Efficient Neural Modeling of Wind Power Density for National-Scale Energy Planning: Toward Sustainable AI Applications in Industry 5.0

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Design a neural network architecture that maximizes accuracy while minimizing computational cost;

- Develop a reproducible and computationally efficient framework for large-scale wind resource assessment in data-scarce environments.

1.1. Computational Challenges in Wind Energy Assessment in Mexico

- Data sparsity

- High computational cost.

- Dynamic variability.

1.2. Design of Neural Networks for Wind Resource Mapping

1.2.1. Architectural Trade-Offs in Energy Forecasting

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs).

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs).

- Hybrid CNN–RNN models.

1.2.2. Comparative Performance of CNN, RNN, and Hybrid Models

1.2.3. Model Design and Implementation for Mexico

2. Materials and Methods

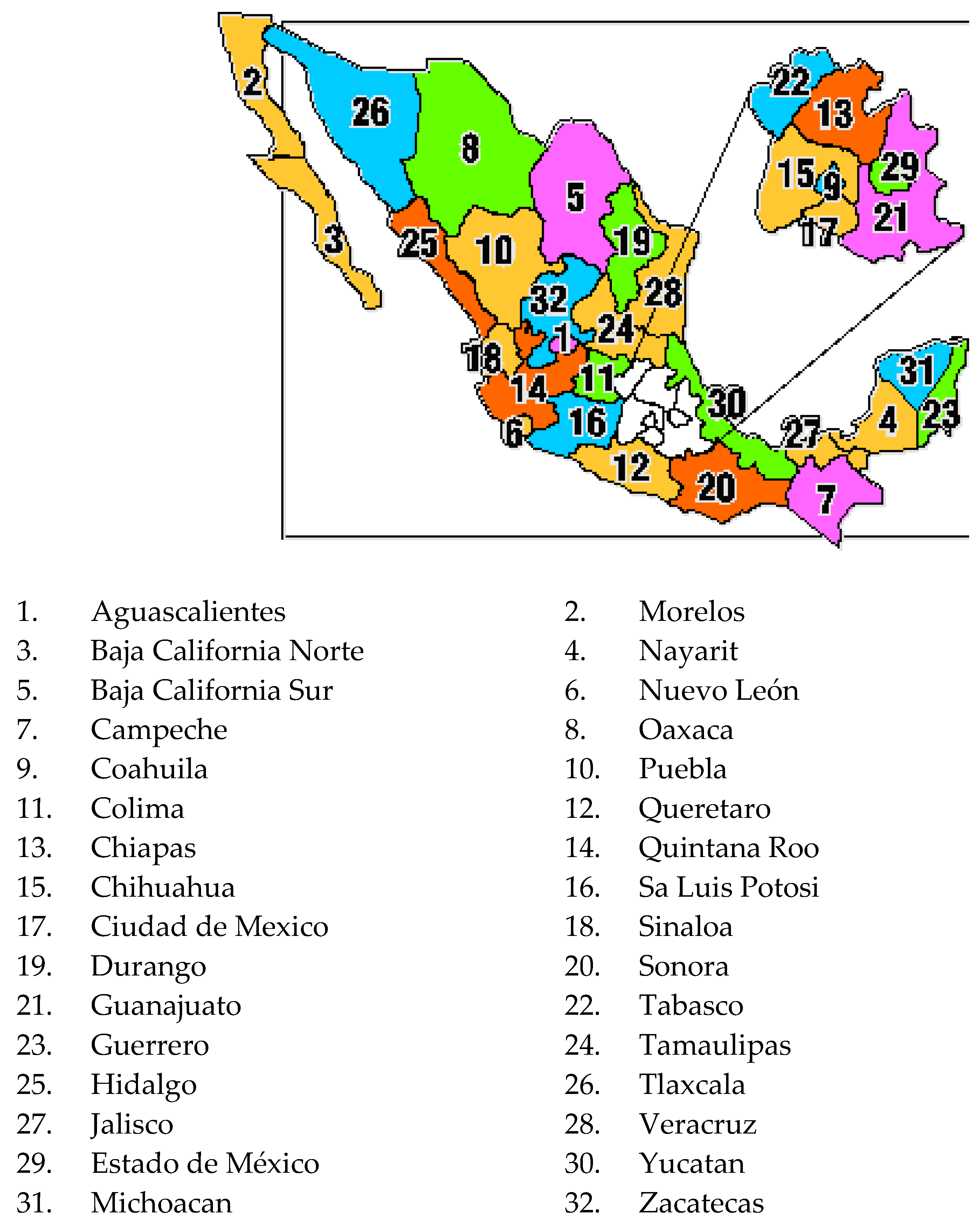

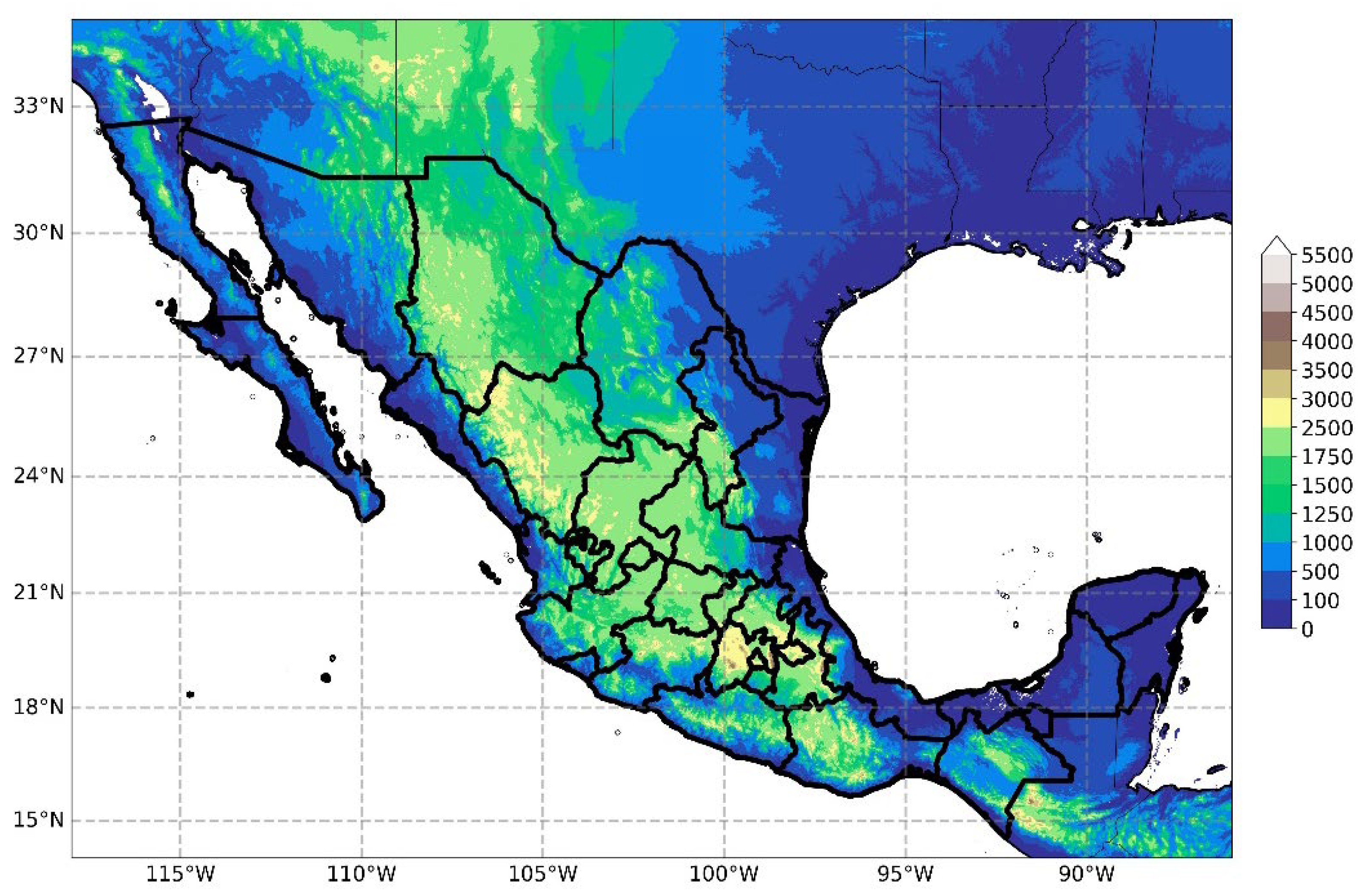

2.1. Study Area

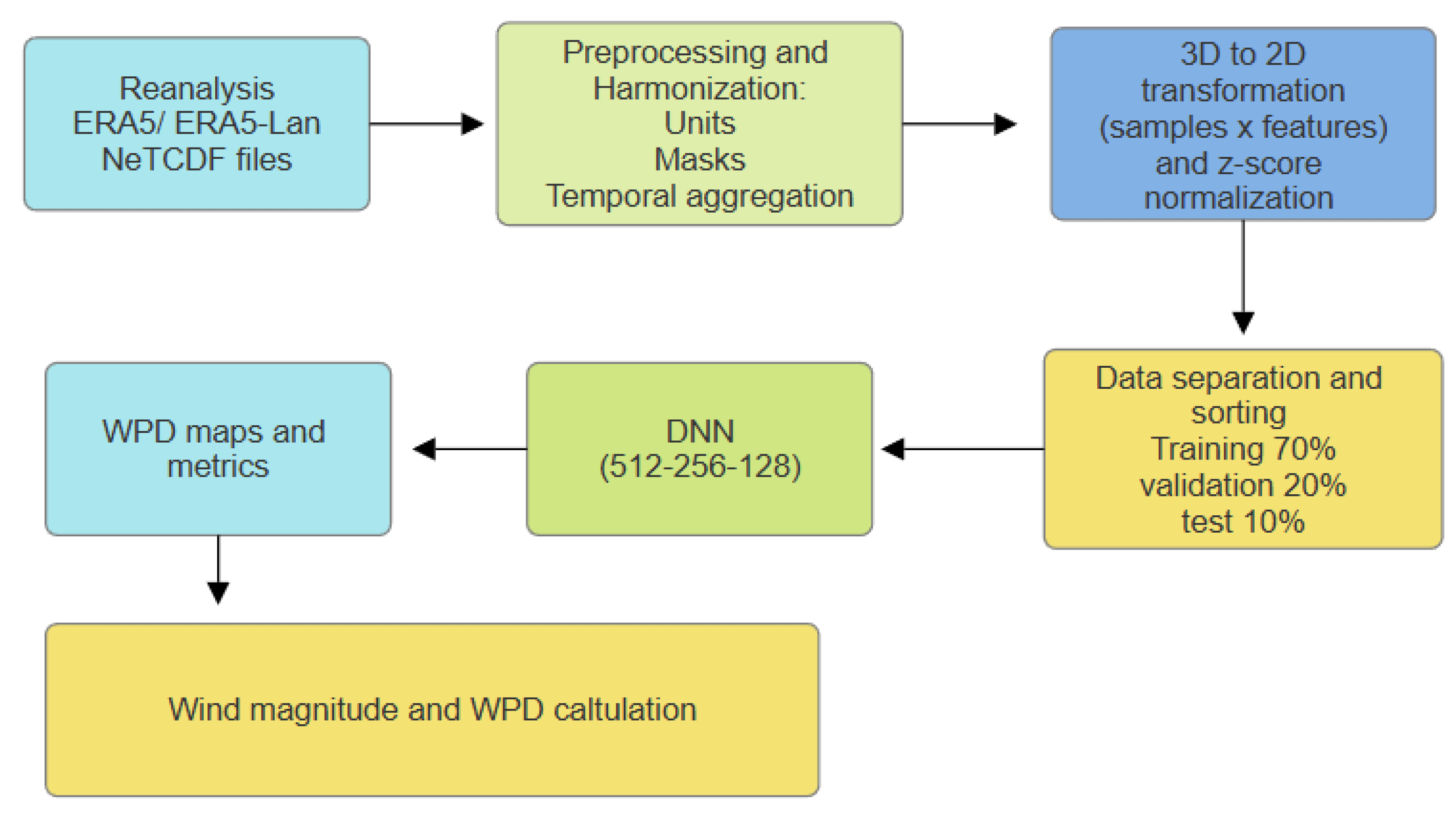

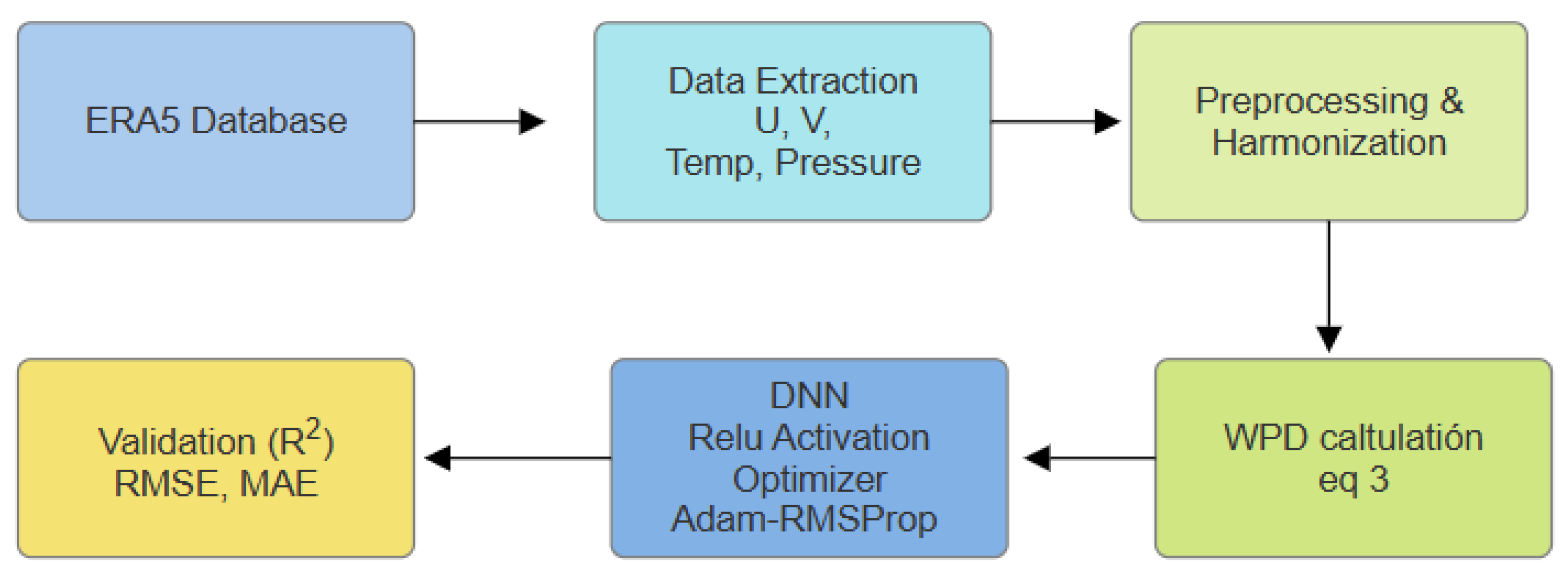

2.2. Data Acquisition, Processing, and Harmonization

2.2.1. Variable Selection

2.2.2. Wind Data Processing and Harmonization

- Data structure and alignment.

- Wind vector transformation.

- Vertical adjustment to 100 m.

- Wind Power Density (WPD) computation.

- Temporal aggregation and consistency.

- Spatial filtering and masking.

2.2.3. Data Transformation and Normalization

2.2.4. Dataset Partitioning

- 70% (1971–2010): used for training the DNN model,

- 20% (2011–2020): used for validation and hyper-parameter tuning, and

- 10% (2021–2024): reserved as a blind hold-out test set that was never accessed or optimized against during training or validation; this subset served exclusively for independent performance evaluation, comparing model predictions with ERA5 reference data.

2.2.5. Reproducibility and Computational Setup

2.3. Neural Network Architecture and Training

2.3.1. Network Architecture

2.3.2. Loss Function and Optimization

2.3.3. Training Setup

- CPU: AMD Ryzen 5 8600 G, (AMD, Santa Clara, CA, USA)

- RAM: 32 GB Corsair Vengeance DDR5 at 5200 MT/s (Corsair, Fremont, CA, USA)

- GPUs: MSI NVIDIA GTX 1070, 8 GB VRAM, (MSI, New Taipei City, Taiwan),

- GPU2: Gigabyte NVIDIA GTX 1060 6 GB VRAM, (Gigabyte Technology, New Taipei City, Taiwan), Both GPUs operated in a data-parallel configuration.

- Power supply: Cougar 750 W 80+ Gold certified PSU, (Cougar, Taipei, Taiwan)

2.3.4. Performance Stabilization and Reproducibility

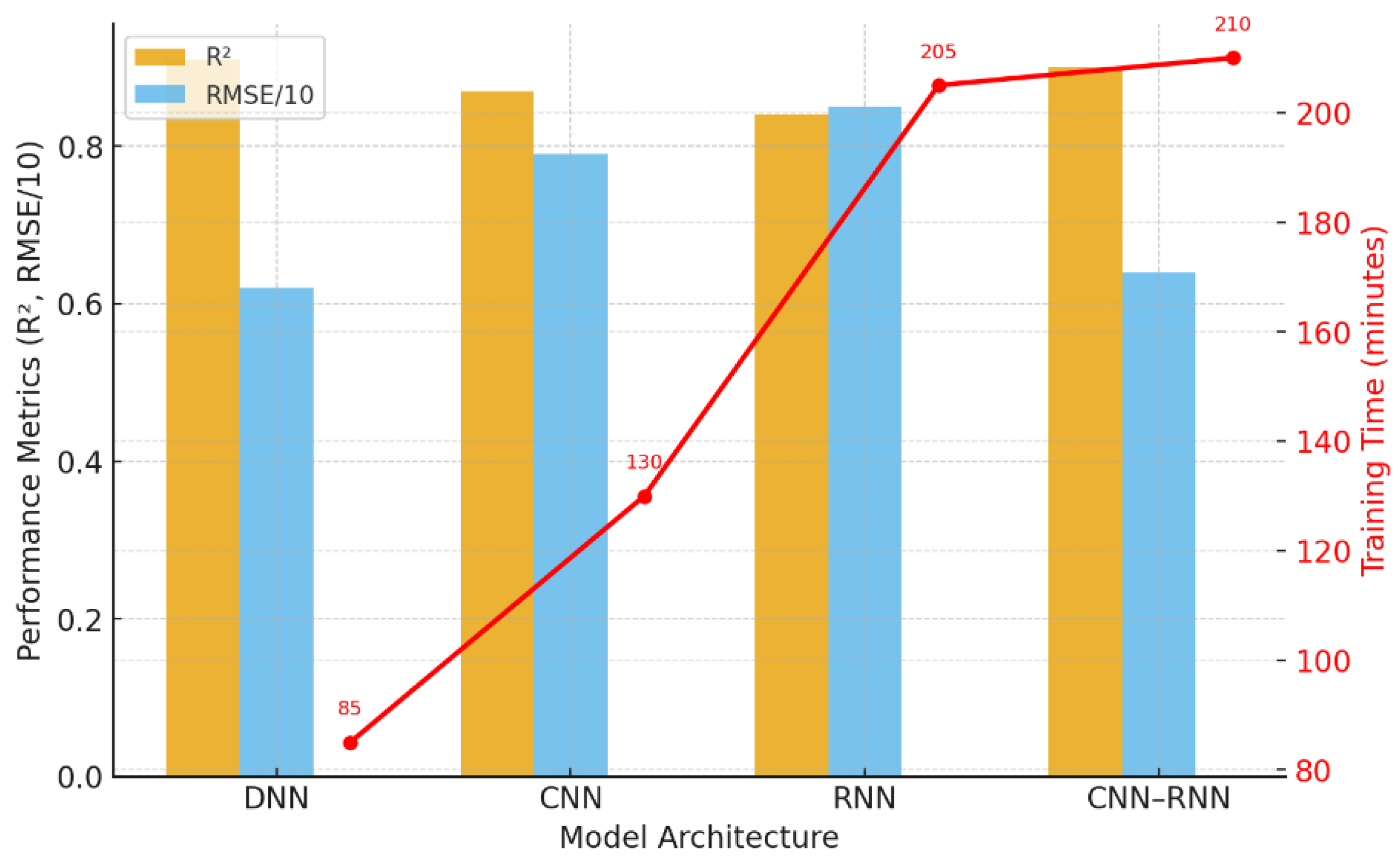

2.4. Comparative Analysis of Neural Architectures

2.4.1. Experimental Setup

2.4.2. Quantitative Comparison

3. Validation of the Neural Model

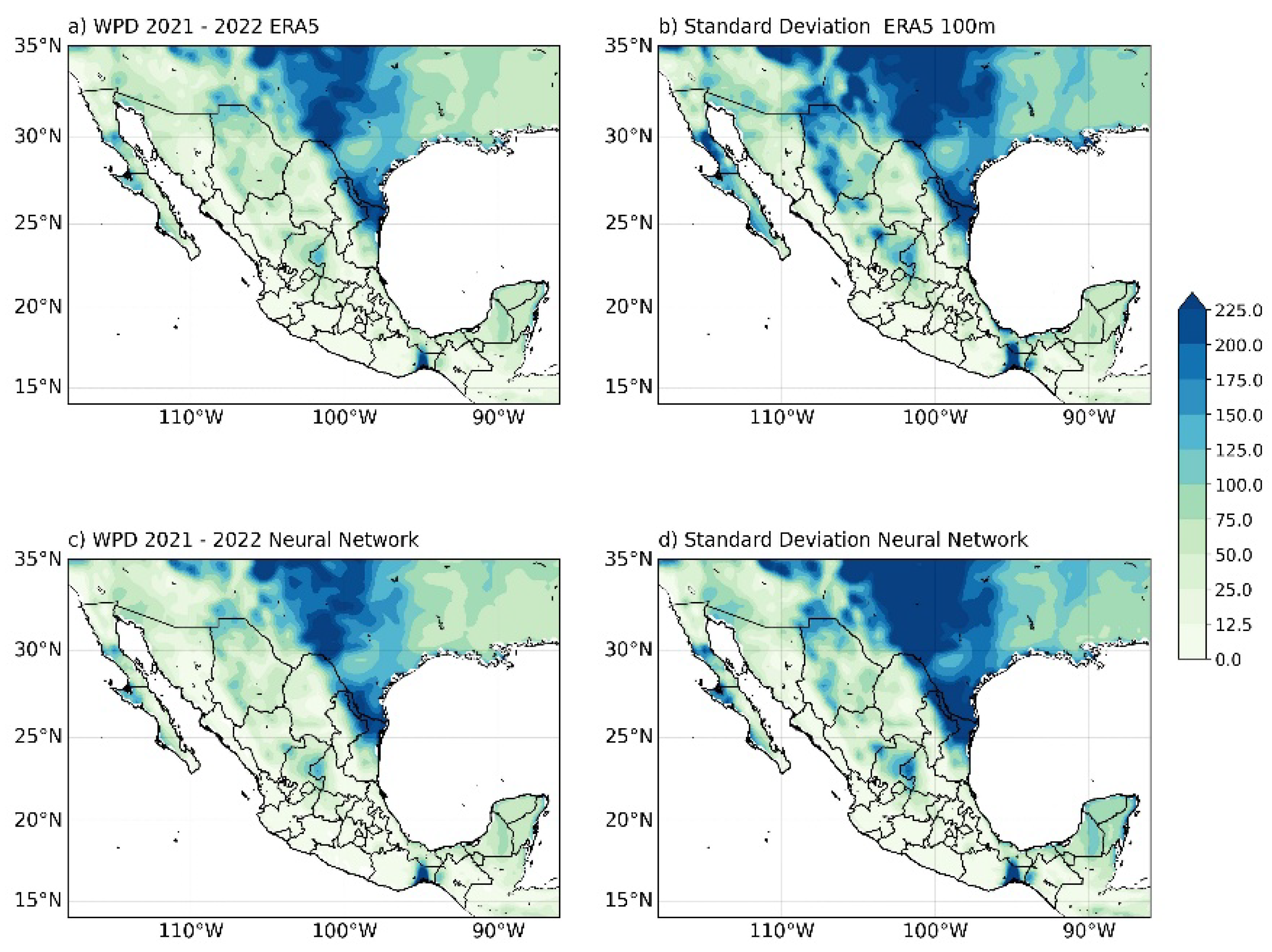

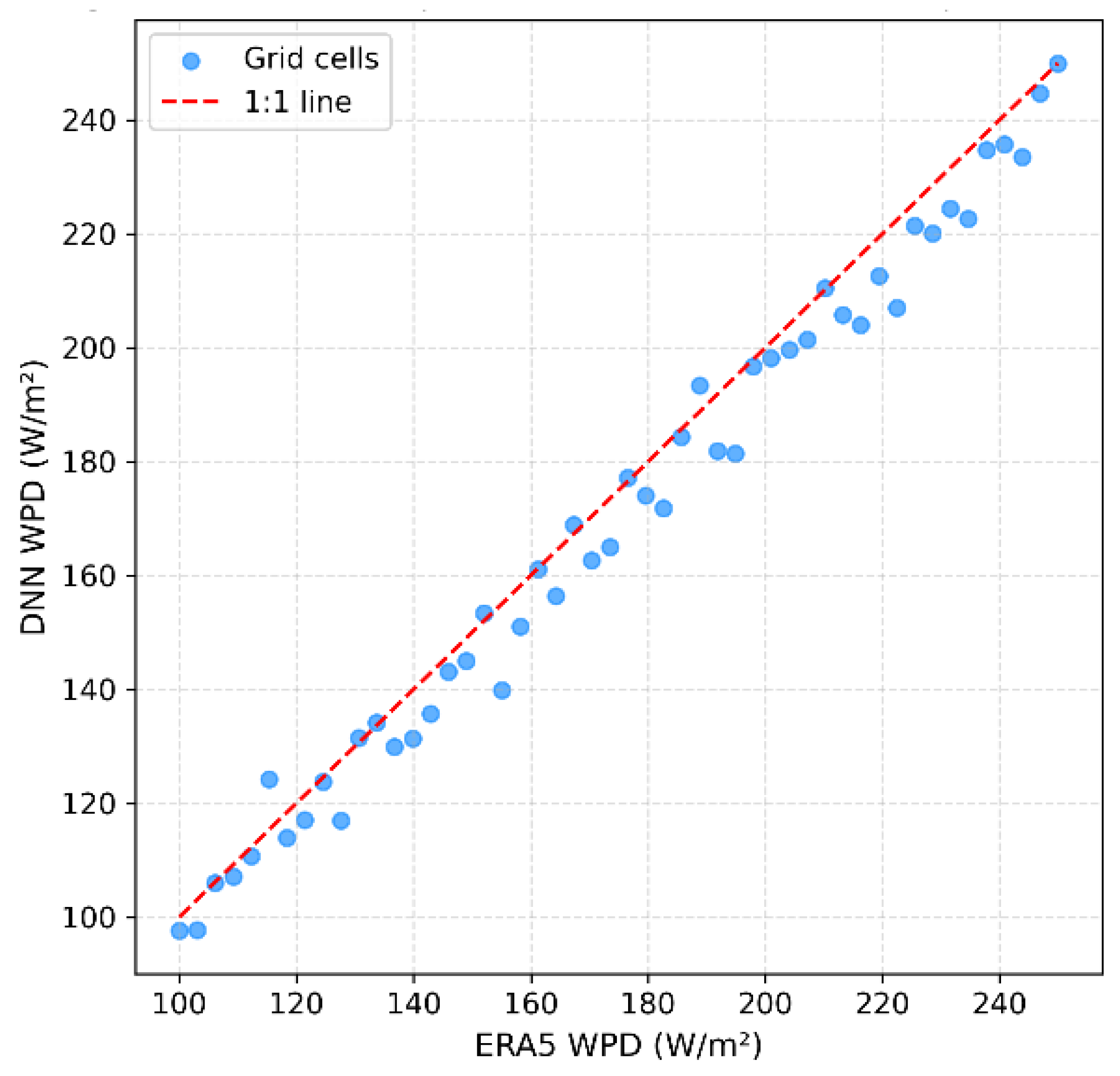

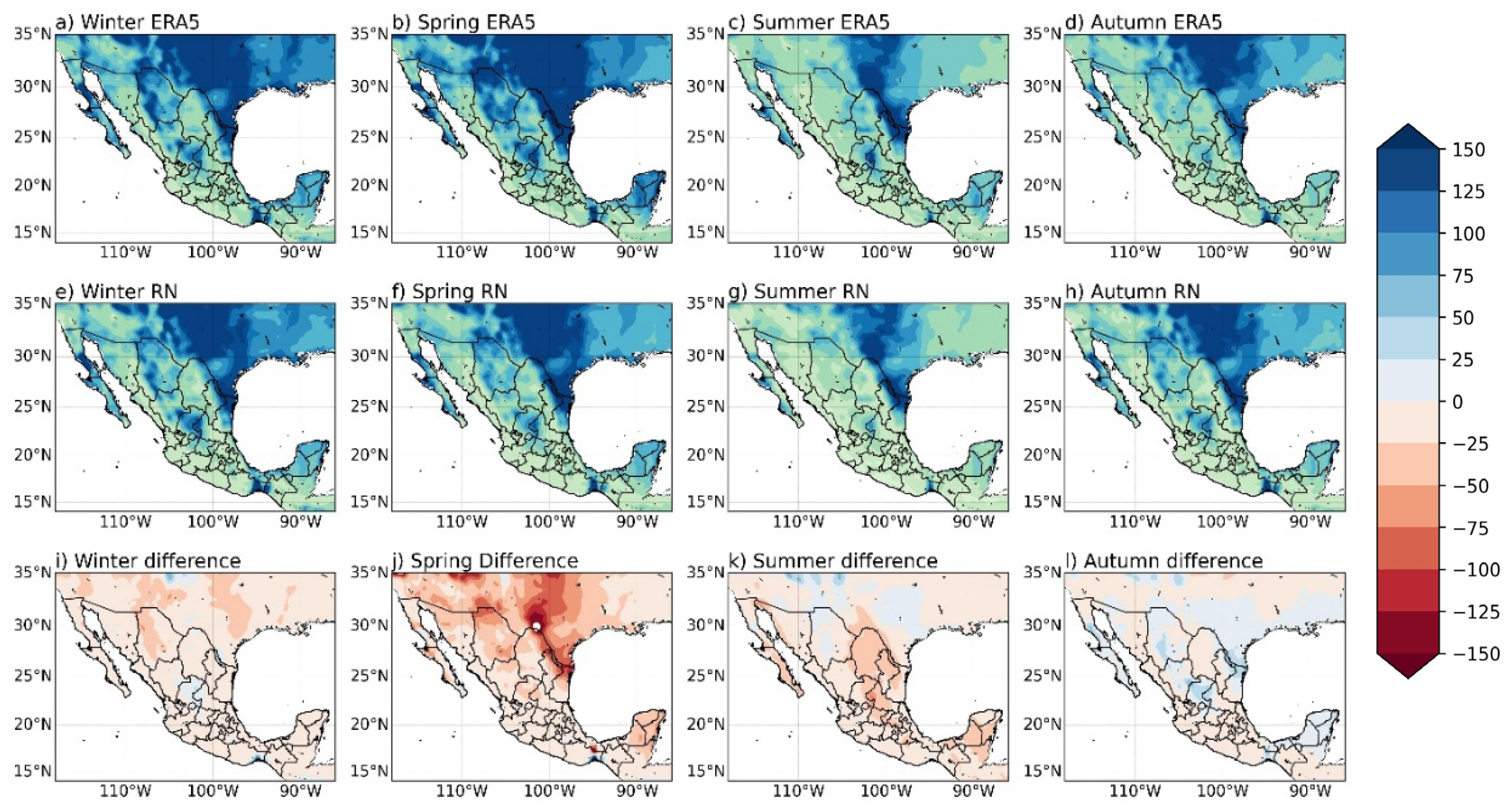

3.1. Model Performance and Spatial Validation

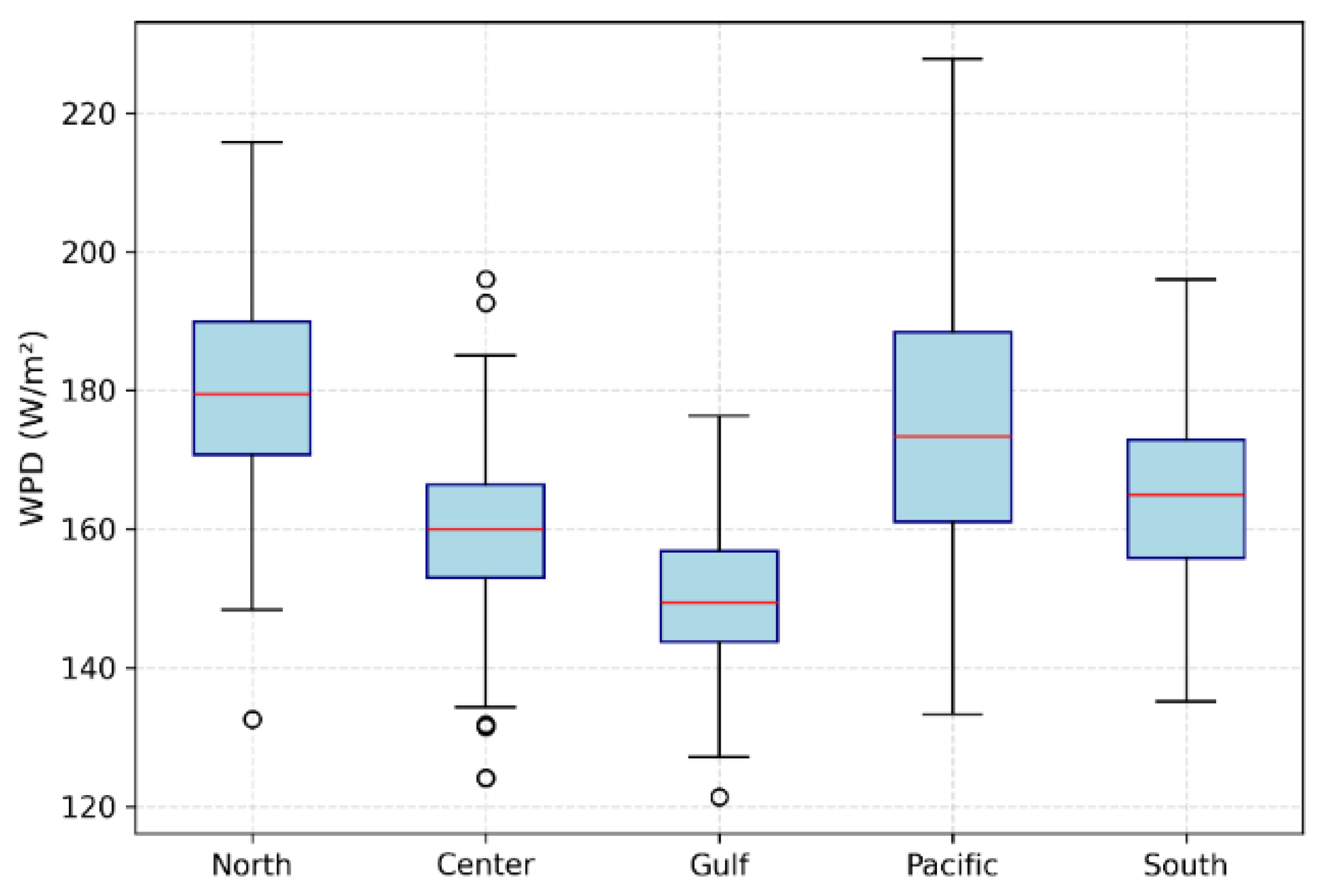

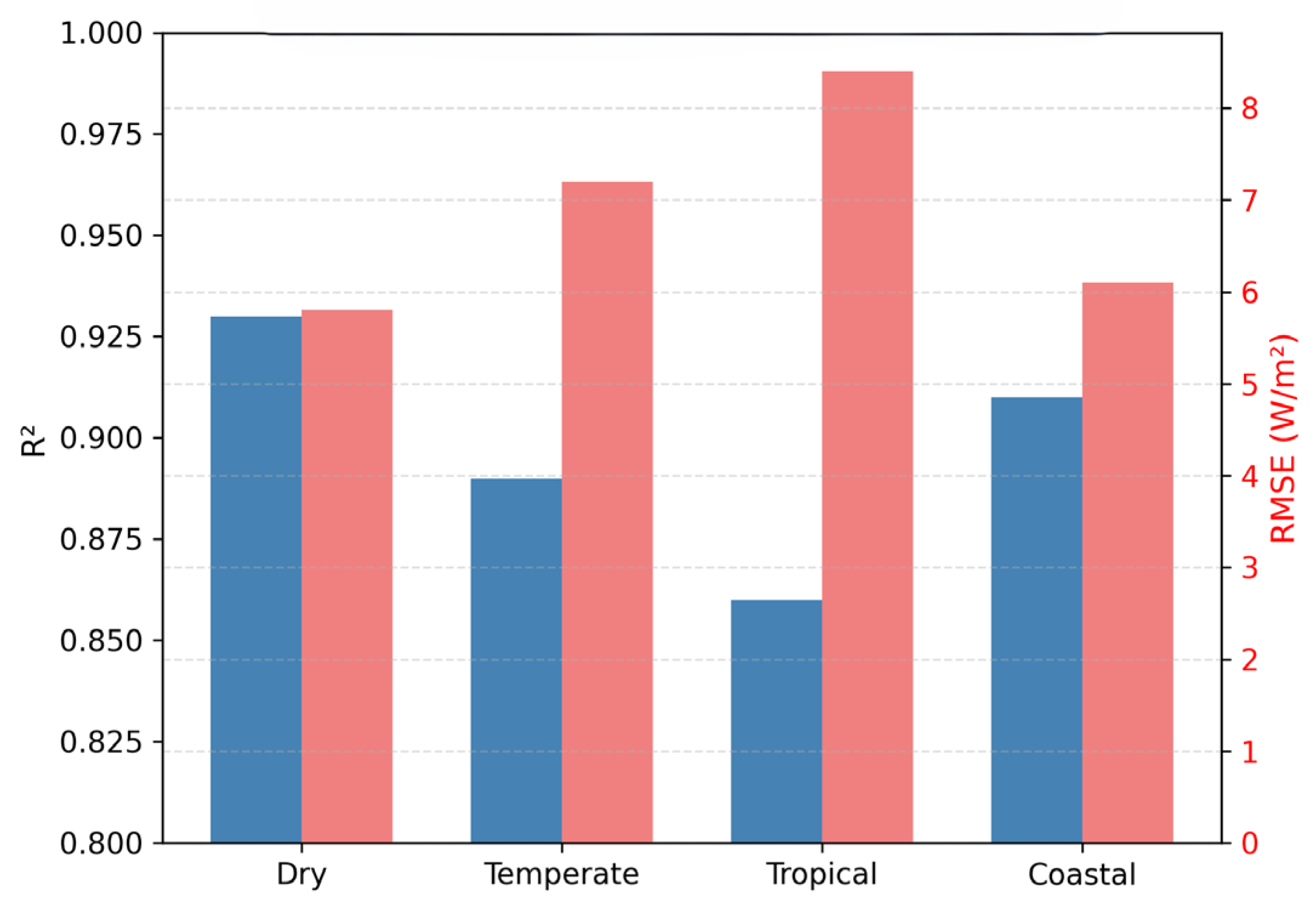

3.2. Spatial and Regional Validation of the DNN Model

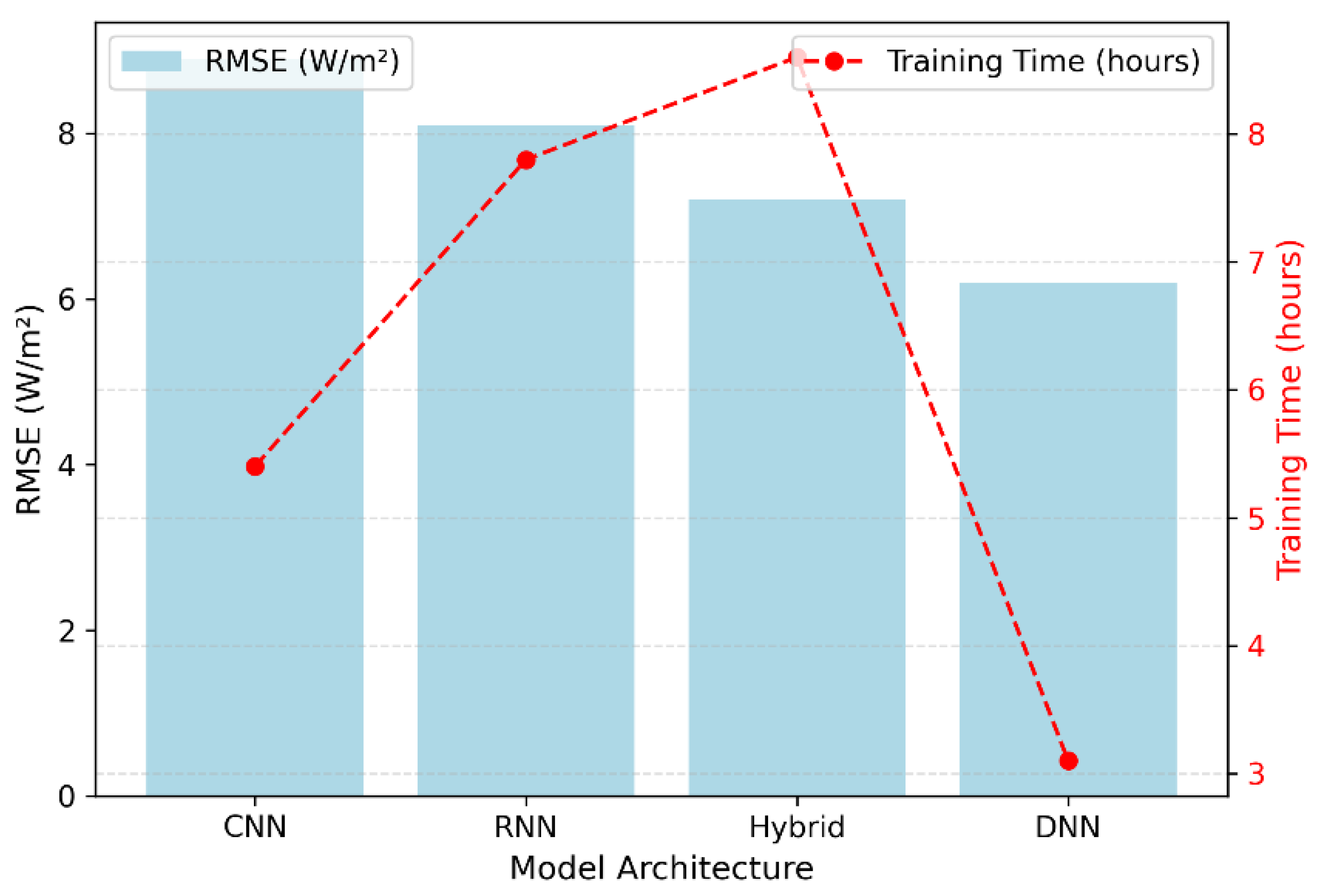

3.3. Comparative Analysis of Neural Architectures

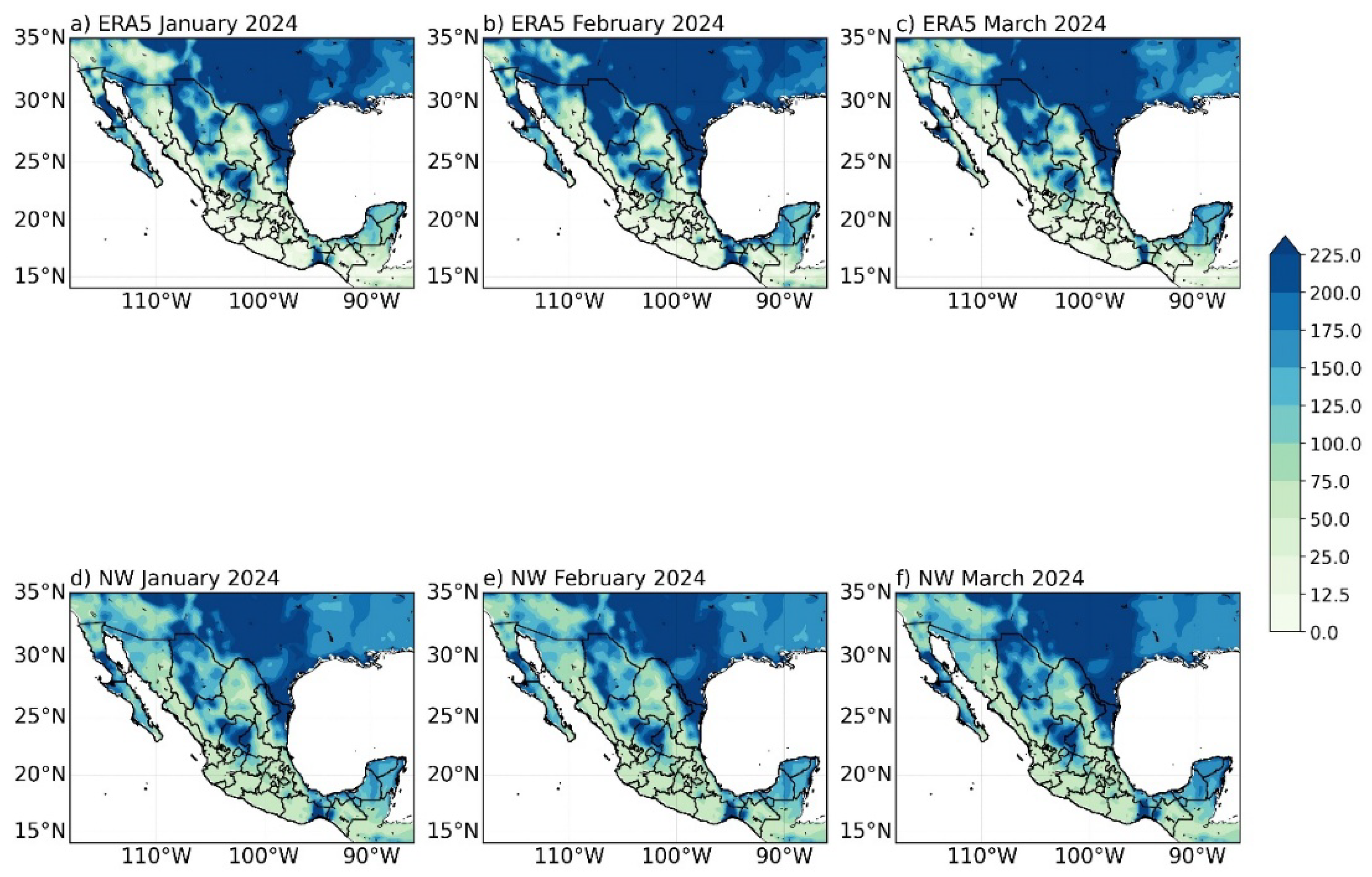

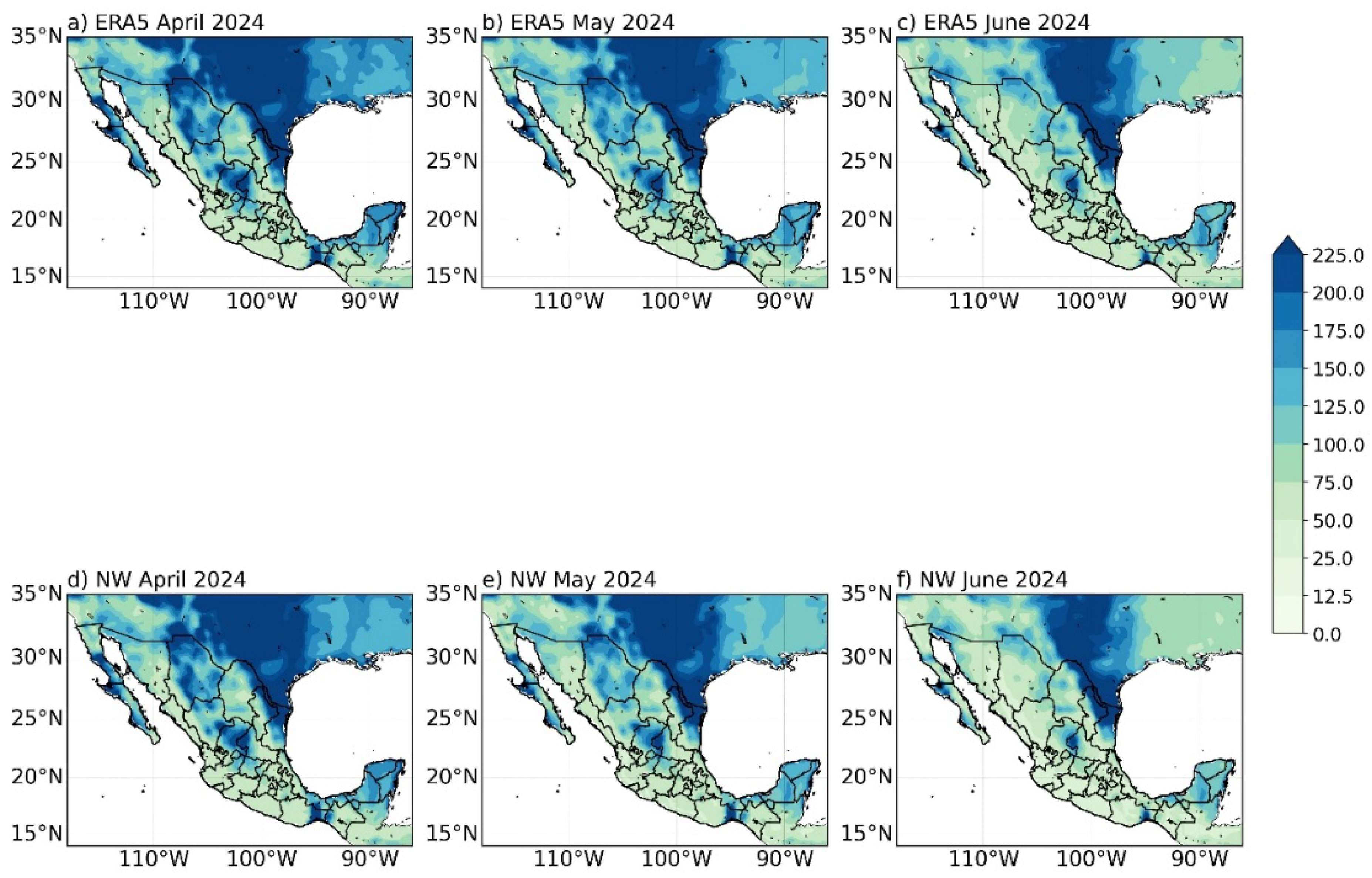

3.4. Generalization and Forecasting Performance on Unseen Data

3.5. Computational Efficiency and Scalability

- Reduced architectural depth, which minimizes parameter count and memory access.

- Adaptive optimization (Adam–RMSProp) that converges faster than classical stochastic gradient descent (SGD).

- Input harmonization, which ensures consistent variable scaling and reduces computational overhead during batch processing.

4. Results

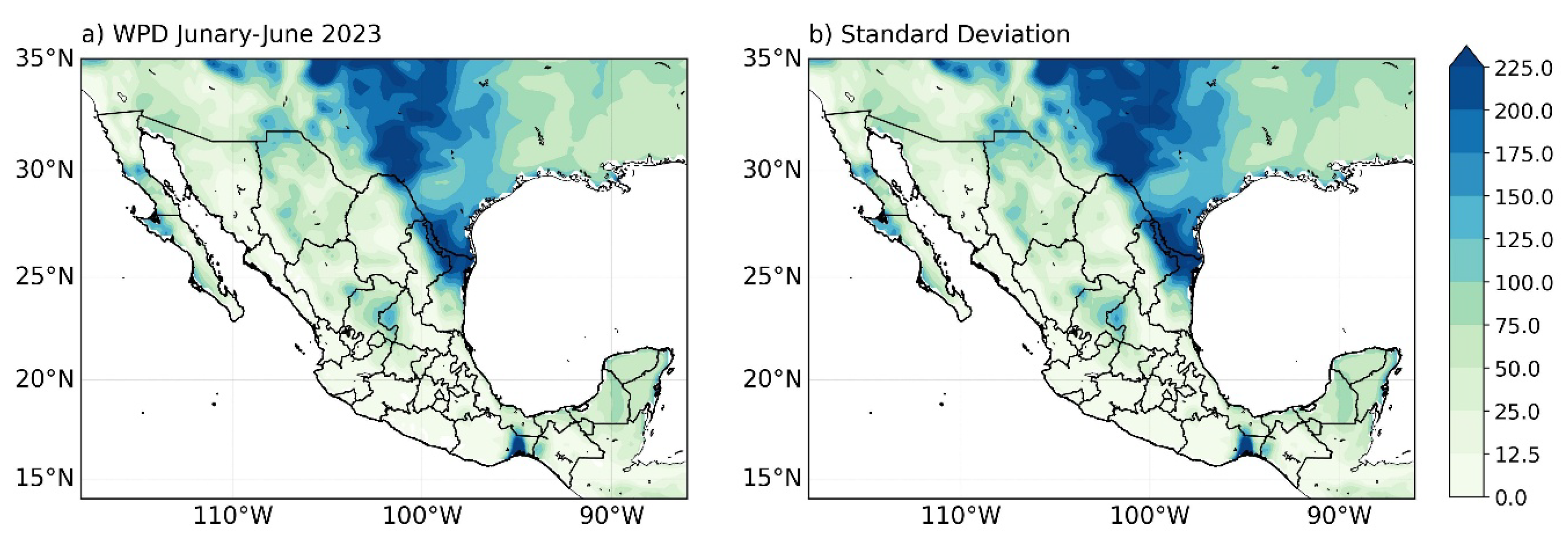

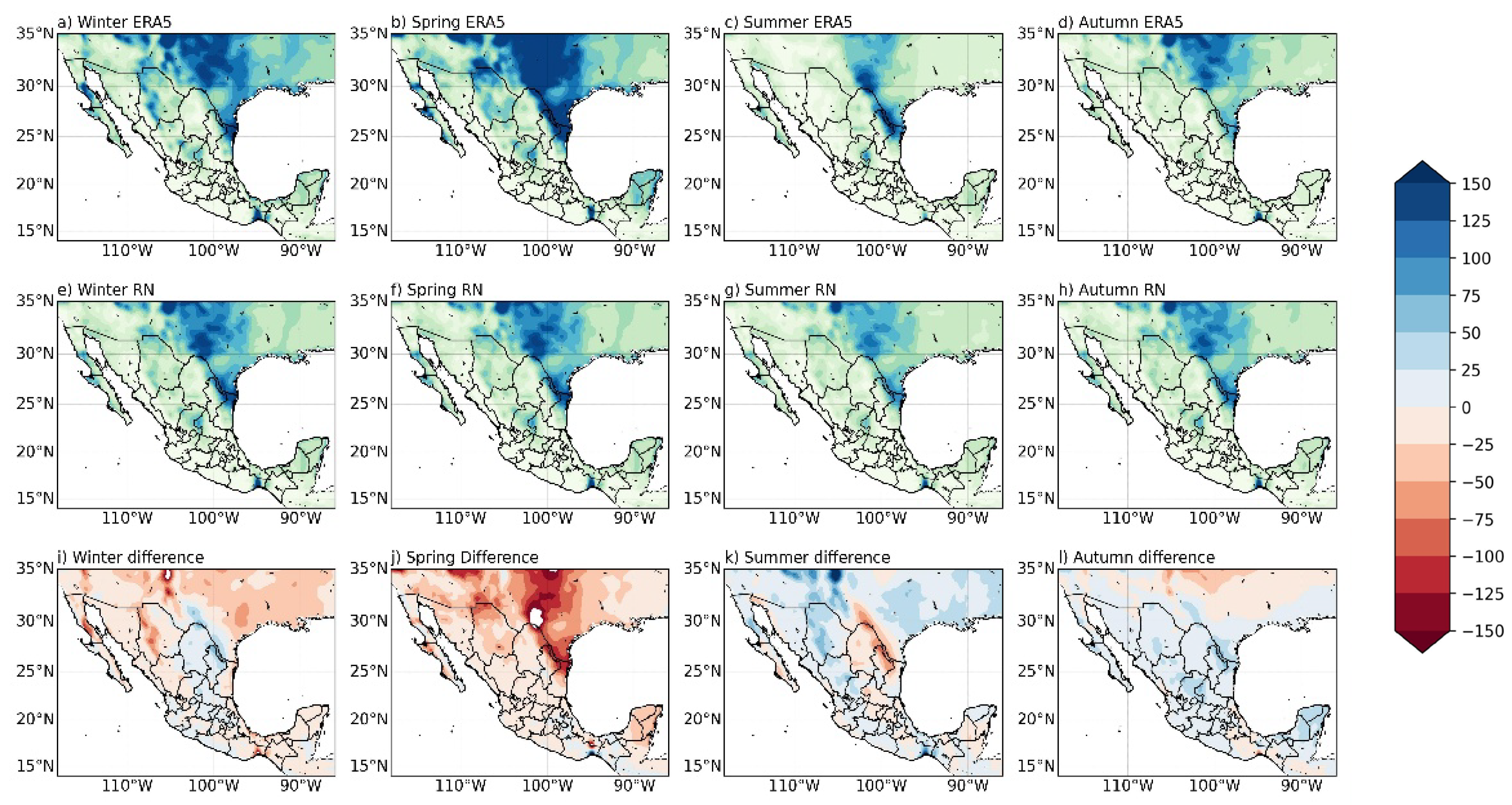

4.1. Reproduction of Spatial Patterns and Regional Coherence

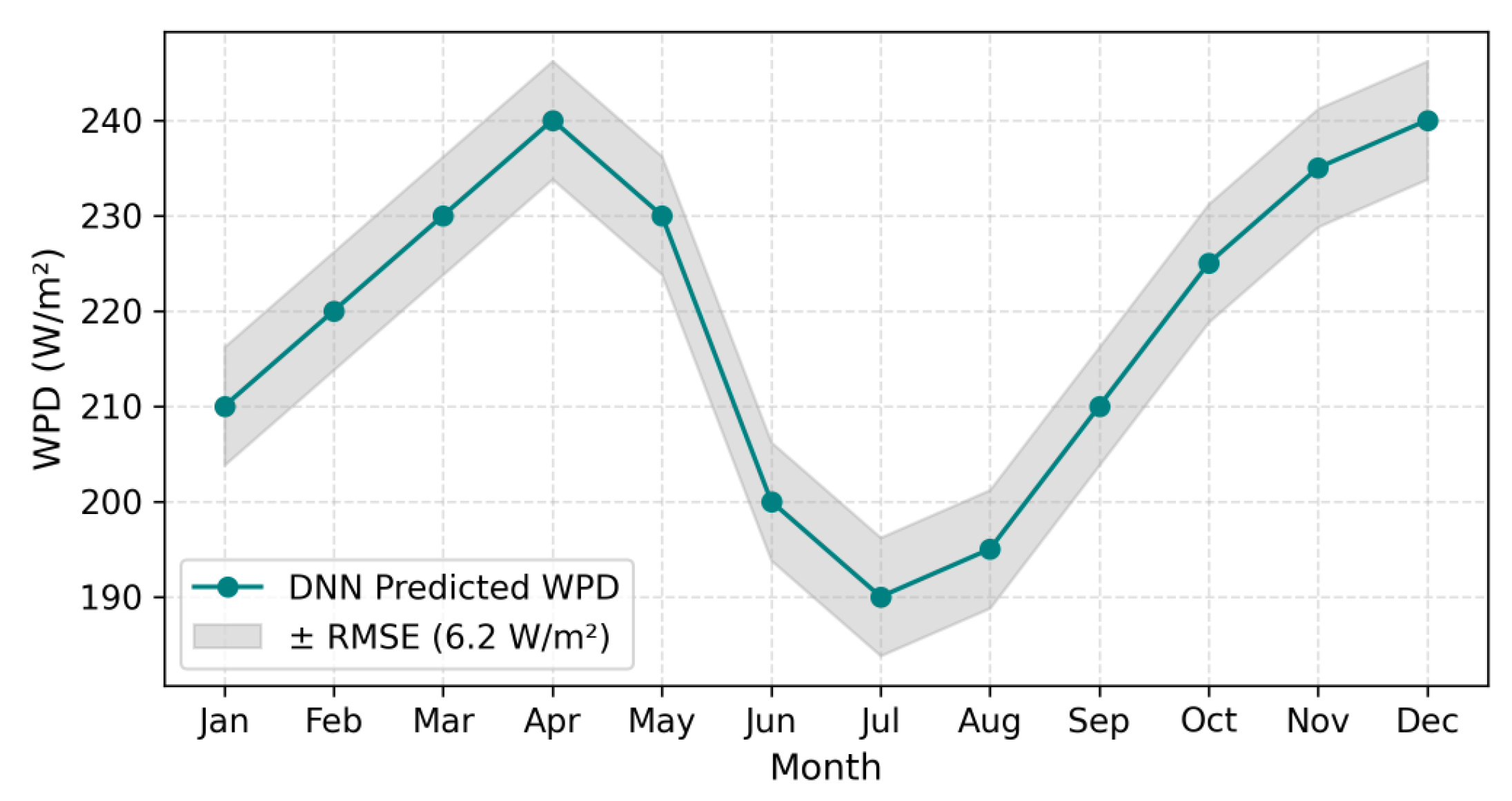

4.2. Reproduction of Temporal Variability

4.3. Performance in Completely Unobserved Periods

- The model does not exceed or replace the physical accuracy of ERA5 or ERA5-Land.

- Its purpose is to generate values that are statistically equivalent to those of the reanalyses.

- The error in our predictions is consistent with and comparable to the inherent uncertainty of the reanalysis itself.

4.4. Computational Advantage and Operational Utility

- Reproduces the spatial and temporal characteristics of ERA5,

- Maintains statistical consistency without introducing systematic biases,

- Provides forward projections with error magnitudes equivalent to the reanalysis, and

- Significantly reduces computation time and energy consumption.

5. Discussions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| WPD | Wind Power Density |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Networks |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Networks |

| DNN | Dense Neural Networks |

| MLP | Multilayer Perceptron |

| WRF | Weather Research and Forecasting Model |

| ReLU | Rectified Linear Unit |

| ERA | European REanalysis |

| CDS | Copernicus Climate Data Store |

Appendix A

Appendix B. Data Preprocessing and Harmonization Workflow

| import xarray as xr import numpy as np import pandas as pd from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler import tensorflow as tf def prepare_netcdf_time_series(nc_file, variables, target_var, time_steps = 24, val_size = 0.15, test_size = 0.15, lat_range = None, lon_range = None): “““ Prepares NetCDF data optimized for climate time series models Args: nc_file: str—path to NetCDF file variables: list—variables de entrada (ej: [‘temperature’, ‘humidity’, ‘pressure’]) target_var: str—target variable (e.g., ‘temperature_2m’) time_steps: int—time window for the model val_size, test_size: float—proportions for validation and testing lat_range, lon_range: tuple—range of coordinates to filter “““ # Cargar datos NetCDF optimizado ds = xr.open_dataset(nc_file, chunks = {‘time’: 1000}) # chunking para eficiencia # Filtrar por coordenadas si se especifica if lat_range: ds = ds.sel(lat = slice(lat_range[0], lat_range[1])) if lon_range: ds = ds.sel(lon = slice(lon_range[0], lon_range[1])) # Convertir a DataFrame optimizado print(“Procesando datos NetCDF…”) # Seleccionar punto específico o promedio espacial if len(ds.lat) > 1 or len(ds.lon) > 1: # Promedio espacial para series temporales data_dict = {} for var in variables + [target_var]: if var in ds.data_vars: # Promedio sobre lat/lon manteniendo tiempo data_dict[var] = ds[var].mean(dim = [‘lat’, ‘lon’], skipna = True).values df = pd.DataFrame(data_dict, index = ds.time.values) else: # Extraer datos de un punto único data_dict = {} for var in variables + [target_var]: if var in ds.data_vars: data_dict[var] = ds[var].squeeze().values df = pd.DataFrame(data_dict, index = ds.time.values) ds.close() # Liberar memoria # Limpiar NaN df = df.dropna() print(f”Datos procesados: {len(df)} muestras temporales”) # División TEMPORAL estricta (importante para series climáticas) n_samples = len(df) test_split = int(n_samples * (1—test_size)) val_split = int(test_split * (1—val_size)) train_data = df.iloc[:val_split] val_data = df.iloc[val_split:test_split] test_data = df.iloc[test_split:] print(f”Division temporal:”) print(f” Train: {len(train_data)} ({train_data.index[0]} to {train_data.index[−1]})”) print(f” Val: {len(val_data)} ({val_data.index[0]} to {val_data.index[−1]})”) print(f” Test: {len(test_data)} ({test_data.index[0]} to {test_data.index[−1]})”) return train_data, val_data, test_data, df def create_netcdf_sequences(data, features, target, time_steps, scaler = None, fit_scaler = False): “”” Crea secuencias temporales optimizadas para datos climáticos “”” X, y = [], [] feature_data = data[features].values target_data = data[target].values # Escalado INDEPENDIENTE para evitar data leakage if fit_scaler: scaler = StandardScaler() feature_data = scaler.fit_transform(feature_data) else: feature_data = scaler.transform(feature_data) # Crear secuencias superpuestas for i in range(time_steps, len(feature_data)): X.append(feature_data[i-time_steps:i]) y.append(target_data[i]) X = np.array(X) y = np.array(y) print(f”Secuencias creadas: X{X.shape}, y{y.shape}”) return X, y, scaler # USO OPTIMIZADO def prepare_climate_training_data(nc_path, config): “”” Función principal para preparar datos climáticos de NetCDF “”” # Cargar y dividir datos train_data, val_data, test_data, full_df = prepare_netcdf_time_series( nc_file = nc_path, variables = config[‘input_vars’], target_var = config[‘target_var’], time_steps = config[‘time_steps’], val_size = config[‘val_size’], test_size = config[‘test_size’], lat_range = config.get(‘lat_range’), lon_range = config.get(‘lon_range’) ) # Crear escalador SOLO con datos de entrenamiento scaler = StandardScaler() scaler.fit(train_data[config[‘input_vars’]]) # Crear secuencias X_train, y_train, _ = create_netcdf_sequences( train_data, config[‘input_vars’], config[‘target_var’], config[‘time_steps’], scaler = scaler, fit_scaler = False ) X_val, y_val, _ = create_netcdf_sequences( val_data, config[‘input_vars’], config[‘target_var’], config[‘time_steps’], scaler = scaler, fit_scaler = False ) X_test, y_test, _ = create_netcdf_sequences( test_data, config[‘input_vars’], config[‘target_var’], config[‘time_steps’], scaler = scaler, fit_scaler = False ) # Verificar que no hay data leakage assert len(set(train_data.index) & set(val_data.index)) == 0, “DATA LEAKAGE en validación!” assert len(set(train_data.index) & set(test_data.index)) == 0, “DATA LEAKAGE en test!” dataset_info = { ‘input_shape’: (config[‘time_steps’], len(config[‘input_vars’])), ‘train_samples’: len(X_train), ‘val_samples’: len(X_val), ‘test_samples’: len(X_test), ‘feature_names’: config[‘input_vars’], ‘target_name’: config[‘target_var’], ‘scaler’: scaler } return (X_train, y_train, X_val, y_val, X_test, y_test), dataset_info # CONFIGURACIÓN EJEMPLO config = { ‘input_vars’: [‘temperature_2m’, ‘relative_humidity_2m’, ‘surface_pressure’, ‘u_component_of_wind_10m’, ‘v_component_of_wind_10m’], ‘target_var’: ‘temperature_2m’, ‘time_steps’: 24, # 24 horas para predecir siguiente paso ‘val_size’: 0.15, ‘test_size’: 0.15, ‘lat_range’: (40.0, 45.0), # Opcional: filtrar región ‘lon_range’: (-10.0, 5.0) } # Ejecutar preparación training_data, info = prepare_climate_training_data(‘datos_climaticos.nc’, config) print(f”\n☑ Preparación completada:”) print(f” - Train: {info[‘train_samples’]} secuencias”) print(f” - Val: {info[‘val_samples’]} secuencias”) print(f” - Test: {info[‘test_samples’]} secuencias”) print(f” - Input shape: {info[‘input_shape’]}”) |

References

- Escamilla-García, P.E.; López, R.; Jiménez, D. A review of the progress and potential of energy generation from renewable sources in Latin America. Lat. Am. Res. Rev. 2023, 58, 383–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Escobedo, Q.; Saldaña-Flores, R.; Rodríguez-García, E.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Wind energy resource in Northern Mexico. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 32, 890–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Escobedo, Q. Wind energy assessment for small urban communities in the Baja California Peninsula, Mexico. Energies 2016, 9, 805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, H.; López, M.; García, J. Wind atlas for Mexico (WAM) Observational Wind Atlas. DTU Wind Energy. 2022. Available online: https://orbit.dtu.dk/en/publications/wind-atlas-for-mexico-wam-observational-wind-atlas (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- Felix, A.; Mendoza, E.; Chávez, V.; Silva, R.; Rivillas-Ospina, G. Wave and wind energy potential including extreme events: A case study of Mexico. J. Coast. Res. 2018, 85, 1336–1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboita, M.S.; Amaro, T.R.; de Souza, M.R. Winds: Intensity and power density simulated by RegCM4 over South America in present and future climate. Clim. Dyn. 2018, 51, 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reichstein, M.; Camps-Valls, G.; Stevens, B.; Jung, M.; Denzler, J.; Carvalhais, N.; Prabhat, F. Deep learning and process understanding for data-driven Earth system science. Nature 2019, 566, 195–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, H.; Khan, M.; Rauf, A. Design possibilities and challenges of DNN models: A review on the perspective of end devices. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2022, 55, 5109–5167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersbach, H.; Bell, B.; Berrisford, P.; Hirahara, S.; Horányi, A.; Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Nicolas, J.; Peubey, C.; Radu, R.; Schepers, D.; et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Q. J. R. Meteorol. Soc. 2020, 146, 1999–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Sabater, J.; Dutra, E.; Agustí-Panareda, A. ERA5-Land: A state-of-the-art global reanalysis dataset for land applications. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 4349–4383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Caballero, M.; López-González, J.; Salles, P.; Appendini, C.M. Wind Energy Potential Assessment for Mexico’s Yucatecan Shelf. Energy Sustain. Dev. 2023, 74, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawadogo, W.; Dosio, A.; Giorgi, F.; Sylla, M.B.; Tamoffo, A.T.; Akumaga, U. Current and future potential of solar and wind energy over Africa using the RegCM4 CORDEX-CORE ensemble. Clim. Dyn. 2021, 57, 1647–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merizzi, F.; Bessagnet, B.; Guevara, M. Wind speed super-resolution and validation: From ERA5 to CERRA via diffusion models. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 21899–21921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ouali, A.; Lakhal, Y.; Benchagra, M.; Hamid, H.; Mohamed, M.V.O. Robust Control for DFIG-Based WECS with ANN-Based MPPT. Sol. Energy Sustain. Dev. J. 2025, 14, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Zhang, L.; Chen, L. Estimating hub-height wind speed based on a machine learning algorithm: Implications for wind energy assessment. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2023, 23, 3181–3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lou, H.; Wu, J.; Zhang, S.; Gao, S. A survey on wind power forecasting with machine learning approaches. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 12753–12773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelsattar, M.; Ismeil, M.A.; Menoufi, K.; AbdelMoety, A.; Emad-Eldeen, A. Evaluating Machine Learning and Deep Learning models for predicting Wind Turbine power output from environmental factors. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0317619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murugan, G.; Li, H.; Tang, Y. A novel CNN method for the accurate spatial data recovery from digital images. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 80, 1706–1712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J.S.; Kang, J.; Kim, J.J.; Jeon, K.W.; Chung, H.J.; Park, B.H. Neural architecture search survey: A computer vision perspective. Sensors 2023, 23, 1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Zhao, X.; Chen, Y. A hybrid deep learning algorithm and its application to streamflow prediction. J. Hydrol. 2021, 601, 126636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Roy, A.; Kar, S. Recurrent neural networks (RNNs): Architectures, training tricks, and introduction to influential research. In Machine Learning for Brain Disorders; Humana: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 117–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G. A comprehensive review of deep learning: Architectures, recent advances, and applications. Information 2024, 15, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Velázquez, M.I.; Pacheco, L.; Rivera, J. Evaluating reanalysis and satellite-based precipitation at regional scale: A case study in southern Mexico. Atmósfera 2021, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y. Quantitative insights into the differences of variability and intermittency between wind and solar resources on spatial and temporal scales in China. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2021, 13, 043307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messner, J.W.; Pinson, P.; Browell, J.; Bjerregård, M.B.; Schicker, I. Evaluation of wind power forecasts—An up-to-date view. Wind. Energy 2020, 23, 1461–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Chen, J.; Wang, Q.; Chen, D.Z.; Wu, J. Team up gbdts and dnns: Advancing efficient and effective tabular prediction with tree-hybrid mlps. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Barcelona, Spain, 25–29 August 2024; pp. 3679–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheepens, D.R.; Schicker, I.; Hlaváčková-Schindler, K.; Plant, C. Adapting a deep convolutional RNN model with imbalanced regression loss for improved spatio-temporal forecasting of extreme wind speed events in the short to medium range. Geosci. Model Dev. 2023, 16, 251–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, Y. Deep learning tool: Reconstruction of long missing climate data based on multilayer perceptron (MLP). Environ. Softw. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rugg, A.; Cannon, F.; Pierce, D.W.; Cayan, D.R. Mass-Conserving Downscaling of Climate Model Precipitation Over Mountainous Terrain for Water Resource Applications. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2023, 50, e2023GL105326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Cao, Z.; Wang, F.; Ngu, S.S.; Kho, L.C.; Cai, H. Design of Optimal Pitch Controller for Wind Turbines Based on Back-Propagation Neural Network. Energies 2024, 17, 4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nahrstedt, F. An Empirical Study on the Energy Usage and Performance of Pandas and Polars Data Analysis Python Libraries. In Proceedings of the 28th International Conference on Evaluation and Assessment in Software Engineering, Salerno, Italy, 18–21 June 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wang, L.; Zhou, F. Deep network approximation: Beyond ReLU to diverse activation functions. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2024, 25, 1–39. Available online: https://jmlr.org/papers/v25/23-0912.html (accessed on 15 November 2025).

- Mfetoum, I.M.; Djimeli, M.; Fotsing, M.; Tchawoua, C.; Ntep, F. A multilayer perceptron neural network approach for optimizing solar irradiance forecasting in Central Africa with meteorological insights. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, M.A.; Machado, M.Z.; Pérez, M.R.; Salgado, O.J.; Martinez, C.M. Automatic Detection of Dynamic Wind Conditions in Mexican California: A Machine Learning-Driven Advancement in Wind Management. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2025, 23, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Tian, Q.; Guo, J.; Xu, C.; Xu, C. A Survey on Vision Transformer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, Y.; Rho, D. A Design of the Real-Time Simulation for Wind Turbine Based on Artificial Neural Network Techniques Using SCADA Data. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2023, 18, 3277–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheridan, L.M.; Krishnamurthy, R.; Medina, G.G.; Gaudet, B.J.; Gustafson, W.I. Offshore reanalysis wind speed assessment across the wind turbine rotor layer off the United States Pacific coast. Wind. Energy Sci. 2022, 7, 2059–2084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olauson, J. ERA5: The new champion of wind power modelling? Renew. Energy 2018, 126, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gualtieri, G. Analysing the uncertainties of reanalysis data used for wind resource assessment: A critical review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jourdier, B. Evaluation of ERA5, MERRA-2, COSMO-REA6, NEWA and AROME to simulate wind power production over France. Adv. Sci. Res. 2020, 17, 63–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coppola, E.; Giorgi, F.; Giuliani, G.; Pichelli, E.; Ciarlo, J.M.; Raffaele, F.; Nogherotto, R.; Reboita, M.S.; Lu, C.; Zazulie, N.; et al. The 5th generation regional climate modeling system, RegCM5: The first convection-permitting European wide simulation and validation over the CORDEX-CORE domains. Clim. Dyn. 2025, 63, 428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E. Mexico sets climate targets. Nature 2012, 484, 7395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camastra, F.D.; Vallejo, R.G. Inteligencia artificial, sostenibilidad e impacto ambiental. Un estudio narrativo y bibliométrico. Región Científica 2025, 4, 2025355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Metric | Simple DNN (256-128-64) | Optimal DNN (512-256-128) | Deep DNN (1024-512-256-128) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R2 (test set) | 0.82–0.85 | 0.90–0.92 | 0.91–0.92 |

| RMSE (W/m2) | 9–11 | 6–7 | 6–7 |

| Training time | 1.8 h | 2.9 h | 5.1 h |

| Energy consumption | 702 Wh | 912 Wh | 1740 Wh |

| Model | Activation | R2 | RMSE (W/m2) | Training Time (min) | Memory (GB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNN (this study) | ReLU | 0.91 | 6.2 | 85 | 12 |

| CNN | ReLU | 0.87 | 7.9 | 130 | 24 |

| RNN (GRU) | tanh | 0.84 | 8.5 | 205 | 20 |

| CNN–RNN Hybrid | ReLU + tanh | 0.90 | 6.4 | 210 | 48 |

| Metrics | Validation (70/20) | Blind Test (10%, 2021–2024) |

|---|---|---|

| R2 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| RMSE (W/m2) | 6.2 | 6.8 |

| MAE (W/m2) | 4.8 | 5.2 |

| Average bias (DNN − ERA5, W/m2) | −0.8 | −1.1 |

| Number of samples | 19.73 × 106 |

| Model | Architecture | R2 | RMSE (W/m2) | MAE (W/m2) | Training Time (h) | Energy (kWh) | Relative Energy Use (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | 4 Conv + 2 Dense | 0.86 | 8.4 | 6.9 | 48 | 25.92 | 100% |

| RNN–GRU | 2 GRU + 2 Dense | 0.88 | 7.8 | 6.1 | 62 | 33.48 | 129% |

| Hybrid CNN–RNN | 2 Conv + 1 LSTM + 2 Dense | 0.93 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 72 | 38.88 | 150% |

| DNN (Proposed) | 3 Dense (512-256-128) | 0.91 | 6.2 | 4.8 | 25 | 13.50 | 52% |

| Validation Period | Temporal Scale | R2 | RMSE (W/m2) | Mean Bias (%) | Relative Error (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 (Seasonal) | Seasonal | 0.91 | 6.3 | +2.1 | 4.8 |

| 2024 (Seasonal) | Seasonal | 0.90 | 6.5 | −1.8 | 5.0 |

| Jan–Mar 2024 | Monthly | 0.89 | 6.8 | −2.4 | 5.5 |

| Apr–Jun 2024 | Monthly | 0.90 | 6.4 | +1.9 | 5.1 |

| Overall Average | — | 0.90 | 6.5 | ±2.1 | 5.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molina-Almaraz, M.; Solís-Sánchez, L.O.; Bañuelos-García, L.E.; Castañeda-Miranda, C.L.; Guerrero-Osuna, H.A.; García-Sánchez, E. Efficient Neural Modeling of Wind Power Density for National-Scale Energy Planning: Toward Sustainable AI Applications in Industry 5.0. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413000

Molina-Almaraz M, Solís-Sánchez LO, Bañuelos-García LE, Castañeda-Miranda CL, Guerrero-Osuna HA, García-Sánchez E. Efficient Neural Modeling of Wind Power Density for National-Scale Energy Planning: Toward Sustainable AI Applications in Industry 5.0. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413000

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolina-Almaraz, Mario, Luis Octavio Solís-Sánchez, Luis E. Bañuelos-García, Celina L. Castañeda-Miranda, Héctor A. Guerrero-Osuna, and Eduardo García-Sánchez. 2025. "Efficient Neural Modeling of Wind Power Density for National-Scale Energy Planning: Toward Sustainable AI Applications in Industry 5.0" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413000

APA StyleMolina-Almaraz, M., Solís-Sánchez, L. O., Bañuelos-García, L. E., Castañeda-Miranda, C. L., Guerrero-Osuna, H. A., & García-Sánchez, E. (2025). Efficient Neural Modeling of Wind Power Density for National-Scale Energy Planning: Toward Sustainable AI Applications in Industry 5.0. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13000. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413000