Abstract

This paper presents an integrated approach to the structural decomposition of concurrent control systems using exact transversal hypergraphs (XT-hypergraphs). The proposed method combines formal properties of XT-hypergraphs with invariant-based Petri net analysis to enable automatic partitioning of complex, concurrent specifications into deterministic and independent components. The approach focuses on preserving behavioral correctness while minimizing inter-component dependencies and computational complexity. By exploiting the uniqueness of minimal transversal covers, reducibility, and structural stability of XT-hypergraphs, the method achieves a deterministic decomposition process with polynomial-delay generation of exact transversals. The research provides practical insights into the construction, reduction, and classification of XT structures, together with quality metrics evaluating decomposition efficiency and structural compactness. The developed methodology is validated on representative real-world control and embedded systems, showing its applicability in deterministic modeling, analysis, and implementation of concurrent architectures. Future work includes the integration of XT-hypergraph algorithms with adaptive decomposition and verification frameworks to enhance scalability and automation in modern system design and integration with currently popular AI and machine learning methods.

1. Introduction

The design, analysis, and implementation of concurrent discrete event systems (DESs) remain central challenges in modern computer engineering, particularly within embedded systems, cyber-physical systems (CPSs), distributed controllers, and industrial automation [1,2,3,4]. As system architectures continue to increase in scale and heterogeneity, their behavioral models exhibit highly nontrivial concurrency patterns and intricate synchronization mechanisms. These characteristics inevitably lead to the well-known state-space explosion, which severely limits the applicability of classical verification and design workflows. Ensuring determinism, safety, liveness, and performance in such systems requires mathematically rigorous methodologies capable of handling both structural and temporal complexity in a principled manner [5,6].

Among the available modeling formalisms, Petri nets (PNs) provide a well-established and expressive framework for capturing causal dependencies, concurrency, resource conflicts, and synchronization constraints [7,8]. However, direct manipulation of large-scale Petri net models is computationally prohibitive, highlighting the need for systematic structural reductions. A particularly effective strategy is the structural decomposition of a given PN into a minimal set of sequential subnets often referred to as state-machine components (SMCs) or automaton-type subnets. Each such component represents a strictly sequential subsystem, enabling independent reasoning, modular synthesis, and scalable hardware implementation, for example in FPGA- or ASIC-based control architectures.

Despite its conceptual appeal, the determination of an optimal decomposition is intrinsically difficult. Classical methods based on undirected graph theory, such as concurrency graph coloring or maximal clique detection, exhibit NP-complete worst-case behavior and do not scale to large, industrial-grade systems [9,10]. Consequently, practical solutions often resort to polynomial-time heuristics that forfeit optimality guarantees.

To transcend the inherent limitations of graph-based approaches, recent research has introduced the use of hypergraph representations for Petri nets, providing a qualitatively richer abstraction of concurrency relations. In a hypergraph, a single hyperedge may connect an arbitrary number of vertices, naturally encoding sets of places that may be concurrently marked. This shift in representational paradigm enables the formulation of decomposition as a problem of computing exact transversals in an associated hypergraph. A key theoretical insight is that a valid SMC corresponds precisely to a set of places containing exactly one representative for each global state equivalence class, which is equivalent to identifying an exact transversal [11,12,13].

A major breakthrough in this context is the identification of the subclass of exact-transversal hypergraphs (XT-hypergraphs), characterized by the property that every minimal transversal is also exact. For XT-hypergraphs, minimal exact transversals can be enumerated with polynomial delay, reducing the complexity of the decomposition problem from exponential to, in the worst case, cubic with respect to the hypergraph size. Empirical results demonstrate that XT-based decomposition achieves optimal solutions while outperforming graph-coloring-based methods by nearly two orders of magnitude. Moreover, the integration of reduction techniques such as the fast reduction algorithm (FRA) significantly increases the likelihood that the underlying selection hypergraph belongs to the XT class, enabling polynomial-time exact computation for a broad set of practical Petri net models.

Complementing these structural techniques, the temporal behavior of concurrent systems may be rigorously analyzed using (max, +) algebra. Within this algebraic framework, fundamentally nonlinear synchronization phenomena are recast as linear recurrences over the (max, +) semiring. The (max, +) algebra formalism provides a powerful analytical framework for deriving firing schedules, evaluating throughput, computing cycle times, and establishing timing invariants in systems modeled by Petri nets or digital concurrent automata. Its ability to linearize synchronization makes it indispensable in the study of performance-critical CPSs, manufacturing automation, and time-constrained embedded controllers [4,14,15].

The practical relevance of these theoretical foundations is amplified by the availability of specialized verification and synthesis environments. The Hippo system developed with an emphasis on computational efficiency implements XT-class verification, exact-transversal enumeration via dancing links (DLX), and analysis of concurrency and sequentiality relations using c-exact hypergraphs. Complementary toolsets such as IOPT-Tools provide PNML-based visualization, symbolic analysis, and interactive simulation capabilities [4]. When used jointly, these environments offer a robust, industrial-grade workflow for model-driven design, ensuring correctness and minimizing the risk of specification errors.

In summary, the increasing structural and temporal complexity of contemporary concurrent systems necessitates the adoption of advanced mathematical frameworks that simultaneously provide expressive modeling capabilities and tractable computational properties. Hypergraph-based structural decomposition, particularly within the XT-hypergraph paradigm and (max,+) algebra, jointly constitute a rigorous and computationally efficient methodological foundation for the systematic design, verification, and hardware-oriented implementation of large-scale Petri-net-based systems [16,17,18].

In light of the above discussion, the contribution of the paper is twofold.

- To formalize structural decomposition techniques grounded in XT-hypergraph theory, enabling the derivation of minimal sequential covers with polynomial computational effort;

- To integrate (max, +) algebra as a complementary analytical framework, providing linearized temporal semantics for performance evaluation and synchronization-driven control design in concurrent DESs.

2. Problem Formulation

Concurrent control systems—including embedded, cyber-physical, and distributed systems—are commonly modeled using formalisms such as PN. Although these models offer valuable properties such as analysability in terms of safeness, liveness, determinism, and reachability, their practical applicability in hardware-oriented system design remains limited due to several factors:

- State space explosion in the presence of concurrency and branching structures [19];

- Non-determinism resulting from unresolved conflicts among transitions [10];

- Difficulty in directly mapping formal models to hardware implementations, particularly in FPGA or distributed platforms [20].

Consequently, the formal and efficient decomposition of concurrent systems modeled by PNs while preserving semantic correctness, deterministic execution, and manageable implementation complexity, remains an open research problem. Traditional approaches, based on comparability graphs, structural decomposition (e.g., SMCs), or classical net transformations, suffer from exponential growth in the number of components or execution paths when applied to systems with significant concurrency.

When designing a discrete system, it often happens that the size of the system exceeds the limits imposed by the dimensions of the prototyped device. The standard approach in such a case is to divide it into a series of subsystems that cooperate with each other. Parallel decomposition is an important process, as it allows the control program to be divided into automaton-type subnetworks. From a general point of view, it is essentially an optimization method that facilitates the design process. Petri nets are a widely used mathematical framework that enables the modeling of discrete systems, and the entire design process is facilitated by their structure based on places and transitions.

This paper proposes the use of XT-hypergraphs(exact transversal hypergraphs) as a formal tool for representing concurrency in discrete systems. An XT-hypergraph enables precise modeling of interdependent transitions and facilitates the derivation of minimal transversal sets that deterministically resolve conflicts without the need to explore all possible interleavings.

The core research question addressed in this article is as follows:

How can the structural properties of XT-hypergraphs be used to enable formal, deterministic, and implementation efficient decomposition of concurrent control systems modeled by Petri nets, in such a way that the resulting architecture minimizes the number of control components (SMCs) which simplifies execution logic.

To address this question, the article presents the following:

- A formal definition of XT-hypergraphs derived from the incidence matrix of a Petri net;

- An algorithm for computing minimal transversals that preserve determinism;

- Experimental validation on representative real-world control systems.

The results demonstrate that the proposed XT-based approach not only preserves behavioral correctness but also reduces hardware resource usage and implementation complexity (only the SMCs required to cover the base net are implemented). Moreover, the XT formalism establishes a foundation for future research in automatic decomposition, runtime adaptation, and integration with artificial intelligence techniques.

3. Definitions

This chapter allows for familiarization with the formal definitions of mathematical tools used: Petri Nets, Hypergraphs, (max, +) algebra.

3.1. Petri Nets

Definition 1.

A classical Petri netis a tuple:

where:

- P is a finite set of places,

- T is a finite set of transitions,

- is the flow relation,

- is the arc weight function,

- is the initial marking [21,22].

Definition 2.

A timed Petri net is a Petri net extended with a timing function

assigning deterministic firing delays to transitions [23,24].

Definition 3.

A stochastic Petri net is a Petri net equipped with a firing rate function

where transition firings follow stochastic processes, typically exponential distributions [25,26].

Definition 4.

A random Petri net generalizes stochastic Petri nets by allowing arbitrary probability distributions to be associated with transition firing times [27].

Definition 5.

A functional (interpreted) Petri net is a Petri net extended with a labeling function

where denotes a set of functions, actions, or guards associated with transitions, enabling integration with control logic and data processing [28].

These extensions provide increasing expressive power for modeling temporal behavior, uncertainty, and functional interactions in complex discrete-event and cyber-physical systems.

Definition 6.

The state of a Petri net , called marking, which can be seen as a distribution of tokens in the net places. A place is marked when it contains one (or more) token.

Definition 7.

A transition t is live if from any marking of Petri Net it is possible to fire [19].

Definition 8.

A place is safe if there is no reachable marking M such that the place contains more than one token:

Definition 9.

A Petri net is safe when all its places are safe (have at most one token for a given marking) [19].

Based on the Definitions 7 and 8, the following key assumptions were adopted for the implementation of the proposed algorithm:

- Assumption 1: The Petri net under consideration must be live.

- Assumption 2: The Petri net under consideration must be safe.

Assumption 1 The Petri net under consideration must be live, meaning there is no marking in which any transition cannot fire. This excludes the possibility of the network flow becoming deadlocked.

Assumption 2 The Petri net under consideration must be safe, meaning that each place can have at most one token.

The result of decomposition is SMCs; therefore, it is necessary to establish a formal definition of a subnet in the following form:

Definition 10.

A state machine component S of a Petri net is such a coherent subnet of it

- such that ,

- ,

- , .

The above definition shows that a state machine component (SMC) is nothing more than a given subnet of the main Petri net.

Definition 11.

The incidence matrix of a Petri net , where and , is a matrix of integers, in which each element is defined as [21]:

Definition 12.

A place invariant (p-invariant) of a Petri net is a vector of non-negative integers that solves the equation:

where and C is the incidence matrix of a Petri net [20].

The proposed decomposition method involves a selection algorithm based on hypergraph theory, thus requiring several related definitions to be cited.

3.2. Hypergraphs

Definition 13.

A hypergraph H is a pair where:

- is a finite and non-empty set of vertices;

- is a finite set of non-empty subsets of V, called hyperedges.

Definition 14.

A vertex is incident to hyperedge if .

Definition 15.

The incidence matrix A of a hypergraph with vertex set and edge set is defined as a matrix , where rows correspond to edges and columns to vertices, such that:

Definition 16.

A transversal T of a hypergraph H is a set whose elements are incident to every hyperedge of the hypergraph.

Definition 17.

A transversal T is minimal if it does not contain any other transversal of the hypergraph H.

Definition 18.

An exact transversal D of a hypergraph H is a set whose elements are incident to every hyperedge of the hypergraph, but each hyperedge is incident to exactly one vertex in the set D forming the exact transversal.

Definition 19.

An exact transversal hypergraph (further referred to as XT-hypergraph or XT) is a hypergraph in which all minimal transversals are exact transversals.

3.3. Hypergraph Model with (max, +) Algebra

The objective of this section is to describe the (max, +) algebra formalism. There are many available approaches to modeling DESs, such as Petri nets, extended state machines, event-graphs, formal languages, generalized semi Markov processes, automata, computer simulation models and so on (see, e.g., [29,30,31,32], but the (max, +) algebra appears to be the most suitable choice [33,34]. The (max, +) algebraic structure (, ⊕, ⊗) is defined with:

with as the field of real numbers.

The operators ⊕ and ⊗ describe the (max, +) algebraic addition and (max, +) algebraic multiplication. The essential properties of the (max, +) algebra operators can be described in the following form:

For matrices and

In [35], it is shown that cyclic discrete-event systems involving synchronization but no choice can be described by a model of the following form:

where:

- k is called the event counter;

- contains the start instants of operations (events) in the counter;

- the matrices and are of size and contain the processing times of operations (events) in the system. The matrix represents the operations executed in the initial state, whereas includes the remaining operations.

Further definitions and details related to the (max, +) algebra formalism can be found in [33]. In Section 7, the procedure for transforming a Petri net model into a (max, +) algebra model is presented.

3.4. Definitions Related to Computational Complexity

Definition 20.

The polynomial complexity of an algorithm B means that the total runtime of B is bounded by a polynomial function of the size of the input data [36].

Definition 21.

The exponential complexity of an algorithm B means that the total runtime of B is bounded by an exponential function of the size of the input data, such that where n is the size of the input data and k is some constant independent of the input size.

Definition 22.

Polynomial delay of an algorithm B means that B produces results in such a way that the time between successive outputs is bounded by a polynomial function of the size of the input data where n is the size of the input data and k is some constant independent of the input size [36].

4. Exact Transversal-Based Algorithms

The Algorithm 1 operates as follows:

- Identify the set of vertices incident to at least one hyperedge, i.e., . Then, for each vertex :

- Compute the star , defined as the set of all hyperedges incident to v. Next, compute the setFor each hyperedge , construct the reduced hypergraphwhere denotes the reduction of with respect to vertex v and hyperedge H, and selects inclusion-minimal hyperedges.

- Ifthen return false.

| Algorithm 1 XTREC() | |

| 1: | input: a hypergraph . |

| 2: | output: true if is an xt-hypergraph, otherwise false. |

| 3: | begin |

| 4: | for do |

| 5: | |

| 6: | for do |

| 7: | |

| 8: | if then |

| 9: | output(false); |

| 10: | stop; |

| 11: | end if |

| 12: | end for |

| 13: | end for |

| 14: | output(true); |

| 15: | end. |

The Algorithm 1 returns true if the examined hypergraph is an exact transversal hypergraph, i.e., belongs to the XT class; otherwise, it returns false. The verification is performed in polynomial time, namely , where and [37].

| Algorithm 2 DLX-XT() — generation of exact transversals using Dancing Links | |

| 1: | input: a hypergraph represented by the incidence matrix , where . |

| 2: | output: all exact transversals (equivalently: all exact covers of columns E by rows V). |

| 3: | procedure Search() ▹ is the current DLX structure |

| 4: | if then |

| 5: | output(T); ▹ all columns (hyperedges) covered exactly once |

| 6: | return; |

| 7: | end if |

| 8: | choose a column with minimal size ; ▹ heuristic: smallest edge/column |

| 9: | for each row (vertex) do |

| 10: | ; ▹ select v to hit |

| 11: | Cover; ▹ DLX cover induced by choosing row v |

| 12: | Search(); |

| 13: | Uncover; |

| 14: | ; |

| 15: | end for |

| 16: | end procedure |

| 17: | begin |

| 18: | initialize DLX structure from A; set ; |

| 19: | Search(); |

| 20: | end. |

| Algorithm 3 Cover/Uncover for DLX-XT (Algorithm X semantics) | |

| 1: | procedure Cover() |

| 2: | for each column e such that do |

| 3: | remove column e from ; |

| 4: | for each row such that do |

| 5: | remove row u from all columns f with ; ▹ enforces “exactly one” coverage per column |

| 6: | end for |

| 7: | end for |

| 8: | end procedure |

| 9: | procedure Uncover() |

| 10: | for each column e such that in reverse order do |

| 11: | for each row such that in reverse order do |

| 12: | restore row u into all columns f with ; |

| 13: | end for |

| 14: | restore column e into ; |

| 15: | end for |

| 16: | end procedure |

The Algorithm 2 (DLX-XT) applies Algorithm X with the Dancing Links [38] data structure to generate exact transversals of a hypergraph by solving the corresponding exact cover problem. At each recursion step, a hyperedge (column) with minimal cardinality is selected to reduce branching, and one of its incident vertices (rows) is chosen to cover it. The algorithm proceeds recursively until all hyperedges are covered exactly once, yielding a valid exact transversal.

The Cover and Uncover procedures (Algorithm 3) implement reversible structural reductions of the incidence matrix. Selecting a vertex removes all hyperedges incident to it and eliminates conflicting vertices from the remaining hyperedges, enforcing the exactness constraint. The use of Dancing Links enables constant-time removal and restoration of rows and columns, allowing efficient backtracking and complete exploration of the solution space without loss of admissible exact transversals.

5. Decomposition

Decomposition is a crucial issue in the analysis of Petri nets, which describe a specific control problem. It allows for extracting smaller sequential SMCs that can be executed concurrently. Decomposition can be carried out using several paths:

- Based on graph theory [10];

- Based on hypergraph theory [10,17];

- Based on linear algebra [16].

Each of these methods has its advantages, disadvantages, and scopes of applicability. To simplify interpretation, this chapter will present algorithms whose formal specification has been described using Petri nets.

5.1. Assumptions on Liveness and Safeness

In this work, Petri nets are assumed to be live and safe, as these properties are fundamental for the correctness and interpretability of structural decomposition into State Machine Components. Liveness guarantees the absence of deadlocks and ensures that all transitions can potentially occur during system execution, which is essential for preserving concurrency semantics. Safeness, in turn, prevents uncontrolled token accumulation and enforces a one-to-one correspondence between places and system states, enabling a meaningful mapping between structural components and automaton-like behavior. These assumptions are consistent with classical Petri net theory and decomposition frameworks, where liveness and safeness are commonly required to ensure well-defined behavioral semantics and correct component-based analysis [21,22].

5.2. Decomposition Based on Graph Theory

The classic, well known decomposition method is based on graph theory. The input is a Petri net in the form of an incidence matrix, where columns correspond to places and rows to transitions. The algorithm consists of the following steps:

- Step 1:

- Creating a macro network, which is a condensed version of the input Petri net. The goal is to remove elements that do not affect the result during analysis, while their presence increases the time required to obtain the result.

- Step 2:

- Determining the reachability graph (markings), whose incidence matrix is constructed as follows: vertices contain a set of places marked in a given state, and edges correspond to fired transitions.

- Step 3:

- Determining the concurrency graph, which contains information about the relationships between places in the decomposed network.

- Step 4:

- Coloring the concurrency graph. The independent sets determined in this way contain macro places that are elements of sequential automata (subnetworks of automata).

- Step 5:

- Replacing macro places with original subsets of places.

The presented method has one fundamental drawback, which is the time required to find the optimal solution for coloring the concurrency graph. It requires the use of a backtracking algorithm, which in turn is associated with exponential computational complexity.

5.3. Decomposition Based on Hypergraph Theory

The second decomposition method to be presented is an algorithm based on hypergraphs. Hypergraphs are an extension of graph theory, as a hyperedge can be incident on more than one hypervertex, while a transversal is a set of vertices where each hyperedge is incident on exactly one vertex that belongs to the exact transversal. The input is a Petri net in the form of an incidence matrix, where columns correspond to places and rows to transitions. The algorithm consists of the following steps:

- Step 1:

- Creating a macro network, which is a condensed version of the input Petri net. The aim is to remove elements that do not affect the result during analysis, while their presence increases the time required to obtain the result.

- Step 2:

- Determining the reachability graph (markings), whose incidence matrix is constructed as follows: vertices contain a set of places marked in a given state, and edges correspond to fired transitions.

- Step 3:

- Determining the concurrency hypergraph, where vertices represent places in the network, and edges represent relationships between them.

- Step 4:

- Determining the sequencing hypergraph, where vertices represent places in the network, and edges represent SMCs determined by obtaining consecutive exact transversals of the concurrency hypergraph.

- Step 5:

- Determining the selection hypergraph, involving obtaining the dual hypergraph (by transposition) of the sequencing hypergraph and subjecting it to reduction using the Fast Reduction Algorithm. The essence of this process lies firstly in determining the essential vertex (if it exists, with a degree of 1), as it must be part of the cover. The next step is to reduce dominating edges, allowing for the reduction of redundant connections between exact transversals. The final step is to reduce dominated vertices.

- Step 6:

- Determining the smallest exact transversal, which defines the sought exact transversals of the concurrency hypergraph, which in turn determine the given subnetworks of automata.

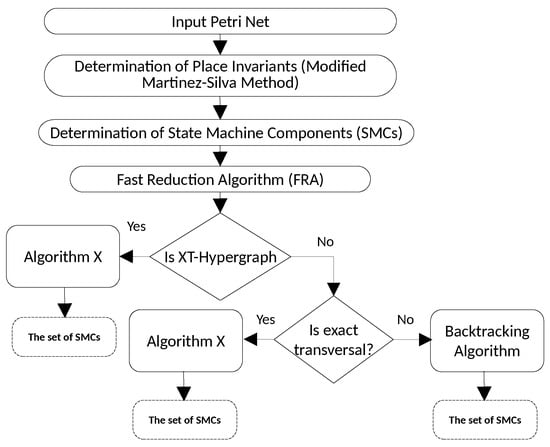

5.4. Decomposition Based on Linear Algebra (Exact Transversal Method)

The preliminary version of the method was proposed in [16]. It is worth noting that this method allows for selecting a solution in polynomial time for XT-hypergraphs (exact transversal in XT-hypergraph can be obtained in polynomial execution time [37]). The author’s method of exact transversals involves the use of linear algebra elements-place invariants of Petri nets (see Figure 1). It utilizes a specific type of hypergraphs, the exact transversal hypergraph, in which every minimal transversal (not containing other transversals) is also exact. The input is a Petri net in the form of an incidence matrix, where columns correspond to places and rows to transitions. The algorithm can be presented in the following steps:

Figure 1.

Diagram illustrating the idea of the exact transversal method.

- Determination of place invariants using the modified Martinez–Silva algorithm;

- Determination of SMCs by selecting correct invariants;

- Selection of SMCs using the exact transversal method (selection hypergraph );

- Classification of the selection hypergraph using the XTREC method (Algorithm 1);

The first step directly refers to the Martinez–Silva algorithm [39]. The modification involves:

- Generating an incomplete set of invariants due to transition reduction using the fast reduction algorithm (FRA),

- Checking if the generated invariants are sufficient to cover the given input network.

In the second step, correct invariants are selected, where an invariant is correct if it contains only one token of initial marking. Next, the selection using exact transversals involves constructing the incidence matrix of the selection hypergraph, where columns represent places and rows represent SMCs. The next step involves determining the dual hypergraph and then the significant vertex, performing reduction of dominating edges and dominated vertices using FRA. An edge dominates another edge if it contains all its elements [40]. The reduction does not exclude admissible exact transversals but enables their identification in a significantly shorter computation time by pruning the solution space from a Petri net perspective. The next step is to check whether it is an exact transversal hypergraph. If so, the exact solution is defined by the first exact transversal (Lemma 1). It is worth emphasizing that, in the case of an XT-hypergraph, it always exists and defines the sought-after SMCs. An exact transversal can be obtained using XTR algorithm [37] or more efficiently by means of Knuth’s Algorithm X implemented by Dancing Links DLX technique [38] (using Algorithm 2). If not, an attempt is made to determine an exact transversal. If it exists, it determines the solution, otherwise, a transversal (if approximate solution is acceptable) or a solution using a backtracking algorithm (if exact solution is required) is determined.

Of course, the proposed approach is not the only one that can be applied to solve the problem at hand. Among the alternatives, the following methods can be distinguished [10]:

- Based on graph theory (using coloring);

- Based on hypergraph theory (using c-exact hypergraphs).

The application of graph theory (using coloring) has one fundamental disadvantage, which is the time needed for the concurrency graph coloring operation. This requires the use of a classical backtracking algorithm, which in turn is associated with exponential computational complexity. On the other hand, the second approach based on hypergraph theory relies on c-exact hypergraphs. There is no known polynomial algorithm for classifying hypergraphs into the c-exact class, so it is not possible to estimate whether and under what conditions the obtained solution will be exact.

Proofs

Lemma 1.

Let be a Petri net coverable by SMCs, and let be its dual sequentiality hypergraph. If possesses exact transversals, then all of them have the same number of elements, equal to the number of tokens in the net , which is conservative.

Proof.

Let be an exact transversal D of the hypergraph . Each defines a SMC of the Petri net ; therefore, according to the definition of an exact transversal, every place P is covered by exactly one . Let M be a reachable marking of the net . Assume that . Then, there exists an covering at least two concurrent places, which contradicts the definition of a State Machine Component. Assume that . Then, there exists a covered by at least two elements belonging to T, which contradicts the statement that “each place P is covered by exactly one .” Assume that . As long as the above reasoning can be applied to any exact transversal of the hypergraph and any reachable marking of the net , the net is conservative, and each exact transversal of the hypergraph consists of the same number of elements, equal to the number of tokens in the net . □

Theorem 1.

Let be a Petri net coverable by SMCs, and let be its dual sequentiality hypergraph. If possesses an exact transversal , then it defines a minimal cover of the Petri net by State Machine Components.

Proof.

According to the definition of the dual sequentiality hypergraph [10], its transversals determine the covering of the Petri net by State Machine Components. By Lemma 1, , where M is any reachable marking of the net . Assume that there exists another transversal from such that . Then, there exists an covering at least two concurrent places, which contradicts the definition of a State Machine Component. Hence, the cover defined by T is the smallest. □

5.5. Novelty of the Proposed Approach

The novelty of the proposed approach lies in the integration of structural decomposition techniques based on exact transversal hypergraphs with temporal analysis grounded in the algebra, enabling a new class of polynomial-time solution selection strategies for concurrent control systems specified by Petri nets.

In contrast to existing decomposition methods, which primarily focus on structural feasibility or qualitative concurrency properties, this work introduces two new elements within the flooding-based decomposition branch. First, the XTREC mechanism is employed to systematically reconstruct admissible State Machine Component (SMC) candidates from exact transversals of the dual XT-hypergraph, ensuring minimal and structurally consistent coverings. Second, the Fast Reduction Algorithm (FRA) is incorporated to prune the solution space in polynomial time, allowing efficient selection among multiple admissible decompositions without exhaustive enumeration.

A key contribution of this work is the demonstration that the structurally obtained SMCs can be further evaluated using temporal performance criteria expressed in the algebra. By mapping the Petri net dynamics onto max-plus state equations, it becomes possible to associate each admissible decomposition with a corresponding system cycle time. This enables, for the first time in the context of XT-hypergraph-based decomposition, the selection of SMC configurations that minimize the overall cycle time of the concurrent system.

The proposed framework thus bridges the gap between purely structural decomposition methods and performance-oriented temporal analysis. Unlike classical approaches, which treat decomposition and timing optimization as separate problems, the presented method provides a unified perspective in which structural correctness, concurrency preservation, and temporal optimality are addressed simultaneously. This opens new possibilities for time-aware decomposition of control logic intended for implementation in PLCs, FPGA-based controllers, and other real-time embedded platforms.

From a broader perspective, the integration of exact transversal hypergraphs with max-plus algebra introduces a novel methodological pathway for analyzing and optimizing concurrent systems. It extends prior work on XT-hypergraph-based decomposition by enriching it with quantitative performance metrics, thereby advancing the state of the art toward formally grounded, time-optimal synthesis of concurrent control structures.

6. Selected Formal Models of Concurrent Systems and Their Limitations

The literature on concurrent systems distinguishes several formal models used for their representation, among which the most commonly applied are Petri nets, finite automata, concurrency graphs, and hypergraphs.

Petri nets are among the most widespread models of concurrent systems due to their intuitive graphical structure and ability to describe the dynamics of concurrent processes. Their application allows for the analysis of properties such as liveness, safeness, and boundedness [21,41]. However, one of the major limitations of Petri nets is the state space explosion, which significantly hampers—or even prevents—the analysis of larger systems [14].

Finite automata constitute another frequently used model, offering straightforward implementation and efficient formal analysis [20]. A key advantage of automata is their seamless integration with formal verification techniques, particularly model checking. Nevertheless, they struggle to express concurrency directly, often requiring more complex constructions (e.g., product automata), which again leads to the problem of state space explosion [42].

Concurrency graphs provide a graphical representation of concurrent processes, enabling intuitive analysis of their interactions and dependencies [43]. However, similar to classical graph-based methods, the analysis of large concurrency graphs results in exponential complexity, especially for problems such as graph coloring or maximum clique detection [10].

Hypergraphs and in particular, exact transversal hypergraphs (XT-hypergraphs) offer a promising alternative to the aforementioned models. They allow for an unambiguous and computationally efficient representation of complex concurrency relations among system elements [10,37]. The use of XT-hypergraphs enables effective decomposition of concurrent systems, mitigating the issues related to state space explosion and computational complexity [17].

It should be noted that although classical models such as Petri nets and finite automata have many advantages, their application to large and complex concurrent systems encounters significant limitations. The introduction of XT-hypergraph-based methods significantly improves efficiency in both the analysis and implementation phases of concurrent systems, making them a preferred choice in modern industrial applications.

7. XT-Guided Timing Analysis with (max, +) Algebra

The structural decomposition of concurrent systems using XT-hypergraphs not only simplifies their logical architecture but also enables algebraic timing analysis. Once a Petri net is decomposed into deterministic SMCs, each component can be modeled as a timed event graph, a subclass of Petri nets particularly suitable for the (max, +) framework. This approach provides a direct analytical method for determining performance indices such as throughput, cycle time, and latency while maintaining formal correspondence with the original Petri net structure [18,44].

(max, +) Algebra Model

The input data for constructing the (max, +) algebra model are as follows:

- The system structure, represented by a hypergraph or a Petri net.

- The execution times of operations in the system, where individual places in the Petri net (or hypergraph) represent operations carried out in the system.

- The initial state of the system, represented by the initial marking of the Petri net (or hypergraph).

The (max, +) algebra model construction procedure comprises the following two stages:

- Stage 1:

- Specification of the state vector and the time vector.

The size of the state vector is equal to the number of places (operations performed in the system. It is defined as follows:

where: is the starting time of the ith operation in the kth cycle (iteration), n is the total number of operations. Accordingly, corresponds to the firing time of the input transition of the ith place.

where is the execution time of the ith operation. Thus, is related to the minimum residence time of a token in place , representing the mandatory delay before the token becomes available for enabling subsequent transitions.

- Stage 2:

- Determining the components of the state equation.

Deterministic SMCs under consideration can be described by the model in (4). Note that the state equation (4) is equivalent to:

where:

If the matrix A is correspondent to the strongly connected graph, than it possesses an unique eigenvalue in the (max, +) algebraic sense [45].

is eigenvalue of the matrix (i.e., the maximal mean cycle weight taken over all cycles in the graph corresponding to ) and v is an eigenvector of matrix . Thus, if is an eigenvector of A, then

where: is the system period. A certain DES has a linear representation based on the (max, +) algebra with the equations as follows:

where:

- denotes the state consisting of the time moments related to the internal events at kth counter,

- is the state matrix.

Having the model time PN and initial marking , the procedure for constructing matrices and consists of the following steps:

- Step 1:

- Decompose the PN model into subsets of PN, taking into account the dispatching of potential conflicts.

- Step 2:

- Obtain all cycles that occur within each subset of the PN model.

- Step 3:

- Mark the PN so that only one token occurs in each cycle.

- Step 4:

- Create the matrices and according to the following conditions:

- is equal to if place is empty, and if is both an input place of transition and an output place of transition ; otherwise, .

- is equal to if place contains a token, and if is both an input place of transition and an output place of transition ; otherwise, .

Integrating XT-hypergraph decomposition with (max, +) algebra yields: (1) deterministic timing semantics (XT resolves concurrency without branching nondeterminism, enabling a linear (max, +) model; (2) polynomial computational cost for eigenvalue/scheduling analysis; (3) compatibility with implementation (periodic schedules for real-time execution or hardware synthesis); and (4) consistency with formal verification (alignment with liveness, boundedness, and periodic execution properties).

The integration establishes a bridge between the structural formalism of XT-hypergraphs and the quantitative analysis capabilities of (max, +) algebra. While XT determines what components can operate independently, the (max, +) model defines when and how fast they operate. Together, they form a unified, formally grounded framework enabling both structural and temporal optimization of concurrent discrete-event systems.

8. Example of Decomposition with Comparative Analysis

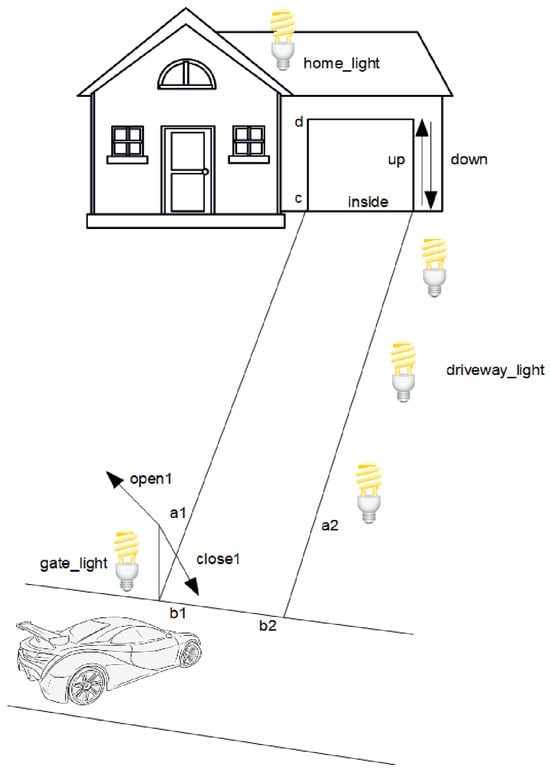

The exact transversal method will be presented using an example of a smart home control system shown in Figure 2. The smart home includes a garage with a gate controlled independently using appropriate sensors. Inside and outside the house, there are lighting points. The entrance gate opens automatically, activating the appropriate lighting.

Figure 2.

Figure illustrating the smart home control system example.

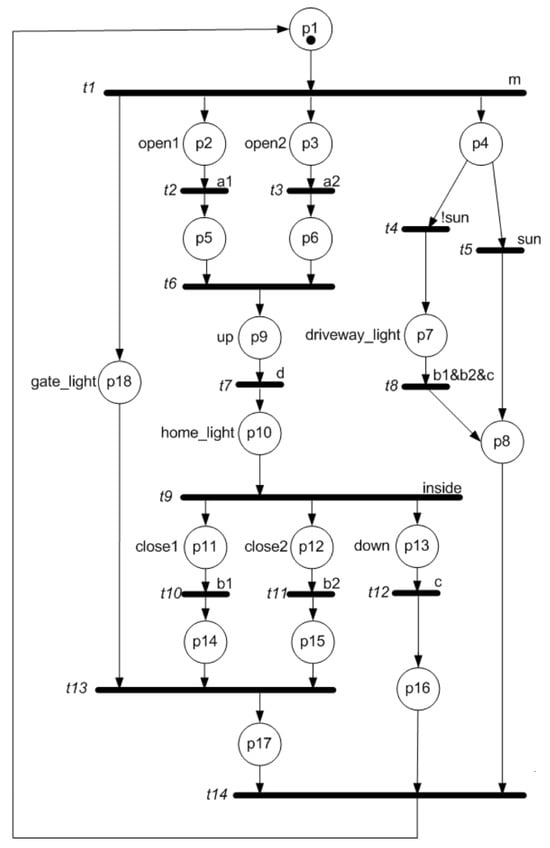

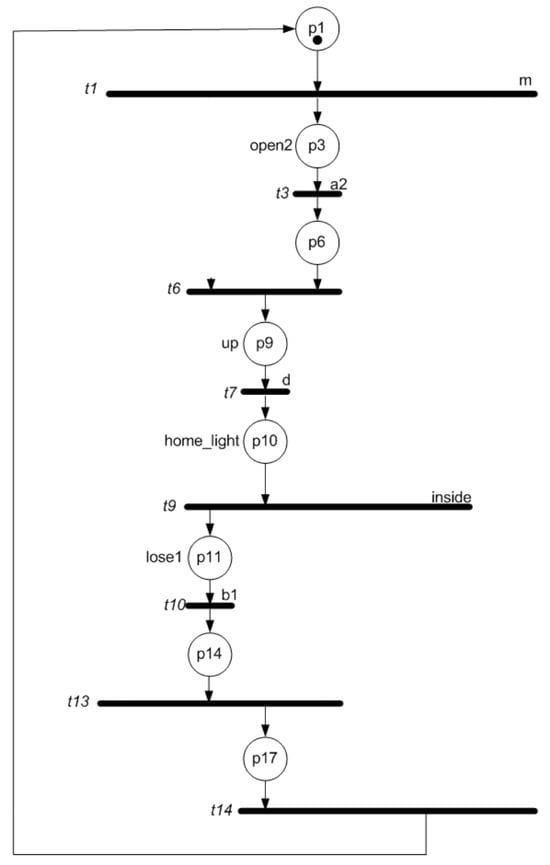

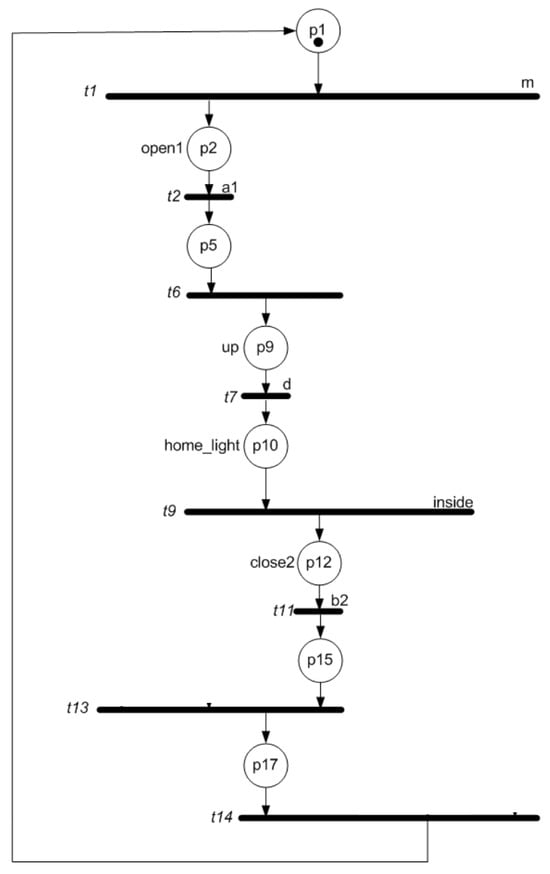

For the defined system, a Petri net has been designed to model all necessary processes, as shown in Figure 3. The given Petri net has 18 places and 14 transitions. The first step of the algorithm is to determine place invariants. For this Petri net, seven invariants can be determined, which are shown in the matrix below.

The next step is to define the selection matrix by selecting correct invariants and then reducing the matrix using FRA. It is worth noting that hypergraph theory is applied here because this matrix is treated as a hypergraph. After applying the algorithm, the final form of the matrix is as follows:

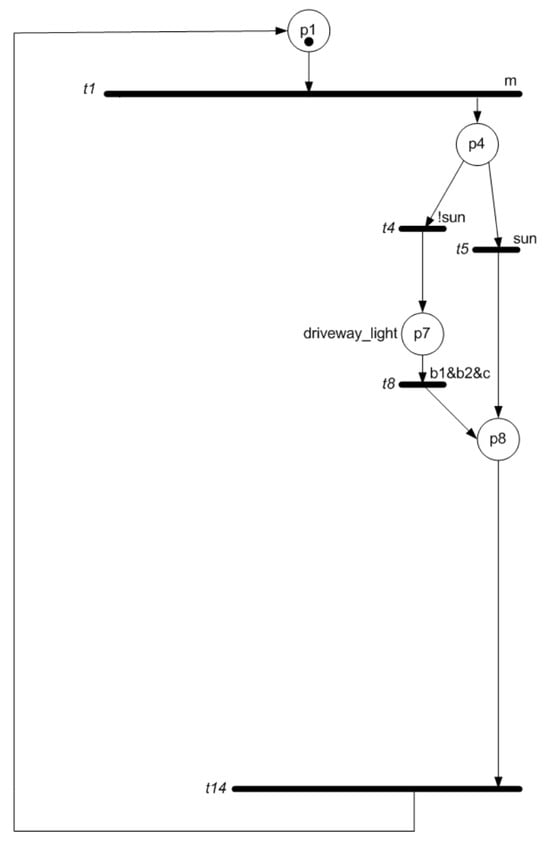

Next, the check is performed to determine if the given selection hypergraph belongs to the xt class (whether it is an exact transversal hypergraph). To do this, the XTREC algorithm is used. As a result of its operation, the result ’true’ is obtained, indicating that this hypergraph is an XT-hypergraph. The last step is to determine the first exact transversal , which allows obtaining a solution equally good as any subsequent one. It is worth emphasizing that the first one is always obtained in polynomial time. Based on this, the following State Machine Components necessary to cover the original network are selected:

Figure 3.

Figure illustrating the Petri net corresponding to the smart home control system.

In this way, the solution to the problem has been determined. The actual implementation in hardware (PLC or FPGA) will of course require the introduction of no-operational places (NOPs) in place of those shared. It should be noted that the decomposition of the initial network (Figure 3) consisting of 18 places and 14 transitions was carried out automatically using the proposed algorithm. For input data in the form of a Petri net described by an incidence matrix, the result is returned—a vector specifying which SMCs are the solution to the decomposition problem. Due to limited space, it is not possible to present an example for a more complex control network; however, Table 1 presents results for selected systems. The first column contains the network name and the number of places and transitions in parentheses. The second and third columns contain the time [ms] needed to obtain the result and the number of subnets in parentheses. By “classical method”, the author means a decomposition algorithm that uses the classical Martinez-Silva method to obtain invariants and uses a backtracking algorithm (checking all possibilities) to obtain a solution.

Table 1.

Table containing comparative results between the classical method and the proposed one.

Figure 4.

Subnet .

Figure 5.

Subnet .

Figure 6.

Subnet .

Figure 7.

Subnet .

Figure 8.

Subnet .

Table 1 shows selected comparative results of the classical method with the proposed one. As can be seen, the proposed method always allows obtaining a result in a relatively short time, which will be equally good as those returned by the classical method. For several example networks, the classical method did not provide a solution within 40 min. A very interesting network is crossSM (crossroad SM), which describes a real traffic light control system at an intersection. The classical method takes about 30 min to find a solution, while the proposed method only takes about 19 ms, and both solutions are equivalent and equally good (10 subnets were selected). The networks listed in the table can be found in the Hippo system available at https://hippo.uz.zgora.pl (accessed on 4 December 2025).

The XT-based approach maintains polynomial complexity, avoiding the exponential cost of interleaving-based concurrency enumeration. This superiority can be clearly visible in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of computation times for classical and XT-based methods.

9. Conclusions

This article has presented a comprehensive investigation of XT-hypergraphs as a formal tool for the structural decomposition of concurrent control systems modeled by Petri nets. The core contribution lies in demonstrating that exact transversal hypergraphs (XT) provide a precise and compact representation of concurrency relations that arise naturally in the behavior of real-world systems. By introducing minimal transversals as a basis for deterministic execution paths, the proposed methodology enables the decomposition of complex systems into simpler, linear, and fully synthesizable SMCs without loss of behavioral fidelity.

Throughout the study, XT-based decomposition has been applied to representative classes of systems: smart home systems, industrial process control, traffic light control, etc. Each of these systems presents different patterns of concurrency and control complexity, yet all were successfully transformed into hardware-compatible control logic using a unified XT-based formalism.

Another important aspect is the extensibility of the XT model. Although it is grounded in a strict formal foundation, it naturally supports practical extensions such as hierarchical decomposition, interface-based partitioning, and dynamic reconfiguration. Furthermore, it offers potential integration points with logic optimization techniques and formal verification tools. This makes XT-hypergraphs not only a powerful modeling abstraction but also a practical engineering framework capable of bridging the gap between formal methods and hardware/software co-design.

In conclusion, the use of XT-hypergraphs in system decomposition brings a unique combination of formal clarity, implementation efficiency, and scalability. The technique is especially suited for domains where concurrency, safety, and determinism must coexist such as embedded control, CPS, and energy-aware systems. The formalism’s ability to express and resolve concurrency deterministically, while keeping the system design modular and lightweight, opens up promising directions for further integration with automated synthesis, model-checking, and reconfigurable computing. The results presented herein confirm that XT-based decomposition constitutes a robust and elegant solution to the enduring challenges of concurrency modeling in system engineering.

The planned future work focuses on an extended integration framework that combines XT-based structural decomposition with temporal modeling in a fully end-to-end manner. In particular, the framework will transform the static structure of admissible State Machine Components (SMCs) into dynamic state equations by explicitly associating timing parameters and delays with transitions and places, exploiting the initial marking and system-level constraints. This will enable the computation of cycle times for individual SMCs and the systematic selection of exact transversals that minimize the overall system cycle time.

A major direction of future research will be the inclusion of larger and more diverse benchmark suites, along with harmonized evaluation metrics such as the number of SMCs, inter-component coupling, runtime, and memory consumption. These benchmarks will be used to provide quantitative, reproducible comparisons with selected baseline approaches and to assess scalability limits. Furthermore, fast spectral analysis will be employed to verify XT-hypergraph transversals and to guide time-optimal solution selection within the reduced solution space.

Additionally, future work will address richer classes of models, including interpreted, timed, and extended Petri nets, as well as a more detailed analysis of failure modes and assumptions. The development and public release of a dedicated software tool, currently under construction as an external web-based service and based on extended prototypes of the HIPPO library, is also planned. Altogether, the integration of XT-hypergraph theory with algebra, supported by comprehensive validation and tooling, aims to provide a coherent and efficient methodology for the design, optimization, and verification of complex discrete-event control systems, particularly targeting hardware implementations such as FPGA- and PLC-based platforms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ł.S.; Formal analysis: Ł.S., P.M. and M.W.; XT-based decomposition methodology: Ł.S.; (max, +)-based methodology: Ł.S., P.M. and M.W.; Experimental results: Ł.S.; Writing—original draft: Ł.S., P.M. and M.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research presented in this paper has not received funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in https://hippo.uz.zgora.pl.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CPS | cyber-physical system |

| DES | discrete event systems |

| DLX | dancing links |

| FRA | fast reduction algorithm |

| PN | Petri net |

| SMC | state machine component |

| XT | exact transversal hypergraph |

References

- Tapia-Flores, T.; Lopez-Mellado, E.; Estrada-Vargas, A.; Lesage, J. Discovering Petri Net Models of Discrete-Event Processes by Computing T-Invariants. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2018, 15, 992–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halba, K.; Griffor, E.; Lbath, A.; Dahbura, A. IoT Capabilities Composition and Decomposition: A Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 29959–30007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonham, W.; Cai, K.; Rudie, K. Supervisory Control of Discrete-Event Systems: A Brief History–1980-2015. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 1791–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wonham, W.M.; Cai, K. Supervisory Control of Discrete-Event Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capra, L.; Gribaudo, M. Efficient Performance Analysis of Modular Rewritable Petri Nets. Electron. Proc. Theor. Comput. Sci. 2024, 410, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, P. Optimization of the Time Durations by Exploiting Time Margins in Time Interval Models. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2022, 30, 755–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammedi, S.; Chniti, H. Combining Petri Nets and AI Techniques to Improve Dynamic Production Scheduling Optimization. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Agents and Artificial Intelligence, Rome, Italy, 22–24 February 2025; pp. 1077–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mušič, G. Petri Net Based Solution Supervision and Local Search for Job Shop Scheduling. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2021, 54, 665–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Zhou, M.; Li, Z.; Al-Ahmari, A. Structural Decomposition and Decentralized Control of Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man, Cybern. Syst. 2018, 48, 1360–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewska, M. Application of Hypergraphs in Decomposition of Discrete Systems; University of Zielona Góra Press: Zielona Góra, Poland, 2012; Volume 23, p. 143. [Google Scholar]

- Cochefert, M.; Couturier, J.F.; Gaspers, S.; Kratsch, D. Faster algorithms to enumerate hypergraph transversals. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1510.05093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurita, K.; Mann, K. On the Complexity of Hyperpath and Minimal Separator Enumeration in Directed Hypergraphs. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.07528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanté, M.M.; Khoshkhah, K.; Pourmoradnasseri, M. Enumerating Minimal Transversals of Hypergraphs without Small Holes. In Proceedings of the 43rd International Symposium on Mathematical Foundations of Computer Science (MFCS 2018), Liverpool, UK, 27–31 August 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiśniewski, R.; Patalas-Maliszewska, J.; Wojnakowski, M.; Topczak, M. Modeling and Analysis of a Petri Net-Based System Supporting Implementation of Additive Manufacturing Technologies. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 546–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Li, H.; Wu, C.; Peng, Y.; Du, X.; Wang, H.; Mohammed, S.; Calvi, A.; Zhang, D. Multivariate event hypergraph diffusion model for train delay prediction. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2026, 182, 105390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz. Conception of discrete systems decomposition algorithm using p-invariants and hypergraphs. In Proceedings of the Photonics Applications in Astronomy, Communications, Industry, and High-Energy Physics Experiments, Wilga, Poland, 29 May–6 June 2016; Romaniuk, R.S., Ed.; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefanowicz. Decomposition of Concurrent Control Systems specified by Petri Nets. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Zielona Gora, Zielona Góra, Poland, 2023. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Komenda, J.; Lahaye, S.; Boimond, J.L.; van den Boom, T. Max-Plus Algebra and Discrete Event Systems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2017, 50, 1784–1790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karatkevich, A. Dynamic Analysis of Petri Net-Based Discrete Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; 166p. [Google Scholar]

- Wiśniewski, R. Prototyping of Concurrent Control Systems Implemented in FPGA Devices; Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murata, T. Petri nets: Properties, analysis and applications. Proc. IEEE 1989, 77, 541–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desel, J.; Esparza, J. Free Choice Petri Nets; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Ramchandani, C. Analysis of Asynchronous Concurrent Systems by Timed Petri Nets. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- David, R.; Alla, H. Discrete, Continuous, and Hybrid Petri Nets; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molloy, M.K. Performance Analysis Using Stochastic Petri Nets. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1982, C-31, 913–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmone Marsan, M.; Balbo, G.; Conte, G.; Donatelli, S.; Franceschinis, G. Modelling with Generalized Stochastic Petri Nets; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- German, R. Performance Analysis of Communication Systems: Modeling with Non-Markovian Stochastic Petri Nets; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, J.L. Petri Net Theory and the Modeling of Systems; Prentice Hall: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Sahner, R.; Trivedi, K.; Puliafito, A. Performance and Reliability Analysis of Computer Systems: An Example-Based Approach Using the SHARPE Software Package; Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Abrams, M.; Doraswamy, N.; Mathur, A. Chitra: Visual analysis of parallel and distributed programs in the time, event, and frequency domains. Parallel Distrib. Syst. IEEE Trans. 1992, 3, 672–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hillion, H.P.; Proth, J.M. Performance evaluation of job-shop systems using timed event-graphs. Autom. Control. IEEE Trans. 1989, 34, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Dridi, M.; El Moudni, A. An autonomous vehicle sequencing problem at intersections: A genetic algorithm approach. Int. J. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 2013, 23, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butkovic, P. Max-Linear Systems: Theory and Algorithms; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Majdzik, P.; Witczak, M.; Lipiec, B.; Banaszak, Z. Integrated fault-tolerant control of assembly and automated guided vehicle-based transportation layers. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 35, 409–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccelli, F.L.; Cohen, G.; Olsder, G.J.; Quadrat, J.P. Synchronization and Linearity: An Algebra for Discrete Event Systems; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Papadimitriou, C. Computational Complexity; Addison-Wesley, Reading: Boston, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Eiter, T. Exact Transversal Hypergraphs and Application to Boolean μ-functions. J. Symb. Comput. 1994, 17, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knuth, D.E. Dancing Links. In Proceedings of the Millennial Perspectives in Computer Science; Palgrave: London, UK, 2000; pp. 187–214. [Google Scholar]

- J. Martinez, M.S. A Simple and Fast Algorithm to Obtain All Invariants of a Generalized Petri Net. In Proceedings of the Selected Papers from the European Workshop on App. and Theory of Petri Nets, London, UK, 28–30 June 1982; pp. 301–310. [Google Scholar]

- Rudell, R.L. Logic Synthesis for VLSI Design. Ph.D. Thesis, EECS Department, University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, K.; Kristensen, L.M. Coloured Petri Nets: Modelling and Validation of Concurrent Systems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kovalyov, A.; Esparza, J. A Polynomial Algorithm to Compute the Concurrency Relation of Free-choice Signal Transition Graphs. In Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Application of Concurrency to System Design (ACSD), Tunis, Tunisia, 23–27 June 2014; pp. 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diestel, R. Graph Theory, 5th ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hardouin, L.; Cottenceau, C.; Corronc, E.L.; Boimond, J.L.; Santos-Mendes, R. Observer Design for (max, +) Linear Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2013, 58, 3191–3196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccelli, F.; Cohen, G.; Olsder, G.J.; Quadrat, J.P. Synchronization and linearity: An algebra for discrete event systems. J.-Oper. Res. Soc. 1994, 45, 118. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.