1. Introduction

Traffic accidents are among the major global social problems, causing a severe loss of life and property. Population growth, the increase in the number of motor vehicles, and the rise in urbanization rates have intensified traffic congestion and accident risk, particularly in metropolitan areas. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), road traffic accidents cause approximately 1.19 million deaths and 20–50 million injuries each year. In

Table 1, the 2023 Global Status Report on Road Safety presents the number of road traffic fatalities by region [

1]. As shown in

Table 2, a substantial portion of these fatalities involves vulnerable road users such as pedestrians, cyclists, and motorcyclists [

1]. This situation underscores the need to strengthen safety measures targeting these vulnerable groups in traffic safety policies. The economic burden of road traffic accidents extends beyond healthcare and treatment costs, as productivity losses and caregiving responsibilities impose additional pressure on families and societies; in many countries, the total cost may reach up to 3% of the gross domestic product (GDP) [

2].

The growing volume of data and the need for advanced analytical methods have promoted the adoption of data-driven approaches in the field of traffic safety. In this context, machine learning (ML) techniques have emerged as powerful tools for understanding the causes of crashes, identifying high-risk areas, and predicting crash probabilities. These methods can uncover patterns and relationships in large and multidimensional datasets by simultaneously analyzing numerous factors such as driver behavior, road conditions, weather, and traffic density, thereby enabling real-time crash risk predictions and the development of preventive strategies [

3,

4,

5]. In the literature, traffic accident classification and prediction are commonly performed using widely adopted machine learning algorithms such as Naïve Bayes, Logistic Regression, k-Nearest Neighbors (k-NN), AdaBoost, Support Vector Machines (SVMs), and Random Forests (RF). These algorithms are preferred due to their distinct structural characteristics and their frequent use in prior studies. As a result, they provide effective outcomes in extracting patterns from crash data and in predicting high-risk locations [

3,

4,

5,

6]. In the field of transportation, the development of applications that ensure operational safety through the use of machine learning and its subfields [

7] can significantly contribute to reducing accident risks. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of ML-based approaches; however, several challenges remain—particularly related to data imbalance, variable heterogeneity, and the need for models that can generalize well for real-world conditions. The primary motivation of this study is the need for a robust analytical framework capable of supporting safety-focused decision making during the project planning stage. In regions such as Şırnak, where rapid development, rural–urban transitions, and challenging topographical conditions coexist, identifying high-risk segments before construction is critical. Early detection enables the implementation of low-cost but high-impact safety countermeasures. However, such predictive assessments require harmonized, well-preprocessed data and advanced learning models that can handle class imbalance—particularly the rarity of fatal crashes.

To address these gaps, this study introduces an integrated machine learning framework that classifies crash severity and identifies high-risk locations using real accident data obtained from the General Directorate of Security (EGM). The proposed approach includes the following key components:

Comprehensive dataset construction consisting of traffic, geometric, and operational variables representing crashes between 2018 and 2023.

Systematic data preprocessing, including cleaning, categorical variable encoding, feature scaling, and variable selection tailored to project-phase road segments.

Addressing class imbalance using the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), enabling improved model sensitivity toward fatal crashes.

Comparative evaluation of five ML algorithms—Logistic Regression, SVMs, MLP, Random Forest, and XGBoost—using performance metrics such as F1-score, ROC-AUC, True/False Alarm rates, and confusion matrices.

Assessment of computational efficiency, highlighting the practical feasibility of using the models in real-time or near real-time decision-support environments.

This methodological structure not only improves the accuracy of predicting fatal crash risk but also enables a deeper understanding of the contributing factors, thus strengthening the scientific basis for transportation safety planning. By applying advanced ML techniques and addressing the critical issue of data imbalance, this study contributes a reproducible, scalable, and practical framework that can guide future infrastructure design and policy development.

As discussed below, various studies have conducted crash analyses using different datasets and modelling techniques. The main purpose and originality of this study lie in addressing existing challenges in data classification and analysis within the field of traffic safety. Specifically, this study focuses on organizing complex and multidimensional data, isolating project-related data, and adapting it for modelling processes. In this way, it aims to more accurately identify high-risk road segments and to make intervention processes predictable at the project planning stage. It is expected that this methodological approach will significantly contribute to the literature.

The remaining paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents related works.

Section 3 describes the dataset and methodology utilized in this study.

Section 4 presents data analyses, discusses the performance of the proposed methods, and evaluates their advantages and limitations.

Section 5 summarizes the study results, outlines the study’s constraints, and provides recommendations for future research.

2. Related Work

A wide range of factors influence the occurrence of traffic accidents, including spatial and temporal elements, driver and pedestrian behavior, road conditions, and collision type. Over the years, many studies have investigated these contributing factors using various analytical methods. For instance, multinomial logit models [

8,

9] have shown that geographic location, weather, and time of day are significant determinants of crash types; ordered probit models [

10] have revealed that rollover, fixed-object, and head-on collisions are the most critical crash types associated with severe injuries; Poisson and negative binomial models have demonstrated that reducing speeding violations could decrease crashes by up to 17% [

11]. Akgungor and Dogan (2010) [

12] developed various crash models for İzmir using regression, artificial neural networks (ANNs), and genetic algorithms. Lin et al. (2019) [

13] proposed the M5P-HBDM model, achieving the lowest mean absolute percentage error (MAPE) in crash duration prediction. Li et al. (2017) [

14] utilized the FARS dataset to examine the relationship between fatality rates and variables such as collision type, weather, and driver intoxication using data mining techniques. While classical statistical models have made significant contributions to crash prediction, recent years have seen a growing preference for machine learning-based methods.

Machine learning algorithms provide an effective approach for predicting crash severity. Techniques such as Random Forest, XGBoost, Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), and Naïve Bayes stand out for their high predictive accuracy, while data imbalance problems are commonly addressed through resampling methods such as the SMOTE and ROSE [

15,

16]. These models enable decision makers to more accurately predict crash severity and accordingly develop preventive strategies.

In academic studies focusing on crash severity prediction, Tang et al. (2025) [

17] proposed multi-stage models integrating Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and tree-based algorithms (e.g., XGBoost, Random Forest) after addressing data imbalance using undersampling and oversampling techniques. Their findings indicated that the MLP–Random Forest integration achieved superior performance with 94% accuracy compared to individual models, and that noise-level sensitivity analyses revealed the model’s robustness. Hamdan and Sipos (2025) [

18] compared algorithms such as Random Forest, XGBoost, and Support Vector Machines (SVMs), showing that while Random Forest achieved high predictive accuracy, XGBoost demonstrated strong capability in capturing complex patterns. The study also highlighted that hybrid or ensemble techniques, such as Voting Classifiers and Gradient Boosting Machines, can enhance predictive performance. Moreover, explainable modelling tools like SHAP were shown to play a crucial role in understanding the influence of factors such as driver behavior and road conditions on crash outcomes. Another study processed large-scale traffic accident data to predict key variables such as crash severity, number of vehicles, and number of injuries; the comparison between decision tree, Random Forest, Logistic Regression, and Naïve Bayes algorithms emphasized the importance of data preprocessing in model performance [

19]. Islam et al. (2022) [

20] compared Random Forest, XGBoost, and Logistic Regression models using crash data from Al-Ahsa, Saudi Arabia, and reported that the Random Forest model achieved the highest accuracy (94%) and F1-score. Spatial autocorrelation analysis and the Getis-Ord Gi* statistic were used to identify crash hotspots, revealing that distraction, speeding, and sudden lane changes significantly contributed to severe crashes. The study recommended the incorporation of SHAP analysis and time-series modelling in future research. Ahmed et al. (2023) [

21] demonstrated that explainable machine learning techniques using SHAP analysis provide transparent predictions for policymakers by revealing both global and local impacts of factors such as road type, weather, and driver behavior.

In studies investigating the role of environmental and spatial factors in crash prediction, one study analyzed in detail the factors affecting crash severity—such as collision type, road type, road geometry, and driver errors—and determined that the Random Forest algorithm was the most successful method. It was particularly found that the time of day was the most significant variable influencing crash occurrence, and the importance of spatial statistical analyses for identifying black spots was emphasized [

22]. Çeven and Albayrak (2024) [

23] modelled three crash severity classes for urban crashes in Kayseri using Random Forest, AdaBoost, and MLP algorithms, revealing that driver errors were the most influential factor with a 64% impact rate. Another study classified fatal and injury crashes in Antalya and found that the Naïve Bayes algorithm achieved the highest accuracy rate of 99.01%. It was further noted that pavement type and road class were decisive variables affecting crash type [

24]. Gollapalli et al. (2025) [

25] analyzed multidimensional data using tools such as Python (version 2025.07) and GeoPandas 1.1.1, highlighting the contribution of K-Means and Random Forest algorithms in the early detection of high-risk times and locations.

In crash studies employing multi-method and hybrid models, Bokaba et al. (2022) [

3] compared various machine learning algorithms using South African data, incorporating missing data imputation and dimensionality reduction techniques (PCA, LDA). They demonstrated that the Random Forest algorithm produced the best results, particularly when combined with the MICE method. Another study focusing on crashes under winter conditions applied spatial interpolation and the SMOTE during preprocessing and reported that the Random Forest model achieved the highest performance, with 98% accuracy and an AUC of 0.907, emphasizing the significance of variables such as road geometry, time, geographic location, and humidity [

16]. Yu et al. (2021) [

26] developed a Deep Spatio-Temporal Graph Convolutional Network (DSTGCN) model that integrated spatial and temporal patterns holistically, outperforming traditional approaches in prediction accuracy. Gutierrez-Osorio and Pedraza (2020) [

27] also noted that deep learning architecture such as CNNs and LSTM enhance analytical performance by integrating heterogeneous data sources and that social media data contribute to the detection of traffic incidents. Another study reported that a hybrid artificial neural network (ANN) model achieved superior performance in crash prediction, with road width, lighting conditions, and speeding violations identified as key determinants [

28]. Thanikachalam et al. (2025) [

29] demonstrated that Gradient Boosting achieved the highest accuracy (88.1%) in smart cities, confirming that ensemble techniques outperform traditional methods.

In accident black spot and high-risk segment analyses, a study conducted in Morocco combined WSI, B-ELM, and OR techniques, achieving an accuracy rate of 98.6% [

30]. Another study on Brazilian highways reported that the MLP neural network model yielded the highest success rate using a balanced dataset [

31]. Santos et al. (2021) [

32] found that the Random Forest model predicted crash hotspot areas in the Setúbal region of Portugal with 73% accuracy. Erzurum Çiçek and Kamisli Ozturk (2022) [

33] proposed a One-Class SVM model for fatal crashes in Eskişehir and demonstrated that it outperformed binary classification models trained with synthetic data.

Recent advances in traffic safety research show a growing reliance on artificial intelligence and machine learning models for predicting crash severity, identifying risk factors, and improving transportation system safety. Obasi and Benson (2023) [

34] employed large-scale urban and regional crash databases and reported that ensemble-based models—particularly Random Forest and Logistic Regression—yield superior F1 scores compared to other classifiers. Benfaress et al. (2024) [

35] demonstrated that ResNet-based deep learning models, complemented with SHAP explanations, can outperform traditional classifiers while offering interpretable insights into key determinants of crash severity. Similarly, Acı et al. (2025) [

36] reported that hybrid Deep Learning–Random Forest architectures enhance multi-class injury severity classification by capturing nonlinear and interaction-based patterns that conventional models may overlook. Transformer-based frameworks, as shown by Jiang et al. (2025) [

37], have further advanced predictive performance by modelling complex contextual dependencies within crash datasets. In the context of risk assessment, Arciniegas-Ayala et al. (2024) [

38] found that CNN and RBFNN models applied to driving-event-enhanced data can effectively estimate accident risk levels, while Angadi and Halyal (2024) [

39] demonstrated that deep learning time-series models are highly capable of forecasting temporal crash trends. The literature also reflects a rising emphasis on explainable AI: Aldhari et al. (2023) [

40] applied SHAP within ensemble learning frameworks to clarify the roles of speed limits, roadway types, and environmental conditions in severity outcomes, and Aboulola et al. (2024) [

41] achieved near-state-of-the-art accuracy using MobileNet- and transformer-based architectures while incorporating SHAP to enhance model transparency. Collectively, these studies highlight the effectiveness of deep learning, transformer models, and hybrid ML approaches in crash severity and risk prediction, and they underline the increasing importance of explainability for supporting data-driven transportation safety interventions.

3. Materials and Methods

This section describes the dataset, preprocessing procedures, and analytical methods used in the study. All steps—from data acquisition and cleaning to class balancing, model training, and performance evaluation—were systematically implemented to ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility.

3.1. Data and Sources

In this study, data on injury and fatal traffic accidents that occurred in the province of Şırnak were utilized. The dataset was officially obtained from the Traffic Department of the General Directorate of Security (EGM) through a formal request. The data used in this study include multidimensional information on each accident’s time, location, environmental conditions, and outcomes. The variables in the dataset encompass temporal and spatial features such as the year, date, time, province, district, neighborhood/village, and X–Y coordinates of the crash location, as well as physical and environmental parameters including road type, pavement type, road class, legal speed limit, number and width of lanes, geometric configuration, surface condition, lane markings, traffic signs, traffic lights, lighting condition, weather conditions, and day/night information.

In addition, outcome-related variables such as crash type, point of first impact, number of vehicles involved, and total number of injuries and fatalities are also included in the dataset. Some of these variables are qualitative (categorical) and suitable for classification tasks (e.g., road type, weather condition, traffic light status), whereas others are quantitative (numerical) and can be directly employed in statistical analyses (e.g., number of fatalities, number of injuries, speed limit).

Table 3 presents selected sample records from traffic accidents that occurred between 2018 and 2023. Only a limited subset of variables is displayed in the table; however, the complete dataset contains a total of 29 variables. One representative record from each year is provided to illustrate the structure and diversity of the dataset.

As the dataset in the Excel format is too large,

Table 3 presents only the overall data limits. The variables/features and value ranges used in this study that could not be included in the table due to size constraints are provided in

Table 4. Additionally, the dataset used in this study can be downloaded from the link provided in the

Supplementary Materials section at the end of the article.

3.2. Data Preprocessing and Sampling Procedure

This subsection outlines the preprocessing steps and sampling strategies applied to prepare the crash dataset for machine learning analysis. The workflow includes the categorization and normalization of input variables, followed by class-balancing procedures to address the pronounced imbalance between accident and fatal crash records.

3.2.1. Data Categorization and Feature Scaling

In this study, the entire set of collected traffic accident data was not utilized; only the records related to geometric road design during the project phase were included in the analysis. This selection is based on the rationale that implementing preventive measures during the design stage—prior to the construction phase—is both more cost-effective and more feasible. In contrast, interventions made after project completion would be more costly and offer only limited practical benefits.

The variables/features incorporated into the analysis, as given in

Table 4, include road type, pavement type, road class, legal speed limit, number of lanes, horizontal curve, vertical curve, intersection, crossing, lane marking, traffic sign, traffic signal, and lighting condition. During the data preprocessing stage, missing values were cleaned, categorical variables/features were appropriately transformed for modelling, and all variables/features were subjected to normalization/scaling procedures. This approach enhanced model accuracy and contributed to identifying high-risk road segments during the project stage.

3.2.2. Synthetic Sample Generation Using the SMOTE

In the dataset, “injury crashes” contained a sufficient number of observations, whereas “fatal crashes” constituted the minority class, which negatively affected model performance. The model’s inability to accurately classify minority instances could lead to these critical cases being overlooked and an increase in the rate of misclassifications. To mitigate this imbalance and improve the model’s sensitivity to the minority class, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) was applied. The SMOTE generates synthetic samples for the minority class using a

k-Nearest Neighbors approach, balancing the class distribution. Compared with traditional oversampling methods that merely duplicate existing samples, the SMOTE reduces the risk of overfitting and enables a more generalizable representation of decision boundaries between classes [

42]. Through this method, the number of “fatal crash” and “injury crash” instances in the training dataset were equalized, thereby addressing class imbalance and enhancing the model’s capability to accurately detect critical cases (fatal crashes).

Several studies have also demonstrated the effectiveness of SMOTE in the context of traffic crash data. For instance, a study conducted in Ethiopia reported a 22% improvement in the recall rate for fatal crashes after applying the SMOTE [

43]. Moreover, research on large-scale crash datasets has shown that the application of SMOTE and similar techniques significantly improves model performance in terms of AUC and F1-score metrics [

44,

45].

3.3. Error Metrics

In this study, F1-score was selected as the primary performance metric for evaluating the classification models. R2, MSE, and MAE are regression-based performance metrics and therefore are not suitable for evaluating classification models. Given the imbalanced nature of the dataset used in this study, F1-score was adopted as the primary evaluation metric, as it provides a more reliable assessment of classification performance by balancing precision and recall for the minority class.

This choice is mainly driven by the highly imbalanced nature of the dataset, in which fatal crashes represent only a small fraction of all recorded incidents. Under such conditions, traditional metrics—particularly accuracy—can be misleading because they tend to reflect the performance of the majority class while overlooking the model’s ability to detect the minority class. F1-score provides a more meaningful assessment by combining precision and recall into a single measure, making it especially suitable for imbalanced classification problems. Consequently, it allows a more accurate evaluation of the model’s effectiveness in identifying fatal crash cases, which are a primary concern in safety studies. The methodology of F1-score is given in reference [

46].

3.4. Evaluation Methodology and Workflow

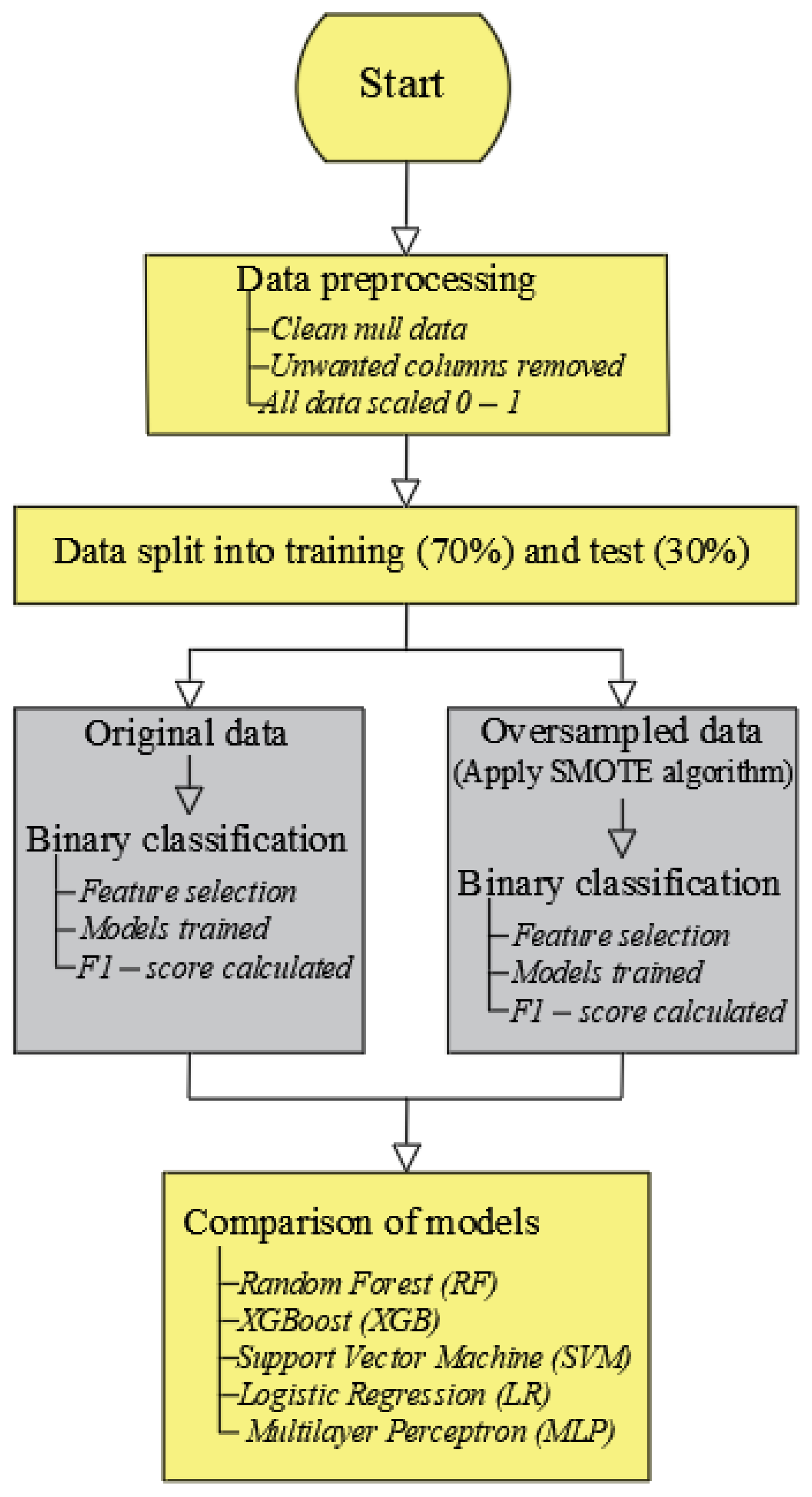

In the evaluation of machine learning models, various methods and performance metrics are employed. At the initial stage, the dataset is typically divided into training and testing subsets (e.g., 70% training and 30% testing) to ensure a clear separation between the model learning process and the independent evaluation phase. Furthermore, to obtain a more reliable and generalizable estimation of model performance, the K-Fold Cross-Validation technique can be applied. This method partitions the dataset into a predefined number of folds, allowing the model to be trained and tested on different combinations of data in each iteration. Several metrics are used to assess model performance. Accuracy represents the overall proportion of correct predictions, while precision indicates how many of the instances predicted as positive are truly positive. Recall, on the other hand, measures how many of the actual positive instances are correctly identified by the model. F1-score provides a harmonic mean of precision and recall, capturing the balance between them, whereas the ROC-AUC metric evaluates the model’s discriminatory power across various threshold settings. When interpreted collectively, these metrics allow for a comprehensive assessment of both the overall performance and the sensitivity of the model to different types of classification errors. As illustrated in the flow diagram in

Figure 1, the data processing phase of this study begins with the cleaning of raw data and its arrangement into an appropriate analytical format. The dataset is then divided into training and testing subsets. To address class imbalance, the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) is applied, ensuring a more balanced data distribution. Following this step, multiple classification algorithms are modelled and evaluated on both the training and test datasets. In the final stage, the results are compared to identify the most suitable model. Additionally, the entire modelling process is repeated without applying the SMOTE, and the model demonstrating the best performance under this condition is also determined. Thus, this methodological framework provides an effective solution to the imbalanced data problem while enabling the selection of the most appropriate model under different scenarios.

In addition, the process illustrated in the flowchart is directly represented in Algorithm 1 as pseudo code. The analyses were conducted using Google Colab with the Python 3 runtime (version 2025.07) on a CPU-only configuration. The default computational environment in Colab includes an Intel(R) Xeon(R) processor running at 2.20 GHz, equipped with 2 virtual CPUs (vCPUs) and 13 GB of RAM.

| Algorithm 1 Pseudo code of workflow |

| BEGIN |

| # Step 1: Data Preprocessing |

| LOAD dataset |

| REMOVE null values |

| REMOVE unwanted columns |

| SCALE all features between 0 and 1 |

| # Step 2: Split Dataset |

| SPLIT dataset into: |

| TRAIN_SET (70%) |

| TEST_SET (30%) |

| # Step 3: Original Data Branch |

| PRINT “Training using original data” |

| SELECT relevant features |

| FOR each model IN [RF, XGB, SVM, LR, MLP]: |

| TRAIN model using TRAIN_SET |

| PREDICT on TEST_SET |

| CALCULATE F1_score_original(model) |

| # Step 4: Oversampling Branch |

| PRINT “Training using SMOTE-oversampled data” |

| APPLY SMOTE on TRAIN_SET to create OVERSAMPLED_TRAIN_SET |

| # SMOTE: find k-nearest neighbors and generate synthetic samples |

| SELECT relevant features |

| FOR each model IN [RF, XGB, SVM, LR, MLP]: |

| TRAIN model using OVERSAMPLED_TRAIN_SET |

| PREDICT on TEST_SET |

| CALCULATE F1_score_SMOTE (model) |

| # Step 5: Comparison of Model Performance |

| CREATE results_table with columns: |

| [Model, F1_original, F1_SMOTE] |

| DISPLAY results_table |

| IDENTIFY best performing model based on F1-scores |

| END |

4. Results and Discussion

In the first stage of this study, traffic accident data were included in the modelling process without applying any balancing technique. At this stage, the training dataset consisted of 2613 injury crashes and only 82 fatal crashes. The test dataset, on the other hand, included 1124 injury crashes and 32 fatal crashes. This distribution clearly indicates that fatal crashes constitute a very small proportion of the total dataset, revealing a significant class imbalance problem.

Table 5 presents the distribution of fatal and injury crashes in the training and test datasets. Additionally, the table compares the original distributions before applying the Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE) with the balanced distributions obtained after applying the SMOTE solely to the training set.

In this study, several machine learning algorithms were employed to classify and estimate traffic crashes as fatal or injury. The models used include Random Forest (RF), Multilayer Perceptron (MLP), Support Vector Machines (SVMs), Logistic Regression (LR), and Extreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost). These algorithms were selected due to their widespread use in crash severity prediction studies in the literature, as well as their ability to capture both linear and nonlinear relationships within the data. The optimal hyperparameter values determined for each model are presented in

Table 6. These parameters were optimized to maximize classification performance, and the final model parameter configurations are summarized in a tabular form. During hyperparameter optimization, the cross-validation grid search method was employed using the scikit-learn (v1.6.1) library [

47]. The details of the hyperparameter optimization can be found in

https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.model_selection.GridSearchCV.html (accessed on 25 July 2025) [

47]. The optimization was performed solely on the training set, and the model’s performance was subsequently evaluated using the test set.

In the initial stage of the analysis, the models were trained and tested on the imbalanced original dataset without applying any oversampling technique. Since the number of fatal crashes was substantially lower than that of injury crashes, it was observed that the models had difficulty in accurately learning the patterns related to the minority class (fatal crashes). This limitation was particularly evident in the True Alarm and False Alarm rates, which play a crucial role in correctly identifying fatal crashes. As presented in

Table 7, the Logistic Regression (LR) model achieved an F1-score of 0.42, with a True Alarm rate of 0.84 and a relatively high False Alarm rate of 0.42. The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and XGBoost (XGB) models faced substantial challenges in detecting the minority class; although they obtained moderate F1-scores of 0.52 and 0.49, respectively, their True Alarm rates remained nearly zero, indicating poor sensitivity to fatal crash instances. The Random Forest (RF) model demonstrated better performance, achieving an F1-score of 0.55 and a True Alarm rate of 0.47. Among all models, the Support Vector Machine (SVM) algorithm provided the most balanced results, yielding an F1-score of 0.52, along with a True Alarm rate of 0.033 and the lowest False Alarm rate of 0.003.

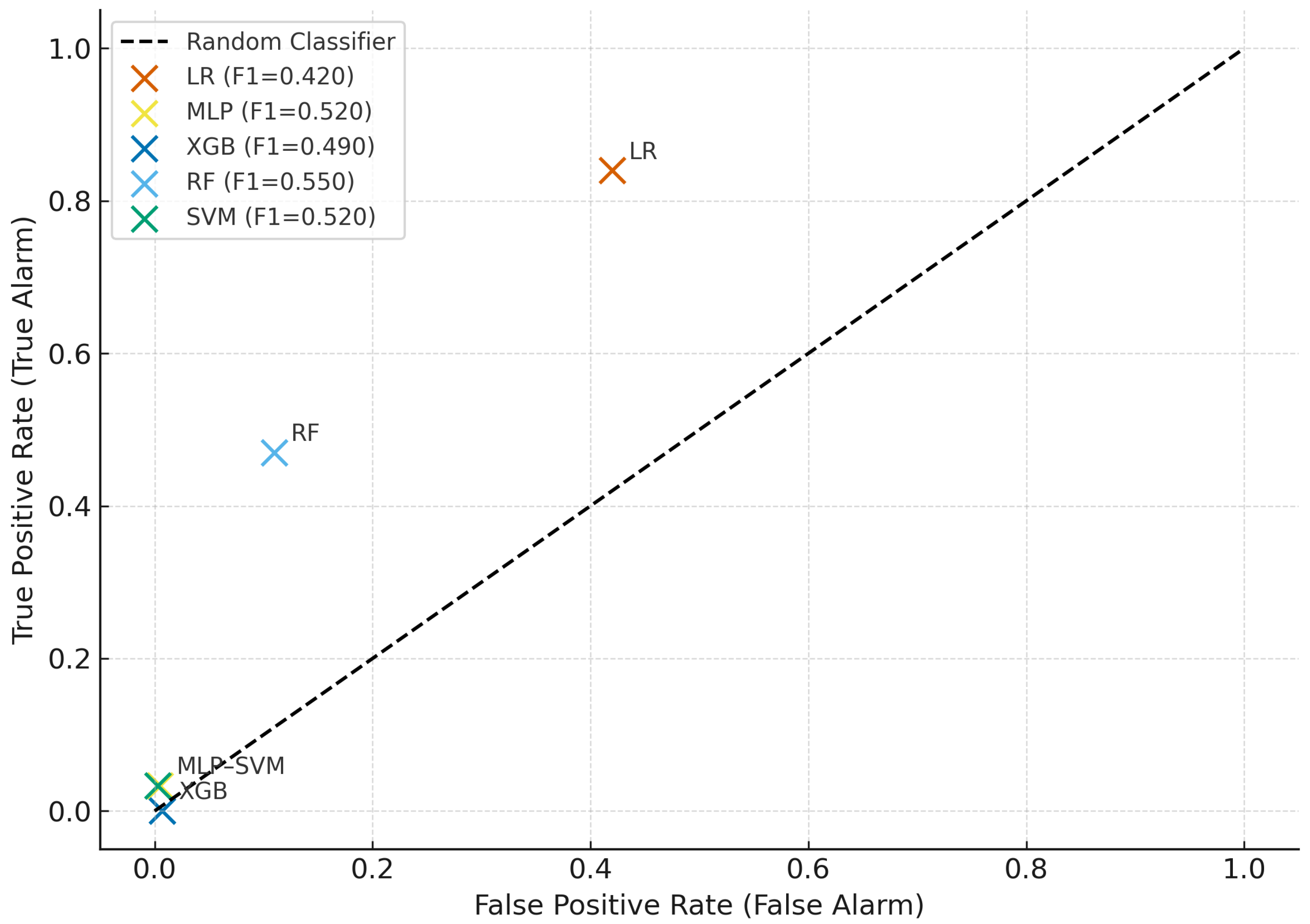

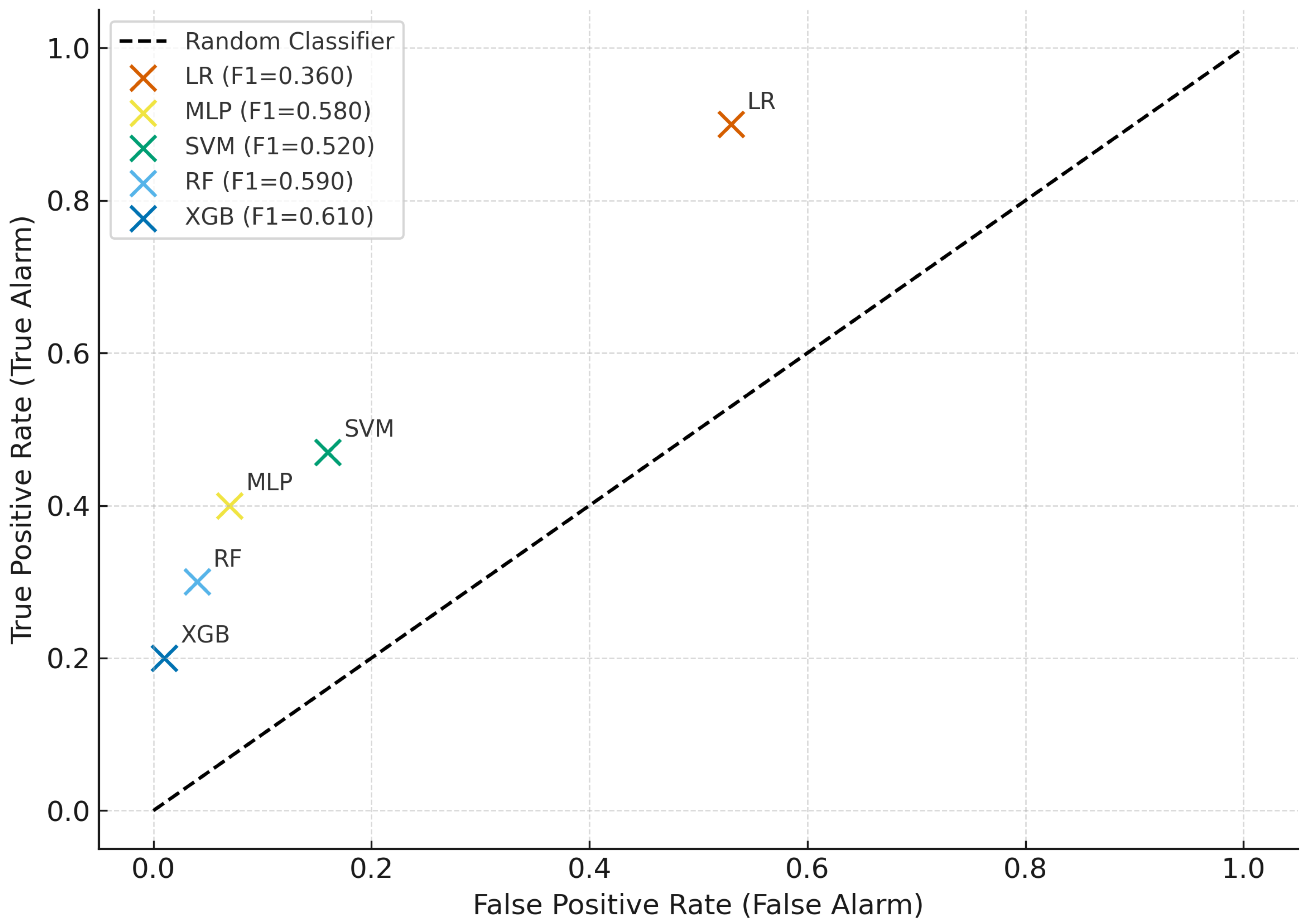

Before applying the SMOTE, the performance of the models trained on the imbalanced dataset is illustrated by the ROC curve presented in

Figure 2. The examination of this curve reveals that the classification performance of the models remains limited, primarily due to the extremely low representation of fatal crashes within the dataset. This imbalance increases the models’ tendency to favor the majority class, resulting in the frequent misclassification of minority class instances. Therefore, considering the critical role of resampling techniques (such as the SMOTE) in improving model performance, it becomes evident that applying a sampling method to the imbalanced dataset is indispensable.

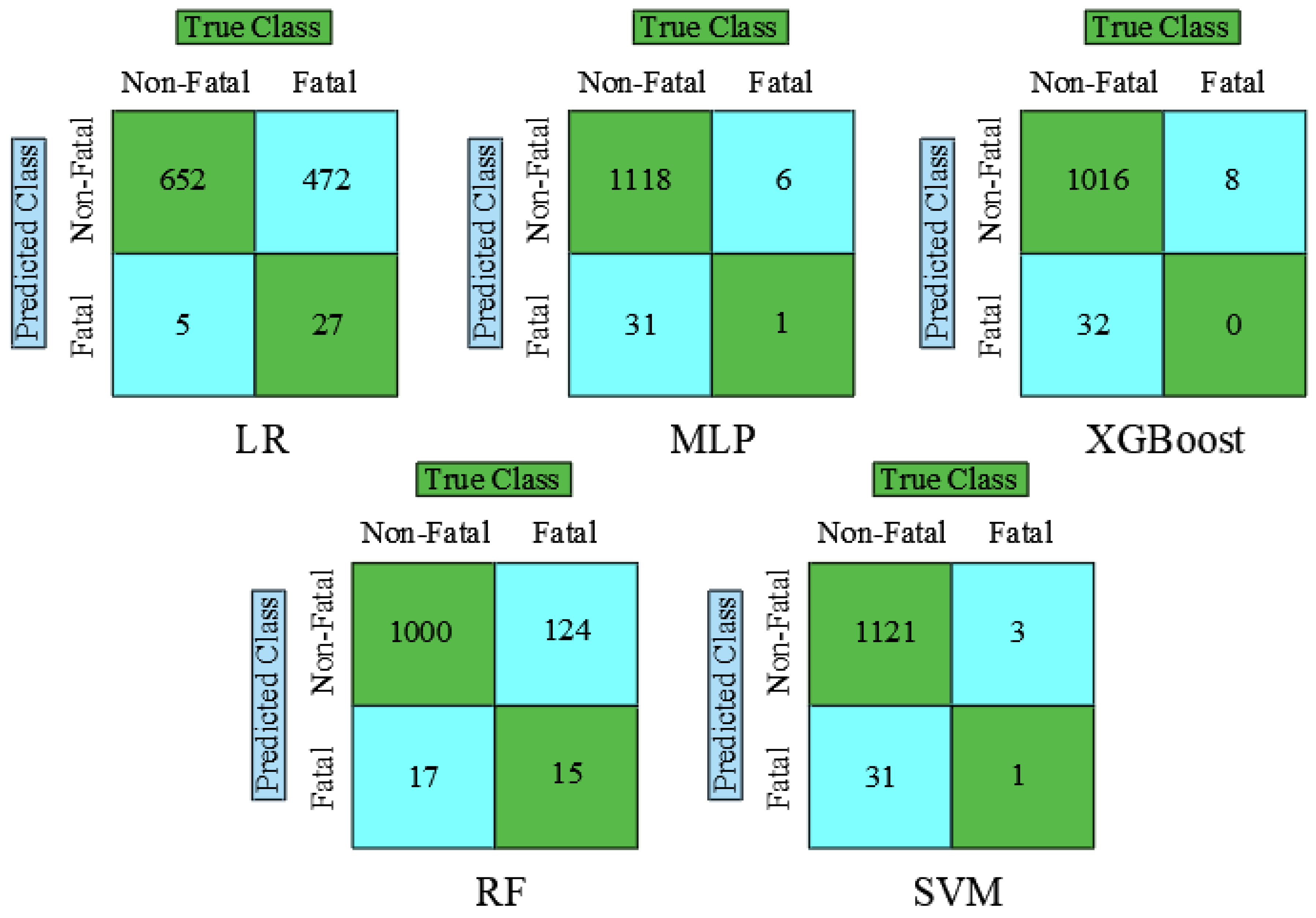

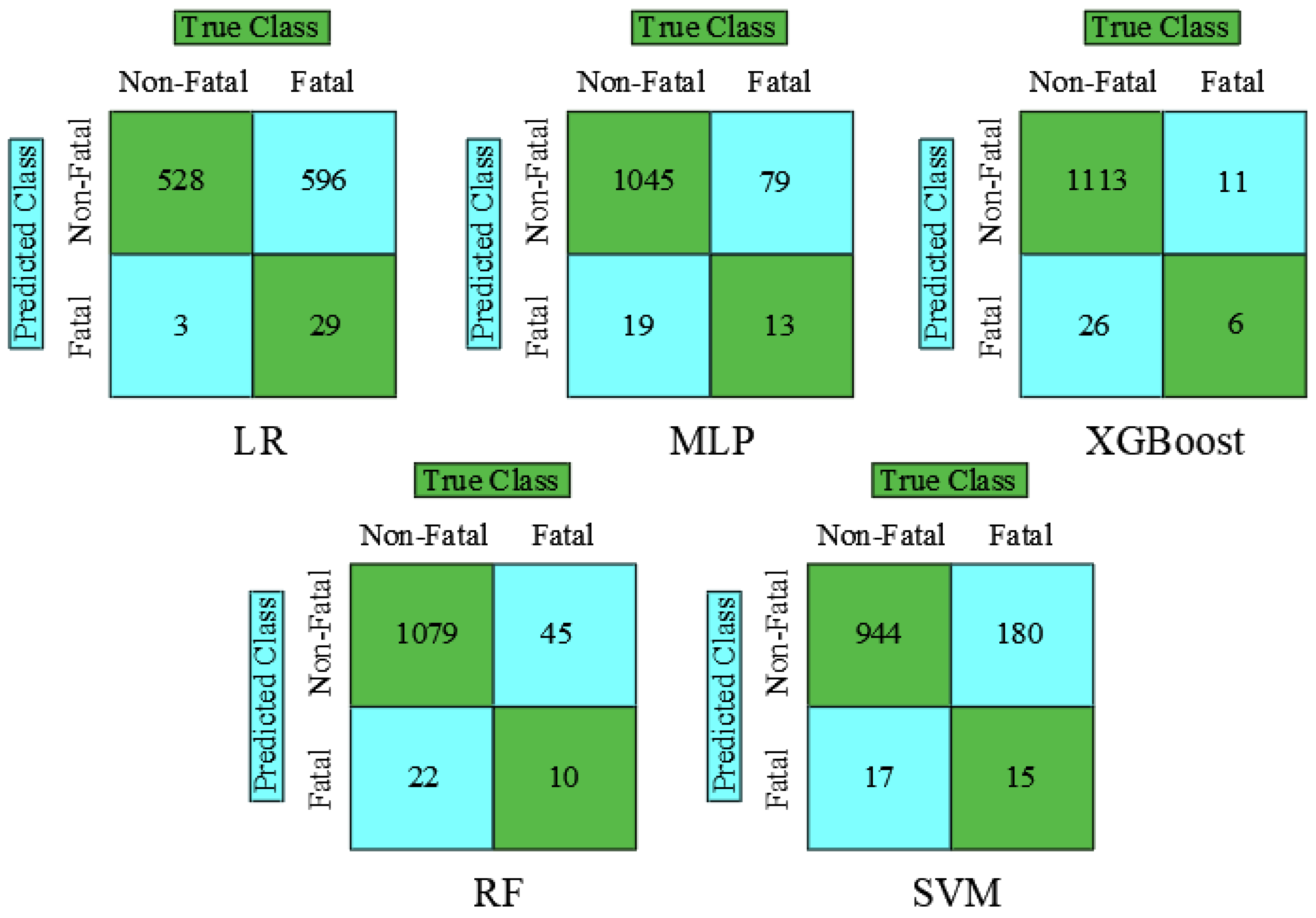

The confusion matrices of different machine learning models were utilized to comparatively evaluate their classification performance. In these matrices, the green cells represent correct classifications (True Positives and True Negatives), while the turquoise cells indicate misclassifications (False Positives and False Negatives). The Logistic Regression (LR) model demonstrated partial success in classifying fatal crashes; however, it produced a high number of False Positives. The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) and XGBoost (XGB) models struggled to correctly identify the fatal crash class and exhibited weak performance for this category. The Random Forest (RF) model achieved relatively more balanced results, whereas the Support Vector Machine (SVM) model showed a moderate level of success across both classes. Consequently, as illustrated in

Figure 3, it is evident that the pronounced imbalance in class distribution adversely affected the overall performance of the models.

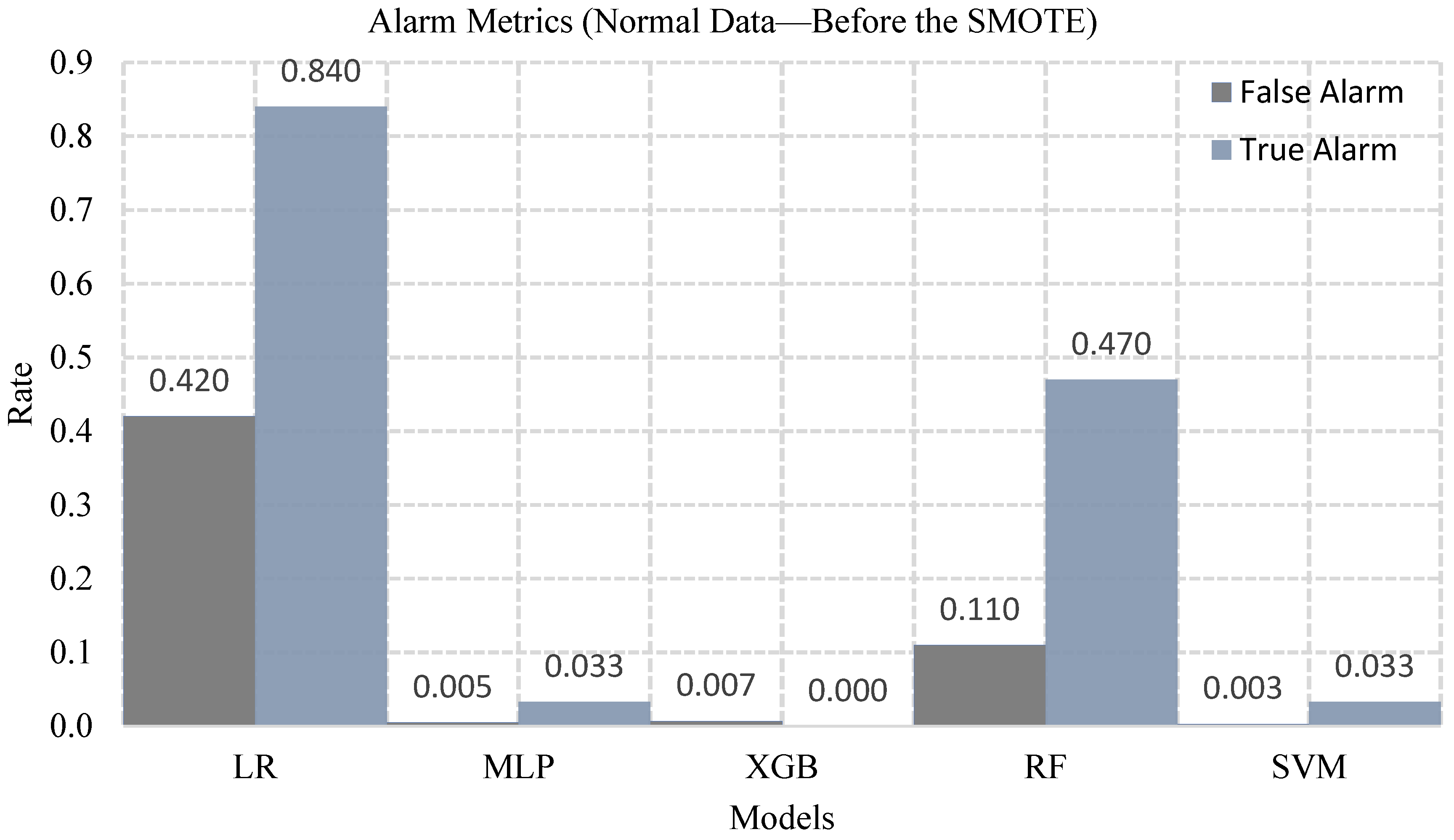

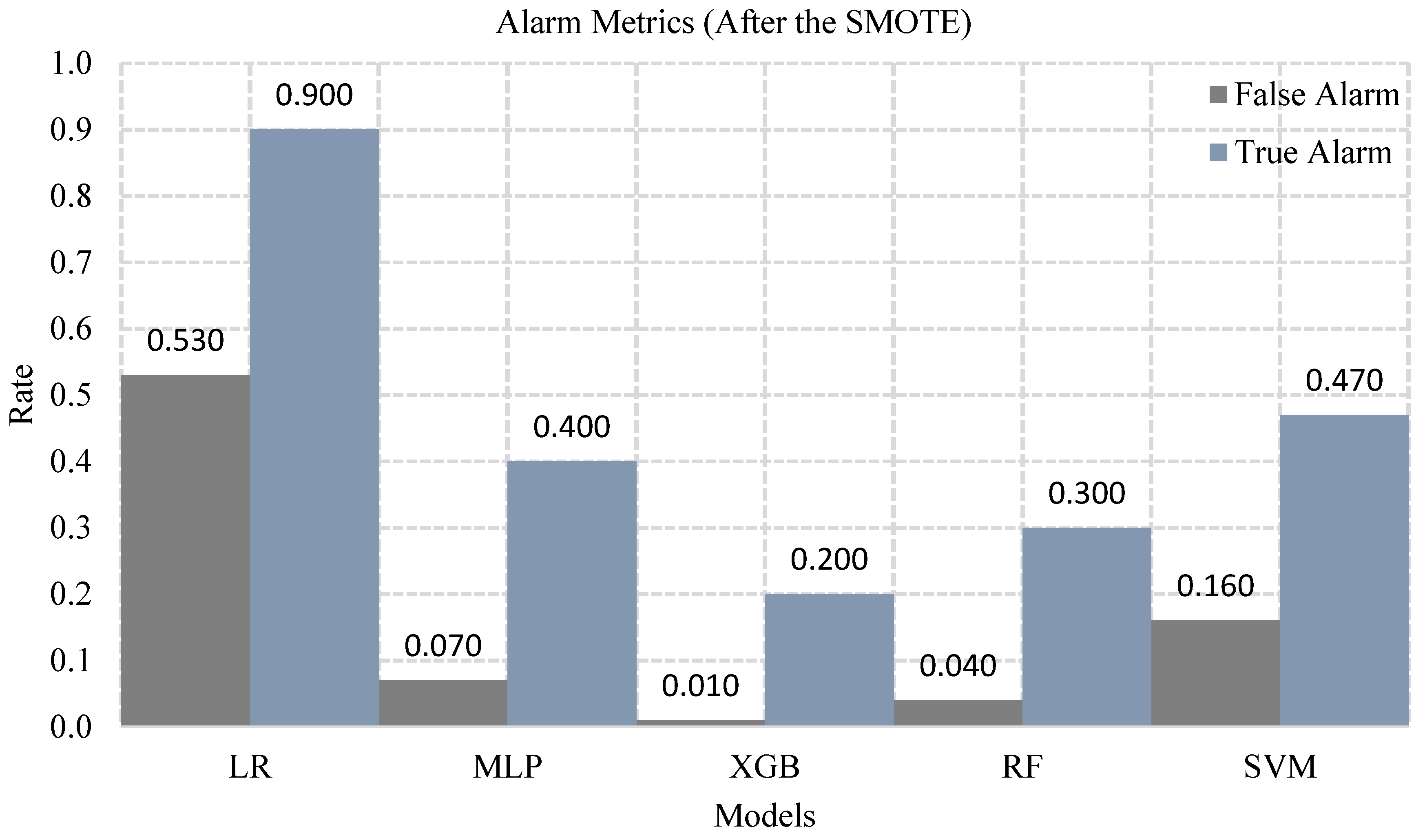

As shown in

Figure 4, the majority of the models developed before applying the SMOTE exhibited low True Alarm rates, while their False Alarm values remained relatively high. This indicates that, due to the imbalanced data structure, the models inadequately detected fatal crashes.

The fatal crash prediction performances of five different machine learning models (LR, SVMs, MLP, RF, and XGB) after the application of SMOTE are presented in

Table 8. The Logistic Regression (LR) model achieved the highest True Alarm rate (TP = 0.90), accurately predicting most fatal crashes; however, its high False Alarm rate (FP = 0.53) indicates that the model predicted a substantial number of False Positives. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) model significantly reduced the False Alarm rate (FP = 0.16) and demonstrated a balanced performance (F1 = 0.52). The Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model achieved a lower FP rate (0.07), but its ability to detect fatal crashes remained limited (TP = 0.40). Although the Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost (XGB) models achieved the lowest False Alarm rates (FP = 0.04 and 0.01, respectively), they demonstrated the weakest performance in capturing fatal crashes (TP = 0.30 and 0.20, respectively).

Figure 5 presents the ROC curve illustrating the models’ performance in distinguishing between fatal and injury crashes. The points on the curve correspond to each model’s True Positive Rate (TPR) and False Positive Rate (FPR) values. The Logistic Regression (LR) model exhibited high sensitivity (TPR = 0.90); however, its high False Positive Rate (FPR = 0.53) resulted in an unbalanced prediction structure. In contrast, the XGBoost (XGB) and Random Forest (RF) models achieved low False Positive Rates (FPR = 0.01 and 0.04, respectively), but missed a large portion of fatal crashes, performing poorly in terms of sensitivity (TPR = 0.20 and 0.30). The SVM and MLP models provided a moderate balance between sensitivity and specificity, yet the overall results indicated that the imbalanced data structure adversely affected the sensitivity–specificity trade-off of the models. These findings demonstrate that balancing the training data using the SMOTE improved model performance by bringing the ROC curves closer to the ideal classification line.

The confusion matrices of the machine learning models used in this study were also evaluated. In these matrices, the rows represent the actual classes (injury and fatal crashes), while the columns show the classes predicted by the models. Correct classifications are indicated with green cells (True Positives and True Negatives), whereas misclassifications are shown with turquoise cells (False Positives and False Negatives). The confusion matrices (

Figure 6) illustrate the performance of the models when trained on the SMOTE-balanced training data and tested on the original (imbalanced) test data. The Logistic Regression (LR) model successfully detected a large number of fatal crashes (TP = 29) but produced many False Alarms (FP = 596). The SVM and MLP models yielded more balanced results; although their False Alarm rates were lower (FP = 180 and 79, respectively), their fatal crash detection rates remained limited (TP = 15 and 13). The Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost (XGB) models achieved the lowest False Alarm rates (FP = 45 and 11, respectively), yet missed a considerable portion of fatal crashes (TP = 10 and 6). These results indicate that, while the SMOTE effectively balances the training data, the imbalance in the test data still poses challenges for accurately predicting fatal crashes.

As shown in

Figure 7, after the application of SMOTE, a significant increase in the True Alarm rates and a considerable decrease in the False Alarm rates were observed across the models. This finding indicates that ensemble-based algorithms such as Random Forest (RF) and XGBoost (XGB) demonstrate more stable and robust classification performance when data balance is achieved.

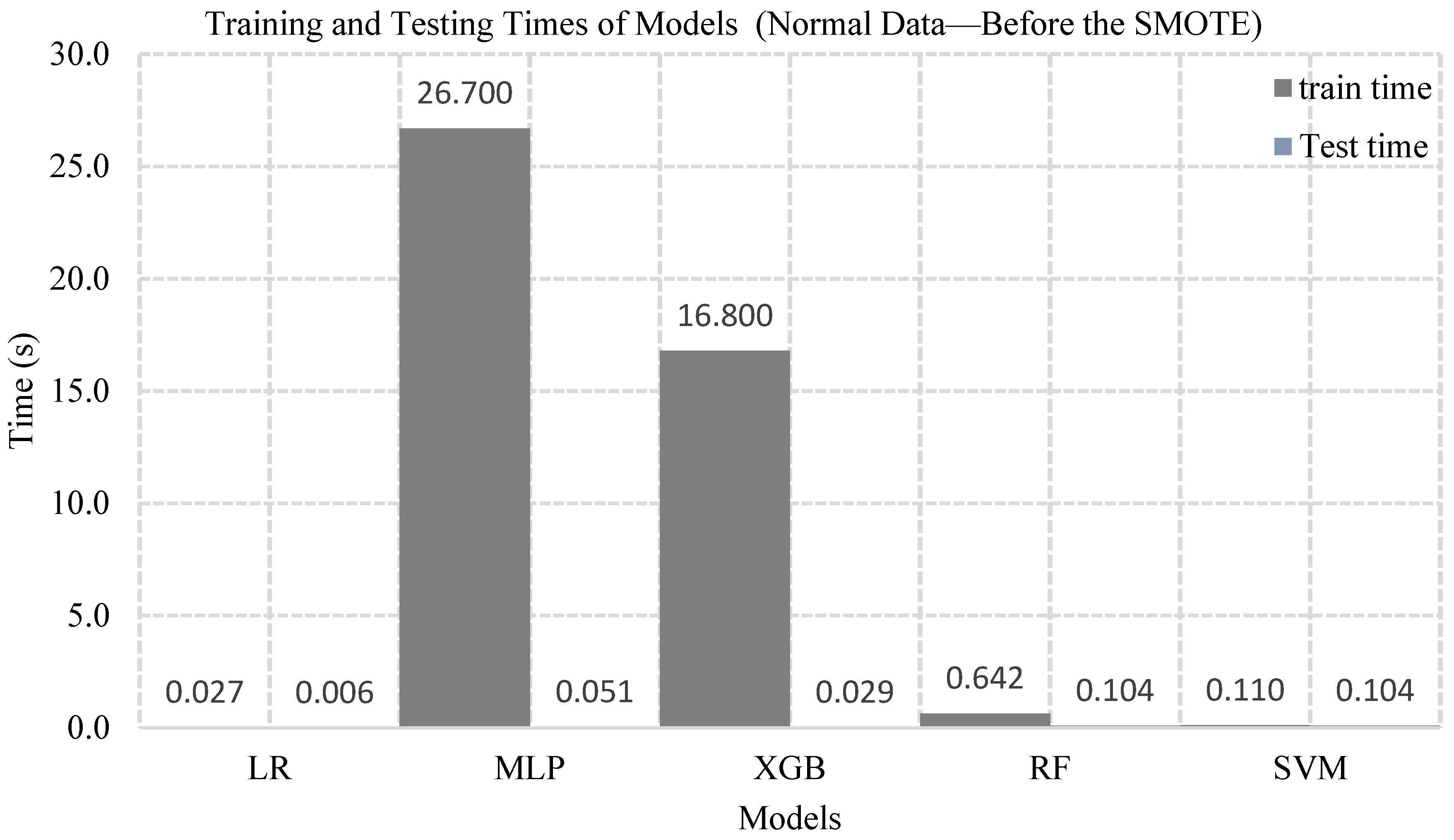

The training and testing times of the machine learning models trained on the imbalanced dataset are compared in

Figure 8. The results show that the Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) model had the highest training time (26.7 s), followed by the XGBoost (XGB) model (16.8 s). In contrast, the Logistic Regression (LR) (0.027 s) and Support Vector Machine (SVM) (0.110 s) models exhibited the shortest training times, indicating a more computationally efficient structure. When evaluating testing times, all models produced results in very short durations, suggesting their suitability for real-time applications. The LR model achieved the fastest testing time (0.006 s), while the RF (0.104 s) and SVM (0.104 s) models demonstrated comparable test performance.

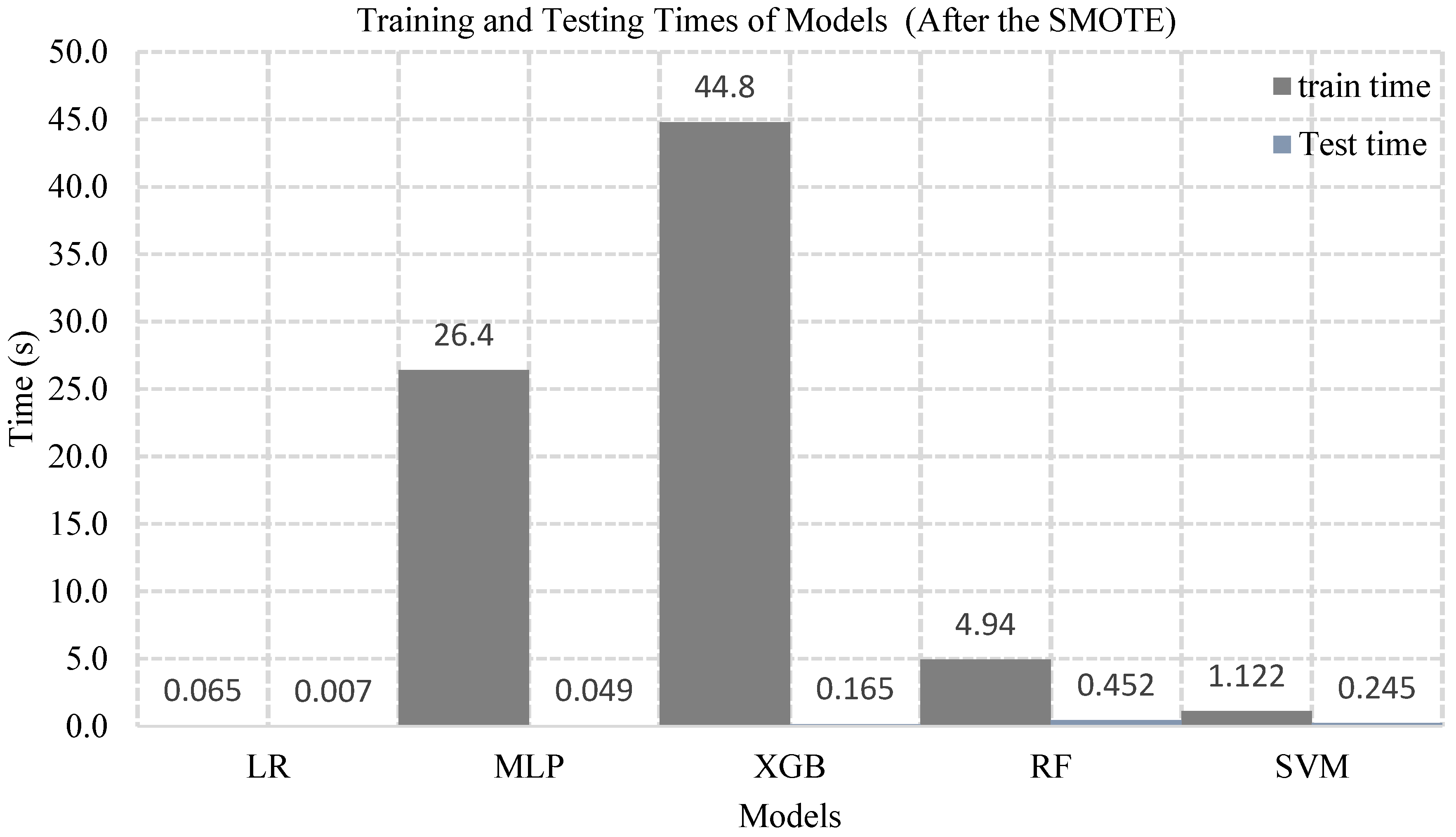

After the implementation of SMOTE, the training and testing times of different machine learning models were further compared. The results indicate that the XGBoost (XGB) model had the longest training time, i.e., 44.8 s, followed by the MLP model, i.e., 26.4 s, and the RF model, i.e., 4.94 s. Conversely, the LR and SVM models showed considerably shorter training durations of 0.065 s and 1.122 s, respectively. Regarding testing times, all models generated results much faster during the testing phase, as shown in

Figure 9, with the Logistic Regression (LR) model achieving the shortest testing time of 0.007 s.

Discussion

LR is a linear classifier and assumes linear separability between classes. However, our dataset consists of features representing road, geometry, traffic characteristic factors, many of which interact nonlinearly. Due to this nonlinear and multidimensional feature space, LR struggles to form effective decision boundaries. Furthermore, LR tends to be sensitive to class imbalance, causing it to bias predictions toward the majority class. These limitations collectively explain its lower F1-score, despite the use of class-weight balancing.

MLP is capable of modelling nonlinear relationships; however, its performance is highly dependent on the density and quality of training samples. In imbalanced datasets with very few fatal crash samples, the model risks overfitting to oversampled minority data or failing to generalize during testing. Additionally, MLP requires larger datasets to leverage its deep architecture effectively. These factors explain why MLP provided moderate improvements but still struggled in capturing minority-class patterns.

RF is more flexible than LR but relies on bootstrap sampling, which tends to reproduce the majority class extensively in each tree when the imbalance is severe. As a result, many trees do not learn minority-class (fatal crash) patterns effectively. In addition, RF may overfit noisy categorical features, producing lower sensitivity (True Alarm rate) for the test set. Although RF performs better after the SMOTE, it still underperforms when compared with XGBoost due to its lack of gradient-based optimization.

An SVM with an RBF kernel is effective for nonlinear separation, but it is sensitive to imbalanced class distributions, as the optimization process focuses on maximizing the margin across all samples. With limited fatal crash samples, the SVM tends to place decision boundaries closer to the minority class, reducing its recall. Although the SVM produced more balanced outcomes after the SMOTE, it still underperformed relative to tree-based ensemble models due to limited flexibility in handling high-dimensional categorical–numerical mixed feature spaces.

XGBoost achieved the highest performance among all models. This is expected due to its following abilities:

The optimization of classification errors through gradient boosting;

The incorporation of regularization to prevent overfitting;

The effective learning of complex nonlinear interactions;

The better management of minority-class patterns even when imbalance persists in the test set.

These characteristics make XGBoost more robust for datasets with heterogeneous variables and skewed class distributions. This explains its superior F1-score and significantly lower False Alarm rate.

The advantages and disadvantages of LR, RF, MLP, SVMs, and XGBoost with respect to the dataset characteristics and observed performance metrics are given in

Table 9.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

In this study, the performances of various machine learning algorithms (LR, SVMs, MLP, RF, and XGB) in classifying traffic crash severity were compared. According to the obtained results, the XGB model achieved the highest overall performance with an F1-score of 0.61. This model also exhibited the lowest False Alarm rate (0.01), maintaining a high level of classification accuracy. The RF and MLP models showed comparable performances with F1-scores of 0.59 and 0.58, respectively, indicating that tree-based methods and artificial neural networks are effective in capturing complex data structures. In contrast, the SVM and LR models achieved relatively lower performance levels (0.52 and 0.36), reflecting their limited success. These findings demonstrate that, in terms of classification accuracy, the XGB and RF models represent the most powerful approaches for predicting crash severity.

Based on the study results, it is recommended that future crash risk modelling studies should prioritize the use of XGB and other ensemble learning methods. Moreover, integrating boosting-based approaches with other advanced algorithms within hybrid modelling frameworks and validating these models using large-scale and diverse datasets that include different regions and traffic conditions will be essential for enhancing the generalizability of the proposed methods.

The success of machine learning models largely depends on the quality of the data used and the adequacy of the variables included in the model. When data quality is low, models may learn incorrect patterns and exhibit limited generalization capability. In particular, datasets with missing, erroneous, or imbalanced distributions can negatively affect classification performance, leading to biased results. Therefore, data preprocessing steps (e.g., data cleaning, balancing, normalization, etc.) play a critical role in improving model performance.

Furthermore, model complexity and parameter selection are key factors that directly influence classification success. Improper parameter selection may cause overfitting, where the model performs well on training data but poorly on test data. Conversely, it may also prevent the model from fully capturing complex relationships within the data. In this context, hyperparameter optimization is of great importance, as it enhances the model’s learning capacity while maintaining generalizability. In this study, balancing the dataset using the SMOTE and optimizing the model hyperparameters were decisive factors in improving the obtained results. Therefore, in traffic crash classification studies, enhancing data quality, selecting appropriate parameters, and maintaining an optimal balance of model complexity are among the fundamental elements that directly influence classification performance.

For future research, the use of time-series analysis is recommended for predicting traffic crashes. By incorporating the temporal dimension into the model, seasonal trends, time-of-day risk variations, and long-term patterns can be analyzed to better understand the temporal dynamics of crashes. This approach would provide valuable insights, particularly in identifying whether fatal crashes tend to increase during specific periods. Additionally, utilizing Geographical Information Systems (GISs) for the detailed analysis of the spatial distribution of crashes would significantly contribute to research efforts in this field. GIS-based analyses can facilitate the mapping of high-risk areas, enabling decision makers to plan traffic safety measures with a spatial focus. In this regard, combining time-series methods with GIS-based spatial analyses will allow the development of a more comprehensive, dynamic, and predictive modelling framework for traffic safety research.