Abstract

Developing robust and reliable models for Named Entity Recognition (NER) in the Russian language presents significant challenges due to the linguistic complexity of Russian and the limited availability of suitable training datasets. This study introduces a semi-automated methodology for building a customized Russian dataset for NER specifically designed for literary purposes. The paper provides a detailed description of the methodology employed for collecting and proofreading the dataset, outlining the pipeline used for processing and annotating its contents. A comprehensive analysis highlights the dataset’s richness and diversity. Central to the proposed approach is the use of a voting system to facilitate the efficient elicitation of entities, enabling significant time and cost savings compared to traditional methods of constructing NER datasets. The voting system is described theoretically and mathematically to highlight its impact on enhancing the annotation process. The results of testing the voting system with various thresholds show its impact in increasing the overall precision by 28% compared to using only the state-of-the-art model for auto-annotating. The dataset is meticulously annotated and thoroughly proofread, ensuring its value as a high-quality resource for training and evaluating NER models. Empirical evaluations using multiple NER models underscore the dataset’s importance and its potential to enhance the robustness and reliability of NER models in the Russian language.

1. Introduction

One of the core tasks in Natural Language Processing (NLP) is Named Entity Recognition (NER), which is the process of recognizing and categorizing entities in text, including names of individuals, places, organizations, and other proper objects. NER systems are critical for many applications, including machine translation, question answering, keyword searching, and information retrieval [1,2,3].

Even while NER for languages like English has advanced significantly, creating reliable NER systems for other languages from the same language branch like, for example, German or Dutch (West Germanic) [4,5] and even for a language from a different language branch like Russian (Balto-Slavic branch) is still a difficult task [6]. In recent years, researchers have shown significant interest in NER, and many multilingual NER models now extract basic entities from multiple languages (including Russian) [7]. The other challenge is a creation of NER systems for other domains [4,8,9], especially NER systems for literature purposes or legal document analysis since they provide a vast amount of synonyms, polysemies, word forms, and other domain-specific techniques for expressing ideas [6,10]. General multilingual models struggle when dealing with any specific domain because they are trained on general texts extracted from the Internet like Wikipedia and cannot recognize domain-specific entities even for known entity types [3,4,5,8]. One of the major problems with these issues is the lack of domain-specific datasets as well as task-specific pre-trained models for languages [5]. This highlights the need to create a custom dataset focused on a specific domain, enabling the training and fine-tuning of NER models to achieve accurate results when extracting named entities from texts.

This study examines the development of an automated approach for generating a custom dataset to support named entity-recognition tasks. The literature heritage of Alexander Pushkin was chosen as a specific domain since it contains significant amount of specific examples of NER entities. The dataset is characterized by its focus on the following types of frequently encountered entities:

- Persons—The texts include numerous references to individuals, and the identification of these entities facilitates the reconstruction of Pushkin’s social network during the creation of his literary works.

- Locations—These entities encompass both real and fictional places. The recognition of real locations enables an analysis of the geographical context of Pushkin’s creative activities and correspondence, while fictional locations provide insights into the settings described in his literary compositions.

- Dates—Identifying dates in texts concerning Pushkin’s works contributes to the development of a chronology of his creative process, which is essential for enriching his biography.

- Organizations—Throughout his life, Pushkin interacted with numerous organizations, including educational institutions, publishing houses, censorship committees, and others. Recognizing mentions of these organizations in texts broadens our understanding of his life and creative journey.

- Works by A.S. Pushkin—Texts about Pushkin’s works often reference other literary compositions, both by Pushkin himself and by other authors. This category is particularly challenging to identify due to the frequent use of multiple and varying titles for the same work.

None of the mentioned entity types can be recognized by general models with enough precision and recall to process texts about works of A.S. Pushkin or other writers (Section 5). That means a lot of manual work editing results and datasets for custom model training.

Creating custom NER datasets is often hindered by significant barriers, particularly in terms of time and cost. Building high-quality NER requires accurate attention to every detail to identify the entities’ spans in a text and correctly label them. This is without accounting for the additional time required for proofreading and pre-processing. These tasks are usually carried out by a group of experts to ensure the quality and speed up the process. The process takes enormous time and effort. This underscores the necessity for automated or semi-automated methods that streamline the process, reduce time and cost, and ensure high-quality outcomes.

The main goal of this paper is to propose a semi-annotated pipeline for creating an annotated dataset for Russian NER extracted from the literature works of the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. The state-of-the-art Russian NLP will be advanced by using this dataset as a useful resource for NER model benchmarking and training. The dataset will make a significant impact in enhancing the NER model’s accuracy in literature works and also it could be used as a testing resource for other NER models.

The contribution of this research can be summarized as follows:

- Presenting the pipeline for collecting, processing, and annotating the dataset.

- Providing a comprehensive, high-quality, proofreader-annotated dataset for Russian NER.

- Evaluation of the dataset with our NER model to benchmark the performance and illustrate the dataset.

The rest of the paper is divided as follows. Section 2 presents an overview of related datasets for the field of study. Section 3 describes the dataset and the procedure for data collection, annotation, and analyzing the dataset. Section 4 explores the enhancement adjustment for the annotation approach. Section 5 shows the evaluation and validation of the dataset. Section 6 discusses the limitations of the datasets and future work for expansion. Section 7 concludes the research.

2. Related Work

The field of Named Entity Recognition (NER) has seen significant advancements in recent years [3,11]. Many of the most popular datasets for NER tasks used English data, such as CoNLL03 [12] and OntoNotes [13]. However, a new dataset that offers a more thorough comprehension of entity mentions in English newswires, such as NNE [14], has been introduced for nested NER. Also, there are many other datasets for NER training and evaluation but the majority of them depend on English data, and there is a lack of datasets for Russian NER datasets especially for literature purposes. In particular, the analysis of the classification proposed in [11] showed that the possibility of searching for entities in literary texts is presented only in one work, for texts in Italian. The majority of datasets are oriented towards other subject areas and are trained either on news feed texts or on Wikipedia texts [3,11].

2.1. Domain-Specific NER Dataset Creation

The creation of domain-specific NER datasets is emphasized in recent research as a means of improving tool accuracy and performance. The study [15] examined datasets from English literature, highlighting the effects of annotation guidelines. The authors of [16] developed FiNER-ORD for the finance domain, while the authors of [17] presented a German legal dataset with 54,000 annotated items. The Bulgarian Event Corpus (BEC), introduced by [18], is a multi-domain dataset for social sciences and humanities. It showed encouraging outcomes for tasks like event detection, nested NER, and NEL. The paper [19] introduces a 19th–20th-century Serbian literary corpus and a publicly available NER model achieving 91% F1 score across seven entity types. These studies collectively highlight how important domain-specific NER datasets are to enhancing the accuracy and applicability of NER techniques for specific applications.

The study [20] highlights that NER systems sometimes misidentify female names as chemical entities or fail to recognize the names of minority groups. To address such issues, the authors proposed an automated process for dataset creation and testing and refinement of NER systems. This approach is based on contextual analysis, under the assumption that entities within the same context should exhibit consistent meanings. Additionally, large language models (LLMs) can assist in dataset expansion, as shown in [21]. This hybrid approach combines manual and automated annotation, reducing the cost of dataset creation without compromising quality.

2.2. Language-Specific NER Dataset Creation

A commonly used method for creating datasets in other languages involves translating existing datasets from English into the target language. This approach is discussed in [5,22]. However, one significant challenge for some languages is the imbalance in training sample sizes across classes, often due to the lack of annotated texts. This issue is highlighted in [23], where the authors explored methods to balance training samples and expand datasets through part-of-speech (POS) analysis. The primary objective was to enhance overall accuracy by mitigating class imbalance.

Many datasets have been collected for building an NER for the Russian language (see Table 1). In ref. [24], the authors provided a dataset for Russian NER for general purposes. The corpus was collected from the top 10 “Business” feeds on Yandex News. They randomly selected 10 news items for a given day while making sure that the depicted data were removed. After removing titles and HTML elements, the final corpus has 97 documents with source URLs preserved as metadata. Only two types of entities were annotated in the dataset (person and organization) and IOB (inside–outside–beginning) tagging was used for annotating. The dataset is not publicly available (it is only for academic purposes), and there is a copyright to use it. The FactRuEval [25] corpus was created to provide a dataset of Russian texts for building, evaluating, and testing an NER. Russian newswire and analytical essays on social and political problems make up the FactRuEval corpus. The texts were extracted from Private Correspondent and Wikinews. The dataset was annotated by the models that covered the main tasks in the competition held for this purpose. The final corpus consists of 255 documents annotated with the following tags (person, organization, and location). The dataset is publicly available for usage and development. The NEREL [26] corpus was collected for NER and RE in Russian texts. The majority of the corpus is made up of Russian Wikinews articles that have been released under a Creative Commons license, which permits repurposing of the content. There are 49 relation types and 29 entity types in the NEREL dataset. The collection includes 39K relations and 56K entities annotated in more than 900 Russian Wikinews articles. The dataset is publicly available for common use. In ref. [27], the authors provided an approach for preparing data for multilingual Named Entity Recognition. The WikiNEuRal dataset contains annotated data extracted from Wikipedia articles for nine languages (Russian is one of them). They focused on providing entities for (PER, LOC, ORG, and MISC). The WikiNEuRal_RU dataset contains more than 2 million tokens extracted from 105k articles. An approach for automatic creation of NER systems is also presented in [8]. It utilizes the Open information-extraction system combined with mapper to automatically annotate dataset.

Table 1.

Comparison of existing NER datasets and annotation approaches.

2.3. Automating NER Dataset Creation

Through exploring the previous datasets, many of them used manual methods to annotate the dataset. This method ensures the highest level of accuracy since it depends on experts or volunteers to annotate the entities [12,13,14]. Using automation methods that utilize LLMs, pre-trained NER models, or synthetic data generation allows the creation of larger datasets but with variable accuracy [8,27,28]. Some datasets use semi-automating techniques to create links between the entities and auto-annotating for various lemmas based on larger dictionaries [29].

Creating a dataset for solving NLP tasks is an extremely labor-intensive process, prompting researchers to seek automation methods. For instance, the study [30] describes a process for creating datasets for NER and NEL tasks in Greek. The authors used data from Wikipedia, annotating texts for entities of the following types: event, facility, geopolitical entity, location, organization, person, product, and work of art. Additionally, for the NEL task, the dataset was expanded through automatic translation and by supplementing missing links. The resulting dataset was employed to test multiple models. Another approach to dataset creation focuses on identifying artworks, as demonstrated in [31]. This study also relied on Wikipedia articles, with dataset generation based on analyzing the references provided within the articles.

Textual noise, like spelling or typographical or OCR error could also affect the quality of named entity recognition, as shown in [32]. Existing NER models react differently to various noise sources, so it is important to combine results from several models to obtain better results on most types of texts.

This study proposed a semi-automated pipeline with a voting system to create the NER dataset. The method tries to balance between accuracy and time efficiency while ensuring no biases in the annotated entities. The use of multiple models for dataset preparation has also been explored in [33]. This study focused on creating a medical dataset for annotating medical reports, which significantly accelerated the dataset-preparation process. A similar method was employed in [34], where large language models were used to classify texts. Interestingly, a comparison with a baseline model based on the bag-of-words approach and Naive Bayes demonstrated that traditional methods achieved comparable classification quality. Furthermore, when considering cost, traditional methods significantly outperformed LLMs.

By analyzing the available datasets for NER tasks in Russian, we can notice that they were built for general purposes and were collected from common resources on the web like Wikipedia and none of them were targeted for the literature domain. So in this paper, we produce our dataset for literature purposes by annotating works of the Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. This dataset plays a crucial part and will be a significant resource for many NLP tasks related to processing of literature heritage of A. S. Pushkin and in particular NER.

3. Dataset

In this section, we delve into the process of collecting, annotating, describing, and analyzing the dataset. Data collection involves the steps for gathering the dataset and describing the resources to obtain the data. Data annotating describes the process for annotating the dataset and showing the pipeline for achieving that. Data description addresses the structure and contents of the dataset. Data-analysis studies the dataset statistically and visualizes the results.

3.1. Data Collection

The primary resource of our dataset was the Encyclopedia of A. S. Pushkin, which contains short scientific articles dedicated to his works. Also, it references other writers, critics, censors, and other persons related to A. S. Pushkin, not to mention the detailed information about places, dates, and other works that cites each event or workpiece.

This dataset plays a crucial part in building NER systems for literature heritage processing. Literature, particularly works by well-known writers like Pushkin, poses exceptional difficulties for NER because of its complex narrative patterns, blending of real and imaginary characters, and variety of language forms. The purpose of the dataset is to improve NER systems’ capacity to precisely identify and categorize named entities in literary texts by using such datasets for training and evaluation, which will aid academic study and digital humanities initiatives.

3.2. Dataset Annotation

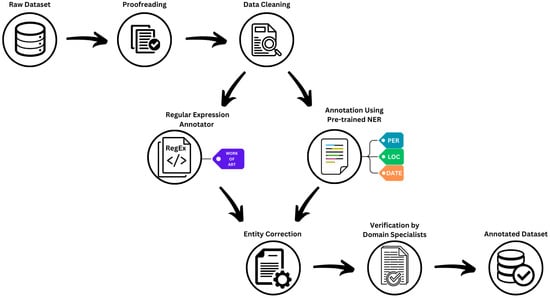

The annotation process consists of several steps as follows:

- Proofreading: the raw dataset was proofread by specialists in order to split each document in the dataset into meaningful paragraphs and to validate the standardization of the text’s structure.

- Data cleaning: This stage aims to process the proofread data in order to clean unnecessary punctuations and prepare the data in the correct format to be annotated by NER models.

- Annotating: This part contains two stages simultaneously—using DeepPavlov [35] to annotate (PER, ORG, DATE) entities and using a regular expression annotator to annotate the work-of-art entities. We built our regex annotator because DeepPavlov struggled with extracting WOA entities from the literature texts.

- Entity correction: This stage aims to automatically check the validation of the annotated entities by previous stages and verify the spans that define each recognized entity.

- Verification: In this stage, the annotated dataset was checked by specialists again to verify the correction of each entity and add any entities that were not recognized by the automated process.

These steps were designed and implemented carefully in order to create a well-defined and high-quality dataset that can be used for Russian NER training and evaluation. The pipeline for annotation of the dataset is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The pipeline of annotating the dataset.

3.3. Data Description

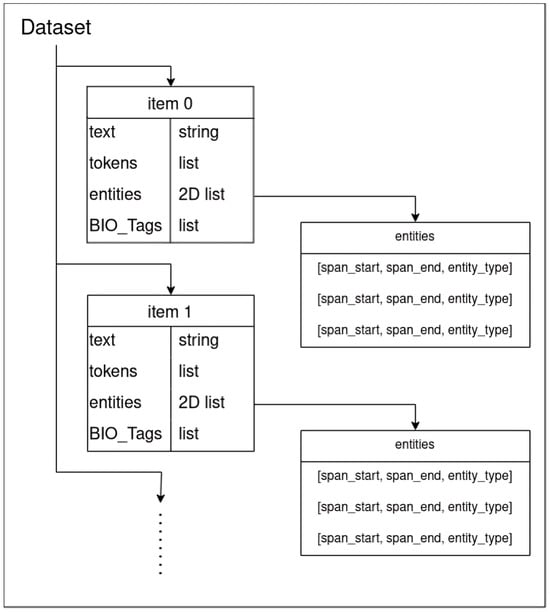

As mentioned before, the dataset was collected from the Encyclopedia of A.S. Pushkin, which contains five volumes with texts about his works in each volume. We only annotated the first volume, which contains 228 texts. The final annotated dataset is stored in JSON format, which is a standard format to facilitate the usage of the dataset and accessing entities. The JSON file contains multiple text examples with the corresponding entities, where each example is represented by a dictionary that holds the text and the annotated tags. The structure of the JSON file is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

The structure of the dataset.

As can be seen from the representation, the dataset is a list of dictionaries where each one represents an example. Each dictionary contains the following keys: “text”, “entities”, “tokens”, and “BIO_Tags”. The “text” key contains a string that represents the original text that was annotated. The “tokens” key is a list that holds the tokens resulting from tokenizing the text example. “BIO_Tags” is also a list that shows the annotation of the tokens using the BIO method, where ‘B’ and ‘I’ followed by the tag type were used correspondingly to indicate the beginning and inside of the entity. On the other hand, ‘O’ indicates the absence of entities. The “entities” key is a 2D list that represents the entities found in the text. Each line contains three items that describe the entity by the start span of the entity, the end span of the entity, the entity type.

These representations of the entities (using a 2D list) in the text make it useful for training and evaluating this dataset using the SpaCy library [36], which uses a similar structure for representations. On the other hand, BIO-Tagging is used by other libraries for training NER models such as DeepPavlov, and that is why we included both of the representations to facilitate the work with the dataset for future users and to make the training and evaluation for NER models more efficient.

3.4. Data Analysis

This subsection presents an exploratory analysis of the data. The data analysis shown below was performed using an Intel Core i5 personal computer with a 1.6 GHz processor, 16 GB of RAM, and an MX130i GPU (Santa Clara, CA, USA). The dataset was examined using fundamental statistical analysis.

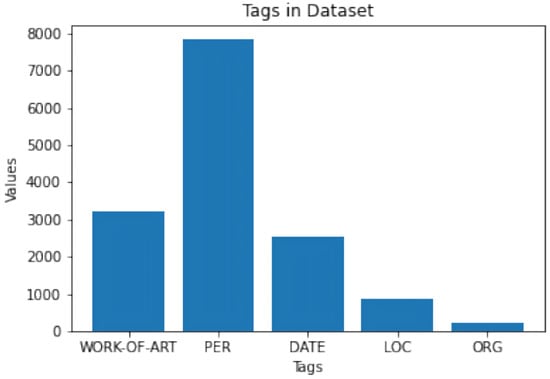

Firstly, we studied the distribution of the annotated tags among the different types (PER, ORG, LOC, WOA, DATE), Figure 3 shows the number of annotated tags for each entity type. As we can see, the most annotated tag in the dataset is PER. DATE and WOA almost have a close number of entities. LOC has a normal number of entities and ORG has the least entities in the dataset. Secondly, We analyzed the dataset statically to find information about the size of tokens and the sample numbers as shown in Table 2. Thirdly, we analyzed each type of recognized entity delivering information about the quantity and average per token, as shown in Table 3. Finally, we created a visualizing function with the help of SpaCy functions to visualize the entities with their corresponding types. This can help with analyzing the dataset and give the user a visual image of the structure. A sample visualization using our function is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3.

The distribution of entity types within the dataset.

Table 2.

General statistics about the dataset.

Table 3.

Statistics about each entity type in the dataset.

Figure 4.

Visualizing sample from the dataset.

4. Automated Pipeline Description for Dataset Creation and Evaluation

This section introduces an enhanced approach to the NER annotation process. A pipeline illustrates the proposed procedure and highlights the evaluation and testing results that support and validate the approach.

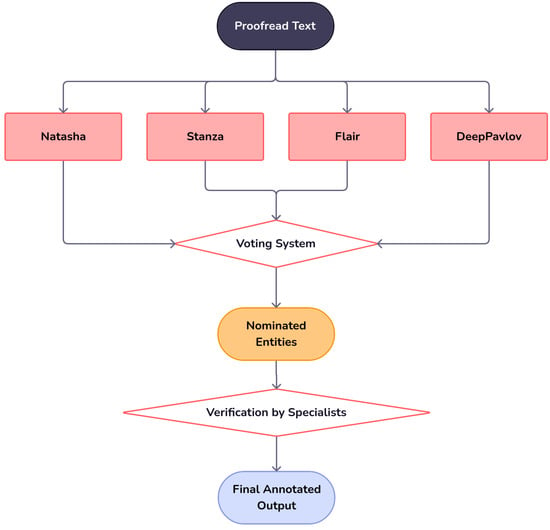

In the annotating process, a pre-trained NER model was used to automatically predict entities for types (PER, ORG, LOC, DATE). This is a common method for automating the annotating process and usually it is followed by human interaction to correct any mistakes. We propose to use multiple pre-trained models for auto-annotation instead of relying on only one model. A voting system that checks the predictions for each model and then elicits the common entities was used to choose which entities should be kept. The voting system could give weights separately for each model depending on the model’s accuracy which can affect how much should be relying on the model’s decision. Another approach for the voting system could be to use majority voting or a certain percentage of the votes, depending on the case study. For our research, we used a voting system that elicited an entity only when all chosen models voted for it. It provides higher precision, which means that the elicited entities have a high chance of accurately belonging to the predicted type. In other words, we can trust that the entities chosen by the system are correct and valid. The proposed pipeline for the voting system is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

The pipeline for the enhancement approach with the voting system.

The proposed voting system depends on four models (Natasha [37], Stanza [38], Flair [39], DeepPavlov [35]). Not all of these models can recognize all the four types of entities that we want to annotate. Table 4 shows entity types recognized by each model. The voting system elicits a prediction only when all of the models vote for the entity taking into account the model’s ability to predict the entity’s type.

Table 4.

The recognized types of entities considered by each NER model.

The general mathematical modeling for the voting system is described in the following way. Let us first define the following items:

- : Set of models used in the system where ;

- : Set of coefficients referring to the importance of each model for the voting system, where ;

- : Set of recognized entities of type k, where ;

- : Set of entities recognized by model , and from type k;

- T: The threshold for electing entities in the voting system.

The selection function:

The set of elected entities from type k is defined as follows:

The final set of entities recognized by the voting system is:

In the proposed system, Equation (2) was simplified by giving the models the same importance . This is because all of the models were trained on general-purpose data and the task is focused on literature works. So, giving significant importance to any of them can lead to bias in the final results. The goal is to elect high-quality and trusted entities for further steps depending on the majority of the votes. This leads to the following:

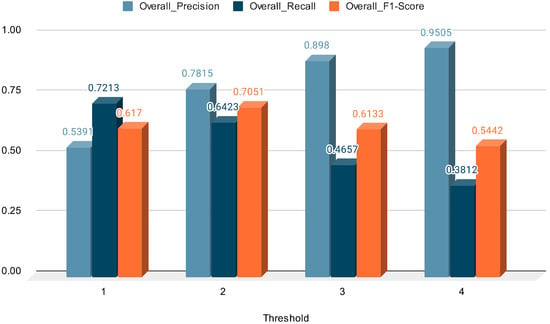

We experimented on a test set with various values of T, as shown in Figure 6. The results show the change in the overall precision, recall, and F1-score by changing the minimal number of voted models to accept a given entity in the final nominated entities. It is clear that by increasing T the trust in the accuracy of the nominated entities increases.

Figure 6.

The results of the voting system by changing the threshold on the test set.

To validate and verify the proposed approach, we tested each of the pre-trained models on the test set and the results are shown in Table 5. We also tested the voting system (by considering the most trusted threshold ) on the test set, and the results are shown in Table 6. The results show high precision for all of the entity types nominated by the voting system compared to relying on one model’s prediction. Also, the overall precision of the system is higher by 28% than using only the SOTA model (DeepPavlov) for auto-annotating. This leads us to trust the predictions auto-annotated by the system. Since it guarantees a high probability of accurately identifying entity spans and types within the dataset, this enhancement can significantly improve the quality of the final dataset after checking by specialists, reduce the time spent verifying, and facilitate the process of creating the dataset by reducing the human interaction factor.

Table 5.

The results of pre-trained models on the test set.

Table 6.

The validation results of the voting system on the test set.

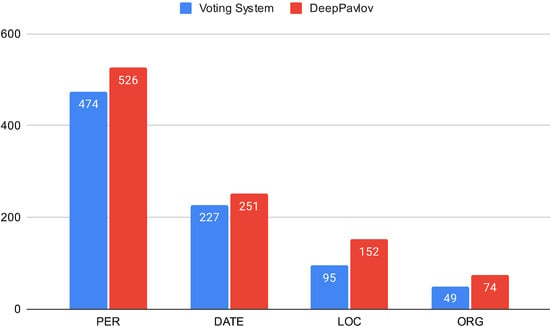

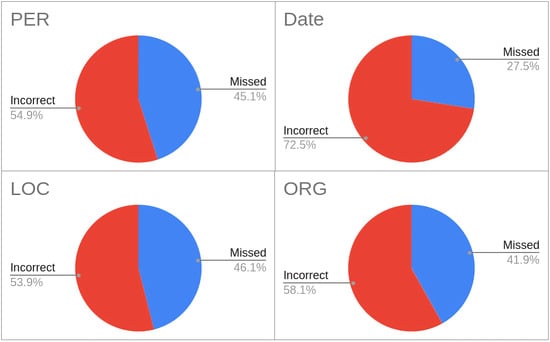

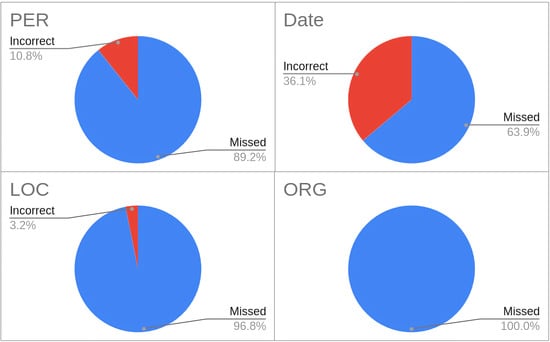

To assess the impact of the voting system in saving specialists’ time and effort during annotation verification, we calculated the number of entities needing changes (additions, deletions, or modifications) after applying the enhanced approach and compared it to the best single pre-trained model (DeepPavlov) with the highest accuracy on the test set. The impact of the voting system by reducing the total number of entities that needed to be fixed and verified by humans is shown in Figure 7 (where the x-axis shows the entity’s type and the y-axis shows the amount of entities). This impact also appears clearly in the number of incorrect entities predicted by DeepPavlov compared to the enhancement approach, as shown in Figure 8 and Figure 9. The voting system achieved better results, since it had significantly fewer incorrect annotations compared to the predictions of the single model. This reflects the importance of the voting system because incorrect entities require more time and effort to fix than missed entities. To fix an incorrect entity, the specialist has to either change the entity or delete it, where missed entities only need to be added. When the auto-annotation process guarantees high-quality prediction and fewer incorrect entities, it gives the chance to the specialists to focus more on missed annotations (rather than checking everything), which will reduce processing time and enhance the quality.

Figure 7.

The total number of entities fixed by each system.

Figure 8.

The percentages of missed and incorrect annotations using only DeepPavlov.

Figure 9.

The percentages of missed and incorrect annotations using the enhancement approach.

The proposed system’s generalized concept can be used to create similar datasets in different languages. It leverages the voting system to facilitate the annotation process, reducing time and cost while ensuring trusted results. We are considering the usage of an enhancement approach for annotating the rest of the volumes (Volumes 2 to 5), since it facilitates the process and saves time while providing high-quality and trusted output.

5. Dataset Evaluation

In this section, we evaluate the dataset and present the experiments conducted to show the reliability and validity of the dataset. We also present results for evaluating the performance of NER models on the dataset.

To show the evaluation and validation of this dataset, we run multiple experiments. In our research [40], we introduced our NER BERT-Based model for recognizing named entities in literature texts. The model was trained and evaluated on this dataset. We split the dataset into train and test sets with a ratio of 80/20. Then we tested our model on the test set and compared the results with DeepPavlov, one of the best models for NER tasks in the Russian language. Table 7 shows the testing results.

Table 7.

Results of testing DeepPavlov and our model on the dataset.

As we can see from Table 7, our model achieved better results recognizing the entities. This reflects the importance of this dataset and its pivotal role in helping to fine-tune NER models to adapt to more complex texts like literature works. This dataset provides a significant role in enhancing NER models by providing complex test cases that usually are not provided on the general dataset used for training the general NER models.

To justify the quality and the size of the annotated dataset and train a robust NER model for our purpose, we used our trained model to extract the named entities in volumes 2–5. We also have a reference table that contains the works-of-art of Pushkin’s works mentioned in these volumes. This table was built using regular expressions and verified by specialists. Then we compared the results of the extracted named entities of type WOA with the entities in the reference table. The model was able to find the majority of the WOA entities that matched with the table achieving a score of 0.97. It only failed to find 22 entities out of 994 total mentioned in the table. These results reflect the quality of the dataset used to train the model and justify that the size of the dataset is reasonable with respect to achieving good results in extracting named entities.

6. Discussion

In this manuscript, the semi-automated pipeline for creating a dataset for NER purposes was proposed. We explained the importance of the voting system in enhancing efficiency and reducing the effort while keeping high-quality results. Also, the Russian Dataset for Literature Purposes (RDLP) dataset for building, training, and testing NER models for Russian literature purposes was presented. We delved into detail about gathering the dataset and the methods followed for annotation and validation. This dataset serves as a resource for advancing the development of NER models for the Russian language. However, there are some limitations of the dataset that should be considered.

The dataset was built depending on the literature heritage of Alexander Pushkin. The texts in the dataset contain many linguistic expressions, descriptions, and metaphors that enrich the dataset but at the same time make it harder for named entity recognition. The texts mostly related to Pushkin’s might not reflect the modern Russian language. Also, from the analysis of the dataset, we can notice that the type entity ORG has a small number of entities due to its scarcity in texts. We understand these limitations, and we made sure to provide high-quality annotations for the entities within the dataset. However, these limitations should be taken into consideration when using the dataset for training or fine-tuning NER models.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, a semi-automated pipeline for creating a dataset specifically for NER tasks as well as a dataset for Russian NER training and testing was introduced based on the pipeline. A comprehensive analysis of the dataset showing its statistical characteristics was provided.

The process for gathering, proofreading, and annotating the dataset was explained. A set of experiments was conducted to validate and evaluate the dataset, providing a public and robust dataset for researchers to use.

Future work will focus on expanding the dataset by including more texts and volumes, generalizing the dataset to contain literature works for other writers, and increasing the types of annotated named entities and inserting relations between them.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.T.; Data curation, E.V.; Investigation, K.K.; Methodology, N.T.; Project administration, N.T.; Software, K.K.; Supervision, N.T.; Validation, E.V.; Writing—original draft, K.K.; Writing—review & editing, N.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the State Research FFZF-2023-0001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are openly available in DataVerse repository hosted by Institute of Russian Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences at https://doi.org/10.31860/openlit-2024.7-A001 accessed on 14 February 2025.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goyal, A.; Gupta, V.; Kumar, M. Recent named entity recognition and classification techniques: A systematic review. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2018, 29, 21–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri, A.; Affendey, L.; Mamat, A. Named Entity Recognition Approaches. Int. J. Comp. Sci. Netw. Sec. 2008, 8, 339–344. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Tong, H.; Zhu, Z.; Li, Y. Nested named entity recognition: A survey. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data (TKDD) 2022, 16, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandsen, A.; Verberne, S.; Wansleeben, M.; Lambers, K. Creating a dataset for named entity recognition in the archaeology domain. In Proceedings of the Twelfth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 11–16 May 2020; pp. 4573–4577. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, J.; Kramer, F. Annotated dataset creation through large language models for non-english medical NLP. J. Biomed. Inform. 2023, 145, 104478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaheen, Z.; Wohlgenannt, G.; Zaity, B.; Mouromtsev, D.I.; Pak, V. Russian Natural Language Generation: Creation of a Language Modelling Dataset and Evaluation with Modern Neural Architectures. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.02470. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, A.; Li, Y.; Cohn, T. Massively Multilingual Transfer for NER. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Matos, E.; Rodrigues, M.; Teixeira, A. Towards the automatic creation of NER systems for new domains. In Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Computational Processing of Portuguese, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 14–15 March 2024; pp. 218–227. [Google Scholar]

- Sboev, A.; Sboeva, S.; Moloshnikov, I.; Gryaznov, A.; Rybka, R.; Naumov, A.; Selivanov, A.; Rylkov, G.; Ilyin, V. Analysis of the full-size russian corpus of Internet drug reviews with complex ner labeling using deep learning neural networks and language models. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, Z.; Mouromtsev, D.I.; Postny, I. RuLegalNER: A new dataset for Russian legal named entities recognition. Sci. Tech. J. Inf. Technol. Mech. Opt. 2023, 23, 854–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, G. Named Entity Recognition Datasets: A Classification Framework. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2024, 17, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, E.T.K.; Meulder, F.D. Introduction to the CoNLL-2003 Shared Task: Language-Independent Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Conference on Computational Natural Language Learning, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 31 May–1 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Weischedel, R.; Pradhan, S.; Ramshaw, L.; Palmer, M.; Xue, N.; Marcus, M.; Taylor, A.; Greenberg, C.; Hovy, E.; Belvin, R.; et al. Ontonotes Release 4.0; LDC2011T03; Linguistic Data Consortium: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2011; Volume 17. [Google Scholar]

- Ringland, N.; Dai, X.; Hachey, B.; Karimi, S.; Paris, C.; Curran, J.R. NNE: A Dataset for Nested Named Entity Recognition in English Newswire. In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova, R.; Kirrane, S.; van Erp, M. Comparing Annotated Datasets for Named Entity Recognition in English Literature. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, Marseille, France, 20–25 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Shah, A.; Vithani, R.; Gullapalli, A.; Chava, S. FiNER-ORD: Financial Named Entity Recognition Open Research Dataset. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.11157. [Google Scholar]

- Leitner, E.; Rehm, G.; Moreno-Schneider, J. A Dataset of German Legal Documents for Named Entity Recognition. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.13016. [Google Scholar]

- Osenova, P.; Simov, K.; Marinova, I.; Berbatova, M. The Bulgarian Event Corpus: Overview and Initial NER Experiments. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 20–25 June 2022; pp. 3491–3499. [Google Scholar]

- Todorovic, B.S.; Krstev, C.; Stanković, R.; Nešić, M.I. Serbian NER&Beyond: The Archaic and the Modern Intertwinned. In Proceedings of the Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, Online, 6–7 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Hu, Y.; Mang, Q.; Hu, W.; He, P. Automated Testing and Improvement of Named Entity Recognition Systems. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM Joint European Software Engineering Conference and Symposium on the Foundations of Software Engineering, San Francisco, CA, USA, 3–9 December 2023; pp. 883–894. [Google Scholar]

- Naraki, Y.; Yamaki, R.; Ikeda, Y.; Horie, T.; Naganuma, H. Augmenting NER Datasets with LLMs: Towards Automated and Refined Annotation. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.01334. [Google Scholar]

- Frei, J.; Kramer, F. German medical named entity recognition model and dataset creation using machine translation and word alignment: Algorithm development and validation. JMIR Form. Res. 2023, 7, e39077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopalakrishnan, A.; Soman, K. Enhancing Named Entity Recognition in Low-Resource Languages: The Crucial Role of Data Sampling in Malayalam. In Proceedings of the 2024 11th International Conference on Computing for Sustainable Global Development (INDIACom), New Delhi, India, 28 February–March 2024; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2024; pp. 1543–1547. [Google Scholar]

- Gareev, R.; Tkachenko, M.; Solovyev, V.; Simanovsky, A.; Ivanov, V. Introducing Baselines for Russian Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Computational Linguistics and Intelligent Text Processing, Samos, Greece, 24–30 March 2013; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; Volume 7816, pp. 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Starostin, A.S.; Bocharov, V.V.; Alexeeva, S.V.; Bodrova, A.A.; Chuchunkov, A.S.; Dzhumaev, S.S.; Efimenko, I.V.; Granovsky, D.V.; Khoroshevsky, V.F.; Krylova, I.V.; et al. FactRuEval 2016: Evaluation of Named Entity Recognition and Fact Extraction Systems for Russian. 2016. Available online: https://dspace.spbu.ru/bitstream/11701/8554/1/2016_Dialogue_Alexeeva_als_FactRuEval.pdf (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Loukachevitch, N.; Artemova, E.; Batura, T.; Braslavski, P.; Ivanov, V.; Manandhar, S.; Pugachev, A.; Rozhkov, I.; Shelmanov, A.; Tutubalina, E.; et al. NEREL: A Russian information extraction dataset with rich annotation for nested entities, relations, and wikidata entity links. Lang. Resour. Eval. 2024, 58, 547–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, S.; Maiorca, V.; Campolungo, N.; Cecconi, F.; Navigli, R. WikiNEuRal: Combined neural and knowledge-based silver data creation for multilingual NER. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2021, Online Event, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 2521–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Heng, Y.; Deng, C.; Li, Y.; Yu, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, C. ProgGen: Generating Named Entity Recognition Datasets Step-by-step with Self-Reflexive Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.11103. [Google Scholar]

- Piskorski, J.; Babych, B.; Kancheva, Z.; Kanishcheva, O.; Lebedeva, M.; Marcińczuk, M.; Nakov, P.; Osenova, P.; Pivovarova, L.; Pollak, S.; et al. Slav-NER: The 3rd cross-lingual challenge on recognition, normalization, classification, and linking of named entities across Slavic languages. In Proceedings of the 8th Workshop on Balto-Slavic Natural Language Processing, Online, 20 April 2021; The Association for Computational Linguistics: Kiyv, Ukraine, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Papantoniou, K.; Efthymiou, V.; Plexousakis, D. Automating Benchmark Generation for Named Entity Recognition and Entity Linking. In Proceedings of the European Semantic Web Conference, Hersonissos, Greece, 28 May–1 June 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, N.; Sierra-Múnera, A.; Ehmueller, J.; Krestel, R. Generation of training data for named entity recognition of artworks. Semant. Web 2022, 14, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadauria, D.; Sierra-Múnera, A.; Krestel, R. The Effects of Data Quality on Named Entity Recognition. In Proceedings of the Ninth Workshop on Noisy and User-generated Text (W-NUT 2024), San Ġiljan, Malta, 19–21 March 2024; pp. 79–88. [Google Scholar]

- Tejani, A.S.; Ng, Y.S.; Xi, Y.; Fielding, J.R.; Browning, T.G.; Rayan, J.C. Performance of multiple pretrained BERT models to automate and accelerate data annotation for large datasets. Radiol. Artif. Intell. 2022, 4, e220007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gokceoglu, G.; Cavusoglu, D.; Akbas, E.; Dolcerocca, Ö.N. A multi-level multi-label text classification dataset of 19th century Ottoman and Russian literary and critical texts. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.15136. [Google Scholar]

- Burtsev, M.; Seliverstov, A.; Airapetyan, R.; Arkhipov, M.; Baymurzina, D.; Bushkov, N.; Gureenkova, O.; Khakhulin, T.; Kuratov, Y.; Kuznetsov, D.; et al. DeepPavlov: Open-Source Library for Dialogue Systems. In Proceedings of the ACL 2018, System Demonstrations, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; Association for Computational Linguistics: Melbourne, Australia, 2018; Volume 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honnibal, M.; Montani, I.; Van Landeghem, S.; Boyd, A. spaCy: Industrial-Strength Natural Language Processing in Python. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/10009823 (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Kukushkin, A. Natasha. Version 1.6.0. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/natasha/natasha (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Qi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Bolton, J.; Manning, C.D. Stanza: A Python Natural Language Processing Toolkit for Many Human Languages. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.07082. [Google Scholar]

- Schweter, S.; Akbik, A. FLERT: Document-Level Features for Named Entity Recognition. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2011.06993. [Google Scholar]

- Kassab, K.; Teslya, N. An Approach to a Linked Corpus Creation for a Literary Heritage Based on the Extraction of Entities from Texts. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).