Abstract

It is shown in this paper that the appropriate preprocessing of input data may result in an important reduction of Artificial Neural Network (ANN) training time and simplification of its structure, while improving its performance. The ANN is working as a data predictor in a lossless image coder. Its adaptation is done for each coded pixel separately; no initial training using learning image sets is necessary. This means that there is no extra off-line time needed for initial ANN training, and there are no problems with network overfitting. There are two concepts covered in this paper: Replacement of image pixels by their differences diminishes data variability and increases ANN convergence (Concept 1); Preceding ANN by advanced predictors reduces ANN complexity (Concept 2). The obtained codecs are much faster than one without modifications, while their data compaction properties are clearly better. It outperforms the JPEG-LS codec by approximately 10%.

1. Introduction

The number of Artificial Neural Network (ANN) applications is growing steadily. Their introduction in the area of lossless image coding is restricted by the high cost of their training process. The domain is dominated by simple and very fast algorithms: JPEG-LS [1], JPEG 2000 [2], WebP [3], and even CALIC [4] belong to this group today. On the other hand, there is a set of computationally complex “classical” methods, and these, at the same time, set very high performance standards: TMWLEGO (2001) [5], WAVE-WLS (2002) [6], MRP 0.5 (2005) [7], its newest version being MRP-SSP [8] (2014), and finally, PMO [9,10,11] (2018, 2019, 2022) and EM-WLS [12] (2020) algorithms. First, codecs using ANNs were trained on samples from the coded image, and worked as backward predictors [13,14,15]. ANN-based coders had relatively high computational complexity, and despite this their performance was average; even for the best ones, their performance was worse than for classical techniques [16]. Codecs based on deep learning are more efficient [17,18,19,20], but their relatively fast operation is possible only when powerful GPU units are used [21,22,23]. Codecs are usually trained on sets of training images. An analysis of deep-learning methods’ advantages and drawbacks can be found in [17,23,24]; see also Section 2.2 of this paper. Its final conclusion remains the same: their computational complexity is very high, while performance is still not as good as that of the best “classic” approaches. The modern overview of ANN-based codecs for image compression can be found in [25].

In this paper, two concepts leading to an important reduction of ANNs’ computational complexity while improving their data estimation property are presented. The idea consists of preprocessing ANN input data, resulting in the reduction of ANN training time, and in the second case in the simplification of ANN structure; see Section 5. These are Adaptive Neural Networks (AdNNs), hence, they are not initially trained; adaptation is done using local pixels surrounding the coded one; see Section 3. The use of AdNNs instead of a deep-learning approach is commented on in Section 2.3. In Section 4, the outline of the whole coder is provided. The data compaction properties of new algorithms are better than those for other ANN-based lossless image coders; see Section 6, Tables 2 and 3. In Section 2.1, the general types of lossless image coding techniques are outlined. Section 2.3 presents the index notation used in the paper.

2. Scientific Background

2.1. Note on Lossless Image Coding Techniques

Modern lossless image coding methods usually consist of two stages: data preprocessing and entropy coding. Of course, preprocessed data are not quantized; the decoded image is identical to the original one. Preprocessing consists of linear or non-linear data prediction, before prediction error is calculated; see Section 2.3. Prediction errors tend to have the Laplace distribution, better prediction, stronger values concentration around zero, and potentially more efficient coding by some entropy method in the second stage.

There are two basic classes of method: forward prediction and backward prediction. In the case of forward prediction, predictor parameters are optimized with respect to the general properties of the image before its actual coding. The simplest techniques use either one or a small set of fixed predictors; their construction is based on the knowledge of what the typical properties of a pixel surrounding are. The optimization reduces to a decision regarding which predictor is the best for the approximation of the currently coded pixel, e.g., JPEG-LS [1] and CALIC [4] work in this way. In the case of more advanced methods, coder parameters are optimized for the currently processed image. Information regarding the parameters is sent to the decoder in the message header. The coder efficiency grows with its complexity, and hence, with greater header size. As happens in general, we have here an effect of diminishing returns, and there is an obvious trade-off between header size and coder performance [5,7,26,27,28]. The techniques are time asymmetric; coding time is longer than the decoding time, sometimes much longer. In some situations, this is an advantage, as often an image is coded once and then decoded several times.

In the case of backward prediction, both coder and decoder work on already coded data; information needed for coding is also available for the decoder, and header information is not needed. The decoder repeats the coding process; hence, the methods are time symmetric. In this way, the coder complexity is not restricted; moreover, the predictor parameters can be optimized separately for each coded pixel. At the start of the coding (and decoding) process, only a few preceding pixels are known; hence, there is the problem of optimal coder initial settings. This is particularly important when the predictor operates on a particularly large number of pixels. Taking all this into consideration, there is a wide range of coders with respect to their complexity. There are simple coders, like CoBALP [29,30,31], medium complexity ones, like RLS [32] and OLS [12,33,34,35], and the most advanced ones, such as EM-WLS [12].

At first, Artificial-Neural-Network-based coders were backward prediction ones, AdNN [13,14,15], but there were also ones based on Cellular Neural Networks [36] or Fuzzy Neural Networks [37]. The deep-learning approaches are obviously forward prediction coders [17,23,38]. In contrast to “classical” advanced forward prediction methods, ANN settings are not optimized for the currently coded image, but for a set of exemplary ones, which have strongly reduced sizes: or pixels. Still, without hardware support, their learning process is very time-consuming, although run only once. There are also hybrid techniques; in [39], an ANN codes pixel estimates obtained using a lossy BPG coder. In [40], an image is divided into subimages, then the first subimage is coded using JPEG-XL, while a deep-learning-based technique codes the remaining ones (LC-FDNet).

2.2. AdNNs vs. Deep Learning Approach

Deep-learning algorithms for lossless image coding may have data compaction properties close to those for the best “classic” approaches, and better than for the codecs presented in this paper; however, this is not obtained without a cost. Firstly, efficient deep-learning codecs are extremely computationally complex [41]. On the other hand, they can be easily parallelized, and as a result their coding and decoding times heavily depend on the experimental equipment used. Let us consider a comparison of codec L3C [42] to codec [3]. It should be highlighted that the latter “classic” coder is implemented sequentially. In [43], the coding time of 512 × 512 pixel images for L3C is 1.5 to 3.33 times longer than for WebP, while the decoding time is 110 to 1614 times longer. In [42], the proportions are 1.5:1 and 5.25:1, respectively. In [44], the coding time for L3C is 12.8 times shorter than for WebP. Finally, ref. [45] provides full data for L3C: 0.49 s and 0.54 s for a 512 × 512 pixel image on NVIDIA GeForce RTX 2080 plus Intel i7-9700. Unfortunately, there are no data for WebP. Of course, such equipment cannot be found in laptops or smartphones.

In the paper, times for AdNNs are provided for a sequential processor, and there is no hidden time for off-line computations.

Secondly, deep-learning algorithms are trained on very small images, usually 32 × 32 or 64 × 64 pixel ones. As a result, deep-learning algorithms work the best for the smallest practical image sizes, i.e., 512 × 512 pixels; for larger images, their performance deteriorates [11]. Imperfect training sets may cause network overfitting, and this effect poses a question regarding the validity of the experimental results [11]. AdNNs are taught on the set of pixels from the neighborhood of the coded one, so such problems do not appear.

Thirdly, AdNNs have much smaller memory complexity than deep-learning algorithms. They contain only one hidden layer of size 12 (Concept 1) or size 7 (Concept 2); the coder needs only minimal “cache” to remember data for them; see Section 5. The deep-learning networks are much larger and may need memory for large sets of parameters.

2.3. Note on Pixel Index Notation

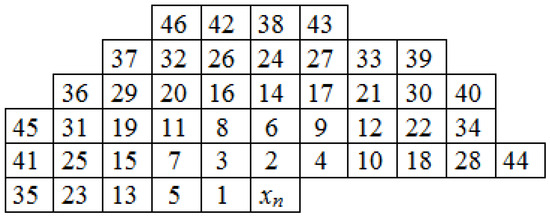

Figure 1 shows the sample indexing scheme used in this paper for the neighborhood of a coded pixel. The coded pixel is denoted by ; the others are . For example, for a linear predictor of rank r,

where represents the predictor coefficients, and are taken from the positions shown in Figure 1. When prolonging a predictor, the general rule is that the index value is obtained by taking into account the Euclidean distance, and clockwise ordering if samples have the same Euclidean distance from the sample of interest. Discussions on this and other indexing strategies can be found in [12]. Then, the prediction error is:

where prediction result is rounded up.

Figure 1.

Sample indexing in the neighborhood of coded pixels.

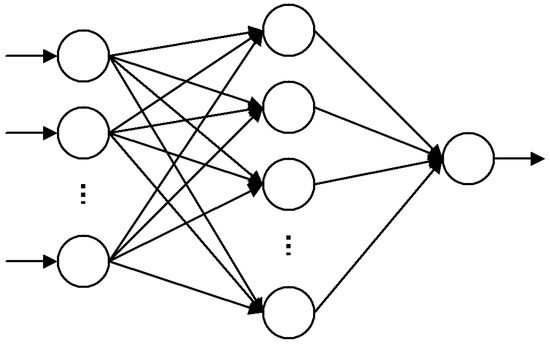

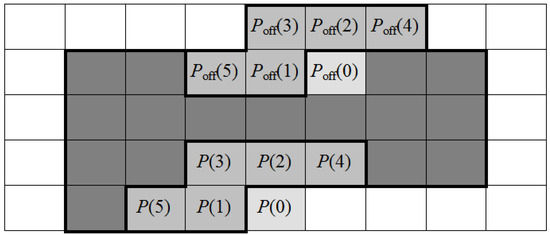

3. Implemented Artificial Neural Network

The Artificial Neural Network used, named the Adaptive Neural Network (AdNN) [13,14,15,16], is a rather basic one; see Figure 2. Its inputs are neighbor pixels , and signal 1 at the r-th position (hence, in Figure 3); the output is an estimator of coded pixel . The numbering of pixels is as in Figure 1; a single hidden layer contains nodes. The neural network learning set is defined by a training window; its shape for parameter is shown in Figure 3 (rectangle W pixels high and wide above plus W pixels to the left from ). estimation is improved in consecutive learning epochs; one epoch consists of learning the network for each position of in window Q; see Figure 3. Final network weights are used as initial ones for estimating the next image pixel. At the beginning, the AdNN is not trained; the initial network weights are randomly chosen from the range −0.5 to +0.5 and are the same in both the coder and the decoder. The suggested numbers of epochs, , are 20 [13] or 25 [14,15,16].

Figure 2.

Structure of adaptive neural network.

Figure 3.

Training window Q around pixel .

Neural network learning formulas are as follows: Output value of the i-th hidden layer neuron is calculated using a sigmoid function:

where is the weighted average value of outputs from input neurons (note that signal values inside AdNN have a range from −0.5 to +0.5):

and denotes the input weight of the i-th neuron from the hidden layer connected to the j-th input neuron (pixel ). The output neuron output is computed as follows:

where is the weighted mean of outputs from hidden layer neurons :

and denotes the i-th hidden layer neuron output weight. The neural network settings are corrected using the error of its output:

as well as errors of hidden layer signals:

Errors determine increments in the hidden layer input and output weights for each :

then the weights are corrected; the input and output ones are:

In [14], it is suggested to use in the first three epochs learning parameters and , then switch to and . At the end of the learning process, the value of the estimated pixel should be converted from the range −0.5 to +0.5 to the range 0 to 255.

4. The Coder Structure

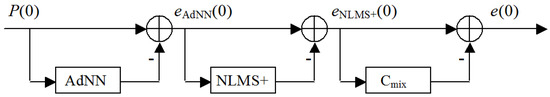

Many modern lossless coding algorithms have cascade organization; the main predictor (here, an AdNN) is followed by a single stage or by several stages of NLMS (Normalized Least Mean Square) filters; see Figure 4. Image pixels are coded independently row after row from the top down, and from left to right. Then, computed according to (2), AdNN errors are processed by NLMS stages, followed by the prediction bias cancellation procedure in the block; see Figure 4. The most advanced update formulas for NLMS coefficients used here, and for definition, can be found in [12]. Two NLMS sub-stages of rank and are implemented. This is the data modeling part of the coder; it is followed by an advanced adaptive context arithmetic coder, which is fully described in [12].

Figure 4.

Cascade data modeling part of a lossless image coder; compare, e.g., with [12].

The authors of the CALIC algorithm discovered that predictors tend to accumulate biases, which superimpose on their estimates. As a consequence, both CALIC and JPEG-LS include a stage of prediction bias cancellation. The cancellation procedure is a context one; the context is defined by the coded pixel neighborhood. For each context, the accumulated error is calculated and the prediction error corrected; see [1,4]. In [46], it was discovered that the single predictor bias cancellation formula can be unreliable. Following this observation, in our techniques the weighted sum of outputs from several bias canceling methods is computed: in Figure 4. The definition of the most advanced 12-element one can be found in [12].

The following algorithms describe the cascade coder and decoder operation, Algorithm 1 and Algorithm 2, respectively:

| Algorithm 1 Coder operation |

For each coded pixel :

|

| Algorithm 2 Decoder operation |

|

For each coded pixel prediction error : |

5. Preprocessing Data for AdNN

In previous papers, AdNN was used for processing image samples. The new idea consists of applying AdNN to initially transformed data. Two concepts are presented; in one case, AdNN is mainly fed with pixel differences, and in the other AdNN acts on outputs from the predictors used in classic lossless image coding methods. The concepts aim is to reduce the complexity of AdNN training, while retaining, or even improving, coder performance. The coding time of a -pixel image was over 10 min for AdNN+ [16]. The computer was an Intel i5-4670 (3.4 GHz, Windows 7, 8 GB RAM, SSD); C language programs were not optimized. Coding time depends solely on the number of pixels; it is independent of image contents. The techniques have very small memory complexities: for double precision computations, the number of memory bytes for hidden and output layer weights is . This makes B for Concept 1 and B for Concept 2, respectively.

5.1. Concept 1

Images are locally smooth; hence, differences between neighboring image pixels used to be small. It is proposed to replace the pixel values in Formulas (4) and (9) by pixel differences; Table 1 provides their definitions. Apart from values, the AdNN input for is , and for , outputs from “classical” predictors GBSW+ and GAP+; their definitions can be found in [47]. Inputs are normalized; normalization consists of transforming data value range into AdNN signal range . The last AdNN input is equal to −1.

Table 1.

Concept 1: AdNN inputs . For positions of pixels , see Figure 1.

In this way, the number of AdNN inputs, r, is reduced from 24 in AdNN+ [16] to 22; the number of hidden layer neurons is . However, a much more important improvement is the reduction of epoch numbers necessary for AdNN convergence from 25 to only 11. For the four epochs, and , then diminishes: = 0.07·(12 − epoch number), . Additionally, in the last three epochs window Q size diminishes from to 5, 4, and 3; see Figure 3. The coding and decoding times are now 259 s for an -pixel image, much less than for AdNN+ [16]. The computational burden for an epoch is 1020 weight adaptation for each pixel consisting of additions, multiplications, and divisions, and applications of function. The actual numbers are = 599,760 additions, = 881,280 multiplications, and = 13,260 other operations. It should be noted that the time cost of computations not linked with AdNN learning is negligible.

5.2. Concept 2

The very good effect of the supplementary application of low-cost predictors GBSW+ and GAP+ prompts another idea: the use of much more advanced ones. The predictors proposed for the AdNN preprocessing stage are ALCM+ [46], CoBALPultra [31], RLS [32], and LA-OLS [12]. The predictor formulae are linear (1); only their adaption algorithms on differ. Their joint time cost is around 12 s, much less than the 259 s for Concept 1. There are only five inputs to the AdNN; four are normalized outputs from the predictors, and the fifth is −1. The number of hidden layer neurons is also reduced to . The number of learning epochs and the size of window Q are the same as in Concept 1. During the first four epochs, and , and it then diminishes to = 0.05·(12 − epoch number), . The time needed for the coding of a -pixel image is 101.15 s. The formulae for the numbers of operations for each pixel are the same as for Concept 1, which results in = 107,100 additions, = 149,940 multiplications, and divisions, and applications of the function.

6. Experiments

The performance of the new algorithms is compared to that of some other methods. Table 2 shows the advances in AdNN performance caused by the new concepts; additionally, data for two popular fast codecs are presented, JPEG-LS and CALIC [48]. The list of images form a widely used benchmark for the comparison of lossless image coders [49]; see Figure 5. The new AdNN versions are better, while less computationally complex than the previous ones (see Section 5) and outperform JPEG-LS by approximately 10%. The AdNN codec is clearly better for images with a high variance of pixel values (e.g., noisesquare), while for artificially generated ones the difference is smaller (shapes). Data for another simple and popular codec, WebP, can be found in Table 3; its performance and complexity are of the same rank as JPEG-LS. Table 3 presents a comparison of the new AdNN algorithms with up-to-date ANN-based codecs; the table is an extension of the appropriate table from [17]. Note that the LCIC, L3C, CWPLIC, and LCIC duplex are deep-learning ANN algorithms. As can be seen, there is only one image (Comic) for which a pair of codecs considered in [17] outperform the new algorithms (CWPLIC, LCIC duplex). As a result, the mean performance of the new codecs is the highest. When realized on CPU, the Concept 2 codec is faster; however, as over 99% of Concept 1’s complexity is linked with AdNN on-line training, advances in the implementation of ANNs may revert this relation.

Figure 5.

Some images used in the experiments: coastguard, noisesquare, monarch, ppt3, zebra, flowers, pepper, mandrill, shapes.

Table 2.

Average bit per pixel rates for the first group of standard test images; C1, C2: Concept 1 and Concept 2.

Table 2.

Average bit per pixel rates for the first group of standard test images; C1, C2: Concept 1 and Concept 2.

| Images | JPEG-LS [1] | CALIC [4] | TS-FNN [37] | AdNN [14] | AdNN+ [16] | C1 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Camera | 4.31 | 4.190 | 4.39 | 4.13 | 4.120 | 4.007 | 3.999 |

| Couple256 | 3.70 | 3.609 | 3.73 | 3.60 | 3.561 | 3.435 | 3.441 |

| Noisesquare | 5.68 | 5.443 | 5.44 | 5.18 | 5.201 | 5.166 | 5.135 |

| Airplane | 3.82 | 3.743 | 3.68 | 4.06 | 3.598 | 3.557 | 3.558 |

| Baboon | 6.04 | 5.875 | 5.97 | 5.77 | 5.706 | 5.662 | 5.641 |

| Lennagrey | 4.24 | 4.102 | 4.08 | 3.97 | 3.925 | 3.899 | 3.890 |

| Peppers | 4.51 | 4.421 | 4.33 | 4.27 | 4.201 | 4.153 | 4.146 |

| Shapes | 1.21 | 1.139 | 1.79 | 1.44 | 1.708 | 1.111 | 1.124 |

| Balloon | 2.90 | 2.825 | 2.54 | 2.80 | 2.647 | 2.602 | 2.577 |

| Barb | 4.69 | 4.413 | 4.49 | 4.16 | 3.868 | 3.843 | 3.821 |

| Gold Hill | 4.48 | 4.394 | 4.36 | 4.33 | 4.238 | 4.196 | 4.192 |

| Mean | 4.144 | 4.014 | 4.073 | 3.974 | 3.888 | 3.785 | 3.775 |

Table 3.

Average bit per pixel rates for the second group of standard test images; C1, C2: Concept 1 and Concept 2.

Table 3.

Average bit per pixel rates for the second group of standard test images; C1, C2: Concept 1 and Concept 2.

| Images | LCIC | JPEG 2000 | JPEG-LS | JPEG-XL | FLIF | WebP | L3C | CWP LIC | LCIC Duplex | C1 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airplane | 3.99 | 4.00 | 3.80 | 3.71 | 3.82 | 3.87 | 4.56 | 3.69 | 3.69 | 3.533 | 3.532 |

| Barbara | 4.61 | 4.61 | 4.70 | 4.40 | 4.56 | 4.55 | 5.44 | 4.35 | 4.36 | 3.850 | 3.828 |

| Coastguard | 4.82 | 4.83 | 4.86 | 4.73 | 4.93 | 4.81 | 5.82 | 4.80 | 4.83 | 4.351 | 4.368 |

| Comic | 5.63 | 5.65 | 5.30 | 5.07 | 5.50 | 5.45 | 6.60 | 4.83 | 4.83 | 4.861 | 4.873 |

| Flowers | 4.91 | 4.92 | 4.62 | 4.51 | 4.74 | 4.76 | 5.53 | 4.41 | 4.35 | 4.318 | 4.327 |

| Goldhill | 4.58 | 4.59 | 4.43 | 4.37 | 4.50 | 4.47 | 5.27 | 4.33 | 4.33 | 4.143 | 4.143 |

| Lennagrey | 4.31 | 4.31 | 4.24 | 4.16 | 4.28 | 4.14 | 4.95 | 4.13 | 4.08 | 3.899 | 3.890 |

| Mandrill | 6.11 | 6.11 | 6.04 | 5.98 | 6.14 | 5.89 | 6.97 | 5.95 | 5.89 | 5.663 | 5.643 |

| Monarch | 3.82 | 3.82 | 3.70 | 3.54 | 3.68 | 3.73 | 4.37 | 3.40 | 3.45 | 3.368 | 3.342 |

| Pepper | 4.63 | 4.63 | 4.51 | 4.48 | 4.58 | 4.50 | 5.38 | 4.67 | 4.38 | 4.146 | 4.140 |

| Ppt3 | 2.41 | 2.41 | 2.04 | 1.84 | 1.87 | 2.06 | 3.71 | 2.14 | 2.07 | 1.770 | 1.775 |

| Zebra | 4.89 | 4.89 | 4.81 | 4.66 | 4.84 | 4.86 | 6.08 | 4.65 | 4.68 | 4.347 | 4.339 |

| Mean | 4.559 | 4.564 | 4.421 | 4.288 | 4.453 | 4.424 | 5.390 | 4.279 | 4.245 | 4.021 | 4.017 |

7. Conclusions

In this paper, an AdNN-based lossless image coding technique that is less computationally complex and more efficient than other ANN-based methods is presented. Additionally, it does not require initial learning on exemplary images, which is necessary for some newer approaches. The improvement is obtained by introducing preprocessing stage preceding AdNN input. Two concepts of initial processing are shown: in one, pixels are replaced mainly by pixel differences, which results in the shortening of the adaptation process; in the other, the ANN is preceded by four “classic” predictors, which means that there are only five ANN input nodes. The results are verified for a set of widely used benchmark images and, as can be seen, it outperforms the JPEG-LS codec by approximately 10%. The coding time for JPEG-LS is three orders of magnitude shorter than for the methods described in the paper.

The four “classic” predictors in Concept 2 have relatively low computational complexity, but they are not the most efficient ones. The more advanced ones, such as EM-WLS [12], are significantly more complex, but their use in the preprocessing stage may result in much better AdNN performance. Another interesting question is if the preprocessing of data can improve the properties of deep-learning algorithms. These topics need further study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.U.; methodology, G.U.; software, G.U.; validation, G.U. and R.S.; formal analysis, G.U. and R.S.; investigation, G.U. and R.S.; resources, G.U.; data curation, G.U.; writing—original draft preparation, G.U. and R.S.; writing—review and editing, G.U. and R.S.; visualization, G.U. and R.S.; supervision, G.U.; project administration, G.U.; funding acquisition, G.U. and R.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education under the status activity task 0314/SBAD/0241.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Weinberger, M.; Seroussi, G.; Sapiro, G. The LOCO-I lossless image compression algorithm: Principles and standardization into JPEG-LS. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2000, 9, 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcellin, M.; Gormish, M.; Bilgin, A.; Boliek, M. An overview of JPEG-2000. In Proceedings of the Proceedings DCC 2000. Data Compression Conference, Snowbird, UT, USA, 28–30 March 2000; pp. 523–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codec WebP 1.3. Available online: https://storage.googleapis.com/downloads.webmproject.org/releases/webp/libwebp-1.3.0-windows-x64.zip (accessed on 8 April 2023).

- Wu, X.; Memon, N. CALIC—A Context Based Adaptive Lossless Image Codec. In Proceedings of the 1996 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing Conference Proceedings, Atlanta, GA, USA, 9 May 1996; Volume 4, pp. 1890–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, B.; Tischer, P. TMWLego—An Object Oriented Image Modeling Framework. In Proceedings of the Data Compression Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 27–29 March 2001; p. 504. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, H.; Deng, G.; Devlin, J. A weighted least squares method for adaptive prediction in lossless image compression. In Proceedings of the Picture Coding Symposium PCS’03, Saint Malo, France, 23–25 April 2003; pp. 489–493. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, I.; Ozaki, N.; Umezu, Y.; Itoh, S. Lossless coding using Variable Blok-Size adaptive prediction optimized for each image. In Proceedings of the 13th European Signal Processing Conference EUSIPCO-05 CD, Antalya, Turkey, 4–8 September 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, W.; Xiong, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Y. Large Discriminative Structured Set Prediction Modeling with Max-Margin Markov Network for Lossless Image Coding. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2014, 23, 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuda, I.; Ozaki, N.; Umezu, Y.; Itoh, S. A Lossless Image Coding Method Based on Probability Model Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2018 26th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), Rome, Italy, 3–7 September 2018; pp. 156–160. [Google Scholar]

- Unno, K.; Kameda, Y.; Matsuda, I.; Itoh, S.; Naito, S. Lossless Image Coding Exploiting Local and Non-local Information via Probability Model Optimization. In Proceedings of the 27th European Signal Processing Conference (EUSIPCO), A Coruna, Spain, 2–6 September 2019; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, H.; Kita, Y.; Matsuda, I.; Itoh, S.; Kameda, Y.; Unno, K.; Kawamura, K. Improved Probability Modeling for Lossless Image Coding Using Example Search and Adaptive Prediction. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Advanced Imaging Technology (IWAIT) 2022, Hong Kong, China, 4–6 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ulacha, G.; Stasinski, R.; Wernik, C. Extended Multi WLS Method for Lossless Image Coding. Entropy 2020, 22, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kau, L.J.; Lin, Y.P.; Lin, C.T. Lossless image coding using adaptive, switching algorithm with automatic fuzzy context modelling. IEE Proc.-Vision Image Signal Process. 2006, 153, 684–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusic, S.; Deng, G. A neural network based adaptive non-linear lossless predictive coding technique. In Proceedings of the ISSPA ’99. Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Signal Processing and Its Applications (IEEE Cat. No.99EX359), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 22–25 August 1999; Volume 2, pp. 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marusic, S.; Deng, G. Adaptive prediction for lossless image compression. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2002, 17, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulacha, G.; Stasiński, R. Improving Neural Network Approach to Lossless Image Coding. In Proceedings of the 29th Picture Coding Symposium PCS’12, Krakow, Poland, 7–9 May 2012; pp. 173–176. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, H.; Jang, Y.I.; Kim, S.; Cho, N.I. Lossless Image Compression by Joint Prediction of Pixel and Context Using Duplex Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 86632–86645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S. Learned Lossless Image Compression Based on Bit Plane Slicing. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 27569–27578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, H.; Cho, N.I. Resolution-Adaptive Lossless Image Compression Using Frequency Decomposition Network. In Proceedings of the 2023 Asia Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Taipei, Taiwan, 31 October–3 November 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, X.; Gu, E.; Zhang, Y.; Li, A. Probability Prediction Network With Checkerboard Prior for Lossless Remote Sensing Image Compression. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 17971–17982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wu, G.; Swaminathan, V.; Wang, H.; Petrangeli, S.; Yu, T. GPU-accelerated Lossless Image Compression with Massive Parallelization. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), Laguna Hills, CA, USA, 11–13 December 2023; pp. 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, A.; Le, H.; Farhadzadeh, F. Bitstream Organization for Parallel Entropy Coding on Neural Network-based Video Codecs. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia (ISM), Laguna Hills, CA, USA, 11–13 December 2023; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, K.; Ji, X.; Wu, X.; Gao, W. Deep Lossy Plus Residual Coding for Lossless and Near-Lossless Image Compression. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2024, 46, 3577–3594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Kang, N.; Li, Z. Numerical Invertible Volume Preserving Flow for Efficient Lossless Compression. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, D.; Singh, S.K.; Singh, R.K. Deep Architectures for Image Compression: A Critical Review. Signal Process. 2022, 191, 108346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiazzi, B.; Baronti, S.; Alparone, L. Near-lossless image compression by relaxation-labeled prediction. Signal Process. 2002, 82, 1619–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golchin, F.; Paliwal, K.K. Classified adaptive prediction and entropy coding for lossless coding of images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Image Processing, Santa Barbara, CA, USA, 26–29 October 1997; pp. 110–113. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, B.; Tischer, P. TMW—A new method for lossless image compression. In Proceedings of the International Picture Coding Symposium (PCS 97), Berlin, Germany, 10–12 September 1997; pp. 533–538. [Google Scholar]

- Strutz, T. Context-based adaptive linear prediction for Lossless Image Coding. In Proceedings of the 4th International ITG Conference on Source and Channel Coding, Berlin, Germany, 28–30 January 2002; pp. 105–109. [Google Scholar]

- Strutz, T. Context-Based Predictor Blending for Lossless Colour Image Compression. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2016, 26, 687–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulacha, G.; Stasiński, R. New Context-Based Adaptive Linear Prediction Algorithm for Lossless Image Coding. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Signals and Electronic Systems (ICSES), Poznan, Poland, 11–13 September 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ulacha, G.; Stasinski, R. Context based lossless coder based on RLS predictor adaption scheme. In Proceedings of the 2009 16th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Cairo, Egypt, 7–10 November 2009; pp. 1917–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Barthel, E.; Zhang, W. Piecewise 2D autoregression for predictive image coding. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 1998 International Conference on Image Processing. ICIP98 (Cat. No.98CB36269), Chicago, IL, USA, 7 October 1998; Volume 3, pp. 901–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Deng, G.; Devlin, J. Adaptive linear prediction for lossless coding of greyscale images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 2000 International Conference on Image Processing (Cat. No.00CH37101), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–13 September 2000; Volume 1, pp. 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Deng, G.; Devlin, J. Least squares approach for lossless image coding. In Proceedings of the ISSPA ’99. Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on Signal Processing and Its Applications (IEEE Cat. No.99EX359), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 22–25 August 1999; Volume 1, pp. 63–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takizawa, K.; Takenouchi, S.; Aomori, H.; Otake, T.; Tanaka, M.; Matsuda, I.; Itoh, S. Lossless image coding by cellular neural networks with minimum coding rate learning. In Proceedings of the 2011 20th European Conference on Circuit Theory and Design (ECCTD), Brisbane, QLD, Australia, 10–15 June 2011; pp. 33–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.H.; Kau, L.J.; Lin, Y.P. A fuzzy neural network based adaptive predictor with P-controller compensation for lossless compression of images. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), Taipei, Taiwan, 24–27 May 2009; pp. 633–636. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Hamada, M.; Rahman, A. A comparative analysis of the state-of-the-art lossless image compression techniques. In Proceedings of the 4th ETLTC International Conference on ICT Integration in Technical Education (ETLTC2022), Aizuwakamatsu, Japan, 25–28 January 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, F.; van Gool, L.; Tschannen, M. Learning Better Lossless Compression Using Lossy Compression. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 6637–6646. [Google Scholar]

- Rhee, H.; Jang, Y.I.; Kim, S.; Cho, N.I. Learned Lossless Image Compression with Frequency Decomposition Network. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 6023–6032. [Google Scholar]

- Hoogeboom, E.; Peters, J.W.; van den Berg, R.; Welling, M. Integer Discrete Flows and Lossless Compression. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (2019), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer, F.; Agustsson, E.; Tschannen, M.; Timofte, R.; Gool, L.V. Practical Full Resolution Learned Lossless Image Compression. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Wu, C.-Y.; Krähenbühl, P. Lossless Image Compression through Super-Resolution. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.02872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.H.; Rhee, H.; Jang, Y.I.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.; Cho, N.I. Lossless Image Compression Based on Image Decomposition and Progressive Prediction Using Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 Asia-Pacific Signal and Information Processing Association Annual Summit and Conference (APSIPA ASC), Tokyo, Japan, 14–17 December 2021; pp. 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Gumus, S.; Kamisli, F. A Learned Pixel-by-Pixel Lossless Image Compression Method with 59K Parameters and Parallel Decoding. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.01185. [Google Scholar]

- Ulacha, G.; Stasiński, R. A Time-Effective Lossless Coder Based on Hierarchical Contexts and Adaptive Predictors. In Proceedings of the 14th IEEE Mediterranean Electrotechnical Conference MELECON’08, Ajaccio, France, 5–7 May 2008; pp. 829–834. [Google Scholar]

- Ulacha, G.; Łazoryszczak, M. Lossless Image Coding Using Non-MMSE Algorithms to Calculate Linear Prediction Coefficients. Entropy 2023, 25, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Jia, T.; Li, N.; Liu, X.; Jiang, J.; Lu, G. Review of Static Image Compression Algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 7th Advanced Information Technology, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IAEAC), Chongqing, China, 15–17 March 2024; pp. 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Test Images. Available online: https://kakit.zut.edu.pl/fileadmin/Test_Images.zip (accessed on 20 December 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).