Abstract

Botnets represent a persistent and significant threat to internet security. Many detection methods fail because they analyze isolated node data, neglecting the coordinated interactions of centrally managed bots. Graph-based methods, particularly Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), offer a promising solution. This study developed and compared four novel GNN models (HeteroGCN, HeteroGAT, HeteroSAGE, and HeteroGAE) for botnet detection. We constructed a heterogeneous graph from the TI-16 DNS-labeled dataset, capturing interactions between users and domains. Experimental results show our models achieve up to 95% accuracy. Specifically, HeteroSAGE and HeteroGAE significantly outperform other models, demonstrating superior F1-Scores and exceptionally high Recall. This high recall, indicating a low false-negative rate, is critical for effective anomaly detection. Conversely, the computationally expensive HeteroGAT model yielded poorer results and slower inference times, demonstrating that increased model complexity does not guarantee better performance. To our knowledge, this is the first study to successfully apply and compare heterogeneous GNNs for bot detection using DNS query data.

1. Introduction

Botnets continue to pose a major threat to internet services and networks. Before it was dismantled in 2024, 911 S5 was identified as the largest known botnet, with a network of 19 million active bots across 200 countries [1]. In the literature, a botnet is defined as a network of compromised devices, also known as bots or zombie agents, controlled by malicious users to perform hostile actions on the internet [2]. Attackers utilize botnets to steal sensitive information, conduct distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks, send spam and phishing attacks, and perform crypto-mining. These networks are also often available as a service (Botnet-as-a-Service) via the darknet [3].

The literature includes analysis-based botnet detection studies that utilize honeypots; however, the majority of the research consists of signature- and/or anomaly-based detection efforts [2,4]. Anomaly-based studies, often preferred for detecting zero-day attacks, primarily focus on host- or network-centric methods [5]. Existing botnet detection research employs statistical and deep learning-based approaches, as well as hybrid methods combining these techniques [2]. These studies typically utilize network flow information alongside protocol data (IRC, HTTP, and DNS) frequently used for communication among botnet components [5]. Although benchmark datasets suitable for botnet detection are available [6,7], they are primarily structured for statistical and deep learning-based methods. Consequently, this data requires additional preprocessing to be utilized in graph-based methodologies.

Relying solely on data from isolated nodes is insufficient for detection, especially considering that botnet nodes are centrally managed and often employ obfuscation and mimicry techniques to challenge network defenses. The behavioral similarity of nodes within the network and their interactions should play a significant role in detecting botnets because these qualities cannot be easily mimicked. In a review of graph-based network security monitoring, Lagraa et al. [8] emphasized the important role of Graph Neural Network (GNN) approaches in solving this problem. Since GNN approaches inherently process relational data, they offer a strong natural defense against such simple pattern-mimicry attacks. As a result, numerous graph-based botnet detection studies have been conducted over the past decade [9,10,11,12,13].

Based on the premise that flow and node data alone are inadequate for detecting compromised zombie nodes, this study developed and compared four novel Graph Neural Network (GNN)-based approaches that incorporate inter-node network interaction into the detection process. The attributes for the generated heterogeneous graph nodes were obtained by preprocessing the TI-16 DNS-labeled dataset [6]. Test results indicated that the developed models identified botnet-compromised nodes with an accuracy rate of up to 95%. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in the literature to perform GNN-based bot detection using DNS queries.

The remainder of this article is organized as follows. Section 2 explains the botnet lifecycle and presents the existing detection methods from the literature. The four GNN architectures developed in this study are introduced in Section 3. Section 4 describes the dataset, the graph structure, and the proposed detection architecture. Section 5 presents the metrics used for performance analysis, and Section 6 provides the architectural and hyperparameter details of the trained models. The experimental results are presented in Section 7 and discussed in detail in Section 8. Finally, the Section 9 concludes the article and provides suggestions for future research.

2. Related Works

A botnet is an overlay network of compromised computers controlled by a malicious actor known as a bot master. This network structure consists of the bots, command and control (C2) nodes, and the bot master. Botnets may exhibit various topologies, which are determined by the placement of C2 nodes used to manage the compromised devices and conceal the bot master. Commonly observed topologies include star, multi-server, hierarchical, and random. The specific topology is a primary factor influencing the network’s resilience to takedown attempts and its administrative simplicity. For instance, botnets with a centralized topology are straightforward to manage; however, their C2 nodes and bot master can be rapidly identified. Conversely, in layered and random topologies, network administration is more challenging, and message transmission is time-consuming, and it is significantly more difficult to detect the botnet’s command units [14].

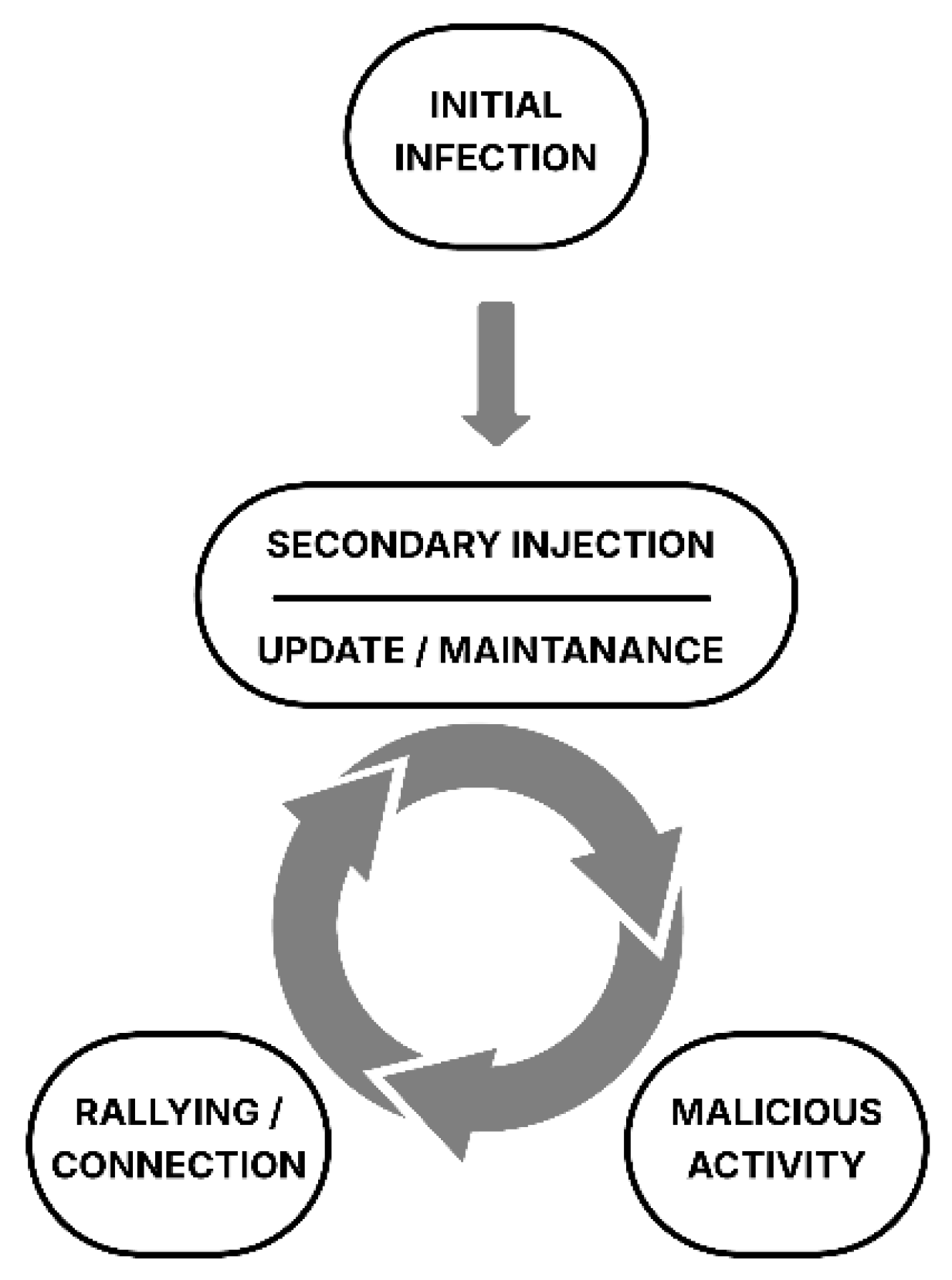

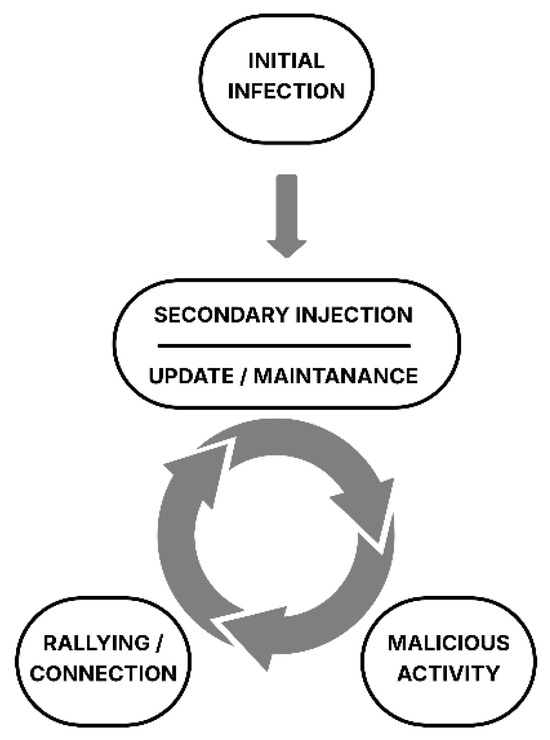

C2 nodes are critical, as they relay commands from the bot master to the bots, thereby orchestrating the intended attack. Beyond coordinating the attack, these nodes also ensure the monitoring and continuous updating of the compromised devices as illustrated in Figure 1. To identify new targets for expansion, botnets leverage their existing compromised nodes to conduct reconnaissance (network scans) within infiltrated networks. This process allows them to pinpoint nodes with exploitable vulnerabilities. It is not strictly limited to active scanning methods; social engineering techniques are also effectively utilized during the reconnaissance stage [15].

Figure 1.

Botnet lifecycle.

Graph Neural Networks for Botnet Detection

Early research in botnet detection primarily focused on approaches utilizing feature vectors derived from flow statistics and machine learning methods. In these studies, network traffic was reduced to attributes such as connection count, byte volume, duration, and port distribution for use in classification algorithms. Then, DNS-based botnet detection gained prominence, aiming to identify malicious domain names through methods such as anomaly analysis of query rates and Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) detection. For instance, multi-stage approaches like MONDEO [16,17] have reported successful results in detecting mobile botnets by combining DNS query rate and DGA analysis into a single pipeline. Similarly, studies processing sequential DNS query streams using temporal deep learning models, such as BiGRU [18,19], focus on client-level botnet detection utilizing solely DNS traffic. However, a significant portion of these methods treat DNS queries merely as time series or independent instances, failing to directly model the structural graph-level relationships between clients and domains.

In recent years, graph-based attack and botnet detection have emerged as a distinct research domain, driven particularly by the rise of Graph Neural Networks (GNN). Surveys on graph-based Intrusion Detection Systems (IDS) demonstrate that attack patterns can be effectively learned through node and edge relationships by transforming network traffic into graphs at the flow, host, or session level [20,21]. These reviews report that architectures such as Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN), GraphSAGE, Graph Attention Networks (GAT), and graph autoencoders (GAE/VGAE) are widely utilized in network and IoT attack detection, demonstrating robust performance in modeling anomalies like botnets, DDoS, and port scanning. Furthermore, more recent studies [22,23,24] highlight the emerging application of heterogeneous graph neural networks to cybersecurity anomaly detection, emphasizing that multi-typed node and edge structures enable the representation of various dimensions of attack behavior within a unified latent space.

When examining GNN-based studies specifically targeting botnet detection, various model proposals based on communication graphs become prominent. For example, Zhao et al. [10], proposed Bot-AHGCN, a model operating on a multi-attributed heterogeneous communication graph. By jointly modeling diverse entities such as IPs, ports, and response types to detect bot nodes, they demonstrated that the heterogeneous GCN architecture is effective in capturing behavioral patterns from multiple perspectives. Lagraa et al. [13] presented a comprehensive review systematically examining graph representations, analysis techniques, and common graph features utilized in network security monitoring and botnet detection; they highlight that graph-based approaches are powerful tools for capturing community structures, anomaly patterns, and botnet behaviors within high-dimensional traffic data.

The XG-BoT model proposed by Lo et al. [25] utilizes a deep GNN backbone to learn node representations within large-scale botnet communication graphs. It also supports the automated forensic analysis process by revealing, through an integrated explainability component, which subgraph structures and neighborhoods play a critical role in detection. Altaf et al. proposed a sequential Gated Graph Convolutional Network (GGCN) framework that accepts sequential network flows as input and learns the relationships between them via a gated mechanism. This model simultaneously considers inter-flow temporal dependencies and topological neighborhoods to detect botnet attacks in IoT networks, reporting superior performance compared to classical flow-based approaches [26]. By treating these network flows as nodes, such research has employed GGCNs or attention-based GAT architectures to jointly model temporal and structural dependencies. This demonstrates the ability to capture the characteristic communication patterns formed by IoT botnets. Similarly, approaches such as E-GraphSAGE [27] proposed GNN-based intrusion detection systems that transform flow records into graphs to leverage both node and edge attributes, reporting higher detection success than classical machine learning methods.

There are a limited number of studies that construct a heterogeneous DNS graph using client-domain relationships and compare heterogeneous GNN architectures on it. Although a few studies, such as Bot-AHGCN [10] and others [28,29] operate on heterogeneous information networks, they predominantly model communication sessions, flow/packet modalities, or system entities as distinct node types. The frequent processing of DNS queries as time series or independent records [18] hinders the full exploitation of the bipartite structure that reflects the associations between clients and domains. Conversely, modeling clients and domains as distinct node types within a single graph facilitates the joint learning of both client behaviors and domain characteristics.

Our study evaluates HeteroGCN, HeteroSAGE, HeteroGAT, and HeteroGAE architectures for the task of node-level botnet detection on a client-domain heterogeneous graph generated from the TI-16 DNS dataset. The aim is to introduce a novel perspective to the GNN-based botnet detection literature that is DNS-focused and incorporates client-domain heterogeneity. Furthermore, by bridging the gap between DNS-based approaches and GNN-based graph learning methods, this work offers a foundational framework that connects DNS and graph-based botnet detection for future research.

3. Graph Models

Traditional deep learning methods for anomaly detection analyze each data point (node) in isolation, focusing exclusively on its individual features. The fundamental limitation of this approach is the failure to incorporate inter-node relationships. Graph learning methods address this deficiency by utilizing information derived from neighboring node interactions in addition to the nodes’ inherent characteristics. In this study, four distinct Graph Neural Network (GNN) approaches—HeteroGCN, HeteroSAGE, HeteroGAT, and HeteroGAE—were developed for heterogeneous graphs to detect bot nodes within an autonomous system.

- HeteroGCN

HeteroGCN is an adaptation of the Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) architecture, originally proposed by Kipf and Welling, tailored for heterogeneous graph structures. This architecture manages heterogeneity by employing a distinct weight matrix for each relationship type (represented by different edges). Like the Relational GCN (R-GCN) model, this approach enables message passing across multiple relation types. A constraint of the underlying GCN framework, however, is that information aggregated from neighbors is summed using fixed weights, which are normalized based on the neighbor count [30]. Consequently, this structure prevents the model from dynamically learning the specific significance of different neighbors.

- HeteroSAGE

HeteroSAGE adapts the GraphSAGE algorithm for heterogeneous graph structures. It employs a learnable aggregation function that samples and summarizes the features of neighboring nodes to learn an embedding vector for each node. This process transforms the information gathered from each node’s neighbor-subgraph into an intermediate representation, which allows the model to generalize inductively to new (unseen) nodes [31]. The architecture adapts to heterogeneity by defining separate weight matrices for each edge and node type [32]. For instance, neighborhood information from different relationship types is processed using distinct transformation matrices. A key feature of the GraphSAGE layer is that it applies separate weights to the node’s own features and the neighborhood summary during concatenation. This mechanism prevents a node’s intrinsic features from being overshadowed by neighborhood information, thereby effectively integrating signals from different neighboring types. Consequently, HeteroSAGE can capture topological and content information more effectively than GCN due to its more flexible messaging paradigm.

- HeteroGAT

HeteroGAT adapts the Graph Attention Network (GAT) architecture for heterogeneous graph structures. Instead of aggregating messages from neighbors using a fixed average, GAT weights them using learnable attention coefficients [30]. Fundamentally, a GAT layer calculates the contribution of a neighbor to node by multiplying it with a coefficient This coefficient is computed and normalized by a self-attention mechanism that takes the features of nodes and as input. This process allows the model to learn the relative importance of each neighbor. Consequently, the information from significant neighbors is incorporated more strongly into the node’s representation than the information from less significant ones. HeteroGAT utilizes a separate attention mechanism, or at least a separate set of parameters, for each edge type to learn the distinct importance of various neighbors and relationship types. This attention mechanism is frequently implemented in a multi-head fashion, where multiple parallel attention networks compute coefficients, and their resulting output features are combined to achieve a more stable and expressive representation. This architecture is particularly powerful in scenarios with heterogeneous neighbors, as the model autonomously learns which information is most valuable.

- HeteroGAE

HeteroGAE applies the Graph Auto-Encoder (GAE) architecture to heterogeneous graph settings. The GAE model utilizes an encoder–decoder structure: the encoder, typically a stack of GNN layers (like GCN), learns a low-dimensional embedding for each node, while the decoder attempts to reconstruct the graph structure from these embeddings. In this study, HeteroGAE learns node representations by leveraging all edge information from the heterogeneous graph in an unsupervised manner. A multi-layered hetero-GNN serves as the encoder, with distinct hidden representation dimensions selected for each node type. During training, the HeteroGAE model adjusts its weights to reconstruct the graph’s adjacency matrix. The objective of optimization is to produce a high probability for true edges and a low probability for non-existent (negative) ones. This unsupervised methodology allows the model to effectively capture the graph’s comprehensive topological structure and intrinsic relationships, independent of class labels. Studies by Kipf and Welling [33] have demonstrated the effectiveness of GAE/VGAE in link prediction tasks. The HeteroGAE structure can provide a strong initialization as pre-training, especially when label information is limited, or it can be used directly to solve the link prediction problem. Due to its unsupervised nature, HeteroGAE possesses a greater potential for comprehensively learning topological information compared to the other models.

4. Experiment Setup

This study utilized the TI-16 DNS benchmark dataset compiled by Singh et al. [6]. This comprehensive dataset originates from an operational campus network, capturing DNS queries from 4000 active users during peak hours. In addition to raw network packet information (pcap), the dataset provides 24 client-specific features extracted from DNS queries, conveniently formatted as CSV files to streamline machine learning applications. The dataset encompasses both benign queries and those associated with nine distinct botnet families. End-user DNS queries are labeled as either ‘benign’ or ‘bot’. Queries classified as ‘bot’ also specify the corresponding botnet family and the Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) validity period.

For the bot detection task, four distinct Graph Neural Network (GNN) models were trained: HeteroGCN, HeteroSAGE, HeteroGAT, and HeteroGAE. Each model utilized a heterogeneous graph structure. This graph was constructed with two node types: clients and domains. Features and label information for the client nodes were sourced directly from the “labeled features” file within the TI-16 DNS dataset package.

Due to the scarcity of benchmark datasets suitable for heterogeneous graphs with client and domain nodes, we prioritized established domain knowledge [14,34,35] over automated feature selection techniques like Random Forest or Chi-square. We avoided these statistical approaches because they assume the available data perfectly reflects real-world scenarios. With limited data, this assumption is often flawed, and features selected this way may fail in operational environments. Instead, we focused on known botnet behaviors [14], specifically how compromised nodes contact Command and Control (C2) servers via DNS after a secondary injection or system reboot. These nodes exhibit distinct DNS patterns regarding query counts, request frequency, and response rates. Guided by these behavioral indicators, we selected the six client features shown in Table 1 from the original twenty-four. A detailed list of features used for both client and domain nodes is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Client and Domain Name Node Features.

As detailed in Table 1, two features were used for the domain nodes. Second-Level Domain (SLD) and Top-Level Domain (TLD) components were utilized instead of Fully Qualified Domain Names (FQDNs). This adoption of the SLD + TLD format was a necessary constraint dictated by the structure of the input data. The domain names provided by the dataset exclusively contain SLD and TLD components, which mandated this specific representation. Consequently, for each SLD + TLD, the number of unique users who queried it within a given time window was derived from the ‘Request_File.csv’ files. The second domain node feature, the Maliciousness Score, was calculated using domain files supplied with the dataset. The TI-16 DNS dataset includes separate files detailing malicious domains (detected via DGArchive [36] and suspicious domains (those queried by users but absent from both DGArchive and the Alexa top one million). Furthermore, suspicious domains underwent N-gram analysis to identify those with a high probability of being DGA-generated. This information was used to generate the domain Maliciousness Scores, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Domain Name Maliciousness Score Criteria.

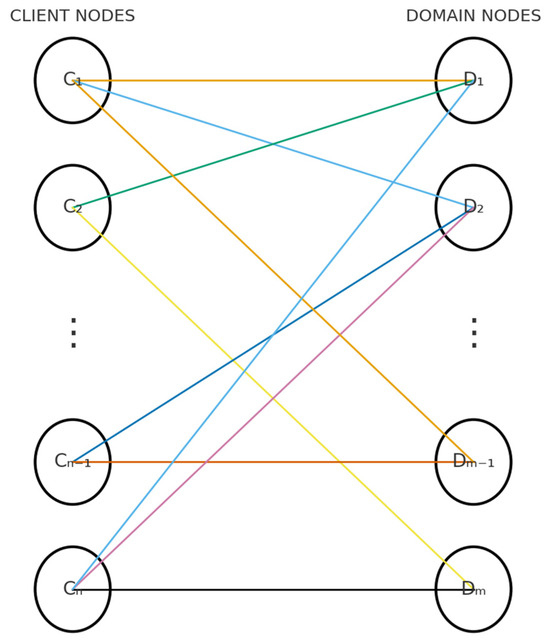

4.1. Heterogeneous Graph Construction

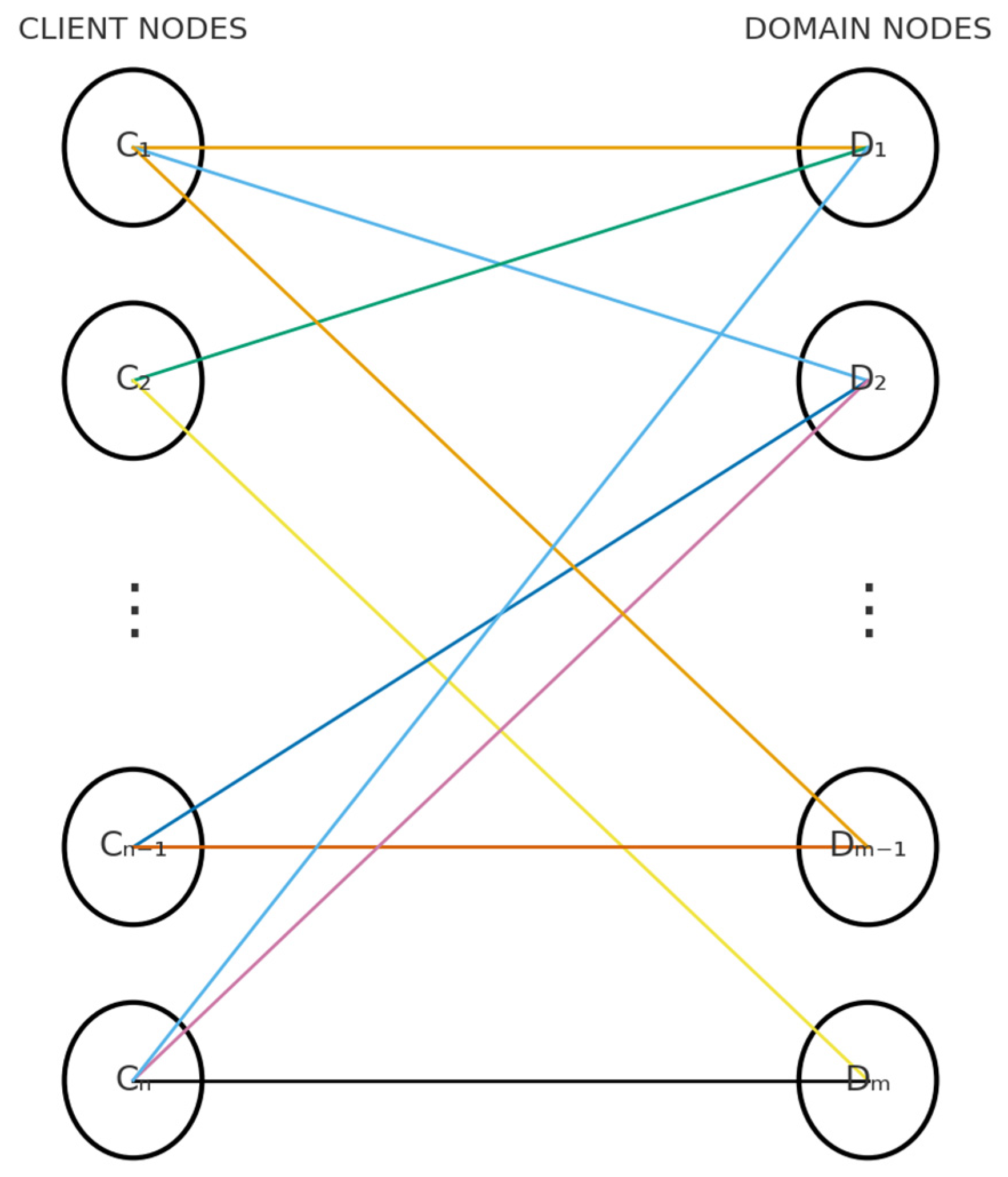

The problem is modeled as a heterogeneous graph structure, depicted in Figure 2. This structure is a bipartite graph comprising two distinct node types: clients and domains. Mathematically, the graph is defined by a set of node types, , and a set of edge types, , that connect them. The edge type represents a directed interaction, such as a client querying a domain. The model’s inputs consist of attribute matrices (), maintained separately for each node type, and a label vector (). The label vector () is available only for client nodes and is used to classify them as “normal” or “anomalous.” Domain nodes, in contrast, possess only attribute information.

Figure 2.

Sample Graph Structure.

To implement this structure, the HeteroData class from the PyTorch Geometric 2.8.0+cu126 (PyG) library was used. HeteroData allows the model to manage heterogeneity by storing data, such as attribute matrices and edge indices, separately for each node and edge type. To ensure bidirectional information flow, allowing GNN layers to propagate messages in both directions, reverse edges -specifically -, were incorporated into the graph in addition to the original relationship. The model’s architecture employs a two-layer GNN structure. This design enables each node to update its representation by gathering information from its 2-hop neighborhood. Consequently, a client can indirectly learn from other clients that are connected to the same domain.

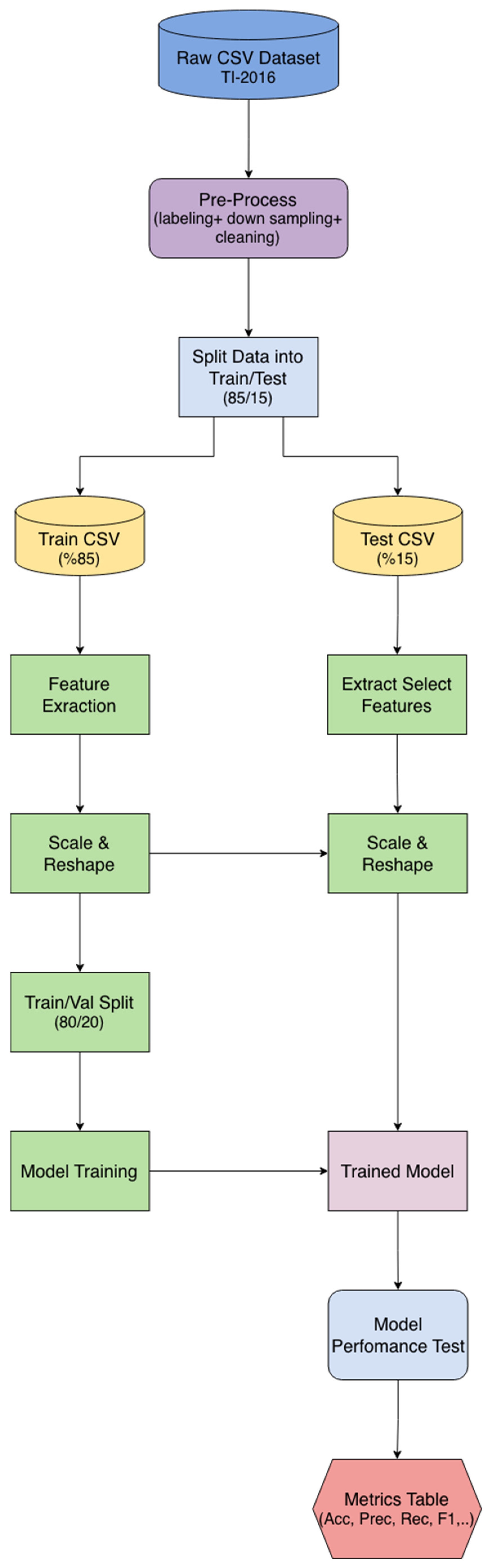

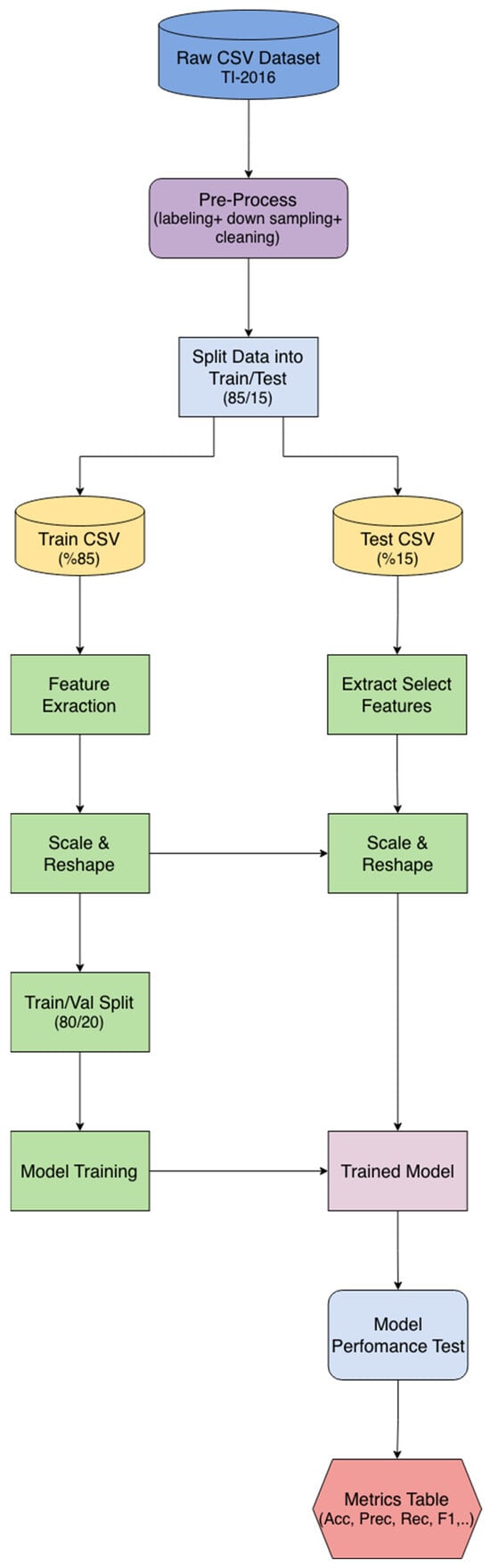

4.2. Detection Pipeline

Figure 3 illustrates the botnet node classification architecture employed in this study, which utilized the TI-2016 dataset. During the data pre-processing phase, the dataset first underwent labeling and cleaning procedures. Subsequently, a down-sampling technique was applied to mitigate potential biases arising from class imbalances among the network classes.

Figure 3.

Functional Block Diagram of the Botnet Node Classification Pipeline.

The complete pre-processed dataset was then partitioned into training and testing subsets, with 85% of the data allocated for training and 15% for testing. Within the dataset, the client features relevant to the classification task were identified, while a feature extraction process was concurrently performed for domain name nodes. The utilized client and domain features are listed in Table 1. Furthermore, the rationale for client feature selection and the methodology for domain feature extraction are detailed in Section 4. Both client and domain features underwent scaling and reshaping operations to standardize their format, facilitating more efficient model learning. The scaling coefficients derived exclusively from the training data were also applied during the testing procedure.

To effectively monitor model performance during development and prevent overfitting, the initial training set was further subdivided, allocating 80% for training and 20% for validation. Once the training phase was completed, the models were evaluated using the dedicated test dataset.

5. Performance Metrics

To quantitatively evaluate and compare the performance of the developed Graph Neural Network (GNN) models, standard classification metrics were employed. These metrics enabled a multi-faceted analysis of the models’ predictive capabilities. The foundational components for these metrics are defined as follows:

- True Positive (TP): The model correctly classifies a genuine bot account as “bot.”

- True Negative (TN): The model correctly classifies a genuine real user account as “real user.”

- False Positive (FP): The model incorrectly classifies a real user account as “bot” (Type I Error).

- False Negative (FN): The model incorrectly classifies a genuine bot account as “real user” (Type II Error).

These components were used to calculate the subsequent performance metrics.

- Accuracy

Accuracy represents the ratio of correct predictions to the total number of predictions made by the model. It serves as a fundamental metric for overall performance.

- Precision

Precision measures the proportion of positive classifications (i.e., accounts labeled as “bot”) that are genuinely bots. This metric assesses the reliability of a positive prediction. A high precision score indicates a low False Positive rate.

High precision is critically important in scenarios where the cost of erroneously labeling a real user as a bot (a False Positive) is substantial.

- Recall

Recall, also known as Sensitivity, measures the proportion of all actual bot accounts within the dataset that the model correctly identifies.

High recall is the priority metric in scenarios where the cost of failing to detect a malicious bot account (a False Negative) is substantial.

- F1-Score

The F1-Score is the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall. It provides a single, balanced measure of a model’s performance by considering both metrics.

- AUC

AUC, or Area Under the Curve, represents the area under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve. This metric evaluates the model’s ability to discriminate between positive and negative classes across all classification thresholds. The ROC curve is generated by plotting the True Positive Rate against the False Positive Rate at various threshold settings. An AUC value of 1.0 signifies a perfect classifier, whereas a value of 0.5 suggests performance no better than random guessing. AUC is a highly reliable comparison metric, particularly due to its robustness to class imbalance.

- Inference Time

Inference Time, while not a classification metric, is a performance characteristic that measures the model’s computational efficiency. It denotes the time required for the trained model to generate a prediction for a single data point. Low inference time is critical for systems that require rapid reaction, such as real-time bot detection. This value reflects the model’s complexity and its suitability for deployment in live operational systems.

6. Model Training and Testing

The architectures of the HeteroGAE, HeteroSAGE, HeteroGAT, and HeteroGCN models in this study were engineered to mitigate overfitting and enhance learning efficiency. The specifics of these approaches are detailed in this section. All GNN models were trained on a binary classification task, utilizing a sigmoid activation function in the output layer, the binary_crossentropy function for loss computation, and the Adam algorithm for optimization. Throughout the training process, the model’s validation performance was continuously monitored, and an early stopping criterion was activated to terminate training if no improvement was observed over a 100 number of consecutive epochs. To further improve performance and generalization, a Dropout layer with a rate of 0.3 was applied uniformly across all architectures.

The hyperparameters used in this study were determined through preliminary experiments. A two-layer message-passing structure was selected for all architectures to enable nodes to learn from neighborhood information up to two hops away, while avoiding the over-smoothing issue commonly observed in deeper GNNs.

Hidden layer dimensions were initially evaluated across a range of 64 to 256. Experiments prioritizing both training stability and validation F1 scores indicated that dimension sizes ranging from 64 to 96 for the first and second layers provided an optimal balance for each node type. This configuration was finalized as detailed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Architectural Characteristics of the Employed Models.

The learning rate was set to 0.001 for all models; higher rates resulted in fluctuations in the loss function, while lower rates led to slow convergence. To mitigate overfitting, L2 weight decay was applied at 1 × 10−4. Additionally, dropout rates were tested between 0.2 and 0.4, with results indicating that a rate in the 30–40% range effectively minimized the performance gap between training and validation.

Finally, to ensure a fair comparison across different architectures, these hyperparameter settings were standardized as much as possible for all models. The primary distinction between the HeteroSAGE, HeteroGCN, and HeteroGAT architecture lies in the specific convolution type employed within their message-passing layers (SAGEConv, GCNConv, and GATConv, respectively). In contrast, HeteroGAE utilizes a similar GNN structure for its encoder but incorporates an inner-product-based decoder to facilitate unsupervised representation learning. Consequently, the performance disparities observed on the test set can be attributed primarily to the underlying GNN architecture and structural variations rather than inconsistencies in training protocols or hyperparameter configurations.

The hyperparameters used for all models in this investigation are detailed in Table 3. Each model employed a two-layered structure with 256 and 128 neurons, respectively, using the ReLU activation function in the hidden layers. Additionally, all models were trained with a standardized learning rate of 0.001. This uniform methodology was implemented to ensure that observed performance differences are primarily attributable to variations in the models’ core architectural designs.

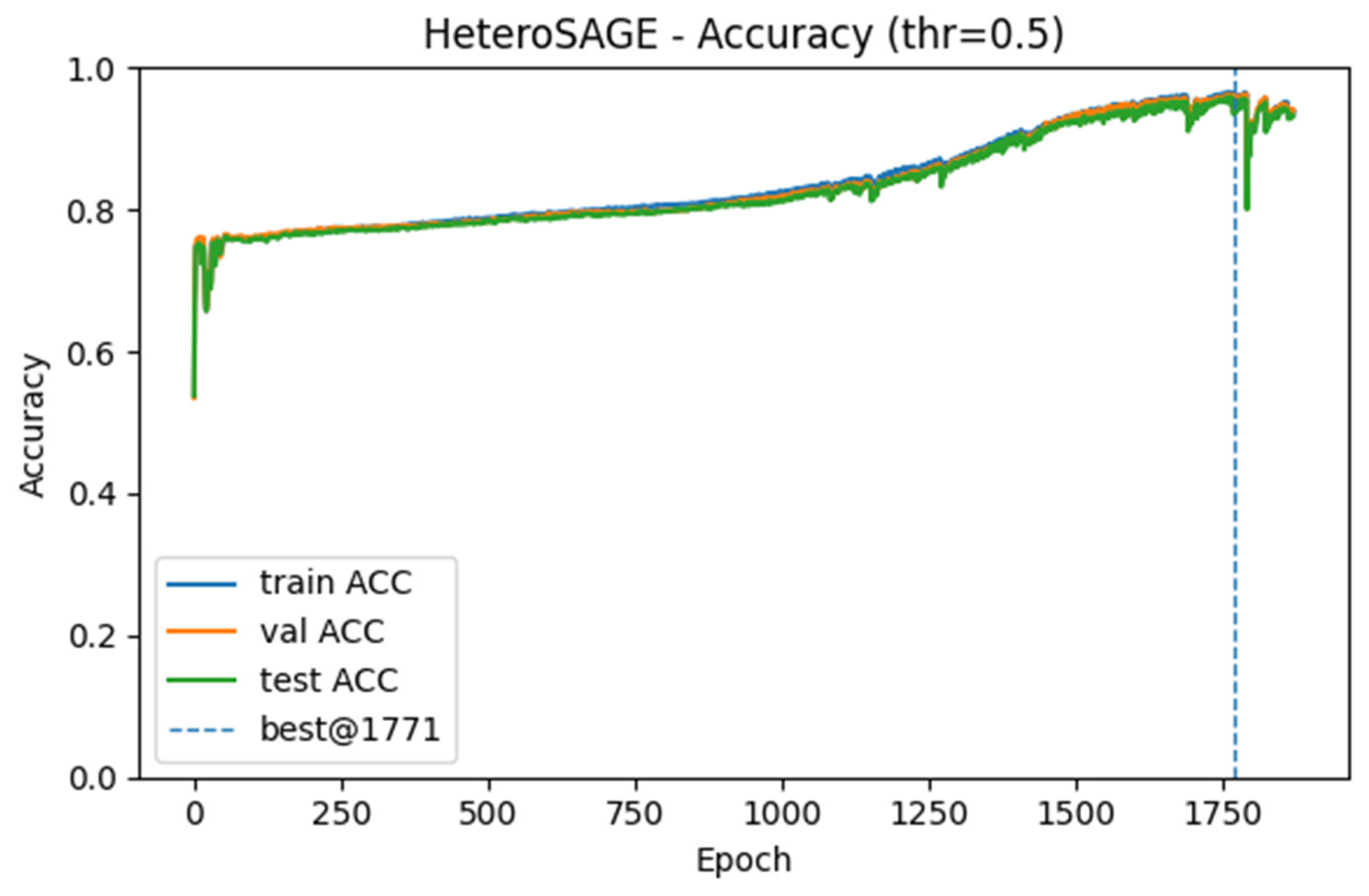

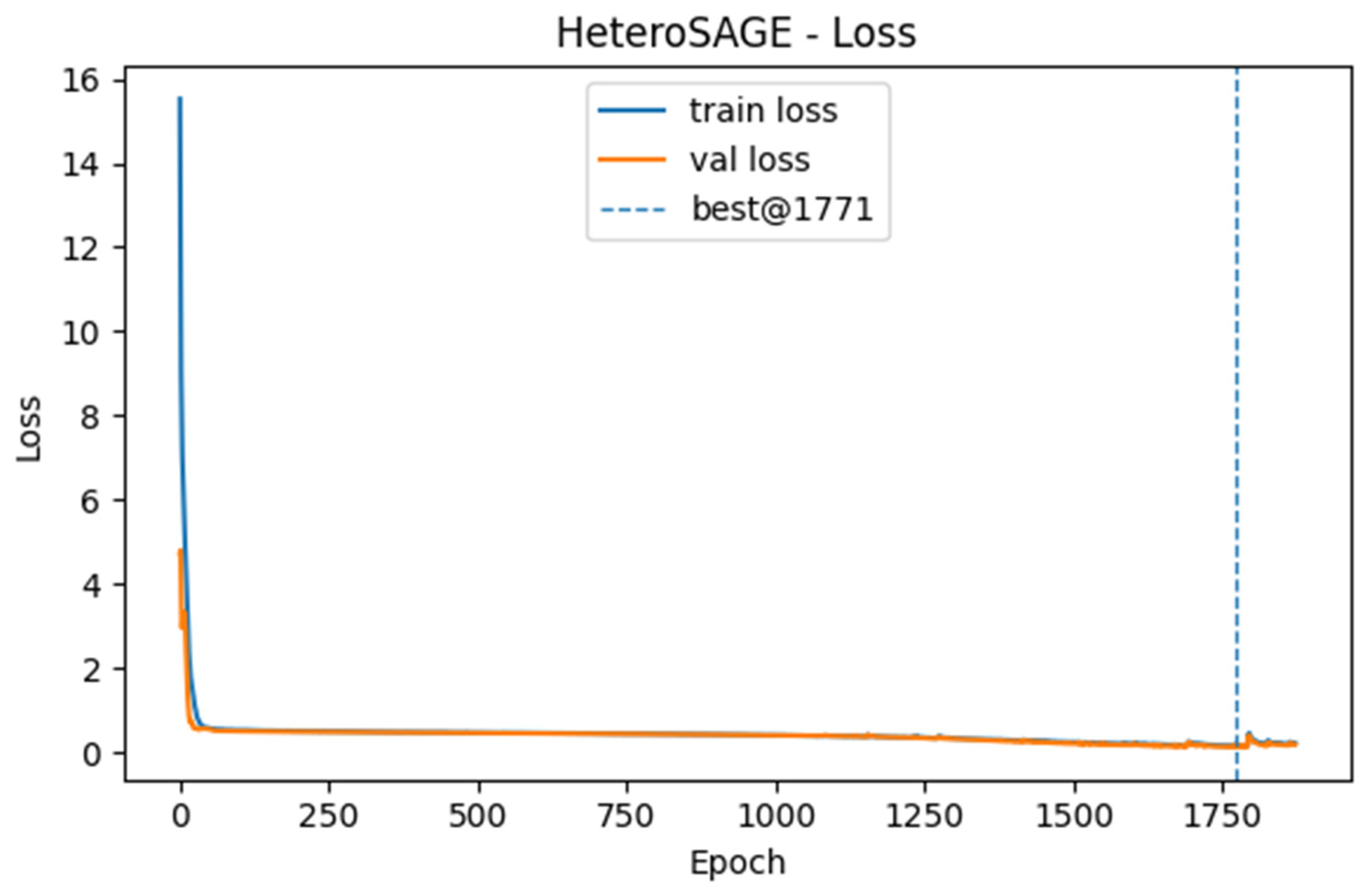

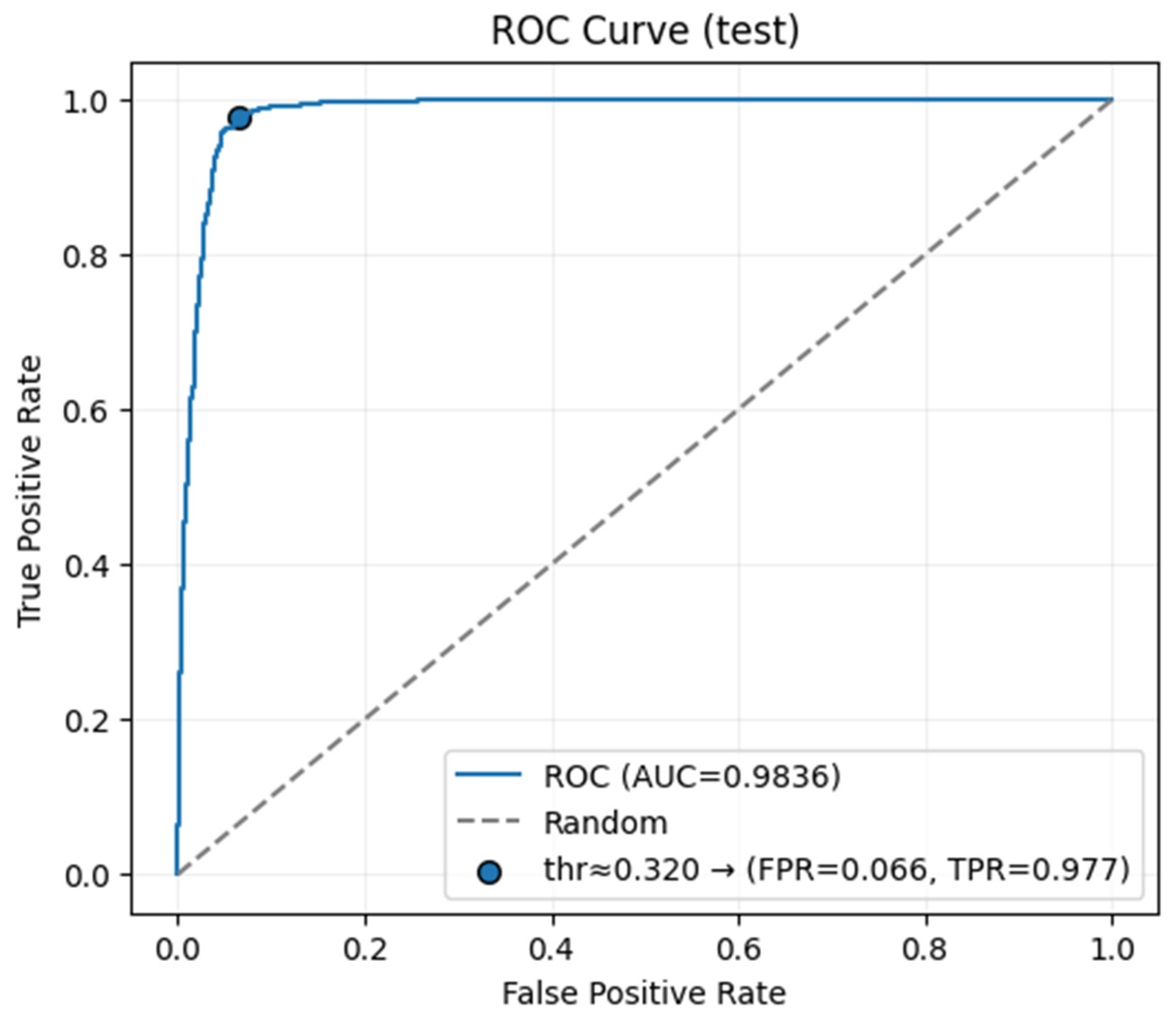

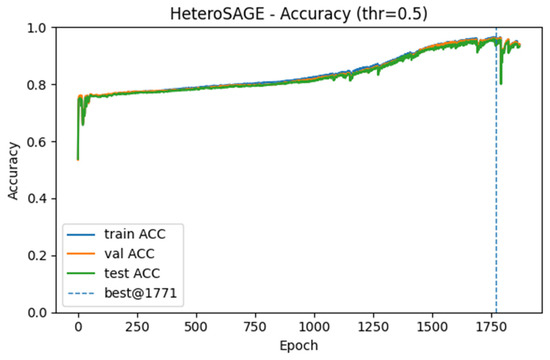

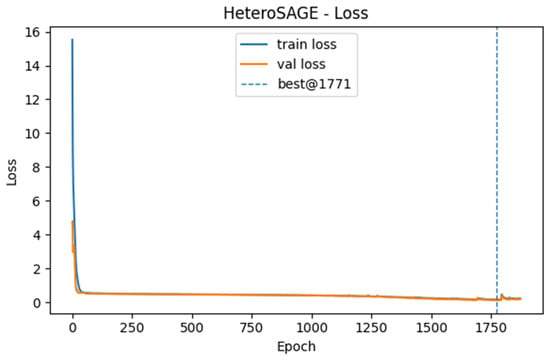

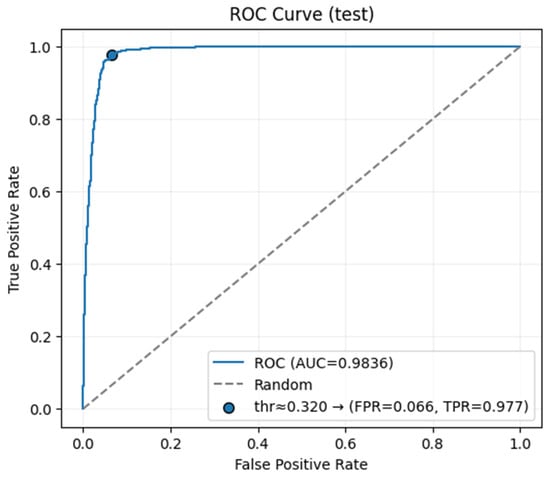

The learning dynamics, generalization, and classification performance of all models were analyzed using accuracy, loss, and Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves generated during training. Among the models tested, HeteroSAGE demonstrated the highest performance. Figure 4 and Figure 5 present the accuracy and loss curves for the HeteroSAGE model during training, while Figure 6 shows its final ROC curve on the test set. These figures collectively summarize the model’s comprehensive performance. To conserve space, the corresponding curves for the other models are provided in the Supplementary Materials. An examination of these figures reveals that the model consistently achieved high accuracy across the training, validation, and test datasets. Furthermore, the training and validation loss curves show a closely aligned, parallel decreasing trend from the early stages of training. This pattern indicates the model’s ability to generalize effectively without overfitting. Notably, the absence of divergence or a sudden increase in the validation loss curve confirms that the implemented strategies, such as the early stopping criterion reflected in the figures, successfully prevented overfitting. The model’s robust generalization is further substantiated by an Area Under the Curve (AUC) score of 0.9836 on the test data.

Figure 4.

Training and Validation Accuracy Curves for the HeteroSAGE Model.

Figure 5.

Training and Validation Loss Curves for the HeteroSAGE Model.

Figure 6.

ROC Curve for the HeteroSAGE Model on the Test Set.

7. Results

This study compared the performance of four distinct heterogeneous Graph Neural Network (GNN) models—HeteroSAGE, HeteroGAE, HeteroGCN, and HeteroGAT—using standard classification metrics. Table 4 summarizes the average test performance metrics and inference times, which were measured over 32 iterations.

Table 4.

Average Performance Metrics of the Models, Sorted by F1-Score.

With the F1-Score as the primary metric, HeteroSAGE achieved the highest performance (0.9560), while HeteroGAE also exhibited highly competitive results. Both models demonstrated consistently high performance across the F1-Score and Supplementary Metrics (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, and AUC). In contrast, the HeteroGCN and HeteroGAT models showed lower performance. Notably, HeteroGAT recorded the lowest F1-Score among all tested models and was also the slowest in terms of inference time. The other three models offered similar, more efficient processing durations.

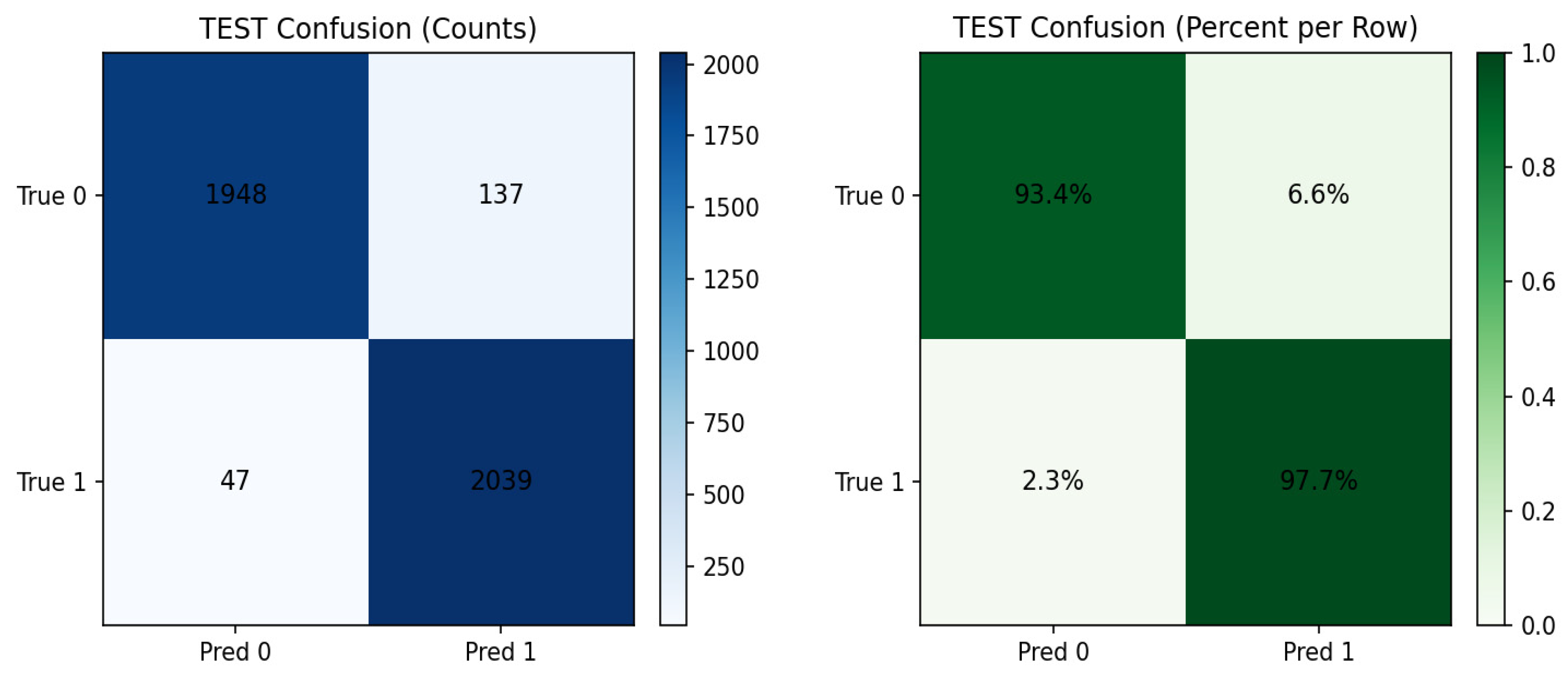

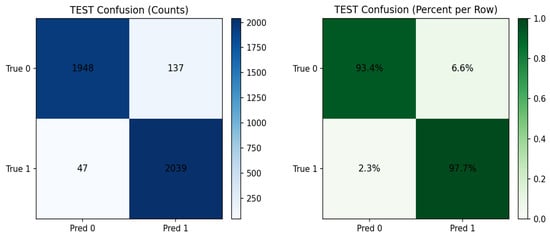

Figure 7 presents the confusion matrix for the HeteroSAGE model on the test set, allowing for a per-class evaluation of this top-performing model. The results indicate that the trained model was highly effective at detecting the target class, achieving a 97.7% detection rate and a very low false negative rate of 2.3%. Similarly, the model maintained a low false alarm rate of 6.6%. Confusion matrices for the other evaluated models are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 7.

Confusion matrices showing the classification performance of the HeteroSAGE model on the test data.

8. Discussion

Our results highlight the significantly superior performance of the HeteroSAGE and HeteroGAE models compared to HeteroGCN and HeteroGAT. This outcome suggests that the SAGE architecture’s feature aggregation strategy and the Graph Autoencoder’s (GAE) capacity to capture both graph structure and node embeddings are more beneficial for detection. Furthermore, the marginal performance difference between HeteroSAGE and HeteroGAE indicates that both approaches are highly suitable for this task.

Conversely, the models with simpler mechanisms—HeteroGCN (using basic neighborhood normalization) and HeteroGAT (using an attention mechanism to weight neighbors)—exhibited comparatively poorer results. Notably, the HeteroGAT model recorded both the lowest F1-Score and the highest inference time. This finding demonstrates that the added computational complexity of the attention mechanism did not yield a corresponding performance benefit for this dataset, underscoring that model complexity does not guarantee improved predictive performance.

An examination of the performance metrics reveals that the high F1-Scores from HeteroSAGE and HeteroGAE are coupled with exceptionally high Recall. This high Recall signifies the models’ substantial success in identifying the positive class, implying a very low rate of false negatives. This characteristic makes these models especially valuable in critical domains, such as anomaly detection, where failing to detect a positive instance carries significant consequences.

9. Conclusions

The effective detection of botnets remains a critical contemporary problem. Artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models (LLMs) have facilitated the design of sophisticated bots, leading to an estimated 37% of internet traffic being generated by malicious bots in 2024 [37]. Existing solutions in the literature often treat network traffic and user-specific data as independent variables, frequently neglecting the crucial interactions and relationships among network components and users during the detection process. This limitation is critical considering the potential for obfuscation and mimicry techniques, which pose a significant challenge in network defense. However, the inherent properties of our GNN approach, which processes this relational data, offer a strong natural defense against simple pattern-mimicry attacks.

Over the past decade, advances in AI and graph-based learning have enabled the effective inclusion of inter-component relationships and interactions in network anomaly studies. In this work, we addressed the gap by constructing a heterogeneous graph of user and domain nodes from collected Domain Name System (DNS) call data. We trained four distinct Graph Neural Network (GNN) models on this graph to identify bots within the network: HeteroGCN, HeteroSAGE, HeteroGAT, and HeteroGAE. Experimental results demonstrated that the developed models could identify bots with 95% accuracy.

Specifically, the results indicate that the HeteroSAGE and HeteroGAE models offered a statistically significant and practically important advantage over the other models for botnet node detection. These two models achieved superior performance, particularly regarding the F1-Score and Recall metrics. Furthermore, these models were observed to have rapid inference times, presenting an advantage not only in detection performance but also in operational processing speed. Conversely, the study revealed that the more complex and computationally expensive HeteroGAT model, which utilizes an attention mechanism, did not consistently deliver the best overall performance. Thus, this work serves as a valuable case study for researchers and practitioners selecting heterogeneous GNN models, clearly illustrating the trade-offs between architectural complexity, performance, and operational efficiency.

We thoroughly investigated the feasibility of utilizing publicly available datasets; our analysis revealed a lack of granularity often found in datasets designed for traditional, aggregated deep learning models. For instance, while the CTU-13 dataset [7] includes packet capture (pcap) files, significant portions of the data are truncated for privacy reasons. This limitation prevents the derivation of the flow information and domain node-level metrics necessary for constructing our relational graph structures. As a result, this study utilized a single dataset for evaluation. Future work should investigate the performance of these models on other heterogeneous graph datasets with varying topological features to enhance the generalizability of the findings. Additionally, a more comprehensive hyperparameter optimization and the inclusion of newer GNN architectures, such as Transformer-based models, in the comparison would yield valuable insights. To ensure the scalability of the proposed methods and their applicability to larger networks, future research could explore the division and processing of extensive graphs into subgraphs. Finally, an investigation into the changes in detection performance and processing time resulting from the quantization of model weights and scale factors would be beneficial.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010024/s1, File S1: Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, İ.Ö.; methodology, İ.Ö. and G.K.; formal analysis, İ.Ö. and G.K.; investigation, G.K.; writing—original draft preparation, İ.Ö. and G.K.; writing—review and editing, İ.Ö. and G.K.; visualization, İ.Ö. and G.K.; supervision, İ.Ö.; project administration, İ.Ö. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Doruk İletişim ve Otomasyon Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş. (DORUKNET) under funding number DRK.BGDT.DDOS.001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed at the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This material is based upon work supported by Doruk İletişim ve Otomasyon Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş. (DORUKNET). The authors gratefully acknowledge this support and take responsibility for the contents of this report. The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of Doruk İletişim ve Otomasyon Sanayi ve Ticaret A.Ş. (DORUKNET).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| GAE | Graph Auto-Encoder |

| GAT | Graph Attention Network |

| GCN | Graph Convolutional Network |

| HeteroGCN | Heterogeneous Graph Convolutional Network |

| HeteroGAT | Heterogeneous Graph Attention Network |

| HeteroSAGE | Heterogeneous GraphSAGE |

| HeteroGAE | Heterogeneous Graph Auto-Encoder |

| F1-Score | Harmonic mean of Precision and Recall |

| AUC | Area Under the (ROC) Curve |

| ROC | Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| DDoS | Distributed Denial-of-Service |

| FQDN | Fully Qualified Domain Name |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| pcap | Packet Capture file format |

| DNS | Domain Name System |

| SLD | Second-Level Domain |

| TI-16 | Threat Intelligence 2016 DNS dataset |

| DGA | Domain Generation Algorithm |

References

- Barracuda. Top Threats of the 2024 Botnet Landscape. Available online: https://blog.barracuda.com/2025/03/21/top-threats-of-the-2024-botnet-landscape (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Xing, Y.; Shu, H.; Zhao, H.; Li, D.; Guo, L. Survey on Botnet Detection Techniques: Classification, Methods, and Evaluation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 6640499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgoulias, D.; Pedersen, J.M.; Falch, M.; Vasilomanolakis, E. Botnet business models, takedown attempts, and the darkweb market: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alieyan, K.; Almomani, A.; Manasrah, A.; Kadhum, M.M. A Survey of Botnet Detection Based on DNS. Neural Comput. Appl. 2015, 28, 1541–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, M.; Kaur, S. Issues and Challenges in DNS Based Botnet Detection: A Survey. Comput. Secur. 2019, 86, 28–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Singh, M.; Kaur, S. TI-16 DNS Labeled Dataset for Detecting Botnets. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 62616–62629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, S.; Grill, M.; Stiborek, J.; Zunino, A. An empirical comparison of botnet detection methods. Comput. Secur. 2014, 45, 100–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagraa, S.; Husák, M.; Seba, H.; Vuppala, S.; State, R.; Ouedraogo, M. A review on graph-based approaches for network security monitoring and botnet detection. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2023, 23, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagraa, S.; François, J.; Lahmadi, A.; Miner, M.; Hammerschmidt, C.; State, R. BotGM: Unsupervised graph mining to detect botnets in traffic flows. In Proceedings of the 2017 1st Cyber Security in Networking Conference (CSNet), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 18–20 October 2017; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Paschalidis, I.C. Botnet detection using social graph analysis. In Proceedings of the 2014 52nd Annual Allerton Conference on Communication, Control, and Computing (Allerton), Monticello, IL, USA, 30 September–3 October 2014; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Liu, X.; Yan, Q.; Li, B.; Shao, M.; Peng, H. Multi-attributed heterogeneous graph convolutional network for bot detection. Inf. Sci. 2020, 537, 380–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, K.; Yang, H.; Li, R.; Chen, W.; Luo, X.; Yin, L. Distributed Detection of Large-Scale Internet of Things Botnets Based on Graph Partitioning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Lang, B.; Yan, Y.; Liu, Y. Deeply fused flow and topology features for botnet detection based on a pretrained GCN. Comput. Commun. 2025, 233, 108084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özçelik, İ.; Brooks, R. Distributed Denial of Service Attacks: Real-World Detection and Mitigation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, S.; Zain, J.M.; Zolkipli, F.; Inayat, Z. A review paper on botnet and botnet detection techniques in cloud computing. In Proceedings of the ISCI (2014), 2014 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communication (ISCC), Funchal, Portugal, 23–26 June 2014; pp. 28–29. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, D.; Bruno, S.; Nuno, A. MONDEO: Multistage Botnet Detection. arXiv 2013, arXiv:2308.16570. [Google Scholar]

- Sousa, B.; Dias, D.; Antunes, N.; Cámara, J.; Wagner, R.; Schmerl, B.; Garlan, D.; Fidalgo, P. MONDEO-Tactics5G: Multistage Botnet Detection and Tactics for 5G/6G Networks. Comput. Secur. 2024, 140, 103768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, H.G.; Kumar, J.; Nandish, M. Host-Level Botnet Detection via Internet DNS Traffic Analysis Using Neural Networks. Internet Technol. Lett. 2025, 8, e70101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasrah, A.M.; Khdour, T.; Freehat, R. DGA-Based Botnets Detection Using DNS Traffic Mining. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2022, 34, 2045–2061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilot, T.; El Madhoun, N.; Al Agha, K.; Zouaoui, A. Graph Neural Networks for Intrusion Detection: A Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 49114–49139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Lin, M.; Zhang, C.; Xu, Z. A Survey on Graph Neural Networks for Intrusion Detection Systems: Methods, Trends and Challenges. Comput. Secur. 2024, 141, 103821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Ryan, R.; Li, Q.; Ferdosian, N. A Survey of Heterogeneous Graph Neural Networks for Cybersecurity Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.26307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrukh, Y.A.; Wali, S.; Khan, I.; Bastian, N.D. XG-NID: Dual-Modality Network Intrusion Detection using a Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network and Large Language Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Li, Y. XMF-GNN: A Cross-modality Dynamic Fusion Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network for Network Intrusion Detection. Neurocomputing 2025, 655, 131285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.W.; Kulatilleke, G.; Sarhan, M.; Layeghy, S.; Portmann, M. XG-BoT: An Explainable Deep Graph Neural Network for Botnet Detection and Forensics. Internet Things 2022, 22, 100747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altaf, T.; Wang, X.; Ni, W.; Yu, G.; Liu, R.P.; Braun, R. GNN-Based Network Traffic Analysis for the Detection of Sequential Attacks in IoT. Electronics 2024, 13, 2274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, W.W.; Layeghy, S.; Sarhan, M.; Gallagher, M.; Portmann, M. E-GraphSAGE: A Graph Neural Network based Intrusion Detection System for IoT. In Proceedings of the NOMS 2022–2022 IEEE/IFIP Network Operations and Management Symposium (2021), Budapest, Hungary, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Chasaki, D. Heterogeneous GNN with Express Edges for Intrusion Detection in Cyber-Physical Systems. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Computing, Networking and Communications (ICNC) (2024), Big Island, HI, USA, 19–22 February 2024; pp. 523–529. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Gu, Y.; Zhao, Q. One-Class Directed Heterogeneous Graph Neural Network for Intrusion Detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Innovation in Artificial Intelligence (ICIAI ’22), Guangzhou, China, 4–6 March 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Velickovic, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, W.L.; Ying, R.; Leskovec, J. Inductive Representation Learning on Large Graphs. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1706.02216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na Cho, H.; Ahn, I.; Gwon, H.; Kang, H.J.; Kim, Y.; Seo, H.; Choi, H.; Kim, M.; Han, J.; Kee, G.; et al. Heterogeneous Graph Construction and HinSAGE Learning from Electronic Medical Records. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 21152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Variational graph auto-encoders. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1611.07308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthew, T.; Mohaisen, A. Kindred domains: Detecting and clustering botnet domains using DNS traffic. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on World Wide Web, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 7–11 April 2014; pp. 707–712. [Google Scholar]

- Villamarin-Salomon, R.; Brustoloni, J.C. Identifying botnets using anomaly detection techniques applied to DNS traffic. In Proceedings of the 2008 5th IEEE Consumer Communications and Networking Conference, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 10–12 January 2008; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 476–481. [Google Scholar]

- Plohmann, D. DGArchive. Fraunhofer FKIE. 2018. Available online: https://dgarchive.caad.fkie.fraunhofer.de/ (accessed on 15 March 2021).

- Thales. Artificial Intelligence Fuels Rise of Hard-to-Detect Bots that Now Make up More Than Half of Global Internet Traffic, according to the 2025 Imperva Bad Bot Report. Available online: https://cpl.thalesgroup.com/about-us/newsroom/2025-imperva-bad-bot-report-ai-internet-traffic (accessed on 30 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.