Abstract

Waste haulage represents one of the most critical and cost-intensive operations in surface mining, accounting for up to 50% of the total operating costs. Under such operating conditions, the implementation of continuous systems such as In-Pit Crushing and Conveying (IPCC) is an alternative to truck haulage, as it demonstrates a higher degree of economic efficiency. In a theoretical and practical sense, due to its direct impact on the extraction plan, defining the optimal position of the crusher and consequently the system of conveyors is often the most challenging problem of this methodology. This paper introduces an innovative approach to determining the optimum waste haulage configuration by comparing conventional truck-based transport with IPCC systems. The model is formulated as a Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) problem, explicitly incorporating spatial dimensions and the relocation costs of semi-mobile crushers. The model situates the crusher in a way that reduces transfer costs throughout production periods and it has been tested on a hypothetical open pit.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, over 90% of mineral extraction is conducted through surface mining methods, among which open-pit mining is the most important, considering its high output (production) [1,2]. In all mining methods, the output (whether ore or waste) must be hauled to its destination (either waste-dumping area or the crusher). It has been shown that the haulage costs account for about 50% of capital and operating costs in open-pit mines [3]. Most mines use trucks to transport ore and waste. Trucks are commonly used in open-pit mines, especially in green-field mines, because of their flexibility and maneuverability over short haulage distances [4].

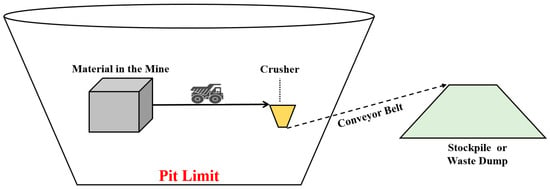

As a mine’s lifetime increases, its size and depth increase as well, which in turn, lead to an increase in haulage distance [5]. This also happens when a mining operation enters a new capacity expansion phase. In such cases, it is necessary to either increase the number of trucks or to increase their size [2]. Under these circumstances, many mines turn to alternative haulage methods such as In-Pit Crushing and Conveying (IPCC). In this system, crushers are commonly coupled with conveyor belts, which are used along all or some of the routes, replacing mining trucks (Figure 1). When using IPCC, rocks must be crushed to a size of under 300 mm by the crushers [6]; usually, the economic advantage (especially in long distances) makes it more economical than trucks. However, generally, using IPCC has some limitations: restriction of use on steep slopes, limitations related to low maneuverability of the system, and minimum annual mine production. All of these, along with potential site-specific characteristics (potentially extreme temperatures, abrasive and sticky materials, etc.) must be taken into account when considering the use of an IPCC system [7].

Figure 1.

Application of an IPCC system as a partial replacement for truck haulage in open-pit mines.

Despite the high investment costs, this method tends to be more economically reasonable since less energy is consumed per cubic meter of material hauled (trucks usually consume 60% of the energy bearing their own weight; in IPCC, this figure is reduced to 20% [4]).

Considering the fact that, in most mines, the stripping ratio (SR) is greater than one, carrying waste occupies a notable amount of costs; therefore, any effort to decrease waste haulage costs (potentially by the implementation of an IPCC system instead of trucks) can contribute to the economy of the mine. This issue is particularly important if we consider that trucks are generally the initial transport system at the beginning of mining, which, in later stages (with potential deepening of the deposit and increasing the stripping ratio), may prove to be an economically inefficient solution. All this leads us to the conclusion that the potential introduction of the IPCC system in one of the phases of the development of mining operations can contribute to the economic indicators of the project. With this in mind, it is clear that issues of IPCC system installation time and location selection, as well as potential system relocations (characteristic of long-term mining operations), become particularly important in the planning process.

IPCC systems can be categorized in to four groups: Fixed IPCC (FIPCC), Semi-Mobile IPCC (SMIPCC), Semi-Fixed IPCC (SFIPCC), and Fully Mobile IPCC (FMIPCC). Generally, in most cases of IPCC application, SMIPCC and SFIPCC are more commonly used because of their adaptability with trucks and their sustainable mechanization [7]. It should be noted that, wherever an IPCC system is mentioned in this paper, we are referring to the SFIPCC type.

2. Purpose of the Work

The purpose of the conducted research is to offer answers to the following important questions:

- -

- Is it economically and technically justified to change the technology from truck to the IPCC system and vice versa?

- -

- When is the best time for technology change?

- -

- Which of the considered locations is optimal for the location of the crusher (solution to the location of the crusher)?

- -

- Finally, if it is economically justified, when is the best time to implement the relocation of the crusher (IPCC system)?

Although the functionalities of the developed model can also be used to optimize the ore transport system, due to the large volume of waste in open-pit mines (compared to ore), this study is dedicated to waste material. Also, the few conducted studies and their positive but often incomplete results were additional motives for conducting this research.

3. Literature Review

One of the most comprehensive reviews of articles about IPCC systems and haulage, conducted up to 2008, was compiled in the book Shovel-Truck Systems, by Czaplicki. Since then, many articles about different aspects of IPCC systems have been published [4]. These include economical aspects [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15], environmental aspects [16,17,18,19,20], operational solutions for using IPCC [6,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32], and the optimization and simulation of IPCC haulage systems [3,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. The optimization and simulation of IPCC systems is one of the most challenging aspects of IPCC use, since they need to be complied with other aspects of open-pit mine design such as mine optimization and production planning. Many researchers have published numerous articles in this field.

In 1985, Lonergan and Barua investigated the location and consequences of the conveyor belt exit method from a pit using the WEDGE software. They aimed to determine the optimal position of the conveyor belt based on the value of mined ore or stripping ratio. Constant production planning was one of the most important features of this article [45].

In 1987, Sturgul applied GPSS software to simulate and determine the best location of the crusher for a semi-mobile IPCC system. In this model, multiple positions of the semi-mobile crusher were considered; eventually, the location with the highest number of truck cycles was chosen as the best location for the crusher. This simulation was based on a short-term plan, ignoring the potential and relatively frequent need to relocate the crusher during the mine’s life [33].

In 1988, Peng et al. tried to determine the size and capacity of IPCC equipment using SCSMLT (Semi-Continuous Simulation) software. In this research, not only was the production plan revised, but the solution was also developed to optimize the size of the excavator, the number of trucks, and the crusher capacity [34]. In 2003, Changzhi came up with an innovative approach to assess the efficient pit depth as a key factor for switching from mining trucks to an IPCC system; however, this model was not able to locate the optimal crusher position [35].

In 2007, Konak et al. developed a method to locate the crusher in a limestone mine in Turkey, but their method lacked the ability to determine the right time to relocate the crusher [36]. In 2009, Taheri proposed a method for determining the location of the crusher in an IPCC system based on finding the lowest cost among different alternatives [37]. In 2014, Rahmanpour et al. successfully implemented the Hub method to identify the optimal location for the crusher; however, this model did not determine the optimal time for switching from mining trucks to an IPCC system [48].

In 2014, Roumpos et al. utilized a computerized model to locate the conveyor belt in an IPCC system. They used short-term mine planning without considering crusher displacement [39].

Osanloo and Paricheh (2016) used a stochastic simulation to identify a suitable crusher location under uncertainty. In their study, simulation was performed only for one year of the mine’s life [40]. In 2016, Yarmuch used a Markov chain to situate the third ore crusher in Chuquicamata, which was based on a short-term mine plan without considering the movement of the crusher [32]. In 2016, Ritter et al. simulated the production capacity using the SMIPCC system, although they did not study other haulage systems [49]. In 2018, Nehring et al. studied the impact of mine production plans on IPCC systems and vice versa by determining the Net Present Value (NPV) and the Internal Rate of Return (IRR) [42].

In 2019, Abbaspour utilized a transportation problem model to determine the right place and time to install an SMIPCC crusher. He based this program on the long-term planning of a mine [43]. In 2019, Samavati et al. used operations research techniques to present a mathematical model for utilizing mobile haulage systems in a mine. The research did not take into account the potential change in pit limits, i.e., it assumed that the pit area was defined and fixed [44]. Paricheh and Osanloo (2019) determined a suitable location for an in-pit crusher and its movement using an optimization model [31]. In their other study (also in 2019), they used a new mixed-integer linear programing model (OPMPS) to link the IPCC system design, an open-pit production scheduling program, and haul fleet sizing problems [50].

Liu and Pourrahimian (2021) presented an integer linear programing model to simulate a production schedule and identify a crusher location for a high, steep conveyor belt. In their article, they aimed to maximize the NPV [51]. Although this model determined the right time and place for applying the IPCC system, the results showed a lack of compliance between the chosen locations and the required crusher area.

In 2022, Shamsi developed a mathematical model based on integer programming. In this model, he determined the optimal location of a crusher in an IPCC system and the optimal time for crusher relocation based on maximizing the NPV [46]. This model included many parameters, and, due to the many applied constraints, it was not easy to reach an acceptable result.

Interest in IPCC systems is constantly relevant, as can be seen in recent research. For example, Kamrani, Pourrahimian, and Askarinasab published two mathematical models that can be used to determine the relocation times and long-term schedule, respectively [52]. Although they suggested some innovative methods for connecting blocks to crusher locations, they did not achieve enough matches using the currently available optimization methods. In 2025, Nikbin et al. pointed out the role of semi-mobile crusher location, haul road design, and the use of machine learning models to predict fuel consumption, reducing energy use by up to 24% [53].

From our review of the literature on IPCC systems, the following points are notable:

- The majority of IPCC simulation systems were performed for ore haulage.

- IPCC utilization studies have mostly been evaluated for a specific time frame (for example, for one year) and have not evaluated the relocation of the system in subsequent years according to the high costs of transfer.

- In most simulations, the block-extraction sequence is changed based on the position of the crusher when an IPCC is used.

- The majority of models have been developed based on the assumption that the solutions are economically feasible, aiming to find the optimal location for the equipment.

- Few articles developed their models on the basis of the simultaneous utilization of two systems: trucks and IPCC.

4. Materials and Methods

The idea of using an IPCC system for transporting waste materials in mines was initially applied in the Grootegeluk coal mine between 1980 and 2000 [2]. Although using IPCC systems for waste haulage is not new, few studies have been performed in the middle of a mine’s lifespan, when issues of increase in haulage distance and waste production (due to mine development) are most prominent. In such situations, it is very important that an optimal transport technology option is chosen (trucks or an IPCC system, or a combination of both) at the right time and in the right place, according to economic benefits.

In this article, a mathematical model for the optimization of the waste-haulage systems used in open-pit mines is presented. The initial assumptions and goals that were made during the research are as follows:

- The presented model has been developed to choose between two options: hauling by trucks (both inside and outside of the pit boundary) or switch to IPCC for a part of the route (especially in the dumping area).

- The presented model can be used to select a suitable waste-haulage system from the options of mining trucks and IPCC systems in middle of mine life when increasing distance justifies usage alternative systems.

- It is assumed that the mine’s design and extraction scheduling are performed based on general optimization methods and that all designs are available.

- Waste volumes, distances, and costs are specified and known in both the system options, and the model simply chooses the most efficient one.

- In the presented model, it is assumed that the mine has been designed for truck haulage; however, considering the increase in hauling distance, uphill haulage, and mine expansion, alternative haulage systems such as IPCC systems potentially become more viable. This scenario is a relatively common case in mining practice.

- Due to open-pit mines’ complex geometry, inside the pit area, haulage is exclusively performed by trucks, while outside the pit, an IPCC system can potentially be utilized.

- Assuming that it is feasible to utilize IPCCs, the crushers are located very close to the pit boundary in order to minimize changes in pit designs.

The mathematical model is designed with the intention of answering the following questions:

- Which destination (dump) is optimal for the waste material to be transported to from every workbench (or pushback) in the pit?

- Are trucks or IPCC systems more economically efficient in the waste-dumping area (outside the pit-exit point)?

- If applying an IPCC system is an economical approach, when is the best time to utilize it?

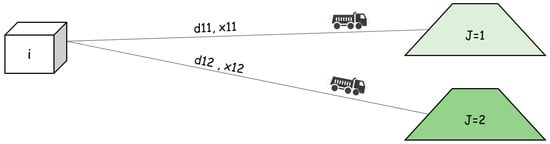

The presented model is a special type of facility location problem. The mathematical solution used for such problems can find the best location for a given facility based on minimizing costs with respect to a set of constraints [54]. In most cases, distance plays an important role in facility location problems and has a direct relation to cost. The distance function between two points, and , is marked ; this is the minimum length of any path between these points. Figure 2 shows a simple case where a unique volume of should be carried to one destination of or through route or the route (whichever is shorter).

Figure 2.

Illustration a simple model with a unique volume to be transported to one of two destinations.

In this situation, the objective function for such a simplified model would have the form shown in Equation (1). This function can find a shorter route by identifying the binary variable, either or which can obtain a number 1 result.

Here, and are the distances between volume and different destinations, and ; and are the binary variables.

In this example, it is assumed that one of two destinations, or , must be selected. This is achieved by applying the following constraint (Equation (2)):

In an extended model with different volumes () and destinations (), the objective function would have the following form (Equation (3)):

If one destination is selected for each volume, then the following constraints can be used (Equation (4)):

Here, is the distance between volume and destination ; is a binary variable that can obtain either 0 or 1.

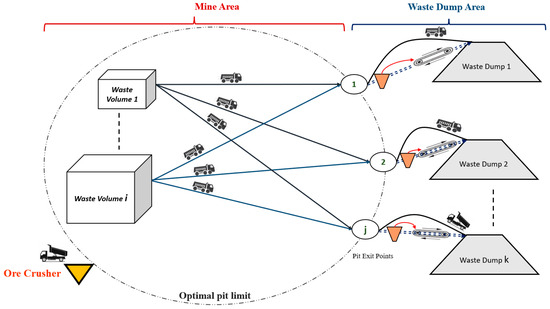

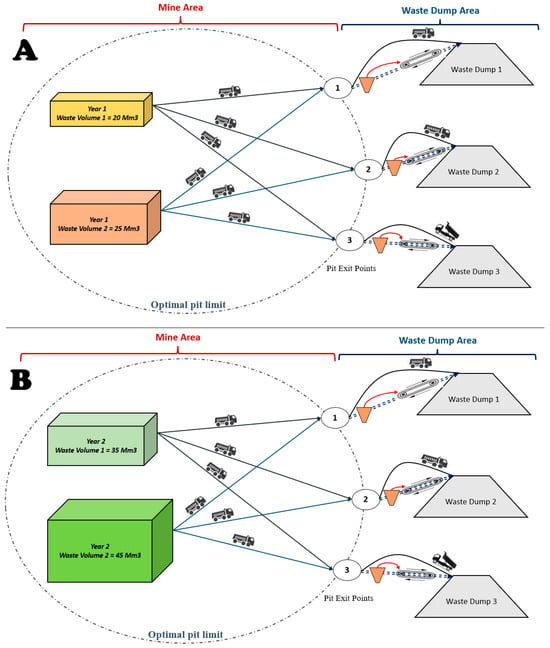

Figure 3 shows a graphic representation for a more comprehensive model. In this model, many different volumes of waste are available that should carry the waste to different pit-exit points ; finally, they can transfer the waste to the waste-dumping areas using different methods, i.e., either trucks or continuous systems (i.e., an IPCC system). The waste volumes refer to the waste materials in different workbenches or pushbacks.

Figure 3.

Illustration of the presented model for selecting a waste-haulage system.

The following sets, variables, and parameters were used for model parameterization.

Sets:

Where are a set of candidate locations ( is the location of the waste volume on the workbenches; is the location of the pit-exit point or the crusher; is the location of the waste dumps; are the indices of the locations). is a set of mining periods in years ( are the indices of the period; in this article, the period is a year).

Parameters:

is the haulage distance for trucks in the mine area from workbench to exit point in year ; is the haulage distance by truck in the waste-dumping area from exit point to dump in year ; is the haulage distance by IPCC system in the waste-dumping area from exit point to dump in year ; is the haulage cost by truck per kilometer in a mine (or waste-dumping area); is the haulage cost by an IPCC system per kilometer; is the discount rate; is the discount factor = ; is the volume in workbench (or pushback) in year .

Variables

is a binary variable (it is 1 if hauling from workbench to exit point in period has been performed by trucks, and it is 0 otherwise; is a binary variable (it is 1 if hauling from pit-exit point to dump in period has been performed by trucks, and it is 0 otherwise); is a binary variable (it is 1 if the IPCC crusher is moved to pit-exit point in period , and it is 0 otherwise); is a binary variable (it is 1 if hauling from pit-exit point to dump in period has been performed by an IPCC system, and it is 0 otherwise); is a binary variable (it is 1 if pit-exit point in period is used for dumping, and it is 0 otherwise).

It should be noted that waste haulage costs using trucks, per cubic meter, and per kilometer in mines are well known and calculable; the total haulage cost from to pit-exit point can be calculated. In addition, waste haulage from pit-exit point to waste dump can be performed by both mining trucks and IPCC systems. If mining trucks are used in dumping areas, then waste is directly taken from in the mine, through pit-exit point , to dump ; here, the haulage costs can be calculated. If it is economically reasonable to utilize an IPCC system, then waste is transported by truck from to pit-exit point (i.e., to the crusher position). The crushed material is then hauled to dump with the system of belt conveyors. In this case, the unit cost for crushing, conveyor haulage, and waste distribution in the dump area are also presented in the model. It is worth mentioning that, if the crusher is moved, then the cost of relocating the crusher can be added to the calculation. This is performed using the variable marked as , which adds the costs of relocating the crusher if is equal to 1. The model aims to select the best type of haulage system (truck or truck + IPCC in mine and dump area), the best destination, and the best haul routes, based on the intention of minimizing the overall costs of moving waste material. Equations (5) and (6) present the objective function, which minimizes the cost of waste material haulage from the mine to the final destination (waste dumps) by selecting the best route and an appropriate hauling system.

For an optimized solution, the constraints in Equations (7)–(12) must be considered.

Equation (7) is used to control the number of routes in the mine; this means that just one exit point (crusher) in the mine can be chosen for each workbench (or pushback) yearly.

Equation (8) and its constraint are related to the number of pit-exit points (crushers) in each period (year). The number of pit exits must be equal to or greater than 1.

Equation (9) refers to a scenario in which just one system—truck or IPCC—is selected for the waste-dumping area. By applying this constraint, only the truck or the IPCC can be chosen to haul the waste to the dumping area.

Equation (10) controls the number of established crushers and the relocation of the crusher(s). If there are any (technical or economical) constraints on the number of times a crusher can be relocated, then this constraint can be set in this equation.

Equations (11) and (12) are innovative constraints that are used for setting the costs of relocating the crushers. Based on this strategy, if a crusher(s) is (are) used in the first year and there is no change in its (their) location in the second year, then the relocation cost is set to 0. Whenever there is a change in the location of a crusher, the related cost is applied through this equation.

Note: These equations can also be applied to ore transportation and overburden scenarios; a small change must be made in the load delivery model to accommodate this.

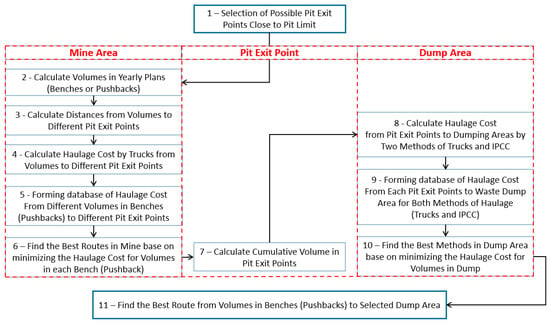

5. Optimization Process

The developed model treats three entities: the mine area, the pit-exit point, and the dumping area (Figure 4). The main input information comes from the pit optimization and mine scheduling plans (as the two main aspects of the pit design). Other required information is obtained by measuring distances from the start to the end point in the yearly plans. As depicted, the algorithm starts by choosing all available exit points near the pit boundary (stage 1). In the next step, all mine data (including the cargo at the workbenches/pushbacks and the distances from the workbenches/pushbacks to the exit points) are collected in a database file and entered into the model as an initial input file. After running the model, the best routes for the trucks in the mine area are selected by minimizing the haulage costs for each volume of cargo (stages 2–6). The next step is to summarize the volumes that have reached each end point (stage 7). These data and haulage distances in the dump area are used to select the most economic haulage system (trucks or IPCC) and the optimal routes for the next stages (stages 8–10). At the end, by running the model, the best route and haulage system for each workbench/pushback is obtained (stage 11). If plans are related to different years, all information from the later years is entered into the model by applying an annual inflation factor. Also, if an IPCC system is used, the cost of installation or relocation can be included in the model.

Figure 4.

Steps of the optimization process in the proposed model.

6. Case Study

In order to evaluate the presented model, a case study was conducted. The model was tested on a hypothetical open pit in the expansion stage, with ore and waste capacities expected to rise between year 1 and year 2.

The waste-haulage system may consist of trucks in the mine area and either trucks or an IPCC system outside the mine area (for transport from pit-exit points to the dump areas). The annual plans for a couple of years were available, and the amounts of generated waste were specified: 45 and 80 million cubic meters in the first and second years, respectively. The designs show an increase in the waste production and haulage distance from the first year to the second year; therefore, a significant increase in the haulage costs is expected. The haulage cost was set as 2.5 for waste material when haulage is performed by trucks [47], and it was set as 0.5 for when an IPCC system is used [43]. The discount rate was set as 10%. It was expected that the haulage system selected to be the best would be that with minimized haulage costs for transport from the first point (mine) to the end point (dump area) via the pit-exit points. Also, it was expected that the model would find the most economic haulage method (trucks or IPCC system). This type of problem is similar to those in which an optimal solution is identified from a large matrix; in such cases, numeric computing platforms like MATLAB (R2021b_Windows) can be helpful. A schematic view of the hypothetical case study is depicted in Figure 5. The other parameters used in this model are shown in Table 1.

Figure 5.

A schematic view related to the case study: (A) Two volumes in 1st year and different workbenches/pushbacks. (B) Two volumes in 2nd year and different workbenches/pushbacks.

Table 1.

Assumed data for the case study.

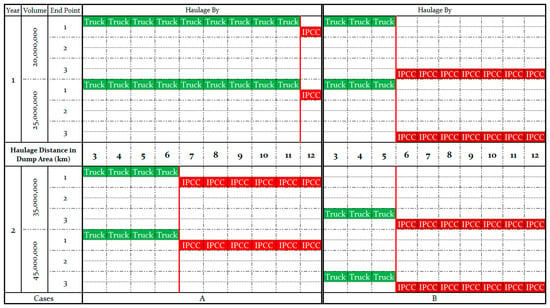

Although the distances in mine areas are fixed, the lengths of the remaining hauling routes may vary, depending on the IPCC system designs and the distance between the pit-exit points and the waste-dumping location. The objective function in this situation comes down to the minimization of the haulage costs from the beginning (open pit) to the end (waste dump). All considered alternatives and the selection of the best option can be calculated in a conventional way, without using a developed optimization model, but this approach is not practical (and, in more complex cases, is not feasible) because it requires significant time resources. In the initial attempt made for this case study, by running the proposed model in MATLAB, the volumes over different years were considered separately; the best haulage method for the dump area was obtained. The results showed that using trucks is more economic when distances are 11 and 6 km in the first and second years, respectively; in both years, pit-exit point 1 was selected (Figure 6A). In the second stage, all volumes in both years were input to the model by considering a 10 percent discount for the second year. The results changed completely. In this attempt, pit-exit point 3 was selected as the best route (instead of pit-exit point 1). In addition, using an IPCC system for distances of more than 6 km was determined to be the best system of haulage; this threshold was identified to be 12 and 7 km in the first stage (Figure 6B). In this way, the type of haulage, routes, and pit-exit points were optimized using this model.

Figure 6.

Waste haulage method as a function of haulage distance. (A) The waste volumes in the 1st and 2nd years were modeled separately; (B) the waste volumes in the 1st and 2nd years were modeled together with a 10% discount for the 2nd year.

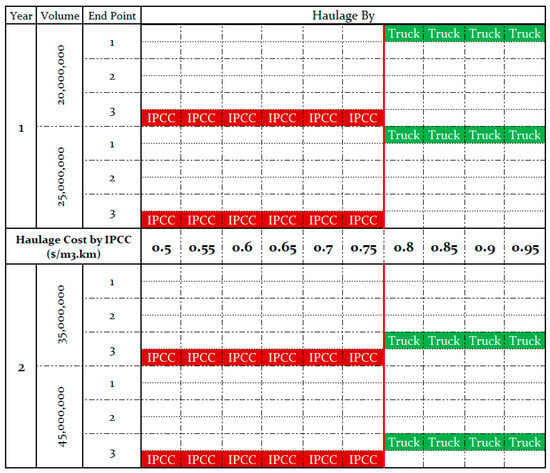

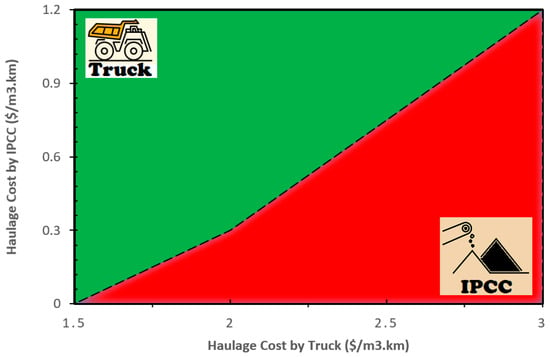

In the following stage, a sensitivity analysis was carried out to select the best haulage system between the truck and the IPCC under different haulage costs for the IPCC (the volumes of both years were input in the model with a discount rate of 10% for the second year). The results are presented for a case where the haulage distance to the dump area is 6 km and the truck haulage cost is 2.5. Figure 7 illustrates the results. As is shown, the IPCC system can be utilized if the IPCC costs are lower than 0.75. In another attempt, considering a fixed haulage distance equal to 6 km (and other information), the economic boundary between the IPCC and the truck haulage systems was found and the results are shown in Figure 8. This graph shows the best haulage system out of trucks or the IPCC system based on the different haulage costs for both.

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analysis of haulage systems based on IPCC haulage cost.

Figure 8.

The economic limit between IPCC and truck haulage system at different haulage cost.

7. Results

The selection of haulage technology in open-pit mines is a critical decision that can be significantly affected by haulage distances and the costs of transporting a given unit of volume. The transportation technology applied in the initial years of operation may potentially need to be changed in the middle stage of a mine’s lifespan due to altered mining conditions. This is particularly evident in the case of waste rock transportation, as the quantities of waste rock usually far exceed the quantities of ore, and the distances and elevation differences between the excavation site (open pit) and the waste disposal site (dump site) tend to increase over time. The mine lifespan and capacity expansion are criteria that must be taken into account; however, these are often overlooked when considering a potential change in transportation technology. The results of this research strongly suggest that the process of optimizing the applied transportation technology, or its potential change, should be carried out and considered practically throughout the entire lifespan of a given mining project, especially in phases characterized by increased capacity, greater heights and distances, or sharp rises in the stripping ratio. Furthermore, a proper approach involves introducing a discount rate into the analysis process, given that many mining projects have lifespans that can be measured in decades.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper presents a model which was designed to identify the following optimal solutions: the best routes for transporting waste from workbenches (pushbacks) to dumping areas; the best haulage system for transporting cargo between mines and the dump area (truck or IPCC system); the best time for switching the haulage method (if it is economically feasible to do so). The developed model combines input parameters and a system of constraints with existing optimization algorithms (Mixed-Integer Linear Programming) in order to generate proposed solutions. All this is calculated based on minimizing the haulage costs from the start point in the mine to the end point in the waste-dumping area. At the beginning, the area of haulage is divided into two parts—the mine and the waste-dumping areas—and all data are calculated for both of them separately.

The input data are the following: volumes of workbenches (or pushbacks) in annual plans, a matrix of distances for each volume to travel to different pit-exit points, the investment costs for increasing the number of trucks or using a new IPCC system, the costs of relocating an IPCC system, the distances between the pit-exit points and the discharge places in the waste-dumping area, and the unit costs of hauling (when using trucks or an IPCC system). The presented model is shown to be especially useful for mines in the development stage and is capable of quickly identifying the best routes and systems for haulage. It is notable that using some computing platforms like MATLAB can enable faster and easier use of this model in comparison with classic calculations. It is also noteworthy that the model is flexible and it is possible to input additional constraints (if any exist). Also, the model reduces the possibility of making mistakes, which are usually present in extensive and demanding calculations. Although this model is practical for defining the best haulage system in mines, it can be improved in the future by directly sharing data with other pit-optimization software (such as NPV Scheduler or Whittle).

Furthermore, the application of this model shows that a clear mathematical approach can give more reliable support for decision making than traditional methods based only on experience or rough cost estimates. The case study results confirm that the model can adapt to different mining conditions and variations in haulage distances and waste production levels while still providing stable and economically sound solutions. This proves that the model can be used not only as a practical tool for day-to-day planning, but also as a useful guide for long-term mine design and investment decisions. Another key point of this research is that the model is clear and easy to understand, so mining engineers and decision-makers can follow the logic behind its recommendations. In summary, the model offers a useful and flexible way to optimize waste haulage in open-pit mines. It helps reduce costs, improve efficiency, and support more sustainable mining practices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.N., D.S. and M.R.; methodology, A.N., D.S. and M.R.; software, A.N. and M.R.; validation, A.N., D.S. and M.R.; formal analysis, A.N. and M.R.; investigation, D.S.; resources, A.N., D.S. and M.R.; data curation, A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, A.N. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, A.N., D.S., D.K. and M.R.; visualization, A.N., D.S. and M.R.; supervision, A.N. and D.S.; project administration, D.S. and M.R.; funding acquisition, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this research can be obtained by sending an email to first author (nasirinezhad@gmail.com).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Hartman, H.J.N.J. Introductory Mining Engineering; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Osanloo, M.; Paricheh, M. In-pit crushing and conveying technology in open-pit mining operations: A literature review and research agenda. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2020, 34, 430–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricheh, M.; Osanloo, M.; Rahmanpour, M. In-pit crusher location as a dynamic location problem. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2017, 117, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czaplicki, J.M. Shovel-Truck Systems: Modelling. Analysis and Calculations; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, E.; Kruse, W. Mobile crushing and conveying in quarries—A chance for better and cheaper production! In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium Continuous Surface Mining, Aachen, Germany, 24–27 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kesimal, A. Different types of belt conveyors and their applications in surface mines. Miner. Resour. Eng. 1997, 6, 195–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasirinezhad, A.; Stevanović, D.; Gnjatović, D.; Markovic, P. Overview of in-pit crushing & conveying technology in open pit mines. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference Mining and Environmental Protection, Sokobanja, Serbia, 22–25 September 2021; pp. 82–92. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, F. In-Pit Crushing System the Future Mining Option. Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy Publication Series. In Proceedings of the Twelfth International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection, Kalgoorie, Australia, 23–25 April 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Purhamadani, E.; Bagherpour, R.; Tudeshki, H. Energy consumption in open-pit mining operations relying on reduced energy consumption for haulage using in-pit crusher systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 291, 125228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sevim, H.; Sharma, G. Comparative economic analysis of transportation systems in surface coal mines. Int. J. Surf. Min. Reclam. 1991, 5, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroder, D.L. The use of in-pit crushing and conveying methods to significantly reduce transportation costs by truck. In Proceedings of the Coaltrans Asia Confererence, Bali, Indonesia, 8–11 June 2003. [Google Scholar]

- de Werk, M.; Ozdemir, B.; Ragoub, B.; Dunbrack, T. Cost analysis of material handling systems in open pit mining: Case study on an iron ore prefeasibility study. Eng. Econ. 2017, 62, 369–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flannery, B.J. In-pit crushing and conveyor transportation of coal at Ulan. Coal J. Aust. 1986, 14, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Althoff, H.; Clark, R.; Orenstein, O. In-pit crushing and conveying reduces haulage costs. C. Bull. 1986, 79, 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Valeri, S.; Pastikhin, D.; Radchenko, S.; Agafonov, Y. Problems and prospects of cyclic-and-continuous technology in development of large ore-and coalfields. In Proceedings of the 12th International Symposium Continuous Surface Mining-Aachen 2014; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 437–445. [Google Scholar]

- Norgate, T.; Haque, N. The greenhouse gas impact of IPCC and ore-sorting technologies. Miner. Eng. 2013, 42, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awuah-Offei, K.; Checkel, D.; Askari-Nasab, H. Evaluation of belt conveyor and truck haulage systems in an open pit mine using life cycle assessment. C. Mag. 2009, 4, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.; Cai, Q.; Zhou, W. A comparison of the energy consumption and carbon emissions for different modes of transportation in open-cut coal mines. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2015, 25, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erkayaoğlu, M.; Demirel, N. A comparative life cycle assessment of material handling systems for sustainable mining. J. Environ. Manag. 2016, 174, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbaspour, H.; Drebenstedt, C.; Dindarloo, S. Evaluation of safety and social indexes in the selection of transportation system alternatives (Truck-Shovel and IPCCs) in open pit mines. Saf. Sci. 2018, 108, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hays, R. Mine planning considerations for in-pit crushing and conveying systems. SME Mini Symp. 1983, 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Plattner, J. History and design of mobile in-pit crushers for open-pit mines. In Large Open Pit Mining Conference; Australasian Institute of Mining and Metallurgy: Parkville, VIC, Australia, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Kutschera, S. Continuous mining and transport of medium-hard materials in opencast mines. In Mining Latin America/Minería Latinoamericana; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1986; pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- Mulukhov, K. Steep-angle conveyor for bulky run-of-mine ore. Trans. Soc. Min. Metall. Explor. Inc. 2002, 312, 199–204. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison, D. The use of continuous materials handling equipment in an open cut iron ore mine. In Proceedings of Iron Ore Conference 2007, Perth, Australia, 20–22 August 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Morriss, P. Key production drivers in in-pit crushing and conveying (IPCC) studies. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2008, 2008, 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, R. Latest IPCC systems provide improved operational flexibility, higher capacity. Eng. Min. J. 2010, 211, 42. [Google Scholar]

- Atchison, T.; Morrison, D. In-pit crushing and conveying bench operations. In Proceedings of the Tenth Iron Ore Conference, Perth, Australia, 11–13 July 2011; pp. 123–131. [Google Scholar]

- Spriggs, G. In-Pit Crushing Considerations for Conveying and Materials Handling Systems. Bulk Solids Handl. 2005, 25, 14. [Google Scholar]

- Dzakpata, I.; Knights, P.; Kizil, M.S.; Nehring, M.; Aminossadati, S.M. Truck and Shovel Versus In-Pit Conveyor Systems: A Comparison of the Valuable Operating Time. In Proceedings of the 16th Coal operators’ Conference, Wollongong, Australia, 10–12 February 2016; pp. 462–476. [Google Scholar]

- Paricheh, M.; Osanloo, M. How to exit conveyor from an open-pit mine: A theoretical approach. In Proceedings of the 27th International Symposium on Mine Planning and Equipment Selection-MPES 2018; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yarmuch, J.; Epstein, R.; Cancino, R.; Pena, J.C. Evaluating crusher system location in an open pit mine using Markov chains. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2017, 31, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturgul, J.R. How to determine the optimum location of in-pit movable crushers. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 1987, 5, 143–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhang, D.; Xi, Y. Computer simulation of a semi-continuous open-pit mine haulage system. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 1988, 6, 267–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Changzhi, Y. In-pit crushing and conveying system and Dexin pit copper haulage optimisation for ore transport. In Proceedings of the Fifth Large Open Pit Mining Conference, Kalgoorlie, Australia, 3–5 November 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Konak, G.; Onur, A.H.; Karaku, D. Selection of the optimum in-pit crusher location for an aggregate producer. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2007, 107, 161–166. [Google Scholar]

- Taheri, M.; Irannajad, M. An approach to determine the locations of in-pit crushers in deep open-pit mines. In Proceedings of the 9th International Multidisciplinary Scientific GeoConference of Modern Management of Mine Producing, Geology and Environmental Protection (SGEM 2009), Albena, Bulgaria, 14–19 June 2009; p. 341. [Google Scholar]

- Londoño, J.; Knights, P.; Kizil, M. Modelling of in-pit crusher conveyor alternatives. Min. Technol. 2013, 122, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roumpos, C.; Partsinevelos, P.; Agioutantis, Z.; Makantasis, K.; Vlachou, A. The optimal location of the distribution point of the belt conveyor system in continuous surface mining operations. Simul. Model. Pr. Theory 2014, 47, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricheh, M.; Osanloo, M. Determination of the optimum in-pit crusher location in open-pit mining under production and operating cost uncertainties. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Computer Applications in the Minerals Industries, Istanbul, Turkey, 5–7 October 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Samavati, M.; ESSam, D.L.; Nehring, M.; Sarker, R. Open-pit mine production planning and scheduling: A research agenda. In Data and Decision Sciences in Action: Proceedings of the Australian Society for Operations Research Conference 2016; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nehring, M.; Knights, P.; Kizil, M.; Hay, E. A comparison of strategic mine planning approaches for in-pit crushing and conveying, and truck/shovel systems. Int. J. Min. Sci. Technol. 2018, 28, 205–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaspour, H.; Drebenstedt, C.; Paricheh, M.; Ritter, R. Optimum location and relocation plan of semi-mobile in-pit crushing and conveying systems in open-pit mines by transportation problem. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2019, 33, 297–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samavati, M.; ESSam, D.L.; Nehring, M.; Sarker, R. Production planning and scheduling in mining scenarios under IPCC mining systems. Comput. Oper. Res. 2020, 115, 104714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonergan, J. Computer-assisted layout of in-pit crushing/conveying systems. In Proceedings of the SME-AIME Fall Meeting, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 16–18 October 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Shamsi, M.; Pourrahimian, Y.; Rahmanpour, M. Optimisation of open-pit mine production scheduling considering optimum transportation system between truck haulage and semi-mobile in-pit crushing and conveying. Int. J. Min. Reclam. Environ. 2022, 36, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsi, M.; Nehring, M. Determination of the optimal transition point between a truck and shovel system and a semi-mobile in-pit crushing and conveying system. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Met. 2021, 121, 497–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AkbarpourShirazi, M.; Adibee, N.; Osanloo, M.; Rahmanpour, M. An Approach to Locate an in Pit Crusher in Open Pit Mines. Int. J. Eng. 2014, 27, 1475–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, R. Contribution to the Capacity Determination of Semi-Mobile In-Pit Crushing and Conveying Systems. 2016. Available online: https://tubaf.qucosa.de/api/qucosa%3A23098/attachment/ATT-0/ (accessed on 5 December 2025).

- Paricheh, M.; Osanloo, M. Concurrent open-pit mine production and in-pit crushing–conveying system planning. Eng. Optim. 2020, 52, 1780–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Pourrahimian, Y. A framework for open-pit mine production scheduling under semi-mobile in-pit crushing and conveying systems with the high-angle conveyor. Mining 2021, 1, 59–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamrani, A.; Pourrahimian, Y.; Askari-Nasab, H. Semi-mobile in-pit crushing and conveying vs. truck-shovel systems: Long-term scheduling with road and conveyor networks integration. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 268, 126122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbin, R.; Bagherpour, R.; Purhamadani, E.; Taherinia, A. Enhancing sustainability in mining by reducing hauling energy consumption through optimization of distance and slope with semi-mobile in-pit crushers and conveyors. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 22119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farahani, R.Z.; Hekmatfar, M. Facility Location: Concepts, Models, Algorithms and Case Studies; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).