Abstract

This review examines the impact of data analytics powered by the Internet of Things (IoT), edge computing, and artificial intelligence (AI) on improving energy efficiency in smart environments, with a focus on smart factories, smart cities, and smart territories. Advanced AI, machine learning (ML), and deep learning (DL) techniques enable real-time energy optimization and intelligent decision-making in complex, data-intensive systems. Integrating edge computing reduces latency and improves responsiveness in IoT and Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT) networks, enabling local energy management and reducing grid load. Federated learning further enhances data privacy and efficiency by enabling decentralized model training across distributed smart nodes without exposing sensitive information or personal data. Emerging 5G and 6G technologies provide the necessary bandwidth and speed for seamless data exchange and control across energy-intensive, connected infrastructures. Blockchain increases transparency, security, and trust in energy transactions and decentralized energy trading in smart grids. Together, these technologies support dynamic demand response mechanisms, predictive maintenance, and self-regulating systems, leading to significant improvements in energy sustainability. Case studies of smart cities and industrial ecosystems within Industry 4.0/5.0/6.0 demonstrate measurable reductions in energy consumption and carbon emissions through these synergistic approaches. Despite significant progress, challenges remain in interoperability, scalability, and regulatory frameworks. This review demonstrates that AI-based edge computing, supported by robust connectivity and secure IoT and IIoT architectures, has a transformative potential for creating energy-efficient and sustainable smart environments.

1. Introduction

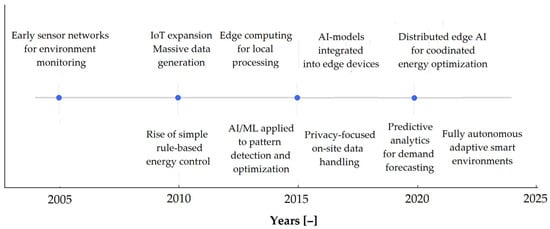

The genesis of artificial intelligence (AI)-based data analytics in smart environments began with the growing availability of sensor networks capable of monitoring temperature, lighting, occupancy, and energy consumption in real time [1]. Early systems relied on simple rule-based control, but the explosion of Internet of Things (IoT) devices in the 2010s created massive, complex datasets that required more advanced analysis [2]. AI and machine learning (ML) have become powerful tools for detecting patterns, predicting consumption trends, and optimizing resource allocation, beyond the capabilities of static algorithms [3]. Simultaneously, the need for faster decision-making and lower data transmission costs has spurred the development of edge computing, where processing occurs closer to the data source [4]. This local processing not only reduced network latency but also improved privacy by storing sensitive building and occupancy data on-site [5,6]. Researchers have begun integrating AI models with edge devices, enabling smart meters, heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) controllers, and lighting systems to autonomously adjust settings in real time [7]. Predictive analytics has become a cornerstone, enabling systems to forecast demand peaks, adjust load schedules, and more efficiently integrate renewable energy sources [8]. Edge AI has further enabled distributed coordination between devices, supporting swarm-level energy optimization across entire smart campuses or districts [9,10]. The synergy between AI-based analytics and edge computing has transformed energy management from a centralized, reactive process to a decentralized, proactive ecosystem [11]. Today, this combination is powering next-generation smart environments that combine comfort, savings, and sustainability through continuous, intelligent adaptation (Figure 1). This also creates new opportunities for the future, which will be discussed in more detail later in this article.

Figure 1.

Evolution of AI-based data analytics and edge computing for energy efficiency in smart environments (own version).

The aim of this review is to answer the question in which areas and why AI-based data analysis and edge computing are needed, or even essential, from an economic, social, legal, and ethical perspective to increase energy efficiency in smart environments. This is part of the complex issue of energy transition, where, as the failure to widely deploy electric vehicles demonstrates, technological accessibility may not be the primary consideration, and social acceptance and economics may be decisive.

Concise, scientific problem statements covers the impact of AI-based data analytics and edge computing on energy efficiency in smart environments, along with application areas and methods (see also Table 1). In smart grids, real-time load forecasting can be addressed using AI methods such as DL and reinforcement learning to optimize demand response strategies at the grid edge. In smart buildings, energy forecasting and adaptive HVAC control remain open problems, where anomaly detection and AI-based reinforcement learning can minimize losses while ensuring occupant comfort. In intelligent transportation systems, traffic flow optimization and vehicle routing require AI-based graph neural networks and federated learning deployed at the grid edge to reduce fuel and electricity consumption. In renewable energy integration, forecasting solar and wind power generation under uncertainty is a challenge that can be addressed using hybrid AI models (e.g., LSTM + physics-based networks) to improve grid stability and energy efficiency. In industrial IoT environments, optimizing energy consumption on production lines requires AI-based predictive maintenance and scheduling algorithms deployed on edge devices to minimize downtime and energy consumption. In data centers, cooling optimization and load balancing remain unsolved, and AI methods such as reinforcement learning and unsupervised clustering can reduce power utilization efficiency (PUE). In smart healthcare environments, continuous patient monitoring generates large data streams, requiring edge AI analytics with federated learning to reduce energy-intensive data transmission. In smart agriculture, precision irrigation and energy-efficient greenhouse control can benefit from AI-based decision trees, reinforcement learning, and sensor fusion techniques at the edge. In urban energy management, the challenge of optimizing energy from multiple sources (solar, grid, electric vehicles) can be addressed using multi-agent reinforcement learning and distributed edge analytics. In cyber-physical security of smart environments, the detection and mitigation of energy-intensive cyberattacks can be improved by leveraging AI-based detection and blockchain-integrated edge intelligence.

Table 1.

AI applicationsfor energy efficiency in smart environments.

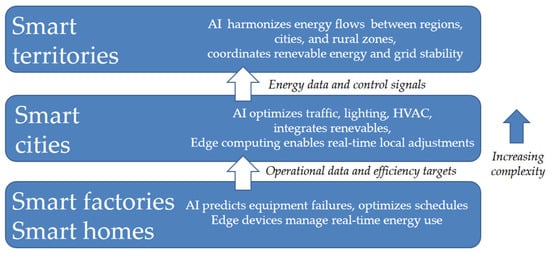

In smart factories, AI-based data analytics process data streams from machine sensors, predicting equipment failures and enabling predictive maintenance that reduces unnecessary energy waste [11]. Real-time AI-based optimization of production and machine schedules at the grid edge minimizes downtime and adjusts energy consumption to meet demand peaks [12,13]. In smart cities, AI-based traffic and lighting systems analyze mobility patterns to reduce congestion and dynamically adjust street lighting, reducing electricity consumption. Edge computing enables these changes to be implemented locally, providing a rapid response to changes in real time without overloading central servers [14,15]. Urban HVAC and heating systems use AI predictions to balance comfort and efficiency by integrating renewable energy sources such as solar and wind. In smart territories—large, interconnected regions—AI analytics harmonizes energy flows between cities, industrial zones, and rural areas to prevent congestion and optimize grid stability [16]. Edge computing in remote areas enables local decision-making, enabling rural energy microgrids to operate autonomously while coordinating with central systems [17]. Predictive analytics in these areas supports better integration of renewable energy, reducing variability and maximizing green energy utilization [18]. By processing data locally, edge computing reduces communication latency and bandwidth requirements, which are essential for optimizing energy consumption at scale [19,20]. Together, AI-based analytics and edge computing create a layer of distributed intelligence that transforms smart environments into adaptive, energy-efficient ecosystems (Figure 2) [21,22].

Figure 2.

Way of interaction between AI-based data analytics and edge computing across smart factories, smart cities, and smart territories to improve energy efficiency.

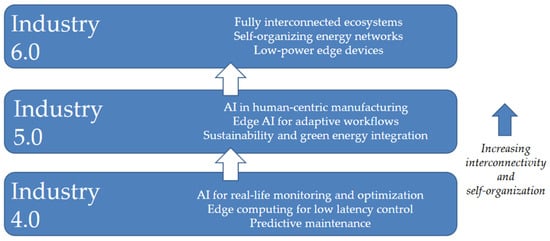

In Industry 4.0, AI-based data analysis enables real-time monitoring of industrial processes, identifying inefficiencies, and optimizing machine operation to reduce energy consumption [23,24]. Edge computing in this paradigm supports rapid decision-making directly on the shop floor, minimizing latency and grid dependence for energy control. AI-based predictive maintenance reduces downtime and prevents energy waste caused by faulty or inefficient equipment [25,26]. As we transition to Industry 5.0, AI-based energy optimization is expanding to human-centric production, where collaborative robots adapt their operations to human work rhythms and reduce idle energy consumption [27]. Edge AI enables local decision-making in hybrid human–machine processes, enabling more adaptive and personalized energy-saving strategies [28]. AI analytics in Industry 5.0 also integrates sustainability goals, dynamically balancing productivity with environmental impact by prioritizing green energy [29,30]. In the emerging vision of Industry 6.0, AI and edge computing operate within fully connected ecosystems of factories, cities, and territories, sharing real-time energy information [31]. This paradigm leverages self-organizing networks of machines and infrastructure that autonomously negotiate energy consumption based on global and local demand [32]. Low-power edge devices in Industry 6.0 may enable massive, near-instantaneous optimization of distributed energy systems [33,34]. In all three paradigms, the synergy of AI-based analytics and edge computing shifts energy management from static, reactive control to a dynamic, self-optimizing system that supports resilience, sustainability, and efficiency [35]. Evolution of AI and edge computing roles from Industry 4.0 to Industry 6.0, highlights the shift from real-time optimization and predictive maintenance to fully interconnected, self-organizing energy ecosystems (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Evolution of AI and edge computing roles from Industry 4.0 to Industry 6.0.

We summarized the significant shortcomings that need to be addressed regarding the impact of AI-based data analytics and edge computing on energy efficiency in smart environments. The integration of AI-based data analytics in smart environments has demonstrated the potential to optimize energy efficiency, but theoretical frameworks often ignore the trade-off between computational accuracy and energy consumption. Existing models primarily focus on performance metrics such as prediction accuracy and latency, while energy-aware optimization goals remain underexplored in formal AI design. Edge computing promises to reduce communication costs through localized data processing, but its theoretical limitations in terms of resource allocation, load balancing, and device heterogeneity have not been fully addressed. Current AI methods used in energy management often assume abundant, high-quality datasets, whereas real-world smart environments are characterized by data sparsity, missing values, and non-stationary distributions. The theoretical foundations of federated and distributed learning lack robust models for the tradeoffs between energy, privacy, and latency, leading to inefficiencies in practical implementation. Most energy forecasting and optimization models rely on centralized architectures, ignoring the mathematical complexity of decentralized, multi-agent decision-making required in large-scale smart cities. There is a lack of theoretical work on integrating physics-based energy system models with artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms, resulting in “black-box” predictions that are uninterpretable and robust to uncertainty. Anomaly detection and self-healing frameworks for edge devices remain underdeveloped, and their theoretical contribution to fault-tolerant AI models for energy resilience is limited. Security-oriented AI frameworks do not fully theorize the energy costs of cyberdefense mechanisms, leading to potential efficiency tradeoffs in smart environments. The lack of comprehensive theoretical models for scalability, interpretability, and energy trade-offs in AI integration with edge computing remains a significant drawback that hinders the implementation of energy-efficient solutions in real-world settings.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dataset

This bibliometric study was undertaken to assess the current landscape of research, knowledge, and practical applications related to artificial intelligence–driven data analysis and edge computing aimed at improving energy efficiency in smart environments. Established and widely recognized bibliometric techniques were applied to identify and evaluate recent global scientific literature published within the last decade (2016–2025). The inclusion criteria comprised original research articles and review papers written in English, including full-text conference proceedings and book chapters that were open access and indexed in major bibliometric databases such as Web of Science (WOS), Scopus, PubMed, and DBLP. Excluded from the review were publications in languages other than English, non-article formats (e.g., reports, abstracts), and works lacking full open-access text. The three focused research questions are consistent with AI-based data analysis and edge computing in the field of energy efficiency in smart environments:

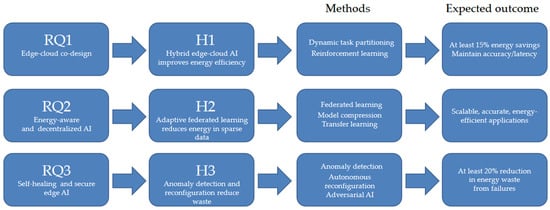

- RQ 1: How can AI-based data analytics and edge computing be combined to balance computational accuracy, latency, and energy consumption in heterogeneous smart environments?

- RQ 2: What new AI frameworks and algorithms can effectively integrate energy awareness, data distribution, and decentralized decision-making to improve application scalability in smart environments?

- RQ 3: How can self-healing, fault-tolerant, and secure edge AI systems be developed to maintain energy efficiency while mitigating failures, anomalies, and cyber threats in smart environments?

Hypotheses (Hs) addressing the three RQs mentioned above are following:

- Hypothesis 1 (H1): A hybrid edge–cloud AI architecture that dynamically partitions computations based on context-sensitive energy constraints will achieve higher overall energy efficiency (≥15% improvement) without significantly reducing accuracy or increasing latency;

- H2: Energy-aware AI models using adaptive learning (e.g., federated learning with model compression and data transfer) can maintain scalability and accuracy in distributed and heterogeneous data environments while reducing energy consumption compared to centralized approaches;

- H3: Embedding anomaly detection and autonomous reconfiguration mechanisms into edge AI systems will increase fault tolerance and cybersecurity, thereby reducing energy losses due to failures or attacks by at least 20% compared to conventional edge deployments.

We further highlight major aspects of the field, including the present status of research, the sources of publications (such as institutions, countries, and funding bodies), the most impactful contributors (leading authors and research groups), and, where applicable, recent trends and shifts in research topics within the studied scientific domain:

- Evolution of research topics/issues over time;

- Geographical distribution of research locations/publications, authors, their affiliations/research institutions, and publications with the greatest impact;

- Topics that may shape future research programmes, worthy of wider interest from researchers and investment in grants.

This aspect is especially significant for our research outcomes given the rapid and ongoing changes in the fields of artificial intelligence, green technologies, and sustainable development, all of which strongly influence AI-based data analysis and edge computing for energy efficiency in smart environments. Additionally, where feasible, efforts were made to identify the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) linked to the publications reviewed, reflecting a global transition toward a 2030-oriented future that prioritizes environmental protection and improved quality of life for future generations. This analytical approach enables a more comprehensive understanding of both historical and current research directions and their pace of development, as well as related economic, social, legal, and ethical trends. Indirectly, it also sheds light on business strategies and practices that rely on machine learning in the advancement of AI-driven data analysis and edge computing technologies for energy-efficient smart environments. Such an approach supports deeper insight and more effective planning of future development activities in the field, while facilitating better alignment of emerging researchers’ potential with technological and regulatory needs, taking into account the broader social context of proposed changes—including the growing importance of societal acceptance for successful implementation. Considering the evolving paradigms of Industry 4.0 (automation, robotics, and end-to-end technical control), Industry 5.0 (human-centric and environmentally focused development), and Industry 6.0 (enhanced human involvement in production, sustainability, and resilient supply chains), there is a clear need to more thoroughly understand current development processes and to strengthen their potential through contemporary research. A forward-looking interpretation of relevant bibliometric data can therefore enrich scholarly discourse, including interdisciplinary dialogue, and provide a robust foundation for future research aimed at developing innovative solutions.

2.2. Methods

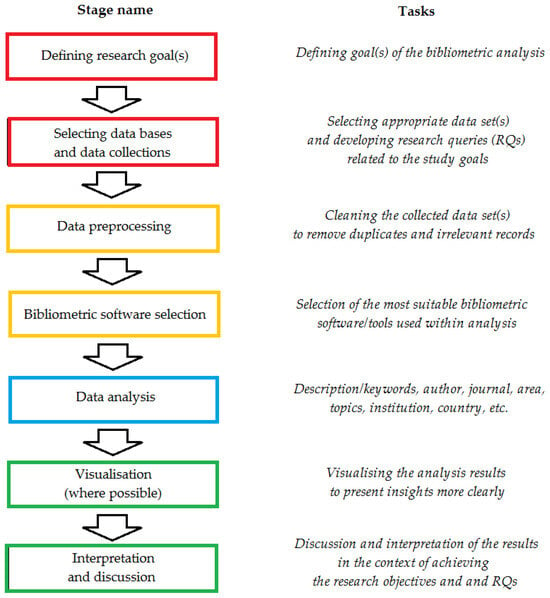

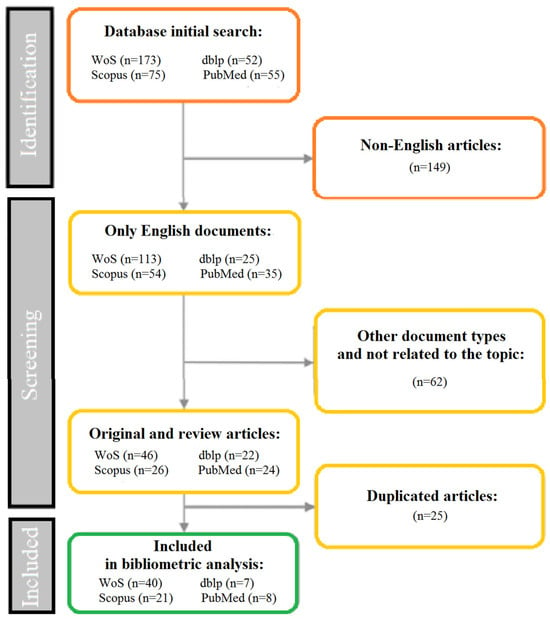

This research employed a structured and purpose-driven search across four major bibliographic databases: Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, PubMed, and DBLP. Using this combination ensured the broadest possible coverage of relevant studies and provided a rich body of globally significant data for advancing knowledge and its practical applications (Figure 4 and Figure 5). To efficiently identify the most relevant records, suitable filters were applied, limiting the results to English-language publications. Following this initial screening, each article was independently reassessed by three experts to confirm compliance with the inclusion criteria, thereby establishing the final dataset. The dataset was then examined with respect to its key attributes, such as the most prominent authors and research groups, affiliated institutions, countries of origin, sources of funding (when reported), scientific disciplines, and subject categories. This analysis enabled the identification of major research contributions within the field and the detection of emerging trends, some of which diverged from initial expectations. Where feasible, temporal patterns were analyzed to observe how the field has evolved over time, and publications were organized into thematic clusters to uncover connections among different research domains. This approach brought to light significant themes and subareas, including those that are still in the early stages of development.

Figure 4.

Bibliometric analysis procedures (own approach).

Figure 5.

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

- To enhance the reproducibility and comparability of this review, ten selected components of the PRISMA 2020 guidelines for systematic reviews [36] were adopted. Their application supported a clearer and more transparent organization of the research procedure. The analysis concentrated on the following PRISMA 2020 elements, which are detailed in the Supplementary Materials:

- Item 3: justification;

- Item 4: objective(s);

- Item 5: eligibility criteria;

- Item 6: sources of information;

- Item 7: search strategy;

- Item 8: selection process;

- Item 9: data collection process;

- Item 13a: synthesis methods;

- Item 20b: synthesis results;

- Item 23a: discussion.

The use of the PRISMA 2020 partial review is important because the field of IoT-based data analytics, edge computing, and AI in the context of energy efficiency is highly interdisciplinary and methodologically heterogeneous. Partial PRISMA enables a systematic yet flexible literature mapping, allowing for the identification of scattered research results published in computer science, energy, and environmental engineering. Unlike a full systematic review, the partial approach is appropriate when studies include diverse types of evidence (case studies, simulations, testbeds) that are difficult to compare quantitatively. The PRISMA 2020 framework supports transparent reporting of search and selection criteria, reducing the risk of omitting relevant but niche studies. By focusing on key elements (e.g., data sources, analytical methods, computational architectures), it is possible to identify topical gaps rather than aggregating efficiency results. Partial review allows for the identification of under-researched relationships between edge-based analytics and real energy savings in smart environments. This approach also facilitates the assessment of the maturity of AI methods, revealing gaps in model validation in real-world conditions. PRISMA 2020 provides a framework for comparing research trends over time, helping to identify rapidly developing and neglected areas. Partial systematic mapping supports the formulation of precise research questions for future empirical and experimental studies. Consequently, the use of the partial (10-item) PRISMA 2020 review is crucial for reliably identifying and filling research gaps in the rapidly evolving field of smart, energy-efficient environments.

This review makes use of bibliometric analysis tools integrated within the WoS, Scopus, PubMed, and DBLP databases. The chosen methodological approach enables accurate and consistent classification of publications by authors, institutional affiliations, keywords, research domains, document types, and source outlets across all four databases. The analytical outcomes are then presented and visualized to deliver a thorough and coherent overview that reflects the complexity of the subject matter.

3. Results

3.1. Data Sources

To refine the search within the selected databases, filtered queries were applied, restricting the results to English-language publications released between 2016 and 2025. The search strategy was implemented as follows:

- In the WoS database, the “Subject” field—encompassing the title, abstract, keywords, and additional keyword fields—was utilized;

- In the Scopus database, searches were performed using the article title, abstract, and keywords;

- In the PubMed and DBLP databases, manually defined keyword sets were employed.

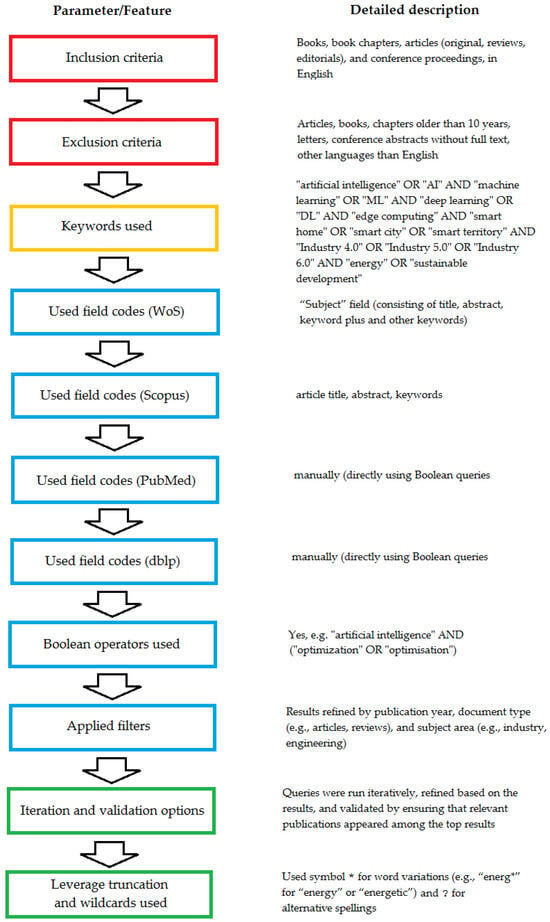

Across all databases, articles were retrieved using keywords such as “artificial intelligence” OR “AI,”“machine learning” OR “ML,”“deep learning” OR “DL” AND “edge computing” AND “smart home” OR “smart city” OR “smart territory” AND “Industry 4.0” OR “Industry 5.0” OR “Industry 6.0” AND “energy” OR “sustainable development” (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Databases search query (own version).

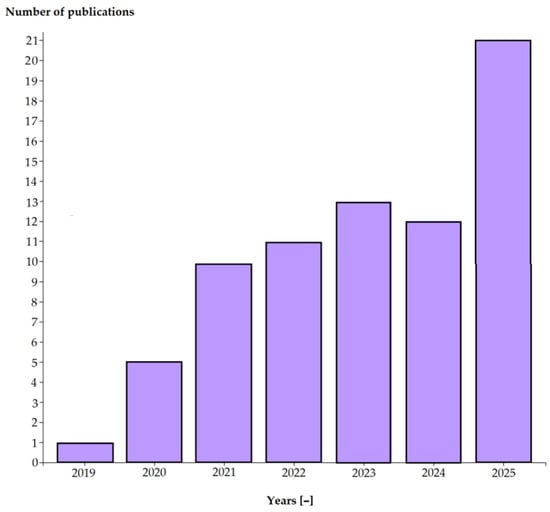

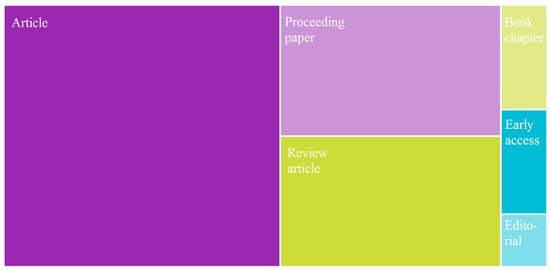

In the next step, the set of publications selected above was refined by manually reselecting articles and removing irrelevant publications and duplicates in order to determine the final sample size. A summary of the results of the bibliographic analysis is presented in Table 2 and Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13. Seventy-six articles (published between 2016 and 2025) were reviewed, including five WoS highly cited papers [37,38,39,40,41].

Table 2.

Summary of results (all four data bases).

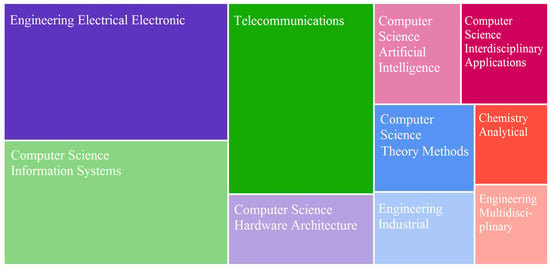

Figure 7.

Results by year.

Figure 8.

Results by type.

Figure 9.

Results by area.

Figure 10.

Results by affiliation.

Figure 11.

Results by country.

Figure 12.

Results by funding sources.

Figure 13.

Results by SDGs.

3.2. Key Useful Methods and Technologies

AI can be applied to a wide range of scientific problems, where specialized methods have already been proposed to address challenges related to complexity, uncertainty, and scale. In energy systems, AI methods such as reinforcement learning and digital twins optimize energy flows, renewable energy integration, and grid resilience. In medicine, AI supports diagnostic imaging, genomics, and rehabilitation, while methods such as deep learning and tensor decomposition increase precision and personalization. In agriculture, machine learning models and computer vision systems support smart irrigation, yield forecasting, and pest detection, improving sustainability and efficiency. In climatology, AI supports extreme weather forecasting, carbon cycle modeling, and climate impact assessment by learning from massive spatiotemporal datasets. In materials science, generative models accelerate the discovery of new compounds and optimize design for energy storage, photovoltaics, and advanced electronics. The construction and manufacturing industries are benefiting from AI-based predictive maintenance, robotics, and digitalization strategies to reduce waste and increase efficiency. In transportation and logistics, AI-based optimization methods are improving route planning, fleet management, and emissions reduction. Beyond its applied fields, AI is also contributing to theoretical scientific topics, such as optimization under uncertainty, explainable decision-making, and ethical modeling in critical infrastructure. These applications demonstrate that AI is not only a tool for practical problem-solving but also a driving force for new scientific theories and methodologies, shaping the conceptualization and implementation of future research. Healthcare, Industry 4.0, transportation, and agriculture are generating massive amounts of data automatically and continuously, driving increasing computational and service demands from the edge to the cloud [42,43]. This processing requires adaptive resource management mechanisms to offload decision-making and enable efficient scheduling. This poses a significant challenge due to the use of heterogeneous resources, transaction load, edge node detection, and service quality parameters [44,45]. Artificial intelligence addresses these challenges by categorising them into: computing resource provisioning, task offloading, resource scheduling, service deployment, and load balancing [46]. Notable emerging research avenues include serverless computing, 5G, the Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT), blockchain, digital twins, quantum computing, and software-defined networking (SDN). When combined with current Fog and Edge computing solutions, these technologies have the potential to significantly enhance business analytics and data processing in IoT-driven applications [37]. The Internet of Vehicles (IoV) utilizes vehicle and roadside unit (RSU) resources to perform various applications and tasks. Challenges include the growing number of vehicles and traffic asymmetry. Therefore, network operators must develop intelligent offloading strategies to improve network efficiency and provide users with high-quality services in the absence of global information, time variations, and long-term energy constraints. AI and ML can significantly enhance IoV intelligence and performance. Therefore, an integer nonlinear programming (MINLP) problem was formulated to minimize the overall network latency, and an internet-based multi-decision algorithm (OMEN) was formulated using the Lyapunov optimization method to solve the formulated problem, proving that OMEN achieves near-optimal performance [38]. Current 4G and 5G networks may not be able to meet the rapidly growing traffic demand, hence the research on 6G networks. An intelligent architecture based on artificial intelligence has been proposed for 6G networks, enabling knowledge discovery, intelligent resource management, automatic network regulation and intelligent service provision. This architecture consists of four layers: an intelligent sensory layer, a data exploration layer and an analytical layer, an intelligent control layer, and an intelligent application layer. AI in 6G networks enables efficient and effective network performance optimization. This also applies to mobile edge computing using artificial intelligence, intelligent mobility and switching management, and intelligent spectrum management [39]. The convergence of IoT and cloud computing offers many opportunities, but also faces certain limitations, such as bandwidth, latency and connectivity. This has led to the emergence of Edge and Fog Computing (FC), where computing and storage resources are located not only in the cloud, but also at the edge of the network, close to the data source. This enables the distribution of intelligence and computation, including AI, ML and big data analytics, to achieve an optimal solution while meeting specific constraints, such as the tradeoff between latency and energy consumption [40]. Blockchain-enabled IoV applications offer features such as decentralization, security, transparency, immutability, and automation [41]. Data Analysis of AI and Edge Interfaces in the environment IoT provides a strong support for the circular economy and more sustainable life, production, services, and entertainment, enabling the digitization of many operations and processes within smart environments. This applies to many areas, such as water distribution, predictive maintenance, and smart manufacturing, but to a lesser extent to the sustainability of the IoT sector itself, which still has a significant carbon footprint, uses significant amounts of energy in production, operation, and recycling processes, and requires rare earth elements. The Green IoT (G-IoT) paradigm offers a solution, but it requires reducing the role of edge AI, which requires additional energy consumption. As part of Industry 5.0, it proposes improving operator safety and operational tracking through the use of a mist computing architecture composed of AI-enabled IoT nodes. This reduces energy consumption and carbon footprint. This provides guidance to help future developers address the sustainability challenges posed by the next generation of G-IoT edge-AI systems [47].

Most current IoT applications in the energy sector are implemented within cloud-based systems. This solution allows for easier centralization of data storage, processing/imaging, and remote monitoring, but it also poses certain limitations. The cloud is a common point of failure. This is because security vulnerabilities, attacks, or even maintenance tasks can degrade its functionality or even block it, impacting the entire system [48]. The growing number of connected IoT devices, and consequently the many times greater number of expected messages, can overload the cloud and the entire system, requiring scaling and response to overloads [49]. To counteract this, new architectures based on edge computing have been proposed, in which some tasks can be performed by devices located at the edge of the IoT network (close to the final IoT nodes). Variations of the edge computing paradigm includefog computing, which utilizes low-power devices at the edge of the network, and cloudlets from high-end computers performing tasks requiring processing at the edge of the network [50,51,52,53].

One promising new approach to improving energy efficiency using AI is the development of a multi-agent reinforcement learning (MARL) system for decentralized control of hybrid AC/DC microgrids [54]. Each agent, representing a subsystem such as a renewable energy generator, energy storage, or load, would learn adaptive strategies to balance local energy consumption, coordinating them toward common optimization goals [55,56]. To avoid inefficiencies resulting from overtraining, a hierarchical coordination layer could guide agents toward global goals, such as minimizing carbon emissions or peak demand [57,58]. A second innovation is the integration of federated learning with power system optimization, allowing utilities from different regions to jointly train AI models without sharing raw data, improving forecasting accuracy while maintaining privacy [59,60,61]. This is complemented by graph neural networks (GNNs) for modeling the nonlinear network topology of AC/DC systems, capturing spatiotemporal dependencies more effectively than traditional methods [62,63]. To ensure real-time adaptation, a hybrid digital twin powered by AI could continuously simulate the grid and update optimization strategies based on live sensor data. To improve computational efficiency, an energy-aware AI training protocol would dynamically adjust model complexity, using lightweight models for real-time tasks and more advanced models for offline planning [64]. Furthermore, implementing explainable AI (XAI) would allow operators to understand optimization decisions, providing confidence in automated control strategies [65,66,67,68]. These methods could be combined into a unified platform, where AI not only improves energy efficiency but also ensures scalability, transparency, and interoperability across regions. The proposal emphasizes the role of AI as a technical optimizer and sustainability driver, aligning energy systems with efficiency and climate goals.

On the other hand, real-time IoT systems cannot always rely on cloud computing due to latency, which prevents the entire system from responding quickly. Edge AI improves this by deploying edge computing devices near IoT endpoints. This allows for reduced latency, while IoT node requests place less load on the cloud, freeing up cloud resources and avoiding potential communication bottlenecks in the system. However, the development of edge AI leads to increased energy consumption, which requires optimization for energy consumption [69,70].

3.3. Case Studies

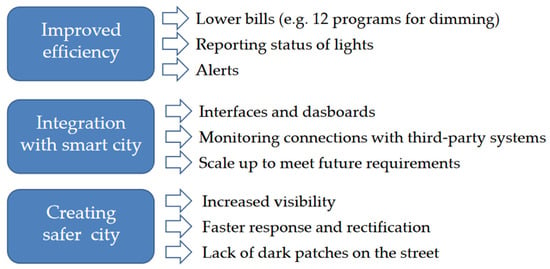

We have selected case studies that demonstrate how IoT, along with edge computing and AI-powered data analytics, has significantly improved energy efficiency in various smart environments (data centers, buildings, campuses, streets, power grids, and heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems). Google (Mountain View, CA, USA) used deep learning (DeepMind) models trained on historical telemetry data (temperatures, energy consumption, cooling controls) and integrated real-time predictions with control systems to adjust chiller/ventilation unit setpoints in the data center. The AI worked in a tight loop with the facility’s control systems (cloud/edge integration). Google reported approximately a 40% reduction in cooling energy consumption and an overall total energy reduction of approximately 15%. These savings resulted from predictive control and more efficient fan/chiller operation. This demonstrated that high-resolution sensor telemetry combined with ML predictions can detect non-intuitive control actions. However, this requires tight integration with operational controls and strict adherence to safety constraints [71]. Signify (Einhoven, The Netherlands)/Philips (Amsterdam, The Netherlands) smart street lighting implementations in Pune and Bratislava. These cities replaced old lamps with LED luminaires equipped with IoT controllers and managed by a city-wide platform (group dimming, scheduling, and fault monitoring). Edge/IoT nodes provide local dimming and status monitoring, while the city platform performs analytics for scheduling and fault detection. These case studies demonstrate significant savings: up to approximately 40% electricity savings through group dimming and LED conversion, as well as annual electricity savings, CO2 emissions reduction, and operational savings. These studies demonstrate that replacing the LED hardware and adding IoT controllers delivers immediate energy savings, while analytics enable further savings through adaptive dimming while streamlining maintenance (fewer service visits, Figure 14) [72].

Figure 14.

Signify/Philips smart street lighting benefits (based on [72]).

Schneider Electric’s (Rueil-Malmaison, France) EcoStruxure building management system combines IoT sensors/actuators, edge gateways, and cloud analytics to control HVAC, lighting, and building management systems. Implementations include a distributed building management system, predictive maintenance, and energy dashboards. Reported results from customer case studies include significant annual energy cost savings (e.g., reported by Massmart (Sandton, Republic of South Africa)) and operational benefits resulting from reduced downtime and improved control. While specific project numbers vary by location, Schneider documents reductions ranging from a few to tens of percent, depending on the scope of the modernization. This demonstrates that the platform approach: standardized IoT endpoints and edge computing for local resiliency, along with cloud analytics for trend analysis, scales well across portfolios and enables portfolio-level optimization (Figure 15) [73].

Figure 15.

Benefits reported by Massmart (based on [73]).

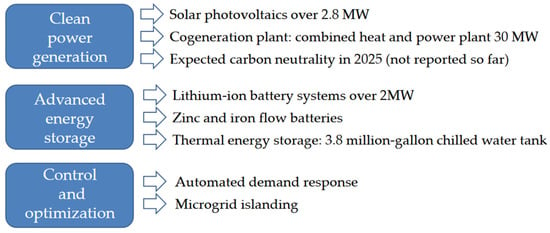

UC San Diego (La Jolla, CA, USA) operates a large campus microgrid (generation, storage, cogeneration, building loads) used as a living laboratory. Real-time telemetry, local control, and analytics are used for balancing, peak demand shaving, and renewable energy integration. Researchers/partners are testing algorithms for demand response, storage scheduling, and energy forecasting. The microgrid provides resilience and enables active generation/load optimization, improving overall system efficiency and reducing grid purchases during peak periods. The platform has validated studies demonstrating improved economics and emissions when analytics coordinates, among other things, peak energy demand on campus (approximately 55 MW). This demonstrates that complex, distributed energy resources benefit from rapid local control (edge) and coordinated optimization (analytics/cloud). Such on-campus microgrids provide a robust testing ground for algorithms before industrial-scale implementation (Figure 16) [74].

Figure 16.

Features of UC San Diego campus (based on [74]).

Utilities (Enel (Rome, Italy) and other grid operators) are deploying IoT sensors, edge analytics in substations, and centralized analytics to improve load forecasting, fault detection, and distribution automation. Edge nodes reduce latency in protection actions and pre-filter telemetry data for cloud-based analytics. Reported benefits include improved loss detection, better load balancing, fewer power outages, and more efficient resource utilization. All of this translates into reduced energy losses and improved system performance. Case studies and white papers demonstrate improved operational metrics and the integration of renewable energy sources. This demonstrates that edge computing reduces communication bottlenecks and enables local, time-sensitive decisions (e.g., islanding, protection), while cloud-based analytics manage fleet planning and optimization [75]. Edge AI vendors for HVAC and commercial HVAC systems (industry vendors/startups) are deploying small edge AI devices or models embedded in building controllers to detect anomalies, forecast short-term load, optimize setpoints, and perform predictive maintenance. They often do this by leveraging local data streams for low-latency decision-making. AutoEdge (Houston, TX, USA) describes faster model training, improved forecasting accuracy, and deployment at the edge for real-time control. Reported results include improved forecasting accuracy, faster model retraining (speed of deployment), and measurable reductions in HVAC system energy consumption. Percentage reductions vary by location, with many companies reporting double-digit savings when combined with modernization and good control. This demonstrates that deploying intelligence at the edge reduces cloud dependency and latency, enabling real-time control loops that significantly reduce HVAC system energy consumption. This is particularly true for buildings with varying occupancy or complex thermal dynamics [76].

Common findings from various case studies demonstrate what consistently works:

- Combining measures such as hardware upgrades (LEDs, efficient chillers) with IoT telemetry and analytics yields the greatest benefits;

- A hybrid approach, combining edge and cloud, provides latency-sensitive inference and filtering at the edge, mitigated by advanced analytics and portfolio-level optimization in the cloud;

- Telemetry quality is important, as data from higher-frequency and higher-accuracy sensors directly improves model performance and control security;

- The most frequently measured and compared metrics are energy consumption, peak energy demand, and costs with before-and-after benchmarking;

- The most frequently cited non-energy benefits that can be important for ROI: predictive maintenance, fewer service calls, emission reduction, and improved user comfort.

Typical observed challenges and precautions include:

- Data quality and integration, as legacy hardware and inconsistent protocols make integration costly;

- Security and control management, as automated control must incorporate fail-safes and human intervention in the process for edge cases;

- Measured versus modeled savings, as many vendors claim modeled savings, not measured savings, and these must always be verified through measured results over a reasonable timeframe.

The above experiences may change over time as improvements and new solutions are introduced to the market [77,78] such as ambient backscatter communication [79], Integrated Sensing and Communication [80], Near-field IoT [81], and RIS-assisted IoT [82].

Real-world project images are often lacking, as much research on smart environments and energy efficiency relies on simulated, pilot, or laboratory implementations rather than fully implemented real-world systems. Concerns about data confidentiality and security also prevent organizations from publicly sharing images of infrastructure, sensors, or control systems, especially in critical energy environments. Furthermore, research often focuses on algorithm performance and analytical models, reducing the emphasis on visual documentation of implementations. The lack of interviews with key stakeholders can be attributed to limited access to industry partners, time constraints, and ethical requirements for approval of human subjects. As a result, researchers often validate their findings using quantitative datasets and benchmarks rather than seeking qualitative validation from practitioners.

3.4. Improvement Roadmap

As a result of review we added five concise proposals for new methods to improve energy efficiency with AI and edge computing in smart environments:

- Edge–Cloud Collaborative Reinforcement Learning can dynamically shift computation between the edge and cloud to balance latency, energy cost, and model accuracy;

- Energy-Aware Federated Learning with adaptive model compression can reduce communication overhead while maintaining predictive performance in distributed smart environments;

- Hybrid Physics-Informed Neural Networks can integrate domain knowledge with AI models to improve renewable energy forecasting accuracy while reducing training complexity;

- Multi-Agent Energy Negotiation Systems using game-theoretic AI can coordinate smart devices, buildings, and vehicles to optimize collective energy consumption;

- Self-Healing Edge AI Frameworks with anomaly detection can autonomously identify and reconfigure faulty nodes, reducing energy loss from inefficiencies and failures (Table 3).

Table 3. Roadmap expanding the five proposed methods into problem–solution–impact format.

Table 3. Roadmap expanding the five proposed methods into problem–solution–impact format.

Concept of research development methodology is shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Summary of the ultimate methodology of research development.

The concepts of red artificial intelligence (Red AI) and green artificial intelligence (Green AI) distinguish two main approaches to artificial intelligence. Red AI is based on large models and data sets, and its performance is evaluated based on the accuracy achieved through the use of high computing power. Linear performance improvement requires an exponentially larger model, as well as more training data and more tuning experiments, so small performance improvements come at the cost of increased computational costs. Green AI focuses on improving performance without increasing computational costs, and even reducing them. In Green AI, performance is the priority in the evaluation process, not accuracy. Performance is also evaluated based on carbon footprint, energy consumption, real-time latency, and number of parameters [83,84].

AI-based predictive models forecast energy demand and equipment performance, reducing costs and preventing failures, which is economically beneficial for both suppliers and consumers [85]. Techniques such as reinforcement learning optimize heating, cooling, and lighting systems in real time, ensuring resource efficiency while reducing environmental impact, in line with sustainable development goals [86]. AI models identify unusual energy consumption patterns that may indicate waste, fraud, or technical faults, protecting consumers economically and ensuring fair access to energy [87]. Federated Learning enables AI models to be trained on decentralized edge devices without sharing raw data, addressing legal and ethical privacy concerns [88]. Edge AI Inference causes running lightweight AI models directly on edge devices to provide real-time decision-making, supporting societal needs for the security, reliability, and resilience of energy systems [89]. Robust cryptographic methods protect sensitive energy data while meeting legal and ethical requirements for user privacy. XAI gives transparency in AI decisions and enhances trust and accountability, which arecrucial from both a legal and societal perspective in smart environments [90]. AI-based demand response modifies or reduces energy consumption during peak hours, generating economic savings while contributing to overall grid stability [91]. Digital twins (virtual replicas of energy systems) enable simulation and optimization without disrupting real-world operations, reducing risk and supporting ethical testing practices [92]. Standards and protocols ensure efficient communication between different devices and systems, fostering legal transparency and fair economic competition. Distributed AI agents collaborate to manage energy resources in smart environments, ensuring their efficient use while respecting societal needs for equity [93]. Techniques that distribute computing tasks across edge devices minimize energy waste and infrastructure load, improving both efficiency and economic outcomes [94]. Secure and transparent transaction systems enable peer-to-peer energy sharing, fostering social equity and resolving legal issues related to ownership. AI-powered analytics assess the long-term sustainability impact of energy systems, ensuring ethical responsibility and compliance with environmental regulations [95]. Building legal and regulatory constraints into AI models ensures energy optimization is compliant with evolving regulations, aligning economic efficiency with social and ethical requirements [96].

AI-based data analytics combined with edge computing enables instant processing of energy data at the source, reducing latency and improving responsiveness in smart environments. AI models analyze energy consumption patterns to optimize heating, cooling, and lighting systems, ensuring that resources are used only when needed [97]. By processing data locally, edge computing minimizes the need to transmit massive amounts of raw data to centralized servers, reducing energy consumption in communication networks [98]. AI-based predictive analytics forecast fluctuating demand, enabling proactive adjustments that effectively balance energy supply and consumption. Edge computing supports decentralized energy systems, enabling smart grids to efficiently manage renewable energy sources like solar and wind in real time [99]. AI algorithms detect anomalies in device operation, enabling predictive maintenance that prevents energy waste and extends system life. Smart environments dynamically adapt to user behavior, adjusting energy systems based on occupancy, comfort preferences, and activity in real time [100]. Edge computing enables distributed energy management across buildings, cities, or industries without overloading centralized infrastructure. Improving energy efficiency through AI and edge computing leads to lower carbon emissions, contributing to sustainable development goals in smart environments [101]. Local data processing at the edge of the network enhances privacy while reducing the security risks associated with centralized energy management systems.

Traditionally, energy data from smart environments was collected and transmitted to centralized cloud servers for analysis, often resulting in latency and high bandwidth utilization. In contrast, edge computing processes data locally, at or near the source (e.g., in sensors, gateways), reducing latency and enabling faster energy efficiency decisions. Centralized systems struggled to scale with the massive increase in the number of IoT devices, leading to bottlenecks in the transmission and processing of energy data [102]. Edge computing distributes computation across multiple nodes, enabling more flexible and scalable energy management in larger smart environments. Traditional cloud approaches often consumed additional energy for data transmission and storage, while edge computing reduced energy consumption by minimizing unnecessary data transfers. Previous models concentrated sensitive energy data on cloud servers, making them more susceptible to breaches. Edge computing improves privacy by processing sensitive energy consumption data locally, limiting exposure to external servers [103]. Centralized systems are more susceptible to single points of failure, while edge systems offer greater resilience through distributed architecture. Cloud-based solutions often introduce latency that hindered real-time energy optimization, while edge computing enables immediate response to fluctuations in demand [104]. Unlike previous centralized approaches, AI-based edge computing can dynamically manage decentralized renewable energy sources such as solar panels and microgrids, improving sustainability and efficiency in smart environments [105].

3.5. Gaps Observed in Regulations, Research and Publications

The lack of a harmonized regulatory framework governing the implementation of AI-based data analytics and edge computing to improve energy efficiency leads to fragmented practices across regions. Clear rules regarding data ownership, privacy, and data sharing in smart environments remain underdeveloped, creating uncertainty for stakeholders [106]. Current research often overlooks the need for standardized protocols, hindering the integration of AI, IoT devices, and edge computing systems. Few publications address the ethical implications of AI-based energy decisions, including algorithmic bias, explainability, and fairness [107]. Research focuses on short-term efficiency gains, with few analyses assessing long-term economic, environmental, and social consequences. There is no widely accepted methodology for measuring and comparing the performance of energy efficiency systems based on AI and edge computing [108]. Publications often underestimate the cybersecurity risks associated with distributed energy systems, particularly security vulnerabilities at the edge. Many studies remain in the pilot or simulation phase, and research on scaling AI edge solutions to larger, real-world smart environments is insufficient [109]. Research and policy discussions focus primarily on developed countries, neglecting the unique energy and infrastructure challenges in developing economies. Publications often discuss AI, edge computing, or energy efficiency separately, with limited interdisciplinary integration of technical, regulatory, and societal perspectives [110].

One of the main challenges is the lack of clear, harmonized regulations for AI and edge computing in energy efficiency, which slows down implementation and investment. Edge devices process sensitive energy and user data, but regulations and research often lack a robust framework to ensure privacy and cybersecurity. The lack of standardized communication protocols between IoT devices and platforms hinders integration, a recurring challenge noted in both policy and academic publications. AI models used for energy optimization often operate as “black boxes,” and regulations do not yet provide an explanation for them, raising concerns about trust and accountability [111]. Many studies remain in the theoretical or pilot phase, and few publications demonstrate the real-world results of large-scale implementations [112]. The lack of a universal metric or evaluation framework for comparing the performance gains of AI-edge solutions makes it difficult to verify or regulate performance claims. Although decentralized edge computing increases responsiveness, it increases vulnerability to cyberattacks, publications often treat this as a secondary issue rather than a primary challenge. Research rarely addresses the economic and technical barriers to scaling AI-edge energy solutions from smart buildings to the urban or industrial level [113]. Current publications focus primarily on developed economies, with limited analysis of the adaptability of these technologies to regions with low infrastructure or energy challenges [114]. Academic and industrial research often remains isolated, addressing AI, edge computing, or energy efficiency separately, without comprehensive, interdisciplinary approaches to regulation and implementation [115].

A central problem in AI-based energy management research remains that most studies present only bibliometric data rather than specific performance metrics. Presented results are often limited to publication counts, citation trends, or topical clusters, without identifying measurable data such as kilowatt-hour (kWh) savings. As a result, claims about potential efficiency gains or cost savings are not supported by numerical values. Many articles emphasize measurable energy reductions, but the lack of numerical results causes a lack of evaluative synthesis and prevents them demonstrating concrete impacts in case studies or industrial applications. Without these metrics, it is also impossible to compare the impact of different AI methods or energy systems. If claims in the literature remain unsupported by synthesized empirical evidence, this creates a credibility gap between promise and evidence. Until researchers conduct systematic, outcome-based evaluations, conclusions about AI effectiveness remain exaggerated. A more prudent approach would be to limit claims to fit the available evidence rather than projecting excessive benefits. The entire field needs to move from bibliometric analyses to evidence-based synthesis to determine the real contribution of AI to energy efficiency and sustainability.

We also analysed several examples of projects in the logistics, construction and agriculture sectors illustrating the impact of innovative AI methods on energy efficiency in the context of energy economics and sustainable development, including solutions such as CEVA Logistics (Bydgoszcz, Poland)/BeeBryte (Lyon, France), GE Vernova (Cambridge, MA, USA)—AI/ML for wind turbine logistics costs, Grow Autonomous Greenhouse Control (iGrow), Smart Droplets Project (part of the European Green Deal), AgMonitor Platform (for water and energy efficiency in agriculture), Netafim (Tel Aviv, Israel) and Smart AgriHub (EU Project, 300 digital innovation hubs, 3200 active users) [116].

New AI methods have brought measurable energy savings in many sectors. Logistics applications, such as AI-based control of HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning) systems in cold stores, have reduced annual electricity consumption by up to 30%. In industrial energy systems, AI-assisted predictive maintenance and process optimisation have shown a 10–20% reduction in operational energy consumption, translating into lower costs and carbon emissions. In agriculture, AI-optimised irrigation systems such as Netafim have reduced water consumption by 50% while also reducing the energy required for pumping and distribution. Greenhouse automation projects such as i-Grow (Chodzież, Poland) have seen a 92.7% increase in net profit and a 10.15% increase in yield, achieved in part through improved energy and input efficiency. AI-based predictive building control in institutional facilities reduced natural gas consumption by 23.9% and winter heating demand by 6.3%. In construction and building operations, AI-based digital twins and intelligent control systems can reduce material consumption by up to 40% and achieve energy savings of 20–30% compared to conventional methods. Research on crop cultivation has shown that AI can reduce the energy intensity of lettuce production by approximately 32.42%/kg, which represents a significant improvement in the sustainability of the food system. In wind energy logistics, AI/ML tools have the potential to reduce installation and transport costs by 10% globally, indirectly reducing emissions associated with the use and transport of heavy equipment. AI-based port and supply chain monitoring, such as Awake.AI (https://www.awake.ai, accessed on 23 December 2025), provides tools for quantifying and reducing CO2 emissions, helping cities achieve their climate goals. Results to date show that properly tailored AI can contribute not only to gradual but even double-digit improvements in energy savings and emissions reductions, highlighting its role as a key driver of energy efficiency, industrial transformation and sustainable development [117].

4. Discussion

Most studies relied on simulation environments or theoretical models, which, while valuable, cannot fully capture the complexity of operating energy systems. As a result, reported energy efficiency improvements often reflect expected results rather than verified performance based on real-world test data. Without field trials or pilot implementations, it is unclear whether the algorithms will maintain their effectiveness under conditions of data noise, system interference, or hardware limitations. This gap reduces the practical validity of the findings, as stakeholders require empirical validation before large-scale implementation. The lack of real-world testing also limits insight into scalability, particularly in diverse AC/DC systems with varying load and renewable energy penetration. Furthermore, the studies did not provide sufficient analysis of unexpected risks or failures that may arise during real-time implementations. Expected results are often optimistic, assuming excellent data quality and ideal infrastructure, which may not hold true in practical scenarios. This creates a gap between the theoretical potential of AI-based optimization and its proven impact in practice. Overall, the lack of validation through real-world testing highlights a serious limitation of the current literature, emphasizing the need for pilot studies, longitudinal data collection, and field experiments to bridge the gap between simulations and reality.

The integrated IoT, edge computing, and AI framework in this paper posits that real-time data analytics can optimize energy consumption much more dynamically than traditional centralized cloud systems by processing data close to the source, reducing communication overhead and decision latency. This is also emphasized by broader research on IoT and edge computing, which demonstrates the benefits of real-time processing for smart environments. This paper presents a multi-layered analytical perspective showing how data flows from IoT sensors through edge nodes to AI analytics can systematically support energy efficiency. This approach builds on, but goes beyond, simpler methods used in studies that exclusively consider IoT or AI in energy management. Unlike previous reviews that largely categorize AI methods for optimizing building energy consumption (e.g., reinforcement learning, supervised learning) without architectural integration, our review explicitly integrates these learning strategies with edge computing data pipelines, offering a unified theoretical model for energy analytics. Theoretical innovations in this work include context-aware energy prediction and control mechanisms that leverage continuous, low-latency IoT data streams, in contrast to conventional approaches that assume periodic or batch processing is sufficient. Emphasizing the importance of distributed analytics at the edge, the study advances the idea that energy efficiency is not simply a result but an emergent property of decentralized computation and learning, a view supported by the IoT at the edge literature focusing on energy-efficient distributed analytics. This paper also theorizes that AI-assisted edge systems can adaptively manage resources, representing a step forward from general systematic reviews that describe the impact of AI or IoT on energy but do not formalize adaptive control loops. Compared to traditional IoT energy management research, which emphasizes sensor data collection and monitoring, this paper integrates predictive analytics and automated decision-making frameworks, emphasizing AI not merely as an analytical adjunct but as a key driver of energy savings. This work significantly positions edge computing as a bridge between raw IoT data and intelligent decision-making, improving the efficiency of both communication and inference. This theoretical approach builds on general edge AI taxonomy research but focuses on energy outcomes. Theoretical comparisons with cloud models show that local data processing using AI predictions can significantly reduce energy consumption for data transmission, a benefit referenced in many related reviews but not modeled in a combined analytical framework. By treating energy efficiency as both a system goal and a design constraint, the study’s theoretical exposition encourages future research to consider co-optimization of sensors, computation, and AI inference: an integrated goal less explicit in prior, isolated reviews of IoT or AI in the energy context.

Already today, integrating IoT sensors with data analytics provides detailed, real-time insights into energy flows and occupant behavior, a fundamental element of any energy efficiency intervention. Edge computing complements IoT by pre-processing and aggregating data close to the source, reducing latency and communication overhead, allowing control actions (e.g., local heating, ventilation, and air conditioning adjustments) to be executed faster and at lower grid energy costs. AI (specifically, machine learning models for forecasting and reinforcement learning for control) transforms sensor and edge data into predictive scheduling and adaptive setpoints that reduce energy waste while maintaining comfort. A combined IoT, edge, and AI stack provides demand-side agility through short-term load forecasting and automatic demand response, enabling buildings and microgrids to shift or reduce load in the event of limited supply or high prices. Data analytics also drives predictive and condition-based maintenance (for motors, chillers, and transformers), which reduces energy waste caused by degraded equipment and extends asset life by identifying anomalies before failures occur. Architectures that balance edge inference and cloud learning protect privacy and reduce communication energy consumption: lightweight models run at the edge of the network, providing real-time control, while cloud resources reprogram models on aggregated datasets for continuous improvement. The net effect on system performance is multiplicative, not additive: sensor granularity, lower-latency edge control, and smarter AI strategies combine to deliver greater savings than any single technology acting alone. Implementation challenges that can limit the benefits achieved include data quality and interoperability, model generalization across locations, cybersecurity threats, and the embodied energy of additional devices, all of which must be addressed through standards, secure design, and lifecycle assessment. Evidence from pilot studies and implementations in smart buildings, industrial facilities, and distributed energy systems indicates typical electricity savings, improved peak load reduction, and faster fault detection, although absolute results vary depending on context and baseline performance. IoT-based data analytics, edge computing, and AI offer a scalable path to significant energy efficiency improvements in smart environments—provided implementation adheres to best practices for data management, model validation, and balancing the responsibilities of edge and cloud computing. The growing emphasis on sustainability may lead to a divergence of technologies into Green AI and Red AI, but the technology race for AI leadership between the US, China, and other players in the so-called home AI market is just beginning and will likely accelerate after 2030.

4.1. Key Economic Implications

Broader adoption of AI-based data analytics and edge computing reduces energy waste, leading to significant cost savings for homes, businesses, and industry [117,118]. Optimized energy distribution reduces peak demand, reducing the need for costly investments in new energy infrastructure. Companies implementing smart energy systems benefit from longer equipment lifespans and more efficient resource utilization, resulting in a higher Return on Investment (ROI). Implementation of solutions increases demand for specialists in AI, edge computing, cybersecurity, and energy management, creating new job opportunities. High upfront costs of implementing AI-edge systems can disadvantage smaller companies and exacerbate economic inequality. Smarter integration of renewable energy sources through AI-edge optimization strengthens the deployment of clean energy, stimulating investment in green technologies. Countries and companies that implement these technologies can achieve energy-efficient production, lowering costs and gaining a competitive advantage in global markets. Energy savings and real-time data analysis improve logistics and production efficiency, indirectly reducing operational costs in supply chains. Vulnerabilities in decentralized edge networks pose financial risks in the event of disruptions to energy systems caused by cyberattacks. By reducing carbon emissions and energy consumption, AI-edge solutions contribute to sustainable economic growth and resilience [119].

4.2. Key Societal Implications

Smarter energy management in buildings and cities increases the comfort, safety, and convenience of everyday life [120,121]. Artificial intelligence-based systems (AI-edge) can support decentralized energy models such as microgrids, improving access to reliable power in remote or underserved communities [122]. Widespread energy efficiency improvements reduce carbon emissions, contributing to cleaner air and healthier living conditions. Broader implementation requires new skills in AI, data analytics, and edge computing, which is shifting priorities in education and training [123]. Automation of traditional energy management roles could limit some job opportunities, raising concerns about unemployment in specific sectors [124]. Communities or regions lacking the resources to implement smart energy solutions may face greater inequality compared to technologically advanced areas [125]. Real-time monitoring of energy systems using edge computing reduces the risk of power outages, fires, or equipment failures in urban environments [126]. Collecting and processing energy consumption data at the edge raises questions about personal privacy and surveillance in smart environments. Citizens can more actively participate in energy conservation by having transparent [127], AI-powered information about their consumption patterns. Broader implementation increases public awareness of energy efficiency, promoting greener behaviors and lifestyles [128,129].

4.3. Key Ethical and Legal Implications

The wider deployment of AI edge systems involves the collection of detailed energy consumption data, which increases the risk of misuse, surveillance, or unauthorized access [130]. Legal questions remain about who owns and controls energy consumption data—individuals, service providers, or governments [131]. AI models may inadvertently favor certain groups of users or energy consumption patterns, leading to unfair treatment and ethical dilemmas [132]. The “black box” nature of AI decision-making makes it difficult to explain or challenge energy management decisions, creating legal accountability issues [133]. Users may not be fully informed about how their energy data is processed, challenging the ethical principles of informed consent. Legal questions arise regarding liability in the event of a breach of edge energy systems, leading to financial losses or security threats [134]. Current energy and technology regulations often do not adequately cover AI edge applications, leaving legal gray areas. Smart environments often rely on hybrid cloud solutions, creating legal complications when processing data across jurisdictions with differing regulations. Without appropriate regulation, advanced AI edge solutions could be limited to affluent communities, exacerbating social inequalities. Ensuring the sustainable, equitable, and environmentally responsible deployment of these technologies requires a new legal and ethical framework that balances innovation with social well-being [135].

4.4. Limitations

Despite rapid development many limitations are observed within AI-based data analytics and edge computing on energy efficiency in smart environments. Training and running complex AI algorithms can itself consume significant energy, sometimes offsetting the performance benefits they are intended to provide [136]. Edge devices often have limited processing power, memory, and storage, limiting the complexity of AI models that can be deployed locally. Energy optimization relies on large volumes of high-quality data, but incomplete, noisy, or biased datasets reduce the accuracy of AI-based analyses [137,138]. While edge AI solutions are effective in small-scale pilots, many face difficulties scaling to larger intelligent environments, such as entire cities or industrial zones. While edge computing reduces latency, for multiple devices and layers, latency can still be a bottleneck in real-time energy management [139]. Existing infrastructure and legacy energy systems are often not fully compatible with AI-edge solutions, limiting their implementation in real-world environments [140]. Decentralized edge nodes are more difficult to secure, making them potential targets for cyberattacks that could compromise energy systems [141]. The lack of universal standards for communication, interoperability, and evaluation hinders widespread deployment and comparability of results. The high upfront costs of implementing AI and edge infrastructure can be prohibitive, especially for small businesses or developing regions [142]. There is still limited knowledge about how AI-edge energy systems operate in the long term, including maintenance needs, resilience, and overall stability [143,144].

The perception that in many studies of smart environments, the reported impact of AI on energy efficiency remains largely anecdotal, and claims of “significant savings” are not supported by standardized, quantitative metrics, stems from the fact that study results are often based on short-term pilots or simulations, making it difficult to distinguish actual efficiency gains from temporary behavioral changes or favorable test conditions. Heterogeneity in the underlying data, building types, climate, and control strategies further limits comparability and weakens the evidentiary strength of reported results. AI models are often evaluated based on their forecast accuracy rather than on verified reductions in energy consumption, peak demand, or carbon intensity. Furthermore, the energy costs of training, deploying, and maintaining AI models (especially in cloud architectures) are rarely included in efficiency assessments (the Green AI vs. Red AI dilemma). As a result, despite its great theoretical potential, the actual contribution of AI to energy efficiency in IoT- and edge-enabled smart environments is often insufficiently substantiated by specific, repeatable performance metrics and requires further replicable research.

4.5. Directions for Further Research

Future research should focus on creating energy-efficient, lightweight AI algorithms that can run efficiently on resource-constrained edge devices. There is a need for unified protocols and frameworks that enable seamless communication between AI systems [145], IoT devices, and edge computing platforms. Research should address policies for secure, ethical, and privacy-preserving energy data processing in smart environments. Further work is needed to scale edge AI solutions, from building-level pilots to city- or industrial-scale deployments, without compromising performance [146]. Future research should explore how AI edge computing can optimize decentralized renewable energy sources and microgrids in real time [147]. Research should prioritize the design of resilient edge architectures with built-in AI-based threat detection and mitigation mechanisms. Establishing standard performance metrics and testing frameworks would enable consistent evaluation of energy efficiency outcomes across studies [148]. Research should consider user behavior, comfort, and social acceptability when designing AI-based energy management systems. Stronger integration of computer science, energy engineering, social sciences, and policy research is essential to holistically address technological and societal challenges. Future research should assess the environmental, economic, and social impacts of AI-based energy solutions over their longer lifecycles [149].

Further research into AI-based methods for energy management should begin with pilot experiments in controlled microgrid environments to validate the algorithms’ performance under real-world conditions. These pilots should integrate different energy sources, such as solar, wind, storage, and flexible loads, to test the adaptability of AI models to fluctuations in supply and demand. Researchers should utilize digital twins alongside live systems, enabling real-time comparisons between simulated optimization results and actual performance [150]. Thorough validation requires collecting longitudinal datasets over months or years to capture seasonal variations, equipment aging, and the impact of user behavior. To ensure robustness, experiments should incorporate stress scenarios such as cyberattacks, demand spikes, or unexpected outages, testing how AI methods respond to disruptions. A multi-criteria evaluation model should be developed that measures not only energy efficiency but also carbon emissions reduction, cost savings, and system resilience [151]. Collaboration with utilities, industry, and policymakers is crucial to access operational infrastructure and adapt research to real-world constraints [152]. Further research should also focus on scalability, extending experiments from microgrids to larger, interconnected AC/DC networks [153]. Furthermore, benchmarking different AI approaches (e.g., reinforcement learning, federated learning, graph neural networks) would provide insight into strengths and weaknesses in different contexts [154]. Further research must strive for evidence-based validation, ensuring that the impact of AI on energy management is demonstrated through rigorous, repeatable experiments rather than theoretical predictions.

5. Conclusions

AI-powered edge solutions have the potential to transform energy systems into more efficient, sustainable, and human-centric ecosystems for Industry 4.0 and 5.0. AI-powered data analytics and edge computing are transforming energy efficiency in smart environments, enabling more effective real-time decision-making and adaptive optimization. These technologies reduce waste, increase sustainability, and lower operating costs while improving end-user comfort and safety. They also facilitate the seamless integration of renewable energy sources and decentralized grids, making energy systems more resilient and future-proof. Challenges remain related to data privacy, cybersecurity, regulatory gaps, and the digital gap, which can hinder equitable implementation. The economic and social benefits are significant but require careful management to avoid deepening inequalities. Ethical and legal frameworks must evolve alongside technological advances to ensure transparency, fairness, and accountability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app16010225/s1: partial PRISMA 2020 checklist.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; methodology, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; software, D.M.; validation, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; formal analysis, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; investigation, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; resources, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; data curation, D.M.; writing—original draft preparation, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; writing—review and editing, I.R., P.P., M.P., P.K., N.N. and D.M.; visualization, D.M.; supervision, I.R.; project administration, I.R.; funding acquisition, I.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work presented in this paper has been financed under a grant to maintain the research potential of Kazimierz Wielki University.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| DL | Deep learning |

| GenAI | Generative AI |