Abstract

Assessing grip strength is fundamental to ergonomics, medicine, sports, and rehabilitation, as it reflects the functional capabilities of the upper limb. The main goal of this paper is to design and create a device that measures hand force to help keep workers’ physical workload safe and sustainable in factories. The paper looks at the long-term health and safety of employees, explaining what sensors and methods can be used to measure hand force and pressure. It describes a new device for measuring hand grip, which was tested and adjusted in real factory conditions. This device could be used to measure force when using tools and to check for risks of heavy physical strain at work. The system helps find possible injury risks in any type of workplace, especially where people need to grip with their hands many times. It checks if workers use too much force, especially in jobs with repeated tasks where the same hand movement happens again and again. The text suggests that it is important to track hand forces during any job that repeats more than 40 times in a shift, no matter how long the shift is. The system is made up of a smart glove and software for analysis. Its purpose is to estimate how much force is needed to complete a task safely, not the maximum force a person can make. The goal is to measure the required force for the job so that workers’ workload remains safe and healthy over the long term.

1. Introduction

Hand force measurement is important across numerous fields. Prior to the early 2000s, hand force measurement technology was severely limited [1]. Researchers mostly used special types of dynamometers to study hand grip and hand movement forces [2,3,4,5,6,7]. However, these tools were impractical for direct application in factory environments because workers require freedom of movement and tool manipulation. With the arrival of very thin tactile sensors, new possibilities appeared [8,9,10,11]. Today, measuring hand force is common because it shows how the hand and fingers work, for example, in medical diagnostics. Many studies have shown that these measurements are useful and accurate in applied research, which also inspired this work [12,13,14,15,16,17]. The collected data enables improved workplace safety, the prevention of health problems, and enhanced work comfort. This helps maintain a sustainable physical workload for employees. In modern industry, hand force analysis is also important for understanding tasks in automation systems.

Measuring hand forces is needed in real work situations because musculoskeletal injuries are happening more often. These injuries are caused by unsuitable and repeated handling of loads in bad working conditions [18]. Work tasks can be partly evaluated, but a complete system for collecting data and assessing the risks of different hand forces under different work conditions is still missing. Currently, there is no standard method for measuring hand forces. Also, the force limits mentioned in some scientific studies depend a lot on how the hand forces are measured [19].

The results from reference [20] show that the smart glove can be used for maintenance and repair work. Sensors made from graphene can quickly sense pressure and quickly return to normal. Graphene’s strength, which is very important, worked well during the tests. This study looked at how much data the glove could collect and how quickly, how it reacts to events, and how reliable it is [21]. In the last ten years, smart gloves [22] have become popular and useful wearable devices, and they are a good option for checking comfort during light mobility. These gloves have sensors that record hand and finger movement, plus the force from the fingertips [23]. Use of the glove system in industry showed that it is a helpful tool for measuring and reducing hand forces at work. By determining when too much force is used and helping improve ergonomics, the system reduced workers’ physical strain and made the workplace more comfortable.

In recent times, the development of smart glove technologies has been seen as an intermediate step in the next generation of less intrusive methods of monitoring bodily functions through sensor technology. The introduction of ultra-flexible microsensor technologies (see references [24,25]) offers the future possibility of developing a new generation of devices to measure force and stress on the body that will no longer be located on a glove; these will be directly attached to the skin through adhesive mounted microsensors rather than through wearing the glove. An example of this new technology is that of a non-contact wearable electronic device created by Shin et al. [24] that allows for the measurement of epidermal molecular flux (the flow of molecules from the epidermis) with skin-adhered electronics attached via adhesive, rather than through physical contact with the device. This marks a major milestone in the evolution of the future of the continuous monitoring of physiological activity in the workplace, as this device can be used in various working environments and without the wearer needing to wear the device on their hand. Similarly, soft skin-bonded wireless electronic devices using electrogoniometry technology have now been developed [25] to allow for continuous measurements of the movement and bending of the joints in the fingers and wrists of the human body while remaining attached to the skin with a high degree of measurement fidelity. (Millions of people are currently working from home, usually from non-traditional ‘job’ spaces.) Therefore, the smart glove model presented in this paper forms a template for the potential integration of these ultra-flexible microsensor technologies. The sensor positioning protocols and force measurement algorithms developed in this work may be adapted to allow for the future development of adhesive or finger-worn sensor systems.

2. Materials and Methods

These sensors are flexible and can be directly integrated into the hand or glove, which makes them highly effective for monitoring hand and finger forces during different activities, such as sports, rehabilitation, orthopedics, or work [26,27,28,29,30].

There are many devices made to measure hand-generated forces. Examples include the E-RGO GLOVE [31], the NEX-T7-GS24 T7 Glove Pressure Mapping System from NexGen Ergonomics, Inc. from Pointe-Claire, QC, Canada [32], the ErgoGLOVE as part of the ErgoPAKTM system from Hoggan Health Industries [33], the Grip System from Tekscan, Inc. (Norwood, MA, USA) [34], and others. Their features were compared and analyzed (see Table 1), and then we identified the following requirements for our device:

Table 1.

Comparison of hand force measurement systems that are sold on the market [1].

- No cables and use of wireless communication;

- Protection of sensors from damage or mechanical impacts;

- Placement of sensors on the glove to prevent measurement mistakes;

- Sensor positions should match the hand grips most often used at work;

- Online connection with a tablet, PC, or computer.

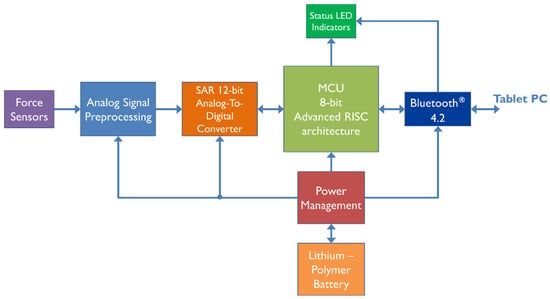

Figure 1 illustrates the design concept of the proposed measurement system. The core idea was to integrate sensors into a flexible, multifunctional glove to protect them from mechanical damage and to capture reliable measurement data. The analog circuitry first processes signals from the sensors, converts them into digital form, and then wirelessly transmits the data to the computer (see Figure 2). The control module can be positioned on the wrist or forearm of the participant. Data are displayed and stored using the in-house CERAA Glove App.

Figure 1.

Concept of the device.

Figure 2.

The topology of the device.

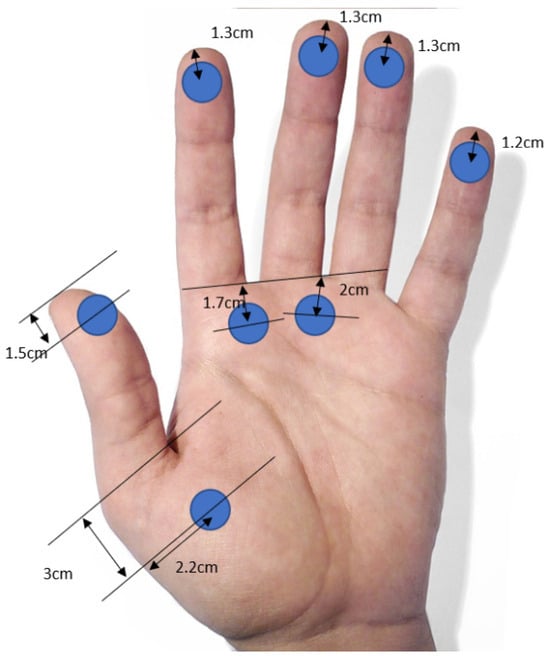

The type of sensor was selected based on the areas where the greatest force is expected. At this stage of the device design, a compromise was necessary between sensor positioning and the kind of performed activity [35].

Several aspects affected the choice of the glove, including movement restrictions, potential measurement inaccuracies, and risk of sensor damage. Material research revealed that cotton is unsuitable, as it redistributes the acting forces within the glove and thereby reduces the transmission of forces between the hand and the tool.

In contrast, polyvinyl chloride materials cause very little redistribution of forces, which makes them more appropriate for precise force measurement applications [36]. However, antivibration gloves are not suitable either, as reported in [37], since they can decrease overall grip strength by more than 29%, depending on both the manufacturer and the tool’s dimensions. Moreover, the thickness of the glove material contributes to several adverse effects and artifacts detected during hand force measurement processes [38].

Force-sensing resistors (FSRs) were selected as the sensing elements because they can be positioned directly in the areas where maximum grip forces occur. The key selection criteria included flexibility, durability, and a suitable force measurement range. Consequently, the FSR151 model from IEE, Inc. (Van Nuys, CA, USA) was chosen. Its main specifications are as follows [39]:

- Active area diameter: 12 mm;

- Activation resistance range: 1 MΩ > RL > 2 kΩ;

- Applied pressure: 0.5 N/cm2–100 N/cm2;

- Adhesive layer.

Additional testing was carried out on Interlink Electronics Inc.’s FSR400 (Camarillo, CA, USA), which demonstrated higher mechanical resistance compared to the FSR402 model.

During practical verification, a significant issue was observed—a measurement error occurring when the applied force was not distributed uniformly across the sensor surface. These inconsistencies prevented accurate force evaluation under industrial conditions, which represented the primary intended application of the glove. To overcome this limitation, specially designed pressure caps were developed and mounted on both sides of the sensor (see Figure 3). Their function is to ensure an even distribution of the applied force across the sensitive area.

Figure 3.

Schematic of the sensor (black) and the pressure caps (blue).

The design of the pressure caps is a unique and inventive approach to the respective problem. The authors have submitted a patent application (no. 10) with all technical specifications of the invention. The application is currently in the patent-pending phase of evaluation. This revealed the potential need to slightly modify the illustrated sketch of the pressure caps. Certain specifications, including geometric dimensions, material type, and hardness, are included among the pending patent specifications.

The pressure caps (or distributors) are made through a 3D-printing process that uses laser sintering. During production, powdered material is incrementally applied in layers with an accuracy of ±0.3%. A computer-controlled CO2 laser selectively melts powder particles after each layer is deposited. The laser will heat the material to a temperature above its melting point and adjacent powder particles will coalesce together to form a cap with the desired geometry and dimensions.

The initial version of the prototype included 14 connected sensors. After testing, we realized that not all sensors were necessary for the targeted grip types. Therefore, their number was reduced to 8, forming a sensor array capable of capturing forces associated with various grip patterns, such as pinch, power, hook, and precision grips. Figure 4 illustrates the placement of a single sensor.

Figure 4.

Positioning of individual sensors.

As described earlier, the sensors are mounted on the glove as shown in Figure 4. Each sensor must be powered by a voltage source, which in this setup is a 3.3 V output from the BM78 Bluetooth module [40]. One terminal of the FSR sensor is connected to this voltage source, while the other terminal provides a signal that reflects its resistance variations. The communication between the sensors and the control unit, located on the wrist, is achieved using cables integrated into the glove. The second terminal is also connected to the input of an inverting amplifier that converts the current output from the sensor into a voltage signal. The operating principle of the FSR sensor lies in its resistance, which decreases proportionally to the applied force, resulting in measurable voltage changes.

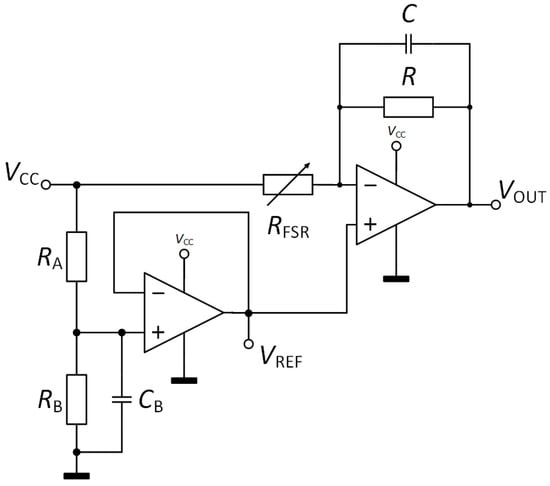

The analog signal is pre-processed through several stages within the electronic control unit mounted on the wrist. A voltage follower is employed for impedance-matching of the reference voltage source. The output of this stage is routed to the non-inverting input of the inverting amplifier. The amplifier measures current from the sensor, and by varying the feedback resistor, the system allows for the fine-tuning of sensor sensitivity to accommodate different load conditions. The same signal processing concept is applied independently to each sensor. The overall analog processing circuit is depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Analog signal processing part.

The circuit shown in Figure 5 has an output voltage that can be expressed as

VOUT = VREF ∙ (1 + R/RFSR) − VCC ∙ (R/RFSR).

Then, we can rewrite the previous equation in the following form:

VOUT = VREF + (VREF − VCC) ∙ (R/RFSR),

In this case, the VREF is equal to

and we obtain the following for output voltage:

VREF = VCC ∙ RB/(RA + RB) = VCC − 1,

VOUT = VREF − R/RFSR,

Using the analog signal processing, it is possible to find the pressure sensor resistance (RFSR) by translating the output voltage (VOUT) into a digital amount by knowing the reference voltage (VREF) and resistor value (R). The signal digitization is executed using two 12-bit analog-to-digital converters that use the successive approximation mechanism. More specifically, the conversion process uses two 12-bit ADCs with the successive approximation register (SAR) technology—MCP3208 [41]. With the 12-bit resolution, the quantization step for converting VOUT into its digital form can be calculated by

where VCC acts as a reference voltage of the A/D converter and equals 3.3 V.

q = VCC/212 ≈ 806 µV,

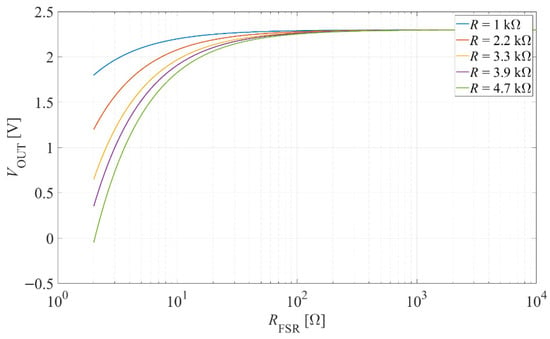

Using the circuit shown in Figure 5, we can create the theoretical characteristic showing the dependence of the VOUT on RFSR based on the information listed in the FSR sensor datasheet, ranging from approx. 2 kΩ to 10 MΩ in the case where the sensor is not activated. This characteristic is shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The dependence of the VOUT on RFSR.

Figure 6 demonstrates that the output voltage range can be adjusted by selecting an appropriate RFSR value, which determines the circuit’s sensitivity to force variations. Therefore, the value of the feedback resistor has a direct impact on the circuit’s performance. A smaller resistor value results in lower sensitivity to changes in the applied force. Conversely, if the RFSR value is too large, the operational amplifier may become saturated when higher forces are applied to the sensor.

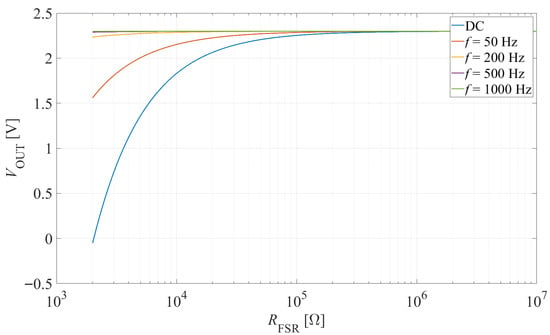

When a capacitor (C) is added to the feedback branch of the analog processing circuit, it functions as a low-pass filter that suppresses high-frequency noise caused by hand vibrations during tool handling. Consequently, based on the condition expressed in Equations (3) and (4), the equation can be reformulated as follows:

VOUT = VREF − (R/RFSR) ∙ [1/(1 + jωRC)].

To ensure maximal circuit sensitivity, assume R = 4.7 kΩ. To remove output voltage noise caused by unwanted vibrations during activity, we set the cut-off frequency of the filter to approx. 34 Hz by choosing of value of C = 1 µF, which follows from

fC = 1/(2πRC).

After these assumptions, we created the figure showing the changes in VOUT dependency on RFSR for different frequencies of vibrations. So, Figure 7 shows that for frequencies close to the DC, the output voltage characteristic is nearly the same as the circuit without a feedback capacitor. The filtering properties of the unwanted high-frequency vibrations are visible as a stable value of the VOUT in the whole displayed range of RFSR.

Figure 7.

The dependence of the VOUT on RFSR for different frequencies of vibrations.

Each converter includes eight input channels that receive signals from the amplifiers, allowing for the digitization of up to eight channels at once. The signals are sampled at a rate of 250 Hz, after which the data are transmitted via the SPI interface to the ATmega328P 8-bit microcontroller (MCU) Chandler, AZ, USA [42].

The MCU is powered by a 3.3 V supply derived from the Bluetooth module. Communication between the MCU and the Bluetooth module is carried out through a UART serial interface configured with the following parameters:

- Baud Rate = 38,400;

- Stop Bits = 1;

- Data Bits = 8;

- Parity = none.

The Bluetooth module connects to the PC over a virtual serial port. This is powered by a single-cell lithium–6polymer battery with a nominal voltage of 4.2 V and a capacity of 750 mAh. As mentioned previously, the module integrates a voltage stabilizer that outputs 3.3 V, providing power to nearly all functional components of the device. In addition, several built-in LEDs indicate system status, including UART communication activity, data transmission, and operational state.

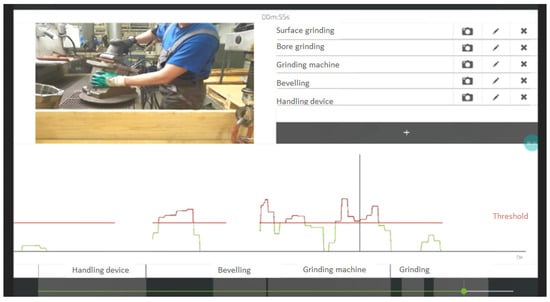

2.1. CERAA Glove App

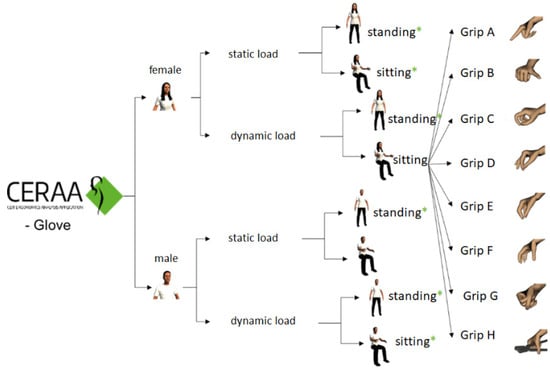

The graphical user interface (GUI) was developed and created to allow for the evaluation of recorded data. The interface of the CERAA Glove App can be seen in Figure 8. A force measurement is synchronized with a video recording (which is recorded using a tablet) by the smart glove. During the evaluation, the video is watched in the top-left window. Individual video sequences are selected from the upper-right corner. Next, the input evaluation parameters related to the specific worker and hand grip must be chosen. The decision tree for this is illustrated in Figure 9.

Figure 8.

CERAA glove app.

Figure 9.

Decision tree for selecting the analysis input parameters.

After all input data is entered, a graph of measured forces is displayed in the lower half of the screen. The maximal recommended force for the selected activity and hand grip corresponds to the horizontal red line. The values below the threshold are shown in green, and threshold limit violations are shown in red. Any specific actions that were found to exceed the recommended maximum force can be identified by the user in the video recording.

2.2. Adaptability and Inclusivity Considerations

The developed smart glove system addresses user variability through several design features. The glove comes in four standard sizes (small, medium, large, extra-large) based on measurements of the adult population’s hands. The design of the FSR sensors provides flexibility for placement in contact areas with the most force (as illustrated in Figure 4) and allows them to measure consistently, although there may be slight variability between fingers and palms within one of the 4 glove sizes. The glove can be used wirelessly by connecting through Bluetooth to a control module that is attached to the wrist instead of the palm. Thus, the glove design has minimal impact on the way that individuals move their hands, and those with different levels of grip strength will be able to use the glove comfortably. Individuals who suffer from limited range of motion in the wrist or who have decreased dexterity in their hands will still find that the FSR sensors are able to be utilized in the same basic locations as they would use them. Nevertheless, the application of the current prototype does not meet all of the requirements for universal accessibility. The shape of the glove may not fit the needs of individuals with severe hand deformities or those who would require custom orthotic devices. Future iterations of this prototype should include designs to attach sensors in different ways to customize them to fit the individual user’s hand anatomy, and potentially allow for integration with existing assistive devices. Finally, the current evaluation algorithm that has been developed uses population data-based threshold values (which have been segmented by gender and grip type), and will likely require the user to calibrate individually depending on the particular condition affecting strength or coordination in their muscles.

3. Results

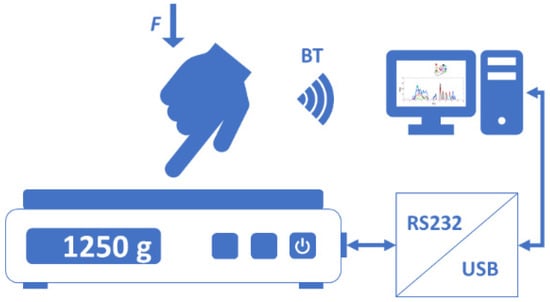

During calibration, the handgrip was simulated, as shown in Figure 10. As a reference measuring system, a laboratory weight scale, which provided a digital output, was employed. The synchronized collection of data was enabled by this scale in combination with the device control unit.

Figure 10.

Arrangement for calibration and verification of the system [1].

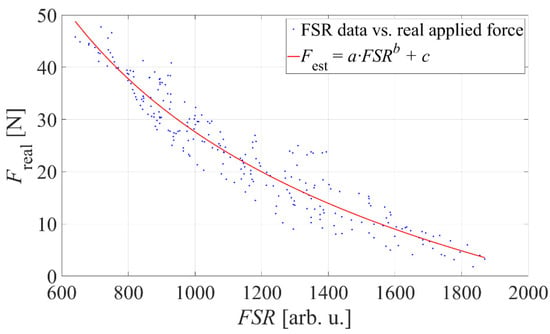

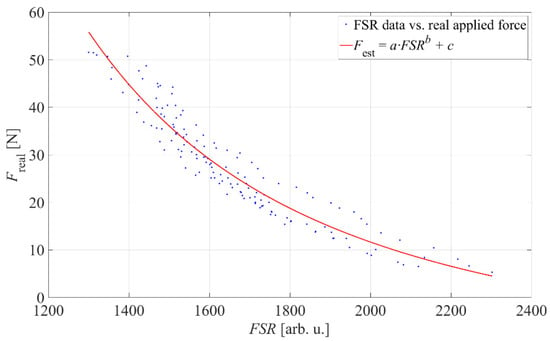

The response of one sensor was monitored after a perpendicular force was applied to it; this behavior is shown in Figure 11. The test started with an approximate force of 5 N and was concluded near 50 N.

Figure 11.

Correlation between the control unit’s raw sensor reading (FSR) and the actual measured force (Freal).

To determine the correlation between the force applied to the sensor and the reference from the weight scale, a power function was utilized for data extrapolation:

Fest = aFSRb + c,

Here, Fest denotes the estimated force, while a, b, and c are the coefficients used for fitting the data. FSR is the raw output value from the control unit. Since these coefficients can change based on testing conditions, the system should be recalibrated when the monitored activity changes to ensure greater accuracy. Alternatively, using specific sensor caps is recommended to achieve a more uniform force distribution over the sensor’s surface.

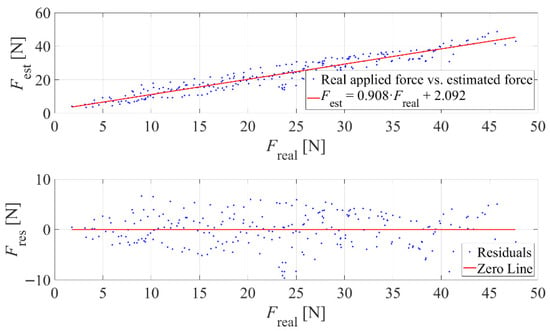

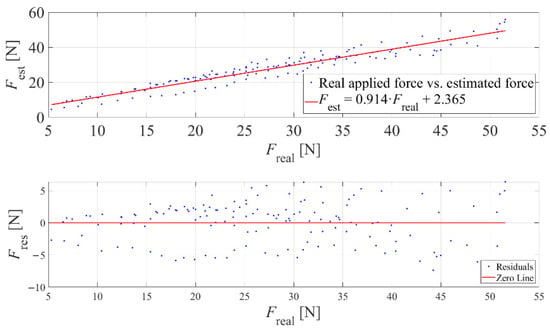

The results of the calibration were subsequently evaluated (as per Figure 11) to check how well the model matched the actual force measurements. Figure 12 compares the true applied force (Freal) measured by the reference scale with the estimated sensor force (Fest). After this data set was modeled, an inherent measurement error of approximately ±5N was observed across the full measurement range.

Figure 12.

Comparison of real force (Freal) against estimated force (Fest).

This calibration process was concluded by producing an equation. This equation describes how the sensor responds when a perpendicular force is applied across its entire surface.

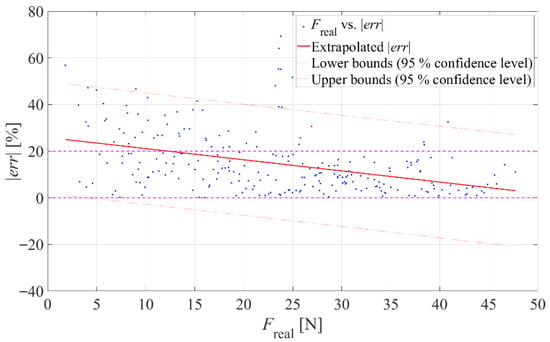

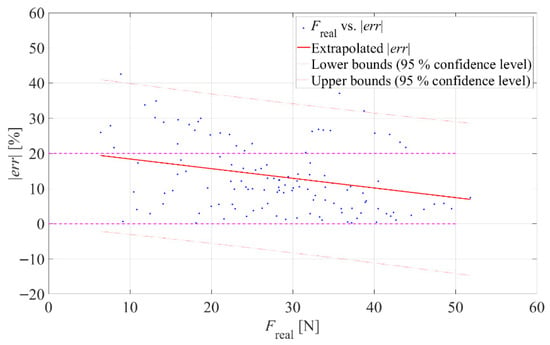

However, when workers perform actual tasks, some sensor areas may not be fully activated because of how a tool is held. Because of this, measurement errors can be expected, as is illustrated in Figure 13.

Figure 13.

Error analysis for sensor measurements under non-perpendicular force application.

The accuracy of the force estimation is significantly influenced by the actual force being applied. When the real force is increased, the measurement error decreases, tending to fall below 20%.

Therefore, more precise measurements are obtained when higher forces are used. This outcome is a desired feature because it matches the typical grip forces employed in industrial settings (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Effect of using pressure caps: the relationship between the raw sensor reading (FSR) and the actual applied force (Freal).

Figure 15 illustrates a reduction in force variation throughout the whole measurement range, in contrast to Figure 12, which displays the force residuals derived from the measurement without caps. When comparing the force residuals to the measurement without pressure caps, the range is almost half, from −2.5 N to 2.5 N.

Figure 15.

Pressure caps—real force vs. estimated force.

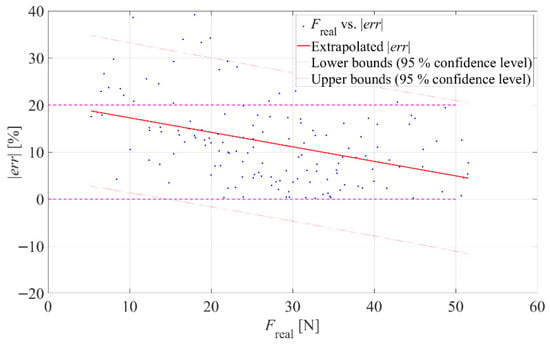

The measurements from the glove sensors used for measuring error, as shown in Figure 16, behave similarly. There is a considerable decrease in the measurement error for small forces when they are compared to no pressure caps, which again suggests that the glove can be used for decreasing measurement errors, even when assessing small forces.

Figure 16.

Pressure caps: inaccuracy in measuring force applied perpendicularly to the sensor.

Pressure caps improved accuracy for forces applied non-perpendicularly to the sensor by enabling the uniform application of forces (Figure 17). In the case of low forces, the upper confidence bound reduces from 50% to 40%.

Figure 17.

Error observed when a non-perpendicular force acts on the sensor while pressure caps are in place.

3.1. Evaluation of Performance in a Practical Work Simulation

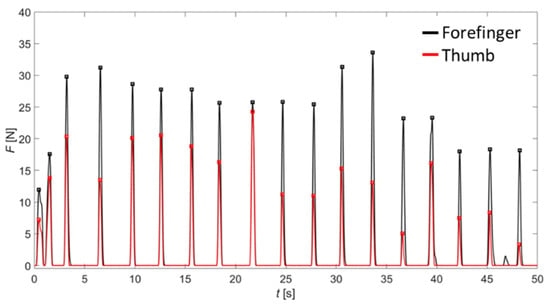

The participant was a 34-year-old right-handed male with a height of 176 cm. The simulated task involved video-recorded electronic assembly of a vehicle front light. The worker’s task was to connect an RJ-45 or USB-A connector to the corresponding socket in a repetitive way. To simulate the activity, the USB-A connector and the USB charger were used (see Figure 18). The measurement time was 50 s.

Figure 18.

Example of a work activity involving a pinch-style hand grip.

The selected task requires only a two-finger operation—the index finger and thumb—referred to a pinch grip, which also requires two fingers to operate the thumb without contact from the palm [43]. This grip type is also applicable in an industrial setting. In Figure 8, a worker can be seen wearing the measurement glove; the sensors are protected by an additional glove placed over the measurement glove to prevent mechanical damage.

Following data collection, the data were post-processed offline in the MATLAB R2023a. In advance, the digital FIR low-pass filter was used to smooth the data. The corner frequency was 10 Hz. The obtained data is shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19.

Plot of forces measured throughout the duration of the task.

During the analysis, the frequency of the workload activity could be detected; thus, we applied a function for the determination of local maxima. The algorithm only detected the relevant local maxima. The observed peaks are shown as square marks in Figure 19.

Based on the measured data, our algorithm was able to find 18 local maxima. Knowing the number of local maxima (n = 18) and the duration of the measurement (t = 50 s), we calculated the frequency of the workload-specific movements (pinch grips). The result was f = 21.6 movements per minute. Working at this frequency, the worker would perform 1296 movements, which resembles repetitive and monotonic activity where a part of the hand is subjected to a considerable load. Through observing this worker over time, we could investigate the long-term impact of this repetitive workload on his health. Therefore, the present device has significant potential for studying the local muscle load on a hand.

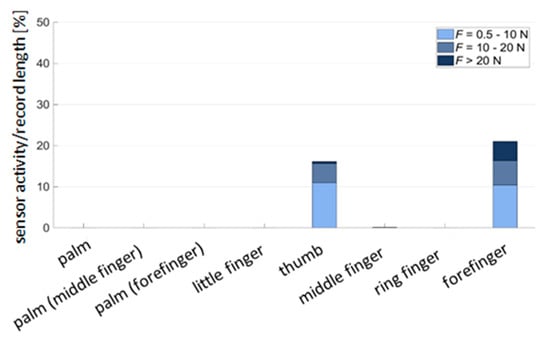

Figure 20 provides a visual representation of the proportion of single-sensor activity integrated over the entire period of recording, shown in seconds. The force intervals are distinguished using different colors. We can see that the force periods exerted by the tips of the fingers are not equal. It is clear from Figure 20 that the finger is able to exert the highest peaks in force (F > 20 N). It was determined that the imbalance in force was a function of how the subject was approaching the work task. In the remainder of this section, we attempt to perform measurements with other subjects to evaluate and study the behavior of these subjects during their work. Finally, considering this additional specific analysis, we will have the opportunity to expose related variations and hopefully counteract some of the muscular issues associated with these work tasks.

Figure 20.

The duration of a single sensor’s activity compared to the total recording time.

3.2. Applying the Test Under Real-World Manufacturing Conditions

At present, the CERAA glove system is currently undergoing rigorous testing across many different work activities in Slovakia and the Czech Republic. Testing has been conducted in many different companies, which include the following:

- Nemak Slovakia s.r.o.

- Continental Matador Rubber s.r.o.

- PPS s.r.o.

- Schaeffler Kysuce, spol. s r.o.

- Embraco Slovakia, s.r.o.

- LINAK Slovakia s.r.o.

- Danfoss Power Solutions a.s.

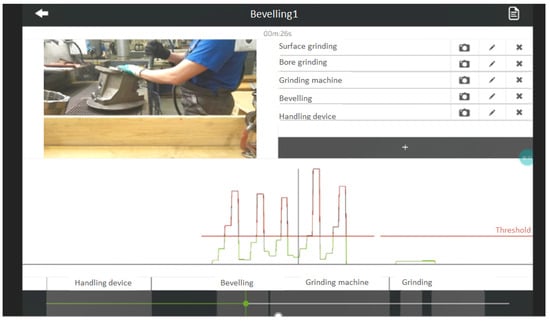

Typically, the developed exerted force is analyzed when handling different kinds of tools but also when tasks include connecting and manually handling small parts or components in the workplace, a variety of inspections, final assembly, packaging, and so on. In several cases, issues such as inadequate tool design, suboptimal working conditions, or improper handling techniques were identified as potential risk factors. Therefore, either the tool types changed or the working procedures were changed. The team was also trained to handle the specific tool used. During the evaluation, different types of hand grips were tested, since for each kind of hand grip there is a separate limit force for each working situation., e.g., after determining that a force exceeded the threshold, a different type/approach of handgrip would be suggested. The physical load could also be verified using the force measured by the smart glove due to the combination of cyclically repeated activities. This was compared to the standard OCRA method based on the “Safety of machinery—Human physical performance” in EN 1005-5 [44].

As an illustration (see Figure 21 and Figure 22), we present a measurement using a grinding machine. The worker completed two actions during the assessment: specifically, bevelling and grinding. The fundamental parameters as input data were as follows:

Figure 21.

Example of bevelling and grinding evaluation.

Figure 22.

Example of bevelling and grinding evaluation.

- Hand grip: closed hand;

- Worker: male;

- Working position: standing;

- Load type: static.

The evaluation detected the threshold violations for forces that can be seen in Figure 21 (red line).

Whirlpool Slovakia Company’s testing serves as another illustration. A female employee clamped with her right hand. As seen in Figure 22, the control device was positioned on the worker’s left arm. The fundamental attributes as input data were as follows:

- Hand grip: thumb and forefinger;

- Worker: female;

- Working position: standing;

- Load type: dynamic.

There were no violations of the recommended force limits noted as part of the evaluation. A table report is available and was generated after completing the evaluation using the CERAA Glove App. Evaluation of the measured forces based on a particular hand grip can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Evaluation of the measured forces using different hand grips.

3.3. Future Perspectives

This research has a profound impact on the future development of smart wearable micro-sensor technology (microsensors) designed to monitor occupational health. Calibration protocols established for FSR sensors using a power function model (Equation (7)) to relate raw sensor outputs to applied forces provide templates for the future development of ultra-flexible pressure sensors, while the development of a pressure cap solution that provides a uniform application of force over an entire sensor will allow for a scalable approach to miniaturized adhesive-mounted microsensor arrays. Additionally, the threshold-based analysis method used in the CERAA Glove App supports the processing of data recorded from multiple channels of force, which can be used with higher-density networks of sensors. As wearables continue to evolve towards developing skin-interfaced microsensors that have greater flexibility with significantly lower visible intrusiveness, the thresholds for grip force measurements discovered in this study (i.e., monitoring an individual during 40 repetitions over a shift) will remain significant in defining safety during the performance of manual labor. The synergy that will occur from the integration of the analytical features of the proposed design and the ultraflexible sensor arrays that will be produced will enable the real-time, unobtrusive monitoring of hand forces within traditional manufacturing settings and/or within remote working environments.

Beyond the current glove-based implementation, recent advances in ultra-flexible, skin-interfaced electronics provide a clear technological roadmap for future developments. These systems demonstrate that high-fidelity motion and physiological signals can be captured using soft, adhesive-mounted or skin-bonded devices, without the need for traditional glove form factors. In this context, the smart glove presented in this study can be viewed as an intermediate, yet practical, step: the sensor positioning strategy, calibration procedures, and data-processing algorithms developed here can be directly adapted to next-generation ultra-flexible sensor platforms for the long-term monitoring of hand function in both industrial and remote work environments.

4. Discussion: Alternative Sensing Approaches: Pressure Pixel Arrays

Measurement error due to uneven force application on the permeable surfaces of the sensor systems (shown in Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15, Figure 16 and Figure 17) may be rectified through alternative technologies. The use of multiple high-density, ultrasensitive technologies, when combined with distributed pixel arrays to create a more extensive 2D pressure mapping, has been shown to produce very-high-spatial-resolution pressure mapping [45,46]. The pixel density of several hundred “sensing elements”/cm2 enables the detailed reconstruction of force distributions.

Microconformal graphene electrodes have been shown to reach sensitivity levels of 7.68 kb (K) and detection limits of 1.0 mg, while high-resolution capacitive pressure sensor arrays can measure pressure distributions at pixel resolution. Therefore, there may no longer be a requirement for pressure distribution caps since the spatial force patterns are now accurately measured.

Nevertheless, in terms of the industrial applications that this work targets, there are many practical considerations that make it advantageous to use a single-sensor/pressure cap system. The advantages of this approach over using multiple sensors include the following: (1) a much lower overall cost and reduction in the complexity of the system, (2) less data to process, allowing for real-time monitoring capabilities, (3) increased mechanical ruggedness in very harsh factory conditions, and (4) available calibration procedures that utilize simple power function models. The pressure cap option provides similar accuracy improvements (reducing measurement error from 50% to 40% for small forces) while being significantly easier and less costly to use than high-resolution pixel arrays.

In addition to capacitive pressure pixels, recent work has highlighted transport-junction-based pressure pixels as a highly sensitive alternative for tactile sensing applications [47]. Merces et al. report pressure pixels based on transport junction mechanisms that achieve extremely high sensitivity and fast responses, and provide a quantitative comparison of different pressure pixel architectures, illustrating how these technologies can be tailored for advanced wearable and robotic interfaces. Such transport-junction-based pixels represent another promising direction for future generations of hand force monitoring systems, particularly in scenarios where very low force changes or detailed spatial pressure patterns need to be resolved.

Future versions of the smart glove may also benefit from the inclusion of smaller pixel arrays located at specific touch points in order to analyze complex patterns of grip and/or to better assess fine manipulation.

5. Conclusions

The developed system for evaluating hand-applied forces can be effectively used to identify potential risks of worker injury in any industrial sector. It is particularly suited to repetitive tasks where a specific grip force is consistently required across work cycles. The primary objective is to monitor instances where the recommended force limits might be exceeded during the execution of tasks. This check is also advised for activities that are carried out over 40 times per working shift.

Within industry, the smart glove and its application in analyses are meant to measure the force required to complete a job, focusing on industrial ergonomics, rather than an individual’s maximum strength. The glove is therefore designed to help ensure a sustainable long-term load is placed on the worker. Following the analysis of a worker’s physical load, various modifications can be introduced, including adjusting the grip type (which changes the wrist position and maximum allowed force), replacing the tool, modifying the work steps, or lowering the required force through technical means. This research introduces a device concept that can be employed in both lab and factory settings to quantify forces during workload, with expected applications in fields like the automotive and machine industries.

An analysis of the activity shown in Figure 18 revealed that the forces exerted by different fingers are not uniform. Maximum forces were recorded between approximately 12 N and 32 N for the index finger, and 7 N and 25 N for the thumb. Furthermore, the distinct force zones visible in Figure 19 could be used by ergonomics specialists during assessment.

The measurement accuracy is directly influenced by the direction and magnitude of the applied force. Errors are found to be lower when higher forces are involved, remaining below 20% for forces above approximately 12 N (see Figure 12). This precision at higher forces is highly desirable in industrial sectors like the automotive and machine industries, where developed forces are typically higher than this 12 N threshold. Conversely, the increased error below 12 N means the glove is less accurate for fine manipulation tasks.

A significant improvement in device accuracy is offered by the pressure caps attached to the sensors. The use of these caps allows for the minimization of measurement errors for small forces, reducing them from 50% to 40% (as shown by comparing Figure 12 and Figure 16).

The device’s physical design meets criteria relevant to industry. The choice of glove material and sensor placement ensures that the sensors are protected from mechanical damage. Furthermore, the wireless Bluetooth connectivity and wrist placement mean the worker is not hindered by excessive cabling.

By integrating biomechanical principles, hand anatomy knowledge, and advanced measurement capabilities, the device demonstrates potential utility in additional domains, including occupational medicine. Here, it could be applied for the early diagnosis and prevention of work-related diseases like carpal tunnel syndrome and tendinitis. Cumulative trauma disorders are known to be caused by factors including grip type, applied task forces, force distribution, repetition, temperature, and vibration. Conversely, monitoring force during rehabilitation could allow for the screening of injury recovery and physical progress. Ultimately, this work provides ergonomists with a precision tool for risk assessment and quantification in industrial environments. This approach is essential for ensuring safe, comfortable, and healthy working conditions, which are crucial prerequisites for maintaining a sustainable workforce and long-term production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and L.D.; methodology, M.G. and B.F.; software, J.Z.; validation, M.G. and M.M.; formal analysis, J.Z.; investigation, M.G.; resources, M.M.; data processing, B.F.; writing—preparation of the original draft, J.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.F.; visualization, M.M.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, L.D.; funding acquisition, L.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the KEGA Agency of Ministry of Education, Research, Development and Youth of the Slovak Republic under the contract no.: 001ŽU-4/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was a non-interventional ergonomics assessment on healthy adult volunteers and did not involve any clinical procedures or collection of identifiable personal data. Under Slovak legislation (Act No. 362/2011 Coll. on Medicinal Products and Medical Devices; Act No. 576/2004 Coll. on Healthcare), such research is not subject to mandatory prior approval by a medical ethics committee. This has been confirmed by the Institutional Review Board member responsible for the field of Industrial Engineering at the University of Žilina. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Borik, S.; Kmecova, A.; Gasova, M.; Gaso, M. Smart Glove to Measure a Grip Force of the Workers. In Proceedings of the 2019 42nd International Conference on Telecommunications and Signal Processing (TSP), Budapest, Hungary, 1–3 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 383–388. [Google Scholar]

- Greig, M.; Wells, R. Measurement of prehensile grasp capabilities by a force and moment wrench: Methodological development and assessment of manual workers. Ergonomics 2004, 47, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, S.; Spielholz, P.; Howard, N.; Silverstein, B. Force measurement in field ergonomics research and application. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2009, 39, 333–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.W.; Yu, R. Assessment of grip force and subjective hand force exertion under handedness and postural conditions. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 929–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spielholz, P. Calibrating Borg scale ratings of hand force exertion. Appl. Ergon. 2006, 37, 615–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saremi, M.; Rostamzadeh, S. Hand Dimensions and Grip Strength: A Comparison of Manual and Non-manual Workers. In Proceedings of the Congress of the International Ergonomics Association, Florence, Italy, 26–30 August 2018; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 520–529. [Google Scholar]

- Bernardes, S.M.F.; Assuncao, A.; Fujao, C.; Carnide, F. Normative reference values of the handgrip strength for the Portuguese workers. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolich, M.; Taboun, S.M. Ergonomics modelling and evaluation of automobile seat comfort. Ergonomics 2004, 47, 841–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Webster, J.G. Tactile Sensors for Robotics and Medicine; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 1988; ISBN 0471606073. [Google Scholar]

- Dario, P.; De Rossi, D. Tactile sensors and the gripping challenge: Increasing the performance of sensors over a wide range of force is a first step toward robotry that can hold and manipulate objects as humans do. IEEE Spectr. 1985, 22, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Xie, D.; Li, Z.; Zhu, H. Recent advances in wearable tactile sensors: Materials, sensing mechanisms, and device performance. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2017, 115, 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Białek, M.; Rybarczyk, D.; Milecki, A.; Nowak, P. Artificial Hand Controlled by a Glove with a Force Feedback. In Advances in Manufacturing II; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 444–455. [Google Scholar]

- Akpa, A.H.; Fujiwara, M.; Suwa, H.; Arakawa, Y.; Yasumoto, K. A Smart Glove to Track Fitness Exercises by Reading Hand Palm. J. Sens. 2019, 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoda, M.; Hoda, Y.; Hafidh, B.; El Saddik, A. Predicting muscle forces measurements from kinematics data using kinect in stroke rehabilitation. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2018, 77, 1885–1903. [Google Scholar]

- Hoda, M.; Hoda, Y.; Alamri, A.; Hafidh, B.; Saddik, A. El A novel study on natural robotic rehabilitation exergames using the unaffected arm of stroke patients. Int. J. Distrib. Sens. Netw. 2015, 11, 590584. [Google Scholar]

- Kong, Y.-K.; Freivalds, A.; Kim, S.E. Evaluation of handles in a maximum gripping task. Ergonomics 2004, 47, 1350–1364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y.-K.; Freivalds, A. Evaluation of meat-hook handle shapes. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2003, 32, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters, D. Supply Chain Risk Management: Vulnerability and Resilience in Logistics; Kogan Page Publishers: London, UK, 2011; ISBN 0749464267. [Google Scholar]

- Wakula, J. Der Montagespezifische Kraftatlas; Deutsche Gesetzliche Unfallversicherung, Institut Für Arbeitsschutz: Sankt Augustin, Germany, 2009; ISBN 3883837881. [Google Scholar]

- Koteleva, N.; Simakov, A.; Korolev, N. Smart Glove for Maintenance of Industrial Equipment. Sensors 2025, 25, 722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yan, M.; Ke, C. Joint design of VSI Tr control chart and equipment maintenance in high quality process. J. Process Control 2024, 136, 103177. [Google Scholar]

- Borghetti, M.; Lopomo, N.F.; Serpelloni, M. Novel Smart Glove for Ride Monitoring in Light Mobility. Instruments 2025, 9, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, N.W. The virtual hand: The Pulvertaft prize essay for 1996. J. Hand Surg. Am. 1997, 22, 560–567. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J.; Song, J.W.; Flavin, M.T.; Cho, S.; Li, S.; Tan, A.; Pyun, K.R.; Huang, A.G.; Wang, H.; Jeong, S.; et al. A non-contact wearable device for monitoring epidermal molecular flux. Nature 2025, 640, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.S.; Kim, J.; Fadell, N.; Pewitt, L.B.; Shaaban, Y.; Liu, C.; Jo, M.-S.; Bozovic, J.; Tzavelis, A.; Park, M.; et al. Soft, skin-interfaced wireless electrogoniometry systems for continuous monitoring of finger and wrist joints. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudson, D.V.; White, S.C. Forces on the hand in the tennis forehand drive: Application of force sensing resistors. J. Appl. Biomech. 1989, 5, 324–331. [Google Scholar]

- Orlin, M.N.; McPoil, T.G. Plantar pressure assessment. Phys. Ther. 2000, 80, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harle, R.; Taherian, S.; Pias, M.; Coulouris, G.; Hopper, A.; Cameron, J.; Lasenby, J.; Kuntze, G.; Bezodis, I.; Irwin, G. Towards real-time profiling of sprints using wearable pressure sensors. Comput. Commun. 2012, 35, 650–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, H.H.; Klitbo, T.; Jessen, C. Playware technology for physically activating play. Artif. Life Robot. 2005, 9, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiefmeier, T.; Roggen, D.; Ogris, G.; Lukowicz, P.; Tröster, G. Wearable activity tracking in car manufacturing. IEEE Pervasive Comput. 2008, 7, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergovia Ergovia Way to Healthy Productivity. Available online: http://www.ergovia.sk/produkty (accessed on 19 February 2018).

- Nexgen Ergonomics Inc. Glove Pressure Mapping System. Available online: http://www.nexgenergo.com/ergonomics/nexglove.html (accessed on 24 February 2018).

- Hoggan Scientific LLC ergoPAKTM Portable Analysis Kit. Available online: https://hogganscientific.com/product/ergopak/ (accessed on 3 December 2017).

- Tekscan Inc Ergonomic Grip Assessment. Available online: https://www.tekscan.com/applications/ergonomic-grip-assessment (accessed on 5 December 2017).

- Bruhnova, L. Testování úchopu jako základ pro nácvik úchopových forem. Rehabilitácia 2002, 2, 102–107. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, N.J.; Armstrong, T.J.; Young, J.G. Effects of handle orientation, gloves, handle friction and elbow posture on maximum horizontal pull and push forces. Ergonomics 2010, 53, 92–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, D.R.; Brammer, A.J.; Cherniack, M.G. Exposure monitoring system for day-long vibration and palm force measurements. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2008, 38, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimer, B.; McDowell, T.W.; Xu, X.S.; Welcome, D.E.; Warren, C.; Dong, R.G. Effects of gloves on the total grip strength applied to cylindrical handles. Int. J. Ind. Ergon. 2010, 40, 574–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEE, S.A. Customized Input Sensing-CIS Solutions 2017, Datasheet; IEE S.A.: Van Nuys, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Microchip Technology Inc. BM78. Bluetooth® 4.2 Dual-Mode Module 2016, Datasheet; Microchip Technology Inc.: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Microchip Technology Inc. MCP3204/3208: 2.7 V 4-Channel/8-Channel 12-Bit A/D Converters with SPI Serial Interface, Datasheet; Microchip Technology Inc.: Chandler, AZ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Atmel Atmel 8-bit Microcontroller with 4/8/16/32KBytes In-System Programmable FlashATmega328P. ATmega48A; ATmega48PA; ATmega88A; ATmega88PA; ATmega168A; ATmega168PA; ATmega328; ATmega328P 2012, Datasheet; Atmel Corporation: San Jose, CA, USA, 2012.

- Shiffman, L.M. Effects of aging on adult hand function. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1992, 46, 785–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaub, K.G. Safety of Machinery-Human Physical Performance: Manual Handling of Machinery and Component Parts of Machinery. In Handbook of Standards and Guidelines in Ergonomics and Human Factors; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; pp. 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Luo, S.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Fu, J.; Yang, W.; Wei, D. Flexible, Tunable, and Ultrasensitive Capacitive Pressure Sensor with Microconformal Graphene Electrodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 14997–15006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, Z.; Tan, D.; Sun, N.; Huang, J.; Ji, R.; Li, Q.; Bi, S.; Guo, Q.; Wang, X.; Song, J. High-Resolution and High-Sensitivity Flexible Capacitive Pressure Sensor with Micropillar Arrays. Nano Energy 2021, 87, 106190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merces, L.; de Oliveira, R.F.; Bof Bufon, C.C. Nanoscale Variable-Area Electronic Devices: Contact Mechanics and Hypersensitive Pressure Application. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 39168–39176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).