Abstract

Currently, when the role of biodiversity in maintaining and restoring ecosystems is widely discussed, rot fungi are far from being integrated into common policies, conservation laws, or risk assessment frameworks. Despite the widespread recognition of the natural role of rot fungi as decomposers and their capabilities for various industrial purposes (the treatment of effluents rich in organic or inorganic substances), their peculiar characteristics are poorly understood and investigated. Highlighting the potential of rot fungi is of paramount importance because, as natural resources, rot fungi align perfectly with soil sustainability and the green growth policies and strategies outlined in this decade by the European Commission (2021) and United Nations (2021). This short piece aims to highlight and encourage efforts that channel into the exploration of this group of organisms as bioinoculants and biofertilizers for agriculture and forestry, as remediators and rehabilitators of soils affected by anthropogenic contamination (e.g., metals, agrochemicals, and plastics), and devastated by phenomena arising from climate change (e.g., forest fires) by briefly presenting the pros and cons of each of these lines of action and how rot fungi characteristics may fill in the current knowledge gap on degraded soil rehabilitation.

1. Soil Ecology, Health, and Erosion Control

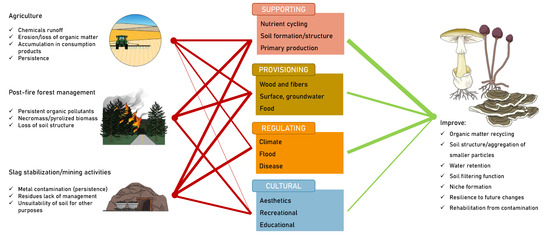

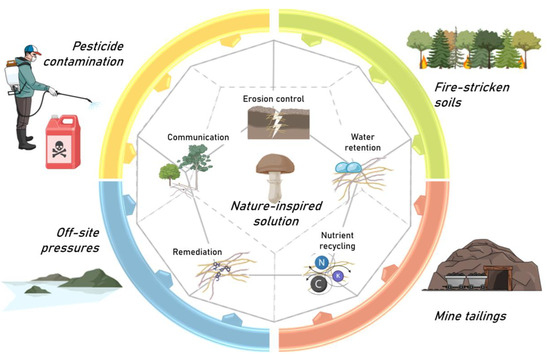

It is important to highlight the primary functions of rot fungi in soils because these functions are fundamental to soil maintenance. They are also known as saprotrophic and decaying fungi. Rot fungi are ubiquitous, occupying a prominent position in nature. Although they often go unnoticed, they play a fundamental role in the decomposition of materials, such as cellulose and lignin [1]. Cellulose and lignin are recalcitrant carbon (C) compounds; that is, forms of C that are resistant to decomposition and are therefore not readily available for use by other soil organisms, such as other microorganisms or plants. Without the action of fungi, plant matter remains in the environment for an indefinite period. The ability to degrade recalcitrant C forms is due to the set of enzymes present in the secretome that act on these sources of organic matter and allow its degradation into more easily decomposable (labile) C forms, which can serve as sources of nutrients for others. Rot fungi largely contribute to the nutrient cycle in the soil; namely, phosphorus (P) and nitrogen (N) [2,3]. By promoting the degradation of organic matter, this group of fungi also contributes to the formation of soil, particularly the upper part called humus [4], improving the physical structure of the soil, its water retention capacity, and, generally, soil productivity (Figure 1). It is also worth highlighting that the growth of these fungi can result in hyphal extensions of hundreds of meters, which constitute up to 70% of soil biomass. This network can function as an expansion route for other decomposer microorganisms with less mobility capacity (e.g., bacteria; [5]) and a communication route between other organisms, such as trees, but it also allows the maximization of soil resources (Figure 1). Soil habitat modification by fungal hyphae dictates the establishment and resilience of bacteria, whereas fungi are unaffected by modifications introduced by bacteria [6]. Soils are spatially heterogeneous, and the hyphal network of these fungi allows the translocation of nutrients from more nutritious places to places of greater scarcity [4], thus indirectly fostering soil-related ecosystem services. These characteristics are highlighted below in the context of environmental rehabilitation, focusing on scenarios of agriculture, forest fires, and land reclamation in mining areas, and are perfectly harmonized with the current political agendas of the European Union [7,8].

Figure 1.

Overview of the main characteristics of rot fungi that can be harnessed and fostered to restore and reclaim anthropogenically stressed or climate change-stressed soils.

3. Drawbacks and Weaknesses

Taking advantage of the advantages of rot fungi mentioned above may be achieved in two ways: by bioaugmentation or biostimulation, each with its advantages and disadvantages that must be discussed.

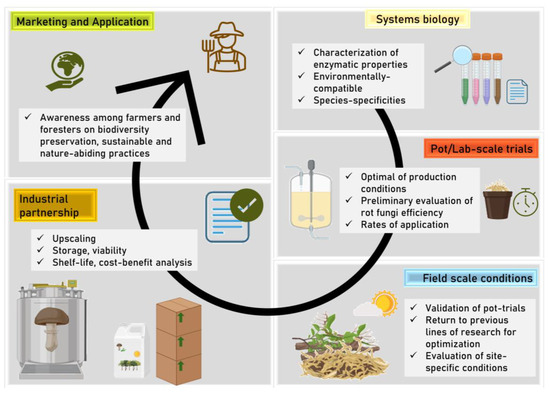

Bioaugmentation involves the introduction of microbial strains with specialized metabolic capabilities that can efficiently break down or transform specific contaminants. It is typically used when the indigenous microbial population lacks the metabolic pathways necessary to effectively degrade certain pollutants. The success of this technique depends on factors such as the compatibility of the introduced strains with the environment, their ability to compete with existing microorganisms, and the general conditions of the contaminated site, which do not appear to be a restriction for rot fungi. However, it is worth noting that with scientific advances, inoculants based on this type of microorganism can be not only naturally occurring strains but also genetically modified organisms, which require strict regulations [61,62]. In the latter case, it is necessary to determine whether native biodiversity is being replaced and surpassed by introduced microorganisms, as this could lead to harmful changes in terrestrial ecosystems, and to avoid that, knowing the biology of rot fungi systems is recommended (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The proposed steps (amongst others) should be considered when developing an inoculant product based on rot fungi, in accordance with the proposed management frameworks for the monetization or rehabilitation of agricultural or forestry/natural soils under various stresses. Despite the unidirectionality of the illustration, there may be feedback and communication between the different steps of the process.

Biostimulation, the second technique, involves modifying environmental conditions to stimulate the growth and activity of microorganisms already existing on site, and is capable of naturally degrading contaminants through the supply of nutrients or other growth-promoting factors. Biostimulation techniques are often applied when the indigenous microbial community has the potential to degrade contaminants; however, for the success of this technique, it is necessary to first know the microbial community of that location and then understand its specific needs so that optimization can be carried out in an ecosystem [63]. In this case, success depends on the time scale because the action of microorganisms may undergo an initial lag phase. In the case of rot fungi, this problem can be minimized because they have low maintenance requirements. However, the combined use of both techniques, whether in the case of agriculture, forestry, or reclaimed soils stressed by different contaminants, could be the most fruitful strategy to be employed [63]. Nevertheless, it is important to keep in mind that field-scale efficiency may not reflect laboratory- or pot-scale trials due to a variety of confounding factors under realistic exposure scenarios (Figure 3).

The options for one of the strategies, or even a combination of the two, are very limited currently due to the lack of knowledge about the role of environmental factors, whether in simulated laboratory conditions or at the field scale. The effectiveness of fungal bioremediation is influenced by environmental factors such as water potential, temperature, and pH [64]. For instance, small temperature increments can substantially increase the secretion of polymeric substances by rot fungi, while water potential rarely influences their activity [64], and the excellent degradation rates of pernicious compounds are usually accomplished under optimal growth conditions according to the species or genus [32]. However, these conditions may be achieved anywhere under realistic conditions of exposure; to realize this, not only must research fill in these knowledge gaps but it must be accompanied by the optimization of fungal formulations and delivery methods for greater bioremediation efficacy [64].

In line with this, other limitations stand out; namely, regarding the development of formulations or delivery methods. The biomass of these fungi can be obtained in large quantities with few resources and very quickly under ideal conditions. This feature may facilitate their expansion into the soil and/or the production of bioinoculant products. However, in the latter case, some difficulties may be identified in terms of industrial-scale production. The mycelial structure that rotting fungi develop in liquid cultures is very different from that in liquid suspensions of bacteria-based inoculants. This can be a disadvantage for their application, as it involves additional processes (such as grinding) prior to the potential packaging and storage of the product, to obtain a product for application that is as homogeneous as possible. Other fungi-based inoculants (such as those based on mycorrhizal fungi) are freeze-dried. This process increases the price of the final product and may therefore reduce its popularity in the market. The storage of rot fungi and their application to soils are two very important knowledge fields; however, in the case of rot fungi, owing to their compatibility with various matrices, it may be possible to place them in matrices containing liquid waste from other food processing industries. In these later steps, establishing connections with industrial partners to increase the technological readiness level of the proposal is a crucial measure (Figure 3).

4. Conclusions

The exploitation of rot fungi on a large industrial scale for remediation is already known worldwide. It is of utmost importance to call on the scientific community to recognize these small ecosystem “engineers” and explore their value in terms of restorative measures for degraded soils in various contexts, such as chemical inputs in agriculture and areas affected by fires and mining. The main advantages of rot fungi include: (i) a wide range of substrates—that is, various pesticides, including organochlorines, organophosphates, and carbamates, or carbonized biomasses or ash—can be used as C sources and, through decomposition, allow for the formation of compounds less toxic; (ii) a predominant ligninolytic enzyme system that includes powerful oxidative enzymes such as lignin peroxidase, manganese peroxidase, and laccase; and (iii) a network of hyphae that allows for the allocation of nutrients to critical areas and the formation of niches, while at the same time providing a complex web that binds together fine particles, reducing the risk of erosion. Together, these characteristics contribute to the rehabilitation of degraded environments, increasing their resilience to future climate change scenarios, and transforming affected landscapes into fertile ground for ecological succession. Exploiting these rot fungi may have new implications in land management. Today, governments prioritize a combination of regulatory enforcement, technological innovation, financial responsibility, and community engagement to ensure the effective remediation of degraded areas. Policies adapted to local conditions and sustained collaboration between the public and private sectors are essential for long-term success and are increasingly featured in the field of nature-based technological innovation.

Funding

This research was funded by CESAM through the FCT—Foundation for Science and Technology (UIDB/50017/2020+UIDP/50017/2020+LA/P/0094/2020), the LabEx DRIIHM—Dispositif de Recherche Interdisciplinaire sur les Interactions Hommes-Milieux, and OHMI—Observatoire Hommes-Millieux International Estarreja for funding the project “CLEAR—Resorting to microbial Consortia to restore metal contaminated soils for the area of EstArReja”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Goodell, B. Fungi involved in the biodeterioration and bioconversion of lignocellulose substrates. Genet. Bio-Technol. 2020, 2, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, P.; Pan, Y.; Ran, Y.; Li, W.; Shao, M.; Zhang, Y.; Ji, Q.; Ding, X. Soil saprophytic fungi could be used as an important ecological indicator for land management in desert steppe. Ecol. Indic. 2023, 150, 110224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, T.; Meng, B.; Rudgers, J.A.; Cui, N.; Zhao, T.; Chai, H.; Yang, X.; Sternberg, M.; Sun, W. Disruption of fungal hyphae suppressed litter-derived C retention in soil and N translocation to plants under drought-stressed temperate grassland. Geoderma 2023, 432, 116396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritz, K.; Young, I.M. Interactions between soil structure and fungi. Mycologist 2004, 18, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tláskal, V.; Brabcová, V.; Větrovský, T.; Jomura, M.; López-Mondéjar, R.; Oliveira Monteiro, L.M.; Saraiva, J.P.; Human, Z.R.; Cajthaml, T.; Nunes da Rocha, U.; et al. Complementary roles of wood-inhabiting fungi and bacteria facilitate deadwood decomposition. Msystems 2021, 6, 10–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano-Caicedo, C.; Ohlsson, P.; Bengtsson, M.; Beech, J.P.; Hammer, E.C. Habitat geometry in artificial microstructure affects bacterial and fungal growth, interactions, and substrate degradation. Commun. Biol. 2021, 4, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: Remaping the Benefits of Healthy Soils for People, Food, Nature and Climate. EU Soil Strategy for 2030. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52021DC0699 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report. 2021. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2021/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2021.pdf (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Santos, I.; Ferreira da Silva, E.; Patinha, C.; Dias, A.C.; Reis, A.P. Definition of areas of probable risk to human health posed by As and Pb in soils and ground-level dusts of the surrounding area of an abandoned As-sulfide mine in the north of Portugal: Part 1. Environ. Earth Sci. 2013, 69, 1649–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Hallat, J.; Castro, A.; Miras, A.; Burgos, P. Heavy metal pollution in soils and urban-grown organic vegetables in the province of Sevilla, Spain. Biol. Agric. Hortic. 2019, 35, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, M.M.; Tuffi Santos, L.D.; da Silva, A.J.; de Pinho, G.P.; Montes, W.G. Metal contamination of water and sediments of the Vieira River, Montes Claros, Brazil. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2019, 77, 527–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Jayakumar, S. Impact of forest fire on physical, chemical and biological properties of soil: A review. Proc. Int. Acad. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2012, 2, 168. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, W.; Liu, L.; Qi, H.; You, H. Biodegradation of decabromodiphenyl ethane (DBDPE) by white-rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus: Characteristics, mechanisms, and toxicological response. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 424, 127716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, The Council, The Europea Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Managing Climate Risks—Protecting People and Prosperity. Strasbourg, France. 2024. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52024DC0091 (accessed on 16 January 2025).

- Hyde, K.D.; Xu, J.; Rapior, S.; Jeewon, R.; Lumyong, S.; Niego, A.G.T.; Abeywickrama, P.D.; Aluthmuhandiram, J.V.; Brahamanage, R.S.; Brooks, S.; et al. The amazing potential of fungi: 50 ways we can exploit fungi industrially. Fungal Divers. 2019, 97, 1–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Xu, Y.; Ding, W.; Li, Y.; Xu, H. Mycoremediation of manganese and phenanthrene by Pleurotus eryngii mycelium enhanced by Tween 80 and saponin. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 7249–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harms, H.; Wick, L.Y.; Schlosser, D. The fungal community in organically polluted systems. In Mycology; Dighton, J., White, J.F.Y., Eds.; CRC Press-Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017; pp. 459–470. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci, A.; Pinzari, F.; Russo, F.; Persiani, A.M.; Gadd, G.M. Roles of saprotrophic fungi in biodegradation or transformation of organic and inorganic pollutants in co-contaminated sites. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyauchi, S.; Navarro, D.; Grisel, S.; Chevret, D.; Berrin, J.G.; Rosso, M.N. The integrative omics of white-rot fungus Pycnoporus coccineus reveals co-regulated CAZymes for orchestrated lignocellulose breakdown. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venâncio, C.; Pereira, R.; Freitas, A.C.; Rocha-Santos, T.A.P.; da Costa, J.P.; Duarte, A.C.; Lopes, I. Salinity induced effects on the growth rates and mycelia composition of basidiomycete and zygomycete fungi. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 231, 1633–1641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borges, J.; Cardoso, P.; Lopes, I.; Figueira, E.; Venâncio, C. Exploring the Potential of White-Rot Fungi Exudates on the Amelioration of Salinized Soils. Agriculture 2023, 13, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verce, M.F.; Ulrich, R.L.; Freedman, D.L. Characterization of an isolate that uses vinyl chloride as a growth substrate under aerobic conditions. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 3535–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feijao, C.; d’Angelo, C.; Flanagan, I.; Abellan, B.; Gloinson, E.R.; Smith, E.; Traon, D.; Gehrt, D.; Teare, H.; Dunkerley, F. Directorate General for Health and Food Safety. In Development of Future Scenarios for Sustainable Pesticide Use and Achievement of Pesticide-Use and Risk Reduction Targets Announced in the Farm to Fork and Biodiversity Strategies by 2030; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium; Luxembourg, 2022; p. 135. [Google Scholar]

- Cherlet, M.; Hutchinson, C.; Reynolds, J.; Sommer, H.; Graham, V.M. World Atlas of Desertification, 3rd ed.; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2018; p. 248. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.; Mol, H.G.; Zomer, P.; Tienstra, M.; Ritsema, C.J.; Geissen, V. Pesticide residues in European agricultural soils–A hidden reality unfolded. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 653, 1532–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenipekun, C.O.; Lawal, R. Uses of mushrooms in bioremediation: A review. Biotechnol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2012, 7, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumpus, J.A. White rot fungi and their potential use in soil bioremediation processes. In Soil Biochemistry; Bollag, J.M., Stotzky, G., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 65–100. [Google Scholar]

- Venâncio, C.; Cardoso, P.; Ekner-Grzyb, A.; Chmielowska-Bąk, J.; Grzyb, T.; Lopes, I. Sources, sinks, and solutions: How decaying fungi may devise sustainable farming practices for plastics degradation in terrestrial ecosystems. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2024, 180, 117898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kijpornyongpan, T.; Schwartz, A.; Yaguchi, A.; Salvachúa, D. Systems biology-guided understanding of white-rot fungi for biotechnological applications: A review. Iscience 2022, 25, 104640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mileski, G.J.; Bumpus, J.A.; Jurek, M.A.; Aust, S.D. Biodegradation of pentachlorophenol by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988, 54, 2885–2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, Q.; Xue, C.; Chen, A.; Shang, C.; Luo, S. Phanerochaete chrysosporium-driven quinone redox cycling promotes degradation of imidacloprid. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2020, 151, 104965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo-State, M.A.M.; Osman, M.E.; Khattab, O.H.; El-Kelani, T.A.; Abdel-Rahman, Z.M. Degradative pathways of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) by Phanerochaete chrysosporium under optimum conditions. J. Radiat. Res. Appl. Sci. 2021, 14, 507–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenipekun, C.O.; Fasidi, I.O. Bioremediation of oil-polluted soil by Lentinus subnudus, a Nigerian white-rot fungus. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2005, 4, 796–798. [Google Scholar]

- Okparanma, R.N.; Ayotamuno, J.M.; Davis, D.D.; Allagoa, M. Mycoremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH)-contaminated oil-based drill-cuttings. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2011, 10, 5149–5156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G.; Shi, Y.; Guo, G.; Zhao, L.; Niu, J.; Zhang, C. Soil pollution characteristics and systemic environmental risk assessment of a large-scale arsenic slag contaminated site. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, C.S.; Olivares, D.M.M.; Silva, V.H.; Luzardo, F.H.; Velasco, F.G.; de Jesus, R.M. Assessment of water resources pollution associated with mining activity in a semi-arid region. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 273, 111148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotons, J.M.; Díaz, A.R.; Sarría, F.A.; Serrato, F.B. Wind erosion on mining waste in southeast Spain. Land Degrad. Dev. 2010, 21, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wu, P.; Wang, G.; Kong, X. Improvement of plant diversity along the slope of an historical Pb–Zn slag heap ameliorates the negative effect of heavy metal on microbial communities. Plant Soil 2022, 473, 473–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajapaksha, R.M.C.P.; Tobor-Kapłon, M.A.; Baath, E. Metal toxicity affects fungal and bacterial activities in soil differently. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 2966–2973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, B.J.; Kleinsteuber, S.; Sträuber, H.; Dusny, C.; Harms, H.; Wick, L.Y. Impact of fungal hyphae on growth and dispersal of obligate anaerobic bacteria in aerated habitats. Mbio 2022, 13, e00769-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, C.; Bi, R.; Guo, X.; Chen, D.; Guo, Y.; Xu, Z. Erosion characteristics of different reclaimed substrates on iron tailings slopes under simulated rainfall. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udom, B.E.; Nuga, B.O.; Adesodun, J.K. Water-stable aggregates and aggregate-associated organic carbon and nitrogen after three annual applications of poultry manure and spent mushroom wastes. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2016, 101, 5–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakya, M.; Sharma, P.; Meryem, S.S.; Mahmood, Q.; Kumar, A. Heavy metal removal from industrial wastewater using fungi: Uptake mechanism and biochemical aspects. J. Environ. Eng. 2016, 142, C6015001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, A.; Spinelli, V.; Massimi, L.; Canepari, S.; Persiani, A.M. Fungi and arsenic: Tolerance and bioaccumulation by soil saprotrophic species. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canonica, L.; Cecchi, G.; Capra, V.; Di Piazza, S.; Girelli, A.; Zappatore, S.; Zotti, M. Fungal Arsenic Tolerance and Bioaccumulation: Local Strains from Polluted Water vs. Alloch. Strains. Environ. 2024, 11, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Yi, B.; Sun, X.; Yu, L.; Wu, L.; Liu, W.; Wang, D.; Li, Y.; Jia, R.; Yu, H.; et al. Removal and tolerance mechanism of Pb by a filamentous fungus: A case study. Chemosphere 2019, 225, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavides, V.; Ciudad, G.; Pinto-Ibieta, F.; Robledo, T.; Rubilar, O.; Serrano, A. Enhancing Laccase and Manganese Peroxidase Activity in White-Rot Fungi: The Role of Copper, Manganese, and Lignocellulosic Substrates. Agronomy 2024, 14, 2562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agbeshie, A.A.; Abugre, S.; Atta-Darkwa, T.; Awuah, R. A review of the effects of forest fire on soil properties. J. For. Res. 2022, 33, 1419–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moazeni, S.; Cerda, A. The Impacts of Forest Fires on Watershed Hydrological Response. A review. Trees. For. People 2024, 18, 100707. [Google Scholar]

- García-Carmona, M.; Lepinay, C.; García-Orenes, F.; Baldrian, P.; Arcenegui, V.; Cajthaml, T.; Mataix-Solera, J. Moss biocrust accelerates the recovery and resilience of soil microbial communities in fire-affected semi-arid Mediterranean soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 846, 157467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fischer, M.S.; Stark, F.G.; Berry, T.D.; Zeba, N.; Whitman, T.; Traxler, M.F. Pyrolyzed substrates induce aromatic compound metabolism in the post-fire fungus, Pyronema domesticum. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 729289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filialuna, O.; Cripps, C. Evidence that pyrophilous fungi aggregate soil after forest fire. For. Ecol. Manag. 2021, 498, 119579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascough, P.L.; Sturrock, C.J.; Bird, M.I. Investigation of growth responses in saprophytic fungi to charred bio-mass. Isot. Environ. Health Studies 2010, 46, 64–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouki, J.; Salo, K. Forest disturbances affect functional groups of macrofungi in young successional forests–harvests and fire lead to different fungal assemblages. For. Ecol. Manag. 2020, 463, 118039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadibarata, T.; Kristanti, R.A.; Bilal, M.; Al-Mohaimeed, A.M.; Chen, T.W.; Lam, M.K. Microbial degradation and transformation of benzo [a] pyrene by using a white-rot fungus Pleurotus eryngii F032. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoni, V.T.; Bankole, P.O.; Semple, K.T.; Ojo, A.S.; Ibeto, C.; Okekporo, S.E.; Harrison, I.A. Enhanced remediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soil through fungal delignification strategy and organic waste amendment: A review. Indian J. Microbiol. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Li, Q.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Zhan, H.; Yu, X.; Zheng, Y.; Xiao, T.; Zhou, L.W. Biodegradation of Benzo [a] pyrene by a White-Rot Fungus Phlebia acerina: Surfactant-Enhanced Degradation and Possible Genes Involved. J. Fungi 2023, 9, 978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, K.; Young, I.M.; Gilligan, C.A.; Otten, W.; Ritz, K. Effect of bulk density on the spatial organisation of the fungus Rhizoctonia solani in soil. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2003, 44, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, O.Y.; Raaijmakers, J.M.; Kuramas, E.E. Microbial extracellular polymeric substances: Ecological function and impact on soil aggregation. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maillard, F.; Schilling, J.; Andrews, E.; Schreiner, K.M.; Kennedy, P. Functional convergence in the decomposition of fungal necromass in soil and wood. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2020, 96, fiz209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrissey, J.P.; Walsh, U.F.; O’donnell, A.; Moënne-Loccoz, Y.; O’gara, F. Exploitation of genetically modified inoculants for industrial ecology applications. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2002, 81, 599–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wozniak, C.A.; McClung, G.; Gagliardi, J.; Segal, M.; Matthews, K. Regulation of genetically engineered microorganisms under FIFRA, FFDCA and TSCA. In Regulation of Agricultural Biotechnology: The United States and Canada; Wozniak, C., McHughen, A., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 57–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyagi, M.; da Fonseca, M.M.R.; de Carvalho, C.C. Bioaugmentation and biostimulation strategies to improve the effectiveness of bioremediation processes. Biodegradation 2011, 22, 231–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magan, N.; Fragoeiro, S.; Bastos, C. Environmental factors and bioremediation of xenobiotics using white rot fungi. Mycobiology 2010, 38, 238–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).