1. Introduction

With the recent advent of New Space Economy, laser ablation started to attract interest also as a possible innovative propulsion technique. This interest was raised mainly because of two emerging problems related to the vast exploitation of earth orbit: space debris mitigation [

1] and nanosatellites orbit correction [

2].

The former one is due to all the non-operating satellites, rocket stages, and other objects that are left orbiting around earth uncontrolled, in which motion may require years for them to re-enter into the atmosphere with their disintegration. All these objects represent a threat for future space missions, since they can lead to collisions with formation of a larger number of smaller debris. This phenomenon, predicted by Kessler [

3], may lead to the onset of a collisional cascade; therefore, the only way to reduce the number of space debris is by their active removal from earth orbit.

The second problem comes from the recent exploitation of smaller and smaller satellites, deployed in a large number to form constellations, allowing for an improvement in earth observation and communications [

4].

This led to a consistent reduction in the size and mass of satellites, that now have typical dimensions of tens of centimeters and masses of few kilograms, as it is typically seen in the case of CubeSats. Due to both their mass and small size, these satellites often cannot be equipped with their own on-board propulsion system and therefore it is not possible to control their orbit, reducing their operating times due to possible re-entry into the atmosphere because of residual drag.

A possible solution to both these problems requires a strategy to move objects in space, avoiding on-board propulsion.

During laser ablation, mass ejection occurs from the irradiated surface of a material. Due to the considerably high velocities of the ejected mass, because of momentum conservation, a mechanical impulse

is generated on the irradiated material, that can be therefore expressed as follows [

5,

6]:

where

is the ejected mass and

is the ejection velocity. Laser ablation therefore allows for generating thrust on an object from a distant position and avoiding any mechanical contact. Additionally, no specific systems are needed on board of the object to exploit such propulsion technique, making it a really attractive solution for control of small satellites.

While in the case of space debris there is no possibility to choose the target material to generate impulse, in the case of nanosatellite propulsion the target material can be optimized in order to achieve better propulsion performance [

7], which is usually expressed by the laser impulse coupling coefficient,

, and specific impulse,

, defined as follows:

where

E is the laser pulse energy and

g is the gravity acceleration on earth.

Several works report tests on different target materials aimed at increasing either

or

. As a general observation, polymers show higher

values, compared to metals, that on the other side generate a higher

. The strategies employed to increase

, typically in polymers like PVC [

7,

8], GAP [

9,

10,

11], POM [

12,

13,

14], include the addition of an absorber in the material, in order to increase its interaction with the laser. These absorbers are usually dyes, while carbon nanoparticles proved to be more energetically efficient. The inclusion of nanoparticles as laser absorber was also used in other kinds of materials, like metal oxide frameworks [

15], showing an improvement in the propulsion performances too.

Along with the optimization of the properties of the target material, impulse generation can also be enhanced through confined laser ablation. In this configuration, a layer transparent to laser radiation is positioned on the surface of the absorbing material, so that the laser pulse is absorbed at the interface, leading to the formation of a plasma layer in this region. The confined plasma in turn interacts with the laser radiation, leading to a strong pressure increase just under the confining layer, and resulting in some cases in the generation of shock waves both in the confining and absorbing materials, as described in [

16]. This pressure increase opens the interface and brings to the rupture and the ejection of the confining layer, generating a mechanical impulse on the irradiated material. The addition of a confinement layer therefore allows to considerably increase the pressure on the surface of the absorbing material, thus possibly resulting in the full ejection of the transparent layer, so that a much higher mechanical impulse is generated.

Despite being an efficient technique to enhance impulse generation, confined laser ablation also presents some drawbacks. In particular, since the impulse is generated by the ejection of the confinement layer, after a single laser shot only the absorbing material is left on the irradiated region; therefore, a new region must be irradiated to generate a new impulse. Moreover, the ejection of the confinement layer causes a large mass loss; therefore, this mechanism suffers from the problem of mass consumption. In other words, decreases. For this reason, the thin confinement layer becomes more attractive but the general aspects of impulse generation in this regime need to be better understood.

At present, experiments investigating impulse generation in confined ablation geometries have aluminum as the absorbing material, and consider confinement layers thicker than 100 μm [

17], more often in the mm scale [

18]. Additionally, the confinement layer is usually attached to the surface of the absorbing material by means of some adhesive [

17], or just kept in contact with the absorbing surface by some support [

16,

18]. These kinds of systems therefore introduce some variability in the experimental conditions, especially considering the interface between the confining and absorption materials, making difficult a fine comparison among them.

Another common feature of these kind of experiments is that they are conducted using high fluences, often around 100

[

16,

17,

18], which are not very convenient in laser ablation propulsion applications, due to the difficulty in reaching such high energy densities on far targets.

The recently reported self-confinement processes, in appropriately doped composite polymers [

19], open the way to limit the problem of mass consumption by using limited values of laser energy fluence, but in the present work we want to see if the use of transparent thin films can still overcome the two problems.

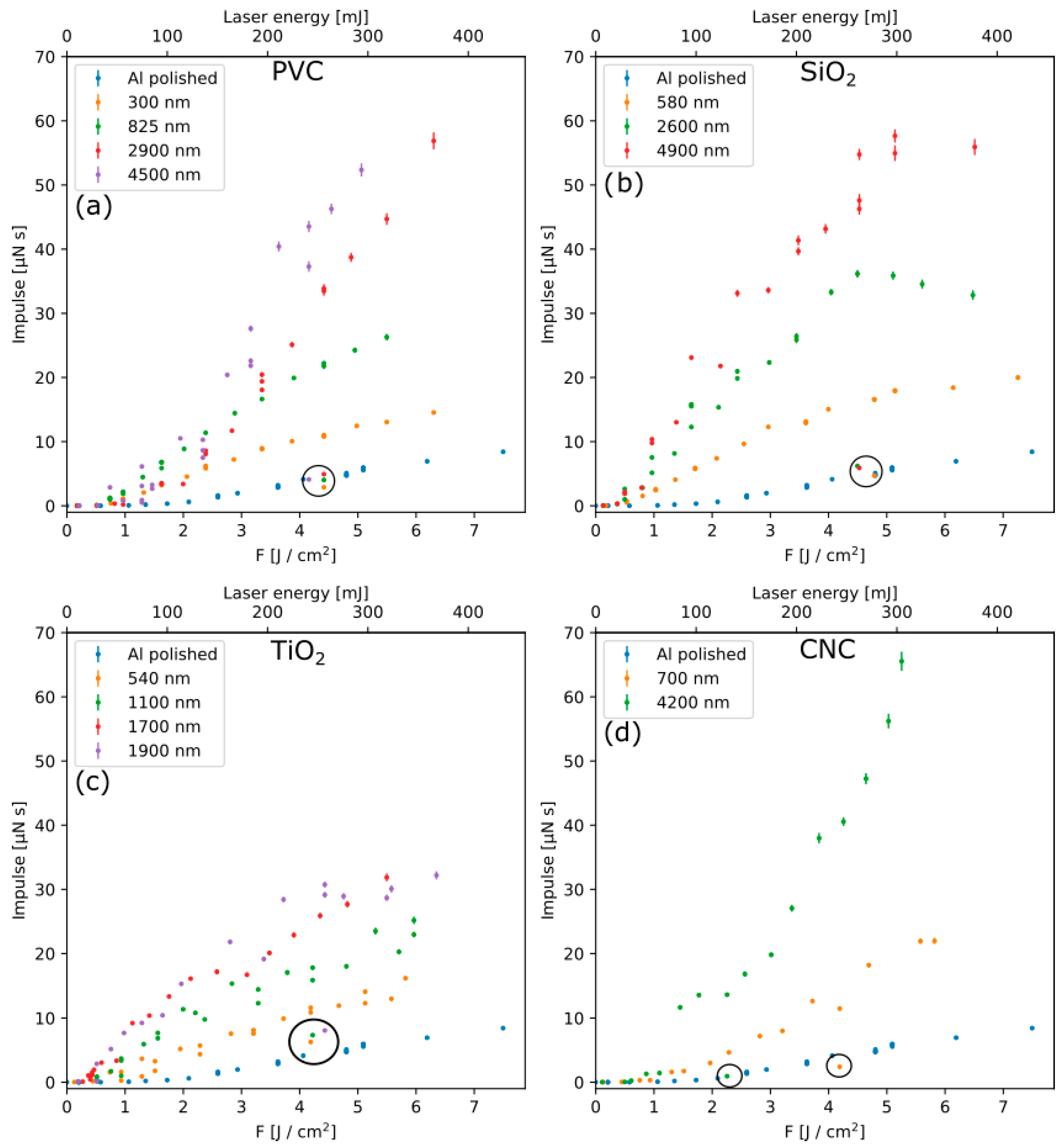

This work considers indeed thinner confinement layers of PVC, SiO2, TiO2 and cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs) with thickness ranging from 0.3 μm to 5 μm, deposited on aluminum, irradiated in a low laser fluence regime. By using such samples, it is possible to highlight how the thickness and the material of the confinement layer affect impulse generation. Using a common substrate and no external agents to keep the confinement layer stuck on the absorbing surface, a coherent comparison of the results is possible.

It is proved that even with confinement layers of a few hundreds of nm, a considerable impulse increase can be generated. Furthermore, because of the adopted geometries, it was possible to propose a phenomenological description of the obtained results.

These results provide a better understanding of impulse generation in confined ablation regime, under conditions that are expected to be closer to those encountered in applications, while also enabling future development of multilayer structures.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Aluminum (6082) was used as the absorbing material for all experiments. Aluminum square targets with size 26 × 26 × 1 mm were polished by using abrasive paste and cleaned with ethanol.

Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) (Sigma-Aldrich, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; powder, average Mw ∼43,000, average Mn ∼22,000) was deposited by spin coating. In order to control the thickness of the confining layer, the viscosity of PVC solution was changed by dissolving the polymer in cyclohexanone with concentrations 5 wt%, 10 wt%, 20 wt% and a rotation velocity of 3000 RPM for 120 s was used for all the concentrations. An additional sample was prepared by using 1000 RPM for 120 s and the 20 wt% solution to obtain a thicker film. After deposition, the samples were dried at 160 °C for 3 h to ensure a complete evaporation of cyclohexanone, as previously observed in [

7].

The SiO2 films have been prepared from the precursor NN120-20 (DurXtreme GmbH, Ulm, Germany) (20 wt% solution of perhydropolysilazane (PHPS) in 80 wt% di-n-butylether (DBE)). The deposition of the films is carried out by spin coating (Model P6700, Specialty Coating Systems, Indianapolis, IN, USA), with different RPM: 500, 1000 and 8000 RPM. The time is set to 90 s for all the samples. After the deposition, the SiO2 films were dried at room temperature overnight. The PHPS reacts with the moisture and oxygen present in the atmosphere releasing ammonia, thus crosslinking to obtain a structure closer to vitreous silica. Indeed, being the studied material a polymer-derived silica obtained at room temperature, the structure cannot be completely comparable with a fully polymerized silica glass obtained by melt quench. In the following, we will define this material as silica or SiO2 for simplicity, but we stress that the layer still contains some organic moieties and can be rather considered a hybrid network.

TiO2 deposition was performed by radio frequency (RF) sputtering of a TiO2 target in an argon atmosphere. The argon pressure during deposition was kept at mbar, RF power was 150 W, and the distance of the substrate from the TiO2 target was 5.5 cm while deposition times were 1 h, 2 h and 4 h.

CNCs were produced from cellulose pulp (SCA, Sundsvall, Sweden) by TEMPO mediated oxidation, according to the procedure of Saito [

20] modified as reported by Bettotti et al. [

21]. Briefly, water-swollen cellulose pulp is oxidized at alkaline pH by hypochlorite as primary oxidant and TEMPO and NaBr as catalysts, rinsed with deionized water and sonicated. This procedure removes the amorphous cellulose regions retaining the crystalline ones, and rod-shaped nanostructures with length and width approximately 150–250 nm and 3–5 nm, respectively, are obtained. Moreover, the oxidation introduces carboxylic groups at the C6 position of the cellobiose ring which bear a negative charge at neutral pH and confer colloidal stability. Sodium ions are present in the final CNC suspension as counter ions of the carboxylic groups. To obtain the films, the CNC suspensions were deposited uniformly at room temperature on solid square shaped Al substrates. Before deposition, Al substrates were washed using a mild detergent, rinsed several times, and soaked in deionized water for at least 48 h. The volume and concentration of the deposited CNC suspensions were properly adjusted to obtain variable thickness of the final films in the desired range.

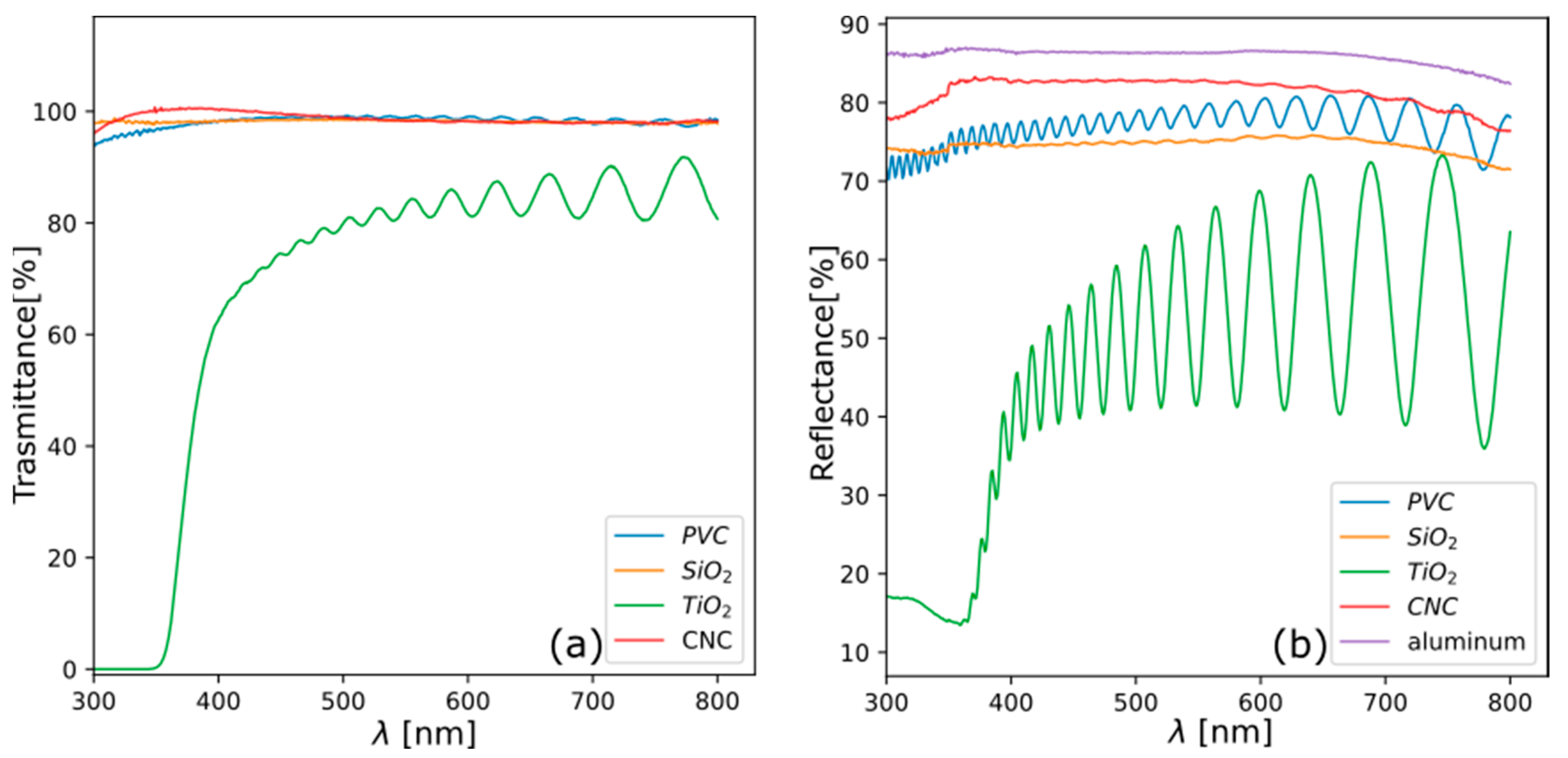

2.2. UV-Vis

UV-visible spectroscopy (Varian Cary 5000, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to measure the transmittance and reflectance of the studied confinement layers. Transmittance measurements are made by depositing the confinement layers on a glass substrate, transparent to the employed laser wavelength, in order to confirm that they are not absorbing the incoming laser pulse.

The measurement of total reflected radiation on the other hand was exploited to assess the thickness of the deposited confinement layers. Because of the interference among multiple reflections at the surface of the film and at the interface between the confining layer and aluminum, oscillations in the reflectance spectrum of these samples can be observed. This allows to estimate the thickness

t of the confinement layer by using the following relation [

22]:

where

is the wavenumber at which an extremum in the spectrum is observed and

is the wavelength,

is the refractive index of the film and

is the incidence angle of light, which was 3° in the case of the used spectrophotometer, on which an integrating sphere was mounted.

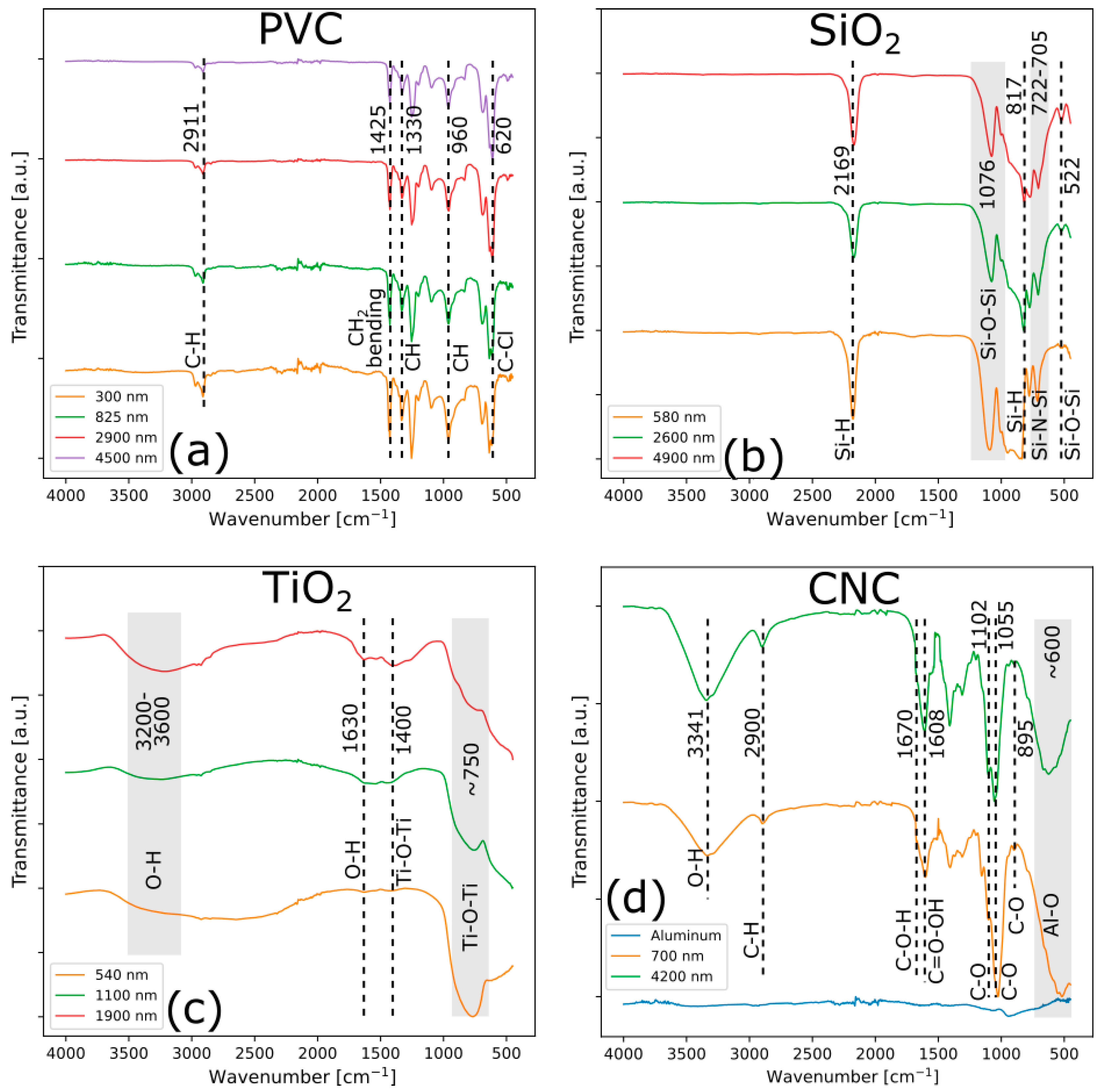

2.3. Materials Characterization

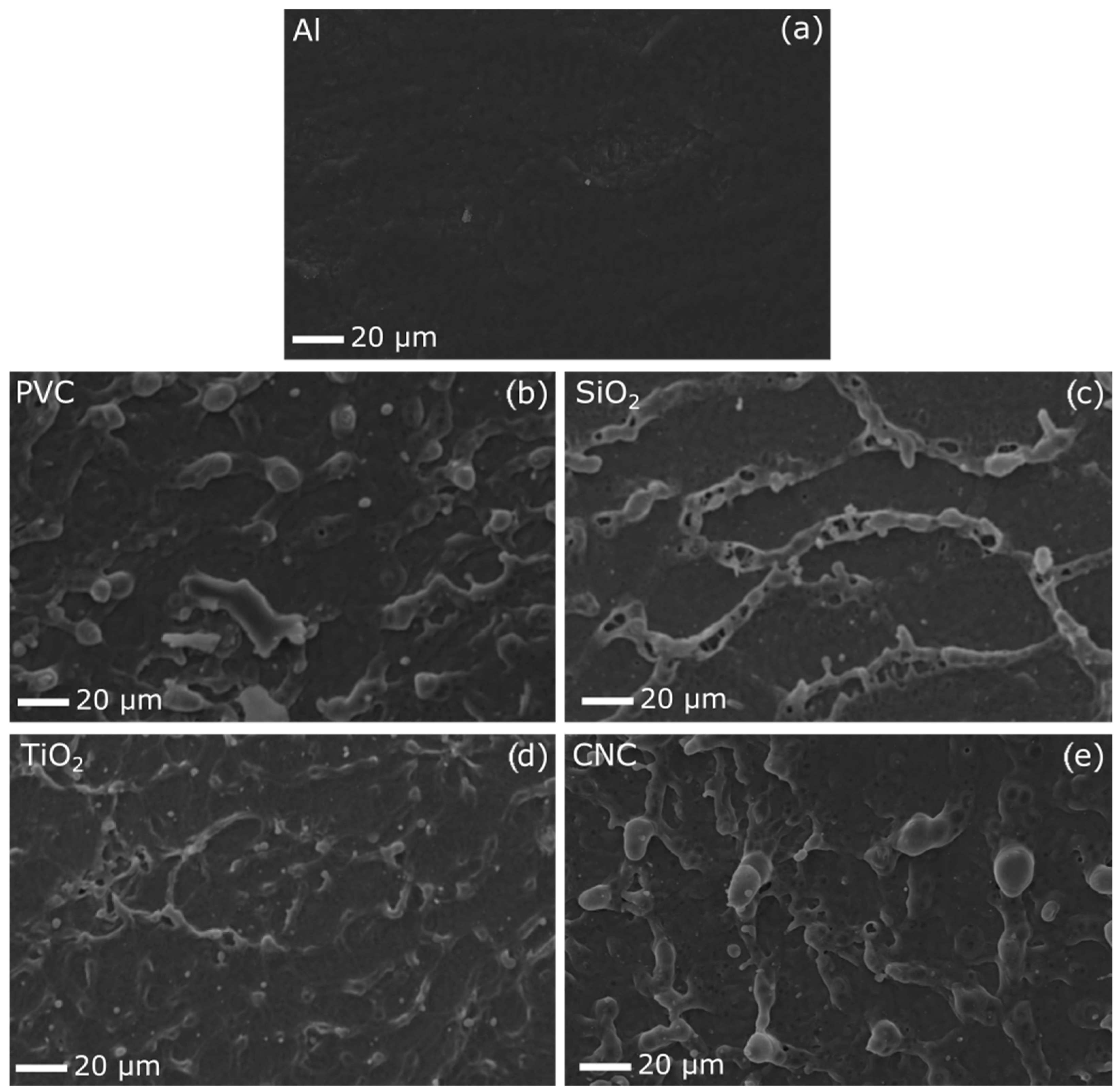

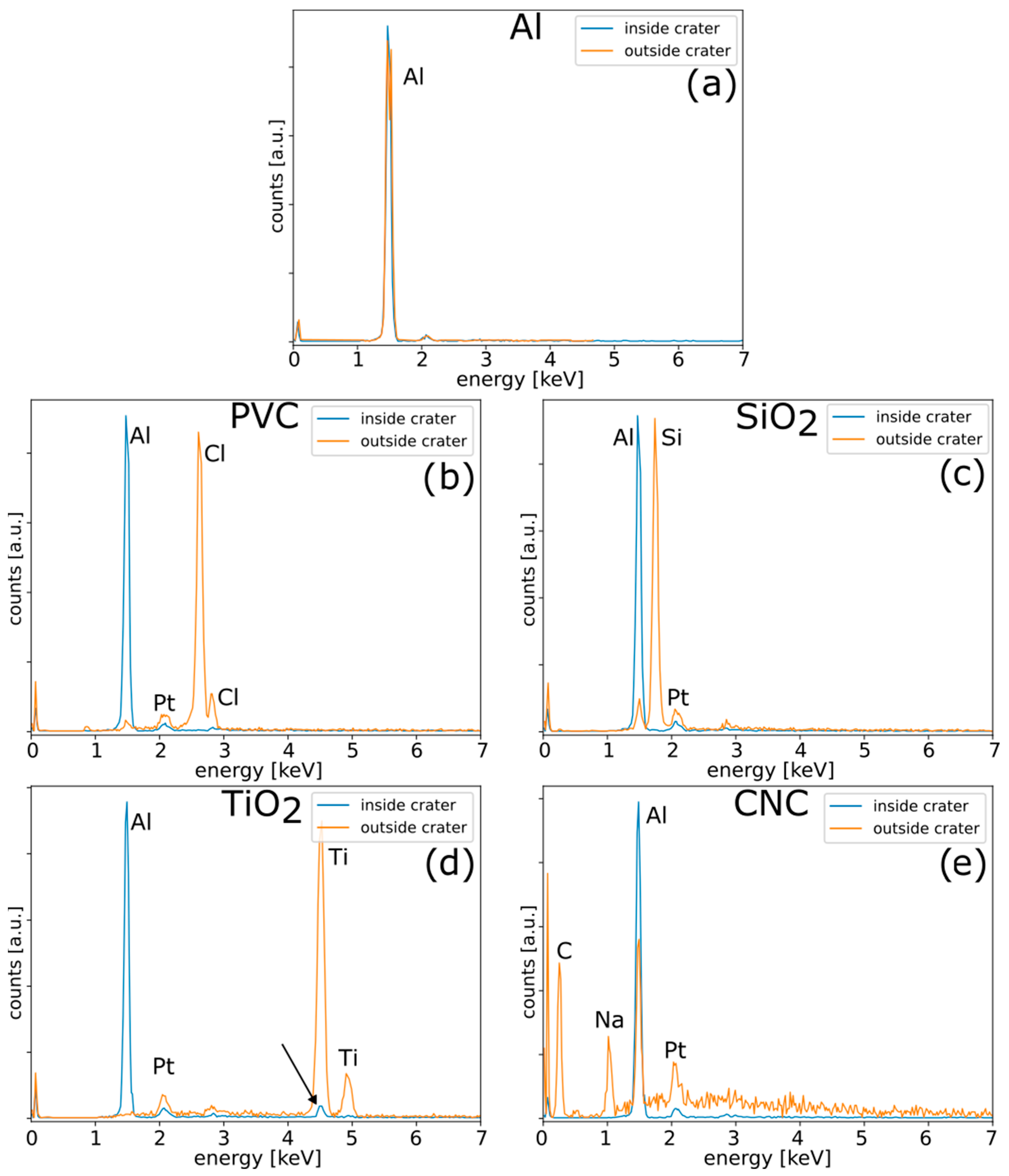

Samples are characterized before ablation by means of FTIR (PerkinElmer Spectrum Two, Shelton, CT 06484, USA) operating in ATR mode. The surface of the materials was also analyzed before and after ablation by SEM and EDS (JEOL JSM-5500, Tokyo, Japan) to clarify the role of the confinement layer in the ablation process and its effective removal. Since the deposited confinement layers are not conductive, samples were metallized with Pt/Pd before SEM characterization.

2.4. Impulse Measurements

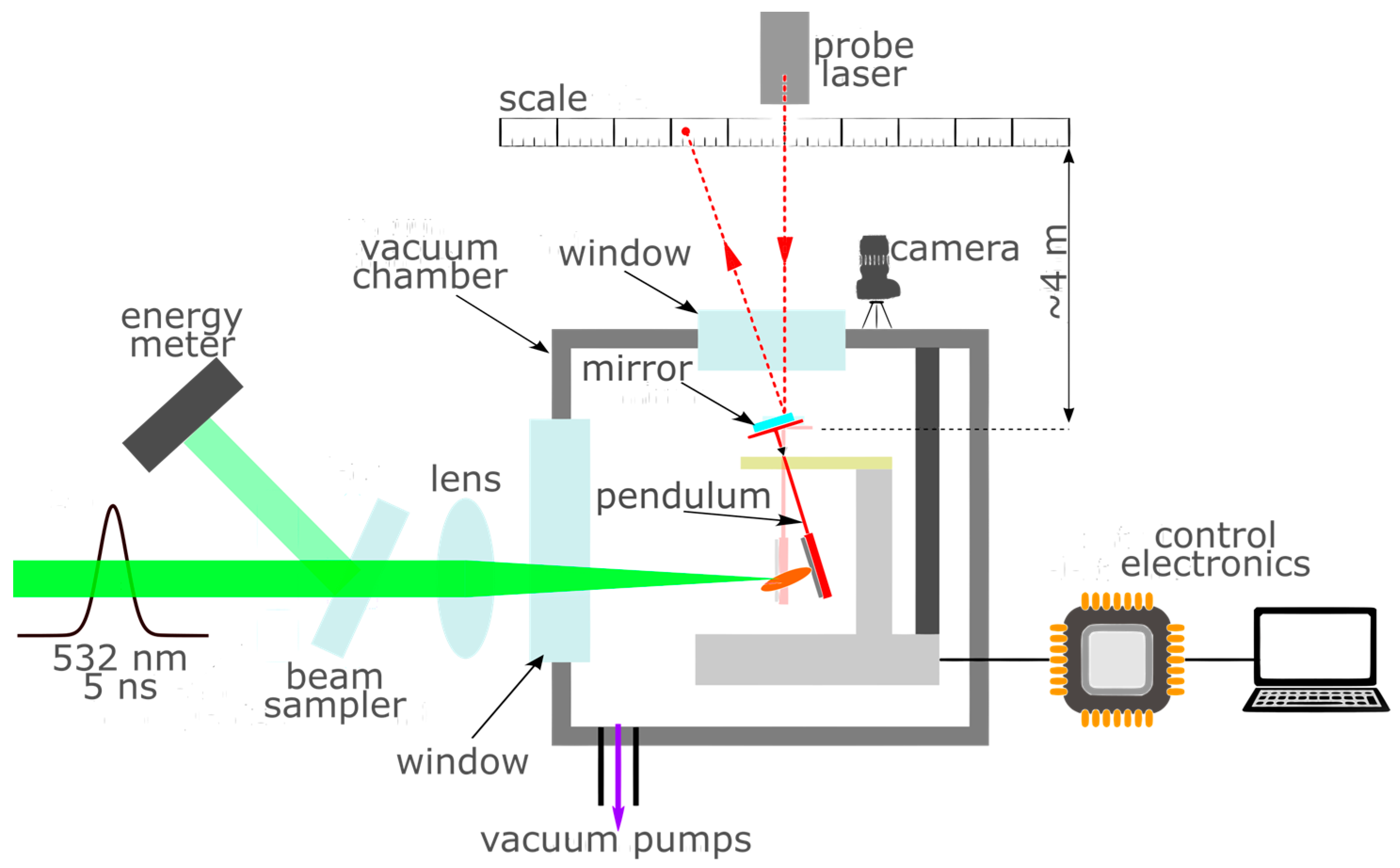

Impulse measurements were performed by means of the experimental apparatus described in detail in [

7,

23] and represented in

Figure 1.

The apparatus consists of a ballistic pendulum operating under vacuum conditions, at a pressure lower than

mbar. The impulse

generated by laser ablation after a single laser pulse is obtained by measuring the generated variation in angular momentum of the pendulum,

, through the following relation:

where

is the distance of the irradiated spot from the rotation axis of the pendulum,

I the moment of inertia of the pendulum and

is the variation in its angular velocity caused by the impulse.

is measured by reconstructing the motion of the pendulum, which is probed by means of a laser pointer reflected by a mirror fixed to the top of the pendulum. The oscillation of the pendulum, with amplitude usually smaller than 1°, is then acquired by recording the motion of the reflected probe laser on a graduated scale about 4 m away from the pendulum, in order to amplify it. The video is recorded at 1000 frames per second, and the pendulum motion is then reconstructed by an image analysis software developed in python (version 3.13.5).

Errors on

are estimated by propagating the uncertainties on the parameters of Equation (5). This procedure, described more in detail in [

23], yields errors comparable to the standard deviation of repeated measurements. The main source of uncertainty is

, since it is also dependent on the precision of the estimation of the time instant at which the impulse is generated, that is also measured during the reconstruction of the motion of the pendulum [

23]. Consequently, when higher impulses are measured, the uncertainty on

increases because, in general, larger oscillation amplitudes are observed.

In the case of the samples investigated in this work, a single laser pulse is expected to completely remove the confinement layer. A different location of the target must then be irradiated for each impulse measurement. In the present experiments, the irradiated area is and the centers of nearby craters are always at a distance of 3 .

Since the used samples are flat, the impulse generated in different regions always has the same direction. By changing the irradiated location for every laser pulse, the distance of the irradiated spot from the rotation axis of the pendulum must be taken into consideration, since it affects the estimation of the generated impulse as expressed by Equation (5). The value of is measured for each spot by image analysis.

Following Equation (5), is measured for each crater in order to estimate the generated impulse.

Due to the complex shape of the pendulum, also

must be measured. This is carried out by measuring the distance

d of the center of mass of the pendulum from its rotation axis through the following relation:

where

T is the period of the pendulum,

m is its mass, and

g is gravity acceleration. Additionally,

is measured by means of image analysis, by acquiring two images of the pendulum in equilibrium on two different points and tracing the vertical directions passing through them, so that their intersection indicates the position of the center of mass [

7].

For the impulse and ablated mass experiments, the second harmonic of an Nd:YAG laser, with a wavelength of 532 nm and a pulse duration of 5 ns was used. Measurements were made in the fluence range between 0 and 7 .

2.5. Ablated Mass Measurements

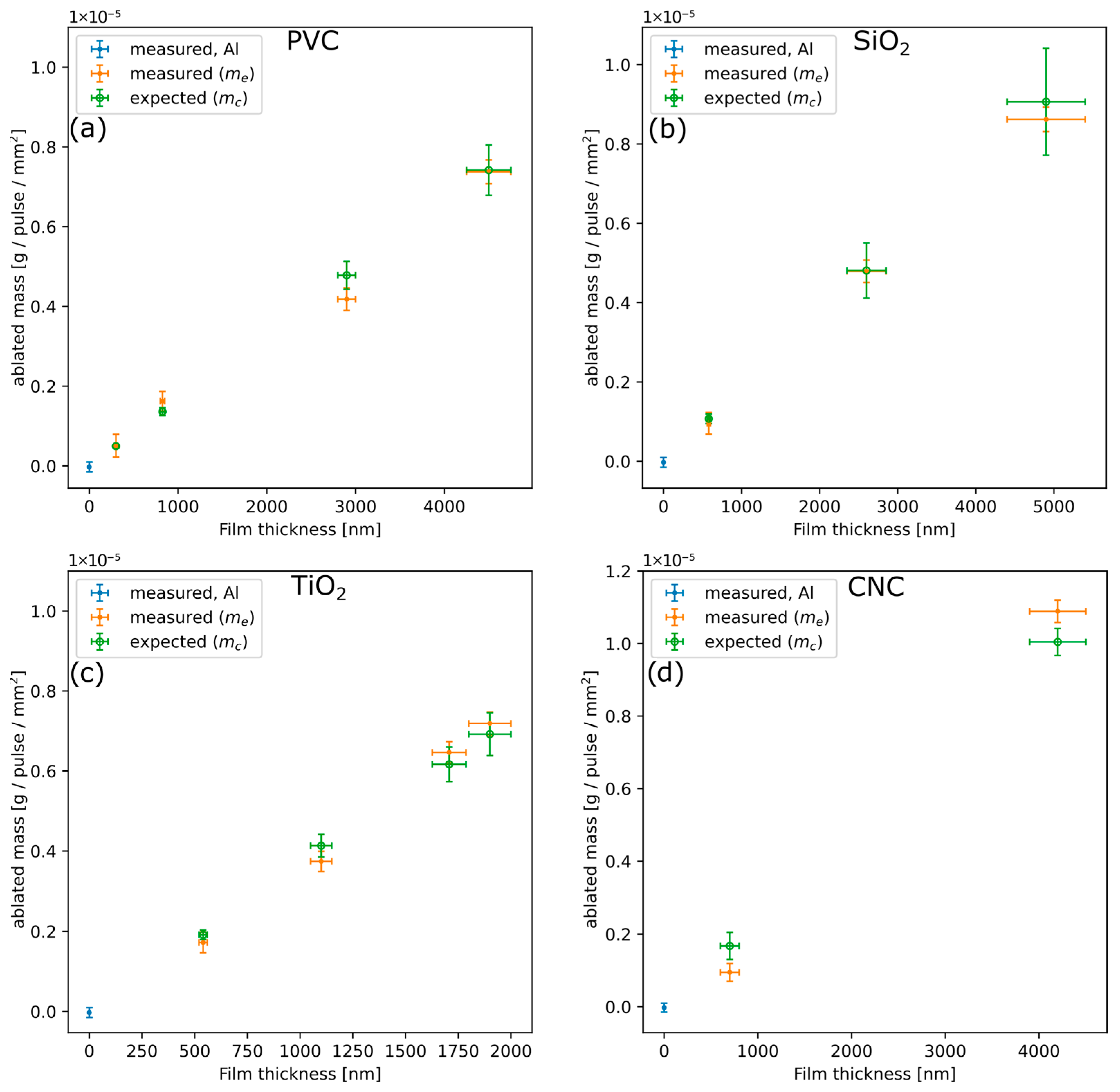

The measurement of the ablated mass was used to confirm the effective removal of the confinement layer, by comparing the measured removed mass by a single laser pulse, , with the estimated mass of the confinement layer inside the irradiated region, . In fact, if all the confinement layer is ejected from the irradiated region, with no other significant ablation products, it is expected that .

The average ablated mass per pulse was obtained by measuring the total mass difference by using a scale with g resolution after a known number of pulses at a variable fluence between ∼1 and ∼7 .

To measure , the sample was irradiated with laser pulses, moving the target after each pulse to always ablate a clean area. The distance between nearby pulses was chosen to be sufficiently large to avoid any modification of the surface due to previous irradiation in the surrounding regions. For this purpose, roughly 1 mm was always kept between the external borders of nearby craters. This distance proved to be sufficient also by the reproducibility of impulse measurements obtained by irradiation, with the same laser fluence, of different regions of the target surrounded by other craters.

The average ablated mass per pulse can then be estimated as follows:

Since the confinement layer is expected to be completely ejected after a single laser pulse independently of laser fluence, as long as it is above the removal threshold, a different fluence was used for each pulse during the measurement. In this way, if a good agreement is observed between and and it can also be confirmed that ablated mass does not depend on laser fluence. This holds for fluence high enough to remove the confinement layer; therefore, fluences in the range were used for this measurement. This range was chosen by looking at the minimum fluence at which an impulse could be measured, indicating the ejection of the confinement layer.

On the other hand,

was estimated through the following relation:

where

is the total mass of the confinement layer before irradiation, which is deposited over an aluminum substrate of known area

6 mm × 26 mm, while

is the irradiated area, kept constant for all the experiments at 5.8 ± 0.1

.

4. Discussion

The experimental investigation resulted in the acquisition of both the generated impulse and the ejected mass that was proven, for all used laser fluences, to be equal to the mass of the confinement layer inside the irradiated area.

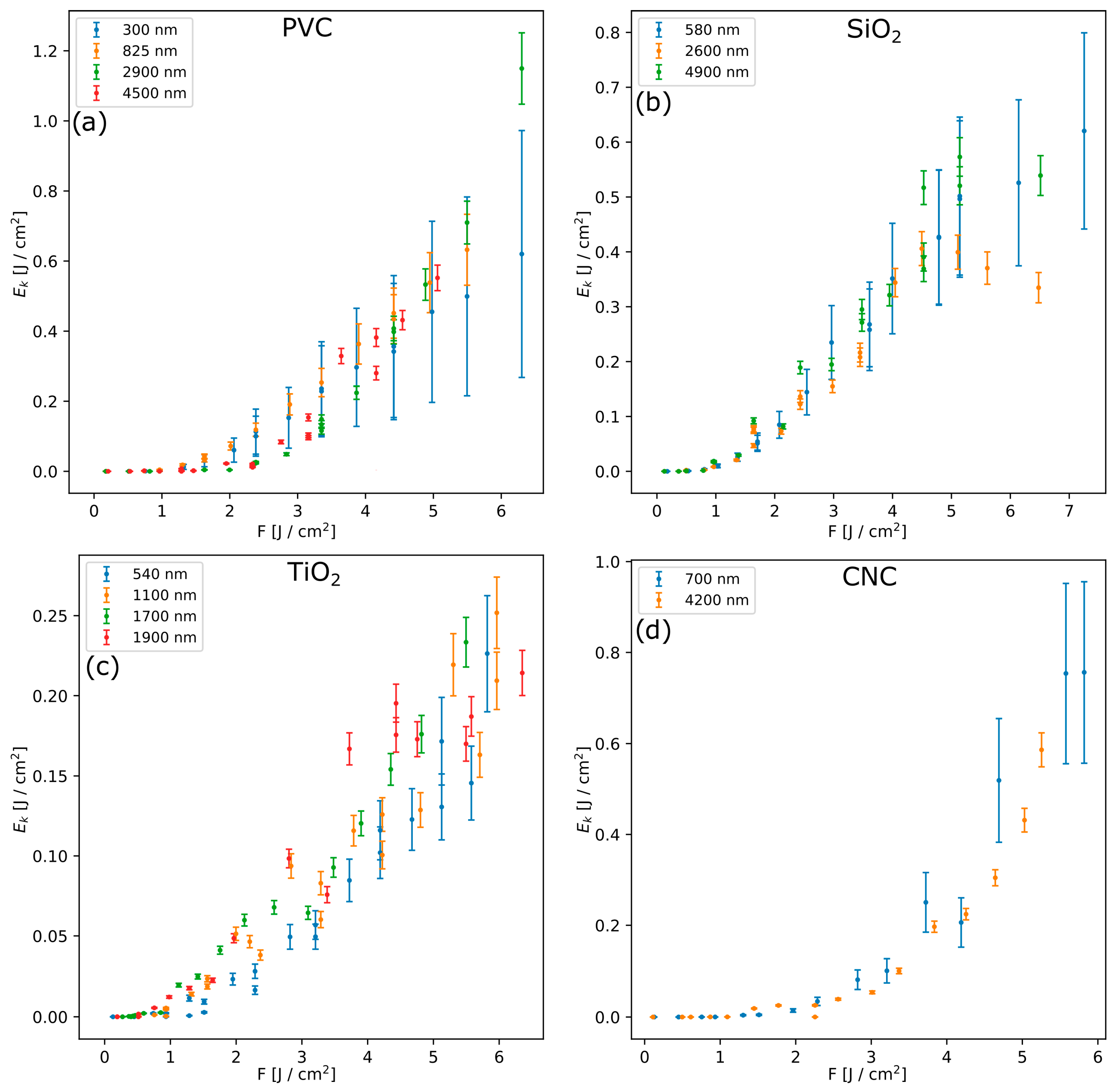

By knowing

and

, the final kinetic energy of the ejected confinement layer can be calculated as follows:

Figure 8 presents

per unit area of the ejected confinement layer as a function of laser fluence. Large errors are obtained in the case of the thinner PVC, SiO

2, and CNC films, due to the larger relative error affecting smaller

values, that propagates on the estimation of

. A similar observation can be carried out on the ejection velocity of the confinement layer (

Figure S4 supplementary information). However, the error on

decreases quickly with the thickness of the confinement layer, so that a meaningful comparison of the obtained curves is possible. As a first observation it is possible to say that similar values of

, for fixed fluence, are obtained in the case of PVC, SiO

2 and CNC confinement, while lower values are observed in the case of TiO

2.

In order to understand these results, it is possible to consider a system composed by two slabs (Al target and confinement layer) that are accelerated in opposite directions, by a force applied at their interface that we attribute to the increasing pressure of plasma generated by the laser pulses on the Al surface layers. In such a system, momentum is conserved and the work carried out by the interface pressure is converted into the final kinetic energy of the two slabs as discussed by Fabbro et al. [

16].

In the experiments presented in this work, the two slabs forming the interface have very different masses: on one side there is the aluminum substrate, which is fixed to the ballistic pendulum, so that its total mass is of a few g, while on the other side there is the ejected confinement layer, with a total mass always smaller than

g. The generated impulse is obtained by measuring the variation in momentum of the ballistic pendulum that, because of the conservation’s law, equals the momentum of the ejected confinement layer. Therefore, because of this large mass difference between the two sides of the interface, the ejected confinement moves with a velocity which is about

times the velocity of the pendulum, and of the order of few km/s as represented in

Figure S4 (Supplementary Material).

In the case of the samples considered in this work, the substrate, which was responsible for the interaction with the laser, was always kept identical. For a given confinement material, it is then reasonable to assume that the mechanical force separating the interface does not change, for the fixed laser fluence; therefore, the same work is carried out to accelerate the confinement layer and converted into its kinetic energy, independently of its thickness. This point is obviously valid in the case where the adhesion between Al and confining material is small as it happens for PVC, SiO2 and CNC given the deposition method, but not in the case of TiO2 deposited with RF sputtering which promotes greater adhesion given the initial energy of deposited atoms/ions.

By looking at

values in

Figure 8, it can be noticed that the mechanical work carried out by plasma expansion to separate the interface only counts for a fraction of the incoming laser energy. During the whole ablation process, laser energy is in fact dissipated in different ways. In particular, most of laser energy is absorbed by aluminum surface and used to increase its temperature, leading to vaporization and plasma formation. Additionally, once a plasma layer is formed at the interface, it will strongly interact with the laser too, thus exploiting the absorbed energy to both eject the confinement layer, and to increase its internal energy [

16].

Under this description, the lower

observed in the case of TiO

2 confinement, suggests that a large amount of energy is spent to overcome the adhesion force and only a part contributes to the vaporization that generates the thrust. This is consistent with EDS results in

Figure 7.

5. Conclusions

PVC, SiO2, TiO2 and CNC layers, with thickness between 300 nm and 5 μm, have been deposited on polished aluminum, used as a common substrate, to investigate the confinement of laser ablation plasma plume by thin layers as an effective way to enhance thrust generation.

The optical properties of the deposited layers have been assessed by UV-vis spectroscopy. Transmittance measurements showed that all the considered confinement materials weakly absorb the laser radiation at the used wavelength, as required to achieve effective confinement, while optical interference observed in reflectance spectra was exploited to compute film thickness.

Impulse measurements demonstrated that thin films can effectively enhance impulse generation by confining the expansion of the laser generated plasma plume. Additionally, higher impulse is observed for thicker confinement.

To confirm that laser ablation effectively occurs with the ejection of the confinement layer, ablated mass measurements were conducted. Results showed that the average ablated mass per pulse corresponds to the mass of the confinement layer inside the irradiated region. In addition, it is observed that ablated the mass per pulse does not depend on laser fluence, provided that it is sufficiently high to remove the layer, and that ejected aluminum mass is negligible compared to the mass of ejected confinement layer.

In order to discuss the effect of the confinement layer on the ablation process, SEM and EDS analysis were conducted. The morphology of the ablation craters shows that the confinement layer promotes the melting of aluminum surface, while the elemental composition of the generated craters confirmed the complete ejection of the confinement layer, except for the case of TiO2 confinement.

The generated impulse and ejected mass allowed to calculate the kinetic energy of the ejected layer, showing that, setting the laser fluence in the range , it does not depend on its thickness.

obtained for the different confinement materials were compared, observing that smaller values are obtained in the case of TiO

2. This result was discussed in terms of energy balance by referring to the model of Fabbro et al. [

16], showing that, because of the different deposition method, TiO

2 has a better adhesion on aluminum and that a large amount of energy is spent to overcome the adhesion force.

This work offers an experimental insight into impulse generation by laser ablation in a confined regime, in the case of thin confinement layers, indicating that the process is driven by the amount of laser energy that can be converted into mechanical work and that this conversion can be strongly affected by the interface properties.

The obtained results take advantage of the well-known geometrical properties of the investigated samples to point out more general properties of impulse generation in confined ablation regime. This knowledge can help in the development of materials that exploit this mechanism, allowing to optimize the thickness and mass of the confinement layer for a specific mission and overcome the present limitations of this technique.