Abstract

Although the increased use of three-dimensional (3D) cone beam computed tomography (CBCT) in orthodontic treatment, the necessity of the CBCT on treatment decision-making for maxillary impacted canines was not fully assessed compared to two-dimensional (2D) radiographs. This study aimed to assess differences in treatment decisions derived from CBCT data and 2D radiographs by analyzing survey responses from orthodontic specialists. Ten maxillary impacted canines with complete sets of two-dimensional (2D) radiographs and 3D CBCT data were selected and two sets of questionnaires were administered: using 2D radiographic data and 3D CBCT data. 31 orthodontists completed the survey. Diagnoses and treatment decisions were compared between the 2D and 3D imaging. Additionally, estimated angular and linear measurements of canine position were assessed with 2D and 3D and compared with actual CBCT measurements. The treatment decisions varied between 2D and 3D imaging. Notably, 51.5% of extraction decision with 2D were changed to orthodontic traction with 3D. The 3D imaging also improved the prediction of tooth collisions during traction and reduced the perceived treatment difficulty. CT proficiency influenced clinical decisions, with higher proficiency levels associated with fewer extractions and more accurate treatment predictions. 3D imaging offers greater diagnostic accuracy and improved treatment planning for impacted canines compared to 2D imaging, particularly for high and palatal impactions.

1. Introduction

Impacted canines can lead to various clinical complications, including resorption of adjacent teeth, potentially necessitating extraction [1], loss of available arch space, displacement of adjacent teeth [2], cyst formation, infection of surrounding tissues, and referred pain. Maxillary canines play a crucial role in function and esthetics, contributing to lateral mandibular movement, lip support, and the maintenance of a symmetric smile. Given their significance [3], accurate diagnosis and effective management are essential for comprehensive orthodontic treatment [4,5].

Traditionally, two-dimensional (2D) radiographic imaging, including periapical and occlusal films and frontal and lateral cephalograms, has been the primary modality for diagnosing impacted canines [6]. However, 2D imaging presents inherent limitations such as superimposition, image distortion, and difficulty in assessing the precise spatial relationship between the impacted tooth and surrounding anatomical structures. These limitations can contribute to diagnostic inaccuracies [7], prolonged treatment duration, or even failure of forced eruption.

To overcome these challenges, three-dimensional (3D) imaging—particularly cone beam computed tomography (CBCT)—has gained prominence in orthodontic diagnosis and treatment planning [8,9]. CBCT provides volumetric data that allows for a detailed understanding of the impacted canine’s position, proximity to adjacent structures [10,11], and associated complications such as root resorption [12,13]. These features have made CBCT an attractive tool for improving the accuracy of diagnosis and the precision of surgical and orthodontic interventions.

While several studies have confirmed the diagnostic superiority of CBCT over 2D radiographs, its influence on clinical decision-making remains an area of ongoing debate. For instance, it was said that the evidence supporting its use as a first-line imaging modality is still limited [14] and more research is needed for regular use [15], although CBCT offers enhanced localization accuracy. A recent study has questioned meaningful changes in treatment planning despite CBCT’s diagnostic advantages [16].

Given these uncertainties, there remains a critical need to determine whether CBCT truly affects the clinical decision-making process in a way that justifies its use over conventional 2D imaging. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate whether CBCT-derived volumetric data influence diagnostic assessments and treatment decisions for maxillary impacted canines, in comparison to traditional 2D radiographs, using survey responses from orthodontic specialists. By identifying the extent to which CBCT affects treatment planning, this study seeks to contribute evidence that may guide imaging protocols for impacted canines in clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyungpook National University Dental Hospital (No. KNUDH-2023-12-02-00). Informed consent for participation was obtained from the guardians of all patients and from all orthodontists who participated in the survey, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations from the IRB.

2.1. Study Samples

A total of 871 patients visited the Department of Orthodontics at the Kyungpook National University Dental Hospital between 2019 and 2022 with a chief complaint of impacted teeth or ectopic eruption pathways. Among them, 10 patients (six females, four males), aged 11.3 to 23.5 years (mean age: 15.34 ± 3.98 years) were selected based on the presence of a unilateral impacted maxillary canine. Patient selection was determined by vertical and labiolingual position and angulation. The inclusion criteria were as follows: the presence of a unilateral impacted canine, availability of a complete set of traditional 2D diagnostic radiographs, and CBCT scans. Patients were excluded if they presented with craniofacial anomalies, congenital missing teeth, prosthetic restorations, or a history of orthodontic treatment.

The 2D data included a panoramic radiograph (Orthophos 3®, Sirona, Bensheim, Germany) for vertical position assessment and a lateral cephalogram (CX-90SP II, Asahi Roentgen Ind. Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) with exposure settings of 70 kV and 80 mA for determining the labio-palatal position. Additionally, extraoral (frontal, lateral, and smile) and intraoral (frontal, lateral, and occlusal) photographs were obtained. 3D CBCT scans were acquired using a CB MercuRay system (Hitachi, Osaka, Japan) with the following parameters: 120 kVp, 15 mA, a 19-cm field of view, a scan time of 9.6 s, voxel size of 0.2 mm, and an axial slice thickness of 0.38 mm. The CBCT data were reconstructed into 3D images using Invivo software (version 5.4; Anatomage, San Jose, CA, USA), while segmentation was performed using CB-Works software (CyberMed, Seoul, Republic of Korea). The volume operation and sculpt features were used to eliminate soft and hard tissues, preserving only the maxillary dentition. Each 3D image of the impacted canines and maxillary dentition was saved at every 3° interval across a full 360° rotation. Additionally, axial cross-sectional CBCT images were constructed.

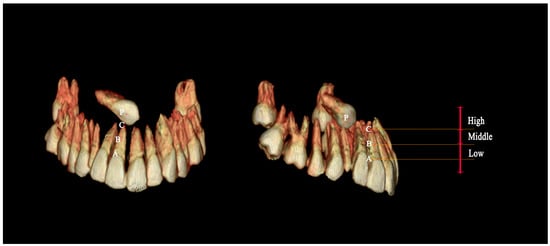

The vertical position of the impacted canines was categorized into three levels—low, middle, and high—based on reference points along the root surface of the central incisor. Point A was set at the cementoenamel junction (CEJ), point B at the midpoint between the CEJ and root apex, and point C at the root apex. Point P was defined as the center of the impacted canine crown. The classification was determined by the relative position of point P to points A, B, and C (Figure 1). The detailed characteristics of the 10 selected impacted canines are presented in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Three-dimensional reconstructed images of an impacted canine illustrating its vertical position relative to anatomical reference points. A: Cementoenamel junction (CEJ); B: midpoint between the CEJ and root apex; C: root apex; P: center of the crown of the impacted canine on the buccal side. The position of the impacted canine was classified as follows: high: crown located at or above point C; middle: crown positioned between points B and C; low: crown located between points A and B.

Table 1.

Selected 10 cases of impacted canines.

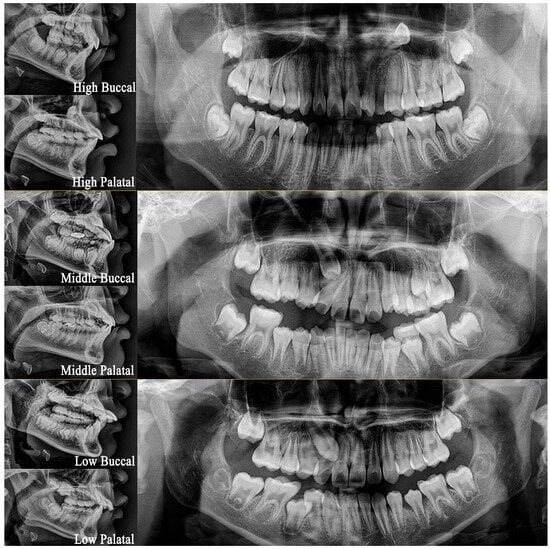

Figure 2.

Cephalometric lateral and panoramic radiographs depicting palatally and buccally impacted canines classified into high, middle, and low positions.

2.2. Survey

All patient-identifying information, including name, sex, age, and patient identification number, was removed before data distribution. The 2D data were shared with over 100 orthodontic specialists, of whom 49 responded. These 49 respondents were subsequently provided with the 3D data, and 31 orthodontists completed both questionnaires. Among these 31 participants, 16 had prior experience using CBCT for diagnosis and treatment, while 15 did not.

The questionnaire comprised 56 items, including 21 primary questions and 35 sub-questions (Table 2). To ensure consistency, multiple co-authors reviewed the questionnaires as part of the calibration process. The questionnaires were distributed both online and in paper format. The survey covered various aspects of treatment planning, including indications for extraction (if chosen), the angular relationship of the impacted canine to the occlusal and midsagittal planes, the shortest distance between the impacted canine and adjacent teeth, and the percentage of external root resorption (PPER) affecting adjacent teeth at the initial stage. Additional questions addressed the surgical access direction, optimal bonding position for an orthodontic button on the canine crown, the number of changes in traction direction, the angle of traction forces, predicted tooth collisions during traction, the number of teeth expected to collide, appliance design for traction, predicted traction duration, and the level of treatment difficulty (LTD). The complete survey contents of the questionnaire items are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key Concepts from first and second questionnaires.

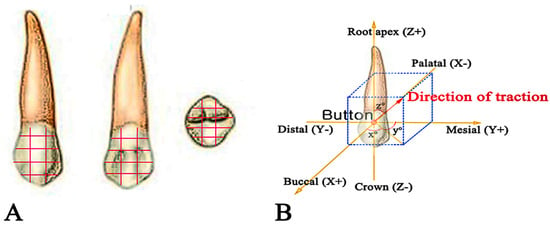

Each responder was required to select one of three treatment options: tooth extraction, orthodontic traction, or follow-up. If extraction was chosen, participants were asked to specify the rationale, selecting from the following factors: an untreatable canine position, high probability of treatment failure, ongoing root resorption of adjacent teeth, prolonged treatment duration, a challenge in accurately locating the position of the impacted canine, potential for tooth collisions during traction, or the decision to substitute the canine with a premolar. If substitution was considered due to crowding or lip protrusion, respondents were asked to propose an alternative treatment plan that excluded extraction. Additionally, respondents were asked to mark the preferred bonding position for an orthodontic button on the crown, which was divided into 15 equal parts (Figure 3A). The number of treatment plan modifications following the introduction of 3D data was recorded.

Figure 3.

(A) Division of the tooth into 15 equal parts for button placement. (B) Traction direction represented in three-dimensional coordinate planes, illustrating three angles formed by the three axes.

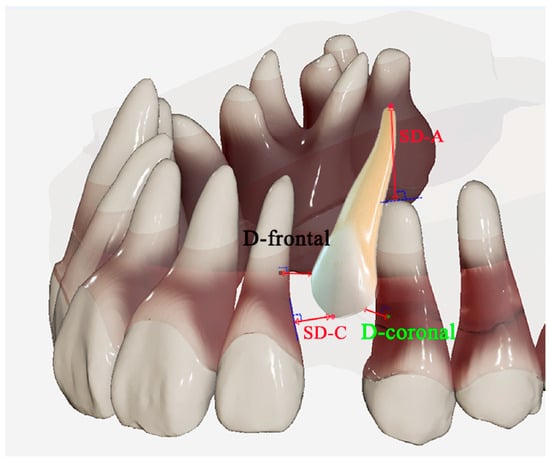

The angles between the tooth axis of the impacted canine and the occlusal and midsagittal planes were estimated. Additionally, participants were asked to determine the estimated traction direction (Figure 3B), with each estimated angle expressed in (X, Y, Z) coordinates. Respondents also provided their expectations regarding the number of changes in traction direction and the likelihood of collisions with adjacent teeth during traction. To quantify spatial relationships, SD-C was defined as the shortest distance from the cusp tip of the impacted canine to the nearest adjacent tooth, while SD-A was defined as the shortest distance from the root apex of the impacted canine to the nearest adjacent tooth. Furthermore, D-coronal represented the shortest distance from the crown of the impacted canine to adjacent teeth in the coronal plane, and D-frontal denoted the shortest distance from the crown of the impacted canine to adjacent teeth in the midsagittal plane (Figure 4). All defined distances were assessed using 2D and 3D data. Accuracy was evaluated by comparing the estimated values with actual CBCT measurements obtained through Invivo software (version 5.4; Anatomage, San Jose, CA, USA) and CB-Works software (version 2.0; CyberMed, Seoul, Republic of Korea). A single qualified researcher measured the angle and distance for each case, averaging four independent measurements. The estimated values were then subtracted from the actual CBCT measurements.

Figure 4.

3D schematic representation of an impacted canine and its adjacent teeth, illustrating key distance measurements: SD-C (shortest distance between adjacent teeth and the crown of the impacted canine), SD-A (shortest distance between adjacent teeth and the apex of the impacted canine), D-coronal (shortest distance from the crown of the impacted canine to adjacent teeth in the coronal plane), and D-frontal (shortest distance from the crown of the impacted canine to adjacent teeth in the frontal plane).

The participants were asked to select from a set of appliances, including the trans-palatal arch and Nance appliance, or specify alternative appliances by providing a sketch of the appliance design. Traction time was defined as the estimated duration required for the impacted canine to emerge into the oral cavity. The LTD was assessed using a visual analog scale. To identify the factors affecting LTD [17], respondents were asked to select one or multiple factors from a predefined list, including patient age, sex, position of the impacted canine, root curvature, transposition, and other considerations. Participants then ranked these factors in order of perceived importance. After completing the second questionnaire, participants who modified the plans were asked to explain the reasons for the changes and specify which data affect the decisions. Additionally, all participants were surveyed on their perceptions regarding the necessity of 3D data for clinical decision-making. To further investigate the impact of CBCT proficiency on data interpretation, respondents were categorized into two groups, the Y-CT group (orthodontic specialists with prior CBCT training experience) and the N-CT group (orthodontic specialists without CBCT training). 16 belonged to the Y-CT group, while 15 belonged to the N-CT group.

2.3. Statistics

The data were analyzed using SPSS (IBM SPSS statistics 23 version). The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data distribution. A paired t-test was conducted to compare the differences between 2D and 3D data. Additionally, one-way analysis of variance followed by a Scheffé post hoc test was performed to evaluate the discrepancies between estimated values derived from 2D and 3D data and actual CBCT measurements. A paired t-test was used to compare the differences between 2D and 3D estimations, as well as the deviations in both from the actual CBCT measurements. Furthermore, an independent t-test was performed to examine the influence of computed tomography (CT) proficiency between the two groups.

3. Results

The intra-rater reliability analysis of the questionnaire responses is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Intra-rater reliability and Kappa values.

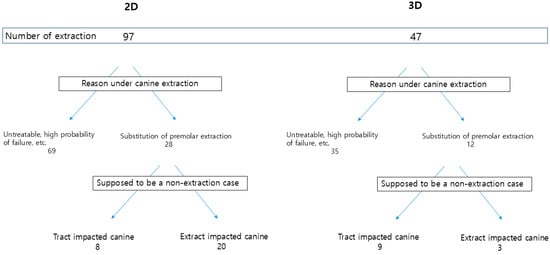

Although all impacted canines in the study successfully erupted into the attached gingiva following orthodontic traction, treatment decisions varied among respondents. The use of 3D data (16 ± 12) resulted in fewer extraction decisions compared to 2D data (30 ± 24) (Table 4). Specifically, extraction was initially recommended in 97 out of 310 cases based on 2D data; however, this number decreased to 47 when reassessed using 3D data, reflecting a 51.5% reduction in extraction decisions in favor of orthodontic traction (Table 5). Among the 97 extractions proposed in the 2D assessment, 28 respondents cited premolar substitution as the rationale. When asked to reconsider treatment plans excluding extraction, eight of these 28 respondents (29%) opted for orthodontic traction after reevaluating the 2D data. In contrast, nine of 12 respondents (75%) shifted from extraction to orthodontic traction based on 3D data, while the remaining three opted for implant prostheses (Figure 5).

Table 4.

The differences in extraction decision, traction directions, position of impacted canines, and root resorption between 2D and 3D radiographs.

Table 5.

Decision changes on extraction or orthodontic traction after examining 3D images.

Figure 5.

Decision tree illustrating survey results on extraction decision-making.

The predicted traction duration was 12 months based on 2D data, 5 months longer than the estimate derived from 3D data. The average actual traction duration was 13.60 ± 4.69 months. The estimated possibility of collision with adjacent teeth was lower with 3D data (0.42 ± 0.49) than with 2D data (0.78 ± 0.54). Additionally, the bonding position of the button was modified in 220 out of 310 cases following 3D data assessment. The average number of traction modifications was higher with 3D data (1.1 ± 0.97) than with 2D data (0.69 ± 0.62), suggesting that 3D imaging facilitates more precise button positioning and traction direction, thereby reducing the risk of collisions and potentially shortening treatment duration. LTD was higher when using 2D data (63.12 ± 20.29) than 3D data (52.74 ± 19.20). The most influential factor affecting LTD was the position of the impacted canine, followed by patient age, root curvature of the impacted canine, and transposition. The average PPER was 11.21 ± 15.10% when using 2D data but increased to 18.78 ± 21.75% when assessed using 3D data.

Statistically significant differences were observed between 2D and 3D data for SD-C, SD-A, and D-frontal, whereas D-coronal showed no significant difference (Table 4). Estimated distances for SD-C, SD-A, and D-frontal were greater in 3D data than in 2D data. When comparing estimates to actual CBCT measurements, 3D estimates were more accurate for the angle to the occlusal plane, angle to the midsagittal plane, SD-C, SD-A, D-coronal, and D-frontal in high-positioned canines. In middle-positioned canines, 3D estimates were significantly closer to actual measurements than 2D estimates for the angle to the occlusal plane, angle to the midsagittal plane, and SD-C. However, no significant differences were found between 2D and 3D estimates in low-positioned canines. Predicted traction time in 3D data was also more aligned with actual traction time than in 2D data for high- and middle-positioned canines. On the palatal side, all 3D parameters closely matched actual CBCT measurements compared to 2D data. In the buccal position, SD-C, D-frontal, and predicted traction time were more accurate in 3D estimates than in 2D estimates (Table 6). Differences in parameters between 2D and 3D data across various positions are illustrated in Table 7. Extraction rates, the predicted traction time, angles to the occlusal plane, angle to the midsagittal plane, SD-C, SD-A, D-coronal, and D-frontal were closer to actual CBCT measurements in 3D estimations across all positions, with statistically significant differences except in the buccal-low position. When using 2D data, respondents tended to overestimate the horizontal angulation of impacted canines relative to the occlusal and midsagittal planes while underestimating actual distances. Additionally, predicted collision rates during traction were consistently higher in 2D estimates across all positions (Table 7).

Table 6.

Similarity of the estimated values on 2D and 3D to 3D actual CBCT measurements.

Table 7.

Differences in parameters obtained by 2D and 3D data depending on the position of the impacted canine.

The impact of prior CT training experience on decision-making varied depending on the data type provided. No significant differences were observed between the Y-CT and N-CT groups when using 2D data. However, with 3D data, significant differences emerged between the two groups. In the Y-CT group, extraction rates, the predicted traction duration, and LTD were lower, whereas the number of changes in traction direction and PPER were higher than in the N-CT group (Table 8).

Table 8.

Differences in the diagnosis of impacted canines according to former training for CT.

4. Discussion

Treatment decisions for impacted maxillary canines significantly differed between 2D and 3D imaging modalities.

Thirty-one orthodontists selected extraction or orthodontic traction in the survey, although all 10 cases were successfully treated with orthodontic traction. The proportion of extraction decisions decreased following exposure to 3D data. Orthodontic traction accounted for 68.7% of decisions based on 2D data, increasing to 84.8% with 3D data. While 97 out of 310 cases were considered for extraction based on 2D data, this number decreased to 47 with 3D data, reflecting a 51.5% reduction in extraction decisions. These findings suggest that the availability of sophisticated 3D data facilitates modifications in treatment planning [18], supporting claims about CBCT’s diagnostic advantages by providing more accurate 3D visualization of the region of interest at preferred viewing directions and angulations. Furthermore, our results provide additional evidence addressing the concerns questioning whether CBCT-induced diagnostic changes lead to meaningful clinical shifts [16]. In our study, the reduction in extraction decisions implies that CBCT can affect not only traction direction but also fundamental treatment choices.

The primary reasons for selecting extraction based on 2D data were the challenges in accurately determining the position of the impacted canine and the perceived risk of damaging adjacent teeth during orthodontic traction. Orthodontists were more likely to opt for extraction in cases of highly positioned impacted canines due to the increased traction distance required. Furthermore, the complex spatial relationship with adjacent structures increased the risk of collision, leading to extraction decisions, particularly for palatal impactions. Contrarily, 3D data provides enhanced visualization of surrounding structures, allowing orthodontists to choose traction.

In diagnosis and treatment planning based on 3D data, the predicted traction time was shorter, with smaller deviations from actual measurements than estimates derived from 2D data. Additionally, the predicted collisions during traction were lower, while adjustments in traction direction were more frequent. By enhanced understanding of the spatial relationships between impacted canines and surrounding structures, a more precise traction direction was established, leading to more accurate treatment duration estimates. Moreover, the significant reduction in LTD suggests improved accessibility for orthodontic traction. Efficient orthodontic treatment may not only shorten the treatment period but also reduce the risk of dental caries associated with prolonged orthodontic intervention [19,20]. The findings indicate that 3D data resulted in fewer predicted collisions, increased modifications in bonding positions, reduced LTD, and more frequent adjustments in traction direction. These outcomes highlight the advantages of 3D imaging in providing a well-oriented visualization of the 3D relationships between impacted canines and adjacent teeth, thereby supporting the use of 3D CBCT for managing impacted canines.

Orthodontic traction requires a comprehensive understanding of the spatial relationships between impacted teeth and adjacent structures, as well as the precise execution of traction [11]. Accurate distance estimations during diagnosis are therefore essential. Actual CBCT measurements were closer to 3D estimations than 2D estimations. The distortion with panoramic images [21] could be maximized with significant vertical displacement and positioned outside the image layer, contributing to these discrepancies [22]. By using 3D data for precise diagnosis and proper treatment planning, clinicians can improve patient trust and satisfaction while minimizing unnecessary tooth movements and reducing the risk of root resorption due to collisions with adjacent teeth [23]. Additionally, 3D imaging not only enhances diagnostic accuracy but also lowers the failure rate associated with incomplete alignment of impacted canines within the dental arch [24]. These may strengthen the need for CBCT on clinical decision-making.

When evaluating the positions and distances of impacted canines relative to adjacent teeth, respondents using 2D consistently overestimated angles and underestimated distances compared to actual CBCT measurements. These discrepancies were more pronounced for high-positioned impacted canines. Furthermore, responders estimated buccally impacted canines more accurately than palatally impacted canines using 2D data. In 2D assessments, impacted canines were perceived as being more horizontally angulated in the occlusal and midsagittal planes than their actual positions, and their proximity to adjacent teeth was overestimated by over 1 mm in SD-C, D-coronal, and D-frontal measurements. The effectiveness of 3D imaging was particularly notable for high and palatally impacted canines compared to lower-positioned, mid-positioned, or buccally impacted cases. The tendency to underestimate distances and overestimate angles in 2D imaging might lead to an increased perception of collision risk during traction, potentially resulting in more frequent extraction decisions and prolonged traction times. Despite concerns regarding increased radiation exposure from CBCT [25,26,27], the benefits of 3D data for effectively diagnosing and treating impacted canines might be substantial. In addition, the use of a small field of view may further justify the application of CBCT in these cases by minimizing unnecessary radiation exposure [28].

Previous research has identified that unfamiliar visual environments can lead individuals to misjudge distances [29]. This underscores the influence of prior experience with CBCT on the ability to use and interpret 3D data effectively. In the study, the average extraction rate with 3D data was 9 ± 1% in the Y-CT group, compared to 26 ± 8% in the N-CT group. These results suggest that prior CT experience plays a significant role in decision-making related to extractions.

Potential biases might also arise from the variability in responses among orthodontists working in diverse clinical environments, due to the limited number of cases included. However, the validity of this study could be strengthened by the participation of many orthodontists. Further longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate whether these planning differences lead to superior treatment outcomes and to determine whether CBCT’s benefits outweigh the associated concerns on cost and radiation exposure.

5. Conclusions

3D CBCT data provided orthodontists with a comprehensive understanding of the spatial relationships between impacted canines and adjacent teeth. Compared to 2D imaging, 3D imaging offered superior accuracy in estimating angles and distances and was associated with fewer extraction decisions. In contrast, 2D imaging tended to overestimate angular measurements and underestimate distances relative to actual CBCT measurements.

Author Contributions

H.-S.P. designed and supervised the entire research. J.-N.L. performed all the experiments. J.-N.L. drafted the manuscript. J.-N.L., H.-J.K. and H.-S.P. analyzed and interpreted the data. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Kyungpook National University Dental Hospital (No. KNUDH-2023-12-02-00, 2 January 2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for participation was obtained from the guardians of all patients and from all orthodontists who participated in the survey, and all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations from the IRB.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ng, W.L.; Cunningham, A.; Pandis, N.; Bister, D.; Seehra, J. Impacted maxillary canine: Assessment of prevalence, severity anlocation of root resorption on maxillary incisors: A retrospective CBCT study. Int. Orthod. 2024, 22, 100890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekel, E.; Nucci, L.; Weill, T.; Flores-Mir, C.; Becker, A.; Perillo, L.; Chaushu, S. Impaction of maxillary canines and its effect on the position of adjacent teeth and canine development: A cone-beam computed tomography study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2021, 159, 135–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewel, B.F. The upper cuspid: Its development and impaction. Angle Orthod. 1947, 119, 79–90. [Google Scholar]

- Qali, M.; Li, C.; Chung, C.H.; Tanna, N. Periodontal and orthodontic management of impacted canines. Periodontol 2000 2024. early view. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedoya, M.; Park, J.H. A review of the diagnosis and management of impacted maxillary canines. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2009, 140, 1485–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinu, S.; Todor, L.; Zetu, I.N.; Păcurar, M.; Porumb, A.; Milutinovici, R.A.; Popovici, R.A.; Brad, S.; Sink, B.A.; Popa, M. Radiographic methods for locating impacted maxillary canines. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol. 2022, 63, 599–606. [Google Scholar]

- Chaushu, S.; Vryonidou, M.; Becker, A.; Leibovich, A.; Dekel, E.; Dykstein, N.; Nucci, L.; Perillo, L. The labiopalatal impacted canine: Accurate diagnosis based on the position and size of adjacent teeth: A cone-beam computed tomography study. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2023, 163, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaasalainen, T.; Ekholm, M.; Siiskonen, T.; Kortesniemi, M. Dental cone beam CT: An updated review. Phys. Med. 2021, 88, 193–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, E.; Venkatesh, E.S. Cone beam computed tomography: Basics and applications in dentistry. J. Istanb. Univ. Fac. Dent. 2017, 51, 102–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farha, P.; Nguyen, M.; Karanth, D.; Dolce, C.; Arqub, S.A. Orthodontic localization of impacted canines: Review of the cutting-edge evidence in diagnosis and treatment planning based on 3D CBCT Images. Turk. J. Orthod. 2023, 36, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, A.; Chaushu, S. Surgical Treatment of Impacted Canines What the Orthodontist Would Like the Surgeon to Know. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 27, 449–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durack, C.; Patel, S.; Davies, J.; Wilson, R.; Mannocci, F. Diagnostic accuracy of small volume cone beam computed tomography and intraoral periapical radiography for the detection of simulated external inflammatory root resorption. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Chen, J.; Deng, F.; Zheng, L.; Liu, X.; Dong, Y. Comparison of cone-beam computed tomography and periapical radiography for detecting simulated apical root resorption. Angle Orthod. 2013, 83, 189–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eslami, E.; Barkhordar, H.; Abramovitch, K.; Kim, J.; Masoud, M.I. Cone-beam computed tomography vs conventional radiography in visualization of maxillary impacted-canine localization: A systematic review of comparative studies. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2017, 151, 248–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keener, D.J.; de Oliveira Ruellas, A.C.; Aliaga-Del Castillo, A.; Arriola-Guillén, L.E.; Bianchi, J.; Oh, H.; Gurgel, M.L.; Benavides, E.; Soki, F.; Rodríguez-Cárdenas, Y.A.; et al. Three-dimensional decision support system for treatment of canine impaction. Am. J. Orthod. Dentofac. Orthop. 2023, 164, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoustrup, P.; Videbæk, A.; Wenzel, A.; Matzen, L.H. Will supplemental cone beam computed tomography change the treatment plan of impacted maxillary canines based on 2D radiography? A prospective clinical study. Eur. J. Orthod. 2024, 46, cjad062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baidas, L.F.; Alshihah, N.; Alabdulaly, R.; Mutaieb, S. Severity and treatment difficulty of impacted maxillary canine among orthodontic patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 10680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjerklin, K.; Ericson, S. How a computerized tomography examination changed the treatment plans of 80 children with retained and ectopically positioned maxillary canines. Angle Orthod. 2006, 76, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salerno, C.; Grazia Cagetti, M.; Cirio, S.; Esteves-Oliveira, M.; Wierichs, R.J.; Kloukos, D.; Campus, G. Distribution of initial caries lesions in relation to fixed orthodontic therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Orthod. 2024, 46, cjae008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, A.S.; Alves, L.S.; Maltz, M.; Susin, C.; Zenkner, J.E.A. Does the duration of fixed orthodontic treatment affect caries activity among adolescents and young adults? Caries Res. 2018, 52, 463–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.J.; Park, H.S.; Kwon, O.W. Evaluation of potency of panoramic radiography for estimating the position of maxillary impacted canines using 3D CT. Korean J. Orthod. 2008, 38, 265–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipp, R.G.; Hurst, R.V. The cant of the occlusal plane and distortion in the panoramic radiograph. Angle Orthod. 1978, 48, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Touati, R.; Sailer, I.; Marchand, L.; Ducret, M.; Strasding, M. Communication tools and patient satisfaction: A scoping review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2022, 34, 104–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.Y.; Jung, S.Y.; Lee, K.J.; Yu, H.S.; Park, W.S. Forced eruption in impacted teeth: Analysis of failed cases and outcome of re-operation. BMC Oral Heath 2024, 24, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Signorelli, L.; Patcas, R.; Peltomäki, T.; Schätzle, M. Radiation dose of cone-beam computed tomography compared to conventional radiographs in orthodontics. J. Orofac. Orthop. 2016, 77, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berkhout, W.E. The ALARA-principle. Backgrounds and enforcement in dental practices. Ned. Tijdschr. Tandheelkd. 2015, 122, 263–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.; Di Carlo, G.; Saccucci, M.; Tombolini, V.; Polimeni, A. Dental Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Children: Clinical Effectiveness and Cancer Risk due to Radiation Exposure. Oncology 2019, 96, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ludlow, J.B.; Timothy, R.; Walker, C.; Hunter, R.; Benavides, E.; Samuelson, D.B.; Scheske, M.J. Effective dose of dental CBCT—A meta analysis of published data and additional data for nine CBCT units. Dentomaxillofac. Radiol. 2015, 44, 20140197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Interrante, V.; Ries, B.; Lindquist, J.; Kaeding, M.; Anderson, L. Elucidating factors that can facilitate veridical spatial perception in immersive virtual environments. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 2008, 17, 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).