Abstract

This study investigates the causes of traffic accidents involving Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS) and Autonomous Driving Systems (ADS) and their interdependencies. Using a source dataset comprising 3015 ADAS accident records and 1085 ADS accident records from National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), the study categorizes accident severity into four levels and applies association rule mining (ARM) to identify high-frequency risk factor combinations. Key risk factors include environmental, road, vehicle, and accident characteristics. Findings show that ADAS accidents are concentrated in highway straight-driving scenarios, strongly correlated with rainy weather, and often involve rear-end collisions due to delayed driver reactions. ADS accidents predominantly occur in intersection stopping scenarios, favor clear weather, and exhibit better safety performance in non-damage cases with Level 5 (L5) systems, though they still face perception and decision-making challenges in complex scenarios like nighttime wet roads. The study further reveals that vehicle design purpose (ADAS for highways, L5 for urban areas) strongly influences accident severity, with L5 systems reducing fatality risks through advanced perception but still affected by high speeds, extreme lighting, and system aging. Make attributes and technological maturity also significantly impact outcomes. This study provides insights for technological advancement, regulatory improvements, and human–machine collaboration optimization.

1. Introduction

Road traffic safety remains a critical global challenge, with approximately 1.19 million annual fatalities and significant economic burdens, costing most countries 3% of their GDP [1]. Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are emerging as a transformative technology, offering substantial potential to enhance safety, optimize traffic efficiency, and reduce emissions.

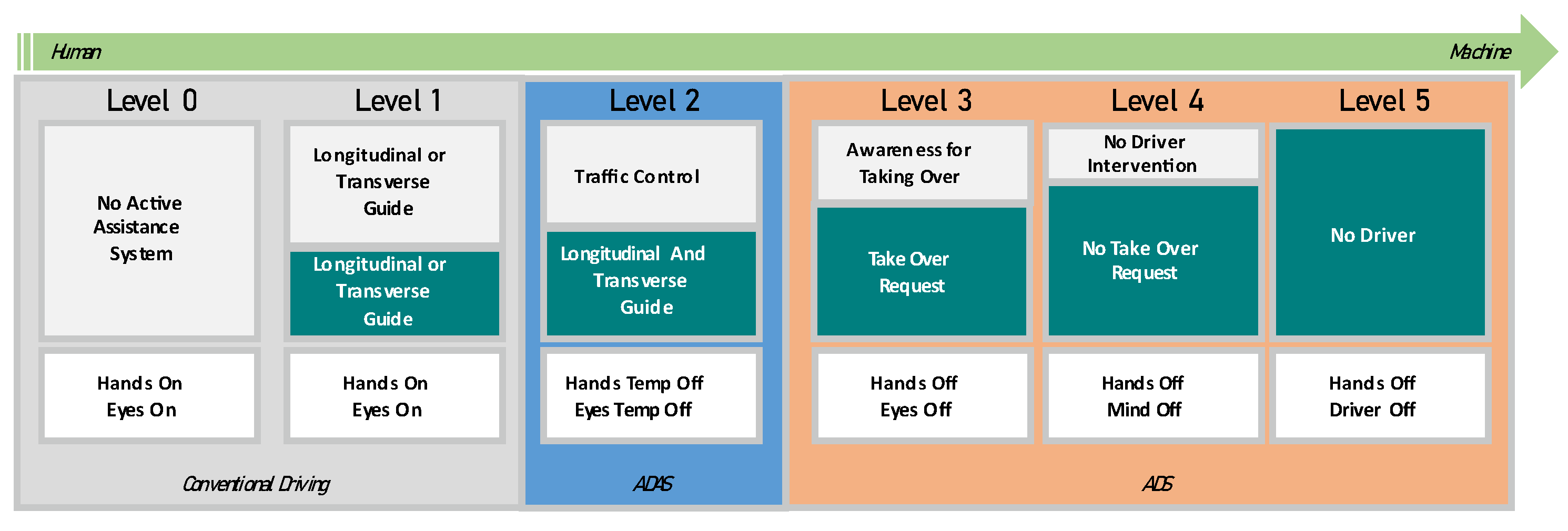

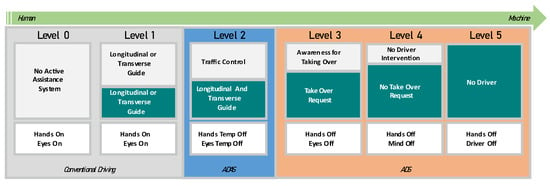

Widespread deployment and testing of autonomous driving systems are underway. Tesla’s Level 2 (L2) automation software has been distributed to over 400,000 users [2], while Baidu’s Level 4 (L4) system has accumulated over 100 million test kilometers (as of Q1 2024). In China, vehicles with advanced driver-assistance functions reached a 47.3% market share in 2023, with numerous cities piloting commercial operations [3]. However, despite these advancements, safety concerns persist, highlighted by notable incidents involving Tesla [4] and Uber [5]. According to the Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) J3016 standard (Figure 1), automation is classified from L0 to L5. L2 systems are defined as Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS), while L3 and above are categorized as Automated Driving Systems (ADS) [6]. While the technical distinctions between ADAS and ADS are well-documented, the implications of these differences on accident causality remain underexplored in safety analysis literature. It is insufficient to merely classify vehicles; it is essential to review safety research through distinct lenses, as the locus of responsibility shifts from the human driver (L2) to the system (L3+).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of levels of driving automation.

First, research specifically examining ADAS (L2) has largely focused on the complex interplay between human drivers and assistance features. Existing studies have firmly established that L2 accidents are frequently rooted in “automation complacency,” where driver over-reliance leads to delayed takeover responses. Conventional statistical models have been widely utilized in this domain to analyze determinants of accident severity [7,8], identifying key contributing factors such as lighting conditions and road characteristics [9]. However, these conventional approaches tend to analyze risk factors in isolation (ceteris paribus). They often fail to capture the complex, non-linear chain of events characteristic of human–machine interaction failures, limiting their ability to reveal how environmental factors specifically trigger human errors in L2 contexts.

In contrast, research on ADS (L3+) operates in a different paradigm where the system assumes full dynamic driving tasks. Due to the relative scarcity of real-world data for higher-level automation, simulation testing is commonly used to replicate hazardous scenarios. While simulation testing [10,11] addresses data scarcity, it often struggles to fully replicate the stochastic nature of real-world mixed traffic. Furthermore, comparative studies between ADS and human-driven vehicles (HDVs) have revealed distinct failure modes. For instance, research indicates that while ADS vehicles mitigate severe collisions due to faster reaction times, their conservative driving strategies paradoxically increase the risk of being rear-ended [12,13,14]. Yet, most of these studies remain descriptive, quantifying what accidents happen, rather than synthetically analyzing the causal mechanisms of why the system’s decision-making logic failed in specific scenarios.

To uncover more complex accident mechanisms, advanced data-driven methodologies have been introduced. Machine learning models (e.g., XGBoost, CART, and Random Forest) [15] and Association Rule Mining (ARM) [16,17] have shown significant promise in identifying non-linear interactions among road infrastructure, vehicle status [18], and vulnerable road users (VRUs) [19,20]. Notably, ARM has demonstrated a unique advantage over “black-box” ML models by producing interpretable rules that pinpoint critical determinant combinations [21,22], demonstrating the method’s capability to capture interpretable risk patterns that traditional models might overlook.

Despite these methodological advancements, a critical conceptual gap remains in the literature: the “Homogeneity Assumption”. A significant portion of current ML-based safety analyses treats “automated vehicles” as a monolithic group or fails to systematically distinguish between automation levels [23]. This aggregation is not merely a classification oversight; it fundamentally obscures the divergent accident mechanisms. It conflates human-centric failures (typical of L2, e.g., distracted supervision) with system-centric failures (typical of L3+, e.g., sensor limitations or conservative logic). Consequently, the resulting safety recommendations are often generic, lacking the precision required to address the specific vulnerabilities of ADAS versus ADS.

To address this gap, the present study conducts a detailed comparative analysis of accident causation between ADAS (L2) and ADS (L3+) vehicles. By leveraging association rule mining, this research aims to identify and contrast the key factor combinations that influence accident likelihood and severity across these distinct automation levels.

This study makes two primary contributions: 1. An automation-level decoupling framework is established based on SAE J3016, enabling a longitudinal comparison between ADAS/L2 and ADS/L3+ to reveal divergent interaction patterns. 2. A four-tier injury severity quantification model (none/minor/moderate/major) is developed, and the Apriori algorithm is employed for differentiated rule mining across severity levels. The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 outlines data selection and classification; Section 3 details the methodological principles of association rule mining; Section 4 examines the screening and interpretation of generated association rules; and Section 5 provides concluding remarks and discussion.

2. Materials and Methods

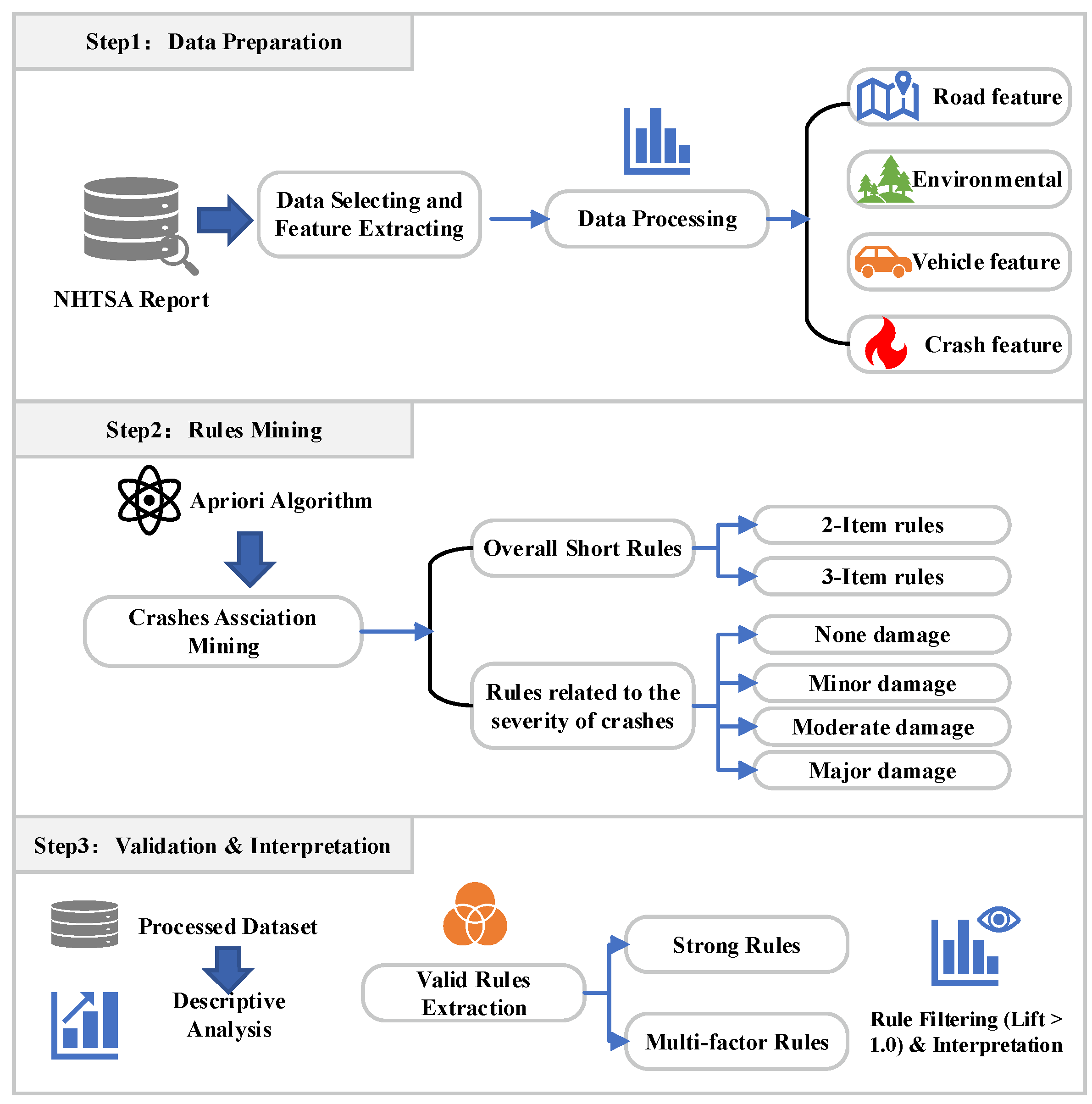

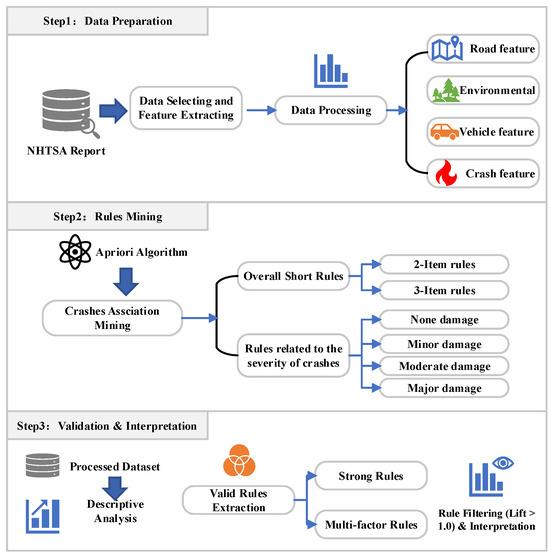

To ensure the rigor and reproducibility of the analysis, this study adopts a systematic three-phase research framework, as illustrated in Figure 2. The procedure encompasses data preprocessing, parameter optimization, and rule validation.

Figure 2.

Schematic overview of the research methodology.

2.1. Data Source

The availability of data is crucial for drawing accurate and meaningful insights. Currently, datasets related to autonomous vehicle accidents are limited, with relatively few studies focusing on real-world usage, collision incidents, and user experiences. Reliable data sources and sufficient data volume are essential for effective safety evaluation of vehicles equipped with autonomous driving systems. The NHTSA serves as one of the primary data sources for investigating accidents involving ADS/ADAS-equipped vehicles. For instance, studies by [24] have utilized this database to identify accident scenarios and collision patterns. Previous research has also employed the CA DMV database (for ADS-related incidents) [16,21], the Strategic Highway Research Program 2 (SHRP 2) Naturalistic Driving Study (NDS) (focusing on driver/operator behavior) [25], and the German In-Depth Accident Study (GIDAS) dataset (pedestrian-related) [26].

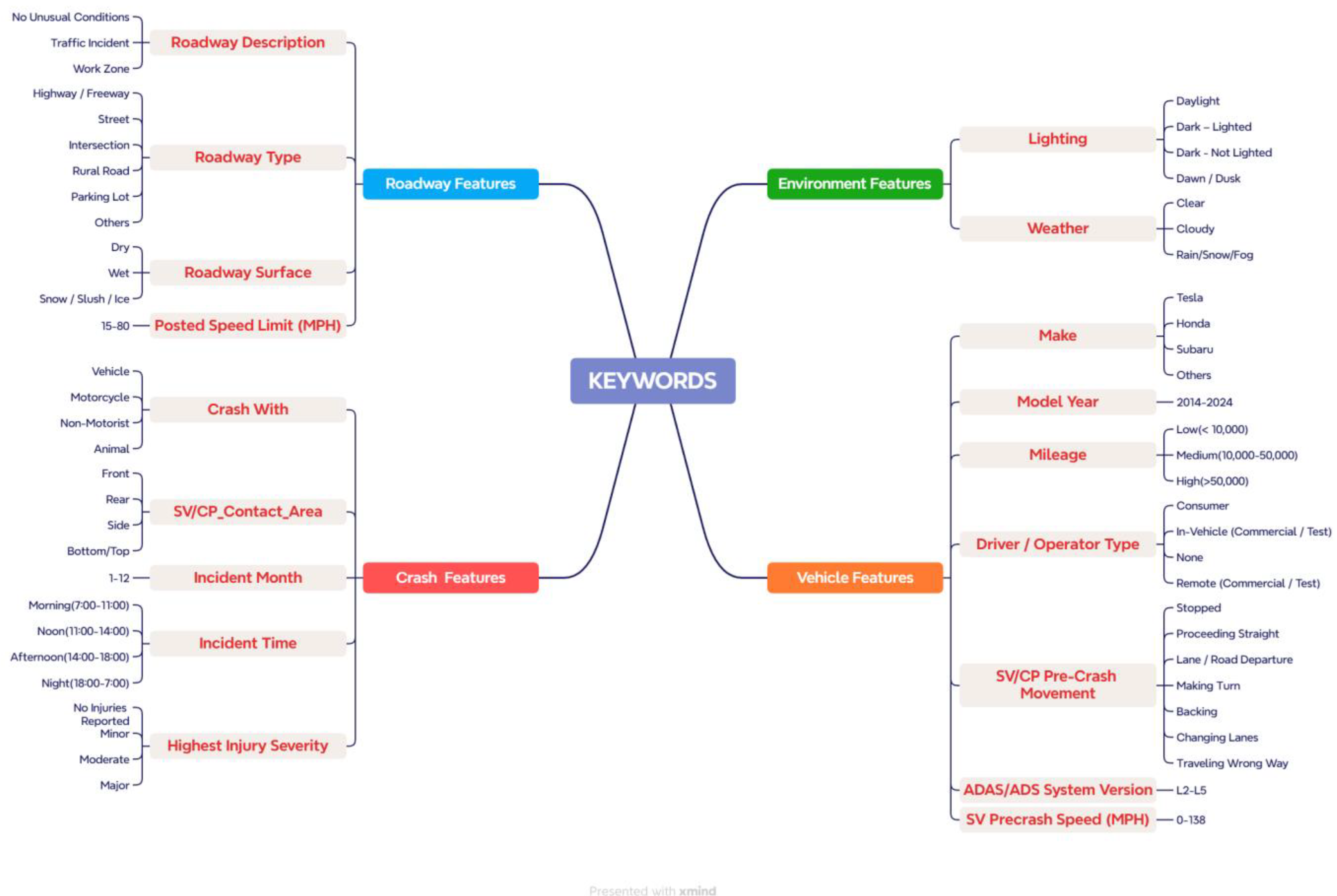

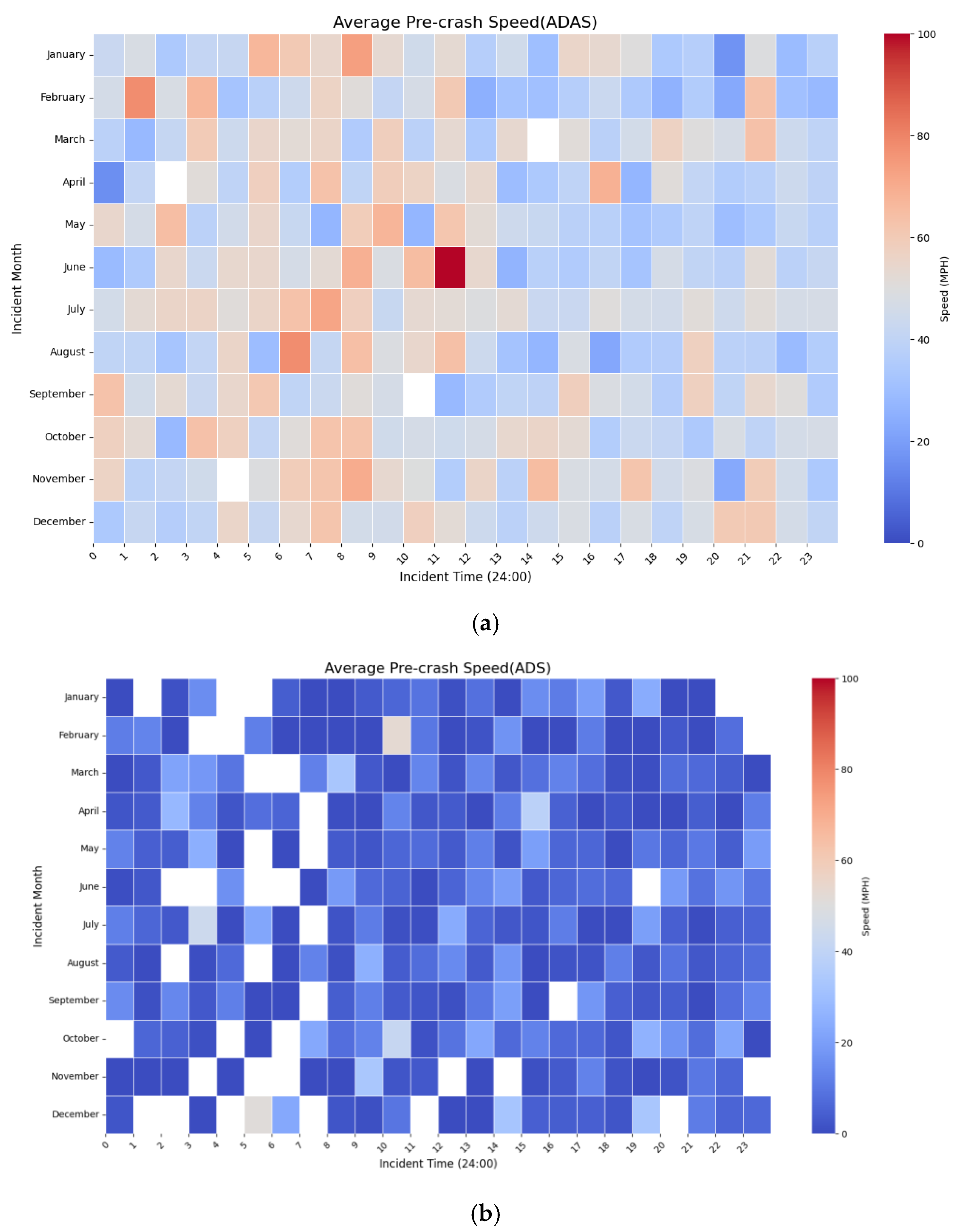

Building on the previous analysis, the NHTSA accident data were selected due to their authority, richness, timeliness, geographical representativeness, and applicability to research. This study incorporates 3015 ADAS incidents and 1085 ADS incidents from NHTSA. Figure 3 presents the candidate variables from the datasets.

Figure 3.

Classification of factor keywords.

2.2. Data Preprocessing

Our research focuses on accident severity, particularly injury outcomes categorized as: No injury, Minor injury (no medical attention required), Moderate injury (medical treatment without hospitalization/emergency care), and Major injury. The ‘Major’ category aggregates ‘Severe’ and ‘Fatal’ cases to address the sparsity of fatal samples, ensuring sufficient data support for the Apriori algorithm while preserving the causal homogeneity of high-risk accident mechanisms.

Conventional autonomous vehicle accident studies typically consider: Vehicle factors (type, age, operation mode), Road factors (type, surface condition, markings), Environmental factors (weather, illumination), Collision characteristics (type, object, pre-crash status), Temporal factors (date/time).

These parameters enable comprehensive association analysis [18,27,28,29]. However, few studies systematically incorporate:

- Manufacturer variations in vehicle design/software algorithms affecting sensor accuracy, decision-making protocols, and actuator responsiveness.

- Accumulated mileage indicating vehicle wear and maintenance status.

- Speed limit compliance impacts reaction times and stopping distances.

- Operator type (human/AI) influencing system interaction dynamics.

- Pre-crash velocity as a critical severity determinant.

Our preprocessing removed features with constant/near-constant values across the dataset to ensure meaningful association rules. The final dataset comprises 20 variables across four categories, as shown in Figure 3.

2.3. Data Analysis Method

This study employs Association Rule Mining (ARM) to uncover the hidden relationships between risk factors. The specific algorithm and analysis steps are detailed below.

2.3.1. Apriori Algorithm

Data mining is the process of extracting potentially valuable information from large amounts of data using a combination of artificial intelligence, machine learning, statistics and database techniques. Association rule mining (ARM) is an important data mining technique that identifies factors that occur simultaneously in a given event. In this study, ARM is used to identify a set of influences that often co-occur in ADAS and ADS incidents.

There are various types of association rule mining depending on the algorithm used to generate the rules, among which the Apriori algorithm is the most popular and widely used algorithm in association analysis. Therefore, the Apriori algorithm is adopted in this study for analysis. The Apriori algorithm consists of two main parts: (a) finding frequent itemsets, (b) generating strong association rules based on frequent itemsets.

The association rule is defined as follows: let be the set of all items, called the item set, where is a set of transaction items, where each transaction corresponds to a unique identifier TID (Transaction ID) and each transaction item is a non-empty subset of I (t ⊆ I). A rule is of the form where and . X is the antecedent of the association rule and Y is the consequent of the association rule. Confidence, support and lift are three key parameters in association rules for identifying and screening strong rules in a dataset. Support measures the prevalence of a rule, defined as the probability that item X and item Y occur together. The support metric can be calculated as follows:

where is the number of events with antecedent variable X; is the number of events with Y as a consequent; is the number of events with both X antecedent and Y consequent; N is the total number of events; and are the support of X antecedent and Y consequent, respectively, whereas is the support of the association rule .

Confidence measures the accuracy of a rule and is the probability that event Y occurs under the condition that event X occurs. It is calculated by the formula:

In this study, we assess the strong correlation of typical rules based on the degree of lift. A lift value greater than 1 indicates that there is a significant association between X and Y.

2.3.2. Analysis Steps

To ensure the robustness of the identified accident patterns, the association rule mining was conducted following a systematic three-step framework:

- (1)

- Parameter Optimization Strategy

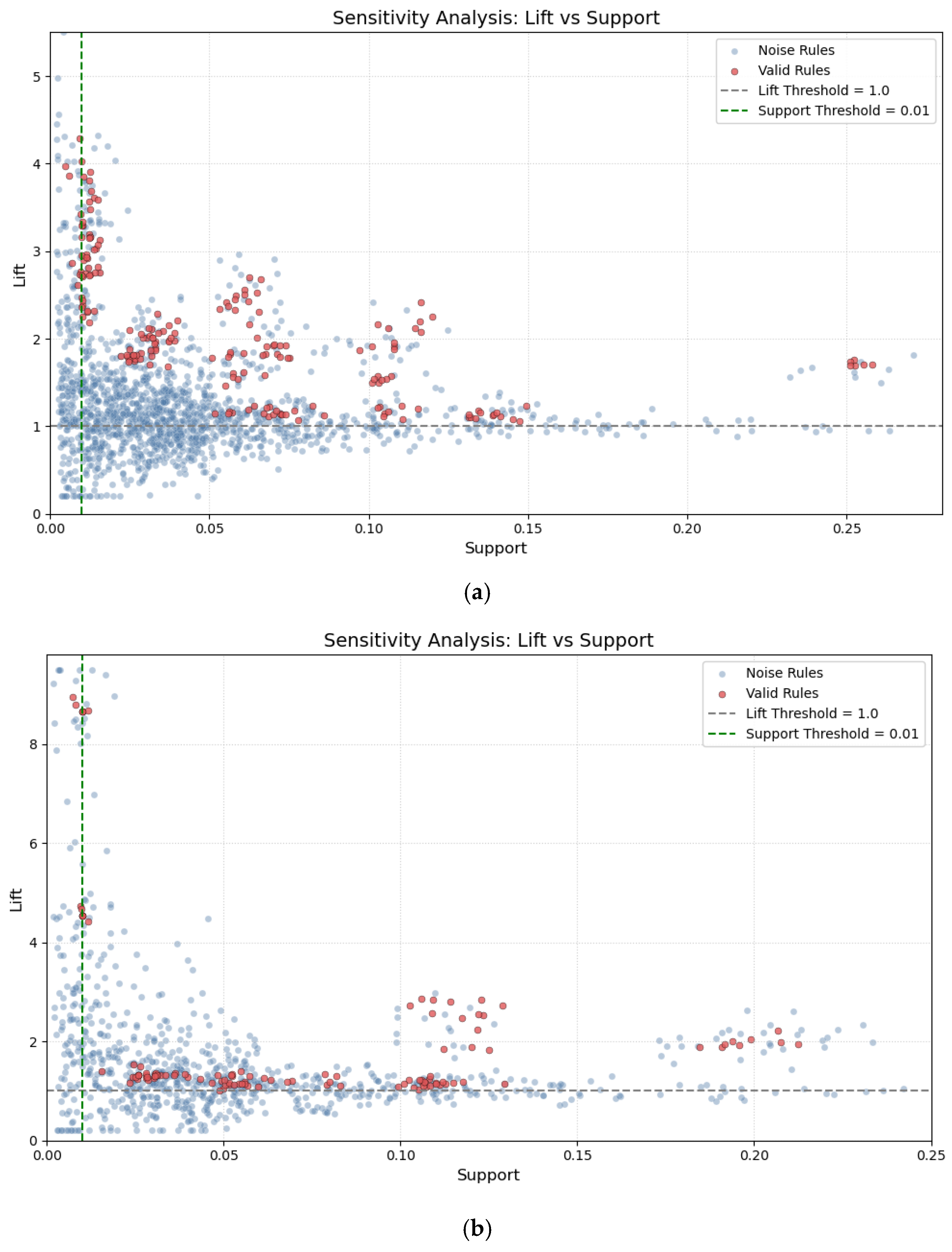

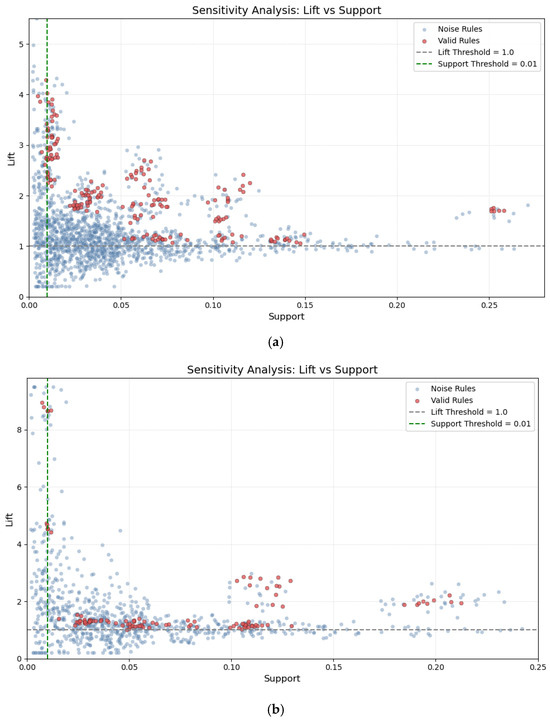

The Apriori algorithm requires predefined thresholds for Support (S), Confidence (C), and Lift (L). Previous studies on traffic safety typically set minimum support between 1 and 10% and confidence between 60 and 70% [30,31]. And the threshold for lift is usually set at around 1.5 [32]. However, applying these general thresholds rigidly may not suit the specific distribution of ADAS/ADS accident data. In this study, we combined these literature baselines with a data-driven sensitivity analysis (visualized in Figure 4) to determine optimal thresholds.

Figure 4.

Sensitivity analysis of association rules (Lift vs. Support distribution). (a) ADAS dataset; (b) ADS dataset.

Support (): As shown in Figure 4, the rules exhibit a clear long-tailed distribution. Rules with high support (S > 0.1) cluster around a Lift of 1.0, indicating that frequent patterns are often trivial (e.g., common driving behaviors). Conversely, high-Lift rules (strong correlations) are concentrated in the low-support region. To avoid filtering out these high-risk but low-frequency events (e.g., fatal accidents in specific edge cases), we adopted a dynamic threshold strategy. The support threshold was set to 0.01 for severe/fatal injury models to capture critical rare patterns. For minor/no-injury models, a higher threshold (0.05–0.2) was applied.

Confidence (): The minimum confidence was set to 0.6 to ensure strong conditional probability between the antecedent and consequent.

- (2)

- Rule Generation

Using the ‘mlxtend’ library in Pycharm, the algorithm scanned the transaction database to identify frequent itemsets meeting the criteria. Subsequently, association rules were generated from these itemsets, retaining only those that satisfied the threshold.

- (3)

- Validation Approach

To validate the meaningfulness and stability of the extracted rules, a dual-criteria approach was applied:

- Figure 4 illustrates the distribution of “Noise Rules” versus “Valid Rules”. The vast majority of noise rules fall below or near a Lift of 1.0, representing random co-occurrence. By enforcing a strict filter of Lift (L) > 1.0 and Confidence(C) > 0.6, we effectively separated valid correlations from background noise, ensuring result stability. A lift value greater than 1 confirms that the occurrence of the antecedent provides a positive information gain regarding the consequent.

- The statistically valid rules were further screened through manual inspection based on domain knowledge to eliminate redundant or common-sense associations, focusing on non-trivial patterns relevant to ADAS/ADS safety mechanisms.

3. Results

This section presents the statistical findings derived from the NHTSA datasets, focusing on accident distribution, severity correlations, and the identified association rules for both ADAS and ADS vehicles.

3.1. Overview of Accidents

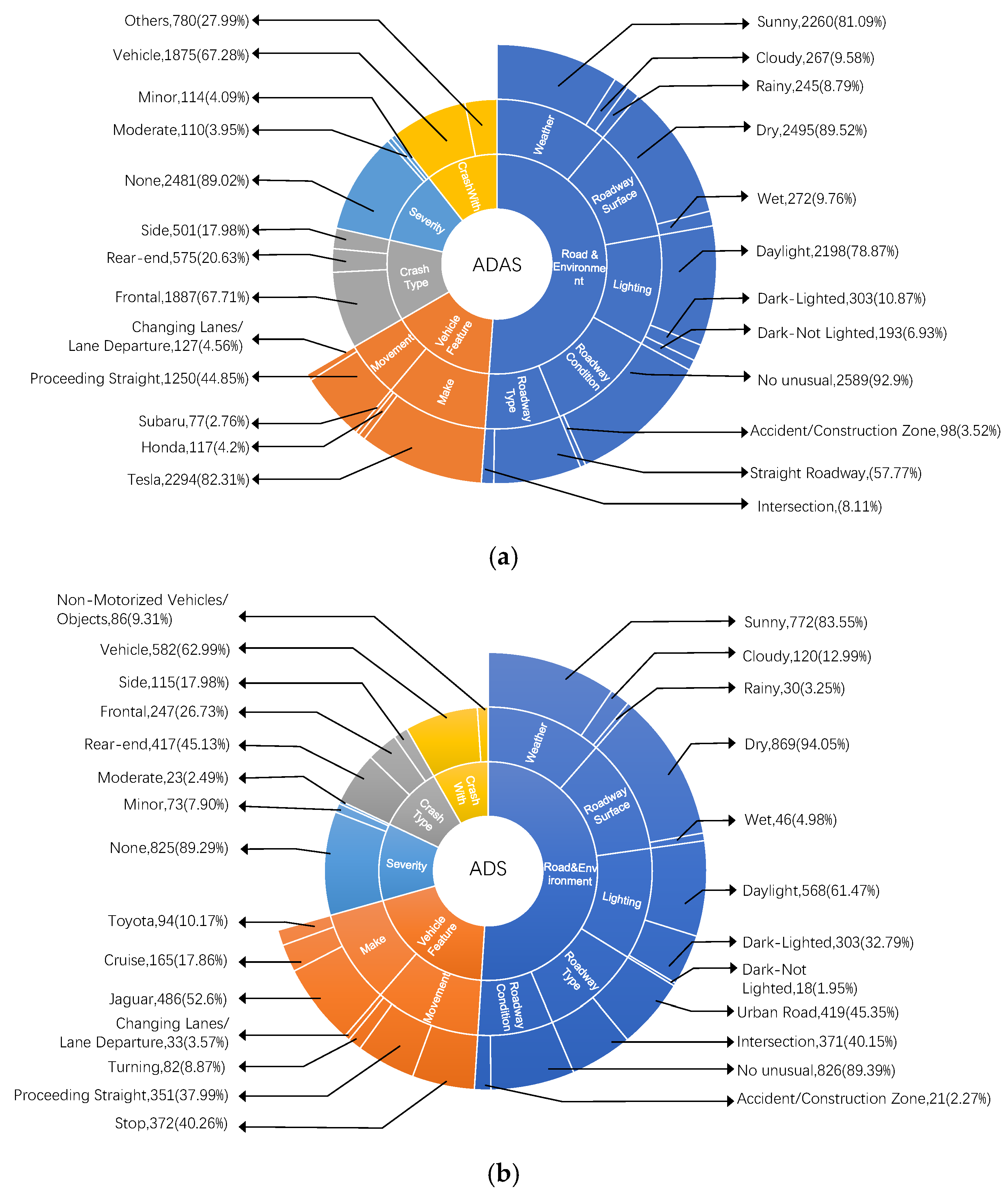

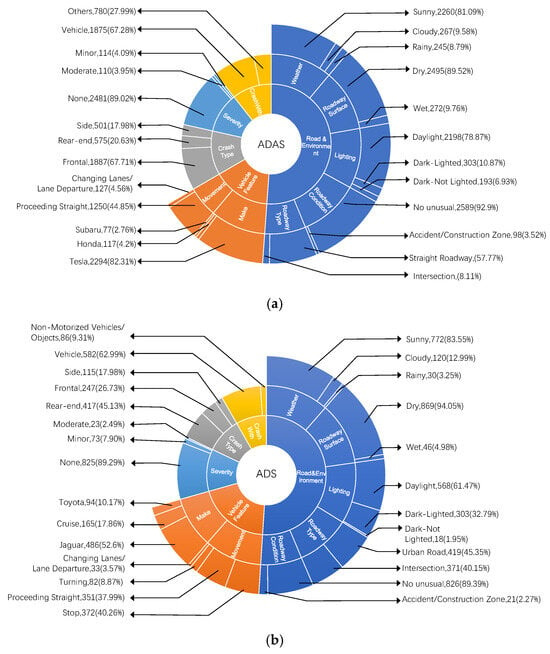

This study begins by comparing the overall trends in accidents involving ADAS and ADS within the dataset. Figure 5 illustrates the main factors affecting both types of accidents. As shown in Figure 5a,b, the percentage of ADAS and ADS accidents in which the vehicle was involved as the participant was 67.28% and 63%, respectively, while 89% of accidents for both types of vehicles resulted in no casualties.

Figure 5.

Distribution of the factors influencing accidents of various vehicle types. (a) ADAS accidents. (b) ADS accidents.

Significant differences between ADAS and ADS accidents were found in the type of road, the state of the vehicle prior to the accident, and the lighting conditions. For ADAS accidents, the most common pre-accident state is straight-ahead, accounting for 44.85%. In comparison, the proportion of straight-ahead state in ADS accidents is 38%, but ADS accidents have a higher proportion of parking state, around 40%. When combined with road type analysis, 57.77% of ADAS vehicle accidents occur on straight roads (Highway/Freeway, Street and Rural Road), and the proportion of accidents at intersections is 8.11%, while ADS vehicles have a significantly higher percentage of accidents at intersections (40.15%) and on urban roads (45.35%).

Considering environmental factors, most ADAS and ADS accidents occurred on sunny days. However, ADAS accidents occur more frequently in rainy weather (8.79%), compared to just 3.25% for ADS accidents. In addition, ADAS and ADS accidents occurred mainly during the daytime, with ADAS having a slightly higher percentage of accidents at 78.87 per cent compared to 61.47 percent for ADS. At night, the proportion of ADAS accidents is about 18%, while the proportion of ADS accidents under illuminated conditions reaches 32.79%, and the proportion of accidents under non-illuminated conditions is only 1.95%.

In terms of accident types, ADAS accidents are predominantly frontal collisions, where ADAS vehicles hit other vehicles, accounting for 67.71%, while rear-end collisions (other vehicles colliding with ADAS vehicles) and side-impact accidents account for about 20%. In contrast, rear-end collisions accounted for a significantly higher percentage of ADS-related accidents at 45.13%, frontal collisions accounted for 26.73%, and side-impact accidents accounted for a similar percentage of ADAS accidents.

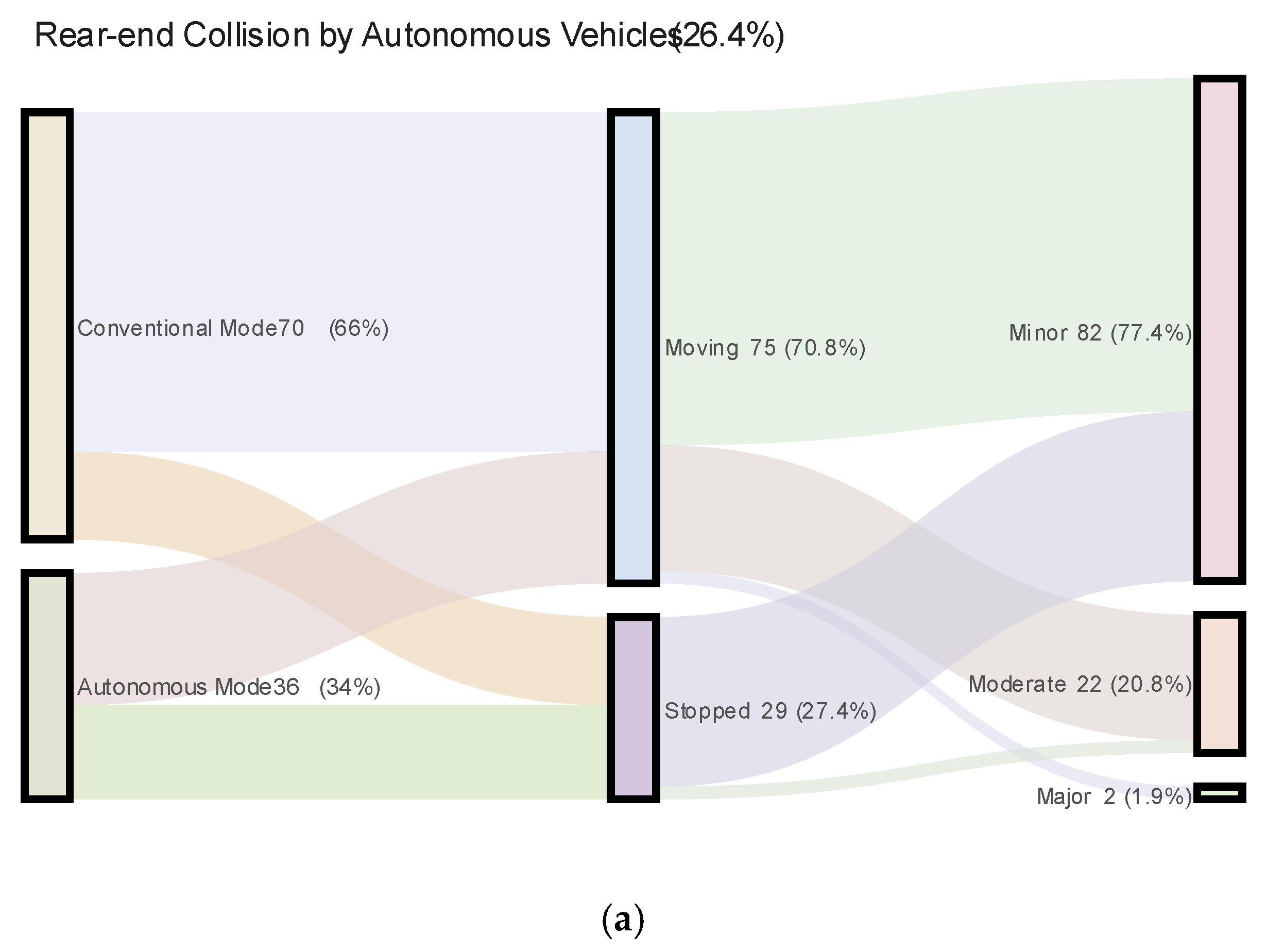

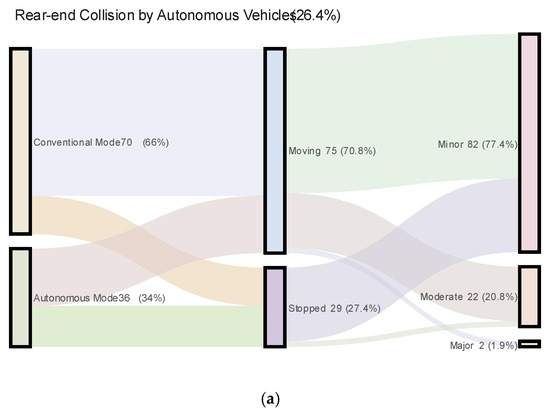

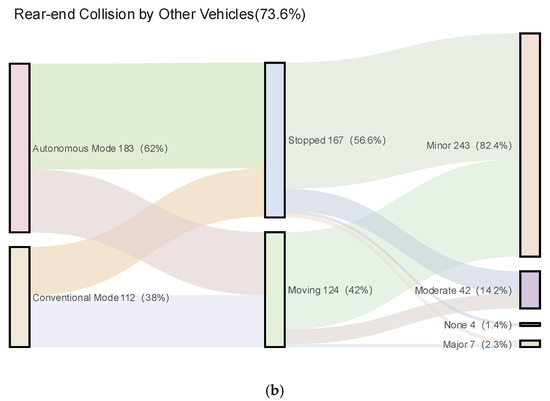

Figure 6 depicts two scenarios associated with ADS rear-end accidents: Figure 6a: ADS striking another vehicle from the rear (106), and Figure 6b: other vehicle striking ADS from the rear (295). The left side of the figure shows the driving mode of the ADS vehicle at the time of the accident, the middle section depicts the vehicle’s motion, and the right side shows the severity of the accident. The values in each section of the graph represent the total number of incidents in that category, and the width of the links connecting the different sections corresponds to the proportional distribution of the subsequent categories. For instance, in Figure 6b, the specifics of a rear-end ADS accident involving another vehicle are shown in detail. The analysis shows that in the case of rear-end accidents involving ADS vehicles, 73.6% of the accidents involved another vehicle hitting the ADS, while 26.4% of the accidents involved the ADS hitting another vehicle. Specifically, among the 124 accidents that occurred when the ADS vehicle was in motion, 105 resulted in minor injuries, 16 in moderate injuries, and 3 in severe injuries. It is worth noting that when the ADS vehicle struck another vehicle in conventional driving mode, the majority of these accidents involved the vehicle in motion. This phenomenon suggests that human drivers are slower to react or may not be able to pay sufficient attention to the road environment to take effective evasive measures in time during an accident, compared to ADS in automatic driving mode.

Figure 6.

Rear-end accident conditions between ADS and Other Vehicles. (a) Rear-end accidents in which ADS hit an HDV from behind. (b) Rear-end accidents in when an HDV hits an ADS from behind.

In terms of accident severity, there were 243 (82.4%) minor injuries in accidents caused by other vehicles hitting ADS vehicles, and 77.4% accidents caused by ADS vehicles hitting other vehicles. It is noteworthy that most of the moderate and severe crashes involving ADS vehicles hitting other vehicles occurred when the vehicle was in conventional driving mode. In addition, 62% of ADS vehicles were in automatic driving mode when another vehicle rear-ended the ADS; conversely, 66% of ADS vehicles were in conventional driving mode when the ADS rear-ended another vehicle. This phenomenon suggests that the likelihood of an ADS vehicle striking a human-driven vehicle (HDV) is higher in conventional driving mode. This may be due to the fact that ADS vehicles use advanced perception and control algorithms in autonomous driving mode, which are more effective in detecting and avoiding obstacles and other vehicles, thus reducing the accident rate.

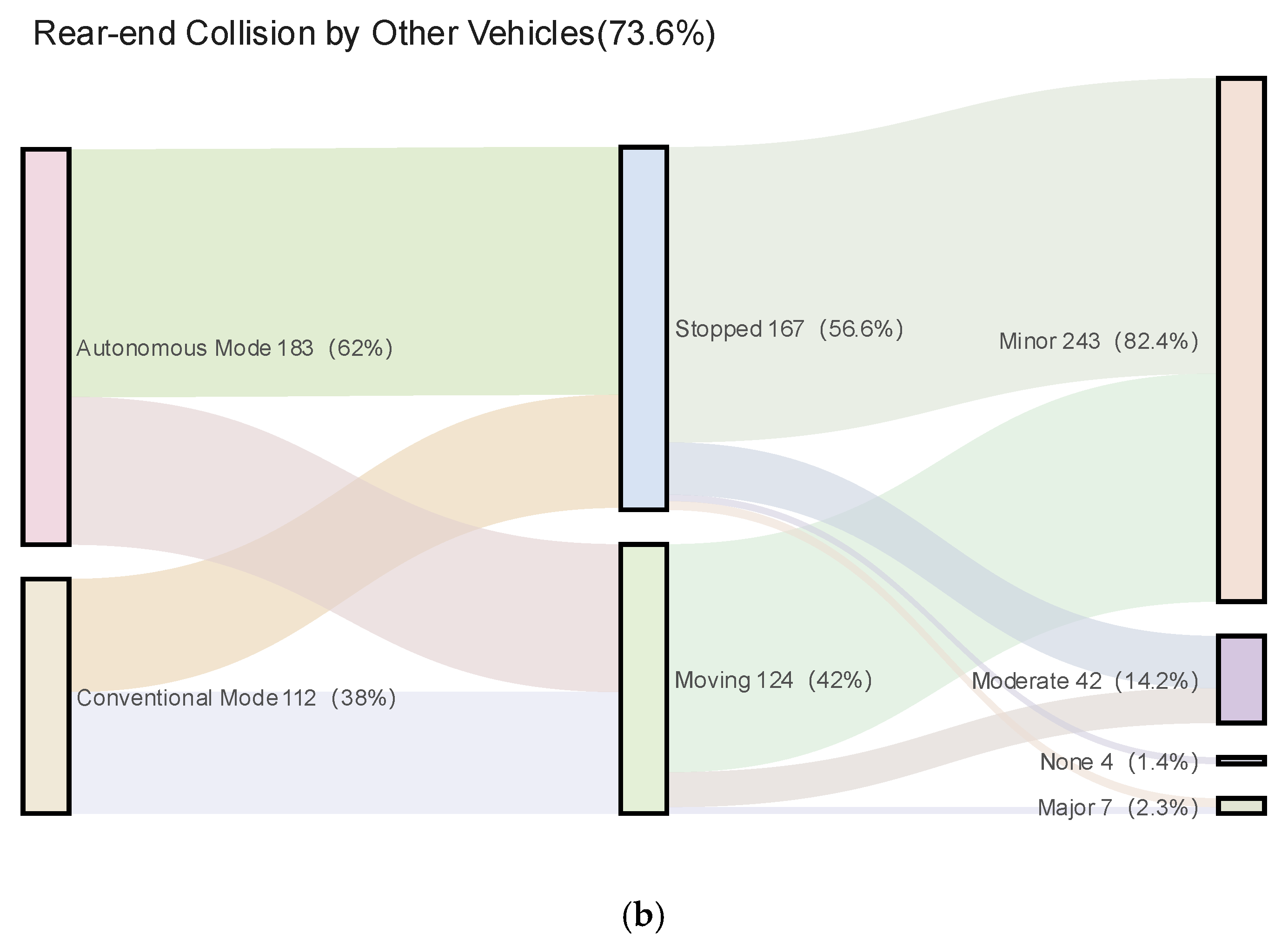

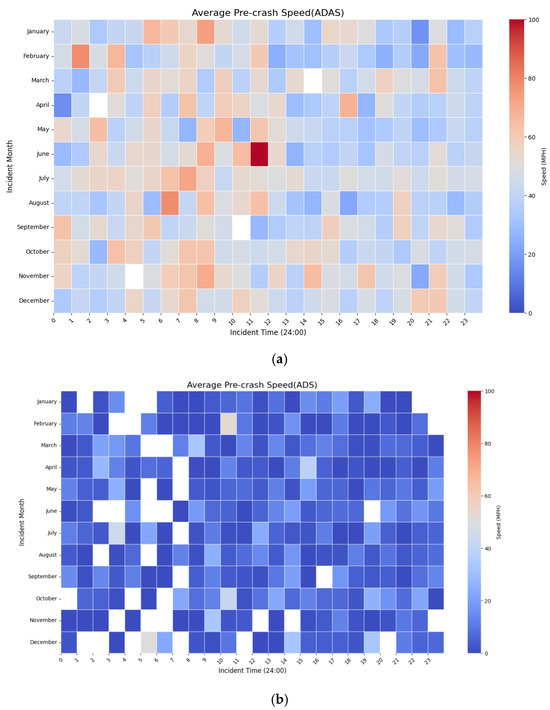

Figure 7 illustrates a heatmap of the pre-accident speed versus time distribution of ADAS and ADS vehicles, with detailed comparisons of speed trends across different months and times of day. The analysis shows that ADAS vehicles are involved in accidents where about 50% of the vehicles have speeds exceeding 40 miles per hour (mph), whereas ADS vehicles are typically involved in accidents with speeds below 40 mph, with about half of these accidents occurring below 20 mph. This phenomenon may be attributed to the fact that ADAS is mainly designed for use in motorway environments, and therefore has a higher average pre-crash speed compared to ADS vehicles. This may be due to the fact that ADAS is primarily designed for use in motorway environments and therefore has a higher average pre-crash speed than ADS vehicles, which are mainly used in complex urban traffic scenarios where pre-crash speeds are lower.

Figure 7.

Distribution of the pre-accident Speed. (a) ADAS Average Pre-crash Speed Heatmap. (b) ADS Average Pre-crash Speed Heatmap.

3.2. Analysis of Influence Factor Association Rules

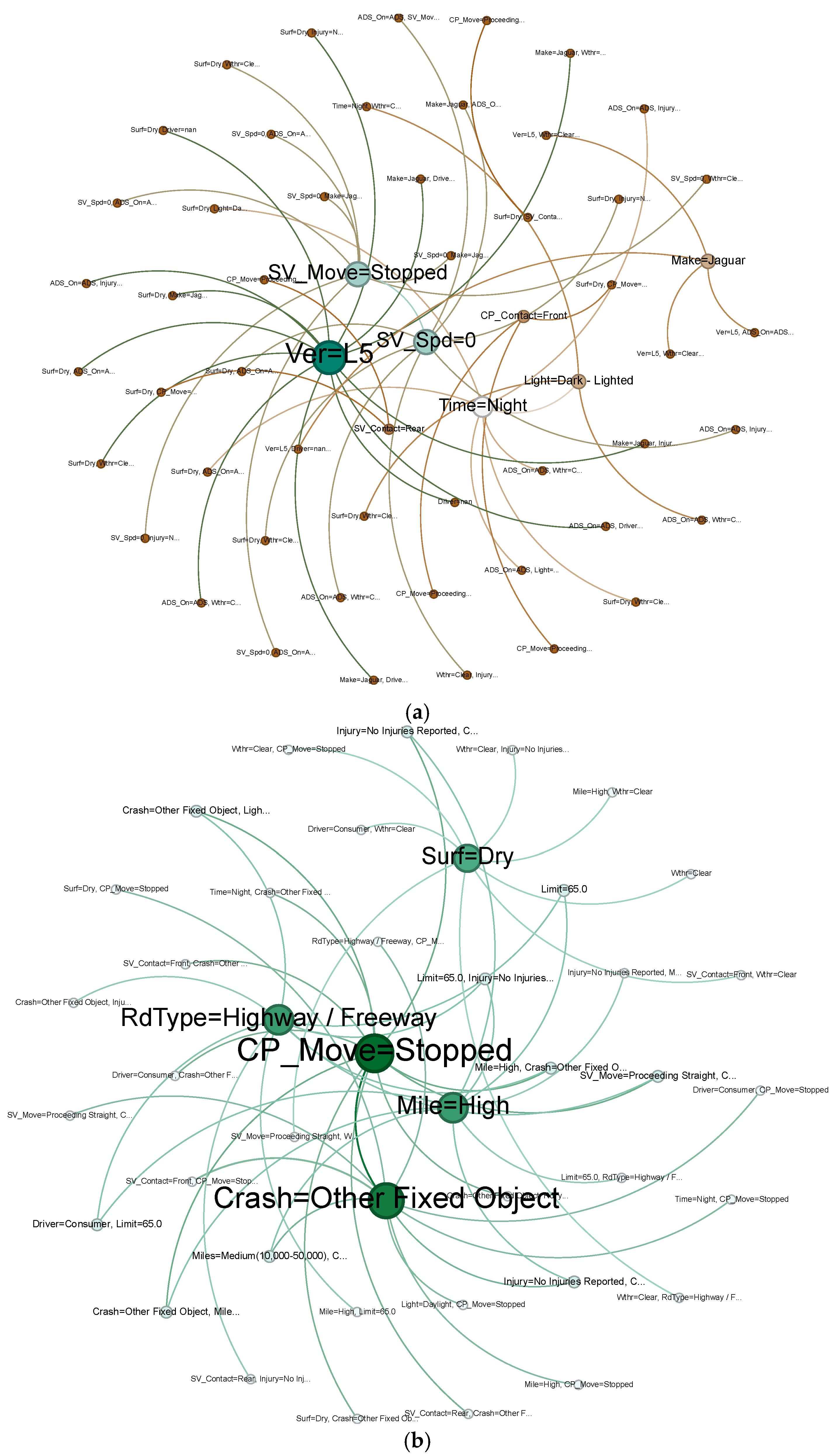

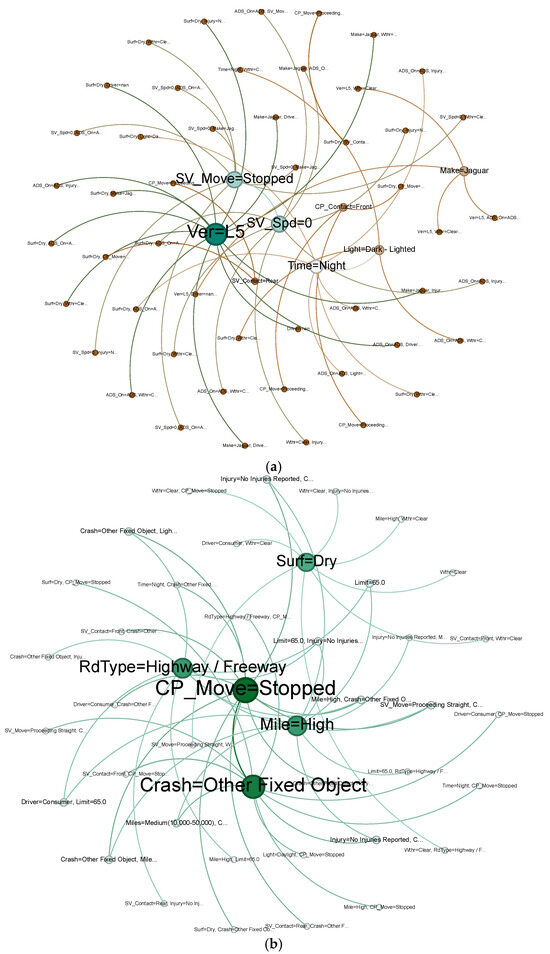

To intuitively synthesize the complex interdependencies among risk factors, we constructed Association rule network graphs for both ADAS and ADS accidents (see Figure 8). These visualizations represent the top 50 strong association rules ranked by Lift, generated using the Gephi software (Version 0.10.1).

Figure 8.

Association rule network graph. (a) ADS accidents; (b) ADAS accidents.

In these graphs, nodes represent specific risk factors (items), and edges represent the association rules connecting antecedents to consequents. The size of a node is proportional to its degree (frequency of appearance in rules), while the color indicates the modularity class (clusters of closely related factors).

These network visualizations transform discrete association rules into a holistic structure, revealing the underlying risk topology of each automation level. By mapping the connectivity among risk factors, the graphs highlight central hubs and natural clustering patterns, thereby facilitating a more intuitive synthesis of how environmental, behavioral, and vehicle factors interact to form complex accident mechanisms.

Detailed quantitative parameters (Support, Confidence, Lift) for specific high-interest rules are listed in Supplementary Material (Tables S1–S4).

3.2.1. Analysis of 2-Item Correlation Rules

This section first conducts a brief analysis using a binary association rule approach to compare the characteristics of ADS and ADAS-related accidents.

Findings show that Level 5 (L5) ADS is primarily linked to minor or non-injury accidents, with the absence of human drivers reducing errors and mitigating severity. While clear weather and dry roads support driving, intersections remain high-risk, especially in low-speed collisions and poor lighting. Notably, ADS accidents peaked in 2021, particularly involving Jaguar’s L5 systems. This trend coincides with the active testing and deployment phases of these vehicles, although exact accident rates cannot be calculated due to the lack of public data on fleet sizes and exposure time.

In contrast, ADAS accidents are highly influenced by surrounding vehicle movements. Rear-end collisions frequently occur when the lead vehicle is stationary, while lane-change and lane-departure accidents are more common on highways, highlighting ADAS limitations in handling sudden maneuvers. ADAS-equipped vehicles are also more prone to collisions with fixed objects in the absence of other vehicles, indicating weaknesses in obstacle detection. Poor lighting further increases accident risk, likely due to sensor limitations, with Tesla’s ADAS vehicles experiencing more incidents under low-light and lane-change scenarios—though mostly non-fatal. Additionally, Tesla’s 2018 models show higher accident frequencies, correlating with market share.

Overall, ADS effectively reduces accident severity under high automation, whereas ADAS remains constrained by perception and response limitations, particularly in low-light conditions and unpredictable maneuvers. These insights provide valuable guidance for optimizing autonomous driving technology.

3.2.2. Analysis of 3-Item Correlation Rules

- (1)

- Analysis of 3-item association rules for ADS accidents (see Table S1).

The two association rules with the highest lift reveal the association between the time of the accident and the ambient lighting conditions. Rules 1 and 2 indicate that ADS vehicles are more likely to be involved in accidents under poor lighting conditions at night, particularly during remote-controlled driving tests, further validating the previous analysis.

Some rules reflect the relationship between the version of the automated driving system and the type of driver. Specifically, in the absence of a driver or with a remote control, the vehicle’s behaviour and the accident outcome exhibit a specific pattern. For example, Rule 6 mentions that in the absence of a driver, a vehicle with an automated driving system version of L5 is more likely to be involved in a collision with a passenger car. This suggests that the decision-making and reaction mechanisms of ADS remain crucial in completely driverless scenarios, and that higher-level ADS (L5) systems may face greater challenges, particularly when interacting with other vehicle types.

Rules 3 and 4 both relate to the motion state of an ADS vehicle before a collision. Self-driving vehicles often take emergency stopping measures when encountering an obstacle, which can lead to rear-end accidents if the following vehicle fails to react in time. Rules 7 and 8 relate to the motion state of other vehicles before the collision. At intersections, other vehicles are mostly moving straight ahead, which corresponds to the previous analysis, and makes rear-end collisions involving ADS more likely.

- (2)

- Analysis of 3-item association rules for ADAS accidents (see Table S2).

The first two rules show that vehicles with odometer readings over 50,000 miles are more likely to be involved in accidents when driven by an average consumer on sunny days, suggesting that vehicle age and wear on key components increase accident probability.

Rule 3 shows that rear-end ADAS accidents often occur when the other vehicle is travelling straight ahead and is involved in a collision, which usually occurs on long straights or motorways; rules 4 and 5 show that rear damage usually occurs when the other vehicle is stopped and involved in an accident, especially at night or when the main vehicle is travelling straight ahead, which also corresponds to rules 11, 15 and 16 in the binomial correlation rule analysis. This also corresponds to rules 11, 15 and 16 in the dichotomous association rule analysis.

Rules 6 and 7 show that frontal vehicle injuries are common on motorways with a 70 mph speed limit. These roads typically have higher speeds and fewer lane changes. Additionally, 30% of ADAS accidents involve vehicles exceeding the speed limit, which limits reaction time for both assisted and manual driving.

3.2.3. Analysis of Association Rules for ADAS and ADS Accident Injuries

- (a)

- Association rules for ADAS accidents with different severity levels (see Table S3).

- (i)

- Association rules for non-damage crashesThe factors involved in the rules for non-damage crashes mainly include road conditions, weather, and vehicle speed. Most of the non-damage crashes involve ADAS vehicles’ forward collisions and occur on motorways or expressways. For example, rules 1 and 2 indicate that when average consumers drive Tesla vehicles and collide with a fixed object while travelling straight on highways, the result is no injury. This suggests that despite the propensity of Tesla vehicles to collide with fixed objects in this common scenario, their overall safety performance during collisions is superior, resulting in generally less severe accident outcomes.Rules 3 and 6 show that under rainy and slippery road conditions, ADAS vehicles colliding with fixed objects on highways or city streets are typically casualty-free. This is related to drivers’ more cautious driving and relatively lower speeds in rainy weather. However, reduced visibility during rain can also impact the performance of assisted driving functions.Rules 4 and 5 state that, at the time of the collision, speeds prior to a no-injury accident are typically in the 20–60 mph range, with the collision location centered on the front of the vehicle. In this case, the lower speed and front crash location can effectively protect the vehicle occupants, resulting in relatively minor accident outcomes.

- (ii)

- Association rules for minor damage accidentsIn the rules involving minor damage accidents, the main influencing factors are accident time, vehicle speed and vehicle mileage accumulated. Rules 7 and 11 show that the probability of accidents occurring in the morning (7:00–11:00) and afternoon (14:00–18:00) is higher, which may be due to the complex road conditions during the morning rush hour, while driver fatigue and reduced attention in the afternoon make it easy for collisions to occur. Compared with the no-casualty scenario (Rule 4), the casualty level in crashes is higher in the afternoon hours for the same speed range (41–60 mph).Rules 8 and 10 indicate that collisions with other vehicles caused by ADAS vehicles travelling straight ahead tend to have a minor damage level when the odometer reading of the ADAS vehicle is low, suggesting that the severity of accidents is relatively low when the vehicle is new, travelling in a straight line, and in a collision with another vehicle. Rule 9 shows that on roads with a road speed limit of 65 mph, accidents with speeds greater than 60 mph at night result in minor injuries. This may be related to drivers paying more attention to road conditions in this situation, while the assisted driving system can also play a role at high speeds.

- (iii)

- Association rules for moderate damage accidentsThe main influencing factors of moderate damage accidents are lighting conditions, vehicle cumulative mileage and speed. Among the rules involving moderate damages, the time of the accident is particularly important, and many of the rules show that accidents occur at night (18:00–7:00) with poor lighting conditions, usually accompanied by collisions with other vehicles. The rules also show that vehicles that have accumulated more than 50,000 miles are more likely to be involved in moderate accidents in similar scenarios. Due to poor visibility at night, reduced driver attention and fatigue, and especially in complex road environments such as intersections, vehicle interactions are prone to misinterpret each other’s intentions, resulting in moderate accidents, and higher mileage also affects the braking performance of the vehicles to a certain extent.

- (iv)

- Association rules for major damage accidentsSevere accidents frequently involve critical factors such as high vehicle speeds and severe collision angles. Notably, these accidents often occur on dry road surfaces, which are typically considered favorable driving conditions. Rules 17 and 19 show that under good weather and road conditions, an accident on a road with a speed limit of 70 mph can lead to serious consequences. In such a simple driving environment, drivers may rely too much on the assistive functions of the ADAS system, ignoring conditions such as the road speed limit and the behavior of other vehicles, which can lead to serious consequences.Rules 18 and 20 further validate this hypothesis, with higher speeds (>60 mph) being the main factor leading to serious accidents. At high speeds, drivers have shorter reaction times in road conditions, and advanced driver assistance systems occasionally fail to respond to complex road conditions in a timely manner, in some cases, thus exacerbating the severity of accidents.

- (b)

- Association rules for ADS accidents with different severity levels (see Table S4).

- (i)

- Association rules for non-damage accidentsNon-damage accidents are one of the more desirable performance situations in ADS accidents. In the association rules from Rule 1 to Rule 7, the key factors mainly include the activation of the autopilot system, the stationary state of the vehicle (speed = 0 prior to the accident), and certain external conditions (e.g., the weather is sunny and the road type is a street). For example, Rules 1 and 4 suggest that when the system operates in Level 5 autonomous driving, accidents at low speeds or when stationary typically result in no injuries or fatalities, especially when the primary cause is the behavior of another vehicle, such as reversing. Rules 2 and 3 show that sunny weather and lower accumulated mileage have a significant influence on accident severity, while the accident occurs on city streets, driving on city streets relative to highways with lower speeds, accidents often do not occur serious injuries, but they are mostly located in residential or commercial areas, road conditions are more complex, increasing the likelihood of accidents.

- (ii)

- Association rules for minor damage accidentsIn the rules related to minor casualty accidents, vehicle speed, driver type, road type and lighting conditions are the key factors for accidents. Rules 8 and 9 show that ADS vehicles can also cause minor injuries when travelling at low speeds (0 or 1–10 mph). Despite the occurrence of collisions, the low speeds typically result in only minor injuries, with the majority of accidents involving rear-end collisions with other vehicles. Rules 9 and 10 describe accidents occurring on city streets, while Rules 12 and 14 describe incidents at intersections. The driver types involved are primarily commercial or testing, suggesting that the ADS still faces adaptability challenges in scenarios requiring multi-agent negotiation. Rule 12 also highlights that the ADS vehicle was in a left-turn state before the accident. Rather than general environmental complexity, this specific maneuver indicates that the system’s perception capabilities face difficulties in predicting the trajectories of oncoming traffic during unprotected turns.

- (iii)

- Association rules for moderate damage accidentsModerate damage accidents, as identified in Rules 16 through 19, are influenced by factors such as higher mileage, faster speeds, and complex road conditions. Rules 16 and 18 state that the probability of a moderate injury is higher when the vehicle has a higher cumulative mileage (>50,000 miles) and occurs on highways, while other vehicles are in a hazardous condition, such as changing lanes prior to the accident. This suggests that as a vehicle’s service life increases, its systems may experience some deterioration in age or performance, resulting in an inability to make optimal decisions in complex environments. Conversely, Rules 17 and 19 reveal that even at lower speeds (11–20 mph), the ADS vehicle’s ability to perceive non-vehicle traffic participants in intersection scenarios remains inadequate. In these scenarios, the interaction complexity arises specifically from the conflict between the ADS vehicle’s path and other motorized vehicles (e.g., motorcycles) or non-motorized vehicles, which can lead to moderate injuries or fatalities.

- (iv)

- Association rules for major damage accidentsMajor damage accidents usually occur under poor lighting conditions and poor weather conditions. Rules 20 through 22 highlight that these incidents primarily involve nighttime or dimly lit scenarios, suggesting that poor lighting and weather conditions with limited visibility directly contribute to an increased likelihood of heavy casualties, even when the ADS vehicles are not traveling at high speeds. In such conditions, both the driver and the ADS are limited in their ability to perceive the environment, preventing timely recognition of obstacles or other traffic participants. For example, Rule 21 describes a collision with a pedestrian resulting in severe injury or death. Additionally, similar to other severity-related rules, heavy casualty accidents also involve scenarios where the ADS vehicle is rear-ended by another vehicle, indicating that the ADS lacks sufficient ability to sense the state of following vehicles and is unable to take timely evasive actions to mitigate the potential consequences of the accident.

4. Discussion

Based on the association rules identified in the previous section, this chapter interprets the causal mechanisms of accidents, compares the safety limitations of different automation levels, and proposes potential countermeasures.

4.1. Divergent Operational Domains and Failure Mechanisms

The statistical disparity between ADAS and ADS accidents is not merely coincidental but stems from their fundamentally different Operational Design Domains (ODDs) and human–machine divisions of responsibility. While ADAS accidents are concentrated on motorways and straight roads, this aligns with the system’s primary use case—relieving driver fatigue during monotonous driving. However, this convenience introduces the “irony of automation”: as the system handles routine tasks effectively, driver vigilance decays. The high prevalence of high-speed, frontal collisions in ADAS vehicles suggests that when the system disengages or fails, drivers are often mentally “out-of-the-loop,” leading to delayed reaction times that preclude effective evasion. Conversely, the concentration of ADS accidents at intersections and in low-speed scenarios reflects the technological bottleneck of trajectory prediction. Although ADS sensors offer 360-degree perception, the algorithmic conservatism designed to prioritize safety often conflicts with the stochastic, aggressive nature of human traffic. The finding that ADS vehicles are frequently rear-ended while stationary or moving slowly indicates a “behavioral mismatch”: the ADS’s rigid adherence to safety margins is perceived as unexpected or obstructive by following human drivers, resulting in collisions where the ADS is technically not at-fault but causally significant.

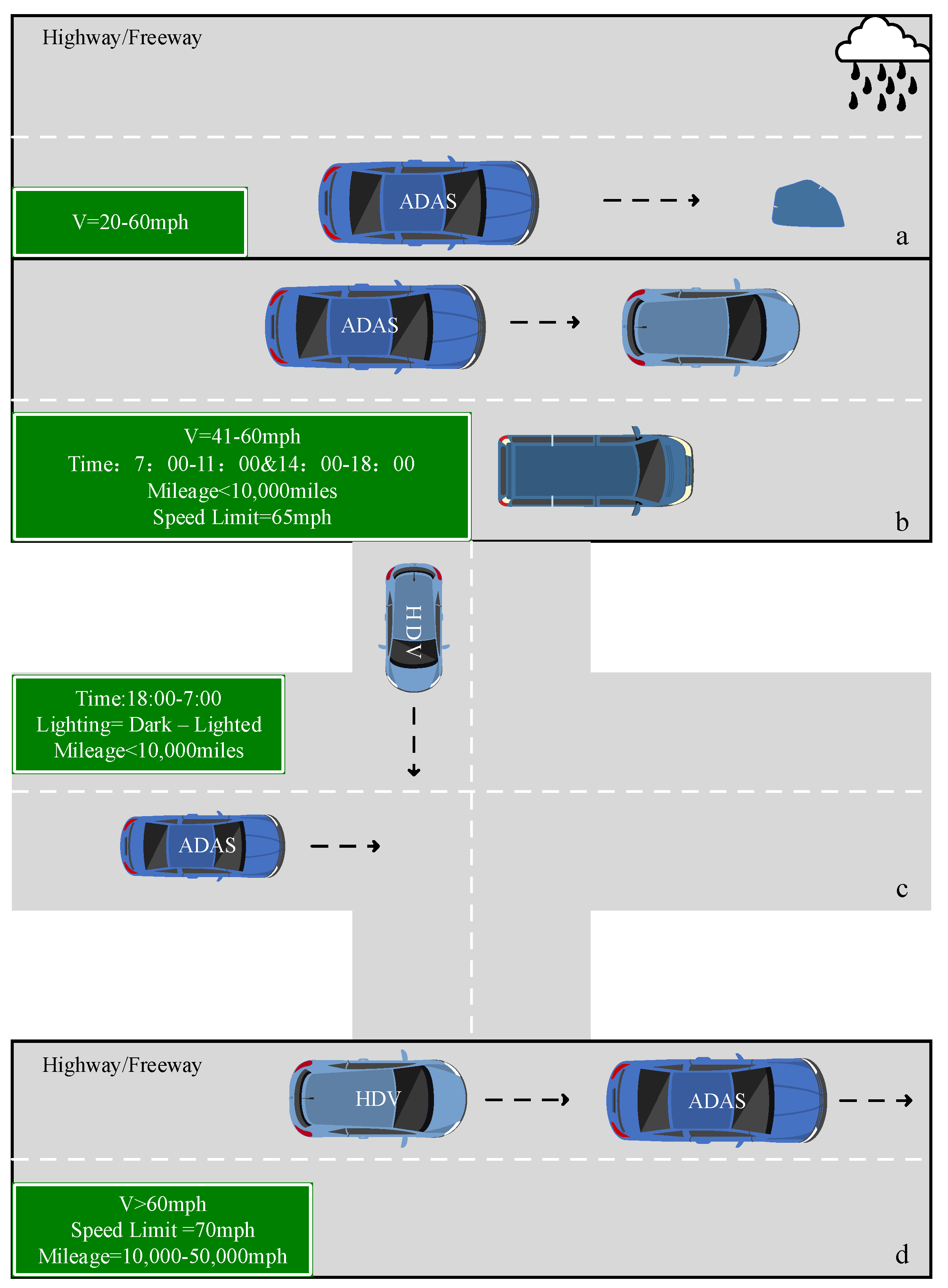

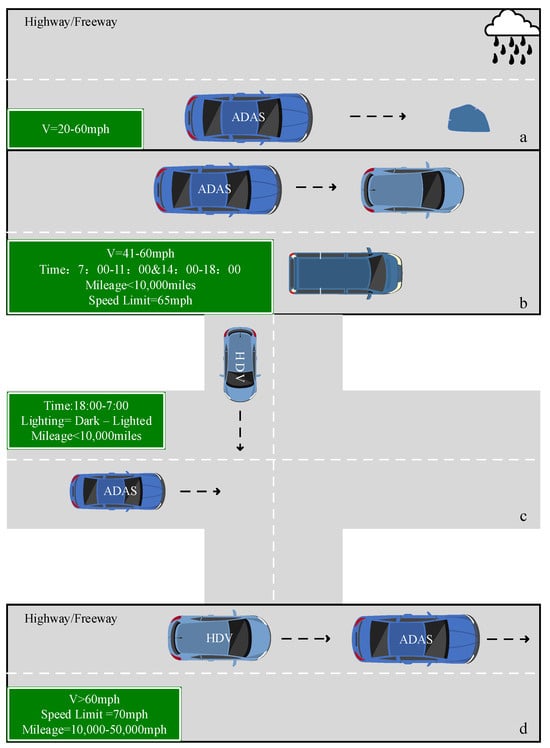

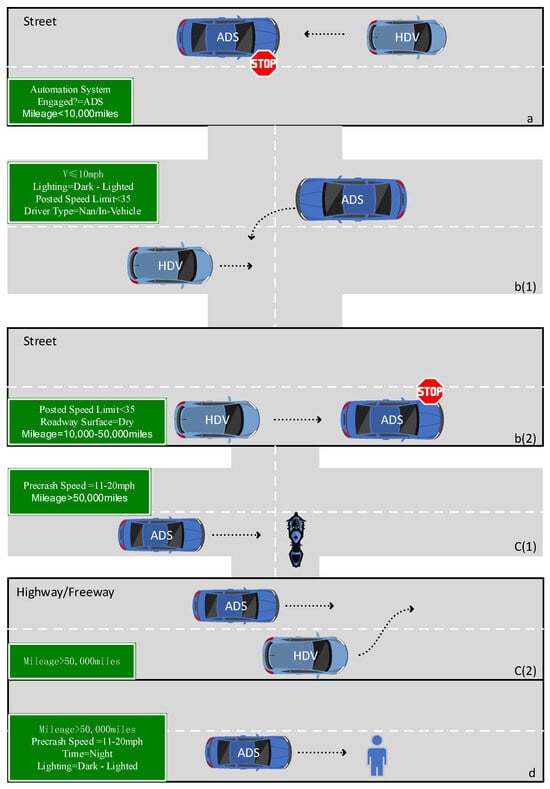

4.2. Environmental Constraints and Sensor Limitations in ADAS

The ARM results for ADAS reveal a critical dependency on environmental clarity. As visualized in the scenario reconstructions (Figure 9), distinct failure modes emerge across severity levels, directly correlating with sensor limitations. The strong association between ADAS failure and poor lighting/adverse weather corroborates the physical limitations of camera-based perception systems. In lower-severity scenarios (Figure 9a,b), accidents often involve collisions with obstacles or rear-end events on highways during rain. This pattern highlights the “visual noise” challenge: rain spray and low-contrast obstacles (like debris) can confuse vision-based algorithms, leading to phantom braking or failure to detect stationary objects. Unlike the multi-sensor fusion (LiDAR/Radar) often found in L4 test vehicles, consumer ADAS relies heavily on visual contrast. Consequently, in low-light or glare conditions, the system’s confidence drops. This is critically evident in the moderate and major damage scenarios (Figure 9c,d), which frequently occur at dark intersections or involve high-speed interactions. Here, the system implicitly shifts the dynamic driving burden back to the driver—often without sufficient warning time.

Figure 9.

ADAS Accident Scenarios. (a) No damage. (b) Minor injury. (c) Moderate damage. (d) Major damage.

Furthermore, the severity of ADAS accidents is exacerbated by the “false sense of security.” The correlation between “none/minor” injuries and “road obstacles” suggests that in low-speed, complex environments, drivers remain alert. However, as shown in Figure 9d, the link between severe injuries and high-speed motorway scenarios implies that drivers over-trust the system precisely when the kinetic energy (and thus risk) is highest. This necessitates a shift in design philosophy from solely improving sensor accuracy to implementing more robust Driver Monitoring Systems (DMS) that prevent engagement in unsuitable environmental conditions.

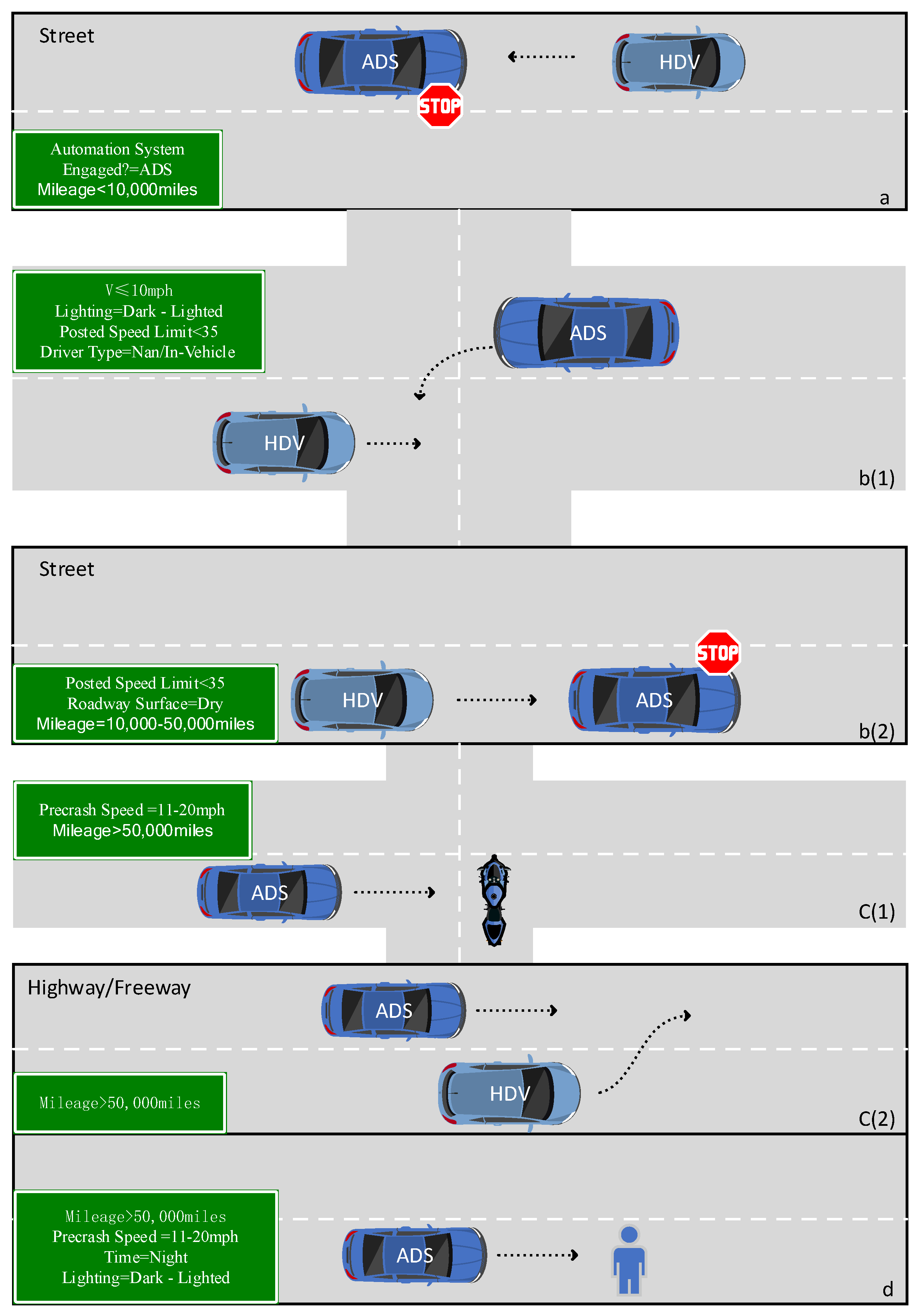

4.3. Interaction Challenges and Vulnerabilities in ADS

For ADS (L3+), the analysis highlights that safety challenges have shifted from “detection” to “prediction and interaction.” The visual scenarios in Figure 10 corroborate these interactional deficits, revealing a clear dichotomy between passive failures and active recognition errors. While the data shows ADS performs well in reducing self-induced errors, the high incidence of accidents involving interactions with other vehicles exposes the difficulty of modeling human intent. Low-severity incidents (Figure 10a,b) are dominated by “passive” collisions where the ADS is rear-ended while yielding at stop signs or executing conservative turns. This confirms a “behavioral mismatch”: the ADS’s rigid adherence to safety margins is perceived as unexpected or obstructive by following human drivers, resulting in collisions where the ADS is technically not at-fault but causally significant.

Figure 10.

ADS Accident Scenarios. (a) No damage. (b) Minor injury. (c) Moderate damage. (d) Major damage.

The progression to major severity (Figure 10c,d) reveals a more disturbing pattern involving Vulnerable Road Users (VRUs). As depicted in Figure 10d, the specific scenario of an ADS striking a pedestrian in low-light conditions serves as a stark reminder that “detecting” an object is distinct from “predicting” its risk. While LiDAR works well in the dark, classifying the trajectory of erratic biological targets (like pedestrians or the motorcycle in Figure 10c) remains a challenge. The system may detect the object but fail to correctly anticipate its future position, leading to defensive braking or delayed evasion that causes chain-reaction accidents.

Moreover, the observation that vehicles with higher mileage are involved in specific severe failure modes suggests a potential “sensor degradation” or “calibration drift” issue that is rarely discussed in the current literature. As fleets age, the maintenance of sensor fidelity becomes as critical as the software logic itself. Therefore, the finding implies that long-term reliability protocols are essential to prevent the “performance degradation” of ADS over its lifecycle.

4.4. Summary

In summary, the transition from ADAS to ADS represents a shift in risk topology. ADAS risks are rooted in human factors—specifically, the degradation of situational awareness due to over-reliance. In contrast, ADS risks are rooted in interactional factors—specifically, the dissonance between conservative algorithmic planning and aggressive human driving norms. Future safety strategies must therefore decouple: ADAS requires better human-centric monitoring, while ADS requires more socially compliant behavioral algorithms to integrate smoothly into mixed traffic.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted a comparative investigation into the causal mechanisms of accidents involving Advanced Driver Assistance Systems (ADAS, L2) and Automated Driving Systems (ADS, L3+). By leveraging association rule mining, the research successfully disentangled the complex interdependencies among environmental, behavioral, and technical factors.

The results indicate that the safety dynamics of L2 and L3+ technologies are fundamentally divergent. ADAS risks are predominantly driven by “automation complacency” in high-speed environments, where sensor limitations (e.g., visual noise in adverse weather) interact with driver over-reliance to precipitate accidents. In contrast, ADS risks are characterized by a “behavioral mismatch” in complex urban interactions, where the system’s conservative decision-making logic conflicts with aggressive human driving norms, leading to a high frequency of passive rear-end collisions.

These findings have critical implications for safety strategies, necessitating a decoupled approach: ADAS development must prioritize robust Driver Monitoring Systems (DMS) to mitigate vigilance decrement in monotonous scenarios, whereas ADS evolution requires socially compliant algorithms and enhanced prediction capabilities to resolve conflicts with Vulnerable Road Users (VRUs). Furthermore, the application of interpretable association rule mining demonstrates a methodological advantage over black-box models, uncovering non-linear causal structures that traditional statistics overlook.

Future work should integrate large-scale naturalistic driving datasets and advanced simulation frameworks to capture real-time behavioral adaptation and sensor degradation effects. From a policy perspective, frameworks should evolve toward standardized, transparent reporting mechanisms that facilitate cross-level safety benchmarking. Through the combined advancement of intelligent system design and regulatory oversight, this study contributes to a more reliable and human-centered trajectory toward full automation.

6. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights into the distinct accident mechanisms of ADAS and ADS, several limitations driven by data availability and methodological constraints must be acknowledged.

First, a primary constraint is the lack of exposure data (e.g., Vehicle Miles Traveled, fleet size, or operational hours) in public datasets. Consequently, this study focuses on characterizing accident patterns conditional on a crash occurring, rather than calculating normalized accident rates. This limitation also confounds the interpretation of temporal trends, as the prevalence of specific model years (e.g., 2021 models) may reflect deployment intensity rather than inherent system immaturity.

Second, the dataset lacks granular information regarding real-time traffic density and vehicle technical specifications. Due to commercial confidentiality, specific sensor configurations (e.g., LiDAR vs. camera-only) and software/firmware versions are not disclosed. Therefore, “accumulated mileage” serves only as an aggregate proxy for vehicle usage, and we could not disentangle the effects of hardware wear from software updates or maintenance history. Similarly, the “complexity” of accident scenarios discussed herein refers to maneuver-object interactions rather than quantitative traffic flow intensity.

Third, from a methodological perspective, the extreme sparsity of fatal accident samples necessitated the aggregation of “Severe” and “Fatal” injuries into a single category. This trade-off was essential to ensure sufficient support for the Apriori algorithm and to guarantee the statistical stability of the extracted rules.

Finally, it is important to note that Association Rule Mining identifies strong correlations and co-occurrence patterns, which, while highly indicative of risk mechanisms, do not establish strict counterfactual causality. Future research should aim to integrate naturalistic driving data and maintenance logs to address these gaps and provide a more holistic safety assessment.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/app152413146/s1, Table S1: List of the best 10 association rules in 3-item for ADS crashes; Table S2: List of the best 10 association rules in 3-item for ADAS crashes; Table S3: List of the best 20 association rules for different accident severities in ADAS crashes; Table S4: List of the best 22 association rules for different accident severities in ADS crashes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: J.Z.; Data curation: S.J.; Investigation: S.J.; Methodology: S.J.; Visualization: S.J.; Writing—original draft: S.J.; Supervision: J.Z.; Writing—review and editing: J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the State Key Lab of Intelligent Transportation System under Project no 2025-B008 and the Postgraduate Quality Professional Degree Teaching Case Base of Shandong Province under Grant no SDYAL2024030.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets supporting the findings of this study are available at https://www.nhtsa.gov/laws-regulations/standing-general-order-crash-reporting (accessed on 20 June 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- World Health Organization. Global Status Report on Road Safety 2023: Summary; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Tesla: 2022 Q4 Quarterly Update. Tesla. 2022. Available online: https://digitalassets.tesla.com/tesla-contents/image/upload/IR/TSLA-Q4-2022-Update (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- People’s Daily Online. 2024 Intelligent Internet Blue Book: China’s Assisted Driving Passenger Car Market Penetration Rate Reaches 47.3%. People’s Daily Online, 24 June 2024. Available online: http://yjy.people.com.cn/n1/2024/0620/c244560-40260730.html (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Stewart, J. Why Tesla’s Autopilot Can’t See a Stopped Firetruck. 2018. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/tesla-autopilot-why-crash-radar/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Marshall, A. The Uber Crash Won’t Be the Last Shocking Self-Driving Death. Wired. 2018. Available online: https://www.wired.com/story/uber-self-driving-crash-explanation-lidar-sensors/ (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- SAE J3016™; Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to On-Road Motor Vehicle Automated Driving Systems. SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2021.

- Houseal, L.A.; Gaweesh, S.M.; Dadvar, S.; Ahmed, M.M. Causes and effects of autonomous vehicle field test crashes and disengagements using exploratory factor analysis, binary logistic regression, and decision trees. Transp. Res. Rec. 2022, 2676, 571–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Barbour, N.; Wang, D.; Wang, Z.; Zheng, O. Exploratory analysis of injury severity under different levels of driving automation (SAE Levels 2 and 4) using multi-source data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 206, 107692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Q.; Xu, M. Heterogeneity in crash patterns of autonomous vehicles: The latent class analysis coupled with multinomial logit model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 209, 107827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, R.; Li, S. Exploring the associations between driving volatility and autonomous vehicle hazardous scenarios: Insights from field operational test data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 166, 106537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.; Zhang, G.; Huang, H.; Wei, Z.; Zhou, H.; Jin, J.; Chang, F.; Chen, J. How would autonomous vehicles behave in real-world crash scenarios? Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 202, 107572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novat, N.; Kidando, E.; Kutela, B.; Kitali, A.E. A comparative study of collision types between automated and conventional vehicles using Bayesian probabilistic inferences. J. Saf. Res. 2023, 84, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channamallu, S.S.; Kermanshachi, S.; Pamidimukkala, A. Impact of autonomous vehicles on traffic crashes in comparison with conventional vehicles. In Proceedings of the ASCE International Conference on Transportation & Development, Austin, TX, USA, 14–17 June 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Huang, C.; Jian, S.; He, D. Analysis of discretionary lane-changing behaviours of autonomous vehicles based on real-world data. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2023, 21, 2288636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, P.F.; Hsu, W.T.; Lord, D.; Put, I.G.B. Classification of autonomous vehicle crash severity: Solving the problems of imbalanced datasets and small sample size. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 205, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashraf, M.T.; Dey, K.; Mishra, S.; Rahman, M.T. Extracting rules from autonomous-vehicle-involved crashes by applying decision tree and association rule methods. Transp. Res. Rec. 2021, 2675, 522–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.K.H.; Leung, E.K.H.; Tse, Y.K.; Tsao, Y.C. Investigating collision patterns to support autonomous driving safety. Enterp. Inf. Syst. 2024, 18, 2243460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Meng, Q. What can we learn from autonomous vehicle collision data on crash severity? A cost-sensitive CART approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 174, 106769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutela, B.; Das, S.; Dadashova, B. Mining patterns of autonomous vehicle crashes involving vulnerable road users to understand the associated factors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 165, 106473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohanpour, E.; Davoodi, S.R.; Shaaban, K. Analyzing autonomous vehicle collision types to support sustainable transportation systems: A machine learning and association rules approach. Sustainability 2024, 16, 9893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Chen, H.; Zhou, R.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X. Exploring the mechanism of crashes with autonomous vehicles using machine learning. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, e5524356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Guo, Y.; Liu, P.; Ding, H.; Cao, J.; Zhou, J.; Feng, Z. What can we learn from the AV crashes?—An association rule analysis for identifying the contributing risky factors. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 199, 107492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aty, M.; Ding, S. A matched case-control analysis of autonomous vs human-driven vehicle accidents. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoner, J.; Sanders, R.; Goddard, T. Effects of advanced driver assistance systems on impact velocity and injury severity: An exploration of data from the crash investigation sampling system. Transp. Res. Rec. 2023, 2678, 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seacrist, T.; Maheshwari, J.; Sarfare, S.; Chingas, G.; Thirkill, M.; Loeb, H.S. In-depth analysis of crash contributing factors and potential ADAS interventions among at-risk drivers using the SHRP 2 naturalistic driving study. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2021, 22, S68–S73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niebuhr, T.; Junge, M.; Achmus, S. Expanding pedestrian injury risk to the body region level: How to model passive safety systems in pedestrian injury risk functions. Traffic Inj. Prev. 2015, 16, 519–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradloo, N.; Mahdinia, I.; Khattak, A.J. Safety in higher-level automated vehicles: Investigating edge cases in crashes of vehicles equipped with automated driving systems. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 203, 107607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.; Vu, V.; Chand, S.; Wijayaratna, K.; Dixit, V. A crash injury model involving autonomous vehicle: Investigating crash and disengagement reports. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattak, Z.H.; Fontaine, M.D.; Smith, B.L. Exploratory investigation of disengagements and crashes in autonomous vehicles under mixed traffic: An endogenous switching regime framework. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 7485–7495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agrawal, R.; Mannila, H.; Srikant, R.; Toivonen, H.; Verkamo, A.I. Fast discovery of association rules. Adv. Knowl. Discov. Data Min. 1996, 12, 307–328. [Google Scholar]

- Montella, A. Identifying crash contributory factors at urban roundabouts and using association rules to explore their relationships to different crash types. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2011, 43, 1451–1463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montella, A.; Aria, M.; D’Ambrosio, A.; Mauriello, F. Analysis of powered two-wheeler crashes in Italy by classification trees and rules discovery. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2012, 49, 58–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).