Abstract

In the realm of software development, quality reigns supreme, but the ever-present danger of vulnerabilities threatens to undermine this fundamental principle. Insufficient early vulnerability identification is a key factor in releasing numerous apps with compromised security measures. The most effective solution could be using machine learning models trained on labeled datasets; however, existing datasets still struggle to meet this need fully. Our research constructs a vulnerability dataset for Android application source code, primarily based on the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) system, using data derived from real-world developers’ vulnerability-fixing commits. This dataset was obtained by systematically searching such commits on GitHub using well-designed keywords. This study created the dataset using vulnerable code snippets from 366,231 out of 2.9 million analyzed repositories. All scripts used for data collection, processing, and refinement and the generated dataset are publicly available on GitHub. Experimental results demonstrate that fine-tuned Support Vector Machine and Logistic Regression models trained on this dataset achieve an accuracy of 98.71%, highlighting their effectiveness in vulnerability detection.

1. Introduction

Every month, developers introduce over 50,000 fresh Android apps to the Google Play Store’s catalog [1]. In the first quarter of 2024, Android’s market share was around 70.7 [2]. Android’s position as a leading mobile platform with an open ecosystem has made it an attractive target for those seeking to exploit digital vulnerabilities [3]. This is accompanied by a worrying prevalence of insecure coding practices, creating a landscape rife with potential entry points for malicious activities. For instance, a large-scale analysis of mobile health apps on Google Play [4] shows that most of the health applications contain severe security issues that may lead to exposing user’s sensitive information.

The automatic detection of security vulnerabilities is a fundamental challenge in system security. Researchers have found that traditional techniques often struggle with high false positives and negative rates [5,6]. For example, tools based on static analysis typically produce many false positives, meaning they flag issues as vulnerabilities when they’re actually not. On the other hand, dynamic analysis tends to have high false negative rates, failing to catch many real vulnerabilities. Even after years of effort, these tools remain unreliable, leaving developers with a significant amount of manual work [7,8].

Static Application Security Testing (SAST) plays a crucial role in identifying vulnerabilities early in the software development life cycle (SDLC) [9]. Despite its importance, assessing the effectiveness of SAST tools and determining which performs best at detecting vulnerabilities remains a complex challenge. This research [10] aims to evaluate the effectiveness of Java’s static application security testing (SAST) tools and their consistency in detecting vulnerabilities. The study’s findings indicate that although the evaluated SAST tools perform well in synthetic test environments, they fail to detect most real-world vulnerabilities. The authors highlight the importance of incorporating real-world benchmarks and standardized vulnerability classifications, such as CVE, in developing and assessing SAST tools.

Source code analysis is an essential step in vulnerability detection as it allows developers to identify programming errors and potential security risks. However, traditional source code analysis methods can be time-consuming and often rely on manual inspection. To mitigate the challenges posed by manual source code analysis, researchers have recently started exploring the application of machine learning techniques in vulnerability detection processes [11]. Machine learning techniques offer the potential to automate and streamline the vulnerability detection process by automatically analyzing source code and identifying potential vulnerabilities.

For machine learning to be effectively trained, a dataset is required. The reliability of the trained model and results depends on how comprehensive and realistic the dataset is. We noticed that when the developer would like to fix a vulnerability in their code base, they generally add a relevant comment in their commit describing what that code is fixing. In this study, we used the bigquery-public-data.github_repos [12] open-source big data on Google BigQuery—which includes all repositories, file contents, and commit data created on GitHub from a certain year onward—to collect vulnerable code from real-world sources. Our aim in obtaining real-world vulnerable code is based on the relevant study [13] finding that synthetic data is significantly inadequate in identifying real-world application vulnerabilities. Additionally, it appears that there is a need for real-world vulnerable Android application code datasets in the literature.

This study has made the following significant contributions to the literature, which will assist future academic researchers in automatically detecting vulnerabilities in Android applications.

- A novel dataset of vulnerable Android application codes, AndroCom, with the below key features.

- A Github mirror scans it from Google BigQuery [12], storing TB of data and millions of code repositories, considering vulnerable code samples with well-designed search keywords to locate vulnerable codes.

- This study centers on Android application code as a key resource for Android research and intentionally excludes open-source tools during dataset creation to avoid limitations and false positives.

- It is a labeled vulnerable code dataset by searching via strong indication of vulnerability in commit messages, focusing on past vulnerabilities, examining CVEs, and the fixes implemented by developers.

- The dataset is designed to update dynamically, allowing it to defend against new and emerging vulnerabilities. It is also publicly available as a Github repository, along with all required scripts used to create it.

The structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on the topic, while Section 3 focuses on a detailed process of proposed dataset creation. Section 4 explores how AndroCom datasets can be leveraged to train machine learning models to detect Android code vulnerabilities. Finally, Section 5 concludes with a discussion of the results and outlines future directions for research.

2. Related Work

This section reviews relevant studies on code vulnerabilities and available datasets that support the detection of software vulnerabilities through machine learning techniques.

Organizations and communities identify various vulnerabilities, each documented with a unique CVE ID for reference. Both security researchers and developers widely use CVE to report and reference weaknesses and vulnerabilities across multiple programming languages. Consequently, mobile application developers also rely on these references to identify vulnerabilities and address security issues within their source code.

This work [14] introduces Defendroid, a system utilizing a blockchain-based federated neural network model and Explainable AI to achieve real-time detection of vulnerabilities within Android source code as it is being written. However, it seems that the current version of Defendroid is limited in its ability to detect complex vulnerability patterns that span multiple code segments or files. Furthermore, while the study demonstrates Defendroid’s efficiency in analyzing single lines of code, its performance in scanning entire real-world projects, which often consist of thousands of lines of code, needs further investigation and optimization to ensure practical usability. Similarly, Zhang et al. [15] explored machine learning models to predict Android vulnerabilities in IoT apps, using 21 static code metrics across 1406 apps. Random Forest showed the best performance, though limitations included a small sample size and dataset imbalance. Rahman et al. [16] analyzed 1407 Android apps using static code metrics and statistical models to predict security risks, with radial-based support vector machines (r-SVM) achieving a precision of 0.83. VuRLE [17] focuses on repairing vulnerabilities in Java code by learning from prior edits and applying automatic patches. It outperformed the LASE approach and was evaluated using highly rated GitHub projects. Vulvet [18] employs a multi-tiered static analysis framework to detect and patch Android vulnerabilities, achieving high precision and F-measure. However, limitations included a lack of support for native code and dynamic loading. In this reference [19], machine learning analysis is applied to distinguish between vulnerable and non-vulnerable source code by extracting the Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) of a code fragment, converting it into a numerical array, and retaining the structural and semantic details embedded in the code with a hybrid method. While C and C++ codes are used as target languages, the authors mentioned that the method proposed can be applied to predict vulnerabilities of other languages in conditions where a good dataset is used.

Other studies investigated ML-based vulnerability detection. A hybrid model proposed by [20] achieved 77% accuracy in detecting Android Intent vulnerabilities but faced limitations due to the small sample size. A study, [21], introduced a deep neural network for vulnerability prediction, using n-gram mining for feature extraction, but noted internal threats such as the exclusion of XML data. Gupta et al. [22] generated vulnerability detection rules using PMD tool data, manually labeled apps, and tested ML algorithms with 10-fold cross-validation, highlighting the time-intensive process of manual dataset construction.

Mazuera-Rozo et al. [23] conducted an empirical study of Java and Kotlin Android apps, identifying common security weaknesses and revealing a lack of academic tools developers use for security detection. They researched vulnerable cases through Githubarchive using a set of keywords that potentially showed where developers fixed the vulnerabilities through commits.

Zhou et al. [24] aim to develop an automated system to identify previously undetected vulnerabilities in open-source libraries by analyzing commit messages and bug reports. While focusing solely on the developer’s commit message data in cases of vulnerability remediation can yield quick and effective results, these messages are often brief and may lack detail, necessitating an examination of the source code for accurate vulnerability identification. Therefore, evaluations and analyses conducted directly on the source code will likely yield more precise results. Similarly, VCCFinder [25] combines code metrics with GitHub metadata and utilizes a support vector machine (SVM) to flag potentially vulnerable commits. By identifying commits that fix security vulnerabilities, it aims to predict potential vulnerabilities heuristically. However, the primary limitations of this approach include a highly restricted dataset and a focus on only one specific programming language. As an interesting study around Android applications [26], it developed a machine learning system that analyzes Android app code to generate functional descriptions with 69–84% accuracy. This approach aids security inspections by providing contextual insights into app behavior.

In reference [27], the conducted work describes a dataset of real-world software vulnerabilities from the Android Open Source Project (AOSP). The dataset links these vulnerabilities to the specific code changes (commits) that fix them, providing valuable information for security researchers. However, the dataset has limitations. It only includes vulnerabilities from open-source projects and relies on Google’s Security Bulletins for information. Despite these limitations, the dataset can be used to understand vulnerabilities, analyze how they are fixed, and develop better vulnerability detection tools. Similarly, the study [8] focuses on vulnerability-fixing commits to detect vulnerabilities employing various models.

Furthermore, research in the reference [28] introduces a labeled dataset of Android source code vulnerabilities called LVDAndro to help Android app developers identify source code vulnerabilities in real time. The dataset is limited by the number of vulnerability scanners, which generally produce lots of false positives used to create and have a smaller number of code examples featuring CWE-IDs that are less common in real-world applications.

Detecting vulnerabilities in Android applications remains challenging due to the inadequacy of existing datasets, which do not sufficiently support the training of machine learning (ML) models. This issue is further compounded by the lack of sufficient real-world data required for building such models. To address this problem, this study presents a dataset created from real-world data, including snippets of source codes following the developers’ activities when fixing the vulnerabilities in its code base.

Although vulnerability detection and malware detection are often mistakenly treated as interchangeable, they are fundamentally different, with distinct objectives and underlying dynamics. Vulnerability detection specifically focuses on identifying weaknesses in systems that could be exploited, whereas malware detection aims to uncover harmful software or behavior. Understanding these distinctions is critical for understanding this study’s contribution, which aims to advance the field of vulnerability detection by addressing key gaps in real-world dataset availability and reproducibility.

Some key studies [29,30,31,32] examined in this review [33] have explored various challenges in Android malware detection, many of which hold valuable insights for improving vulnerability detection methods. A recurring issue is the heavy reliance on outdated or small datasets, such as MalGenome [34] and Drebin [35], which fail to capture modern threat dynamics. This limitation hinders the training of robust machine learning models and often results in overfitting. Combining static and dynamic analysis has been proposed as a solution, as static features are vulnerable to obfuscation, while dynamic features, though more robust, are harder to collect. Another concern is the inconsistency of in-app behavior across devices, which complicates detection accuracy, particularly in large-scale systems like federated learning. These challenges highlight the importance of using up-to-date datasets, incorporating adaptive modeling, and addressing the complexities of evolving threats. Lessons from these studies could also guide future efforts to make vulnerability detection more effective and resilient in real-world applications. Authors in study [36] propose a supervised learning approach for Android malware detection using a labeled dataset of over 18,000 samples across five categories, validated with multiple benchmark datasets. The method demonstrates competitive performance compared to state-of-the-art techniques, offering insights into malware classification and detection improvements.

The current study aims to locate real-world Android application codes by investigating vulnerability-fix commits and obtaining vulnerable source code slices for future machine-learning research. The following research questions identify the reasoning and key points behind this initiative.

Research Questions (RQs)

- Why are we doing this?

Since it is shown that using synthetic datasets is not as effective as it should [13], working with real-world code is crucial. To the best of our knowledge, although a couple of malware datasets are available, there is a lack of properly labeled vulnerable code datasets in Android applications in the literature to assist with automated ways of conducting vulnerability research [37]. Therefore, it will be addressing this gap once it has been done.

- 2.

- Why is it important?

As our lives become increasingly digitalized, spotting vulnerabilities before malicious actors exploit them is becoming more critical. Therefore, efficiently detecting vulnerable code has gained significant importance in today’s world, and novel ML/DL methods are emerging to identify and mitigate security risks. Unlike many previous approaches [15,16,20,21,22,28], our method leverages real-world vulnerability fixing commits, allowing the detection models to learn from actual security patches. This real-world data enhances the model’s ability to identify complex, real-world vulnerabilities that are often encountered in practice, improving its effectiveness in real-world software environments.

- 3.

- Which benefits can we have after this research?

This study contributes to vulnerability detection research by constructing a dataset derived from real-world code changes, addressing a critical gap in the availability of publicly accessible vulnerable code samples. The dataset facilitates the development and evaluation of machine learning models in real-world scenarios, improving the generalizability and reliability of automated vulnerability detection approaches. Furthermore, by leveraging real-world vulnerability fixes, this research enhances the reproducibility of security studies and supports the advancement of tools and techniques for secure Android development.

- 4.

- Why is this a unique study?

Some previous studies [28] have relied on specific tools for dataset creation, and the false-positive results produced by these tools have been identified as a significant factor affecting system performance by leading to incorrect learning. Additionally, earlier works [24,25] primarily focused on commit messages without incorporating the associated source code, making this study unique in its approach. Furthermore, some studies ([15,21]) still use old datasets with static code metrics only.

3. Dataset Creation Process

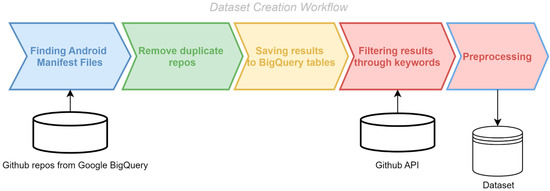

The AndroCom dataset is an extensive and varied collection of labeled data tailored to meet the challenges involved in identifying vulnerabilities in Android source code through machine learning techniques. The unique part of our dataset is that it is derived from commit data, where developers have fixed vulnerabilities in their code based on real-world environments. Figure 1 visualizes this dataset’s high structure level and illustrates its construction.

Figure 1.

Real-world vulnerable commit-based dataset creation process.

3.1. Finding Android Manifest Files

The initial step in creating the dataset is data collection. This begins with opening a project file in the Google BigQuery console, specifically targeting the github_repos dataset within BigQuery. Within this dataset are the commits, contents, and files tables. The first task is to extract data from the files table. Here, we check for the presence of the AndroidManifest.xml file across all repositories, logging the results in a separate table. If a repository contains this file, it falls within the scope of our study and becomes a source for constructing our dataset. Phases 1–3, illustrated in Table 1, are done in this part. The reasoning for the decision in Phase 3 has some concerns. Firstly, suppose a developer specifies in the commit message that they are addressing a security vulnerability, and only one file is modified. In that case, it is certain that the fix occurred within that file. Secondly, because the goal is to classify the type of security vulnerability addressed in each commit, analyzing fixes that involve multiple files can be complex and may result in misclassification.

Table 1.

General conditional workflow of the activities before we do preprocessing.

Note that the activities conducted in this part involve writing appropriate SQL statements within the BigQuery console. The relevant SQL queries will also be shared along with the dataset.

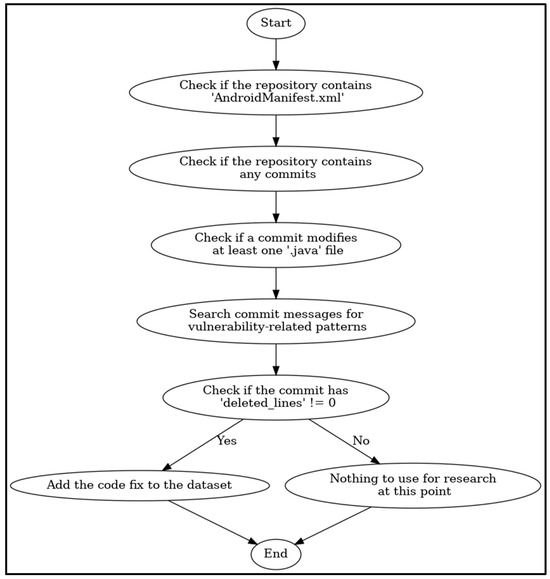

Figure 2 illustrates the workflow for extracting vulnerable commits related to Android applications. Each phase of the process is visually represented, starting from identifying the repository and concluding with integrating relevant fixes into the dataset. The diagram highlights key decision points and conditions for each step.

Figure 2.

Vulnerable commit extraction process.

3.2. Remove Duplicate Repositories

Once a GitHub project is created, anyone can copy (fork) or download (via git clone or regular download) the repository, provided the developer has not implemented a restrictive policy. A key point to consider here is that if a project is forked on GitHub, all historical data up to the point of forking—such as commit history and project files—will also be duplicated in the forked repository. Without filtering these forked repositories to identify unique ones, the dataset may contain redundant data from duplicate projects. Therefore, checking for and eliminating duplicate entries in the collected data is essential. This stage of the study involves carrying out these activities to ensure data uniqueness.

3.3. Saving Results to BigQuery Tables

In this step, the outputs from the activities performed in the previous steps were recorded. After duplicate entries were removed from the data obtained in Step 3, the results were saved as a table in the BigQuery environment. Once this stage was completed, it was assessed that all information was ready for the processes in the next steps.

3.4. Filtering Results Through Keywords

We collected commits from GitHub via BigQuery from 366,231 projects. Given the vast amount of information involved in such a large-scale tracking task, we filtered out commits that were clearly unrelated to security by applying a set of regular expression rules. When it comes to creating regular expressions for this research, we drew inspiration from a previous study [23], where the keywords used served as a starting point for our work. Considering the potential for generating false positives to the best of our knowledge, we removed certain keywords and added others that we identified as missing to enhance coverage. This process resulted in a more efficient list of keywords. To ensure comprehensive coverage of potential vulnerabilities, our regular expression rules encompass a wide range of expressions and keywords related to security issues, including terms like vulnerability, CVE, SQLi (SQL Injection), and XSS (Cross-Site Scripting) (refer to Table 2 for a portion of the rule set). As a result, we created a dataset of GitHub commits. Furthermore, it is shared that some of the CVEs that are fixed and critical vulnerabilities are covered in this dataset (refer to Table 3).

Table 2.

Examples of regular expressions used to filter vulnerable commits.

Table 3.

Examples of covered vulnerabilities in our dataset with CVEs.

Table 2 illustrates some sets of examples of regular expressions designed to identify and filter vulnerable commits in source code repositories. These expressions target specific keywords and patterns commonly associated with software vulnerabilities. By systematically analyzing commit messages, the approach leverages these regular expressions to detect potentially vulnerable code changes efficiently. The regular expression patterns are case-insensitive (denoted by (?i)) and include variations of terms to account for different formatting styles. Additionally, they incorporate optional and alternative spellings (e.g., unauthori[z|s]ed) and wildcard matches (e.g., vulner[a-z]+) to ensure a comprehensive search.

The “Rule” categorizes the types of vulnerabilities targeted, while the “Regular Expression” column contains patterns that identify key terms or phrases related to these vulnerabilities. The rules are broadly classified into two categories:

- General Vulnerabilities: This includes patterns for common security issues, such as Denial of Service (DoS), Cross-Site Scripting (XSS), SQL Injection (SQLi), and Remote Code Execution (RCE). Regular expressions for these vulnerabilities are structured to capture variations in terminology and case sensitivity, ensuring comprehensive detection.

- Mobile-Specific Vulnerabilities: These patterns focus on issues prevalent in mobile application development, such as sensitive data exposure, improper validation, and the use of hard-coded credentials. The expressions aim to enhance security in mobile software environments by addressing mobile-specific risks.

For instance, the regular expression (?i)(denial.of.service|\bXXE\b|remote.code.execution|...) matches a variety of keywords indicative of general vulnerabilities, including technical terms like “XXE” (XML External Entity) and broader descriptors like “unauthorized” or “insecure.” Similarly, the expression for mobile vulnerabilities, (?i)(information.exposure|sensitive.(?:information|data|communication)|...), identifies concerns such as the exposure of personal information or the use of shared resources without proper controls.

By applying these rules, the filtering mechanism ensures that only commits that are highly likely to contain vulnerability-related fixes or changes are selected for further analysis. This targeted approach reduces noise and improves the efficiency of the dataset construction process. The regular expressions in Table 2 are used to search the commit messages of Android application repositories on GitHub, filtering commits that include vulnerable code.

We utilized initial training data from March 2016 to February 2023, aligning with Google’s open-source GitHub data. Within the commit dataset, we identified that 20,004 commits are related to vulnerabilities. It is important to note that this dataset can be regularly updated based on the data available in Google’s dataset, allowing us to keep our codebase aligned with newly discovered and fixed vulnerabilities.

3.5. Preprocessing

It is essential to preprocess the data to effectively apply machine learning techniques to vulnerability detection in source code. This involves tasks such as the following:

- Identification of malformed code—Code fragments may be incomplete or syntactically invalid. These segments can be recognized using a compiler or static analysis tool and marked appropriately [40].

- Removal of noise and irrelevant features—Code may contain comments, whitespace, and other non-essential elements that can negatively impact the performance of the machine learning models [41].

- Standardization of code formatting—Inconsistent formatting and coding styles can hinder learning. Standardizing the code format can improve the model’s ability to detect patterns [42].

Since we gathered the data from commits that are vulnerability-fix ones, they generally are not complete, mostly involving snippets of code or part of the code that fixes the bugs that the developer intended. Therefore, identification of the code may result in inconsistent analytics. However, removing noises such as comments, blank spaces, and some elements that don’t affect the meaning of the code but improve the data for machine learning processes may make the analytics more consistent.

Creating a balanced dataset is a critical prerequisite for building effective machine-learning models, particularly in the context of vulnerability detection. An imbalanced dataset, where one class dominates the other, can lead to biased models that fail to generalize to unseen data. For this reason, it was essential to ensure that secure (non-vulnerable) code commits were collected in comparable proportions to the already identified vulnerable commits. A balanced dataset allows the model to distinguish between secure and vulnerable code more accurately, reducing the risk of class imbalance skewing the results. This approach enhances the reliability and robustness of the machine learning system when applied to real-world scenarios.

Identifying and extracting secure (non-vulnerable) code commits was designed as a systematic workflow to complement the collection of vulnerable code. The initial step involved curating a list of repositories from GitHub, stored in a designated file for structured access. These repositories were programmatically traversed using the GitHub API, and commits were iteratively fetched for examination. To filter out vulnerable commits, a predefined set of keywords associated with security patches or fixes—such as “fix”, “patch”, “CVE”, or “vulnerability”—were applied to commit messages. Commits lacking these indicators were classified as “safe” and stored for further analysis.

The script implemented a dynamic rate-limiting mechanism to ensure the process adhered to GitHub’s API rate limits (5000 requests per hour). If the API limit was reached, the system automatically paused for the required duration before resuming operations. This enabled uninterrupted data collection without exceeding usage quotas. The workflow continued until the number of secure commits exceeded a predefined threshold, slightly surpassing the number of vulnerable commits for dataset balance. All collected data, including repository names, commit hashes, and messages, were systematically stored in a JSON file for subsequent use in machine learning-based vulnerability detection.

4. The Dataset Usage

The dataset presented in this study is a comprehensive collection of code changes derived from software repository commits. It includes both added_lines and deleted_lines extracted from commit histories. This dataset has been designed to support machine learning models in detecting and analyzing vulnerabilities in software systems. Below, we detail the methodologies and processes employed to utilize the dataset effectively for research purposes.

4.1. Data Extraction and Feature Selection

Initially, commit histories were parsed to extract code snippets corresponding to added_lines and deleted_lines. These represent modifications made to the source code during each commit. In this context, deleted_lines represent vulnerable code snippets, while added_lines denote the corrected code addressing the vulnerabilities. The extracted data was preprocessed to ensure consistency and quality. Preprocessing steps included the following:

Tokenization—Using regular expressions, all lines of code were split into meaningful tokens, which included keywords, variable names, function calls, and operators.

Normalization—Code-specific artifacts, such as indentation and formatting, were normalized to reduce noise.

Feature Engineering—Semantic and structural features were derived from the code, such as function call counts, try-catch block occurrences, and usage of critical APIs. These features provide valuable insights into the code’s functional and security characteristics.

4.1.1. Feature Representation: Word2vec and Principal Component Analysis (PCA)

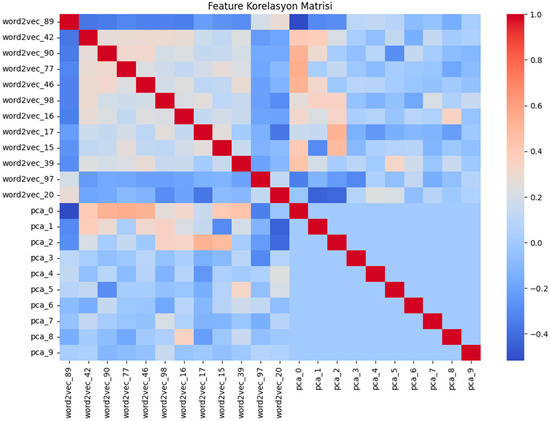

Extensive preprocessing was conducted, including feature extraction from source code, token frequency analysis, and word embeddings using Word2Vec. To enhance feature representation, we applied dimensionality reduction techniques such as (PCA) and the most relevant features based on correlation analysis, as shown in Figure 3. We also introduced composite features, such as the ratio of conditional statements (if-else structures) and a combined try_catch metric to capture exception-handling behavior. These transformations ensured the dataset was computationally efficient and representative of vulnerability-related code characteristics.

Figure 3.

Feature correlation matrix.

4.1.2. Word2Vec Features

To capture the semantic meaning of the source code, we employed Word2Vec, a word embedding technique that maps words (or tokens) into a continuous vector space.

Each code snippet was transformed into a numerical vector, preserving token relationships. These vectorized features are denoted as word2vec_0, word2vec_1,..., and word2vec_99, where each dimension represents a learned semantic property.

4.1.3. PCA-Based Dimensionality Reduction

Word2Vec vectors tend to be highly dimensional, which may lead to overfitting and increased computational cost. To mitigate this, PCA was applied to reduce the number of features while preserving as much variance as possible. The resulting features, pca_0, pca_1, …, and pca_n, represent the most informative principal components. This approach improves model efficiency while retaining essential information.

Combining Word2Vec embeddings and PCA-transformed features benefits the model from semantic understanding and optimized feature representation, leading to improved generalization.

4.1.4. Experimental Setup

The experiments were conducted on Google Colab Pro [43], utilizing a high-RAM environment (50.99 GB) with an optimized CPU. The primary libraries used for feature engineering and model training included the following:

- scikit-learn [44] for machine learning models, hyperparameter tuning, and cross-validation;

- Pandas [45] for data manipulation and preprocessing;

- Matplotlib 3.9.0 & Seaborn 0.3.12 for data visualization;

- Google Colab’s cloud-based runtime to leverage computational efficiency.

We employed multiple machine learning classifiers for model training, including Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machines (SVM), Random Forest, XGBoost, and Gradient Boosting, as shown in Table 4. Hyperparameter tuning was performed using GridSearchCV from the sci-kit-learn library, with k-fold cross-validation (k = 3) to ensure robustness. The best-performing model, a fine-tuned logistic regression and support vector machine, achieved an accuracy of 98.71% on the test set, demonstrating its effectiveness in distinguishing vulnerable code snippets from non-vulnerable ones. Performance across training, validation, and test sets was evaluated to mitigate overfitting.

Table 4.

Performance results with the best hyperparameters.

The following metrics are used for evaluation: accuracy, precision, recall, and F1 score.

- -

- Accuracy is the ratio of correctly predicted functions to the total number of functions.

- -

- Precision measures the model’s ability to predict vulnerable functions accurately.

- -

- Recall assesses the number of correct predictions made for all vulnerable functions in the dataset.

- -

- F1 Score is the harmonic mean of precision and recall values, providing a single score that makes it a more valuable metric. Formulas of performance metrics used in the study are as follows:

Definitions are as follows:

- TP (True Positive)—Correctly predicted vulnerable code.

- TN (True Negative)—Correctly predicted non-vulnerable code.

- FP (False Positive)—Incorrectly classified safe code as vulnerable.

- FN (False Negative)—Incorrectly classified vulnerable code as safe.

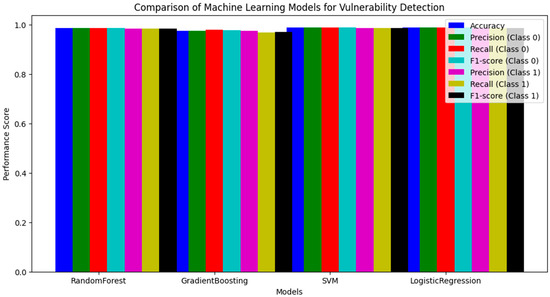

Figure 4 presents a comparative analysis of machine learning models for vulnerability detection. The bar chart illustrates the performance of four models—Random Forest, Gradient Boosting, SVM, and Logistic Regression—across key evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The results are reported separately for class 0 (non-vulnerable) and class 1 (vulnerable) instances. This visualization provides a clearer comparison of model effectiveness, complementing the tabular representation in Table 4.

Figure 4.

Comparison of Machine Learning models for vulnerability detection.

4.1.5. Comparison with Existing Studies

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of various machine learning-based vulnerability detection approaches in Android applications, highlighting key aspects such as dataset size, feature selection, and overall performance. While prior studies have achieved promising results, most of them relied on relatively small datasets, limited feature sets, or specific code metrics, potentially restricting their generalizability. In contrast, our study utilizes a significantly larger dataset comprising 426,246 code snippets with an equal distribution of vulnerable and non-vulnerable samples. Furthermore, our approach, employing SVM and Logistic Regression classifiers, outperforms previous methods, achieving a detection accuracy of 98.71%. These results highlight the effectiveness of our methodology in identifying vulnerabilities with higher precision and recall, demonstrating its robustness across a broader and more diverse dataset.

Table 5.

Comparison of machine learning-based vulnerability detection approaches in Android applications.

5. Results and Discussion

The constructed dataset provides a comprehensive resource for analyzing Android application source code vulnerabilities. The systematic approach to identifying vulnerability-fixing commits across 366,231 repositories out of 2.9 million repositories successfully yielded a collection of real-world vulnerable code snippets. These snippets, derived from actual developer fixes, offer unique insights into patterns of security flaws and remediation strategies.

The dataset comprises 20,004 unique vulnerability-fixing commits, comprising 426,246 code snippets, each labeled with metadata such as the associated CVE identifier (when available) and repository information. It also adds the commits that fix the vulnerability, considering each commit contains a vulnerability and its patches. Preliminary experiments using this dataset to train machine learning models for vulnerability detection show promising results. Early iterations of these models achieved a detection accuracy of 98.71% for known vulnerability patterns, indicating the dataset’s potential to enhance automated security assessments.

Our findings underline the value of using real-world data to fill gaps in detecting vulnerabilities in Android apps. This dataset, unlike artificial ones, reflects real practices and provides a great foundation for training machine learning models.

However, there are some limitations. Relying on commit messages and specific keywords might overlook some vulnerabilities, especially in repositories with unconventional or minimal documentation. Public repositories also dominate the dataset, potentially leaving out vulnerabilities in private projects, which may be more sensitive or critical. Additionally, deeper semantic analysis, such as inter-procedural dependencies or taint analysis, could enhance the model’s ability to detect complex vulnerabilities.

This work shows that real-world, practice-based research datasets can be extremely valuable. It also demonstrates the importance of refining and expanding these datasets to improve the machine-learning models used for Android security. Future studies can use the dataset to explore alternative feature representations, deep learning models, or hybrid approaches combining static and dynamic analysis. The dataset can also be extended with additional real-world security patches to improve generalizability. We encourage researchers to apply and refine our methodology, contributing to the advancement of automated vulnerability detection in software security.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.E.A. and E.N.Y.; methodology, K.E.A.; software, K.E.A.; validation, formal analysis, investigation, resources, data curation, writing—original draft preparation, writing—review and editing, visualization, project administration, K.E.A. and E.N.Y.; supervision, E.N.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The APC was funded by Aselsan.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is publicly available at https://github.com/kemrec/AndroCom/ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

Kaya Emre ARIKAN is employed by Aselsan.

References

- Number of Monthly Android App Releases Worldwide 2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1020956/android-app-releases-worldwide/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Market Share of Mobile Operating Systems Worldwide from 2009–2024. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/272698/global-market-share-held-by-mobile-operating-systems-since-2009/ (accessed on 8 September 2024).

- Muhammad, Z.; Anwar, Z.; Javed, A.R.; Saleem, B.; Abbas, S.; Gadekallu, T.R. Smartphone Security and Privacy: A Survey on APTs, Sensor-Based Attacks, Side-Channel Attacks, Google Play Attacks, and Defenses. Technologies 2023, 11, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangari, G.; Ikram, M.; Sentana, I.W.B.; Ijaz, K.; Kaafar, M.A.; Berkovsky, S. Analyzing security issues of android mobile health and medical applications. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2021, 28, 2074–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harer, J.A.; Kim, L.; Russell, R.L.; Ozdemir, O. Automated software vulnerability detection with machine learning. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1803.04497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, G.; Meng, L.; Wang, H.; Ren, S.; Wang, Q.; Yang, L. A Comparative Study of Neural Network Techniques for Automatic Software Vulnerability Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Symposium on Theoretical Aspects of Software Engineering (TASE), Hangzhou, China, 11–13 December 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupsch, J.A.; Mill, B.P. Manual vs. Automated Vulnerability Assessment: A Case Study; Computer Sciences Department, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, Z.; Alowain, L.; Chen, X.; Wagner, D. DiverseVul: A New Vulnerable Source Code Dataset for Deep Learning Based Vulnerability Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.00409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawat, S.; Saxena, A. Application security code analysis: A step towards software assurance. Int. J. Inf. Comput. Secur. 2009, 3, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Chen, S.; Fan, L.; Feng, R.; Liu, H.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Y. Comparison and Evaluation on Static Application Security Testing (SAST) Tools for Java. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, ESEC/FSE 2023, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–9 December 2023; pp. 921–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joh, H.; Lee, J. Modeling Vulnerability Discovery Process in Major Cryptocurrencies. J. Multimed. Inf. Syst. 2022, 9, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GitHub on BigQuery: Analyze All the Open Source Code, Google Cloud Blog. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/blog/topics/public-datasets/github-on-bigquery-analyze-all-the-open-source-code (accessed on 14 September 2024).

- Chakraborty, S.; Krishna, R.; Ding, Y.; Ray, B. Deep Learning based Vulnerability Detection: Are We There Yet? arXiv 2020, arXiv:2009.07235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, J.; Kalutarage, H.; Petrovski, A.; Piras, L.; Al-Kadri, M.O. Defendroid: Real-time Android code vulnerability detection via blockchain federated neural network with XAI. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2024, 82, 103741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Wang, L.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H. Towards predictive analysis of android vulnerability using statistical codes and machine learning for IoT applications. Comput. Commun. 2020, 155, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Pradhan, P.; Partho, A.; Williams, L. Predicting Android Application Security and Privacy Risk with Static Code Metrics. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE/ACM 4th International Conference on Mobile Software Engineering and Systems (MOBILESoft), Buenos Aires, Argentina, 22–23 May 2017; pp. 149–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Thung, F.; Lo, D.; Sun, C.; Deng, R.H. VuRLE: Automatic Vulnerability Detection and Repair by Learning from Examples. In Computer Security–ESORICS 2017; Foley, S.N., Gollmann, D., Snekkenes, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2017; pp. 229–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajrani, J.; Tripathi, M.; Laxmi, V.; Somani, G.; Zemmari, A.; Gaur, M.S. Vulvet: Vetting of Vulnerabilities in Android Apps to Thwart Exploitation. Digit. Threat. Res. Pract. 2020, 1, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, Z.; Ersoy, M.A.; Soykan, E.U.; Tomur, E.; Çomak, P.; Karaçay, L. Vulnerability Prediction From Source Code Using Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 150672–150684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, L.; Zhimin, G.; Cen, C. Research on Android Intent Security Detection Based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2017 4th International Conference on Information Science and Control Engineering (ICISCE), Changsha, China, 21–23 July 2017; pp. 569–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pang, Y.; Xue, X.; Wang, H. Predicting Vulnerable Software Components through Deep Neural Network. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Deep Learning Technologies, ICDLT’17, Chengdu, China, 2–4 June 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Suri, B.; Kumar, V.; Jain, P. Extracting rules for vulnerabilities detection with static metrics using machine learning. Int. J. Syst. Assur. Eng. Manag. 2021, 12, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazuera-Rozo, A.; Escobar-Velásquez, C.; Espitia-Acero, J.; Vega-Guzmán, D.; Trubiani, C.; Linares-Vásquez, M.; Bavota, G. Taxonomy of security weaknesses in Java and Kotlin Android apps. J. Syst. Softw. 2022, 187, 111233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Sharma, A. Automated identification of security issues from commit messages and bug reports. In Proceedings of the 2017 11th Joint Meeting on Foundations of Software Engineering, ESEC/FSE, Paderborn, Germany, 4–8 September 2017; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 914–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perl, H.; Arp, D.; Fahl, S. VCCFinder: Finding Potential Vulnerabilities in Open-Source Projects to Assist Code Audits. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Denver, CO, USA, 12–16 October 2015; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 426–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feichtner, J.; Gruber, S. Code Between the Lines: Semantic Analysis of Android Applications. In ICT Systems Security and Privacy Protection; Hölbl, M., Rannenberg, K., Welzer, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2020; pp. 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challande, A.; David, R.; Renault, G. Building a Commit-level Dataset of Real-world Vulnerabilities. In Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM Conference on Data and Application Security and Privacy, CODASPY ’22, Baltimore, MD, USA, 24–27 April 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, J.; Kalutarage, H.; Al-Kadri, M.O.; Piras, L.; Petrovski, A. Labelled Vulnerability Dataset on Android Source Code (LVDAndro) to Develop AI-Based Code Vulnerability Detection Models. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Security and Cryptography, Kunming, China, 14–16 December 2024; pp. 659–666. Available online: https://www.scitepress.org/Link.aspx?doi=10.5220/0012060400003555 (accessed on 19 September 2024).

- Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, K.; Ding, X.; Wang, X. AdvAndMal: Adversarial Training for Android Malware Detection and Family Classification. Symmetry 2021, 13, 1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bala, N.; Ahmar, A.; Li, W.; Tovar, F.; Battu, A.; Bambarkar, P. DroidEnemy: Battling adversarial example attacks for Android malware detection. Digit. Commun. Netw. 2022, 8, 1040–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renjith, G.; Laudanna, S.; Aji, S.; Visaggio, C.A.; Vinod, P. GAN based enGine for Modifying Android Malware. SoftwareX 2022, 18, 100977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, H.; Nikam, P.; Sahay, S.K.; Sewak, M. Identification of Adversarial Android Intents using Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Visual, 18–22 July 2021; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra-Manzanares, A. Machine Learning for Android Malware Detection: Mission Accomplished? A Comprehensive Review of Open Challenges and Future Perspectives. Comput. Secur. 2024, 138, 103654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y. Zhejiang University. Yajin’s Homepage. Available online: https://yajin.org (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- The Drebin Dataset. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20161029112333/https://www.sec.cs.tu-bs.de/~danarp/drebin/index.html (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Gómez, A.; Muñoz, A. Deep Learning-Based Attack Detection and Classification in Android Devices. Electronics 2023, 12, 3253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senanayake, J.; Kalutarage, H.; Al-Kadri, M.O.; Petrovski, A.; Piras, L. Android source code vulnerability detection: A systematic literature review. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CVSS v3.1 Specification Document. FIRST—Forum of Incident Response and Security Teams. Available online: https://www.first.org/cvss/v3.1/specification-document (accessed on 13 January 2025).

- NVD-Home. Available online: https://nvd.nist.gov/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Gabel, M.; Yang, J.; Yu, Y.; Goldszmidt, M.; Su, Z. Scalable and systematic detection of buggy inconsistencies in source code. In Proceedings of the ACM International Conference on Object Oriented Programming Systems Languages and Applications, OOPSLA ’10, Reno/Tahoe, NV, USA, 17–21 October 2010; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (PDF) Hidden Technical Debt in Machine Learning Systems. ResearchGate. October 2024. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/319769912_Hidden_Technical_Debt_in_Machine_Learning_Systems (accessed on 17 November 2024).

- Jebnoun, H.; Braiek, H.B.; Rahman, M.M.; Khomh, F. The Scent of Deep Learning Code: An Empirical Study. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Mining Software Repositories, MSR ’20, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 29–30 June 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 420–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google Colab. Available online: https://colab.research.google.com/ (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Bisong, E. Introduction to Scikit-learn. In Building Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models on Google Cloud Platform: A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners; Bisong, E., Ed.; Apress: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2019; pp. 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandas Documentation—Pandas 2.2.3 Documentation. Available online: https://pandas.pydata.org/docs/index.html (accessed on 8 February 2025).

- Krutz, D.E.; Mirakhorli, M.; Malachowsky, S.A.; Ruiz, A.; Peterson, J.; Filipski, A.; Smith, J. A Dataset of Open-Source Android Applications. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/ACM 12th Working Conference on Mining Software Repositories, Florence, Italy, 16–17 May 2015; pp. 522–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).