Figure 2 show that the obtained SiGe bulks are pure-phase polycrystalline solid solutions. The diffraction peaks at 28.2°, 47°, and 55.7° are assigned to the (111), (220), and (311) planes of silicon, respectively. The patterns from points 1 and 2 are identical, indicating that the bulks are homogeneous.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of N-SiGe and P-SiGe thermoelectric materials.

The bending strength of N-SiGe and P-SiGe are 168.7 MPa and 143.0 MPa, respectively, as shown in Figure 3a,b. The composing strength of N-SiGe and P-SiGe are 624.1 MPa and 504.8 MPa, respectively, as shown in Figure 3c,d. The Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio were measured as 150.5 GPa and 0.197 for the N-SiGe, and 144.6 GPa and 0.199 for the P-SiGe, respectively.

Figure 3.

Bending strength of (a) N-SiGe and (b) P-SiGe, and composing strength of (c) N-SiGe and (d) P-SiGe.

Figure 4 presents thermoelectric properties of the as-prepared N-SiGe and P-SiGe bulk. The electrical conductivity (σ), Seebeck coefficient (S), and thermal conductivity (κ) were used for power output simulation in COMSOL in the following section. Dimensionless figure of merit, ZT, is calculated by ZT = (S2σ/κ)T. The N-SiGe and P-SiGe achieved ZT of 1.1 and 0.68 @1073 K, which are comparable to those of the SiGe materials utilized in the Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG) of NASA’s Cassini mission [32].

Figure 4.

Thermoelectric properties of N-SiGe and P-SiGe: (a) electrical conductivity; (b) Seebeck coefficient; (c) thermal conductivity; (d) ZT.

4. Model and Simulation

4.1. Geometric Model

Finite element modeling and simulation were conducted using COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0 software. The investigated SiGe thermoelectric module consists of P-type and N-type SiGe legs, a graphite barrier layer (C), and tungsten electrodes (W). In this configuration, two rows of slab-shaped N-type and P-type legs are arranged alternately with gaps between them, and each pair is connected in series at the hot and cold ends via graphite barrier layer and tungsten electrodes, as illustrated in Figure 5. The cold-end surface of the SiGe legs is defined as the plane z = 0 mm.

Figure 5.

Geometric model of SiGe thermoelectric module: (a) A-s0.5-10 mm; (b) B-s0.5-10 mm; (c) C-s0.5-10 mm; (d) side, top, and exploded views of A-s0.5-10 mm.

To systematically analyze the influence of electrode structure, leg dimensions, and inter-leg spacing on thermal stress, three distinct electrode configurations were designed: Electrode A, a three-layer C/W/C structure with two 0.5 mm graphite layers and a 0.1 mm tungsten interlayer; Electrode B, a two-layer W/C structure composed of 0.5 mm tungsten and 1 mm graphite; and Electrode C, also a two-layer W/C structure but with 0.1 mm tungsten and 1 mm graphite. Additionally, two leg cross-sectional dimensions and legs numbers (10 mm in height × 10 mm in width × 1.5 mm in thickness × 28 legs, and 10 mm in height × 8.5 mm in width × 1.5 mm in thickness × 20 legs), and two leg spacing values (0.1 mm and 0.5 mm) were considered. These three variables were cross-combined to generate twelve unique module structures, the specific parameters of which are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

SiGe thermoelectric module and geometrical parameters.

The properties of the materials used in the model—including thermal conductivity (κ), electrical conductivity (σ), Seebeck coefficient (S), CTE (α), specific heat capacity (Cp), density (ρ), Young’s modulus (E), and Poisson’s ratio (ν)—are summarized in Table 2 for all key materials: P-SiGe and N-SiGe legs, the graphite barrier layer, tungsten electrodes, AlN insulator, molybdenum heat collector, as well as the C-C and copper heat sink. The properties of the N-type and P-type SiGe legs were obtained from experimental measurements (Figure 4, Section 3), while their CTE (α) and all properties for the remaining structural materials are sourced from the COMSOL material library.

Table 2.

Properties of materials in the model.

4.2. Governing Equations, Finite Element Modeling, and Boundary Conditions

The thermal stress distribution within the thermoelectric module and the assembled structure was analyzed using the “Thermoelectric Effect” multiphysics module in COMSOL Multiphysics 6.0, which couples the “Solid Mechanics” and “Heat Transfer in Solids” modules. The same “Thermoelectric Effect” interface was also utilized to evaluate the thermoelectric output performance of the SiGe module. The fundamental governing equations for thermal stress computation are given below.

The temperature distribution can be obtained by Equation (1)

The relationship between the displacement and strain can be expressed as

The relationship between stress and strain can be expressed as

Thermoelectric effect model of COMSOL software is used to simulate the process of converting thermal energy into electrical energy. Thermoelectric coupling governing equations are expressed as follows:

where the J is the current density, q is the heat flux, E is the electric field intensity and T is the absolute temperature.

The three-dimensional geometry was discretized with tetrahedral mesh elements, with a global element size ranging from 0.567 mm to 3.15 mm. Constant temperatures of Tcold = 412 °C and Thot = 967 °C were applied to the cold-side and hot-side electrode surfaces, with all other external surfaces defined as thermally insulated.

For the analysis of structural influence on thermal stress, the module was considered free of external mechanical loads, with all boundaries unconstrained. To investigate the effect of mechanical constraints, the cold-side surface of the cold electrode was fixed by restricting all translational displacements (i.e., UX = UY = UZ = 0 mm). All solutions for thermal stress were obtained under steady-state assumptions.

For the simulation of power output, the cold-side electrode was grounded (V = 0). All solutions for power output were obtained under steady-state assumptions.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. FE Mesh Independence Tests

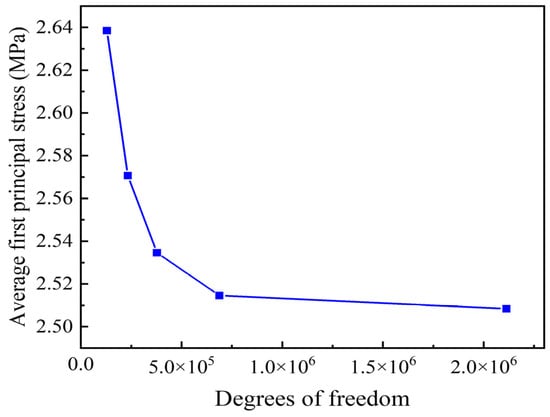

To evaluate mesh independence, the average first principal stress was computed across five discretization levels, with degrees of freedom (DOF) counts of 129,106, 232,701, 377,471, 687,296, and 2,113,021. As shown in Figure 6 and Table 3, the solution converged at 687,296 DOF, showing a mere 0.02% deviation from the result at 2,113,021 DOF and a 0.07% deviation from that at 377,471 DOF. Based on this, the mesh with 687,296 DOF was adopted to ensure accurate results while maintaining computational efficiency.

Figure 6.

Variation in the model’s average first principal stress with the number of degrees of freedom.

Table 3.

Results of FE meshes independence tests performed using the FEM-based models.

5.2. Influence of Electrode Structure on Thermal Stress in SiGe Thermoelectric Modules

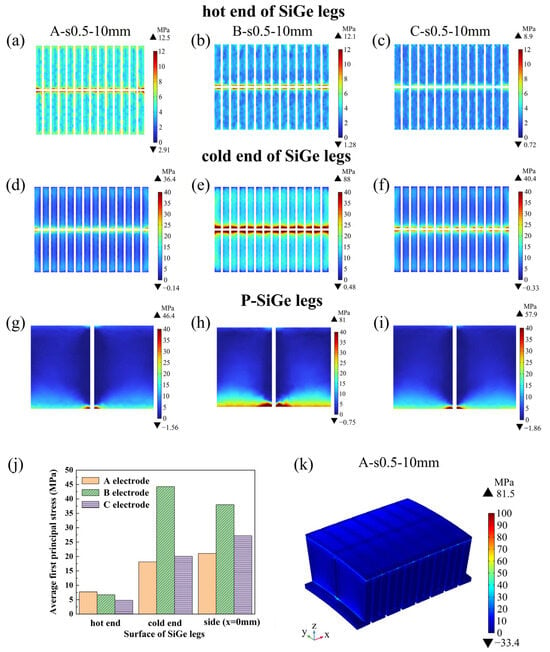

Figure 7 illustrates the distribution of the first principal stress on the hot end, cold end, and side surfaces of the SiGe thermoelectric legs for three module configurations with different electrode structures (A-s0.5-10 mm, B-s0.5-10 mm, and C-s0.5-10 mm) under a temperature difference and without constraints. In all three configurations, the average thermal stress on the hot-end surface of the SiGe legs is significantly lower than that on the cold-end surface.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the first principal stress in SiGe thermoelectric modules with different electrode designs. First principal stress distribution on (a–c): The hot-end surface of SiGe legs in the (a) A-s0.5-10 mm, (b) B-s0.5-10 mm, and (c) C-s0.5-10 mm modules. (d–f) The cold-end surface of SiGe legs in the (d) A-s0.5-10 mm, (e) B-s0.5-10 mm, and (f) C-s0.5-10 mm modules. (g–i) The side surface of the P-SiGe leg in the (g) A-s0.5-10 mm, (h) B-s0.5-10 mm, and (i) C-s0.5-10 mm modules. (j) Average first principal stress on the studied surfaces of the SiGe legs. (k) Total displacement in the thermoelectric modules.

Regarding the hot-end surface of the SiGe legs, the module with Type A electrodes exhibits a higher average thermal stress of 4.9 MPa. In contrast, for the cold end and side surfaces, the average thermal stress in the module with Type B electrodes of 15.6 MPa is notably higher than in those with Type A (8.5 MPa) or Type C electrodes (9.3 MPa), as shown in Figure 7j.

In most regions, the thermal stress remains below 10 MPa. Elevated stress on the end surfaces of the SiGe legs is primarily concentrated along the edges adjacent to the gaps between the two columns of legs. From Figure 7k, this concentration occurs because, under free deformation conditions, the hot-end electrodes arch upward, while the cold-end electrodes experience less pronounced curvature due to their lower temperature. This differential deformation induces tensile forces at the cold-end surfaces and inner corners of the thermoelectric legs, leading to higher stress levels. Furthermore, as the thickness of the tungsten layer increases, the deformation mismatch between the hot and cold ends becomes more pronounced, further exacerbating the stress.

Among the three configurations, the module with Type B electrodes demonstrates the highest average thermal stress, whereas the module with Type A electrodes shows the lowest.

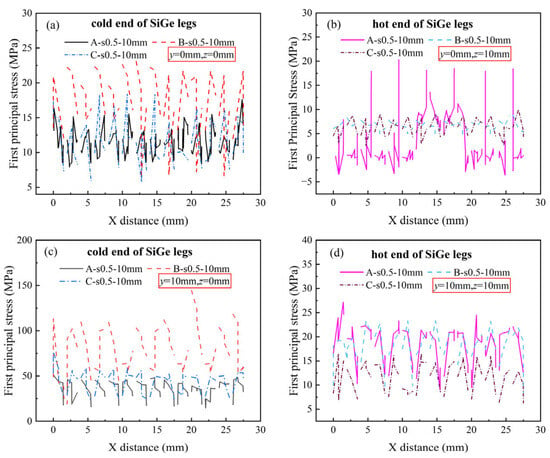

To further compare the influence of electrode structures on thermal stress, the distribution curve of the first principal stress was extracted along the edges of the thermoelectric legs where stress concentration is most critical, as shown in Figure 8. Figure 9 shows the first principal stress distribution along the X-direction edges at the hot and cold ends of the SiGe legs. The breaks in the data line at x = 1.5, 3.5, 5.5, …, 25.5 mm correspond to the spacing between individual legs. The thermal stress at the hot end is consistently lower than that at the cold end, and the stress at the cold-end edges of the SiGe legs in the Type B electrode module is significantly higher than in the Type A and Type C modules.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram of the stress extraction locations.

Figure 9.

First principal stress along the X-axis edges of SiGe legs for three module designs (A, B, C: s0.5-10 mm) at specific coordinates: (a) cold end (y = 0 mm, z = 0 mm); (b) hot end (y = 0 mm, z = 10 mm); (c) cold end (y = 10 mm, z = 0 mm); (d) hot end (y = 10 mm, z = 10 mm); the stress extraction location is annotated by the red box.

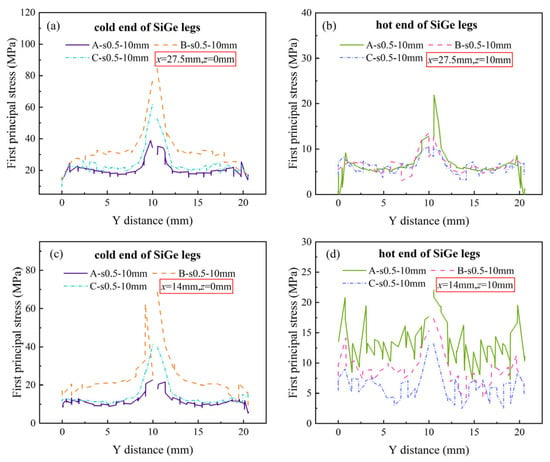

As shown in Figure 10, stress distribution results along the Y-direction also confirm that the thermal stress at the cold end of the thermoelectric legs exceeds that at the hot end. Moreover, the stress at the leg ends in the Type B electrode module is markedly higher than in the Type A and Type C modules. The breaks at y = 10 mm to 10.5 mm in the line correspond to the gaps between two rows of SiGe legs. At the cold-end corners of the gap between the two rows of thermoelectric legs—specifically at coordinates (y = 10 mm/10.5 mm, z = 0 mm)—a stress concentration region is observed.

Figure 10.

First principal stress along the Y-axis edges of SiGe legs for three module designs (A, B, C: s0.5-10 mm) at specific coordinates: (a) cold end (x = 27.5 mm, z = 0 mm); (b) hot end (x = 27.5 mm, z = 10 mm); (c) cold end (x = 14 mm, z = 0 mm); (d) hot end (x = 14 mm, z = 10 mm); the stress extraction location is annotated by the red box.

Figure 11 presents the thermal stress distribution along the Z-direction of the thermoelectric module. The stress within the thermoelectric legs is uniform and relatively low, measuring ≤ 2.7 MPa, whereas at the SiGe/graphite and graphite/tungsten interfaces, the thermal stress increases to 10–25 MPa. This interfacial stress concentration is mainly caused by the mismatch in the CTE between the dissimilar materials.

Figure 11.

First principal stress along Z-directions (x = 0 mm, y = 0 mm) edge of SiGe leg in A-s0.5-10 mm, B-s0.5-10 mm, and C-s0.5-10 mm thermoelectric modules, the stress extraction location is annotated by the red box.

In summary, the Type B electrode configuration yields the highest overall thermal stress, while the Type A electrode configuration results in the lowest. Therefore, to mitigate thermal stress in SiGe thermoelectric modules, electrode structures such as Type A or Type C—specifically those with a sandwich configuration or thinner tungsten layers—are recommended.

To further mitigate thermal stress at the inner corner edge between the two rows of thermoelectric legs (located at y = 10 mm/10.5 mm, z = 0 mm), slits were introduced into the Type A electrode along the x-axis at y = 10 mm/10.5 mm, spanning either z = −1.1 to 0 mm or z = 10 to 11.1 mm. As shown in Figure 12, these slits reduce the constraint imposed by the electrode plate on the inner edge of the thermoelectric legs. Consequently, the stress at the cold-end surface declines from 27 MPa to 12–16 MPa.

Figure 12.

Effect of electrode slit on thermal stress in A-s0.5-10 mm module: (a) schematic diagram of slitted thermoelectric module; (b) average first principal stress along X direction.

5.3. Influence of Inter-Leg Spacing on the First Principal Stress in SiGe Thermoelectric Modules

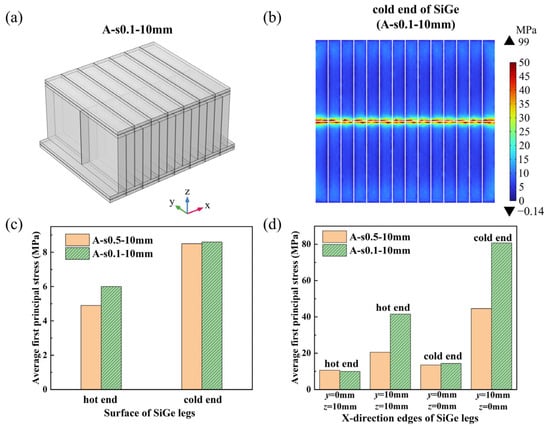

This section examines the influence of the gap between SiGe legs on the thermal stress within the module. The results indicate that reducing the inter-leg spacing from 0.5 mm to 0.1 mm leads to an increase in thermal stress across nearly all surfaces and directions of the SiGe legs, as shown in Figure 13. Specifically, Figure 13b reveals that the thermal stress is concentrated along the X-direction edges adjacent to the gap between the two leg rows, at the location y = 10 mm, z = 10 mm. Furthermore, as presented in Figure 13d for the average first principal stress along the X-direction edges, the reduction in spacing causes the thermal stress at the inner edge of the cold end (approximately between y = 10–10.5 mm, z = 0 mm) to double. This significant stress escalation can be attributed to the larger deformation angle induced by the narrower gap between the two rows of legs.

Figure 13.

Effect of inter-leg spacing on thermal stress of SiGe thermoelectric module: (a) schematic diagram of A-s0.1-10 mm thermoelectric modules; (b) first principal stress distribution on the cold-end surface of SiGe legs in the A-s0.1-10 mm module; (c) average first principal stress on the hot and cold-end surfaces of SiGe legs; (d) average first principal stress on the X-direction edges of SiGe legs.

5.4. Influence of SiGe Leg Dimensions on the First Principal Stress in SiGe Thermoelectric Modules

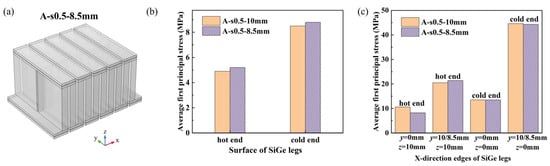

The simulation results in this section reveal that the thermal stress within the module is insensitive to variations in both the width and the number of the thermoelectric legs. As illustrated in Figure 14, which depicts the average first principal stress on various surfaces and edges. The thermal stress is nearly identical for leg widths of 8.5 mm and 10 mm, as well as for leg counts of 20 and 28.

Figure 14.

Effect of leg’s dimension on thermal stress of SiGe thermoelectric module: (a) schematic diagram of A-s0.5-8.5 mm thermoelectric modules; (b) average first principal stress on the hot and cold end surfaces of SiGe legs; (c) average first principal stress on the X-direction edges of SiGe legs.

To thoroughly validate the influence of various structural parameters, a thermal stress simulation analysis was conducted on 12 module configurations formed by cross-combining three types of parameters: Type A, B, and C electrodes; SiGe inter-leg spacings of 0.1 mm and 0.5 mm; and thermoelectric leg widths of 8.5 mm and 10 mm. The results, summarized in Table 4, align with the findings discussed above. The thermal stress in all configurations remains below the measured bending strengths of both N-SiGe (168.7 MPa) and P-SiGe (143.0 MPa). However, modules with Type A or Type C electrode structures and an inter-leg spacing of 0.5 mm exhibit lower thermal stress. In contrast, those with Type B electrode structures or a reduced inter-leg spacing of 0.1 mm show significantly higher stress levels. The width of the thermoelectric legs, whether 8.5 mm or 10 mm, is confirmed to have a relatively minor influence on thermal stress.

Table 4.

Average first principal stress in SiGe legs (Mpa).

5.5. Influence of Constraint Conditions on Thermal Stress

This section investigates the thermal stress distribution in the A-s0.5-10 mm thermoelectric module under fixed constraints applied to the cold-side electrode surface. As shown in Figure 15, when the cold-side electrode surface (i.e., the plane at z = −1.1 mm) is fully constrained, the resulting stresses in the X-, Y-, and Z-directions increase significantly compared to the free-state condition. Fixing the cold-side electrode surface strongly restricts the thermal expansion of both the thermoelectric legs and the electrodes under high-temperature operation. Furthermore, due to the complete constraint at the cold side, the increase in thermal stress at the cold-end surface of the SiGe legs is more pronounced than at the hot end, reaching 37.8 MPa. The maximum tensile stress remains concentrated near the cold-end edges between the two rows of thermoelectric legs, specifically at y = 10 mm or 10.5 mm, z = 0 mm, reaching about 150 MPa, which is close to the bending stress of SiGe legs.

Figure 15.

Thermal stress in the A-s0.5-10 mm module with the cold side fixed: (a) first principal stress distribution on cold-end surface of SiGe legs; (b) average first principal stress of hot and cold-end surfaces of SiGe legs.

These findings indicate that the module should not be fully constrained in practical assembly and operation, as such fixation can increase thermal stress levels capable of causing damage at interfaces and adjacent regions.

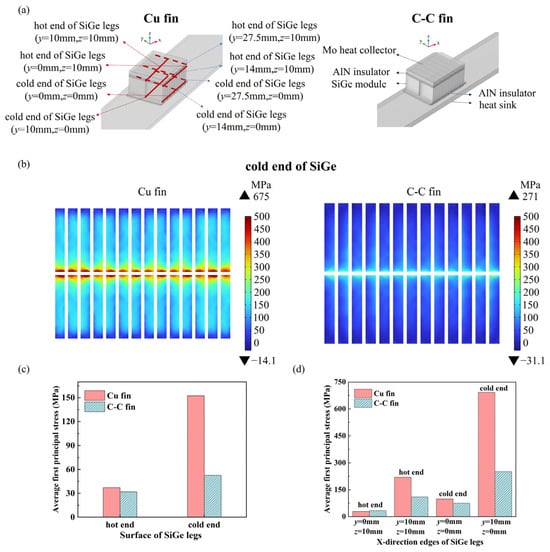

5.6. Thermal Stress Simulation Analysis of “Heat Collector–SiGe Module–Heat Sink” Assembly

In practical applications, the SiGe module is integrated with insulating layers and heat exchange components to form a complete thermoelectric assembly. This section analyzes the thermal stress distribution within such an assembly. As illustrated in Figure 16a, the assembly consists of a SiGe thermoelectric module, AlN insulating plates (27.5 mm × 20.5 mm × 0.5 mm) at both the hot and cold sides, a molybdenum alloy heat collector (27.5 mm × 20.5 mm × 2 mm) at the hot side, and either a C–C (300 mm × 26 mm × 3.3 mm) or copper (300 mm × 26 mm × 2 mm) heat sink at the cold side. The hot surface of the Mo heat collector and the cold surface of the heat sink are maintained at 967 °C and 412 °C, respectively. The thermal stress distribution was simulated under the condition where the cold-side surface of the heat sink is fully constrained.

Figure 16.

Thermal stress in SiGe legs in the “Mo collector-A-s0.5-10 mm module-heat sink” assembly: (a) schematic diagram of the assembly and stress extraction locations; (b) first principal stress on cold-end surface of SiGe legs; (c) average first principal stress of hot and cold end surfaces of SiGe legs; (d) average first principal stress of X-direction edges of SiGe legs.

Results show that when the SiGe module is directly bonded to the Mo heat collector and either the C–C or Cu heat sink, the thermal stress in the SiGe legs increases markedly compared with single SiGe module, as shown in Figure 16. Due to the greater mismatch in the CTE between copper and SiGe compared to that between C–C and SiGe, the assembly with a Cu heat sink exhibits substantially higher thermal stress than that with a C–C heat sink. The thermal stress at cold end of SiGe in “Mo collector–SiGe Module–Cu Heat Sink” surpass the bending strength of SiGe legs. Under the applied temperature difference, the thermal stress levels in the SiGe module can be ranked as follows: assembly with Cu heat sink > assembly with C–C heat sink > single SiGe module with constrained cold-side electrode > unconstrained single SiGe module. Therefore, to minimize thermal stress, a C–C heat sink is recommended for assembly fabrication, along with the incorporation of a stress buffer layer.

5.7. Output Performance of SiGe Thermoelectric Modules

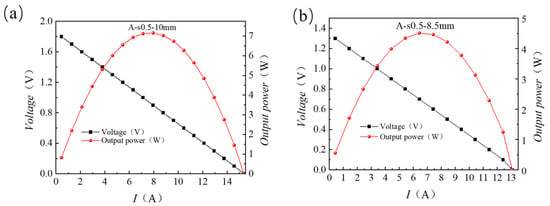

The output performance of two SiGe thermoelectric modules, A-s0.5-10 mm and A-s0.5-8.5 mm, was evaluated under hot-side and cold-side temperatures of 967 °C and 412 °C, respectively. As summarized in Figure 17, the A-s0.5-10 mm module achieved an open-circuit voltage of 1.85 V, a maximum output power (Pout) of 7.42 W, a hot-side heat inflow of 104.38 W, and a corresponding conversion efficiency of 7.11%. In comparison, the A-s0.5-8.5 mm module exhibited an open-circuit voltage of 1.32 V, a maximum Pout of 4.51 W, a hot-side heat inflow of 61.97 W, and a conversion efficiency of 7.28%.

Figure 17.

Output IV curves of (a) A-s0.5-10 mm and (b) A-s0.5-8.5 mm modules.

To assess the accuracy of the simulation, the Pout calculated in this section is compared with the computational and experimentally measured values reported in the SP100 space reactor power source program [33]. In the SP100 program, a SiGe thermoelectric module with a cross-sectional area of 6.45 cm2 and a leg height of 6.6 mm exhibited a calculated Pout of 9.2 W and an experimentally measured Pout of approximately 7.2 W at a temperature difference (ΔT) of about 500 K. The corresponding power densities per unit area are listed in Table 5. Given that Pout is proportional to ΔT2 and inversely proportional to the leg height, and taking into account minor variations in material properties, the Pout calculated in this work shows good agreement with the value reported in the SP100 program. This consistency supports the accuracy of the performance simulation presented in this study.

Table 5.

Power density for SiGe thermoelectric modules.

6. Conclusions

Thermal stress generated in thermoelectric modules under temperature gradients, primarily due to mismatches in the coefficients of thermal expansion among constituent materials, poses a critical challenge to module performance, reliability, and service life. This study measured mechanical properties of SiGe thermoelectric materials and systematically investigated the influence of structural parameters on the magnitude and distribution of thermal stress in SiGe thermoelectric modules using finite element simulations. The results will help to choose structures with low thermal stress and enhanced reliability.

Key factors affecting thermal stress include the electrode structure, inter-leg spacing, leg dimensions, and the configuration of the “heat collector–SiGe module–heat sink” assembly. The main findings are summarized as follows:

- (1)

- The bending strength, compressive strength, Young’s modulus, and Poisson’s ratio were measured to be 168.72 MPa, 624.1 MPa, 150.5 GPa, 0.197 for the N-SiGe, and 143.0 MPa, 504.78 MPa, 144.6 GPa, 0.199 for the P-SiGe.

- (2)

- Modules with a C/W/C-type electrode structure exhibit lower first principal stress compared to those with a W/C bilayer electrode.

- (3)

- An inter-leg spacing of 0.5 mm leads to significantly lower first principal stress than a spacing of 0.1 mm.

- (4)

- The dimensions of the plate-shaped SiGe legs have a minor influence on thermal stress. Modules with leg sizes of 8.5 × 10 × 1.5 mm3 and 10 × 10 × 1.5 mm3 show comparable stress levels.

- (5)

- Among the 12 configurations analyzed, the structure with a C/W/C electrode and an inter-leg spacing of 0.5 mm (i.e., A-s0.5-10 mm or A-s0.5-8.5 mm) exhibits the lowest thermal stress. In this configuration, the maximum first principal stress on the hot-end surface of the SiGe legs is 12.5 MPa (average: 7.705 MPa), while on the cold-end surface, it reaches 36.4 MPa (average: 18.13 MPa). Thermal stress in all modules remains below the bending strength of SiGe, and the module delivers a maximum output power of approximately 7.42 W.

- (6)

- When integrating the SiGe module into a thermoelectric assembly with a Mo heat collector and a heat sink, a C–C heat sink with a CTE close to that of SiGe is recommended. Incorporating a stress buffer layer between the module and the heat exchange plates further reduces thermal stress.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.L. and M.M.; Methodology, J.L.; Formal Analysis, Z.L. and J.L.; Investigation, Z.L., H.Y., X.C. and H.J.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Z.L.; Writing—Review and Editing, J.L.; Validation, Y.Z. and M.M.; Resources, Q.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (12075214), Presidential Foundation of CAEP (YZJJZQ2022004) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (12105265).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have influenced the work reported in this paper.

References

- Xiao, Y.; Zhao, L.D. Seeking new, highly effective thermoelectrics. Science 2020, 367, 1196–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zebarjadi, M.; Esfarjani, K.; Dresselhaus, M.S.; Ren, Z.F.; Chen, G. Perspectives on thermoelectrics: From fundamentals to module applications. Energy Environ. Sci. 2012, 5, 5147–5162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Champier, D. Thermoelectric generators: A review of applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2017, 140, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoui, M.A.; Bentouba, S.; Stocholm, J.G.; Bourouis, M. A review on thermoelectric generators: Progress and applications. Energies 2020, 13, 3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi, F.; Holagh, S.G.; Chitsaz, A. Thermoelectric generators: A comprehensive review of characteristics and applications. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 201, 117793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.B.; Zeng, J.L.; Liu, X.; Su, C.Q.; Xiong, X.; Wang, Y.P. Numerical simulation of a multi-tube automotive thermoelectric generator for heat transfer and power generation performance. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2025, 70, 106091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, M.; He, Z.; Zhu, J.; Ji, Y.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, M.; Zong, P. Flexible thermoelectric BiSbTe/carbon paper/BiSbTe sandwiches for bimode temperature-pressure sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2024, 34, 2414660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D.M. Applications of nuclear-powered thermoelectric generators in space. Appl. Energy 1991, 40, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, G.L. Mission interplanetary: Using radioisotope power to explore the solar system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2008, 49, 382–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.M.; Wang, C.L.; Zhang, D.L.; Tian, W.X.; Su, G.H.; Qiu, S.Z. Thermoelectric performance study on a heat pipe thermoelectric generator for micro nuclear reactor application. Int. J. Energy Res. 2021, 45, 12301–12316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Zhang, G.; Zhang, X.; Ji, J.; Li, G.; Zhao, X. Recent development and application of thermoelectric generator and cooler. Appl. Energy 2015, 143, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.S.; Seo, W.S.; Choi, D.K. Prediction of reliability on thermoelectric module through accelerated life test and physics-of-failure. Electron. Mater. Lett. 2011, 7, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barako, M.T.; Park, W.; Marconnet, A.M.; Asheghi, M.; Goodson, K.E. Thermal cycling, mechanical degradation, and the effective figure of merit of a thermoelectric module. J. Electron. Mater. 2012, 42, 372–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, K.H.; Choi, S.M.; Kim, K.H.; Choi, H.S.; Seo, W.S.; Kim, I.H.; Lee, S.; Hwang, H.J. Power-generation characteristics after vibration and thermal stresses of thermoelectric unicouples with CoSb3/Ti/Mo(Cu) interfaces. J. Electron. Mater. 2015, 44, 2124–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzikraniotis, E.; Zorbas, K.T.; Samaras, I.; Kyratsi, T.; Paraskevopoulos, K.M. Efficiency study of a commercial thermoelectric power generator (TEG) under thermal cycling. J. Electron. Mater. 2010, 39, 2112–2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Y.; Kusano, D.; Ito, T.; Sasaki, K. Analysis on thermo-mechanical stress of thermoelectric module. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, Baltimore, MD, USA, 29 August–2 September 1999; pp. 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, V.; Firdosy, S.; Caillat, T.; Brandon, E.J. Thermal expansion studies of selected high-temperature thermoelectric materials. J. Electron. Mater. 2009, 38, 1433–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto, M.A.; Venkatasubramanian, R. ANSYS-based detailed thermo-mechanical modeling of complex thermoelectric power designs. In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, Clemson, SC, USA, 19–23 June 2005; pp. 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.L.; Cui, Y.J. Transient inter laminar thermal stress in multi-layered thermoelectric materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2017, 110, 55–66. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, Y.; Kong, L.; Zhu, Q.S.; Zhu, H.J.; Wang, H.Q.; Guan, J.L.; Yan, Q. Thermal stress analysis of a segmented thermoelectric generator under a pulsed heat source. J. Electron. Mater. 2020, 49, 4392–4403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.W.; Huang, H.; Liu, R.H.; Song, Q.; Bai, S.Q.; Chen, L.D. Influence of structural factors on thermal stress in skutterudite-based thermoelectric module. Funct. Mater. Lett. 2021, 14, 2151013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilbas, B.S.; Akhtar, S.S.; Sahin, A.Z. Thermal and stress analyses in thermoelectric generator with tapered and rectangular pin configurations. Energy 2016, 114, 52–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Yi, L.; Xu, H.; Huang, S.; Song, K.; Pan, C.; Jiang, J. Interfacial thermal stresses of segmented thermoelectric generators. J. Therm. Stresses 2023, 46, 574–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturun, U.; Erermis, K.; Mossi, K. Effect of various leg geometries on thermo-mechanical and power generation performance of thermoelectric devices. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2014, 73, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erturun, U.; Erermis, K.; Mossi, K. Influence of leg sizing and spacing on power generation and thermal stresses of thermoelectric devices. Appl. Energy 2015, 159, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zong, Y.; Su, W.; Wang, C.; Wang, H. Output and mechanical performance of thermoelectric generator under transient heat loads. Renew. Energy 2024, 222, 119847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Genk, M.S.; Saber, H.H.; Caillat, T. Efficient segmented thermoelectric unicouples for space power applications. Energy Convers. Manag. 2003, 44, 1755–1772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Schierning, G.; Nielsch, K. Thermoelectric modules: A review of modules, architectures, and contact optimization. Adv. Mater. Technol. 2018, 3, 1700256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freer, R.; Powell, A.V. Realising the potential of thermoelectric technology: A Roadmap. J. Mater. Chem. C 2020, 8, 441–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demuth, S.F. SP100 space reactor design. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2003, 42, 323–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Han, J.; Jiang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, X. Effect of synthesis procedure on thermoelectric property of SiGe alloy. J. Electron. Mater. 2018, 47, 4579–4584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughin, S.; Nakahara, J.F.; Centurioni, D.X.; Cook, B.A.; Harringa, J.L. Fabrication of improved SiGe alloys for an 18-couple module test. AIP Conf. Proc. 1995, 316, 98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley, E.; Klee, P.; Hanson, J.; Nakahara, J. Life Testing of Conductively Coupled Thermoelectric Cells. Final Report for Task 11; General Electric Co.: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.