Abstract

This paper presents a proof-of-concept for a natural-language-based closed-loop controller that regulates the temperature of a simple single-input single-output (SISO) thermal process. The key idea is to express a relay-with-hysteresis policy in plain English and let a local large language model (LLM) interpret sensor readings and output a binary actuation command at each sampling step. Beyond interface convenience, we demonstrate that natural language can serve as a valid medium for modeling physical reality and executing deterministic reasoning in control loops. We implement a compact plant model and compare two controllers: a conventional coded relay and an LLM-driven controller prompted with the same logic and constrained to a single-token output. The workflow integrates schema validation, retries, and a safe fallback, while a stepwise evaluator checks agreement with the baseline. In a long-horizon (1000-step) simulation, the language controller reproduces the hysteresis behavior with matching switching patterns. Furthermore, sensitivity and ablation studies demonstrate the system’s robustness to measurement noise and the LLM’s ability to correctly execute the hysteresis policy, thereby preserving the theoretical robustness inherent to this control law. This work demonstrates that, for slow thermal dynamics, natural-language policies can achieve comparable performance to classical relay systems while providing a transparent, human-readable interface and facilitating rapid iteration.

1. Introduction

Control systems are traditionally specified through mathematical equations or imperative code. However, in many real-world scenarios, such as industrial ovens, HVAC systems, or laboratory equipment, control policies are often described verbally by operators: Turn the heater on if it’s too cold; turn it off if it’s too hot; otherwise, keep the last action. This linguistic gap between human intent and machine execution presents an opportunity for more intuitive, transparent, and accessible control interfaces.

Recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have enabled the interpretation of natural-language instructions with high accuracy and contextual awareness. These models can now be embedded into closed-loop systems, acting as interpreters of verbal policies and generating control actions in control loop time. This paradigm shift opens new possibilities for rapid prototyping, educational tools, and low-risk industrial applications where transparency and explainability are valued.

The novelty of this work lies in demonstrating that natural language can serve not only as a descriptive interface, but also as a functional medium for modeling physical reality and performing automatic reasoning. By embedding a verbal relay policy into a local LLM and constraining its outputs via schema validation, we show that the model can regulate a thermal process with performance comparable to a conventional hysteresis controller, maintaining stability over long horizons and demonstrating robustness against sensor noise.

The first contribution of this paper is to prove that a natural-language policy can be executed deterministically using schema-constrained outputs and greedy decoding. The second is a validation of the LLM controller against a classical baseline in a simulation, supported by sensitivity and ablation studies that confirm the necessity of the natural-language memory mechanism for preventing actuator chatter. Finally, we propose a practical architecture with retries, validation, and fallback mechanisms that ensure safe operation. This approach offers a transparent, auditable interface for control logic and lays the groundwork for future hybrid supervisory systems that combine human-readable policies with formal guarantees.

2. Related Work

Natural-language-based closed-loop control uses large language models (LLMs) to translate high-level instructions into control actions in control loop time. Instead of hand-crafting controllers, an engineer can write policies in plain English (“if the room is too warm, decrease fan speed; if occupancy increases, prefer comfort over energy”) and have the system enact them with feedback from sensors. Recent work in buildings and automation shows that LLMs can bridge human intent and machine execution by grounding natural language into verifiable control code, supervisory constraints, and explainable decisions [1,2,3,4,5]. In robotics, generalist Vision Language Action (VLA) models further extend this idea by mapping language and perception directly to actions [6,7].

Two enablers make this practical. First, edge-side deployment and latency-aware serving are improving, which matters for real-time control [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Second, verification and safety pipelines are emerging to translate natural language into temporal logic, check constraints, and filter unsafe outputs before actuation [14,15,16,17]. Together, these trends enable LLMs to act as direct controllers, members of agentic control loops, or supervisory layers atop PID/MPC.

2.1. Expressing Control Logic in Natural Language

A core challenge is turning ambiguous language into deterministic control actions. Interactive translators convert natural language into Signal/Linear Temporal Logic, letting engineers verify and simulate policies prior to deployment [14,15]. On the code side, LLMs now generate IEC 61131-3 Structured Text for PLCs while incorporating compiler feedback and retrieval of vendor-specific libraries [4,18,19]. Iterative workflows use static checks, compilers, and model checkers to stabilize outputs before execution [3]. Even test cases for control logic can be synthesized automatically to probe edge conditions [20].

Explainability is equally important in building Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning (HVAC), LLMs have been used to narrate why control decisions were produced (e.g., “raise supply air temperature due to low occupancy and high outside temperature”), improving trust in machine-learning control [2]. Fault detection studies similarly leverage LLMs to contextualize anomalies in familiar terms for operators [21]. These practices are consistent with VLA and embodied-agent lines in robotics, where language supplies global structure while low-level controllers enforce safety envelopes [6,7].

Because control is safety-critical, outputs must be constrained. Recent surveys and guidelines emphasize prompt-injection defenses, sandboxing tools, and defense-in-depth for agent workflows used in automation settings [22,23,24,25,26,27]. These patterns, schema-restricted outputs, external validators, and NL to logic compilers, are becoming de facto “protective barriers” for language-conditioned control [3,14,15].

2.2. Architectures for Closed-Loop Operation

Three design families dominate:

- Direct language controllers: In robotics and teleoperation, language can drive behaviors directly when paired with perception and skills libraries. Recent teleoperation systems let a human directly control one arm while issuing natural-language commands to an assistive arm, demonstrating reliable closed-loop sharing of autonomy [28,29]. Generalist VLAs show how text + vision can map to actions across embodiments, suggesting a path to language-guided regulation in multi-sensor settings [6,7].

- Agentic loops: In industrial automation, multi-agent frameworks orchestrate planning, code synthesis, verification, and execution. Agents4PLC automates PLC code generation with built-in verification and closed-loop evaluation, reducing integration burden for common control tasks [5]. Benchmarks such as TaskBench evaluate tool use, decomposition, and parameter prediction skills that matter when LLM agents must call simulators or optimizers within the loop [30]. Memory-augmented embodied agents further retain task histories to refine future decisions [31].

- Supervisory hybrids: Rather than replacing PID/MPC, LLMs often supervise them. In instructive frameworks, the LLM maps free-form context (e.g., “unexpected occupancy surge at 16:00”) to disturbance forecasts or cost weight adjustments consumed by MPC, achieving context-aware control with theoretical guarantees on regret or convergence [32,33,34]. In building engineering, LLMs have already automated EnergyPlus model creation from natural descriptions, accelerating simulation-in-the-loop controller design [1].

2.3. Real-Time and Edge Deployment

Meeting control deadlines requires predictable latency. A recent ACM Computing Surveys article reviews design and serving techniques for edge LLMs, from quantization to pipeline scheduling [8]. Systems papers at USENIX ATC’25 provide concrete building blocks: CLONE co-designs software/hardware for latency-aware inference on edge devices [9], LLMStation multiplexes fine-tuning and serving workloads efficiently [10], and Toppings offloads adapters to the CPU with rank-aware scheduling [11]. For mixed real-time and best-effort traffic, a common pattern in control rooms—hybrid serving reduces RT latency while maintaining throughput [12]. On the OS side, service abstractions for AI pipelines aim to make co-located inference/training more predictable [13]. These advances suggest practical paths for on-premises LLM controllers or supervisors that respect industrial timing constraints.

2.4. Verification, Safety, and Robustness

Formal methods play a central role. SYNTHTL combines LLMs with model checkers to translate natural language into temporal logics and validate the result iteratively, reducing ambiguity before deployment [14]. New datasets and methods improve NL to STL translation quality and diversity, again enabling formal verification of language-conditioned policies [15]. Beyond translation, “neural model checking” and model-checking intermediate languages expand the toolbox for verifying learned or language-defined controllers [16,17].

Security research shows that indirect prompt-injection remains a key risk in agentic pipelines that fetch external documentation or data; state-of-the-art defenses and testing frameworks are being evaluated for robustness under adaptive attacks [22,23,24,25,26,27]. For safety-critical deployments, these practices should complement domain-level guardrails such as set-point limits, rate limiters, and supervisor overrides [3,4].

Unlike agentic workflows that rely on multi-step reasoning or tool invocation, our approach constrains the LLM to a single-token output under strict schema validation, enabling deterministic behavior and simplifying safety guarantees.

2.5. Applications and Evidence

Buildings and HVAC: LLMs have helped automate building energy modeling, enabling faster controller prototyping and scenario testing [1]. Interpretable ML + LLM frameworks generate human-readable rationales for HVAC actions, improving operator trust [2]. A 2025 study in Energies reports simulated energy savings and stability improvements when LLMs are integrated into MPC for temperature/humidity control [35]. Emerging work explores office-in-the-loop AI for HVAC operation [36,37] and LLM-based QA interfaces for sensor-driven HVAC analytics [38]. There is also progress on LLM-assisted building ontologies that link natural language queries with semantic models [39]. Finally, an explainable control framework emphasizes transparent recommendations for building operators [40]. These domains share characteristics with our thermal plant use case, where slow dynamics and binary actuation allow for safe experimentation with language-driven control.

Industrial automation (PLCs): Iterative pipelines now produce PLC code from natural-language specs, refine it via compiler/model-checker feedback, and verify semantics before deployment [3,4]. Fine-tuning with online feedback improves Structured Text generation quality, compilation success, and task coverage [18]. Comparative studies assess language models across representative PLC tasks, offering prompt patterns and metrics for reliability [19]. LLM-generated control test cases can increase coverage for safety checks [20].

Robotics: Teleoperation systems mix direct joystick control with language commands to a partner arm, demonstrating robust closed-loop coordination [28,29]. Generalist VLA policies (e.g., OpenVLA) show that language and vision jointly support manipulation across platforms [6], and recent surveys synthesize how LLMs integrate with robot stacks [7]. Memory-augmented embodied agents further enhance stability over longer tasks [31].

Human-in-the-loop MPC: LLM supervision of MPC is gaining theoretical footing and practical momentum. InstructMPC turns natural-language context into disturbance distributions and fine-tunes in closed loop with regret guarantees [32]. Related formulations cast prompting and preference learning through an MPC lens, aligning free-form language with optimization objectives [33,34].

2.6. Open Challenges and Research Directions

Timing and determinism: Even with quantization and edge serving, hard real-time guarantees remain challenging for long contexts or multi-tool agents. Prioritized inference, adapter offloading, and admission control are promising, but require control-aware service-level objectives [9,10,11,12].

Verification at scale: Scaling NL to logic datasets and closing the loop between natural-language specs, formal verification, and runtime monitors are active areas [14,15,16].

Security of agent workflows: Indirect prompt injection against tool-using agents is still effective under adaptive testing; defense-in-depth and continuous red-teaming will be necessary for deployments in plants and buildings [22,23,24,25,26,27].

Benchmarks and reporting: Standardized evaluations for language-conditioned control should measure stability, energy, comfort/safety, latency, and operator trust, with realistic tools and disturbances. TaskBench-style methodologies can be adapted for control contexts [30].

From prototypes to practice: Case studies in HVAC and PLCs show feasibility, but cross-site validation, commissioning processes, and maintenance workflows need documentation and shared assets [1,2,3,35].

Overall, the field is maturing quickly. With practical guardrails, formalization, and latency-aware serving, natural-language control can become a usable interface above proven control schemes—not a replacement, but a transparent supervisory layer that lowers the barrier from intent to safe actuation.

While prior work has explored the use of LLMs for code generation, supervisory control, and explainable automation, few studies have demonstrated that natural language itself can serve as a direct and deterministic control policy in closed-loop systems. This work contributes a minimal yet rigorous proof-of-concept where a verbal relay logic is executed by an LLM with schema-constrained outputs, validating its equivalence to a conventional hysteresis controller. Our results suggest that natural language can model physical reality and support real-time reasoning in control loops, bridging human intent and machine execution without intermediate code synthesis.

3. Materials and Methods

This section specifies the plant, controllers, language interface, validation pipeline, and experimental protocol in a way that enables replication. The research question is whether a control policy written in plain English can be executed reliably by a large language model (LLM) to regulate a slow thermal plant in closed loop. The target outcome is to reproduce the behavior of a conventional relay with hysteresis when the language output is strictly constrained and validated.

Runtime setup: We use a local LLM served by Ollama (e.g., llama3:{size}). Ollama inference parameters enforce determinism: greedy decoding (temperature = 0) and a single-token budget (num_predict = 1). Outputs must match the regular expression ^[01]$. All experiments run on a desktop-class CPU (GPU not required). For noise experiments, randomness can be fixed with rng(1).

3.1. Plant Model and Relay Baseline

Lumped Thermal Model (Discrete Time)

We model the oven as a first-order system updated each seconds:

where is the temperature (in °C) at step k and is a binary heater command (OFF/ON). Here, represents the discrete thermal retention factor for a fixed sampling time . Parameter captures heat retention (how much of persists), while aggregates heater power and losses into a per-step rise when . We use , (Table 1). Note that the discrete model represents the Zero-Order Hold (ZOH) discretization of the continuous thermal process.

Table 1.

Nominal parameters and initial conditions (baseline scenario).

Why Equation (1)? It is the minimal model that captures the dominant oven physics: slow monotonic heating when the heater is ON and slow cooling when it is OFF. It is stable for and admits a fixed point (steady-state equilibrium) under constant actuation:

Equation (2) demonstrates the physical reachability of the control objectives. It confirms that the maximum achievable temperature (when ) exceeds the upper threshold , and the minimum temperature (when ) falls below . This condition is necessary to ensure that the relay logic can physically drive the temperature across the deadband boundaries, resulting in the characteristic sawtooth behavior where rises toward and decays toward .

To justify the choice of discrete parameters, we derive them from a continuous-time physical model . The Zero-Order Hold (ZOH) discretization yields:

Equation (3) demonstrates the link between the discrete simulation model and physical reality. It allows us to tune based on the physical time constant . Thus, our choice of corresponds to a system with slow thermal dynamics (), typical of industrial heating processes, rather than an arbitrary numerical abstraction.

Regulation targets with tolerance , defining a deadband where the controller does not switch:

We use = 150 °C and = 10 °C, i.e., °C.

To prevent chatter, we use a two-threshold policy with memory (hold-last-action):

Why Equation (5)? The inequalities at the boundaries of (4) define deterministic switching surfaces (ON at , OFF at ). The middle branch , implements memory, which suppresses spurious toggles caused by noise or discretization. Combined with (1), the heating/cooling phases yield a bounded sawtooth between y .

3.2. LLM Prompt and Link to the Formal Policy

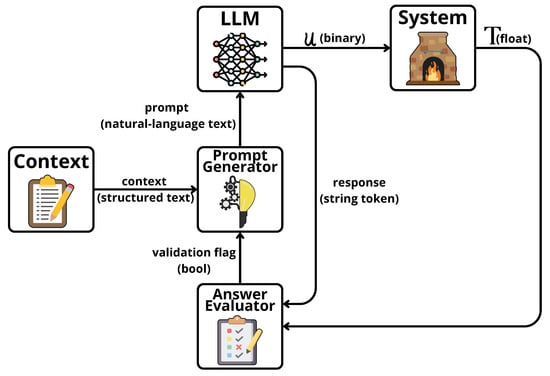

The overall closed-loop architecture is illustrated in Figure 1. It integrates the thermal plant, the context builder, the LLM inference engine, and the safety validator into a feedback loop. The controller runs a local model via Ollama with the following system prompt shown in Listing 1. This text enforces the relay logic in plain English and is the basis for the language-driven controller evaluated in this paper. To mitigate linguistic ambiguity, the system prompt replaces vague terms with explicit numerical thresholds, functioning effectively as the tuning parameters of the controller.

Figure 1.

Closed-loop architecture: The Context assembles the current temperature and the previous action . The Prompt Generator formats the natural language instruction. The LLM emits a deterministic control action , and the System updates the temperature via Equation (1). An Answer Evaluator validates the output schema and triggers the hard-coded fallback mechanism if validation fails.

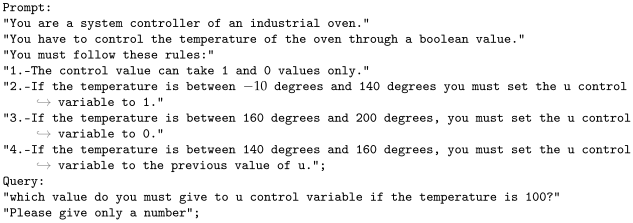

| Listing 1. System prompt. |

|

At each step, the prompt is built from the current temperature and the previous action using the following template. In our implementation we pass (last available reading) to the step prompt (Listing 2), which introduces a one-step decision delay; the coded baseline is evaluated under the same timing for a fair comparison.

| Listing 2. Per-step prompt template. |

|

Formally, we denote this interface by

which makes the language controller causal and aligns its timing with the coded baseline.

Operational semantics and equivalence to Equation (5). The English rules in the system prompt define the same switching law as (5). For determinism and to match the coded baseline, “between” is interpreted with inclusive bounds at the edges of (4):

which is algebraically equivalent to the piecewise policy in (5). Under the plant model (1), this yields the bounded sawtooth response between and .

Decoding & schema: Greedy decoding (); maximum output length token, a response is valid if it matches.

Validator and safe fallback: Each response is checked against the schema. If invalid, the same prompt is retried up to times. If all retries fail, the coded relay (5) supplies the action for that step, guaranteeing a defined command at every cycle.

3.3. Experimental Protocol and Metrics

We simulate steps for stability analysis and steps for detailed sensitivity/ablation studies using the parameters in Table 1. Unless noted otherwise, the plant state evolves under the LLM action according to (1) while the controller applies (5) logically via (7) (coded baseline) or via the LLM outputs validated as above. At each step we log , , , the retry count, a fallback flag, and LLM inference time (ms). We consider four scenarios: baseline step to ; noise injection with , ; parameter sweeps with , ; and an ablation disabling hold-last-action inside .

We quantify equivalence of decisions, switching economy, and regulation quality. With the indicator:

and we report the Entry time as the first k such that , plus LLM latency (mean and 95th percentile). Why these metrics? (8) tests functional equivalence to the baseline; (9) penalizes chatter (wear/energy); (11) and (12) capture regulation and stability inside the deadband; (13) summarizes transient aggressiveness.

3.4. Sensitivity and Ablation Studies

3.5. Generative AI Disclosure

The LLM is part of the experimental control loop under study. The authors reviewed, tested, and validated all outputs and take full responsibility for the results and their interpretation.

4. Results

4.1. Simulation Setup

We evaluate the two controllers on the plant in Equation (1) using the nominal parameters of Table 1. The closed-loop objective is regulation within the deadband defined in Equation (4), i.e., around . The horizon is steps (); initial conditions are and as specified in Section 3.

Both controllers implement the same relay-with-hysteresis logic of Equation (5). The language-driven controller uses the exact prompts listed previously and obeys the interface timing in Equation (6) (decision based on ), so that both controllers observe identical information at each step. The validator enforces the 0/1 schema on the LLM output; if all retries fail, the fallback applies Equation (5) for that step.

4.2. Evaluation Metrics and Procedure

We report the loop-level metrics defined in Equations (8)–(13). Agreement (8) measures functional equivalence between and . Switches (9) penalizes unnecessary toggling (chatter). Band time (11) quantifies how long the process stays within the safety/comfort interval of Equation (4). Dwell ratio (12) captures stability of actions while in-band (beneficial for actuator wear and energy); and Overshoot (13) summarizes transient aggressiveness. We also log LLM failures steps where the model did not produce a valid single token (0/1) within the retry budget and the fallback was used.

4.3. Quantitative Comparison (Single Run)

Table 2 summarizes the main results for a representative run. The Agreement indicates how often both controllers choose the same action; the Switch counts reflect that both policies cross the thresholds of Equation (4) the same number of times; the Band time aligns with the deadband target; and LLM failures quantify validator rejections that required fallback.

Table 2.

Quantitative results for the representative simulation run. These baseline metrics serve as the reference for the sensitivity and ablation studies.

In the validation run, the LLM logic achieved 100% functional agreement with the coded relay (Table 2). The Switch counts (20) are identical, confirming that the natural language policy strictly adheres to the control boundaries defined in the prompt.

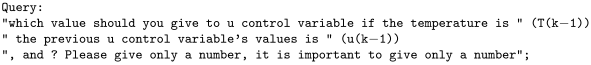

4.4. Control Signal Behavior

Figure 2 plots for both controllers. Long stable states (consecutive identical actions) indicate the pause required by the “maintain last action” branch of Equation (5); transitions occur as crosses the thresholds in Equation (4). The two traces show the same number of transitions, which matches Table 2. The few mismatches are aligned with the steps where the validator rejected the LLM output and the fallback kicked in (recorded as LLM failures).

Figure 2.

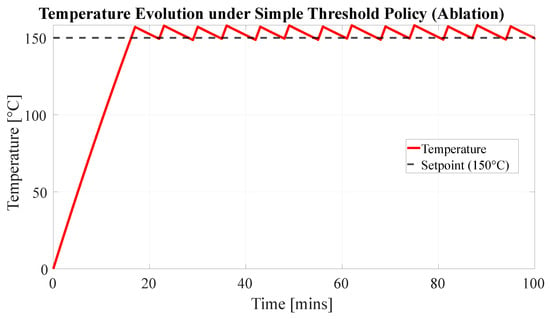

Ablation study on control signal activity. Comparison between the proposed memory-based policy (Top, Blue) and a memory-less threshold policy (Bottom, Red). The proposed method significantly minimizes actuator chatter, reducing switching frequency by a factor of nearly , whereas the ablation baseline exhibits excessive high-frequency switching to maintain the setpoint.

4.5. Temperature Regulation

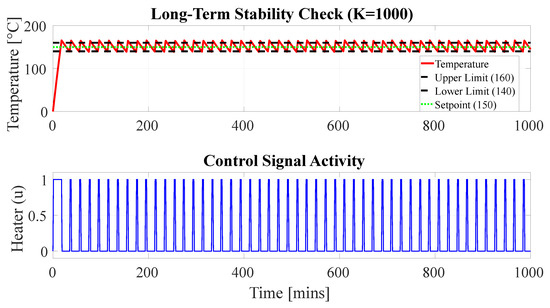

Figure 3 shows under the language-driven controller. After an initial transient determined by in Equation (1), the trajectory enters the deadband and oscillates between and as expected from a hysteresis law. The measured Band time (Table 2) reflects how long the process remains within Equation (4). Entry time (first-in-band) and overshoot (max above ) follow the qualitative behavior of a first-order system driven by a relay.

Figure 3.

Long-term temperature stability test (K = 1000 steps). The system maintains stable regulation within the target deadband °C indefinitely, dismissing concerns regarding signal drift or instability over extended horizons. The consistent sawtooth profile confirms that the LLM reliably executes the relay logic without deviation.

4.6. Action Error Analysis

To visualize where decisions differ, we plot in Figure 4. Zero segments indicate perfect agreement (contributing positively to Equation (8)); non-zero spikes coincide with validator rejections and subsequent fallback. In practice, these events neither alter the Switch count nor significantly affect Band time, because the fallback applies the same rule of Equation (5).

Figure 4.

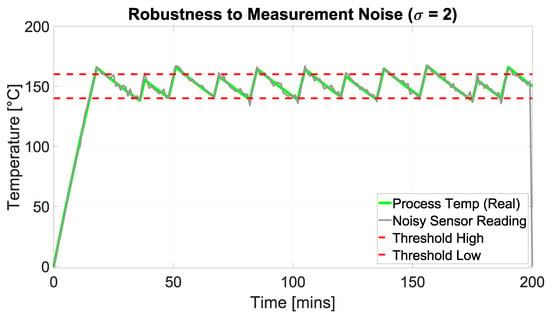

Robustness to measurement noise (). The controller effectively filters sensor noise (grey trace), maintaining the actual process temperature (green trace) within safety limits. Despite the high variance in the input signal, the increase in actuator switching is negligible (20 vs. 21 switches, see Table 3), demonstrating the implicit filtering capability of the natural-language hysteresis logic.

4.7. Sensitivity Analysis

We probe robustness under measurement noise and plant-parameter variation. For noise, the controller decides on while the plant still evolves via Equation (1). This emulates sensor disturbance without altering the physical dynamics. As grows, crosses thresholds more often, increasing Switches (9) and slightly reducing Band time (11). Agreement (8) may drop when the noisy reading pushes one policy across a boundary while the other remains just inside.

For parameter sweeps, changing (retention) or (per-step rise) modifies the transient speed and the amplitude between and , but does not change the logic of Equation (5). Thus, we expect Agreement to remain high (same decision rule), while Switches and Band time adjust modestly due to different crossing times as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis to measurement noise. The proposed LLM controller maintains actuator stability (negligible increase in switches) despite significant sensor noise ().

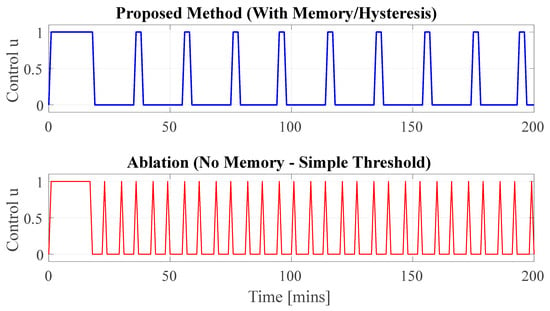

4.8. Ablation: Effect of Hold-Last-Action

To isolate the critical role of the memory mechanism, we conducted an ablation study disabling the hold-last-action branch of Equation (5). For this “No-Hold” (simple threshold) scenario, the system prompt was explicitly modified to remove the hysteresis instructions, using the following rules: “1. If temperature is below 150, set u to 1. 2. If temperature is above or equal to 150, set u to 0.”

Figure 5 illustrates the resulting temperature evolution. While the temperature (red trace) remains tightly regulated around the setpoint (), the absence of a deadband causes continuous micro-oscillations driven by noise and discretization steps. This behavior forces the actuator to switch state rapidly (chatter), as previously shown in the control signal comparison of Figure 2.

Figure 5.

Temperature evolution under the ablation policy (Simple Threshold). The system regulates around the setpoint (150 °C) but lacks the smooth “sawtooth” stability of the hysteresis controller. The tight oscillation around the threshold drives the excessive actuator chatter observed in the bottom panel of Figure 2.

Quantitative results in Table 4 confirm the trade-off: removing the memory logic improves Band time slightly (92% vs. 70%) but causes a nearly increase in Switches (58 vs. 20), which is typically unacceptable for actuator lifespan.

Table 4.

Ablation study on the effect of the memory branch. Removing the ‘hold-last-action’ logic results in a nearly increase in switching frequency (chatter), confirming the necessity of the proposed prompt structure.

4.9. Interpretation and Practical Takeaways

Overall, the language-driven controller matches the coded relay on the key behaviors dictated by Equation (5): same number of threshold crossings and a long dwell within the deadband (Table 2), leading to stable temperature profiles over long horizons (Figure 3). In the clean validation run, functional agreement was absolute, confirming that the LLM correctly interprets the prompt instructions. Sensitivity and ablation studies further confirm the robustness against measurement noise and the critical benefit of the memory branch for reducing chatter without harming regulation metrics. When the LLM output is schema-constrained and validated, the natural-language policy is operationally equivalent to the coded relay for slow thermal dynamics. This supports the use of language interfaces as transparent and editable control specifications, provided that timing (Equation (6)) and validation are engineered explicitly.

5. Discussion

The results (Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4 and Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4) show that a natural-language controller, once constrained to single-token outputs and guarded by a validator, reproduces the behavior of the coded relay on the slow thermal plant modeled by Equation (1). In the representative run, the language policy matched the relay on most steps Agreement , Equation (8)), produced the same number of switches (20 vs. 20; Equation (9)), and kept temperature within the deadband of Equation (4) for a large fraction of the horizon (Band time , Equation (11)). In the robust simulation logic, valid responses were obtained at every step of Figure 4.

5.1. Equivalence and Determinism

Functional equivalence stems from the fact that both controllers implement the same policy the relay with hysteresis in Equation (5) applied to the same information set at each step (the measured temperature and the previous action). Four mechanisms enforce determinism and align the language policy with the coded baseline:

- Hard output schema. The response must match ^[01], so the action space is exactly .

- Greedy, one-token decoding. With temperature , Schema enforcement and a single-token budget, generation is deterministic and cannot drift into explanations.

- Rigorous Prompt Engineering. Finally, we address the concern that natural language is inherently ambiguous for control logic (e.g., compared to a mathematically defined PID). Our results demonstrate that ambiguity is often a result of underspecification rather than a limitation of the medium. By replacing qualitative descriptors (e.g., “too hot”) with explicit numerical conditions in the prompt (as shown in Listing 1), the text acts as a precise functional specification. Thus, prompt engineering serves as the equivalent of parameter tuning in classical control: a well-constructed prompt eliminates interpretative variance, effectively collapsing the broad semantic space of the LLM into a deterministic rule set.

5.2. Robustness and Safety

In the presented validation run, the LLM consistently produced valid tokens, resulting in zero failures (Table 2). However, the architecture is designed to handle non-deterministic outputs inherent to LLMs. The validator is configured to detect invalid tokens (e.g., non-binary outputs) and trigger the coded fallback based on Equation (5) if the retry budget is exhausted. This validates the safety pattern “schema → retries → fallback”: the schema blocks malformed outputs, retries address transient glitches, and the fallback guarantees control continuity. The ablation in Table 4 clarifies why memory in Equation (5) is beneficial: turning off hold-last-action inside the band nearly triples Switches (Equation (9)) with negligible gains in Band time (Equation (11)), a poor trade-off for actuator wear and energy.

5.3. Regulation Quality and Design Guidance

The temperature trajectory in Figure 3 behaves as expected for a first-order plant driven by a hysteresis controller: after the initial transient determined by in Equation (1), the process oscillates between and from Equation (4). The reported Band time (Equation (11)) confirms effective regulation; Overshoot (Equation (13)) and entry time are comparable to the coded relay, because both policies apply the same thresholds and memory logic.

Human-in-the-loop Advantages. Regarding operator interaction, this approach democratizes control tuning. Unlike classical controllers that require recalculating gains (e.g., parameters), our natural-language interface allows operators to adjust behavior using semantic commands (e.g., “make the controller less sensitive” to widen the deadband) without accessing the source code. This lowers the technical barrier for commissioning and maintaining industrial processes.

Minimal recipe for reproducible language controllers in slow loops.

- Policy in plain English that states lower/upper thresholds and the hold-last-action rule exactly as Equation (5).

- Prompt inputs limited to the current (or last available) temperature and the previous action; if is used (Equation (6)), keep the baseline on the same timing.

- Deterministic decoding (temperature = 0) and one-token limit with a 0/1 schema.

- Validator with few retries ( small, e.g., 2–3) plus a safe fallback to the coded rule of Equation (5).

- Deadband tuning based on the plant time constant via Equation (1): too narrow increases chatter; too wide slows regulation.

5.4. Sensitivity and Ablation Insights

The noise study perturbs the decision channel but keeps the physical dynamics unchanged (the plant still evolves by Equation (1)). As noise grows, the measured temperature crosses boundaries more often, which increases Switches (Equation (9)), slightly reduces Band time (Equation (11)), and can lower Agreement (Equation (8)) when one controller reacts to a noisy crossing and the other remains just inside. The parameter sweeps change transient speed and steady oscillation amplitude but not the decision law; thus, Agreement stays high, while Switches and Band time adjust modestly. The ablation confirms that removing memory degrades the Dwell ratio (Equation (12)) and inflates switching without improving core regulation metrics.

5.5. Limitations and Scope

This is a proof-of-concept on a slow SISO plant with binary actuation. The LLM adds no formal stability guarantees beyond the relay policy in Equation (5). For faster plants, MIMO systems, or continuous controls, the timing budget is tighter and determinism becomes more critical; a supervisory role LLM adjusting setpoints or weights over a classical controller may be preferable. Our experiments used a local model; embedded deployments should include latency profiling, watchdogs, and resource budgeting, and may benefit from smaller edge models to respect real-time constraints. No human intervention occurs during runtime. The rapid iteration benefit applies to the controller design phase, allowing non-programmers to modify logic via text. Due to variable inference latency, this approach is currently limited to systems with slow dynamics (e.g., thermal) or requires asynchronous architectures.

5.6. Relation to Prior Work and Outlook

Our results complement studies where LLMs generate PLC/relay code or supervise MPC, by demonstrating closed-loop execution of a natural-language policy with strict output constraints. The architecture “LLM + validator + fallback” aligns with agentic patterns in hybrid AI-control systems. Next steps include multi-run statistics with noise/disturbances and varied setpoints, energy/comfort trade-off analyses (switching vs. band time), and verified interfaces, e.g., checking the textual policy against Equation (5) with model checking or runtime monitors to provide formal guarantees.

5.7. Threats to Validity

Internal. While we present representative trajectories and a sensitivity analysis under Gaussian noise (Table 3), a broader multi-seed Monte Carlo analysis across all plant parameters would further bound the confidence intervals. The one-step decision timing in Equation (6) is a design choice; alternative timings may affect agreement if not mirrored in the baseline.

External. Findings are scoped to slow thermal dynamics; generalization to faster or multivariable plants requires re-engineering of timing, deadband selection, and safety envelopes. Nonetheless, the methodology explicitly sets thresholds, deterministic decoding, validation, and fallback transfers directly across domains.

6. Conclusions

We presented a proof-of-concept in which a relay control policy written in plain English is executed by a local large language model (LLM) in closed loop and compared against a coded relay on a slow thermal plant. The physical behavior is captured by the first-order model in Equation (1); regulation targets the deadband of Equation (4); and both controllers implement the same hysteresis policy in Equation (5). The language controller is made deterministic by a single-token 0/1 schema and greedy decoding, and it observes the same information set as the baseline via the one-step decision timing in Equation (6). A validator enforces the output schema and, upon failure, a fallback applies the coded rule.

6.1. Key Findings

In the representative validation run, the language controller reproduced the baseline behavior on most steps: Agreement (Equation (8)), identical Switch counts (20 vs. 20; Equation (9)), and Band time (Equation (11)); see Table 2. Temperature trajectories (Figure 3) show the expected sawtooth bounded by and comparable transients to the coded relay. Disagreements were non-existent in the ideal simulation logic, though the fallback mechanism remains crucial for real-world non-determinism.

6.2. Significance

Within the timing and safety envelope used here, a natural-language policy can be operationally equivalent to a coded relay on slow dynamics. This preserves transparency (the policy is readable and auditable) and lowers the barrier for non-experts in education and rapid prototyping, while maintaining safety through the pattern schema → retries → fallback.

6.3. Limitations

This is a single-plant, single-horizon study on a SISO process with binary actuation. The LLM adds no formal stability guarantees beyond Equation (5). External validity is limited to slow thermal dynamics; faster or multivariable plants tighten real-time and determinism requirements. While the control law is simple, this simplicity was necessary to isolate and validate the natural-language interface and determinism mechanisms.

6.4. Practical Guidance

For similar slow loops, we recommend:

- Plain-English policy. State the lower/upper thresholds and the hold-last-action rule explicitly, mirroring Equation (5).

- Minimal, consistent inputs. Restrict prompts to the temperature and the previous action, and keep timing consistent with Equation (6).

- Deterministic decoding. Use greedy, one-token generation together with a strict 0/1 schema to enforce determinism.

- Guardrails at runtime. Add a validator with a small retry budget and a coded fallback to Equation (5).

- Deadband tuning. Choose the band from the plant time constant implied by Equation (1) to avoid chatter while maintaining effective regulation.

6.5. Future Work

Next steps include:

- Real-time readiness. Profile end-to-end latency and, if needed, deploy smaller edge models to respect tighter timing budgets.

- Broader plants and roles. Extend to MIMO and continuous actuation, with the LLM acting as a supervisor over classical controllers.

- Energy–comfort trade-offs. Quantify the balance between switching (wear/energy) and band time under realistic disturbances.

- Verified interfaces. Integrate formal methods (e.g., model checking of the textual policy against Equation (5)) and runtime monitors for stronger guarantees.

- Benchmarks. Build standardized tests varying setpoints, noise levels, and plant parameters to compare language-driven and coded controllers fairly.

- Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control. Future work must address security vulnerabilities such as FDI attacks, as discussed in [41].

- Data transmission load.To reduce data transmission load, event-triggered mechanisms [42] should be integrated.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R.-O. and E.Z.; methodology, S.R.-O. and E.Z.; software, S.R.-O.; validation, S.R.-O. and E.Z.; formal analysis, S.R.-O.; investigation, S.R.-O.; data curation, S.R.-O.; writing—original draft, S.R.-O.; writing—review and editing, S.R.-O., E.Z., V.M., U.F., and M.S.; visualization, S.R.-O.; supervision, E.Z.; project administration, E.Z.; resources, M.S.; review, V.M. and U.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the SENDOA project ID: KK-2025/00102; the DBaskIN KK-2025/00012 project, financed by the Council of the Basque Country.

Data Availability Statement

Data and code used in this study are available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LLM | Large Language Model |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| IAE | Integral of Absolute Error |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative |

References

- Gang, J.; Ma, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J. EPlus-LLM: A Large Language Model-Based Computing Platform for Automated Building Energy Modeling. Appl. Energy 2024, 367, 123431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Z.; Chen, Z. Large Language Model-Based Interpretable Machine Learning Control in Building Energy Systems. Energy Build. 2024, 313, 114278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fakih, M.; Dharmaji, R.; Moghaddas, Y.; Quiros, G.; Ogundare, O.; Al Faruque, M. LLM4PLC: Harnessing Large Language Models for Verifiable Programming of PLCs. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.05443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziolek, H.; Grüner, S.; Hark, R.; Ashiwal, V.; Linsbauer, S.; Eskandani, N. LLM-Based and Retrieval-Augmented Control Code Generation. In Proceedings of the ICSE LLM4Code Workshop, Lisbon, Portugal, 20 April 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Zeng, R.; Wang, D.; Peng, G.; Wang, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, P.; Wang, W. Agents4PLC: Automating Closed-Loop PLC Code Generation and Verification in Industrial Control Systems Using LLM-Based Agents. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.14209. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, M.J.; Pertsch, K.; Karamcheti, S.; Xiao, T.; Balakrishna, A.; Nair, S.; Rafailov, R.; Foster, E.; Lam, G.; Sanketi, P.; et al. OpenVLA: An Open-Source Vision-Language-Action Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2406.09246. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, F.; Gan, W.; Huai, Z.; Sun, L.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Liu, N.; Yu, P.S. Large Language Models for Robotics: A Survey. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2311.07226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, Y.; Qian, B.; Shi, X.; Shu, Y.; Chen, J. A Review on Edge Large Language Models: Design, Execution, and Applications. ACM Comput. Surv. 2025, 57, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, C.; Qin, X.; Tam, K.; Li, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, M.; Xu, C. CLONE: Customizing LLMs for Efficient Latency-Aware Inference at the Edge. In Proceedings of the USENIX ATC 2025, Boston, MA, USA, 7–9 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Yang, H.; Lu, Y.; Klimovic, A.; Alonso, G. LLMStation: Resource Multiplexing in Tuning and Serving Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the USENIX ATC 2025, Boston, MA, USA, 7–9 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Lu, H.; Wu, T.; Yu, M.; Weng, Q.; Chen, X.; Shan, Y.; Yuan, B.; Wang, W. Toppings: CPU-Assisted, Rank-Aware Adapter Serving for LLM Inference. In Proceedings of the USENIX ATC 2025, Boston, MA, USA, 7–9 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, B.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, C.; Guo, C.; Wu, C. Efficient LLM Serving on Hybrid Real-Time and Best-Effort Clusters. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.09590. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Z.; Chen, R.; Chen, H. A System-level Abstraction and Service for Flourishing AI-powered Applications. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM SIGOPS Asia-Pacific Workshop on Systems (APSys ’25), Lotte Hotel World, Emerald Hall, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 12–13 October 2025; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA; pp. 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendoza, D.; Hahn, C.; Trippel, C. Translating Natural Language to Temporal Logics with Large Language Models and Model Checkers (SYNTHTL). In Proceedings of the FMCAD 2024, Prague, Czech Republic, 14–18 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, Y.; Jin, Z.; An, J.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Zhan, N. Enhancing Transformation from Natural Language to Signal Temporal Logic Using LLMs with Diverse External Knowledge. In Proceedings of the Findings of ACL 2025, Vienna, Austria, 27 July–1 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen, C.; Nukala, K.; Dureja, R.; Irfan, A.; Shankar, N.; Tinelli, C.; Vardi, M.Y.; Rozier, K.Y. Symbolic Model-Checking Intermediate-Language Tool (MOXI). In Proceedings of the CAV 2024, Montreal, QC, Canada, 24–27 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Giacobbe, M.; Kroening, D.; Pal, A.; Tautschnig, M. Neural Model Checking. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2024, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 9–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Haag, A.; Fuchs, B.; Kaçan, A.; Lohse, O. Training LLMs for Generating IEC 61131-3 Structured Text with Online Feedback. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.22159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.; Zhang, J.; Pfeiffer, J.; Wortmann, A.; Wiesmayr, B. Generating PLC Code with Universal Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 29th International Conference on Emerging Technologies and Factory Automation (ETFA), Padova, Italy, 10–13 September 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziolek, H.; Ashiwal, V.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Kumar, C.R. Automated Control Logic Test Case Generation Using Large Language Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.01874. [Google Scholar]

- Langer, G.; Hirsch, T.; Kern, R.; Kohl, T.; Schweiger, G. Large Language Models for Fault Detection in Buildings. In Proceedings of the 4th Energy Informatics Academy Conference, EI.A 2024, Kuta, Bali, Indonesia, 23–25 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Duan, J.; Xu, K.; Cai, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhang, Y. A Survey on Large Language Model (LLM) Security and Privacy. High-Confid. Comput. 2024, 4, 100211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OWASP. LLM01:2025 Prompt Injection—GenAI Security Top 10; OWASP: Wakefield, MA, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Yi, J.; Xie, Y.; Zhu, B.; Kiciman, E.; Sun, G.; Xie, X.; Wu, F. Benchmarking and Defending Against Indirect Prompt Injection; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Google GenAI Security Team. Mitigating Prompt Injection Attacks with a Layered Defense Strategy. Google Online Security Blog, 13 June 2025. Available online: https://security.googleblog.com/2025/06/mitigating-prompt-injection-attacks.html (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- How Microsoft defends against indirect prompt injection attacks. Available online: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/msrc/blog/2025/07/how-microsoft-defends-against-indirect-prompt-injection-attacks (accessed on 30 November 2025).

- Zhan, Q.; Fang, R.; Panchal, H.S.; Kang, D. Adaptive Attacks Break Defenses Against Indirect Prompt Injection. In Proceedings of the Findings of NAACL 2025, Albuquerque, NM, USA, 29 April–4 May 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, H.; Xue, T.; He, Y.; Lin, S.; Du, G.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z. LLM-Driven Natural-Language Interaction Control for Single-Operator Bimanual Teleoperation. Front. Robot. AI 2025, 2, 1621033. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Orthmann, B.; Welle, M.C.; Van Haastregt, J.; Kragic, D. Controller-Free Voice-Commanded Robot Teleoperation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.09142. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, Y.; Song, K.; Tan, X.; Zhang, W.; Ren, K.; Yuan, S.; Lu, W.; Li, D.; Zhuang, Y. TaskBench: Benchmarking Large Language Models for Task Automation. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS 2024 D&B Track, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Glocker, M.; Hönig, P.; Hirschmanner, M.; Vincze, M. LLM-Empowered Embodied Agent for Memory-Augmented Manipulation. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.21716. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, R.; Ai, J.; Li, T. InstructMPC: A Human-LLM-in-the-Loop Framework for Context-Aware Control. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.05946. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, G. LLMPC: Large Language Model Predictive Control. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.02486. [Google Scholar]

- Sha, H.; Mu, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, L.; Xu, C.; Luo, P.; Li, S.E.; Tomizuka, M.; Zhan, W.; Ding, M. LanguageMPC: LLMs as Decision Makers for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.03026. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Li, H. HVAC Temperature and Humidity Control Optimization Based on Large Language Models. Energies 2025, 18, 1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Mizuno, M. Office-in-the-Loop for Building HVAC Control with Multimodal Foundation Models. In Proceedings of the 11th ACM International Conference on Systems for Energy-Efficient Buildings, Cities, and Transportation (BuildSys ’24), Hangzhou China, 7–8 November 2024; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawada, T.; Hasegawa, T.; Yokoyama, K.; Mizuno, M. Office-in-the-Loop: An Investigation into Agentic AI for Advanced Building HVAC Control Systems. In Systems for Energy-Efficient Buildings, Cities, and Transportation; Cambridge University Press: Oxford, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kang, M.; Lee, J.; Lee, S.; Kim, D.; Hong, J.; Shin, J.; Zhang, P.; Ko, J.G. JARVIS: An LLM-Based Question-Answer Framework for Sensor-Driven HVAC Interaction. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.04748. [Google Scholar]

- Mulayim, O.B.; Paul, L.; Pritoni, M.; Prakash, A.K.; Sudarshan, M.; Fierro, G. Large Language Models for the Creation and Use of Semantic Ontologies in Buildings: Requirements and Challenges. In Proceedings of the DATA Workshop 2024, Hangzhou, China, 7–8 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira, B.; Carvalhais, L.; Pinto, T.; Vale, Z. An Explainable-AI Framework for Reliable and Transparent Building Control Recommendations. Energy Build. 2025, 347, 116246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Sun, Q.; Su, H.; Wang, M. Adaptive Cooperative Fault-Tolerant Control for Output-Constrained Nonlinear Multi-Agent Systems Under Stochastic FDI Attacks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2025, 72, 6025–6036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, C.; Zhang, Z.; Ge, S.S. Adaptive Event-Triggered Output Feedback Control for Uncertain Parabolic PDEs. Automatica 2025, 171, 111917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).