Abstract

Production using modular architecture can not only shorten the product development cycle and improve the efficiency of product development, but also facilitate the upgrading of a product’s main functions and the recycling of materials. However, mechatronic products are plagued by various problems, such as greater difficulty in development and longer product development cycles due to their large numbers of parts with intricate internal relationships. However, the existing modular design method still faces problems when dealing with the modular design of mechatronic products. The structure of mechanical and electrical products is very complex, which is not conducive to the establishment of a model, and complex structural models lead to low efficiency and poor accuracy of module identification. Therefore, we propose an integrated module division method for mechatronic products based on core part hierarchical clustering and non-core part association analysis. Firstly, the core part screening method is used to simplify the structural model of mechatronic products and reduce the difficulty of modeling. Then, based on the core parts, the corresponding product design structural matrix (DSM) model is established. Secondly, the hierarchical clustering algorithm is used to obtain the module division scheme of different levels of mechatronic products, and the optimal modular scheme is obtained through an evaluation of modularity and a rationality analysis of module structure. Finally, based on the analysis of the association strength between the non-core parts and the existing modules, the non-core parts are classified into the corresponding product modules, and the final modularization scheme is obtained. A case study demonstrates the feasibility of the proposed method through the modular design of an electric bicycle.

1. Introduction

There are many types of mechatronic products used in daily life and industrial production which occupy a very important position in the national economy. With the increasingly fierce international competition and the gradual awakening of environmental protection awareness, the design of mechatronic products should not only meet the dynamic market demand, but also strive for better environmentally friendly attributes [1,2,3]. Current research suggests that the modular design concept can effectively balance the relationship between design elements, such as product development, market demand, product structure, and environmental protection [4,5]. The advantages of modular architecture include the following aspects: (1) product development costs can be effectively controlled; (2) the product development cycle can be shortened; and (3) the negative impacts of the product life cycle on the environment can be reduced. The primary feature of modular design is to distribute the functions of products into different modules to the greatest extent possible, while minimizing the association between modules and maximizing the association within modules [6]. Many products are currently developed using modular structures, such as smart phones, household appliances, new energy vehicles, industrial steam turbines [7], and wind turbines [8].

Product structure modeling and module identification are the basis of product modular design [9]. Common mechatronic products usually comprise mechanical systems, electrical systems, and hydraulic systems, with each system containing a certain number of parts. However, due to the large number of mechanical product parts and the intricate relationships between them, there are some important problems that must be urgently solved to modularize the mechatronic products. Firstly, how can we reduce the difficulty of modeling mechanical product structures while assuring the accuracy of structural models? Secondly, when the mechanical product structure is complex, how can we ensure the rationality of the product module division scheme? Motivated by these questions, we propose an integrated modular design methodology for mechatronic products based on core part hierarchical clustering and non-core part association analysis. In this paper, we describe how the difficulty of mechanical product modeling can be reduced by selecting the core parts of the product. At the same time, the credibility of the established product model is ensured. Then, the remaining product parts are divided into product modules using the correlation analysis method to guarantee the rationality of the product modularization scheme.

2. Related Work

2.1. Product Structure Modeling

Product structure modeling involves quantitatively analyzing the relationship between the parts after splitting the product and displaying them in an intuitive and concise way. Researchers have proposed various methods and tools to achieve this, such as the design structure matrix (DSM) [10], node-link diagrams [11], Petri nets [12], and other analytical tools [13].

For more than a decade, the DSM has been a widely used modeling framework across many areas of research because of its conciseness in representation and ease of analysis [14]. In Browning’s review, the DSM can be divided into four types according to different application objects: the component-based DSM, people-based DSM, activity-based DSM, and parameter-based DSM [15,16]. The use of the DSM to model products or system architectures can be traced back to the works of Simon and Alexander in the early 1960s, but it was not until 1981 that Steward formally proposed the concept of the DSM [17]. The product DSM is challenging to build because of the large amount of relevant professional knowledge required and the varied interpretations of a product’s structural relationships.

Product structure modeling usually needs to consider two factors. One is the decomposition granularity of the product, which determines the size of the product structure model. The second is the quantitative evaluation of the correlations among parts, which determines the complexity of the product structure model. For small products with a simple structure, the smallest particle size is often used to decompose them to the part level. For example, Han et al. completely decomposed a gear oil pump to the part level when establishing a DSM model of a gear oil pump; then, the community identification algorithm was used to realize the module division of the gear oil pump [18]. Li et al. realized the extraction of 3D model information through the secondary development of 3D modeling software, and established the DSM model based on the extracted product information [19]. For most mechatronic products, the complex product structure results in a huge number of parts. If product structure modeling is decomposed to the part level, the size of the established model will be huge, which is not conducive to the subsequent product module identification. Because of this, the relevant research literature began to focus on reducing the difficulty of modeling and improving the efficiency of modeling. Ma et al. proposed a method for selecting product parts according to the market value and established a structural model of a coffee machine using this method [20]. Wang et al. proposed a method of module division of complex products based on core parts, but the screening method of core parts in this paper is too cumbersome [6]. Li et al. proposed a pre-modular approach to the structural modeling of mechatronic products. This method divides a product into several small modules in advance, based on an analysis of the physical structure of the product; a structural model of the product is then built on the basis of these small modules [21]. Zhang et al. solved the problem of excessive parts by improving the granularity of product decomposition; they established a DSM model of a wind turbine using this method [8]. However, there is no specific principle that can be used to control the decomposition size of products in the literature, only relying on the design experience of engineers, so this method cannot be widely promoted. Some researchers proposed a method of building a product structure model based on product 3D model information extraction [22]. Such methods have great advantages in modeling efficiency and model data objectivity, but the limited product information that can be extracted cannot meet the modeling requirements of diversity.

Based on the above analysis, we can divide the mainstream methods used for the structural modeling of mechatronic products into two types. The first type is the pre-modular method; that is, an expert divides a product’s parts into several small modules based on their own knowledge and experience. Then, a structural model of electromechanical products is established on the basis of these small modules. The advantage of this method is that it is easy to implement, but the disadvantage is that the modeling results are easily affected by the subjective opinions of experts. The second type is the automatic modeling method. Generally, the basic information needed for product modeling is obtained by programming means, and then the product DSM model is built based on this information. The advantage of this method is its efficiency, but the disadvantage is that it relies heavily on the normativity of the product model, and the product information that can be extracted is limited.

Therefore, we selected the approach using the screening of core parts to establish a mechanical and electrical product structure model. Considering the ease of application of the core part screening method, we propose a method for determining core parts based on an assessment of the functional and structural importance of the parts. For the remaining non-core parts, correlation analysis is used to classify them into the existing product modules.

2.2. Module Partition Method

Module partition involves the identification of the module structure in a product by technical means, based on the product structure model. In the past two decades, module partitions based on function analysis [23], physical architecture [24], manufacturing [25], disassembling [26], and other aspects of the product life cycle have been proposed. Based on the various principles of the module partition algorithm, it can be divided into heuristic algorithm-based methods and cluster algorithm-based methods.

Modular methods driven by the heuristic algorithm usually establish the corresponding objective function according to different modular requirements and then use the appropriate heuristic algorithm to obtain the optimal modular solution. Guo and Sosale took the number of interfaces between product modules as the objective function of module division and then used the simulated annealing algorithm to obtain the optimal product modularization scheme [27]. To reduce the environmental impact of product recycling, Ji et al. established a comprehensive model based on a material reuse and technology system and used a bi-level optimization model based on a constraint genetic algorithm for the solution [28]. Zheng et al. solved a multi-objective optimization model based on minimizing maintenance costs and maximizing product modularity by using an improved-strength Pareto evolutionary algorithm 2 to obtain the optimal Pareto set of product modularity schemes [29]. Wang et al. established a comprehensive DSM structure model and used an improved genetic algorithm to obtain the optimal scheme for the modular design of a bicycle [22]. The modular method based on the clustering algorithm is to use quantitative tools to express the association between parts, and then realize the module division of products according to the intimate relationship between parts. Beek et al. established a DSM model of the shifting system of an equation car based on the function–behavior–state model, and then used the k-means clustering algorithm to obtain its modular scheme [9]. Yang et al. established a DSM model of a gear reducer based on function- and sustainability-related factors, and then determined the optimal module number and the final module division scheme using a genetic algorithm and a kernel-based fuzzy C-means algorithm [30]. On the basis of establishing the function–behavior-structure mapping model of 3D printer, Li et al. used the K-means clustering algorithm to realize the module division of the printer [31]. AlGeddawy and ElMaraghy obtained a clustering tree that reflected the internal structure of a product by using the hierarchical clustering algorithm; they then selected the optimal separation granularity to obtain the final modular results [32]. Li et al. used a modularization index based on product hierarchy clustering to obtain the optimal product modularization scheme and then demonstrated the feasibility of this method for a concrete-spraying machine product [33]. Li and Wei proposed an improved elbow evaluation method to analyze the results of product hierarchical clustering and applied it to the modular design of jaw crusher products [34].

Researchers have also put forward some other algorithms to realize module division. For example, the community identification algorithm in complex networks was introduced by Li and Zhang into the modular design of a product [8,35]. Zhang et al. proposed a multi-granularity module partition approach for complex mechanical products based on a complex network, and proved the effectiveness and superiority of the method through the module division of elevator products [36]. Liu et al. proposed a module partition method for complex products based on stable overlapping community detection and overlapping component allocation, and used this method to obtain a modularization scheme for CNC grinding machines [37]. The community recognition algorithm can effectively identify the community structure in complex networks, but the solution efficiency is generally low when dealing with products with complex structure and cannot show the hierarchy of the internal structure of products. In addition, Hossain et al. built a two-layer collaborative optimization model of modular product design and supply chain architecture and de-signed a nested bi-level particle swarm optimization algorithm (NBL-PSO) to solve the problem [38]. Also for the problem of module partition, Tian et al. took the maximization of green attributes and recycling attributes as the optimization goal and introduced an innovative social engineering optimizer (SEO) to solve the problem [39].

From the above analysis, it can be seen that the heuristic algorithm and the clustering algorithm remain the mainstream methods used in the modular design of products. The heuristic algorithm has problems such as a long solution time and unstable solution results when dealing with mechatronic products [6,8]. Therefore, considering the relatively complex structure of mechanical and electrical products, we used the hierarchical clustering algorithm to divide the modules and combined this with modular evaluation to obtain the optimal modular scheme.

3. Research Gaps and Challenges

Based on a review of the literature regarding the modular design of mechatronic products in recent years, we identified several knowledge gaps and challenges:

- The first is the structural modeling of mechatronic products. How can the complexity of the structural modeling of mechatronic products be reduced and the accuracy and rationality of the established model be ensured?

- The second is the acquisition of an optimal modularization scheme for mechatronic products. After obtaining the basic modular framework of mechatronic products based on the core parts, how do we deal with the module division of the remaining non-core parts?

4. Method

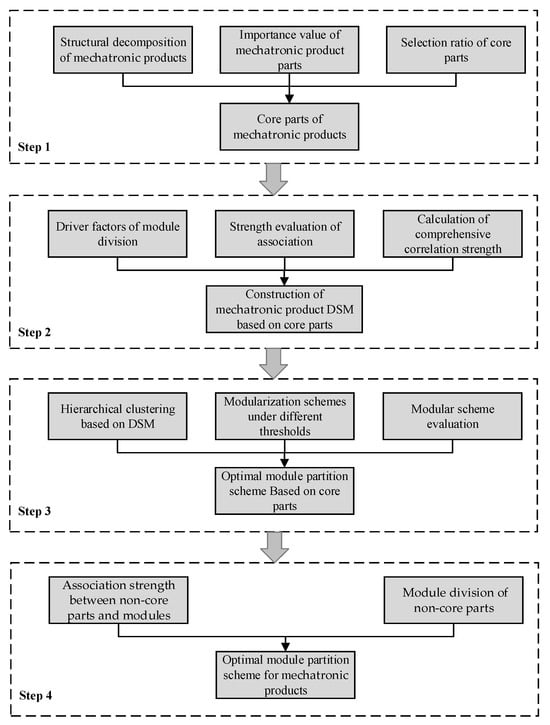

The research framework we used was divided into four steps, as shown in Figure 1. These were (1) mechatronic product core part screening based on expert scoring; (2) mechatronic product structure modeling with core parts; (3) mechatronic product module division by hierarchical clustering; and (4) non-core part module division based on association analysis.

Figure 1.

The research framework used in this study.

Step 1: Mechatronic product core part screening based on expert scoring. A number of product design engineers were selected to score the functional importance and structural importance of product parts. The product parts were sorted according to the weighted average of their importance, and the core parts of the product were selected by choosing a reasonable threshold.

Step 2: Establishment of a DSM model based on core parts. Based on the existing literature, the rules of different correlation strength values between core parts were determined. We then established a DSM model for mechatronic products.

Step 3: Mechatronic product module division by hierarchical clustering. We used the hierarchical clustering method because it can reveal the modular structure of products at different levels without specifying the number of modules.

Step 4: Non-core part module division based on association analysis. According to the strength of the relationship between the non-core parts and the existing modules of the product, the non-core parts were divided into the existing modules of the mechatronic product.

4.1. Mechatronic Product Core Parts Screening Based on Expert Scoring

A structural model of mechatronic products is difficult to establish, mainly due to the large number of product parts and the intricate interactions between them. To reduce the difficulty of the structural modeling of mechatronic products, some researchers have adopted the method of using pre-modular product parts. This requires product designers to have a high level of professional knowledge and inevitably involves some subjectivity, which may influence the results of complex product modularization. Therefore, we propose a means of screening the core parts of mechatronic products to reduce the complexity of product modeling to a reasonable level, while ensuring that the product model established can reflect the structural characteristics of the mechatronic product.

To ensure the rationality and credibility of the results of core parts screening, a given number of product design engineers were selected to score the functional and structural importance of product parts. The scoring criteria are shown in Table 1. After being scored by the engineers, the importance ranking of complex product parts was obtained by calculating the weighted average. The comprehensive importance of part i can be calculated as follows:

where Vi is the comprehensive importance value of product part I, k is the number of engineers participating in the scoring, w1 and w2 are function importance weight and structure importance weight, respectively, and Fij and Sij represent the functional importance and structural importance points assigned by engineer j to part I, respectively. After obtaining the ranking of product parts, we filtered the core parts by determining an appropriate threshold. For example, when the threshold value was 60, the comprehensive importance of the part was greater than 60, so it was considered to be a core part.

Table 1.

Scoring criteria for the importance of different parts.

4.2. DSM Model of Mechatronic Products Based on Core Parts

This section covers two steps. The first is to evaluate the correlation strength value between the core parts according to the evaluation criteria. The other is to obtain the comprehensive correlation strength value between the core parts through weighted summation and build the DSM model of the product.

4.2.1. Correlation Between the Core Parts

The calculation of the correlation between parts is the basis of the establishment of a complex product structure model. In the process of analyzing the correlation between parts, the multi-source correlation information (structure, function, flow, etc.) is taken into account to assess the strength of correlation between the parts. The multi-source correlation information is also considered by many researchers to be the module partition driver factors. Different module partition driver factors will generate different module structures. In the modular design process of mechatronic products, it is not only the influence of structure, function, and flows that should be considered, but also the influence of life span and recovery methods. Therefore, we present the key driver factors of module partition in this paper, which include structural correlation, functional correlation, flow correlation, life span correlation, and recovery method correlation.

- Structural correlation: The connection form and fitting type are the main factors determining the strength of the structural correlation between parts. The acquisition of these data relies mainly on engineers’ design knowledge and relevant engineering information.

- Functional correlation: The functions to be realized by mechatronic products are generally complex, so the total functions are often decomposed into simple sub-functions in the design process. It is beneficial for product design and subsequent function upgrading to categorize parts that have the same function into one module.

- Flow correlation: Flow correlation is analyzed by determining whether energy flow, material flow, or signal flow exists between parts. The flow correlation strength between assembled parts is also evaluated according to energy flow, material flow, and signal flow.

- Life span correlation: Mechatronic products usually comprise a large number of parts, while the service times and maintenance periods vary. Parts that have similar service times and maintenance periods can be grouped into the same module to reduce the use costs of a mechatronic product.

- Recovery method correlation: Increasingly serious environmental issues have led government agencies to focus more on the recycling of renewable resources. Mechatronic products have a large number of parts with high recycling values. However, the complexity of mechatronic product structures results in higher costs for recycling. Therefore, it is beneficial to reduce the recycling cost by grouping parts that can be recycled using the same method into the same module.

Based on this, the engineers can use these factors as an assessment index of correlations between product parts, and then estimate the correlation strengths between parts based on the corresponding evaluation criteria. The correlation strengths of linguistic variables can be divided into four levels: strong, medium, weak, and none; the corresponding interval values are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Standard interval values for different correlation strengths.

4.2.2. Construction of Weighted DSM Model

By analyzing the structural characteristics of mechatronic products, we can determine what kind of correlation exists between the core parts. The values of the corresponding correlation strengths are then obtained based on the standard values table. At this time, the weighted summation method is adopted to reflect the degree of influence of various modularization driving factors on the modularization plan, and the value of weight can be changed to meet variant modularization requirements. Among them, structure correlation, function correlation, flow correlation, life span correlation, and recovery method correlation are represented by c1, c2, c3, c4, and c5, and the corresponding weights are w1, w2, w3, w4, and w5, respectively. The comprehensive correlation strength between core parts m and n is obtained as follows.

By analyzing the structural characteristics of mechatronic products, the type of correlation that exists between the core parts can be determined. The values of the corresponding correlation strengths can then be obtained based on the standard values table. At this time, the weighted summation method is adopted to reflect the degree of influence of various modularization driving factors on the modularization plan, and the value of weighting can be changed to meet variant modularization requirements. Structure correlation, function correlation, flow correlation, life span correlation, and recovery method correlation are represented by c1, c2, c3, c4, and c5, respectively, and the corresponding weights are w1, w2, w3, w4, and w5, respectively. The comprehensive correlation strength between core parts m and n can be obtained from the following equation:

where pcl is the strength value of the l-th correlation between core parts, m and n, wl represents the weight of the l-th correlation relationship, and PCmn refers to the comprehensive correlation strength value between the core parts, m and n. The value of weight wl is generally determined using a mathematical weighting method after obtaining the opinions of experts via a questionnaire survey.

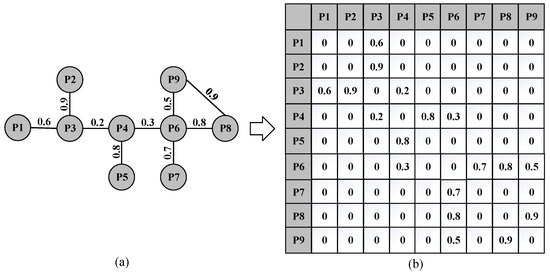

Based on the evaluation value of the comprehensive correlation strength between the mechatronic product parts, a DSM model of the mechatronic product can be constructed. Figure 2a shows the structural model of a virtual product, and the corresponding DSM model is shown in Figure 2b. In Figure 2b, the names of product parts correspond to the first row and the first column of cells of the DSM, while the values in the other cells represent the comprehensive correlation strength of the corresponding two parts.

Figure 2.

(a) A product structure model; (b) a product DSM model.

4.3. Module Division of Mechatronic Products Based on Hierarchical Clustering

The clustering algorithm is simple, efficient, and has good data adaptability, so it is widely used in product modularization. There are many types of clustering algorithms, including X-means, fuzzy C-means, and hierarchical clustering [19,40]. Of these, the hierarchical clustering algorithm can effectively display a product’s hierarchical structure under various module granularities; that is, it can provide modular solutions with different modular granularities. Therefore, in this study, we used hierarchical clustering to obtain the multi-level module structure of mechatronic products, and we used module degree evaluation to obtain the optimal modular scheme. The hierarchical clustering algorithm generally computes the tightness of the elements, merges nodes in turn according to the tightness value, and finally expresses the merging process in the form of a cluster tree. To reduce unnecessary programming work and to achieve the above hierarchical clustering algorithm, we used the “pdist”, “linkage”, and “dendrogram” functions in MATLAB software (2016a) to implement the clustering operation of DSM elements.

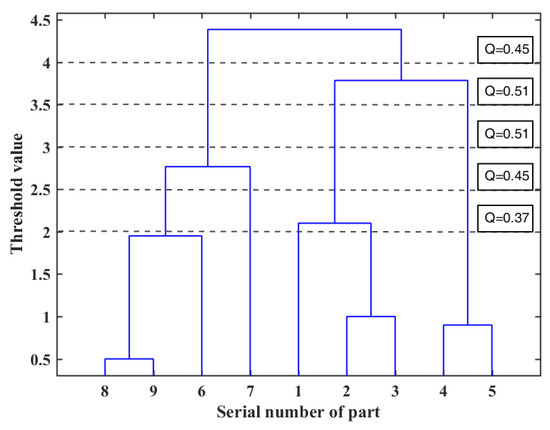

We used the DSM model of the virtual product shown in Figure 2 as an example to further explain the specific process of hierarchical clustering, and the final clustering result is shown in Figure 3. The coordinate value of the abscissa of Figure 3 expresses the nine parts of the virtual product, and the value of the ordinate refers to the distance between clustering parts. Nodes (parts) to be clustered are merged successively along the positive direction of the Y-axis according to the distance between them, and they finally intersect at a point to form an inverted Y-shaped tree structure. The corresponding module division scheme can be obtained by horizontally cutting the clustering tree with different thresholds. When the threshold value is 2, as shown by the gray horizontal dotted line in the figure, the entire product model is divided into five modules; as the threshold increases to 2.5, 3, 3.5, and 4, the number of modules in the product decreases to 4, 3, 3, and 2, respectively.

Figure 3.

Hierarchical clustering of the DSM model.

To help design engineers choose the optimal product modularization scheme, researchers have put forward a variety of indices to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages of modularization schemes. Among the many modularity indices, the modularity index Q, proposed by Newman et al., has been widely used in the solution and evaluation of product module division schemes due to its excellent module recognition ability and balanced module evaluation effect [41]. The calculation formula is as follows:

where eii represents the fraction of edges with both end vertices in the same module i, and ai represents the fraction of edges with at least one end vertex inside module i. k refers to the number of modules in the modular scheme. The modularity index Q is a real number of [−1, 1]; the larger the value, the more reasonable the module partition scheme, and vice versa. The calculation of the modularity index Q involves knowledge of complex network theory; however, given the limited space in this paper, we will not describe this in detail. For further details of the specific calculation method, please refer to the relevant literature [8,41]. As shown in Figure 3, when the threshold values are 3.5 and 4, the modularity index Q reaches the maximum value of 0.51, and the module division scheme obtained at this time is the optimal result.

4.4. Module Division of Non-Core Parts Based on Association Analysis

Based on the hierarchical clustering of core parts, a preliminary module division scheme of mechatronic products can be obtained. The following describes how to divide the remaining non-core parts into existing modules, to complete the final module division of mechatronic products. The module division process of non-core parts can be divided into two main parts: firstly, the correlation strength between non-core parts and modules is calculated; secondly, the module division of non-core parts is completed according to the strength of the relationship.

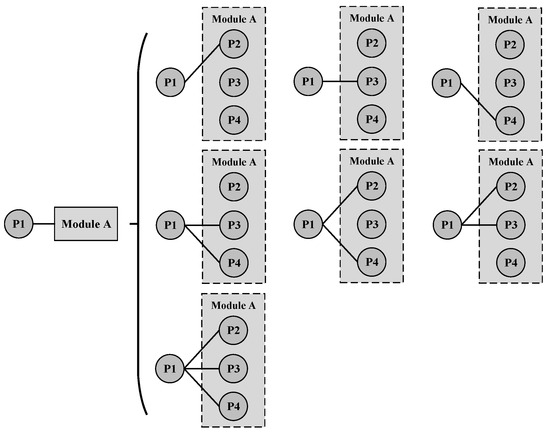

4.4.1. Analysis of the Association Strength Between Non-Core Parts and Modules

The correlation strength between the non-core parts and the existing modules of a product is the decisive factor in determining which module the non-core parts belong to. As modules generally contain multiple parts, the relationship between parts and modules is not as clear and easy to judge as the relationship between two parts. For example, suppose that part 1 and module A (including three parts, part 2, part 3, and part 4) have a structural association, and there are seven different situations in the structural association relationship between the two, as shown in Figure 4. This still does not take into account the changes in the strength of structural correlation.

Figure 4.

Complexity analysis of the association between non-parts and modules.

Through the analysis of the diversity and complexity of the relationship between parts and modules, we used the method of “taking the maximum” to assess the correlation strength between them. According to the evaluation standard of the correlation strength between the parts as outlined in Section 4.2, the correlation strength between the non-core parts and each core part in the module can be obtained. Then, the strength of the correlation between the non-core part and the module can be determined by taking the maximum. The formula is as follows:

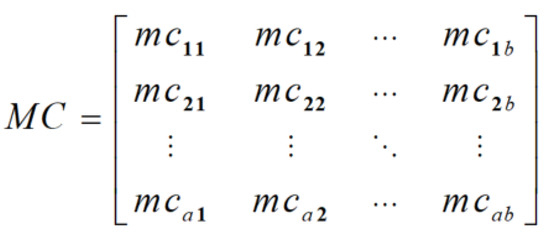

where MCxy is the comprehensive correlation strength between the non-core part x and the module y, wk refers to the weight of the k-th correlation relationship, mckz is the strength of the k-th correlation strength between the non-core part x and the core part z (belonging to module y), and u represents the total number of parts in module y.

4.4.2. Module Division of Non-Core Parts

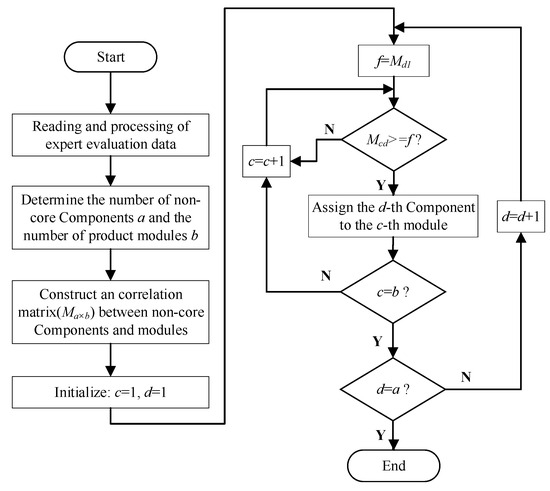

The strength of different types of correlation relationships between non-core parts and core parts of each module can be obtained by expert evaluation. The comprehensive correlation strength of non-core parts and modules is then calculated using Formula (3). The final comprehensive correlation matrix is shown in Figure 5. By comparing the strength of the relationship between the non-core parts and different modules of the product, the non-core parts can be divided into the corresponding modules with the strongest association relationship, ultimately completing the module division of the entire complex product.

Figure 5.

The correlation matrix between non-core parts and modules.

The quantity of data that must be processed during the process of module division of non-core parts is very large. Therefore, we compiled a module division program of non-core parts using MATLAB software (2016a) to reduce the workload of module division. Figure 6 shows a flow chart of the module division of non-core parts of mechatronic products.

Figure 6.

The module division process of non-core parts.

5. Case Study

We applied the proposed method to the modular design of a complex mechanical product family in a factory. The module partition of electric bicycle production was carried out to demonstrate the effectiveness of the approach proposed in this paper. The purpose of this was to improve customer satisfaction and product development efficiency while reducing enterprise production costs and the impact of product life cycles on the environment.

5.1. Core Parts Screening of an Electric Bicycle

An electric bicycle (shown in Figure 7) consists of approximately 100 main parts. Obviously, it is very difficult to establish the DSM structure model of the product based on these 100 main parts, so the size of the product DSM model can be reduced by screening the core parts. Five product engineers involved in the design of electric bicycles evaluated the functional importance and structural complexity of the parts according to the scoring standards shown in Table 1. Through the weighted sum of the scores given by the designers, the comprehensive importance values and ranking of electric bicycle parts were obtained, as shown in Table 3. When the threshold was 60, the top 28 parts were selected as the core parts of the electric bicycle.

Figure 7.

Illustration of the electric bicycle structure.

Table 3.

Importance value and ranking of electric bicycle parts.

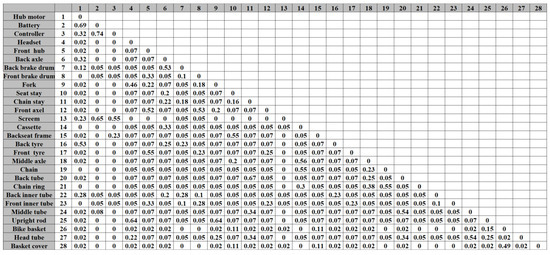

5.2. DSM Model of Electric Bicycles Based on Core Parts

After the selection threshold of the core parts was set to 60, 28 core components of electric bicycles were screened out, thus determining the size of the DSM specifications. Then, the values of the different correlation strengths between the core parts were evaluated based on the evaluation criteria shown in Table 2. Finally, based on the weights of five correlations, where structure correlation, function correlation, flow correlation, life span correlation, and recovery method correlation are 0.25, 0.3, 0.25, 0.1, and 0.1, the comprehensive correlation strength value was calculated, and the DSM model of an electric bicycle was obtained, as shown in Figure 8. In addition, the weights were obtained by a mathematical weighting calculation on the basis of the questionnaire survey conducted among five senior engineers in this professional field. The weight value is not fixed, and enterprises can adjust it according to the characteristics and design needs of their products. For example, if an enterprise wanted to reduce the environmental impact of product obsolescence, the weight of the recovery attribute could be increased.

Figure 8.

DSM model of an electric bicycle based on core parts.

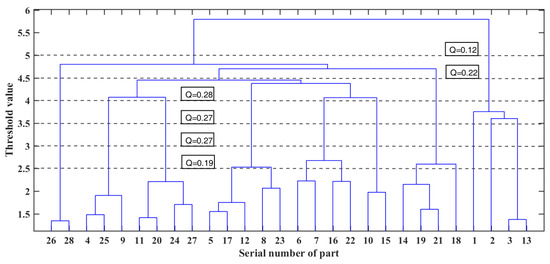

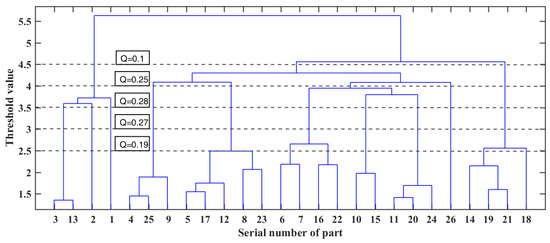

5.3. Hierarchical Clustering of Core Parts of an Electric Bicycle Based on a DSM Model

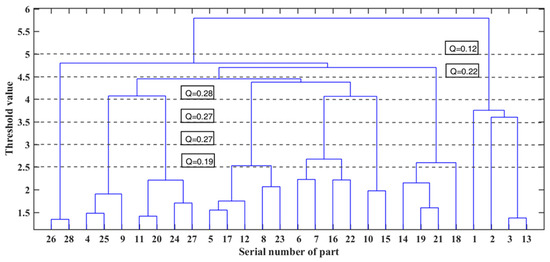

The tree diagram in Figure 9 shows the clustering results of the core components of the electric bicycle, where the horizontal coordinate is the serial number of the part and the vertical coordinate is the threshold value. To obtain a more useful module division scheme, the threshold values are 2.5, 3, 3.5, 4, and 4.5, and the corresponding modularity index Q value and module division scheme are shown in Figure 9 and Table 4, respectively.

Figure 9.

Hierarchical clustering of core parts of an electric bicycle.

Table 4.

Modularity results under different thresholds.

When the module partition scheme is evaluated according to the modularity index Q, the maximum value corresponding to the threshold value is 0.28 when the threshold value is 4. At this time, the electric bicycle is divided into seven modules, and the parts contained in each module are shown in Table 4. Only the core parts of the electric bicycle are considered in the hierarchical clustering, and the proportion of the core parts in the total number of parts is limited. Therefore, other factors should be referred to on the basis of the maximum modular index when selecting the optimal modular scheme. Among them, the number of modules and module structure, as two core contents of modular design, should be used as important references for selecting the optimal modular scheme. For example, when the total number of modules is small, the addition of non-core parts will cause the structure of some modules to be very large.

When only the modularity index Q is considered in the optimal modularity scheme, as shown in Figure 9, the maximum value of the modularity index Q is 0.28. At this time, the electric bicycle is divided into seven modules, with each module containing the parts information shown in Table 4. If the optimal number of modules of the product is calculated based on the total number of product parts in the relevant literature, the optimal number of modules of the electric bicycle should be 9 or 10. In Figure 9, when the threshold is 3 or 3.5, the corresponding number of modules is exactly 10. The corresponding modularity index Q here has a value of 0.27. Through the comparison of the two modular schemes, it can be seen that the modularity index Q of the two is just 0.01, and the difference between the two module division schemes is only in parts 1, 2, 3, and 13. After analyzing the results of module division, it seems unreasonable to divide parts 1 and 2 into two separate modules. However, it is necessary to consider that a large number of non-core parts will be added in the future. In addition, part 1 and part 2 are the hub motor and battery of the electric bicycle, respectively. Different models of electric bicycles also have different requirements for the power of the motor and the capacity of the battery. Therefore, dividing the motor and battery into separate modules is conducive to the development and upgrade of electric bicycles. Through the above analysis, the modularization scheme of 10 modules is regarded as the optimal solution for the modularization of electric bicycles. In the following work, non-core parts will be added to each module, and the final modular scheme of the electric bicycle will be obtained.

5.4. Module Division of Non-Core Parts of Electric Bicycles Based on Correlation Analysis

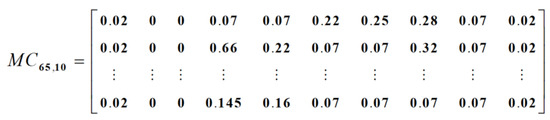

In light of the standards shown in Table 2, the strength of association between non-core parts and core parts in each module is evaluated in turn. Then, the association strength between non-core parts and modules is calculated according to Formula (4). To ensure the consistency of driving factors in the process of module division, the weights used in Section 5.2 are still used for the five types of association relationships. The correlation matrix established between non-core parts and modules is shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Correlation matrix between non-core parts and modules.

Based on the correlation matrix between non-core parts and modules, the module division procedure of non-core parts is executed to gain the final product modularization scheme. The final product modularization scheme for an electric bicycle is shown in Table 5. An electric bicycle is divided into 10 modules, with the largest number of parts for the front wheel module and the rear wheel module. Each module is composed of 13 parts. The modules with the lowest number of parts are the motor module and the basket module, with each module containing four parts. The modular scheme is very balanced, both in terms of the number of module parts and module structure. In particular, the motor module and battery module initially contain only one part, and the structure of the modules tends to be reasonable even with the addition of non-core parts.

Table 5.

The ultimate modular solution for electric bicycles.

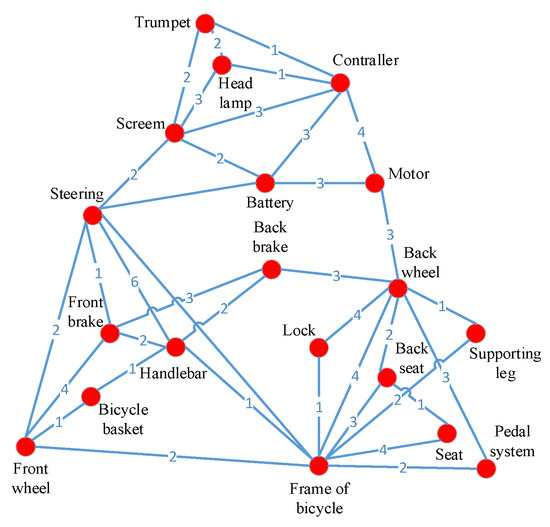

5.5. Compared with Community Detection Algorithm

The community identification algorithm of complex weighted networks is often used to divide complex product modules, and researchers who adopt this method use the pre-modular method to reduce the difficulty of complex product modeling. The complex weighted network model of an electric bicycle is shown in Figure 11, and the modularization scheme is obtained through the modified GN algorithm [42]. To facilitate this comparative study, the modular scheme with ten modules was selected as the optimal one, as shown in Table 6.

Figure 11.

Complex weighted network model of an electric bicycle.

Table 6.

Modular results of an electric bicycle based on modified GN algorithm.

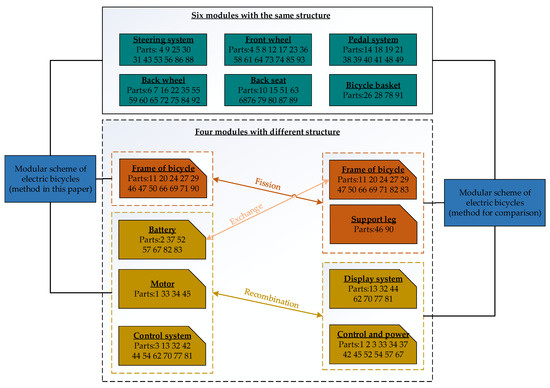

Among the ten modules, the structure of the steering system module, front wheel module, pedal system module, back wheel module, back seat module, and bicycle basket module is the same in the two modular schemes. The differences between the two modular schemes are shown in Figure 12, and the rationality of the modules is analyzed as follows:

Figure 12.

The differences between the two modular schemes.

- The community recognition algorithm divides the support leg module from the frame of the bicycle module, and the support leg module only contains two parts and is closely connected with the frame of the bicycle module. Therefore, it is unreasonable for the support leg to be a module alone.

- The community recognition algorithm reconstructs the motor module, battery module, and control system into two modules: the display system and the control and power system. However, with electric bicycle manufacturers, the motor and battery are usually purchased parts and have different types of customer requirements. It is conducive to product configuration and new product development to use them as separate modules.

- In the pre-modularization stage, the community identification algorithm categorizes the left guard plate and the right guard plate into the frame module, while the non-core parts association analysis method in this paper categorizes the left guard plate and the right guard plate into the battery module. The guard plate is close to the frame module in structure and has a strong functional correlation with the battery module, but it is a plastic product and is not compatible with the frame module in terms of material.

In general, the pre-modularization part of the community identification algorithm relies heavily on the subjective experience of engineers, resulting in the module division of some parts being unreasonable. In addition, the strength of the correlation between modules after pre-modularization is difficult to accurately assess. As for the algorithm itself, the efficiency of the hierarchical clustering algorithm is slightly better than that of the community recognition algorithm, especially when dealing with complex product models.

5.6. Sensitivity Analysis of Screening Threshold for Core Parts

The selection ratio of core parts is related to the difficulty of modeling and the rationality of the model. An appropriate screening ratio can effectively reduce the product modeling workload and improve the solution efficiency of modular schemes. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct sensitivity analysis on the selection ratio of core parts.

After we reduce the number of core parts from 28 to 26, the hierarchical clustering results of the electric bicycle are shown in Figure 13. When Q values are 2.7 and 2.8, we obtain two relatively good modularization schemes for the electric bicycle. The modular scheme with a Q value of 0.7 is consistent with the scheme structure adopted in this paper.

Figure 13.

Hierarchical clustering of core parts of an electric bicycle (26 core parts).

We continue to reduce the number of core parts from 26 to 24, and the hierarchical clustering results of electric bicycles are shown in Figure 14. When Q is 0.27 and 0.28, we obtain two better modularization schemes for e-bikes. However, it is a pity that these three schemes are different from the schemes adopted in this paper. When Q is 2.7, we obtain a result that is very close to the scheme adopted in this paper. The structure of nine of the modules is exactly the same, only one bicycle basket module is missing. The reason for this phenomenon is that in the process of reducing the number of core parts, the two parts ranked 28 and 26 in the bicycle basket module are successively excluded, which eventually leads to the disappearance of the bicycle basket module. Therefore, this also shows that too small a core part screening ratio may lead to the disappearance of some unimportant product modules.

Figure 14.

Hierarchical clustering of core parts of an electric bicycle (24 core parts).

6. Discussion

The difficulty of the module division of mechatronic products lies in the establishment of a product structure model, and the emphasis is on the rationality of the module division scheme. In this paper, we used the core parts selection method to reduce the difficulty of mechatronic product structure modeling, while hierarchical clustering and non-core part association analysis were used to ensure the rationality of module partition results.

Product pre-modularization is often used to reduce the difficulty of modeling mechatronic products; that is, the product components are divided into several sub-modules according to their function or structure. The advantage of this method is that it is relatively simple; however, it can be easily affected by the subjective opinions of product designers, and pre-modularity lacks a clear operating process. In contrast, the selection process of core components is very objective, even if it is affected by some subjective factors of the design engineer, but it can be mitigated or eliminated by weighted methods. In addition, we also tried to use the part information extracted from the three-dimensional assembly model of the product to automatically screen the core components, so as to improve the efficiency of the existing method and further reduce the influence of objective factors, but the experimental results need to be improved.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed an integrated module partition method to deal with the modularization of mechatronic products. Based on the multi-source relationship between core parts, the product structure model was established, and then hierarchical clustering and association analysis were used to complete the product module division. The specific research contributions are summarized as follows:

- The DSM was constructed to visually represent the physical structure of a complex product, including the core parts and the correlation strengths among them. This method effectively reduces the difficulty of complex product modeling and ensures the accuracy of the model.

- The hierarchical clustering algorithm was used to obtain the initial modular scheme of mechatronic products. Through association analysis, the non-core parts were divided into modules with the strongest comprehensive association relationships.

- We selected an electric bicycle as a case study to explain the methods described. The effectiveness of these methods in engineering applications was demonstrated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.W.; methodology, S.W.; software, G.-Y.Z.; validation, Y.-F.S. and G.-Y.Z.; formal analysis, S.W.; writing—review and editing, S.W. and Y.-F.S.; visualization, S.W.; supervision, S.W.; project administration, J.-X.M.; funding acquisition, J.-X.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research reported in this article was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (52305071) and the Xuzhou Science and Technology Program Project (KC23010).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the first author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Xuzhou University of Technology and China University of Mining and Technology for its support. The authors are sincerely grateful to the reviewers for their valuable review comments, which substantially improved the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gershenson, J.K.; Prasad, G.J.; Zhang, Y. Product modularity: Definitions and benefits. J. Eng. Des. 2003, 14, 295–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Li, B.; Peng, Q.; Gu, P. Product Specification Analysis for Modular Product Design Using Big Sales Data. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 36, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modrak, V.; Soltysova, Z. Influence of Manufacturing Process Modularity on Lead Time Performances and Complexity. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kremer, G.E.O.; Gupta, S. Analysis of modularity implementation methods from an assembly and variety viewpoints. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Tech. 2013, 66, 1959–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, X.; Wang, N.; Jiang, B.; Jia, T. Choosing Recovery Strategies for Waste Electronics: How Product Modularity Influences Cooperation and Competition. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Z.K.; He, C.; Liu, D.Z.; Zou, G.Y. Core components-oriented modularisation methodology for complex products. J. Eng. Des. 2022, 33, 691–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, B.; Qi, G.; Hu, X.; Yu, T. A network methodology for structure-oriented modular product platform planning. J. Intell. Manuf. 2015, 26, 553–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Yang, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Su, J. Module partition of complex mechanical products based on weighted complex networks. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 1973–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beek, T.; Erden, M.S.; Tomiyama, T. Modular design of mechatronic systems with function modeling. Mechatronics 2010, 20, 850–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Mirhosseini, M. A matrix-based modularization approach for supporting secure collaboration in parametric design. Comput. Ind. 2012, 63, 619–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelan, Y. Module partition method based on complex network theory. J. Graph. 2012, 33, 69–75. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, Z.; Feng, Y.; Li, Z.; Tian, G.; Tan, J. Reliability-based and cost-oriented product optimization integrating fuzzy reasoning Petri Nets, interval expert evaluation and cultural-based DMOPSO using crowding distance sorting. Appl. Sci. 2017, 7, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, H.C.; Gonzalez, M.A.; Yu, S. A multi-objective fuzzy graph approach for modular formulation considering end-of-life issues. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2008, 46, 4011–4033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Chen, T. Research on design structure matrix and its applications in product development and innovation: An overview. Int. J. Comput. Appl. Technol. 2010, 37, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, T.R. Design Structure Matrix Extensions and Innovations: A Survey and New Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2016, 63, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browning, T.R.; Eppinger, S.D. Modeling impacts of process architecture on cost and schedule risk in product development. Eng. Manag. IEEE Trans. 2000, 49, 428–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steward, D.V. The design structure system: A method for managing the design of complex systems. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 1981, EM-28, 71–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Mo, R.; Yang, H.; Hao, L. Module partition for mechanical CAD assembly model based on multi-source correlation information and community detection. J. Adv. Mech. Des. Syst. Manuf. 2018, 12, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.M.; Xie, S.Q. Module partition for 3D CAD assembly models: A hierarchical clustering method based on component dependencies. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 5224–5240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.F.; Kremer, G.E.O. A sustainable modular product design approach with key components and uncertain end-of-life strategy consideration. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 85, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chu, X.; Chu, D.; Liu, Q. An integrated module partition approach for complex products and systems based on weighted complex networks. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2014, 52, 4608–4622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, Z.; He, C.; Liu, D.; Zou, G. An Integrated Method for Modular Design Based on Auto-Generated Multi-Attribute DSM and Improved Genetic Algorithm. Symmetry 2022, 14, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreng, V.B.; Lee, T.P. QFD-based modular product design with linear integer programming—A case study. J. Eng. Des. 2004, 15, 261–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrani, A.K.; Gonzalez, R. A genetic algorithm-based solution methodology for modular design. J. Intell. Manuf. 2003, 14, 599–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandremenos, J.; Chryssolouris, G. A neural network approach for the development of modular product architectures. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2011, 24, 879–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Moon, S.K. Disassembly Complexity-Driven Module Identification for Additive Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 24th ISPE Inc. International Conference on Transdisciplinary Engineering, Singapore, 10–14 July 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, P.; Sosale, S. Product modularization for life cycle engineering. Robot. Comput.-Integr. Manuf. 1999, 15, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.J.; Jiao, R.J.; Chen, L.; Wu, C.L. Green modular design for material efficiency: A leader follower joint optimization model. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Feng, Y.X.; Tan, J.R.; Zhang, Z.X. An integrated modular design methodology based on maintenance performance consideration. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2017, 231, 313–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Feng, C.; Cheng, K. Sustainability-oriented product modular design using kernel-based fuzzy c-means clustering and genetic algorithm. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2012, 226, 1635–1647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Y.; Liu, Z.; Liu, Y.; Peng, N.; Wang, J.; Huang, Y.; Huang, Q. K-Means Module Division Method of FDM3D Printer-Based Function-Behavior-Structure Mapping. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 7453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlGeddawy, T.; ElMaraghy, H. Optimum granularity level of modular product design architecture. Cirp Ann.-Manuf. Technol. 2013, 62, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.k.; Wang, S.; Yin, W.w. Determining optimal granularity level of modular product with hierarchical clustering and modularity assessment. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2019, 41, 342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wei, W. Modular design for optimum granularity with auto-generated DSM and improved elbow assessment method. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2022, 236, 413–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, X.; Zou, F. Identification of influential function modules within complex products and systems based on weighted and directed complex networks. J. Intell. Manuf. 2019, 30, 2375–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.J.; Lu, B.T.; Xu, X.B.; Shen, X.F.; Feng, J.; Brunauer, G. CN-MgMP: A multi-granularity module partition approach for complex mechanical products based on complex network. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 17679–17692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.Y.; Zhong, P.C.; Liu, H.; Jia, W.Q.; Sa, G.; Tan, J.R. Module partition for complex products based on stable overlapping community detection and overlapping component allocation. Res. Eng. Des. 2024, 35, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Chakrabortty, R.K.; Elsawah, S.; Ryan, M.J. Hierarchical joint optimization of modular product family and supply chain architectures considering sustainability. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 43, 15–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, G.; Sheng, H.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Zhang, X.; Feng, Y. Enhancing end-of-life product recyclability through modular design and social engineering optimiser. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, C.S.; Kim, H.M.; Barker, D.E.; Zhang, Y. A ReliefF attribute weighting and X-means clustering methodology for top-down product family optimization. Eng. Optim. 2010, 42, 593–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, M.E.J.; Girvan, M. Finding and evaluating community structure in networks. Phys. Rev. E-Stat. Nonlinear Soft Matter Phys. 2004, 69, 026113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chu, X.; Xue, D. Function Module Partition for Complex Products and Systems Based on Weighted and Directed Complex Networks. J. Mech. Des. Trans. ASME 2017, 139, 021101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).