Abstract

This study evaluates the morphological performance of the CardioBAN wearable electrocardiogram (ECG) device by comparing its beat-level waveform accuracy against a clinically certified reference system (GE Vivid E9). A cycle-by-cycle Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) analysis was employed to assess beat-level waveform similarity between both devices in 17 healthy participants under controlled conditions. Each cardiac cycle from CardioBAN was aligned to its reference counterpart, enabling a fine-grained comparison of waveform shape. The resulting DTW distances (mean 0.493 ± 0.166) demonstrated overall high morphological agreement, with lower values occurring in recordings with stable beat morphology and higher values primarily reflecting normal variability related to minor motion artifacts or electrode–skin impedance fluctuations. A complementary Bland–Altman analysis of point-wise amplitude differences after DTW alignment showed minimal bias (0.079) and narrow limits of agreement (−0.897–1.055), confirming strong amplitude concordance between systems. These findings indicate that the CardioBAN wearable reliably reproduces key ECG morphological features under controlled, short-term recording conditions. Further studies encompassing ambulatory environments and clinical populations are needed to evaluate its suitability for real-world and pathological scenarios.

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 19.8 million people died from CVDs in 2022 [1]. Early detection and treatment of CVDs can significantly reduce the risk of complications and improve the overall quality of life. Monitoring cardiovascular signals such as heart rate, blood pressure, and electrocardiogram (ECG) can provide valuable information about the heart’s health and functioning [2].

Biosignals play a crucial role in medical diagnostics, as they provide real-time information about an individual’s physiological state. Among these, the electrocardiogram (ECG) remains the gold standard for cardiac monitoring, allowing the detection of arrhythmias, conduction disorders, and ischemic events [3,4]. In addition, heart rate variability (HRV) provides insights into autonomic nervous system activity, making it a key indicator of cardiovascular health [5,6,7].

Nowadays, medicine relies heavily on the measurements of several biomedical signals. These biosignals have their own characteristics (nature and sensors used), which can pose difficulties in their correct interpretation. Therefore, biosignals require thorough preprocessing before analysis. This processing is usually carried out utilizing hardware (initial conditioning stages) and software, which is increasingly employed [8].

Importantly, unlike most wearable systems that operate as closed solutions and only communicate with proprietary applications, the CardioBAN (Product page: https://www.pluxbiosignals.com/products/cardioban, accessed on 30 September 2023) wearable, as well as other Plux technologies, allows integration with external applications, offering greater flexibility for research, clinical implementation, and interoperability with customized health monitoring platforms.

Although wearable devices have great potential for real-time health monitoring, concerns remain about their accuracy and reliability in medical applications [9]. Evaluating their performance against clinically certified devices is essential to ensure their validity in critical healthcare settings. Despite the growing availability of wearable technologies, relatively few studies have conducted a detailed validation of ECG morphology against gold-standard certified systems, leaving a relevant gap in the literature. To assess their accuracy, it is essential to compare their measurements with those of certified clinical equipment [9,10,11,12,13]. The COVID-19 pandemic has reinforced the importance of continuous health monitoring by exposing the limitations of traditional, episodic healthcare and underscoring the need for remote, real-time patient assessment. Consequently, individuals have become more aware of their personal health status and have increasingly adopted wearable medical devices that enable continuous monitoring of vital signs and support the early detection of health conditions, particularly cardiovascular diseases [14,15]. In this context, validating wearable devices such as the CardioBAN wearable is particularly relevant, as it supports the advancement of telemedicine, remote patient monitoring, and early cardiovascular risk detection, thus addressing both clinical and societal needs.

This study aims to evaluate the accuracy and morphological fidelity of ECG waveforms obtained from a wearable device (CardioBAN) by comparing them with recordings from a clinically certified system (GE Vivid). The GE Vivid E9 (Product page: https://www.vividechoclub.net/emea/generalnews?id=172, accessed on 30 September 2023) (GE Healthcare, Chicago, IL, USA), a hospital-grade echocardiography system capable of high-fidelity multi-lead ECG acquisition, is widely recognized as a clinical reference standard and was therefore selected for this study. The comparison was performed using DTW (Dynamic Time Warping) to analyze signal alignment and morphological variations.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of the related literature relevant to this study. Section 3 describes the methodological framework, including data processing, temporal alignment, and analytical workflow. Section 4 reports the experimental results. Section 5 presents a critical discussion of the findings. Section 6 concludes the paper with final remarks and perspectives for future work.

2. Background

Validation Approaches for Wearable Devices

The validation of wearable devices for cardiovascular monitoring commonly relies on comparison with clinically certified systems using established statistical frameworks. Typical approaches include Bland–Altman analysis, intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC), correlation metrics, and diagnostic accuracy indicators such as sensitivity, specificity, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves [16,17,18].

Conventional statistical metrics generally provide only a global measure of agreement between two measurement systems and do not typically capture small, localized differences in ECG waveform morphology. Such differences may arise from natural physiological variability, motion artifacts, or device-dependent timing fluctuations, which can lead to misleading correlations when only global agreement is assessed. In these situations, alignment-based approaches such as DTW provide a more appropriate framework for assessing signal fidelity. DTW performs elastic temporal alignment between two sequences, enabling cycle-by-cycle comparison while preserving local morphological features that may be lost using global statistical indicators [19,20]. Beyond biomedical applications, DTW is a well-established method in time-series analysis, widely used in pattern recognition and speech processing [21], as well as in time-series clustering and biomedical data mining [22]. Its relevance in ECG research is further supported by successful applications in robust R-peak detection [23], arrhythmia discrimination [24], and ventricular tachyarrhythmia prediction [25], reinforcing DTW as a suitable morphology-sensitive metric for waveform-level validation.

Recent studies illustrate the diversity of approaches adopted when validating wearable sensing technologies. Many investigations rely on controlled cohorts of healthy volunteers, a common strategy in early-phase validation. For example, Bent et al. (2020) [26] evaluated optical heart-rate sensors in 56 healthy adults and reported that movement and skin pigmentation were major sources of variability. Costa et al. (2023) [27] tested the multimodal HowMI wearable in 30 healthy participants and found high agreement for heart rate but lower accuracy for peripheral temperature and SpO2. Matouq et al. (2025) [28] assessed a low-power PPG-based wearable in 20 young adults, demonstrating good correspondence with smartwatch-derived heart-rate measurements. Yuda et al. (2025) [29] conducted a preliminary evaluation of a wearable ECG system in 12 healthy males, reporting strong heart-rate consistency with a Holter reference. As summarised in Table 1, the small-sample studies outlined above provide the most suitable methodological reference point for early-phase assessments of physiological fidelity and waveform accuracy in wearable-device validation.

Table 1.

Summary of validation studies of wearable sensors with small cohorts of healthy volunteers.

By contrast, large-scale population studies, such as those by Bumgarner et al. (2018) [30] and Perez et al. (2019) [31], have focused mainly on arrhythmia detection and irregular-pulse screening rather than waveform-level signal validation.

3. Methodology

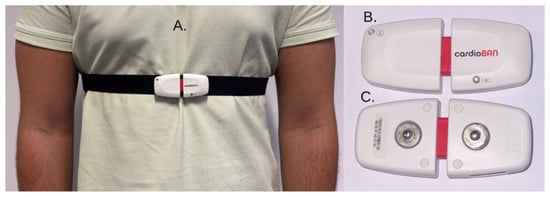

This study was conducted at the 2Ai—Laboratory of Applied Artificial Intelligence, located at the School of Technology, Polytechnic University of Cávado and Ave. The CardioBAN wearable device, developed by PLUX Biosignals (Lisbon, Portugal), was compared with the GE Vivid E9 ultrasound machine (GE HealthCare, Wauwatosa, WI, USA), a clinically certified system widely used in hospital settings (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Illustration of the CardioBAN wearable Device (PLUX Biosignals, Lisbon, Portugal). (A) Device positioned on the chest using the elastic strap. (B) Frontal view of the device. (C) Rear view of the device, highlighting the snap connectors for attachment to the chest strap.

3.1. Devices

The CardioBAN is a wireless, single-lead wearable device developed by PLUX Biosignals (Lisbon, Portugal) for reliable short-term acquisition of raw electrocardiography (ECG) and motion data. The device integrates a single-lead ECG sensor, a triaxial accelerometer, and a triaxial magnetometer within a compact housing (28 mm × 70 mm × 12 mm; 25 g), enabling comfortable and discrete use in both in-lab and out-of-lab research environments. It supports data acquisition at sampling rates of up to 1000 Hz with 8-bit or 16-bit resolution per channel and transmits data via Bluetooth Class II and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) with an approximate range of 10 m. According to its Declaration of Conformity, CardioBAN is intended exclusively for life science research and educational purposes and is not certified for medical use, although it complies with essential European safety and electromagnetic compatibility directives (RED 2014/53/EU, EMC 2014/30/EU, RoHS 2011/65/EU). Data were collected using the OpenSignals (r)evolution software (release OS 07032022; PLUX Biosignals, Lisbon, Portugal) interface provided by PLUX.

Compared with mainstream wearable devices such as the Apple Watch, the CardioBAN provides direct access to raw single-lead ECG signals at high sampling frequencies (up to 1000 Hz), allowing precise beat-level waveform analysis. The CardioBAN’s research-grade design, chest-mounted electrode placement, and full data transparency make it particularly suitable for scientific studies focused on ECG morphology and signal fidelity.

The GE Vivid E9 is a clinically certified echocardiography system widely used in hospitals for high-resolution cardiac imaging and synchronized ECG acquisition. In this study, only the ECG acquisition module was used as the clinical reference device. Three disposable Ag/AgCl electrodes with solid gel were used for ECG acquisition. Electrodes were positioned near the right and left clavicles and below the left chest, following the configuration typically employed during echocardiographic recordings with the GE Vivid E9 [32]. This placement ensured stable signal quality and minimized motion artifacts during acquisition. The Vivid E9 is a CE-marked and FDA-cleared cardiac ultrasound system widely used in clinical practice for high-quality echocardiographic imaging and functional cardiac assessment.

3.2. Participant Recruitment and Data Collection Procedure

Seventeen participants were recruited for this study, all of them without any previously diagnosed cardiac pathology. Although no universally established reference values exist for DTW in ECG validation studies, the required sample size was estimated using the standard Bland–Altman precision formula. The final sample consisted of 11 males and 6 females, aged between 22 and 31 years (mean = 26 ± 2.3 years), all of Portuguese nationality and in self-reported good health. The final sample had a mean age of 26 years, thus representing a healthy young adult population. To be eligible, individuals were required to be at least 18 years old and to possess full cognitive and motor capabilities, with no use of medication, alcohol, or recreational drugs that could interfere with cardiovascular activity. Each participant read and signed an informed consent document, which detailed the scope of the research, the data collection procedures, and their rights regarding confidentiality.

Following informed consent, ECG signal acquisition was performed using both devices, first with the CardioBAN wearable device, followed by the GE Vivid E9 ultrasound machine. During the first phase, an elastic band was placed around the chest to properly position the CardioBAN sensors, after which three electrodes of the GE Vivid E9 were applied to ensure the simultaneous recording of the same cardiac signal. Participants were asked to provide their age, which was recorded for statistical purposes and to confirm that they were fully conscious and aware during the data acquisition process. All recordings took place in a controlled environment at 2Ai, with the participant alone and accompanied only by the responsible researcher, ensuring procedural accuracy and minimizing external interference. To maintain signal consistency and data integrity, participants were instructed to remain seated in a relaxed state throughout the recording, avoiding unnecessary movement of the arms or trunk, although they were allowed to speak normally.

All data were coded using numerical identifiers, with no personal information retained, thereby preventing any direct linkage between participants and their responses. Access to the dataset was restricted solely to the researcher conducting the study. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of 2Ai–IPCA (approval code: 2AIEC002-2023), on 12 December 2023, by institution where the research was conducted.

3.3. ECG Data Processing and Analysis Pipeline

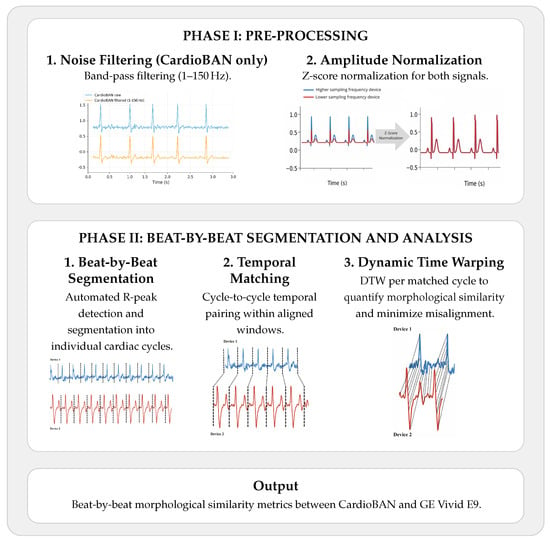

The ECG signals obtained from the wearable device (CardioBAN) and the clinical reference system (GE Vivid E9) were recorded simultaneously in a controlled environment to ensure temporal correspondence between both sources. A two-phase processing pipeline was applied to all recordings to minimise noise, harmonise signal characteristics, and enable waveform-level comparison between devices, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overall ECG processing pipeline. Phase I performs pre-processing of the CardioBAN and reference ECG signals (noise filtering and amplitude normalization). Phase II implements beat-by-beat segmentation, temporal matching, and DTW-based morphological comparison. Illustrative examples are are fictious and only intended to demonstrate the applied methodology.

3.3.1. Phase I: Pre-Processing

For each ECG signal stored in CSV format, a 4th-order Butterworth band-pass filter (1–150 Hz) was first applied to reduce baseline wander and suppress high-frequency artifacts, thereby preserving the clinically relevant spectral components of the ECG. This filtering step was applied exclusively to the CardioBAN. No filtering was applied to the GE Vivid E9 trace, since this system already outputs a pre-cleaned ECG derived from its internal acquisition chain and does not exhibit significant noise or arttifacts.

Second, z-score normalization was applied to standardize both signals to zero mean and unit variance, scaling amplitudes within a comparable range. This procedure eliminates inter-device amplitude differences and has been widely recommended in biosignal analysis to enhance robustness and comparability across datasets [33].

3.3.2. Phase II: Beat-by-Beat Segmentation and Analysis

In Phase II (Beat-by-beat segmentation and analysis), Figure 2, the preprocessed ECG signals were segmented into individual cardiac cycles using automatically detected R-peaks [34,35]. R-peaks were identified with the SciPy find_peaks function, and detection parameters (prominence, minimum distance, height) were empirically tuned for each participant. All peak candidates were manually reviewed to confirm physiological correctness, and parameters were adjusted whenever spurious or missed detections occurred.

To enable accurate morphological comparison between the wearable and the clinical reference system, DTW was applied on a beat-by-beat basis, allowing each cardiac cycle to be independently aligned. This approach reduces the influence of natural temporal offsets between devices and ensures that morphological similarity is assessed at an appropriate physiological resolution.

After validation of all R-peak locations, each CardioBAN cycle was temporally paired with the corresponding GE Vivid E9 cycle within the same acquisition window. DTW was then applied independently to each paired cycle to perform elastic temporal alignment and compute a beat-level morphological similarity score. The resulting DTW distances were aggregated per participant and used as the primary metric of morphological agreement between devices.

3.4. Implementation Details

All analyses were performed in a Python 3 environment using established scientific libraries (NumPy 1.24.2 [36], Pandas 1.5.3 [36], SciPy 1.10.1 [37,38], Matplotlib 3.7.1 [39], and dtaidistance 2.3.10 [40]). In particular, DTW was implemented using the dtaidistance package, which provides efficient distance calculation and deformation trajectory extraction. DTW was computed between z-scored beat-segmented cycles using a Euclidean point-wise distance and a constrained temporal window (Sakoe–Chiba band); Full parameter settings and the complete processing pipeline are openly available in a public GitHub repository for full reproducibility. The full implementation, including preprocessing routines, R-peak detection, beat segmentation, temporal matching, and DTW computation, is available at: https://github.com/inesescrivaes/CardioBAN-ECG-Analysis (accessed on 1 August 2025). This implementation enabled a quantitative assessment of morphological accuracy, supporting a transparent and reproducible evaluation of the wearable device relative to a clinically certified reference standard.

4. Results

Table 2 summarises the DTW global values across all participants. Mean distances ranged from 0.200 to 0.777, revealing a heterogeneous but predominantly favourable pattern of ECG waveform similarity. Seven participants (40%) exhibited mean DTW values below 0.55, indicating high morphological agreement for a substantial portion of the cohort. The remaining participants showed mean values between 0.56 and 0.78, a range still compatible with good cycle-level concordance. At group level, the mean DTW distance was 0.493 (SD = 0.166) with a median of 0.483, supporting generally consistent morphological alignment between the two systems.

Table 2.

Cycle-by-cycle DTW RMSE analysis quantifying morphological similarity between CardioBAN and GE Vivid ECG signals after beat-to-beat temporal alignment. For each participant, Mean, Median, Min, and Max represent within-subject DTW RMSE values computed across all valid cardiac cycles. Group-level descriptive statistics (Average, Std Dev, Minimum, and Maximum) are reported in the lower rows.

Participants with the lowest mean DTW values: P1 (0.200) and P7 (0.228), demonstrated excellent temporal and morphological concordance between CardioBAN and GE Vivid signals. Their QRS complexes exhibited close overlap with minimal temporal warping required for alignment. Conversely, participants such as P11 (0.777) and P14 (0.715) exhibited the highest mean DTW values. Even so, the overall waveform morphology remained largely preserved, with consistent QRS polarity and duration across devices. The higher DTW values in these cases mainly reflected increased beat-to-beat variability and small amplitude fluctuations, rather than any clinically relevant morphological disagreement.

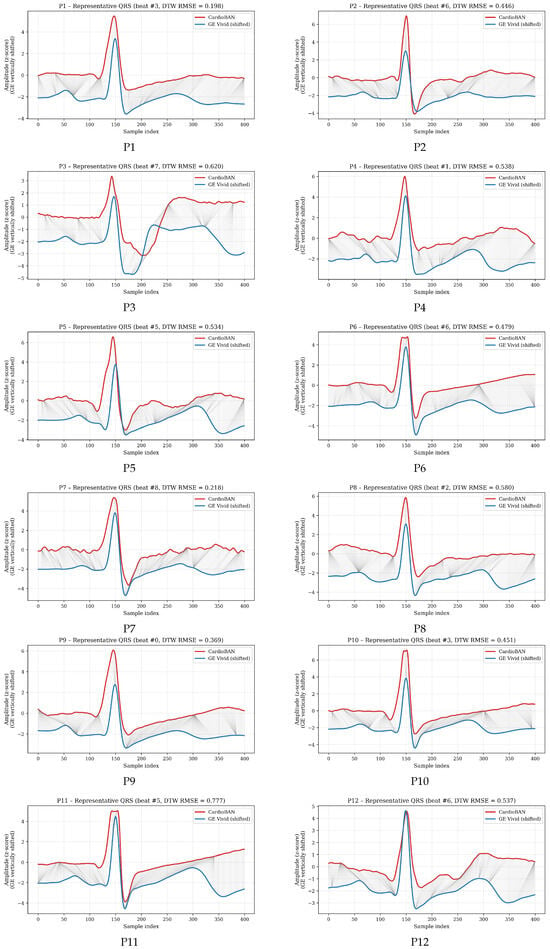

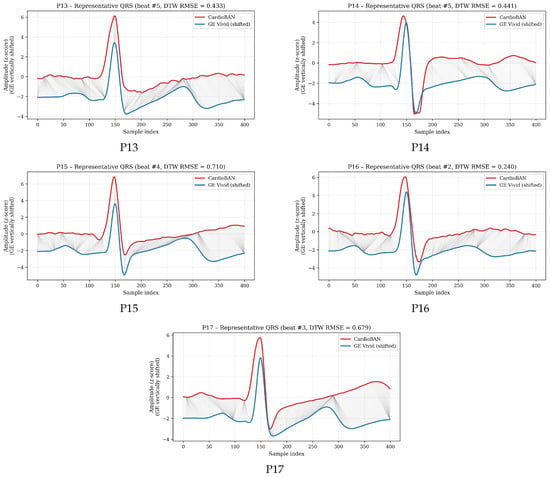

To illustrate the full performance spectrum, Figure 3 presents DTW-aligned QRS cycles for all participants (P1–P17), each represented by the cycle whose DTW distance was closest to that participant’s mean. Most participants show substantial signal overlap with modest warping, consistent with strong morphological similarity. Those with intermediate DTW values display moderate variability, compatible with normal physiological fluctuations and minor acquisition-related differences. Even for participants with the highest mean DTW, the visual preservation of QRS morphology suggests that discrepancies lie within expected variability rather than reflecting device-dependent distortions. These visual examples complement the numerical results by illustrating how DTW adapts to the participant-specific characteristics of each recording, such as noise level, signal stability, or subtle beat-to-beat variability, while still preserving a clear and interpretable comparison between the two devices.

Figure 3.

DTW-based alignment of representative QRS cycles for all participants (P1–P17). For each participant, the cycle whose DTW distance was closest to the participant’s mean DTW value was selected. The GE Vivid reference signal is shown in blue and the CardioBAN wearable signal in red, with grey lines depicting local warping correspondences along the optimal DTW path.

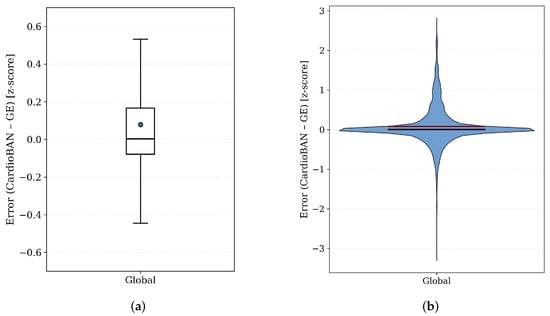

A global analysis of point-wise amplitude error following DTW alignment is shown in Figure 4. The boxplot reveals a very narrow interquartile range, indicating that amplitude differences between CardioBAN and GE Vivid remain small after temporal alignment and normalization. The violin plot presents a highly concentrated and symmetric density centred around zero, with almost all samples contained within ±0.2 z-score units. Such a restricted range is physiologically negligible and suggests strong overall agreement in waveform amplitude. These patterns indicate that residual discrepancies are primarily attributable to minor noise fluctuations or small beat-level misalignments, rather than systematic differences between the two devices.

Figure 4.

Global distribution of point-wise amplitude errors between CardioBAN and GE Vivid ECG signals after DTW-based temporal alignment. (a) Boxplot summarizing the central tendency and spread of the aligned errors. (b) Violin plot showing the corresponding empirical density, highlighting the smooth and symmetric distribution around zero; the black line denotes the median, while the red line represents the mean value.

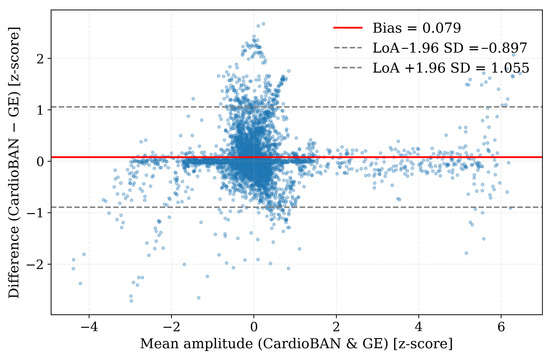

These findings were corroborated by the Bland–Altman analysis (Figure 5). The systematic bias was minimal (0.079), indicating an absence of consistent over- or underestimation between devices. The 95% limits of agreement (−0.897 to 1.055) were narrow relative to the dynamic range of the z-score–normalised ECG signals, reflecting small point-wise amplitude differences across the dataset. The dense concentration of points around the mean bias further shows that, once temporal misalignment is corrected by DTW, the CardioBAN wearable provides amplitude measurements that closely match those of the clinical GE Vivid reference.

Figure 5.

Global Bland–Altman plot for point-wise amplitude differences between CardioBAN and GE Vivid ECG signals after DTW-based temporal alignment. Blue circles represent individual point-wise amplitude differences. The central solid line indicates the mean difference (bias), while the upper and lower dashed lines denote the limits of agreement.

Taken together, the DTW metrics, the participant-level QRS alignments, the global error-distribution analysis, and the Bland–Altman statistics provide mutually consistent evidence of strong morphological correspondence between the CardioBAN and GE Vivid E9 signals after beat-level temporal alignment. Across all analyses, residual differences remained small and within the expected range of physiological and acquisition-related variability. No systematic waveform discrepancies were observed, and the overall morphology (QRS polarity, width, and repolarisation profile) was preserved in all participants.

5. Discussion

This study presents a comprehensive methodological and experimental framework for validating the morphological accuracy of wearable ECG systems. Its primary contribution lies in the implementation of a cycle-by-cycle DTW approach, enabling a physiologically meaningful comparison between individual cardiac cycles recorded by the CardioBAN wearable and those obtained from the clinically certified GE Vivid E9. This work constitutes one of the first independent assessments of CardioBAN waveform fidelity and extends existing literature by focusing on morphological similarity rather than solely on heart-rate or rhythm detection.

Unlike conventional validation approaches that analyse entire ECG traces globally, the present framework isolates and aligns individual cardiac cycles based on automatically detected R-peaks.

This beat-level segmentation reduces the effects of global temporal shifts, motion artifacts, baseline drift, and natural beat-to-beat variability: factors that disproportionately affect wearable devices. By operating at this finer analytical scale, the methodology enables a more robust assessment of waveform morphology and provides a clearer representation of signal integrity. Such precision is essential for the clinical translation of wearable ECG technologies, particularly in ambulatory settings where physiological and behavioural variability is unavoidable.

A further strength of this study is its emphasis on transparency and reproducibility. The complete preprocessing and analysis pipeline, including filtering, normalization, segmentation, alignment, DTW configuration and statistical analysis, is publicly provided to support methodological consistency and enable replication across research groups.

5.1. Comparison with Previous Literature

Before examining how the present results relate to previous studies, it is important to clarify how DTW should be interpreted in the context of ECG validation. No universal or clinically validated thresholds exist to classify DTW values as indicating “good” or “poor” agreement, since the absolute magnitude of the distance depends on several methodological factors, including normalization, sampling frequency and cycle length. Even so, the literature consistently shows that lower DTW distances correspond to greater waveform similarity, an observation also reported in other time-series domains such as guided-wave structural health monitoring, where DTW decreases as waveform correspondence improves [41]. In ECG-specific applications, previous work has similarly demonstrated that reduced DTW values are associated with higher morphological similarity, whereas larger values tend to arise from transient timing variability, physiological beat-to-beat fluctuations or noise-related distortions rather than true morphological disagreement [23,24]. For these reasons, DTW values in the present study were interpreted descriptively rather than as diagnostic thresholds: lower distances reflect closer correspondence between CardioBAN and GE Vivid waveforms, intermediate values indicate moderate similarity and higher values typically represent isolated deviations. The relatively narrow variability observed across participants further suggests that the alignment procedure produced stable and reproducible beat-level comparisons in this cohort. When viewed in the context of the broader literature, the present findings are consistent with studies demonstrating the value of morphology-focused analyses in wearable ECG validation. Wagner et al. (2021) [16] validated a low-cost ECG system for psychophysiological monitoring and emphasised the importance of accurate waveform morphology. Cosoli et al. (2023) [18] proposed a standardised methodology for assessing wearable ECG performance during physical activity, highlighting the sensitivity of morphology to electrode placement and motion.

Shorten and Burke (2014) [19] and Sanjo et al. (2024) [20] applied DTW to ECG analysis and showed that the technique provides a sensitive and physiologically interpretable metric for waveform comparison. The present study extends this body of work by applying beat-level DTW in a clinical validation context using GE Vivid E9 as a certified reference system, thereby bridging methodological gaps between wearable and clinical-grade ECG technologies.

5.2. Interpretation of Morphological Metrics

The DTW findings indicate that CardioBAN reproduces the essential morphological characteristics of the ECG waveform with a high degree of fidelity. Participants with the lowest DTW values (for example, P1: 0.200 and P7: 0.228) exhibited very close correspondence with the clinical reference, with minimal localized distortions after alignment. Intermediate DTW values, which characterised most of the cohort (approximately 0.48–0.62), reflected moderate but physiologically coherent variability. Even the highest DTW distances (P11: 0.777 and P14: 0.715) remained within a range in which the overall morphology was preserved, with maintained QRS structure and consistent beat-level dynamics across cycles. These higher values were associated with transient and expected sources of variation, such as minor motion, subtle fluctuations in electrode–skin impedance or small amplitude drifts, rather than with systematic limitations of the CardioBAN hardware. The relatively narrow dispersion observed across participants (mean 0.493, SD 0.166) further supports the stability and reproducibility of the alignment procedure.

The global error distributions provide additional insight into amplitude consistency after DTW alignment. The boxplot of point-wise errors showed a narrow central region with tightly grouped values, indicating that most aligned samples deviated only slightly between devices. The violin plot further confirmed a highly concentrated and approximately symmetric density around zero, with thin tails signalling that larger deviations were infrequent. These complementary visualisations demonstrate that amplitude discrepancies are small, stable and uniformly distributed once temporal variability is corrected.

The Bland–Altman analysis reinforces this interpretation. After alignment, point-wise amplitude differences demonstrated minimal bias (0.079) and narrow limits of agreement (−0.897 to 1.055), with observations densely clustered around zero. This pattern confirms that CardioBAN and the GE Vivid reference exhibit high amplitude concordance across thousands of aligned samples. Taken together, the DTW results, error distributions and Bland–Altman analysis demonstrate that the wearable device achieves waveform accuracy that approaches that of a clinical ECG system under controlled conditions, supporting its suitability for short-term morphological assessment.

5.3. Methodological Considerations

The methodological approach adopted in this study was designed to enable a detailed, cycle-level comparison of ECG morphology between a wearable device and a clinical reference system. Unlike global correlation metrics, which primarily assess overall similarity, a beat-by-beat framework allows the evaluation of localized morphological differences that may occur between individual cardiac cycles. This distinction is important because wearable-derived ECG signals are particularly susceptible to subtle variations related to electrode contact, motion, or sensor positioning, which may not affect clinical-grade hardware to the same extent.

DTW was selected as the core analytical technique because it provides flexible temporal alignment between two ECG segments, compensating for small variations in cycle timing while preserving the underlying morphology. By applying DTW on a per-beat basis, the analysis captures local waveform distortions that conventional time-locked metrics would overlook. This is particularly relevant given that even under controlled laboratory conditions, physiological variations such as respiratory sinus arrhythmia or autonomic fluctuations introduce natural beat-to-beat variability that can influence ECG timing.

Preprocessing was standardized for both systems to minimize non-physiological variability. This included band-pass filtering, amplitude normalization, and resampling to a unified sampling frequency to ensure comparability between waveforms. The segmentation procedure relied on robust R-peak detection algorithms, enabling consistent extraction of corresponding cardiac cycles prior to DTW analysis. Together, these methodological steps aim to isolate morphological differences attributable to device performance rather than preprocessing artifacts or inconsistencies in the analytical pipeline.

5.4. Implications and Future Directions

The present findings indicate that beat-level DTW analysis is a reliable and physiologically meaningful method for assessing morphological similarity between wearable and clinical ECG systems. Under controlled conditions, the CardioBAN device demonstrated waveform fidelity approaching that of the GE Vivid E9 reference, reinforcing its potential for short-term waveform assessment. Future work should first expand the sample size to encompass a more diverse population. The current cohort comprised only young, healthy adults; including older individuals, participants with cardiovascular conditions, and populations with greater morphological variability will be essential for assessing generalizability. In addition, simultaneous acquisition with hardware synchronization would reduce cross-device temporal drift and allow finer quantification of true morphological mismatch. Implementing shared triggers, unified clocks, or timestamp-level synchronization would eliminate a major source of uncertainty.

Further research should also explore ambulatory and stress-induced recording conditions, where motion artifacts, posture variability, and dynamic changes in autonomic tone are more prominent. Evaluating performance during real-world activity would provide a more comprehensive picture of device robustness. Together, these directions outline a clear pathway toward a unified and clinically meaningful methodology for validating next-generation wearable ECG systems.

5.5. Study Limitations

This study presents several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, the sample consisted exclusively of young, healthy Portuguese adults, which restricts the generalizability of the results. ECG morphology and beat-to-beat variability can differ substantially with age, autonomic balance, and cardiovascular pathology. Validation in larger and more heterogeneous cohorts, particularly older adults and patients with arrhythmias, is therefore required. Second, the absence of hardware-level synchronization between the CardioBAN and GE Vivid E9 systems introduces intrinsic temporal uncertainty. Because the devices operated with different sampling frequencies and internal processing latencies, recordings did not begin simultaneously, and cycle timing could not be precisely matched. These factors required the use of DTW to correct temporal misalignment and may have contributed to inflated DTW distances even when the underlying morphology was stable. A third limitation arises from the sequential acquisition protocol. Because the recordings were not obtained simultaneously, natural physiological variability, including small fluctuations in heart rate, autonomic tone, and respiratory sinus arrhythmia, may have introduced differences between cycles independently of device performance.

6. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that the CardioBAN wearable device is capable of reproducing ECG morphology with high fidelity when compared with a clinically certified reference system. Through beat-level DTW alignment, CardioBAN achieved waveform similarity approaching that of the GE Vivid E9, confirming its ability to capture the principal electrical features of cardiac activity under controlled conditions. These results support its suitability for short-term research use and highlight its potential for broader clinical applications involving continuous, non-invasive cardiac monitoring.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, software development, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, and visualization: all authors; Writing—original draft and review & editing: all authors; Supervision, project administration, and funding acquisition: all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of 2Ai–IPCA (protocol code 2AIEC002-2023) on 12 December 2023.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study can be made available upon a justified request to the corresponding author. The data are not publicly accessible because the ethical approval for this study did not explicitly include permission for broader data sharing.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Portuguese National funds, through the 424 Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) under a non-academic PhD Research Grant (Ref. 425 2023.00485.BDANA). It was also funded by national funds, through the FCT Fundação para 426 a Ciência e Tecnologia and FCT/MCTES in the scope of the projects UID/PRR/05549/2025 427 (https://doi.org/10.54499/UID/PRR/05549/2025) and UID/05549/2025 (https://doi.org/10.54442899/UID/05549/2025)), CEECINST/00039/2021 and LASI-LA/P/0104/2020. This work was also 429 funded by the Innovation Pact HfPT Health from Portugal, co-funded from the “Mobilizing Agendas 430 for Business Innovation” of the “Next Generation EU” program of Component 5 of the Recovery and 431 Resilience Plan (RRP), concerning “Capitalization and Business Innovation”, under the Regulation of 432 the Incentive System “Agendas for Business Innovation”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Mensah, G.A.; Fuster, V.; Roth, G.A. A Heart-Healthy and Stroke-Free World: Using Data to Inform Global Action. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2023, 82, 2110–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Majumder, S.; Mondal, T.; Deen, M.J. Wearable sensors for remote health monitoring. Sensors 2017, 17, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Athavale, Y.; Krishnan, S. Biosignal monitoring using wearables: Observations and opportunities. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2017, 38, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, M.; Gandhi, B. The genre of applications requiring long-term and continuous monitoring of ECG signals. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Innovations in Information, Embedded and Communication Systems (ICIIECS), Coimbatore, India, 17–18 March 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Joseph, K.P.; Kannathal, N.; Lim, C.M.; Suri, J.S. Heart rate variability: A review. Med. Biol. Eng. Comput. 2006, 44, 1031–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ChuDuc, H.; NguyenPhan, K.; NguyenViet, D. A review of heart rate variability and its applications. APCBEE Procedia 2013, 7, 80–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, R.; Kumar, R.; Malik, S.; Raj, T.; Kumar, P. Analysis of heart rate variability and implication of different factors on heart rate variability. Curr. Cardiol. Rev. 2021, 17, e160721189770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Banca, M.M.R.; Junior, J.J.A.M.; Pires, M.B.; Silva, S.L., Jr. Captura e processamento de sinais biomédicos utilizando o LabVIEW. J. Appl. Instrum. Control 2016, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, S.R.; Ng, N.; Tsanas, A.; Mclean, K.; Pagliari, C.; Harrison, E.M. Mobile devices and wearable technology for measuring patient outcomes after surgery: A systematic review. NPJ Digit. Med. 2021, 4, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, D.; Colwell, E.; Low, J.; Orychock, K.; Tobin, M.A.; Simango, B.; Buote, R.; Van Heerden, D.; Luan, H.; Cullen, K.; et al. Reliability and Validity of Commercially Available Wearable Devices for Measuring Steps, Energy Expenditure, and Heart Rate: Systematic Review. JMIR MHealth UHealth 2020, 8, e18694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahiya, E.S.; Kalra, A.M.; Lowe, A.; Anand, G. Wearable Technology for Monitoring Electrocardiograms (ECGs) in Adults: A Scoping Review. Sensors 2024, 24, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sibomana, O.; Hakayuwa, C.M.; Obianke, A.; Gahire, H.; Munyantore, J.; Chilala, M.M. Diagnostic Accuracy of ECG Smart Chest Patches versus PPG Smartwatches for Atrial Fibrillation Detection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. BMC Cardiovasc. Disord. 2025, 25, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, R.; Blackburn, G.; Desai, M.; Phelan, D.; Gillinov, L.; Houghtaling, P.; Gillinov, M. Accuracy of wrist-worn heart rate monitors. JAMA Cardiol. 2017, 2, 104–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Babu, M.; Lautman, Z.; Lin, X.; Sobota, M.H.B.; Snyder, M.P. Wearable devices: Implications for precision medicine and the future of health care. Annu. Rev. Med. 2024, 75, 401–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prasitlumkum, N.; Cheungpasitporn, W.; Chokesuwattanaskul, A.; Thangjui, S.; Thongprayoon, C.; Bathini, T.; Vallabhajosyula, S.; Kanitsoraphan, C.; Leesutipornchai, T.; Chokesuwattanaskul, R. Diagnostic accuracy of smart gadgets/wearable devices in detecting atrial fibrillation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2021, 114, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, R.E.; da Silva, H.P.; Gramann, K. Validation of a Low-Cost Electrocardiography (ECG) System for Psychophysiological Research. Sensors 2021, 21, 4485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Song, J.H.; Kim, S.H. Validation of Wearable Digital Devices for Heart Rate Measurement During Exercise Test in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease. Ann. Rehabil. Med. 2023, 47, 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosoli, G.; Antognoli, L.; Scalise, L. Wearable Electrocardiography for Physical Activity Monitoring: Definition of Validation Protocol and Automatic Classification. Biosensors 2023, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, G.P.; Burke, M.J. Use of Dynamic Time Warping for Accurate ECG Signal Timing Characterization. J. Med. Eng. Technol. 2014, 38, 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanjo, K.; Takahashi, M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Okada, K.; Yamaguchi, T. Sensitivity of Electrocardiogram on Electrode-Pair Location and Morphology Variability via Dynamic Time Warping. Front. Physiol. 2024, 15, 1412268. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Alam, M.A. Dynamic time warping (DTW) algorithm in speech: A review. Int. J. Res. Electron. Comput. Eng. 2018, 6, 524–528. [Google Scholar]

- Anh, D.T.; Thanh, L.H. An efficient implementation of k-means clustering for time series data with DTW distance. Int. J. Bus. Intell. Data Min. 2015, 10, 213–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lauder, B.; Schwerin, B.; McConnell, M.; So, S. Using dynamic time warping for noise robust ECG R-peak detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 13th International Conference on Signal Processing and Communication Systems (ICSPCS), Gold Coast, Australia, 16–18 December 2019; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazandarani, F.N.; Mohebbi, M. Wide complex tachycardia discrimination using dynamic time warping of ECG beats. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2018, 164, 238–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, I.; Moody, G.B.; Mark, R.G. Predicting ventricular tachyarrhythmias using the dynamic time warping distance between ECG beats. Comput. Cardiol. 2016, 43, 613–616. [Google Scholar]

- Bent, B.; Goldstein, B.A.; Kibbe, W.A.; Dunn, J.P. Investigating sources of inaccuracy in wearable optical heart rate sensors. NPJ Digit. Med. 2020, 3, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, C.; Viana, J.; Lopes, F. Wearable and remote monitoring technologies for precision medicine: The Portuguese HowMI project. IRBM 2023, 44, 100658. [Google Scholar]

- Matouq, J.; Al Tarabsheh, A.; Barham, R.; Alqaraleh, S.; Alrashdan, L.; Ababneh, O.; Alsubaihi, S. Investigation and Validation of New Heart Rate Measurement Sites for Wearable Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuda, E.; Kusumoto, F.; Shibata, M.; Yamamoto, R.; Hayano, J. Preliminary Study on Heart Rate Response to Physical Activity Using a Wearable ECG Device. Electronics 2025, 14, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bumgarner, J.M.; Lambert, C.T.; Hussein, A.A.; Cantillon, D.J.; Baranowski, B.; Wolski, K.; Lindsay, B.D.; Wazni, O.M.; Tarakji, K.G. Smartwatch algorithm for automated detection of atrial fibrillation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018, 71, 2381–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.V.; Mahaffey, K.W.; Hedlin, H.; Rumsfeld, J.S.; Garcia, A.; Ferris, T.; Balasubramanian, V.; Russo, A.M.; Rajmane, A.; Cheung, L.; et al. Large-Scale Assess. A Smartwatch Identify Atr. Fibrillation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 1909–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, R.T. Electrocardiographic Limb Leads Placement and Its Clinical Implication: Two Cases of Electrocardiographic Illustrations. Kans. J. Med. 2021, 14, 229–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, Y.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y. ECG Authentication Based on Non-Linear Normalization under Various Physiological Conditions. Sensors 2021, 21, 6966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, U.R.; Oh, S.L.; Hagiwara, Y.; Tan, J.H.; Adam, M.; Gertych, A.; Tan, R.S. A deep convolutional neural network model to classify heartbeats. Comput. Biol. Med. 2017, 89, 389–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Zheng, C.; Tai, C. Detection of ECG characteristic points using wavelet transforms. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 1995, 42, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C.R.; Millman, K.J.; van der Walt, S.J.; Gommers, R.; Virtanen, P.; Cournapeau, D.; Wieser, E.; Taylor, J.; Berg, S.; Smith, N.J.; et al. Array programming with NumPy. Nature 2020, 585, 357–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference (SciPy 2010), Austin, TX, USA, 28 June–3 July 2010; van der Walt, S., Millman, J., Eds.; SciPy: Austin, TX, USA, 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nat. Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meert, W.; Hendrickx, K.; Van Craenendonck, T.; Robberechts, P.; Blockeel, H.; Davis, J. DTAIDistance (Version v2). Zenodo 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglass, A.C.S.; Harley, J.B. Dynamic Time Warping Temperature Compensation for Guided Wave Structural Health Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 2018, 65, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).