Abstract

This study integrates microthermometry and laser-Raman spectroscopy of individual fluid inclusions with basin modelling to reconstruct the hydrocarbon-fluid evolution and multistage re-mobilisation of the Permian Longtan Formation transitional marine–terrestrial shale in the YJ-LJ area, southern Sichuan Basin. Systematic analysis of aqueous two-phase, methane-rich, and associated bitumen inclusions hosted in fracture-fill veins and sandy partings identifies four fluid episodes, enabling subdivision of petroleum evolution into five stages. Results show trapping pressure increasing with temperature to a maximum of 107.77 MPa, equivalent vitrinite reflectance (EqVR) between 1.49% and 2.49%, and formation-water salinity that first rises then falls, remaining within the high-salinity continental-leaching brine field. Coupled with thermal-history modelling, shale-oil/gas evolution is divided into: (1) low-pressure slow burial, (2) over-pressured rapid burial, (3) sustained over-pressured deep burial, (4) high-pressure uplift adjustment, and (5) late uplift adjustment. The study demonstrates that over-pressure has been partially preserved, providing critical palaeo-fluid and pressure evidence for exploring transitional marine-terrestrial shale gas.

1. Introduction

Fluid inclusions are micron-scale domains of ancient fluid that were trapped in structural defects or growth cavities of host minerals during crystallisation. They preserve critical palaeo-fluid information such as temperature, pressure and composition at the time of entrapment [1,2]. Investigation of fluid inclusions is therefore a direct and robust approach [3,4] and has been widely applied in conventional hydrocarbon-accumulation studies [5,6,7]. In unconventional reservoirs, however, the fine-grained size and low crystallinity of shale mean that usable inclusions seldom form during palaeo-fluid flow [8]. Fortunately, mineralised veins that fill shale fractures and sandy partings within mudstone commonly contain abundant workable inclusions and can provide key evidence for shale-gas-reservoir evaluation [9,10].

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful tool for fluid-inclusion analysis [11,12,13]. Because the laser beam can be focused to <3 µm, both entire inclusions and individual phases within them can be interrogated in situ [14]. The recent development of sealed capillary standards with fixed compositions [15,16,17] is driving the technique from qualitative toward semi-quantitative or even quantitative analysis, enabling rapid quantification of organic-matter maturity, trapping pressure and fluid density [18,19] that can be applied directly to shale-gas exploration.

In the southern Sichuan Basin, intensive shale-gas drilling has prompted inclusion-based investigations of fracture-filling veins in the Silurian Longmaxi marine shales, revealing palaeo-pressure and accumulation histories [3,20,21,22]. By contrast, the Permian Longtan Formation (LTF)—a marine–terrestrial transitional mudstone succession in the same region—has received little attention. Expanding research on the LTF within the region will significantly benefit the exploration of unconventional hydrocarbon resources in new frontiers of China.

Here, we collected vein material from black LTF shales and sandy interbeds from the YJ-LJ area, southern Sichuan Basin, and prepared doubly polished thin sections. Individual two-phase (aqueous vapour–liquid) brine inclusions and associated solid-bitumen inclusions were subjected to non-destructive petrography, microthermometry and laser-Raman spectroscopy. Trapping pressures, thermal maturity and formation-water compositions were reconstructed to unravel the hydrocarbon-fluid evolution of the LTF and to discuss its geological implications.

2. Geological Setting and Samples

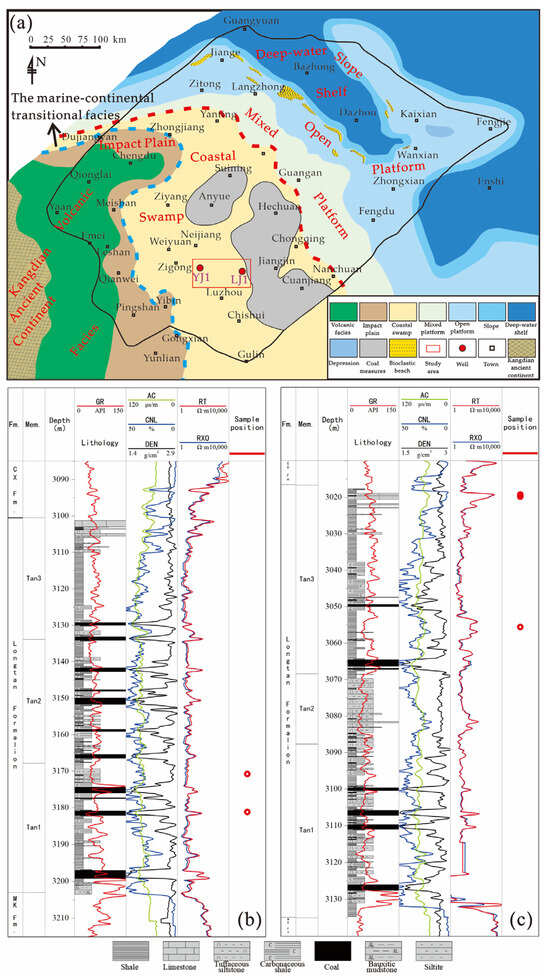

The Sichuan Basin, situated in the western part of the Yangtze Platform, is one of China’s most important petroliferous basins. Within it, the Permian Longtan Formation (LTF), deposited in a marine–terrestrial transitional setting, has emerged as a new ‘hot spot’ for shale-gas exploration and development [23,24,25]. The Middle–Late Permian Dongwu orogeny was accompanied by large-scale volcanism in the southwestern basin—the Emeishan basalt eruptions—linked to the ascent of a mantle plume and constituting a major large igneous province [26,27]. Consequently, the Late Permian Sichuan Basin shows pronounced sedimentary differentiation: from the southwestern margin landward, successively, continental, transitional and marine environments are recognised [28,29,30] (Figure 1a). Longtan Formation strata are best preserved in the central and eastern basin. They were laid down in transitional coastal-plain to lagoonal settings and consist dominantly of fine-grained rocks—mudstone, shale, siltstone, and coal seams—intercalated with thin limestones and siltstone lenses [31,32,33,34] (Figure 1b,c). Rapid alternation of multiple lithologies produces an overall coal.

Figure 1.

(a) Palaeogeographic map of the Longtan Formation in the Sichuan Basin showing the locations of the sampled wells (modified from Ref. [30]); (b) composite stratigraphic column of well LJ-1 with sampling depths; (c) composite stratigraphic column of well YJ-1 with sampling depths.

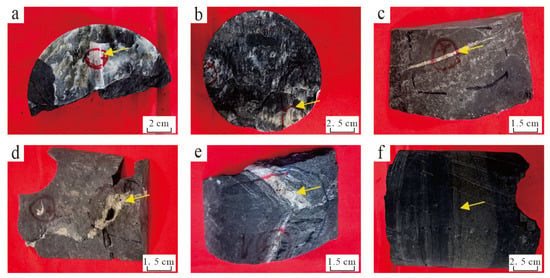

Given the absence of a fully cored well through the Longtan Formation across the basin, six samples were selected from the LTZ in two key wells in the YJ-LJ area of southern Sichuan Basin: YJ-1 (coring the upper-middle LTZ) and LJ1 (coring the lower-middle LTZ), together providing good coverage of the formation. The suite comprises two vein samples from LJ-1 (Figure 2a,b), three vein samples from YJ-1 (Figure 2c–e) and one sandy parting sample extracted from mudstone in YJ-1 (Figure 2f). Owing to discontinuous coring, samples from well LJ-1 are concentrated in the Tan1 member, whereas those from well YJ-1 are mainly from the Tan3 member. Given the essentially uniform sedimentary and structural setting, we infer that the fluid-inclusion assemblages are comparable between the two intervals. Consequently, all samples were sealed immediately after retrieval and transported promptly to the laboratory for thin-section preparation and subsequent analyses.

Figure 2.

This is a figure. Schemes follow the same formatting. Sample photographs and locations of thin-section preparation. (a) Well LJ-1, 3170.75 m, Quartz vein; (b) Well LJ-1, 3181.18 m, Quartz vein; (c) Well YJ-1, 3019.82 m, Quartz vein; (d) Well YJ-1, 3019.60 m, Quartz vein; (e) Well YJ-1, 3019.27 m, Calcite vein; (f) Well YJ-1, 3055.59 m.

3. Experiment

3.1. Preparation of Double-Polished Wafers

Three preparation techniques exist for fluid-inclusion analysis: cleavage chips obtained by splitting along mineral parting planes with a razor blade, quick mounts—ground but unpolished wafers whose surface relief is locally flattened with immersion oil matched to the host-mineral refractive index—and double-polished wafers. For this work, we selected double-polished wafers prepared in five sequential steps after McNeil and Morris [35] (1992): impregnation, sectioning, grinding, polishing, and mounting.

3.2. Microthermometry

A UK-manufactured Linkam THMSG600 (Linkam Scientific Instruments Ltd., Tadworth, UK) heating–freezing stage was used to determine homogenisation (Th) and final ice-melting (Tm) temperatures with an uncertainty of ±0.1 °C. During Th acquisition, samples were first heated at 5–10 °C min−1; once the vapour bubble began to shrink rapidly the rate was reduced to 0.5 °C min−1, the temperature of complete homogenisation was logged, heating was continued 5–10 °C beyond this point to check for phase changes, the section was then cooled until the bubble reappeared and the cycle was repeated to verify reproducibility. For two-phase aqueous inclusions, cooling was initiated at 15–20 °C min−1 to nucleate ice; warming was then performed at 1 °C min−1 to −10 °C and finally at 0.5 °C min−1, with the last-melting ice-crystal temperature recorded as Tm. Methane-rich inclusions were quenched with liquid nitrogen to the phase-transition point, cooled further to monitor bubble behaviour, and subsequently warmed at 2 °C min−1 until homogenisation was achieved; the corresponding Tₕ(CH4) was recorded. In this study, microthermometric measurements were performed on as many inclusions as possible, provided their size and morphology met the required criteria (typically >3 μm and regular shape).

3.3. Laser-Raman Spectroscopy

Methane-rich, aqueous two-phase and bitumen inclusions in the present samples were non-destructively characterised using a LabRAM HR800 Raman spectrometer (HORIBA Scientific, Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a 532 nm YAG solid-state laser; individual inclusions > 1 μm were targeted. Gas, liquid and solid phases were identified from their characteristic Raman shifts. v0 denotes the methane Raman peak position at near-zero pressure; for this study, the calibration performed in the laser-Raman laboratory gives v0 = 2917.52 cm−1.

4. Geological Applications and Results

4.1. Reconstructing Palaeo-Pressure During Geological Time

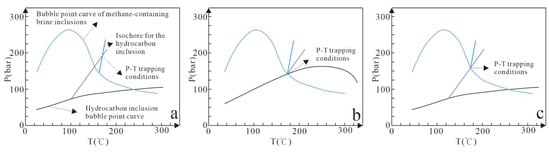

For fluid inclusions trapped in diagenetic minerals, coeval oil-bearing and aqueous inclusions share identical temperature and pressure conditions at the time of entrapment; consequently, the intersection of their respective isochores defines the trapping temperature (Tt) and trapping pressure (Pt) [36,37]. Pironon [38] (2004) discriminated three inclusion scenarios in hydrocarbon-bearing environments: (i) both aqueous and petroleum phases are undersaturated in gas at entrapment—hence, Tt and Pt correspond to the intersection of the liquid-phase isochores, whereas the homogenisation temperature (Th) and homogenisation pressure (Ph) are lower than Tt and Pt (Figure 3a); (ii) both phases are gas-saturated, and the isochore intersection coincides with the bubble-point curve, hence Th and Ph are equal to Tt and Pt (Figure 3b); (iii) the aqueous phase is gas-saturated whereas the petroleum phase is gas-undersaturated—hence, the isochore intersection lies on the bubble-point curve of the aqueous inclusion only (Figure 3c). Petrographic inspection and geological context indicate that the studied assemblage corresponds predominantly to scenario (ii); accurate palaeo-pressure reconstruction therefore hinges on precise determination of Th and Ph [39].

Figure 3.

Isochore intersection diagrams for petroleum-bearing and aqueous fluid inclusions (modified after reference [38]). (a) Both aqueous and petroleum phases are gas-undersaturated at the time of entrapment. (b) Both aqueous and petroleum phases are gas-saturated at entrapment; (c) The aqueous phase is gas-saturated, whereas the petroleum phase remains gas-undersaturated at entrapment.

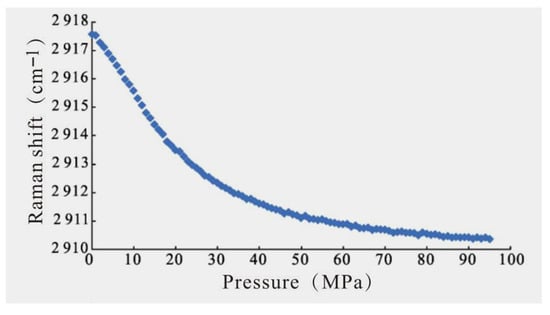

Accurate Th values were acquired via microthermometry on a heating–freezing stage, whereas Ph was derived by laser micro-Raman spectroscopy. Since Fabre et al. [40] first documented in 1979 that the C–H stretching band of gaseous CH4 shifts systematically with density or pressure, numerous subsequent studies have confirmed that the symmetric C–H stretching vibration moves to lower wavenumbers as density or pressure increases [16,41,42,43]. Xi et al. [44] (2020) constructed an experimental setup following the protocol of Chou et al. [17] (2008) and, using the calibration procedure of Qiu et al. [22] (2020), established a CH4 peak-position versus pressure calibration curve (Figure 4); a corresponding density relationship was not provided. Lu et al. [42] compiled multi-laboratory data to generate a universal Raman-shift versus pressure equation for methane (Equation (1)); although minor deviations occur at elevated pressures, their companion equation linking CH4 peak position to density (Equation (2)) has found wide application.

where νp–ν0 denotes the Raman shift difference between the measured CH4 peak position and that of nearly zero-density methane.

P(MPa) = −0.0148 × (νp − ν0)5 − 0.1791 × (νp − ν0)4 − 0.8479 × (νp − ν0)3 − 1.765(νp − ν0)2 × 5.876 × (νp − ν0)

ρ(g/cm3) = −5.17331 × 10−5(νp − ν0)3 + 5.53081 × 10−4(νp − ν0)2 − 3.51387 × 10−2(νp − ν0)

Figure 4.

Relationship between CH4 peak position and pressure (after [22]).

Fluid inclusions archive the temperature and pressure of the ambient fluid at the time of entrapment and thus constitute a robust tool for reconstructing palaeo-fluid P–T conditions. Previous studies have demonstrated that, within an immiscible fluid-inclusion assemblage, the lowest homogenisation temperature (Th) of the aqueous two-phase inclusions corresponds to the trapping temperature. The trapping pressure of the sample inclusions is calculated with the equation of state for super-critical methane systems developed by Duan [45,46] (1992a, 1992b) (Equations (3)–(12)). By coupling the derived methane-inclusion density range with the above equation, the trapping pressure of each inclusion was obtained.

In the equation, P is pressure (bar), T is temperature (K), R is the gas constant (0.08314467 bar·dm3·K−1·mol−1), V is the molar volume (dm3/mol) derived from the density (ρ) and molar mass of methane, and Z is the compressibility factor. Pr and Tr denote reduced pressure and reduced temperature, respectively, both dimensionless; Pc and Tc are the critical pressure (46 bar) and critical temperature (190.4 K), consistent in units with P and T. The coefficients are: a1 = 0.0872553928, a2 = −0.752599476, a3 = 0.375419887, a4 = 0.0107291342, a5 = 0.0054962636, a6 = −0.0184772802, a7 = 0.000318993183, a8 = 0.000211079375, a9 = 0.0000201682801, a10 = −0.0000165606189, a11 = 0.000119614546, a12 = −0.000108087289, α = 0.0448262295, β = 0.75397, γ = 0.077167.

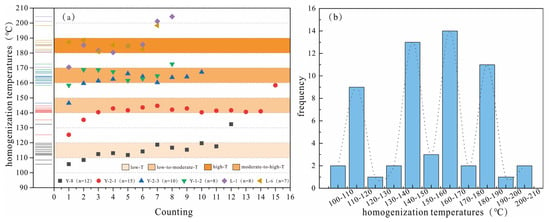

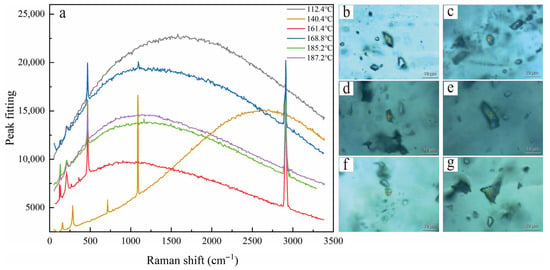

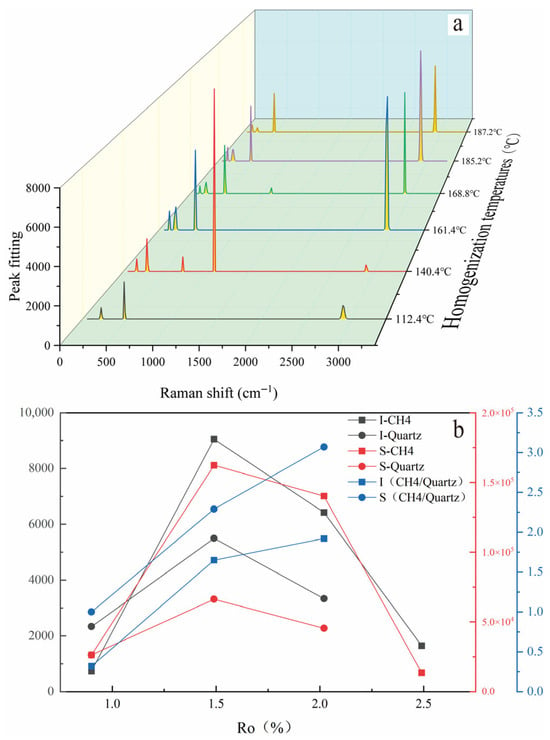

Microthermometric data for aqueous two-phase inclusions yield Th values between 112.4 and 201.2 °C (Figure 5a,b), clustering in four intervals at 110–120 °C, 140–150 °C, 160–170 °C and 180–190 °C. A limited number of outliers are attributed to metastable behaviour of the system [47] and are excluded from further discussion. Accordingly, the dataset was subdivided into four groups: low-T, low-to-moderate-T, moderate-to-high-T, and high-T. Contemporaneous methane-bearing inclusions from each group were selected for laser-Raman analysis (Figure 6b–g); inclusion IDs are listed in Table 1.

Figure 5.

Histogram of homogenisation temperatures (Th) for aqueous two-phase fluid inclusions. (a) Homogenised temperature distribution map; (b) Homogenised temperature-frequency distribution histogram.

Figure 6.

(a) Laser-Raman spectra of coeval methane-bearing inclusions associated with aqueous inclusions homogenised at different temperatures; (b) low-T group inclusion, Th = 112.4 °C; (c) low-to-moderate-T group inclusion, Th = 140.4 °C; (d) moderate-to-high-T group inclusion, Th = 161.4 °C; (e) moderate-to-high-T group inclusion, Th = 168.8 °C; (f) high-T group inclusion, Th = 185.3 °C; (g) high-T group inclusion, Th = 187.3 °C.

Table 1.

Summary of fluid-inclusion sample information.

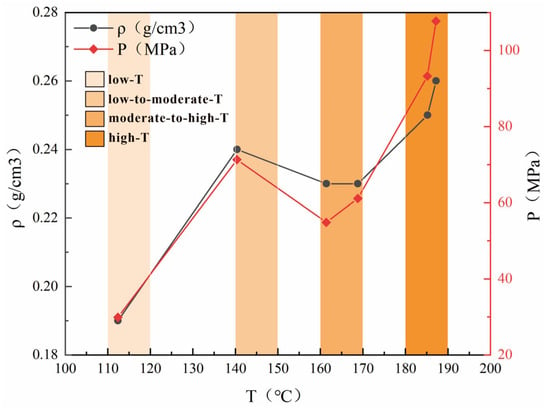

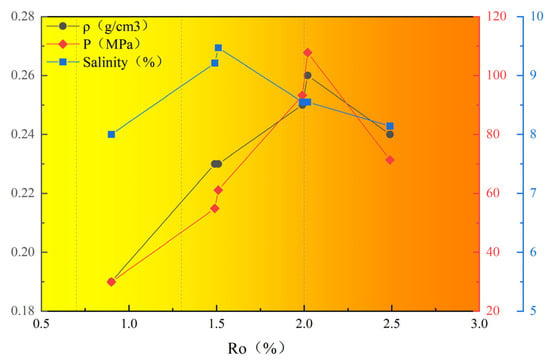

Laser-Raman spectra of methane inclusions coeval with aqueous two-phase inclusions (Figure 6a) display intense host-mineral bands together with CH4 peaks of variable relative intensity. Overall, trapping pressure increases with trapping temperature (Figure 7), ranging from 29.93 to 107.77 MPa, whereas inclusion densities cluster between 0.19 and 0.26 g/cm3. An anomalous data point (elevated density and pressure) occurs within the low-to-moderate-T group. Integrating the discussion in Section 4.2, this inclusion most likely formed during a late entrapment event.

Figure 7.

Relationship between methane-inclusion density/pressure and the homogenisation temperature (Th) of coeval aqueous two-phase inclusions.

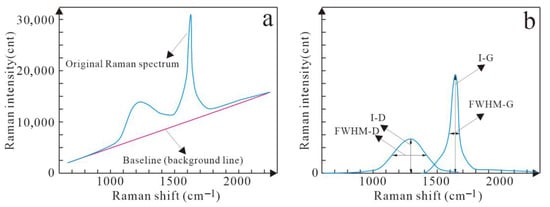

4.2. Determine the Maturity of Thermal Evolution

Within a single stratigraphic unit of comparable organic-matter abundance, the degree of thermal maturation dictates the maximum hydrocarbon yield. For assessing the maturity of palaeo-organic matter, the Raman Maturity Method (RaMM-Ro) is regarded as an accurate and rapid diagnostic tool [18,48]. Mixed or discrete Raman spectra of vitrinite and inertinite are acquired; multivariate linear regression of selected G- and D-band parameters [49] (Figure 8) yields the equivalent vitrinite reflectance (EqVR). A key advantage of RaMM is its applicability to dispersed organic matter where vitrinite is unidentifiable [50,51], making it well-suited to bitumen trapped within fluid inclusions. Using the maturity models of Lu et al. [52] or Wilkins et al. [53] (Equations (13)–(16)), Raman parameters of associated bitumen inclusions from each temperature group were processed to derive EqVR values.

Figure 8.

Relationship Schematic diagram illustrating Raman spectral parameters and curve-fitting principles for organic matter (summarised from references [54,55,56]). (a) Baseline not removed; (b) Remove the baseline.

νG–νD denotes the peak-to-peak separation (cm−1) between the G and D bands; b is the slope of the spectral baseline; Saddle index is the ratio of the G-band height to the saddle minimum between the overlapping G and D peaks; FWHM-G and FWHM-D are the full widths at half maximum of the G and D bands, respectively; I-G/I-D is the height ratio of the G to D band (Figure 8). For the protocol established by Wilkins et al. [53], a reliable EqVR calculation further requires simultaneous acquisition of the background baseline. Equation (3) is valid only for equivalent vitrinite reflectance (EqVR) between 0.4% and 1.0%, whereas Equation (4) applies exclusively to EqVR > 1.25%. When EqVR falls in the transitional window of 1.0–1.25%, both equations are solved, and the arithmetic mean of the two results is adopted.

RmcRo% = 0.0537 d(νG-νD) − 11.21

RmcRo% = 1.1659 (I-D/I-G) + 2.7588

EqVR% = −6.384 + 5.439 log(νG − νD) + 0.863 log(b) + 0.832 log(saddle index) − 2.677 log(FWHM-D)

− 0.661 log(FWHM-D)

− 0.661 log(FWHM-D)

EqVR% =−52.3363 + 13.1992 log(νG − νD) − 0.7964 log(b) + 8.1121 log(FWHM-D) + 15.3255 log(I-G/I-D)

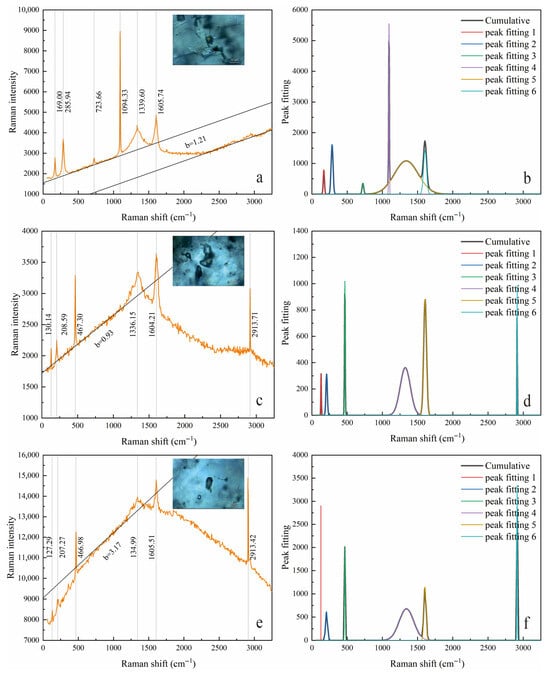

Throughout the burial history, formation temperature exhibits a quasi-quadratic relationship with time within a specific interval; consequently, maturity analysis was focused on the three inclusion generations (LJ1-6-L, YJ1-2-3-L and YJ1-2-4-L) entrapped during this thermally symmetric period. Considering the validity ranges of the respective maturity algorithms, Equations (13) and (16) were selected for the present study. When Equation (13) was applied, the G–D peak separations [νG – νD] of the analysed bitumen inclusions LJ1-6-L, YJ1-2-3-L and YJ1-2-4-L are 266.14 cm−1, 268.05 cm−1 and 263.52 cm−1, yielding RmcRo values of 3.08%, 3.18% and 2.94%, respectively. Application of Equation (16) required spectral deconvolution [57,58,59] (Figure 9) using Gaussian, Lorentzian and pseudo-Voigt functions [60] to extract the requisite parameters (Table 2). The resulting equivalent vitrinite reflectance (EqVR) values are 2.49% (Figure 9a,b), 1.49% (Figure 9c,d) and 2.01% (Figure 9e,f). With reference to Zhang et al. [61], who reported a maximum vitrinite reflectance (Romax) of 3.05% for the target succession, EqVR values derived from the Wilkins [53] model are considered more representative of the studied horizon. Consequently, the maturity sequence from lowest to highest is as follows: moderate-to-high-T group (1.49%), high-T group (2.01%), and low-to-moderate-T group (2.49%).

Figure 9.

Laser-Raman spectroscopic parameters and curve-fitting results of associated bitumen inclusions: (a) raw Raman spectrum of inclusion LJ1-6-L; (b) integrated-transform profile of inclusion LJ1-6-L; (c) raw Raman spectrum of inclusion YJ1-2-3-L; (d) integrated-transform profile of inclusion YJ1-2-3-L; (e) raw Raman spectrum of inclusion YJ1-2-4-L; (f) integrated-transform profile of inclusion YJ1-2-4-L.

Table 2.

Peak-by-peak integration parameters for each sample.

4.3. Analyse the Properties of Formation Water During the Burial Process

The liquid phase of aqueous two-phase inclusions also preserves abundant information that provides critical insights into the nature of pore fluids during burial diagenesis [62,63]. Hall et al. [64] derived a salinity calculation based on experimental data and Raoult’s law. Knight et al. [65] determined the critical properties of the NaCl–H2O system, thereby expanding the database for critical-condition calculations. Subsequent compilation by Bodnar [66] has made this approach the most widely used method for determining fluid-inclusion salinity (Equation (17)).

where Tf is the final ice-melting temperature.

Salinity(%) = 0.00 + 1.78Tf − 0.04421.78Tf2 + 0.000557Tf3

Based on Tf data obtained with a heating–freezing stage (Table 1), salinity values for each temperature group are displayed in Figure 10. Salinity first increases and then decreases with rising thermal maturity, the inflexion preceding the corresponding shift in trapping pressure and density. All values are high (salinity > 5 wt%) and exhibit a narrow total range. Burial depth is considerable (>3000 m), and the shale matrix has inherently low permeability; hence, external fluid ingress was minimal during progressive burial. It is therefore inferred that internally generated water during hydrocarbon generation and variable degrees of water–rock interaction were the primary controls on the salinity evolution of pore fluids. The slight decrease in salinity recorded during uplift is interpreted to reflect, at least in part, the influence of externally derived fluids [67].

Figure 10.

Variations in methane-inclusion density and trapping pressure, together with aqueous two-phase inclusion salinity, as a function of thermal maturity (EqVR).

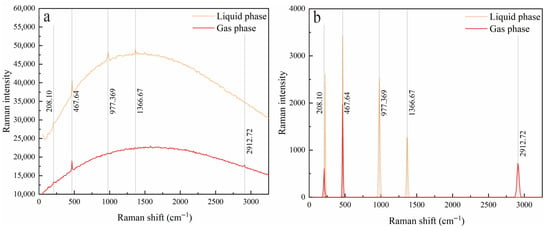

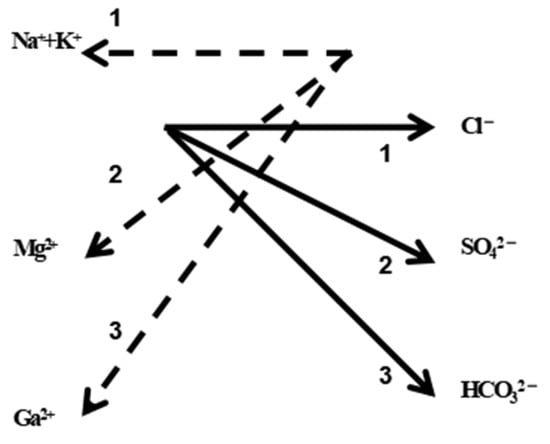

Leveraging the high spatial resolution of laser-Raman spectroscopy, the liquid phase of aqueous two-phase inclusion Y-8-D from the low-T group was analysed (Figure 11a). Host-mineral bands (quartz: 208.10 and 467.64 cm−1) are identical for coeval methane-bearing (vapour) and aqueous (liquid) inclusions, whereas the baseline is slightly displaced under the liquid-phase signal. Two prominent liquid-phase peaks occur at 977.369 and 1366.67 cm−1. Following the ion-specific band assignments of Rosasco [57], Burke [68] and Frezzotti [69], these features are assigned to SO42− and HCO3−, respectively. After integrated intensity transformation (Figure 11b), the SO42−/HCO3− ratio is ~2:1. Monatomic cations (Na+, K+, etc.) are Raman-inactive and could not be detected. Within the Late Permian depositional context [26], the palaeo-formation water was classified using the Sulin scheme [70]; charge-balance calculations (Figure 12) indicate a continental-leaching water type.

Figure 11.

(a) Raman spectrum of the low-T group inclusion Y-8-D(Gas phase, liquid phase); (b) integrated-transform spectrum showing the resolved peak positions of each component.

Figure 12.

Simplified sequence of ionic compounds used in the Sulin classification scheme (compiled after reference [70]).

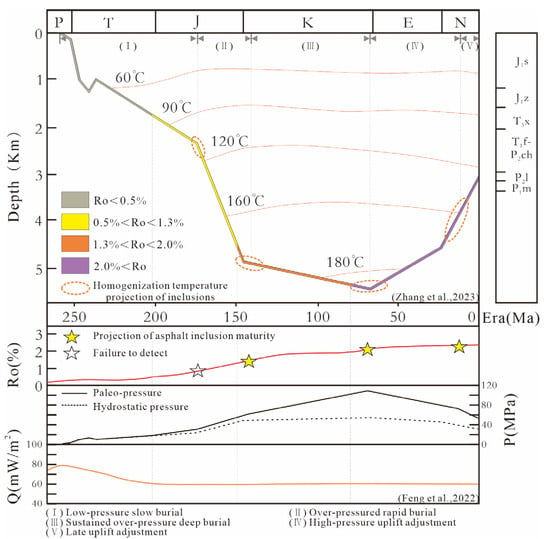

5. The Process of Reservoir Oil and Gas and Its Geological Significance

Integrating the above results, the formation and evolution of shale gas in the study area can be rigorously constrained. In the YJ block, uplift initiated at approximately 70 Ma during the Yanshanian–Himalayan transition [71]. Maximum palaeo-burial depth prior to exhumation reached 5.6–5.8 km [61], palaeo-temperatures were 180–210 °C, and Longtan Formation shale maturity (Ro) was 2.4–2.6% [28,72]. Under the constraints of regional thermal events, we referenced the thermal history of the adjacent YS2 well [73], and used the drilled lithology log and stratigraphic picks from well YJ-1 (whose lithological column is broadly similar to that reported in [28,31]) to simulate the burial–uplift thermal evolution of YJ-1 using BasinMod (Figure 13). Microthermometric and Raman data were superimposed on the modelled thermal curve, combined with Raman spectral deconvolution parameters (Figure 14). Peak height (I-CH4), peak area (S-CH4), height ratio (I-CH4/quartz) and area ratio (S-CH4/quartz) were employed to quantify the relative intensity of successive hydrocarbon-fluid re-mobilisation events. This approach enabled the identification of four distinct fluid episodes preserved within the inclusions and provided a framework for analysing the associated petroleum evolution history.

Figure 13.

Burial–uplift thermal history of well YJ-1 (burial history modified from [61]; heat-flow values from [73]).

Figure 14.

(a) Integrated-transform Raman spectra for each temperature group; (b) variation in Raman parameters with thermal maturity.

Fluid re-mobilisation documented by the low-T inclusion assemblage represents the earliest episode. Approximately 172–177 Ma ago, formation pressure was the lowest of the four stages, organic maturity was 0.90%, formation-water salinity was 8.0%, and the water is classified as a continental-leaching mixed brine; hydrocarbon-fluid re-mobilisation intensity was extremely weak. The moderate-to-high-T assemblage records the second, slightly younger episode. Around 140–146 Ma ago, formation pressure was still relatively low, organic maturity reached 1.49%, salinity rose to 9.3%, and Raman spectral deconvolution parameters consistently indicate a significant increase in hydrocarbon-fluid re-mobilisation intensity. The high-T assemblage represents the third episode, approximately 69 Ma ago, when formation pressure peaked, organic maturity was 2.01%, salinity remained at 8.6%, and this stage records the most intense hydrocarbon-fluid re-mobilisation event. The low-to-moderate-T assemblage records the latest pulse, approximately 69 Ma ago, characterised by the highest organic maturity (2.49%), lower formation-water salinity (8.1%), and a pronounced drop in trapping pressure. Hydrocarbon-fluid re-mobilisation intensity was weak, suggesting that the inclusion population captures the waning stage of this final episode.

Integrating the four chronological episodes recorded by fluid inclusions with thermal-history modelling, the petroleum evolution of the LTF can be subdivided into five stages.

Low-pressure slow burial (Ro < 0.9%): deposition duration was short, and burial was shallow; pore waters are high-salinity, continental-leaching mixed brines that established the baseline aquatic environment for subsequent hydrocarbon generation. Brief uplift related to the Indosinian orogeny had a negligible impact on thermal evolution; organic matter remained immature, early hydrocarbon generation was incipient, and formation pressure was hydrostatic. Consequently, hydrocarbon-fluid activity was extremely weak.

Over-pressured rapid burial (0.9% < Ro < 1.5%): accelerated subsidence driven by early Yanshanian tectonics. Increasing temperature with depth carried organic matter through the diagenetic window into the oil-generation zone. Hydrocarbon generation initiated secondary over-pressure and enhanced fluid mobility. Expulsion of connate water and variable water–rock reactions reduced pore volume, elevating brine salinity.

Sustained over-pressure deep burial (1.5% < Ro < 2.0%): LTZ approached maximum burial; maturity rose rapidly, the reservoir was charged with highly evolved, dry thermogenic gas and moderate-to-strong over-pressure. Hydrocarbon-fluid activity peaked, allowing fracture-hosted veins of the high-T episode to trap abundant dense methane and aqueous two-phase inclusions that archive palaeo-P–T conditions.

High-pressure uplift adjustment (2.0% < Ro < 2.5%): late Yanshanian and early Himalayan compression drove uplift; heating and pressurisation waned. Formation pressure remained strongly over-pressured. Internal fluid activity declined, probably in response to pressure release. Pressure decline reflects both unloading during uplift and lateral gas migration along fractures into adjacent strata.

Late uplift adjustment (Ro > 2.5%): accelerated exhumation under early Himalayan compression. Organic matter reached post-mature stage and hydrocarbon generation waned [74,75]; present-day over-pressure analyses indicate weak internal fluid activity, allowing partial preservation of original over-pressure in gas-charged intervals [76].

6. Limitations

This study demonstrates the first application of in situ, non-destructive laser-Raman analysis of individual fluid inclusions in the Longtan Formation transitional marine–terrestrial reservoir rocks, Sichuan Basin, and provides a robust constraint on the petroleum evolution history of the unit. By correlating micro-Raman spectral parameters (peak area, peak position, peak height and their ratios) with stratigraphic and geologic constraints, the composition and internal pressure of single fluid inclusions can be retrieved accurately and comprehensively. This approach overcomes the limitations of conventional quantitative techniques that are sensitive to thin-section thickness, experimental conditions, inclusion composition and host-mineral properties. Nevertheless, the burial-related evolution is simultaneously governed by multiple interactive factors; the analytical workflow presented herein—particularly regarding the characterisation of host minerals to fluid inclusions—remains to be refined as a consequence of current core-acquisition limitations. In addition, quantification in this work relied primarily on ratio-based calibrations; single-sample reference standards were not prepared. Future efforts should focus on coupling this technique with complementary instrumentation to advance towards high-precision, fully quantitative analysis.

7. Conclusions

Fluid inclusions are direct archives of palaeo-fluid physico-chemistry; non-destructive, in situ analysis of single inclusions has long been a focus of petroleum-geological research. Laser-Raman-based in situ non-destructive protocols applied to individual inclusions in reservoir rocks can decipher hydrocarbon evolution histories and are widely used to reconstruct palaeo-pressure, thermal maturity and burial-stage pore-water compositions.

Integrated laser-Raman investigations of fluid inclusions in the Longtan Formation reservoir reveal four distinct fluid-flow episodes. Early (low-T) and late (low-to-moderate-T) pulses were weak, whereas mid-early (moderate-to-high-T) and mid-late (high-T) events were intense. Inclusion-derived pressure, salinity and density all increase with thermal maturity to a maximum and then decline. These four temporal anchors are used to subdivide the petroleum evolution into five stages: low-pressure slow burial, over-pressured rapid burial, sustained over-pressured deep burial, high-pressure uplift adjustment, and late uplift adjustment. The resultant evolutionary trajectory indicates that over-pressure has been well preserved in parts of the studied gas accumulations.

Given four fluid pulses of contrasting intensity, five hydrocarbon-evolution stages and the interbedded lithologies of the Longtan Formation, the potential for fluid re-mobilisation to generate vertically continuous geologic sweet spots requires further investigation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, L.W.; methodology, L.W.; software, N.Q.; validation, Y.C. (Ya’na Chen) and W.Y.; formal analysis, Y.C. (Yuchuan Chen) and Y.Z. (Yaqi Zhao); investigation, L.W. and S.H.; resources, X.L.; data curation, L.W. and Y.Z. (Yuhang Zhou); writing—original draft preparation, L.W.; writing—review and editing, L.W.; visualisation, L.W. and J.X.; supervision, Y.C. (Ya’na Chen); project administration, X.L.; funding acquisition, X.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the “In-Depth Study on the Development Potential of the Permian Longtan Formation Coal-Shale System in the Sichuan Basin” (No. 2024-N/G-46602).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely thank the Sichuan Basin Research Centre of the Petroleum Exploration and Development Institute of China National Petroleum Corporation for their valuable support and guidance during the research and paper writing process. We also sincerely thank the editorial department of the journal for their prompt handling of the manuscript. Finally, we sincerely appreciate the professional comments provided by the anonymous reviewers.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Longyi Wang, Xizhe Li, Ya’na Chen, Nijun Qi, Wenxuan Yu, Yuhang Zhou, Yaqi Zhao and Jing Xiang were employed by the PetroChina company. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Parnell, J.; Middleton, D.; Chen, H.H.; Hall, D. The use of integrated fluid inclusion studies in constraining oil charge history and reservoir compartmentation: Examples from the Jeanne d’Arc Basin, offshore Newfoundland. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2001, 18, 535–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walderhaug, O. Temperatures of quartz cementation in Jurassic sandstones from the Norwegian Continental Shelf: Evidence from fluid inclusions. J. Sediment. Res. Sect. A Sediment. Petrol. Process. 1994, 64, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Li, X.; Guo, W.; Lin, W.; Hu, Y.; Han, L.; Qian, C.; Zhao, J. Enlightenment of calcite veins in deep Ordovician Wufeng–Silurian Longmaxi shales fractures to migration and enrichment of shale gas in southern Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2023, 50, 1374–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Guo, X.; He, Z.; Yun, N.; Tao, Z.; Wang, F. Determination of multistage oil charge processes in the Ediacaran Dengying gas reservoirs of the southwestern Sichuan basin, SW China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2024, 164, 106853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Chen, H.; Li, C.; Liu, X.; Wang, Z.; Jiang, H.; Wang, Z. Fluid Inclusion Evidence for Oil Charge and Cracking in the Cambrian Longwangmiao Dolomite Reservoirs of the Central Sichuan Basin, China. Geofluids 2022, 2022, 019100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Liu, K.; Liu, J.; Yu, S.; Yu, B.; Hou, M.; Wu, L. Petroleum charge history of deeply buried carbonate reservoirs in the Shuntuoguole Low Uplift, Tarim Basin, west China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 128, 105063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Guo, X.; He, Z.; Tao, Z.; Zhu, H.; Luo, T.; Zhang, D.; Sun, Z. Maturity assessment of solid bitumen in the Sinian carbonate reservoirs of the eastern and central Sichuan Basin, China: Application for hydrocarbon generation modelling. Geol. J. 2022, 57, 4662–4681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; He, S.; Guo, X.; Wu, Z.; Zhai, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, M.; Xiao, Q. Pressure–temperature–time–composition (P–T–t–x) of paleo–fluid in Permian organic–rich shale of Lower Yangtze Platform, China: Insights from fluid inclusions in fracture cements. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 126, 104936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, X.; Zhou, G.; Chen, X.; Hu, K.; Cao, J. Fluid inclusion evidence for overpressure-induced self-sealing and accumulation of deep shale gas. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2024, 267, 106154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; He, S.; Zhao, J.-x.; Yi, J. Geothermometry and geobarometry of overpressured lower Paleozoic gas shales in the Jiaoshiba field, Central China: Insight from fluid inclusions in fracture cements. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2017, 83, 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankrushina, E.A.; Votyakov, S.L.; Ankusheva, N.N.; Pritchin, M.E.; Kisin, A.Y.; Shchapova, Y.V.; Znamensky, S.E. Raman Spectroscopy in the Analysis of Fluid Inclusion Composition in Quartz from Gold Deposits of the Southern Urals: Methodological Aspects. In Proceedings of the 5th International Young Researchers’ Conference on Physics, Technologies and Innovation (PTI, Ural Fed Univ, Inst Phys & Technol, Ekaterinburg, Russia, 14–18 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Fall, A.; Eichhubl, P.; Cumella, S.P.; Bodnar, R.J.; Laubach, S.E.; Becker, S.P. Testing the basin-centered gas accumulation model using fluid inclusion observations: Southern Piceance Basin, Colorado. AAPG Bull. 2012, 96, 2297–2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.G.; Jarvis, I.; Gillmore, G.; Stephenson, M. Raman spectroscopy as a tool to determine the thermal maturity of organic matter: Application to sedimentary, metamorphic and structural geology. Earth Sci. Rev. 2019, 198, 102936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wopenka, B.; Pasteris, J.D.; Freeman, J.J. Analysis of individual fluid inclusions by Fourier transform infrared and Raman microspectroscopy. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1990, 54, 519–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironon, J.; Grimmer, J.O.W.; Teinturier, S.; Guillaume, D.; Dubessy, J. Dissolved methane in water: Temperature effect on Ramanquantification in fluid inclusions. J. Geochem. Explor. 2003, 78–79, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Qiao, S.; Lu, W.; Hu, Q.; Chen, S.; Liu, Y. An equation for determining methane densities in fluid inclusions with Raman shifts. J. Geochem. Explor. 2016, 171, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, I.M.; Song, Y.C.; Burruss, R.C. A new method for synthesizing fluid inclusions in fused silica capillaries containing organic and inorganic material. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2008, 72, 5217–5231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyssac, O.; Goffé, B.; Chopin, C.; Rouzaud, J.N. Raman spectra of carbonaceous material in metasediments: A new geothermometer. J. Metamorph. Geol. 2002, 20, 859–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.G.; Jarvis, I.; Gillmore, G.; Stephenson, M. A rapid method for determining organic matter maturity using Raman spectroscopy: Application to Carboniferous organic-rich mudstones and coals. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2019, 203, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, G.; Jiang, B.; Li, M.; Li, F.; Zhu, M. Structural evolution of southern Sichuan Basin (South China) and its control effects on tectonic fracture distribution in Longmaxi shale. J. Struct. Geol. 2021, 153, 104465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, H.; Xu, J.; Wu, Y.; Gao, Z. Effects of Fracture Formation Stage on Shale Gas Preservation Conditions and Enrichment in Complex Structural Areas in the Southern Sichuan Basin, China. Front. Earth Sci. 2022, 10, 921988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wang, X.L.; Liu, X.; Cao, J.; Liu, Y.F.; Xi, B.B.; Gao, W.L. In situ Raman spectroscopic quantification of CH4-CO2 mixture: Application to fluid inclusions hosted in quartz veins from the Longmaxi Formation shales in Sichuan Basin, southwestern China. Pet. Sci. 2020, 17, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Xiao, Z.; Dong, C.; Ye, X.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Ma, L.; Xu, Y. The geochemical characteristics and gas potential of the Longtan formation in the eastern Sichuan Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 179, 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, B.; Yao, Y.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Xiao, W.; Wang, Y. Organic matter accumulation mechanism and characteristics in marine-continental transitional shale: A case study of the upper Permian Longtan Formation from the Well F5 in Sichuan Basin, China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; He, S.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Zhai, G.; Huang, Z.; Yang, W. Comparative study on pore structure characteristics of marine and transitional facies shales: A case study of the Upper Permian Longtan Formation and Dalong Formation in the Lower Yangtze area, south China. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 215, 110578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Yu, Y.; Zhai, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, G.; Guo, Y.; Gao, J. Paleogeography and shale development characteristics of the Late Permian Longtan Formation in southeastern Sichuan Basin, China. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 95, 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Z.-S.; Fan, J.-X.; Henderson, C.M.; Yuan, D.-X.; Shen, B.-H.; Wu, J.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, Q.-F.; Zhang, Y.-C.; Wu, Q.; et al. Dynamic palaeogeographic reconstructions of the Wuchiapingian Stage (Lopingian, Late Permian) for the South China Block. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2020, 546, 109667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Deng, X.; Deng, Y. Diagenesis of marine-continental transitional shale from the Upper Permian Longtan Formation in southern Sichuan Basin, China. Open Geosci. 2024, 16, 0696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Guo, T.; Liu, B.; Li, M.; Xiong, L.; Dong, X.; Zhang, N.; Wang, T. Lithofacies and pore features of marine-continental transitional shale and gas enrichment conditions of favorable lithofacies: A case study of Permian Longtan Formation in the Lintanchang area, southeast of Sichuan Basin, SW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2022, 49, 1310–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Chen, Y.n.; Han, D. Pore Structure and Fractal Characteristics of Inter-Layer Sandstone in Marine–Continental Transitional Shale: A Case Study of the Upper Permian Longtan Formation in Southern Sichuan Basin, South China. Fractal Fract. 2024, 9, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Lin, L.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; Li, D.; Tian, J.; Zhou, W.; He, J. Characteristics of Mineralogy, Lithofacies of Fine-Grained Sediments and Their Relationship with Sedimentary Environment: Example from the Upper Permian Longtan Formation in the Sichuan Basin. Energies 2021, 14, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, X.; Chen, Y.n.; Guo, W.; Pei, X.; Luo, C.; Tian, C.; Zhang, J.; Qi, N.; He, W.; et al. Identification and Application of Favorable Lithofacies Associations in the Transitional Facies of the Permian Longtan Formation in Central and Southern Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2025, 15, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Littke, R.; Qin, S.; Huang, Y.; He, S.; Zhai, G.; Huang, Z.; Wang, K. Multi-Scale Pore Structure of Terrestrial, Transitional, and Marine Shales from China: Insights into Porosity Evolution with Increasing Thermal Maturity. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, M.; Wei, S.; Cai, Q.; Fu, W.; Shi, F.; Zhang, L.; Ding, H. Factors Controlling the Pore Development of Low-Mature Marine–Continental Transitional Shale: A Case Study of the Upper Permian Longtan Shale, Western Guizhou, South China. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, B.; Morris, E. The preparation of double-polished fluid inclusion wafers from friable, water-sensitive material. Mineral. Mag. 1992, 56, 120–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aplin, A.C.; Macleod, G.; Larter, S.R.; Pedersen, K.S.; Sorensen, H.; Booth, T. Combined use of Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy and PVT simulation for estimating the composition and physical properties of petroleum in fluid inclusions. Mar. Pet. Geol. 1999, 16, 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, R.; Huang, Y.; Luo, J.; Li, S.; Wen, Z.; Guo, X.; Tao, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yi, Y. Tracking CO2 migration and accumulation in the Subei Basin using geochronology and fluid inclusion quantitative analysis. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 7582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pironon, J. Fluid inclusions in petroleum environments: Analytical procedure for PTX reconstruction. Acta Petrol. Sin. 2004, 20, 1333–1342. [Google Scholar]

- Xi, B.; Jiang, H.; Xu, J.; Chen, Q.; You, D. Reconstruction of paleo-temperature and pressure of oil reservoirs based on PVTx simulation: Problems, strategies and case studies. Pet. Geol. Exp. 2021, 43, 886–895. [Google Scholar]

- Fabre, D.; Thiery, M.M.; Vu, H.; Kobashi, K. Raman-spectra of solid CH4 under pressure.1. Phase-transition between phases-II and phases-III. J. Chem. Phys. 1979, 71, 3081–3088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.; Bodnar, R.J.; Becker, S.P. Experimental determination of the Raman CH4 symmetric stretching (ν1) band position from 1–650bar and 0.3–22 °C: Application to fluid inclusion studies. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2007, 71, 3746–3756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chou, I.M.; Burruss, R.C.; Song, Y. A unified equation for calculating methane vapor pressures in the CH4–H2O system with measured Raman shifts. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 2007, 71, 3969–3978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Chou, I.M.; Chen, Y. Quantitative Raman spectroscopic study of the H2─CH4 gaseous system. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2018, 49, 710–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, B.; Shen, B.; Jiang, H.; Yang, Z.; Wang, X. The trapping temperature and pressure of CH4-H2O-NaCl immiscible fluid inclusions and its application in natural gas reservoir. Nat. Gas Geosci. 2020, 31, 923–930. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Z.; Moller, N.; Weare, J.H. An equation of state for the CH4-CO2-H2O system: II. Mixtures from 50 to 1000 °C and 0 to 1000 bar. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 2619–2631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Moller, N.; Weare, J.H. An Equation of State for the CH4-CO2-H2O System: I. Pure systems from 0 °C to 1000 °C and 0 to 8000 Bar. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 2605–2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; He, S.; Zhang, B.; He, Z.; Chen, M.; Zhang, D.; Li, T.; Gao, J. Characteristics of paleo-temperature and paleo-pressure of fluid inclusions in shale composite veins of Longmaxi Formation at the western margin of Jiaoshiba anticline. Acta Pet. Sin. 2018, 39, 402–415. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.; Faisal, S.; Khan, A.; Rehman, H.U. RAMAN Analysis of Carbonaceous Material and Deduced Peak Metamorphic Temperatures of Metasediments From Western Himalaya, NW Pakistan. Geol. J. 2024, 60, 387–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, D.G.; Jarvis, I.; Gillmore, G.; Stephenson, M.; Emmings, J.F. Assessing low-maturity organic matter in shales using Raman spectroscopy: Effects of sample preparation and operating procedure. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2018, 191, 135–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R.W.T.; Wang, M.; Gan, H.; Li, Z. A RaMM study of thermal maturity of dispersed organic matter in marine source rocks. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2015, 150–151, 252–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R.W.T.; Boudou, R.; Sherwood, N.; Xiao, X. Thermal maturity evaluation from inertinites by Raman spectroscopy: The ‘RaMM’ technique. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2014, 128–129, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xiao, X.; Tian, H.; Min, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Cheng, P.; Shen, J. Sample maturation calculated using Raman spectroscopic parameters for solid organics: Methodology and geological applications. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2012, 58, 1285–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkins, R.W.T.; Sherwood, N.; Li, Z. RaMM (Raman maturity method) study of samples used in an interlaboratory exercise on a standard test method for determination of vitrinite reflectance on dispersed organic matter in rocks. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2018, 91, 236–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goryl, M.; Banasik, K.; Smolarek-Lach, J.; Marynowski, L. Utility of Raman spectroscopy in estimates of the thermal maturity of Ediacaran organic matter: An example from the East European Craton. Geochemistry 2019, 79, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Li, Z. Thermal maturity evaluation of sedimentary organic matter using laser Raman spectroscopy. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37, 1129–1136. [Google Scholar]

- Hackley, P.C.; Lünsdorf, N.K. Application of Raman Spectroscopy as Thermal Maturity Probe in Shale Petroleum Systems: Insights from Natural and Artificial Maturation Series. Energy Fuels 2018, 32, 11190–11202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosasco, G.J.; Roedder, E.; Simmons, J.H. Laser-excited Raman spectroscopy for nondestructive partial analysis of individual phases in fluid inclusions in minerals. Science 1975, 190, 557–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasteris, J.D.; Kuehn, C.A.; Bodnar, R.J. Applications of the Laser Raman Microprobe Ramanor U-1000 to Hydrothermal Ore-Deposits—Carlin as an Example. Econ. Geol. 1986, 81, 915–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mernagh, T.P.; Wilde, A.R. The use of the laser Raman microprobe for the determination of salinity in fluid inclusions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 765–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneki, S.; Kouketsu, Y. An automatic peak deconvolution method for Raman spectra of terrestrial carbonaceous material for application to the geothermometers of Kouketsu et al. (2014). Isl. Arc 2022, 31, e12467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wen, S.; Yang, K.; Ma, K.; Wang, P.; Xu, C.; Cao, G. Diagenetic Evolution Sequence and Pore Evolution Characteristics: Study on Marine-Continental Transitional Facies Shale in Southeastern Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2023, 13, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilkinson, J.J. Metastable freezing: A new method for the estimation of salinity in aqueous fluid inclusions. Econ. Geol. 2017, 112, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grützner, T.; Bureau, H. Heavy halogen impact on Raman water bands at high pressure: Implications for salinity estimations in fluid inclusions. Chem. Geol. 2024, 654, 122065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, D.L.; Sterner, S.M. Preferential water loss from synthetic fluid inclusions. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1993, 114, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.L.; Bodnar, R.J. Synthetic fluid inclusions: IX. Critical PVTX properties of NaCl-H2O solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1989, 53, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodnar, R.J. Revised equation and table for determining the freezing point depression of H2O-NaCl solutions. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1993, 57, 683–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, H.; Xiao, X.; Li, P.; Wang, B. Characterization of the shale gas formation process based on fluid inclusion evidence: An example of the Lower Cambrian Niutitang shale formation, Xiushan section, southeastern Chongqing. Earth Sci. Front. 2023, 30, 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, E.A.J. Raman microspectrometry of fluid inclusions. Lithos 2001, 55, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frezzotti, M.L.; Tecce, F.; Casagli, A. Raman spectroscopy for fluid inclusion analysis. J. Geochem. Explor. 2012, 112, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Xie, W.R.; Wu, S.J.; Shuai, Y.H.; Ma, X.Z. Data credibility evaluation method for formation water in oil and gas fields and its influencing factors. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2025, 52, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Deng, B.; Zhong, Y.; Wen, L.; Sun, W.; Li, Z.; Jansa, L.; Li, J.; Song, J.; et al. Tectonic evolution of the Sichuan Basin, Southwest China. Earth Sci. Rev. 2021, 213, 103470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Shi, X.; Xu, H.; Cao, Q.; Pei, X.; Wu, W.; Wang, L.; Yang, X. Study on the Sedimentary Environments and Its Implications of Shale Reservoirs for Permian Longtan Formation in the Southeast Sichuan Basin. Minerals 2023, 13, 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Q.; Qiu, N.; Fu, X.; Li, W.; Liu, X.; Ji, R. Maturity evolution of Permian source rocks in the Sichuan Basin, southwestern China: The role of the Emeishan mantle plume. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2022, 229, 105180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, D.; Sun, P.; Bai, Y.; Lei, X.; Wang, Z.; Tao, L.; Luan, Z. An FR–IR model method for restoring the original organic geochemical parameters of high over-mature source rocks with types I and II kerogen in China. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 228, 211971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Zhong, N.; Tang, Y. Pore Structure of Organic Matter in the Lacustrine Shale from High to Over Mature Stages: An Approach of Artificial Thermal Simulation. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 17784–17796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, Y.; Sun, H.; Tang, D.; Xu, L.; Zhang, B.; Chen, X.; Xu, C.; Wang, J.; Chen, S. Potential for the production of deep to ultradeep coalbed methane resources in the Upper Permian Longtan Formation, Sichuan Basin. Coal Geol. Explor. 2024, 52, 102–112. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).