Abstract

Significant thermal dynamics occur during both well construction and injection-production cycles in underground energy storage systems. Accurately determining the wellbore temperature distribution is crucial for optimizing drilling processes, enhancing energy storage efficiency, and evaluating reservoir thermal impacts. Existing measurement-while-drilling (MWD) temperature technologies are mostly limited to single-point measurements at the bottomhole, making it difficult to obtain a full wellbore temperature profile. This study proposes a novel microchip logging technology that achieves breakthroughs in power control and high-temperature resistance through optimized system architecture and workflow, with a maximum operating temperature of 160 °C and the ability to function continuously for 5 h under high-temperature conditions. Field tests successfully captured dynamic temperature data during the microchips’ circulation with the drilling fluid. The study established a temperature field model, applied the temperature measurement data to the model improvement, and analyzed the temperature evolution laws throughout the entire process, including bottomhole circulation, reaming operations, and microchip deployment. The model exhibits excellent consistency with the measured values, which is significantly higher than that of traditional models. The research indicates that this technology can be extended to temperature monitoring during cyclic injection and production processes in underground energy storage systems, supporting the design and operation of underground renewable energy storage (URES) systems.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the large-scale development of renewable energy and rapid advancements in underground storage technologies have heightened the demand for dynamic temperature monitoring of reservoirs and wellbores throughout their entire operational cycles. In applications such as compressed air energy storage, aquifer storage, and deep geothermal reservoirs, temperature variations directly impact energy storage efficiency, fluid migration characteristics, and wellbore structural integrity. Although numerical simulations can predict wellbore-reservoir heat exchange behavior, they often lack sufficient effective measured data to validate model reliability and convective heat transfer coefficients [1,2,3]. Current downhole temperature measurement methods, such as distributed optical fiber sensors and fixed sensors, are primarily suited for long-term monitoring after well completion, yet they struggle to capture full wellbore dynamic temperature profiles during drilling or cyclic injection-production processes. This limitation introduces uncertainties in temperature field models when characterizing transient thermal processes.

Accurate characterization of wellbore temperature fields is critical for the design and evaluation of underground energy storage systems, and the industry has long sought to measure full wellbore temperature distributions directly [4]. Early methods relied on temperature-sensitive spheres that changed color or melting state to estimate bottomhole circulation temperature (BHCT), but these approaches suffered from poor accuracy and an inability to determine temperatures at specific depths. Currently, wellbore temperature measurement technologies are mainly categorized into two types: dynamic temperature measurement (e.g., directional tools such as Logging While Drilling (LWD) for temperature measurement and Rotary Steerable System (RSS) with temperature sensing functions) and static temperature measurement (e.g., Distributed Temperature Sensing (DTS) system) [5,6]. Taking oil and gas development in the Sichuan Basin of China as an example, ultra-deep vertical wells generally do not carry directional tools (a simplified bottomhole assembly is adopted to facilitate the handling of complex downhole accidents), making temperature measurement unavailable. For ultra-deep directional wells or horizontal wells, the directional tools can only measure the temperature near the drill bit. These measurement results are not only affected by axial heat conduction generated by high-temperature rock breaking at the drill bit but also exhibit a delayed response to downhole temperature changes, as the sensors are usually built into the instruments. The location of the maximum temperature (hot spot) in the wellbore is not at the bottomhole but at a certain distance above it [7], and this hot spot fails to be captured by the directional tools. The fiber core of the Distributed Temperature Sensing (DTS) technology [8] is wrapped with multiple layers of tensile-resistant and bending-resistant protective layers, which reduces the measurement response speed and accuracy, thereby limiting its application in dynamic operational conditions. Directional tools transmit downhole temperature measurement data through drilling fluid flow; when the fluid in the wellbore is stationary, the data cannot be transmitted out of the wellbore. Therefore, developing a measurement technology that can flow back with fluid circulation and dynamically record the full wellbore temperature profile under both fluid flowing and static states is of great significance for clarifying the heat transfer mechanism between the wellbore and the formation during the injection-production process.

Microchip logging technology has emerged as an innovative solution, gradually applied in downhole parameter acquisition within the petroleum industry since 2010. The first-generation spherical microchip system, collaboratively developed by the University of Tulsa and Saudi Aramco [9], features a diameter of approximately 7.5 mm, a density of about 1.5 g/cm3, and a maximum temperature tolerance of 100 °C. Subsequent second-generation products achieved upgrades in storage capacity, power consumption, and measurement accuracy, with the maximum operating temperature increased to 120 °C [10] and an accuracy of ±1 °C [11]. Field trials demonstrate that this technology can acquire fluid temperature data at different times, enabling the inversion of longitudinal wellbore temperature profiles and providing valuable inputs for temperature field modeling. However, due to thermal insulation of the chip casing, heat dissipation during upward return is slow, resulting in elevated temperature measurements in the upper wellbore sections that require model-based correction [10]. Despite this, the technology has recorded parameters such as well depth, circulation flow rate, and microchip flow time in multiple wells, facilitating integrated interpretation with transient temperature field models [12,13] and validating its applicability in wellbore thermal dynamic analysis.

The research on mathematical models of temperature fields represents the most crucial interpretation method for wellbore temperature distribution. Since the 1960s, relevant studies have been continuously evolving. Based on heat transfer theory, Edwardson [14] proposed a one-dimensional transient temperature field model and a numerical calculation method, and, for the first time, calculated the temperature disturbance curves of the formation around the wellbore under different circulation times. Assuming that the heat exchange between the formation and the fluid in the wellbore is quasi-steady radial linear heat transfer, Holmes [15] established a mathematical temperature model and derived analytical expressions for the fluid temperatures in the wellbore string and annulus. Building upon Bird’s heat flux equation [16], Raymond [17] developed a temperature field model. His research indicated that with the circulation of fluid in the wellbore, both the temperature of the bottom-hole formation and the fluid decreases, and the radial disturbance radius is approximately 3 m, which laid an important foundation for the development of subsequent transient models. Arnold [18] assumed that the wellbore temperature is in a quasi-steady state while the formation temperature is transient. Ignoring heat sources such as viscous dissipation energy and the influence of the wellbore string, he constructed a set of wellbore-formation thermal equilibrium equations and presented analytical solutions for the fluid temperature distribution in the tubing and annulus. Yang [1] developed a transient heat transfer model capable of calculating the temperature variation characteristics of the wellbore and formation under kick conditions. Abdelhafiz [19,20,21] established a two-dimensional transient wellbore model and performed comparative verification using a three-dimensional simulation model in ANSYS 2009, with slight differences between the temperature calculation results of the two models. Over the past few decades, most studies on temperature field models have adopted the 4572 m vertical well and operational conditions initially proposed by Holmes et al. to compare bottom-hole temperature research results, thereby verifying the reliability or applicability of model calculations [22,23,24]. A temperature measurement case from a new directional well is of great significance for advancing the improvement of temperature field models. Meanwhile, numerous scholars have proposed calculation equations for convective heat transfer coefficients under different conditions. To promote the research on temperature fields, it is also necessary to verify the values of key heat transfer coefficients based on the latest temperature measurement technologies.

This paper, based on a new-generation microchip system, outlines key technological breakthroughs in power management, high-temperature resistance, and temperature sensing. Taking drilling fluid circulation as a case study, it systematically elaborates on the field testing method and workflow for monitoring wellbore temperature profiles. A temperature field model was established. This model was compared with representative transient temperature field numerical solution models and quasi-steady-state temperature field analytical models. Additionally, the microchip temperature measurement data were applied to the model improvement. Finally, the temperature evolution laws throughout the entire process, including bottomhole circulation, wellbore reaming, and microchip deployment, were analyzed. This approach provides high-precision empirical evidence and a foundation for model validation in the study of wellbore thermal dynamics during cyclic injection-production processes in underground energy storage systems.

2. Microchip Logging Technology

2.1. Microchip Technical Principles

2.1.1. Microchip System Architecture

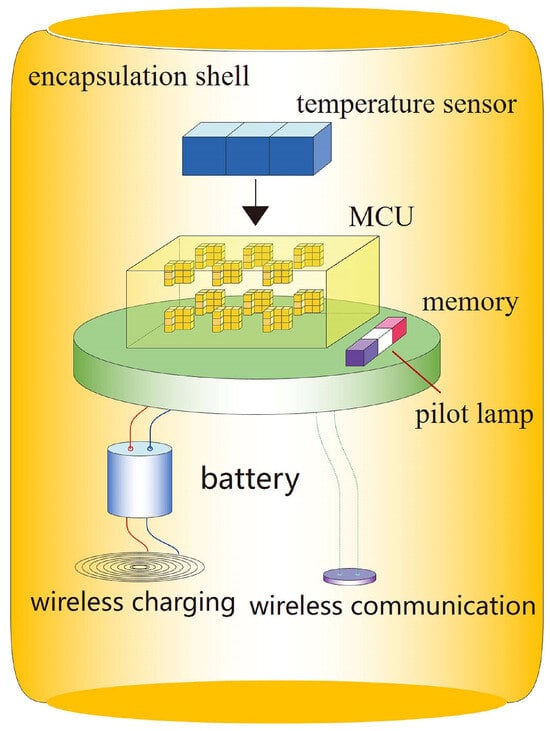

The downhole temperature-measuring microchip is a capsule-shaped instrument, as illustrated in Figure 1. It is distinguished by its compact dimensions and integration of critical components, including a microcontroller, Flash memory, a temperature sensor, a wireless communication module, a battery, and a wireless charging management circuit. The microcontroller—a low-power microprocessing unit (MCU)—functions as the orchestrator of the system’s operational logic, thereby ensuring seamless coordination of all subcomponents. Flash memory is utilized as a permanent storage medium for control program codes and recorded temperature data. If the microchip battery is depleted, it can be recharged, after which data stored in the memory unit can be exported without loss. The temperature sensor, a specialized thermal detection integrated circuit, enables continuous and high-resolution monitoring of ambient temperature fluctuations. The transmission of data, which is utilized for the activation of the chip’s operational protocols and the transfer of measurement results, is facilitated by a wireless communication module that is integrated with a radio frequency (RF) chip. This module is engineered to ensure reliable signal transduction in challenging downhole environments. Power supply is managed via a wireless charging-enabled battery, eliminating the need for physical electrical connections and enhancing system durability during prolonged deployment.

Figure 1.

Functional schematic diagram of downhole temperature-measuring microchip.

All circuitry and components are encapsulated in high-strength resin materials, enabling the microchip to exhibit excellent corrosion resistance and robust impact resistance under the high-temperature and high-pressure conditions of the wellbore. Following assembly of functional subcomponents, the microchip is potted into a capsule shape or other required form using custom molds. The semi-transparent resin not only provides hermetic sealing for the circuitry but also allows unimpeded passage of visible light from indicator lamps and data transmission signals, ensuring seamless optical communication while maintaining structural integrity.

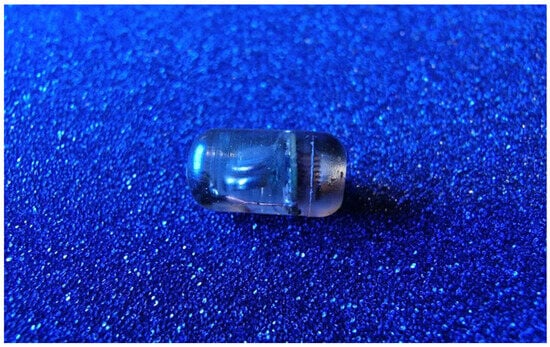

The mass-produced version of the downhole temperature-measuring microchip is shown in Figure 2. It features a capsule-like cylindrical form with a length of approximately 18 mm, a diameter of 10 mm, and an overall density of 1.42 g/cm3. These compact dimensions ensure compatibility with most drilling tools, enabling the microchip—when carried by drilling fluids—to pass through various narrow passages, including bit nozzles, constrictions within drill pipes, and the annular space between pipe exteriors and wellbore walls or the inner casing of previous well sections. The optimally designed size and density allow reliable retrieval of the microchip in both water-based and oil-based drilling fluids under conventional density conditions.

Figure 2.

Photograph of mass-produced logging microchips for drilling.

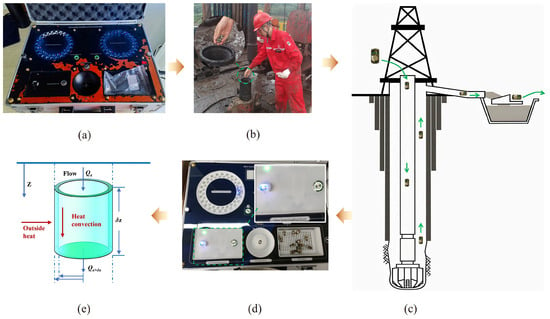

2.1.2. Microchip Temperature Measurement Workflow

The temperature measurement trial process using the microchip is divided into five sequential phases, as illustrated in Figure 3: temperature measurement preparation, wellhead deployment, downhole temperature logging and chip retrieval, data download, and temperature field model interpretation. First phase: Temperature measurement preparation (Figure 3a). One day before the trial, microchips are fully charged via a wireless charging pad and maintained in a charged state (indicated by a constant blue light on the indicator). Thirty minutes prior to wellbore deployment, the chips are sequentially activated using infrared signals (triggering a flashing red light), prompting them to start recording temperature data from sensors at predefined time intervals and store the measurements sequentially in non-volatile memory. Second phase: Wellhead deployment (Figure 3b). Before inserting the chip into the wellbore, drilling fluid circulation is halted, drill pipe collars are repositioned to an optimal height, the drill string is disassembled, an air gun is used to expel a portion of the drilling fluid from the drill pipe interior, the microchip is deployed into the drill pipe, and the string is reassembled. Third phase: Downhole temperature logging and chip retrieval (Figure 3c). The chip flows downward through the internal flow channel of the pipe, exits via the bit nozzles into the bottomhole assembly, ascends through the annular space between the pipe exterior and the wellbore wall, travels through surface pipelines to the vibrating screen at the wellhead, and is collected there. Fourth phase: Data download (Figure 3d). The retrieved microchip is placed in a data transmission chamber, where stored data are transferred to a computer via infrared communication (indicated by a constant blue light and flashing red light during the transfer). Fifth phase: Temperature field model interpretation (Figure 3e). Time-series temperature data points recorded by the microchip are analyzed in conjunction with a transient wellbore temperature field model to characterize temperature distributions and variations across different regions of the wellbore.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of microchip-based temperature measurement workflow. (a) temperature measurement preparation, (b) wellhead deployment, (c) temperature logging and retrieval, (d) data download, (e) temperature field model interpretation.

2.2. New Technical Features of Microchips

The new generation of drilling microchip technology has achieved significant advancements in power supply control and temperature sensing.

2.2.1. Power Supply Control Technology

The microchips should not have an excessively large appearance, so all components are required to be miniaturized to the greatest extent possible while withstanding high-temperature and high-pressure (HTHP) environments and maintaining good stability. The small battery capacity inherently demands ultra-low power consumption circuitry while maximizing energy storage density. To meet operational requirements, a specialized miniature button-type rechargeable lithium battery with high temperature resistance and reliability is selected as the power source. This battery exhibits excellent high-temperature performance, with a capacity close to 4 mAh, stable low-voltage discharge current, and support for repeated charging. Due to the characteristics of lithium batteries, the discharge rate of the battery under high temperatures is faster than at ambient temperature, which is an unavoidable phenomenon.

The control system has been streamlined to form a minimal circuit configuration using only a processor and minimal external components, enabling functions such as analog-to-digital conversion, data storage, and circuit sleep mode. The overall power consumption has been optimized, with an average current of about 0.1 mA for continuous operation at room temperature and 0.5 mA at a temperature of 150 °C, and its endurance has been improved. To further extend battery life, an intermittent power supply strategy is employed: after each data sampling cycle, power to sensors and other components is disconnected, and the microcontroller transitions from active to sleep mode. Testing shows that under high-temperature conditions, the battery can operate for 5 h with a 3 s power supply interval for temperature measurement—more than doubling the endurance of earlier microchips and making it suitable for temperature logging in ultra-deep well drilling. Prolonging the power supply interval can further increase the battery life.

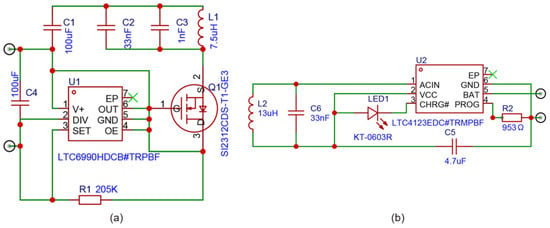

To achieve better application effects, the microchip is designed as a rechargeable type, adopting wireless charging technology to receive energy from electromagnetic waves emitted by a wireless charger. The working principle of the charging circuit is shown in Figure 4, with main functional components including: signal converters (U1, U2), filter capacitors (C1, C3, C4), energy storage capacitors (C2, C6), switching transistor (Q1), resistors (R1, R2), coils (L1, L2), and indicator (LED1). Signal converter U1 (model LTC6990HDCB#TRPB) can convert received wireless electromagnetic waves into alternating current signals, control the generation and conversion of signals, and ensure signal stability through circuit filtering. U2 (model LTC4123EDC#TRMPBF), a charging management chip, is responsible for managing the battery charging process and indicating the charging status through LED1. Filter capacitor C1 (100 μF) is used to filter out low-frequency noise and ensure signal stability, while C3 (33 nF) and C4 (33 nF) are used for high-frequency noise filtering to further stabilize circuit signals. Energy storage capacitors C2 (100 μF) and C6 (33 nF) can smooth the rectified direct current to ensure stability during battery charging. Switching transistor Q1 (model SI2312CDS-T1-GE3) protects the battery and optimizes charging efficiency by regulating current paths. Resistor R1 (205 KΩ) adjusts signals or current in the circuit to ensure the circuit operates within the correct range, and R2 (953 Ω) works with capacitor C5 to regulate charging current for a safe and efficient charging process. Coils L1 (7.5 μH) and L2 (13 μH) are wireless energy receiving coils responsible for receiving electromagnetic waves from the wireless charger and converting them into alternating current signals, serving as key components for power conversion. In addition, the intelligent design of the microchip includes real-time monitoring and adjustment functions, which can automatically adjust charging frequency and voltage according to environmental changes (such as electromagnetic wave intensity, temperature, etc.) to ensure optimal charging performance.

Figure 4.

Schematics of microchip charging circuit. (a) wireless charging signal conversion circuit, (b) wireless charging management and battery charging circuit.

This circuit design not only enables efficient energy conversion and charging management but also ensures the microchip operates stably in complex environments and extends the device’s service life.

2.2.2. Temperature Sensing Technology

The microchip system is equipped with a new-type digital temperature sensor, which has a temperature measurement range of up to 160 °C. By adopting the circuit board heat equalization technology to rapidly cool down the sensor, better new temperature measurement indicators are achieved. During the circulation of drilling fluid, the bottom-hole circulating temperature is generally lower than the original formation temperature. Therefore, the microchip can be used for temperature measurement in the drilling of horizontal wells with formation temperatures above 160 °C and vertical wells with formation temperatures above 170 °C.

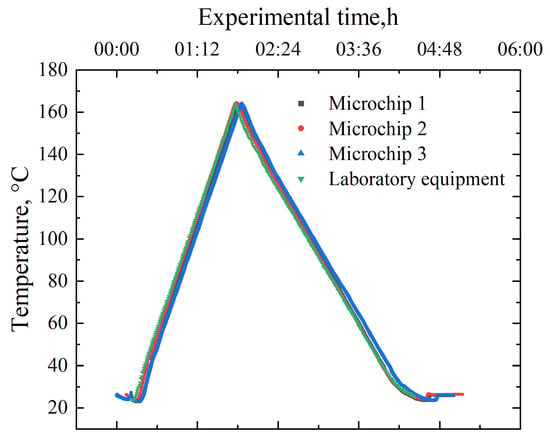

A high-temperature stability experiment of the microchips was carried out. A cementing high-temperature and high-pressure consistometer was used to provide high-temperature experimental conditions. Three microchips were placed into a slurry cup, which was then put into the consistometer. A temperature probe was installed. The program was set to increase the temperature to 164 °C in 1.5 h, and then the kettle body of the consistometer was slowly cooled. After that, the microchips were taken out, and the temperature measurement data of the microchips were read.

Figure 5 shows a comparison between the measured data from three microchips and the measured data from the temperature probe of the high-temperature and high-pressure consistometer. To quantitatively evaluate the measurement deviation of the microchips under high-temperature conditions, statistical analysis was conducted on the maximum temperatures measured by the three microchips, with the consistometer temperature probe serving as the reference standard. The maximum temperature recorded by the consistometer probe was 164.0 °C, while the maximum readings of the three microchips were 163.94 °C, 164.56 °C, and 164.10 °C, respectively, with deviations from the reference standard of −0.06 °C, +0.56 °C, and +0.10 °C in sequence. The average value of the peak temperatures of the three microchips was 164.2 °C, which was only 0.2 °C higher than the reference standard (with a relative error of approximately 0.12%). This indicates that the microchips can still maintain good consistency with the consistometer temperature probe in the high-temperature range above 160 °C, meeting the accuracy requirements for high-temperature wellbore temperature measurement.

Figure 5.

High-temperature performance test of microchips.

2.2.3. Technical Specifications of Microchips

The main specifications of the new generation of drilling temperature measurement microchips are shown in Table 1. The microchips have made certain advancements in operating temperature, density, battery life, wireless control, and wireless data transmission.

Table 1.

Main specifications of drilling temperature measurement microchips.

Compared with other downhole microchips, the new-generation microchip developed in this study exhibits a significant improvement in performance parameters: specifically, its maximum operating temperature is increased to 160 °C (in contrast to approximately 100–120 °C for other products [9,10]), and its measurement accuracy reaches ±0.5 °C (versus ±1 °C for other products [11]). Incorporating an entirely new resin encapsulation technology and circuit design, the microchip features a cylindrical structure, which effectively addresses the heat accumulation issue prevalent in other products. Wireless design is fully adopted for both charging and data transmission, replacing the conventional I/O port design and thereby enhancing the overall sealing performance of the device. Additionally, an indicator is integrated into the microchip to identify the operational status of the microchip system through color cues.

3. Microchip Field Test—A Case Study of Drilling Fluid Circulation

This study conducted a downhole temperature measurement trial in the Ziyang area of the Sichuan Basin, China. Prior to the test, the bottomhole temperature was roughly calculated based on the well depth and operation parameters of the test well to ensure that the dynamic temperature did not exceed the microchips’ temperature measurement upper limit. The test was scheduled after drilling completion, the first wellbore clearout operation, and electric logging. During the second wellbore clearout, the bit was lowered to the planned depth (into the target formation) to deploy microchips for measuring the dynamic temperature of circulating drilling fluid. Prior to the test, the passability of the bottomhole assembly (BHA) used in wellbore clearout was verified, with specific focus on check valve clearances and bit nozzle dimensions.

The operation commenced by disassembling a section of the drill string to deploy microchips into the wellbore. For large quantities of chips, batch release was employed. The flow time inside the pipe was calculated based on fluid velocity. Five minutes before the chips reached the bit, the drill pipe rotation speed was reduced to 10 rpm until the chips reached the bottomhole and passed through the deviated section via the annulus, after which the rotation speed was restored to the conventional value of 60 rpm. Reducing the rotation speed when passing through the bit minimized physical damage to the chips from the bit, while slowing the speed in the deviated section alleviated the risk of chips being squeezed into soft formations and failing to return. Twenty minutes after the chips entered the annulus through the bit nozzles, drilling fluid pumping was halted, the drill string was lowered by 100 m, and circulation was resumed to carry chips that had been washed away by the fluid and could not normally participate in the circulation. These technical measures helped further improve chip recovery rates. The test parameters are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Parameters of field test.

A total of four microchips (denoted as Microchips 1–4) were deployed in the field trial of this study to collect downhole temperature data. All four microchips are identical units of the aforementioned new-generation microchip, with consistent specifications and parameters across the board. The use of multiple identical microchips enables cross-validation of temperature data from multiple groups, thereby ensuring the reliability of the temperature measurement results.

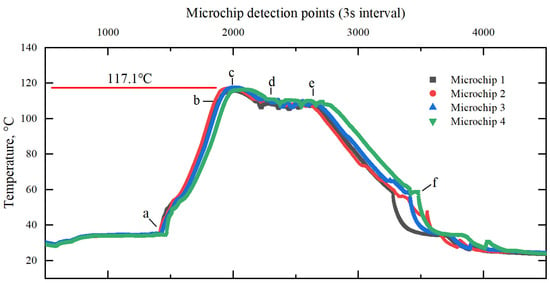

Figure 6 shows the temperature measurement data curves of four microchips. Point a in the figure denotes the initial temperature of measurement; Point b represents the bottomhole temperature; Point c indicates the hot spot temperature of the wellbore fluid; Point d corresponds to the temperature and time when drilling fluid pumping was stopped and the drill string began to be run in hole; Point e signifies the temperature when pumping resumed after the drill string was lowered by 100 m; and Point f stands for the temperature when the microchips were collected at the shale shaker. Before Point a, the microchips measured their internal temperature after activation, which is the surface ambient temperature. During the period from Point a to Point b, the temperature gradually increased to reach the bottomhole temperature, which is not the maximum circulating temperature. Studies have shown that the maximum fluid circulating temperature occurs in the annulus region, 1/10 to 1/6 of the total well depth above the bottomhole [25], and the temperature rises slowly toward the hot spot. From Point b to Point c, the microchips rose with the annulus fluid, and the temperature increased gradually to reach the hot spot temperature. From Point c to Point d, the microchips continued to flow back upward, with the temperature decreasing gradually. During the period from Point d to Point e, fluid circulation in the wellbore ceased as the drill string was being lowered. From Point e to Point f, the microchips entered the annulus flowback phase. The entire process from Point a to Point f lasted approximately 90 min. Due to the low fluid velocity and the tortuous migration path of the microchips, their measurement duration in the annulus was extended, thereby achieving sufficient heat exchange and obtaining accurate temperature data. Aggregated data show an average maximum wellbore temperature of 117.1 °C, 32.1 °C lower than the original bottomhole formation temperature of 149.2 °C.

Figure 6.

Microchip downhole temperature measurement results.

During the period from Point d to Point e, the processes of pumping cessation, three-stage lowering of the drill string to the deep wellbore, and subsequent resumption of pumping circulation were undergone. Corresponding to these operations, four data fluctuations were recorded in the temperature measurements by the microchips. This is because when the drill string was lowered after pumping stopped, the microchips were already located at a well depth far from the bottomhole. Once the drilling fluid circulation ceased, the fluid temperature decreased. However, during the lowering of the drill string, the drilling fluid with a higher temperature was displaced upward and flowed back. After several rounds of temperature reduction, the high-temperature drilling fluid continued to flow back upward, ultimately forming the temperature fluctuation curve between Point d and Point e.

4. Temperature Field Model Calculation Results

The microchip downhole temperature measurement technology enables real-time temperature measurement at any moment after deployment. However, temperature data obtained at different times cannot directly reveal the temperature distribution of drilling fluid at varying well depths inside and outside the drill pipe. Field tests often encounter various special conditions, requiring temporary changes to operational parameters during construction to ensure smooth execution. Additionally, chips generally do not flow straight upward in the annulus. For instance, in this test, to improve chip recovery, operations involved shutting down the pump for drill string lowering followed by resuming pump circulation, during which chips may have briefly sunk toward the wellbore bottom. Therefore, to more accurately characterize the fluid temperature distribution in the wellbore, it is necessary to analyze the evolution law of wellbore temperature within the entire well depth range using a wellbore temperature field model based on microchip test data. Notably, the change in the wellbore temperature field under static fluid conditions is difficult to obtain via measurement-while-drilling (MWD) technology—a limitation of previous microchip temperature measurement technologies—and this approach also helps to further improve the existing understanding of temperature field research.

4.1. Establishment of the Temperature Field Model

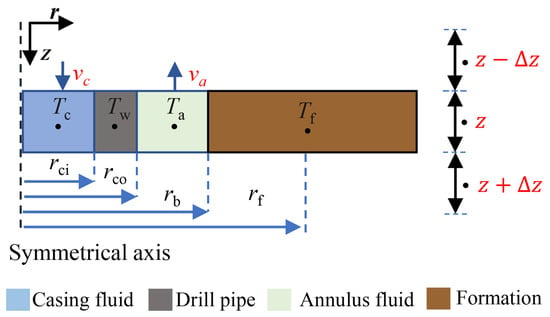

The physical structure of the wellbore is simplified into a two-dimensional axisymmetric geometric structure. The research system for the temperature fields of the wellbore and formation can be divided into four regions, as illustrated in Figure 7. The first region is the tubing fluid with a temperature of Tc; the second is the wellbore string (Tw); the third is the annulus fluid (Ta); and the fourth is the formation (Tf). Coordinate z denotes the axial direction of the wellbore, r represents the radial direction, and t stands for time.

Figure 7.

Area division schematic of temperature field system.

This study focuses primarily on the thermal energy of fluids, and the momentum and mass equations are simplified accordingly. It is assumed that the fluid velocity in the tubing and annulus is uniform, with uniform and constant density and thermophysical properties. Energy balance equations for the four regions are established separately.

Energy balance equation for tubing fluid:

On the left-hand side of Equation (1), it represents the heat accumulation of the fluid over time. The first term on the right-hand side denotes the advective heat transfer of the fluid, i.e., the rate of heat transfer downward along the flow in the tubing. The second term signifies the radial heat transfer between the drill pipe and the fluid in the form of thermal convection. The last term indicates the heat generated by the flow friction of the fluid inside the tubing. In the equation, denotes the density of the drilling fluid, represents the specific heat capacity of the drilling fluid, stands for the inner radius of the tubing, denotes the convective heat transfer coefficient between the fluid in the tubing and the inner wall of the wellbore string, and represents the heat source of the fluid in the tubing.

Energy balance equation for drill pipe string:

On the left-hand side of Equation (2), it represents the heat accumulation of the drill pipe string over time. The first term on the right-hand side denotes the heat transferred through radial thermal convection between the drill pipe string and the annulus fluid. The second term signifies the radial thermal convection between the drill pipe string and the tubing fluid. The last term indicates the heat transferred via axial heat conduction. In the equation, denotes the density of the drill pipe string, represents the specific heat capacity of the drill pipe string, stands for the outer radius of the drill pipe string, denotes the convective heat transfer coefficient between the annulus fluid and the outer wall of the drill pipe string, and represents the thermal conductivity of the drill pipe string.

Energy balance equation for annulus fluid:

On the left-hand side of Equation (3), it represents the heat accumulation of the annulus fluid over time. The first term on the right-hand side denotes the advective heat transfer of the fluid. The second term signifies the heat transferred through radial thermal convection between the wellbore wall and the annulus fluid. The third term indicates the radial thermal convection between the drill pipe string and the annulus fluid. The last term stands for the heat generated by the flow friction of the fluid inside the tubing. In the equation, denotes the wellbore radius, represents the convective heat transfer coefficient between the annulus fluid and the formation, and denotes the heat source of the annulus fluid.

Energy balance equation for formation:

On the left-hand side of Equation (4), it represents the heat accumulation of the formation over time. The first term on the right-hand side denotes the radial heat conduction in the formation, and the second term signifies the axial heat conduction in the formation. In the equation, denotes the distance from the axis of symmetry to the center of the formation control volume, and represents the thermal conductivity of the formation.

4.2. Application of Microchip Temperature Measurement Data in Temperature Field Models

The discretization of the system of equations into an algebraic system is performed. By combining the common initial and boundary conditions for wellbore temperature fields, numerical solutions are conducted for each subdivided unit, and the wellbore temperature distribution is thereby obtained [26].

4.2.1. Operational Parameters for Model Calculation

It has been demonstrated that drilling operations conducted prior to the implementation of microchips within the wellbore can exert an influence on the accuracy of temperature measurement results. In the event that the wellbore undergoes an extended period of inactivity prior to microchip release, bottomhole temperature measurements will exceed actual values. Conversely, prolonged high-displacement circulation will result in lower-than-actual readings. In numerical calculations of temperature fields, initial conditions directly influence solution outcomes. Consequently, precise temperature field model calculations must encompass a comprehensive consideration of drilling procedures and operational parameters prior to microchip deployment, along with any alterations in operational conditions during the testing phase. To this end, variations in wellbore operational conditions before and after the test are tabulated in Table 3, and the temperature field model was used to simulate the entire test process.

Table 3.

Duration of the full test process.

Thermophysical property tests, including density, thermal conductivity, and specific heat capacity, are shown in Table 4. The thermophysical properties of drilling fluid were sampled and tested from the same well after completion. The thermophysical properties of rocks were obtained from reservoir rock samples taken from offset wells in the same block from the core library. Thermal properties of the string were taken as those of plain carbon steel. Rheological parameters of the drilling fluid are listed in Table 2.

Table 4.

Wellbore thermophysical properties.

4.2.2. Comparative Analysis of Multiple Models

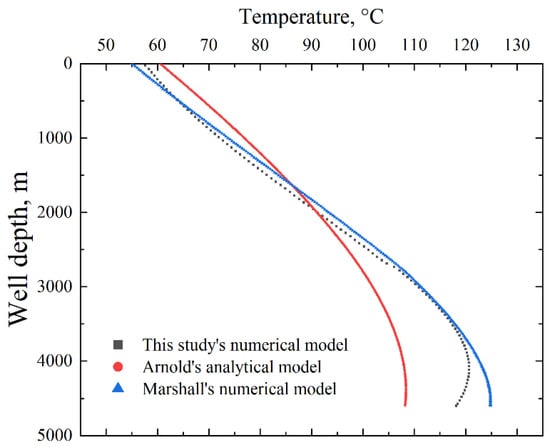

Wellbore temperature field models are mainly categorized into two types: transient temperature field numerical solution models and quasi-steady-state temperature field analytical solution models. Among these, the models proposed by Marshall and Arnold [18] are the most representative. Using the same calculation condition parameters and thermophysical parameters, the model established in this study is compared with these two models, and the results are illustrated in Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Comparison between the model in this study and two types of representative models.

As can be seen from the temperature distribution of the annulus drilling fluid calculated by different models in Figure 8, the results obtained by the model proposed in this study fall between those of the two representative models, indicating certain reliability. The maximum bottom-hole circulating temperature calculated by the model in this study is 120.7 °C, while the numerical solution from Marshall’s transient model is 124.9 °C, and the analytical result from Arnold’s quasi-steady-state model is 108.4 °C. Additionally, the wellhead drilling fluid return temperature computed by the model in this study also lies between the values from the two comparative models, with the temperature being 57.6 °C for the proposed model, 55.0 °C for Marshall’s model, and 60.5 °C for Arnold’s model.

4.2.3. Improvement of the Temperature Field Model Using Microchip Temperature Measurement Values

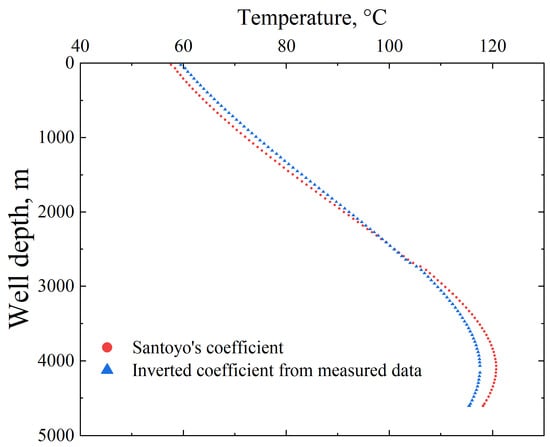

The maximum circulating temperature of the wellbore measured by the microchip is 117.1 °C, while the temperature calculated by the model proposed in this study is 120.7 °C, which is 3.6 °C higher than the measured value. The average outlet temperature measured by the temperature sensor installed at the wellhead is 60.7 °C, and the model-calculated temperature is 57.6 °C, approximately 3.1 °C lower. Through analysis, it is found that this type of temperature calculation error is mainly caused by the excessively high value of the convective heat transfer coefficient between the formation and the annulus fluid. The convective heat transfer coefficient adopted in this study’s model is based on the calculation method recommended by Santoyo [27]. On this basis, combined with the actual microchip measurement values, the calculated value of the convective heat transfer coefficient between the formation and the annulus fluid is inverted and optimized, with the results illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Comparison of temperature distributions with different convective heat transfer coefficients.

By comparing the temperature distributions calculated with the two types of convective heat transfer coefficients, it can be seen that after appropriately optimizing the convective heat transfer coefficient based on the actual measurement data from the microchip, the results calculated by the model are more consistent with the measured values. The maximum bottom-hole circulating temperature of the drilling fluid computed by the model decreases from 120.7 °C to 117.6 °C (measured value: 117.1 °C), and the wellhead return temperature increases from 57.6 °C to 59.4 °C (measured value: 60.7 °C), with the calculation error further reduced. Adopting this inverted convective heat transfer coefficient, the model in this study calculates the temperature field evolution of the entire process test.

4.3. Temperature Field Calculations for the Full-Process Test

To calculate bottomhole temperature using microchip test data and a temperature field model, reasonable initial conditions must be set. During logging and wellbore clearout, drilling fluid in the wellbore remained largely static except for occasional fluid circulation, with bottomhole drilling fluid completely unengaged in circulation. After 49 h of static conditions and heat exchange due to temperature differences, temperatures in all wellbore regions and surrounding formation rocks had essentially stabilized. Consequently, it is hypothesized that when the bit is operated to the planned test depth, the longitudinal temperature distribution in the wellbore and formation is consistent with that of the original formation, and there is no radial geothermal gradient. Model calculations based on these initial conditions will exhibit minimal errors [28]. The full-process test procedure comprises three steps: first, bottomhole circulation; second, Wellbore reaming; third, microchip deployment, as referenced in Table 3.

The wellbore temperature distributions for each stage are calculated sequentially according to the operation procedure. Initially, the temperature fluctuations subsequent to drilling fluid circulation are calculated. Subsequently, an analysis of temperature recovery during wellbore reaming, wherein the drilling fluid remains stationary, is conducted. Subsequently, the temperature variations within the wellbore post-microchip deployment are determined.

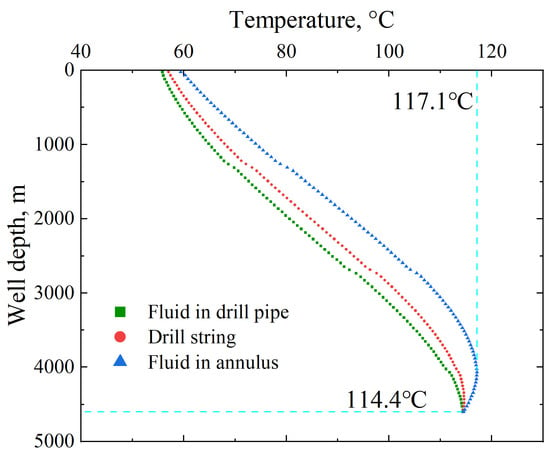

After reaming the wellbore to the bottomhole, circulation for sand cleaning was conducted at a displacement of 31.2 L/s for 2 h and 40 min. The calculated results of the wellbore temperature distribution are shown in Figure 10. Wellbore temperature encompasses the fluid within the drill pipe, the drill string, and the annular fluid. In the radial direction, the annular fluid exhibits the highest temperature, followed by the drill string, with the lowest temperature observed in the internal pipe fluid. In the longitudinal direction, the model assumes equal temperatures for the three regions at the bottomhole; moving upward from the bottom, temperature differences gradually increase with decreasing well depth in the lower wellbore, then diminish again in the upper wellbore. At the end of drilling fluid circulation, the bottomhole temperature measures 114.4 °C, with a hotspot temperature of 117.1 °C occurring at a well depth of 4066 m.

Figure 10.

Wellbore temperature distribution after drilling fluid circulation.

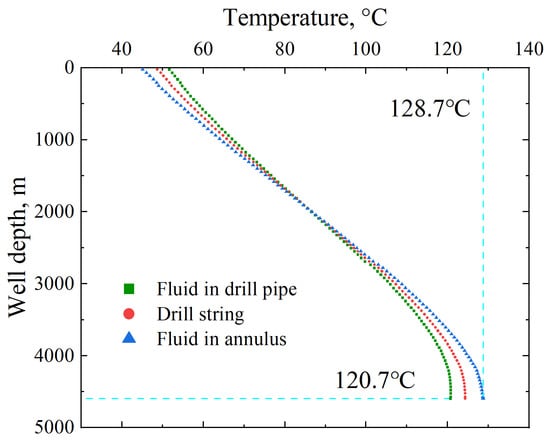

Subsequent to the cessation of circulation, the process of wellbore reaming persisted, accompanied by the maintenance of drilling fluid in a static state for a duration of two hours and 20 min. The calculations pertaining to the temperature changes within the wellbore are illustrated in Figure 11. During the static period, the exchange of heat within the wellbore was predominantly governed by radial heat conduction, with axial heat conduction playing a supplementary role. The phenomenon of spontaneous heat transfer from high-temperature to low-temperature objects is driven by radial temperature differences. A comparison of Figure 10 with Figure 11 reveals that, in the longitudinal direction of well depth, the bottomhole exhibited an increase in temperature, the middle interval demonstrated negligible temperature fluctuations, and the wellhead experienced a decrease in temperature. At the bottomhole, the annular fluid, drill string, and fluid within the drill pipe exhibit a distinct temperature gradient.

Figure 11.

Wellbore temperature distribution after drilling fluid static.

During the stationary period, bottomhole temperature increased: the annular fluid rose from 117.1 °C to 128.7 °C (an increase of 11.6 °C), and the fluid within the drill pipe rose from 114.4 °C to 120.7 °C (an increase of 6.3 °C). Heat transfers from the formation to the annular fluid, which then conducts heat to the drill string and internal pipe fluid—hence the differential temperature increases. With an annual average surface temperature of approximately 17 °C in the Sichuan Basin, once drilling fluid circulation stops, the wellhead temperature rapidly cools: annular fluid temperature is quickly cooled by the formation, decreasing from 59.4 °C to 45.1 °C (a decrease of 14.3 °C).

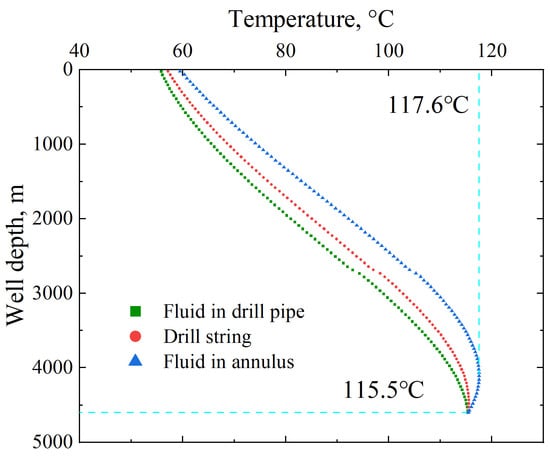

After deploying the microchips into the wellbore, as drilling fluid circulated at a flow rate of 35.8 L/s for 1 h and 30 min, temperature values at different times were recorded. Using the model, the wellbore temperature distribution during the microchip test was calculated, as shown in Figure 12. The model predicted a bottomhole circulation temperature of 115.5 °C, a hotspot temperature of 117.6 °C, and a corresponding well depth of approximately 4112 m. The model results differ from the measured values (Figure 6) by only 0.5 °C, indicating good reliability of the computational outcomes. After circulation, the bottomhole temperature decreased significantly: the annular bottomhole temperature dropped from 128.7 °C to 115.5 °C, a decrease of 13.2 °C.

Figure 12.

Wellbore temperature distribution after microchip deployment.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully developed a new-generation microchip logging technology and, through field trials integrated with a transient temperature field model, revealed dynamic temperature distribution characteristics across the entire wellbore. This provides an important technical means for thermal management in wellbores during renewable energy underground storage processes.

- (1)

- The new-generation microchips have achieved breakthroughs in power management and high-temperature resistance. They can work continuously for more than 5 h in a high-temperature environment of 160 °C, with endurance doubled compared to the initial-generation products. Field tests have been successfully conducted, realizing the dynamic acquisition of the full wellbore temperature profile, which can meet the temperature measurement requirements of deep energy storage wellbores.

- (2)

- A transient wellbore temperature field model was established, and its reliability has been verified by comparing it with other quasi-steady-state analytical models and transient numerical models. However, there are certain gaps between the prediction results of various models and the measured values from the microchips. By applying the temperature measurement data to optimize the convective heat transfer coefficient in the model, the prediction accuracy can reach ±1 °C.

- (3)

- The study found that when the circulation rate is 35.8 L/s, the average maximum temperature of the fluid in the wellbore is 117.1 °C, which is 32.1 °C lower than the original formation temperature. After the fluid circulation, following a 140 min static period, the temperature of the annular fluid near the bottomhole increased by 11.6 °C (rising from 117.1 °C to 128.7 °C).

- (4)

- The microchip logging technology can be extended to energy storage wellbores under various geological conditions, wellbore structures, and fluid types, gradually forming a temperature monitoring technical system applicable to multiple operational scenarios. This provides data support for thermal effect assessment and operational optimization of renewable energy underground storage systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing—original draft, B.F.; Supervision, Project administration, L.H.; Funding acquisition, Methodology, B.O.; Investigation, Validation, Y.-C.Y.; Formal analysis, Resources, D.-L.H.; Investigation, Resources, Z.-R.S.; Data curation, Methodology, Resources, Z.-Y.L.; Review and editing, Visualization, X.-N.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by the Special Project of the Science and Technology Department of Sinopec (No. P24001) and the funding from the State Key Laboratory of Intelligent Construction and Healthy Operation and Maintenance of Deep Underground Engineering (NO. SDGZ2536).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Bo Feng, Yan-Cheng Yan and Da-Liang Hu were employed by the company Sinopec Southwest Oil & Gas Company Petroleum Engineering Technology Research Institute. Authors Long He and Biao Ou were employed by the company Sinopec Southwest Oil & Gas Company. Authors Zhao-Rui Shi was employed by the company Tensing Science and Technology Co. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, M.; Li, X.; Deng, J.; Meng, Y.; Li, G. Prediction of wellbore and formation temperatures during circulation and shut-in stages under kick conditions. Energy 2015, 91, 1018–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabir, C.S.; Hasan, A.R.; Kouba, G.E.; Ameen, M.M. Determining circulating fluid temperature in drilling, workover, and well control operations. Spe Drill. Complet. 1996, 11, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittleston, S.H. A two-dimensional simulator to predict circulating temperatures during cementing operations. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 23–26 September 1990; OnePetro: Dallas, TX, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Aslanyan, A.; Wilson, M.; Al-Shammakhy, A.; Aristov, S. Evaluating Injection Performance with High-precision Temperature Logging And Numerical Temperature Modelling. In Proceedings of the SPE Reservoir Characterization and Simulation Conference and Exhibition, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 16–19 September 2013; p. SPE-166007-MS. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Yao, Z.; Zhang, T.; Chang, Z. Sensing While Drilling and Intelligent Monitoring Technology: Research Progress and Application Prospects. Sensors 2025, 25, 6368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisian, K.W.; Blackwell, D.D.; Bellani, S.; Henfling, J.A.; Normann, R.A.; Lysne, P.C.; Förster, A.; Schrötter, J. Field comparison of conventional and new technology temperature logging systems. Geothermics 1998, 27, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Novotny, R.J. Accurate prediction wellbore transient temperature profile under multiple temperature gradients: Finite difference approach and case history. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, Denver, CO, USA, 3–5 October 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Großwig, S.; Hurtig, E.; Kühn, K. Fibre optic temperature sensing: A new tool for temperature measurements in boreholes. Geophysics 1996, 61, 1065–1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, M.; He, S.; Chen, Y.; Takach, N.; Al-Khanferi, N.M. A Distributed Microchip System for Subsurface Measurement. In Proceedings of the SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition, San Antonio, TX, USA, 8–10 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Gooneratne, C.P.; Bassam, M.K.; Zhan, G. Measurement of temperature in deep reservoir zones by mobile sensor devices. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 12–15 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Gooneratne, C.P.; Badran, M.S.; Shi, Z. Implementation of a Drilling Microchip for Downhole Data Acquisition. In Proceedings of the SPE/IATMI Asia Pacific Oil & Gas Conference and Exhibition, Jakarta, Indonesia, 17–19 October 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Dokhani, V.; Zhan, G.D.; Sehsah, O. Evaluating distribution of circulating temperature in wellbores using drilling microchips. In Proceedings of the Abu Dhabi International Petroleum Exhibition & Conference, Virtual, 9–12 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Dokhani, V.; Gooneratne, C.; Zhan, G.; Shi, Z. Offshore implementation of temperature microchip under critical well conditions. In Proceedings of the SPE Offshore Europe Conference & Exhibition, Virtual, 7–10 September 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Edwardson, M.J.; Girner, H.M.; Parkison, H.R.; Williams, C.D.; Matthews, C.S. Calculation of formation temperature disturbances caused by mud circulation. J. Pet. Technol. 1962, 14, 416–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, C.S.; Swift, S.C. Calculation of circulating mud temperatures. J. Pet. Technol. 1970, 22, 670–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R.B. Solutions to the Class 1 and 2 Problems in Transport Phenomena; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, L.R. Temperature distribution in a circulating drilling fluid. J. Pet. Technol. 1969, 21, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, F.C. Temperature Variation in a Circulating Wellbore Fluid. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 1990, 112, 79–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafiz, M.M.; Hegele, L.A., Jr.; Oppelt, J.F. Numerical transient and steady state analytical modeling of the wellbore temperature during drilling fluid circulation. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2020, 186, 106775. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelhafiz, M.M.; Oppelt, J.; Brenner, G.; Hegele, L.A., Jr. Application of a Thermal Transient Subsurface Model to a Coaxial Borehole Heat Exchanger System. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2022, 227, 211815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhafiz, M.M.; Hegele, L.A.; Oppelt, J.F. Temperature modeling for wellbore circulation and shut-in with application in vertical geothermal wells. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Pu, H.; Sun, Z. Effect of the variations of thermophysical properties of drilling fluids with temperature on wellbore temperature calculation during drilling. Energy 2021, 214, 119055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yang, L.; Wang, T.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Li, L. Estimating formation leakage pressure using a coupled model of circulating temperature-pressure in an eccentric annulus. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2020, 189, 106918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xiong, Y.; Guo, F. Analysis of wellbore temperature distribution and influencing factors during drilling horizontal wells. J. Energy Resour. Technol. 2018, 140, 092901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Kuru, E.; Yan, Y.; Yang, X.; Yan, X. Sensitivity analysis of factors controlling the cement hot spot temperature and the corresponding well depth using a combined CFD simulation and machine learning approach. J. Petrol. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Luo, D.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Tang, D.; Meng, Y. Establishing a practical method to accurately determine and manage wellbore thermal behavior in high-temperature drilling. Appl. Energy 2019, 238, 1471–1483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoyo, E.; Garcia, A.; Espinosa, G.; Santoyo-Gutiérrez, S.; González-Partida, E. Convective heat-transfer coefficients of non-Newtonian geothermaldrilling fluids. J. Geochem. Explor. 2003, 78, 249–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, B.; Li, J.; Li, Z.; Wu, X.; Liu, J.; Huang, S.; Sun, J. Enhancing Environmental Protection in Oil and Gas Wells through Improved Prediction Method of Cement Slurry Temperature. Energies 2023, 16, 4852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).